Abstract

Purpose

To introduce newly developed MR elastography (MRE)-based dual-saturation imaging and dual-sensitivity motion encoding schemes to directly measure in vivo skull-brain motion, and to study the skull-brain coupling in volunteers with these approaches.

Methods

Six volunteers were scanned with a high-performance compact 3T-MRI scanner. The skull-brain MRE images were obtained with a dual-saturation imaging where the skull and brain motion were acquired with fat- and water-suppression scans, respectively. A dual-sensitivity motion encoding scheme was applied to estimate the heavily wrapped phase in skull by the simultaneous acquisition of both low- and high-sensitivity phase during a single MRE exam. The low-sensitivity phase was used to guide unwrapping of the high-sensitivity phase. The amplitude and temporal phase delay of the rigid-body motion between the skull and brain was measured, and the skull-brain interface was visualized by slip interface imaging (SII).

Results

Both skull and brain motion can be successfully acquired and unwrapped. The skull-brain motion analysis demonstrated the motion transmission from the skull to the brain is attenuated in amplitude and delayed. However, this attenuation (%) and delay (rad) were considerably greater with rotation (59%±7%, 0.68±0.14rad) than with translation (92%±5%, 0.04±0.02rad). With SII the skull-brain slip interface was not completely evident, and the slip pattern was spatially heterogeneous.

Conclusion

This study provides a framework for acquiring in vivo voxel-based skull and brain displacement using MRE that can be used to characterize the skull-brain coupling system for understanding of mechanical brain protection mechanisms, which has potential to facilitate risk management for future injury.

Keywords: magnetic resonance elastography, motion, skull and brain interface, mechanical characterization, skull and brain coupling, tissue

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide with an estimated 10 million people affected annually with substantial socio-economic consequences (1,2). Although the subject of intense interest for decades, the mechanisms of injury in human TBI remain indirectly known as most studies have focused on animal experiments and computer modeling of TBI due to safety limits in human experiments (3–5). TBI occurs when the impact applied to the head exceeds the protection limits provided by the skull-brain system. Thus when attempting to understand how the skull-brain interface provides mechanical isolation of the brain and to predict the consequences of injuries to the head, interactions of the skull-brain interface need to be appropriately studied.

Recent animal experiments and simulations studies have shown that the substructures between the skull and brain interface contribute substantially to dampen pressure, transfer/bear load, and alter the distribution of the stress/strain on the cortical surface of the brain during the impact, thereby playing a critical role in isolating and protecting the brain from traumatic force (6–12). However, knowledge of the skull-brain interface coupling has remained rather limited in vivo. This is because it is difficult to directly and independently measure skull and brain motion using the standard in vivo imaging methods. In addition, the skull-brain mechanical responses from ex vivo tissue samples or in situ cadaver experiments differ significantly from those in vivo due to changes in the subarachnoid space. Therefore, developing the ability to characterize the in vivo, intact skull-brain coupling during an applied motion is critical to understand how the skull-brain interface protects the brain from the impact injuries and how this protective function might be damaged with repetitive TBI. By assessing the status of the skull-brain coupling system, it may be possible to identify individuals who are at greater risk of future injury. Moreover, studying the relative skull and brain motion may provide the basis for reliable simulation parameters when developing TBI models.

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) as a noninvasive, dynamic imaging technique that characterizes the viscoelastic properties of tissue (13). MRE has emerged as a valuable tool to study focal and diffuse brain diseases as well as changes in normal aging by characterizing the mechanical properties of brain tissue (14–22). Also, motion information obtained with MRE can be adapted to slip interface imaging (SII) to assess the degree of adhesiveness between two adjacent tissue layers (23). In MRE, dynamic mechanical vibrations (~ tens of microns) are transmitted to the brain by vibrating the head, and then phase contrast sequences using motion encoding gradients (MEGs) synchronized to the applied vibrations are performed. The transmission of motion from the MRE driver through the skull into the brain tissue is affected by the skull-brain interactions. It is thus reasonable to assume that characterization of the skull motion independent of the brain motion using MRE can provide an understanding of the skull-brain coupling resulting from the substructures between the skull and brain interface. Recent studies have utilized MRE combined with accelerometers or pressure sensors to investigate the motion transmission and attenuation through the skull to the brain (24–26). These studies provide indirect insight into in vivo brain motion relative to the skull. Although the brain motion was directly measured by MRE, the skull motion in these studies was indirectly assessed, either by accelerometers coupled to the jaw or pressure sensors placed near the acoustic actuator, both of which may be prone to measurement errors due to coupling issues.

Two main challenges exist for the measurement of skull displacement using MRE. First, there is no skull signal present in images acquired with the standard spin echo (SE) echo planar imaging (EPI)-based MRE pulse sequence. Anatomically, the skull includes an outer cortex, the medullary space, and the inner cortex. Cortical bone has an ultrashort T2 and produces no discernible signal when imaged with standard echo times (TE) (e.g., ~50 ms in EPI-MRE). Also, the signal from the medullary cavity filled with fatty marrow is suppressed because the EPI sequence typically utilizes fat-suppression to avoid chemical shift-based ghost artifacts along the phase encoding direction. Given that cortical bone imaging using ultrashort TE is technically challenging for MRE acquisitions due to the presence of MEGs, a potential strategy for detecting signal from the skull is to detect the fat signal from the fatty marrow contained within the medullary cavity. Towards this goal, we developed a dual-saturation imaging scheme to perform two separate scans – one with fat-suppression and the other with water-suppression. The first scan is used in the conventional manner to characterize mechanically-induced motion in brain tissue. The second scan is used to separately estimate the skull motion. Following reconstruction, these two distinct data sets can be studied together to reveal the interactions between the skull and brain motion.

Second, during a brain MRE acquisition, the mechanical driver is in direct contact with the head and the rigid skull experiences displacements that are considerably larger than the shear motion of brain tissue. As the motion encoding threshold of the MRE pulse sequence is set according to the expected lower shear motion of brain tissue to provide sufficient sensitivity, the motion-induced phase of the skull signal resulting from larger rigid-body displacement typically exhibits substantial wrapping in both space and time (i.e., between MRE phase offsets). A wide range of phase unwrapping algorithms have been investigated to unwrap either individual MRE wave images or the entire phase image series simultaneously (27–29). Classical unwrapping algorithms typically work well in the spatial domain, but unwrapping in time is quite challenging due to the very sparse sampling of 4 or 8 points per period in MRE, especially with heavily wrapped phase across different time points. While unwrapping failure in the skull may not affect studies focused exclusively on brain stiffness estimation, it is unacceptable for our target application. Therefore a methodology for generating wrap-free phase-based estimates of skull motion simultaneously with brain motion characterization is needed. Towards this goal, we developed a dual-sensitivity motion encoding scheme that simultaneously acquires phase images using both low- and high-motion encoding during a single MRE exam. The low-sensitivity phase image is both temporally and spatially wrap-free and thus can be used to guide unwrapping of the high-sensitivity phase image to estimate the full skull and brain motion.

