Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of different tranexamic acid (TXA) routes following primary total hip arthroplasty (THA).

Methods

We collected data from the National Health Database on patients registered from January 2013 to September 2017. The patients were divided based on TXA administration route into a control group (without TXA), intravenous group, topical group and combined group. The primary outcome was transfusion; secondary outcomes were total blood loss, haemoglobin level, decrease in haemoglobin on postoperative day 3, and incidence of complications.

Results

Data were collected on 7667 primary THA, 4662 with TXA and 3005 without TXA. The transfusion rate was 28.7% in the control group, 12.7% in the topical group, 8.9% in the intravenous group, and 6.1% in the combined group, and the inter‐group differences were significant (P < .01). The combined group showed significantly smaller total blood loss (1.23 ± 0.52 L), smaller reduction in haemoglobin level (26.5 ± 11.1 g/L) and higher haemoglobin level on postoperative day 3 (107.0 ± 15.5 g/L) than the other three groups (P < .05). The three TXA groups showed significantly lower incidence of deep vein thrombosis than the control group (0.08% vs 0.47%, P = .001) as well as a lower rate of other complications (0.34% vs 0.67%, P = .044).

Conclusion

TXA is effective and safe to decrease blood loss and transfusion following primary THA, regardless of whether it is administered intravenously, topically or both. Intravenous or combined routes may produce better haemostatic effects, so they may be suggested in the absence of contraindications.

Keywords: blood management, deep vein thrombosis, enhanced recovery, total hip arthroplasty, tranexamic acid

What is already known about this subject

In primary total hip arthroplasty, tranexamic acid is administered intravenously, topically or via both routes.

All three methods can reduce blood loss and transfusion requirement, but how they compare to one another in terms of efficacy is unclear.

What this study adds

This is one of the few head‐to‐head comparisons of the three common TXA administration routes.

The results suggest that intravenous or combined administration may provide better haemostatic effect.

The study provides one of the best‐powered analyses of TXA safety in primary total hip arthroplasty.

1. INTRODUCTION

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is performed in end‐stage hip joint diseases to restore smooth mobility and range of motion as well as alleviate pain, which allows patients to retain a wide range of daily activities.1 The demand for THA is increasing as the population ages; by 2030, demand in the US alone will grow by 174% to 572,000 procedures.2 Substantial postoperative blood loss is one of the major complications, which may result in acute anaemia leading to a delay in recovery and wound healing, as well as increased risk of mortality.3 Although allogeneic blood transfusion is an effective treatment for postoperative anaemia, transfusion is not risk‐free: it carries the risk of disease transmission, haemolysis, transfusion‐related acute lung injury and transfusion‐associated circulatory overload,4, 5, 6 as well as infection and increased overall healthcare costs.

In order to minimize blood loss, transfusion requirement and associated risks, numerous strategies for bleeding management have been used, including cell salvage, erythropoiesis‐stimulating agents, and anti‐fibrinolytic agents.7, 8, 9, 10 Tranexamic acid (TXA), a synthetic analogue of the amino acid lysine, can competitively inhibit the activation of plasminogen by binding to specific sites on both plasminogen and plasmin,11 thus inhibiting the degradation of fibrin and breakdown of blood clots. Several studies suggest that TXA reduces blood loss in joint arthroplasty without increasing risk of thromboembolic complications.12, 13, 14 TXA is also widely accepted as effective for reducing blood loss and transfusion requirement in primary THA, but its safety and optimal administration route are controversial.15

TXA can be administered intravenously, topically, orally or by a combination of these routes.16, 17, 18, 19 Intravenous administration is the most frequent route, but concerns over risk of thromboembolic events have led to interest in topical administration,20 and several studies have investigated the advantages of combining intravenous and topical methods.19 Few studies have compared all three routes of TXA administration head‐to‐head, and safety of TXA in THA still needs confirmation in larger samples.

The purpose of the present study was to compare efficacy of TXA administered intravenously, topically or via both routes in terms of allogeneic blood transfusion, total blood loss and postoperative haemoglobin level in THA. In addition, we wanted to address the safety of these regimens compared to a non‐TXA control group.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

This prospective cohort study was conducted between January 2013 and September 2017 in 25 large centres for joint reconstruction (Table S1) within the framework of a Chinese National Health Ministry program (201302007). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (2012‐268). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to surgery.

