Abstract

Background

Cancer survivors’ perspectives on a successful return to work (RTW) may not be captured in the common measure of RTW, namely time until RTW.

Objective

The purpose of this study was therefore to develop an RTW outcome measure that reflects employed cancer survivors’ perspectives, with items that could be influenced by an employer, i.e. the Successful Return-To-Work questionnaire for Cancer Survivors (I-RTW_CS), and to assess its construct validity and reproducibility.

Methods

First, three focus groups with cancer survivors (n = 14) were organized to generate issues that may constitute successful RTW. Second, a two-round Delphi study among 108 cancer survivors was conducted to select the most important issues. Construct validity of the I-RTW_CS was assessed using correlations with a single-item measure of successful RTW and the Quality of Working Life Questionnaire for Cancer Survivors (QWLQ-CS; n = 57). Reproducibility (test–retest reliability) was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC; n = 50).

Results

Forty-eight issues were generated, of which seven were included: ‘enjoyment in work’; ‘work without affecting health’; ‘confidence of employer without assumptions about work ability’; ‘open communication with employer’; ‘feeling welcome at work’; ‘good work–life balance’; and ‘joint satisfaction with the situation (employer and cancer survivor)’. Correlations with single-item successful RTW and QWLQ-CS were 0.58 and 0.85, respectively. The reproducibility showed an ICC of 0.72.

Conclusions

The I-RTW_CS provides an RTW outcome measure that includes cancer survivors’ perspectives and weights its items on an individual basis, allowing a more meaningful evaluation of cancer survivors’ RTW. This study provides preliminary evidence for its construct validity and reproducibility.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Current return to work (RTW) outcome measures do not capture the most important items constituting successful RTW selected by cancer survivors in the current study. |

| The newly developed questionnaire (I-RTW_CS) allows a broader, more meaningful evaluation of RTW of cancer survivors, and can be used as a patient-reported outcome measure of interventions in research and practice. |

| This study provides preliminary evidence for construct validity and reproducibility of the I-RTW_CS. |

Introduction

With increasing survival rates of cancer [1], the number of cancer survivors that may be able to return to work (RTW) or stay at work has increased. However, previous studies indicated that cancer survivors are still more likely to be unemployed compared with the general population [2]. This has resulted in a new research area with numerous studies focusing on factors associated with RTW or studies focusing on the effectiveness of interventions for RTW [3–6]. In these studies, the primary outcome, RTW, is measured as the RTW rate or the number of days from initial sick leave to full or partial RTW, a shorter period being considered as more successful [3–6]. Currently, this definition of RTW guides the design of RTW interventions, and, moreover, guides the evaluation of their effectiveness and the decision whether or not to implement an RTW intervention [7].

However, a shorter period of sick leave might not reflect what is most important for cancer survivors regarding RTW [8, 9]. For them, not RTW per se, but the specific characteristics of their individual RTW might count [10, 11]. For example, getting back to a too demanding job and not being able to meet demands at home might not be experienced as a desired RTW outcome [8, 10]. In this study, therefore we defined the degree to which the RTW meets the desired RTW as the degree of successfulness of RTW.

The consequences of using time until RTW may have led to considering interventions effective that may not be considered as successful by the people returning to work themselves. This might potentially affect the sustainability of RTW. For instance, if someone has returned to work full-time at the expense of their health, this might be considered effective using the current RTW measures, such as time until RTW. However, this may not give a true indication of the sustainability of this person’s employability [12]. It is therefore essential to develop an outcome measure that reflects the perspectives of cancer survivors on a successful RTW.

Regarding cancer and work, the role of the employer of a cancer survivor has lately received more emphasis in the scientific literature [13, 14]. Research shows that the employer is an important stakeholder in the RTW of employed cancer survivors, but also that employers need interventions that support them in their role [14, 15]. Such interventions have lately been developed [16], but their effectiveness for successful RTW of employed cancer survivors is to be studied [17]. In order to study this effect, it is essential to use an outcome measure with items that could be influenced by an employer. Otherwise, there would be a mismatch between the intervention and the outcome measure, as the intervention could, upfront, only influence part of the outcome measure. This would potentially lead to undervaluing the true effect of the intervention.

Taking the abovementioned into consideration, we wanted to develop an outcome measure that reflects the perspective of employed cancer survivors on successful RTW, with items that could be influenced by an employer—the Successful Return-To-Work questionnaire for Cancer Survivors (I-RTW_CS). The objectives of this study were (1) to develop the I-RTW_CS, and (2) to assess the construct validity and reproducibility of the I-RTW_CS.

