Abstract

Background:

Laparoscopic and open approaches to colon resection have equivalent long-term outcomes and oncologic integrity for the treatment of colon cancer. Differences in short-term outcomes should therefore help to guide surgeons in their choice of operation. We hypothesized that minimally invasive colectomy is associated with superior short-term outcomes compared to traditional open colectomy in the setting of colon cancer.

Materials and methods:

Patients undergoing nonemergent colectomy for colon cancer in 2012 and 2013 were selected from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) targeted colectomy participant use file. Patients were divided into two cohorts based on operative approachdopen versus minimally invasive surgery (MIS). Univariate, multivariate, and propensity-adjusted multivariate analyses were performed to compare postoperative outcomes between the two groups.

Results:

A total of 11,031 patients were identified for inclusion in the study, with an overall MIS rate of 65.3% (n = 7200). On both univariate and multivariate analysis, MIS approach was associated with fewer postoperative complications and lower mortality. In the risk-adjusted multivariate analysis, MIS approach was associated with an odds ratio of 0.598 for any postoperative morbidity compared to open (P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

This retrospective study of patients undergoing colectomy for colon cancer demonstrates significantly improved outcomes associated with a MIS approach, even when controlling for baseline differences in illness severity. When feasible, minimally invasive colectomy should be considered gold standard for the surgical treatment of colon cancer.

Keywords: Colectomy, Colonic neoplasms, Laparoscopy, Minimally invasive surgical procedures

Introduction

Colon resection is the mainstay of treatment for most colon cancers and has traditionally been performed via laparotomy. Laparoscopic colectomy for colon cancer was first introduced in the early 1990s1–3 but faced early criticism given concerns regarding the oncologic integrity and risk of port-site recur-rence.4 These concerns led to several randomized controlled trials designed to evaluate long-term cancer-related outcomes associated with differing operative approaches.5–8 A Cochrane review published in 2012 by Kuhry et al. concluded that laparoscopic resection yields similar long-term oncologic outcomes to that of open colectomy.9 Similarly, several large prospective trials reported on differences in short-term outcomes between the two approaches. Most notably, the clinical outcomes of surgical therapy (COST) trial,10 colon cancer laparoscopic or open resection (COLOR) trial,11 and conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in colorectal cancer (CLASICC) trial12 all demonstrated marginal short-term benefits in those patients randomized to a laparoscopic approach for the surgical treatment of colon cancer. These trials were largely viewed as a demonstration of noninferiority of a laparoscopic approach but failed to provide compelling evidence for surgeons to alter their practice as a result.

Despite evidence from the aforementioned randomized controlled trials, laparoscopy for the treatment of colorectal cancer has not been universally adopted in the United States. Recent evidence suggests that approximately 50% of colon resections for cancer are still performed open in this country,13,14 possibly in part reflecting surgeon attitude regarding a lack of substantial benefits with a laparoscopic approach. Randomized trials have been criticized for the lack of clinically significant differences in outcomes, the patient selection, and the context in which these trials were performed wherein open patients were not managed according to newer enhanced recovery protocols. A comparison of these two approaches as used in real-world practice may help to address some of these concerns.

Therefore, we performed a comparative effectiveness study using a standardized, large, national clinical database to assess the differences in short-term patient outcomes between open and minimally invasive colon resection. Using propensity scoring to control for differences in treatment groups, we sought to further support the hypothesis that minimally invasive colectomy is associated with superior short-term outcomes compared to traditional open colectomy in the setting of colon cancer. Secondarily, we aimed to evaluate how outcomes are impacted by conversion from a minimally invasive to open approach.

Materials and methods

Sample selection

Patients undergoing nonemergent colon resection for an indication of colon cancer were selected from the 2012 and 2013 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) targeted colectomy participant use files. ACS-NSQIP provides a prospectively maintained clinical database that has been previously described. The targeted colectomy database was developed in 2011 and contains data contributed by participating academic and community hospitals throughout the country. Importantly, this database contains variables for operative approach, ileus, anastomotic leak, cancer staging information, and other colon-specific variables. Adult patients undergoing colon resection for colon cancer were eligible for inclusion in the study. Current procedural terminology (CPT) codes included 44140, 44141, 44143, 44144, 44145, 44146, 44147, 44150, 44151, 44160, 44204, 44205, 44206, 44207, 44208, and 44210. Right-sided colon resection was identified using CPT codes 44160 and 44205. Both elective and nonelective cases, which is to be distinguished from the “emergency case” variable in NSQIP, were included. In an attempt to exclude critically ill patients, exclusion criteria included emergent operation (defined by ACS-NSQIP as cases reported as emergent by the surgeon and/or anesthesiologist), preoperative ventilator-dependence, preoperative sepsis or septic shock, and ASA class 5 or ASA class not reported. Additional exclusion criteria included surgery performed by a surgical service other than general surgery; operative approach classified as endoscopic, hybrid, natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, other, or missing; and missingness of data for variables included in the statistical models. Finally, a small number of patients were excluded based on extreme propensity score (Fig. 1).