2.2. Patient cohort

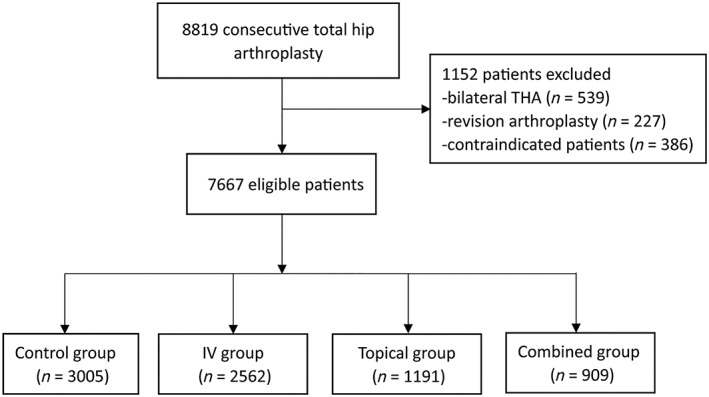

Patients were included if they (1) were over the age of 18 and undergoing primary unilateral THA for end‐stage hip joint disease such as osteoarthritis, osteonecrosis of the femoral head or developmental dysplasia of hip; (2) had a normal preoperative level of platelets and normal coagulation; and (3) showed normal results on preoperative lower limb Doppler ultrasound. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) history of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism), (2) clotting disorders, (3) cardio‐ or cerebrovascular conditions (history of myocardial infraction or stroke) within the previous 3 months, (4) known allergy to TXA, or (5) serious liver or kidney dysfunction. These exclusion criteria reflect conservative guidelines20 that recommend using TXA cautiously in patients at high risk of thrombosis. After exclusion of patients undergoing bilateral or revision arthroplasty and patients with other contraindications, a total of 7667 patients were included (Figure 1). Patients were divided into a control group that received no TXA (n = 3005) or into three groups that received TXA by different routes of administration: topical (n = 1191), intravenous (n = 2562) or the combination of both (n = 909). Their characteristics are described in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram describing the number of patients included

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included patients

| Control (n = 3005) | Topical TXA (n = 1191) | IV TXA (n = 2562) | Combined (n = 909) | P‐valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.7 (13.1) | 62.1 (9.7) | 61.2 (10.4) | 61.5 (8.9) | 0.08 |

| Female (n, %) | 1632 (54.3%) | 617 (51.8%) | 1425 (55.6%) | 468 (51.5%) | 0.06 |

| Height (cm) | 164.4 (8.1) | 163.5 (8.3) | 162.5 (7.5) | 162.1 (7.6) | 0.59 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.2 (10.8) | 64.2 (11.0) | 64.0 (9.5) | 63.0 (9.6) | 0.17 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 23.7 (3.3) | 23.9 (3.3) | 24.2 (3.1) | 24.2 (3.2) | 0.36 |

| Diagnosis | 0.14 | ||||

| OA | 983 (32.7%) | 396 (33.2%) | 831 (32.4%) | 291 (32.0%) | |

| DDH | 659 (21.9%) | 233 (19.6%) | 509 (19.9%) | 195 (21.5%) | |

| ONFH | 1016 (33.8%) | 403 (33.8%) | 856 (33.4%) | 296 (32.6%) | |

| Others | 347 (11.5%) | 159 (13.4%) | 366 (14.3%) | 127 (14.0%) | |

| ASA | 0.24 | ||||

| I | 945 (31.4%) | 400 (33.6%) | 876 (34.2%) | 301 (33.1%) | |

| II | 1587 (52.8%) | 626 (52.6%) | 1312 (51.2%) | 485 (53.4%) | |

| III | 473 (15.7%) | 165 (13.9%) | 374 (14.6%) | 123 (13.5%) | |

| Anaesthesia | 0.10 | ||||

| General | 2375 (79.0%) | 938 (78.8%) | 2054 (80.2%) | 693 (76.2%) | |

| Spinal + CSE | 630 (21.0%) | 253 (21.2%) | 508 (19.8%) | 216 (23.8%) | |

| Drainage (n, %) | 2174 (72.3%) | 875 (73.5%) | 1839 (71.8%) | 665 (73.2%) | 0.69 |

