SUMMARY

RAG endonuclease initiates antibody heavy chain variable region exon assembly from V, D, and J segments within a chromosomal V(D)J recombination center (RC) by cleaving between paired gene segments and flanking recombination signal sequences (RSSs). The IGCR1 control region promotes DJH intermediate formation by isolating Ds, JHs, and RCs from upstream VHs in a chromatin loop anchored by CTCF-binding elements (CBEs). How VHs access the DJHRC for VH to DJH rearrangement was unknown. We report that CBEs immediately downstream of frequently rearranged VH-RSSs increase recombination potential of their associated VH far beyond that provided by RSSs alone. This CBE activity becomes particularly striking upon IGCR1 inactivation, which allows RAG, likely via loop extrusion, to linearly scan chromatin far upstream. VH-associated CBEs stabilize interactions of D-proximal VHs first encountered by the DJHRC during linear RAG scanning and thereby promote dominant rearrangement of these VHs by an unanticipated chromatin accessibility-enhancing CBE function.

Graphical abstract

In Brief: RAG endonuclease associated with a DJH recombination center is presented with upstream chromosomal VHs by a linear chromatin scanning process involving loop extrusion. During this process, VH-proximal CTCF looping factor binding elements mediate greatly increased interactions of their associated VHs with the DJH recombination center and, thereby, increase their accessibility for RAG cleavage and subsequent V(D)J recombination.

INTRODUCTION

Exons encoding immunoglobulin (Ig) or T cell receptor variable regions are assembled from V, D, and J gene segments during B and T lymphocyte development. V(D)J recombination is initiated by RAG1/RAG2 endonuclease (RAG), which introduces DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) between a pair of V, D, and J coding segments and flanking recombination signal sequences (RSSs) (Teng and Schatz, 2015). RSSs consist of a conserved heptamer, closely related to the canonical 5′-CACAGTG-3′ sequence, and a less-conserved nonamer separated by 12 (12RSS) or 23 (23RSS) bp spacers. Physiological RAG cleavage requires RSSs and is restricted to paired coding segments flanked, respectively, by 12RSSs and 23RSSs (Teng and Schatz, 2015). RAG binds paired RSSs as a Y-shaped heterodimer (Kim et al., 2015; Ru et al., 2015), with cleavage occurring adjacent to heptamer CACs. Cleaved coding and RSS ends reside in a RAG post-cleavage synaptic complex prior to fusion of RSS ends and coding ends, respectively, by non-homologous DSB end-joining (Alt et al., 2013).

The mouse Ig heavy chain locus (Igh) spans 2.7 Mb, with more than 100 VHs flanked by 23RSSs embedded in the 2.4 Mb distal portion; 13 Ds flanked on each side by a 12RSS located in a region starting 100 kb downstream of the D-proximal VH (VH5-2; commonly termed “VH81X”), and 4 JHs flanked by 23RSSs lying just downstream of the Ds (Alt et al., 2013) (Figures 1A and S1A). Igh V(D)J recombination is ordered, with Ds joining on their downstream side to JHs before VHs join to the upstream side of the DJH intermediate (Alt et al., 2013). D to JH joining initiates after RAG is recruited to a nascent V(D)J recombination center (“nRC”) to form an active V(D)J recombination center (RC) around the Igh intronic enhancer (iEm), JHs, and proximal DHQ52 (Teng and Schatz, 2015). Upon formation of DJH intermediates, VHs must enter a newly established DJHRC for joining. In this regard, Igh locus contraction brings VHs into closer physical proximity to the DJHRC, allowing utilization of VHs from across the VH domain (Bossen et al., 2012; Ebert et al., 2015; Proudhon et al., 2015). Following locus contraction, diffusion-related mechanisms contribute to VH incorporation into the DJHRC (Lucas et al., 2014). Yet, diffusion access alone may not explain reproducible variations in relative utilization of individual VHs (Lin et al., 2016; Bolland et al., 2016).

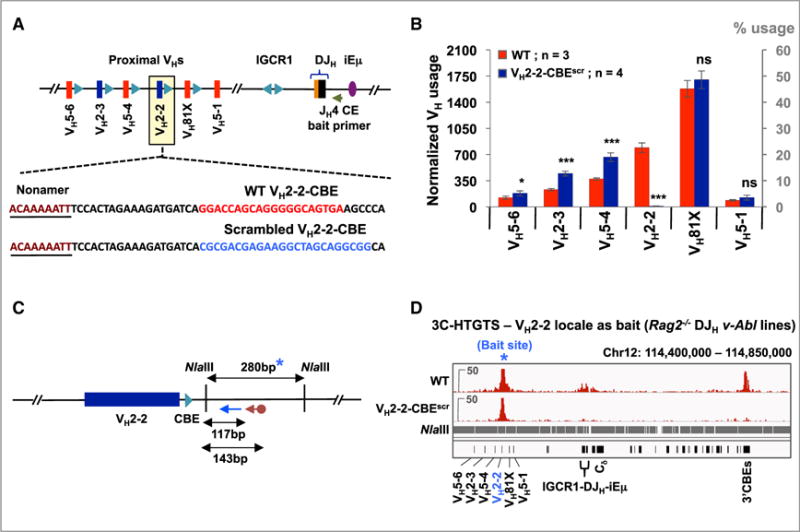

Figure 1. VH81X-CBE Greatly Enhances VH81X Utilization in Primary Pro-B Cells.

(A) Schematic of the murine Igh locus showing proximal VHs, Ds, JHs, CH exons, and regulatory elements (not to scale). Red and blue bars represent members of the IGHV5 (VH7183) and IGHV2 (VHQ52) families, respectively. Teal blue triangles represent position and orientation of CTCF-binding elements (CBEs). Green arrow denotes position of the JH4 coding end bait primer used to generate HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries.

(B) Sequence of VH81X-RSS (green) followed by WT (red) or scrambled (blue) VH81X-CBE.

(C) Relative VH utilization ± SD in BM pro-B cells from WT (top) or VH81X-CBEscr/scr (bottom) mice.

(D) Average utilization frequencies (left axis) and % usage (right axis) of indicated proximal VH segments ± SD. For analysis, each library was normalized to 10,000 VDJH junctions. p values were calculated using unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test, ns indicates p > 0.05, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01 and ***p ≤ 0.001.

V(D)J recombination is regulated to maintain specificity and diversity of antigen receptor repertoires by modulating chromatin accessibility of particular Ig or TCR loci, or regions of these loci, for V(D)J recombination (Yancopoulos et al., 1986; Alt et al., 2013). Accessibility regulation was proposed based on robust transcription of distal VHs before rearrangement (Yancopoulos and Alt, 1985) and correlated with various epigenetic modifications (Alt et al., 2013). In this regard, germline transcription and active chromatin modifications in the nRC recruit RAG1 and RAG2 to form the active RC (Teng and Schatz, 2015). Genome organization alterations also positively impact VH “accessibility” by bringing distal VHs into closer physical proximity to the DJHRC via Igh locus contraction (Bossen et al., 2012). Conversely, the intergenic control region 1 (IGCR1) in the VH to D interval plays a negative, insulating role with respect to proximal VH accessibility (Guo et al., 2011). IGCR1 function relies on two CTCF looping factor binding elements (“CBEs”) that contribute to sequestering Ds, JHs and RC within a chromatin domain that excludes proximal VHs; thereby, mediating ordered D to JH recombination and preventing proximal VH over-utilization (Guo et al., 2011; Lin et al.; 2015; Hu et al., 2015).

Eukaryotic genomes are organized into Mb or sub-Mb topologically associated domains (TADs) (Dixon et al., 2012; Nora et al., 2012) that often include contact loops anchored by pairs of convergent CBEs bound by CTCF in association with co-hesin (Phillips-Cremins et al., 2013; Rao et al., 2014). In this regard, CTCF binds CBEs in an orientation-dependent fashion. Ability to recognize widely separated convergent CBEs may involve cohesin, or other factors, that progressively extrude a growing chromatin loop that is fixed into a domain upon reaching convergent CTCF-bound loop anchors (Sanborn et al., 2015; Nichols and Corces, 2015; Fudenberg et al., 2016; Dekker and Mirny, 2016). In mammalian cells, CBEs, TADs, and/or loop domains have been implicated in regulation of various physiological processes (Dekker and Mirny, 2016; Merkenschlager and Nora, 2016; Hnisz et al., 2016), with convergent CBE-based loop organization implicated as critical for such regulation in some cases (Sanborn et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2015; de Wit et al., 2015; Ruiz-Velasco et al., 2017).

RAG can explore directionally from an initiating physiological or ectopically introduced RC for Mb distances within convergent CBE-based contact chromatin loop domains genome-wide (Hu et al., 2015). During such exploration, RAG uses RSSs in convergent orientation, including cryptic RSSs as simple as a CAC, for cleavage and joining to a canonical RSS in the RC (Hu et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2016). This long-range directional RAG activity is impeded upon encounter of cohesin-bound convergent CBE pairs and potentially by other blockages that create chromatin sub-domains within loops (Hu et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2016). The directionality and linearity of RAG activity across these domains implicated one-dimensional RAG tracking (Hu et al., 2015). Directional RAG tracking also occurs upstream of the DJH RC to IGCR1 (Hu et al., 2015). IGCR1 deletion extends this recombination tracking domain directionally upstream of the DJH RC to the proximal VHs, coupled with dramatically increased proximal VH to DJH joining, most dominantly VH81X (Hu et al., 2015). However, the nature of the tracked substrate and factors that drive RAG tracking remained speculative.

