Abstract

Background:

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with oral TDF/FTC reduces the risk of HIV infection by >90% when taken as prescribed. Trends in prevalence of PrEP use, which account for persons who have stopped PrEP, increased through 2016, but have not been described since.

Methods:

Annual prevalence estimates of unique, TDF/FTC PrEP users (individuals with ≥1 day of PrEP prescribed in a given year) in the United States (US) were generated for 2012-2017 from a national prescription database. A validated algorithm was used to distinguish users of TDF/FTC for HIV or Hepatitis B treatment or post-exposure prophylaxis from PrEP users. We calculated annual prevalence of PrEP use overall and by age, sex and region. We used log-transformation to calculate estimated annual percent change (EAPC) in the prevalence of PrEP use.

Results:

Annual prevalence of PrEP use increased from 3.3/100,000 population in 2012 to 36.7 in 2017 – a 56% annual increase from 2012-2017 (EAPC: +56%). Annual prevalence of PrEP use increased faster among men than among women (EAPC: +68% and +5%, respectively). By age group, annual prevalence of PrEP use increased fastest among 25-34 year olds (EAPC: +61%) and slowest among ≥55 year olds (EAPC: +52%) and ≤24 year olds (EAPC: +51%). By region, in 2017 prevalence PrEP use was lowest in the South (29.8/100,000) and highest in the Northeast (62.3/100,000)

Conclusions:

Despite overall increases in the annual number of TDF/FTC PrEP users in the US from 2012-2017, the growth of absolute PrEP coverage is inconsistent across groups. Efforts to optimize PrEP access are especially needed for women and for those living in the South.

Introduction

The HIV epidemic in the United States is at a critical juncture. The National HIV/AIDS Strategy calls for an ambitious 25% reduction in new HIV diagnoses by 2020.(1) Indeed, annual new HIV diagnoses have been decreasing for several years (2), and HIV incidence is estimated to be decreasing overall in the United States.(3) Despite the lower number of new HIV infections in the US, there is still discordance in PrEP uptake. The US South, which represents 38% of the US population, bears half of the burden of new HIV infections.(2) In 2016, Black women were 15 times more likely than white women to receive an HIV diagnosis.(2) Among men who have sex with men (MSM), who account for almost two-thirds of new HIV infections in the United States, HIV incidence is estimated to be persistently high among Black MSM and increasing among Hispanic/Latino MSM.(3-5) Further, new HIV diagnoses have increased annually among MSM aged 25-34 since 2011.(2) Meeting the US national goals for reductions in new HIV infections will ultimately require making progress in reducing the risk of HIV infection in several critical subgroups of high-risk Americans; there is a need to get all available prevention resources, including treatment of people living with HIV(6), condom promotion(7), couples interventions(8), post-exposure prophylaxis(9) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), to young people, high risk men and high risk women.

Definitive clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of TDF/FTC for PrEP among MSM (10), women (11, 12), and people who inject drugs (PWID) (13). Based on the availability of this prevention tool, there is a growing consensus that highly effective HIV prevention should consist of a package of interventions that includes HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing, condom promotion, harm reduction for PWID, and antiretroviral-based PrEP. (14) The only medication currently approved for PrEP in the United States is emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF/FTC), administered as a daily oral regimen. Although the initial RCT demonstrating the efficacy of TDF/FTC estimated 92% efficacy among MSM with adequate adherence (10), subsequent open-label studies have shown considerably higher effectiveness for HIV prevention for MSM, at rates over 90%. (15, 16) Modeling studies seeking to quantify the potential population-level impacts of PrEP have been conducted in the MSM population; these suggest that increasing the prevalence of PrEP coverage among MSM to 30%-50% could result in 20-25% reductions in HIV incidence.(14, 17, 18) However, PrEP uptake has been slow among all risk groups(19), with national estimates that only 2%-9% of MSM have ever taken PrEP (20, 21); national estimates of PrEP uptake among PrEP-eligible women and PWID are not available.

The National HIV/AIDS Strategy proposed a developmental indicator of the number of commercially-insured persons (nationally weighted) aged >18 years who were prescribed TDF/FTC for PrEP for >30 days in a given calendar year. Other academic analyses have focused on the cumulative number of people who have started new PrEP prescriptions in a given year.(22, 23) We propose a metric to measure the public health impact of PrEP that takes into account both PrEP starts and PrEP discontinuations: period prevalence of PrEP use. This metric, considering both PrEP starts and discontinuations, represents the number of people who had a period of TDF/FTC for PrEP that included at least one day of PrEP in a calendar year. In the current analysis, we report trends in prevalence of PrEP use from 2012-2017, overall, by region, and among key subgroups.

Methods

Data sources

Data on TDF/FTC prescriptions for PrEP were obtained from a national database of retail and commercial pharmacy data, which was deidentified (IQVIA, formerly Source Healthcare Analytics (SHA)). IQVIA produces a commercially available dataset that aggregates anonymized pharmacy prescription data with clinical data. We have previously reported data on PrEP prescriptions from another commercial dataset, IQVIA (formerly Quintiles IMS Holdings), which represents 83% of all US commercial prescriptions.[19] The IQVIA dataset uses generally the same sources but is larger than the IMS dataset. Both datasets include prescriptions supported through the Gilead Assistance program that are filled through participating commercial pharmacies; data in these datasets include prescriptions regardless of insurance coverage or payer source. IQVIA data include data from some academic clinics, but do not include data from 340B Drug Discount Programs.

