Abstract

Ventricular arrhythmias are an important cause of morbidity and mortality and come in a variety of forms, from single premature ventricular complexes to sustained ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation. Rapid developments have taken place over the past decade in our understanding of these arrhythmias and in our ability to diagnose and treat them. The field of catheter ablation has progressed with the development of new methods and tools, and with the publication of large clinical trials. Therefore, global cardiac electrophysiology professional societies undertook to outline recommendations and best practices for these procedures in a document that will update and replace the 2009 EHRA/HRS Expert Consensus on Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Arrhythmias. An expert writing group, after reviewing and discussing the literature, including a systematic review and meta-analysis published in conjunction with this document, and drawing on their own experience, drafted and voted on recommendations and summarized current knowledge and practice in the field. Each recommendation is presented in knowledge byte format and is accompanied by supportive text and references. Further sections provide a practical synopsis of the various techniques and of the specific ventricular arrhythmia sites and substrates encountered in the electrophysiology lab. The purpose of this document is to help electrophysiologists around the world to appropriately select patients for catheter ablation, to perform procedures in a safe and efficacious manner, and to provide follow-up and adjunctive care in order to obtain the best possible outcomes for patients with ventricular arrhythmias.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10840-019-00664-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Catheter ablation, Clinical document, Electrical storm, Electroanatomical mapping, Electrocardiogram, Expert consensus statement, Imaging, Premature ventricular complex, Radiofrequency ablation, Ventricular arrhythmia, Ventricular tachycardia

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction .......................................in this issue

-

1.1.Document Scope and Rationale ...........in this issue

-

1.2.Methods .................................................in this issue

-

1.1.

Background ........................................in this issue

- Clinical Evaluation .............................in this issue

-

3.1.Clinical Presentation .............................in this issue

-

3.2.Diagnostic Evaluation ...........................in this issue

-

3.2.1.Resting 12-Lead Electrocardiogram ...in this issue

-

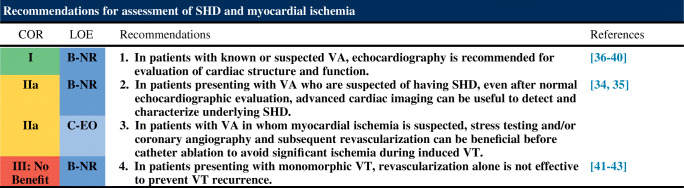

3.2.2.Assessment of Structural Heart Disease and Myocardial Ischemia ......................in this issue

-

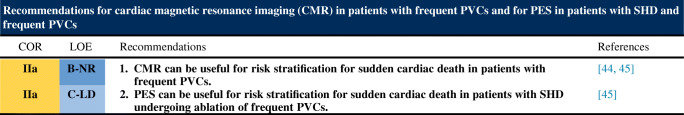

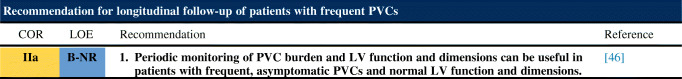

3.2.3.Risk Stratification in the Setting of Frequent Premature Ventricular Complexes ...in this issue

-

3.2.4.Longitudinal Follow-up in the Setting of Frequent Premature Ventricular Complexes ...in this issue

-

3.2.1.

-

3.1.

- Indications for Catheter Ablation .......in this issue

-

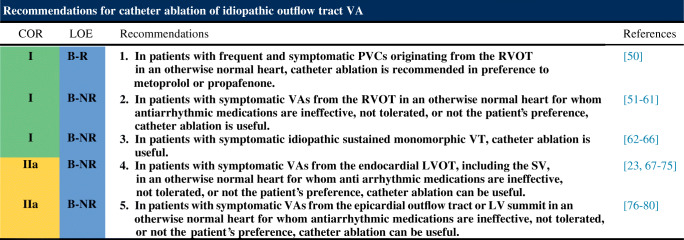

4.1.Idiopathic Outflow Tract Ventricular Arrhythmia ...

-

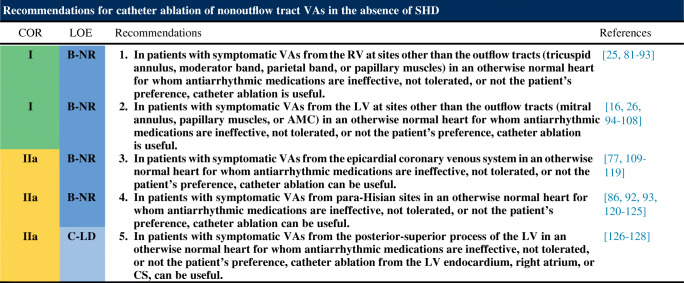

4.2.Idiopathic Nonoutflow Tract Ventricular Arrhythmia ..........................................in this issue

-

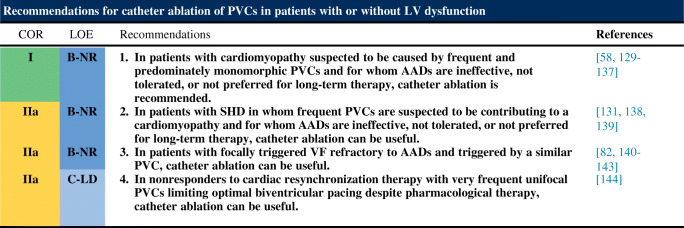

4.3.Premature Ventricular Complexes With or Without Left Ventricular Dysfunction ................in this issue

-

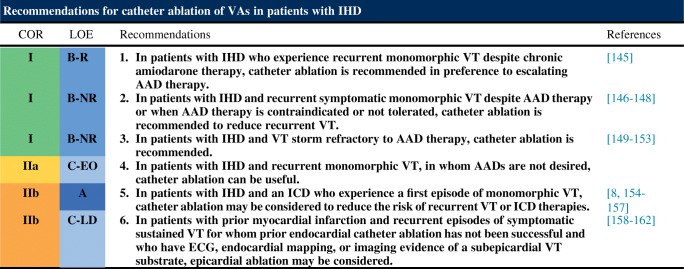

4.4.Ventricular Arrhythmia in Ischemic Heart Disease ...in this issue

-

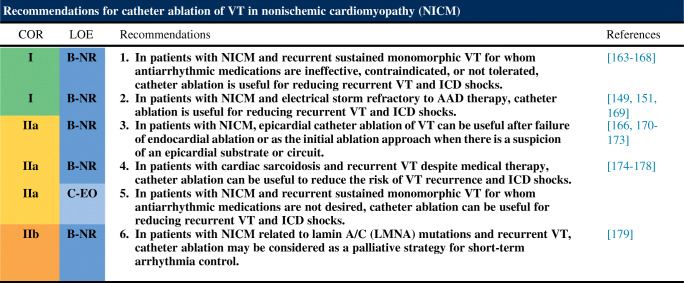

4.5.Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy .............in this issue

-

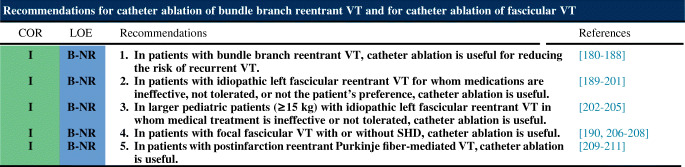

4.6.Ventricular Arrhythmia Involving the His-Purkinje System, Bundle Branch Reentrant Ventricular Tachycardia, and Fascicular Ventricular Tachycardia ...........................................in this issue

-

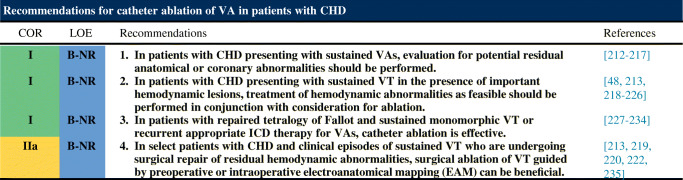

4.7.Congenital Heart Disease .....................in this issue

-

4.8.Inherited Arrhythmia Syndromes ..........in this issue

-

4.9.Ventricular Arrhythmia in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy ..................................in this issue

-

4.1.

Procedural Planning ...in this issue

- Intraprocedural Patient Care ..............in this issue

-

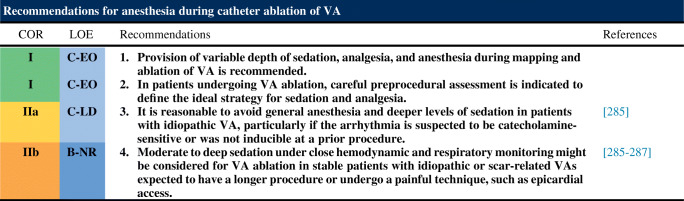

6.1.Anesthesia .............................................in this issue

-

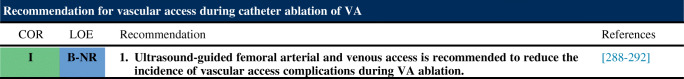

6.2.Vascular Access .....................................in this issue

-

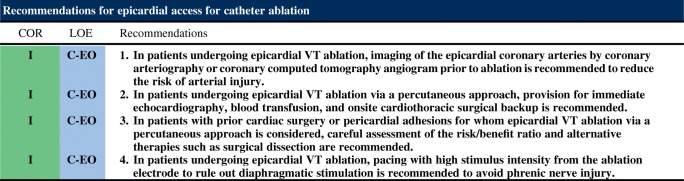

6.3.Epicardial Access ..................................in this issue

-

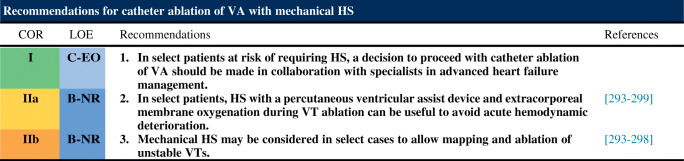

6.4.Intraprocedural Hemodynamic Support ...in this issue

-

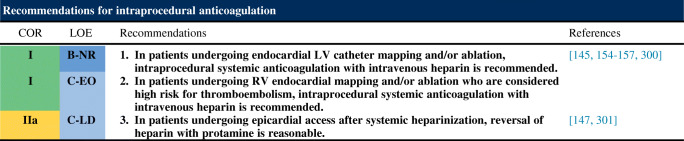

6.5.Intraprocedural Anticoagulation ...........in this issue

-

6.1.