The mouse Igh harbors a high density of CBEs (Degner et al., 2011). Ten clustered CBEs (“3′CBEs”) lie at the downstream Igh boundary in convergent orientation to more than 100 CBEs embedded across the VH domain (Proudhon et al., 2015). VH CBEs are spread throughout the VH domain and, particularly for more proximal VHs, often found immediately downstream of VH RSSs (Choi et al., 2013; Bolland et al., 2016). Notably, VH CBEs and 3′CBEs are in convergent orientation with each other and with, respectively, the upstream and downstream IGCR1 CBEs (Guo et al., 2011). The striking number and organization of the CBEs across the VH portion of Igh has led to speculation of potential positive or negative VH CBE roles in Igh V(D)J recom bination (Bossen et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2011; Benner et al., 2015; Degner et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2015). Our current studies reveal the function of proximal VH CBEs and provide new insights into the RAG tracking mechanism.

RESULTS

The VH81X-CBE Greatly Augments VH81X Utilization in Primary Pro-B Cells

To examine potential functions of the CBE immediately downstream of VH81X, we generated 129SV ES cells in which the 18-bp VH81X-CBE sequence is replaced with a scrambled sequence that does not bind CTCF (Figures 1A, 1B, and S2). We introduced this mutation, referred to as “VH81X-CBEscr” into the 129SV mouse germline. VH to DJH recombination occurs in progenitor (pro) B cells in the bone marrow (BM), in which overall VH utilization frequency provides an index of relative rearrangement frequency (Lin et al., 2016; Bolland et al., 2016). To quantify utilization of each of the 100 s of distinct VHs across the 129SV mouse Igh locus in B220+CD43highIgM− BM pro-B cells, we employed highly sensitive high-throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing (HTGTS)-based V(D)J repertoire sequencing (“HTGTS-Rep-Seq”) (Hu et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2016) using a JH4-coding end primer as bait. For these analyses, we performed assays on four independent VH81X-CBEscr homozygous mutant mice (VH81X-CBEscr/scr mice) and three wild-type (WT) controls. For statistical analyses, we normalized data from each library to 10,000 total VDJH junctions and similarly normal-ized data from other experiments described below (see STAR Methods).

VH81X is the most highly utilized VH in WT 129SV mouse pro-B cells being used in ~10% of total VDJH junctions, with VH2-2, which lies ~10 kb immediately upstream, being the second most highly utilized at 6% of junctions (Figures 1C and 1D; Table S1). The three proximal VHs immediately upstream of VH2-2 also are highly utilized with frequencies of 3%, 2.2%, and 1.6%, respectively (Figures 1C and 1D; Table S1). Even though WT pro-B cells have undergone locus contraction (Medvedovic et al., 2013), only a few of the most highly used VHs further upstream approach the 2%–3% utilization range and many are utilized far less frequently (Figure 1C). As we noted previously (Yancopoulos et al., 1984), the VH5-1 pseudo-gene 5 kb downstream of VH81X is infrequently utilized (~0.4%), despite its canonical RSS (Figures 1C and 1D; Table S1). Strikingly, in VH81X-CBEscr/scr mutant mice, VH81X utilization was reduced ~50-fold to 0.2% of junctions with a concomitant increase in uti-lization of VH2-2 and next three upstream VHs (Figures 1C and 1D; Table S1). However, there were no significant effects on uti-lization of further upstream VHs or the downstream VH5-1 (Figures 1C and 1D; Table S1). Thus, the VH81X-CBE is required to promote VH81X rearrangement in mouse pro-B cells; and, in its absence, utilization of the upstream VH2-2 doubles to make it the most utilized VH.

VH81X-CBE Greatly Augments VH81X to DJH Rearrangement in a v-Abl Pro-B Cell Line

To establish a cell culture model to facilitate further analyses of VH81X-CBE function in V(D)J recombination, we first tested whether this element is required for VH81X rearrangement in v-Abl transformed, Eμ-Bcl2-expressing pro-B cells viably arrested in the G1 cell-cycle phase by treatment with STI-571 to induce RAG expression and V(D)J recombination (Bredemeyer et al., 2006). For this purpose, we derived a v-Abl pro-B line that harbors an inert non-productive rearrangement of a distal VHJ558 that deletes all proximal VHs and Ds on one allele and a DHFL16.1 to JH4 rearrangement that actively undergoes VH to DJH recombination on the other allele (Figure 2A). Like an ATM-deficient DJH-rearranged v-Abl pro-B line (Hu et al., 2015), the DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl pro-B line predominantly rearranges the most proximal VHs with only low level distal VH rearrangement due to lack of lgh locus contraction in v-Abl lines (Figure S3A). We also employed a Cas9/gRNA approach to generate a derivative of the DHFL16.1JH4 line in which we deleted the VH81X-CBE (referred to as “VH81X-CBEdel” mutation) on the DJH allele (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. VH81X-CBE Enhances VH81X Utilization in DJH Rearranged v-Abl Pro-B Lines.

(A) Schematic representation of the two murine Igh alleles in DJH rearranged v-Abl pro-B cell line (not to scale). One allele (top) harbors a non-productive VDJH rearrangement involving a distal VHJ558 (VH1-2P) that deletes the proximal VH domain and is inert for V(D)J recombination. The other allele (bottom) harbors a DHFL16.1 to JH4 rearrangement (DJH allele) that actively undergoes VH to DJH recombination upon RAG induction via G1 arrest. This DHFL16.1JH4 line served as the parent WT line and was used for all subsequent genetic manipulations.

(B) Top line shows the sequence of WT VH81X-CBE (red) while the bottom line shows VH81X-CBE deletion (blue dashed line).

(C) Average utilization frequencies (left axis) or % usage (right axis) ± SD of indicated proximal VHs in WT and VH81X-CBEdel v-Abl pro-B lines; libraries were normalized to 3,500 VDJH junctions. As the WT line used for this experiment was the parent of all subsequent VH-CBE mutant lines, we generated WT repeats at several points over the course of these experiments and used the average data, which were highly reproducible, for this and subsequent panels showing comparisons of mutants with WT controls (see STAR Methods for details).

(D) Schematic of the 101-kb intergenic deletion extending from 302 bp downstream of VH81X-CBE to 400 bp upstream of the DHFL16.1JH4 RC in the WT DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl line and its VH81X-CBEdel derivative.

(E) Average utilization frequencies (left axis) or % usage (right axis) ± SD of indicated proximal VHs in Intergenicdel and Intergenicdel VH81X-CBEdel v-Abl lines; libraries were normalized to 100,000 VDJH junctions.

(F) Sequence of WT (red) and VH81X-CBE inversion mutation (blue).

(G) Average utilization frequencies (left axis) or % usage (right axis) ± SD of the indicated proximal VHs in DHFL16.1JH4 WT and VH81X-CBEinv v-Abl lines; libraries were normalized to 3,500 VDJH junctions. Statistical analyses were performed as in Figure 1.

See also Figure S3 and Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4.

We analyzed three separate HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries from both parent and VH81X-CBEdel DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl pro-B lines. These analyses revealed that VH81X is utilized in ~45% of VDJH rearrangements in the parent line, but in only ~0.5% of VDJH rearrangements in the VH81X-CBEdel line, representing a 100-fold decrease (Figures 2C and S3A; Table S1). Likewise, in VH81X-CBEdel DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl cells, we observed corresponding increases in utilization of the four VHs upstream of VH81X with relative utilization patterns similar to those observed in VH81X-CBEscr/scr BM pro-B cells and no change in utilization of the downstream VH5-1 (Figure 2C; Table S1). Based on these findings, we conclude that the various effects of VH81X-CBEdel mutation on utilization of VH81X and upstream neighboring proximal VHs are essentially identical in developing mouse pro-B cells and the DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl pro-B cell line. Therefore, we employed this v-Abl pro-B line to further extend these studies and address mechanism.

VH81X-CBE Mutation Does Not Impair VH RSS Functionality for V(D)J Recombination

Sequencing VH81X-CBE scrambled and deletion mutations in genomic DNA confirmed that both left the VH81X-RSS intact. Yet, the effect of VH81X-CBE mutations is nearly as profound and specific as expected for mutation of an RSS. To confirm that basic VH81X-RSS functions were intact subsequent to CBE deletion, we used a Cas9/gRNA approach to delete the ~101 kb sequence downstream of the VH81X-RSS in both DH FL16.1JH4 and VH81X-CBEdel DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl cells, thereby positioning VH81X and its canonical RSS ~700 bp upstream of the DJHRC in both lines (Figure 2D). This large intergenic deletion mutation (referred to as “Intergenicdel”), which removes IGCR1 and VH5-1, led to a 30-fold increase in overall VH to DJH joining levels in both the DHFL16.1JH4 and VH81X-CBEdel DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl lines (Table S2). Comparative HTGTS-Rep-seq analyses of multiple libraries from Intergenicdel and Intergenicdel VH81X-CBEdel DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl lines demonstrated that 60% of the overall increase in VDJH junctions in both lines involved VH81X and that the remainder was contributed by proximal VHs just upstream (Figures 2E and S3B). Indeed, VH to DJH rearrangement levels and patterns in the parental and VH81X-CBEdel v-Abl lines harboring the large intergenic deletion were essentially indistinguishable (Figures 2E and S3B; Table S1). Thus, elimination of the VH81X-CBE does not alter ability of VH81X to undergo robust V(D)J recombination when VH81X is positioned near the DJHRC, indicating that the VH81X-CBE V(D)J recombination function is manifested at a different level than RSS-dependent RAG cleavage.