Methods and Results

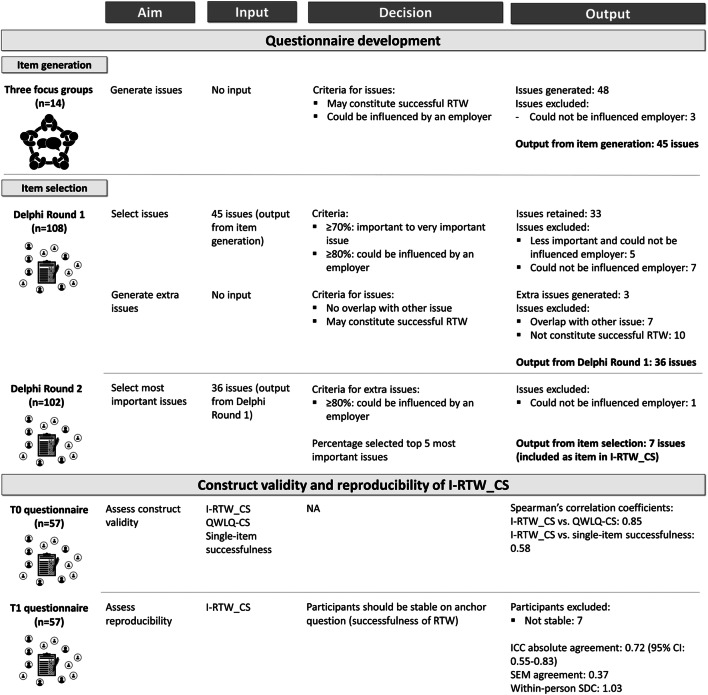

The Medical Ethics Committees of the Academic Medical Center (AMC) and Maastricht University Medical Centre and Maastricht University (MUMC+/UM) determined that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act does not apply to the studies described in this paper and had no objection to the execution of these studies (AMC: W17_477 # 17.550, W17_477 # 18.051, W18_261 # 18.305; and MUMC+/UM: 2018-0717 #184181). The methods and results for each of the two objectives are described in consecutive order below, since the results of the first objective guided the methods of the next objective (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Methods and results, by objective. RTW return to work, ICC intraclass correlation coefficient, CI confidence interval, SEM standard error of measurement, SDC smallest detectable change, I-RTW_CS Successful Return-To-Work questionnaire for Cancer Survivors, QWLQ-CS Quality of Working Life Questionnaire for Cancer Survivors, NA not applicable

Methods: Questionnaire Development

When developing the I-RTW_CS questionnaire we assumed a formative model to be most appropriate [18]. In a formative model, the individual items form the construct, as opposed to a reflective model, in which the individual items reflect the construct [18]. This means that, in a formative model, individual items are not necessarily correlated with each other and that improvement on one item does not necessarily imply improvement on other items. We based this assumption on a previous study [8], where clusters were formulated for successful RTW in people with a mental disorder, such as ‘job satisfaction’ and ‘mental functioning’. With items of this type, it is assumed that if a person improves on job satisfaction, it does not automatically mean that their mental functioning will also improve. The assumption for a formative model guided our method for selecting items for the I-RTW_CS questionnaire. Therefore, we decided to use the Delphi technique to select the items for the I-RTW_CS questionnaire, as factorial analysis is not an appropriate method in a formative model [18].

Design, Sample and Procedure

Three focus groups and a Delphi study with two rounds were conducted in consecutive order. With the focus groups, we aimed to generate issues that may constitute successful RTW, and with the Delphi study, we aimed to select the issues that constitute successful RTW most importantly, according to cancer survivors.

For the Delphi study, we calculated the sample size using a one-sided exact test for single proportion (nQuery Advisor® version 7.0). We calculated one sample size for each of the criteria of Delphi Round 1: one for the criteria that ‘at least 80% of the participants thought that the issue could be influenced by an employer’ (proportion of 80%), and one for the criteria that ‘at least 70% of the participants rated the issue as important to very important’ (proportion of 70%). The proportion minus 10% was employed as an alternative proportion (i.e. 70% and 60%, respectively). For both calculations, we used a 90% confidence level and a power of 0.80. These calculations resulted in 110 and 91 participants, respectively. Anticipating a dropout rate of five participants, we aimed to enroll at least 115 participants for the Delphi study.

Cancer survivors were recruited via social media (Facebook) and a Dutch online cancer platform (www.kanker.nl). For the Delphi study, cancer survivors were also recruited via two hospitals in The Netherlands. Potential eligible cancer survivors received an invitation letter, information sheet, approach form, and return envelope via their treating physician. For all recruitment strategies cancer survivors were asked to return the approach form (either online or by post) to MG if they met all the inclusion criteria, i.e. diagnosed with cancer < 5 years ago, of working age (18–65 years), working for an employer at the time of diagnosis and returned to work (partly or fully) in the past 2 years, or having made plans to resume work in the last 4 weeks. Self-employed cancer survivors were excluded from participation. If an approach form was returned, MG contacted the cancer survivor to explain the study concerned and to check the survivor’s eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Survivors were excluded if they did not have basic language skills in Dutch, and participants of the focus groups were excluded from the Delphi study to avoid overlap in participation. If a cancer survivor was both willing and eligible to participate, a digital informed consent form was sent. After signing this form, the cancer survivor was included in the study concerned.

Item Generation: Focus Groups

The focus groups were audio-recorded and were moderated and observed in turns by ST and MG. Participant demographics and health-related and work-related variables were obtained from self-reported questionnaires that participants filled in at home prior to the focus group. During the focus groups, participants were asked to write down individually what would entail a successful RTW for them. The focus group then started with the open-ended question “What would entail a successful RTW for you?” Thereafter, each reported issue was discussed in more detail. In this way, the participants, moderator and observer developed a list of issues that may constitute successful RTW. Finally, the participants discussed these issues one by one until consensus was reached, i.e. all participants agreed on the final decision, regarding whether or not an employer could possibly influence each issue. For this, the participants discussed whether behavior or support from an employer could possibly enable a cancer survivor to be more successful in regard to that specific issue.

The focus groups were transcribed verbatim and coded using the MAXQDA qualitative data analysis software package (Verbi Software GmbH, Marburg, Germany, 2007). First, MG assigned open codes to the focus group data that represented the text as closely as possible. Second, more or less corresponding codes were clustered and formulated as concrete issues that may constitute successful RTW. To improve consistency and reliability, a research assistant repeated both steps blindly (i.e. without having been given any information on earlier analysis). The open codes and issues that were formulated on the basis of these codes were compared and, in the case of disagreement, decisions were made during a consensus meeting with MG, ST and the research assistant. All three have had previous experience with this qualitative analysis methodology.