Therefore, the three main objectives of our study were to 1) demonstrate a new dual-saturation imaging strategy to acquire full 3D displacement of the combined skull and brain MRE images; 2) demonstrate a novel, dual-sensitivity motion encoding scheme that facilitates robust estimation of motion-induced phase in highly challenging locations such as the skull; and 3) use these new approaches to study the skull-brain coupling in healthy volunteers.

Material and Methods

Subjects

Phantom

A polyvinyl chloride (PVC) (LureCraft Inc, Orland, Indiana, USA) cylindrical phantom (diameter: 12.25 cm, height: 12.5 cm) was used in this study to test the phase estimation performance of the dual-sensitivity motion encoding scheme.

Volunteers

With institutional review board approval, six healthy volunteers (3M/3F, Age: 35.2 ± 6.6 years) with no history of brain trauma were enrolled, and written informed consent was received from each subject.

Dual-Sensitivity Motion Encoding Scheme

In a standard steady-state MRE acquisition, the motion is encoded into the MRI phase signal by MEGs. Typically 2 sets of MEGs with the same amplitude but opposite polarity are used to acquire positive and negative phase images θ±, and phase difference images are calculated to remove any unwanted background phase and double the motion signal-to-noise-ratio (SNR) (13), which could lead to significant temporal and spatial phase wrapping. A separate MRE scan can be performed using a low MEG amplitude to achieve wrap-free phase that can be used to check the phase unwrapping (25), however, this doubles the scan time. Here we propose a dual-sensitivity motion encoding scheme (as seen in Fig. 1), in which the amplitudes of the positive and negative MEGs are slightly different. In this study, the amplitude of negative MEGs is set to be smaller than that of positive MEGs; however, the reverse setup is equally viable. As a result, the high-sensitivity phase images, Φ, can be generated in the standard manner by subtraction of the signals from the positive and negative MEGs, while the low-sensitivity phase data, φ, which will typically not exhibit any phase wrap both spatially and temporally, is calculated by adding these signals. With this strategy, both low and high motion encoding sensitivity data can be acquired simultaneously during a single exam. Since the ratio of the two sensitivities is known, the low-sensitivity data φ can be used to estimate and guide the unwrapping of high-sensitivity data Φ. The phase estimation was performed on the first temporal harmonic of the phase offsets, and then projected to each phase offset for unwrapping.

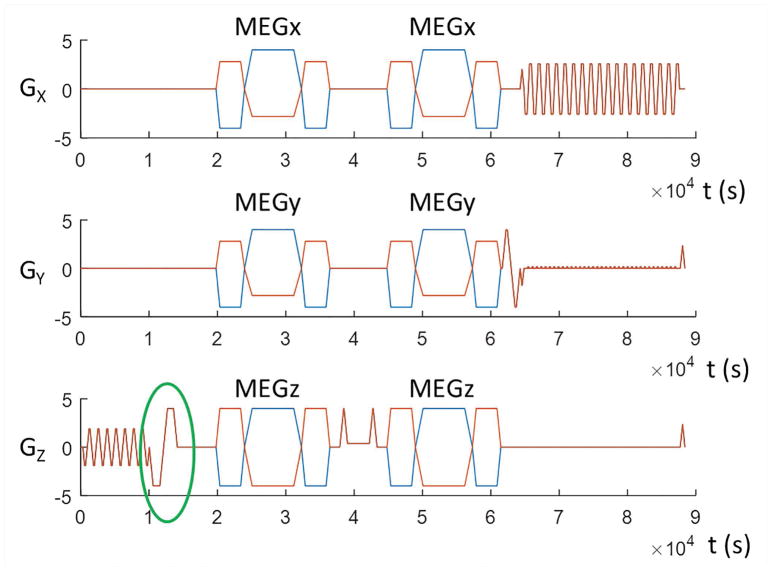

Figure 1.

The pulse sequence diagram of spin-echo (SE) echo-planar-imaging (EPI)-based MRE incorporating the dual-sensitivity motion encoding scheme. The amplitude of the negative motion encoding gradients (MEGs) (orange plot) is smaller than the amplitude of the positive MEGs (blue plot) in x- and y-directions to create the low-sensitivity encoding. The z-axis flow-compensation gradient (green oval) was used for the low-sensitivity encoding in the z-direction.

In details, in a steady-state MRE experiment with mono-directional encoding, the relation between the first harmonic component of the displacement d and the first harmonic of the time-domain phase signal θ± can be described as

| [1] |

where M is a 3×3 encoding matrix, and ± denotes the polarity of MEGs. The quantities in bold represent the complex first harmonic.

Taking all imaging gradients into account, the effective positive and negative encoding matrices can be written as

| [2] |

| [3] |

where M is the motion sensitivity of MEGs; mx, my, and mz are the motion sensitivities of x-, y-, and z-imaging gradients, respectively; k1, k2 and k3 ∈ (0,1] are the scale factors of the negative MEGs relative to the positive MEGs.

The high-sensitivity harmonic, Φ, which will typically exhibit substantial wrapping, is calculated by subtraction of the signals from the positive and negative MEGs.

| [4] |

Note that (M+ − M−) is a diagonal matrix with mx, my, and mz cancelled out.

The low-sensitivity harmonic, φ, which will typically not exhibit any spatial and temporal phase wrap, is calculated by summation of the harmonic signals as,

| [5] |

The unwanted background phase cannot be totally removed after phase summation, but it is constant over time, so it can be filtered out by taking the first temporal harmonic of the wrap-free low-sensitivity data. Since Φ and φ both linearly encode the harmonic motion d, phase synthesized from the low-sensitivity signal φ – which, by carefully selecting k, will be essentially wrap-free – can be used to guide unwrapping of the phase synthesized from the high-sensitivity signal Φ. First, an estimate of the high-sensitivity harmonic signal Φ̂syn is calculated as

| [6] |

where T is a 3×3 estimation matrix defined by

| [7] |

In the current encoding scheme (Fig. 1), mx and my are negligible. But the mandatory flow-compensation (FC) gradients in the z-axis encode some amount of motion into the low-sensitivity encoded phase φx and φy, resulting in large estimation errors if not corrected for. To address this problem, we set the amplitude of MEG±z to be equal (i.e., k3 = 1), but use the z-axis FC gradients to provide the low-motion-sensitivity. In this way, the harmonic φx and φy can then be corrected by subtracting out φz. With negligible motion encoding from other imaging gradients except for the z-FC gradients, and k1 = k2 = k, the T can be presented as

| [8] |

Of note, because the FC gradient and MEGs have different temporal phase shifts relative to the initial of vibration, mz is also a complex number, and its angle represents its relative phase delay to MEGs.

