Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an orphan disease characterised by autoimmunity, fibrosis of the skin and internal organs, and vasculopathy. SSc may be associated with high morbidity and mortality. In this narrative review we summarise the results of a systematic literature research, which was performed as part of the European Reference Network on Rare and Complex Connective Tissue and Musculoskeletal Diseases project, aimed at evaluating existing clinical practice guidelines or recommendations. Only in the domains ‘Vascular & Ulcers’ (ie, non-pharmacological approach to digital ulcer), ‘PAH’ (ie, screening and treatment), ‘Treatment’ and ‘Juveniles’ (ie, evaluation of juveniles with Raynaud’s phenomenon) evidence-based and consensus-based guidelines could be included. Hence there is a preponderance of unmet needs in SSc referring to the diagnosis and (non-)pharmacological treatment of several SSc-specific complications. Patients with SSc experience significant uncertainty concerning SSc-related taxonomy, management (both pharmacological and non-pharmacological) and education. Day-to-day impact of the disease (loss of self-esteem, fatigue, sexual dysfunction, and occupational, nutritional and relational problems) is underestimated and needs evaluation.

Keywords: clinical practice guidelines, ERN ReCONNET, European reference networks, systemic sclerosis, nailfold videocapillaroscopy, unmet needs

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

There is an unmet need for clinical practice guidelines in several domains in managing the systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients. A holistic management of the SSc patients will be paramount.

What does this study add?

This systematic review reports the state of the art on existing clinical guidelines and unmet needs in the management of SSc patients.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

The European Reference Network (ERN) on Rare and Complex Connective Tissue and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ReCONNET) will preceed to deliver high quality and homogeneous care for the management of SSc through development of holistic standard clinical guidelines.

Introduction

The European Reference Network (ERN) on Rare and Complex Connective Tissue and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ReCONNET) has as one of its aims to deliver high-quality and homogeneous care for the management of rare connective tissue diseases (rCTDs) across European borders through the identification and development of standard clinical guidelines and cost-effective pathways. In order to design such pathways, current existing clinical practice guidelines, more specifically recommendations or consensuses concerning management (ie, diagnosis, monitoring and treatment), need to be identified.1 One of the rCTDs covered by the ERN ReCONNET is systemic sclerosis (SSc), an orphan disease characterised by autoimmunity, fibrosis of the skin and internal organs, and vasculopathy. SSc may be associated with high morbidity and mortality.2 3 Due to its heterogeneity, it is associated with a high uncertainty for the patient who does not know what complication may occur and how to treat it. Aside from this, it is a disease which may impact the quality of life.4 5 Also for the physician SSc is challenging. Due to its rarity, it is a disease which is uncommon to non-expert rheumatologists, which may lead to late diagnosis of the disease or its complications and jeopardisation of optimal management of the patient.6 Also, a disease-modifying drug which tackles the natural evolution of the disease itself is yet to be discovered.

The objective of this paper is to report the state of the art on existing clinical practice guidelines and the unmet needs concerning the management of SSc, based on an indepth systematic literature review.

Methods

Identification of existing guidelines

We reviewed all published articles in order to identify existing clinical practice guidelines on the diagnosis, monitoring and treatment of SSc, according to the Institute of Medicine1 2011 definition (clinical practice guidelines are statements that include recommendations intended to optimise patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options).

The systematic search was performed by the ERN ReCONNET Coordinator team (RT, CAS) based on the controlled medical subject heading (MeSH) and Emtree terms for ‘systemic sclerosis’, in combination with the specification of publication type (see below).

The disease coordinators (DCs) of the ERN-ReCONNET for SSc (MM-C, VS) assigned the work on clinical practice guidelines to the healthcare providers (HCPs) involved. Moreover, in order to implement the list of guidelines provided by Medline and Embase search, the group also performed a hand search. A first screening among papers included in the final list (systematic search+hand search) based on the title and abstract selected evidence-based medicine guidelines. The electronic search was supplemented by a call to national societies and ERN ReCONNET HCPs to identify existing national guidelines, and additionally a complementary hand search to identify clinical practice guidelines through reference lists of the articles was performed by the DCs as well as by the ERN ReCONNET Coordinator team.

A general assessment of the clinical practice guidelines was performed following the Advancing Guideline Development, Reporting and Evaluation in Healthcare (AGREE) II tool checklist, not for formal appraisal but only to inform discussion. A discussion group was set for the evaluation of the existing clinical practice guidelines and to identify the unmet needs.

More specifically the following search strategy was followed:

Medline (PubMed)

(“scleroderma, systemic” (MeSH Terms) OR (“scleroderma” (All Fields) AND “systemic” (All Fields)) OR “systemic scleroderma” (All Fields) OR (“systemic” (All Fields) AND “sclerosis” (All Fields)) OR “systemic sclerosis” (All Fields)) AND (“Practice Guideline” (Publication Type) OR “Practice Guidelines As Topic” (MeSH Terms) OR Practice Guideline (Publication Type) OR “Practice Guideline” (Text Word) OR “Practice Guidelines” (Text Word) OR “Guideline” (Publication Type) OR “Guidelines As Topic” (MeSH Terms) OR Guideline (Publication Type) OR “Guideline” (Text Word) OR “Guidelines” (Text Word) OR “Consensus Development Conference” (Publication Type) OR “Consensus Development Conferences As Topic” (MeSH Terms) OR “Consensus” (MeSH Terms) OR “Consensus” (Text Word) OR “Recommendation” (Text Word) OR “Recommendations” (Text Word) OR “Best Practice” (Text Word) OR “Best Practices” (Text Word)).