Item Selection: Delphi Study

Two Delphi rounds were conducted. The questionnaires of both Delphi rounds were pilot tested in respect to their formulation and use by two independent persons who were not involved in the study. The list for Delphi Round 1 consisted of the issues generated in the focus groups. The issues were displayed in four separate groups, classified on the basis of quality of life categories [19], to make it clearer and manageable for participants. Participants were asked to rate the importance of each issue on a 9-point rating scale (from not important to very important). Participants were also asked whether an employer could possibly influence the issue, i.e. whether behavior or support from an employer could possibly enable a cancer survivor to be more successful in regard to that specific issue (yes/no). This question was not included for issues that self-evidently can be influenced by an employer, as it relates to direct behavior or a direct action on the part of the employer, to avoid that these unnecessary questions would lead to annoyance among the participants. An issue was retained if at least 70% of the participants rated the issue as important to very important (i.e. 7–9 on the rating scale), and at least 80% of participants indicated that an employer could possibly influence the issue. Participants were also asked whether issues were missing (open-ended question). These issues were added to the next round if the issue did not overlap with another issue in the list and could logically constitute successful RTW for a larger group of cancer survivors, as decided by MG and ST during a consensus meeting. The list for Delphi Round 2 was shown along with the percentage of people who rated that issue important to very important in Delphi Round 1. Participants were asked to select the five issues that constituted successful RTW most importantly, according to them. In addition, participants were individually asked whether an employer could possibly influence the issues added during Delphi Round 1 (yes/no). If more than 20% of the participants indicated that an employer could not influence an issue, this issue was excluded from further analysis. Based on the distribution of the participants’ rating of most important issues, the authors decided which issues should be included as an item in the I-RTW_CS. For this, the issues were ranked on the basis of the percentage of participants who included that particular issue in their ‘top 5 most important issues’. It was decided to include only issues for which comparable high percentages were found, and stop including once this percentage started to deviate relatively more, i.e. a deviation between two issues of ± 10%. For this article, all issues and the final version of the I-RTW_CS will be translated into English by a professional translation agency, using a one-way translation method. MG and ST will discuss this translation and, in the case any doubt will arise, the issues will be sent back to the translation agency for an extra check.

Results: Questionnaire Development

Item Generation: Focus Groups

The three focus groups lasted 90–120 min each and were held in January and February 2018, with a selection of 14 cancer survivors. Six (43%) cancer survivors were younger than 50 years of age and six (43%) were male (Table 1). The most common cancer diagnosis among participants was breast cancer (n = 6; 43%) and the majority had at least undergone surgery (n = 13; 93%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, health-related and work-related characteristics of cancer survivors participating in questionnaire development [item generation—focus groups (n = 14) and item selection—Delphi study (n = 108)], and validity and reproducibility of I-RTW_CS [validation study (n = 57)]

| Sociodemographic, health-related and work-related characteristics | Questionnaire development | Validity and reproducibility I-RTW_CS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item generation: focus groups (n = 14) | Item selection: Delphi study (n = 108) | Validation study (n = 57) | ||||

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||||

| Age, years | 18–49 | 6 (43) | 18–49 | 29 (27) | 18–49 | 20 (35) |

| 50–59 | 6 (43) | 50–59 | 42 (39) | 50–59 | 24 (42) | |

| 60–65 | 2 (14) | 60–65 | 37 (34) | 60–65 | 13 (23) | |

| Gender: male | 6 (43) | 52 (48) | 16 (28) | |||

| Level of education | Low | 1 (7) | Low | 16 (15) | Low | 5 (9) |

| Middle | 7 (50) | Middle | 33 (30) | Middle | 23 (40) | |

| High | 6 (43) | High | 59 (54) | High | 29 (51) | |

| Health-related variables | ||||||

| Diagnosis | Breast cancer | 6 (43) | Breast cancer | 17 (16) | Breast cancer | 20 (35) |

| Colon cancer | 1 (7) | Colon cancer | 32 (30) | Colon cancer | 9 (16) | |

| Lymph node cancer or leukemia | 19 (18) | Ovarian cancer | 10 (18) | |||

| Kidney cancer | 11 (10) | |||||

| Other | 7 (50) | Other | 29 (27) | Other | 18 (32) | |

| Surgery: yes | 13 (93) | 83 (76) | 50 (88) | |||

| Chemotherapy: yes | 6 (43) | 64 (59) | 30 (53) | |||

| Radiation therapy: yes | 7 (50) | 35 (33) | 22 (39) | |||

| Hormone treatment: yes | 5 (36) | 14 (13) | 16 (28) | |||

| Physical comorbidity: yes | NR | NR | 9 (16) | |||

| Time since most recent diagnosis, in months (mean ± SD) | 30 ± 15 | 30 ± 14 | 16 ± 7 | |||

| Work-related variables | ||||||

| Type of employment contract: permanent | NR | NR | 54 (95) | |||

| Company size: < 50 employees | 3 (21) | 22 (20) | 6 (11) | |||

| Number of contract hours (mean ± SD) | NR | NR | 30 ± 9 | |||

| Average number of hours worked in the past 4 weeks (mean ± SD) | NR | NR | 22 ± 13 | |||

| Sector: non-profit | 5 (36) | 44 (41) | 33 (58) | |||

| Managerial position: yes | 3 (21) | 29 (27) | 5 (8) | |||

| Total duration of sick leave in months (mean ± SD) | 11 ± 6 | 11 ± 8 | NR | |||

Data are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise specified

NR not reported, SD standard deviation

The focus groups generated 48 issues in total, for example ‘that there is a good balance between your work and your leisure’, as explained by one of the participants:

“I think a re-entry is only successful if there is a balance between work and leisure. Because if you work for 24 or 40 hours and are at your last gasp at home the rest of the time (...) not being able to do anything in the weekend because you have to work again on Monday (…) then you are doing it wrong.”

Participants decided that an employer could not influence three of these issues (‘that your family shows understanding’; ‘that you do not have fear of cancer recurrence’; and ‘that everything is as it was’). The other 45 issues are shown in Table 2 (translated into English by a professional translation agency).

Table 2.

