Abstract

Rationale: Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) disease represents a significant threat to patients with cystic fibrosis (CF), with an estimated annual prevalence of 12%. Prior studies reported an increasing annual NTM prevalence in the general population, though similar trends in persons with CF have not been assessed.

Objectives: In this study we aimed to identify the prevalence, geographic patterns, temporal trends, and risk factors for NTM positivity by mycobacterial species among persons with CF throughout the United States.

Methods: Using annualized CF Patient Registry (CFFPR) data from 2010 to 2014, we identified patients with mycobacterial culture results to estimate the annual and period prevalence of pathogenic NTM species by demographic and geographic factors. Regression models were used to estimate the annual percent change over time and risk factors for NTM isolation. Geographic patterns were described and mapped.

Results: Of 16,153 included persons with CF, 3,211 (20%) had a pathogenic NTM species isolated at least once over the 5-year period; 1,949 (61%) had Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), and 1,249 (39%) had M. abscessus. The period prevalence was 12% for MAC (confidence interval [CI], 12–13%), 8% for M. abscessus (CI, 7–8%), and 4% for other NTM species (CI, 3.8–4.3%). The period prevalence for MAC was nearly three times greater among patients ≥60 years old with a body mass index < 19 (33% [CI, 16–51%]); this trend was not present for patients with M. abscessus (4% [CI, 0–11%]). NTM prevalence showed a significant relative increase of 5% per year, from 11.0% in 2010 to 13.4% in 2014 (P = 0.0008), although this varied by geographic area. For M. abscessus, the states with the highest prevalence were Hawaii (50%), Florida (17%), and Louisiana (16%), and for MAC they were Nevada (24%), Kansas (21%), and Hawaii and Arizona (both 20%). Study participants with either MAC or M. abscessus were significantly more likely to have been diagnosed with CF at an older age (P < 0.0001), have a lower body mass index (P < 0.0001), higher forced expiratory volume in 1 second % predicted (P < 0.01), and fewer years on chronic macrolide therapy (P < 0.0001).

Conclusions: NTM remains highly prevalent among adults and children with CF in the United States, with one in five affected, and appears to be increasing over time. Prevalence varies by geographic region and by patient-level factors, including older age and receiving an initial CF diagnosis later in life. Routine screening for NTM, including mycobacterial speciation, especially in high-risk geographic areas, is critical to increase our understanding of its epidemiology and changes in prevalence over time.

Keywords: nontuberculous mycobacteria, pulmonary, cystic fibrosis, epidemiology

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) represent an increasingly recognized cause of pulmonary-associated morbidity and mortality in the United States (1–3). Although NTM are ubiquitous in soil and water sources (4–6), NTM lung disease remains rare in the general U.S. population, with an estimated annual prevalence of 40 cases per 100,000 persons across all age groups (1, 7). In contrast, among persons with cystic fibrosis (CF), who are highly susceptible to opportunistic pathogens, the prevalence averages 12% nationally and ranges to more than 30% in some geographic regions (8), presumably from greater environmental exposure.

The prevalence of NTM appears to be increasing in the general population by approximately 8% per year in both the United States and Canada (1, 9). One recent study from Hawaii, which has the highest prevalence in the country (1), indicates that this increase may be driven solely by Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) and not by other species such as M. abscessus and the M. fortuitum group, which have been stable over time in the Hawaiian population (10). Given the observed species-specific differences in treatment options and clinical implications, with MAC being easier to treat and manage than M. abscessus (2), understanding the current epidemiologic trends and patterns exhibited by mycobacterial species within the CF population is critical.

Since 2010, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) has collected detailed mycobacterial data in their national CFF Patient Registry (CFFPR), which includes >90% of all persons with CF in the United States, facilitating longitudinal epidemiologic analyses of NTM (11). Using the CFFPR, we sought to identify species-specific trends and evaluate risk factors for NTM sputum positivity among persons with CF in the United States over a 5-year period.

Methods

Annualized CFFPR data from 2010 to 2014 were obtained from the CFF and used to estimate the prevalence of NTM by species both annually and throughout the 5-year study period. The patients included in our study population were those who had at least one mycobacterial culture performed within this study period, were over 12 years of age on average, and had no history of lung transplantation or tuberculosis. Patients under age 12 years were excluded due to differences in sputum collection and mycobacterial testing practices, which would affect any subsequent estimates. Differences in baseline characteristics between patients with and without mycobacterial cultures were determined.

NTM prevalence and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated by determining the number of persons with CF with at least one positive NTM culture out of the total number of unique patients present with mycobacterial testing within the time period evaluated (which was 1 year for annual prevalence estimates, and the entire study period for 5-year period prevalence estimates). Estimates and trends in prevalence were evaluated overall and by clinical, demographic, and geographic factors. To estimate trends by age, the age at the first NTM test during the study period was used. Species-specific analyses included all individuals with that mycobacterial species isolated, regardless of the presence of other NTM species. Trends in prevalence over time were assessed using Poisson regression models with allowance for overdispersion to calculate the annual percent change (APC). Geographic patterns were described, and maps were generated using ArcView GIS 10.2 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc.) to depict state-level differences over time. Risk factors for an NTM-positive culture by mycobacterial species were assessed using a multivariable modified Poisson regression approach with a robust error variance procedure (termed sandwich estimation) to estimate the adjusted relative risk (aRR) and 95% CIs (12). Models included all potentially relevant variables and controlled for the number of years cultured for mycobacteria, years of macrolide use, mean age, sex, and CF mutation type. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Results

