Abstract

Neurotropic flavivirus Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) and West Nile virus (WNV) are amongst the leading causes of encephalitis. Using label-free quantitative proteomics, we identified proteins differentially expressed upon JEV (gp-3, RP9) or WNV (IS98) infection of human neuroblastoma cells. Data are available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD016805. Both viruses were associated with the up-regulation of immune response (IFIT1/3/5, ISG15, OAS, STAT1, IRF9) and the down-regulation of SSBP2 and PAM, involved in gene expression and in neuropeptide amidation respectively. Proteins associated to membranes, involved in extracellular matrix organization and collagen metabolism represented major clusters down-regulated by JEV and WNV. Moreover, transcription regulation and mRNA processing clusters were also heavily regulated by both viruses. The proteome of neuroblastoma cells infected by JEV or WNV was significantly modulated in the presence of mosquito saliva, but distinct patterns were associated to each virus. Mosquito saliva favored modulation of proteins associated with gene regulation in JEV infected neuroblastoma cells while modulation of proteins associated with protein maturation, signal transduction and ion transporters was found in WNV infected neuroblastoma cells.

Introduction

Arboviral diseases continue to represent a major burden for society, with both health and economic consequences. Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) and West Nile virus (WNV), two closely-related Flavivirus [1], are the most important cause of encephalitis amongst arboviruses, leading to large outbreaks in Asia for the former, and is the principal cause of epidemic encephalitis in the United States, for the latter [2]. Other mosquito-borne flaviviruses can also display neurotropic features such as dengue virus in rare cases, Saint-Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) or the recently emerged Zika virus as well as the tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBE) [3]. As recently highlighted in several studies, both JEV and WNV are presenting high risks of spillover in immunologically naive human populations: native mosquitoes from both Europe and Northern America have been shown to be competent vectors for JEV [4] [5] and WNV is currently spreading in the Eastern and Southern parts of Europe [6]. JEV and WNV are transmitted to vertebrate hosts such as birds (and domestic swine for JEV) by Culex mosquitoes in an enzootic cycle and humans (and horses) are considered dead-end hosts as they may develop symptomatic infection while they cannot transmit the disease [7].

During infection, viruses hijack various host cell pathways to promote their own replication and survival while cells activate various antiviral responses [8]. Hence, the resulting host-virus interactions determines the outcome of viral infection and disease progression [9]. Recent technological advances in proteomics have led to a better understanding of the complex nature of virus-host interactions through large-scale screening approaches, using so far mostly two-dimensional differential gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) and mass spectrometry (MS) [11–13]. Two proteomic studies performed in HeLa cells [10] or mouse brains and neuroblastoma cells [11] reported several confirmed hits and pathways as being modulated during JEV infection. However, none were consistently identified in both studies. One laboratory reported several confirmed hits and pathways modulated in WNV-infected Vero cells [12] and mouse brains [13] but none of them corroborated those found for JEV. In the first study using label-free MS, phosphorylation of the spliceosome, ErbB, MAPK, NF-κB and mTOR signaling pathways were found to be highly regulated during WNV infection of human glial U251 cells [14,15]. Yet, there is no proteomic study comparing the host response to JEV and WNV infection in an identical experimental model. The only large-scale screening providing a wide comparison between JEV and WNV infection was performed using microarrays and based on infected mouse brain [16,17]. Viral infection induced a modulation of the expression of genes associated with interferon signaling, the immune system, inflammation, cell death, survival, glutamate signaling and tRNA charging, the latter being specific to flaviviruses.

While most of the infections by neurotropic flaviviruses are asymptomatic or showing mild symptoms such as fever, headache or gastrointestinal symptoms, the most devastating outcome–encephalitis–occurs only in <1% of cases [14]. The question of JEV or WNV capacity to successfully infect the brain and induce acute encephalitis in humans remains to be clarified. To gain access to the central nervous system (CNS), most viruses have to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). In the case of neurotropic flaviviruses, the mechanisms involved are not completely understood yet [18], but disruption of the BBB appears to be a likely possibility [19]. Interestingly, studies have shown that mosquito saliva was discharged in the blood vessel [20] and therefore could potentially reach the BBB. Mosquito saliva has already been well-established as a potent enhancer of various arbovirus infections [21]. In the case of dengue virus, mosquito bite enhances viral pathogenesis [22] and mosquito saliva was suggested to favor keratinocyte infection and modify the host immune response [23,24]. Regarding neurotropic flaviviruses, the role of saliva was confirmed for WNV [23,24], not shown for SLEV [25,26] and remains to be established for JEV. WNV inoculation in mice after mosquito feeding led to a higher viremia and an accelerated neuroinvasion [24]. However, the role of saliva has been mostly studied on the site of infection or/and with a low quantity of saliva, mimicking a single mosquito bite event [27]. Spot feeding by uninfected mosquitoes prior to viral inoculation of mice has been shown to enhance WNV viremia in a dose-dependent manner [5]. Moreover, mice inoculated by infected mosquito bite had faster viral spread to peripheral and central nervous system tissues than mice inoculated by needle [5]. Yet in endemic areas individuals are regularly subjected to several mosquito bite events. Taken together, it is thus possible that in highly bitten individuals, saliva proteins may reach the BBB and CNS from the blood stream, independently or bound to the virus [5] and affect viral replication there.

In order to better understand the pathophysiological processes involved during neurotropic flavivirus infection, we compared the profiles of protein expression in JEV or WNV-infected human neuroblastoma cells using label-free quantification mass-spectrometry (MS). We identified numerous cellular factors up- or down-regulated during JEV or WNV infection. Interestingly, a consequent number of proteins was similarly regulated by both viruses. Finally, we investigated the potential role of mosquito saliva on neuroblastoma cell infection by both JEV and WNV. Surprisingly, we found a strong effect of mosquito saliva on the human neuroblastoma proteome for either infection, although neither JEV nor WNV replication was affected in the cells infected.

Methods

Mosquito rearing and salivary gland extraction

Colonies of Cx. pipiens, a competent vector for both JEV and WNV [5], were established from field isolates and reared as previously described [5]. Briefly, the eggs were hatched in tap water and the larvae were fed with brewer’s yeast tablets and cat food. Adults were maintained at 27°C, 80% relative humidity with continuous access to 10% sucrose solution and a light/dark cycle of 12 h/12 h.

Five days after hatching, female mosquitoes were anesthetized at 4°C. 100 salivary glands (SG) were dissected and placed in 100 μL of PBS 1X. Salivary glands extracts (SGE) were prepared by sonicating the SG (six times for 3 min each with a pulse ratio of 2 sec on / 2 sec off) and centrifuging the crude extract at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered on a 0,22 μm filter and transferred to clean tubes. Protein concentration was estimated with a Nanodrop (~0,75 mg/mL) and used as quality control before storage of SGE at −80°C.

Cell infection

Human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells were maintained at 37°C in DMEM with 10% FBS. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates with 5.105 cells/well (3 wells/condition) for 24h and infected with JEV genotype 3 strain RP-9 [5] or WNV strain IS98 [28] (produced on C6/36 cells) at a MOI of 1 in 1 mL of DMEM with 2% FBS, in presence or not of SGE (2 μL, equivalent of 2 SG). After 48h, the supernatant was removed from the 6-well plates.

For proteomic analysis, cells were resuspended in label free denaturation buffer (Tris 100mM pH8.0, urea 8M). Whole cell protein extract was obtained by sonication as described for the SGE. The supernatant was transferred to clean tubes, consistency between samples was confirmed by OD measurement with a Nanodrop and the samples were stored at -80°C. Each experiment was performed in biological triplicate.

For western blotting, cells were washed, scrapped in 1 mL of PBS, cells were centrifuged at 5000g and protein lysates were prepared by cell lysis in RIPA buffer (Bio Basic; catalog no. RB4476) containing protease inhibitors (Roche; catalog no. 11873580001).

In-solution digestion of protein extracts

Reduction of disulfide bonds was performed in 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 30 min at room temperature; alkylation was performed in 20 mM iodoacetamide in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. Each sample was first digested by 500 ng of LysC (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) at 30°C for 3 hours. Solution was diluted in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate (BA), until urea concentration was below 1.5 M. Each sample was then digested with 500 ng of trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) at 37°C overnight. Digestion was stopped by adding 1% formic acid (FA). Resulting peptides were purified using SPE C18 strategy and concentrated to almost dryness in 50% acetonitrile (ACN) 0.1% FA with a speedvac. Briefly, C18 phase (Sep-Pak, Waters) was activated in methanol, rinsed once in 80% ACN 0.1% FA, washed thrice in 0.1% FA. Resin was washed thrice in 0.1% FA, once in 2% ACN 0.1% FA. Peptides were eluted in 50% ACN 0.1% FA. Peptides in elution buffer were concentrated to almost dryness.

Mass spectrometry analysis, database search, and protein identification

Digested peptides were analyzed by nano LC-MS/MS using an EASY-nLC 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a Q Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer. About 1 μg of each sample (dissolved in 0.1% FA) was loaded and separated at 250 nl.min-1 on a home-made C18 50 cm capillary column picotip silica emitter tip (75 μm diameter filled with 1.9 μm Reprosil-Pur Basic C18-HD resin, (Dr. Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch-Entringen, Germany)) equilibrated in solvent A (0.1% FA). The peptides were eluted using a two slopes gradient of solvent B (0.1% FA in ACN) from 2% to 27% in 100 min and to 27% to 60% in 50 min at 250 nL/min flow rate (total length of the chromatographic run was 180 min). The Q Exactive (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen) was operated in data-dependent acquisition mode with the XCalibur software 2.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen). Survey scan MS were acquired in the Orbitrap on the 300–1700 m/z range with the resolution set to a value of 70 000 at m/z = 400 in profile mode (AGC target at 1E6). The 5 most intense ions per survey scan were selected for HCD fragmentation (NCE 27), and the resulting fragments were analyzed in the Orbitrap at 17500 of resolution (m/z 400). Isolation of parent ion was fixed at 1.6 m/z and underfill ratio at 1%. Dynamic exclusion was employed within 45 sec.

