Abstract

Background

Salivary flow alteration (SA), is a known unwarranted effect of schizophrenic medications. It manifest either as reduced (xerostomia) or increased (sialorrhea) SA, among treated schizophrenic patients. It is believed that the SA is due to action of the drugs/disease process involving the muscarinic receptor-3 to process acetyl choline, the common neurotransmitter. The genetic mediation behind the SA in such patients remains largely unexplored. We aimed to address the same by using curated literary databases to identify such relationship, if any existed.

Material and methods

Curated databases of Gene-Disease Association, www.DisGeNet.org and www.networkanalyst.ca were effectively used to identify the probable genes, strength of association and the drug-genes pathway that could be possibly be involved. The genes associated with schizophrenia and SA were analyzed in detail. Protein-Protein interaction (PPI) network proven experimentally in humans were used to identify the missing or unreported links.

Results

In all 28 genes associated with schizophrenia were linked to SA. The genetic network of schizophrenia and xerostomia involved FGFR2 gene prominently and network module was statistically significant (P = 9.87*10−8) was achieved that had xerostomia as a node, while schizophrenia (P = 0.025) had statistical significance. Sialorrhea had no statistical significance (P = 0.555). When schizophrenia and sialorrhea connections were analyzed for genetic interaction, only gene GCH1 emerged. On combining the three disease entities, the association of TAC1 gene with sialorrhea was also identified. Using PPI, the coordination of CHRM3, TAC1 and GPRASP1 gene were identified. This network involved several genes that has significant influence on calcium signaling pathway (P = 7.74*10−16), cholingeric synapse(P = 6 × 10−4), salivary secretion(P = 4.38*10-3), endocytosis(P = 8.23*10−4), TGFβ signaling pathway(P = 0.0031), gap junction (P = 4.08*10-3) and glutamergic synapse(P = 6.4*10−3). The involvement of G-receptor signaling protein product, GNAQ was established.

Discussion and conclusion

The possible genetic pathway of SA in schizophrenic patients are discussed in light of pharmacotherapeutics. Using the knowledge effectively would help to increase the quality of life of schizophrenic besides increasing the understanding to use saliva as a biomarker of prognosis of schizophrenia and its drug effects.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Xerostomia, Sialorrhea, Antipsychotic drugs, Genes, Protein-protein interaction

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a one of the chronic, debilitating mental illness. At a global level, about 1 in 100 persons suffer from this disorder. Yet, the patho-biology of this disorder is not entirely deciphered.1 Schizophrenia presents with a spectrum of genetic alterations, clinical signs and symptoms, including autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysfunction.1,2 The treatment of schizophrenia has evolved over the years. Each of these standard treatment procedures have their own merits and demerits.3 Non-adherence to prescribed drugs have evolved as a challenge in treatment. One of the reason for non-adherence of medications is extreme alterations in salivary flow.4, 5, 6 Some of the schizophrenic drugs cause xerostomia (less-salivation) while others cause sialorrhea (excess salivation). Schizophrenia literature has adequate reports of salivary flow alteration (SA).7,8 Treatment naive and those undergoing active treatment suffer from SA.9, 10, 11

Salivary glands (SG) produce saliva by the action of ANS (sympathetic and parasympathetic). The salivary nucleus (superior and inferior, SN) controls the salivary secretion. Trigeminal cranial nerve and nucleus of solitary tract convey the necessary, afferent sensory inputs to SN. The higher regions of the brain also exerts its influence over the SN. Regions such as hippocampus, hypothalamus and frontal lobe also influence the SN. These centers control response to agents that promote fear, anxiety, sleep and depression. As a response, these center secrete a variety of neurotransmitters. The SN receive these signals through their neural innervations. The processed signals, from SN reach SG via various ganglions and synapses. The receptors in the SG, notably the M3 Muscarinic receptor, stimulates the SG for secretion. As a response to the signals from the SN, the secretion of saliva occurs.7,8,12,13 Pharmacological agents used to treat schizophrenia also act on the SN and SG. The SG secretory cells are responsive to muscarinic M1 and M3 receptors, α1-and β1-adrenergic receptors, and certain peptidergic receptors such as substance P, Vaso-Intestinal Peptide.8 Also, NK-1 (Neurokinin-1) and M3Rs via another pathway, diacylglycerol and protein kinase C, γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) are involved in SG signaling.7 SG secretion also contains Substance-P (SP), Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP) and peptide histidine methionine (PHM) that could double as secretagouge signals. In humans SP does not act as a secretagogue while VIP and PHM, could possibly interact with the drugs such as clozapine and M1 receptors contributing to sialorrhea. Furthermore, VIPs are known to increase parasympathetic-mediated vasodilatation in SG, which also could possibly be involved in SA.14

