Abstract

Objective

To investigate safety and explore efficacy of efgartigimod (ARGX-113), an anti-neonatal Fc receptor immunoglobulin G1 Fc fragment, in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG) with a history of anti-acetylcholine receptor (AChR) autoantibodies, who were on stable standard-of-care myasthenia gravis (MG) treatment.

Methods

A phase 2, exploratory, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 15-center study is described. Eligible patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive 4 doses over a 3-week period of either 10 mg/kg IV efgartigimod or matched placebo combined with their standard-of-care therapy. Primary endpoints were safety and tolerability. Secondary endpoints included efficacy (change from baseline to week 11 of Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living, Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis, and Myasthenia Gravis Composite disease severity scores, and of the revised 15-item Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life scale), pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and immunogenicity.

Results

Of the 35 screened patients, 24 were enrolled and randomized: 12 received efgartigimod and 12 placebo. Efgartigimod was well-tolerated in all patients, with no serious or severe adverse events reported, no relevant changes in vital signs or ECG findings observed, and no difference in adverse events between efgartigimod and placebo treatment. All patients treated with efgartigimod showed a rapid decrease in total immunoglobulin G (IgG) and anti-AChR autoantibody levels, and assessment using all 4 efficacy scales consistently demonstrated that 75% showed a rapid and long-lasting disease improvement.

Conclusions

Efgartigimod was safe and well-tolerated. The correlation between reduction of levels of pathogenic IgG autoantibodies and disease improvement suggests that reducing pathogenic autoantibodies with efgartigimod may offer an innovative approach to treat MG.

Classification of evidence

This study provides Class I evidence that efgartigimod is safe and well-tolerated in patients with gMG.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a rare autoimmune disorder driven by pathogenic immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibodies against the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR) or other components of the neuromuscular junction, thereby functionally interfering with normal synaptic transmission.1–4

The neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) plays a central role in IgG homeostasis by rescuing IgGs from lysosomal degradation, resulting in long half-lives of IgGs compared to other Ig isotypes.5 Efgartigimod (ARGX-113) is an investigational drug for IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases, consisting of an IgG1 Fc portion that has been mutated at 5 residues, ABDEG (antibodies that enhance IgG degradation) mutations, to increase its FcRn affinity at both physiologic and acidic pH.6 In a first-in-human study, a single administration (up to 50 mg/kg) reduced total IgGs about 50%, while repeated dosing (at saturating dose of 10 mg/kg) further lowered IgG levels by approximately 75%.7 Efgartigimod administration was associated with few, mostly mild and self-limiting adverse events; no dose-limiting toxicity was observed.

We hypothesized that if the reduction of AChR autoantibodies, which are of the IgG1 and IgG3 subclass,3 would follow the decrease as observed in healthy volunteers during the phase 1 study, patients with MG treated with efgartigimod might experience a therapeutic benefit. One important question was if similar pharmacodynamic effects could be achieved, since the IgG levels could already be lower as a result of treatment with corticosteroids or immunosuppressants.

Another important aspect is safety as these patients are immunocompromised to varying degrees due to previous and concomitant immunosuppressive treatments and additional reduction of IgGs might give a different safety profile as seen with healthy individuals. To test this hypothesis, we initiated an exploratory phase 2 trial of efgartigimod in generalized MG (gMG).

Methods

Study design

This exploratory phase 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of efgartigimod recruited 24 patients with MG with generalized muscle weakness at 15 sites in 8 countries (Belgium, Canada, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and United States). Patients were randomized to receive 4 weekly doses of either 10 mg/kg IV efgartigimod or matched placebo in addition to their individual standard-of-care treatment prior to study entry.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

This study (study identifiers: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02965573, EudraCT 2016-002938-73) was performed in compliance with the protocol (appendix, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.4hk2039), International Council for Harmonisation, Good Clinical Practice, Declaration of Helsinki, and other applicable regulatory requirements. Independent ethics committees or institutional review boards provided written approval for the study protocol and all amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before entering the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Male or female patients aged 18 years or older were eligible for the study if they had confirmed gMG, history of a positive serologic test for anti-AChR antibodies, impaired activities of daily living defined as a Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living (MG-ADL) score of 5 or higher at screening and baseline with more than 50% of the score attributable to nonocular items, and Class II–IVa disease according to the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) classification system.

Patients had to be on a stable dose of their standard-of-care MG treatment prior to randomization.

Patients excluded from the study were those with a history of malignancy, including malignant thymoma, those with a thymectomy performed <3 months prior to screening, those who used a monoclonal antibody for immunomodulation within 6 months prior to first dosing (or in case of prior rituximab treatment with CD19 counts below the normal range), those having taken any biological therapy or investigational drug within 3 months or 5 half-lives of the drug before screening, those who received IV or intramuscular immunoglobulin or plasmapheresis/plasma exchange within 4 weeks before screening, or those with MGFA Class I (restricted ocular disease), Class IVb (severe bulbar disease), or Class V (myasthenic crisis).