The VH81X-CBE Mediates Robust VH81X Rearrangement when Inverted

Several studies indicated that CBE orientation is critical for its function as a loop domain anchor (Rao et al., 2014; Sanborn et al., 2015), as well as for mediating enhancer-promoter interactions (Guo et al., 2015; de Wit et al., 2015) and regulating alternative splicing (Ruiz-Velasco et al., 2017). Convergent VH-CBE orientation with respect to IGCR1-CBE1 and the 3′CBEs suggested that such organization may be important for V(D)J recombination regulation (Guo et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2015; Benner et al., 2015; Aiden and Casellas, 2015; Proudhon et al., 2015). To test this notion, we used a Cas9/gRNA approach to invert a 40-bp sequence encompassing VH81X-CBE in the DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl line to generate “VH81X-CBEinv” lines (Figure 2F). Comparative HTGTS-Rep-seq analyses of multiple libraries from parent and VH81X-CBEinv lines demonstrated that inversion of the VH81X-CBE resulted in only an ~2-fold decrease in VH81X utilization (Figures 2G and S3C; Table S1), as compared to the 100-fold reduction observed upon VH81X-CBE deletion (Figure 2C; Table S1). Thus, the VH81X-CBE in inverted orientation supports reduced, but still robust, VH81X utilization.

VH81X-CBE Promotes Interaction with the DJHnRC

To examine VH81X-CBE interactions with other Igh regions, we developed an HTGTS-based methodology that provides high-resolution and reproducible interaction profiles of a bait locale of interest with unknown (prey) interacting sequences across Igh (Figure 3A). For this method, termed 3C-HTGTS, we prepare a 3C library (Dekker et al., 2002) with a 4-bp cutting restriction endonuclease and, after the sonication step, employ linear amplification-mediated-HTGTS (Frock et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2016) to complete and analyze the libraries (see STAR Methods). For our purposes, 3C-HTGTS substitutes well for prior 4C-related approaches (Denker and de Laat, 2016). In this regard, use of linear amplification to enrich for ligated products allows 3C-HTGTS to generate highly sensitive and specific interaction profiles for widely separated bait and prey sequences (Figure 3C). As all pro-B line Igh chromatin interaction experiments must be done in the context of RAG-deficiency to avoid confounding effects of ongoing V(D)J recombination, we used a Cas9/gRNA approach to derive RAG2-deficient derivatives of the various v-Abl lines.

Figure 3. VH81X-CBE Promotes Interactions of Its Flanking VH with the DJHRC.

(A) Schematic representation of the 3C-HTGTS method for studying chromosomal looping interactions of a bait region of interest with the rest of Igh locus (see text and STAR Methods for details).

(B) Schematic of the NlaIII restriction fragment (indicated by a blue asterisk) and the relative positions of the biotinylated (cayenne arrow) and nested (blue arrow) PCR primers used for 3C-HTGTS from VH81X bait in (C).

(C) Top panel: schematic representation of chromosome interactions of VH81X-CBE containing NlaIII fragment with other Igh locales. Bottom two panels: 3C-HTGTS profiles of Rag2−/− derivatives of control, VH81X-CBEdel, and VH81X-CBEinv DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl lines using VH81X-CBE locale as bait (blue asterisk). Owing to a DHFL16.1 to JH4 rearrangement in the lines, the region spanning IGCR1, DJH substrate and iEm appears as a broad interaction peak. As v-Abl lines lack locus contraction, we detected few substantial interactions with the upstream Igh locus beyond the most proximal VHs (see legend of Figure S3). Two independent datasets are shown from libraries normalized to 105,638 total junctions.

See also Table S4.

To identify interaction partners of VH81X, we performed 3C-HTGTS on RAG2-deficient derivatives of control, VH81X-CBEdel, and VH81X-CBEinv DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl lines using VH81X as bait (Figure 3B). In control RAG2-deficient DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl cells, VH81X reproducibly interacts specifically with a region 100 kb downstream that spans IGCR1 and the closely linked (3 kb downstream) DJHnRC locale, as well as with a region 300 kb downstream containing the 3′ Igh CBEs (Figure 3C). Both of these interactions are dependent on the VH81X-CBE, as they are essentially absent in VH81X-CBEdel RAG2-deficient DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl cells (Figure 3C). However, 3C-HTGTS analyses of the VH81X-CBEinv RAG2-deficient DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl cells revealed significant VH81X interactions with IGCR1/DJHnRC and 3′CBEs, albeit at moderately reduced levels compared to those of RAG2-deficient DHFL16.1JH4 control v-Abl cells (Figure 3C). Thus, levels of VH81X interactions with IGCR1/DJHnRC locale and 3′CBEs in VH81X-CBE inversion and deletion mutants reflect VH81X utilization in these mutants relative to the parental DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl lines, implying a potential mechanistic relationship between these interactions and VH81X utilization.

V(D)J Recombination of VH2-2 Is Critically Dependent on Its Flanking CBE

To test the function of an additional VH-associated CBE, we generated “VH2-2-CBEscr” DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl lines in which the CBE just downstream of VH2-2 was replaced with a scrambled sequence that does not bind CTCF (Figure 4A). Comparative analyses of multiple HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries from the parental versus VH2-2-CBEscr mutant DHFL16.1JH4 lines demonstrated that the VH2-2-CBE-scrambled mutation reduced VH2-2 utilization nearly 100-fold in the VH2-2-CBEscr line (Figures 4B and S4A; Table S1). In addition, the VH2-2-CBEscr mutation led to increased utilization of the three VHs immediately upstream of VH2-2, but had no effect on utilization of the downstream VH81X and the VH5-1 pseudo-VH (Figure 4B). 3C-HTGTS assays performed on RAG2-deficient parental and VH2-2-CBEscr DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl lines showed that VH2-2, like VH81X, signifi-cantly interacts with the IGCR1/DJHnRC locale and the 3′CBEs in a VH2-2-CBE-dependent manner (Figures 4C, 4D, and S4B). Thus, the various effects of VH2-2-CBEscr mutation on VH2-2 utilization, utilization of neighboring VHs, and long-range interactions with downstream Igh IGCR1/DJHnRC locale corresponds well with those associated with deletion of the VH81X-CBE.

Figure 4. V(D)J Recombination of VH2-2 Is Critically Dependent on Its Flanking CBE.

(A) Sequence of WT VH2-2-CBE (red) and its scrambled mutation (blue).

(B) Average utilization frequencies (left axis) or % usage (right axis) ± SD of indicated proximal VHs in WT and VH2-2-CBEscr v-Abl lines. Each library was normalized to 3,500 VDJH junctions. Statistical analyses were performed as in Figure 1. See also Figure S4A and Table S1.

(C) Illustration of NlaIII restriction fragment (blue asterisk) and relative positions of biotinylated (cayenne arrow) and nested (blue arrow) primers used for 3C-HTGTS analyses in (D). Due to repetitive sequences in the restriction fragment that harbors VH2-2-CBE, the downstream flanking restriction fragment was used as bait.

(D) Representative 3C-HTGTS interaction profiles of VH2-2 locale (blue asterisk) in Rag2−/− control and VH2-2-CBEscr v-Abl lines, plotted from libraries normalized to 84,578 total junctions. See Figure S4B for an independent repeat.

See also Tables S3 and S4.