Sialorrhea was associated as an adverse effect of schizophrenic drugs like clozapine, olanzapine, and venlafaxine (objectively assessed). Sialorrhea was a symptom associated with quetiapine and risperidone prescription. Clozapine had dual action of xerostomia and sialorrhea.7 Olanzapine is another atypical antipsychotic that has xerostomia as a potential outcome. Sialorrhea was observed in 31–72% of clozapine-treated patients, whereas xerostomia was reported more often amongst olanzapine-treated patients.7,15 Other atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine and risperidone cause xerostomia in 14.5 and 6.9% of study population, respectively as reported by Scully C.7 In rats, clozapine and its metabolite N-desmethylclozapine have opposing actions. It is reported that they cause excitation of the M1 receptor in parotid and submandibular SG causing a low-grade, continuous salivary secretion. On the other hand, inhibition of M3 receptor via ANS as well as by α-1-adrenergic receptors cause less flow of saliva. Hence, in absence of stimulation, stimulatory action of the drug dominates, creating an increased secretion. On the contrary, while during a meal, the salivation markedly decreases.16

There is alteration in salivary flow rate (SA) in treatment naive schizophrenia.9,10 Established ANS dysfunction in schizophrenics could contribute to this fact.2 Schizophrenia treatment requires use of drugs that interfere with signals of salivary secretion. This causes a myriad of salivary adverse effects.7 For effective treatment regimen adherence, control of SA becomes crucial.5,6 Hence understanding the interaction between: 1. Schizophrenia and altered salivary secretion (Sialorrhea/xerostomia) at a gene level; 2. Genes associated with salivary alteration with known pharmacological agents used for schizophrenia. The knowledge of such interaction would help as to understand the implication of SA in natural history of schizophrenia (treated and treatment naïve), particularly the ANS dysfunction, design better pharmocotherapeutic regime with minimal or no SA side effects. These would have a profound impact on the quality of life of schizophrenic patients. Also, understanding this mechanism would help to potentially use saliva as a non-invasive marker of the disease state, progression and effect of drug.1

Through this manuscript, we attempt to elucidate the existing literature for common genetic linkage between schizophrenia and salivary alterations. Also, we explore the relationship between such genes and medications used in treatment for schizophrenia.

2. Material and methods

As this work is based upon curated networks and secondary data analysis of data from previously published, open access databases, the work is not subjected to ethical committee clearance.

We searched curated database of GDA (gene-disease association) (www.DisGeNet.org), to identify the genes associated with schizophrenia - salivary flow alteration relationship. This database had assimilated data from repositories, Genomic Wide Association Studies (GWAS) catalogues and published peer reviewed literature. Perfection in the data mining process was earlier achieved by well-known algorithms.16 The website also has metrics to rank the genotype to phenotype relationship. At present (version-5, as accessed on last week of November 2018). It claims to have 561,119 gene-disease associations (GDAs), between 17,074 gene and 20,370 diseases, disorders, traits, and clinical or abnormal human phenotypes, and 135,588 variant-disease associations (VDAs), between 83,002 SNPs and 9169 diseases and phenotypes. We used search set - “Schizophrenia”, “Sialorrhea” and “Xerostomia”. In this manuscript, the definitions of the search terms were that of the Unified Medical Language System - Concept Unique Identifier (UMLS-CUI). They were C0036341, C0037036 and C0043352 respectively. From the results, schizophrenia associated genes that were also differentially expressed in sialorrhea and xerostomia identified as two sets, represented in standard gene symbols.

These set of genes, were combined and then analyzed for their exact relationship using the web-based platform for gene expression profiling & biological network analysis - www.networkAnalyst.ca.17 The network of association, is defined using node (visual representation of an involved entity), edge (visual representation of a relation and is the line that connect two nodes) and a seed (user supplied gene/protein). The parameters fed would be the degree (number of connections that a node has with other nodes, higher the number, more the important in the network) and the betweeness (number of shortest path, through a particular node, higher the number, it acts as a bottleneck in the network). Modules are tightly clustered subnetworks with more internal connections than expected randomly in the whole network. The platform does not consider any network that has less than 3 nodes. Depending upon the interactions and connectivity, the p values are calculated solely based on their connectivity. For the purpose of this study, degree and betweenness filters were set at 1 and included all network nodes for the GDA and betweenness at 0 for the drug target identification.

