Abstract

First study of phytosynthesis of TiO2 NPs using the leaf (KL), pod (KP), seed (KS) and seed shell (KSS) extracts of kola nut tree (Cola nitida) is herein reported. The TiO2 NPs were characterized and evaluated for their antimicrobial, dye degradation, antioxidant and anticoagulant activities. The nearly spherical-shaped particles had λmax of 272.5–275.0 nm with size range of 25.00–191.41 nm. FTIR analysis displayed prominent peaks at 3446.79, 1639.49 and 1382.96 cm−1, indicating the involvement of phenolic compounds and proteins in the phytosynthesis of TiO2 NPs. Both SAED and XRD showed bioformation of crystalline anatase TiO2 NPs which inhibited multidrug-drug resistant bacteria and toxigenic fungi. The catalytic activities of the particles were profound, with degradation of malachite green by 83.48–86.28 % without exposure to UV-irradiation, scavenging of DPPH and H2O2by 51.19–60.08 %, and 78.45–99.23 % respectively. The particles as well prevented the coagulation of human blood. In addition to the antimicrobial and dye-degrading activities, we report for the first time the H2O2 scavenging and anticoagulant activities of TiO2 NPs, showing that the particles can be useful for catalytic and biomedical applications.

Keywords: Materials science, Materials analysis, Nanotechnology, Microbiology, Biomedical engineering, Cola nitida, Phytosynthesis, Titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles, Biomedical applications

Materials science; Materials analysis; Nanotechnology; Microbiology; Biomedical engineering; Cola nitida; Phytosynthesis; Titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles; Biomedical applications

1. Introduction

Nanotechnology is a vast field that is making impacts in all fields of human life. Nanotechnology is the manufacturing and exploitation of materials whose components exist at the nanoscale (1–100 nm in size). Nanotechnology explores electrical, optical and magnetic activities as well as structural behaviour at the molecular and sub-molecular level making them suitable for wide range of applications including biomedicine [1, 2]. Nanotechnology is not only concerned about the size of very small things; it is the revolutionary science and the art of controlling matter at the atomic or molecular scale to produce products with some desired and novel features or properties. When a matter is as small as 1–100 nm, many of its features will change easily with a number of unique features that are different from the bulk form.

Among several metal oxide nanoparticles, titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) are non-toxic with oxidation potency and elevated stability to light resulting into their broad applications in environmental remediation [3, 4]. In addition, TiO2 NPs possess fascinating dielectric, optical, antimicrobial, chemical and catalytic properties which lead to industrial applications such as cosmetics, pigment, fillers, whitening and brightening of foods, in personal care products like toothpaste, and photocatalyst [5, 6, 7, 8]. Furthermore, its low toxicity and biocompatibility have expanded the applications in food and biomedical areas as bone tissue engineering, dentistry and drug manufacturing [9, 10, 11, 12]. In view of the important applications of TiO2 NPs, it has been efficiently synthesized using biological resources such as bacteria, fungi and plants in eco-friendly and simple way [13, 14]. To further broaden the horizon of synthesis and applications of nanoparticles, researchers continue to explore different bioresources for their production [15, 16].

Cola nitida (Sterculiaceae) is an evergreen tree which grows to a height of 12–20 m, and is commonly found in Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast and Liberia. The trunk can measure up to 1.5 m in diameter along with older trees which develop buttresses. The bark is thick and fibrous, with deep longitudinal fissures. It is grey or brownish-grey, with pinkish-red wood which becomes visible when the bark is damaged. It has been cultivated in other parts of the World such as India, Australia, Malaysia, Trinidad, Jamaica, Brazil, and Hawaii [17]. Kola nut tree contains compounds that have antimicrobial [18, 19], anti-inflammatory [20], antidiuretic [21], antidiabetic [22], antioxidative [23] and anticancer [24] activities. The plant has also been used to treat cardiovascular disease, whooping cough and asthma [25, 26].

Aside the pharmaceutical potentials of C. nitida, different parts of the plant have been employed as microbial substrate to produce enzyme and enhancement of nutritional qualities [27, 28] and also for the synthesis of silver and silver-gold alloy nanoparticles [29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35] for different biomedical and environmental applications. This work therefore seeks to extend the border of the potential applications of extracts of different parts of kola nut in nanobiotechnology. Evidently, this represents the first study on synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles using extracts of C. nitida for biomedical and catalytic applications. Suffice also, to state that until now, there is no report on the H2O2 scavenging and anticoagulant properties of TiO2 NPs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection and preparation

Leaves and fruits of C. nitida were obtained from a local farm in Ogbomoso, Oyo State. The seeds and seed shells were removed from the pods and these were cut into smaller pieces. Thereafter, chopped seeds, seed shells, pods and leaves were air-dried for 5 days under ambient condition, after which they were milled separately into powder using an electric blender and stored in airtight container [31]. To obtain the extracts, one gram of each sample was dispersed in 100 ml of water, heated at 60 °C for 1 h and clarified using Whatman No. 1 filter paper followed with centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min.

2.2. Phytosynthesis and characterization of TiO2 NPs

Prior to phytosynthesis, the precursor was obtained by preparing 1 mM of TiO(OH)2 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in distilled water. The particles (KP-, KL-, KS- and KSS TiO2 NPs) were prepared as follows: 20 ml of each extract was added distinctively to a reaction vessel containing 100 ml of 1 mM TiO(OH)2 at room temperature for 1 h to observe the colour change. The precursor TiO(OH)2 served as the control. The nanoparticles were characterized using different analytical techniques as earlier described [31, 36]. UV-vis spectroscopy was investigated by scanning from 190 to 900 nm on a spectrophotometer (Cecil, USA), while FTIR spectra were obtained on Affinity-1S spectrometer (Shimadzu, UK), after dried particles were mixed with KBr pellets. TEM images were obtained by placing a drop of colloidal TiO2 NPs separately on a 200 mesh hexagonal copper grid (3.05 mm) (Agar Scientific, Essex, UK) coated with 0.3 % formvar dissolved in chloroform and examined on JEM-1400 TEM (JEOL, USA). Furthermore, micrographs and elemental compositions of the colloidal particles were obtained on a LYRA 3 TESCAN FESEM coupled with Energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) (Oxford), that was operated at 20.0 kV. Also, XRD was used to analyze the nanoparticles.