From Equations [6] and [8], the estimate of the high-sensitivity harmonic Φ̂syn from the low-sensitivity harmonic φ can then be written as,

| [9] |

The harmonics are then projected back to the time domain, and the phase maps at each phase offset are

| [10] |

where T is the period of the external vibration.

Finally, the high-sensitivity phase Φ at each phase offset can be unwrapped as,

| [11] |

where Round represents the nearest integer function.

MRE Scans

All MRE scans were performed on a recently developed compact 3T scanner. This scanner has a 26-cm diameter spherical volume and a high-performance head gradient coil with maximum gradient amplitude of 80 mT/m and slew rate of 700 T/m/s simultaneously, which allows dedicated imaging of head and extremities (30–33). Mechanical vibrations at 60-Hz were introduced into the PVC phantom using a commercially available pneumatic active driver (Resoundant Inc., Rochester, Minnesota, USA) and a custom-made rigid plastic passive driver as previously described (34). The same active driver and a soft, pillow-like passive driver positioned under the subject’s head were used to introducing 60-Hz vibrations in volunteer studies, with the main anterior-posterior (AP) excitation direction (Figure 2a) (35). The resulting full-3D displacement vector field was acquired using a modified single-shot SE-EPI-MRE pulse sequence incorporating the dual-sensitivity motion encoding scheme as shown in Figure 1. Two MRE measurements with water-selective spatial-spectral (SPSP) excitation and fat-selective SPSP excitation were performed to acquire the brain (water-dominant signal) and skull (fat-dominant signal) displacements, respectively. MEGs were applied in the positive and negative x-, y-, and z-directions. As described above, the dual-sensitivity motion encoding was achieved by setting the amplitude of the negative x- and y-MEGs as 77.7% of the amplitude of positive x- and y-MEGs while the amplitude of the negative z-MEGs remained the same as that of the positive z-MEGs. Specifically, in this study, the amplitudes of the positive and negative x- and y-MEGs were set as 50 mT/m and −38.9 mT/m (k = 0.777), respectively, resulting in a ratio of 8 between the high (6.16 μm/π-radian) and low motion encoding efficiency (49.3 μm/π-radian) in the x- and y-directions. The amplitudes of the positive and negative z-MEGs were set at ±44.4 mT/m to match the same high encoding efficiency (6.16 μm/π-radian). The low motion encoding efficiency with the z-FC gradient was 85.2 μm/π-radian, leading to a ratio of 13.9 in the z-direction. This setting ensures no phase wrapping on the low motion encoded images when the displacement is below 49.3 μm, which is a typical limit for clinical head MRE scans. For phantom validation, a separate phantom scan was performed using a standard EPI-MRE sequence with low-sensitivity MEGs to acquire the phase images with no apparent wrapping. The motion encoding efficiency of this scan was set to be equal to the low motion encoding efficiency used in dual-sensitivity encoding. The unwrapped high sensitivity phase guided by this separately acquired phantom data scan was used as the reference standard. The mean squared error between the unwrapped high-sensitivity data using two different kinds of guidance (dual-saturation scan versus separate low-MEG scan) was calculated to capture the accuracy of the guided phase unwrapping.

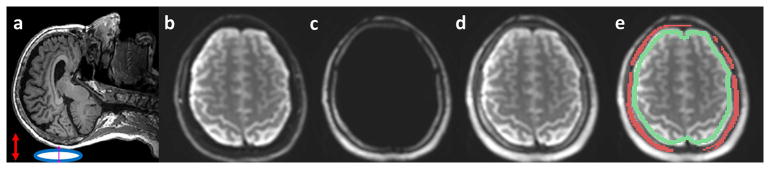

Figure 2.

(a) Brain MRE soft pillow driver positioned beneath the head (blue oval) induces vibrations in anterior-posterior (AP) direction (red arrow). (b–d) Illustration of dual-saturation imaging of a healthy volunteer in a representative slice. (b) MRE magnitude brain image acquired with the water-selective spatial-spectral (SPSP) excitation. (c) MRE magnitude image of scalp-skull acquired with the fat-selective SPSP excitation. (d) MRE magnitude image generated by combining (a) and (b). The recombined image demonstrates excellent depiction of both the skull and brain. (e) Illustration of the skull (red) and brain surface (green) ROIs for motion analysis.

The power setting for the active driver in the phantom experiment (3%) was set to produce a significant amount of phase wrapping in high-sensitivity phase images but no apparent phase wrapping in the low-sensitivity phase images. The power setting of the active driver in volunteer experiments was set to be 30%, the typical level used for clinical head MRE scans. The details of other sequence parameters include: Repetition time (TR)/TE = 4000/58.7 ms; field of view (FOV) = 24 cm; 80×80 image acquisition matrix reconstructed to 128×128; 48 contiguous 3-mm-thick axial slices; 2xASSET acceleration; 4 phase offsets sampled over one period of the 60-Hz motion; and acquisition time of 1:40 minutes for each MRE measurement.

Data Processing

Phantom Validation of Phase Estimation

The sequence performance was first tested in the phantom experiments. The high- and low-sensitivity phase images were calculated by phase subtraction and phase summation, respectively. The first harmonic time series φ was calculated from low motion encoded phase to filter out the background noise. An estimate of the high-sensitivity harmonic signal Φ̂ was then generated from φ according to Equation [9]. Real-valued phase images were then synthesized from the acquired and synthesized harmonic signals, and the latter was used to guide unwrapping of the acquired high-sensitivity signal using Equation [11].

Skull and Brain MRE Phase Estimation and Displacement Measurements

The full 3D skull and brain MRE data were generated by combining the dominant water and fat MRE data in the complex image domain using phase preserving complex combination as,

| [12] |

where Sw and Sf are the complex images acquired from two acquisitions, respectively.