A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is reported in the protocol in the appendix (doi.or0g/1.5061/dryad.4hk2039).

Recruitment of potential patients was performed from the investigators' practice or through physicians' referral.

Randomization and masking

Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive efgartigimod or matched placebo in combination with their standard-of-care therapy. The matching placebo used the same formulation as efgartigimod but without the active ingredient, and was identical in physical appearance and supplied in identical containers to preserve masking.

Upon enrollment, a screening number was allocated via the Interactive Web Response System (IWRS) for the patient. At visit 1, the patient was randomized by the site via IWRS, which generated a patient randomization number. Investigators and staff, patients, and study team members from the sponsor or the sponsor's designated CRO (IQVIA) remained masked to the treatment assignment until after final database lock.

Procedures

The study included a screening period of up to 15 days to evaluate the patients' eligibility for study participation, a treatment period of 3 weeks from visit 1 to visit 7, and a follow-up period of 8 weeks starting after completion of visit 7 to visit 16.

During the 3-week treatment period, eligible patients received a dose of 10 mg/kg of body weight efgartigimod or matching placebo administered as an IV infusion over a period of 2 hours on days 1 (visit 1), 8 ± 1 (visit 3), 15 ± 1 (visit 5), and 22 ± 1 (visit 7); the total dose per infusion was capped at 1,200 mg for patients with body weight ≥120 kg.

Standard of care for a patient was defined for this study as the stable dose and administration of treatment for MG prior to enrollment, which was maintained throughout the study. Permitted standard of care included nonsteroidal immunosuppressant drugs, corticosteroids, and cholinesterase inhibitors. Under protocol-defined conditions, patients were allowed to receive rescue therapy (e.g., IV immunoglobulin [IVIg] or plasma exchange) in case of deteriorating MG as judged by the investigator. Patients receiving rescue therapy were discontinued from the investigational medicinal product, but were followed until the end of the study for safety. The study was monitored by an Independent Data Monitoring Committee.

Adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), vital signs, ECGs, and clinical laboratory assessments at specific time points were evaluated and summarized descriptively.

Number and percentage of AEs was described for each treatment by preferred term and system organ class of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Authorities (MedDRA) version 19.1. Individual listings of all SAEs and discontinuations were summarized using MedDRA. AEs starting or worsening on or after the first dosing were considered treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs). For each AE, severity (mild, moderate, or severe) and causality (unrelated, unlikely, possibly, probably, or certainly related) were assessed by the investigator. TEAEs were considered “related” to efgartigimod when classified as “possibly,” “probably,” or “certainly” related.

Efficacy was assessed at visits 1 (baseline), 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, and 16 using the MG-ADL score,8 the Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis (QMG) score,9 and the Myasthenia Gravis Composite (MGC)10 disease severity score, and revised 15-item Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life scale (MG-QoL15r),11 to evaluate the effect of efgartigimod on quality of life.

A validated ELISA using an efgartigimod-specific capturing antibody was used to determine efgartigimod serum levels. Pharmacokinetic calculations were performed using Phoenix WinNonLin 6.2 or higher (Pharsight Corporation, Palo Alto, CA). Pharmacokinetic measures of efgartigimod assessed in the study included maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax), time at Cmax (tmax), plasma concentration prior to dosing (Ctrough; plasma concentration observed at predose at visits 3, 5, and 7), apparent terminal half-life (t1/2,λz; calculated from [ln 2]/λz [visit 7 only]), and accumulation ratio (Rac; calculated as visit 7 Cmax/visit 1 Cmax).

Total IgG levels were determined using a validated ELISA method and anti-AChR antibodies were quantified using a commercially available radio receptor assay (IBL International, Hamburg, Germany; #RE21021).

Any patient discontinuing the study treatment was followed until the end of the study for safety.

Outcomes

This study was exploratory and not powered to address any predefined hypothesis. Safety was performed on the safety analysis set consisting of data of all patients in the randomized population who received at least one dose or part of a dose; the safety analysis was based on the actual treatment received. Exploratory efficacy analyses were performed on the full analysis set consisting of all randomized patients with at least one of the MG-ADL, QMG, MGC, and MG-QoL15r scales available for one of the postbaseline assessments up to day 78 along with the corresponding baseline value.

The primary endpoints of the study were safety and tolerability. Secondary endpoints included efficacy, as measured by the change from baseline to week 11 (visit 16) of the MG-ADL, QMG, and MGC disease severity scores, and by the effect on quality of life as measured by the MG-QoL15r score, and assessment of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic markers.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of approximately 36 screened patients was calculated to randomize approximately 24 patients (12 patients per treatment arm), and to have at least 20 patients who received at least 3 doses of either efgartigimod or placebo and who completed at least 2 weeks of follow-up after their last dose.