CF Study Population

Overall, 16,153 (79%) of 20,347 unique persons with CF 12 years of age or older on average during the study period had at least one mycobacterial culture performed from 2010 to 2014. Patients with mycobacterial cultures who were included in this study differed from those without cultures performed across all baseline characteristics evaluated (see Table E1 in the online supplement). Among the included cohort of patients aged 12 years and older with mycobacterial cultures, annual mycobacterial culture rates increased from 47% in 2010 up to 63% in 2014. Of these, 12,500 (77%) had culture results for at least 2 years, and 3,233 (20%) had results for all 5 years (the mean number of years with culture results present was 2.9 ± 1.4).

NTM Isolations

NTM was isolated from 3,363 (21%) patients in at least one mycobacterial culture performed over the 5-year period; 3,211 (20%) patients had a pathogenic species identified and 152 (1%) were positive for M. gordonae only and were excluded from further analyses. Among the patients with NTM (Table 1), 1,949 (61%) had Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), 1,249 (39%) had M. abscessus, and 660 (21%) had other NTM species isolated at least once; 602 (19%) had multiple species isolated over time and 17 (0.5%) did not have any species reported. On average, patients with MAC were older (28.3 ± 12.8 yr) and those with M. abscessus were younger (26.2 ± 11.9 yr) than subjects without NTM (27.0 ± 11.6; P < 0.0001). Patients with MAC were less frequently homozygous for the p.Phe508del mutation (42%) compared with those without NTM or those with M. abscessus (48% for both; P = 0.005), whereas M. abscessus patients had a lower mean body mass index (BMI) (21.90 ± 3.3) than either patients with MAC (22.6 ± 3.8) or those without NTM (22.6 ± 4.0) (P < 0.0001). Patients with either MAC or M. abscessus also had other pathogens isolated at a greater frequency than NTM-negative patients, including Aspergillus spp., Candida spp., Haemophilus influenza, Staphylococcus aureus, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical and demographic characteristics of nontuberculous mycobacteria–positive and –negative persons with cystic fibrosis in the United States from 2010 to 2014

| NTM Negative(n = 12,942) | NTM Positive |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All NTM(n = 3,211) | MAC(n = 1,949) | Mycobacterium abscessus (n = 1,249) | Other Species (n = 660) | Multiple Species(n = 602) | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 48 | 49 | 50 | 48 | 49 | 49 |

| Male | 52 | 51 | 50 | 52 | 51 | 51 |

| Age group, yr* | ||||||

| 12 to <18 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 25 | 18 | 21 |

| 18 to <60 | 75 | 75 | 76 | 73 | 80 | 76 |

| ≥60 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| p.Phe508del mutation | ||||||

| Homozygous | 48 | 45 | 42 | 48 | 44 | 46 |

| Heterozygous | 39 | 42 | 44 | 39 | 42 | 41 |

| Other | 13 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 14 |

| Age at CF diagnosis, yr | ||||||

| <3 | 70 | 66 | 64 | 68 | 67 | 64 |

| 3 to <30 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 26 | 25 | 27 |

| ≥30 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| <19 | 39 | 36 | 34 | 40 | 32 | 33 |

| 19 to <25 | 45 | 49 | 50 | 49 | 52 | 53 |

| ≥25 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 12 | 17 | 14 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 20 | 19 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 16 |

| Midwest | 25 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 16 | 14 |

| South | 36 | 38 | 35 | 47 | 38 | 46 |

| West | 20 | 23 | 24 | 20 | 27 | 24 |

| Chronic macrolide use | ||||||

| 0 yr | 27 | 30 | 32 | 30 | 22 | 29 |

| 1–2 yr | 37 | 32 | 31 | 33 | 32 | 32 |

| 3–5 yr | 36 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 45 | 39 |

| Concomitant infections | ||||||

| Aspergillus spp. | 34 | 54 | 54 | 59 | 57 | 64 |

| Haemophilus influenza | 17 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 24 | 28 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 24 | 38 | 38 | 42 | 37 | 44 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 76 | 82 | 84 | 81 | 80 | 85 |

| Candida spp. | 34 | 45 | 45 | 48 | 48 | 50 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 75 | 76 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 78 |

| Burkholderia spp. | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

Definition of abbreviations: MAC = Mycobacterium avium complex; NTM = nontuberculous mycobacteria.

Age group determined based on the mean age of the patient from 2010 to 2014. To be included in the species category listed, the patient had to have at least one positive culture with that species identified.