Embase

(‘systemic sclerosis’/exp OR ‘generalised scleroderma’ OR ‘generalized scleroderma’ OR ‘progressive scleroderma’ OR ‘progressive sclerodermia’ OR ‘progressive sclerosis, systemic’ OR ‘progressive systemic sclerosis’ OR ‘scleroderma, generalised’ OR ‘scleroderma, generalized’ OR ‘scleroderma, progressive’ OR ‘scleroderma, systemic’ OR ‘sclerosis, progressive systemic’ OR ‘sclerosis, systemic’ OR ‘sclerosis, systemic progressive’ OR ‘systemic progressive sclerosis’ OR ‘systemic scleroderma’ OR ‘systemic sclerosis’ OR ‘systemic sclerosis, progressive’) AND (‘practice guideline’/exp OR ‘practice guideline’ OR ‘practice guidelines’/exp OR ‘practice guidelines’ OR ‘clinical practice guideline’/exp OR ‘clinical practice guideline’ OR ‘clinical practice guidelines’/exp OR ‘clinical practice guidelines’ OR ‘clinical practice guidelines as topic’/exp OR ‘clinical practice guidelines as topic’ OR ‘guideline’/exp OR ‘guideline’ OR ‘guidelines’/exp OR ‘guidelines’ OR ‘guidelines as topic’/exp OR ‘guidelines as topic’ OR ‘consensus development’/exp OR ‘consensus development’ OR ‘consensus development conference’/exp OR ‘consensus development conference’ OR ‘consensus development conferences’/exp OR ‘consensus development conferences’ OR ‘consensus development conferences as topic’/exp OR ‘consensus development conferences as topic’ OR ‘consensus’/exp OR ‘consensus’ OR ‘recommendation’ OR ‘recommendations’) AND (embase)/lim NOT (medline)/lim.

The list with identified references was independently screened at the title and abstract levels by two SSc-DCs and the ERN ReCONNET Coordinator team. References were selected for inclusion based on predefined eligibility criteria. More specifically, evidence-based medicine guidelines, recommendations or consensuses documenting the diagnosis, monitoring or treatment of SSc (according to the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) or the 2013 ACR/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria) were considered eligible.1 7 8 Subsequently, these references were classified according to SSc complications/disease manifestations, more specifically in the following domains, as decided by the SSc-DC: ‘Patients’, ‘Heart’, ‘Malignancy’, ‘Vascular & Ulcers’, ‘Gastro-intestinal (GI)’, ‘Renal’, ‘Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD)’, ‘Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH)’, ‘Diagnosis’, ‘Contribution of HCPs’, ‘Treatment’, ‘Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT)’, ‘Clinical Trials’ and ‘Juvenile’.

For preparing the state of the art of the retained full texts, the SSc-DCs sent two invitational emails to involved HCPs who had expressed their interest to participate in the guideline review. Full texts were further excluded when not meeting the inclusion criteria, as described above, in order to retain clinical practice guidelines (see table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical practice guidelines in systemic sclerosis: where do we stand?

| Domain (n) | Author and year | Level of evidence10 |

| Patients (0) | No clinical practice guidelines were included. | |

| Heart (3) | Avouac et al, 201418 | S2 |

| Bissell et al, 201719 | S2 | |

| Mavrogeni et al, 201620 | S2 | |

| Malignancy (1) | Lazzaroni et al, 201721 | S2 |

| Vascular and ulcers (6) | Baron et al, 201422 | S2 |

| Fujimoto et al, 201623 | S2 | |

| Hughes et al, 201524 | S2 | |

| Pistorius et al, 201225 | S1 | |

| Maverakis et al, 201426 | S2 | |

| Cutolo et al, 201727 | S1 | |

| Gastrointestinal (3) | Alantar et al, 201128 | S2 |

| Baron et al, 201029 | S1 | |

| Hansi et al, 201430 | S2 | |

| Renal (1) | Lynch et al, 201631 | S1 |

| Interstitial lung disease (0) | No clinical practice guidelines were included. | |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension (2) | Galiè et al, 201632 | S3 |

| Khanna et al, 201333 | S3 | |

| Diagnosis (1) | Knobler et al, 201734 | S1 |

| Contribution of healthcare providers (0) | No clinical practice guidelines were included. | |

| Treatment (5) | Kowal-Bielecka et al, 201735 | S3 |

| Denton et al, 20166 | S2 | |

| Sampaio-Barros et al, 201336 | S2 | |

| Distler et al, 201137 | S2 | |

| Knobler et al, 201438 | S2 | |

| Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (3) | Rodrigues et al, 201339 | S2 |

| Saccardi et al, 200440 | S2 | |

| Farge et al, 201741 | S2 | |

| Clinical trials (2) | Khanna et al, 201542 | S3 |

| Khanna et al, 201043 | S1 | |

| Juvenile (1) | Pain et al, 201644 | S3 |

Level of evidence: Amendment of the ‘S-class’ classification is used to describe the degree of systematic development of guidelines and thus to identify their level of evidence, by the German Association of the Scientific Medical Societies Guidance Manual and Rules for Guideline Development:10 category S3: evidence-based and consensus-based guideline, based on a representative committee, systematic review andsynthesis of evidence (highest level of evidence); category S2: evidence-based or consensus-based guideline, based on either a systematic review and synthesis of evidence or a representative committee; category S1: recommendations by expert groups, based on consensus development in an informal procedure (lowest level of evidence).