This site also assess the relationship between the genes and diseases, independently using the metrics from the www.DisGeNet.org to find the strength of the association in detail. The resultant networks that emerged are presented. Also, through the www.networkAnalyst.ca, we assessed the protein and drug target information. The related information was obtained from the www.drugbank.ca, version 5.0.0 that was released June 21, 2016.17 The resultant network are also presented. For the unexplained connection, generic protein-protein interaction assessment was used to identify the connecting links using the STRING interactome with medium confidence score of 400 using studies that had experimental evidence only.18

3. Results

Using the GDA website, we identified, that the schizophrenia had 1871 genes, sialorreha had 29 genes, and xerostomia had 54 genes associated as per the literature. Of all the genes related to sialorrhea, 24.14% (7 of the 29) genes were associated with schizophrenia while, the same for xerostomia was 38.89% (21 of the 54 genes). Schizophrenia shared 1.5% (28 of the 1871) genes with SA genes (sialorrhea = 7; xerostomia = 21). The details of the genes including name, class, and chromosome are provided in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Genes involved in the Salivary Flow Rate Alteration in Schizophrenia, as appearing in curated databases.

| Condition | Gene symbol | Gene Name | Protein Class | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sialorrhea | GCH1 | GTP cyclohydrolase 1 | hydrolase | 14q22.2 |

| Sialorrhea | HLA-B | major histocompatibility complex, class I, B | null | 6p21.33 |

| Sialorrhea | MECP2 | methyl-CpG binding protein 2 | transferase; nucleic acid binding | Xq28 |

| Sialorrhea | NRXN1 | neurexin 1 | cell adhesion molecule; transfer/carrier protein; transporter; protease; enzyme modulator; oxidoreductase; hydrolase; signaling molecule; extracellular matrix protein; receptor | 2p16.3 |

| Sialorrhea | PAK3 | p21 (RAC1) activated kinase 3 | null | Xq23 |

| Sialorrhea | TAC1 | tachykinin precursor 1 | signaling molecule | 7q21.3 |

| Sialorrhea | ZEB2 | zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2 | transcription factor | 2q22.3 |

| Xerostomia | ATN1 | atrophin 1 | null | 12p13.31 |

| Xerostomia | ATXN2 | ataxin 2 | nucleic acid binding | 12q24.12 |

| Xerostomia | B2M | beta-2-microglobulin | defense/immunity protein | 15q21.1 |

| Xerostomia | BMP6 | bone morphogenetic protein 6 | signaling molecule | 6p24.3 |

| Xerostomia | CAV1 | caveolin 1 | membrane traffic protein; enzyme modulator; transmembrane receptor regulatory/adaptor protein; structural protein | 7q31.2 |

| Xerostomia | CHRM3 | cholinergic receptor muscarinic 3 | receptor | 1q43 |

| Xerostomia | CYP2D6 | cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily D member 6 | null | 22q13.2 |

| Xerostomia | DAO | d-amino acid oxidase | null | 12q24.11 |

| Xerostomia | ERBB4 | erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 4 | null | 2q34 |

| Xerostomia | FGFR2 | fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 | null | 10q26.13 |

| Xerostomia | HLA-DRB1 | major histocompatibility complex, class II, DR beta 1 | defense/immunity protein | 6p21.32 |

| Xerostomia | NEFH | neurofilament heavy | null | 22q12.2 |

| Xerostomia | PON1 | paraoxonase 1 | null | 7q21.3 |

| Xerostomia | PPARGC1A | PPARG coactivator 1 alpha | transcription factor | 4p15.2 |

| Xerostomia | PTGS2 | prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | oxidoreductase | 1q31.1 |

| Xerostomia | SOD1 | superoxide dismutase 1 | oxidoreductase | 21q22.11 |

| Xerostomia | TARDBP | TAR DNA binding protein | null | 1p36.22 |

| Xerostomia | TNFRSF1A | TNF receptor superfamily member 1A | receptor | 12p13.31 |

| Xerostomia | TREM2 | triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 | defense/immunity protein; receptor | 6p21.1 |

| Xerostomia | VAPB | VAMP associated protein B and C | membrane traffic protein | 20q13.32 |