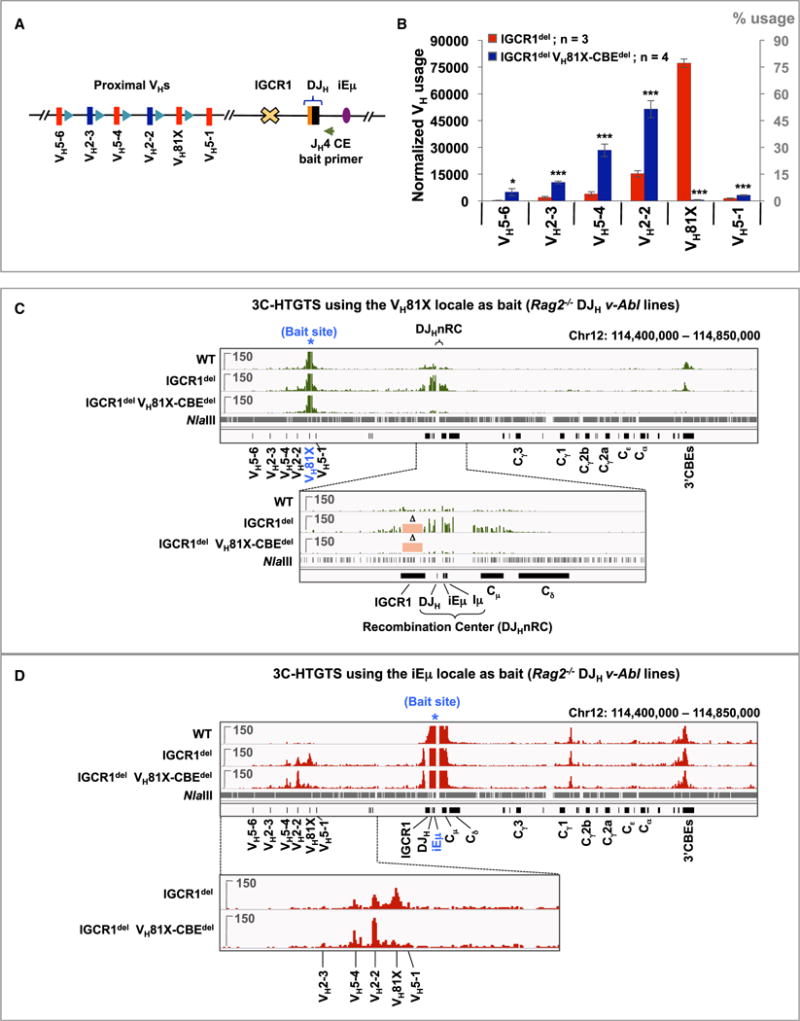

CBE-Dependent VH81X Dominance without IGCR1 Implicates RAG Chromatin Tracking

IGCR1 deletion results in tremendous over-utilization of proximal VHs, most dramatically VH81X, in association with RAG linear exploration of sequences upstream of IGCR1 via some form of tracking (Hu et al., 2015). To test whether the VH81X-CBE contributes to the immense over-utilization of VH81X in the context of IGCR1 deletion and RAG tracking, we generated IGCR1-deleted (“IGCR1del”) DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl cells with or without the VH81X-CBEdel mutation (Figure 5A). As expected, IGCR1 deletion led to a 30-fold increase in overall VH to DJH joining levels as compared to those of the DHFL16.1JH4 parent line, involving most predominantly VH81X and to a lesser extent proximal upstream VHs and the downstream VH5-1 (Figure S5A; Tables S1 and S2). Comparative analyses of multiple HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries from IGCR1del versus IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel DHFL16.1JH4 lines revealed more than a 100-fold decrease in VH81X utilization in the IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel line versus the IGCR1del line (Figures 5B and S5B; Table S1). Once again, this dramatic decrease in VH81X utilization was accompanied by increased utilization of the four VHs immediately upstream of VH81X (Figure 5B; Table S1).

Figure 5. VH81X-CBE Is Required for Dominant VH81X Usage in the Absence of IGCR1.

(A) Schematic of 4.1 kb IGCR1 deletion.

(B) Average utilization frequencies (left axis) or % usage (right axis) ± SD of proximal VHs in IGCR1del and IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel v-Abl lines. Each library was normalized to 100,000 VDJH junctions. Statistical analyses were performed as in Figure 1. See also Figures S5A and S5B and Tables S1 and S2.

(C) Representative 3C-HTGTS interaction profiles of VH81X bait (blue asterisk) in Rag2−/− control, IGCR1del, and IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl lines performed using the strategy shown in Figure 3B, plotted from libraries normalized to 106,700 total junctions. Bottom panel shows a zoom-in of the region extending from upstream of IGCR1 to downstream of Cd exons. Pink rectangles marked with “D” indicate the IGCR1 region deleted in the IGCR1del and IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel lines. See Figure S5C for an additional repeat.

(D) Representative 3C-HTGTS interaction profiles of iEm bait (blue asterisk) in Rag2−/− v-Abl DJH lines of the indicated genotypes following NlaIII digest using the strategy shown in Figure S5D. Each library was normalized to 273,547 total junctions. Bottom: zoom-in of the proximal VH region. See Figure S5D for an independent repeat and Figure S6 for related repeats.

See also Figure S7 and Tables S3 and S4.

To identify VH81X-CBE interaction partners in the context of IGCR1-deficiency, we performed 3C-HTGTS using VH81X bait on RAG2-deficient DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl cells that also harbored either IGCR1del or IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel mutations (Figure 5C). As described above (Figure 3C), VH81X has signifi-cant VH81X-CBE-dependent interactions with the lGCR1/DJH nRC locale and the 3′CBEs in RAG2-deficient DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl cells. However, in RAG2-deficient IGCR1del lines, VH81X interaction with the DJHnRC locale, which we can now pinpoint in the absence of IGCR1, occurs at far higher levels than its interaction with the lGCR1/DJHnRC locale in RAG2-deficient DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl parent line, even though interactions with the 3′CBEs remain the same or are slightly decreased (Figures 5C and S5C; top and bottom zoomed-in panels). Strikingly, in RAG2-deficient IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel lines, VH81X interactions with the DJHnRC and 3′CBEs were essentially eliminated (Figures 5C and S5C; top and bottom zoomed-in panels).

We also used iEm within the DJHnRC as bait to examine interactions with other Igh sequences in this same set of RAG2-deficient control, IGCR1del, and IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl lines. In all three genotypes, iEm interacted with the 3′CBEs and with a region between Cg1 and Cg2b (Medvedovic et al., 2013). In the RAG2-deficient DHFL16.1JH4 control line, iEm has barely detectable interaction with proximal VHs (Figures 5D and S5D; top panel). However, in RAG2-deficient IGCR1del lines, iEm robustly interacts with VH81X and, at decreasing levels, with the upstream VH2-2 and VH5-4. In the RAG2-deficient IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel lines, interactions between iEm and VH81X decreased dramatically while interactions with the immediately upstream VH2-2 increased (Figures 5D and S5D; top and bottom zoomed-in panels). We also employed the iEm as well as another DHQ52-JH1 locale bait, as a distinct nRC bait for 3C-HTGTS assays in RAG2-deficient control and IGCR1del/del v-Abl lines with an unrearranged Igh locus and found essentially identical interaction profiles (Figure S6). Together, these 3C-HTGTS studies indicate that the impact of IGCR1 deletion on dramatically increased CBE-dependent utilization of proximal VHs in RAG2-sufficient WT and mutant lines directly correlates with their interaction with the DJHnRC in their RAG2-deficient counterparts.

Restoration of a Vestigial CBE Converts VH5-1 into the Most Highly Rearranging VH

Mutation of the VH81X or VH2-2 CBEs remarkably reduce ability of these VHs to be utilized for V(D)J recombination, despite retention of their normal RSSs. In this regard, the most D-proximal VH5-1 has a canonical RSS (Figure 6A), but is infrequently rearranged in WT pro-B cells or v-Abl pro-B lines (Hu et al., 2015) (Figures 1C and 2C; Table S1). By employing a JASPAR sequence-based prediction, we found that VH5-1 also is flanked downstream of its RSS by a CBE-related sequence (Figure 6A), the site of which is CpG methylated and does not bind CTCF in pro-B cells (Benner et al., 2015). To test if lack of a functional CBE causes infrequent VH5-1 utilization, we generated DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl lines (referred to as “VH5-1-CBEins”) in which 4 bps within this putative vestigial CBE were mutated to eliminate the CpG island and generate a consensus CTCF-binding element (Figure 6A). Comparative analyses of multiple HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries from the parental and VH5-1-CBEins DHFL16.1JH4 lines demonstrated that generation of VH5-1-CBE resulted in over a 20-fold increase in VH5-1 utilization, converting it into the most highly utilized VH (Figures 6B and S4C; Table S1). Notably, this gain of function VH5-1-CBEins mutation also decreased utilization of the immediately upstream VH81X and the next four upstream VHs, with their reduced utilization levels corresponding linearly with increasing distance upstream (Figure 6B). Strikingly, 3C-HTGTS studies on RAG2-deficient VH5-1-CBEins lines demonstrated that restoration of the VH5-1-CBE also promoted significant gain of function interactions of VH5-1 with the IGCR1/DJHnRC locale and 3′CBEs (Figures 6C, 6D, and S4D), further supporting direct links between VH recombination potential and these interactions. Finally, we deleted IGCR1 in the VH5-1-CBEins line, which led to an 60-fold increase in VH5-1 utilization with dramatically decreased utilization of VH81X and other upstream proximal VHs (Figures S7A and S7B). Likewise, in 3C-HTGTS experiments VH5-1 gained dramatically increased interactions with the DJHnRC as viewed from an iEm bait (Figure S7C).

Figure 6. Restoration of a CBE Converts VH5-1 into the Most Highly Rearranging VH.

(A) Schematic showing the sequence of VH5-1-RSS and its downstream non-functional, “vestigial” CBE. The yellow shaded box highlights the CpG island that is methylated in normal pro-B cells. Bottom sequence shows the four nucleotides mutated (highlighted in blue) to eliminate the CpG island and restore consensus CBE sequence. Two additional nucleotides were mutated just downstream of the CBE to generate a BglII site for screening.

(B) Average utilization frequencies (left axis) or % usage (right axis) ± SD of the indicated proximal VHs in WT and VH5-1-CBEins v-Abl lines. Each library was normalized to 3,500 VDJH junctions. Statistical analyses were performed as in Figure 1. See also Figure S4C and Table S1.

(C) Illustration of the MseI restriction fragment (blue asterisk) and the relative positions of biotinylated (cayenne arrow) and nested (blue arrow) primers used for 3C-HTGTS analyses in (D).

(D) Representative 3C-HTGTS interaction profiles of the VH5-1 locale (blue asterisk) in Rag2−/− control and VH5-1-CBEins v-Abl lines, plotted from libraries normalized to 37,856 total junctions. See Figure S4D for an independent repeat.

See also Figure S7 and Tables S3 and S4.