Evaluation of existing clinical practice guidelines

The first screening and informal assessment of the methodological ‘overall’ quality of each clinical practice guideline were guided by the AGREE II instrument.9 A general assessment of the state of the art on clinical practice guidelines and unmet needs identification was performed by the SSc-DCs. Additionally, the levels of evidence were assessed by the SSc Junior Coordinator team (AmV, VS) using the German Association of the Scientific Medical Societies Guidance Manual and Rules for Guideline Development (see table 1).10

Additionally, patients’ unmet needs of the Systemic Sclerosis/Scleroderma European community have been formulated by the ERN ReCONNET European Patient Advocacy Group (ePAG), that is, IG that had carefully collected the voices and the points of view of the whole European community and had found evidence in the literature.11–17 Subsequently a synthesis of these has been described by the SSc-ePAG and SSc-DCs (see the ‘Patients’ unmet needs’ section).

State of the art on clinical practice guidelines

Identification of existing guidelines

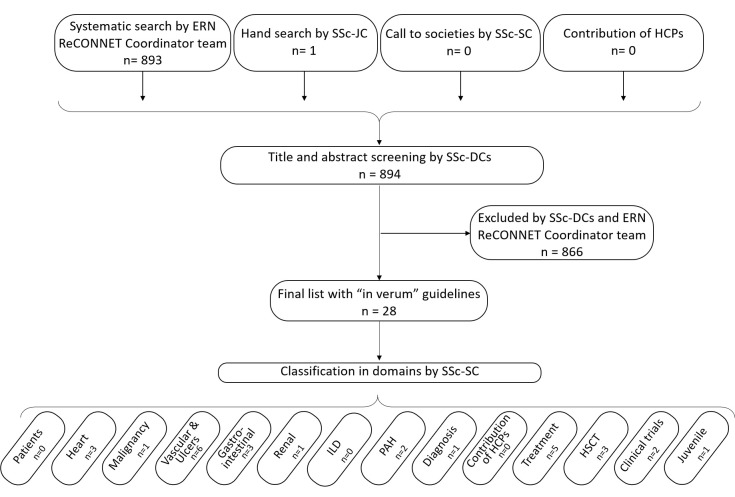

The systematic search in PubMed and Embase identified 893 references; the call to societies identified Dutch guidelines, the call to ERN-related HCPs identified no references and the hand search identified one additional reference. Of note, the Dutch guidelines were not included in the final list to be screened at the title and abstract levels since they had not yet been published in English peer-reviewed journals. Of the final list (n=894), 28 clinical practice guidelines were retained (see figure 1).6 18–44

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the screening process. ERN ReCONNET, European Reference Network Rare and Complex Connective Tissue and Musculoskeletal Diseases; DC, disease coordinators; HCP, healthcare providers; HSCT, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation; ILD, interstitial lung disease; JC, Junior Coordinator; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; SC, Senior Coordinator; SSc, systemic sclerosis.

Evaluation of existing guidelines

Overall comments of the appraisers were mostly referring to the non-systematic review aspect of the recommendations. Evaluation of the levels of evidence showed that only five guidelines were classified as strong evidence-based and consensus-based guidelines built on a representative committee, systematic review and synthesis of evidence, and will be stipulated as such below.32 33 35 42 44

Patients

Guidelines in the domain of patients are non-existent. Nevertheless, based on exhaustive patient input (IG), guidelines covering the unmet needs of the patients are highly warranted (see the ‘Patients’ unmet needs’ section).

Heart

Three references were retained in the domain ‘Heart’.

First, Avouac et al 18 proposed interim recommendations to refer patients with SSc for performing right heart catheterisation (RHC) for detecting PAH in SSc when suspected. Of note, these have now been encompassed in the highest level of evidence guideline, more specifically the 2015 European Society for Cardiology/European Respiratory Society (ESC/ESR) evidence-based and consensus-based guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension (see the ‘Pulmonary arterial hypertension’ section). Second, Bissell et al 19 presented, on behalf of the UK Scleroderma Study Group (UKSSG), a consensus best practice pathway for the management of cardiac disease, with a focus on primary heart disease in SSc. More specifically, approaches for early detection, standard pharmacological and device therapies have been put forward. Additionally, besides the recommendation for a multidisciplinary approach, a future research agenda has also been formulated in response to the relative lack of understanding of the natural history of primary cardiac disease. Third, Mavrogeni et al 20 described possible recommendations for the use of cardiac magnetic resonance in rare connective tissue diseases (rCTDs) and in between others, also in SSc.

Malignancy

One reference was retained in the domain ‘Malignancy’. More specifically, Lazzaroni et al 21 described possible recommendations for the screening for malignancies in patients with SSc with anti-RNA polymerase III. These recommendations were based on a Delphi exercise which was performed with the European League Against Rheumatism Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) experts.

Vascular and ulcers

Six references were included in the domain ‘Vascular & Ulcers’.