The population considered for safety analyses was the randomized population who received at least one infusion or part of an infusion of efgartigimod or placebo. The safety population was analyzed according to the treatment actually received.

The analysis of the secondary endpoint of clinical efficacy was performed on the full analysis set, defined as all randomized patients (allocated to a randomized treatment arm, regardless of whether they received the planned treatment or not) who had an evaluable efficacy endpoint, that is, at least one MG-ADL, QMG, MGC, or MG-QoL15r score being available within one of the postbaseline assessments up to visit 16 with the corresponding baseline value. The pharmacokinetic analysis population was the randomized population with at least one plasma concentration data value available for efgartigimod without major protocol deviations thought to influence pharmacokinetics. The pharmacodynamic analysis population was the randomized population with at least one nonmissing postdose pharmacodynamic measurement available without major protocol deviations thought to influence pharmacodynamics.

For the primary objective of safety and tolerability, all safety data were summarized descriptively.

For the secondary objective of clinical efficacy, the change from baseline was evaluated. Actual and change in data from baseline were summarized descriptively for each treatment by visits. Analyses of change from baseline by visit were performed using a mixed-model repeated-measures (MMRM) analysis from visit 1 to visit 16. The model included treatment, visit, and (treatment × visit) interaction terms as fixed effects, with baseline and (baseline × visit) terms as covariates. If the (baseline × visit) term was found to be not significant, then it was excluded from the model. An unstructured covariance matrix (or a simpler covariance matrix in case of no model convergence) for the repeated measures within patient was specified for the analysis. All tests of treatment effects were conducted at a 2-sided α level of 0.05. No inferential hypothesis was tested in these secondary variables and summary statistics and confidence intervals (CIs) for these were not adjusted for multiplicity. The p value, if presented, was not considered for any inference. Analysis of baseline characteristics was summarized appropriately via descriptive statistics or visual presentation. Categorical data such as responder analyses, counts, and frequencies were presented descriptively and for exploratory comparison analysis, the Fisher exact test, χ2 test, or Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test was performed. The difference in proportion responders along with the 95% CI was estimated using a logistic regression model adjusted for the baseline score. For the pharmacokinetic analysis, descriptive statistics were calculated for the serum concentrations and pharmacokinetic parameters of efgartigimod.

Data availability statement

The protocol of this trial is available from Dryad (supplemental material, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.4hk2039).

Results

We screened 35 patients between December 30, 2016, and July 31, 2017, of whom 24 patients were enrolled in this exploratory phase 2 study and randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to treatment with either 10 mg/kg IV efgartigimod or matched placebo (figure 1).

Figure 1. Study flow diagram.

Overview of number of patients screened and randomized over the efgartigimod and placebo treatment arms.

The patients were treated with 4 IV administrations of efgartigimod or placebo over a 3-week period followed by an 8-week observation period to understand the relation between reduction of autoantibodies and clinical score (figure 2). There was one discontinuation in the efgartigimod group (receiving rescue therapy at visit 10 due to lack of efficacy), but this patient was still evaluable for safety and efficacy.

Figure 2. Schematic design of the phase 2 study of efgartigimod in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis.

Arrows indicate time points of treatment administration; visit number and corresponding day after first administration are indicated. Only blood sampling at visits 9–16. Optional intermediate blood samplings at visit 2, visit 4, visit 6, and visit 8. *Visit window: ± 1 day. EoS = end of study; SoC = standard of care; V = visit.

The demographics and disease status (MGFA classification) were generally well-matched between the placebo and efgartigimod groups (table 1). The baseline QMG, MG-ADL, and MGC scores were comparable, while the baseline MG-QoL15r score was slightly higher in the efgartigimod group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and medical history of intent-to-treat population

No deaths, SAEs, or TEAEs leading to discontinuation of treatment occurred in the study.

The reported TEAEs were both infrequent and balanced between the efgartigimod and placebo groups. A summary table of TEAEs per treatment (overall in ≥2 patients) is provided in table 2.

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent safety outcomes in all treated patients (overall reported in ≥2 patients)

Most TEAEs were reported to be mild. One patient in the placebo group experienced a moderate headache and one patient in the efgartigimod group experienced a moderately severe episode of shingles on the arm preceded by infusion site pain. No severe TEAE was reported and no clinically significant changes in vital signs or ECG findings were observed.

The most frequently reported TEAEs (any grade) in patients who received efgartigimod were headache and reduced monocyte count, all of mild severity. Other, single TEAE reports considered as at least possibly related to efgartigimod and temporally associated with its administration included rhinorrhea, myalgia, pruritus, feeling hot, total lymphocyte count decrease, T-lymphocyte decrease, B-lymphocyte decrease, neutrophil count increase, injection site pain and pruritus, and shingles. The reported abnormal differential white blood cell counts were mild and asymptomatic, and were observed in 3 patients, of whom 2 were on chronic cortisone and azathioprine.