| Xerostomia | WNT1 | Wnt family member 1 | signaling molecule | 12q13.12 |

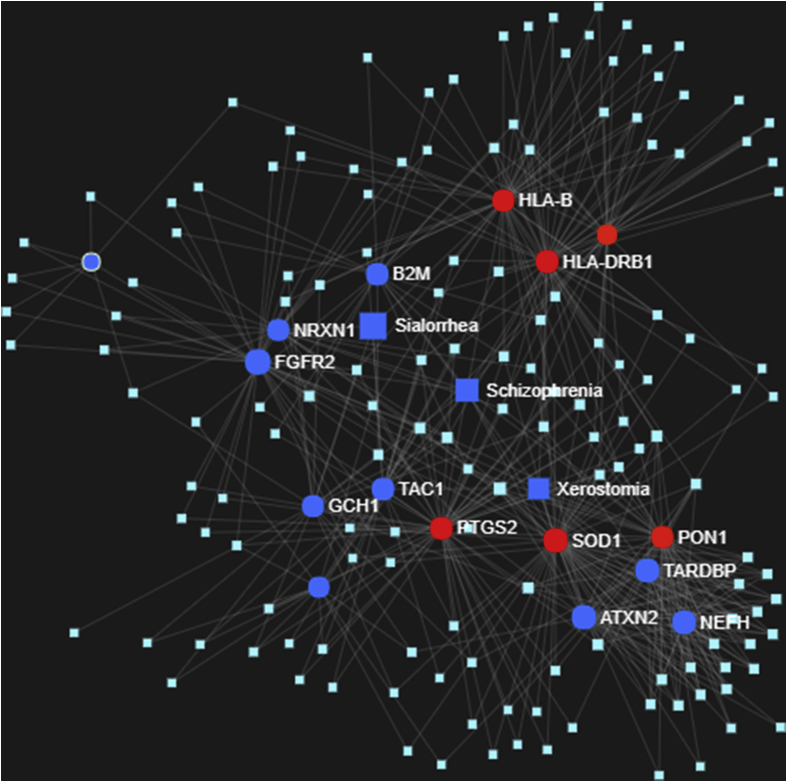

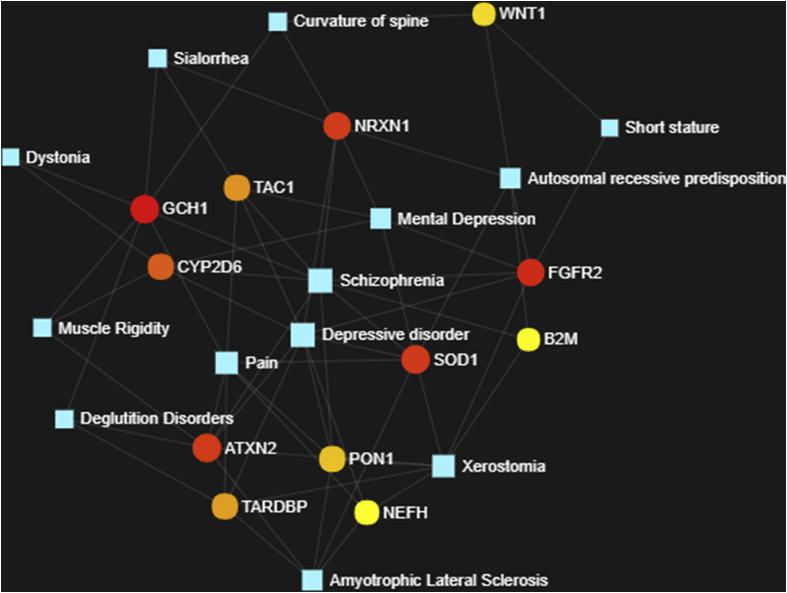

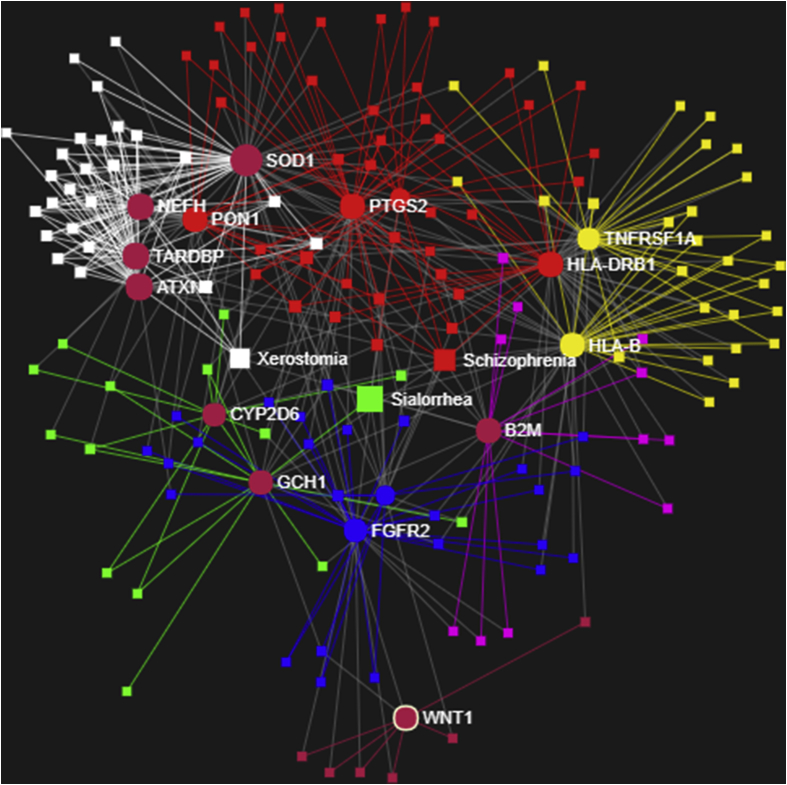

On analyzing the SA genes using the GDA interface of the www.networkAnalyst.ca, a single network was identified with 167 nodes, 47 edges and 16 seeds as single circular “continent” with no remarkable islands in Fruchterman-Reningold type of layout. The entire network is given in the Fig. 1 and closer look in Fig. 2. Schizophrenia had an average degree and betweeness of 13 and 1253.7, xerostomia had 8 and 372.54 while sialorrhea had 4 and 73.498 respectively. The network was further analyzed for functional enrichment module analysis using the walk-trap algorithm. In all 7 modules (0–6) were identified and presented in Fig. 3. Of this, three modules reached statistical significance. Most significance (P = 9.87*10−8, white color in Fig. 3) was achieved that had xerostomia as a node, while schizophrenia (P = 0.025, red color in Fig. 3) while sialorrhea had no statistical significance (P = 0.555, green color in Fig. 3). There was no module that had the three disorders as its part. When schizophrenia and sialorrhea connections were analyzed for genetic interaction, only gene GCH1 emerged. When the same was repeated for xerostomia, gene FGFR2 emerged. On combining the three disease entities, the association of TAC1 gene in sialorrhea was also identified. The interaction is outlined in Fig. 4.

Fig. 1.

Schizophrenia-Salivary Flow Alternation Genes-Disease Association network, Blue - Strong nodes from seed, Red - Identified nodes.

Fig. 2.

Close look of the Schizophrenia, Xerostomia and Sialorrhea from figure- 1 network.

Fig. 3.

Modules in the network. For color legend see text.

Fig. 4.

Focused network of the salivary alteration and schizophrenia related genes.

On using the protein and drug target information network for the combined set of genes (as in Table 1), there were 6 sub-network created of which only 2 had a significant (≥10) number of nodes. Of the 2 significant sub-network, one related to PTGS2 and FGFR2 gene had no schizophrenia related drug target. The other circular, radiating kind of network