NTM Annual Estimates and Trends

Annual NTM prevalence showed a significant relative increase of 5% per year, from 11.0% in 2010 to 13.4% in 2014 (APC, 5.3%; 95% CI, 2.1–8.5%; P = 0.0008). When trends were evaluated by age group, a significant increase in annual prevalence was noted for patients with a mean age of <40 years, rising from 10.9% in 2010 to 13.3% in 2014 (APC, 5.1%; 95% CI, 2.3–8.0%; P = 0.0003), but not for those over the age of 40 years (P = 0.07). Similarly, annual prevalence increased significantly for patients diagnosed with CF at ≤3 years of age, from 10.2% in 2010 to 12.3% in 2014 (APC, 5.0%; 95% CI, 2.2–7.8%; P = 0.0004), but not for those with an initial CF diagnosis at ≥30 years of age, and this remained relatively high across all years (20.7% in 2010 and 21.1% in 2014; P = 0.6). When evaluated by species, MAC increased significantly by 3% per year (APC, 3.0%; 95% CI, 2.1–5.8%; P = 0.03), from an annual prevalence of 5.8% in 2010 to 6.9% in 2014, whereas M. abscessus remained stable at 5.1% for all years (P = 0.9). Although the proportion of all patients with NTM and MAC remained relatively consistent over time (53% in 2010 and 51% in 2014), the proportion of those with M. abscessus decreased (from 46% in 2010 to 35% in 2014), whereas that of patients with other NTM species identified increased substantially (from 2% in 2010 to 17% in 2014). This is likely due to changes in species identification and/or reporting practices.

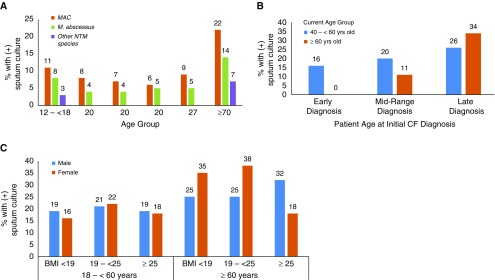

NTM Period Prevalence

The NTM 5-year period prevalence of 20% (CI, 19–20%) did not differ by sex (P > 0.4), but did by increasing patient age (Figure 1A) (19% [CI, 18–20%] for 12 to <18 years, 20% [CI, 19–21%] for 18 to <60 years, and 29% [CI, 24–34%] for ≥60 years; P = 0.0001) and by increasing age of initial CF diagnosis (19% [18–20%] for those diagnosed at ≤3 years vs. 29% [CI, 26–32%] for those diagnosed at ≥30 years; P < 0.0001). Among the oldest study participants in this cohort, NTM prevalence increased to 37% [CI, 25–50%] for those ≥70 years old (n = 59) and to 53% [CI, 28–79%] for those ≥75 years old (n = 15). When individuals ≥40 years old were evaluated, those diagnosed with CF early in life (≤3 years old) had a significantly lower NTM period prevalence (16% [CI, 13–18%]) than those diagnosed with CF later in life (≥30 years old; 29% [CI, 25–32%]) (Figure 1B). Although prevalence was similar across BMI categories overall (range of 19–21%), striking differences were noted by BMI category when stratified by sex for patients over the age of 60 years. Specifically, among women ≥60 years old with a BMI of <25, prevalence ranged from 35% to 38% (BMI <19: 35% [16–57%]; BMI 19 to <25: 38% [27–48%]), whereas for men in the same category, the prevalence was 25% (BMI <19: 25% [1–81%]; BMI 19 to <25: 25% [13–37%]). In contrast, for women ≥60 years of age with a BMI of ≥25, prevalence was only 18% (CI, 10–27%), whereas for men in the same category, it was 32% (CI, 20–45%) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Period prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) by (A) species and age group, (B) age group and age of initial cystic fibrosis (CF) diagnosis for persons over the age of 40 years, and (C) sex and body mass index (BMI) among persons with CF in the United States from 2010 to 2014. “Early diagnosis” refers to study participants who were ≤3 years old when they received their initial CF diagnosis. “Mid-range diagnosis” refers to study participants who were >3 and <30 years old when they received their initial CF diagnosis. “Late diagnosis” refers to study participants who were ≥30 years old when they received their initial CF diagnosis. MAC = Mycobacterium avium complex.

When evaluated by species, the period prevalence was 12% for MAC (CI, 12–13%), 8% for M. abscessus (CI, 7–8%), and 4% for other NTM species (CI, 3.8–4.3%). Among patients ≥60 years of age, the period prevalence of MAC increased to 20% (CI, 15–24%), but it remained similar for M. abscessus at 10% (CI, 6–13%). Within this age group (≥60 yr), the period prevalence for MAC was significantly lower among those in the highest BMI category (13% [CI, 11–13%]) compared with those in the lowest BMI category (33% [CI, 16–51%]; P < 0.0001). This trend was not present for patients with M. abscessus (BMI ≥25: 8% [CI, 3–12%]); BMI 19 to <25: 13% [CI, 7–18%]; BMI <19: 4% [CI, 0–11%]).