Electrophysiological Testing ..............in this issue

- Mapping and Imaging Techniques ....in this issue

-

8.1.Overview ...............................................in this issue

-

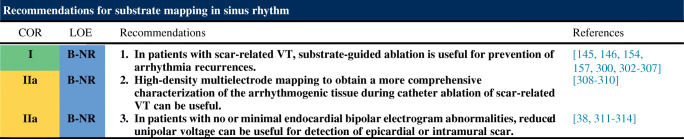

8.2.Substrate Mapping in Sinus Rhythm ...in this issue

-

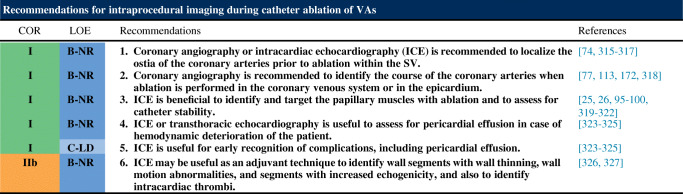

8.3.Intraprocedural Imaging During Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Arrhythmias ....................in this issue

-

8.4.Electroanatomical Mapping Systems and Robotic Navigation ...in this issue

-

8.1.

- Mapping and Ablation .......................in this issue

-

9.1.Ablation Power Sources and Techniques ..in this issue.

-

9.2.Idiopathic Outflow Tract Ventricular Arrhythmia ...in this issue

-

9.3.Idiopathic Nonoutflow Tract Ventricular Arrhythmia ...in this issue

-

9.4.Bundle Branch Reentrant Ventricular Tachycardia and Fascicular Ventricular Tachycardia ...in this issue

-

9.5.Postinfarction Ventricular Tachycardia ...in this issue

-

9.6.Dilated Cardiomyopathy ......................in this issue

-

9.7.Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy ...................................in this issue

-

9.8.Brugada Syndrome ...............................in this issue

-

9.9.Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia/Ventricular Fibrillation Triggers ..............................in this issue

-

9.10.Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy ..............................in this issue

-

9.11.Mapping and Ablation in Congenital Heart Disease ...............................................in this issue

-

9.12.Sarcoidosis ..........................................in this issue

-

9.13.Chagas Disease ...................................in this issue

-

9.14.Miscellaneous Diseases and Clinical ScenariosWith Ventricular Tachycardia ...in this issue

-

9.15.Surgical Therapy ...in this issue

-

9.16.Sympathetic Modulation ....................in this issue

-

9.17.Endpoints of Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia ........................................in this issue

-

9.1.

- Postprocedural Care .........................in this issue

-

10.1.Postprocedural Care: Access, Anticoagulation, Disposition .........................................in this issue

-

10.1.1.Postprocedural Care: Access ...in this issue

-

10.1.2.Postprocedural Care:Anticoagulation ...in this issue

-

10.1.1.

-

10.2.Incidence and Management of Complications ...in this issue

-

10.3.Hemodynamic Deterioration and Proarrhythmia ...in this issue

-

10.4.Follow-up of Patients Post Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia ......................in this issue

-

10.1.

- Training and Institutional Requirements and Competencies ..................................in this issue

-

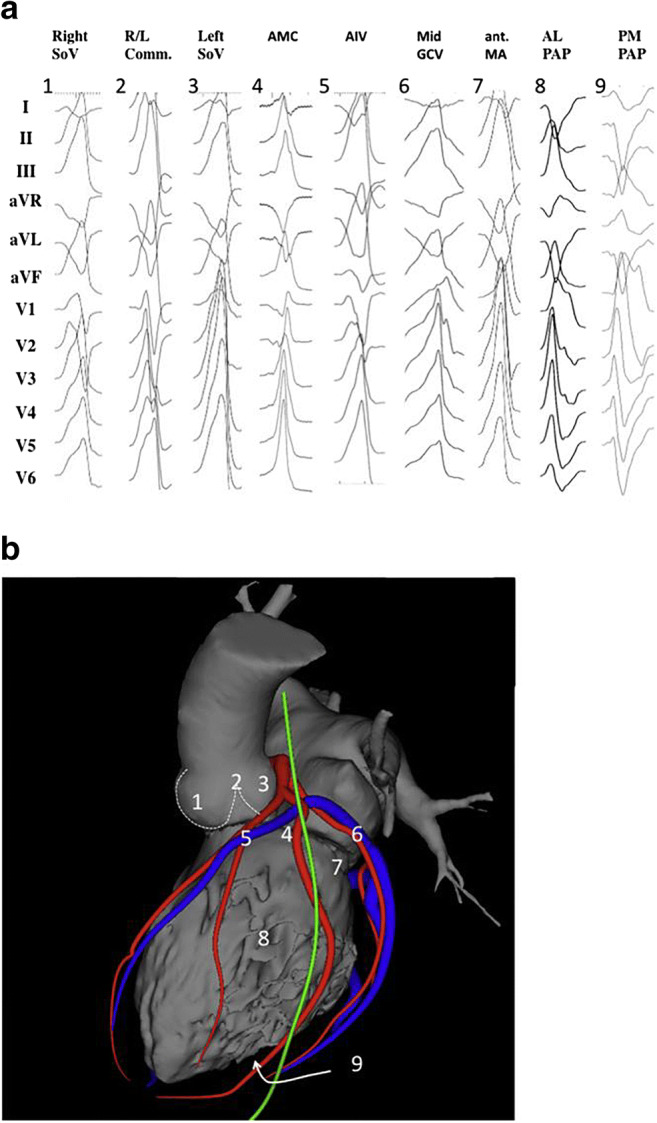

11.1.Training Requirements and Competencies for Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Arrhythmias ...in this issue

-

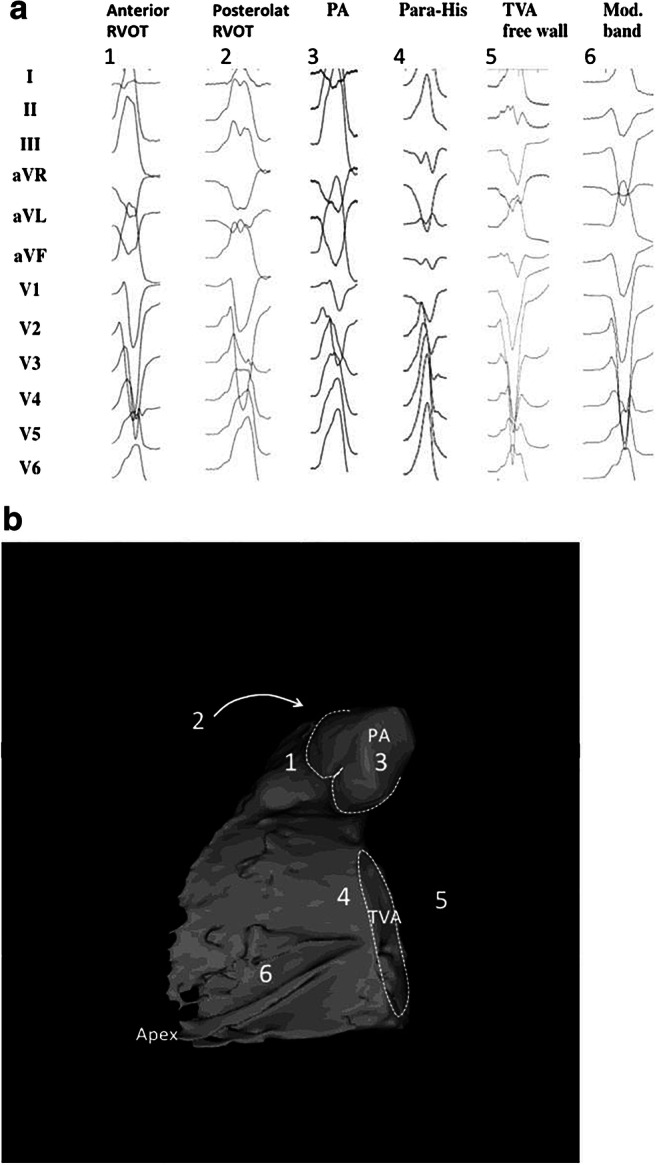

11.2.Institutional Requirements for Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia ..................in this issue

-

11.1.

Future Directions .............................in this issue

Author Disclosure Table ................in this issue

Reviewer Disclosure Table ............in this issue

Introduction

Document Scope and Rationale

The field of electrophysiology has undergone rapid progress in the last decade, with advances both in our understanding of the genesis of ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) and in the technology used to treat them. In 2009, a joint task force of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA), produced an expert consensus document that outlined the state of the field and defined the indications, techniques, and outcome measures of VA ablation [1]. In light of advances in the treatment of VAs in the interim, and the growth in the number of VA ablations performed in many countries and regions [2, 3], an updated document is needed. This effort represents a worldwide partnership between transnational cardiac electrophysiology societies, namely, HRS, EHRA, the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), and collaboration with ACC, AHA, the Japanese Heart Rhythm Society (JHRS), the Brazilian Society of Cardiac Arrhythmias (Sociedade Brasileira de Arritmias Cardíacas [SOBRAC]), and the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES). The consensus statement was also endorsed by the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS).

This clinical document is intended to supplement, not replace, the 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death [4] and the 2015 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death [5]. The scope of the current document relates to ablation therapy for VAs, from premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) to monomorphic and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) and triggers of ventricular fibrillation (VF). Due to its narrower scope, the consensus statement delves into greater detail with regard to indications and technical aspects of VA ablation than the above-mentioned guidelines.

Where possible, the recommendations in this document are evidence based. It is intended to set reasonable standards that can be applicable worldwide, while recognizing the different resources, technological availability, disease prevalence, and health care delivery logistics in various parts of the world. In addition, parts of this document, particularly Section 9, present a practical guide on how to accomplish the procedures described in a manner that reflects the current standard of care, while recognizing that some procedures are better performed, and some disease states better managed, in settings in which there is specific expertise.

Methods

The writing group was selected according to each society’s procedures, including content and methodology experts representing the following organizations: HRS, EHRA, APHRS, LAHRS, ACC, AHA, JHRS, PACES, and SOBRAC. Each partner society nominated a chair and co-chair, who did not have relevant relationships with industry and other entities (RWIs). In accordance with HRS policies, disclosure of any RWIs was required from the writing committee members (Appendix 1) and from all peer reviewers (Appendix 2). Of the 38 committee members, 17 (45%) had no relevant RWIs. Recommendations were drafted by the members who did not have relevant RWIs. Members of the writing group conducted comprehensive literature searches of electronic databases, including Medline (via PubMed), Embase, and the Cochrane Library. Evidence tables were constructed to summarize the retrieved studies, with nonrandomized observational designs representing the predominant form of evidence (Supplementary Appendix 3). Case reports were not used to support recommendations. Supportive text was drafted in the “knowledge byte” format for each recommendation. The writing committee discussed all recommendations and the evidence that informed them before voting. Initial failure to reach consensus was resolved by subsequent discussions, revisions as needed, and re-voting. Although the consensus threshold was set at 67%, all recommendations were approved by at least 80% of the writing committee members. The mean consensus over all recommendations was 95%. A quorum of two-thirds of the writing committee was met for all votes [6].