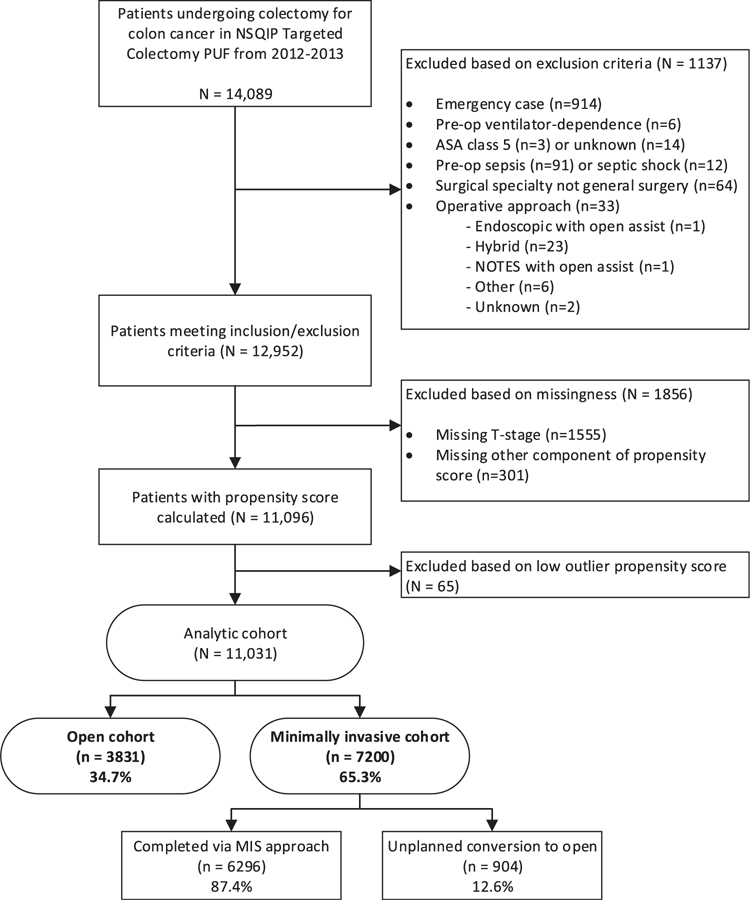

Fig. 1 –

Flow diagram showing selection of analytic cohort for the study.

Variable classification

Operative approach was classified as “open” if the procedure was planned and performed open. Minimally invasive surgical (MIS) approach was defined as any operation started as laparoscopic, hand-assisted laparoscopic, robotic, hand-assisted robotic, single-incision laparoscopic (SILS), and hand-assisted SILS. In the primary analysis, cases in which there was an unplanned conversion to open were included in the MIS cohort consistent with the intent-to-treat principle. In the secondary analysis undertaken to evaluate the effect of conversion, three separate groups were defined: open, converted, and cases completed via a MIS approach. Body mass index (BMI) classes were defined as underweight (<18.5), normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9), obese (30–39.9), and morbidly obese (40+). Age groups were divided into age <50 y, 50–64 y, 65–79 y, and 80+ y. Prolonged hospital stay was defined as length of stay >7 d.

Endpoints

The ACS-NSQIP database reports on multiple predefined 30-d outcomes, including various complications, mortality, and hospital length of stay. Additionally, the targeted colectomy database contains colorectal-specific variables for prolonged postoperative ileus and anastomotic leak. Complications were grouped into several categories to form composite endpoints. “Infectious complication” included at least one of the following complications: superficial surgical site infection (SSI), deep SSI, organ space SSI, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, sepsis, and septic shock. “Wound complication” included at least one of superficial SSI, deep SSI, and wound dehiscence. “Noninfectious complication” included anastomotic leak, wound dehiscence, reintubation, pulmonary embolism, failure to wean from the ventilator, renal insufficiency, renal failure, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, and deep venous thrombosis. As wound dehiscence most commonly occurs in the setting of wound infection but can also be related to surgical technique, it was included in both the wound composite outcome as well as the noninfectious composite outcome. “Any complication” included any of the 30-d complications included in the infectious or noninfectious categories. Ileus, 30-d mortality, mean operative time, mean hospital length of stay (LOS), and incidence of prolonged LOS were assessed as independent outcomes.

Statistical analysis

This study is a retrospective comparative effectiveness cohort study comparing outcomes following open versus minimally invasive colectomy. Univariate analysis was performed with chi-squared tests or Fisher exact tests to compare baseline demographic and preoperative characteristics between the two groups, as well as the endpoints. Multivariate analysis controlling for patient demographics, comorbidities, and extent of disease as indicated by T-stage was then performed to examine the independent effect of operative approach on the endpoints of interest. For further risk adjustment of the model, a propensity score analysis was undertaken. Multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate predicted probabilities (or propensity score) for a MIS approach using available preoperative variables with open approach as the reference. Smaller scores correlate with a lower probability of undergoing MIS approach. Once propensity scores for MIS approach were calculated, the lower fence of the box plot for the open cohort was designated as the lower cut point for inclusion in the study, which functioned to exclude patients with such extreme propensity scores that the probability of undergoing a MIS procedure was negligible. The cut-off value was propensity score <0.202, which resulted in exclusion of 52 subjects from the open group and 13 subjects from the MIS group. All remaining patients were then divided into quintiles based on propensity score. The sample was stratified by propensity score quintile, and univariate analysis was performed to compare outcomes based on operative approach within each quintile. Finally, multivariate analysis adjusting for propensity score stratum was performed for the endpoints of interest, using open approach as the reference category for operative approach.

In the secondary analysis, the converted group and fully minimally invasive group were each compared separately to the open group using chi-squared tests. A multivariate analysis was then performed adjusting for patient demographics, comorbidities, and T-stage. In the multivariate analysis, operative approach was treated as a variable with three levels (open, converted, and fully MIS), and the open approach was used as the reference category.