A herpes zoster (shingles) episode of moderate intensity on the infusion site arm was reported in 1 (8.3%) 63-year-old man with a history of rash, at visit 9, and was preceded, 1 week earlier, by injection site pain and considered related to efgartigimod.

The pharmacokinetic parameters were very similar in all efgartigimod-treated patients, without accumulation (geometric mean Rac = 0.9360) following each infusion, and with pharmacokinetic parameters after the last infusion similar to the one after the first (figure 3A). Serum concentrations of efgartigimod were still quantifiable in all patients at 21–28 days after the last infusion. The Cmax at visit 1 was 187 ± 58 μg/mL at a tmax of 2.37 ± 0.165 hours, and the t1/2,λz was 117.4 hours (i.e., 4.89 days) ± 18.84 hours (all values are mean ± SD).

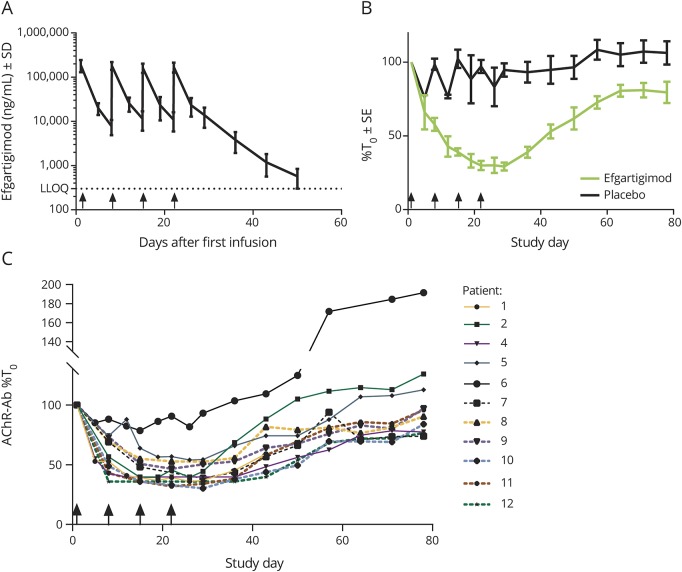

Figure 3. Blood serum analyses.

(A) Serum levels of efgartigimod. Values are mean ± SD. (B) Total immunoglobulin G (IgG) serum levels after efgartigimod and placebo treatment over the 11-week study. Values are mean ± standard error, and are expressed relative (%) to the respective IgG concentrations immediately prior to first dose at visit 1. (C) Individual serum anti–acetylcholine receptor (AChR) autoantibody profiles relative to baseline values. Values are individual values expressed relative (%) to the respective individual anti-AChR autoantibody concentrations immediately prior to first dose at visit 1; the anti-AChR autoantibody levels of patient 3 were below the limit of quantification. Arrows on the X-axis indicate time points of treatment administration. Ab = antibody; BLQ = below the limit of quantification; LLOQ = lower limit of quantification; T0 = pre-first-dose time point.

A total serum IgG reduction of approximately 40% compared to baseline was achieved in the first week (following the first dose) (figure 3B). This reduction further increased to a mean maximum of 70.7% after subsequent doses. IgG levels remained reduced by 50% or more for approximately 3 weeks. At 8 weeks following the last infusion, we observed a 20% reduction of total IgG levels. This rapid, substantial, and sustained reduction was seen across all IgG subtypes (figure e-1, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.4hk2039).

The reductions in serum IgG levels mirrored the observed potent reduction of anti-AChR autoantibodies, which are typically of the IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses (figure 3C). As early as 15 days after the first infusion, an approximately maximal reduction of 40%–70% of anti-AChR autoantibody level was reached in all patients except one, and this reduced level was sustained until day 29 after the first infusion, after which autoantibody levels gradually increased to approach baseline levels approximately 8 weeks after the last dose.

Positive postdosing antidrug antibody (ADA) titers were detected in 4 out of 12 patients receiving efgartigimod and in 3 out of 12 patients receiving placebo. In line with the results obtained in the phase 1 healthy volunteer trial,7 the majority of ADA signals in active-treated patients were just above the detection limit of the assay and were typically only found once or twice during the course of the trial. In one active-treated patient, positive postdose ADA titers were detected as of 2 weeks after the last infusion, and these titers may have the tendency to slightly increase over the course of the trial. Positive postdose ADA titers had no apparent effect on efgartigimod pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics.

The clinical improvement as assessed by different efficacy scales (MG-ADL, QMG, and MGC) and a quality of life scale (MG-QoL15r) showed an evolution in time that was consistent with the observed total serum levels of IgG and anti-AChR autoantibody (figure 4A). For all 4 scales, initial effects were noted as early as 7 days after the first infusion.