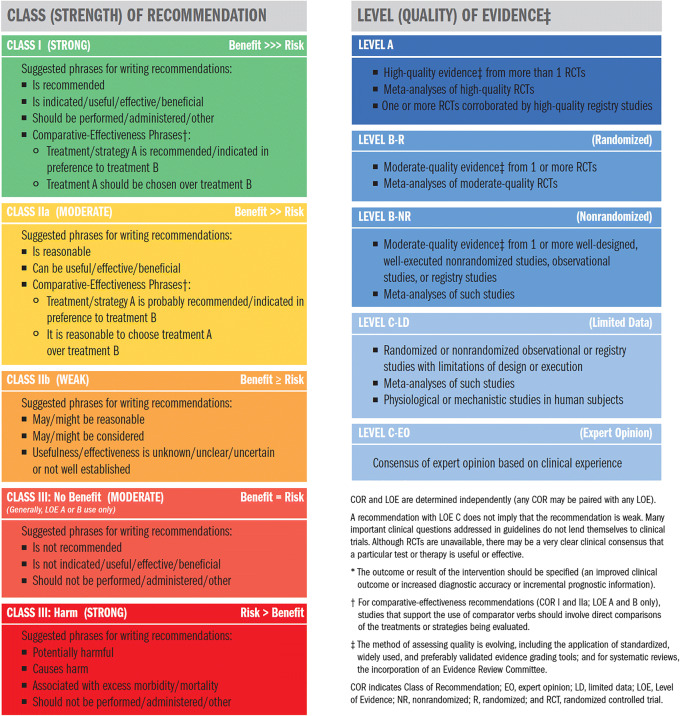

Each recommendation in this document was assigned a Class of Recommendation (COR) and a Level of Evidence (LOE) according to the system developed by ACC and AHA (Table 1) [7]. The COR denotes the strength of the recommendation based on a careful assessment of the estimated benefits and risks; COR I indicates that the benefit of an intervention far exceeds its risk; COR IIa indicates that the benefit of the intervention moderately exceeds the risk; COR IIb indicates that the benefit may not exceed the risk; and COR III indicates that the benefit is equivalent to or is exceeded by the risk. The LOE reflects the quality of the evidence that supports the recommendation. LOE A is derived from high-quality randomized controlled trials; LOE B-R is derived from moderate-quality randomized controlled trials; LOE B-NR is derived from well-designed nonrandomized studies; LOE C-LD is derived from randomized or nonrandomized studies with limitations of design or execution; and LOE C-EO indicates that a recommendation was based on expert opinion [7].

Table 1.

ACC/AHA Recommendation System: Applying Class of Recommendation and Level of Evidence to Clinical Strategies, Interventions, Treatments, and Diagnostic Testing in Patient Care*

Reproduced with permission of the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) [7]

Unique to this consensus statement is the systematic review commissioned specifically for this document as part of HRS’s efforts to adopt the rigorous methodology required for guideline development. The systematic review was performed by an experienced evidence-based practice committee based at the University of Connecticut, which examined the question of VT ablation vs control in patients with VT and ischemic heart disease (IHD) [8]. The question, in PICOT format, was as follows: In adults with history of sustained VT and IHD, what is the effectiveness and what are the detriments of catheter ablation compared with other interventions? Components of the PICOT were as follows: P = adults with history of sustained VT and IHD; I = catheter ablation; C = control (no therapy or antiarrhythmic drug [AAD]); O = outcomes of interest, which included 1) appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) therapies (ICD shock or antitachycardia pacing [ATP]), 2) appropriate ICD shocks, 3) VT storm (defined as three shocks within 24 hours), 4) recurrent VT/VF, 5) cardiac hospitalizations, and 6) all-cause mortality; and T = no time restrictions.

An industry forum was conducted to achieve a structured dialogue to address technical questions and to gain a better understanding of future directions and challenges. Because of the potential for actual or perceived bias, HRS imposes strict parameters on information sharing to ensure that industry participates only in an advisory capacity and has no role in either the writing of the document or its review.

The draft document underwent review by the HRS Scientific and Clinical Documents Committee and was approved by the writing committee. Recommendations were subject to a period of public comment, and the entire document underwent rigorous peer review by each of the participating societies and revision by the Chairs, before endorsement.

Background

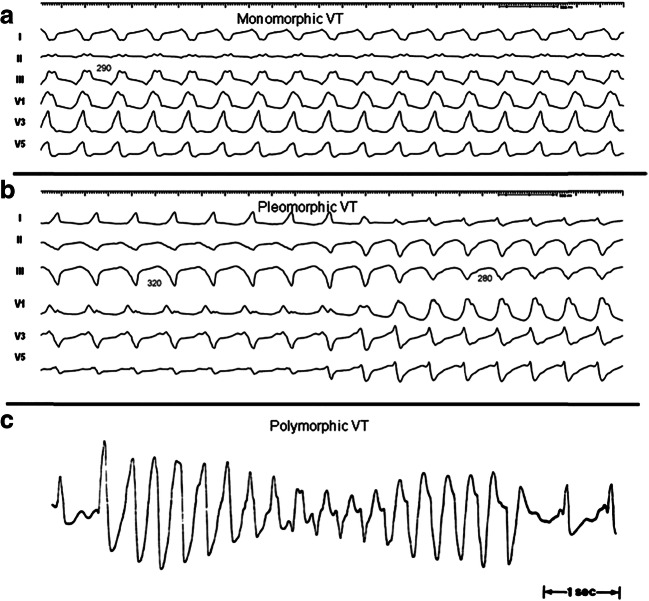

This section reviews the history of VT ablation, details the mechanisms of VT, and provides definitions of frequently used terms (Table 2), including anatomic definitions (Table 3), as well as illustrating some types of sustained VA (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Definitions

| Clinical Characteristics | |

| Clinical ventricular tachycardia (VT): VT that has occurred spontaneously based on analysis of 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) QRS morphology. | |

| Hemodynamically unstable VT: causes hemodynamic compromise requiring prompt termination. | |

| Idiopathic VT: used to indicate VT that is known to occur in the absence of clinically apparent structural heart disease (SHD). | |

| Idioventricular rhythm: three or more consecutive beats at a rate of up to 100 per minute that originate from the ventricles independent of atrial or atrioventricular (AV) nodal conduction. Although various arbitrary rates have been used to distinguish it from VT, the mechanism of ventricular rhythm is more important than the rate. Idioventricular rhythm can be qualified as “accelerated” when the rate exceeds 40 bpm. | |

| Incessant VT: continuous sustained VT that recurs promptly despite repeated intervention for termination over several hours. | |

| Nonclinical VT: VT induced by programmed electrical stimulation (PES) that has not been documented previously. | |

| Nonsustained VT: terminates spontaneously within 30 seconds. | |

| PVC: premature ventricular complex; it is an early ventricular depolarization with or without mechanical contraction. We recommend avoiding the use of the terms “ventricular premature depolarization” and “premature ventricular contraction” to standardize the literature and acknowledge that early electrical activity does not necessarily lead to mechanical contraction. | |

| Presumptive clinical VT: similar to a spontaneous VT based on rate, limited ECG, or electrogram data available from ICD interrogation, but without the 12-lead ECG documentation of spontaneous VT. | |

| PVC burden: the amount of ventricular extrasystoles, preferably reported as the % of beats of ventricular origin of the total amount of beats over a 24-hour recording period. | |

| Repetitive monomorphic VT: continuously repeating episodes of self-terminating nonsustained VT. | |

| Sustained VT: continuous VT for 30 seconds, or which requires an intervention for termination (such as cardioversion). | |

| VT: a tachycardia (rate >100 bpm) with 3 or more consecutive beats that originates from the ventricles independent of atrial or AV nodal conduction. | |

| VT storm: three or more separate episodes of sustained VT within 24 hours, each requiring termination by an intervention. | |

| VT Morphologies | |

| Monomorphic VT: a similar QRS configuration from beat to beat (Fig. 1a). Some variability in QRS morphology at initiation is not uncommon, followed by stabilization of the QRS morphology. | |

| Monomorphic VT with indeterminate QRS morphology: preferred over ventricular flutter; it is a term that has been applied to rapid VT that has a sinusoidal QRS configuration that prevents identification of the QRS morphology. | |

| Multiple monomorphic VTs: more than one morphologically distinct monomorphic VT, occurring as different episodes or induced at different times. | |

| Pleomorphic VT: has more than one morphologically distinct QRS complex occurring during the same episode of VT, but the QRS is not continuously changing (Fig. 1b). | |

| Polymorphic VT: has a continuously changing QRS configuration from beat to beat, indicating a changing ventricular activation sequence (Fig. 1c). | |

| Right bundle branch block (RBBB)- and left bundle branch block (LBBB)-like VT configurations: terms used to describe the dominant deflection in V1, with a dominant R wave described as “RBBB-like” and a dominant S wave with a negative final component in V1 described as “LBBB-like” configurations. | |

| Torsades de pointes: a form of polymorphic VT with continually varying QRS complexes that appear to spiral around the baseline of the ECG lead in a sinusoidal pattern. It is associated with QT prolongation. | |

| Unmappable VT: does not allow interrogation of multiple sites to define the activation sequence or perform entrainment mapping; this could be due to hemodynamic intolerance that necessitates immediate VT termination, spontaneous or pacing-induced transition to other morphologies of VT, or repeated termination during mapping. | |

| Ventricular fibrillation (VF): a chaotic rhythm defined on the surface ECG by undulations that are irregular in both timing and morphology, without discrete QRS complexes. | |

| PVC Morphologies | |

| Monomorphic PVC: PVCs felt reasonably to arise from the same focus. Slight changes in QRS morphology due to different exit sites from the same focus can be present. | |

| Multiple morphologies of PVC: PVCs originating from several different focal locations. | |

| Predominant PVC morphology: the one or more monomorphic PVC morphologies occurring most frequently and serving as the target for ablation. | |

| Mechanisms | |

| Focal VT: a point source of earliest ventricular activation with a spread of activation away in all directions from that site. The mechanism can be automaticity, triggered activity, or microreentry. | |

| Scar-related reentry: arrhythmias that have characteristics of reentry that originate from an area of myocardial scar identified from electrogram characteristics or myocardial imaging. Large reentry circuits that can be defined over several centimeters are commonly referred to as “macroreentry.” |

AV atrioventricular, ECG electrocardiogram, ICD implantable cardioverter defibrillator, LBBB left bundle branch block, PES programmed electrical stimulation, PVC premature ventricular complex, RBBB right bundle branch block, SHD structural heart disease, VT ventricular tachycardia

Table 3.