Commercial prescription data do not include data from some closed healthcare systems. To characterize the completeness of the dataset, we compared the number of PrEP starts (first time PrEP prescriptions) in the IQVIA datasets from 2013-2015. To ensure the accuracy of the algorithm to quantify TDF/FTC prescriptions exclusively for HIV prevention, the pharmacy data were systematically linked with records for medical claims, diagnosis codes, and patient demographics by using a unique, non-identifying code derived through 1-way digestion of patient information. This allows the analysis to consider PrEP starts and stops for an individual within a calendar year, only counting a person who stops and starts PrEP as one unique user during the year.

Records for prescriptions of TDF/FTC were identified in the dataset. Because TDF/FTC is frequently prescribed for indications other than HIV PrEP, this validated algorithm was used to exclude prescriptions of TDF/FTC that were made for other known indications, such as HIV treatment, HIV postexposure prophylaxis, and treatment of chronic Hepatitis B infection.(24, 25) This was accomplished by restricting the analysis to TDF/FTC monotherapy and by using medical procedure and diagnosis codes also included in the database (e.g., PrEP monotherapy after a diagnosis of chronic Hepatitis B infection was assumed to be off label therapy for chronic HBV infection, rather than PrEP; FTC/TDF prescribed along with other antiretrovirals in a person without a previous HIV diagnosis would be classified as PEP, rather than PrEP). We determined the periods when a unique person was exposed to the medication (drug exposure periods per individual, who we will refer to as “PrEP users” in this report for simplicity). Residence is assigned based on the first three digits of the zip code (ZIP3) of the patient, not the pharmacy. For each user of TDF/FTC for PrEP, the duration of the PrEP course was determined by examining subsequent renewals of the prescription. To be considered a PrEP user for prevalence calculation in a given year, that period must include at least 1 day of PrEP use (e.g., PrEP use from 10/01/2015 until 01/01/2016 would qualify as PrEP use in both 2015 and 2016).

Once the algorithm identified a TDF/FTC prescription period as PrEP use period, rather than a treatment or post-exposure indication, it also required data about medical procedures and diagnosis codes to be matched to the prescription to determine whether the TDF/FTC was prescribed for PrEP or for another indication; these data were missing for 28% of drug exposure periods. In those cases, an affirmative determination of PrEP indication for TDF/FTC could not be made, because the algorithm is one of exclusion. Therefore, the numbers of PrEP users represent a minimum estimate of PrEP users, and the actual number of users is higher. We analyzed the distribution of missing medical procedure and diagnosis codes.

Yearly population estimates were obtained from National Historical Geographic Information System (NHGIS) based on the American Community Surveys (ACS) provided by the US census Bureau for the years 2012 through 2016 nationally, by state, and by age and sex subgroups.(26) Numbers of new HIV diagnoses were obtained from AIDSVu.org for the years 2012 to 2016 (27), nationally and by geographic and demographic subgroups of interest (sex, age, state, and region). Full year 2012 data were used, although TDF/FTC was not approved for use in the US until July 2012.

Analysis

There were two main outcomes achieved from this analysis and calculated from the annual number of PrEP users. First is the period prevalence of PrEP use (“annual prevalence of PrEP use”) – i.e., the number of PrEP users in a calendar year, divided by the total population in that year, and expressed as PrEP users per 100,000 population. We calculated annual period prevalence of PrEP use for each year from 2012-2017, for the United States overall, and for key subgroups (sex, age, and geographic region). Data on race and ethnicity were not available in the commercial dataset. Our second main outcome is the PrEP-to-need ratio (PnR), defined as the ratio of number of PrEP users to the number of people newly diagnosed with HIV in the same year.(28) New HIV diagnoses serves as an epidemiological proxy for HIV incidence, and therefore, for PrEP need. PnR is therefore used to describe PrEP coverage in geographic regions/states and demographic subgroups (sex and age) relative to new HIV diagnoses in the same year. The PnR can be understood as the number of people using PrEP in a given year for every person newly diagnosed with HIV -- i.e., a PnR of 2.0 means that for every 1 person newly diagnosed with HIV in a year, 2 HIV-negative people were using PrEP. Because 2017 ACS data were not published at the time of the analysis, population denominators and new HIV diagnoses’ estimates from 2016 were used to calculate prevalence of PrEP use per 100,000 population and PnR for the year 2017, respectively.

Estimated Annual Percent Change (EAPC) in annual number of PrEP users and in the PnR were estimated using Joinpoint Regression Program (version 4.5.0.1)(29), as previously described for use in analyses of AIDS diagnoses (30). The Joinpoint software both evaluates for joinpoints (i.e. possible inflection points in the linear trend), and calculates EAPCs. We used Joinpoint to calculate crude rates of log transformed number of PrEP users per 100,000 population and tested for model fit with one maximum joinpoint. The standard error was calculated under the heteroscedasticity assumption and permutation test was used for model selection. We did not report confidence intervals for EAPCs because, given the large coverage of the population-based data (≥83% of prescriptions, and ≥85% of HIV diagnoses(31)), the assumptions underlying calculation of variances and confidence intervals would be violated.

Because we are aware that our estimates were minimum estimates of PrEP prescriptions, we conducted a sensitivity analysis for the number of national PrEP users in 2017. We did this by varying plausible ranges of values for (1) the proportion of Truvada prescriptions that are not captured in the IQVIA database, and (2) the proportion of unclassified Truvada monotherapy in the IQVIA database that are used for PrEP.