DISCUSSION

Proximal VH-CBEs Enhance V(D)J Recombination Potential of Associated VHs

We report a major role for VH-associated CBEs in V(D)J recombination. Thus, V(D)J recombination potential of VH81X is dramatically enhanced in both primary pro-B cells in mice and in v-Abl pro-B lines by its associated CBE. Likewise, V(D)J recombination potential of the upstream VH2-2 is similarly enhanced by its associated CBE. Decades ago, we hypothe-sized one dimensional “recombinase scanning” as a possible mechanism for preferential proximal VH utilization, but noted that there must be an additional determinant based on low level VH5-1 pseudo-VH utilization despite its most proximal location downstream of VH81X and consensus RSS (Yancopoulos et al., 1984). We now identify this additional determinant as a CBE by converting the “vestigial” CBE downstream of VH5-1 into a functional CBE and, thereby, rendering it the most frequently rearranged VH. However, the VH81X-CBE was not required for robust VH81X rearrangement when it was placed linearly adjacent to the DJHRC, indicating VH-CBE function is distinct from that of RSSs. To further assess the mechanism by which proximal VH-CBEs enhance V(D)J recombination potential, we developed the highly sensitive 3C-HTGTS chromatin interaction method. Effects of various tested loss and gain of function CBE mutations on V(D)J recombination potential of the 3 proximal VHs were mirrored by effects on their interactions with the DJHnRC. This relationship was most striking in the context of IGCR1 deletion, which leads to both dramatically increased VH81X utilization and dramatically increased VH81X interaction with the DJHnRC, with both increases being dependent on the VH81X-CBE. Thus, proximal VH-CBEs increase V(D)J recombination potential by increasing the frequency with which their associated VHs interact with the DJHRC.

VH-CBEs Mediate RSS Accessibility during RAG Chromatin Scanning

RAG tracking in the absence of IGCR1 proceeds upstream to the most proximal VHs, resulting in their increased rearrangement to DJH intermediates (Hu et al., 2015). This dominant increase in VH81X rearrangement during tracking in the absence of IGCR1 is VH81X-CBE-dependent and associated with CBE-mediated DJH RC interactions. The imprint of linear tracking on proximal VH utilization in the absence of IGCR1 goes beyond VH81X. Thus, in v-Abl pro-B lines, where tracking effects are more pronounced in the absence of locus contraction, the three VHs just upstream of VH81X also show markedly increased utilization with relative utilization decreasing with upstream distance. Likewise, while VH81X utilization plummets in VH81X-CBEdel v-Abl cells lacking IGCR1, utilization of the upstream VH2-2 becomes dominant and that of the three upstream VHs again increases with levels inversely related to upstream distance. Also consistent with linear tracking, utilization of the most downstream CBE-less VH5-1 with a restored CBE increases substantially in the absence of IGCR1 becoming dominant even over VH81X. Relative VH utilization patterns during RAG upstream tracking in the absence of IGCR1 correlate well with proximal VH interactions with the DJHnRC. Together, these findings indicate that RAG scans chromatin, rather than DNA per se, allowing this process to be better described as linear RAG chromatin scanning; and they further indicate that proximal VH-CBEs promote over-utilization of associated VHs via a chromatin accessibility-enhancing function. The mechanism of this accessibility function likely involves CBE-mediated prolonged interaction of the VH with the DJHRC. We find that long-range interactions critical to RAG chromatin scanning do not require a functional RAG complex. Thus, RAG bound to the DJHRC may harness a more general cellular mechanism operating within the Igh locus, such as cohesin-mediated chromatin loop extrusion, to scan distal sequences.

RAG Chromatin Scanning Shares Features with Chromatin Loop Extrusion

Inserting RSS pairs to generate ectopic “RCs” in various random genomic sites revealed orientation-specific linear RAG chromatin scanning within chromosome loop domains bounded by convergent CBE anchors, suggesting cohesin involvement (Hu et al., 2015). Features of RAG scanning overlap with those of cohesin-mediated loop extrusion (Dixon et al., 2016; Dekker and Mirny, 2016). Cohesin rings extrude chromatin loops that become progressively larger, bringing distal chromosomal regions into physical proximity in a linear fashion and having the potential to increase contact frequencies between loop anchors and sequences across extrusion domains (Fudenberg et al., 2016; Rao et al., 2017; Sanborn et al., 2015; Schwarzer et al., 2017). In this regard, CBEs bound by CTCF act as strong loop anchors and impede extrusion (Nichols and Corces, 2015; Fudenberg et al., 2016; Nora et al., 2017). Overlaps between loop extrusion and RAG scanning suggest that scanning may be driven by chromatin extrusion past a RAG-containing “RC anchor” (Figure 7). While convergent CBE anchors substantially block extrusion, other chromatin structures, such as enhancers, can impede extrusion (Dekker and Mirny, 2016). Thus, based on interactions in pro-B cells (Guo et al., 2011; Medvedovic et al., 2013; this study), IGCR1 and the JHRC may act as upstream and downstream barriers to loop extrusion-mediated RAG scanning during D to JH recombination. Deletion of IGCR1 would eliminate the upstream barrier and extend extrusion into proximal VHs, allowing VH CTCF/cohesin-bound CBE interactions with the downstream RC extrusion anchor that increase accessibility of associated VHs. While VH-CBEs increase RC interaction frequencies, they do not create absolute boundaries, as RAG scanning can extend past them at decreased levels to immediately upstream VHs. In contrast to certain CBE-mediated looping and regulatory processes (Sanborn et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2015; de Wit et al., 2015), VH81X-CBE function during RAG scanning is moderately enhanced by, but not strictly dependent on, convergent orientation, likely due to stronger interactions in convergent orientation. Finally, proximal VH-CBEs, DJHRC and 3′CBEs all interact suggesting 3′CBEs may contribute to VH-DJHRC interactions. If so, deleting all 3′CBEs may influence Igh V(D)J recombination more than deleting a subset (Volpi et al., 2012).

Figure 7. Model for RAG Chromatin Scanning via Loop Extrusion.

Figure shows a working model for potential roles of VH-associated CBEs during RAG scanning over chromatin. Numerous variations of the model are conceivable.

(A) From its location in the initiating RC, RAG linearly scans cohesin-mediated extrusion loops proceeding through Ds, to allow their utilization; but is largely impeded further upstream by the IGCR1 anchor. After formation of a DJHRC, residual lower level scanning of upstream sequences beyond the IGCR1 impediment allows the most proximal VH-CBEs to mediate direct association with the DJHRC enhancing utilization of their associated VH. VHs further upstream likely access the DJHRC by diffusion with proximal CBEs also enhancing DJHRC interactions and flanking VH utilization.

(B) In the absence of IGCR1, loop extrusion progresses upstream allowing RAG to scan the most proximal VHs where associated CBEs promote DJHRC interaction, accessibility, and dominant over-utilization in V(D)J joins. Utilization is most robust for proximal VH81X, which provides the first VH-CBE encountered during linear scanning. VH5-1 is bypassed due to lack of a CBE. Scanning can sometimes bypass VH81X-CBE and continues to the first few upstream VHs, with their CBEs similarly promoting utilization.

(C) If both IGCR1 and the VH81X-CBE are mutated, loop-extrusion continues unabated to the VH2-2-CBE and to progressively lesser extents to immediately upstream VH-CBEs.

(D–F) CBEs not directly flanking distal VHs theoretically also may augment VH utilization.

(D) A distal VH locus CBE associates strongly with chromatin or associated factors (e.g., CTCF/cohesin) at the DJHRC.

(E) Cohesin rings load near this DJHRC-associated distal VH locus CBE and initiate loop extrusion.

(F) Loop-extrusion allows RAG to scan downstream (or upstream, not illustrated) VHs lacking directly associated CBEs from the DJHRC where the active/transcribed chromatin in which they lie facilitates access for V(D)J recombination (see text for more details and relevant references.

See also Figure S1.

Contribution of RAG Scanning to Proximal VH Usage in the Presence of IGCR1

After Igh locus contraction brings distal VHs into closer proximity of the DJHRC, they become directly associated with the RC via subsequent diffusion-related mechanisms (Lucas et al., 2014). Notably, however, utilization of the very most proximal VHs does not require locus contraction (Fuxa et al., 2004). In this regard, primary locus-contracted pro-B cells utilize VH81X and VH2-2 more frequently than more distal VHs. Likewise, in VH81X-CBE mutant primary pro-B cells utilization of the immediately upstream VH2-2 increases dramatically with utilization of the next two upstream VHs increasing to levels higher than those of more distal VHs. In v-Abl pro-B cells, which lack Igh contraction but have intact IGCR1, over-utilization of VH81X and the four immediately upstream VHs have a distance-dependent utilization pattern reminiscent of that when IGCR1 is inactivated. Likewise, deletion of the VH2-2-CBE increases relative utilization of upstream VHs, again with the same distance-related pattern, but has no effect on downstream VH81X utilization. Finally, ectopic introduction of an immediately downstream CBE renders proximal VH5-1 the most highly utilized VH, while, correspondingly, greatly dampening utilization of upstream VHs. Together, these findings indicate that the relatively high recombination potential of very most proximal functional VHs, even in normal, locus contracted pro-B cells, results from low level RAG chromatin scanning from the DJHRC into the proximal VH domain in the presence of IGCR1 CBEs. Beyond these proximal VHs, RAG linear scanning upstream of the DJHRC appears to have little, if any, impact, even in the absence of IGCR1; likely because dominant utilization of proximal VHs first encountered obviates most RAG scanning upstream.