The same phase estimation and guiding unwrapping procedure described above was performed. In 3 out of 6 cases, a median filter was applied to remove the isolated pixels that failed to unwrap. The x-, y-, and z- motion displacements at each MRE phase offset were then calculated from the unwrapped MRE phase.

Skull/Brain Region of Interest (ROI) Selection

Automatic segmentation was performed using the FSL Brain Extraction Tool from the Functional MRI of the Brain (FMRIB) Software Library (London, UK) to segment the combined MRE magnitude data into scalp, skull, and brain (36). A manual correction was then performed using a customized Matlab program (Mathworks, Natick, MA) to correct for the automatic segmentation errors in the skull mask by manually removing the non-skull regions. To assess the performance of combined skull and brain images, the empirical SNR of the skull signal was calculated based on skull masks overlaid onto the water-excited and combined water/fat-excited images, respectively (37). The brain mask was eroded by 1 voxel from all edges to avoid possible edge-related errors. To study the skull-brain interactions at the skull-brain interface, the brain ROI for the motion analysis was selected as a 5.6 mm wide ring (~ 3 pixels, close to the skull mask thickness) immediately interior to the edge of the brain mask (Fig. 2e). Fifteen superior slices above the region of the corpus callosum were chosen for the following analysis as these slices cover the maximal measurable skull volume and only the cerebrum.

Skull and Brain Displacement Analysis and Comparison

MRE displacements from the brain and skull ROIs were fitted to a model of rigid-body motion to obtain rigid-body translation (Tx, Ty, and Tz) and rotation (θx, θy, and θz) (25). The rigid-body fitting origin was defined as the center of mass of the brain for each volunteer. The harmonic vibrations in MRE with multiple phase offsets resulted in a set of complex translational and rotational coefficients. Several quantities were calculated to compare the skull and brain motion among 6 volunteers, including 1) the amplitude of translational and rotational motion of the skull and brain in the x-, y-, and z-directions respectively; 2) the ratios of brain to skull in the amplitude of translational and rotational motion in the x-, y-, and z-directions; 3) the 3D trajectory of translational motion of the skull and brain as well as their spatial angle (α) (25); 4) the temporal phase delay φT between the skull and brain translational motion, which was calculated as the weighted average over the x-, y-, and z- translational phase delays weighted by the amplitude of each translational component; and 5) the temporal phase delay φR between the skull and brain rotational motion calculated the same as the weighted average over the x-, y-, and z- rotational phase delays. In this study, x-, y-, and z-directions denote left-to-right (LR), anterior-to-posterior (AP), and superior-to-inferior (SI) directions, respectively.

SII of Skull/Brain Interface

The relative motion of skull and brain was also visualized by the newly developed SII technique, which can be used to detect the degree of adhesiveness between two adjacent tissue layers. This technique is based on MRE and the analysis was described previously (23). The presence of a low-friction slip interface where large differential motion exists between the two sides of the interface can be visualized as low signal intensity on the resulting shear line image.

Results

Combined Skull and Brain MRE Imaging

An example of a combined skull-plus-brain MRE image is shown in Figure 2, including brain tissue signal-only (Fig. 2b), skull signal-only (Fig. 2c), and the combined skull-plus-brain images (Fig. 2d) from a volunteer. Note that the skull signal is barely visible in Figure 2b while it is clearly depicted in Figure 2c. The recombined image with a clear depiction of the skull and brain demonstrates the feasibility of this dual-saturation imaging approach. The overall empirical SNR of the skull increased from 4.3 ± 2.4 (with fat-saturation) to 8.9 ± 0.9 (with water-saturation) averaged over 6 volunteers.

Phantom Validation of Phase Estimation

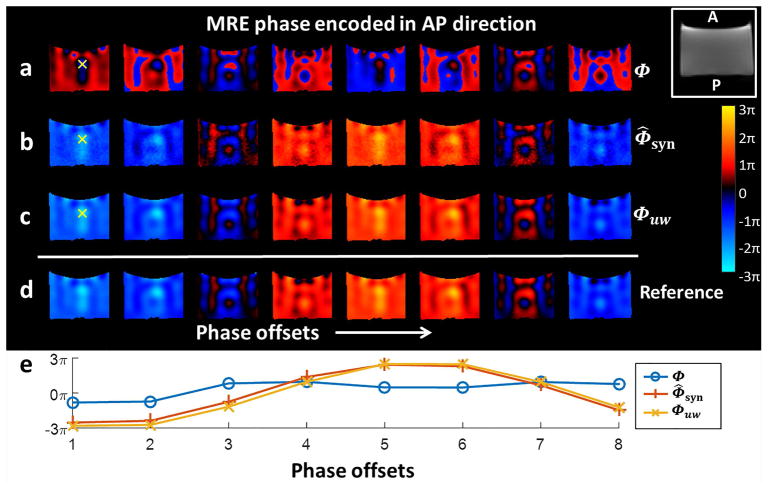

The performance of MRE phase estimation using the dual-sensitivity motion encoding scheme was tested in the PVC phantom. The high-sensitivity phase Φ calculated from phase subtraction for one slice acquired with 8 phase offsets are shown in Figure 3a, where the phase is visibly wrapped both spatially over the volume and temporally across the 8 phase offsets. Standard unwrapping algorithms typically are not able to unwrap it correctly in the time domain. In Figure 3b, the synthesized phase Φ̂syn estimated from the simultaneously acquired low-sensitivity phase data is wrap-free both temporally and spatially and can be used to guide unwrapping of Φ. The resulting unwrapped high-sensitivity phase images Φuw are illustrated in Figure 3c. Figure 3d shows the reference images as the unwrapped high-sensitivity phase guided by the separate low-MEG scans. There was no difference between Figure 3c and 3d, i.e., the mean squared error is zero.

Figure 3.

MRE phase data of the phantom showing the 8 phase offsets of (a) the wrapped high-sensitivity phase Φ encoded in AP direction (coronal plane), (b) the synthesized high-sensitivity phase Φ̂syn estimated from the low-sensitivity phase data according to Equation [9], and (c) the unwrapped phase Φuw guided by Φ̂syn according to Equation [11]. (d) The unwrapped high-sensitivity phase guided by the separate low-MEG scan as the reference standard. (e) A plot of the phase values at a single voxel (the yellow cross) over the 8 MRE phase offsets. It shows the correct harmonic nature of the phase signal in the unwrapped phase images compared to the wrapped phase.