Results

We evaluated the completeness of the IQVIA dataset by comparing IQVIA estimates with weighted estimates from the IMS dataset, which aims to estimate a population total of prescriptions through weights. From 2013-2015, the IQVIA data documented 49,469 PrEP starts; the IMS unweighted data documented 33,419 starts, and IMS data with weights estimated 49,212 starts. [20, 21] The percentage of 2016 data with lack of clinical data was similar across age (28% ± 1%) and gender categories (28% for males and 31% for females). State-level percent of missing data ranged from 24% to 39% with a median of 25%. Yearly percent of lack of clinical data ranged from 21% in 2014 to 33% in 2012, with no consistent increasing or decreasing trend. Yearly percent of missing data ranged from a minimum of 21% in 2014 to a maximum 33% in 2012, with no consistent increasing or decreasing trend.

Overall, the annual number of PrEP users ranged from 8,768 in 2012 to 100,282 in 2017 (Table 1); analyzed as annual prevalence of PrEP use, prevalence increased over the period, representing a +56% EAPC (Table 2). All time trends were monotonic, e.g., the Joinpoint program confirmed that the data fits a statistically significant model with no inflection point for any group, and all models were therefore linear models. There were large differences between the magnitude of increases in annual prevalence in women (EAPC +5%) and men (EAPC +68%) (Table 2). By age, prevalence of PrEP use increased for all groups over the period. By region, prevalence of PrEP use increased for all regions over the period; the two lowest region-specific annual prevalence in 2017 were for the Midwest (EAPC +61%) and the South (EAPC +56%) (Table 2). Baseline (2012) state-specific prevalences ranged from 0.4 (Wyoming) to 14.0 (Massachusetts). The median state-specific EAPC was +56%; state-specific increases ranged from +34% (Massachusetts) to +70% (Ohio); higher EAPCs tended to occur in states with lower 2012 prevalences of PrEP use (Table 3).

Table 1.

Number and percentages of annual PrEP users, overall, and by gender, age, and region, United States 2012-17

| N(%), year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Overall | 8,768 | 12,540 | 27,596 | 59,427 | 77,120 | 100,282 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 3,964 (45) | 5,310 (42) | 7,149 (26) | 9,919 (17) | 5,143 (7) | 6,046 (6) |

| Male | 4,804 (55) | 7,230 (58) | 20,447 74 | 49,508 (83) | 71,977 (93) | 94,236 (94) |

| Age | ||||||

| 24 yr and younger | 1,449(17) | 2,083 (17) | 3,909 (14) | 7,676 (13) | 8,600 (11) | 12,659 (12) |

| 25 to 34 yr | 2,770 (32) | 4,268 (34) | 9,937 (36) | 22,232 (37) | 29,979 (39) | 40,014 (39) |

| 35 to 44 yr | 2,005 (23) | 2,893 (23) | 6,890 (25) | 14,635 (25) | 19,380 (25) | 24,061 (24) |

| 45 to 54 yr | 1,618 (18) | 2,156 (17) | 4,828 (17) | 10,633 (18) | 13,976 (18) | 16,774 (17) |

| 55 yr and older | 908 (10) | 1,133 (9) | 2,054 (7) | 4,493 (8) | 5,859 (8) | 7,893 (8) |

| Region | ||||||

| Midwest | 1,190 (14) | 1,806 (14) | 4,336 (16) | 9,933 (17) | 13,354 (17) | 17,108 (17) |

| Northeast | 2,841 (32) | 4,370 (35) | 8,741 (32) | 18,004 (30) | 22,684 (29) | 29,788 (30) |

| South | 2,956 (34) | 3,577 (29) | 8,140 (30) | 17,790 (30) | 23,091 (30) | 30,379 (30) |

| West | 1,766 (20) | 2,772 (22) | 6,355 (23) | 13,635 (23) | 17,936 (23) | 22,966 (23) |

Note: United States’ regions as defined by the US Census Bureau and adopted in CDC’s National HIV Surveillance System:

Northeast: CT, ME, MA, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT

Midwest: IL, IN, IA, KS, MI, MN, MO, NE, ND, OH, SD, WI

South: AL, AR, DE, DC, FL, GA, KY, LA, MD, MS, NC, OK, SC, TN, TX, VA, WV

West: AK, AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NV, NM, OR, UT, WA, WY.

Overall, and gender and age-specific estimates are calculated for the US 50 states, District of Columbia and Puerto Rico.

Table 2.

Annual prevalence of PrEP use per 100,000 population and Estimated Annual Percent Change (EAPC), overall and by gender, age, and region, United States 2012-17

| Prevalence of active PrEP prescriptions, year | EAPC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2012-2017 | |

| Overall | 3.3 | 4.7 | 10.3 | 21.9 | 28.2 | 36.7 | +56.4% |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 2.9 | 3.9 | 5.2 | 7.1 | 3.7 | 4.3 | +5.4% |

| Male | 3.7 | 5.6 | 15.6 | 37.3 | 53.9 | 70.6 | +68.1% |

| Age | |||||||

| 24 yr and younger | 2.7 | 3.9 | 7.4 | 14.5 | 16.4 | 24.1 | +50.6% |

| 25 to 34 yr | 6.5 | 9.9 | 22.7 | 50.2 | 66.9 | 89.3 | +60.9% |

| 35 to 44 yr | 4.9 | 7.0 | 16.7 | 35.5 | 47.2 | 58.5 | +57.4% |

| 45 to 54 yr | 3.6 | 4.9 | 11.0 | 24.4 | 32.4 | 38.8 | +56.3% |

| 55 yr and older | 1.1 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 5.0 | 6.4 | 8.6 | +51.9% |

| Region | |||||||

| Midwest | 2.1 | 3.2 | 7.7 | 17.5 | 23.5 | 30.1 | +61.1% |

| Northeast | 6.0 | 9.2 | 18.3 | 37.6 | 47.4 | 62.3 | +54.0% |

| South | 3.0 | 3.6 | 8.2 | 17.6 | 22.6 | 29.8 | +55.9% |

| West | 2.9 | 4.5 | 10.2 | 21.6 | 28.1 | 36.0 | +57.0% |

Note: Yearly prevalence of active PrEP prescriptions overall, and by age, gender, and region is calculated per 100,000 population aged 13 and above.