Potential Roles of CBEs and RAG Scanning in Distal VH Recombination

Nearly all functional mouse VHs have CBEs directly adjacent or within several kb (Figure S1). In this regard, more distal VH-CBEs likely have V(D)J recombination functions related to those we have elucidated for CBEs of the very most proximal VHs. The VH portion of Igh comprises proximal, middle, J558 and distal J558/3609 VH regions with different chromatin and transcriptional properties (Choi et al., 2013; Bolland et al., 2016) (Figure S1A). The proximal and middle regions largely have repressive as opposed to active chromatin marks; and VHs within them, including VH81X, show little or no germline transcription. Correspondingly, the majority of proximal/middle VHs, in addition to the few accessible to RAG linear scanning, have CBEs adjacent to their RSSs that may stabilize diffusion-mediated interactions with the DJHRC to promote accessibility (Figures S1B, S1C, and 7A). Notably, the J558 and, particularly, the distal J558/3609 regions have accessible chromatin marks and regions of transcription. In contrast to proximal VHs, few distal VHs are directly associated with a CBE, but most have CBEs within 10 kb and often much closer (Figures S1D and S1E). Such CBEs in distal domains still may enhance diffusion-mediated interactions with the DJHRC directly or in association with other interacting sequences such as IGCR1 or the 3′CBEs. Interactions with CBEs not directly associated with VHs also could provide anchors for loop extrusion of the locally accessible distal VHs past the RC (Figures 7D–7F). Thereby, distal VHs may be utilized without an immediately adjacent CBE. Other antigen receptor loci in mouse and humans also have large numbers of CBEs (Proudhon et al., 2015; Bolland et al., 2016), including some in Igκ and Tcrα/δ that play IGCR1-like functions (Xiang et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2015). RAG scanning in TCRδ also is restricted to CBE-anchored loop domains (Zhao et al., 2016). Similar to the proximal and distal Igh, differing V domain CBE organizations among antigen receptor loci also might function in the context of RAG scanning/loop extrusion. Why different antigen receptor loci domains evolved different CBE organizational solutions to regulate VH usage remains an interesting question.

STAR★ METHODS

Detailed methods are provided in the online version of this paper and include the following:

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-CTCF | EMD Millipore | Cat#07-729 |

| APC anti-B220 | eBioscience | Cat#18-0452-83 |

| FITC anti-IgM | eBioscience | Cat#11-5790-81 |

| PE anti-CD43 | BD PharMingen | Cat#553271 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| DH5a Competent Cells | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#18265017 |

| pMSCV-v-Abl retrovirus | Bredemeyer et al., 2006 | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| G418 Sulfate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#11811031 |

| NotI | NEB | Cat#R0189 |

| XbaI | NEB | Cat#R0145 |

| EcoRV | NEB | Cat#R0195 |

| NlaIII | NEB | Cat#R0125 |

| MseI | NEB | Cat#R0525 |

| Red Blood Cell Lysing Buffer Hybri-Max | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#R7757 |

| STI-571 | Novartis | N/A |

| Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin C1 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#65001 |

| Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | NEB | Cat#M0530L |

| Protease inhibitors | Roche | Cat#11836153001 |

| T4 DNA ligase | Promega | Cat#M1804 |

| Proteinase K | Roche | Cat#03115852001 |

| RNase A | Invitrogen | Cat#8003089 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#20148 |

| MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600 cycle) | Illumina | Cat#MS-102-3003 |

| MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 (500 cycle) | Illumina | Cat#MS-102-2003 |

| PhiX Control v3 Kit | Illumina | Cat#FC-110-3001 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw data of pro-B HTGTS-Rep-Seq | This paper | GEO: GSExxxxx |

| Raw data of DHFL16.1JH4 HTGTS-Rep-Seq | This paper | GEO: GSExxxxx |

| Raw data of 3C-HTGTS | This paper | GEO: GSExxxxx |

| Raw data of CTCF ChIP-seq | Choi et al., 2013 | GEO: GSE47766 |

| Raw data of Rad21 ChIP-seq | Choi et al., 2013 | GEO: GSE47766 |

| Raw data of Pax5 ChIP-seq | Revilla-I-Domingo et al., 2012 | GEO: GSE38046 |

| Raw data of YY1 ChIP-seq | Medvedovic et al., 2013 | GEO: GSE43008 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| 129SV TC1 embryonic stem (ES) cells | Guo et al., 2011 | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 Rag−/− v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 VH81X-CBEdel v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 VH81X-CBEdel Rag2−/− v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 Intergenicdel v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 Intergenicdel VH81X-CBEdel v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 VH81X-CBEinv v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 VH81X-CBEinv Rag2−/− v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 VH2-2-CBEscr v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 VH2-2-CBEscr Rag2−/− v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 VH5-1-CBEins v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 VH5-1-CBEins Rag2−/− v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 IGCR1del v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 IGCR1del Rag2−/− v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 IGCR1del; VH81X-CBEdel Rag2−/− v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 IGCR1del VH5-1-CBEins v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| DHFL16.1JH4 Eμ-Bcl2 IGCR1del; VH5-1-CBEins Rag2−/− v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| Rag2−/− v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| Rag2−/− IGCR1del/del v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| Rag2−/− IGCR1del/del VH81X-CBEscr/scr v-Abl pro-B line | This paper | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| VH81X-CBEscr/scr mice | This paper | N/A |

| 129SVE mice | Taconic | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for targeting vector construction, Southern probes and PCR screening | This paper; Table S3 | N/A |

| gDNAs and ssODNs for gene targeting | This paper; Table S3 | N/A |

| Primers for HTGTS-Rep-Seq and 3C-HTGTS | This paper; Table S4 | N/A |

| Adaptors and common primers for HTGTS | Hu et al., 2016 | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 | Addgene | Cat#42230 |

| pGEM-T Easy Vector | Promega | Cat#A1360 |

| pLNTK | Guo et al., 2011 | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| HTGTS pipeline | Hu et al., 2016 | http://robinmeyers.github.io/transloc_pipeline/ |

| Bowtie2 v2.2.8 | Langmead and Salzberg, 2012 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

| MACS (2.1.0) | Zhang et al., 2008 | https://github.com/taoliu/MACS |

| GraphPad Prism 7.0 Software | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Frederick W. Alt (alt@enders.tch.harvard.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice

A 2.2-kb 5′ homology arm encompassing the VH81X gene segment sequence and containing an 18-bp scrambled mutation of VH81X-CBE that abrogates CTCF binding (Figure S2A) and a 5-kb 3′ homology arm containing sequences downstream VH81X-CBE were cloned into the pLNTK targeting vector containing a pGK-NeoR cassette (Figure S2B). 129SV TC1 embryonic stem (ES) cells were electroporated with this targeting construct and ES clones were screened for correct targeted mutations by Southern blotting and confirmed by PCR-digestion using the strategies outlined in detail in Figures S2C–S2F. Two correctly targeted ES clones were injected for germline transmission following Cre-loxP mediated deletion of the NeoR gene, one of which contributed to the germline yielding VH81X-CBEwt/scr 129SV mice, which were bred to yield VH81X-CBEscr/scr mice and their WT littermates that were used for analyses. As our targeting strategy to generate the VH81X-CBEscr allele also placed a loxP sequence 642 bp downstream of the VH81X-CBEscr mutation, we generated control mice harboring only the loxP insertion, without the VH81X-CBE scramble mutation, and found that their BM pro-B cells had VH utilization patterns that were not significantly different than those of WT (S.J., F.W.A., unpublished data). Primers used for construction of targeting vector, Southern probes and PCR screening are listed in Table S3. All animal experiments were performed under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Boston Children’s Hospital.

Cell lines

v-Abl kinase transformed pro-B cell lines were derived by retroviral infection of bone marrow cells from 4-6 weeks old mice with the pMSCV-v-Abl retrovirus, as previously described (Bredemeyer et al., 2006). Transfected cells were cultured in RPMI medium containing 15% (v/v) FBS for two months to recover stably transformed v-Abl pro-B cell lines. The “DHFL16.1JH4” line was generated by transiently inducing RAG expression in v-Abl pro-B cell lines derived from Eμ-Bcl2 transgenic mice by arresting them in G1 for 4 days by treatment with 3 μM STI-571 (Hu et al., 2015). Single cell clones were screened for VHDJH and DJH rearrangements first by PCR using degenerate VH and D primers together with a JH4 primer (Guo et al., 2011) and subsequently confirmed by Southern blotting to isolate the parental DHFL16.1JH4 line (See Figure 2A for diagrams of the DJH and non-productive VDJH alleles in the DHFL16.1JH4 line).

All mutant lines analyzed in this study (except those shown in Figure S6) were derived from this DHFL16.1JH4 parental line or its direct derivatives by Cas9/gRNA approaches (Cong et al., 2013). The VH81X-CBEdel mutant was generated by imprecise rejoining of a DSB induced by a gRNA that targets the VH81X-CBE. The VH81X-CBEinv, VH2-2-CBEscr, and VH5-1-CBEins lines were obtained by homologous recombination-mediated repair of targeted DNA breaks introduced by Cas9/gRNA with single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides (ssODNs) as template (Ran et al., 2013). The IGCR1 deletion mutants of the parental, VH81X-CBEdel and VH5-1-CBEins DHFL16.1JH4 lines were derived via a Cas9/gRNA targeting approach based on using two gRNAs specific to sites flanking the intended IGCR1 deletion. The 101-kb intergenic deletion was derived from parental and VH81X-CBEdel DHFL16.1JH4 lines using gRNAs that target sites flanking the intended deletion. At least two independent lines were derived and analyzed for each mutation studied except for the VH81X-CBEdel. However, from the same DHFL16.1JH4 parental line, we generated an additional line in which the VH81X-CBE was disrupted by a random 13-bp insertion (not shown), and found that it had VH-utilization patterns essentially identical to those of the VH81X-CBEdel line. Rag2 was deleted by the Cas9/gRNA approach mentioned above from all of the lines analyzed by 3C-HTGTS to study chromatin interactions. The v-Abl lines shown in Figure S6 were derived by retroviral infection of bone marrow cells (see above) from Rag−/− and Rag−/− VH81Xscr/scr mice, and subsequently targeted for IGCR1 deletion via the Cas9/gRNA approach. Sequences of all gRNAs and ssODNs are listed in Table S3.