Figure 4. Clinical efficacy.

(A) Sensitivity analyses for clinical outcome measures. Values are mean ± standard error, and are expressed relative (point reduction) to the baseline zero value obtained immediately prior to first dose at visit 1; negative score is indicative of an improvement; dotted line delineates clinical significant zone, which is Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living (MG-ADL) ≥2 or Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis (QMG) ≥3; arrows on the X-axis indicate time points of treatment administration. *Statistically significant change from baseline (p ≤ 0.05). (B) Responder analyses for study days 29 and 36. Data are minimum point improvements on the outcome measures of the MG-ADL scale on days 29 and 36, which are the study days in the follow-up period where the pharmacodynamic effect was maximal; percentages of patients showing a clinical improvement of at least the specified value are indicated next to the bars. MG-QoL15r = 15-item Quality of Life scale for Myasthenia Gravis; MGC = Myasthenia Gravis Composite.

Maximal reduction in scores occurred as of 1–2 weeks after the last administration, which coincides with the maximal pharmacodynamic effect. This reduction reached a maximum mean of 5.7 points (39% reduction from baseline) on the QMG scale, 4.4 points (55% reduction) on the MG-ADL scale, 9.4 points (56% reduction) on the MGC scale, and 6 points (31% reduction) on the MG-QoL15r; the respective placebo values were −2.1 points (18%; QMG), −2.9 points (36%; MG-ADL), −4.4 points (30%; MGC), and −2.1 points (14%; MG-QoL15r). Despite the small size of the patient cohort treated with efgartigimod, statistical significance was reached for a 3-point change in QMG score after the first infusion (difference estimated with MMRM = −2.38; 95% CI [−4.63 to −0.13] and p = 0.0394), and statistical significance was reached at 29 and 36 days for MG-ADL, coinciding with maximal IgG reduction (differences and p values, respectively, −2.05 [−3.95 to −0.15]; p = 0.0356 and −2.08 [−4.12 to −0.04]; p = 0.0459). The MG-QoL15r score changed in a similar way (statistical significance at days 22, 29, and 43; differences and p values −3.72 [−7.41 to −0.02], p = 0.0489; −3.87 [−7.69 to −0.05], p = 0.0475; and −4.38 [−8.56 to −0.20], p = 0.0407, respectively).

In contrast to the IgG and autoantibody levels, which returned to baseline or close to baseline by the end of the study, the clinical scores gave a sustainable improvement throughout the entire study. At 78 days after first infusion, the QMG, MG-ADL, and MGC scores still were reduced by 4.8, 3.5, and 7.1 points, respectively. The MG-QoL15r score almost returned to baseline at this time point.

Responder analyses were performed at days 29 and 36 when IgG reduction was maximal (figure 4B). At any point reduction level, a greater percentage of efgartigimod-treated patients had a clinical improvement compared to placebo. Some patients treated with efgartigimod experienced a point improvement of ≥9 and as high as 11 on the MG-ADL scale and of ≥9 and as high as 18 in QMG score, while none of the placebo-treated patients reached these levels.

Of the efgartigimod-treated patients, 75% had a clinically meaningful and statistically significant improvement in MG-ADL score (MG-ADL ≥2)12 for a period of at least 6 consecutive weeks, vs 25% of patients on placebo (difference 50.34%; 95% CI [15.93–84.74]; p = 0.0391, Fisher exact test).

Discussion

In this exploratory phase 2 study in gMG, efgartigimod was well-tolerated. No patient withdrew for a safety concern, most AEs were characterized as mild and unrelated, and no apparent differences were observed with placebo. The safety data are in line with the overall favorable safety profile observed in the phase 1 healthy volunteer study.7 In addition, coadministration of efgartigimod with standard-of-care drugs used in the treatment of gMG did not induce apparent incompatibility (adverse) reactions.

The reported mild hematologic changes observed in 3 patients after starting efgartigimod treatment were asymptomatic and can to a large extent be explained by the concomitant use of corticosteroid and nonsteroidal immunosuppressants. Chronic use of cortisone and azathioprine, which was present in 2 of the 3 patients with hematologic abnormalities as part of their standard-of-care treatment of gMG, is indeed associated with reduced levels of lymphocytes and monocytes,13,14 which was already visible prior to study treatment initiation in these 2 patients.

One of the patients treated with efgartigimod experienced shingles (herpes zoster) on the infusion site arm. It should be noted that this patient was on standard-of-care therapy with prednisone (30 mg oral every other day combined with 5 mg at the alternate day) and mycophenolate mofetil (2,000 mg/d). Although treatment with mycophenolate and prednisone is known to increase the risk of herpes zoster infections,15–17 a correlation with efgartigimod treatment cannot be excluded.