Data were searched with the Andromeda search engine using MaxQuant (1.4.1.2 version) against the Human database from SwissProt and TrEMBL (2014.01.14, 88500 entries including 39715 from SwissProt), structural polyproteins of JEV and WNV, and the Culex pipiens database (2014.12.12, 130 entries, from Uniprot).

The following search parameters were applied: Carbamidomethylation of cysteines was set as a fixed modification. Oxidation of methionine and protein N-terminal acetylation were set as variable modifications. The mass tolerances in MS and MS/MS were set to 5 ppm for each, respectively. Maximum peptide charge was set to 7 and 5 amino acids were required as minimum peptide length. Two peptides were required for protein identification and quantitation. Peptides and proteins identified with an FDR lower than 0.1% were considered as valid identification.

Label free analysis was done by using the 'match between run' feature of MaxQuant (3 min time window). LFQ data were used to performed statistical analysis between conditions of infection.

Statistical analysis of label free MS data

Statistical analysis of label free data was performed using the MS-Stat package on R environment [29]. Protein LFQ metrics were used for further statistical analysis. Proteins were declared significant with fold change higher than 1.5, and adjusted p-value below 5% of error.

Bioinformatic analysis

For bioinformatic analysis, MS hit list was curated and annotated with both UniProt IDs and Entrez GeneIDs.

Gene ontology (GO) and Functional annotation clustering analysis was performed using DAVID v6.8 [30,31]. The degree of common genes between annotations was measured using Kappa statistics with a similarity term overlap of 4 and a similarity threshold of 0.7. Group of similar annotations were classified based on Kappa values and according to the following parameters: initial group membership of 2, final group membership of 3 and a multiple linkage threshold of 0.3. Finally, an enrichment threshold of 1.0 was used.

The interaction network for proteins of interest was obtained by using STRING v10 [32]. High confidence interactions (minimum score: 0.7) were determined using the following four sources: text mining, experiments, databases or co-expression and the network was solidified adding up to five second shell interactors–proteins which were not identified but connect identified proteins. Finally, the network was visualized with Cytoscape [33].

Western blotting

Equal amounts of total proteins were loaded on a NuPAGE Novex 4 to 12% Bis-Tris protein gel (Life Technologies) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad; catalog no. 170–4156). After blocking the membrane for 2h at room temperature in PBS-Tween (PBS-T) plus 5% milk, the blot was incubated overnight at 4°C with recommended dilutions of the primary antibodies. The membrane was then washed in PBS-T and incubated for 2h at RT in the presence of HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. After washes in PBS-T, the membrane was incubated with the Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate (Thermo Scientific; catalog no. 32106) and protein bands were revealed using MyECL Imager machine (Thermofisher).

Antibodies

Monoclonal antibody 4G2 anti-Flavivirus E protein was purchased from RD Biotech (Besançon, France). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against IFIT3 (catalog no. GTX112442) and COL1A1 (catalog no. GTX112731) proteins were procured from GeneTex. Rabbit monoclonal antibody against PAM (catalog no. ab109175) and SSBP2 (catalog no. ab177944) were purchased from Abcam. Mice monoclonal antibody against actin beta was purchased from Thermo-Fischer (catalog no. MA1-140).

Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were obtained from Bio-Rad Laboratories (catalog no. 170–6516 and 170–6515, respectively).

Results

Identification of differentially expressed proteins following JEV or WNV infection

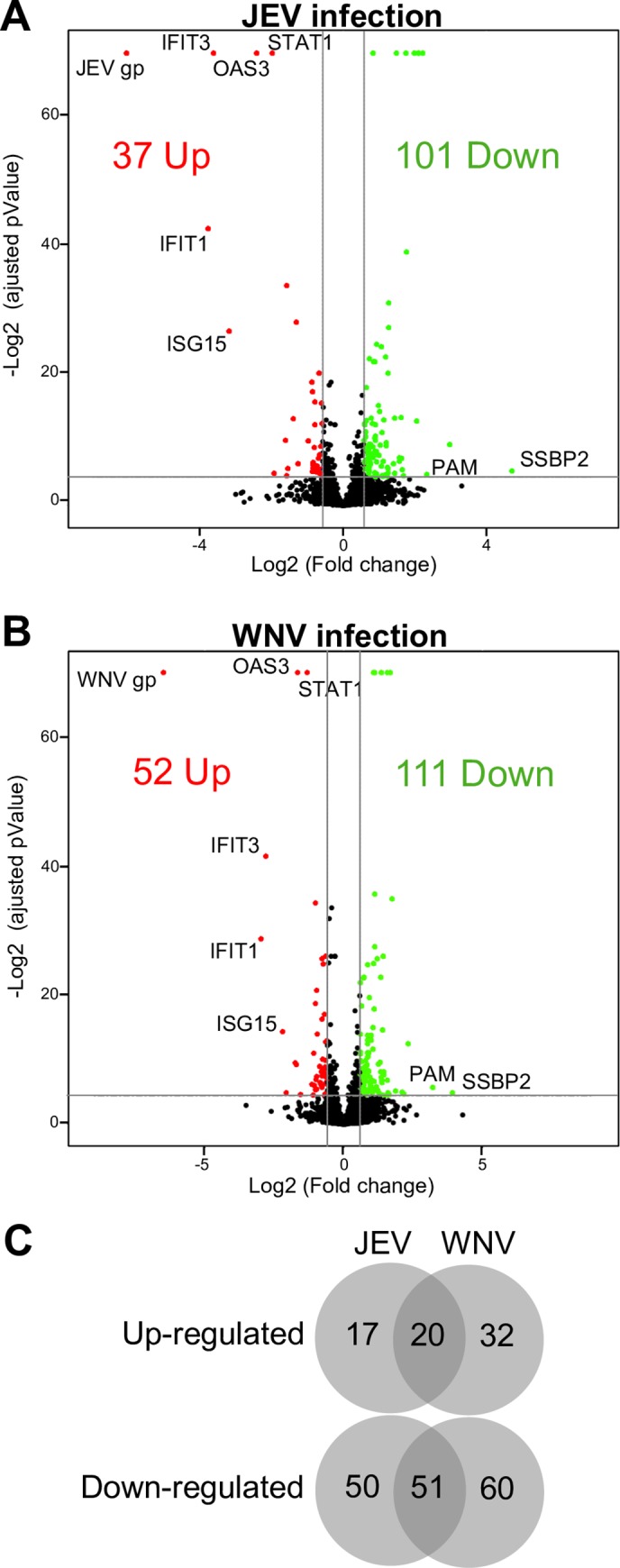

In order to study the host proteome during neurotropic flavivirus infection in a human neuron model, SK-N-SH cells were infected with either JEV (genotype 3, strain RP-9) or WNV (strain IS-98) and, after 48h, proteins from whole-cell extracts were identified and quantified by label-free quantification mass spectrometry. Using the MaxQuant suite, a total of 3907 proteins were identified in all conditions (Mock, JEV- and WNV- infected cells). The genomic polyprotein of JEV and WNV were highly detected in the infected cells, confirming an efficient infection of the cells by both viruses (S2 Fig). Amongst the identified host proteins, a strong perturbation of the proteome was observed in response to both JEV and WNV infection (Fig 1).

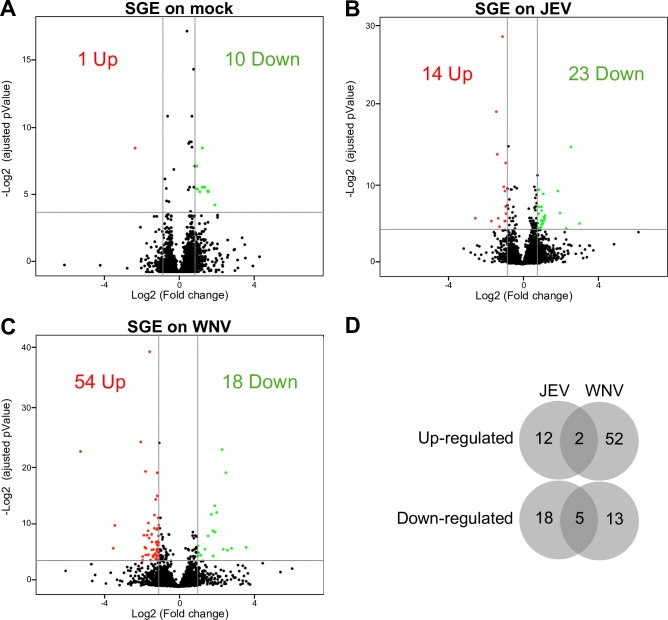

Fig 1. Comparison of human neuroblastoma proteome modulation during JEV or WNV infection.

A-B. Volcano plots of protein expression in non-infected vs infected cells. SK-N-SH cells were infected for 48h with either JEV (A) or WNV (B) and proteins were extracted for label free quantitation by mass spectrometry. The results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Each spot represents a protein identified (black) and significantly down-regulated (green) or up-regulated (red) during viral infection. C. Venn diagram of the proteins up- and down-regulated in JEV (A) and WNV (B) infected cells.

In the case of JEV, the expression of 37 cellular proteins is up-regulated after 48h of infection (S1 Table) and that of 101 is down-regulated (S2 Table). Regarding WNV, the expression of 52 proteins is up-regulated (Table 1) and that of 111 is down-regulated (Table 2). While the median fold change (FC) is 1.8 for all conditions, the most up-regulated host proteins (Table 1) have a FC of 13.6 and 7.8, and the most down-regulated host proteins (Table 2) have a FC of 26 and 15 for JEV and WNV, respectively.

Table 1. Top 10 up-regulated proteins during JEV and/or WNV infection.