P value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

We identified 14,089 patients who underwent colectomy for colon cancer in 2012 and 2013 from the ACS-NSQIP targeted colectomy database. Patients were sequentially excluded due to emergent case (n = 914), preoperative ventilator-dependence (n = 6), ASA class 5 or unknown (n = 17), preoperative sepsis or septic shock (n = 103), nongeneral surgery specialty (n = 64), and operative approach not meeting inclusion criteria (n = 33). An additional 1,856 subjects were excluded due to missingness of data in key components of the propensity score (1,555 with missing T-stage and 301 with missing other variables), and 65 subjects were excluded due to extreme low propensity scores (Fig. 1). After exclusions, there were a total of 11,031 patients, which were divided into two cohorts based on initial operative approach. The majority (65.3%) of these subjects underwent a minimally invasive operation (n = 7,200), while the remaining 34.7% (n = 3,831) underwent a planned open procedure. The most common type of MIS approach utilized was laparoscopic (n = 3,393), followed by laparoscopic with hand assist (n = 2,656) (Table 1). Robotic (n = 247, 2.2%) and SILS (n = 31, 0.3%) procedures were relatively rare. Of the procedures started via a MIS approach, there was a 12.6% rate of unplanned conversion to open (n = 904).

Table 1 –

Operative approach, n = 11,031.

| Operative approach | Number of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Open | 3831 (34.7) |

| Minimally invasive surgery | 7200 (65.3) |

| Laparoscopic | 6922 (62.8) |

| Laparoscopic | 3393 (30.8) |

| Laparoscopic with hand assist | 2656 (24.1) |

| Laparoscopic converted to open | 873 (7.9) |

| Robotic | 247 (2.2) |

| Robotic | 146 (1.3) |

| Robotic with hand assist | 72 (0.7) |

| Robotic converted to open | 29 (0.3) |

| SILS | 31 (0.3) |

| SILS | 19 (0.2) |

| SILS with hand assist | 10 (0.1) |

| SILS converted to open | 2 (0.02) |

SILS = single-incision laparoscopic surgery.

Table 2 outlines specific patient and disease characteristics associated with each of the cohorts. In analyzing differences between the two groups, the MIS group had fewer comorbidities, lower grade tumors, lower incidence of obstruction at the time of surgery, younger age, lower ASA classifications, and fewer underweight and morbidly obese individuals, but more overweight and obese individuals (Table 2). The most common T-stage in both groups was T3 cancer (54.1% of open and 53.0% of MIS), and obstruction was uncommon (15.3% of open and 7.3% of MIS).

Table 2 –

Patient characteristics and comorbidities of laparoscopic and open colectomy cohorts.

| Characteristic | Open (n = 3831, %) | MIS (n = 7200, %) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 50.1 | 48.0 | 0.034 |

| Age (y) | <0.001 | ||

| <50 | 9.6 | 10.9 | |

| 50–64 | 28.2 | 31.3 | |

| 65–79 | 38.0 | 38.5 | |

| 80+ | 24.2 | 19.3 | |

| BMI | <0.001 | ||

| Normal (BMI, 18.5–24.9) | 32.1 | 30.2 | |

| Overweight (BMI, 25–29.9) | 32.2 | 34.6 | |

| Obese (BMI, 30–39.9) | 26.2 | 27.9 | |

| Morbidly obese (BMI 40.0+) | 6.1 | 5.2 | |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5) | 3.4 | 2.1 | |

| Obstruction present | 15.3 | 7.3 | <0.001 |

| Right-sided colectomy | 26.9 | 25.7 | 0.169 |

| Intestinal diversion performed | 20.6 | 9.7 | <0.001 |

| T stage | <0.001 | ||

| Tis/T0/T1 | 7.8 | 16.3 | |

| T2 | 15.1 | 19.4 | |

| T3 | 54.1 | 53.0 | |

| T4 | 23.0 | 11.3 | |

| Chemotherapy within 90 d | 11.0 | 6.7 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 0.355 | ||

| Noninsulin dependent | 13.0 | 12.6 | |

| Insulin-dependent | 6.1 | 5.5 | |

| Smoker | 15.0 | 12.3 | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea | 11.6 | 8.6 | <0.001 |

| COPD | 6.6 | 5.3 | 0.006 |

| Ascites | 0.8 | 0.2 | <0.001 |

| CHF | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.016 |

| Hypertension | 56.3 | 54.8 | 0.158 |

| Acute renal failure | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0942 |

| Dialysis | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.286 |

| Disseminated cancer | 15.3 | 6.9 | <0.001 |

| Wound infection | 1.5 | 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Steroids | 3.3 | 2.8 | 0.192 |

| Weight loss | 8.8 | 4.0 | <0.001 |

| Bleeding disorder/ anticoagulation | 4.7 | 3.3 | 0.001 |

| Preoperative transfusion | 4.2 | 2.5 | <0.001 |

| SIRS | 2.6 | 0.9 | <0.001 |

| Dependent functional status | 3.7 | 2.3 | <0.001 |

| ASA class | <0.001 | ||

| Class I | 1.6 | 2.5 | |

| Class II | 31.8 | 43.1 | |

| Class III | 58.4 | 49.5 | |

| Class IV | 8.2 | 5.0 |

The two groups were found to have significantly different outcomes on univariate analysis for all endpoints compared (Table 3). The MIS group fared better than open with a 14.9% rate of any morbidity compared to 25.3% in the open group (P < 0.001). The MIS group had approximately half as many patients suffering an infectious complication than the open group (11.8% versus 20.5%, P < 0.001). Similar reductions in morbidity were observed in the MIS group for noninfectious complications (7.0% versus 12.2%, P < 0.001), wound complications (5.8% versus 10.5%, P < 0.001), prolonged LOS (22.0% versus 48.4%, P < 0.001), and postoperative ileus (10.9% versus 20.7%, P < 0.001). Thirty-day mortality was over twice as high in the open group compared to MIS (2.9% versus 1.3%, P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis adjusting for preoperative and operative characteristics continued to demonstrate statistically significant reductions in all endpoints associated with a MIS approach (Table 4). The odds ratio of any postoperative morbidity was 0.607 in the MIS group compared to open (95% CI 0.547–0.672, P < 0.001).