List of issues generated during the focus groups, and results of item selection (Delphi study)

| Issue | Delphi Round 1 (n = 108) (% important–very important) | Delphi Round 2 (n = 102) (% in top 5 most important issues) | Could be influenced by an employer (% ‘yes’) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | That you enjoy your work | 96 | 63 | 97 |

| 2 | That you can work without it affecting your health | 96 | 48 | 98 |

| 3 | That your employer has confidence and does not jump to conclusions about your work ability | 97 | 39 | Yes |

| 4 | That your employer communicates with you openly | 97 | 39 | Yes |

| 5 | That you feel welcome at work | 96 | 34 | 99 |

| 6 | That you have a good balance between work and leisure | 94 | 30 | 81 |

| 7 | That both you and your employer are satisfied with the situation | 96 | 27 | 95 |

| 8 | That your co-workers regard you as a normal, full-fledged employee | 95 | 17 | 93 |

| 9 | That you return to your own position with the same duties | 81 | 17 | 95 |

| 10 | That you have peace of mind, with certainty about your position or your welfare benefit | 94 | 16 | 94 |

| 11 | That you feel useful again at work and can make a contribution again | 93 | 15 | 96 |

| 12 | That your employer shows concern and interest | 93 | 15 | Yes |

| 13 | That your manager pays attention to you, also after you have resumed work | 91 | 15 | Yes |

| 14 | That you do meaningful work (meaningful for you, your co-workers or society) | 91 | 13 | 93 |

| 15 | That your employer has respect for you | 95 | 12 | Yes |

| 16 | That your co-workers accept you as part of the team | 95 | 11 | 97 |

| 17 | That you are in control of your work, for example you have freedom to organize it yourself | 86 | 11 | 94 |

| 18 | That your occupational physician acknowledges that your work ability is reduced | 93 | 8 | 81 |

| 19 | That you have security about your financial situation and wages | NR | 8 | 86 |

| 20 | That your work is compatible with your physical capabilities | 89 | 7 | 98 |

| 21 | That your manager is understanding, for example of your limitations | 89 | 7 | Yes |

| 22 | That you have the same opportunities for advancement and future prospects as before you were diagnosed | 76 | 7 | 83 |

| 23 | That your employer expresses their appreciation of your performance at work | 84 | 5 | Yes |

| 24 | That you receive financial compensation for the reduction in working hours | 74 | 5 | 85 |

| 25 | That your head is calm concerning events surrounding your diagnosis | NR | 5 | 65 |

| 26 | That your employer is well-informed about cancer and its consequences | NR | 5 | Yes |

| 27 | That your co-workers are understanding, for example of your limitations | 88 | 4 | 91 |

| 28 | That your employer acknowledges that your work ability is reduced | 87 | 4 | Yes |

| 29 | That your employer shows being aware that your work ability is reduced | 86 | 3 | Yes |

| 30 | That you have adequate facilities at work, for example workplace adjustments | 81 | 3 | 96 |

| 31 | That work gives you relaxation | 75 | 3 | 84 |

| 32 | That your co-workers show they are aware that your work ability is reduced | 71 | 3 | 90 |

| 33 | That HR pays attention to you, also after you have resumed work | 76 | 2 | Yes |

| 34 | That the personnel department is understanding, for example of your limitations | 89 | 1 | Yes |

| 35 | That you can work at a suitable workplace | 84 | 1 | 98 |

| 36 | That you can keep yourself occupied at work | 83 | 0 | 97 |

| 37 | That you feel mentally fit enough to work | 97 | NR | 74 |

| 38 | That you feel physically fit enough to work | 95 | NR | 67 |

| 39 | That you can do everything you used to be able to do before you were diagnosed | 80 | NR | 43 |

| 40 | That you have less pain while working | 78 | NR | 68 |

| 41 | That your co-workers support you by taking an interest and communicating | 78 | NR | 77 |

| 42 | That you can accept that your work ability is reduced | 73 | NR | 68 |

| 43 | That you are aware of not being able to handle as much in your work | 73 | NR | 69 |

| 44 | That you resume work as soon as possible | 56 | NR | 72 |

| 45 | That you work the same number of hours as before you were diagnosed | 56 | NR | 71 |

| 46 | That your co-workers express their appreciation of your performance at work | 55 | NR | 65 |

| 47 | That your co-workers give you a feeling of being indispensable at work | 37 | NR | 53 |

| 48 | That you have a job that gives you status | 29 | NR | 53 |

Issues included as an item of the I-RTW_CS are in italics. ‘Yes’ in the right column: for this issue, it was not asked whether or not this issue could be influenced by an employer, as it relates to behavior or a direct action on the part of the employer

NR not reported; this issue was not included in this Delphi Round

Item Selection: Delphi Study

Overall, 115 cancer survivors signed an informed consent form; 108 participants responded in the first round and 102 in the second round. Fifty-two (48%) participants filling in the first round were male (see Table 1 for all characteristics). Participants diagnosed with colon cancer were the largest subgroup (n = 32; 30%) and most had at least undergone surgery (n = 83; 76%).

Of the 45 issues, 12 were excluded after Delphi Round 1 because they did not meet one or both of the predefined criteria, i.e. < 70% of participants rated this issue as important to very important and/or < 80% of participants indicated that an employer could possibly influence the issue (Table 2). Twenty new issues were mentioned, seven of which overlapped with another issue in the list, and ten of which could logically not constitute successful RTW for a larger group of cancer survivors, as it contained a lengthy experience of their RTW or a clarification of one of their answers. Three issues were included in the list for Delphi Round 2 (Table 2).

The percentage of participants including each of the issues in their top 5 during Delphi Round 2 can be found in Table 2. After the most prevalent seven issues, this percentage decreased from 27 to 17%, which the authors decided was a considerable drop in importance. Thus, the following seven issues were included as an item in the I-RTW_CS questionnaire: ‘enjoyment in work’; ‘work without affecting health’; ‘confidence of employer without assumptions about work ability’; ‘open communication with employer’; ‘feeling welcome at work’; ‘good work–life balance’; and ‘joint satisfaction with the situation (employer and cancer survivor)’.