First, the North American Working Group regarding the classification of digital ulcers (DUs) in SSc developed a consensus for the classification of DUs, which after training of rheumatologists with SSc expertise could be used with fair reliability to classify DUs and to measure ulcer area.22 45

Second, Fujimoto et al 23 described, on behalf of the Wound/Burn Guidelines Committee of the Japanese Dermatological Association, recommendations for the management of skin ulcers associated with CTD/vasculitis. In this way, an algorithm for SSc-related ulcers was proposed, as well as a reply to frequently asked questions in the care of SSc-related ulcers. Third, Hughes et al 24 published, on behalf of the UKSSG, a best practice consensus recommendation for digital vasculopathy intended as a reference tool to inform management. In this way algorithms for the management of Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP), DUs and critical digital ischaemia in patients with SSc have been proposed.

Fourth, in the recommendations by expert groups of Pistorius et al,25 on behalf of the French Society of Vascular Medicine and the French Society for Microcirculation, clinical guidelines (more specifically clinical examination, nailfold capillaroscopy and antinuclear antibodies) as a work-up of patients with RP were defined. Besides this, a consensus-based recommendation was recently developed to diagnose RP and primary RP.26 Unfortunately, high evidence level guidelines based on the combination of a representative committee, systematic review and synthesis of evidence are lacking on the topic of primary versus secondary RP.

Interestingly, points to consider for clinical trials in SSc-associated RP have also been suggested by Cutolo et al. 27

Gastrointestinal

Three references were included concerning ‘GI’ recommendations.

Alantar et al 28 described, on behalf of a French multidisciplinary working group, recommendations for the care of oral involvement (prevention of oral and dental complications, as well as SSc-tailored dental treatment) in patients with SSc.

Baron et al 29 published, on behalf of the Canadian Scleroderma Research Group, recommendations for the screening and management of malnutrition and GI-related manifestations. Lastly, Hansi et al 30 proposed, on behalf of the UKSSG, symptom-based algorithms as a useful tool and point of reference concerning gastro-oesophageal symptoms, abdominal pain and distention, weight loss and nutritional issues, diarrhoea, incontinence and constipation.

Renal

One reference was included as recommendation in the domain ‘Renal’. More specifically, Lynch et al,31 on behalf of the UKSSG, provided recommendations for the diagnosis, including essential and supportive criteria, and management of scleroderma renal crisis (SRC).

Interstitial lung disease

No clinical practice guideline on ‘Interstitial Lung Disease’ as such, but only as part of the recommendations from the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR)/British Health Professionals in Rheumatology (BHPR) had been retained after the systematic search, stating that all SSc cases should be evaluated for lung fibrosis and that treatment is to be determined by the extent, severity and the likelihood of progression to severe disease.6

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

Two references were included in the domain ‘PAH’.32 33 Galiè et al 32 developed, on behalf of the ESC and ERS, evidence-based and consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of PAH, which recommend resting transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) as a screening test in asymptomatic patients with SSc, followed by annual screening with TTE, Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) and biomarkers. Of note, screening using the DETECT algorithm, a two-step diagnostic algorithm with clinical, laboratory, lung functional and electrocardiography parameters in step 1 and TTE in step 2, before mandating RHC to evaluate patients with SSc at risk for PAH may be considered to screen for PAH in adult patients with SSc with >3 years of disease duration and a DLCO <60% predicted. However, in an unselected SSc cohort, the performance characteristics of the DETECT algorithm do not outweigh the ESC/ERS guidelines.46 Of note, in 2013 similar screening recommendations had been recommended in SSc and scleroderma spectrum disorders in the evidence-based and consensus-based recommendations by Khanna et al.33 These latter have now been encompassed by the ESC/ESR and DETECT.

Diagnosis

Only one reference was included in the domain ‘Diagnosis’, more specifically the recommendations by the expert groups of Knobler et al,34 on behalf of the European Dermatology Forum, for the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin which encompassed SSc. The criteria for early and very early diagnosis of SSc, as well as the frequently used 2013 ACR/EULAR classification criteria, had not been retained as an in ‘verum guideline’, but are nevertheless used in the management of patients with SSc.8 47 48

Contribution of HCPs

No references were included after title and abstract screening in the domain ‘Contribution of HCPs’.

Treatment

Five references were retained in the domain ‘Treatment’.

The updated evidence-based and consensus-based EULAR recommendations of Kowal-Bielecka et al 35 focus specifically on the management of SSc features (RP, DU, PAH, skin disease, lung disease, SRC, GI disorders), and include data on newer therapeutic modalities and mention a research agenda. These recommendations are pharmacological, with few guidelines regarding investigations and non-pharmacological treatment.49 Recommendations from the BSR/BHPR are similar to the organ manifestations mentioned in the EULAR recommendations and expand on several domains of treatment, including general measures, non-pharmacological treatment, cardiac involvement, and calcinosis and musculoskeletal features.6 49 Sampaio-Barros et al had described previously, on behalf of the Brazilian Society of Rheumatology, recommendations for the management and treatment of SSc, which have been encompassed by the more recent EULAR and BSR/BHPR recommendations.6 35 36

Recommendations concerning specific therapies, more specifically the role of photopheresis and antitumour necrosis factor in SSc, have been published.37 38 Of note, these therapies have not been included in the recent EULAR or BSR/BHPR guidelines.

Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Three references were retained in the domain ‘HSCT’.