| Physical prophylaxis | 2086 (69.4%) | 873 (73.3%) | 1791 (69.9%) | 644 (70.8%) | 0.09 |

| Chemical prophylaxis | 0.53 | ||||

| LMWH | 2020 (67.2%) | 776 (65.2%) | 1679 (65.8%) | 607 (66.8%) | |

| Xa inhibitor | 985 (32.8%) | 415 (34.8%) | 873 (34.2%) | 302 (33.2%) | |

| Operation time (min) | 74.6 (9.4) | 79.6 (9.6) | 73.9 (6.4) | 79.7 (8.3) | 0.28 |

| Crystalloid fluid (mL) | 1083.2 (634.0) | 1047.3 (571.0) | 946.0 (480.3) | 953.8 (357.9) | 0.36 |

| Hb level (g/L) | 131.4 (17.0) | 131.2 (16.4) | 131.2 (16.9) | 132.2 (16.8) | 0.11 |

Values were presented as mean with standard deviation or number with frequency in parentheses.

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; CSE, combined spinal‐epidural anaesthesia; DH, development dysplasia of hip; Hb, haemoglobinOA, osteoarthritis; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; ONFH, osteonecrosis of femoral head.

Using one‐way ANOVA test and chi‐squire test.

2.3. TXA administration

In the topical group, a dose of 2–3 g TXA was applied topically during acetabular and femoral preparation. In the intravenous group, a dose of 15–20 mg/kg TXA was injected 5–10 minutes prior to incision. In the combined group, a dose of 15–20 mg/kg TXA was administered 5–10 minutes before incision, and 1.5 g TXA was topically applied during surgery according to the Chinese Orthopedic Association consensus guidelines for application of perioperative anti‐fibrinolytic agents during total hip and knee arthroplasty.21 Route of TXA administration was decided based on standard practices at the participating hospitals. TXA was administered before the incision to inhibit fibrinolytic activity at the initial stage and minimize blood loss,22 and to take into account the time needed for systemic TXA concentration to peak after injection.23 In fact, guidelines of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons recommend that TXA be administered prior to incision in primary total joint arthroplasty to reduce blood loss and transfusion requirement.20

During surgery, anaesthetists decided on whether blood transfusion was necessary; after surgery, attending physicians made these decisions. The criteria for blood transfusion were the same as those recommended by the Chinese National Ministry of Health: (a) haemoglobin < 70 g/L or (b) 70–100 g/L with symptomatic anaemia, defined as light‐headedness, palpitations, fatigue precluding participation in therapy, or shortness of breath not due to other causes.

2.4. Surgical procedures and anaesthesia

All procedures were conducted by 29 surgeons at the 25 centres, and a fully uncemented THA was performed in all patients. The posterolateral approach was used in 6823 of 7667 hips (89%), the lateral approach in 690 (9%), and the direct anterior approach in 153 (2%). General anaesthesia was used in 6060 of 7667 patients (79%), and spinal or combined spinal‐epidural anaesthesia (CSE) in the remaining 21% of patients; this decision depended on what the anaesthesia team considered most appropriate for the individual patient. Postoperative wound drainage was used in 5553 of 7667 patients (72%). Preoperative oral carbohydrate treatment and intraoperative goal‐directed fluid therapy were used when judged necessary by the attending physicians.

2.5. Prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism

Physical prophylaxis and chemoprophylaxis were implemented to prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE). Exercises to strengthen dorsal and plantar flexion as well as the quadriceps muscle were initiated as soon as possible after admission. Postoperatively, 70% of all patients received an intermittent pneumatic compression device upon arrival in the recovery room, and ambulation was started on postoperative day 1. All patients received routine perioperative chemical prophylaxis against VTE according to Chinese Orthopedic Association consensus guidelines.21 Doppler ultrasound was not applied routinely. If deep venous thrombosis (DVT) was clinically suspected, ultrasound was performed immediately. Pulmonary embolism (PE) was diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and enhanced computed tomography of the chest. All patients were followed up for 3 months postoperatively.

2.6. Outcome measures

The following patient data were collected: age, gender, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) rating, anaesthetic type, comorbidities, operation time, intraoperative fluids, drainage, anticoagulation, length of hospital stay, haemoglobin level and hematocrit (preoperative, on admission and on postoperative days 1 and 3), transfusion, DVT, PE and adverse events such as mortality, stroke and cardiac infarction.