2.3. Selection of antibiotic resistant bacterial isolates

Test bacterial isolates from clinical investigations were obtained from LAUTECH Teaching Hospital, Ogbomoso and screened for susceptibility using a panel of antibiotics on Mueller Hinton Agar plates by disc diffusion assay as previously demonstrated [37]. Gram positive discs (Rapid Labs., UK) impregnated with antibiotics containing (μg): ceftazidime (Caz), 30; cefuroxime (Crx), 30; gentamicin (Gen), 10; cefixime (Cxm), 5; ofloxacin (Ofl), 5; augmentin (Aug), 30; nitrofurantoin (Nit), 300; and ciprofloxacin (Cpr), 5, as well as Gram negative discs containing (μg): ceftazidime (Caz), 30; cefuroxime (Crx), 30; gentamicin (Gen), 10; ciprofloxacin (Cpr), 5; ofloxacin, (Ofl), 5; amoxycillin (Aug), 30; nitrofurantoin (Nit), 300; and ampicillin (Amp), 10 were used for the evaluation. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h, and afterwards, the zones of inhibition were examined and interpreted [38]. The multi-drug resistant isolates that included Staphylococcus aureus obtained from pus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa obtained from wound, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae obtained from urine were selected for further investigation.

2.4. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of synthesized TiO2 NPs

The antibacterial efficacy of the phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs was investigated separately against strains of clinical bacterial isolates using the modified broth culture method as described [39]. Eight milliliter of 24 h-old cultures of bacterial isolates containing 1.0 × 106 cfu/ml were exposed to 1 ml of respective nanoparticles in the concentration range of 20–80 μg/ml and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Bacterial suspension without exposure to the nanoparticles serve as the control. The growth of the bacterial isolates was measured at 600 nm using UV-visible spectrophotometer. The percentage growth inhibition was estimated using Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where A is the absorbance.

The antifungal activities of KL-TiO2 NPs, KP-TiO2 NPs, KS-TiO2 NPs and KSS-TiO2 NPs were determined using mycelial growth inhibition test [40] by inoculating 7 mm disc of 48 h-old culture of Aspergillus niger and Fusarium solani on potato dextrose agar that have been incorporated with TiO2 NPs at final concentrations of 60 and 80 μg/ml. The control plate contained no nanoparticles. All the plates were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 72 h. The radial fungal growths in all the plates were measured and the percentage growth inhibitions were calculated using Eq. (2):

| (2) |

where D is the diameter of fungal growth.

2.5. Catalytic activity of TiO2 NPs

The dye degrading abilities of the phytosynthesized KL-TiO2 NPs, KP-TiO2 NPs, KS-TiO2 NPs and KSS-TiO2 NPs were investigated separately using malachite green according to Lateef et al. [41] under ambient light in the laboratory. In this case, 1 ml of nanoparticles (10, 20, 40 and 80 μg/ml) was reacted with 9 ml of malachite green (40 ppm), while the control was without exposure to the nanoparticles. The reaction took place for 24 h at room temperature on rotary shaker (100 rpm), after which the absorbance readings were obtained at 619 nm. Percentage dye degradation was calculated using Eq. (3) [42].

| (3) |

where A is the absorbance value.

2.6. Antioxidant activities of TiO2 NPs

2.6.1. DPPH radical-scavenging activity

The modified methods of Azeez et al. [43] and Lateef et al. [44] were used to study the free radical-scavenging activity of the KL-TiO2 NPs, KP-TiO2 NPs, KS-TiO2 NPs and KSS-TiO2 NPs using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl or DPPH (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). About 1 ml of graded concentration of the TiO2 NPs was added separately to 4.0 ml of a methanolic solution of 0.1 mM DPPH. The mixture was mixed and allowed to react for 30 min at room temperature, after which absorbance readings were taken at 517 nm. The blank was 0.1 mM methanol DPPH which served as control. The scavenging percentage of DPPH was calculated according to Eq. (4).

| (4) |

2.6.2. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity

The ability of the phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs to scavenge hydrogen peroxide was determined according to the methods of Bhakya et al. [45]. Hydrogen peroxide (40 mM) was prepared in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and 0.6 ml of it was reacted with 4 ml of each of the TiO2 NPs at room temperature for 20 min. The H2O2 solution was used as the control while distilled water was used as blank and the absorbance readings was read at 610 nm. The percentage peroxide scavenging activity was calculated using Eq. (5):

| (5) |

where A is the absorbance.

2.7. Anticoagulant activity of TiO2 NPs

The anticoagulant activity of the TiO2 NPswas investigated separately by mixing 0.5 ml of a donor's blood with 1 ml of 80 μg/ml of TiO2 NPs. The control samples was set up using EDTA bottle, TiO(OH)2 solution and extracts of kola leaf (KLE), pod (KPE), seed (KSE), and seed shell (KSSE). The mixtures were held at room temperature for 1 h and then examined for coagulation of blood [46].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Phytosynthesis of TiO2 NPs

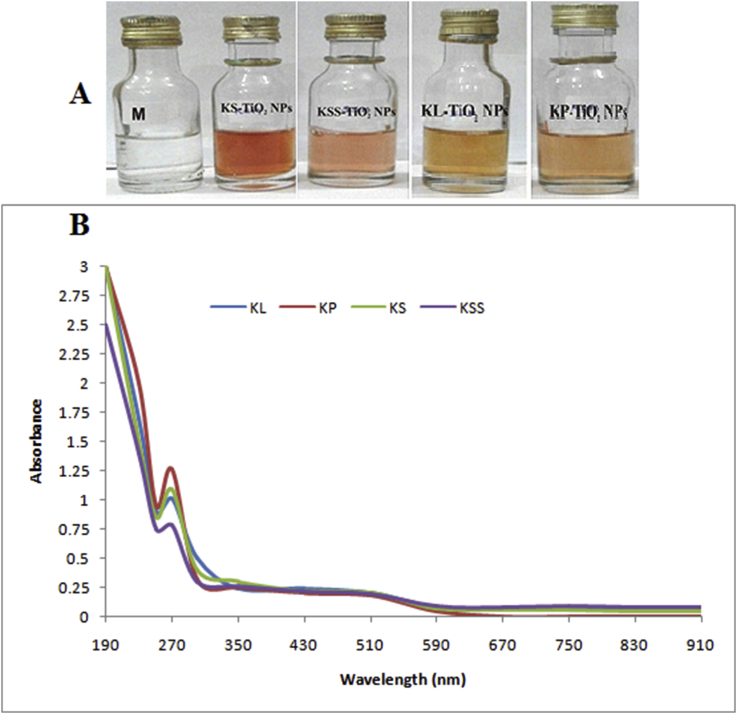

The TiO2 NPs were synthesized by a novel, simple, and green biological procedure using pod, seed, seed shell and leaf extracts of C. nitida. The TiO(OH)2 solution lacking aqueous extract was observed to show no colour change, and there was no evidence for the formation of nanoparticles (Figure 1a). But there was a noticeable colour change to golden yellow after the separate addition of extracts due to the reduction of titanium ions. Several authors have reported different colours of TiO2 NPs colloidal solution like dark brown by Ganesan et al. [47] using extract of Ageratina altissima (L.), while Dobrucka [48] reported green colour using aqueous extract of Echnacea pupurea herba. Nithya et al. [49] and Rajakumar et al. [50] both reported light green colloidal TiO2 NPs using the leaf extract of Aloe vera and Eclipta prostrata respectively.