The current study was also intended as a signal-finding study with secondary endpoints aiming to establish a correlation between levels of total and pathogenic IgGs and disease improvement.

The clinical proof-of-concept of FcRn antagonism in the treatment of gMG was successful since all of the patients in the efgartigimod treatment arm (n = 12) showed a rapid decrease in total IgG and autoantibody levels and 9 of them showed rapid disease improvement, with clear separation from placebo by 1 week after the first infusion despite the considerable placebo effect known to occur in other trials with patients with MG as well.18,19 The rapid onset and strong clinical improvement was observed consistently over all 4 assessed efficacy scales, encompassing both patient-reported (MG-ADL) and physician-reported (QMG) scales, with, despite the small size of the cohort, statistical significance reached at specific time points for the QMG, MG-ADL, and MG-QoL15r scales (p ≤ 0.05). Notwithstanding a short period of 3 weeks of exposure to the drug, a persistent clinical improvement of at least 6 weeks was achieved in a high proportion of patients. The clinical benefit in the efgartigimod treatment group maximized as of 1 week after administration of the last dose. At all MG-ADL and QMG thresholds, higher percentages of efgartigimod-treated patients showed clinical improvement compared to placebo, and at the highest thresholds, response was only observed in the efgartigimod treatment group, while the placebo group did not contain any responders.

A rapid and deep reduction in total IgG and IgG subtype levels was observed in all 12 efgartigimod-treated patients, which started already after the first administration and was maximal (around 70%) 1 week after the fourth infusion, similar to the observations made in the phase 1 study in healthy volunteers.7 The anti-AChR autoantibody levels followed the same pattern, with a comparable maximal decrease 1 to 2 weeks after the fourth administration, after which the autoantibody levels returned back to baseline values at 8 weeks after the last infusion. In earlier studies, corticosteroids had been found to lower IgG production20 as well FcRn expression21; however, this did not affect the IgG reduction achieved in the patients with MG in the current study, since a similar decrease was observed in the healthy volunteers.7

Compared to the rather short efgartigimod terminal half-life (4.89 days), the clinical effects were long-lasting (throughout the follow-up period, i.e., 8 weeks after the last efgartigimod administration). The clinical benefit of efgartigimod initially correlated with the IgG reduction but extended even after the IgG level had returned close to baseline. The duration of clinical improvement in the efgartigimod treatment group compared favorably to the relatively short-lived effect of plasmapheresis (2–4 weeks).22,23 In both approaches IgG and autoantibody return to basal levels in a comparable way, but the duration of the clinical effect is clearly different. Plasmapheresis removes the bulk of serum antibodies at one timepoint. In between sessions of plasmapheresis, IgG from the tissue redistributes and serum IgG increases again, resulting in a zigzag pattern of autoantibody and serum IgG levels.24 Efgartigimod showed continuous lowering of IgG levels consistent with a prolonged action after administration. Of course, efgartigimod is an antibody-like drug that has a prolonged mode of action, explaining the difference with plasmapheresis.

Although this exploratory study, with a small sample size of only 24 patients, was not powered to prove the efficacy of efgartigimod in gMG, a clinically statistically significant difference occurred at several time points. Moreover, the results are in line with the observations of an earlier study using traditional techniques for anti-AChR autoantibody lowering in the treatment of late-onset MG.25 In the latter study, the anti-AChR autoantibody reductions achieved with IVIg (29%), plasma exchange (63%), or immunoadsorption (55%) were similar to or lower than the 40%–70% reductions achieved with efgartigimod, and also resulted in clinical improvement and reduced hospital stay.

The same IgG-depleting strategy should be applicable to the treatment of patients with MG where the disease is mediated via IgG4 subclass autoantibodies against MuSK, a transmembrane tyrosine receptor kinase essential for AChR clustering at the neuromuscular junction, or against MuSK-related proteins.1–3

The pharmacokinetic findings of the phase 1 first-in-human trial were confirmed,7 with a fast reduction in serum concentrations of the compound following infusion, and absence of accumulation, which suggests a rapid and sustained binding of efgartigimod to FcRn. Combined with the prolonged pharmacodynamic effect in terms of reduction of anti-AChR autoantibody levels, and more relevant the associated clinical effect, tailored treatment of gMG with efgartigimod could potentially be supported.