Table 3 –

Univariate analysis comparing rates of complications between open and minimally invasive approaches, n = 11,031.

| Complication | Open (n = 3831) | MIS (n = 7200) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any complication | 25.3% (969) | 14.9% (1073) | <0.001 |

| Infectious complication | 20.5% (784) | 11.8% (850) | <0.001 |

| Superficial SSI | 7.6% (293) | 4.7% (337) | <0.001 |

| Deep SSI | 2.0% (77) | 0.6% (46) | <0.001 |

| Organ space SSI | 5.2% (198) | 3.3% (236) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 3.1% (118) | 1.5% (108) | <0.001 |

| Urinary tract infection | 4.0% (154) | 2.3% (165) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 4.2% (161) | 2.3% (166) | <0.001 |

| Septic shock | 2.1% (81) | 1.1% (78) | <0.001 |

| Non-infectious complication | 12.2% (469) | 7.0% (505) | <0.001 |

| Anastomotic leak | 5.0% (192) | 3.0% (219) | <0.001 |

| Dehiscence | 1.6% (60) | 0.7% (50) | <0.001 |

| Reintubation | 2.8% (107) | 1.5% (111) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1.1% (44) | 0.7% (47) | 0.006 |

| Failure to wean | 2.3% (88) | 1.1% (82) | <0.001 |

| Renal insufficiency | 0.7% (28) | 0.6% (40) | 0.263 |

| Renal failure | 0.8% (31) | 0.4% (32) | 0.016 |

| Cardiac arrest | 0.7% (25) | 0.5% (36) | 0.304 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.0% (40) | 0.7% (48) | 0.034 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2.0% (75) | 1.1% (76) | <0.001 |

| Wound complication | 10.5% (404) | 5.8% (417) | <0.001 |

| Superficial SSI | 7.6% (293) | 4.7% (337) | <0.001 |

| Deep SSI | 2.0% (77) | 0.6% (46) | <0.001 |

| Dehiscence | 1.6% (60) | 0.7% (50) | <0.001 |

| Prolonged LOS, >7 d* | 48.4% (1853/3827) | 22.0% (1583/7196) | <0.001 |

| Mean LOS, days (standard deviation)* | 9.5 (6.3) | 6.3 (4.9) | <0.001 |

| Ileus (n = 11,000) | 20.7% (792/3818) | 10.9% (780/7182) | <0.001 |

| 30-d mortality | 2.9% (110) | 1.3% (90) | <0.001 |

SSI = surgical site infection; LOS = length of stay.

Bold indicates composite endpoints.

8 subjects had missing LOS data and were excluded from this analysis.

Table 4 –

Results of unadjusted and propensity-adjusted multivariate analyses controlling for preoperative and operative characteristics.

| Complication | Unadjusted multivariate analysis |

Propensity-adjusted multivariate analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio* (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio* (95% CI) | P value | |

| Any complication | 0.607 (0.547–0.672) | <0.001 | 0.598 (0.540–0.663) | <0.001 |

| Infectious complication | 0.596 (0.533–0.666) | <0.001 | 0.591 (0.528–0.660) | <0.001 |

| Noninfectious complication | 0.648 (0.563–0.745) | <0.001 | 0.639 (0.556–0.734) | <0.001 |

| Wound complication | 0.573 (0.493–0.666) | <0.001 | 0.570 (0.491–0.663) | <0.001 |

| Prolonged LOS, >7 d | 0.376 (0.343–0.412) | <0.001 | 0.377 (0.344–0.413) | <0.001 |

| Ileus | 0.535 (0.477–0.599) | <0.001 | 0.533 (0.476–0.597) | <0.001 |

| 30-day mortality | 0.664 (0.492–0.898) | 0.008 | 0.668 (0.496–0.900) | 0.008 |

Odds ratio < 1 indicates lower complication rate with minimally invasive approach (open approach is the reference category).