Anatomical terminology

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| RV inflow | The part of the right ventricle (RV) containing the tricuspid valve, chordae, and proximal RV. |

| RV outflow tract (RVOT) | The conus or infundibulum of the RV, derived from the bulbus cordis. It is bounded by the supraventricular crest and the pulmonic valve. |

| Tricuspid annulus | Area immediately adjacent to the tricuspid valve, including septal, free wall, and para-Hisian regions. |

| Moderator band | A muscular band in the RV, typically located in the mid to apical RV, connecting the interventricular septum to the RV free wall, supporting the anterior papillary muscle. It typically contains a subdivision of the right bundle branch (RBB). |

| RV papillary muscles | Three muscles connecting the RV myocardium to the tricuspid valve via the tricuspid chordae tendineae, usually designated as septal, posterior, and anterior papillary muscles. The septal papillary muscle is closely associated with parts of the RBB. |

| Supraventricular crest | Muscular ridge in the RV between the tricuspid and pulmonic valves, representing the boundary between the conus arteriosus and the rest of the RV. The exact components and terminology are controversial; however, some characterize it as being composed of a parietal band that extends from the anterior RV free wall to meet the septal band, which extends from the septal papillary muscle to meet it. |

| Pulmonary valves | The pulmonic valve includes three cusps and associated sinus, variously named right, left, and anterior; or anterolateral right, anterolateral left, and posterior sinuses. The posterior-right anterolateral commissure adjoins the aorta (junction of the right and left aortic sinuses). Muscle is present in each of the sinuses, and VA can originate from muscle fibers located within or extending beyond the pulmonary valve apparatus. |

| Sinuses of Valsalva (SV), aortic cusps, aortic commissures | The right (R), left (L), and noncoronary aortic valve cusps are attached to the respective SV. The left sinus of Valsalva (LSV) is posterior and leftward on the aortic root. The noncoronary sinus of Valsalva (NCSV) is typically the most inferior and posterior SV, located posterior and rightward, superior to the His bundle, and anterior and superior to the paraseptal region of the atria near the superior AV junctions, typically adjacent to atrial myocardium. The right sinus of Valsalva (RSV) is the most anterior cusp and may be posterior to the RVOT infundibulum. VAs can also arise from muscle fibers at the commissures (connections) of the cusps, or from myocardium accessible to mapping and ablation from this location, especially from the RSV/LSV junction. |

| LV outflow tract (LVOT) | The aortic vestibule, composed of an infra-valvular part, bounded by the anterior mitral valve leaflet, but otherwise not clearly distinguishable from the rest of the LV; the aortic valve; and a supra-valvular part. |

| LV ostium | The opening at the base of the LV to which the mitral and aortic valves attach. |

| Aortomitral continuity (AMC); aortomitral curtain, or mitral-aortic intervalvular fibrosa | Continuation of the anteromedial aspect of the mitral annulus to the aortic valve; a curtain of fibrous tissue extending from the anterior mitral valve leaflet to the left and noncoronary aortic cusps. The AMC is connected by the left and right fibrous trigones to ventricular myocardium, the right fibrous trigone to the membranous ventricular septum. |

| Mitral valve annulus | Area immediately adjacent to the mitral valve. This can be approached endocardially, or epicardially, either through the coronary venous system or percutaneously. |

| LV papillary muscles | Muscles connecting the mitral valve chordae tendineae to the LV, typically with posteromedial and anterolateral papillary muscles. Papillary muscle anatomy is variable and can have single or multiple heads. |

| LV false tendon (or LV moderator band) | A fibrous or fibromuscular chord-like band that crosses the LV cavity, attaching to the septum, papillary muscles, trabeculations, or free wall of the LV. They may contain conduction tissue and may impede catheter manipulation in the LV. |

| Posterior-superior process | The posterior-superior process of the left ventricle (LV) is the most inferior and posterior aspect of the basal LV, posterior to the plane of the tricuspid valve. VAs originating from the posterior-superior process of the LV can be accessed from the right atrium, the LV endocardium, and the coronary venous system. |

| Endocardium | Inner lining of the heart. |

| Purkinje network | The specialized conduction system of the ventricles, which includes the His bundle, RBB and left bundle branches (LBB), and the ramifications of these, found in the subendocardium. The Purkinje system can generate focal or reentrant VTs, typically manifesting Purkinje potentials preceding QRS onset. |

| Interventricular septum | Muscular wall between the LV and RV. |

| Membranous ventricular septum | The ventricular septum beneath the RSV and NCSV, through which the penetrating His bundle reaches the ventricular myocardium. |

| LV summit | Triangular region of the most superior part of the LV epicardial surface bounded by the left circumflex coronary artery, the left anterior descending artery, and an approximate line from the first septal coronary artery laterally to the left AV groove. The great cardiac vein (GCV) bisects the triangle. An area superior to the GCV is considered to be inaccessible to catheter ablation due to proximity of the coronary arteries and overlying epicardial fat. |

| Crux of the heart (crux cordis) | Epicardial area formed by the junction of the AV groove and posterior interventricular groove, at the base of the heart, approximately at the junction of the middle cardiac vein and coronary sinus (CS) and near the origin of the posterior descending coronary artery. |

| Epicardium | The outer layer of the heart—the visceral layer of the serous pericardium. |

| Epicardial fat | Adipose tissue variably present over the epicardial surface around coronary arteries, LV apex, RV free wall, left atrial appendage, right atrial appendage, and AV and interventricular grooves. |

| Pericardial space or cavity | The potential space between the parietal and visceral layers of serous pericardium, which normally contains a small amount of serous fluid. This space can be accessed for epicardial procedures. |

| Parietal pericardium | The layer of the serous pericardium that is attached to the inner surface of the fibrous pericardium and is normally apposed to the visceral pericardium, separated by a thin layer of pericardial fluid. |

| Fibrous pericardium | Thick membrane that forms the outer layer of the pericardium. |

| Subxiphoid area | Area inferior to the xiphoid process; typical site for percutaneous epicardial access. |

| Phrenic nerve | The right phrenic nerve lays along the right atrium and does not usually pass over ventricular tissue. The course of the left phrenic nerve on the fibrous pericardium can be quite variable and may run along the lateral margin of the LV near the left obtuse marginal artery and vein; inferior, at the base of the heart; or anterior over the sternocostal surface over the L main stem coronary artery or left anterior descending artery. |

| Coronary sinus (CS) and branches | The CS and its branches comprise the coronary venous system with the ostium of the CS opening into the right atrium. Tributaries of the CS, which runs along the left AV groove, may be used for mapping. These include the anterior interventricular vein (AIV), which arises at the apex and runs along the anterior interventricular septum, connecting to the GCV that continues in the AV groove to the CS; the communicating vein located between aortic and pulmonary annulus; various posterior and lateral marginal branches or perforator veins; and the middle cardiac vein that typically runs along the posterior interventricular septum from the apex to join the CS or empty separately into the right atrium. The junction of the GCV and the CS is at the vein or ligament of Marshall (or persistent left superior vena cava, when present), and the valve of Vieussens (where present). |

Anatomical terminology [9–17]. See also Figs. 3, 4, 7, and 8

AIV anterior interventricular vein, AMC aortomitral continuity, AV atrioventricular, CS coronary sinus, GCV great cardiac vein, LBB left bundle branch, LSV left sinus of Valsalva, LV left ventricle, LVOT left ventricular outflow tract, NCSV noncoronary sinus of Valsalva, RBB right bundle branch, RSV right sinus of Valsalva, RV right ventricle, RVOT right ventricular outflow tract, SV sinus of Valsalva, VA ventricular arrhythmia, VT ventricular tachycardia

Fig. 1.

Monomorphic (a), pleomorphic (b), and polymorphic (c) VT. Reproduced with permission of the Heart Rhythm Society from Aliot et al. EHRA/HRS expert consensus on catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 2009;6:886–933. VT = ventricular tachycardia

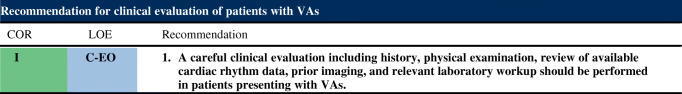

Clinical Evaluation

This section discusses clinical presentations of patients with VAs and their workup as it pertains to documentation of arrhythmias and appropriate testing to assess for the presence of SHD.

Clinical Presentation

Diagnostic Evaluation

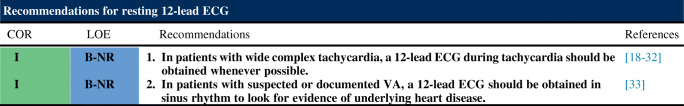

Resting 12-Lead Electrocardiogram

Assessment of Structural Heart Disease and Myocardial Ischemia

Risk Stratification in the Setting of Frequent Premature Ventricular Complexes

Longitudinal Follow-up in the Setting of Frequent Premature Ventricular Complexes

Indications for Catheter Ablation

Following are the consensus recommendations for catheter ablation of VAs organized by underlying diagnosis and substrate. These recommendations are each assigned a COR and an LOE according to the current recommendation classification system [47]. In drafting each of these recommendations, the writing committee took into account the published literature in the specific area, including the methodological quality and size of each study, as well as the collective clinical experience of the writing group when published data were not available. Implicit in each recommendation are several points: 1) the procedure is being performed by an electrophysiologist with appropriate training and experience in the procedure and in a facility with appropriate resources; 2) patient and procedural complexity vary widely, and some patients or situations merit a more experienced operator or a center with more capabilities than others, even within the same recommendation (eg, when an epicardial procedure is indicated and the operator or institution has limited experience with this procedure, it might be preferable to refer the patient to an operator or institution with adequate experience in performing epicardial procedures); 3) the patient is an appropriate candidate for the procedure, as outlined in Section 5, recognizing that the level of patient suitability for a procedure will vary widely with the clinical scenario; and 4) the patient’s (or designee’s) informed consent, values, and overall clinical trajectory are fundamental to a decision to proceed (or not) with any procedure. Therefore, in some clinical scenarios, initiation or continuation of medical therapy instead of an ablation procedure may be the most appropriate option, even when a class 1 recommendation for ablation is present. There may also be scenarios not explicitly covered in this document, and on which little or no published literature is available, in which the physician and patient must rely solely on their own judgment.