The primary outcome was transfusion requirement before discharge. Secondary outcomes were haemoglobin level, total blood loss, length of hospital stay, DVT, PE and other adverse events. Total blood loss was calculated using the Gross formula24 and Nadel formula.25 Total blood loss was calculated as:

where hematocritpre refers to preoperative hematocrit; hematocritpost, to hematocrit on the morning of postoperative day 3; and hematocritavg, to the average of the pre‐ and postoperative hematocrit. Total blood loss was measured on postoperative day 3 because previous studies have shown that haemoglobin levels decrease after surgery and reach a minimum on postoperative days 3–4.22

Patient blood volume (PBV) in litres was assessed according to the formula:24

where k 1 = 0.3669, k 2 = 0.03219 and k 3 = 0.6041 for men; and k 1 = 0.3561, k 2 = 0.03308 and k 3 = 0.1833 for women. If either reinfusion or allogeneic transfusion was performed, total blood loss was calculated by adding the change in hematocrit to the volume transfused.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using SPSS 21.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) with a significance threshold of P < .05. For continuous, normally distributed data (e.g. TBL, haemoglobin level), one‐way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test was performed. For categorical data (e.g. transfusion rate, VTE), the chi‐squared or Fisher's exact test with post hoc Bonferroni P‐value correction was conducted.

2.8. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY.26

3. RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics were comparable among the four patient groups (Table 1). The allogeneic blood transfusion requirement was significantly lower in each TXA group than in the control group (all P < 0.001, Table 2). In TXA groups, the frequency of transfusion was lowest in the combined group (6.1%), which was significantly lower than in the intravenous group (8.9%, P < .001) and topical group (12.7%, P < .001). The difference in frequency was also significant between the intravenous group and combined group (P = .007).

Table 2.

Transfusion requirement compared among groups

| Control group (n = 3005) | Topical group (n = 1191) | IV group (n = 2562) | Combined group (n = 909) | P‐valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfusion (n, %) | 861 (28.7%) | 152 (12.7%) | 229 (8.9%) | 55 (6.1%) | < 0.001 |

| P‐value b | |||||

| Topical group | < 0.001 | ||||

| IV group | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Combined group | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.007 |

Values are presented as number with frequency in parentheses.

Using chi‐squire test for comparison among groups.

Using chi‐squire test for pairwise comparison, P‐value was corrected by Bonferroni method with a significant threshold of <0.008.

The total blood loss was significantly lower in the TXA groups than in the control group (Table 3). Mean total blood loss was lowest in the combined group (0.85 ± 0.34 L), followed by the intravenous group (0.91 ± 0.42 L) and topical group (1.08 ± 0.57 L). Differences among the groups were significant.

Table 3.

Total blood loss compared among groups

| Control group (n = 3005) | Topical group (n = 1191) | IV group (n = 2562) | Combined group (n = 909) | P‐valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total blood loss (L) | 1.23 (0.52) | 1.08 (0.57) | 0.91 (0.42) | 0.85 (0.34) | < 0.001 |

| P‐value b | |||||

| Topical group | 0.007 | ||||

| IV group | < 0.001 | 0.002 | |||

| Combined group | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.049 |

Values are presented as mean, with standard deviation in parentheses.

Using one‐way ANOVA for comparison among groups.

Using Tukey's post hoc test for pairwise comparison.

The haemoglobin level on postoperative day 3 was significantly higher in each TXA group than in the control group (Table 4). Among the TXA groups, the mean haemoglobin level on postoperative day 3 was highest in the combined group (107.0 ± 15.5 g/L), followed by the intravenous group (101.8 ± 16.4 g/L, P < .001) and topical group (100.7 ± 16.0 g/L, P < .001). Intravenous TXA tended to be associated with higher haemoglobin level on postoperative day 3 than topical TXA, but the difference was not significant (P = .877).

Table 4.