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in the JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells compared to the Mock. For complete list, see S1 Table.

| Effect | Uniprot # | GeneID # | Gene symbol | Name | Clusters | JEV/Mock FC (pValue) | WNV/Mock FC (pValue) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated during JEV infection | P32886 | 1489713 | N/A | JEV genomic polyprotein | 65.95 (0.00E+00) | ||

| Q5EBM0-4 | 129607 | CMPK2 | UMP-CMP kinase 2, mitochondrial | Nucleotide-binding | 3.82 (3.25E-02) | ||

| O60664 | 10226 | PLIN3 | Perilipin-3 | Cell-cell adhesion | 1.82 (1.81E-06) | ||

| P11047 | 3915 | LAMC1 | Laminin subunit gamma-1 | Collagen metabolism, EGF-like domain, Extracellular matrix org., Glycoprotein | 1.80 (5.28E-06) | ||

| Q9BXJ9 | 80155 | NAA15 | N-alpha-acetyltransferase 15, NatA auxiliary subunit | Tetratricopeptide repeat, Transcription regulation | 1.78 (1.80E-02) | ||

| O00622 | 3491 | CYR61 | Protein CYR61 | Glycoprotein, Nucleotide-binding | 1.76 (1.82E-02) | ||

| Q9Y520-4 | 23215 | PRRC2C | Protein PRRC2C | 1.76 (1.16E-02) | |||

| Q9Y3Z3 | 25939 | SAMHD1 | Deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase SAMHD1 | Innate immunity | 1.74 (1.58E-05) | ||

| F8VVL1 | 8562 | DENR | Density-regulated protein | 1.66 (2.90E-02) | |||

| Q9UNF0-2 | 11252 | PACSIN2 | Protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neurons protein 2 | Cell-cell adhesion | 1.66 (2.26E-02) | ||

| Up-regulated during both JEV and WNV infection | P09914 | 3434 | IFIT1 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 | Innate immunity, Tetratricopeptide repeat | 13.60 (1.34E-13) | 7.838 (2.36E-09) |

| O14879 | 3437 | IFIT3 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 | Innate immunity, Tetratricopeptide repeat | 12.31 (0.00E+00) | 6.944 (3.20E-13) | |

| P05161 | 9636 | ISG15 | Ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 | Anchored protein, Innate immunity | 9.08 (7.93E-09) | 4.59 (4.85E-05) | |

| Q9Y6K5 | 4940 | OAS3 | 2'-5'-oligoadenylate synthase 3 | Innate immunity, Nucleotide-binding, Transmembrane protein | 5.32 (0.00E+00) | 3.17 (0.00E+00) | |

| P42224 | 6772 | STAT1 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1-alpha/beta | Cell-cell adhesion, Innate immunity, Transcription regulation | 3.96 (0.00E+00) | 2.49 (0.00E+00) | |

| Q9BQE5 | 23780 | APOL2 | Apolipoprotein L2 | Transmembrane protein | 3.04 (9.67E-04) | 2.13 (4.43E-02) | |

| Q13325 | 24138 | IFIT5 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 5 | Innate immunity, Tetratricopeptide repeat, Transmembrane protein | 2.98 (5.96E-11) | 1.93 (6.50E-05) | |

| Q8WUP2-3 | 54751 | FBLIM1 | Filamin-binding LIM protein 1 | 2.96 (4.13E-02) | 2.94 (4.26E-02) | ||

| Q5K651 | 54809 | SAMD9 | Sterile alpha motif domain-containing protein 9 | 2.61 (9.24E-05) | 2.11 (4.97E-04) | ||

| Q9NUQ6-2 | 26010 | SPATS2L | SPATS2-like protein | 2.47 (2.95E-09) | 2.02 (2.37E-06) | ||

| Up-regulated during WNV infection | P06935 | 912267 | N/A | WNV genomic polyprotein | 271.78 (3.88E-04) | ||

| Q6GMV3 | 391356 | PTRHD1 | Putative peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase PTRHD1 | 4.22 (3.58E-02) | |||

| Q5QNY5 | 5824 | PEX19 | Peroxisomal biogenesis factor 19 | Transmembrane | 3.35 (1.43E-03) | ||

| Q96C90 | 26472 | PP1R14B | Protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 14B | 2.21 (1.43E-02) | |||

| P0DMV8/9 | 3303 | HSPA1A | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1A | Cell-cell adhesion, Nucleotide-binding | 2.03 (4.86E-11) | ||

| Q9Y6G9 | 51143 | YNC1LI1 | Cytoplasmic dynein 1 light intermediate chain 1 | Nucleotide-binding | 2.01 (2.58E-02) | ||

| Q8TDX7 | 140609 | NEK7 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase Nek7 | Kinase, Nucleotide-binding | 1.99 (8.66E-03) | ||

| Q9BUF5 | 84617 | TUBB6 | Tubulin beta-6 chain | Nucleotide-binding | 1.96 (2.40E-02) | ||

| O95817 | 9531 | BAG3 | BAG family molecular chaperone regulator 3 | Cell-cell adhesion | 1.96 (6.14E-03) | ||

| O00592-2 | 5420 | PODXL | Podocalyxin | Glycoprotein, Transmembrane | 1.77 (1.43E-02) | ||

Table 2. Top 10 down-regulated proteins during JEV and/or WNV infection.

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in the JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells compared to the Mock. For complete list, see S2 Table.

| Effect | Uniprot # | GeneID # | Gene symbol | Name | Clusters | JEV/Mock FC (pValue) | WNV/Mock FC (pValue) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down-regulated during JEV infection | Q99797 | 4285 | MIPEP | Mitochondrial intermediate peptidase | Metalloprotease | 7.84 (1.53E-03) | |

| P21810 | 633 | BGN | Biglycan | Extracellular matrix org., Glycoprotein, Leucine-rich repeat | 3.21 (4.36E-02) | ||

| Q8WZ42-5 | 7273 | TTN | Titin | Immunoglobulin domain, Nucleotide-binding, Tetratricopeptide repeat | 3.12 (2.25E-02) | ||

| O14657 | 27348 | TOR1B | Torsin-1B | Glycoprotein, Nucleotide-binding | 3.09 (6.62E-03) | ||

| P55083 | 4239 | MFAP4 | Microfibril-associated glycoprotein 4 | Extracellular matrix org., Glycoprotein | 2.95 (6.07E-03) | ||

| O75063 | 9917 | FAM20B | Glycosaminoglycan xylosylkinase | Glycoprotein, Nucleotide-binding, Transmembrane protein | 2.70 (3.24E-02) | ||

| Q9P032 | 29078 | NDUFAF4 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex assembly factor 4 | 2.37 (2.00E-02) | |||

| Q13641 | 7162 | TPBG | Trophoblast glycoprotein | Glycoprotein, Leucine-rich repeat, Transmembrane protein | 2.36 (4.55E-02) | ||

| Q86UV5-2 | 84196 | USP48 | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 48 | 2.24 (3.92E-02) | |||

| P63218 | 2787 | GNG5 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(I)/G(S)/G(O) subunit gamma-5 | Anchored protein, Collagen metabolism | 2.22 (4.35E-02) | ||

| Down-regulated during both JEV and WNV infection | P81877-2 | 23635 | SSBP2 | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein 2 | 26.22 (2.60E-02) | 15,05 (3.46E-02) | |

| P19021-2 | 5066 | PAM | Peptidyl-glycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase | Glycoprotein, Transmembrane protein | 5.05 (3.74E-02) | 9,23 (2.02E-02) | |

| P02452 | 1277 | COL1A1 | Collagen alpha-1(I) chain | Extracellular matrix org., Collagen metabolism, Glycoprotein, Transmembrane protein | 4.65 (0.00E+00) | 2,96 (0.00E+00) | |

| P08123 | 1278 | COL1A2 | Collagen alpha-2(I) chain | Extracellular matrix org., Collagen metabolism, Glycoprotein | 4.29 (0.00E+00) | 2,16 (5.21E-09) | |

| P02461 | 1281 | COL3A1 | Collagen alpha-1(III) chain | Extracellular matrix org., Collagen metabolism, Glycoprotein | 4.28 (0.00E+00) | 2,16 (1.89E-11) | |

| Q9H3M7 | 10628 | TXNIP | Thioredoxin-interacting protein | Transcription regulation | 4.13 (1.20E-04) | 4,98 (1.82E-04) | |

| Q96CG8 | 115908 | CTHRC1 | Collagen triple helix repeat-containing protein 1 | Extracellular matrix org., Collagen metabolism, Glycoprotein | 3.98 (0.00E+00) | 2,54 (0.00E+00) | |

| O95864 | 9415 | FADS2 | Fatty acid desaturase 2 | Transmembrane protein | 3.41 (1.60E-12) | 3,36 (3.20E-11) | |

| Q15113 | 5118 | PCOLCE | Procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer 1 | Extracellular matrix org., Collagen metabolism, Glycoprotein | 3.35 (0.00E+00) | 1,81 (3.60E-08) | |

| C9JEZ4 | 10602 | CDC42EP3 | Cdc42 effector protein 3 | Transmembrane protein | 3.09 (8.20E-05) | 2,26 (1.88E-02) | |

| Down-regulated during WNV infection | P33908 | 4121 | MAN1A1 | Mannosyl-oligosaccharide 1,2-alpha-mannosidase IA | Glycoprotein, Transmembrane | 4.52 (4.01E-02) | |

| B4DWB0 | 80224 | NUBPL | Iron-sulfur protein NUBPL | Glycoprotein, Nucleotide-binding | 4.30 (3.39E-02) | ||

| Q8N129 | 245812 | CNPY4 | Protein canopy homolog 4 | Glycoprotein | 3.65 (2.81E-02) | ||

| H3BQR0 | 10073 | SNUPN | Snurportin-1 | 3.10 (4.33E-02) | |||

| Q16706 | 4124 | MAN2A1 | Alpha-mannosidase 2 | Glycoprotein, Transmembrane | 2.98 (3.58E-02) | ||

| Q9Y294 | 25842 | ASF1A | Histone chaperone ASF1A | Transcription regulation | 2.93 (4.58E-02) | ||

| Q9NRX1 | 56902 | PNO1 | RNA-binding protein PNO1 | 2.70 (4.97E-03) | |||

| P07711 | 1514 | CTSL | Cathepsin L1 | Collagen metabolism, Glycoprotein, Lysosome | 2.63 (4.66E-02) | ||

| P38571-2 | 3988 | LIPA | Lysosomal acid lipase/cholesteryl ester hydrolase | Glycoprotein, Lysosome | 2.58 (1.19E-02) | ||

| O00754-2 | 4125 | MAN2B1 | Lysosomal alpha-mannosidase | Glycoprotein, Lysosome | 2.53 (6.58E-03) |