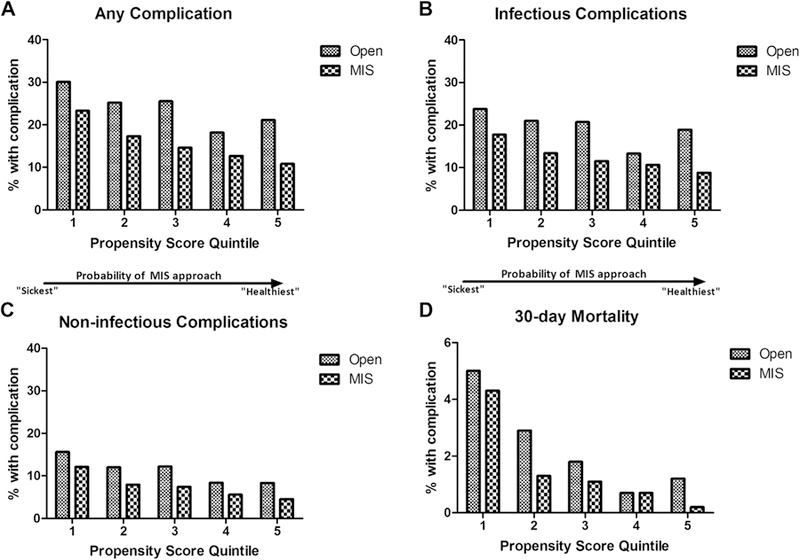

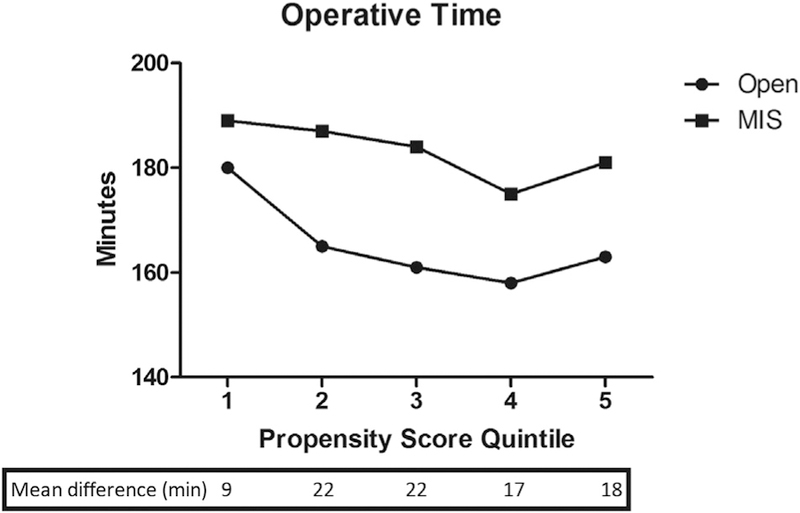

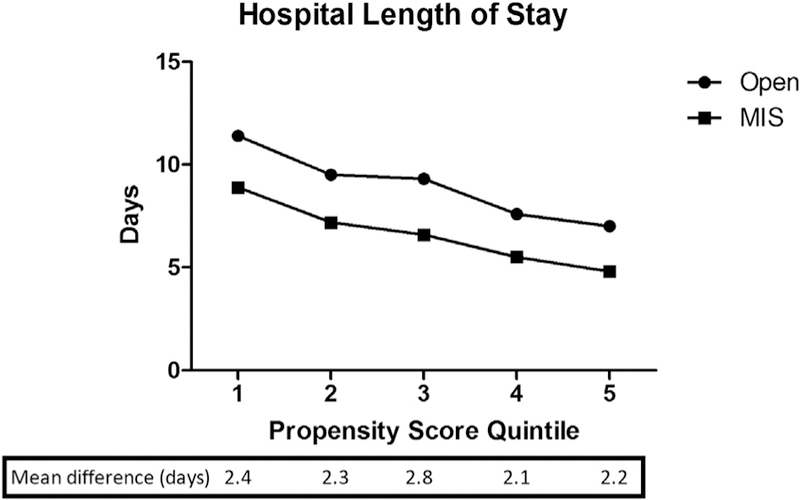

Propensity score calculation for predicted probability of undergoing minimally invasive colon resection identified multiple preoperative variables that were significant independent predictors of operative approach. Factors associated with decreased odds of undergoing a minimally invasive approach included presence of obstruction, higher T-stage, older age, morbid obesity, ASA class III or IV, as well as the presence of several comorbidities (Table 5). The single largest predictor of undergoing an open approach was T4 tumor stage, which yielded an odds ratio for MIS approach of 0.319 relative to the reference of Tis/T0/T1 (95% CI 0.270–0.377, P < 0.001). After dividing all subjects into quintiles based on probability of undergoing MIS approach, the MIS and open groups were more balanced with regards to patient and disease-related characteristics within each quintile. The univariate comparison of 30-d outcomes between the two operative approaches, as stratified by propensity score quintile, is represented in Figure 2. Moving from the lowest-probability-for-MIS group to the highest probability group, outcomes universally improved. However, within each quintile group, MIS continued to be associated with lower morbidity and mortality compared to an open approach (Fig. 2). Mean operative time was marginally longer with a MIS approach by 9–22 min (Fig. 3). Conversely, hospital length of stay was shorter in the MIS groups by 2–3 d (Fig. 4). Finally, after propensity score adjustment of the multivariate model, minimally invasive colectomy was still found to be associated with fewer postoperative complications, lower incidence of ileus, and lower 30-d mortality (Table 4).

Table 5 –

Predictors of minimally invasive approach.