Figure 1.

(a) Colour change in the synthesis of colloidal TiO2 NPs (b) UV-vis spectra of colloidal solution of TiO2 NPs.

3.2. Characterization of biosynthesized TiO2 NPs

UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy is significant in monitoring the formation and stability of metal nanoparticles in aqueous solution. The spectrum of the metal nanoparticles is due to a lot of factor which include the size of particle, shape and agglomeration (particle-particle interaction) with the medium. Figure 1b revealed the UV-vis absorption spectra of the nanoparticles within the range of 272.5–275 nm. These values are similar to 270 nm obtained by Valli and Jayalaskshmi [51] using Erythrina variegata leaf extract for the synthesis of TiO2 NPs. Also, Dobrucka [48] reported maximum absorbance at 280 nm for TiO2 NPs using Echinacea pupurea herba.

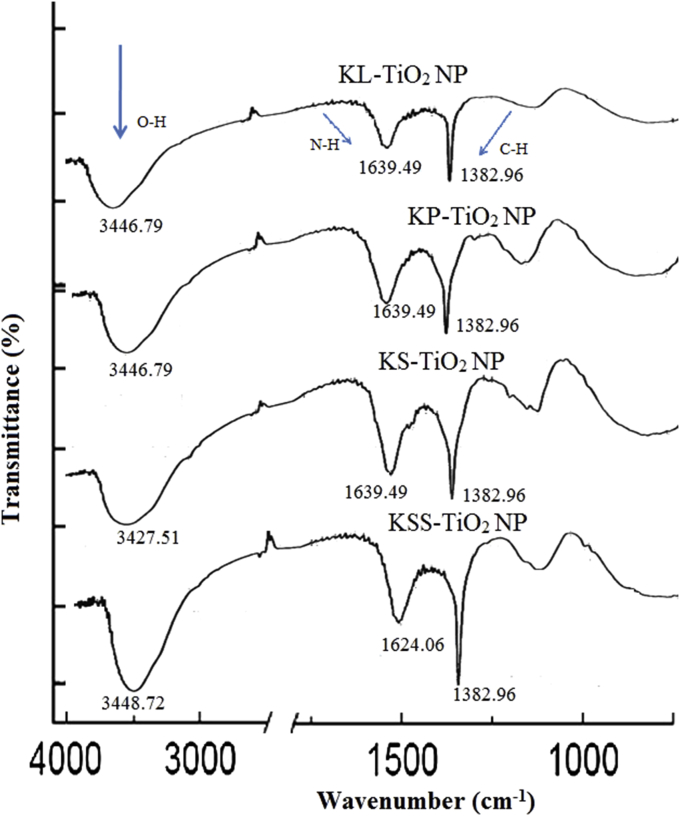

The FTIR analysis was used to identify the capping, reducing as well as stabilizing capacity of the extracts. It was used to determine the functional groups that are separately attached to TiO2 NPs. The FTIR spectra showed the presence of three prominent peaks in the nanoparticles (Figure 2). The stretches 3427–3448 and 1624-1639 cm−1 correspond to O–H stretch of carboxylic acid or N–H of amines respectively which shows that phenolics and protein are involved in the biosynthesis of TiO2 NPs, while 1382.96 cm−1 corresponds to C–H in plane bend stretching of alkenes [52]. This proves that TiO2 NPs were synthesized with C. nitida compounds involved in the biological reduction of TiO(OH)2 and subsequent capping of the synthesized TiO2 NPs. Kola nut as well as its parts have been reported to have approximately 15.24% protein, with sufficient abundance of kolatine, alkaloids, phenolic compounds, essential oils, caffeine, theobromine and nicotine [19, 53, 54].

Figure 2.

The FTIR spectra of phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs.

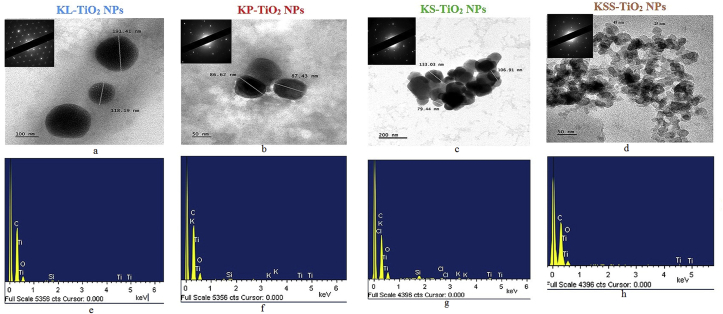

TEM images as shown in Figures 3a–d revealed that the TiO2 NPs were polydispersed with sizes in the range of 118–191.41, 86.62–87.43, 79.44–133 and 25–50 nm for KL-TiO2 NPs, KP-TiO2 NPs, KS-TiO2 NPs and KSS-TiO2 NPs respectively and were of near spherical morphology. The SAED of the biosynthesized TiO2 NPs as shown in the inset of Figures 3a-d yielded ring patterns. This demonstrates that the samples are made up of crystalline particles. Some scattered bright spots seen in the diffraction patterns indicate slightly larger crystalline grain size. These observations are similar to earlier reports on TiO2 NPs [55, 56]. EDX analysis showed the titanium peaks within 0.4–4.9 keV (Figure 3e-h) as previously observed [57, 58]. Other elements such C, Si, Cl and K that are depicted in EDX are impurities from the plant extracts.

Figure 3.

(a–d) Transmission electron micrographs (inset, selected area electron diffraction pattern) and (e–h) energy dispersive x-ray signals of phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs.