Interestingly, the expression of 20 proteins is consistently up-regulated during infection by JEV and WNV (Fig 1C), including innate immunity-related proteins such as IFIT-1, IFIT-3, ISG15, OAS and STAT1 which are amongst the most up-regulated proteins for both JEV and WNV (FC ranging from 2.9 to 13.6 for JEV and from 1.9 to 7.8 for WNV, Table 1). Conversely, 51 proteins are consistently down-regulated by both JEV and WNV (Fig 1C), of which proteins related to collagen metabolism were the most prominent (11 out of 51, S2 Table). Further, two common proteins between JEV and WNV were amongst the most down-regulated ones: SSBP2 (Single-stranded DNA-binding protein 2) and PAM (Peptidyl-glycine α-amidating monooxygenase). SSBP2 was also the protein most down-regulated by both viruses (FC of 26 and 15, respectively) (Table 2).

Global host proteome response to JEV or WNV infection

Functionally related groups of proteins regulated during JEV or WNV neuroblastoma cell infection were identified using DAVID functional annotation clustering tool (Figs 2A and 3A and S3 and S4 Tables). About 72% of the proteins modulated during JEV infection were assigned to 16 functional groups (Fig 2A) and 78% of the proteins modulated during WNV infection were assigned to 13 functional groups (Fig 3A). Protein-protein interaction networks were also established using STRING, highlighting interactions within 32% and 45% of the proteins modulated during JEV (Fig 2B) or WNV (Fig 3B) infection, respectively.

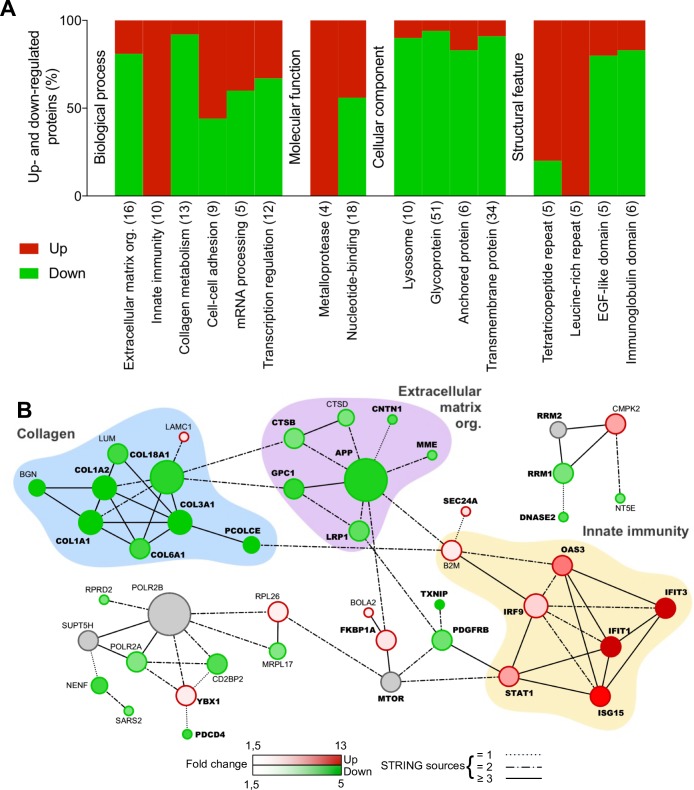

Fig 2. Functional clustering and network analysis of proteins modulated during JEV infection.

A. Percentage of proteins up(red)- and down(green)-regulated in functional groups. Modulated proteins were clustered into functional groups using DAVID v6.8 (detailed in S1 Fig). Functional groups are organized in four domains: Biological process, Molecular function, Cellular component or Structural feature and according to their enrichment score from the left to the right. Total number of proteins associated to each group is noted between brackets. B. Networks of up(red)- and down(green)-regulated proteins. Protein-protein interactions (PPI) networks were determined with STRING v10 and visualized with Cytoscape. Proteins regulated in common with WNV are highlighted in bold. Node size is relative to the number of edges. Grey nodes correspond to second shell proteins linking identified proteins. Edges are determined according to the number of sources (text mining, experiments, databases or co-expression) supporting the link between proteins.

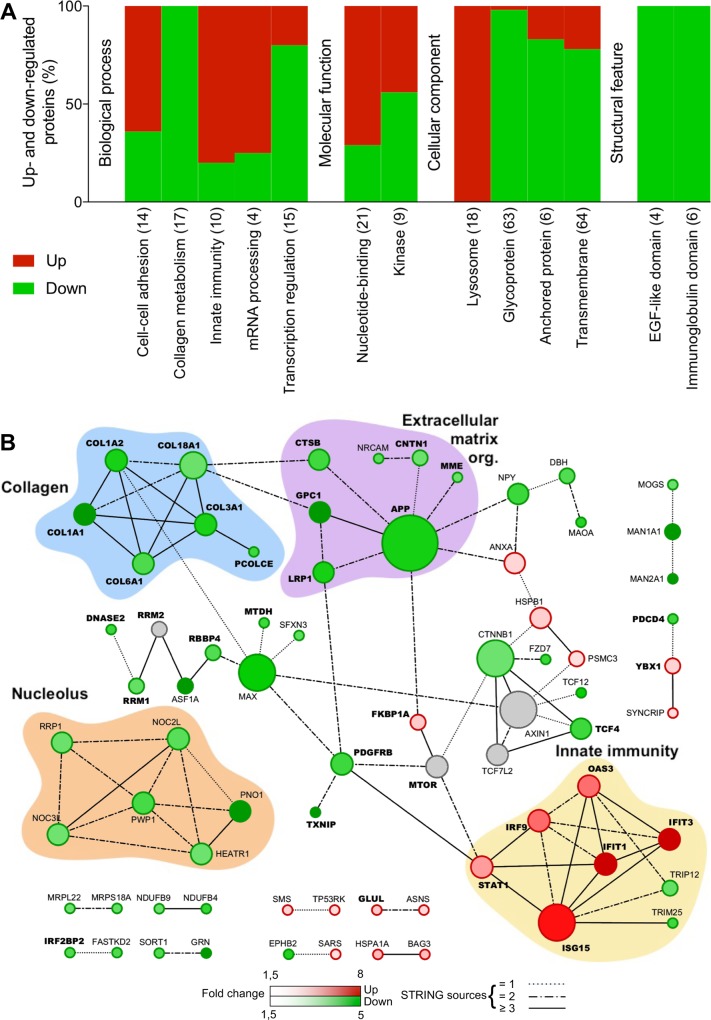

Fig 3. Functional clustering and network analysis of proteins modulated during WNV infection.

A. Percentage of proteins up(red)- and down(green)-regulated in functional groups. Modulated proteins were clustered into functional groups using DAVID (detailed in S2 Table). Functional groups are organized in four domains: Biological process, Molecular function, Cellular component or Structural feature and according to their enrichment score from left to right. Total number of proteins associated to each group is noted between brackets. B. Networks of up(red)- and down(green)-regulated proteins. PPI networks were determined with STRING and visualized with Cytoscape. Proteins regulated in common with JEV are highlighted in bold. Node size is relative to the number of edges. Grey nodes correspond to second shell proteins linking identified proteins. Edges are determined according to the number of sources (text mining, experiments, databases or co-expression) supporting the link between proteins.

In response to JEV infection, a functional cluster of 10 proteins involved in immunity was strictly up-regulated (FC from 13.6 to 1.7): IFIT1, IFIT3, ISG15, OAS3, STAT1, IFIT5, IRF9, SAMHD1, B2M, ZC3HAV1 (Fig 2A, Table 1 and S1 Table) of which 7 proteins also formed a cluster of interacting proteins: IFIT1, IFIT3, ISG15, OAS3, STAT1, IRF9 and B2M (Fig 2B). The tetratricopeptide repeat cluster (including proteins from the IFIT family) was the only other cluster substantially up-regulated (4/5). Conversely, clusters of proteins part of the extracellular matrix organization (13/16) and related collagen metabolism (12/13) were the most down-regulated biological processes (Fig 2A). Both functional annotation clusters were also confirmed in the network analysis (Fig 2B). About half of the down-regulated proteins are glycoproteins (48/101) and one third are transmembrane or anchored proteins (36/101) while they are under-represented amongst up-regulated proteins (Fig 2A). A cluster of proteins associated to the lysosomes was down-regulated (9/10) and several metalloproteases or proteins featuring leucine-rich repeats, EGF-like domains or immunoglobulin domains were also mostly down-regulated (Fig 2A). Finally, mRNA processing and transcription regulation clusters and the nucleotide-binding cluster were either up- or down-regulated during JEV infection (Fig 2A). Fig 2B highlights a small group of proteins modulated during JEV infection involved in transcription regulation and mRNA processing (RPRD2, POLR2A, YBX1, CD2BP2) and revolving around subunits of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II.