| Predictor | Odds ratio* | 95% CI for OR | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | Ref | ||

| Male | 1.067 | 0.982–1.160 | 0.125 |

| Age (y) | |||

| <50 | Ref | ||

| 50–64 | 0.885 | 0.760–1.030 | 0.115 |

| 65–79 | 0.786 | 0.673–0.918 | 0.002 |

| 80+ | 0.689 | 0.579–0.820 | <0.001 |

| BMI | |||

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | Ref | ||

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 1.003 | 0.904–1.113 | 0.955 |

| Obese (30–39.9) | 0.979 | 0.875–1.097 | 0.719 |

| Morbidly Obese (40+) | 0.803 | 0.662–0.974 | 0.026 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 0.800 | 0.619–1.034 | 0.088 |

| T-stage | |||

| Tis/T0/T1 | Ref | ||

| T2 | 0.676 | 0.575–0.795 | <0.001 |

| T3 | 0.578 | 0.502–0.666 | <0.001 |

| T4 | 0.319 | 0.270–0.377 | <0.001 |

| Presence of obstruction | 0.606 | 0.530–0.692 | <0.001 |

| SIRS | 0.550 | 0.401–0.752 | <0.001 |

| ASA class | |||

| Class I | Ref | ||

| Class II | 0.942 | 0.690–1.288 | 0.710 |

| Class III | 0.681 | 0.497–0.933 | 0.017 |

| Class IV | 0.521 | 0.365–0.743 | <0.001 |

| Functional status | |||

| Independent | Ref | ||

| Dependent | 0.851 | 0.668–1.085 | 0.193 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | |||

| Noninsulin dependent | 1.008 | 0.887–1.145 | 0.906 |

| Insulin-dependent | 1.046 | 0.872–1.256 | 0.626 |

| Smoking | 0.865 | 0.765–0.978 | 0.020 |

| Dyspnea | 0.824 | 0.715–0.949 | 0.007 |

| COPD | 1.083 | 0.902–1.301 | 0.394 |

| Ascites | 0.433 | 0.255–0.735 | 0.002 |

| CHF | 0.982 | 0.681–1.415 | 0.922 |

| Hypertension | 1.064 | 0.969–1.168 | 0.192 |

| Renal failure | 0.502 | 0.167–1.502 | 0.218 |

| Dialysis | 1.079 | 0.619–1.882 | 0.788 |

| Disseminated cancer | 0.607 | 0.530–0.696 | <0.001 |

| Wound infection | 0.517 | 0.342–0.782 | 0.002 |

| Bleeding disorder | 0.876 | 0.711–1.079 | 0.212 |

| Weight loss >10% | 0.614 | 0.518–0.728 | <0.001 |

| Steroids | 1.091 | 0.859–1.386 | 0.473 |

| Chemotherapy within 90 d | 0.540 | 0.466–0.626 | <0.001 |

| Preoperative transfusion | 0.777 | 0.620–0.973 | 0.028 |

Bold indicates P < 0.05.

Odds ratio < 1 indicates lower probability of undergoing minimally invasive approach.

Fig. 2 –

Percentage of each propensity score quintile group with (A) any 30-d postoperative complication, (B) infectious complications, (C) noninfectious complications, and (D) 30-d mortality.

Fig. 3 –

Average operative time within each propensity score quintile based on operative approach.

Fig. 4 –

Mean total hospital length of stay (LOS) by propensity score quintile based on operative approach. All LOS recorded >30 were treated as 30 d. Those cases with missing LOS data were excluded.

When patients undergoing unplanned conversion from MIS to open approach were distinguished from the MIS group, the outcomes among patients undergoing conversion were comparable to those of the planned open group (Table 6). On univariate analysis, the only complication that occurred more frequently in the converted patients compared to open was superficial SSI (9.8% versus 7.6%, P = 0.029). Although conversion was also associated with a longer mean operative time than planned open surgery (208 min versus 166 min, student t-test P < 0.001), converted patients had a lower incidence of prolonged LOS (40.3% versus 48.4%, P < 0.001). The multivariate analysis accounting for unplanned conversion demonstrated a slightly higher risk of overall complications (odds ratio = 1.198, 95% CI = 1.013–1.417) and infectious complications (OR = 1.205, 95% CI = 1.008–1.440) compared to planned open surgery, but no significantly increased risk of noninfectious complications, anastomotic leak, ileus, or 30-d mortality (Table 6).

Table 6 –

Comparison of outcomes between open and converted groups, and open versus MIS groups.

| Complication | Univariate analysis, % |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open (n = 3831) | Converted (n = 904) | MIS (n = 6296) | P-value for χ2 test* | Odds ratio† | 95% Confidence interval for OR | P- value for OR | |

| Any complication | 25.3 | 27.9 | 13.0 | 0.110 | 1.198 | 1.013–1.417 | 0.035 |

| <0.001 | 0.521 | 0.466–0.581 | <0.001 | ||||

| Infectious complication | 20.5 | 23.0 | 10.2 | 0.091 | 1.205 | 1.008–1.440 | 0.041 |

| <0.001 | 0.504 | 0.447–0.568 | <0.001 | ||||

| Superficial SSI | 7.6 | 9.8 | 3.9 | 0.029 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Deep SSI | 2.0 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.802 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Organ space SSI | 5.2 | 5.9 | 2.9 | 0.402 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Urinary tract infection | 4.0 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 0.801 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Pneumonia | 3.1 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 0.500 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Sepsis | 4.2 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 0.999 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Septic shock | 2.1 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 0.321 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Non-infectious complication | 12.2 | 12.7 | 6.2 | 0.694 | 1.105 | 0.883–1.383 | 0.384 |

| <0.001 | 0.568 | 0.489–0.660 | <0.001 | ||||

| Anastomotic leak | 5.0 | 5.0 | 2.8 | 0.963 | 1.006 | 0.716–1.415 | 0.972 |

| <0.001 | 0.554 | 0.445–0.691 | <0.001 | ||||

| Dehiscence | 1.6 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 0.258 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Reintubation | 2.8 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.550 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.473 | |||

| 0.001 | |||||||

| Failure to wean | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 0.963 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Renal insufficiency | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.631 | |||

| 0.157 | |||||||

| Renal failure | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.140 | |||

| 0.001 | |||||||

| Cardiac arrest | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.450 | |||