Phase Estimation in Volunteer Studies

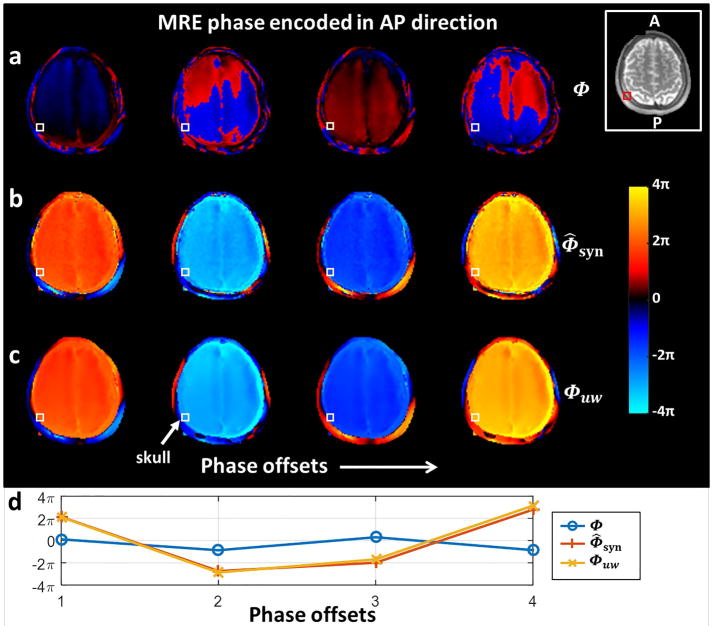

With the placement of the brain MRE driver behind the head, the main vibration is AP leading to heavily wrapped phase from motion encoded in the AP direction for both the skull and brain. In this experiment, 4 phase offsets were acquired for each volunteer and all the resulting phase images were significantly wrapped. The wrapped high-sensitivity phase images for one of the slices are shown in Figure 4a. The synthesized phase Φ̂syn estimated from the simultaneously acquired low-sensitivity phase data is shown in Figure 4b, and Figure 4c shows the unwrapped high-sensitivity phase images Φuw following the proposed unwrapping process that is guided by Φ̂syn. In Figure 4d, the large displacement of a single voxel ROI at the skull (white box in Figs. 4a–c) was correctly recovered from the wrapped phase. Note that there are three phase wraps between the last two temporal phases; conventional unwrapping algorithms simply cannot handle the high temporal phase wraps in this data due to the sparse sampling of 4 phase offsets and the substantial phase wrapping of 6π between two adjacent phase offsets.

Figure 4.

MRE phase data from a normal volunteer encoded in the AP direction (axial plane). The 4 MRE phase offsets of (a) the wrapped high-sensitivity phase Φ, (b) the synthesized high-sensitivity phase Φ̂syn estimated from the low-sensitivity phase data according to Equation [9], and (c) the unwrapped phase Φuw guided by Φ̂syn according to Equation [11]. (d) The plot of the skull phase at a single voxel (the white box) over the 4 phase offsets. It shows the correct harmonic nature of the phase signal in the unwrapped phase images compared to the wrapped phase.

Skull and Brain Displacement Comparison

Figure 5 shows the amplitude of the rigid body translational and rotational motion of the skull and brain estimated from the MRE data for each volunteer. The MRE pillow driver positioned at the back of the head vibrated in the AP direction, resulting in a head pivoting about the neck, i.e., a nodding motion of the head including a combination of translational motion in the AP direction and rotation about the LR axis. As expected, the largest translational and rotational motions were measured for the AP and LR directions respectively for both the skull and brain, though variations were observed among the 6 volunteers, possibly due to the differences in positioning the MRE driver. The amplitude of the skull rigid body motion is larger than that of the brain for all translational and rotational components. We found that the amplitude of the translational motion from the skull to the brain was slightly reduced (Fig. 5a), whereas the amplitude of the rotational motion was greatly reduced (Fig. 5b). The mean ratios of brain amplitude to skull amplitude in the dominant components of translation (TAP) and rotation (θLR) were 92% ± 5% and 59% ± 7%, respectively (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5.

The amplitude of the rigid body (a) translational and (b) rotational motion of the skull and the brain at the x- (LR: left-right), y- (AP: anterior-posterior), and z- (SI: superior-inferior)-directions for six volunteers. (c) The brain-to-skull amplitude ratio of the dominant components of translation (TAP) and rotation (θLR).

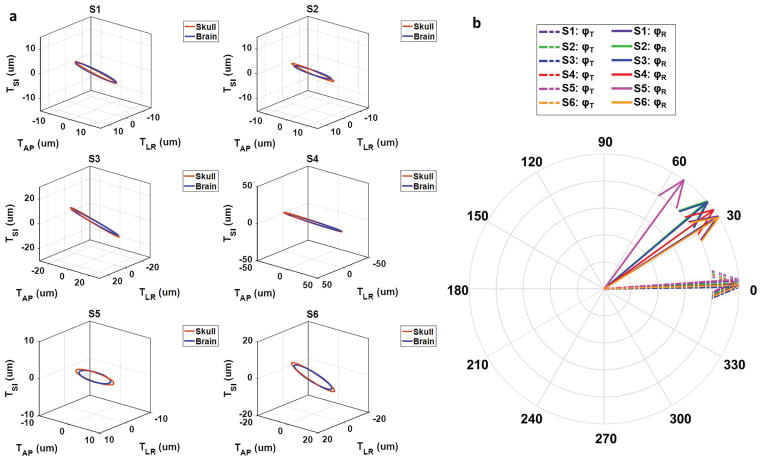

The motion trajectories further demonstrated similar patterns of the skull and brain in translational motion. Given that the harmonic motion of the AP, LR, and SI components are not in phase, the 3D trajectories of skull and brain translational motion are represented as ellipses in Figure 6a, and the amplitudes are clearly similar and the normals to the elliptical trajectories of the skull and brain differ by very small spatial angles α (Table 1). The temporal phase delays (φT and φR) between the skull and brain motion for each volunteer are shown in Figure 6b and listed in Table 1. A short temporal phase delay φT between the skull and brain translational motion was measured (0.04 ± 0.02 rad). In contrast, the phase delay φR between the skull and brain rotational motion was much longer (0.68 ± 0.14 rad) than that of the translational component.

Figure 6.

(a) The 3D translational motion trajectories of the skull and brain for each volunteer. (b) The temporal phase delays (translation: φT and rotation: φR) between the skull and brain motion for each volunteer.

Table 1.