Overall, and gender and age-specific estimates are calculated for the US 50 states, District of Columbia and Puerto Rico.

Table 3.

Annual prevalence of PrEP use per 100,000 population by state, region, and the corresponding Estimated Annual Percent Change (EAPC), Unites States 2012-17

| Prevalence of active PrEP prescriptions*, year | EAPC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | State | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2012-2017 |

| Midwest | Illinois | 3.1 | 4.8 | 14.6 | 32.0 | 41.1 | 50.4 | +59% |

| Indiana | 1.9 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 12.3 | 17.3 | 22.4 | +62% | |

| Iowa | 2.3 | 3.1 | 5.7 | 12.9 | 17.7 | 26.0 | +62% | |

| Kansas | 2.3 | 1.9 | 5.3 | 11.2 | 13.4 | 16.4 | +49% | |

| Michigan | 1.7 | 2.7 | 5.9 | 13.0 | 16.1 | 21.6 | +58% | |

| Minnesota | 2.4 | 4.0 | 9.0 | 19.1 | 28.1 | 34.8 | +62% | |

| Missouri | 1.5 | 3.1 | 6.4 | 15.9 | 21.1 | 26.0 | +61% | |

| Nebraska | 1.8 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 9.5 | 10.1 | 15.0 | +50% | |

| North Dakota | 0.5 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 5.2 | 8.5 | 13.2 | +66% | |

| Ohio | 2.0 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 16.9 | 25.4 | 34.3 | +70% | |

| South Dakota | 0.9 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 9.2 | 9.7 | 10.7 | +48% | |

| Wisconsin | 1.7 | 2.2 | 4.7 | 11.2 | 15.1 | 18.8 | +59% | |

| Northeast | Connecticut | 5.9 | 6.7 | 15.7 | 30.0 | 31.1 | 39.7 | +43% |

| Maine | 2.5 | 3.7 | 5.7 | 12.0 | 14.6 | 19.5 | +49% | |

| Massachusetts | 14.0 | 18.0 | 31.3 | 59.1 | 58.9 | 65.1 | +34% | |

| New Hampshire | 3.4 | 5.3 | 9.5 | 16.5 | 19.6 | 21.6 | +40% | |

| New Jersey | 4.5 | 5.6 | 11.2 | 22.3 | 26.1 | 35.3 | +49% | |

| New York | 6.0 | 12.0 | 25.4 | 54.3 | 75.8 | 102.8 | +63% | |

| Pennsylvania | 3.6 | 4.7 | 8.7 | 18.9 | 25.2 | 35.0 | +57% | |

| Rhode Island | 7.6 | 11.2 | 22.5 | 43.7 | 47.9 | 59.2 | +45% | |

| Vermont | 1.5 | 1.3 | 6.5 | 11.6 | 11.3 | 15.5 | +46% | |

| South | Alabama | 1.6 | 2.7 | 4.3 | 10.8 | 15.5 | 22.0 | +66% |

| Arkansas | 1.7 | 1.6 | 4.3 | 8.9 | 11.7 | 15.8 | +57% | |

| Delaware | 6.0 | 5.8 | 11.7 | 21.0 | 30.4 | 37.9 | +49% | |

| District of Columbia | 14.9 | 20.0 | 74.6 | 176.4 | 267.7 | 318.5 | +67% | |

| Florida | 5.1 | 5.7 | 10.8 | 23.5 | 31.9 | 43.0 | +56% | |

| Georgia | 3.4 | 3.8 | 9.5 | 19.6 | 25.4 | 31.2 | +53% | |

| Kentucky | 1.3 | 1.9 | 4.4 | 9.6 | 12.0 | 16.0 | +58% | |

| Louisiana | 2.8 | 3.7 | 6.7 | 14.6 | 18.3 | 27.8 | +58% | |

| Maryland | 4.0 | 5.0 | 10.6 | 23.2 | 29.7 | 39.9 | +57% | |

| Mississippi | 1.5 | 1.6 | 4.5 | 9.2 | 11.7 | 14.7 | +54% | |

| North Carolina | 2.6 | 3.1 | 6.5 | 14.5 | 17.3 | 21.1 | +50% | |

| Oklahoma | 1.2 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 9.4 | 12.2 | 14.9 | +60% | |

| South Carolina | 1.8 | 2.0 | 4.9 | 9.4 | 11.4 | 14.1 | +49% | |

| Tennessee | 1.9 | 2.1 | 5.3 | 12.5 | 16.8 | 24.0 | +65% | |

| Texas | 2.5 | 3.3 | 8.6 | 18.1 | 21.3 | 28.5 | +54% | |

| Virginia | 3.7 | 4.1 | 8.2 | 16.2 | 19.3 | 24.7 | +47% | |

| West Virginia | 1.2 | 1.9 | 4.3 | 8.2 | 9.8 | 14.6 | +56% | |

| West | Alaska | 1.3 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 14.5 | +55% |

| Arizona | 3.2 | 3.8 | 7.0 | 13.0 | 17.4 | 27.1 | +56% | |

| California | 3.4 | 5.4 | 12.0 | 24.8 | 31.8 | 39.1 | +54% | |

| Colorado | 2.3 | 4.1 | 8.6 | 18.4 | 22.6 | 30.6 | +56% | |

| Hawaii | 2.2 | 2.2 | 5.4 | 13.0 | 17.6 | 20.1 | +56% | |

| Idaho | 0.8 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 7.3 | 10.9 | 13.4 | +62% | |

| Montana | 1.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 7.0 | 9.2 | 10.8 | +53% | |

| Nevada | 1.8 | 3.4 | 6.3 | 15.2 | 22.1 | 31.2 | +68% | |

| New Mexico | 2.2 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 11.0 | 14.2 | 21.3 | +57% | |

| Oregon | 2.5 | 3.8 | 9.4 | 19.3 | 27.2 | 37.2 | +63% | |

| Utah | 1.3 | 2.6 | 6.9 | 17.5 | 22.7 | 29.1 | +63% | |

| Washington | 3.3 | 4.7 | 14.4 | 32.5 | 44.1 | 56.5 | +63% | |

| Wyoming | 0.4 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 5.4 | 6.0 | +52% | |

| Puerto Rico | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.4 | +29% | |