In response to WNV infection, similar clusters and networks of modulated proteins were observed (Fig 3). Proteins involved in immune response such as IFIT1, IFIT3, ISG15, OAS3, STAT1, IFIT5 or IRF9 were also up-regulated together with ANXA1 (Table 1). However, two proteins, ERAP2 involved in antigen processing and TRIM25 involved in IFN triggering, were both down-regulated (Fig 3, Table 2). The down-regulation of extracellular matrix organization was only identified using network analysis (Fig 3B), and while not being a key characteristic as for JEV infection (Fig 2), it remains an important feature of WNV infection. Moreover, the cluster of 17 proteins involved in collagen metabolism was also strictly down-regulated (Fig 3A) while 9/14 proteins involved in cell-cell adhesion were down-regulated during WNV infection. About half of the down-regulated proteins were glycoproteins (62/111) and anchored or transmembrane proteins (56/111) while they were under-represented amongst up-regulated proteins (Fig 3A). A cluster of 18 proteins associated to lysosomes was strictly down-regulated and several proteins featuring EGF-like domains or immunoglobulin domains were also mostly down-regulated while a cluster of 9 protein kinases was either up- or down-regulated (Fig 3A). Finally, mRNA processing (3/4) and nucleotide-binding (15/21) clusters were noticeably up-regulated during WNV infection (Fig 3A) which can be correlated to a network of down-regulated proteins linked to the nucleolus (Fig 3B), while conversely transcription regulation cluster was substantially up-regulated (12/15).

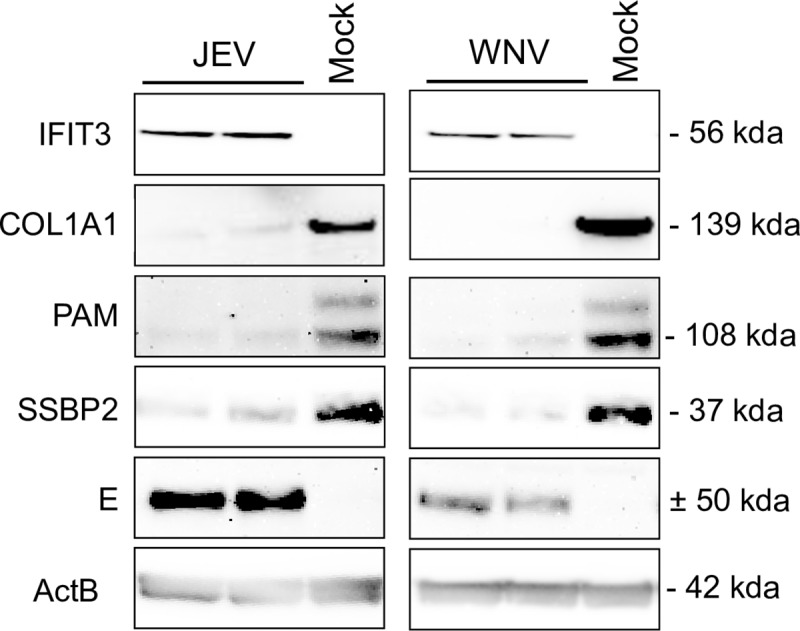

Overall, functional annotation clustering and protein-protein interaction networks show strong similarities between JEV and WNV infection of neuroblastoma cells. In order to confirm our findings, we further selected two hits representative of two of the most important clusters: IFIT3 for the innate immunity and COL1A1 for collagen organization, as well as the two hits associated with the strongest downregulation: SSBP2 and PAM (Fig 4). As expected, IFIT3 was expressed in response to JEV or WNV infection while COL1A1, SSPB2 and PAM expression was greatly reduced. It is worth noting that no cytopathic effect was observed despite the reduction of collagen expression (data not shown).

Fig 4. JEV and WNV inhibit collagen, PAM and SSBP2 expression in a neuron model.

SK-N-SH cells were infected with JEV or WNV at a MOI of 1 and proteins were extracted for western blot analysis 48hpi. Two independent experiments are displayed on the blot.

Role of mosquito saliva in a neuron model of infection

As saliva from mosquitoes is known to enhance Flavivirus infection [19,20], including WNV [21,23], we tested its potential effect on human neuroblastoma cell infection by JEV or WNV and on the proteome of the infected cells. For this purpose, we infected SK-N-SH cells with JEV or WNV in the presence of mosquito salivary gland extracts (SGE) and, after 48h, proteins from whole-cell extracts were identified and quantified by label-free quantification mass spectrometry. We identified only one Cx pipiens protein in our samples among the 130 referenced in our MS data bank (Q15G69, ß-tubulin). No effect of SGE on viral replication could be detected as shown by viral titration and genomic polyprotein quantification (S2 Fig).

In the absence of virus, mosquito SGE had little effect on the cells (Fig 5A). We observed only one up-regulated protein, ZRANB2 (FC of 3.0), a zinc-finger protein involved in RNA splicing, and 10 down-regulated proteins with a FC ranging from 1.51 to 2.45 (Table 3). Notably, out of all down-regulated proteins, 4 were involved in nuclear transport. On the other hand, mosquito SGE had a substantially stronger effect on the proteome of JEV (Fig 5B) or WNV (Fig 5C) infected cells. Interestingly, only a few proteins were similarly regulated for the 2 viruses: 2 up-regulated proteins, OSBPL8, a lipid transporter and HIST1H1B, a histone protein (Table 4) and 5 down-regulated proteins (Table 5), S100A6, a calcium sensor, NACA and EIF4H, two translation co-factors, COPS8, a component of the signalosome complex and LGALS1, a lectin.

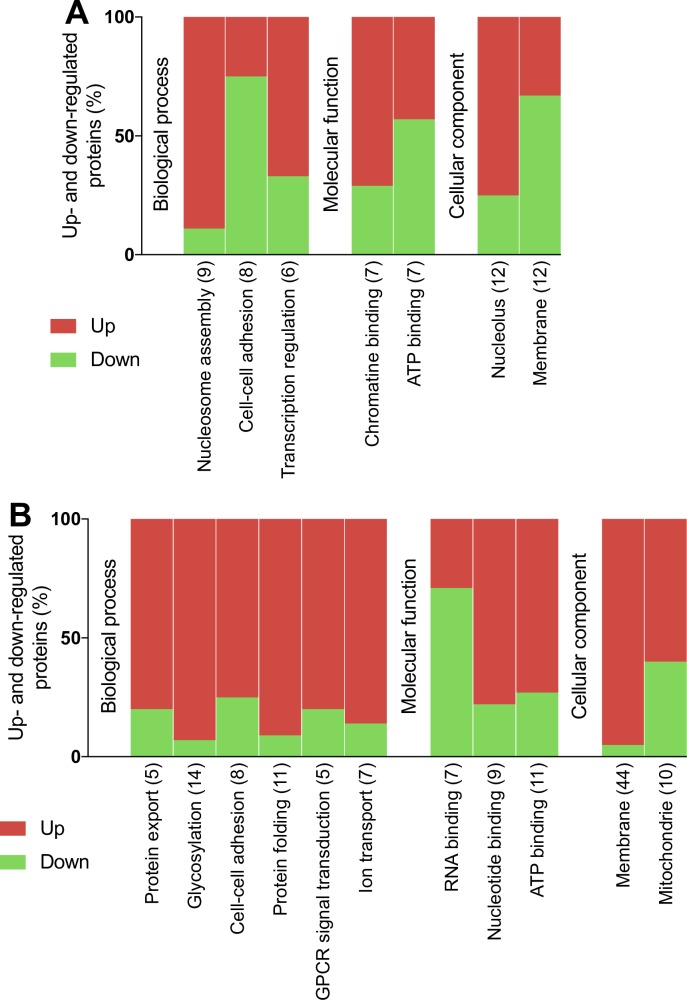

Fig 5. Comparison of modulation of the human neuroblastoma proteome during JEV or WNV infection in the presence of mosquito SGE.

Volcano plots of protein expression in non-infected vs infected cells. After 48h, proteins from mock (A), JEV (B) or WNV (C) infected SK-N-SH cells were extracted for label free quantification by mass spectrometry. The results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Each spot represents a protein identified (black) and significantly down-regulated (blue) or up-regulated (red) during viral infection.

Table 3. Effect of SGE on non infected human neuroblastoma cells.

| Effect | Uniprot # | GeneID # | Gene symbol | Name | Fold change (adjusted pValue) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated in presence of SGE | O95218-2 | 9406 | ZRANB2 | zinc finger RANBP2-type containing 2 | 3.04 (2,33E-03) | ||

| Down-regulated in presence of SGE | Q5QNY5 | 5824 | PEX19 | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 19 | 2.45 (3,45E-02) | ||

| E9PJ95 | 29099 | COMMD9 | COMM domain containing 9 | 2.08 (1,87E-02) | |||

| E7EQI7 | 9897 | KIAA0196 | KIAA0196 | 2.04 (1,77E-02) | |||

| Q9NRG7-2 | 56948 | SDR39U1 | short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 39U member 1 | 1.91 (1,49E-02) | |||

| Q66K74 | 55201 | MAP1S | microtubule associated protein 1S | 1.79 (1,49E-02) | |||

| O43592 | 11260 | XPOT | exportin for tRNA | 1.79 (2,33E-03) | * | ||

| Q9BZH6 | 55717 | WDR11 | WD repeat domain 11 | 1.68 (1,87E-02) | * | ||

| O60443 | 1687 | DFNA5 | deafness associated tumor suppressor | 1.58 (1,65E-02) | |||

| Q9HAV4 | 57510 | XPO5 | exportin 5 | 1.56 (5,53E-03) | * | ||

| O95373 | 10527 | IPO7 | importin 7 | 1.51 (1,58E-02) | * | ||

| * involved in nuclear transport | |||||||

Table 4. Top 10 proteins up-regulated by SGE in JEV and/or WNV infected cells.