METHOD DETAILS

Bone marrow pro-B cell purification

Single cell suspensions were derived from bone marrows of 4-6 weeks old mice and incubated in Red Blood Cell Lysing Buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, #R7757) to deplete the erythrocytes. Remaining cells were stained with anti-B220-APC (eBioscience, #17-0452-83), anti-CD43-PE (BD PharMingen, #553271), and anti-IgM-FITC (eBioscience, #11-5790-81) antibodies for 30 minutes at 4 C. Excess antibodies were washed off and B220+CD43highIgM− pro-B cells were isolated (Guo et al., 2011) by FACS sorting using a BD FACSARIA III cell sorter.

HTGTS-Rep-Seq to determine VH utilization frequencies

HTGTS-Rep-Seq was performed and data were analyzed with all duplicate junctions included in the analyses as previously described (Hu et al., 2016). Briefly, 2 mg of genomic DNA from sorted mouse primary pro-B cells or 50 mg of genomic DNA isolated from v-Abl lines following 4 days of G1 arrest by treatment with 3 μM STI-571, was sonicated for 25 s ON and 60 s OFF for two cycles on a Diagenode Bioruptor sonicator at low setting. Sonicated DNA was linearly amplified with a biotinylated JH4 coding end primer that anneals downstream of the JH4 segment. The biotin-labeled single-stranded DNA products were enriched with streptavidin C1 beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #65001), and 3′ ends were ligated with the bridge adaptor containing a 6-nucleotide overhang. The adaptor-ligated products were amplified by a nested JH4 coding end primer and an adaptor-complementary primer. The products were then prepared for sequencing on Illumina MiSeq platform after tagging with the P5-I5 and P7-I7 sequences (Hu et al., 2016). Junctions were aligned to AJ851868/mm9 hybrid genome by combining all of the annotated 129SV Igh sequences (AJ851868) and the distal VH sequences from the C57BL/6 background (mm9) starting from VH8-2 as described in Lin et al. (2016). The sequence of the JH4 coding end primer used for making HTGTS-Rep-Seq libraries is listed in Table S4. In primary pro-B cells, our assay recovers D-to-JH4 as well as VH-to-DJH4 junctions; whereas in the DHFL16.1JH4 rearranged v-Abl pro-B lines, we recover VH to DHFL16.1JH4 rearrangements using the JH4 baiting primer. In the DHFL16.1JH4 lines, this primer also amplifies across JH4 on the pre-rearranged VHDJH3 rearranged non-productive allele (Figure 2A); however, those reads are all filtered out as germline reads and are, thus, excluded from our V(D)J junction analyses.

As our experiments are done in G1-arrested cells, all de novo rearrangements should represent unique events. However, rearrangements at low but variable levels can occur in cycling v-Abl lines and can be well above background in some sub-clones (e.g., Alt et al., 1981) Therefore, after each HTGTS experiment, data were analyzed for high levels of recurrent Igh V(D)J junctional sequences suggestive of a pre-rearranged V(D)J rearrangement that likely occurred in cycling cells during culture. Then, if necessary, experiments were repeated on additional sub-clones that lacked evidence of obvious pre-rearrangements.

For statistical analyses, each HTGTS library plotted for comparison in a figure panel was normalized for by random selection of the number of junctions recovered from the smallest library in the comparison set. While normalization was done for statistical comparison, we note that relative VH utilization patterns were essentially same in normalized and un-normalized libraries. The numbers of junctions used for normalization of IGCR1del or 101-kb intergenicdel experiments was much higher than those shown for panels comparing WT and other mutant backgrounds due to the greatly increased levels of VH to DJH junctions recovered upon IGCR1-deletion or 101-kb intergenic deletion as described in main text and shown in Figure S5A and Table S2. The numbers of junctions recovered in each replicate experiment are listed in Table S5. Data plots show average utilization frequencies ± SD.

For v-Abl lines, the same WT data is shown in Figures 2C, 2G, 4B, 6B and their associated supplementary figures, as all mutant lines were derived from a single WT DHFL16.1JH4 parent line. As such, several different mutants were analyzed alongside the WT control in any given experiment and the WT control was simultaneously analyzed with each mutant at least once to ensure that the WT line gave the same rearrangement pattern over the course of the entire study. Final WT averages were calculated from data collected over the course of this study. We also show the same IGCR1del DHFL16.1JH4 control data in Figures 5B, S5B, S7A, and S7B, as we used the same gRNA strategy, respectively, to generate IGCR1del, IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel, and IGCR1del VH5-1-CBEins lines from the same common DHFL16.1JH4 ancestor line (as described above). The IGCR1del data is plotted as the average of experiments done along with IGCR1del VH81X-CBEdel or IGCR1del VH5-1-CBEins lines.

The non-productive fraction of VHDJH reads obtained from C57BL/6 pro-B cells shown in Figure S1 were extracted from data in a prior publication (Lin et al., 2016).

3C-HTGTS

3C libraries were generated as previously described (Splinter et al., 2012; Stadhouders et al., 2013). Briefly, 10 million cells were cross-linked with 2% (v/v) formaldehyde for 10’ at room temperature, followed by quenching with glycine at a final concentration of 125 mM. Cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors (Roche, #11836153001). Nuclei were digested with 700 units of NlaIII (NEB, #R0125) or MseI (NEB, #R0525) restriction enzyme at 37°C overnight, followed by ligation under dilute conditions at 16°C overnight. Crosslinks were reversed and samples were treated with Proteinase K (Roche, #03115852001) and RNase A (Invitrogen, #8003089) prior to DNA precipitation. The 3C libraries were sonicated for 25 s ON and 60 s OFF for two cycles on a Diagenode Bioruptor Sonicator at low setting. LAM-HTGTS libraries were then prepared and analyzed as described in “HTGTS-Rep-Seq to determine VH utilization frequencies” section (see also Hu et al., 2016) and data was aligned to AJ851868/mm9 hybrid genome as described in Lin et al. (2016) with an additional modification in which Chr12 coordinates from 114671120 to 114734564 in the AJ851868/mm9 hybrid genome were replaced with CCCCT to incorporate the DHFL16.1 to JH4 rearrangement for aligning data obtained from the DHFL16.1JH4 rearranged v-Abl pro-B lines. When using the iEm bait, we also detected interactions with distal regions beyond VH1-2P in the DHFL16.1JH4 rearranged v-Abl pro-B lines due to close linear juxtaposition of this region to iEm owing to the VHDJH rearrangement of VH1-2P on the non-productive allele. These interactions were not detected in the unrearranged v-Abl pro-B lines or primary pro-B cells as evident from data deposited in GEO database. The primers used for making 3C-HTGTS libraries are listed in Table S4. Data were plotted for comparison after normalizing junction from each experimental 3C-HTGTS library by random selection to the total number of genome-wide junctions recovered from the smallest library in the set of libraries being compared. However, chromosomal interaction patterns were very similar in normalized and un-normalized libraries.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

EMSA was performed with oligos (shown in Figure S2A) using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Catalog #20148) as per manufacturer’s protocol. 2 mg of anti-CTCF antibody from Millipore (Catalog #07-729) was used to detect super-shift.

ChIP-seq

CTCF and Rad21 ChIP-seq data were extracted from Choi et al. (2013) (GEO: GSE47766). Pax5 and YY1 ChIP-seq data was extracted from Revilla-I-Domingo et al., 2012 (GEO: GSE38046) and Medvedovic et al. (2013) (GEO: GSE43008), respectively. The ChIP-seq data were re-analyzed by aligning to mm9 and ChIP-seq peaks were called using MACS with default parameters (Zhang et al., 2008).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences between samples, ns indicates p > 0.05, * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01 and *** p ≤ 0.001.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) accession number for the datasets reported in this paper is GEO: GSE113023. Specifically, the GEO accession numbers for pro-B-HTGTS-Rep-Seq, DHFL16.1JH4-HTGTS-Rep-Seq and 3C-HTGTS datasets are GEO: GSE112781, GEO: GSE112822 and GEO: GSE113022, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

VH-CBEs greatly augment VH to DJH recombination by enhancing VH accessibility

A 3C-HTGTS assay provides high-resolution interaction profiles of Igh locus sequences