Spatial angle (α) and temporal phase delay (φT) between the harmonic translational motion of the skull and brain as well as temporal phase delay (φR) between the harmonic rotational motion of the skull and brain for each volunteer.

| Volunteers | α (rad) | φT (rad) | φR (rad) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.57 |

| S2 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.71 |

| S3 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.70 |

| S4 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.63 |

| S5 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.94 |

| S6 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.56 |

SII of Skull-Brain Interface

Figure 7 shows SII results of two representative slices from all 6 volunteers, which qualitatively visualize the relative motion between the skull and brain. In shear line images, low-intensity lines indicate a relatively slippery interface where large differential motion exists between the two sides of the interface. As shown in all volunteers, a clear dark line was observed along the scalp-skull interface (yellow arrows), indicating a complete slip interface between the scalp and the skull. In volunteers 3–5, there is a loss of signal throughout much of the subcutaneous tissue. This may be partly due to the thicker scalp tissue (predominately fatty) in which slip is apparently occurring throughout the subcutaneous region, and partly due to the higher wave amplitude in the scalp tissue that creates large intravoxel phase dispersion. In contrast, fainter dark lines were only partly observed along the skull-brain interface (green arrows), indicating less differential motion between the skull and adjacent brain compared to the scalp-skull interface. We also found that the skull-brain slip interface is spatially heterogeneous, both within the individual volunteer and across the 6 volunteers.

Figure 7.

Slip interface imaging (SII) results of 6 volunteers. Two representative slices are shown for each volunteer. The low-intensity lines in shear line images (right column) at the scalp-skull interface (yellow arrows) and skull-brain interface (green arrows) indicate a relatively slippery interface where large differential motion exists between the two sides of the interface. The loss of signal in scalp tissue in volunteers 3–5 may be partly due to apparent slip occurring throughout the subcutaneous fatty tissue, which is often observed in subjects with thicker scalp tissue, and partly due to large intravoxel phase dispersion induced by the higher wave amplitude in the scalp tissue.

Discussion

We have developed a dual-saturation, dual-sensitivity motion encoding MRE imaging technique and demonstrated it as an effective tool for measuring 3D in vivo skull and brain motion during small-scale dynamic head vibrations. We estimated the full head motion and measured the skull and brain displacement on a voxel basis. The amplitude and temporal phase delay of the rigid body motion between the skull and brain was compared and the skull-brain slip interface was visualized by SII to assess the relative skull-brain motion. A comparison of the brain motion relative to the skull in vivo clearly demonstrated that the skull-brain interface both attenuates and delays motion transmission into the brain and hence expands our understanding of the skull-brain coupling mechanisms.

The skull is almost always represented as a signal void on the standard MRE-EPI image which utilizes on-resonance water excitation and fat suppression. By using a water-suppressed acquisition, the middle layer of the skull, i.e., the medullary cavity filled with fatty marrow, has adequate signal to be analyzed and used to track skull motion. As there will be some water-based signal within the medullary cavity, the dominantly fat and dominantly water images should be combined by phase preserving complex multiplication rather than direct summation, to give a more accurate characterization of the combined signal.

By using the proposed dual-sensitivity motion encoded acquisition strategy and guided phase unwrapping procedure, wrap-free estimates of both skull and brain phase signals were successfully generated even when only 4 MRE phase offsets were acquired, a scenario where conventional phase unwrapping algorithms often fail. For example, in our study in Figure 4, there are three 2π phase wraps between the last two temporal phases; unwrapping this in the time domain is mathematically undetermined without prior knowledge. Our technique was able to solve this problem by providing such prior knowledge, i.e., temporally and spatially wrap-free low-sensitivity phase data, thus the true phase can be estimated. In the current scheme, the low-sensitivity motion in the z-direction was actually encoded by the FC gradient rather than by derating the z-MEGs. Consequently, the ratio of the high to low-sensitivity in z-direction varies depending on the slice thickness and the MEG frequency chosen. The encoding ratio used in this study was 13.9 in the z-direction, slightly larger than the ratios in the x- and y-directions (8.0). However, this unbalanced ratio did not have a significant practical effect on the performance of either skull or brain phase estimation. It should be noted that some of the phase maps generated with the proposed approach show discontinuities in certain scalp regions. This is because the dual-sensitivity encoding efficiency was optimized for the skull and brain, targeting generation of low-sensitivity phase images with no apparent wrapping. On occasion, scalp motion was so large that the phase signal in this area was still wrapped even when the low-sensitivity motion encoding was used.

The idea of unwrapping the phase-aliased data by referring to non-aliased data has been proposed in other applications. For example, multiple MRI studies have used dual velocity encoding (VENC) to unwrap the phase data in phase contrast MRI (38–40); Badachhape et al.’s MRE studies also used MRE data acquired at lower MEGs as a template to check the unwrapped solution for the waveform at higher MEGs (25,26). However, these approaches typically require consecutive scans to acquire the low and high phase data which will double the scan time. The dual-sensitivity motion encoding scheme proposed in this study simultaneously acquires high and low-sensitivity phase images in one MRE exam, enabling a robust phase estimate while maintaining the same scan time.

In this work, the subjects experienced vertically directed (AP) extracranial vibrations from the MRE driver at 60-Hz. The pattern of the relative brain motion with respect to the skull was first studied in terms of rigid-body translation and rotation. Our results show that the motion amplitude was attenuated by the transmission from the skull to the brain, and that brain motion lags behind the motion of the skull. However, different patterns exist in rotation and translation. The translational motion of the brain was slightly smaller in amplitude and slightly lagged behind the skull (0.04 rad). However, the rotation of the brain was considerably different from that of the skull with much lower motion amplitude and longer temporal phase delay (0.68 rad). This may indicate that the skull-brain interface system (consisting of cerebrospinal fluid, arachnoid trabeculae, and subarachnoid vasculature located between the arachnoid and pia mater membranes) acts differently when transmitting translational and rotational motion. It may significantly attenuate and delay the rotational motion that is potentially more harmful in regard to brain injury (41). Of note, this observation was found under a small dynamic vibration that resulted in motion amplitude in the range of tens of microns, and brain ROIs were selected as thin rings immediately adjacent to the skull. This finding is not completely consistent with Badachhape et al.’s MRE studies in which the excitation frequency is 50-Hz and the skull motion was indirectly reconstructed from the acceleration data that was acquired from an array of accelerometers fixed to the skull via a mouth guard (25,26). Their study found that both translation and rotation of the brain were largely different from the skull. The discrepancies may be due to the different frequency of excitation (50-Hz versus 60-Hz) and different approaches to measuring the skull motion.