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in the JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells treated or not with SGE. For complete list, see S5 Table.

| Effect | Protein # | Gene ID # | Gene | Gene name | JEV infected FC (adj. pValue) | WNV infected FC (adj. pValue) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated proteins during JEV infection | Q15388 | 9804 | TOMM20 | translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 | 3.52 (1,94E-02) | |

| P16403 | 3006 | HIST1H1C | histone cluster 1 H1 family member c | 2.28 (2,48E-02) | ||

| P07305 | 3005 | H1F0 | H1 histone family member 0 | 1.96 (7,76E-05) | ||

| P53999 | 10923 | SUB1 | SUB1 homolog transcriptional regulator | 1.92 (1,93E-02) | ||

| Q5TAQ0 | 84300 | UQCC2 | ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase complex assembly factor 2 | 1.85 (4,01E-02) | ||

| Q9NR30 | 9188 | DDX21 | DExD-box helicase 21 | 1.70 (3,02E-09) | ||

| P11387 | 7150 | TOP1 | topoisomerase DNA I | 1.64 (1,27E-03) | ||

| O15446 | 10849 | CD3EAP | CD3e molecule associated protein | 1.60 (2,48E-02) | ||

| Q9UIG0-2 | 9031 | BAZ1B | bromodomain adjacent to zinc finger domain 1B | 1.59 (1,85E-03) | ||

| P11388 | 7153 | TOP2A | topoisomerase DNA II alpha | 1.57 (2,48E-02) | ||

| Up-regulated proteins during JEV and WNV infection | Q9BZF1-3 | 114882 | OSBPL8 | oxysterol binding protein like 8 | 1.57 (1,65E-04) | 1.55 (2,83E-05) |

| P16401 | 3009 | HIST1H1B | histone cluster 1 H1 family member b | 2.01 (1,98E-06) | 1.50 (2,85E-03) | |

| Up-regulated proteins during WNV infection | P60468 | 10952 | SEC61B | Sec61 translocon beta subunit | 7.71 (1,61E-07) | |

| H0YI58 | 51290 | ERGIC2 | ERGIC and golgi 2 | 3.90 (1,23E-02) | ||

| Q9P0L0 | 9218 | VAPA | VAMP associated protein A | 3.78 (8,72E-04) | ||

| P07099 | 2052 | EPHX1 | epoxide hydrolase 1 | 2.18 (5,44E-08) | ||

| O15427 | 9123 | SLC16A3 | solute carrier family 16 member 3 | 2.10 (4,83E-02) | ||

| Q13619 | 8451 | CUL4A | cullin 4A | 2.09 (3,11E-02) | ||

| O00264 | 10857 | PGRMC1 | progesterone receptor membrane component 1 | 2.04 (2,72E-03) | ||

| Q9BT22 | 56052 | ALG1 | ALG1, chitobiosyldiphosphodolichol beta-mannosyltransferase | 2.01 (1,08E-02) | ||

| P04844 | 6185 | RPN2 | ribophorin II | 1.98 (1,66E-06) | ||

| Q9HC07 | 55858 | TMEM165 | transmembrane protein 165 | 1.97 (2,59E-02) | ||

Table 5. Top 10 proteins down-regulated by SGE in JEV and/or WNV infected cells.

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in the JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells treated or not with SGE. For complete list, see S6 Table.

| Effect | Uniprot # | GeneID # | Gene symbol | Name | JEV infected FC (adj. pValue) | WNV infected FC (adj. pValue) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down-regulated proteins during JEV infection | Q99797 | 4285 | MIPEP | mitochondrial intermediate peptidase | 4.61 (3,06E-02) | |

| Q9Y6W5-2 | 10163 | WASF2 | WAS protein family member 2 | 3.67 (4,08E-05) | ||

| E7ESU0 | 10869 | USP19 | ubiquitin specific peptidase 19 | 3.24 (4,61E-02) | ||

| Q9BZX2 | 7371 | UCK2 | uridine-cytidine kinase 2 | 2.58 (1,85E-03) | ||

| O95400 | 10421 | CD2BP2 | CD2 cytoplasmic tail binding protein 2 | 1.82 (1,53E-02) | ||

| P00338 | 3939 | LDHA | lactate dehydrogenase A | 1.77 (2,33E-02) | ||

| Q9Y316 | 51072 | MEMO1 | mediator of cell motility 1 | 1.75 (2,34E-03) | ||

| Q9H3M7 | 10628 | TXNIP | thioredoxin interacting protein | 1.74 (3,06E-02) | ||

| Q9NRG7-2 | 56948 | SDR39U1 | short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 39U member 1 | 1.69 (2,48E-02) | ||

| Q9NPQ8-4 | 60626 | RIC8A | RIC8 guanine nucleotide exchange factor A | 1.66 (3,29E-02) | ||

| Down-regulated proteins during JEV and WNV infection | R4GN98 | 6277 | S100A6 | S100 calcium binding protein A6 | 2.73 (1,22E-02) | 2.78 (1,49E-02) |

| F8VZJ2 | 4666 | NACA | nascent polypeptide-associated complex alpha subunit | 1.80 (1,94E-02) | 2.15 (1,88E-03) | |

| Q15056-2 | 7458 | EIF4H | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4H | 1.78 (1,80E-02) | 2.05 (1,60E-03) | |

| E9PGT6 | 10920 | COPS8 | COP9 signalosome subunit 8 | 1.67 (9,82E-03) | 2.22 (1,93E-04) | |

| P09382 | 3956 | LGALS1 | galectin 1 | 1.66 (7,22E-03) | 1.98 (2,36E-04) | |

| Down-regulated proteins during WNV infection | Q9P0S9 | 51522 | TMEM14C | transmembrane protein 14C | 4.12 (1,10E-02) | |

| Q9NRX1 | 56902 | PNO1 | partner of NOB1 homolog | 3.03 (1,23E-02) | ||

| P61758 | 7411 | VBP1 | VHL binding protein 1 | 2.69 (1,93E-06) | ||

| P49366 | 1725 | DHPS | deoxyhypusine synthase | 2.56 (1,36E-02) | ||

| Q99497 | 11315 | PARK7 | Parkinsonism associated deglycase | 2.49 (1,32E-07) | ||

| Q04837 | 6742 | SSBP1 | single stranded DNA binding protein 1 | 2.14 (8,85E-05) | ||

| O00499-9 | 274 | BIN1 | bridging integrator 1 | 2.06 (2,90E-02) | ||

| O00743 | 5537 | PPP6C | protein phosphatase 6 catalytic subunit | 1.85 (2,85E-03) | ||

| Q9Y3B8 | 25996 | REXO2 | RNA exonuclease 2 | 1.73 (1,36E-02) | ||

| P46777 | 6125 | RPL5 | ribosomal protein L5 | 1.60 (2,73E-02) |

When comparing JEV infected cells in presence or not of mosquito SGE (Fig 5B), we found that SGE induced a change in protein expression: either an increased expression with a FC ranging from 1.5 to 3.53 for 14 protein or a decreased expression with a FC ranging from 1.5 to 4.61 for 23 proteins. In a functional annotation clustering analysis (Fig 6A), mosquito SGE was shown to mostly up-regulate proteins involved in nucleosome assembly (9/12), transcription regulation (4/6), associated with the nucleolus (8/9) or with chromatin binding functions (5/7). Conversely, SGE was shown to mostly down-regulate membrane-associated proteins (8/12) involved in cell-cell adhesion (6/8) (Fig 6A).

Fig 6. Functional clustering analysis of proteins modulated by mosquito SGE during JEV or WNV infection.

Percentage of proteins up(red)- and down(green)-regulated in functional groups after JEV (A) or WNV (B) infection in the presence of mosquito SGE. Modulated proteins were clustered into functional groups using DAVID. Functional groups are organized in four domains: Biological process, Molecular function, Cellular component or Structural feature and according to their enrichment score from left to right. Total number of proteins associated to each group is noted between brackets.

In comparison with WNV infected cells in the presence or not of mosquito SGE (Fig 5C), 54 proteins were up-regulated in presence of SGE while 18 proteins were down-regulated (with a FC ranging from 1.5 to 7.71 and 1.5 to 4.12, respectively). In the case of WNV, functional annotation clustering (Fig 6B) showed a strong up-regulation of proteins involved in protein export (4/5) and protein folding (10/11), glycosylation (13/14) and cell-cell adhesion (6/8), as well as GPCR signal transduction (4/5) and ion transmembrane export (6/7). Many up-regulated proteins are located at the membrane (61% of all modulated proteins) or in the mitochondria (6/10) and exhibit ATP (8/11) or nucleotide (7/9) binding functions. Only RNA-binding proteins were substantially down-regulated by the presence of SGE (7/9).

Overall, mosquito SGE seems to have a strong impact on the proteome of human neuroblastoma cells infected by JEV or WNV. It is worth to note that the number of hits was much greater for the proteome of JEV or WNV infected cells in presence of SGE, as compared to that in the absence of SGE (166 up- and 174 down-regulated for JEV, 147 up- and 247 down-regulated for WNV, see S9 and S10 Tables). Resulting protein networks were considerably wider (S3 and S4 Figs), further confirming the influence of mosquito saliva on the response of a human neuron model to JEV or WNV infection.

Discussion

Viral infections of the CNS still represent a challenge for modern medicine as they are associated with a high mortality rate [34]. To shed a new light on the infection of the CNS by two major neurotropic flaviviruses, we designed a comparative quantitative proteomic study of JEV or WNV infected human neuroblastoma cells. The quantification of viral genomic polyproteins and host proteins supports the view that the higher replication rate of WNV (IS98) is associated with a better control of the immune response compared to JEV (RP9) [35,36]. This variation in immune response control could correlate with the down-regulation of TRIM25 which was described to be essential to establish an IFN response to WNV infection [37]. Moreover, antigen processing is impaired in WNV infected fibroblasts [38], possibly in relation to the down-regulation of ERAP2.

Overall, neuroblastoma proteome profiles observed during JEV or WNV infection in our study show strong similarities in the way neurotropic flaviviruses disturb the host cell. A substantial number of proteins together with several functional clusters are similarly up- or down-regulated during JEV and WNV infections. This findings could correlate with the many similarities observed between the CNS diseases induced by JEV and WNV [39][40].