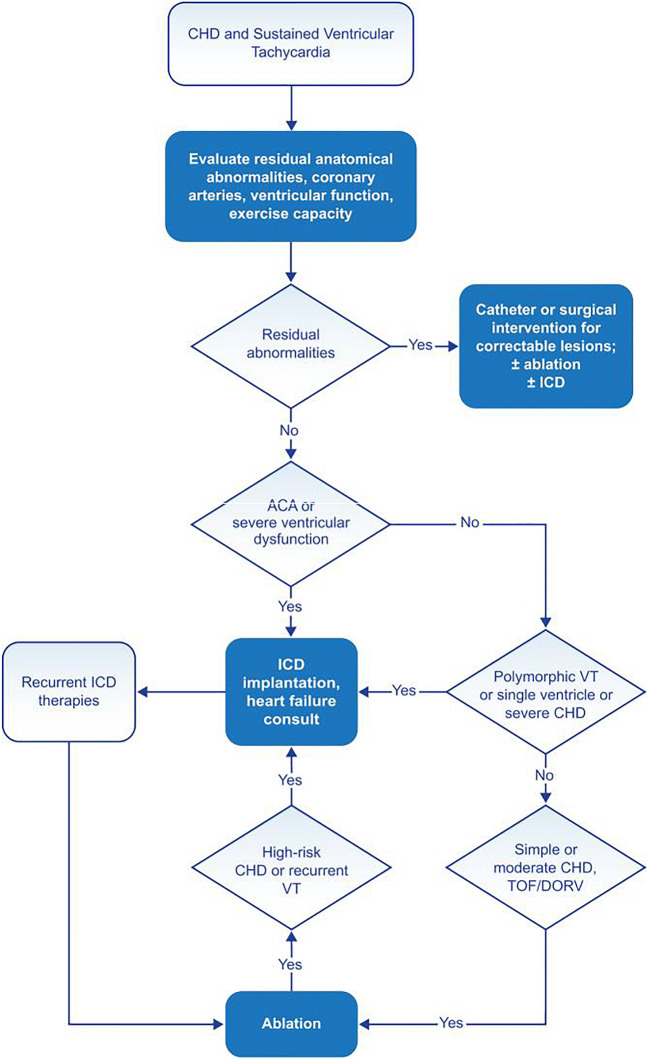

Figure 2 provides an overview of care for the patient with congenital heart disease (CHD) and VA.

Fig. 2.

Congenital heart disease and sustained VT. For further discussion of ICD candidacy, please see PACES/HRS Expert Consensus Statement on the Recognition and Management of Arrhythmias in Adult Congenital Heart Disease [48] and 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS Focused Update of the 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities [49]. ACA = aborted cardiac arrest; CHD = congenital heart disease; DORV = double outlet right ventricle; ICD = implantable cardioverter defibrillator; TOF = tetralogy of Fallot; VT = ventricular tachycardia

Idiopathic Outflow Tract Ventricular Arrhythmia

Idiopathic Nonoutflow Tract Ventricular Arrhythmia

Premature Ventricular Complexes With or Without Left Ventricular Dysfunction

Ventricular Arrhythmia in Ischemic Heart Disease

Nonischemic Cardiomyopathy

Ventricular Arrhythmia Involving the His-Purkinje System, Bundle Branch Reentrant Ventricular Tachycardia, and Fascicular Ventricular Tachycardia

Congenital Heart Disease

Inherited Arrhythmia Syndromes

Ventricular Arrhythmia in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Procedural Planning

This section includes preprocedural risk assessment (Table 4), preprocedural patient preparation, and preprocedural arrhythmia documentation with a focus on the regionalizing information of the ECG regarding the origin of VAs (Figs. 3 and 4). Furthermore, the capabilities of multimodality imaging in localizing the arrhythmogenic substrate are discussed in detail. Topics including the required equipment, personnel, and facility are detailed in this section.

Table 4.

The PAAINESD Score, developed to predict the risk of periprocedural hemodynamic decompensation

| Variable | Points |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary disease (COPD) | 5 |

| Age >60 | 3 |

| General anesthesia | 4 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 6 |

| NYHA class III/IV | 6 |

| EF <25% | 3 |

| VT storm | 5 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 |

The PAAINESD Score, developed to predict the risk of periprocedural hemodynamic decompensation, has values that range from 0 to 35 points (or 0 to 31 [PAINESD] when the modifiable intraprocedural variable “general anesthesia” is excluded) (Santangeli et al. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8:68–75)

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, EF ejection fraction, NYHA New York Heart Association, VT ventricular tachycardia

Fig. 3.

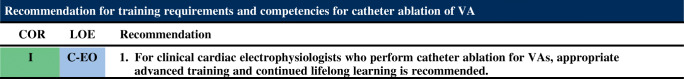

Examples of 12-lead ECGs of premature ventricular complexes from different LV sites, as corroborated by successful focal ablation. a shows 12-lead ECG patterns of common ventricular arrhythmia origins in patients without SHD [1–9] from the left ventricle. All leads are displayed at the same amplification and sweep speed. These locations are illustrated in b based on 3D reconstruction of a cardiac computed tomography using the MUSIC software that was developed at the University of Bordeaux. The reconstruction shows an anterolateral view of the left ventricle, aorta, and left atrium. Also shown are the coronary arteries (red), the coronary venous system (blue), and the phrenic nerve (green). AIV = anterior interventricular vein; AL PAP = anterolateral papillary muscle; AMC = aortomitral continuity; ECG = electrocardiogram; GCV = great cardiac vein; ant. MA = anterior mitral valve annulus; PM PAP = posteromedial papillary muscle; R/L = right-left; SHD = structural heart disease; SoV = sinus of Valsalva

Fig. 4.

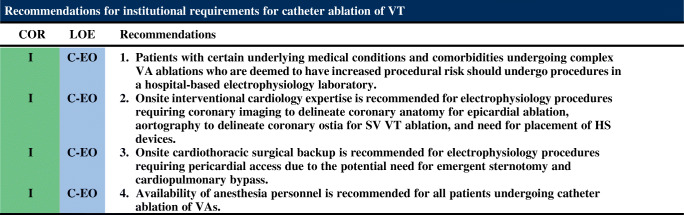

Examples of 12-lead ECGs of premature ventricular complexes from different right ventricular sites, as corroborated by successful focal ablation. All leads are displayed at the same amplification and sweep speed. a shows the 12-lead ECG pattern of common origins of right ventricular arrhythmias in patients without SHD [1–6]. The locations are detailed in a 3D reconstruction of the computed tomography using the MUSIC software that was developed at the University of Bordeaux. The reconstruction shown in b illustrates the septal view of the right ventricle. Indicated are the pulmonary artery, the tricuspid valve annulus, and the right ventricular apex. ECG = electrocardiogram; PA = pulmonary artery; RVOT= right ventricular outflow tract; SHD = structural heart disease; TVA = tricuspid valve annulus

Intraprocedural Patient Care

Important aspects regarding intraprocedural sedation and its potential problems are highlighted in this section. Furthermore, vascular access, epicardial access with its many potential complications are discussed in detail, as well as anticoagulation and the indications for the use of hemodynamic support (HS) during VT ablation procedures.

Anesthesia

Vascular Access

Epicardial Access

Intraprocedural Hemodynamic Support

Intraprocedural Anticoagulation

Electrophysiological Testing

The benefits and limitations of PES are detailed in this section.

Mapping and Imaging Techniques

Overview

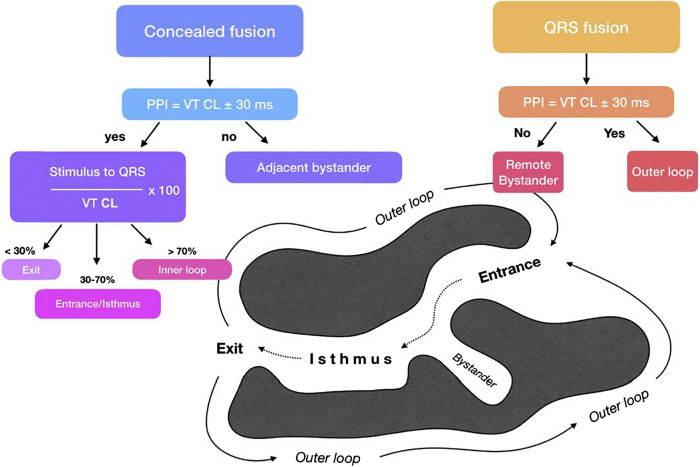

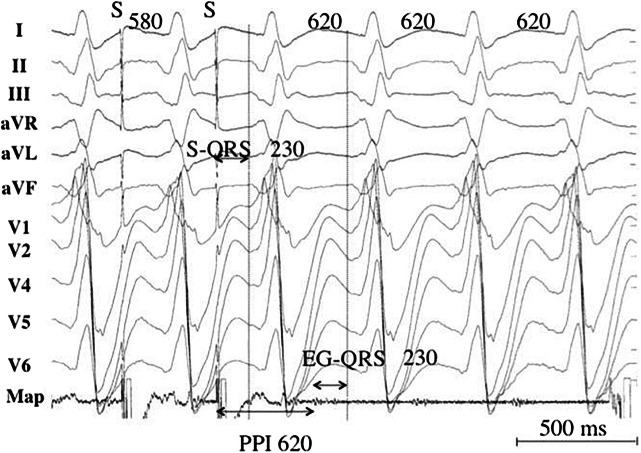

Activation mapping with multipolar catheters, entrainment mapping (Figs. 5 and 6), and pace mapping are the main techniques used to map VAs. This section reviews these techniques including the technique of substrate mapping aiming to identify the arrhythmogenic substrate in sinus rhythm. Furthermore, intraprocedural imaging as it pertains to procedural safety and to identification of the arrhythmogenic substrate is reviewed in this section.

Fig. 5.

Entrainment responses from components of reentrant VT circuit. CL = cycle length; PPI = postpacing interval; VT = ventricular tachycardia. Adapted with permission from Elsevier (Stevenson et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;29:1180–1189)

Fig. 6.