The strong correlation between IgG level reduction and disease improvement validates the hypothesis that reducing pathogenic autoantibodies with an FcRn antagonist may offer an innovative approach to treat MG. A plethora of autoimmune diseases are thought to be driven by pathogenic IgGs26 and further studies will determine the applicability of FcRn antagonism as a therapeutic option beyond MG.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the patients who took part and their families as well as the efgartigimod principal investigators, subinvestigators, study coordinators, and other members of the Efgartigimod MG Study Group; Tonke van Bragt and Karin de Dier for their expert advice early in the study; Luc Geeraert for medical writing support; Ludo Haazen, Marqus Hamwright, Rebecca Rupert, Adam Terreri, Tim Van Hauwermeiren, David L. Lacey, and Pamela Klein for critical review of the manuscript; and Joke d’Artois for clinical study oversight. The Efgartigimod MG Study Group: Prof. Kristl Claeys (subinvestigator; Neurology Department, University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium); Dr. Exuperio Diez-Tejedor (subinvestigator; Department of Neurology and Stroke Center, La Paz University Hospital, Autonoma University of Madrid, Spain); Veena Mathew, BS (lead clinical research coordinator; MDA ALS and Neuromuscular Diseases Center, University of California-Irvine, Orange); Dr. Manlio Sgarzi (subinvestigator; USC Neurologia, Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Italy); Brittany Leigh Harvey (research support specialist; Neuromuscular Division, University of South Florida, Tampa); Dr. Jerrica Farias (subinvestigator; Neuromuscular Division, University of South Florida, Tampa); Dr. Rita Frangiomore (subinvestigator; Department of Neuroimmunology and Neuromuscular Diseases, Fondazione I.R.C.C.S. Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milan, Italy); Sarah Heintzman (research nurse; Neurology Department, The Ohio State University, Columbus); Dr. Robert de Meel (subinvestigator; Department of Neurology, Leiden University Medical Center [LUMC], the Netherlands); Manisha Chopra, MBBS (study coordinator; Department of Neurology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill); Dr. Paolo Emilio Alboini (subinvestigator; UOC Neurologia, USS Malattie Autoimmuni–Centro Sclerosi Multipla, Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli, Rome, Italy); Dr. Albert Hietala (subinvestigator; Neuroimmunology Unit, Karolinska University Hospital [Solna], Stockholm, Sweden); Dr. Angela Genge (principal investigator; Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital, Canada).

Glossary

- AChR

acetylcholine receptor

- ADA

antidrug antibody

- AE

adverse event

- CI

confidence interval

- Cmax

maximum observed plasma concentration

- FcRn

neonatal Fc receptor

- gMG

generalized myasthenia gravis

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IVIg

IV immunoglobulin

- IWRS

Interactive Web Response System

- MedDRA

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Authorities

- MG

myasthenia gravis

- MG-ADL

Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living

- MG-QoL15r

revised 15-item Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life scale

- MGC

Myasthenia Gravis Composite

- MGFA

Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America

- MMRM

mixed-model repeated measures

- QMG

Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis

- Rac

accumulation ratio

- SAE

serious adverse event

- TEAE

treatment-emergent adverse event

- tmax

time at maximum observed plasma concentration

Appendix 1. Authors

Appendix 2. Coinvestigators

Footnotes

Editorial, page 1079

Class of Evidence: NPub.org/coe

Study funding

This study was funded by argenx BVBA (Zwijnaarde, Belgium).