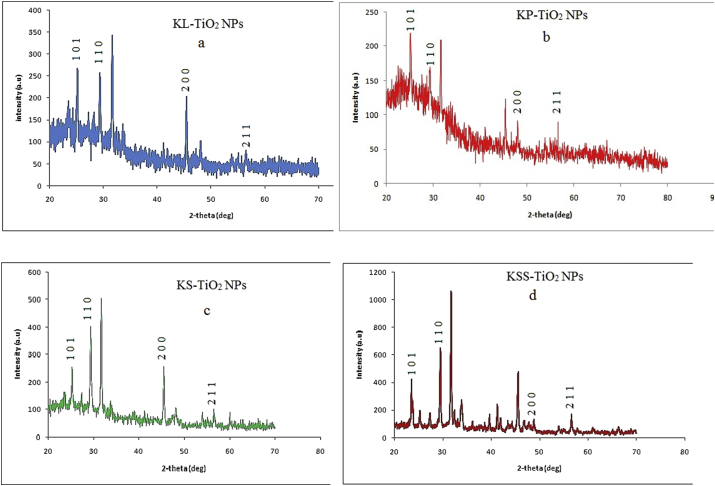

The XRD patterns of phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs (Figures 4a–d) showed major peaks appeared with 2θ values around 25.0°, 29.0°, 47.0° and 56. 0˚depicting the formation of anatase TiO2 NPs as reported by previous authors [51, 57, 58] and indexed to JCPDS file no. 84–1285 [59]. Using the Scherrer's equation

| (6) |

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction patterns of phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs (a, KL; b, KP; c, KS; d, KSS).

The average sizes of the particles were 143.01, 85.16, 85.81 and 34.34 nm for KL-, KP-, KS- and KSS- TiO2 NPs, respectively. The unidentified peaks are ascribed to impurities on the particles as earlier evidenced in the EDX spectra.

3.3. Antimicrobial activities of phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs

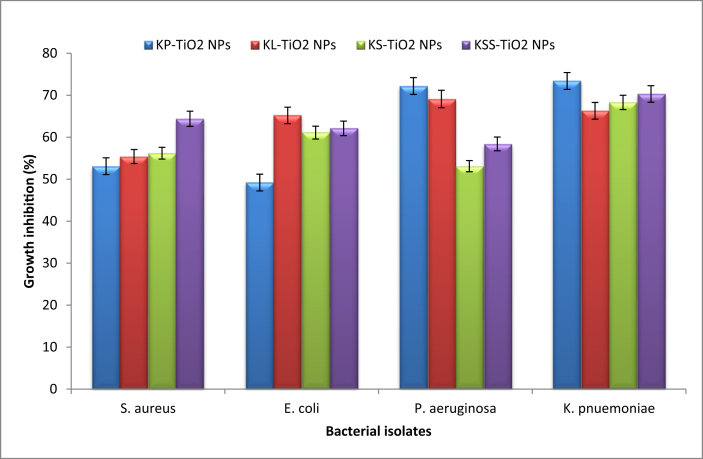

The susceptibility test of the bacterial isolates showed that S. aureus (pus) was resistant to crx, caz, aug, cxc, ery; P. aeruginosa (wound) was resistant to amp, caz, crx, gen, cpr, ofl, aug; while E. coli (urine) and K. pneumoniae (wound) were resistant to aug, amp, caz and crx. However, the isolates were sensitive to the TiO2 NPs, while they were not inhibited by the plant extracts and the precursor. The highest percentage growth inhibition of the synthesized TiO2 NPs at 80 μg/ml ranged from 49.2% against E. coli to 73.4% against K. pneumoniae by KP-TiO2 NPs (Figure 5). The cumulative growth inhibitions by the particles were 59.68, 63.80, 61.98 and 64.00% for KS-TiO2 NPs, KSS-TiO2 NPs, KP-TiO2 NPs and KL-TiO2 NPs respectively. Among the isolates, K. pneumoniae was the most sensitive, with the average growth inhibition of 69.58% by the TiO2 NPs, while S. aureus had the least growth inhibition of 57.28%. Different types of biosynthesized TiO2 NPs have shown the ability to inhibit the growth of antibiotic susceptible strains of S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae [56, 58, 60, 61, 62] at concentrations of 20–250 μg/ml. It is noteworthy in the present investigation that the phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs inhibited growth of bacteria that showed drug resistance to 4–7 antibiotics. This is an indication that the synthesized TiO2 NPs can be useful to combat drug resistance among bacteria in clinical and environmental applications. Evidences have shown that TiO2 NPs can inhibit or kill bacterial cells through adherence to cell wall to initiate damage and leakage of intracellular contents, release of Ti4+, generation of reactive oxygen species and hydroxyl radicals [57, 58, 61].

Figure 5.

Antibacterial activities of TiO2 NPs at 80 μg/ml using broth method.

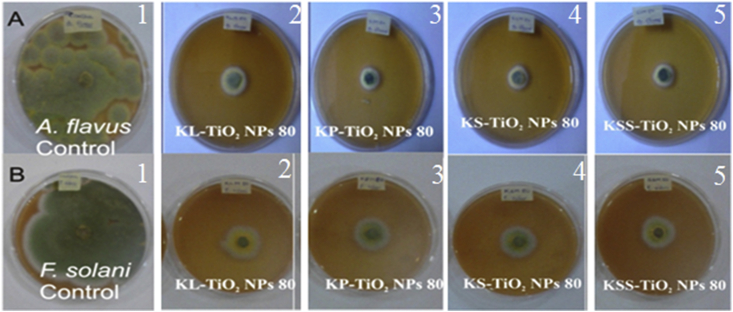

The biosynthesized TiO2 NPs demonstrated significant antifungal activities of 71.44–84.72% revealing differences among the treatments but in dose-dependent manner. At 80 μg/ml, KL-TiO2 NPs, KP-TiO2 NPs, KS-TiO2 NPs and KSS-TiO2 NPs had growth inhibition of 82.13, 84.72, 84.41 and 84.53% respectively against Aspergillus flavus, while inhibition of 79.32, 76.16, 76.13 and 79.22% were obtained against Fusarium solani (Figure 6). Growth inhibition of A. niger by biosynthesized TiO2 NPs has been reported in literature [52, 58], however there is dearth of data on the activities of green synthesized TiO2 NPs against A. flavus and F. solani, which are important toxigenic fungi in agricultural and food production. Thus, these kola nut-mediated TiO2 NPs can find useful application in preventing growth of the toxigenic fungi in food production.