had CHRM3 gene at the center and had schizophrenia related drugs at the periphery. This network had 68 nodes, 67 edges and 1 seed – CHRM3. This gene had were 4 notable drugs used in schizophrenia treatment expressed among the many other drug interaction, as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Genes and Drugs interaction.

Further exploration of the link between CHRM3 and TAC1 gene using the generic protein-protein interaction assessment, revealed the involvement of GPRASP1 gene. The network had 57 nodes and 58 edges. It revealed that CHRM3 and TAC1 were linked via the GPRASP1 gene that interacted through the TACR1, TACR2, TACR3 receptor genes. Further KEGG pathway assessment of the 3 connectomes (Fig. 6) revealed that the calcium signaling pathway was upregulated in the network, involving CHRM3, TACR3, TACR2, TACR1, TGFβ1, GNAQ, OXTR, ADRB2, AGTR1, GRM5, TBXAZR, CHRM2, CHRM1, ADRB1, F2R, HTR7 and CHRM5 genes with P = 7.74*10−16. The cholingeric synapse was involved by the CHRM1, CHRM2, CHRM3, CHRM4, CHRM5 and GNAQ genes with P = 6 × 10−4. This network also had 4 nodes that were involved in salivary secretion – ADRB2, ADRB1, GNAQ and CHRM3 with P = 4.38*10−3. Similarly endocytosis (GRK6, F2R, ADRB1, ADRB2, CXCR2; P = 8.23*10−4), TGFβ signaling pathway (TGFβ1, BMP2, BMP8, BMP4; P = 0.0031), gap junction (ADRB1, GRM1, GRM5, GNAQ; P = 4.08*10−3) and glutamergic synapse (GRM1, GRM5, GRM8, GNAQ; P = 6.4*10−3) were involved.

Fig. 6.

Pathway analysis of Salivary flow alteration and Schizophrenia related genes.

4. Discussion

Salivary flow alteration in schizophrenics, is dependent on the type of drug taken, its pharmocokinetics and patho-biology.19 Depending on these, individual, immediate environmental and the genetic factors, the patient may have sialorrehea or xerostomia or may not have both. Xerostomia and sialorrhea, have their unique set of oral health related issues having adverse impact on quality of life. While xerostomia predisposes to dental caries, excessive salivation, especially in the night gives rise to chocking sensation and halitosis.7 A recent study among newly treated schizophrenics have identified the magnitude of the problem and its impact on quality of life.20,21