Response Categories in I-RTW_CS

Selection of the most important issues in the second Delphi round showed considerable variation between participants, even between the seven issues that were included as an item in the I-RTW_CS questionnaire. We therefore decided that the I-RTW_CS should be designed as a measurement instrument weighted on an individual basis, so that it takes into account individual differences between the perceived importance of each item [18, 20]. In other words, each participant indicates how important he or she perceives each item for the successfulness of their RTW on a 1–5 rating scale (1 = not important to 5 = very important), which leads to an ‘importance score’ (I_score). Subsequently, they rate each item on a 1–6 rating scale, reflecting each item’s ‘success score’ (S_score). Multiplying an items’ I_score by its S_score leads to the item’s ‘weighted score’ (W_score) (Eq. 1).

| 1 |

The sum of the W_scores of all the items (∑W_score) divided by the sum of the I_scores of all the items (∑I_score) leads to the I-RTW_CS score (Appendix 1; range 1–6) (Eq. 2):

| 2 |

The items have a reference period of the past 4 weeks. At least four items should have both an I_score and an S_score to enable the I-RTW_CS score to be calculated. The English version of the I-RTW_CS can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

The English version of the I-RTW_CS

Methods: Construct Validity and Reproducibility of I-RTW_CS

Design, Sample and Procedure

With two questionnaires, at baseline (T0) and 2 weeks of follow-up (T1), we aimed to assess the construct validity and reproducibility of the I-RTW_CS. Baseline scores were used to study construct validity, and both scores were combined to study reproducibility. To report the psychometric properties of the I-RTW_CS, the COSMIN checklist was used [21].

Four recruitment strategies were employed: via social media (Facebook); via a Dutch online cancer platform (www.kanker.nl); via a database of participants in a previous study; and via a hospital in the Netherlands. The same invitation and inclusion strategies were employed as described for the focus groups and the Delphi study. The inclusion criteria were: diagnosed with cancer < 2 years ago; of working age (18–65 years); older than 18 at the time of diagnosis; working for an employer at the time of diagnosis; and having actually been working (in their own job or a replacement job) in the past 4 weeks. Self-employed cancer survivors and survivors who did not have basic Dutch language skills to enable them to complete a questionnaire were excluded. After signing informed consent, the cancer survivor was included and received the baseline questionnaire by email.

Variables and Measures

Data were collected between October 2018 and March 2019. The main outcomes were construct validity and reproducibility. In order to study construct validity, the baseline questionnaire comprised the I-RTW_CS, the Quality of Working Life Questionnaire for Cancer Survivors (QWLQ-CS) [22], and a 10-point single-item visual analog scale with the question ‘Looking back over the past 4 weeks, how would you rate the successfulness of your RTW?’ (‘single-item successfulness’). Additionally, demographic (e.g. gender, age), health-related (e.g. treatment) and work-related variables (e.g. type of employment contract) were assessed to describe the population.

The QWLQ-CS consists of 23 items divided over five subscales, with a standardized score of 0–100, and a higher score reflecting a better quality of working life [22]. The answer option ‘does not apply’ for self-employed cancer survivors was omitted, as they were not included in this study. The QWLQ-CS has sufficient to good measurement properties in cancer survivors [22].

After 2 weeks of follow-up, cancer survivors received the T1 questionnaire consisting of the I-RTW_CS and a single-item anchor question (‘did the successfulness of your RTW change relative to 2 weeks ago?’), to identify stable participants.

Sample Size

A minimum number of 50 participants is recommended for both construct validity testing and reproducibility analysis [18]. Taking into account a 10–15% dropout rate for the reproducibility analysis, i.e. unfilled T1 questionnaires or unstable participants, we aimed to enroll 55–60 participants.

Statistical Analysis

To measure the construct validity, correlation coefficients were calculated between the I-RTW_CS and the QWLQ-CS, and between the I-RTW_CS and single-item successfulness. Based on the Shapiro–Wilkinson test, it was determined whether data were normally distributed, and, if so, a Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated. If one of the variables was not normally distributed, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated. It was hypothesized a priori that the direction and magnitude of the correlation coefficient should be 0.6–0.8 between the I-RTW_CS and QWLQ-CS outcomes, and 0.7–0.9 between the I-RTW_CS outcomes and single-item successfulness.

To measure the reproducibility of the I-RTW_CS, the test–retest reliability and the level of agreement were calculated between outcomes at T0 and T1. Cancer survivors responding ‘no’ to the anchor question were identified as ‘stable’ and were thus included in this analysis. The test–retest reliability was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) model 2, absolute agreement definition, i.e. taken both systematic and random differences between T0 and T1 into account [18], and a 95% confidence interval (CI). Next, we measured the level of agreement with the standard error of measurement (SEM) [18]. The within-person smallest detectable change (SDC) was calculated using the formula 1.96 * √2 * SEM [18]. To see whether there was a structural change between T0 and T1 (e.g. a learning effect), we used a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine whether the mean difference differed from zero. We determined the correlation between the mean scores on the I-RTW_CS (T0 and T1), and the difference scores (difference between T0 and T1), using a correlation coefficient. This was done to see whether there was a correlation between the magnitude of the score and the direction of the error. A low correlation coefficient means that the reliability is equal throughout the scale. Lastly, we analyzed the 95% limits of agreement (LoA) by plotting a Bland–Altman plot [18].

Floor and ceiling effects were assessed by calculating whether > 15% of the cancer survivors scored the lowest or highest possible score [18]. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results: Construct Validity and Reproducibility of I-RTW_CS

Twenty-five cancer survivors were included via their treating physician. Combined with the cancer survivors who were eligible and willing to participate via social media and the Dutch online cancer platform, the final sample consisted of 57 cancer survivors, who all filled in both questionnaires.