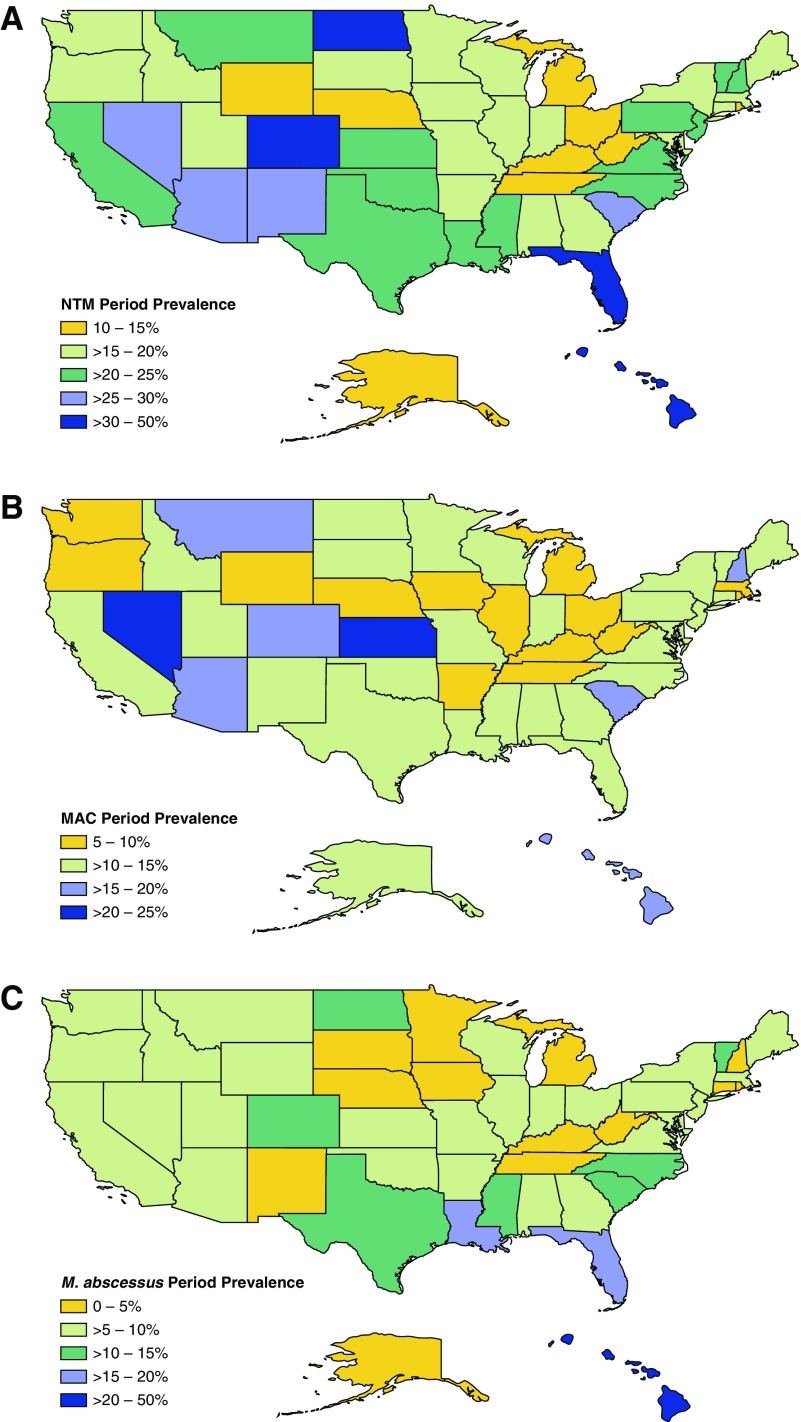

Geographic Distribution of NTM

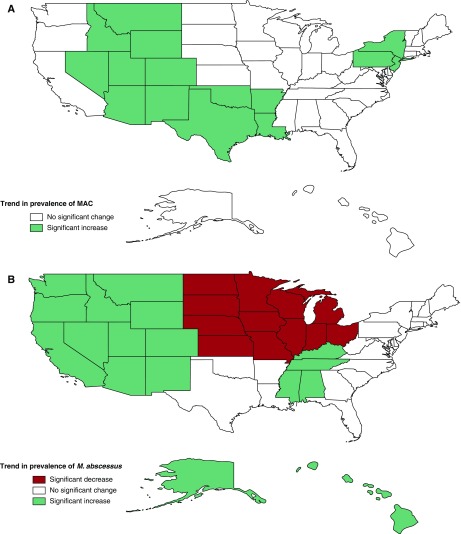

The 5-year period prevalence was estimated by state for NTM overall (Figure 2A), and by species for MAC and M. abscessus (Figures 2B and 2C, respectively). The highest NTM prevalence was detected in Hawaii (50%), followed by Florida and North Dakota (31%), and then Arizona (29%). For M. abscessus, the highest-prevalence state was Hawaii (50%), followed by Florida (17%) and then Louisiana (16%). For MAC, the greatest prevalence was in Nevada (24%), followed by Kansas (21%), and Hawaii and Arizona (both 20%). The higher NTM prevalence observed in North Dakota was driven by NTM species other than MAC and M. abscessus, for which a 17% prevalence was observed among patients residing there. Other states with a notably higher prevalence of other NTM species included Hawaii (30%), New Mexico (12%), and Iowa and Arizona (both 8%). When trends were evaluated over time by U.S. division, annual prevalence increased significantly for MAC in the Middle Atlantic states (New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania) (APC, 9.1%; CI, 0–20%) per year and in the West South-Central states (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas) (APC, 8.5%; CI, 1.3–16.2%) (Figure 3A). For M. abscessus, significant increases were observed in the East South-Central states (Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee) (APC, 12.1%, CI, 7.6–16.8%), the Pacific states (Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington) (APC, 9.7%; CI, 0.1–19.5%) and the Mountain states (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming) (APC, 8.7%; CI, 0.1–18.8%), whereas significant decreases were detected in the East North-Central states (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin) (APC, −12.6%; CI, −7.5 to −18.0%) and in the West North-Central states (Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, North Dakota, Nebraska, and South Dakota) (APC, −7.7%; CI, 0 to −16.2%) (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of the period prevalence of (A) all nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) species, (B) Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), and (C) M. abscessus isolated from persons with cystic fibrosis by state from 2010 to 2014.