Haemoglobin level on postoperative day 3 compared among groups

| Control group (n = 3005) | Topical group (n = 1191) | IV group (n = 2562) | Combined group (n = 909) | P‐valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin on postoperative day 3 (g/L) | 96.7 (13.2) | 100.7 (16.0) | 101.8(16.4) | 107.0 (15.5) | < 0.001 |

| P‐value b | |||||

| Topical group | 0.05 | ||||

| IV group | < 0.001 | 0.877 | |||

| Combined group | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Values are presented as mean, with standard deviation in parentheses.

Using one‐way ANOVA for comparison among groups.

Using Tukey's test for pairwise comparison.

The reduction in haemoglobin level on postoperative day 3 was significantly lower in the TXA groups than in the control group (Table 5). Among the TXA groups, the reduction was smallest in the combined group (26.5 ± 11.1 g/L), followed by the intravenous group (29.1 ± 16.2 g/L, P = .002) and topical group (30.7 ± 13.0 g/L, P = .022). The reduction was similar between the topical and intravenous groups (P = .663).

Table 5.

Reduction in haemoglobin level on postoperative day 3 compared among groups

| Control group (n = 3005) | Topical group (n = 1191) | IV group (n = 2562) | Combined group (n = 909) | P‐valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drop in haemoglobin (g/L) | 36.5 (13.0)a | 30.7 (15.5)b | 29.1 (16.2)bc | 26.5 (11.1)d | < 0.001 |

| P‐value b | |||||

| Topical group | 0.004 | ||||

| IV group | < 0.001 | 0.663 | |||

| Combined group | < 0.001 | 0.022 | 0.002 |

Values are presented as mean, with standard deviation in parentheses.

Using one‐way ANOVA for comparison among groups.

Using Tukey's test for pairwise comparison.

Postoperative complications are shown in Table 6. The TXA groups showed significantly fewer DVTs (0.08%) than the control group (0.47%, P = .001), as well as significantly fewer total complications (0.34% vs 0.67%, P = .044). Among the TXA groups, the incidence of DVTs differed significantly only between the intravenous and control groups (P = .007). No significant differences were observed among the four groups in incidence of other complications or adverse events.

Table 6.

Postoperative complications

| Control group (n = 3005) | TXA (n = 4662) | Topical group (n = 1191) | IV group (n = 2562) | Combined group (n = 909) | P‐valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVT | 14 (0.47%)b | 4 (0.08%) | 1 (0.08%) | 2 (0.07%)b | 1 (0.11%) | 0.016 |

| PE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ |

| Stroke | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ |

| AMI | 1 (0.03%) | 2 (0.04%) | 0 | 1 (0.04%) | 1 (0.11%) | 0.590 |

| AHF | 2 (0.07%) | 1 (0.02%) | 1 (0.08%) | 0 | 0 | 0.496 |

| UTI | 0 | 2 (0.04%) | 1 (0.08%) | 1 (0.04%) | 0 | 0.354 |

| PI | 3 (0.09%) | 3 (0.06%) | 0 | 3 (0.12%) | 0 | 0.782 |

| SSI | 1 (0.03%) | 2 (0.04%) | 0 | 1 (0.04%) | 1 (0.11%) | 0.589 |

| Oozing | 2 (0.06%) | 2 (0.04%) | 1 (0.08%) | 1 (0.04%) | 0 | 0.898 |

| Total | 20 (0.67%) | 16 (0.34%) | 4 (0.34%) | 9 (0.35%) | 3 (0.33%) | 0.254 |

Values were expressed as number with frequency.

AHF, acute heart failure; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; PI, pulmonary infection; SSI, surgical site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Using chi‐squire test or Fisher's exact test.

Using chi‐squire test for pairwise comparison, P‐value was corrected with Bonferroni method, significant threshold was P < 0.008.

4. DISCUSSION

The efficacy of TXA in reducing blood loss and transfusion requirement has been confirmed in numerous studies but there has been debate regarding the best route of administration.15, 27 Several studies have compared the efficacy of topical and intravenous administration of TXA,28, 29 and others have compared the efficacy of combined administration versus intravenous or topical TXA in primary THA.19, 30 While routes of TXA administration have been compared for total knee arthroplasty by our own group,31 few studies have directly compared the three routes in THA. In addition, concerns still exist about the safety of TXA in primary unilateral THA.15, 32

The present study therefore substantially extends our own previous work and the literature more broadly by comparing, in a large sample, the efficacy of TXA administered topically, intravenously or both. Our results suggest that TXA is associated with less blood loss, lower allogeneic blood transfusion requirement and lower incidence of complications, no matter whether it is given topically, intravenously or both. Our results further suggest that combined administration of TXA leads to less blood loss after THA than intravenous or topical administration.