Twenty (35%) participants were younger than 50 years of age and 16 (28%) were male (Table 1). Most participants had been diagnosed with breast cancer (n = 20; 35%) and most had at least undergone surgery (n = 50; 88%). The participants’ most recent diagnosis of cancer was, on average, 16 months earlier (standard deviation 7). The median T0 I-RTW_CS score was 5.1 (interquartile range 1.05). Nine (16%) participants scored the highest score on the I-RTW_CS, while none scored the lowest.

Spearman’s correlation coefficient between the I-RTW_CS and the QWLQ-CS was 0.85, and 0.58 between the I-RTW_CS and single-item successfulness. Thus, both of the hypotheses formulated a priori were not confirmed.

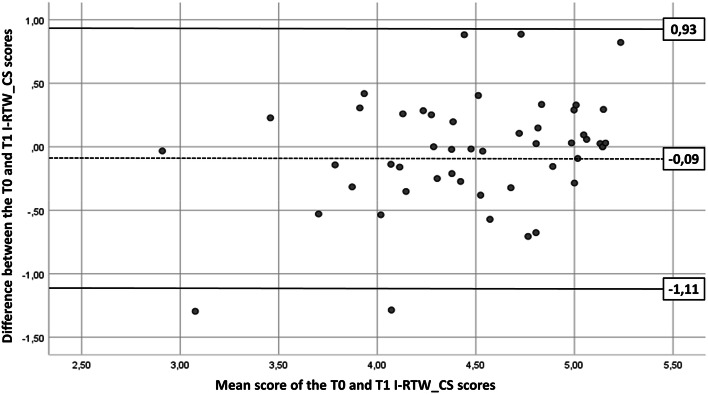

Fifty cancer survivors were considered stable based on the anchor question. The ICC absolute agreement was 0.72 (95% CI 0.55–0.83). The SEM agreement was 0.37 and the within-person SDC was 1.03. The mean difference between the T0 and T1 I-RTW_CS scores did not differ statistically from zero (p = 0.20), indicating that there is no structural difference between the score at T0 and T1. Spearman’s correlation coefficient between the mean I-RTW_CS scores and the difference scores was 0.23, indicating that the reliability is equal throughout the scale. The Bland–Altman plot shows the LoA with the means of the T0 and T1 I-RTW_CS scores and the differences between the T0 and T1 I-RTW_CS scores between the 95% CI (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The Bland–Altman plot. The means of the T0 (baseline) and T1 (2 weeks of follow-up) I-RTW_CS scores are shown on the x-axis, and the differences between the T0 and T1 I-RTW_CS scores are shown on the y-axis (T0–T1). The dotted line represents the mean difference between T0 and T1, and the solid lines represent the 95% LoA. I-RTW_CS Successful Return-To-Work questionnaire for Cancer Survivors

Discussion

The purpose of our study was to develop the I-RTW_CS and to assess its construct validity and reproducibility. Seven items were selected that represent the successfulness of RTW, and they were incorporated into the I-RTW_CS: ‘enjoyment in work’; ‘work without affecting health’; ‘confidence of employer without assumptions about work ability’; ‘open communication with employer’; ‘feeling welcome at work’; ‘good work–life balance’; and ‘joint satisfaction with the situation (employer and cancer survivor)’. The I-RTW_CS was found to be highly correlated with the QWLQ-CS and moderately correlated with the single-item measure of successful RTW, respectively. The reproducibility showed an ICC of 0.72.

Interpretation of Findings

Currently, RTW is mostly measured as the RTW rate or the number of days from initial sick leave to full or partial RTW, with a shorter period considered more successful [3–6]. The most important items constituting successful RTW, selected by cancer survivors in the current study, do not correspond with this definition of RTW. This means that RTW interventions are currently designed and valued based on RTW outcomes that may not reflect the perspective of cancer survivors themselves [7, 9].

The newly developed questionnaire is likely to be cancer-specific. When comparing the items we generated for cancer survivors with clusters for successful RTW in people with a mental disorder, it is notable that only two more or less overlap (i.e. enjoyment in work versus job satisfaction, and work–life balance versus work–home balance) [8]. In regard to successful RTW of people with a mental disorder, ‘sustainability’ and ‘mental functioning’ were also considered relevant. Differences in findings are most likely explained partly by differences in the patient journey between cancer survivors and people with a mental disorder. Mental disorders are commonly characterized by periods of better functioning interspersed with periods of less functioning [23], which makes sustainability and mental functioning very relevant. Whereas in the case of cancer, people most often have relatively few or almost no medical complaints before diagnosis, but cancer treatment such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy and radiation often leads to acute, chronic and late adverse effects that may affect the cancer survivor’s wellbeing and work ability [24–27]. As a result, cancer survivors may find feeling welcome at work after a period of absence very relevant. Additionally, the criteria for successful RTW in a study among people with traumatic brain injury also match only partly (i.e. ‘good work–life balance’ versus ‘work–home balance’) [12]. Differences between patient populations’ perspectives on successful RTW underline the importance of RTW outcomes that reflect the respective patient population’s perspectives on successful RTW. We therefore recommend determining whether the I-RTW_CS can also be validated for other non-cancer patient populations, and, if not, to develop a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) that includes issues that constitute successful RTW most importantly for these respective patient populations. In this way, the effectiveness of RTW interventions can be evaluated more meaningfully.

The outcomes of the I-RTW_CS were well correlated with outcomes of the QWLQ-CS. Similarities between both questionnaires relate to the measured constructs, i.e. ‘quality of working life’ and ‘successfulness of return to work’, and in the recall period of 4 weeks [22]. Differences relate to their usability for self-employed cancer survivors, which applies to the QWLQ-CS [22], but not for the I-RTW_CS, and in the weighting of the items based on their perceived importance for the individual cancer survivor, which only applies to the I-RTW_CS. Additionally, the I-RTW_CS is shorter than the QWLQ-CS, which may enhance its response rate and the quality of the answers [28, 29]. Lastly, although closely related, the measured constructs and individual items of the QWLQ-CS (i.e. quality of working life) and the I-RTW_CS (i.e. successfulness of RTW) do differ from each other. Both the QWLQ-CS and the I-RTW_CS can be used as a PROM, in research and practice, for employed cancer survivors. Nevertheless, we recommend future studies to assess the responsiveness and interpretability of the I-RTW_CS, as has been done for the QWLQ-CS [30], to further determine and compare their usefulness at individual and group level.