This is a corrected version, posted on August 29, 2018

Figure 3.

Annual change in prevalence over time by U.S. division for (A) Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) and (B) M. abscessus isolated from persons with cystic fibrosis by state, 2010–2014. Significance considered at the P < 0.1 level.

Risk Factors for NTM by Species

Relative to study participants without NTM, those with either MAC or M. abscessus isolated at least once were significantly more likely to have received a diagnosis of CF at an older age, with each additional 5 years increasing the risk by 7% for MAC (aRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04–1.09) and by 9% for M. abscessus (aRR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.04–1.12); have a lower BMI, with each five-unit increase (kg/m2) decreasing the risk by 14% for MAC (aRR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.82–0.94) and by 32% for M. abscessus (aRR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.68–0.83); and have a higher forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) % predicted, with each five-unit increase associated with a 3% greater risk of MAC (aRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02–1.04) and 2% greater risk of M. abscessus (aRR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01–1.04) (Table 2). They also had fewer years on chronic macrolide therapy, with each additional year on macrolides decreasing risk of MAC by 23% (aRR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.79–0.84) and of M. abscessus by 28% (aRR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.75–0.80), and had more years in which at least one hospitalization occurred, with each additional year with a hospitalization increasing the risk for MAC by 4% (aRR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00–1.08) and for M. abscessus by 6% (aRR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.01–1.12) (Table 2). Individuals with MAC or M. abscessus isolated also had a higher risk of having other pathogens isolated during the study period, including an increased risk of Aspergillus spp. by 43% for those with MAC (aRR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.30–1.59) and 69% for those with M. abscessus (aRR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.48–1.93), and of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia by 25% for those with MAC (aRR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.13–1.39) and 60% for those with M. abscessus (aRR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.40–1.82) (Table 2). When differences were evaluated by species, those with M. abscessus were 64% more likely to reside in the South relative to the Midwest (aRR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.37–1.97) and 51% relative to the West (aRR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.28–1.78), and 19% less likely to be female (aRR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74–0.96). No regional or sex-specific differences in risk were detected for those with MAC, although they were 27% more likely to have S. aureus isolated (aRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.11–1.45) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable regression model results to estimate adjusted relative risks and associated 95% confidence intervals for factors associated with isolation of Mycobacterium avium complex and M. abscessus among persons with cystic fibrosis in the United States from 2010 to 2014

| Variable Assessed | MAC |

Mycobacterium abscessus |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aRR (95% CI) | P Value | aRR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Age (5-yr increase) | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 0.1 | 0.96 (0.92–1.00) | 0.1 |

| CF diagnosis age (5-yr increase) | 1.07 (1.04–1.09) | <0.0001 | 1.09 (1.04–1.12) | <0.0001 |

| BMI (five-unit increase) | 0.88 (0.82–0.94) | 0.0004 | 0.76 (0.68–0.83) | <0.0001 |

| FEV1% predicted (5% increase) | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <0.0001 | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.01 |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 1.03 (0.93–1.13) | 0.6 | 0.84 (0.74–0.96) | 0.008 |

| p.Phe508del mutation | ||||

| Homozygous | Referent | — | Referent | — |

| Heterozygous | 1.04 (0.93–1.15) | 0.5 | 0.93 (0.81–1.06) | 0.3 |

| Other | 1.07 (0.92–1.24) | 0.4 | 0.86 (0.69–1.07) | 0.2 |

| Region | ||||

| Midwest | Referent | — | Referent | — |

| Northeast | 1.04 (0.89–1.20) | 0.6 | 0.87 (0.70–1.09) | 0.2 |

| South | 1.02 (0.89–1.17) | 0.8 | 1.64 (1.37–1.97) | <0.0001 |

| West | 1.04 (0.90–1.19) | 0.6 | 1.09 (0.89–1.34) | 0.4 |

| Years on macrolides | 0.81 (0.79–0.84) | <0.0001 | 0.78 (0.75–0.80) | <0.0001 |

| Years with any hospitalization | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | 0.04 | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) | 0.02 |

| Years with cultures performed | 1.47 (1.41–1.54) | <0.0001 | 1.53 (1.43–1.62) | <0.0001 |

| Concomitant infections | ||||

| Aspergillus spp. | 1.43 (1.30–1.59) | <0.0001 | 1.69 (1.48–1.93) | <0.0001 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1.12 (0.99–1.25) | 0.06 | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) | 0.3 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) | 0.0004 | 0.88 (0.75–1.03) | 0.1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1.00 (0.89–1.13) | 0.9 | 0.96 (0.82–1.12) | 0.6 |

| Candida spp. | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 0.4 | 1.11 (0.97–1.26) | 0.1 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 1.25 (1.13–1.39) | <0.0001 | 1.60 (1.40–1.82) | <0.0001 |

Definition of abbreviations: aRR = adjusted relative risk; CI = confidence interval; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; MAC = Mycobacterium avium complex.