Figure 6.

Antifungal activities of phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs at 80 μg/ml against (a) A. flavus (b) F. solani (1, control; 2, KL; 3, KP; 4, KS; 5, KSS).

3.4. Catalytic activity of phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs

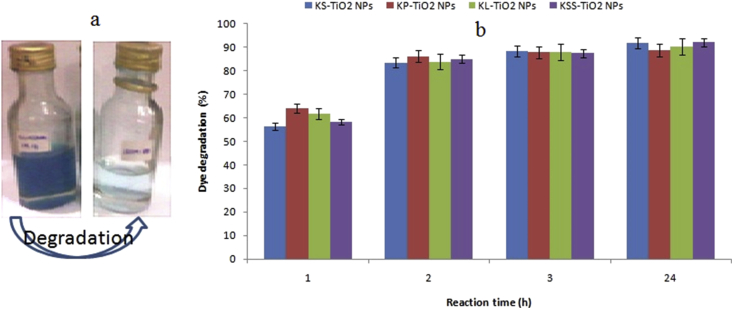

Malachite green was effectively degraded by phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs at different concentrations of 10, 20, 40, 60, and 80 μg/ml. However, best performances were obtained at 80 μg/ml in the range of 56.42–92.12% within a period of 24 h (Figure 7) without UV-irradiation. At 2 h of reaction, degradations of malachite green by 83.48–86.28% were achieved by the nanoparticles. In all, the final dye degrading activities of the particles are comparable. Both green and chemically-synthesized TiO2 NPs have been used to degrade malachite green [63, 64, 65, 66] usually under photocatalytic condition. Therefore, the phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs used in this study can be used to remediate malachite green polluted effluent in the textile industry. Nanoparticles have been shown to serve as electron transfer mediators between the biomolecules on the surface of particles and dye, thereby catalyzing the degradation of the dye through redox reaction [46, 67].

Figure 7.

Degradation of malachite green by phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs (a, visual observation; b, % dye degradation).

3.5. Antioxidant activities of phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs

3.5.1. DPPH radical-scavenging activity of TiO2 NPs

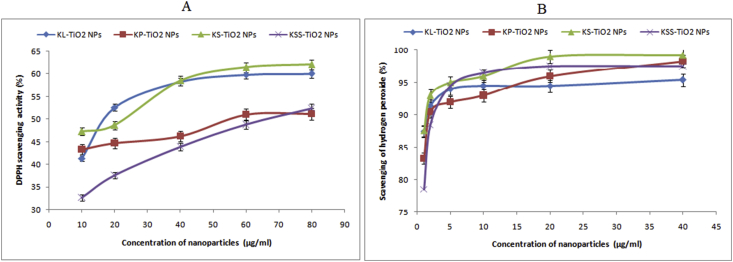

The biosynthesized TiO2 NPs were capable of causing decolourization of DPPH after the incubation time and thus indicated that they are antioxidant in nature. DPPH was scavenged at tested concentrations of 10–80 μg/ml in dose dependent manner to yield responses of 32.61–62.06% (Figure 8a). Among the phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs, kola seed mediated particles were the most potent, while the least activities were obtained for KSS-TiO2 NPs having highest performance of 52.37%. Authors have reported DPPH scavenging activities of 2–85% for TiO2 NPs biosynthesized using plants such as Psidium guajava, Pithecellobium dulce, Lagenaria siceraria, Allium eriophyllum and Artemisia haussknechtii [60, 68, 69, 70] at concentrations ranging from 1-1000 μg/ml. The present report proves that TiO2 NPs produced using kola extracts can attack disease-causing free radicals.

Figure 8.

Scavenging activities of phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs (a) DPPH and (b) H2O2.

3.5.2. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging activities of phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs

The phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs showed high significant scavenging activities of 78.45–99.23 % (Figure 8b) against H2O2 in dose dependent manner. At the moment, there are no reports on the H2O2 scavenging activity of TiO2 NPs, however authors have reported the scavenging activities of cerium oxide, silver, gold, silver-gold alloy and platinum nanoparticles on H2O2 [36,40,45,71,72] with very high performances. Thus, this study represents the first reference on hydrogen scavenging activity by TiO2 NPs, which can be explored in the environmental degradation of H2O2 to prevent the generation of highly reactive and hazardous hydroxyl radicals.

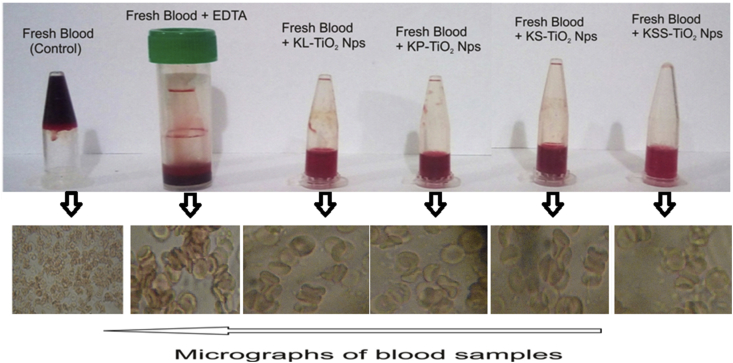

3.6. Anticoagulant activities of phytosynthesized TiO2 NPs

The coagulation of human blood in vitro was prevented by all the TiO2 NPs retaining the morphology of red blood cells as obtained in the fresh blood collected in the EDTA bottle (Figure 9). This was similar to our earlier reports on the anticoagulant activities of silver, gold and silver-gold alloy nanoparticles [40, 73, 74, 75]. The extracts as well as TiO(OH)2 were not active as anticoagulants leading to failure to prevent coagulation of blood. Though there is growing trend in the anticoagulant activities of nanoparticles [73, 76, 77] for improved management of blood coagulation disorders, there is no report on the anticoagulant activities of TiO2 NPs until now.

Figure 9.

Anticoagulant activities of TiO2 NPs synthesized using extracts of different parts of Cola nitida on human blood.