The correlation between the outcomes of the I-RTW_CS and the single-item measure of successful RTW was somewhat lower than hypothesized (i.e. r = 0.58). A possible explanation might be that the I-RTW_CS only incorporates items that an employer could possibly influence, according to the cancer survivors. Looking at the issues that were excluded on the basis of this criterion during the Delphi Round 1, only two issues could potentially have been included in the I-RTW_CS: ‘that you feel physically fit enough to work’ and ‘that you feel mentally fit enough to work’. Another explanation for the low correlation might be that cancer survivors were not able to incorporate all the possible issues of successful RTW when they scored the single-item measure of successfulness of RTW. A single-item measure is also, by definition, less reliable [18]. The number and variety of issues unveiled during the item generation clearly demonstrate the complexity of the ‘successfulness of RTW’ construct. A single-item measure may be considered inadequate for measuring such a complex construct, emphasizing the importance of a measurement instrument that justifies the complexity of the ‘successfulness of RTW’ construct. The last possible explanation lays in the items that were included in the I-RTW_CS. Although we explicitly asked ‘what would entail a successful RTW for you?’ in the focus groups, and participants often started their answer with ‘I think a re-entry is only successful when …’, the items of the I-RTW_CS seem closer related to ‘meaningful RTW’ than ‘successful RTW’ (e.g. the items on enjoyment and feeling welcome at work). We therefore recommend to further evaluate the construct validity of the I-RTW_CS, for example by comparing the I-RTW_CS with a measure of the construct ‘meaningful RTW’. Altogether, the abovementioned correlations provide preliminary evidence for the construct validity of the I-RTW_CS.

The reproducibility of the I-RTW_CS was tested using an interval of 2 weeks between the two measurement points. This interval was thought to be sufficient to minimize both the recall bias and the chance that the underlying construct of interest, the successfulness of RTW, has changed [31, 32]. The reproducibility of the I-RTW_CS outcomes of the 50 participants, who indicated that the successfulness of their RTW had not changed during that interval, was found to be acceptable at a group level (i.e. ICC of 0.72) [32]. For the I-RTW_CS, the SDC, which reflects the within-person change that can be interpreted as a ‘real’ change with a p < 0.05 certainty [32], is 1.03. This means that someone needs to change 21% of the total range of the I-RTW_CS to know, with p < 0.05 certainty, that it is a real change and not a measurement error. This percentage is slightly better than the QWLQ-CS (21% vs. 27%) [22], which means that the I-RTW_CS may measure change slightly better than the QWLQ-CS. We therefore recommend comparing the responsiveness and interpretability of the I-RTW_CS with the QWLQ-CS head-to-head in the sample to determine which questionnaire is best able to measure change.

Limitations, Strengths and Recommendations for Research and Practice

Some limitations should be addressed. First, the I-RTW_CS only incorporates items that an employer could possibly influence, according to the cancer survivors. The reason for this was that the I-RTW_CS was initiated to study the effectiveness of RTW interventions targeting the employer, aiming to enhance the successful RTW of employed cancer survivors. Including items that could not be influenced by an employer would therefore result in a mismatch between the intervention and the outcome measure, potentially leading to undervaluing the true effect of the intervention. However, taking into account the limited number of issues that were excluded on the basis of this criterion, the I-RTW_CS is thought to also be usable as an outcome measure for other interventions, such as vocational interventions targeting cancer survivors themselves. Second, only a few low-educated cancer survivors participated in the studies described, possibly affecting the generalizability of the outcomes. Whether low-educated cancer survivors would have prioritized other issues as most important for a successful RTW, for example issues of a more financial nature, is unclear and should therefore be the subject of further research. Whether the ceiling effect detected may have been a consequence of the relatively highly educated study population should also be determined in future studies, as a higher level of education has been associated with better work-related outcomes [3, 33, 34]. Furthermore, the overrepresentation of female cancer survivors with a permanent employment contract within relatively larger organizations (≥ 50 employees) may affect the generalizability of the outcomes. Lastly, the sample size of the validation study, although in accordance with the recommendations, was relatively low. A large-scale study of the psychometric properties of the I-RTW_CS, for example to study the interpretability of the I-RTW_CS and further evaluate its test–retest reproducibility and construct validity, is recommended [18, 35].

The main strength of this study is the systematic, stepwise development of the I-RTW_CS, with different samples of cancer survivors involved in the different studies. The samples were also highly heterogeneous in terms of most sociodemographic, health-related and work-related variables, which increases the generalizability of the results according to the COSMIN checklist [21]. In addition, the use of W_scores based on relative importance can be seen as a strength. In this way, a cancer survivor’s successfulness of RTW can be measured taking into account the individual work-related goals and preferences regarding RTW, as recommended in previous research [9]. We therefore recommend that future work-related intervention studies should incorporate the I-RTW_CS as a measurement instrument in addition to the current, conventional RTW outcome measures, such as time until RTW. Beside its usefulness as a measurement instrument, the I-RTW_CS could be used in practice, and help the employer and other stakeholders to understand what issues are important for successful RTW, and to tailor RTW to the individual cancer survivor by supporting them regarding the issues he or she is not yet satisfied about. Moreover, the I-RTW_CS, including its individual items, provides important input to a broader, more meaningful discussion among scholars and practitioners about how to evaluate a cancer survivor’s RTW.