Pacing from the protected isthmus of a VT circuit. Entrainment mapping during VT. The VT CL is 620 ms, and pacing is performed at a CL of 580 ms. A low-voltage electrogram is located in diastole on the recordings of the ablation catheter (Map). The stimulus-QRS interval is 230 ms and matches with the electrogram-QRS interval. The postpacing interval is equal to the VT CL. The stimulus-QRS/VT CL ratio is 0.37, indicating that the catheter is located in the common pathway. CL = cycle length; PPI = postpacing interval; VT = ventricular tachycardia

Substrate Mapping in Sinus Rhythm

Intraprocedural Imaging During Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Arrhythmias

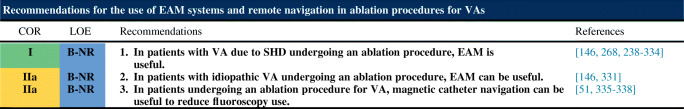

Electroanatomical Mapping Systems and Robotic Navigation

Mapping and Ablation

This section is designed as a “how-to” section that details the procedural steps of VT ablation in different patient populations ranging from ablation of PVCs in patients without heart disease to ablation of VT/VF in patients with different types of SHD (Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 and Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8). Bullet points summarize the key points in this section.

Fig. 7.

Anatomical boundaries of the LV summit, with the inaccessible [1] and accessible [2] parts. Shown are the left anterior descending artery (LAD), the circumflex artery (Cx), the great cardiac vein (GCV), the anterior interventricular vein (AIV), and the first and second diagonal branch of the LAD (D1, D2)

Fig. 8.

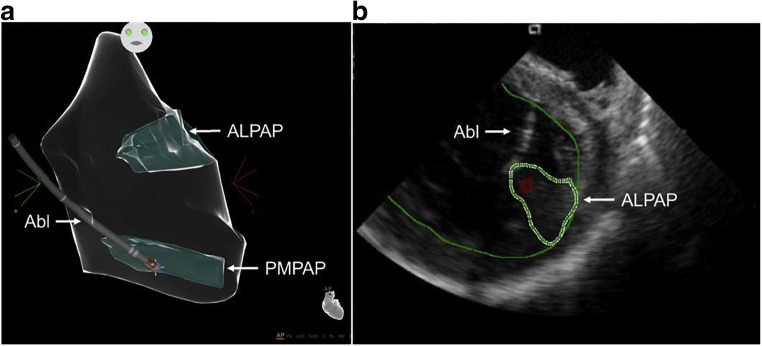

Intraprocedural imaging during ablation of papillary muscle arrhythmias. a Anatomical map of the left ventricle (CARTO, Biosense Webster) showing contact of the ablation catheter (Abl) with the posteromedial papillary muscle (PMPAP). b Intracardiac echocardiogram showing real-time visualization of the ablation catheter during ablation on the anterolateral papillary muscle (ALPAP)

Fig. 9.

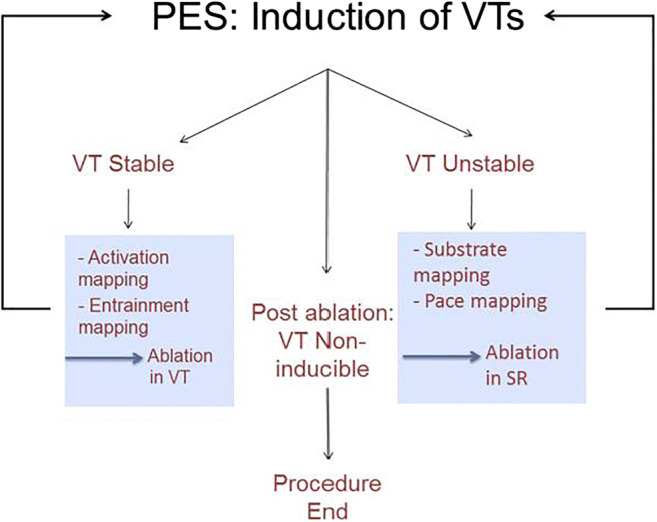

Overview of the workflow for catheter ablation of VT in patients with IHD. Not all of these steps might be required, and steps can be performed in a different sequence. For instance, repeat VT induction can be deferred in patients with hemodynamic instability. In addition, the operator might have to adapt to events that arise during the case, for instance, to take advantage of spontaneous initiation of stable VT during substrate mapping and switch to activation mapping. IHD = ischemic heart disease; PES = programmed electrical stimulation; SR = sinus rhythm; VT = ventricular tachycardia

Fig. 10.

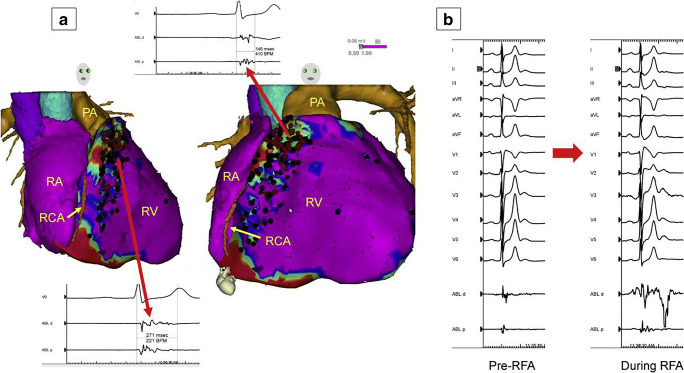

Epicardial substrate ablation in a patient with Brugada syndrome and appropriate ICD shocks for VF. Image integration of a preacquired CT with the electroanatomical epicardial substrate map is shown in (A). Purple represents bipolar voltage >1.5 mV. Fractionated potentials (arrows) are tagged with black dots, and a representative example is displayed. Widespread fractionated potentials were recorded from the epicardial aspect of the RVOT extending down into the basal RV body. Ablation lesions are tagged with red dots. Some fractionated potentials could not be ablated due to the proximity of the acute marginal branches of the right coronary artery. Panel (B) shows the significant transient accentuation of the Brugada ECG pattern during the application of radiofrequency energy at one of these sites. CT = computed tomography; ECG = electrocardiogram; ICD = implantable cardioverter defibrillator; PA = pulmonary artery; RA = right atrium; RCA = right coronary artery; RFA = radiofrequency ablation; RV = right ventricle; RVOT = right ventricular outflow tract; VF = ventricular fibrillation

Fig. 11.

Right ventricular voltage maps from cases of moderate (upper row) and advanced (lower row) arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) are shown. Purple represents a voltage >1.5 mV in the bipolar maps (left and right) and >5.5 mV in the unipolar maps (center); red represents a voltage <0.5 mV in the bipolar maps and <3.5 mV in the unipolar maps. Moderate ARVC is defined as having a bipolar/unipolar low-voltage area ratio of <0.23 and is associated with epicardial arrhythmogenic substrate area (ASA) (defined by the presence of electrograms with delayed components of >10 cm2. Advanced ARVC displays a bipolar/unipolar endocardial low-voltage area of ≥0.23, which is associated with an epicardial arrhythmogenic substrate area of ≤10 cm2. Adapted with permission from Oxford University Press (Berruezo et al. Europace 2017;19:607–616)

Fig. 12.

Anatomical isthmuses (AI) in repaired tetralogy of Fallot according to the surgical approach and variation of the malformation. RV = right ventricular; TA = tricuspid annulus; VSD = ventricular septal defect

Table 5.

Types of bundle branch reentrant tachycardia

| Type A | Type B (Interfascicular tachycardia) | Type C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECG morphology | LBBB pattern | RBBB pattern | RBBB pattern |

| Anterograde limb | RBB | LAF or LPF | LBB |

| Retrograde limb | LBB | LPF or LAF | RBB |

LAF left anterior fascicle, LBB left bundle branch, LBBB left bundle branch block, LPF left posterior fascicle, RBB right bundle branch, RBBB right bundle branch block

Table 6.

Fascicular ventricular tachycardias

| I. Verapamil-sensitive fascicular reentrant VT | |

| 1. Left posterior type | |

| i. Left posterior septal fascicular reentrant VT | |

| ii. Left posterior papillary muscle fascicular reentrant VT | |

| 2. Left anterior type | |

| i. Left anterior septal fascicular reentrant VT | |

| ii. Left anterior papillary muscle fascicular reentrant VT | |

| 3. Upper septal type | |

| II. Nonreentrant fascicular VT |

VT ventricular tachycardia.

Table 7.

Select recent radiofrequency catheter ablation studies in patients post myocardial infarction with a focus on substrate-based ablation strategies

| Study | N | EF (%) | Prior CABG (%) | Inclusion | Access mapping catheter | Mapping strategy | Ablation strategy | Procedural endpoint | RF time procedural duration complications | VT recurrence and burden (follow-up) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Jais et al. (2012) [339] Two centers observational |

70 | 35 ± 10 | NR |

1) Sustained VT resistant to AAD therapy and requiring external cardioversion or ICD therapies 2) SHD with ischemic or nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy Exclusions: 1) VA attributable to an acute or reversible cause 2) Repetitive PVCs or nonsustained VT without sustained VT |

Retrograde in 61 pts (87%) Transseptal in 32 pts (46%); epicardial access in 21 pts (31%) Dual access encouraged 3.5-mm external irrigated ablation catheter; multielectrode mapping catheter in 50% endocardial procedures and in all epicardial procedures |

1) PES and activation mapping of induced stable VTs 2) Substrate mapping for LAVAs — sharp high-frequency electrograms often of low amplitude, occurring during or after the far-field ventricular electrogram, sometimes fractionated or multicomponent, poorly coupled to the rest of the myocardium |

1) Ablation of LAVA in SR 2) Ablation of tolerated VTs guided by entrainment and activation mapping 3) Remapping (in stable patients) with further ablation if residual LAVA or persistent inducibility |

1) Complete LAVA elimination — achieved in 47 of 67 pts with LAVA (70.1%) 2) Noninducibility — achieved in 70%, similar if LAVA eliminated or not |

RF time 23 ± 11 min Procedure time 148 ± 73 min Complications 6 pts (8.6%): tamponade or bleeding managed conservatively (3), RV perforation requiring surgical repair (1); 3 pts died within 24 h due to low-flow state (2) plus arrhythmia recurrence (1), PEA (1) |