The exact mechanism by which the drugs cause SA is largely unknown. For patients on clonazipine, the adrenergic alpha-2 antagonism, muscarinic M4 agonism, reduction of laryngeal peristalsis and abolition of swallowing reflex have been cited as the reason for sialorrhea.19 As the ANS activity was diminished by the other atypical antipsychotic drugs, possibly the SA could be a side effect of these drugs.2 Muscarinic affinity of antipsychotics affects both the sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation. Any alteration in this could also be partially reflected as SA. Conventionally, it is very common for antipsychotics to cause dry mouth due to anticholinergic effects, especially given the fact that high number of M3 receptors in SG. Thus sialorrhea in these patients seems to be paradoxical. Yet, occurrence of such effects, especially in poly-drug treatment has been identified in clinical practice and literature. Most of these phenomenon have been attributed to the ANS side-effects. Irrespective of the mechanism, the oral health as well the quality of life is diminished due to the SA.7,8,19, 20, 21

The drugs that have an antagonistic actions on the autonomic receptors but that are used to treat dysfunctions in the various effectors of the ANS may also affect the functions of SG. In this context, schizophrenic drugs with anti-muscarinic actions are well-known to cause xerostomia as they prevent parasympathetic (cholinergic) innervation from activating the SG.8

The genetic association of the SA to schizophrenia and its treatment remains largely unexplained, given the dynamicity of the disease and treatment process.3,22 In this manuscript, we attempted to explore this link through the published evidences from available peer-reviewed literature. For this purpose we used curated website to search for the GDA using previously described methods. Xerostomia appears to be more commonly associated with schizophrenics, possibly due to large number of literature reports. The Table 1 and Fig. 1 indicates that only three signaling molecules – TAC1, WNT1 and BMP6 were involved and this may have a role to play in SA. SG have large number of receptors for signaling molecules.23

The strong relationship in connections of xerostomia and schizophrenia, as in Fig. 3, with a greater degree of statistical significance (P = 9.87 × 10−8) indicates that possibly, gene-network association of schizophrenia with xerostomia is unravelled. The association of GCH1 as a pathway intermediary has emerged. This gene's association with schizophrenia has been recently explored.24 This gene encodes for the Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), an essential cofactor for dopamine, serotonin and nitric oxide synthesis and vital chemical involved in psychosis. Alterations in BH4 expression is strongly associated with active schizophrenia.24 BH4 has known association with reduced salivary flow.24 Given the modulation of BH4 via nitric oxide, aquaporin complexes could also be implicated.25,26

Clinically, hypersalivation/sialorrhea are common manifestation with drugs like clozapine.27 For, sialorrhea TAC1 gene has emerged in association with schizophrenia. However, the connections failed to reach signification P-value (=0.555, green in Fig. 3), though it had 17 interactors, the degreeness and betweeness. This failure may be related due to lack of sufficient connectivity in genes leading to missing nodes and edges.17 This also indicates there could be other isoforms or pathways or genes that are yet to be identified to reach satisfactory statistical significance. The involvement of TAC1 gene with schizophrenia and sialorrhea is established in this part of the study. On further generic protein-protein interaction exploration, it was identified that the TAC1, in schizophrenia, possibly mediates CHRM3 possibly via the GPRASP1 gene.27,28 The GPRASP1 gene is G protein-coupled receptor associated sorting protein, shown previously to modulate lysosomal trafficking of D2 dopamine and playing a role in schizophrenia.30 The role of CHRM3 gene in schizophrenia is reported.28 With these interactions, it is clear that TAC1 has a definitive role in the association of sialorrhea and schizophrenia.

The protein-protein interaction linkage analysis identified the connectome of the TAC1, GPRASP1 and CHRM3 gene. This network analysis revealed significant gene interactions involving, those of the calcium signaling pathway (P = 7.74*10−16), cholingeric synapses (P = 6 × 10−4), salivary secretion (P = 4.38*10−3), endocytosis (P = 8.23*10−4), TGFβ signaling pathway (P = 0.0031), gap junction (P = 4.08*10−3) and glutamergic synapse (P = 6.4*10−3). The involvement of calcium signaling pathway, cholinergic/glutamergic synapses, salivary secretion indicate the involvement of the TAC1, GPASP1 and CHRM3 genes as a possible network for sialorrhea to occur.14,29,30 Possibly, this mechanism could be the way by which antipsychotics could cause sialohrrea.

As reported earlier, TAC1 is associated with Substance-P, Neurokinin A, Neuropeptide K and Neuropeptide Gamma.31 The SA by clozapine involved M3 receptors while olanzapine involved non-traditional SG receptors (such as NK-1 receptors). Gordoy reported that the olanzapine could evoke SG secretion the chronic preganglionically denervated submandibular gland and in the chronic post-ganglionically denervated parotid gland, post-junctional supersensitivity.31 Also, it is possible that olanzapine could play an SG excitatory role via alternate pathways such as non-SP related tachykinin receptors in humans. It is also possible that olanzapine stimulates non-tachykinin gland receptors such as calcitonin gene related peptide, which could mediate SG secretion or by increasing SG gland blood flow.31

Involvement of the TGF-β signaling pathway indicates the involvement of inflammation. SA due to persistent inflammation of SG, on use of olanzapine has been demonstrated in rats.31 From the results of this study, involvement of inflammation components such as HLA associated genes, TGF-β signaling pathway indicates that this aspect of SA with antipsychotic drugs need further investigation.