Surprisingly, our study corroborates only partially previous works on WNV- or JEV- infected cell proteome. We confirmed induction of the immune response by JEV previously observed in HeLa cells [8], as well as up-regulation of SAMD9 not only by JEV but also by WNV. From all the pathways and cellular factors identified in a study performed on mouse brain and neuroblastoma [9], only ERP29 was modulated in our work (S2 Table). However, while it was up-regulated in mouse cells, we observed a slight down-regulation in our human cells (FC: 1.66). Regarding WNV, our results on the immune response pathway and STAT1 factor corroborated that of [10] in Vero cells and of [11] in the mouse brain. Finally, GSK3B, PNKP and RB1, which were suggested as targets to control the neuroinflammation in response to WNV infection in the glioblastoma cell line U251 [12], were not modulated in our study. Altogether, these discrepancies may stem from the choice of cellular and animal model used to perform proteomic studies on flaviviruses [41] or possible technical limitations in the resolution of 2D-DIGE and labeled MS compared to whole-cell extract and label free MS [42].

As for the microarray-based study comparing JEV and WNV in mouse brain [13], we were able to confirm expression modulation of several cellular functions and notably up-regulation of the immune response: IFIT1, OAS1, STAT1 and IRF9 as well as IFIT3 which in our study was up-regulated by both JEV and WNV. Interestingly, modulation of tRNA charging, which was the only function determined as specific to flaviviruses [13], was also observed here. However, only SARS was up-regulated by WNV in our study, together with PTRHD1 which was not described in the mouse transcriptome analysis [13]. Conversely, SARS2 is down-regulated by JEV and HARS2 is down-regulated by WNV. Finally, two proteins not matching with the microarray hit study but involved in glutamate metabolism were modulated in our study: GLUL and ASNS, which are both up-regulated while glutamate metabolism was described as down-regulated in the microarray study.

Interestingly, we observed in our study a strong down-regulation of proteins associated with the extracellular matrix organization, collagen and cell-cell adhesion in both JEV- and WNV-infected neuroblastoma cells. This observation is consistent with the destruction of the extracellular matrix and collagen IV by MMP9 metalloprotease previously described for both JEV in rat astrocytes and WNV in mouse brain [43,44]. It is worth to note that the only metalloproteases identified in our study were all down-regulated: MIPEP, YME1L, ECE1 and MME.

PAM and SSBP2, the most down-regulated proteins by JEV and WNV infections, were not assigned to any functional cluster or connected to the network of proteins modulated during either JEV or WNV infection. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a link between JEV or WNV and expression of these two proteins. PAM is a key enzyme for the activation of neuropeptides [45], which immuno-modulatory effects are important for infection by other neurotropic viruses [46,47]. Thus, by targeting PAM expression, JEV and WNV could modulate the host response to viral infection. Furthermore, down-regulation of SSBP2 expression, a protein notably involved in RNA transcription, could be linked to the control of gene expression during flavivirus infection [48]. This is also consistent with modulation of the expression of several genes involved in transcription regulation and mRNA processing by JEV (RPRD2, POLR2A and CD2BP2), by JEV and WNV (YBX1, BCAS2, FRG1) or only by WNV (SYNCRIP). Interestingly, phosphorylation of YBX1 and POLR2A was modulated during WNV infection in a separate study [12].

The role of mosquito saliva in arbovirus infection is well-established [18,49,50], and while it is well-established for WNV [24], it has yet to be confirmed for JEV. Under the hypothesis that various factors from mosquito saliva may be able to reach the BBB and CNS, either independently or bound to the virus [40], our data suggest that mosquito saliva has the capacity to strongly affect JEV and WNV neuropathogenesis. Mosquito saliva alone has a low impact on neuroblastoma cells, only decreasing the expression of a group of proteins involved in nucleocytoplasmic transport, potentially modulating the nuclear translocation of JEV and WNV proteins [51] or the global host response to viral infection [52]. Interestingly, the differences in protein expression in JEV and WNV infected cells which are distinct between SGE-treated and untreated cells suggest a synergy between the virus and the saliva to disturb cellular homeostasis. While mosquito saliva mostly modulates transcription regulation-related proteins in association with JEV infection, it essentially modulates protein maturation and trafficking in association with WNV infection. Although several studies reported an immune response inhibition by mosquito saliva to WNV infection and especially of TNFα [53] or IFN [54], our study does not establish a specific down-regulation of their signaling in our human neuron model.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, we provide here the first proteomic comparison of JEV or WNV infected human neuroblastoma cells using a label-free quantification of whole-cell extract approach. Major host functions such as immune response, extracellular matrix organization, collagen metabolism, transcription regulation and mRNA processing are highly modulated during both JEV and WNV infections. Furthermore, mosquito saliva appears to have a strong impact on the infection of neuroblastoma cells by JEV or WNV. To confirm the capacity and depth of modulation of neurotropic flavivirus infection of the CNS by mosquito saliva, new studies should focus on advanced cell culture models combining a BBB to a compartment reflecting the CNS complexity in vitro. Furthermore, it would be interesting to compare the effects of neurotropic flaviviruses or non-flavivirus neurotropic viruses on the proteome of infected cells in order to determine their specificity.

Supporting information

The dendrogram was obtained in Perseus v1611.

(PDF)

Viral titer (A) and protein quantification (B) of the infection in the samples processed by mass spectrometry.

(PDF)

Networks of up(red)- and down(green)-regulated proteins. PPI networks were determined with STRING and visualized with Cytoscape. Proteins regulated in common with JEV are highlighted in bold. Node size is relative to the number of edges. Edges are determined according to the number of sources (text mining, experiments, databases or co-expression) supporting the link between proteins.

(PDF)

Networks of up(red)- and down(green)-regulated proteins. PPI networks were determined with STRING and visualized with Cytoscape. Proteins regulated in common with WNV are highlighted in bold. Node size is relative to the number of edges. Edges are determined according to the number of sources (text mining, experiments, databases or co-expression) supporting the link between proteins.

(PDF)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in the JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells compared to the Mock.

(XLSX)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in the JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells.

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in the JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells compared to untreated cells.

(XLSX)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells compared to untreated cells.

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change of the JEV- (or secondly to WNV-) infected cells compared to the untreated mock.

(XLSX)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change of the JEV- (or secondly to WNV-) infected cells compared to the untreated mock.

(XLSX)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [55] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD016805.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