Discussion

With NTM increasingly being recognized as a significant cause of morbidity among persons with CF, understanding any changes in its epidemiology over time is critical for managing patient care and improving clinical outcomes (13–15). By evaluating mycobacterial culture results over a 5-year period, we identified key trends, patterns, and associations of NTM among adults and children with CF throughout the United States. Overall, the prevalence of NTM increased within this population by 5% per year during the observational study period, but this trend was significant only among those who received a diagnosis of CF early in life. This study also demonstrates that pulmonary NTM positivity remains highly prevalent among individuals with CF throughout the country, with one in five patients affected over the 5-year period. However, both prevalence and trends varied significantly by geographic region and certain patient-level factors, including older patient age and receiving a diagnosis of CF later in life.

Prior NTM studies in the CF population suggested that its prevalence increased over time, from just 1% in a limited study in 1984 (16) up to 14% across a 2-year period from 2010 to 2011 among all persons with CF in the United States (8). Here, we expand on our prior analysis (8) by evaluating mycobacterial data from the CFFPR through 2014, and demonstrate that the prevalence of NTM continued to increase slightly over this 5-year period by 5% per year, from 11% in 2010 to over 13% in 2014. However, the greatest increase in prevalence was noted between 2010 and 2012, which may be due to greater screening and reporting over time. In fact, patients with a mycobacterial culture performed increased from 47% in 2010 to 63% in 2014. It is possible that the increased prevalence observed over time is a product of these changing screening practices rather than a true increase in environmental exposure. Specifically, with universal screening for NTM, more asymptomatic patients may be captured who would have been missed in the past with more targeted screening efforts. This could also explain why an increased prevalence over time was only noted in younger persons with CF and those in whom CF had been diagnosed earlier in life, who likely were screened more broadly for NTM post-guidelines, and not in those who were older or had received their first diagnosis at more than 30 years of age—potentially even because of their NTM-positive status. Even though routine screening practices for NTM have been encouraged by the CFF since at least 2010, the implementation of these guidelines varies by facility, and therefore potentially affected the observed NTM rates when evaluated by geographic region.

In general, persons with CF who were positive for NTM, especially MAC, were more likely to have received their initial CF diagnosis after age 30, with a prevalence nearly double that of those diagnosed with CF by age 3. Even when the analysis was limited to patients over age 40, this trend persisted with a prevalence of 29% in those who had received a later-in-life diagnosis compared with 16% for those with an early diagnosis. This was previously observed by Rodman and colleagues (17), who reported that even among persons with CF over the age of 40, those in whom CF had been diagnosed later in life (median of 48 yr) had a threefold greater NTM prevalence than those diagnosed with CF early in life (median of 2 yr). It is possible that some of these older patients received their initial CF diagnosis because of their NTM-related symptoms, with infection exacerbating their otherwise undiagnosed underlying pulmonary disorder, as has been reported in limited case studies (18). Other underlying genetic differences likely exist among persons with CF who received a late-in-life diagnosis, which may additionally increase their risk for MAC lung disease. For instance, one study that evaluated 13 genetic variants of the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene among Koreans by whole-exon sequencing found that Q1352H showed a significantly higher frequency in patients with NTM than in control subjects, suggesting that this CFTR gene variant may increase susceptibility to NTM lung disease (19). Similarly, Colombo and colleagues found known CFTR genetic variants or novel mutations in 42% of 12 patients with NTM evaluated with familial disease (20), and other studies reported a prevalence of CFTR mutations among patients with pulmonary NTM ranging from 37% to 50% (21, 22). This increased prevalence of CFTR genetic mutations in cohorts of patients with NTM indicates that in persons with milder CF manifestations and a late diagnosis, other genetic factors, possibly related to the CFTR gene, may play a role in disease susceptibility. Further analyses using detailed clinical epidemiologic data are needed to determine the sequence of diagnostic events and differences in NTM risk among persons with CF.

Among study participants with NTM positivity, those with M. abscessus relative to those with MAC were younger in age and in age at initial CF diagnosis, and were more frequently homozygous for the p.Phe508del mutation, which typically reflects a more severe CF phenotype (23), although not compared with subjects without NTM. Patients with M. abscessus also had a lower mean BMI than patients with MAC and those without NTM, which can be associated with worse outcomes (24). Prior studies have demonstrated that in persons with CF, NTM pulmonary disease due to M. abscessus can result in chronic infection with worsening lung function over time relative to other mycobacterial species (25–27). Similarly, previous studies showed that MAC tended to affect older individuals, particularly over the age of 25 years, and that a greater proportion of patients with M. abscessus were younger (between the ages of 11 and 15) (27–29), again highlighting M. abscessus as being more virulent relative to other mycobacterial species. Excessive morbidity from M. abscessus is likely further exacerbated by challenges regarding treatment options, including limited data to inform best practices, concerns over inducible macrolide resistance, and the small number of well-tolerated agents that demonstrate in vitro activity against M. abscessus (26). Because of the severe clinical impact of M. abscessus on persons with CF, more frequent screening for mycobacteria should be considered for those residing in states with greater proportions of M. abscessus relative to MAC.