Yearly prevalence of active PrEP prescriptions per 100,000 population aged 13 and above

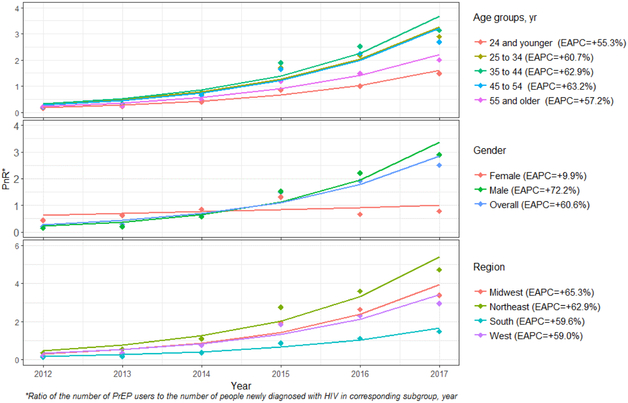

Overall, the annual PnR increased from 0.2 in 2012 to 2.5 in 2017 (i.e., in 2017, 2.5 persons were on PrEP for every 1 person newly diagnosed with HIV), representing a +61% EAPC (Table 4). Growth of the PnR in women (EAPC +10%) was more than 7 times lower than in men (EAPC +72%) (Table 4). By age, the PnR increased for all groups over the period. By region, PnR increased for all regions over the period.

Table 4.

Annual prevalence of PrEP use (Rx) and new HIV diagnoses (Dx) per 100,000 population and PrEP-to-need ratio (PnR), overall and by gender, age, and region, United States 2012-17

| Year | EAPC for PnR |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||||||||||||||

| Rx* | Dxˠ | PnR ° | Rx | Dx | PnR | Rx | Dx | PnR | Rx | Dx | PnR | Rx | Dx | PnR | Rx | Dx | PnR | ||

| Overall | 3.3 | 16.5 | 0.2 | 4.7 | 16.2 | 0.3 | 10.3 | 16.6 | 0.6 | 21.9 | 14.7 | 1.5 | 28.2 | 14.7 | 1.9 | 36.7 | 14.7 | 2.5 | +61% |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||||||

| Female | 2.9 | 6.6 | 0.4 | 3.9 | 6.2 | 0.6 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 0.9 | 7.1 | 5.4 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 5.5 | 0.7 | 4.3 | 5.5 | 0.8 | +10% |

| Male | 3.7 | 27.0 | 0.1 | 5.6 | 26.6 | 0.2 | 15.6 | 27.5 | 0.6 | 37.3 | 24.4 | 1.5 | 53.9 | 24.4 | 2.2 | 70.6 | 24.4 | 2.9 | +72% |

| Age | |||||||||||||||||||

| 24 yr and younger | 2.7 | 18.2 | 0.1 | 3.9 | 17.8 | 0.2 | 7.4 | 18.6 | 0.4 | 14.5 | 16.8 | 0.9 | 16.4 | 16.2 | 1.0 | 24.1 | 16.2 | 1.5 | +55% |

| 25 to 34 yr | 6.5 | 29.9 | 0.2 | 9.9 | 30.0 | 0.3 | 22.7 | 32.1 | 0.7 | 50.2 | 29.5 | 1.7 | 66.9 | 30.8 | 2.2 | 89.3 | 30.8 | 2.9 | +61% |

| 35 to 44 yr | 4.9 | 22.3 | 0.2 | 7.0 | 21.1 | 0.3 | 16.7 | 21.9 | 0.8 | 35.5 | 18.7 | 1.9 | 47.2 | 18.7 | 2.5 | 58.5 | 18.7 | 3.1 | +63% |

| 45 to 54 yr | 3.6 | 18.1 | 0.2 | 4.9 | 17.4 | 0.3 | 11.0 | 16.8 | 0.7 | 24.4 | 14.7 | 1.7 | 32.4 | 14.4 | 2.3 | 38.8 | 14.4 | 2.7 | +63% |

| 55 yr and older | 1.1 | 4.9 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 5.2 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 4.9 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 4.2 | 1.2 | 6.4 | 4.3 | 1.5 | 8.6 | 4.3 | 2.0 | +57% |

| Region | |||||||||||||||||||

| Midwest | 2.1 | 10.1 | 0.2 | 3.2 | 10.0 | 0.3 | 7.7 | 9.7 | 0.8 | 17.5 | 9.0 | 1.9 | 23.5 | 8.9 | 2.6 | 30.1 | 8.9 | 3.4 | +65% |

| Northeast | 6.0 | 16.9 | 0.4 | 9.2 | 16.3 | 0.6 | 18.3 | 16.6 | 1.1 | 37.6 | 13.6 | 2.8 | 47.4 | 13.2 | 3.6 | 62.3 | 13.2 | 4.7 | +63% |

| South | 3.0 | 22.0 | 0.1 | 3.6 | 21.8 | 0.2 | 8.2 | 22.2 | 0.4 | 17.6 | 20.2 | 0.9 | 22.6 | 20.1 | 1.1 | 29.8 | 20.1 | 1.5 | +60% |

| West | 2.9 | 13.0 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 12.4 | 0.4 | 10.2 | 13.4 | 0.8 | 21.6 | 11.7 | 1.8 | 28.1 | 12.2 | 2.3 | 36.0 | 12.2 | 3.0 | +59% |

Annual prevalence of PrEP use per 100,000 population

Annual incidence of new HIV diagnoses per 100,000 population

PrEP-to-need ratio: ratio of the number of PrEP users to the number of people newly diagnosed with HIV by category in corresponding year.