| 0.160 | |||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.311 | |||

| 0.005 | |||||||

| Deep venous thrombosis | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.711 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Ileus | 20.7 | 20.3 | 9.5 | 0.702 | 1.037 | 0.862–1.247 | 0.484 |

| <0.001 | 0.463 | 0.410–0.523 | <0.001 | ||||

| Mortality, 30-day | 2.9 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.475 | 1.478 | 0.953–2.292 | 0.081 |

| <0.001 | 0.532 | 0.379–0.746 | <0.001 | ||||

| Prolonged hospital stay, >7 days | 48.4 | 40.3 | 19.4 | <0.001 | 0.795 | 0.678–0.931 | 0.004 |

| <0.001 | 0.325 | 0.294–0.358 | <0.001 | ||||

| Mean LOS, days (SD) | 9.5 (6.3) | 8.6 (5.8) | 6.0 (4.7) | 0.005 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

| Mean operative time, minutes (SD) | 166 (103) | 208 (107) | 176 (90) | <0.001 | |||

| <0.001 | |||||||

Bold indicates P < 0.05.

Chi-squared tests were performed pairwise between open and converted groups and open and MIS groups.

Multiple logistic regression model using open as the reference category for all reported odds ratios; missing data: anastomotic leak (n = 26, 0.2%), ileus (n = 31, 0.3%), LOS (n = 8, 0.1%), operative time (n = 1, 0.01%).

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study using a large, national clinical database, we have demonstrated that a minimally invasive approach to colectomy for the treatment of colon cancer is associated with reduced postoperative morbidity compared to an open approach. Importantly, this association remains after controlling for preoperative differences in severity of disease and comorbidity between the two groups using propensity score adjustment. Furthermore, the benefits of a MIS approach demonstrated in this study are quite dramatic and pervasive across nearly every domain evaluated, with odds ratios as low as 0.5 for many complications even in the adjusted model.

Our finding of improved outcomes with a MIS approach is consistent with several other recent large database studies that have addressed the same question. Bilimoria et al. performed a similar analysis using ACS-NSQIP data from 2005–2006 and reported adverse short-term event rates of 14.6% in patients undergoing laparoscopic-assisted colectomy compared with 21.7% in those undergoing open surgery.15 Specifically, the open group experienced higher rates of surgical site infection, pneumonia, wound dehiscence, and prolonged hospital length of stay (defined as >6 d). In a non-erisk-adjusted analysis using the National Inpatient Sample database from 2003 to 2004, Steele et al. reported significantly lower rates of in-hospital complications (18% versus 22%) and in-hospital mortality (0.6% versus 1.4%) with a laparoscopic approach compared to open.16 Compared to these previous studies, our study had the advantage of being able to control for additional clinical variables related to disease severity such as T-stage and presence of obstruction. However, even when including these additional measures of disease severity and incorporating them into the propensity score model, minimally invasive surgery was associated with improved short-term outcomes of similar magnitude as previous reports.

The findings presented in this study are also consistent with previous reports from our own group. In evaluating differences in outcomes between laparoscopic and open surgery in the elective surgical management of diverticular disease, Russ et al. reported a lower incidence of overall morbidity and shorter hospital length of stay in patients undergoing a laparoscopic approach using national NSQIP data from 2005–2008.17 Likewise, Kennedy et al. performed a risk-stratified analysis of approximately 7,600 patients included in the NSQIP database that had undergone nonemergent abdominal colectomy from 2005–2006.18 This study reported a reduction of 37%–45% in overall complications when a laparoscopic approach was used compared to open.

The rate of minimally invasive colectomy in our study (65.3%) is higher than other reports in the literature.13,14,19,20 Although this is a reassuring finding given the mounting evidence to support the benefits of laparoscopic colon resection, it is likely related to several factors. First, studies published over the last 10 y suggest that rates of laparoscopic approach to colon resection have been increasing over time, and our cohort represents the most recent data on this topic. Additionally, we have used a database specifically designed for quality improvement, and participating institutions likely represent a biased sample of institutions that have a particular interest in improving patient outcomes and quality of care, perhaps yielding increasing and earlier adoption of laparoscopy. It is possible that this phenomenon also contributed in part to the substantial reduction in morbidity observed in this study. Although the database is de-identified with regard to institution and provider, hospitals participating in NSQIP are reportedly larger, higher volume, and more likely to be teaching hospitals in comparison to nonparticipants21 and may therefore have more surgeons with specialized training in advanced laparoscopy or robotic surgery. However, after controlling for baseline differences and risk adjustment between participants and nonparticipants, Osborne et al. found no significant differences in outcomes associated with NSQIP participation,21 suggesting that the reduction in postoperative complications associated with MIS techniques observed in our study are likely more a reflection of true differences between the two operative approaches, rather than an unmeasured effect of NSQIP participation.

Although we have demonstrated an impressive difference in short-term outcomes between minimally invasive and open colectomy, it is worth noting several limitations of this study. Inherent to any retrospective observational study, there is potential for treatment assignment bias in the absence of randomization. Consequently, it is impossible to ascertain causation of the observed outcomes. In this study, the two groups differed significantly in baseline characteristics, comorbidities, severity of illness, and disease stage. However, we have made every attempt to control for these differences in our analysis. The NSQIP database reports on a large number of clinically important comorbidities, measures of disease severity, and patient demographics, all of which were used in a multivariable model to control for such differences. Additionally, propensity scores for likelihood of undergoing a MIS approach were used to risk-stratify subjects and to systematically exclude patients who had low outlier propensity for a MIS approach. Although it is impossible to control for unmeasured differences or account for surgeon discretion at the time of the encounter, the differences in outcomes observed in this study nonetheless likely represent a real effect of surgical approach on short-term patient outcomes and are consistent with other published data.