As was previously reported (1, 8, 30), the prevalence of NTM varied greatly by geographic region. Over the entire period, 20% of all persons with CF had NTM cultured at least once nationwide, and MAC and M. abscessus had been isolated in 61% and 39% of these patients, respectively—a distribution that is unchanged from our prior analysis (8). When evaluated by state, the highest prevalence continues to be reported in Hawaii, at 50% of all study participants residing there. Furthermore, all Hawaiian study participants with NTM had M. abscessus isolated, and 30% of them were additionally coinfected with other mycobacterial species, making these patients more challenging to treat and at greater risk for severe outcomes (2, 25, 27). The next highest-prevalence states were Florida and Arizona at approximately 30% each, although in Florida more than half of all isolates were M. abscessus, compared with only 22% in Arizona. Overall, M. abscessus continues to be much more frequently isolated in patients residing in the South Atlantic and West South-Central states, which include Florida and Louisiana, whereas MAC predominates most heavily in the Mountain states, which include Arizona and Nevada, where nearly all isolates were MAC. Further, NTM prevalence appears to be increasing over time at accelerated rates relative to the national average in certain regions, including M. abscessus in Pacific states such as Hawaii and California, and MAC in Middle Atlantic states such as New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. Additional studies are needed to determine whether these differential increases are due to changing screening practices, greater environmental exposure and altered mycobacterial ecology, and/or other patient-level factors that increase individual risk.

Numerous studies have now reported greater levels of NTM in states such as Hawaii, Florida, and Arizona both among persons with CF and in the general population (1, 8, 10, 30, 31). This is most likely due to the presence of unique environmental conditions, including soils and water sources associated with increased concentrations of mycobacteria (4, 6, 30, 32–34). Some studies have indicated that greater proximity to such environmental sources (30, 35) might contribute to an increased risk of NTM lung disease, potentially through the generation of bioaerosols containing mycobacteria (36). Our previous studies showed that factors related to a greater persistence of moisture droplets in the air, including higher saturated vapor pressure and evapotranspiration rates, were associated with an increased risk for NTM positivity (8, 30). Regional species-specific differences in prevalence (8, 30), particularly in states with higher levels of M. abscessus, are especially important to note among persons with CF given the differences in treatment and outcomes (2, 25, 27).

This study is subject to several important limitations. First, as we relied on registry data, differences in procedures and data entry across CF centers may have impacted identification of key patterns or trends. Also, although the CFFPR collects substantial clinical data, including whether a patient received chronic macrolide therapy, it does not currently capture the specific NTM treatment regimens used or drug-susceptibility test results, which limits our ability to assess trends in treatment practices or in macrolide resistance and its role in observed increases in NTM prevalence. The CFFPR also captures data on most adults and children with CF throughout the country; however, those with limited access to care may not be included or adequately represented here. These individuals may have unique differences in their risk for NTM compared with other patients included here. Additionally, given the differences in sputum collection and mycobacterial testing practices in the CF population 12 years of age and younger, we were unable to assess NTM prevalence and trends in this cohort in a manner comparable to that used for older persons with CF. Further, even among patients over age 12, those who had mycobacterial cultures performed differed from those without completed cultures, which limited our ability to extrapolate these results to all individuals with CF.

In conclusion, NTM remains a significant and highly prevalent pathogen in persons with CF throughout the nation, with one in five affected over a 5-year period. Furthermore, its prevalence is increasing at a rate similar to that observed in the general population in some geographic regions and within certain patient subgroups. Chronic macrolide use remains protective against NTM in persons with CF, although further studies are needed to evaluate trends in macrolide resistance at the population level and the role that it may play in the observed increasing prevalence. Routine screening for NTM in all persons with CF, including mycobacterial speciation and antibiotic susceptibility testing, is critical for understanding its epidemiology and better informing clinical practice to limit excess morbidity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for the use of CF Foundation Patient Registry data to conduct this study. In addition, we thank the patients, care providers, and clinic coordinators at CF centers throughout the United States for their contributions to the CF Foundation Patient Registry.