Notes: Overall, and gender and age-specific estimates are calculated for the US 50 states, District of Columbia and Puerto Rico.

Estimates of new HIV diagnoses from year 2016 are used to calculate PrEP-to-need ratios for 2017.

For both annual prevalence of PrEP use and PnR, Joinpoint regression resulted in a statistically significant model with no inflection point, overall or in any subgroup, suggesting that the increasing trends were monotonic over this period, using annual units of analysis (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Annual Prevalence of PrEP use, United States, 2012-2017

Figure 2.

PrEP-to-need Ratio (PnR) by Subgroup and Region, United States, 2012-2017

The sensitivity analysis yielded a range of individuals using PrEP in 2017 from 100,282 to 205,167, with a best estimate of 172,479 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis of estimated PrEP users in 2017, by reasonable estimates of missing pharmacy data and classification of TDF/FTC monotherapy as PrEP.

| Year 2017 | Percent of Truvada prescriptions not captured by SHA* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 10% | 20% | 25% | 30% | ||

| Percent of unclassified Truvada monotherapy used for PrEP† |

0% | 100,282 | 111424 | 125353 | 133709 | 143260 |

| 25% | 111116 | 123462 | 138895 | 148154 | 158737 | |

| 50% | 121950 | 135499 | 152437 | 162599 | 174214 | |

| 75% | 132783 | 147537 | 165979 | 177044 | 189690 | |

| 87% | 137983 | 153315 | 172479 | 183978 | 197119 | |

| 100% | 143617 | 159574 | 179521 | 191489 | 205167 | |

SHA estimates that 20% of all prescriptions are not included in their database.

In a previous analysis (data not shown) of Truvada monotherapy, 87% was for PrEP, 4% for management of chronic Hepatitis B infection, and 9% for HIV post-exposure prophylaxis.

Discussion

Progress towards US national prevention goals will require increased utilization of multiple prevention methods, and increasing the use of antiretroviral-based prevention strategies is an explicit goal of the National HIV Prevention Strategy.(1) Previous data have reported increases in the new starts of PrEP prescriptions (22), but the population impact of PrEP will be dependent both on the number of PrEP starts, and on the extent to which people who start PrEP stay on PrEP. In a large health maintenance organization, nearly one quarter of patients who started PrEP over a three-year period discontinued their PrEP; women were more likely to discontinue PrEP.(32) In a study of MSM, nearly one in five discontinued PrEP, and discontinuations were more common among younger men.(33) Therefore, examining only PrEP starts is likely to overestimate the current level of protection attributable to PrEP, and may differentially overstate PrEP protection for women and younger age groups. Considering annual period prevalence of PrEP use is a better representation of the trend in the extent to which populations are protected from HIV acquisition by PrEP.

According to our analyses, the prevalence of PrEP use has increased consistently from 2012-2016. Our data are consistent with data from the NHAS indicator for PrEP uptake(34), which differs from our metric because it requires a full minimum cycle of PrEP (30 days) within the calendar year. The NHAS indicator data also differ from our data source because they include only a sample of patients with commercial health insurance, whereas our data include ≥83% of all PrEP users, regardless of their insurance coverage or payer source. Data on NHAS indicator totals have been published in a monitoring report, but only as annual totals and not among subgroups.(34) Our analysis furthers the previous NHAS report by including people not covered by health insurance, by incorporating a more sensitive measure of the number of PrEP users in a year, by providing EAPC analyses, by providing trend analyses for the PnR, and by providing trend analyses for some important subgroups. Our report expands on a previous report about PrEP uptake that used a weighted sample of prescriptions for people with commercial insurance (rather than our more substantially population-based data source which includes data on prescriptions regardless of payer) and that reported trends through 2014.(35) Our 2014 estimate of the number of PrEP users (27,596) was noticeably higher than the weighted 2014 estimate of PrEP prevalence from the sample of prescriptions from commercially insured patients (9,375).

Among subgroups, although there was an encouraging increase in PrEP use over the 6-year period for men, women, and for the age groups evaluated, the magnitude of increases was not consistent across the subgroups. Nationally, 81% of new HIV infections in 2016 occurred among men.(2) Men had a higher number of PrEP users and a higher annual percent increase in prevalence of PrEP use than women. The PnR standardizes PrEP use to the number of new HIV diagnoses, and thereby allows more direct comparisons of whether PrEP coverage or trajectory of PrEP use appropriately reflects needs for prevention. Thus, if PrEP use was in proportion to the sex-specific burden of new infections, we would expect the PnR to be equal for men and women, despite more PrEP use by men. In fact, in 2017, the PnR was more than three times lower for women (0.8) than for men (2.9), indicating an inequity in PrEP use for women, relative to their need. By age group, the highest annual prevalence of PrEP use was observed in those 25-44 years of age; prevalence of PrEP use was lowest among those ≤24 and those ≥ 55 years of age. This is reassuring, because 25-44 years olds accounted for over half of new HIV diagnoses in 2016.(2) Youth have been reported to have particular barriers to PrEP uptake.(36)