Concerns about thromboembolic complications of intravenous administration have promoted interest in topical application of TXA, which is associated with 70% lower systemic absorption.33 Comparative efficacy of intravenous and topical TXA remains controversial.22, 29, 34 In our previous study,22 we showed that intravenous TXA was associated with lower total blood loss (878.03 vs 905.07 mL), smaller decrease in haemoglobin (3.36 vs 3.89 g/dL) and lower incidence of transfusion (4.3% vs 5.7%) than topical TXA. The differences in total blood loss and transfusion rate were not significant, perhaps because each treatment arm contained only 70 patients. Similarly, another study found comparable efficacy and safety between topical and intravenous TXA.34 In the present larger study, intravenous TXA was associated with significantly lower transfusion requirement (8.9% vs 12.7%, P < .001) and total blood loss. Nevertheless, the haemoglobin level and decrease in haemoglobin level on postoperative day 3 were similar between the two groups. This may reflect the fact that a single bolus of intravenous or topical TXA can maintain haemostasis for less than 24 hours because of the drug's limited half‐life in the body. This limitation is difficult to avoid in the case of topical application of TXA, as applying a high concentration (50 or 100 mg/mL) topically to ensure long contact time with tissue can cause significant toxicity to periarticular tissue.35, 36 We believe that intravenous administration of TXA may be preferable to topical TXA because of its better antifibrinolytic effect.

The advantage of intravenous application is that within 5–15 minutes, TXA distributes widely throughout the extra‐ and intracellular compartments at a pharmaco‐active plasma concentration.23 In THA, fibrinolysis initiates upon incision, so intravenous injection of TXA prior to incision could inhibit fibrinolysis from its initial stage.22 Topical application, for its part, may help maintain maximum concentration by inhibiting local fibrinolysis.33 Theoretically, intraoperative application of topical TXA could further achieve targeted inhibition of local fibrinolysis and reduce blood loss in primary THA. Indeed, the results of our study suggest that combined administration of TXA further reduces transfusion requirement by 52% compared to topical administration alone or by 31% compared to intravenous administration alone. Consistent with previous work,19, 22 the combined group in our study showed higher postoperative haemoglobin levels than the other TXA groups, which should enhance recovery.

We observed significantly higher incidence of DVT in the control group (0.47%) than in the TXA group (0.08%, P = .001). This result is consistent with a retrospective study12 in which patients receiving TXA in THA showed a lower rate of thromboembolic complications than those who did not receive TXA (0.6% vs 0.8%, P < .01). The lower incidence of DVT may be due to lower blood loss, less transfusion requirement and higher postoperative haemoglobin level, resulting in enhanced postoperative recovery and earlier ambulation.

Our findings need to be interpreted in light of the following shortcomings. First, our study was not randomized, which may be a confounding factor. The decision on the route of TXA administration was made according to standard practices at the respective study sites as well as national consensus guidelines. On the other hand, all four patient groups showed similar baseline characteristics, suggesting that non‐randomization in our study did not substantially bias our results. Second, surgeries in our multicentre study were performed by different surgeons in different hospitals, which might be another confounding factor. On the other hand, it may also make our results more representative of actual clinical practice. Third, we excluded patients who underwent simultaneous or staged bilateral THAs, or revision hip arthroplasty; therefore, our findings may not be applicable to these patients, and further studies are warranted to investigate efficacy of different TXA administration routes in these subpopulations. Fourth, we excluded patients at high risk of thromboembolic events, such as patients with a history of VTE, stroke, myocardial infarction or chronic cancer. Therefore, our results may not be relevant to this patient group. Some medical centres provide TXA to such patients, in contrast to the more conservative approach common at many hospitals worldwide and formally recommended by Chinese and American orthopaedic associations.20, 21 Since some retrospective studies have suggested that TXA can be safe and beneficial in such patients,37, 38 future work should be performed to confirm this issue with prospective design. Fifth, we did not routinely screen patients for DVT or PE unless they presented with clinical symptoms. Since post hoc analysis suggested a power of >0.99 for our sample size, we believe that our results on TXA safety in primary THA are reliable, although they likely underestimate the incidence of VTE, especially asymptomatic DVT and non‐fatal PE.