In 2013 Rodrigues et al,39 on behalf of the Brazilian Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation, developed recommendations on the use of HSCT as a treatment for SSc.

Concerning HSCT-related cardiotoxicity, consensus-based guidelines were published in 2004 and 2017. Saccardi et al 40 published a consensus statement concerning cardiotoxicity during HSCT in SSc and recommendations concerning full cardiological assessment prior to HSCT. In the consensus-based guideline of Farge et al,41 on behalf of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Autoimmune Diseases Working Party, more recent recommendations concerning the cardiopulmonary assessment of patients with SSc prior to HSCT were developed. The latter includes, besides anamnesis and clinical examination, standard haematological, biological, urinary, immunological, cardiopulmonary and GI investigations and additionally selection criteria to use HSCT in SSc.

Clinical trials

Two references were included in the domain ‘Clinical trials’ (besides the one already mentioned above in the ‘Vascular & Ulcers’ section).27 42 43

In the evidence-based and consensus-based guideline of Khanna et al,42 22 points to consider based on EULAR standards for the design of controlled clinical trials in SSc were developed.

In the recommendations by the expert groups of Khanna et al,43 preliminary recommendations for the design of future SSc-ILD randomised clinical trials were proposed.

Of note, a post-hoc search of the SSc-DCs identified several recently published ‘points to consider for clinical trials’ in the following areas: ‘Health-Related Quality-of-Life’, ‘Arthritic Involvement’, ‘GI tract’, ‘Pulmonary Hypertension’, ‘Muscle Involvement’, ‘Heart’, ‘Skin Ulcers’, ‘Renal’ and ‘Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD)’.50–58 Of note, Johnson et al 59 highlighted in 2015 recent advances in research methodology and broadened the potential range of design and analytic considerations when planning an SSc trial.

Juvenile

One reference was retained in the domain ‘Juvenile’.

In the evidence-based and consensus-based guideline of Pain et al,44 on behalf of the Paediatric Rheumatology European Society Juvenile Scleroderma Working Group, recommendations for the assessment and monitoring of RP in children were proposed.

Unmet needs identification

This is the first clinical narrative review investigating clinical practice guidelines in the field of SSc. Of all the described domains, only in the domains ‘Vascular & Ulcers’ (ie, non-pharmacological approach to DU), ‘PAH’ (ie, screening and treatment), ‘Treatment’ and ‘Juveniles’ (ie, evaluation of juveniles with RP) evidence-based and consensus-based guidelines could be included. Hence there is a preponderance of unmet needs in SSc.

Clinicians‘ unmet needs

There is a lack of (strong evidence) recommendations regarding diagnosis and (non-)pharmacological treatment of several SSc-specific complications. In particular, a contribution could be given for ulcers, GI tract involvement, renal involvement and management of calcinosis. Incentives in this field are ongoing.60 In this way, non-exhaustively, the World Scleroderma Foundation has recently proposed preliminary evidence-based and consensus-based guidelines on how to define DU.61 Nevertheless, more intensive research should be done to provide the SSc community with high evidence-based and consensus-based guidelines to address any facet of this heterogeneous disease, which could then be dispersed to policy makers at the (inter-)national level as well as to HCP and physicians dealing with this disease.

Of note, the lack of strong evidence recommendations (ie, based on a systematic review and a representative internationally composed committee and at least one patient representative) extrapolates to cross-discipline therapies such as to the use of HSCT in patients with SSc.62 In this way detailed recommendations on the main clinical features of patients with SSc are an important unmet need to be addressed in the future in connection with other institutional entities such as the EBMT, EULAR and EUSTAR. Also, clinical practice guidelines stipulating the role of steroids in SSc are highly warranted.63

At present, evidence-based and consensus-based guidelines for very early and early diagnosis of SSc still remain an unmet need, although the criteria for (very) early diagnosis are present in literature.47 48 In this area, the contribution of SSc-ERN could be to raise awareness among physicians on the problem and foster the early referral of patients to tertiary centres. Moreover, the problem to be addressed by SSc-ERN is the use of classification criteria to diagnose SSc. This highlights the absence of diagnostic criteria that are useful in practice. It is also to be noted that the dispersion (teaching and interpretation) of nailfold videocapillaroscopy (NVC) in a standardised way to early detect patients with RP who will develop SSc may be steered by both the ERN and the EULAR Study Group on Microcirculation in Rheumatic Diseases.64–66 Of note, NVC has been introduced in the ACR/EULAR criteria for SSc.8

From the methodological point of view, it is interesting to notice that the ERN ReCONNET may foster awareness of standardisation of SSc-specific investigational techniques (eg, antibody assays for SSc-specific antibodies). This may help to definitively reach an agreement on the standardised evaluation of patients with SSc.

Patients’ unmet needs

Patients with SSc experience significant uncertainty concerning SSc-related taxonomy, management (both pharmacological and non-pharmacological) due to lack of (inter-)national harmonisation and standardisation and due to non-existence of overarching evidence-based and consensus-based guidelines for holistic SSc management. Access to uniform information, including knowledgeable HCPs, and management of difficult social interactions and negative emotions are key challenges.11 Patient education programmes should be promoted.