VH-CBEs promote prolonged VH interaction with the V(D)J recombination center

RAG chromatin scanning and chromatin loop extrusion share key features

Acknowledgments

We thank Hye-Suk Yoon and Arthur Su for contributions to preliminary analyses and Jeffrey Zurita for bioinformatics advice. This work was supported by NIH (AI020047). F.W.A. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. Z.B. is supported by a Cancer Research Institute Irvington Fellowship. Y.Z. is supported by a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Special Fellow Award.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes seven figures and five tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.04.035.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.J., Z.B., and F.W.A. designed the study. S.J. made the various mutant v-Abl and mouse lines and did experiments in collaboration with Z.B. who developed 3C-HTGTS. Y.Z. derived the parental DHFL16.1JH4 v-Abl transformed pro-B cell line and its IGCR1 deleted derivative. H.-Q.D. collaborated on VH to DH intergenic deletion experiments. S.J., Z.B., and F.W.A. analyzed and interpreted the data, designed figures, and wrote the manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Aiden EL, Casellas R. Somatic rearrangement in B cells: it’s (mostly) nuclear physics. Cell. 2015;162:708–711. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt F, Rosenberg N, Lewis S, Thomas E, Baltimore D. Organization and reorganization of immunoglobulin genes in A-MULV-transformed cells: rearrangement of heavy but not light chain genes. Cell. 1981;27:381–390. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt FW, Zhang Y, Meng FL, Guo C, Schwer B. Mechanisms of programmed DNA lesions and genomic instability in the immune system. Cell. 2013;152:417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner C, Isoda T, Murre C. New roles for DNA cytosine modification, eRNA, anchors, and superanchors in developing B cell progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:12776–12781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512995112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland DJ, Koohy H, Wood AL, Matheson LS, Krueger F, Stubbington MJT, Baizan-Edge A, Chovanec P, Stubbs BA, Tabbada K, et al. Two mutually exclusive local chromatin states drive efficient V(D)J recombination. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2475–2487. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossen C, Mansson R, Murre C. Chromatin topology and the regulation of antigen receptor assembly. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:337–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredemeyer AL, Sharma GG, Huang CY, Helmink BA, Walker LM, Khor KC, Nuskey B, Sullivan KE, Pandita TK, Bassing CH, Sleckman BP. ATM stabilizes DNA double-strand-break complexes during V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2006;442:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature04866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Carico Z, Shih HY, Krangel MS. A discrete chromatin loop in the mouse Tcra-Tcrd locus shapes the TCRδ and TCRα repertoires. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:1085–1093. doi: 10.1038/ni.3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NM, Loguercio S, Verma-Gaur J, Degner SC, Torkamani A, Su AI, Oltz EM, Artyomov M, Feeney AJ. Deep sequencing of the murine IgH repertoire reveals complex regulation of nonrandom V gene rearrangement frequencies. J Immunol. 2013;191:2393–2402. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, Zhang F. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit E, Vos ESM, Holwerda SJB, Valdes-Quezada C, Verstegen MJAM, Teunissen H, Splinter E, Wijchers PJ, Krijger PHL, de Laat W. CTCF binding polarity determines chromatin looping. Mol Cell. 2015;60:676–684. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degner SC, Verma-Gaur J, Wong TP, Bossen C, Iverson GM, Torkamani A, Vettermann C, Lin YC, Ju Z, Schulz D, et al. CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) and cohesin influence the genomic architecture of the Igh locus and antisense transcription in pro-B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:9566–9571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019391108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J, Mirny L. The 3D genome as moderator of chromosomal communication. Cell. 2016;164:1110–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295:1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denker A, de Laat W. The second decade of 3C technologies: detailed insights into nuclear organization. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1357–1382. doi: 10.1101/gad.281964.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JR, Selvaraj S, Yue F, Kim A, Li Y, Shen Y, Hu M, Liu JS, Ren B. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature. 2012;485:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature11082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JR, Gorkin DU, Ren B. Chromatin domains: the unit of chromosome organization. Mol Cell. 2016;62:668–680. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert A, Hill L, Busslinger M. Spatial regulation of V-(D)J recombination at antigen receptor loci. Adv Immunol. 2015;128:93–121. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frock RL, Hu J, Meyers RM, Ho YJ, Kii E, Alt FW. Genome-wide detection of DNA double-stranded breaks induced by engineered nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:179–186. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudenberg G, Imakaev M, Lu C, Goloborodko A, Abdennur N, Mirny LA. Formation of chromosomal domains by loop extrusion. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2038–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxa M, Skok J, Souabni A, Salvagiotto G, Roldan E, Busslinger M. Pax5 induces V-to-DJ rearrangements and locus contraction of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene. Genes Dev. 2004;18:411–422. doi: 10.1101/gad.291504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Yoon HS, Franklin A, Jain S, Ebert A, Cheng HL, Hansen E, Despo O, Bossen C, Vettermann C, et al. CTCF-binding elements mediate control of V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2011;477:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature10495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Xu Q, Canzio D, Shou J, Li J, Gorkin DU, Jung I, Wu H, Zhai Y, Tang Y, et al. CRISPR inversion of CTCF sites alters genome topology and enhancer/promoter function. Cell. 2015;162:900–910. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnisz D, Day DS, Young RA. Insulated neighborhoods: structural and functional units of mammalian gene control. Cell. 2016;167:1188–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Zhang Y, Zhao L, Frock RL, Du Z, Meyers RM, Meng FL, Schatz DG, Alt FW. Chromosomal loop domains direct the recombination of antigen receptor genes. Cell. 2015;163:947–959. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Meyers RM, Dong J, Panchakshari RA, Alt FW, Frock RL. Detecting DNA double-stranded breaks in mammalian genomes by linear amplification-mediated high-throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:853–871. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Lapkouski M, Yang W, Gellert M. Crystal structure of the V(D)J recombinase RAG1-RAG2. Nature. 2015;518:507–511. doi: 10.1038/nature14174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SG, Guo C, Su A, Zhang Y, Alt FW. CTCF-binding elements 1 and 2 in the Igh intergenic control region cooperatively regulate V(D) J recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:1815–1820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424936112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SG, Ba Z, Du Z, Zhang Y, Hu J, Alt FW. Highly sensitive and unbiased approach for elucidating antibody repertoires. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:7846–7851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608649113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas JS, Zhang Y, Dudko OK, Murre C. 3D trajectories adopted by coding and regulatory DNA elements: first-passage times for genomic interactions. Cell. 2014;158:339–352. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedovic J, Ebert A, Tagoh H, Tamir IM, Schwickert TA, Novatch-kova M, Sun Q, Huis In ’t Veld PJ, Guo C, Yoon HS, et al. Flexible long-range loops in the VH gene region of the Igh locus facilitate the generation of a diverse antibody repertoire. Immunity. 2013;39:229–244. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkenschlager M, Nora EP. CTCF and cohesin in genome folding and transcriptional gene regulation. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2016;17:17–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-083115-022339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols MH, Corces VG. A CTCF code for 3D genome architecture. Cell. 2015;162:703–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nora EP, Lajoie BR, Schulz EG, Giorgetti L, Okamoto I, Servant N, Piolot T, van Berkum NL, Meisig J, Sedat J, et al. Spatial partitioning of the regulatory landscape of the X-inactivation centre. Nature. 2012;485:381–385. doi: 10.1038/nature11049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nora EP, Goloborodko A, Valton AL, Gibcus JH, Uebersohn A, Abdennur N, Dekker J, Mirny LA, Bruneau BG. Targeted degradation of CTCF decouples local insulation of chromosome domains from genomic compartmentalization. Cell. 2017;169:930–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Cremins JE, Sauria MEG, Sanyal A, Gerasimova TI, Lajoie BR, Bell JSK, Ong CT, Hookway TA, Guo C, Sun Y, et al. Architectural protein subclasses shape 3D organization of genomes during lineage commitment. Cell. 2013;153:1281–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudhon C, Hao B, Raviram R, Chaumeil J, Skok JA. Long-range regulation of V(D)J recombination. Adv Immunol. 2015;128:123–182. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SSP, Huntley MH, Durand NC, Stamenova EK, Bochkov ID, Robinson JT, Sanborn AL, Machol I, Omer AD, Lander ES, Aiden EL. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. 2014;159:1665–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SSP, Huang SC, Glenn St Hilaire B, Engreitz JM, Perez EM, Kieffer-Kwon KR, Sanborn AL, Johnstone SE, Bascom GD, Bochkov ID, et al. Cohesin loss eliminates all loop domains. Cell. 2017;171:305–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revilla-I-Domingo R, Bilic I, Vilagos B, Tagoh H, Ebert A, Tamir IM, Smeenk L, Trupke J, Sommer A, Jaritz M, Busslinger M. The B-cell identity factor Pax5 regulates distinct transcriptional programmes in early and late B lymphopoiesis. EMBO J. 2012;31:3130–3146. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ru H, Chambers MG, Fu TM, Tong AB, Liao M, Wu H. Molecular mechanism of V(D)J recombination from synaptic RAG1-RAG2 complex structures. Cell. 2015;163:1138–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Velasco M, Kumar M, Lai MC, Bhat P, Solis-Pinson AB, Reyes A, Kleinsorg S, Noh KM, Gibson TJ, Zaugg JB. CTCF-mediated chromatin loops between promoter and gene body regulate alternative splicing across individuals. Cell Syst. 2017;5:628–637. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanborn AL, Rao SSP, Huang SC, Durand NC, Huntley MH, Jewett AI, Bochkov ID, Chinnappan D, Cutkosky A, Li J, et al. Chromatin extrusion explains key features of loop and domain formation in wild-type and engineered genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E6456–E6465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518552112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer W, Abdennur N, Goloborodko A, Pekowska A, Fudenberg G, Loe-Mie Y, Fonseca NA, Huber W, H Haering C, Mirny L, Spitz F. Two independent modes of chromatin organization revealed by cohesin removal. Nature. 2017;551:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature24281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splinter E, de Wit E, van de Werken HJG, Klous P, de Laat W. Determining long-range chromatin interactions for selected genomic sites using 4C-seq technology: from fixation to computation. Methods. 2012;58:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadhouders R, Kolovos P, Brouwer R, Zuin J, van den Heuvel A, Kockx C, Palstra RJ, Wendt KS, Grosveld F, van Ijcken W, Soler E. Multiplexed chromosome conformation capture sequencing for rapid genome-scale high-resolution detection of long-range chromatin interactions. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:509–524. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng G, Schatz DG. Regulation and evolution of the RAG recombinase. Adv Immunol. 2015;128:1–39. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]