In spite of these limitations, this study extends the literature by showing, through parallel comparisons using a large sample, how the different routes of TXA administration compare with one another. Future studies should investigate kinetics and variation in perioperative fibrinolysis during THA and attempt to identify appropriate serum markers of fibrinolysis in order to guide antifibrinolytic therapy for individual patients. They should also examine the maximum loading dose of TXA and whether its dose–response curve shows a plateau, which may help guide clinical use of TXA. Future studies should also investigate when it is best to initiate anti‐coagulation therapy in order to balance fibrinolysis and coagulation in their dynamic equilibrium. In our study, all patients received thromboprophylaxis 6–8 hours postoperatively, according to the recommendations of the Chinese Orthopedic Association.

5. CONCLUSION

TXA is effective and safe for decreasing blood loss and transfusion following primary THA, regardless of whether it is administered intravenously, topically or via both routes. Intravenous or combined administration may show better haemostatic efficacy than topical administration, as long as contraindications are not present.

COMPETING OF INTERESTS

There are no competing interests to declare.

CONTRIBUTORS

J.X.: data collection, data analysis, and writing the paper. S.Z.: data collection, writing the paper, and design of study. G.C.: data analysis, design of study, and writing the paper. H.X.: data collection, data analysis, and writing the paper. Z.Zh.: design of study and data analysis. F.P.: conception and design of study.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supporting information

Table S1 The hospitals of included patients

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank A. Chapin Rodríguez from Creaducate Enterprises Ltd. for providing language help and writing assistance. The research was supported by Post‐Doctor Research Project, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (2018HXBH073); National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Z2018B11) and the National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China program (201302007). We also thank all the 25 centres and 29 surgeons who participated in the program.

Xie J, Zhang S, Chen G, Xu H, Zhou Z, Pei F. Optimal route for administering tranexamic acid in primary unilateral total hip arthroplasty: Results from a multicenter cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:2089–2097. 10.1111/bcp.14018