As expected, motion amplitude and phase delays vary among individual subjects, which may be partly due to the different coupling between the subject’s head and the driver, the anatomical differences in the skull and brain for each individual as well as the effect of subcutaneous tissue. Such variation can be visualized in the SII results. The SII technique was originally developed to detect tumor adherence based on differences between the tumor and adjacent brain motion under applied MRE vibrations (23,29). Here, its application was extended to assess the “adhesiveness” of the skull-brain interface, i.e., to assess the differential motion between the skull and adjacent brain. The larger the amount of relative motion, the more intravoxel phase dispersion is induced, and hence more signal attenuation is detected at the interface. Interestingly, we found that under our experimental loadings, the slip interface between the skull and brain does not appear to be completely evident, and the slip pattern is spatially heterogeneous. This suggests that different areas of the interface may be mechanically different. An animal study using optical coherence tomography to characterize the microstructure of the pia-arachnoid complex has demonstrated the within-brain variability of the arachnoid trabeculae and subarachnoid vasculature (8). Although we applied the same vibration frequency and tried to deliver the same amplitude of motion to each patient, the differences in positioning the MRE head driver could introduce variations among different subjects, which may affect our assessment of the slip interface. Further studies will work on developing an advanced SII normalization method to quantify the amount of slip.

Although Badachhape et al.’s MRE study has explored the usefulness of scalp motion to estimate the skull motion (26), we have observed there appears to exist a complete slip interface between the scalp and skull, suggesting that the scalp and skull move independently for the motion induced with the experiment. As a result, we believe that the scalp motion may not be an accurate surrogate measure of skull motion.

This study represents the first application of the proposed MRE data acquisition and processing technologies, and there are several limitations. First, the dominant water and fat images were acquired in serial but separate scans. In the cases of patient head movement between the two scans, there could be uncorrected misregistration errors. Also, B0 field inhomogeneity due to patient-based susceptibility effects or suboptimal pre-scan gradient shimming could result in incomplete water or fat saturation when using suppression pulses. Improvements in pulse sequence programming, including simultaneous fat/water imaging using a multi-echo acquisition with Dixon-type post-processing, may address these issues in the future. Second, the dual-sensitivity motion encoding scheme as currently implemented may not be applicable for some advanced MRE encoding approaches requiring simultaneous x-, y-, and z- motion encoding. However, the proposed framework could be generalized for such scenarios with relatively minor mathematical modification. Third, the sample size in this study is limited. A larger number of volunteer and patient studies with a wide range of age/gender distribution and TBI history would need to be evaluated to determine if the motion patterns observed in this study are representative and if the changes of these patterns are associated with prior and/or repetitive head trauma. Fourth, the results measured in this study may be limited to the single vibration direction (AP) and the single frequency (60-Hz) applied. It is expected that the skull-brain coupling will be sensitive to the vibrational direction and frequency (42,43). Future MRE studies that use multi-excitation drivers vibrating the head in different directions and frequencies may help to further elucidate the mechanisms of skull-brain coupling.

Although this in vivo study does not assess the tissue stresses and strains at levels that are linked to trauma, it characterizes the relative brain to skull motion in the small strain regime, which may be closely affected by the substructure at the skull-brain interface. This study provides a framework for acquiring accurate and repeatable skull and brain displacement data using MRE that can be used to characterize the skull-brain coupling system for a better understanding of mechanical brain protection mechanisms, which has great potential to facilitate risk management for future injury, In addition, studying the relative skull and brain motion could provide biofidelity targets for TBI modeling development, validation, and improvement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Health RO1 EB001981, RO1 EB010065, and an Office of Naval Research Contract N00173-15-P-0618.