4. Conclusion

This study has shown the effectiveness of leaf, pod, seed and seed shell extracts of C. nitida for the synthesis of TiO2 NPs. The particles were of near spherical morphology, crystalline and anatase in nature with maximum UV absorbance within 272.5–275.0 nm. The polydispersed particles had sizes ranging from 25.00 to 191.41 nm. The antibacterial and antifungal activities of the TiO2 NPs were remarkable, while they also displayed good dye degradation, DPPH and hydrogen peroxide scavenging activities as well as prevention of coagulation of human blood in vitro. This work represents the first report on the use of extracts of different parts of C. nitida for the synthesis of TiO2 NPs, and for both hydrogen peroxide scavenging and anticoagulant activities. These sets of properties of the synthesized TiO2 NPs would impact positively on their exploitation in healthcare and environmental applications.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Akinola, P.O.: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Lateef, A.: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Asafa, T.B., Irshad, H.M.: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Beukes, L.S., Hakeem, A.S.: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Girón-Vázquez N.G., Gómez-Gutiérrez C.M., Soto-Robles C.A., Nava O., Lugo-Medina E., Castrejón-Sánchez V.H., Vilchis-Nestor A.R., Luque P.A. Study of the effect of Persea americana seed in the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their antimicrobial properties. Results Phys. 2019;13:102142. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naz S., Islam M., Tabassum S., Fernandes N.F., de Blanco E.J.C., Zia M. Green synthesis of hematite (α-Fe2O3) nanoparticles using Rhus punjabensis extract and their biomedical prospect in pathogenic diseases and cancer. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1185:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakata K., Ochiai T., Murakami T., Fujishima A. Photoenergy conversion with TiO2 photocatalysis: new materials and recent applications. Electrochim. Acta. 2012;84:103–111. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan W., Peralta-Videa J.R., Gardea-Torresdey J.L. Interaction of titanium dioxide nanoparticles with soil components and plants: current knowledge and future research needs–a critical review. Environ. Sci. J. Integr. Environ. Res. Nano. 2018;5(2):257–278. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang W., Xing M., Zhang J. Modifications on reduced titanium dioxide photocatalysts: a review. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2017;32:21–39. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chouirfa H., Bouloussa H., Migonney V., Falentin-Daudré C. Review of titanium surface modification techniques and coatings for antibacterial applications. Acta Biomater. 2019;83:37–54. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haider A.J., Jameel Z.N., Al-Hussaini I.H. Review on: titanium dioxide applications. Energy Procedia. 2019;157:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vujovic M., Kostic E. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: a review of toxicological data. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2019;70(5):223–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkler H.C., Notter T., Meyer U., Naegeli H. Critical review of the safety assessment of titanium dioxide additives in food. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018;16(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0376-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zamani M., Rostami M., Aghajanzadeh M., Manjili H.K., Rostamizadeh K., Danafar H. Mesoporous titanium dioxide@ zinc oxide–graphene oxide nanocarriers for colon-specific drug delivery. J. Mater. Sci. 2018;53(3):1634–1645. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Augustine A., Augustine R., Hasan A., Raghuveeran V., Rouxel D., Kalarikkal N., Thomas S. Development of titanium dioxide nanowire incorporated poly (vinylidene fluoride–trifluoroethylene) scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2019;30(8):96. doi: 10.1007/s10856-019-6300-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Çeşmeli S., Biray Avci C. Application of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles in cancer therapies. J. Drug Target. 2019;27(7):762–766. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2018.1527338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sivaranjani V., Philominathan P. Synthesize of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Moringa oleifera leaves and evaluation of wound healing activity. Wound Med. 2016;12:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waghmode M.S., Gunjal A.B., Mulla J.A., Patil N.N., Nawani N.N. Studies on the titanium dioxide nanoparticles: biosynthesis, applications and remediation. SN Appl. Sci. 2019;1(4):310. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adelere I.A., Lateef A. A novel approach to the green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles: the use of agro-wastes, enzymes and pigments. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2016;5(6):567–587. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lateef A., Ojo S.A., Elegbede J.A. The emerging roles of arthropods and their metabolites in the green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2016;5(6):601–622. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adebola P.O. Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2011. Cola; pp. 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muhammad S., Fatima A. Studies on phytochemical evaluation and antibacterial properties of two varieties of kolanut (Cola nitida) in Nigeria. J. Biosci. Med. 2014;2(3):37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adesanwo J.K., Ogundele S.B., Akinpelu D.A., McDonald A.G. Chemical analyses, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of extracts from Cola nitida seed. J. Explor. Res. Pharmacol. 2017;2(3):67–77. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daels-Rakotoarison D.A., Kouakou G., Gressier B., Dine T., Brunet C., Luyckx M., Bailleul F., Trotin F. Effects of a caffeine-free Cola nitida nuts extract on elastase/alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor balance. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003;89(1):143–150. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Obika L.F.O., Babatunde E.O., Akoni F.A., Adeeko A.O., Nsaho J., Reza H., Williams S.A. Kolanut (Cola nitida) enhances antidiuretic activity in young dehydrated subjects. Phytother Res. 1996;10(7):563–568. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oboh G., Nwokocha K.E., Akinyemi A.J., Ademiluyi A.O. Inhibitory effect of polyphenolic–rich extract from Cola nitida (Kolanut) seed on key enzyme linked to type 2 diabetes and Fe2+ induced lipid peroxidation in rat pancreas in vitro. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014;4:S405–S412. doi: 10.12980/APJTB.4.2014C75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erukainure O.L., Oyebode O.A., Sokhela M.K., Koorbanally N.A., Islam M.S. Caffeine–rich infusion from Cola nitida (kola nut) inhibits major carbohydrate catabolic enzymes; abates redox imbalance; and modulates oxidative dysregulated metabolic pathways and metabolites in Fe2+-induced hepatic toxicity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017;96:1065–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.11.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solipuram R., Koppula S., Hurst A., Harris K., Naragoni S., Fontenot K., Gray W. Molecular and biochemical effects of a kola nut extract on androgen receptor-mediated pathways. J. Toxicol. 2009 doi: 10.1155/2009/530279. Article ID 530279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odebode A.C. Phenolic compounds in the kola nut (Cola nitida and Cola acuminata) (Sterculiaceae) in Africa. Rev. Biol. Trop. 1996;44:513–515. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asogwa E.U., Anikwe J.C., Ihokwunye F.C. Kola production and utilization for economic development. Afr. Sci. 2006;7:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lateef A., Oloke J.K., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Raimi O.R. Production of fructosyltransferase by a local isolate of Aspergillus niger in both submerged and solid substrate media. Acta Aliment. 