The authors confirm that the principal investigator for this paper Fuxing Pei and that he had direct clinical responsibility for patients.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pivec R, Johnson AJ, Mears SC, Mont MA. Hip arthroplasty. Lancet. 2012;380(9855):1768‐1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780‐785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kehlet H. Fast‐track hip and knee arthroplasty. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1600‐1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hart A, Khalil JA, Carli A, Huk O, Zukor D, Antoniou J. Blood transfusion in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty: incidence, risk factors, and thirty‐day complication rates. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):1945‐1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harvey AR, Basavaraju SV, Chung KW, Kuehnert MJ. Transfusion‐related adverse reactions reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network Hemovigilance Module, United States, 2010 to 2012. Transfusion. 2015;55(4):709‐718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kozanek M, Menendez ME, Ring D. Association of perioperative blood transfusion and adverse events after operative treatment of proximal humerus fractures. Injury. 2015;46(2):270‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Van Bodegom‐Vos L, Voorn VM, So‐Osman C, et al. Cell salvage in hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(12):1012‐1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alsaleh K, Alotaibi GS, Almodaimegh HS, Aleem AA, Kouroukis CT. The use of preoperative erythropoiesis‐stimulating agents (ESAs) in patients who underwent knee or hip arthroplasty: a meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9):1463‐1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Voorn VM, van der Hout A, So‐Osman C, et al. Erythropoietin to reduce allogeneic red blood cell transfusion in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty. Vox Sang. 2016;111(3):219‐225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muñoz M, Páramo JA. Antifibrinolytic agents in current anaesthetic practice: use of tranexamic acid in lower limb arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112(4):766‐767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Longstaff C. Studies on the mechanisms of action of aprotinin and tranexamic acid as plasmin inhibitors and antifibrinolytic agents. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1994;5(4):537‐542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ. 2014;349:g4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Melvin JS, Stryker LS, Sierra RJ. Tranexamic acid in hip and knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(12):732‐740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Friedman RJ, Gordon E, Butler RB, Mock L, Dumas B. Tranexamic acid decreases blood loss after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(4):614‐618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goobie SM. Tranexamic acid: still far to go. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(3):293‐295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tuttle JR, Ritterman SA, Cassidy DB, Anazonwu WA, Froehlich JA, Rubin LE. Cost benefit analysis of topical tranexamic acid in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(8):1512‐1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wind TC, Barfield WR, Moskal JT. The effect of tranexamic acid on transfusion rate in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):387‐389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fillingham YA, Kayupov E, Plummer DR, Moric M, Gerlinger TL, Della Valle CJ. The James A. Rand Young Investigator's Award: a randomized controlled trial of oral and intravenous tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: the same efficacy at lower cost? J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(Suppl 9):26‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yi Z, Bin S, Jing Y, Zongke Z, Pengde K, Fuxing P. Tranexamic acid administration in primary total hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial of intravenous combined with topical versus single‐dose intravenous administration. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(12):983‐991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fillingham YA, Ramkumar DB, Jevsevar DS, et al. Tranexamic acid use in total joint arthroplasty: the clinical practice guidelines endorsed by the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Hip Society, and Knee Society. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3065‐3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen Y, Zhou Z, Pei F, et al. Expert consensus on the application of anti‐fibrinolytic drug sequential anticoagulant in perioperative period of hip and knee joint replacement in China. Chin J Bone Joint Surgery. 2015;8(4):281‐285. in Chinese [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xie J, Ma J, Yue C, Kang P, Pei F. Combined use of intravenous and topical tranexamic acid following cementless total hip arthroplasty: a randomised clinical trial. Hip Int. 2016;26(1):36‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benoni G, Björkman S, Fredin H. Application of pharmacokinetic data from healthy volunteers for the prediction of plasma concentrations of tranexamic acid ın surgical patients. Clin Drug Investig. 1995;10(5):280‐287. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gross JB. Estimating allowable blood loss: corrected for dilution. Anesthesiology. 1983;58(3):277‐280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nadler SB, Hidalgo JH, Bloch T. Prediction of blood volume in normal human adults. Surgery. 1962;51(2):224‐232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, et al. NC‐IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucl Acids Res. 2018;46:D1091‐D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goobie SM, Frank SM. Tranexamic acid: what is known and unknown, and where do we go from here? Anesthesiology. 2017;127(3):405‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang Y, Zhang L, Ma X, et al. What is the optimal approach for tranexamic acid application in patients with unilateral total hip arthroplasty? Orthopade. 2016;45(7):616‐621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. North WT, Mehran N, Davis JJ, Silverton CD, Weir RM, Laker MW. Topical vs intravenous tranexamic acid in primary total hip arthroplasty: a double‐blind, randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(5):1022‐1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nakura N, Hirakawa K, Takayanagi S, et al. Additional intraarticular tranexamic acid further reduced postoperative blood loss compared to intravenous and topical bathed tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective sequential series study. Transfusion. 2017;57(4):977‐984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xie J, Hu Q, Huang Z, Zhou Z, Pei F. Comparison of three routes of administration of tranexamic acid in primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty: analysis of a national database. Thromb Res. 2019;173:96‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raveendran R, Wong J. Tranexamic acid reduces blood transfusion in surgical patients while its effects on thromboembolic events and mortality are uncertain. Evid Based Med. 2013;18(2):65‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wong J, Abrishami A, El Beheiry H, et al. Topical application of tranexamic acid reduces postoperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(15):2503‐2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wei W, Wei B. Comparison of topical and intravenous tranexamic acid on blood loss and transfusion rates in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(11):2113‐2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McLean M, McCall K, Smith IDM, et al. Tranexamic acid toxicity in human periarticular tissues. Bone Joint Res. 2019;8(1):11‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Busse P, Vater C, Stiehler M, et al. Cytotoxicity of drugs injected into joints in orthopaedics. Bone Joint Res. 2019;8(2):41‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sabbag OD, Abdel MP, Amundson AW, Larson DR, Pagnano MW. Tranexamic acid was safe in arthroplasty patients with a history of venous thromboembolism: a matched outcome study. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9S):S246‐S250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Whiting DR, Gillette BP, Duncan C, Smith H, Pagnano MW, Sierra RJ. Preliminary results suggest tranexamic acid is safe and effective in arthroplasty patients with severe comorbidities. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(1):66‐72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 The hospitals of included patients

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.