References

- 1.Hyder AA, Wunderlich CA, Puvanachandra P, Gururaj G, Kobusingye OC. The impact of traumatic brain injuries: a global perspective. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22(5):341–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Report to congress on traumatic brain injury in the United States: epidemiology and rehabilitation. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Post A, Hoshizaki TB. Mechanisms of brain impact injuries and their prediction: A review. Trauma. 2012;14(4):327–349. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Animal models of traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(2):128–142. doi: 10.1038/nrn3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixit P, Liu GR. A review on recent development of finite element models for head injury simulations. Arch Computat Methods Eng. 2017;24(4):979–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleiven S, Hardy WN. Correlation of an FE model of the human head with local brain motion--Consequences for injury prediction. Stapp Car Crash J. 2002;46:123–144. doi: 10.4271/2002-22-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittek A, Omori K. Parametric study of effects of brain-skull boundary conditions and brain material properties on responses of simplified finite element brain model under angular acceleration impulse in sagittal plane. JSME INT J C MECH SY. 2003;46(4):1388–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott G, Coats B. Microstructural characterization of the pia-arachnoid complex using optical coherence tomography. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015 doi: 10.1109/tmi.2015.2396527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott GG, Margulies SS, Coats B. Utilizing multiple scale models to improve predictions of extra-axial hemorrhage in the immature piglet. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2016;15(5):1101–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10237-015-0747-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghaffari M, Zoghi M, Rostami M, Abolfathi N. Fluid structure interaction of traumatic brain injury: effects of material properties on SAS trabeculae. International Journal of Modern Engineering. 2014;14(2):54–62. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin X, Yang KH, King AI. Mechanical properties of bovine pia–arachnoid complex in shear. J Biomech. 2011;44(3):467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saboori P, Sadegh A. Material modeling of the head’s subarachnoid space. Scientia Iranica. 2011;18(6):1492–1499. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muthupillai R, Lomas DJ, Rossman PJ, Greenleaf JF, Manduca A, Ehman RL. Magnetic resonance elastography by direct visualization of propagating acoustic strain waves. Science. 1995;269(5232):1854–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.7569924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy MC, Huston J, Ehman RL. MR elastography of the brain and its application in neurological diseases. NeuroImage. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wuerfel J, Paul F, Beierbach B, Hamhaber U, Klatt D, Papazoglou S, Zipp F, Martus P, Braun J, Sack I. MR-elastography reveals degradation of tissue integrity in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2010;49(3):2520–2525. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy MC, Huston J, 3rd, Jack CR, Jr, Glaser KJ, Manduca A, Felmlee JP, Ehman RL. Decreased brain stiffness in Alzheimer’s disease determined by magnetic resonance elastography. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34(3):494–498. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sack I, Streitberger K-J, Krefting D, Paul F, Braun J. The influence of physiological aging and atrophy on brain viscoelastic properties in humans. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e23451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freimann FB, Streitberger KJ, Klatt D, Lin K, McLaughlin J, Braun J, Sprung C, Sack I. Alteration of brain viscoelasticity after shunt treatment in normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neuroradiology. 2012;54(3):189–196. doi: 10.1007/s00234-011-0871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy MC, Huston J, 3rd, Glaser KJ, Manduca A, Meyer FB, Lanzino G, Morris JM, Felmlee JP, Ehman RL. Preoperative assessment of meningioma stiffness using magnetic resonance elastography. J Neurosurg. 2013;118(3):643–648. doi: 10.3171/2012.9.JNS12519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandroff BM, Johnson CL, Motl RW. Exercise training effects on memory and hippocampal viscoelasticity in multiple sclerosis: a novel application of magnetic resonance elastography. Neuroradiology. 2017;59(1):61–67. doi: 10.1007/s00234-016-1767-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ElSheikh M, Arani A, Perry A, Boeve BF, Meyer FB, Savica R, Ehman RL, Huston J., 3rd MR elastography demonstrates unique regional brain stiffness patterns in dementias. Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209(2):403–408. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiss-Zimmermann M, Streitberger KJ, Sack I, Braun J, Arlt F, Fritzsch D, Hoffmann KT. High resolution imaging of viscoelastic properties of intracranial tumours by multi-frequency magnetic resonance elastography. Clin Radiol. 2015;25(4):371–378. doi: 10.1007/s00062-014-0311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin Z, Glaser KJ, Manduca A, Van Gompel JJ, Link MJ, Hughes JD, Romano A, Ehman RL, Huston J., 3rd Slip interface imaging predicts tumor-brain adhesion in vestibular schwannomas. Radiology. 2015;277(2):507–517. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayton EH, Genin GM, Bayly PV. Transmission, attenuation and reflection of shear waves in the human brain. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9(76):2899–2910. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Badachhape AA, Okamoto RJ, Durham RS, Efron BD, Nadell SJ, Johnson CL, Bayly PV. The relationship of three-dimensional human skull motion to brain tissue deformation in magnetic resonance elastography studies. J Biomech Eng. 2017;139(5) doi: 10.1115/1111.4036146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badachhape AA, Okamoto RJ, Johnson CL, Bayly PV. Relationships between scalp, brain, and skull motion estimated using magnetic resonance elastography. J Biomech. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2018.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H, Weaver JB, Perreard II, Doyley MM, Paulsen KD. A three-dimensional quality-guided phase unwrapping method for MR elastography. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56(13):3935. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/13/012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnhill E, Kennedy P, Johnson CL, Mada M, Roberts N. Real-time 4D phase unwrapping applied to magnetic resonance elastography. Magn Reson Med. 2015;73(6):2321–2331. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin Z, Hughes JD, Glaser KJ, Manduca A, Van Gompel J, Link MJ, Romano A, Ehman RL, Huston J. Slip interface imaging based on MR-elastography preoperatively predicts meningioma–brain adhesion. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;46(4):1007–1016. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weavers PT, Shu Y, Tao S, Huston J, Lee S-K, Graziani D, Mathieu J-B, Trzasko JD, Foo TKF, Bernstein MA. Technical Note: Compact three-tesla magnetic resonance imager with high-performance gradients passes ACR image quality and acoustic noise tests. Med Phys. 2016;43(3):1259–1264. doi: 10.1118/1.4941362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan ET, Lee SK, Weavers PT, Graziani D, Piel JE, Shu Y, Huston J, 3rd, Bernstein MA, Foo TK. High slew-rate head-only gradient for improving distortion in echo planar imaging: Preliminary experience. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;44(3):653–664. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SK, Mathieu JB, Graziani D, Piel J, Budesheim E, Fiveland E, Hardy CJ, Tan ET, Amm B, Foo TK, Bernstein MA, Huston J, 3rd, Shu Y, Schenck JF. Peripheral nerve stimulation characteristics of an asymmetric head-only gradient coil compatible with a high-channel-count receiver array. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76(6):1939–1950. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tao S, Weavers PT, Trzasko JD, Shu Y, Huston J, Lee S-K, Frigo LM, Bernstein MA. Gradient pre-emphasis to counteract first-order concomitant fields on asymmetric MRI gradient systems. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(6):2250–2262. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arunachalam SP, Rossman PJ, Arani A, Lake DS, Glaser KJ, Trzasko JD, Manduca A, McGee KP, Ehman RL, Araoz PA. Quantitative 3D magnetic resonance elastography: Comparison with dynamic mechanical analysis. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(3):1184–1192. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy MC, Huston J, 3rd, Jack CR, Jr, Glaser KJ, Senjem ML, Chen J, Manduca A, Felmlee JP, Ehman RL. Measuring the characteristic topography of brain stiffness with magnetic resonance elastography. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e81668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage. 2004;23(Supplement 1):S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Zwart JA, Ledden PJ, van Gelderen P, Bodurka J, Chu R, Duyn JH. Signal-to-noise ratio and parallel imaging performance of a 16-channel receive-only brain coil array at 3. 0 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(1):22–26. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nett EJ, Johnson KM, Frydrychowicz A, Del Rio AM, Schrauben E, Francois CJ, Wieben O. Four-dimensional phase contrast MRI with accelerated dual velocity encoding. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35(6):1462–1471. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ha H, Kim GB, Kweon J, Kim Y-H, Kim N, Yang DH, Lee SJ. Multi-VENC acquisition of four-dimensional phase-contrast MRI to improve precision of velocity field measurement. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75(5):1909–1919. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schnell S, Ansari SA, Wu C, Garcia J, Murphy IG, Rahman OA, Rahsepar AA, Aristova M, Collins JD, Carr JC, Markl M. Accelerated dual-venc 4D flow MRI for neurovascular applications. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;46(1):102–114. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowson S, Bland ML, Campolettano ET, Press JN, Rowson B, Smith JA, Sproule DW, Tyson AM, Duma SM. Biomechanical perspectives on concussion in sport. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2016;24(3):100–107. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGrath DM, Ravikumar N, Beltrachini L, Wilkinson ID, Frangi AF, Taylor ZA. Evaluation of wave delivery methodology for brain MRE: Insights from computational simulations. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78(1):341–356. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson AT, Van Houten EEW, McGarry MDJ, Paulsen KD, Holtrop JL, Sutton BP, Georgiadis JG, Johnson CL. Observation of direction-dependent mechanical properties in the human brain with multi-excitation MR elastography. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2016;59:538–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]