Strengths of present study: The present study is based on data mined from existing previous literature. Wide range of curated human based studies were employed to identify the GDA and generic PPI. Only those with experimental evidences were included for this study. The results of the study indicate that there is a strong gene associated mechanism behind the association with schizophrenia-SA with statistical significance. However, further validation would be needed to establish the findings of the study.

Limitations: Genes have varied functions at different phase of time, and varies with different tissues. The differential expression or linking of genes/products, may not be directly associated with the trait (SA) expressed. Though there is a strong association emerging as seen in this study, the role of these schizophrenia genes in SA and the drug-gene interaction is not fully established in this study. Clinical, real-time validation would be needed. Till such a study emerges that demonstrates the drug-gene modulation for SA in schizophrenia, the results of this study would largely remain empirical.

Clinical Relevance: The treatment goal in schizophrenia would be to control the psychosis episode and improve the quality of life. Drugs that are used to treat schizophrenia interferes with salivary flow is a large subset of patients and some of them very severely. Knowledge and checking for the gene-drug interaction, could be the first step involved in personalized medication concept in schizophrenia treatment. If and when, the knowledge emanated from this study is used clinically, the quality of life of schizophrenic patients would drastically improve. Alteration in existing pharamacotherapeutics would prove beneficial to them. Among the subset of schizophrenic patients, who does not adhere to treatment for the adverse effects associated with SA, this approach would be helpful to stick to treatment regime. With poly-drug therapy and combination therapy being favored to control negative symptoms, it would also be necessary to know the gene-drug-SA interaction, before deciding on the evidence basis of these combination.32

Future directions: The future studies in this direction should clearly have definitions of the xerostomia and sialorrhea. A range would be useful and participant variability would need to be factored in. Arbitrary dichotomies in differential gene expression should be done away. The gene interaction and position in reaction-expression-signaling cascade leading to SA needs to be considered. Study design would also need to avoid inappropriate yardsticks in measuring saliva flow rate, drug action, gene-drug interaction and other physical, physiological, psychological and neuro-pharmacological mechanism. The studies also need to have good sample size to demonstrate the rate of response, sufficient enough to demonstrate the gene-drug-schizophrenia-SA link. Also the SA after pharmacotherapy should also be studied as a subsequence and not a consequence to have a broader perspective. Using N-of-1 trial must be done, perhaps at institutional settings to determine the actual gene-schizophrenia-drug-SA relationship instead of a cross-sectional methodology.33

5. Conclusion

The GDA between the schizophrenia and SA have been established through this study. Xerostomia is associated with a different cascade of genes while the sialorrhea is associated with another set of genes. There is no overlap of genes identified in this study. The role of the inflammation and TAC1 genes in SA among treated and treatment naïve schizophrenics have to be explored further. The validation of the results of the study would be helpful to be start a clinical era of personalized medicine for schizophrenics.

Conflicts of interest

Author(s) have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Anusa Arunachalam Mohandoss, Email: anusamd@gmail.com.