Like the increases among subgroups, PrEP use increased across all US Census regions, although there were regional differences in the prevalence of PrEP use and in the PnR. The Southern US represented half of new HIV diagnoses in 2016 (2), but had the lowest PnR (1.5) in 2017 and the second lowest EAPC for growth in PrEP use (EAPC +56%). These data indicate the need for more programs to increase prevention education and access to PrEP in the South. Washington State (EAPC +63%) has developed state-specific programs to support medications and laboratory costs for PrEP (37), and New York State (EAPC +63%) has developed the PrEP Assistance Program to support clinician and STI testing costs.(38)

Our data represent a population-based data source for PrEP use, representing ≥83% of all US PrEP users; similarly, our denominators (population and HIV new diagnoses) represent actual populations (Census) or data from a routinely evaluated surveillance system that are at least 85% complete.(31) However, there are important limitations to our data. The reasons for some trends are not clear from analysis of the data; for example, women using PrEP declined in 2016. Our data do not currently allow us to ask questions that might clarify this finding, such as whether the average duration of PrEP use differs between men and women.

Although the algorithm for classifying TDF/FTC users as PrEP users has been validated both against a medical records database and against a clinic-based data source(22), prescriptions of TDF/FTC as PrEP are subject to misclassification. Further, because the prevalence of some of the other indications for TDF/FTC prescription (e.g., chronic Hepatitis B infection, post-exposure prophylaxis) might vary by age or sex, differential misclassification is possible. Because some records were missing the medical procedure and diagnosis code data required to assess PrEP indication, these data represent a minimum estimate of PrEP users. On the other hand, our designation of “PrEP users” also assumes that people who filled PrEP prescriptions used them; some people might fill a prescription but never use the medication. This would tend to systematically overstate the number of PrEP users. The PnR attempts to relate PrEP uptake to need but is imperfect in that it is not clear whether the people taking PrEP are those who need it most. For example, the PnR might indicate an increasing trend in PrEP uptake relative to need, but that increase might be occurring in white or groups with lower behaviors risks, for whom risk of HIV acquisition is lower.

There is also a substantial limitation to the demographic data associated with the prescription data: in this dataset, neither race nor ethnicity of the patient was available. This is important because, in some risk groups, the uptake of PrEP among Black and Hispanic/Latinx patients has been reported to be lower than for white patients.(39) If there are ongoing disparities in PrEP uptake among Black people with comparable or higher risks for HIV acquisition than among white people with lower risks, PrEP could have the perverse effect of increasing disparities in new HIV infections. For these reasons, it is critical to extend the current approach using data that include race and ethnicity, so that trends in increase of PrEP use can be compared by race/ethnicity. The reason that race and ethnicity are not reported in the dataset is primarily related to privacy issues; however, it is possible that future datasets could provide race and ethnicity at higher geographic levels or could provide race in lieu of some other demographic variable (e.g., age) in state-level data.

It is said that things that are not measured do not change. Our analyses seek to bring measurement and visibility to trends in PrEP use with the goal of increasing the use of PrEP as an effective biomedical prevention tool. The initial analysis of data from the first 5 years of data show that, despite impressive growth in prevalence of PrEP use, the coverage of potential PrEP protection is not distributed equitably among subgroups where the need for HIV prevention is high. Specifically, the growth of PrEP use has not occurred equally for women, for the youngest and oldest people at risk, and for those in the US South. In the case of younger men and those in the South, these shortfalls in growth of PrEP use are occurring in the very populations where the epidemic continues to be largely unabated — among young MSM, and among people living in the South.

The barriers to PrEP uptake have been conceptualized as a continuum of awareness, willingness and uptake(40), and have been related to theoretical models of behavior change.(20) Prescription data alone cannot isolate the specific reasons why some populations are experiencing lower growth in PrEP use. Further research should assess PrEP awareness, willingness/interest, access, and uptake, focusing on reasons for slower uptake in younger people, women, and people in the South. Ongoing monitoring of PrEP use should be conducted using consistent data sources and methods. To facilitate the academic examination of data on prevalence of PrEP use, we will make publicly available, concurrent with the publication of this manuscript, the data files, maps of annual PrEP use (by state, overall, and by subgroups) through www.AIDSVu.org. The public data release will also include data files for download by state and by ZIP3, and the overall data and stratifications by sex and age. As additional years of data become available, the public data maps and files will be regularly updated. PrEP is a key element of impactful, comprehensive HIV prevention programs; routine data monitoring and making data publicly available are important steps to make sure that we are measuring what matters in our national response to the HIV epidemic.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from Gilead Sciences and by the Center for AIDS Research at Emory University (P30AI050409).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020 [online national strategy document]. 2015. Available at: https://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update.pdf (last accessed November 1, 2015)