Besides these, patients with SSc incur considerable costs (eg, non-reimbursement of certain therapies) and experience substantial deterioration in health-related quality of life (HRQoL).12 13 Additionally, no specific recommendations are at hand regarding non-pharmacological interventions (eg, behavioural/psychological, educational, physical/occupational therapy) to improve HRQoL. However, incentives like the ‘Scleroderma Patient centered Intervention Network’, which aims to develop, test and disseminate a set of accessible interventions designed to complement standard care to improve HRQoL, are encouraging.14

Importantly, patient participation in patient-reported outcome measures, meant to provide insight into the patient condition which is not fully captured by physician-derived assessment tools, has been non-prevalent even though this is paramount to ensure adequate capturing of those experiences most important to our patients.15

Last but not least, day-to-day impact of the disease (loss of self-esteem, fatigue, sexual dysfunction, and occupational, nutritional and relational problems) is underestimated.16 17

Conclusion

This indepth systematic literature review identified 28 clinical practice guidelines concerning the management of SSc. More specifically, there is an availability of evidence-based and consensus-based guidelines for screening of SSc-related PAH, treatment and points to consider in clinical trials in SSc, which are updated on a regular basis by the SSc community. Furthermore, gaps have been identified concerning patients’ needs, the role of HCPs, (very) early diagnosis of SSc, several specific organ involvements and the use of HSCT in SSc. Possible roles of the ERN ReCONNET could be to step forward to deal with patients’ unmet needs, to deal with the heterogeneity that exists in patient care throughout countries, to clearly identify at the European level the role of HCPs in the management of patients with SSc, and to step forward to the unmet need of (very) early diagnosis of the disease as well as its organ involvement, complications and management of complications, leading to a standardised, uniform holistic management of SSc.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all the members of the Steering Committee of the ERN ReCONNET for the huge commitment during this work. A special thank goes to all the members of the ERN ReCONNET team for providing support during all the phases of the Work Package 3. We thank the following HCP representatives for their contribution: Amoura Zahir, Doria Andrea, Kreps Elke, Montecucco Carlomaurizio, Schniering Janine and van Hagen P. Martin.

Vanessa Smith is Senior Clinical Investigator of the Research Foundation - Flanders (Belgium) (Fond Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek [FWO]) (grant no.:1.8.029.15N). The FWO had no involvement in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors: VS, CAS, RT: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. PA, TA, YA, CB, VC, VD, JDV-B, ADR, OD, IG, DL, GL, AM, LM, BR, AS, AT, EV, AmV, MV, FVdH, RVV, AEZ, EZ: substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data; final approval of the version to be published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. SB, MC, MM, MM-C: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. GB, FJE, CF, EH, FH, UM-L, MS, JMvL, AnV: revising the work critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This publication was funded by the European Union’s Health Programme (2014-2020).

Disclaimer: ERN ReCONNET is one of the 24 European Reference Networks (ERNs) approved by the ERN Board of Member States. The ERNs are co-funded by the European Commission. The content of this publication represents the views of the authors only and it is their sole responsibility; it cannot be considered to reflect the views of the European Commission and/or the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA) or any other body of the European Union. The European Commission and the Agency do not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

Conflicts of interest: VS, None to declare. CAS, None to declare. RT, None to declare. PA, None to declare. TA, None to declare. YA, consulted for Actelion, Bayer, Roche/Genentech, Inventiva, Medac, Pfizer, Sanofi, Servier, and UCB; and has received research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche/Genentech, Inventiva, Pfizer, Sanofi. CB, None to declare. VC, None to declare. VD, None to declare. JVB, None to declare. ADS, None to declare. OD, had consultancy relationship and/or has received research funding from Actelion, AnaMar, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Catenion, CSL Behring, ChemomAb, Roche, GSK, Inventiva, Italfarmaco, Lilly, medac, Medscape, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, and UCB in the area of potential treatments ofscleroderma and its complications. In addition, Prof. Distler has a patent mir-29 for the treatment of systemic sclerosis licensed. The real or perceived potential conflicts listed above are accurately stated. IG, None to declare. DL, None to declare. GL, None to declare. AM, None to declare. LM, None to declare. BR, None to declare. AS, None to declare. AT, None to declare. EV, None to declare. AV, None to declare. MV, None to declare. FVH, None to declare. RVV, consulted for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Biotest, BMS, Celgene, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB; and received research support and grants from AbbVie, BMS, GSK, Pfizer, UCB. AV None to declare. EZ, None to declare. SB, None to declare. GB, None to declare. FJE, None to declare. CF, None to declare. EH, None to declare. FH, None to declare. UML, None to declare. MS, None to declare. JML, None to declare. AV, None to declare. MC, None to declare. MM, None to declare. MMC, has consultancy relationship and/or has received research funding for Actelion, BMS, Celgene, Chemomab, CSL Behring, Eli Lilly and Pfizer; and is a member of the college of emeritus presidents of the Italian Society of Rheumatology (SIR).

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional unpublished data from the study.