Disclosure

J. Howard, Jr., reports research support and grants from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx BVBA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Muscular Dystrophy Association, NIH (including the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease), PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute), and Ra Pharmaceuticals; and nonfinancial support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx BVBA, Ra Pharmaceuticals, and Toleranzia. V. Bril has received research support from CSL, Grifols, UCB, Bionevia, Shire, and Octapharma. T. Burns received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Alexion Pharmaceuticals and argenx BVBA. R. Mantegazza has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with BioMarin, Catalyst, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and argenx BVBA. Dr. Mantegazza has received research support from Sanofi-Genzyme, Teva, Bayer, and BioMarin. M. Bilinska and A. Szczudlik report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. S. Beydoun has received personal compensation for activities, compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Baxalta Grifols, Xenoport, MT Pharma, Sarepta, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, CSL, Daiichi, and Pfizer. F. Rodriguez De Rivera Garrido reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. F. Piehl has received research grants from Biogen, Novartis, and Genzyme, and fees for serving as Chair of DMC in clinical trials with Parexel. M. Rottoli has received research support and grants from Biogen, Teva, Novartis, and Merck. P. Van Damme has been part of advisory boards for Cytokinetics, Pfizer, and CSL Behring. T. Vu is a consultant and speaker for Alexion Pharmaceuticals. A. Evoli reports scientific award jury membership for Grifols. M. Freimer received research support and grants from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx BVBA, Muscular Dystrophy Association, NIH (including the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease), Ra Pharmaceuticals, AMmicus, Alnylum, UCB, and Catalyst. T. Mozaffar has served on advisory boards for aTyr, Alnylam, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Amicus, Sanofi-Genzyme, Ultragenyx, Sarepta, and MT-Pharma. In relation to these activities, he has received travel subsidies and honoraria. He has also served on the speaker's bureau for Sanofi-Genzyme, Grifols, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, and CSL. Dr. Mozaffar receives research funding from the Muscular Dystrophy Association, NIH, and the following sponsors: Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Amicus, aTyr, SanofiGenzyme, Grifols, Bristol-Myers-Squib, Idera, Ionis, and Ultragenyx. He serves on the data safety monitoring board for Acceleron. S. Ward is supported in part by a research grant funded by argenx BVBA. T. Dreier is a full-time employee of argenx BVBA. P. Ulrichts is a full-time employee of argenx BVBA. K. Verschueren is a full-time employee of argenx BVBA. A. Guglietta is a full-time employee of argenx BVBA. H. de Haard is a full-time employee of argenx BVBA. N. Leupin is a full-time employee of argenx BVBA. J. Verschuuren has been involved in MG research sponsored by the Princes Beatrix Fonds, NIH, FP7 European grant (#602420), and consultancies for argenx BVBA, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, and Rapharma; the LUMC receives royalties from IBL. All reimbursements were received by the LUMC. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Gilhus NE. Myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2570–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:1023–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips WD, Vincent A. Pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis: update on disease types, models, and mechanisms. F1000Res 2016;5:F1000 Faculty Rev-1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders DB, Wolfe GI, Benatar M, et al. International consensus guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: executive summary. Neurology 2016;87:419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roopenian DC, Akilesh S. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol 2007;7:715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ober RJ, Ward ES. Engineering the Fc region of immunoglobulin G to modulate in vivo antibody levels. Nat Biotechnol 2005;23:1283–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulrichts P, Guglietta A, Dreier T, et al. Neonatal Fc receptor antagonist efgartigimod safely and sustainably reduces IgGs in humans. J Clin Invest 2018;128:4372–4386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfe GI, Herbelin L, Nations SP, Foster B, Bryan WW, Barohn RJ. Myasthenia gravis activities of daily living profile. Neurology 1999;52:1487–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barohn RJ, McIntire D, Herbelin L, Wolfe GI, Nations S, Bryan WW. Reliability testing of the quantitative myasthenia gravis score. Ann NY Acad Sci 1998;841:769–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns TM, Conaway M, Sanders DB, Composite MG; MG-QOL15 Study Group. The MG Composite: a valid and reliable outcome measure for myasthenia gravis. Neurology 2010;74:1434–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns TM, Sadjadi R, Utsugisawa K, et al. International clinimetric evaluation of the MG-QOL15, resulting in slight revision and subsequent validation of the MG-QOL15r. Muscle Nerve 2016;54:1015–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muppidi S, Wolfe GI, Conaway M, Burns TM; MG Composite and MG-QoL15 Study Group. MG-ADL: still a relevant outcome measure. Muscle Nerve 2011;44:727–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FDA. Imuran (azathioprine) [online]. Available at: accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/016324s034s035lbl.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2018.

- 14.FDA. Highlights of prescribing information: Rayos (prednisone) [online]. Available at: accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/202020s000lbl.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2018.

- 15.Hamaguchi Y, Mori A, Uemura T, et al. Incidence and risk factors for herpes zoster in patients undergoing liver transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis 2015;17:671–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauzurica R, Bayés B, Frías C, et al. Disseminated varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: role of mycophenolate mofetil. Transpl Proc 2003;35:1758–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen D, Li H, Xie J, Zhan Z, Liang L, Yang X. Herpes zoster in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical features, complications and risk factors. Exp Ther Med 2017;14:6222–6228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard JF Jr, Barohn RJ, Cutter GR, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II study of eculizumab in patients with refractory generalized myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2013;48:76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howard JF Jr, Utsugisawa K, Benatar M, et al. Safety and efficacy of eculizumab in anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive refractory generalised myasthenia gravis (REGAIN): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:976–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMillan R, Longmire R, Yelenosky R. The effect of corticosteroids on human IgG synthesis. J Immunol 1976;116:1592–1595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martín MG, Wu SV, Walsh JH. Hormonal control of intestinal Fc receptor gene expression and immunoglobulin transport in suckling rats. J Clin Invest 1993;91:2844–2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuks JB, Skallebaek D. Plasmapheresis in myasthenia gravis: a survey. Transfus Sci 1998;19:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guptill JT, Juel VC, Massey JM, et al. Effect of therapeutic plasma exchange on immunoglobulins in myasthenia gravis. Autoimmunity 2016;49:472–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan AA. Therapeutic plasma exchange: core curriculum 2008. Am J Kidney Dis 2008;52:1180–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu JF, Wang WX, Xue J, et al. Comparing the autoantibody levels and clinical efficacy of double filtration plasmapheresis, immunoadsorption, and intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of late-onset myasthenia gravis. Ther Apher Dial 2010;14:153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sesarman A, Vidarsson G, Sitaru C. The neonatal Fc receptor as therapeutic target in IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci 2010;67:2533–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The protocol of this trial is available from Dryad (supplemental material, doi.org/10.5061/dryad.4hk2039).