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2016; vol. 28 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/index.html. Published November 2017. Accessed December 27, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall HI, Song R, Tang T, An Q, Prejean J, Dietz P, et al. HIV Trends in the United States: Diagnoses and Estimated Incidence. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(1):e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall EW, Ricca AV, Khosropour CM, Sullivan PS. Capturing HIV incidence among MSM through at-home and self-reported facility-based testing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan PS, Rosenberg ES, Sanchez TH, Kelley CF, Luisi N, Cooper HL, et al. Explaining racial disparities in HIV incidence in black and white men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA: a prospective observational cohort study. Annals of epidemiology. 2015;25(6):445–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith D, Herbst JH, Zhang H, Rose C. Condom Efficacy by Consistency of Use among Men Who Have Sex with Men: US CROI 2013; Atlanta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health Strategies: Couples HIV Testing and Counseling [online compendium of effective interventions]. 2015. Available at: https://effectiveinterventions.cdc.gov/en/HighImpactPrevention/PublicHealthStrategies/CHTC.aspx Last accessed December 16, 2015.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recommendations and Reports: Antiretroviral Postexposure Prophylaxis After Sexual, Injection-Drug Use, or Other Nonoccupational Exposure to HIV in the United States MMWR 2005:54(RR-2);1–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(27):2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(5):399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheth AN, Rolle CP, Gandhi M. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for women. Journal of Virus Eradication. 2016;2(3):149–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2013;(9883):2083–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan PS, Carballo-Dieguez A, Coates T, Goodreau SM, McGowan I, Sanders EJ, et al. Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012; 380(9839):388–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. The Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molina J, Capitant C, Spire B, Pialoux G, Chidiac C, Charreau I, et al. , editors. On demand PrEP with oral TDF-FTC in MSM: results of the ANRS Ipergay trial. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenness SM, Goodreau SM, Rosenberg E, Beylerian EN, Hoover KW, Smith DK, et al. Impact of the Centers for Disease Control's HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Guidelines for Men Who Have Sex With Men in the United States. J Inf Dis. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brookmeyer R, Boren D, Baral SD, Bekker LG, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Beyrer C, et al. Combination HIV Prevention among MSM in South Africa: Results from Agent-based Modeling. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuller D. HIV Prevention Drug's Slow Uptake Undercuts Its Early Promise. Health affairs. 2018;37(2):178–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Lassiter JM, Whitfield TH, Starks TJ, Grov C. Uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national cohort of gay and bisexual men in the United States. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2017; 74(3):285–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan PS, Sineath C, Kahle E, Sanchez T. Awareness, willingness and use of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among a national sample of US men who have sex with men AIDS IMPACT 2015, Amsterdam, July 2015. [Abstract 52.4]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAllister S Truvada (TVD) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the United States (2013-2015). 2016. International AIDS Conference, July 2016, Paris France. Abstract TUAX0105LB. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mera-Giler R Magnuson D, Hakwins T, Bush S, Rawlings K, McCallister S Changes in Truvada for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis utilization in the USA: 2012-2016. 9th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science, Paris, abstract WEPEC0919, July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mera-Giler R, MacCannell T, Magnuson D, Bush S, Piontkowsky D. Validation of a Truvada for PrEP algorithm through Chart Review from an Electronic Medical Record. Abstract 1524. 2015. National HIV Prevention Conference December 6-9, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mera R McCallister S, Palmer B, Mayer G, Magnuson D, Rawlings K Truvada (TVD) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the United States (2013-2015). 21st International AIDS Conference 2016. Durban, South Africa [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manson Steven, Schroeder Jonathan, Van Riper David, and Ruggles Steven. IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 12.0 [Database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. 2017. http://doi.org/10.18128/D050.V12.0

- 27.Sullivan P, Sanchez T. AIDSVu.org 2016. [Available from: http://AIDSVu.org.

- 28.Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Mera Giler R, McCallister S, Yeung H, Jones J, Guest JL, Kramer M, Woodyatt C, Pembleton E, Sullivan PS. Distribution of Active PrEP Prescriptions and the PrEP-to-Need Ratio, US Q2 2017. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Illnesses 2018; Boston Massachusetts, March 4-7, 2018. Abstract ID 3546. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.5.0.1 - June 2017; Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapin-Bardales J, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS. Trends in racial/ethnic disparities of new AIDS diagnoses in the United States, 1984-2013. Annals of epidemiology. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakashima AK, Fleming PL. HIV/AIDS surveillance in the United States, 1981-2001. J AcquirImmuneDeficSyndr. 2003;32 Suppl 1:S68–S85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Hare CB, Nguyen DP, Phengrasamy T, Silverberg MJ, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in a Large Integrated Health Care System: Adherence, Renal Safety, and Discontinuation. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2016;73(5):540–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitfield THF, John SA, Rendina HJ, Grov C, Parsons JT. Why I Quit Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)? A Mixed-Method Study Exploring Reasons for PrEP Discontinuation and Potential Re-initiation Among Gay and Bisexual Men. AIDS Behav. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020 - Indicator supplement [online national strategy document]. 2016. Available at: https://www.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/nhas-indicators-supplement-dec-2016.pdf (last accessed November 1, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu H, Mendoza MC, Huang Y-lA, Hayes T, Smith DK, Hoover KW. Uptake of HIV preexposure prophylaxis among commercially insured persons—United States, 2010–2014. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2016; 64(2):144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosek S, Celum C, Wilson CM, Kapogiannis B, Delany-Moretlwe S, Bekker LG. Preventing HIV among adolescents with oral PrEP: observations and challenges in the United States and South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(7(Suppl 6)):21107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Washington State Department of Health. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Drug Assistance Program (PrEP DAP) [online program summary]. 2018. Available at: https://www.doh.wa.gov/YouandYourFamily/IllnessandDisease/HIVAIDS/HIVPrevention/PrEPDAP. Last accessed: February 11, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.New York State Health Department. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Assistance Program (PrEP-AP). [online program summary]. 2018. Available at: https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/general/resources/adap/prep.htm. Last accessed: February 11, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bush S, Magnuson D, Rawlings MK, Hawkins T, McCallister S, Mera Giler R. Racial characteristics of FTC/TDF for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users in the US. ASM Microbe/ICAAC. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelley CF, Kahle E, Siegler A, Sanchez T, Del Rio C, Sullivan PS, et al. Applying a PrEP Continuum of Care for Men who Have Sex with Men in Atlanta, GA. Clin Infect Dis. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]