References

- 1. Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice G Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. IOM/National Academies Press (US), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972-2002. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:940–4. 10.1136/ard.2006.066068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elhai M, Meune C, Boubaya M, et al. Mapping and predicting mortality from systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1897–905. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jaeger VK, Distler O, Maurer B, et al. Functional disability and its predictors in systemic sclerosis: a study from the DeSScipher project within the EUSTAR group. Rheumatology 2018;57:441–50. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Frantz C, Avouac J, Distler O, et al. Impaired quality of life in systemic sclerosis and patient perception of the disease: a large international survey. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;46:115–23. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Denton CP, Hughes M, Gak N, et al. BSR and BHPR guideline for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2016;55:1906–10. 10.1093/rheumatology/kew224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Masi AT, Rodnan GP, Medsger TA. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Arthritis & Rheumatism 1980;23:581–90. 10.1002/art.1780230510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1747–55. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010;182:E839–E842. 10.1503/cmaj.090449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garnier M, Champeaux E, Laurent E, et al. High-frequency ultrasound quantification of acute radiation dermatitis: pilot study of patients undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. Skin Res Technol 2017;23:602–6. 10.1111/srt.12378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Milette K, Thombs BD, Maiorino K, et al. Challenges and strategies for coping with scleroderma: implications for a scleroderma-specific self-management program. Disabil Rehabil 2018:1–10. 10.1080/09638288.2018.1470263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. López-Bastida J, Linertová R, Oliva-Moreno J, et al. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with scleroderma in Europe. Eur J Health Econ 2016;17 Suppl 1:109–17. 10.1007/s10198-016-0789-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bassel M, Hudson M, Taillefer SS, et al. Frequency and impact of symptoms experienced by patients with systemic sclerosis: results from a Canadian National Survey. Rheumatology 2011;50:762–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thombs BD, Jewett LR, Assassi S, et al. New directions for patient-centred care in scleroderma: the scleroderma patient-centred intervention network (SPIN). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012;30(2 Suppl 71):S23–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pauling JD, Frech TM, Domsic RT, et al. Patient participation in patient-reported outcome instrument development in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35 Suppl 106:184–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakayama A, Tunnicliffe DJ, Thakkar V, et al. Patients' perspectives and experiences living with systemic sclerosis: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. J Rheumatol 2016;43:1363–75. 10.3899/jrheum.151309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Decuman S, Smith V, Verhaeghe S, et al. Work participation and work transition in patients with systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatology 2012;51:297–304. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Avouac J, Huscher D, Furst DE, et al. Expert consensus for performing right heart catheterisation for suspected pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: a Delphi consensus study with cluster analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:191–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bissell LA, Anderson M, Burgess M, et al. Consensus best practice pathway of the UK Systemic Sclerosis Study group: management of cardiac disease in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2017;56:912–21. 10.1093/rheumatology/kew488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mavrogeni SI, Kitas GD, Dimitroulas T, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in rheumatology: current status and recommendations for use. Int J Cardiol 2016;217:135–48. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lazzaroni MG, Cavazzana I, Colombo E, et al. Malignancies in patients with anti-rna polymerase iii antibodies and systemic sclerosis: analysis of the EULAR scleroderma trials and research cohort and possible recommendations for screening. J Rheumatol 2017;44:639–47. 10.3899/jrheum.160817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baron M, Chung L, Gyger G, et al. Consensus opinion of a North American working group regarding the classification of digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:207–14. 10.1007/s10067-013-2460-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fujimoto M, Asano Y, Ishii T, et al. The wound/burn guidelines - 4: guidelines for the management of skin ulcers associated with connective tissue disease/vasculitis. J Dermatol 2016;43:729–57. 10.1111/1346-8138.13275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hughes M, Ong VH, Anderson ME, et al. Consensus best practice pathway of the UK scleroderma study group: digital vasculopathy in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2015;54:2015–24. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pistorius MA, Carpentier PH. le groupe de travail de la Societe francaise de medecine v. [Minimal work-up for Raynaud syndrome: a consensus report. Microcirculation working group of the french vascular medicine society]. J Mal Vasc 2012;37:207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maverakis E, Patel F, Kronenberg DG, et al. International consensus criteria for the diagnosis of Raynaud's phenomenon. J Autoimmun 2014;48-49:60–5. 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cutolo M, Smith V, Furst DE, et al. Points to consider-Raynaud's phenomenon in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2017;56(suppl_5):v45–v48. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alantar A, Cabane J, Hachulla E, et al. Recommendations for the care of oral involvement in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:1126–33. 10.1002/acr.20480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baron M, Bernier P, Côté LF, et al. Screening and therapy for malnutrition and related gastro-intestinal disorders in systemic sclerosis: recommendations of a North American expert panel. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2010;28(2 Suppl 58):S42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hansi N, Thoua N, Carulli M. Consensus best practice pathway of the UK scleroderma study group: gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014;32:S-214–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lynch BM, Stern EP, Ong V, et al. UK Scleroderma Study Group (UKSSG) guidelines on the diagnosis and management of scleroderma renal crisis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34 Suppl 100:106–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL. 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the joint task force for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension of the European society of cardiology (esc) and the european respiratory society (ERS): Endorsed by: association for European Paediatric and congenital cardiology (aepc), international society for heart and lung transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2016;37:67–119. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khanna D, Gladue H, Channick R, et al. Recommendations for screening and detection of connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:3194–201. 10.1002/art.38172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European dermatology forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, Part 1: localized scleroderma, systemic sclerosis and overlap syndromes. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31:1401–24. 10.1111/jdv.14458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kowal-Bielecka O, Fransen J, Avouac J, et al. Update of EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1327–39. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sampaio-Barros PD, Zimmermann AF, Müller CS, et al. Recommendations for the management and treatment of systemic sclerosis. Rev Bras Reumatol 2013;53:258–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Distler JH, Jordan S, Airo P, et al. Is there a role for TNFα antagonists in the treatment of SSc? EUSTAR expert consensus development using the Delphi technique. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011;29(2 Suppl 65):S40–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Knobler R, Berlin G, Calzavara-Pinton P, et al. Guidelines on the use of extracorporeal photopheresis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014;28 Suppl 1:1–37. 10.1111/jdv.12311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rodrigues MC, Hamerschlak N, de Moraes DA, et al. Guidelines of the Brazilian society of bone Marrow transplantation on hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as a treatment for the autoimmune diseases systemic sclerosis and multiple sclerosis. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter 2013;35:134–43. 10.5581/1516-8484.20130035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saccardi R, Tyndall A, Coghlan G, et al. Consensus statement concerning cardiotoxicity occurring during haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, with special reference to systemic sclerosis and multiple sclerosis. Bone Marrow Transplant 2004;34:877–81. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Farge D, Burt RK, Oliveira MC, et al. Cardiopulmonary assessment of patients with systemic sclerosis for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: recommendations from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Autoimmune Diseases Working Party and collaborating partners. Bone Marrow Transplant 2017;52:1495–503. 10.1038/bmt.2017.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Khanna D, Furst DE, Allanore Y, et al. Twenty-two points to consider for clinical trials in systemic sclerosis, based on EULAR standards. Rheumatology 2015;54:144–51. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Khanna D, Brown KK, Clements PJ, et al. Systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease-proposed recommendations for future randomized clinical trials. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2010;28(2 Suppl 58):S55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pain CE, Constantin T, Toplak N, et al. Raynaud's syndrome in children: systematic review and development of recommendations for assessment and monitoring. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34 Suppl 100:200–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cicchetti DV, Sparrow SA. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. Am J Ment Defic 1981;86:127–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vandecasteele E, Drieghe B, Melsens K, et al. Screening for pulmonary arterial hypertension in an unselected prospective systemic sclerosis cohort. Eur Respir J 2017;49:1602275 10.1183/13993003.02275-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. LeRoy EC, Medsger TA. Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1573–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Avouac J, Fransen J, Walker UA, et al. Preliminary criteria for the very early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis: results of a Delphi Consensus Study from EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:476–81. 10.1136/ard.2010.136929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pellar RE, Pope JE. Evidence-based management of systemic sclerosis: Navigating recommendations and guidelines. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;46:767–74. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Khanna D, Hays RD, Furst DE. Functional disability and other health-related quality-of-life domains: points to consider for clinical trials in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2017;56(suppl_5):v17–v22. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Clements P, Allanore Y, Furst DE, et al. Points to consider for designing trials in systemic sclerosis patients with arthritic involvement. Rheumatology 2017;56(suppl_5):v23–v26. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Furst DE, Braun-Moscovic Y, Khanna D. Points to consider for clinical trials of the gastrointestinal tract in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2017;56(suppl_5):v4–v11. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Humbert M, Singh M, Furst DE, et al. Pulmonary hypertension related to systemic sclerosis: points to consider for clinical trials. Rheumatology 2017;56(suppl_5):v33–v37. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Walker UA, Clements PJ, Allanore Y, et al. Muscle involvement in systemic sclerosis: points to consider in clinical trials. Rheumatology 2017;56(suppl_5):v38–v44. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Allanore Y, Distler O, Walker UA, et al. Points to consider when doing a trial primarily involving the heart. Rheumatology 2017;56(suppl_5):v12–v16. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Galluccio F, Allanore Y, Czirjak L, et al. Points to consider for skin ulcers in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2017;56(suppl_5):v67–v71. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Galluccio F, Müller-Ladner U, Furst DE, et al. Points to consider in renal involvement in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2017;56(suppl_5):v49–v52. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Khanna D, Seibold J, Goldin J, et al. Interstitial lung disease points to consider for clinical trials in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2017;56(suppl_5):v27–v32. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Johnson SR, Khanna D, Allanore Y, et al. Systemic sclerosis trial design moving forward. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2016;1:177–80. 10.5301/jsrd.5000198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hoa S, Stern EP, Denton CP, et al. Towards developing criteria for scleroderma renal crisis: A scoping review. Autoimmun Rev 2017;16:407–15. 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Suliman YA, Bruni C, Johnson SR, et al. Defining Skin Ulcers in Systemic Sclerosis: Systematic Literature Review and Proposed World Scleroderma Foundation (WSF) Definition. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2017;2:115–20. 10.5301/jsrd.5000236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sullivan KM, Goldmuntz EA, Keyes-Elstein L, et al. Myeloablative autologous stem-cell transplantation for severe scleroderma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:35–47. 10.1056/NEJMoa1703327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Herrick AL. Controversies on the Use of Steroids in Systemic Sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2017;2:84–91. 10.5301/jsrd.5000234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cutolo M, Sulli A, Pizzorni C, et al. Nailfold videocapillaroscopy assessment of microvascular damage in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2000;27:155–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Smith V, Beeckman S, Herrick AL, et al. An EULAR study group pilot study on reliability of simple capillaroscopic definitions to describe capillary morphology in rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology 2016;55:883–90. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cutolo M, Melsens K, Herrick AL, et al. Reliability of simple capillaroscopic definitions in describing capillary morphology in rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology 2018;57:757–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]