As evidence continues to accumulate in its favor, laparoscopic colon resection should now be considered standard of care in the surgical treatment of colonic malignancies. Although it will always remain that a select population of patients are poor candidates for laparoscopy, and more accurate identification of these patients may be the target of future research, most patients would likely benefit from a minimally invasive approach in a clinically significant way. It is imperative that future studies begin to address the gap in implementation of laparoscopy. As previously noted, only approximately half of all colon resections for cancer are currently being performed laparoscopically in the United States, unnecessarily exposing patients to the potential risks and associated morbidity of an open operation. It is unclear if this is related to concerns about outcomes, surgeon comfort level or training, or some other undefined reason. Several studies have sought to characterize institution-level factors associated with high adoption rates of laparoscopy,13,14,22 and it is apparent that there is regional and institutional variation in the adoption of this approach independent of patient-related variables. Future efforts will need to attempt to better understand why certain patients are not being offered laparoscopic colectomy and how to overcome barriers to more widespread adoption.

Conclusion

Minimally invasive colon resection is clearly associated with significantly better short-term postoperative outcomes, including fewer postoperative complications, lower mortality, and shorter hospital length of stay, in patients undergoing colectomy for colon cancer. This approach should be considered standard of care in patients for whom a minimally invasive surgical approach is feasible.

Acknowledgment

The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. Statistics support was provided by the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, which is funded by the aforementioned CTSA. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Salary support for CM Papageorge is provided by the T32 Surgical Oncology Training Grant (NIH NCI T32 CA090217–11). The authors would additionally like to acknowledge Glen Leverson, PhD, for providing statistics support for this project.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Christina Papageorge, Qianqian Zhao, Bruce Harms, Charles Heise, Evie Carchman, and Gregory Kennedy report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article. Eugene Foley is a consultant for Armada Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phillips EH, Franklin M, Carroll BJ, Fallas MJ, Ramos R, Rosenthal D. Laparoscopic colectomy. Ann Surg 1992;216:703–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monson JR, Darzi A, Carey PD, Guillou PJ. Prospective evaluation of laparoscopic-assisted colectomy in an unselected group of patients. Lancet 1992;340:831–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs M, Verdeja JC, Goldstein HS. Minimally invasive colon resection (laparoscopic colectomy). Surg Laparosc Endosc 1991;1:144–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berends FJ, Kazemier G, Bonjer HJ, Lange JF. Subcutaneous metastases after laparoscopic colectomy. Lancet 1994; 344:58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H, et al. Randomized trial of laparoscopic-assisted resection of colorectal carcinoma: 3-year results of the Uk MRC CLASICC Trial Group. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3061–3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jayne DG, Thorpe HC, Copeland J, Quirke P, Guillou PJ. Five-year follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2010;97:1638–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleshman J, Sargent DJ, Green E, et al. Laparoscopic colectomy for cancer is not inferior to open surgery based on 5-year data from the COST Study Group trial. Ann Surg 2007;246:655–662. discussion 662–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buunen M, Veldkamp R, Hop WC, et al. Survival after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: long-term outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhry E, Schwenk W, Gaupset R, Romild U, Bonjer J. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: a cochrane systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Cancer Treat Rev 2008;34:498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350: 2050–2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veldkamp R, Kuhry E, Hop WC, et al. Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, et al. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365:1718–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simorov A, Shaligram A, Shostrom V, Boilesen E, Thompson J, Oleynikov D. Laparoscopic colon resection trends in utilization and rate of conversion to open procedure: a national database review of academic medical centers. Ann Surg 2012;256:462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox J, Gross CP, Longo W, Reddy V. Laparoscopic colectomy for the treatment of cancer has been widely adopted in the United States. Dis Colon Rectum 2012;55:501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Merkow RP, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted vs. open colectomy for cancer: comparison of short-term outcomes from 121 hospitals. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:2001–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steele SR, Brown TA, Rush RM, Martin MJ. Laparoscopic vs open colectomy for colon cancer: results from a large nationwide population-based analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:583–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russ AJ, Obma KL, Rajamanickam V, et al. Laparoscopy improves short-term outcomes after surgery for diverticular disease. Gastroenterology 2010;138:2267–2274, 2274.e2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy GD, Heise C, Rajamanickam V, Harms B, Foley EF. Laparoscopy decreases postoperative complication rates after abdominal colectomy: results from the national surgical quality improvement program. Ann Surg 2009;249:596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rea JD, Cone MM, Diggs BS, Deveney KE, Lu KC, Herzig DO. Utilization of laparoscopic colectomy in the United States before and after the clinical outcomes of surgical therapy study group trial. Ann Surg 2011;254:281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carmichael JC, Masoomi H, Mills S, Stamos MJ, Nguyen NT. Utilization of laparoscopy in colorectal surgery for cancer at academic medical centers: does site of surgery affect rate of laparoscopy? Am Surg 2011;77:1300–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osborne NH, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Dimick JB. Association of hospital participation in a quality reporting program with surgical outcomes and expenditures for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA 2015;313:496–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel SS, Patel MS, Mahanti S, et al. Laparoscopic versus open colon resections in California: a cross-sectional analysis. Am Surg 2012;78:1063–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]