Conclusions

The I-RTW_CS provides an RTW outcome measure that includes the perspectives of cancer survivors on successful RTW, and weights its items on their relative perceived importance for the individual cancer survivor. This allows a broader and more meaningful evaluation of cancer survivors’ RTW. This study provides preliminary evidence for construct validity and reproducibility of the I-RTW_CS.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank research assistant Inge Braspenning for her help in recruiting cancer survivors, and collecting and analyzing the data. The authors are also grateful to the Dutch online cancer platform ‘kanker.nl’ for their help in recruiting cancer survivors.

Appendix 1

Specimen calculation of the I-RTW_CS.

I-RTW_CS Successful Return-To-Work questionnaire for Cancer Survivors.

Author Contributions

MG, ST, AdR, MF, RL, and AdB were responsible for the study concept and design. ST, AdR and MF obtained funding for this study. MG, TdR, MK, JK, RIL and PZ recruited the participants. MG collected the data. MG and SB analyzed the data for the questionnaire development, which was checked by ST. ST analyzed the data for validity and reproducibility, which was checked by AdB. MG, ST, AdR, MF and AdB interpreted the data. MG and ST drafted the manuscript, which was critically revised by all authors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

This study was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (Grant number UVA 2014-7153).

Conflict of Interest

Michiel A. Greidanus, Angela G.E.M. De Boer, Angelique E. de Rijk, Sonja Brouwers, Theo M. de Reijke, Marie José Kersten, Jean H.G. Klinkenbijl, Roy I. Lalisang, Robert Lindeboom, Patricia J. Zondervan, Monique H.W. Frings-Dresen and Sietske J. Tamminga declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code Availability

The codes generated and/or used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paalman CH, et al. Employment and social benefits up to 10 years after breast cancer diagnosis: a population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(1):81–87. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Islam T, et al. Factors associated with return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(Suppl 3):S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-S3-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Boer AG, et al. Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD007569. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007569.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paltrinieri S, et al. Return to work in European Cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(9):2983–2994. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Muijen P, et al. Predictors of return to work and employment in cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2013;22(2):144–160. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta M. A critical appraisal of evidence-based medicine: some ethical considerations. J Eval Clin Pract. 2003;9(2):111–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2003.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hees HL, et al. Towards a new definition of return-to-work outcomes in common mental disorders from a multi-stakeholder perspective. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells M, et al. Supporting 'work-related goals' rather than 'return to work' after cancer? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of 25 qualitative studies. Psychooncology. 2013;22(6):1208–1219. doi: 10.1002/pon.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiedtke C, et al. Breast cancer treatment and work disability: patient perspectives. Breast. 2011;20(6):534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greidanus MA, et al. Perceived employer-related barriers and facilitators for work participation of cancer survivors: a systematic review of employers' and survivors' perspectives. Psychooncology. 2018;27(3):725–733. doi: 10.1002/pon.4514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levack W, McPherson K, McNaughton H. Success in the workplace following traumatic brain injury: are we evaluating what is most important? Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(5):290–298. doi: 10.1080/09638280310001647615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams-Whitt K, et al. Workplace interventions to prevent disability from both the scientific and practice perspectives: a comparison of scientific literature, grey literature and stakeholder observations. J Occup Rehabil. 2016;26(4):417–433. doi: 10.1007/s10926-016-9664-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamminga SJ, et al. Employees diagnosed with cancer: current perspectives and future directions from an employer’s point of view. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;29(2):472–474. doi: 10.1007/s10926-018-9802-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiedtke CM, et al. Employers' experience of employees with cancer: trajectories of complex communication. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(5):562–577. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0626-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greidanus MA, et al. Supporting employers to enhance the return to work of cancer survivors: development of a web-based intervention (MiLES intervention) J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14:200–210. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-00844-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greidanus MA, et al. The MiLES intervention targeting employers to promote successful return to work of employees with cancer: design of a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):363. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04288-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Vet HW, et al. Measurement in Medicine. Practical Guides to Biostatistics and Epidemiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Jong M, et al. Quality of working life issues of employees with a chronic physical disease: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(1):182–196. doi: 10.1007/s10926-014-9517-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Browne JP, et al. Development of a direct weighting procedure for quality of life domains. Qual Life Res. 1997;6(4):301–309. doi: 10.1023/A:1018423124390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mokkink LB, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):539–549. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Jong M, et al. The quality of working life questionnaire for cancer survivors (QWLQ-CS): factorial structure, internal consistency, construct validity and reproducibility. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3966-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koopmans PC, et al. Recurrence of sickness absence due to common mental disorders. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011;84(2):193–201. doi: 10.1007/s00420-010-0540-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mustian KM, et al. Exercise recommendations for the management of symptoms clusters resulting from cancer and cancer treatments. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2016;32(4):383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asher A, Myers JS. The effect of cancer treatment on cognitive function. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2015;13(7):441–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duijts SF, et al. Physical and psychosocial problems in cancer survivors beyond return to work: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23(5):481–492. doi: 10.1002/pon.3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bijker R, et al. Functional impairments and work-related outcomes in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(3):429–451. doi: 10.1007/s10926-017-9736-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards PJ, et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:MR000008. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000008.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galesic M, Bosnjak M. Effects of questionnaire length on participation and indicators of response quality in a web survey. Public Opin Q. 2009;73(2):349–360. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfp031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamminga SJ, et al. The quality of working life questionnaire for cancer survivors: sufficient responsiveness for use as a patient-reported outcome measurement. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2018;27(6):e12910. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Streiner DL, Normand GR. Health Measurement Scales. A practical guide to their development and use. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terwee CB, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamminga SJ, et al. Employment and insurance outcomes and factors associated with employment among long-term thyroid cancer survivors: a population-based study from the PROFILES registry. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(4):997–1005. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1135-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taskila T, Lindbohm ML. Factors affecting cancer survivors' employment and work ability. Acta Oncol. 2007;46(4):446–451. doi: 10.1080/02841860701355048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King MT. The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(6):555–567. doi: 10.1007/BF00439229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]