VC and NP received grant #278433 by the European Union Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013) PREDEMICS (https://predemics.biomedtrain.eu/cms/) The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Mukhopadhyay S, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. A structural perspective of the flavivirus life cycle. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2005;3: 13–22. 10.1038/nrmicro1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludlow M, Kortekaas J, Herden C, Hoffmann B, Tappe D, Trebst C, et al. Neurotropic virus infections as the cause of immediate and delayed neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2015;131: 159–184. 10.1007/s00401-015-1511-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sips GJ, Wilschut J, Smit JM. Neuroinvasive flavivirus infections. Rev Med Virol. 2011;22: 69–87. 10.1002/rmv.712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.S H-J, N H, M H, MakiElin, W C, T BD, et al. Susceptibility of a North American Culex quinquefasciatus to Japanese Encephalitis Virus. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 140 Huguenot Street, 3rd Floor New Rochelle, NY 10801 USA; 2015;15: 709–711. 10.1089/vbz.2015.1821 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.de Wispelaere M, Desprès P, Choumet V. European Aedes albopictus and Culex pipiens are Competent Vectors for Japanese Encephalitis Virus. Turell MJ, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11: e0005294–19. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Sabatino D, Bruno R, Sauro F, Danzetta ML, Cito F, Iannetti S, et al. Epidemiology of West Nile Disease in Europe and in the Mediterranean Basin from 2009 to 2013. BioMed Research International. Hindawi Publishing Corporation; 2014;2014: 1–10. 10.1155/2014/907852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pastorino B, Nougairède A, Wurtz N, Gould E, de Lamballerie X. Role of host cell factors in flavivirus infection: Implications for pathogenesis and development of antiviral drugs. Antiviral Research. 2010;87: 281–294. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L-K, Chai F, Li H-Y, Xiao G, Guo L. Identification of Host Proteins Involved in Japanese Encephalitis Virus Infection by Quantitative Proteomics Analysis. J Proteome Res. 2013;12: 2666–2678. 10.1021/pr400011k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sengupta N, Ghosh S, Vasaikar SV, Gomes J, Basu A. Modulation of Neuronal Proteome Profile in Response to Japanese Encephalitis Virus Infection. Peterson KE, editor. PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science; 2014;9: e90211–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pastorino B, Boucomont-Chapeaublanc E, Peyrefitte CN, Belghazi M, Fusaï T, Rogier C, et al. Identification of Cellular Proteome Modifications in Response to West Nile Virus Infection. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; 2009;8: 1623–1637. 10.1074/mcp.M800565-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraisier C, Camoin L, Lim SM, Bakli M, Belghazi M, Fourquet P, et al. Altered Protein Networks and Cellular Pathways in Severe West Nile Disease in Mice. Norris PJ, editor. PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science; 2013;8: e68318 10.1371/journal.pone.0068318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H, Sun J, Ye J, Ashraf U, Chen Z, Zhu B, et al. Quantitative Label-Free Phosphoproteomics Reveals Differentially Regulated Protein Phosphorylation Involved in West Nile Virus-Induced Host Inflammatory Response. J Proteome Res. 2015;14: 5157–5168. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke P, Leser JS, Bowen RA, Tyler KL. Virus-Induced Transcriptional Changes in the Brain Include the Differential Expression of Genes Associated with Interferon, Apoptosis, Interleukin 17 Receptor A, and Glutamate Signaling as Well as Flavivirus-Specific Upregulation of tRNA Synthetases. mBio. American Society for Microbiology; 2014;5: e00902–14–e00902–14. 10.1128/mBio.00902-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mostashari F, Bunning ML, Kitsutani PT, Singer DA, Nash D, Cooper MJ, et al. Epidemic West Nile encephalitis, New York, 1999: results of a household-based seroepidemiological survey. The Lancet. 2001;358: 261–264. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05480-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer M, Hills S, Staples E, Johnson B, Yaich M, Solomon T. Japanese encephalitis prevention and control: advances, challenges, and new initiatives. Emerging …. 2008. 10.1128/9781555815592.ch6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bannon M. Encephalitis caused by flaviviruses. QJM. Oxford University Press; 2012;105: 217–218. 10.1093/qjmed/hcs035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suen WW, Prow NA, Hall RA, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. Mechanism of West Nile virus neuroinvasion: a critical appraisal. Viruses. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2014;6: 2796–2825. 10.3390/v6072796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider BS, Higgs S. The enhancement of arbovirus transmission and disease by mosquito saliva is associated with modulation of the host immune response. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102: 400–408. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox J, Mota J, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Diamond MS, Rico-Hesse R. Mosquito Bite Delivery of Dengue Virus Enhances Immunogenicity and Pathogenesis in Humanized Mice. J Virol. 2012;86: 7637–7649. 10.1128/JVI.00534-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wichit S, Ferraris P, Choumet V, Missé D. The effects of mosquito saliva on dengue virus infectivity in humans. Curr Opin Virol. Elsevier B.V; 2016;21: 139–145. 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider BS, Soong L, Girard YA, Campbell G, Mason P, Higgs S. Potentiation of West Nile encephalitis by mosquito feeding. Viral Immunol. 2006;19: 74–82. 10.1089/vim.2006.19.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reisen WK, Chiles RE, Kramer LD, Martinez VM, Eldridge BF. Method of Infection Does Not Alter Response of Chicks and House Finches to Western Equine Encephalomyelitis and St. Louis Encephalitis Viruses. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2000;37: 250–258. 10.1603/0022-2585-37.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Styer LM, Lim PY, Louie KL, Albright RG, Kramer LD, Bernard KA. Mosquito Saliva Causes Enhancement of West Nile Virus Infection in Mice. J Virol. 2011;85: 1517–1527. 10.1128/JVI.01112-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moser LA, Lim P-Y, Styer LM, Kramer LD, Bernard KA. Parameters of Mosquito-Enhanced West Nile Virus Infection. Diamond MS, editor. J Virol. American Society for Microbiology; 2015;90: 292–299. 10.1128/JVI.02280-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths RB, Gordon RM. An apparatus which enables the process of feeding by mosquitoes to be observed in the tissues of a live rodent; together with an account of the ejection of saliva and its significance in Malaria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1952;46: 311–319. 10.1080/00034983.1952.11685536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choumet V, Attout T, Chartier L, Khun H, Sautereau J, Robbe-Vincent A, et al. Visualizing non infectious and infectious Anopheles gambiae blood feedings in naive and saliva-immunized mice. Schneider BS, editor. PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science; 2012;7: e50464 10.1371/journal.pone.0050464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao-Lormeau V-M. Dengue viruses binding proteins from Aedes aegypti and Aedes polynesiensis salivary glands. Virol J. BioMed Central; 2009;6: 35 10.1186/1743-422X-6-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alsaleh K, Khou C, Frenkiel M-P, Lecollinet S, Vàzquez A, de Arellano ER, et al. The E glycoprotein plays an essential role in the high pathogenicity of European-Mediterranean IS98 strain of West Nile virus. Virology. 2016;492: 53–65. 10.1016/j.virol.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi M, Chang C-Y, Clough T, Broudy D, Killeen T, MacLean B, et al. MSstats: an R package for statistical analysis of quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomic experiments. Bioinformatics. 2014;30: 2524–2526. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Da Wei Huang Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. Nature Publishing Group; 2009;4: 44–57. 10.1038/nprot.2008.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. Oxford University Press; 2009;37: 1–13. 10.1093/nar/gkn923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v10: protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43: D447–52. 10.1093/nar/gku1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. Cold Spring Harbor Lab; 2003;13: 2498–2504. 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swanson PA II, McGavern DB. Viral diseases of the central nervous system. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;11: 44–54. 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diamond MS. Evasion of innate and adaptive immunity by flaviviruses. Immunology and Cell Biology. 2003;81: 196–206. 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2003.01157.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gack MU, Diamond MS. Innate immune escape by Dengue and West Nile viruses. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;20: 119–128. 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang P, Arjona A, Zhang Y, Sultana H, Dai J, Yang L, et al. Caspase-12 controls West Nile virus infection via the viral RNA receptor RIG-I. Nat Immunol. 2010;11: 912–919. 10.1038/ni.1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnold SJ, Osvath SR, Hall RA, King NJC, Sedger LM. Regulation of antigen processing and presentation molecules in West Nile virus-infected human skin fibroblasts. Virology. 2004;324: 286–296. 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guarner J, Shieh W-J, Hunter S, Paddock CD, Morken T, Campbell GL, et al. Clinicopathologic study and laboratory diagnosis of 23 cases with West Nile virus encephalomyelitis. Human Pathology. 2004;35: 983–990. 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.German AC, Myint KSA, Mai NTH, Pomeroy I, Phu NH, Tzartos J, et al. A preliminary neuropathological study of Japanese encephalitis in humans and a mouse model. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. Oxford University Press; 2006;100: 1135–1145. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mashimo T, Lucas M, Simon-Chazottes D, Frenkiel M-P, Montagutelli X, Ceccaldi P-E, et al. A nonsense mutation in the gene encoding 2“-5-”oligoadenylate synthetase/L1 isoform is associated with West Nile virus susceptibility in laboratory mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99: 11311–11316. 10.1073/pnas.172195399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abdallah C, Dumas-Gaudot E, Renaut J, Sergeant K. Gel-Based and Gel-Free Quantitative Proteomics Approaches at a Glance. International Journal of Plant Genomics. 2012;2012: 1–17. 10.1155/2012/494572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang P, Dai J, Bai F, Kong KF, Wong SJ, Montgomery RR, et al. Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 Facilitates West Nile Virus Entry into the Brain. J Virol. 2008;82: 8978–8985. 10.1128/JVI.00314-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tung W-H, Tsai H-W, Lee I-T, Hsieh H-L, Chen W-J, Chen Y-L, et al. Japanese encephalitis virus induces matrix metalloproteinase-9 in rat brain astrocytes via NF-κB signalling dependent on MAPKs and reactive oxygen species. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;161: 1566–1583. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00982.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bolkenius FN, Ganzhorn AJ. Peptidylglycine alpha-amidating mono-oxygenase: neuropeptide amidation as a target for drug design. Gen Pharmacol. 1998;31: 655–659. 10.1016/s0306-3623(98)00192-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weihe E, Bette M, Preuss MAR, Faber M, Schäfer MK-H, Rehnelt J, et al. Role of virus-induced neuropeptides in the brain in the pathogenesis of rabies. Dev Biol (Basel). 2008;131: 73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yaraee R, Ebtekar M, Ahmadiani A, Sabahi F. Neuropeptides (SP and CGRP) augment pro-inflammatory cytokine production in HSV-infected macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2003;3: 1883–1887. 10.1016/S1567-5769(03)00201-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang H, Samanta S, Nagarajan L. SSBP2, a candidate tumor suppressor gene, induces growth arrest and differentiation of myeloid leukemia cells. Oncogene. Nature Publishing Group; 2005;24: 2625–2634. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conway MJ, Colpitts TM, Fikrig E. Role of the Vector in Arbovirus Transmission. Annual Review of Virology. 2014;1: 71–88. 10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pingen M, Bryden SR, Pondeville E, Schnettler E, Kohl A, Merits A, et al. Host Inflammatory Response to Mosquito Bites Enhances the Severity of Arbovirus Infection. Immunity. The Author(s); 2016;44: 1455–1469. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lopez-Denman A, Mackenzie J. The IMPORTance of the Nucleus during Flavivirus Replication. Viruses. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2017;9: 14–11. 10.3390/v9010014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Le Sage V, Mouland A. Viral Subversion of the Nuclear Pore Complex. Viruses. 2013;5: 2019–2042. 10.3390/v5082019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conway MJ, Watson AM, Colpitts TM, Dragovic SM, Li Z, Wang P, et al. Mosquito Saliva Serine Protease Enhances Dissemination of Dengue Virus into the Mammalian Host. J Virol. American Society for Microbiology; 2014;88: 164–175. 10.1128/JVI.02235-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schneider BS, McGee CE, Jordan JM, Stevenson HL, Soong L, Higgs S. Prior Exposure to Uninfected Mosquitoes Enhances Mortality in Naturally-Transmitted West Nile Virus Infection. Baylis M, editor. PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science; 2007;2: e1171 10.1371/journal.pone.0001171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perez-Riverol Y, Csordas A, Bai J, Bernal-Llinares M, Hewapathirana S, Kundu DJ, et al. The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47: D442–D450. 10.1093/nar/gky1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The dendrogram was obtained in Perseus v1611.

(PDF)

Viral titer (A) and protein quantification (B) of the infection in the samples processed by mass spectrometry.

(PDF)

Networks of up(red)- and down(green)-regulated proteins. PPI networks were determined with STRING and visualized with Cytoscape. Proteins regulated in common with JEV are highlighted in bold. Node size is relative to the number of edges. Edges are determined according to the number of sources (text mining, experiments, databases or co-expression) supporting the link between proteins.

(PDF)

Networks of up(red)- and down(green)-regulated proteins. PPI networks were determined with STRING and visualized with Cytoscape. Proteins regulated in common with WNV are highlighted in bold. Node size is relative to the number of edges. Edges are determined according to the number of sources (text mining, experiments, databases or co-expression) supporting the link between proteins.

(PDF)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in the JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells compared to the Mock.

(XLSX)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in the JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells.

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in the JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells compared to untreated cells.

(XLSX)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change in JEV- (or secondly in WNV-) infected cells compared to untreated cells.

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change of the JEV- (or secondly to WNV-) infected cells compared to the untreated mock.

(XLSX)

Proteins are sorted according to the fold change of the JEV- (or secondly to WNV-) infected cells compared to the untreated mock.

(XLSX)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.