Footnotes

This is a corrected version, posted on August 21, 2018

Supported by the Divisions of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: J.A. and D.R.P. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: J.A., K.N.O., and D.R.P. Statistical analysis: J.A. Study supervision: D.R.P.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz A, Holland S, Prevots R. Prevalence of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infections among U.S. Medicare beneficiaries, 1997–2007. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:A2400. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2016OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, et al. ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee American Thoracic Society Infectious Disease Society of America An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007175367–416.[Published erratum appears in Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175:744–745.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prevots DR, Shaw PA, Strickland D, Jackson LA, Raebel MA, Blosky MA, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease prevalence at four integrated health care delivery systems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:970–976. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0310OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falkinham JO., III Nontuberculous mycobacteria in the environment. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:529–551. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(02)00014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George KL, Parker BC, Gruft H, Falkinham JO., III Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. II. Growth and survival in natural waters. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122:89–94. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falkinham JO, III, Parker BC, Gruft H. Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. I. Geographic distribution in the eastern United States. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;121:931–937. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.121.6.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strollo SE, Adjemian J, Adjemian MK, Prevots DR. The burden of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1458–1464. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201503-173OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Prevots DR. Nontuberculous mycobacteria among patients with cystic fibrosis in the United States: screening practices and environmental risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:581–586. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201405-0884OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marras TK, Mendelson D, Marchand-Austin A, May K, Jamieson FB. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease, Ontario, Canada, 1998-2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1889–1891. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.130737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adjemian J, Frankland TB, Daida YG, Honda JR, Olivier KN, Zelazny A, et al. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease and tuberculosis, Hawaii, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:439–447. doi: 10.3201/eid2303.161827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knapp EA, Fink AK, Goss CH, Sewall A, Ostrenga J, Dowd C, et al. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry: design and methods of a national observational disease registry. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1173–1179. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-781OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavalli Z, Reynaud Q, Bricca R, Nove-Josserand R, Durupt S, Reix P, et al. High incidence of non-tuberculous mycobacteria-positive cultures among adolescent with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16:579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leung JM, Olivier KN. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: the changing epidemiology and treatment challenges in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:662–669. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328365ab33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomashefski JF, Jr, Stern RC, Demko CA, Doershuk CF. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in cystic fibrosis. An autopsy study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:523–528. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith MJ, Efthimiou J, Hodson ME, Batten JC. Mycobacterial isolations in young adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 1984;39:369–375. doi: 10.1136/thx.39.5.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodman DM, Polis JM, Heltshe SL, Sontag MK, Chacon C, Rodman RV, et al. Late diagnosis defines a unique population of long-term survivors of cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:621–626. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200403-404OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haverkamp MH, van Wengen A, de Visser AW, van Kralingen KW, van Dissel JT, van de Vosse E. Pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus: a canary in the cystic fibrosis coalmine. J Infect. 2012;64:609–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang MA, Kim SY, Jeong BH, Park HY, Jeon K, Kim JW, et al. Association of CFTR gene variants with nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in a Korean population with a low prevalence of cystic fibrosis. J Hum Genet. 2013;58:298–303. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colombo RE, Hill SC, Claypool RJ, Holland SM, Olivier KN. Familial clustering of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Chest. 2010;137:629–634. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim RD, Greenberg DE, Ehrmantraut ME, Guide SV, Ding L, Shea Y, et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease: prospective study of a distinct preexisting syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1066–1074. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-686OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ziedalski TM, Kao PN, Henig NR, Jacobs SS, Ruoss SJ. Prospective analysis of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator mutations in adults with bronchiectasis or pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Chest. 2006;130:995–1002. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.4.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKone EF, Goss CH, Aitken ML. CFTR genotype as a predictor of prognosis in cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2006;130:1441–1447. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerem E, Viviani L, Zolin A, MacNeill S, Hatziagorou E, Ellemunter H, et al. ECFS Patient Registry Steering Group. Factors associated with FEV1 decline in cystic fibrosis: analysis of the ECFS patient registry. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:125–133. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00166412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esther CR, Jr, Esserman DA, Gilligan P, Kerr A, Noone PG. Chronic Mycobacterium abscessus infection and lung function decline in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2010;9:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Floto RA, Olivier KN, Saiman L, Daley CL, Herrmann JL, Nick JA, et al. US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and European Cystic Fibrosis Society. US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and European Cystic Fibrosis Society consensus recommendations for the management of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2016;71:i1–i22. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Catherinot E, Roux AL, Vibet MA, Bellis G, Ravilly S, Lemonnier L, et al. Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium abscessus complex target distinct cystic fibrosis patient subpopulations. J Cyst Fibros. 2013;12:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roux AL, Catherinot E, Ripoll F, Soismier N, Macheras E, Ravilly S, et al. Jean-Louis Herrmann for the OMA Group. Multicenter study of prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients with cystic fibrosis in France. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:4124–4128. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01257-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olivier KN, Weber DJ, Wallace RJ, Jr, Faiz AR, Lee JH, Zhang Y, et al. Nontuberculous Mycobacteria in Cystic Fibrosis Study Group. Nontuberculous mycobacteria. I: multicenter prevalence study in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:828–834. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-678OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Falkinham JO, 3rd, Holland SM, Prevots DR. Spatial clusters of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:553–558. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0913OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mirsaeidi M, Machado RF, Garcia JG, Schraufnagel DE. Nontuberculous mycobacterial disease mortality in the United States, 1999-2010: a population-based comparative study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falkinham JO, III, Norton CD, LeChevallier MW. Factors influencing numbers of Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other mycobacteria in drinking water distribution systems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1225–1231. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.3.1225-1231.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.United States Department of Agriculture. Soil survey of the territory of Hawaii: islands of Hawaii, Kauaii, Lanai, Maui, Molokai, and Oahu. Soil Survey Series. 1955;1939:1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hennessee CT, Seo JS, Alvarez AM, Li QX. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading species isolated from Hawaiian soils: Mycobacterium crocinum sp. nov., Mycobacterium pallens sp. nov., Mycobacterium rutilum sp. nov., Mycobacterium rufum sp. nov. and Mycobacterium aromaticivorans sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:378–387. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65827-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouso JM, Burns JJ, Amin R, Livingston FR, Elidemir O. Household proximity to water and nontuberculous mycobacteria in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:324–330. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazda J, Pavlik I, Falkinham JO, III, Hruska K. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 2010. The ecology of mycobacteria: impact on animal’s and human’s health. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.