Rooban Thavarajah, Email: t.roobanmds@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Nascimento J.M., Martins-de-Souza D. The proteome of schizophrenia. NPJ Schizophr. 2015;1 doi: 10.1038/npjschz.2014.3. Article number 14003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hattori S., Suda A., Kishida I. Association between dysfunction of autonomic nervous system activity and mortality in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatr. 2018;86:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Essali A., Rihawi A., Altujjar M., Alhafez B., Tarboush A., Alhaj Hasan N. Anticholinergic medication for non-clozapine neuroleptic-induced hypersalivation in people with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD009546. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009546.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salzmann-Erikson M., Sjodin M. A narrative meta-synthesis of how people with schizophrenia experience facilitators and barriers in using antipsychotic medication: implications for healthcare professionals. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;85:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maher S., Cunningham A., O'Callaghan N. Clozapine-induced hypersalivation: an estimate of prevalence, severity and impact on quality of life. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6:178–184. doi: 10.1177/2045125316641019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaves K.M., Serrano-Blanco A., Ribeiro S.B., Soares L.A.L., Guerra G.C.B., Alves M.S.C.F. Quality of life and adverse effects of olanzapine versus risperidone therapy in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. 2013;84:125–135. doi: 10.1007/s11126-012-9233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scully C. Drug effects on salivary glands:dry mouth. Oral Dis. 2003;9:165–176. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2003.03967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolff A., Joshi R.K., Ekström J. A guide to medications inducing salivary gland dysfunction, xerostomia, and subjective sialorrhea: a systematic review sponsored by the world workshop on oral medicine VI. Drugs R. 2017;17:1–28. doi: 10.1007/s40268-016-0153-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee A., Chakos M., Koreen A. Prevalence and clinical correlates of extrapyramidal signs and spontaneous dyskinesia in never medicated schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1724–1729. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.12.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCreadies R.G., Srinivasan T.N., Padmavati R., Thara R. Extrapyramidal symptoms in unmedicated schizophrenia. J Psych Res. 2005;39:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben-Aryeh H., Jungerman T., Szargel R., Klien E., Laufer D. Salivary flow rate and composition in Schizophrenic patients on Clozapine: subjective report and laboratory data. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:946–949. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proctor G.B., Carpenter G.H. Regulation of salivary gland function by autonomic nerves. Auton Neurosci Basic Clin. 2007;133:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proctor G.B., Carpenter G.H. Salivary secretion: mechanism and neural regulation in saliva: secretion and functions. In: Ligtenberg A.J.M., Veerman E.C.I., editors. first ed. vol. 24. 2014. pp. 14–29. (Monograph on Oral Sci, Karger, Basel, Karger). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiacco M.D., Quartu M., Ekstrom J. Effect of the neuropeptides vasoactive intestinal peptide, peptide histidine methionine and substance P on human major salivary gland secretion. Oral Dis. 2015;21:216–223. doi: 10.1111/odi.12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kulkarni R.R. Low-dose amisulpride for debilitating clozapine-induced sialorrhea: case series and review of literature. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37:446–448. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.168592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinero J., Bravo A., Queralt-Rosinach N. DisGeNET: a comprehensive platform integrating information on human disease-associated genes and variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D833–D839. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia J., Gill E.E., Hancock R.E.W. NetworkAnalyst for statistical, visual and network-based meta-analysis of gene expression data. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:823–844. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wishart D.S., Feuang Y.D., Guo A.C. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sockalingam S., Shammi C., Remington G. Clozapine- Induced Hypersalivation: a review of treatment strategies. Can J Psychiatr. 2007;52:377–384. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu K., Chou Y., Wen Y. Antipsychotic medications and dental caries in newly diagnosed schizophrenia: a nation wide cohort study. Psychiatr Res. 2016;245:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cockburn N., Pradhan A., Taing M.W., Kisely S., Ford P.J. Oral health impacts of medications used to treat mental illness. J Affect Disord. 2017;223:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roganovic J. Pharmacodynamic causes of xerostomia in patients on psychotropic drugs. Acta Sci Dent Sci. 2018;2:102–106. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clelland J.D., Read L.L., Smeed J., Clelland C.L. Regulation of cortical and peripheral GCH1 expression and biopterin levels in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Res. 2018;262:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart C.R., Obi N., Epane E.C. Effects of diabetes on salivary gland protein expression of Tetrahydrobiopterin and nitric oxide synthesis and function. J Periodontol. 2016 Jun;87(6):735–741. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.150639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamma G., Valenti G., Grossini E. 2018. Aquaporin Membrane Channels in Oxidative Stress, Cell Signaling, and Aging: Recent Advances and Research Trends. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. Article ID 1501847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Q., Cheng W., Li M. The CHRM3 gene is implicated in abnormal thalamo-orbital frontal cortex functional connectivity in first-episode treatment-naive patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2016;46:1523–1534. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradley S.J., Wiegman C.H., Iglesias M.M. Mapping physiological G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathways reveals a role for receptor phosphorylation in airway contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci Unit States Am. 2016;113:4524–4529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521706113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marley A., von Zastrow M. Dysbindin promotes the post-endocytic sorting of G protein-coupled receptors to lysosomes. PLoS One. 2010;5(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009325. e9325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Praharaj S.K., Jana A.K., Goswami K., Das P.R., Goyal N., Sinha V.K.S. Salivary flowrate in patients with schizophrenia on clozapine. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33:176–178. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181e204e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baum J.B., Dai Y., Hirmatsu Y., Horn V.J., Ambudkar I.S. Signalling mechanisms that regulate saliva formation. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:379–384. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040031701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Godoy T., Riva A., Ekstrom J. Salivary secretion effects of the antipsychotic drug olanzapine in an animal model. Oral Dis. 2013;19:151–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2012.01964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buoli M., Serati M., Ciappolino V., Altamura A.C. May selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) provide some benefit for the treatment of schizophrenia? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016 Jul;17(10):1375–1385. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2016.1186646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Senn S. Statistical pitfalls of personalized medicine. Nature. 2018;563:619–621. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-07535-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]