2012;41(1):100–117. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lateef A., Oloke J.K., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Oyeniyi S.O., Onifade O.R., Oyeleye A.O., Oladosu O.C., Oyelami A.O. Improving the quality of agro-wastes by solid state fermentation: enhanced antioxidant activities and nutritional qualities. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;24(10):2369–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lateef A., Azeez M.A., Asafa T.B., Yekeen T.A., Akinboro A., Oladipo I.C., Ajetomobi F.E., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Beukes L.S. Cola nitida-mediated biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using seed and seed shell extracts and evaluation of antibacterial activities. BioNanoScience. 2015;5(4):196–205. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lateef A., Azeez M.A., Asafa T.B., Yekeen T.A., Akinboro A., Oladipo I.C., Azeez L., Ajibade S.E., Ojo S.A., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Beukes L.S. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using a pod extract of Cola nitida: antibacterial, antioxidant activities and application as a paint additive. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2016;10(4):551–562. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lateef A., Ojo S.A., Elegbede J.A., Azeez M.A., Yekeen T.A., Akinboro A. Evaluation of some biosynthesized silver nanoparticles for biomedical applications: hydrogen peroxide scavenging, anticoagulant and thrombolytic activities. J. Cluster Sci. 2017;28(3):1379–1392. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azeez L., Lateef A., Adebisi S.A. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) biosynthesized using pod extract of Cola nitida enhances antioxidant activity and phytochemical composition of Amaranthus caudatus Linn. Appl. Nanosci. 2017;7(1–2):59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olajire A.A., Abidemi J.J., Lateef A., Benson N.U. Adsorptive desulphurization of model oil by Ag nanoparticles-modified activated carbon prepared from brewer’s spent grains. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017;5(1):147–159. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yekeen T.A., Azeez M.A., Akinboro A., Lateef A., Asafa T.B., Oladipo I.C., Oladokun S.O., Ajibola A.A. Safety evaluation of green synthesized Cola nitida pod, seed and seed shell extracts-mediated silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using Allium cepa assay. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2017;11(6):895–909. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azeez L., Adejumo A.L., Ogunbode S.M., Lateef A., Adetoro R.O. Influence of calcium nanoparticles (CaNPs) on nutritional qualities, radical scavenging attributes of Moringa oleifera and risk assessments on human health. J. Food Meas. Char. 2020;14(4):2185–2195. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elegbede J.A., Lateef A., Azeez M.A., Asafa T.B., Yekeen T.A., Oladipo I.C., Abbas S.H., Beukes L.S., Gueguim-Kana E.B. Silver-gold alloy nanoparticles biofabricated by fungal xylanases exhibited potent biomedical and catalytic activities. Biotechnol. Prog. 2019;35 doi: 10.1002/btpr.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lateef A., Ojo S.A., Akinwale A.S., Azeez L., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Beukes L.S. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using cell-free extract of Bacillus safensis LAU 13: antimicrobial, free radical scavenging and larvicidal activities. Biologia. 2015;70(10):1295–1306. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lateef A., Ojo S.A., Azeez M.A., Asafa T.B., Yekeen T.A., Akinboro A., Oladipo I.C., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Beukes L.S. Cobweb as novel biomaterial for the green and eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Appl. Nanosci. 2016;6(6):863–874. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lateef A., Folarin B.I., Oladejo S.M., Akinola P.O., Beukes L.S., Gueguim-Kana E.B. Characterization, antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticoagulant activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Petiveria alliacea L. leaf extract. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018;48(7):646–652. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2018.1479864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elegbede J.A., Lateef A., Azeez M.A., Asafa T.B., Yekeen T.A., Oladipo I.C., Aina D.A., Beukes L.S., Gueguim-Kana E.B. Biofabrication of gold nanoparticles using xylanases through valorization of corncob by Aspergillus niger and Trichoderma longibrachiatum: antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticoagulant and thrombolytic activities. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2020;11(3):781–791. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lateef A., Akande M.A., Ojo S.A., Folarin B.I., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Beukes L.S. Paper wasp nest-mediated biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial, catalytic, anti-coagulant and thrombolytic applications. 3Biotech. 2016;6:140. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0459-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghaedi M., Sadeghian B., Amiri P.A., Sahraeib R., Daneshafar A., Duran C. Kinetics, thermodynamics and equilibrium evaluation direct yellow 12 removal by adsorption onto silver nanoparticles loaded activated carbon. Chem. Eng. 2012;187:133–141. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Azeez L., Lateef A., Wahab A.A., Rufai M.A., Salau A.K., Ajayi I.O., Ajayi E.M., Maryam A.K., Adebisi B. Phytomodulatory effects of silver nanoparticles on Corchorus olitorius: its antiphytopathogenic and hepatoprotective potentials. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019;136:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lateef A., Azeez M.A., Asafa T.B., Yekeen T.A., Akinboro A., Oladipo I.C., Azeez L., Ajibade S.E., Ojo S.A., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Beukes L.S. Cocoa pod husk extract-mediated biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles: its antimicrobial, antioxidant and larvicidal activities. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2016;6(2):159–169. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhakya S., Muthukrishnan S., Sukumaran M., Muthukumar M. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2016;6:755–766. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oladipo I.C., Lateef A., Elegbede J.A., Azeez M.A., Asafa T.B., Yekeen T.A., Akinboro A., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Beukes L.S., Oluyide T.O., Atanda O.R. Enterococcus species for the one-pot biofabrication of gold nanoparticles: characterization and nanobiotechnological applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017;173:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ganesan S., Ganesh B.I., Mahendran D., Indra A.P., Elangovan N., Geetha N., Venkatachalam P. Green engineering of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Ageratina altissima (L.) King & H.E. Robines medicinal plant aqueous leaf extracts for enhanced photocatalytic activity. Ann. Phytomed. 2016;5(2):69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dobrucka R. Synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Echinacea purpurea herba. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. (IJPR) 2017;16(2):756–762. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nithya A., Rokesh K., Jothivenkatachalam K. Biosynthesis, characterization and application of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Nano Vision. 2013;3(3):169–174. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rajakumar G., Abdul Rahuman A., Priyamvada B., Gopiesh Khanna V., Kishore Kumar D. Eclipita prostrata leaf aqueous extract mediated synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 2012;68:115–117. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valli G., Jayalakshmi A. Erythrina variegata leaves extract assisted synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in an eco-friendly approach. Eur. J. Biomed. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2015;2(3):1228–1236. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malarkodi C., Chitra K., Rajeshkumar S., Gnanajobitha G., Paulkumar K., Vanaja M., Annadurai G. Novel eco-friendly synthesis of titanium oxide nanoparticles by using Planomicrobium sp. and its antimicrobial evaluation. Der Pharm. Sin. 2013;4(3):59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dewole E.A., Dewumi D.F.A., Alabi J.Y.T., Adegoke A. Proximate and phytochemical of Cola nitida and Cola acuminata. Pakistan J. Biol. Sci. 2013;16(22):1593–1596. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2013.1593.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Omwirhiren E.M., Abass A.O., James S.A. The phytochemical constituents and relative antimicrobial activities against clinical pathogens of different seed extracts of Cola nitida (Vent.), Cola acuminata (Beauvoir) and Garcinia kola (Heckel) grown in South West, Nigeria. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2017;6(1):493–501. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ajmal N., Saraswat K., Bakht M.A., Riadi Y., Ahsan M.J., Noushad M. Cost-effective and eco-friendly synthesis of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles using fruit’s peel agro-waste extracts: characterization, in vitro antibacterial, antioxidant activities. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2019;12(3):244–254. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rajkumari J., Magdalane C.M., Siddhardha B., Madhavan J., Ramalingam G., Al-Dhabi N.A., Arasu M.V., Ghilan A.K., Duraipandiayan V., Kaviyarasu K. Synthesis of titanium oxide nanoparticles using Aloe barbadensis mill and evaluation of its antibiofilm potential against Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019;201:111667. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Subhapriya S., Gomathipriya P. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles by Trigonella foenum-graecum extract and its antimicrobial properties. Microb. Pathog. 2018;116:215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sundrarajan M., Bama K., Bhavani M., Jegatheeswaran S., Ambika S., Sangili A., Nithya P., Sumathi R. Obtaining titanium dioxide nanoparticles with spherical shape and antimicrobial properties using M. citrifolia leaves extract by hydrothermal method. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017;171:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hudlikar M., Joglekar S., Dhaygude M., Kodam K. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles by using aqueous extract of Jatropha curcas L. latex. Mater. Lett. 2012;75:196–199. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santhoshkumar T., Rahuman A.A., Jayaseelan C., Rajakumar G., Marimuthu S., Kirthi A.V., Velayutham K., Thomas J., Venkatesan J., Kim S.K. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Psidium guajava extract and its antibacterial and antioxidant properties. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014;7(12):968–976. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahmad R., Mohsin M., Ahmad T., Sardar M. Alpha amylase assisted synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles: structural characterization and application as antibacterial agents. J. Hazard Mater. 2015;283:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thakur B.K., Kumar A., Kumar D. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica leaf extract and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. South Afr. J. Bot. 2019;124:223–227. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abou-Gamra Z.M., Ahmed M.A. TiO2 nanoparticles for removal of malachite green dye from waste water. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015;5(3):373. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma Y., Ni M., Li S. Optimization of malachite green removal from water by TiO2 nanoparticles under UV irradiation. Nanomaterials. 2018;8(6):428. doi: 10.3390/nano8060428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soni H., Kumar J.N., Patel K., Kumar R.N. Photocatalytic decoloration of three commercial dyes in aqueous phase and industrial effluents using TiO2 nanoparticles. Desalination Water Treat. 2016;57(14):6355–6364. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sreekanth T.V.M., Shim J.J., Lee Y.R. Degradation of organic pollutants by bio-inspired rectangular and hexagonal titanium dioxide nanostructures. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017;169:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nandhini N.T., Rajeshkumar S., Mythili S. The possible mechanism of eco-friendly synthesized nanoparticles on hazardous dyes degradation. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019;19:101138. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alavi M., Karimi N. Characterization, antibacterial, total antioxidant, scavenging, reducing power and ion chelating activities of green synthesized silver, copper and titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Artemisia haussknechtii leaf extract. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018;46(8):2066–2081. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1408121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kalyanasundaram S., Prakash M.J. Biosynthesis and characterization of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Pithecellobium dulce and Lagenaria siceraria aqueous leaf extract and screening their free radical scavenging and antibacterial properties. ILCPA. 2015;50:80–95. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seydi N., Saneei S., Jalalvand A.R., Zangeneh M.M., Zangeneh A., Tahvilian R., Pirabbasi E. Synthesis of titanium nanoparticles using Allium eriophyllum Boiss aqueous extract by green synthesis method and evaluation of their remedial properties. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019;33(11) [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Y., Wu H., Li M., Yin J.J., Nie Z. pH dependent catalytic activities of platinum nanoparticles with respect to the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide and scavenging of superoxide and singlet oxygen. Nanoscale. 2014;6(20):11904–11910. doi: 10.1039/c4nr03848g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhou G., Li Y., Zheng B., Wang W., Gao J., Wei H., Li S., Wang S., Zhang J. Cerium oxide nanoparticles protect primary osteoblasts against hydrogen peroxide induced oxidative damage. Micro Nano Lett. 2014;9(2):91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lateef A., Ojo S.A., Elegbede J.A., Akinola P.O., Akanni E.O. Nanomedical applications of nanoparticles for blood coagulation disorders. In: Dasgupta N., Ranjan S., Lichtfouse E., editors. Vol. 14. Springer International Publishing AG; Cham, Switzerland: 2018. pp. 243–277. (Environmental Nanotechnology. Environmental Chemistry for a Sustainable World). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lateef A., Ojo S.A., Folarin B.I., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Beukes L.S. Kolanut (Cola nitida) mediated synthesis of silver-gold alloy nanoparticles: antifungal, catalytic, larvicidal and thrombolytic applications. J. Cluster Sci. 2016;27(5):1561–1577. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ojo S.A., Lateef A., Azeez M.A., Oladejo S.M., Akinwale A.S., Asafa T.B., Yekeen T.A., Akinboro A., Oladipo I.C., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Beukes L.S. Biomedical and catalytic applications of gold and silver-gold alloy nanoparticles biosynthesized using cell-free extract of Bacillus safensis LAU 13: antifungal, dye degradation, anti-coagulant and thrombolytic activities. IEEE Trans. NanoBiosci. 2016;15(5):433–442. doi: 10.1109/TNB.2016.2559161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harish B.S., Uppuluri K.B., Anbazhagan V. Synthesis of fibrinolytic active nanoparticles using wheat bran xylan as a reducing and stabilizing agent. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;132:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shrivastava S., Bera T., Singh S.K., Singh G., Ramachandrarao P., Dash D. Characterization of antiplatelet properties of silver nanoparticles. Am. Chem. Soc. Nano. 2009;3:1357–1364. doi: 10.1021/nn900277t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]