Combined endpoint of VT recurrence or death occurred in 39 pts (55.7%); 45% of pts with LAVA elimination and 80% of those without VT recurrence in 32 (46%); 32% of pts with LAVA elimination and 75% of those without 7 cardiac deaths (10%) over 22 months of median follow-up |

|

Di Biase et al. (2015) [302] VISTA trial Multicenter RCT |

118 |

Group 1 33 ± 14 Group 2 32 ± 10 |

34% |

1) Post-MI 2) Recurrent stable AAD refractory VT (symptomatic or requiring ICD therapy) Exclusion: syncope, cardiac arrest, prior failed ablation, renal failure,end-stage heart failure |

Endocardial Epicardial when clinical VTs were inducible after endocardial ablation + no CABG Group 1: 11.7% Group 2: 10.3% 3.5-mm tip |

1) Substrate mapping (BV ≤1.5 mV) + Group 1 2) PES and activation mapping/pace mapping for clinical and stable nonclinical VT (unstable VT not targeted) |

Group 1: Clinical VT ablation, linear lesion to transect VT isthmus Group 2: Extensive substrate ablation targeting any abnormal potential (=fractionated and/or LP) |

Group 1: Noninducibility of clinical VT — achieved in 100% Group 2: 1) Elimination of abnormal potentials 2) No capture from within the scar (20 mA) 3) Noninducibility of clinical VT — achieved in 100% |

Group 1: RF time 35 ± 27 min Procedural time 4.6 ± 1.6 h Group 2: RF time 68 ± 27 min (P < .001) Procedural time 24.2 ± 1.3 h (P = .13) Complications 5% |

VT recurrence at 12 months Group 1: 48.3% Group 2: 15.5% P < .001 Mortality at 12 months Group 1: 15% Group 2: 8.6% P = .21 |

|

Tilz et al. (2014) [340] Single center observational |

12 12/117 pts with post-MI VT |

32 ± 13 | — |

1) Presence of a circumscribed dense scar (BV <1.5 mV, area <100 cm2) 2) Recurrent unmappable VT 3) Post-MI Exclusion: patchy scar/multiple scars |

Endocardial 3.5-mm tip |

1) PES 2) Substrate mapping: area of BV <1.5 mV + double, fractionated or LP 3) PES after ablation |

Circumferential linear lesion along BZ (BV <1.5 mV) to isolate substrate |

1) Lack of abnormal EGMs within area 2) No capture within area — achieved in 50% 3) Max. 40 RF lesion Noninducibility of any VT (no predefined endpoint) —observed in 92% |

RF time 53 ± 15 min Procedure time 195 ± 64 min No complication |

VT recurrence 33% Median follow-up 497 days |

|

Tzou et al. (2015) [341] Two centers observational |

44 Post-MI 32 44/566 pts with SHD |

31 ± 13 | — |

1) SHD 2) AAD refractory VT 3) Intention to achieve core isolation |

Endocardial Epicardial post-MI 6% 3.5-mm tip Selected patients: multi-electrode catheters for exit block evaluation |

1) BV mapping 2) PES 3) Activation mapping 4) Substrate mapping Dense scar BV <0.5 mV; BZ BV 0.5–1.5 mV/voltage channels/ fractionated/LP; pace-match, S-QRS >40 ms 5) PES after core isolation |

1) Circumferential linear lesion to isolate core (=confluent area of BV <0.5 mV area and regions with BV <1 mV harbouring VT-related sites 2) Targeting fractionated and LP within core 3) Targeting VT-related sites outside core (2 and 3 in 59%) |

1) No capture of the ventricle during pacing inside core 2) Dissociation of isolated potentials — core isolation achieved in 70% post-MI 3) Noninducibility —achieved in 84% |

RF lesions 111 ± 91 Procedure time 326 ± 121 min Complications 2.2% No death |

VT recurrence 14% Follow-up 17.5 ± 9 months |

|

Silberbauer et al. (2014) [342] One center observational |

160 |

28 ± 9.5 inducible after RFCA 34 ± 9.2 endpoint reached |

22.5% |

1) Post-MI 2) AAD refractory VT 3) First VT ablation at the center |

Endocardial Combined endoepicardial (20%) — Clinical findings — Prior ablation — Research protocol 3.5-mm tip/4-mm tip |

1) Substrate mapping: BV <1.5 mV + LP (=continuous, fragmented bridging to components after QRS offset/inscribing after QRS, no voltage cutoff) + early potentials (EP = fragmented <1.5 mV) Pace-match 2) PES 3) Activation mapping 4) PES after substrate ablation |

1) Ablation mappable VT 2) Ablation of all LP LP present at baseline Endocardium 100/160 pts Epicardium 19/32 pts |

1) Abolition of all LP — achieved at endocardium in 79 pts (49%), at epicardium 12/32 pts (37%) 2) Noninducibility of any VT — achieved in 88% |

RF time endocardial median ≈25 min epicardial ≈6 min Procedure time Median 210–270 min Complications 3.1% In-hospital mortality 2.5% |

VT recurrence 32% after median 82 (16–192) days VT recurrence according to endpoint 1+2 achieved (16.4%) Endpoint 2 achieved (46%) No endpoint achieved (47.4%) |

|

Wolf et al. (2018) [343] One center observational |

159 | 34 ± 11 | 25% |

1) Post-MI 2) First VT ablation 3) Recurrent, AAD refractory episodes VT |

Endocardial Combined endoepicardial 27% — Epicardial access was encouraged — Epicardial ablation 27/46 pts 3.5-mm tip (70 pts) Multielectrode catheters (89 pts) |

1) PES 2) Activation mapping 3) Substrate mapping: BV mapping (<1.5 mV) + LAVA (=sharp high-frequency EGMs, possibly of low amplitude, distinct from the far-field EGM occurring anytime during or after the far-field EGM 4) PES |

1) Ablation of mappable VT 2) Ablation of LAVA (until local no capture) LAVA present at baseline Endocardium 141/157 pts Epicardium 36/46 pts |

1) Abolition of LAVA — achieved in 93/146 pts (64%) 2) Noninducibility — achieved in 94/110 tested pts |

RF time 36 ± 20 min Procedure time 250 ± 78 min Complications 7.5% (4 surgical interventions) Procedure-related mortality 1.3% |

VT-free survival 55% during 47 months (33–82) Outcome according to endpoints: LAVA abolished vs not abolished 63% vs 44% VT-free survival at 1 year 73% |

|

Berruezo et al. (2015) [344] One center observational |

101 Post-MI 75 |

36 ± 13 | — | 1) Scar-related VT |

Endocardial Combined endoepicardial (27/101 pts, among post-MI not provided) — Endo no substrate/suggestive epi — CE-MRI — VT ECG 3.5-mm tip |

1) Substrate mapping: BV (<1.5 mV) + EGMs with delayed components: identification of entrance (shortest delay) of conducting channels 2) PES 3) Activation mapping + pace-match |

1) Scar dechanneling targeting entrance 2) Short linear lesions (eg, between scar and mitral annulus) 3) Ablation of VT-related sites — performed in 45% |

1) Scar dechanneling — Achieved in 85 pts (84.2%) — Noninducible after 1) 55 pts (54.5%) 2) Noninducibility —achieved in 78% |

RF time 24 ± 10 min only scar dechanneling (31 ± 18 min + additional RFCA) Procedure time 227 ± 69 min Complications 6.9% No death |

VT recurrence 27% after a median follow-up of 21 months (11–29) 1-year VT-free survival according to endpoint: scar dechanneling complete vs incomplete (≈82% vs ≈65%) |

|

Porta-Sánchez et al. (2018) [345] Multicenter observational |

20 | 33 ± 11 | — |

1) Post-MI 2) Recurrent VT |

Endocardial 3.5-mm tip 4 pts Multielectrode catheters 16 pts |

1) Substrate mapping: annotation of LP (=fractionated/isolated after QRS offset) and assessment if LP showed additional delay of >10 ms after RV extrastimuli (S1 600 ms, S2 VERP + 20 ms) defined as DEEP 2) PES 3) Additional mapping |

1) Targeting areas with DEEP 2) Ablation of VT-related sites discretion of operator |

1) Noninducibility— achieved in 80% after DEEP ablation — Remains 80% after additional ablation in those inducible |

RF time 30.6 ± 21.4 min Procedure time and complications not reported |

VT recurrence 25% at 6-month follow-up |

|

de Riva et al. (2018) [346] One center observational |

60 | 33 ± 12 | 30% |

1) Post-MI 2) Sustained VT |

Endocardial Epicardial 10% — Endocardial failure — Epicardial substrate suspected 3.5-mm tip catheter |

1) PES 2) Substrate mapping: systematic assessment of presumed infarct area independent of BV during SR and RV extrastimuli Pacing (S1 500 ms, S2 VRP + 50ms): EDP (evoked delayed potentials) = low voltage (<1.5 mV) EGM with conduction delay >10 ms or block in response to S2 3) Activation and pace mapping |

1) Targeting EDPs only 2) Ablation of VT-related sites based on activation/pace mapping |

1) Elimination of EDPs — achieved in all 2) Noninducibility of targeted VT (fast VT with VTCL≈VERP not targeted) — Achieved in 67% after EDP ablation — Achieved in 90% after additional ablation |

RF time 15 min (10–21) Procedure time 173 min (150–205) Complications 3.3% One procedure-related death |

VT recurrence 22% at median follow-up of 16 months (8–23) Subgroup of patients with EDPs in normal-voltage areas at baseline (hidden substrate) compared to historical matched group without EDP mapping VT-free survival at 1 year 89% vs 73% |

Included studies: post myocardial infarction (or data for patients post myocardial infarction provided)

AAD antiarrhythmic drug, BV bipolar voltage, BZ border zone, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, CE-MRI contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, DC delayed component, DEEP decremental evoked potential, ECG electrocardiogram, EDP evoked delayed potential, EF ejection fraction, EGM electrogram, ICD implantable cardioverter defibrillator, LAVA local abnormal ventricular activity, MI myocardial infarction, PEA pulseless electrical activity, PES programmed electrical stimulation, pts patients, PVC premature ventricular complex, RCT randomized controlled trial, RF radiofrequency, RFCA radiofrequency catheter ablation, RV right ventricle, SHD structural heart disease, SR sinus rhythm, VT ventricular tachycardia

Table 8.

Catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias in cardiac sarcoidosis

| Study | N | LVEF, % | Concurrent immunosuppressive therapy, n (%) | VTs induced, mean ± SD | Mapping, Endo n/Epi n | Ablation, Endo n/Epi n | Patients undergoing repeated procedures, n (%) | VT Recurrence, n (%) | VT Burden decrease, n (%) | Major complications | Follow-up, months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koplan et al. [347] | 8 | 35 ± 15 | 5 (63) | 4 ± 2 | 6/2 | 8/2 | 1 (13) | 6 (75) | 4 (44) | NR | 6 |

| Jefic et al. [174] | 9 | 42 ± 14 | 8 (89) | 5 ± 7 | 8/1 | NR | 3 (33) | 4 (44) | 9 (100) | NR | 20 |

| Naruse et al. [175] | 14 | 40 ± 12 | 12 (86) | 3 ± 1 | 14/0 | 14/0 | 4 (29) | 6 (43) | NR | NR | 33 |

| Dechering et al. [348] | 8 | 36 ± 19 | NR | 4 ± 2 | NR | NR | NR | 1 (13) | 7 (88) | NR | 6 |

| Kumar et al. [176] | 21 | 36 ± 14 | 12 (57) | Median 3 (range 1–8) | 21/8 | 21/5 | 11 (52) | 15 (71) | 16 (76) | 4.7% | 24 |

| Muser et al. [177] | 31 | 42 ± 15 | 22 (71) | Median 3 (range 1–5) | 31/11 | 31/8 | 9 (29) | 16 (52) | 28 (90) | 4.5% | 30 |

LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, N number, NR not reported, VT ventricular tachycardia

Ablation Power Sources and Techniques

Key Points

An impedance drop ≥10 ohms or a contact force ≥10 g is commonly used as a target for radiofrequency energy delivery.

The use of half normal saline generates larger ablation lesions but can result in steam pops.

Simultaneous bipolar or unipolar ablation can result in larger ablation lesions.

Cryoablation can be beneficial for achieving more stable contact on the papillary muscles.

Ethanol ablation can generate lesions in areas where the arrhythmogenic substrate cannot be otherwise reached, provided that suitable target vessels are present.

Stereotactic radiotherapy is an emerging alternative to ablation, requiring identification of a region of interest that can be targeted prior to the radiation treatment.

Idiopathic Outflow Tract Ventricular Arrhythmia

Key Points

The RVOT, pulmonary arteries, SVs, LV epicardium and endocardium contain most of the outflow tract arrhythmias.

Activation mapping and pace mapping can be used to guide ablation in the RVOT.

Imaging of coronary artery ostia is essential before ablation in the aortic SVs.

The LV summit is a challenging site of origin, often requiring mapping and/or ablation from the RVOT, LVOT, SVs, coronary venous system, and sometimes the epicardial space.

Deep intraseptal VA origins can be challenging to reach.

Idiopathic Nonoutflow Tract Ventricular Arrhythmia

Key Points

VAs originating from the papillary muscles can be challenging due to multiple morphologies of the VA and the difficulty in achieving and maintaining sufficient contact during ablation.

VAs originate in LV papillary muscles more often than in RV papillary muscles; they more often originate from the posteromedial than the anterolateral papillary muscle and occur more often at the tip than at the base.

Pace mapping is less accurate than in other focal VAs.

ICE is particularly useful for assessing contact and stability.

Cryoablation can also aid in catheter stability during lesion delivery.

Bundle Branch Reentrant Ventricular Tachycardia and Fascicular Ventricular Tachycardia

Key Points

Bundle branch reentry can occur in a variety of patients in whom the conduction system can be affected, including patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), valvular heart disease, myocardial infarction, myotonic dystrophy, Brugada syndrome, and ARVC, among others.

Ablation of either the right or left bundle branch eliminates bundle branch reentrant ventricular tachycardia (BBRVT) but does not eliminate other arrhythmic substrates.

A correct diagnosis of BBRVT is crucial and should employ established criteria prior to ablation of either of the bundle branches.

Ablation of the AV node does not cure BBRVT.

Ablation of either bundle branch does not cure interfascicular VT.

For posterior fascicular VTs, the P1 potential is targeted during VT; if P1 cannot be identified or VT is not tolerated, an anatomical approach can be used.

Purkinje fibers can extend to the papillary muscles, and these can be part of the VT circuit.

For anterior fascicular VTs, the P1 potential is targeted with ablation.

Focal nonreentrant fascicular VT is infrequent and can occur in patients with IHD; however, it cannot be induced with programmed stimulation, and the target is the earliest Purkinje potential during VT.

Postinfarction Ventricular Tachycardia

Key Points

In cases of multiple inducible VTs, the clinical VT should be preferentially targeted.

Elimination of all inducible VTs reduces VT recurrence and is associated with prolonged arrhythmia-free survival.

For tolerated VTs, entrainment mapping allows for focal ablation of the critical isthmus.

For nontolerated VTs, various ablation strategies have been described, including targeting abnormal potentials, matching pace mapping sites, areas of slow conduction, linear lesions, and scar homogenization.

Imaging can be beneficial in identifying the arrhythmogenic substrate.

Epicardial ablation is infrequently required, but epicardial substrate is an important reason for VT recurrence after VT ablation in patients with prior infarcts.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Key Points

Identifying the location and extent of scarring on CMR is beneficial in procedural planning and has improved the outcomes of ablation in patients with DCM.

The ablation strategy is similar to postinfarction VT.

An intramural substrate is more frequently encountered in DCM than in postinfarction patients and requires a different ablation strategy than for patients with either epicardial or endocardial scarring.

Epicardial ablation is beneficial if the scar is located in the epicardium of the LV free wall.

For intramural circuits involving the septum, epicardial ablation is not beneficial.

In the absence of CMR, unipolar voltage mapping has been described as a method to indicate a deeper-seated scar.

Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Key Points

Polymorphic VT and VF are the most common VAs in HCM; monomorphic VT is less common.

The arrhythmogenic substrate in HCM often involves the septum but can extend to the epicardium, often necessitating combined endocardial and epicardial ablation procedures to eliminate the VT.

VT associated with apical aneurysms is often ablated endocardially.

Brugada Syndrome

Key Points

PVC-triggered VF or polymorphic VT are the most prevalent VAs that motivate device therapy in patients with Brugada syndrome.

Monomorphic VT is less frequent but can be caused by BBRVT in patients with Brugada syndrome.

The arrhythmogenic substrate is located in the RV epicardium and can be demonstrated by sodium channel blockers.

Ablation targets include fractionated prolonged electrograms on the epicardial aspect of the RV.

Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia/Ventricular Fibrillation Triggers

Key Points

Recurrent PVC-induced VF is most often triggered by PVCs originating from Purkinje fibers, located in the RVOT, the moderator band, or the LV.

Patients with a single triggering PVC are better ablation candidates; however, there are often multiple triggers.

Patients with healed myocardial infarction often require extensive ablation of the Purkinje fiber system within or at the scar border.

Ischemia should be ruled out as a trigger for VF prior to ablation.

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy

Key Points

The arrhythmogenic substrate in ARVC is located in the epicardium and can involve the endocardium in advanced stages.

The most commonly affected areas are the subtricuspid and RV outflow regions.

LV involvement is not uncommon.

Endocardial-epicardial ablation is often required and results in higher acute success and lower recurrence rates compared with endocardial ablation alone.

Conventional mapping and ablation techniques, including entrainment mapping of tolerated VT, pace mapping, and substrate ablation, are used.

Mapping and Ablation in Congenital Heart Disease

Key Points

Patients with a VT substrate after congenital heart defect surgery include those with repaired tetralogy of Fallot, repaired ventricular septal defect, and repaired d-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA), as well as Ebstein’s anomaly among other disease processes.

VT isthmuses are often located between anatomical barriers and surgical incisions or patch material.

An anatomical isthmus can be identified and targeted during sinus rhythm.

For tolerated VTs, entrainment mapping is the method of choice for identifying critical components of the reentry circuit.

Sarcoidosis

Key Points

The arrhythmogenic substrate in cardiac sarcoidosis is often intramurally located but can include the endocardium and epicardium.

A CMR is beneficial in planning an ablation procedure in cardiac sarcoidosis.

The arrhythmogenic substrate can be complex and can include areas of active inflammation and chronic scarring.

The VT recurrence rate after ablation is high.

Chagas Disease

Key Points

The pathogenesis of Chagas disease is poorly understood but often results in an inferolateral LV aneurysm.

The arrhythmogenic substrate is located intramurally and on the epicardial surface, often necessitating an epicardial ablation procedure.

Miscellaneous Diseases and Clinical Scenarios With Ventricular Tachycardia

Key Points

Lamin cardiomyopathy often has a poor prognosis, progressing to end-stage heart failure.

VT ablation is challenging due to intramural substrates

VT recurrence rate is high after ablations.

VT in patients with noncompaction tends to originate from regions of noncompacted myocardium where scar can be identified in the midapical LV.

VT ablation in patients with LV assist device can be challenging due to the limitation of preprocedural imaging, and the electromagnetic noise generated by the LV assist device.

Surgical Therapy

Key Points

Surgery-facilitated access to the epicardium via a limited subxiphoid incision can be helpful in the case of adhesions.

Cryoablation via thoracotomy is possible for posterolateral substrates and via sternotomy for anterior substrates.

Sympathetic Modulation

Key Points

Sympathetic modulation targeting the stellate ganglia by video-assisted thoracoscopy may be considered for failed VT ablation procedures or VF storms.

A temporary effect can be obtained with the percutaneous injection or infusion of local anesthetics.

Endpoints of Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia

Key Points

Noninducibility of VT by PES after ablation is a reasonable endpoint and predictor for VT recurrence after VT ablation in patients with SHD.

Due to the limitations of programmed stimulation, endpoints other than noninducibility have been described, including elimination of excitability, elimination of late potentials or local abnormal ventricular activity, dechanneling, substrate homogenization, core isolation, image-guided ablation, and anatomically fixed substrate ablation.

Postprocedural Care

Access-related issues, anticoagulation (Table 9), and complications (Table 10), as well as the management thereof, are reviewed in this section. Furthermore, assessment of outcomes and determinants of outcomes are detailed (Fig. 13).

Table 9.

Postprocedural care in prospective studies of ventricular tachycardia catheter ablation

| Study | Postprocedure NIPS | AAD type | AAD duration | Follow-up | ICD programming | Anticoagulation postablation | Bleeding and thromboembolic events (ablation arm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calkins 2000 [349] | No | Patients were continued on the type of antiarrhythmic therapy they had received before ablation. | At least the first 3 months after hospital discharge | Evaluation at 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months after ablation | Not specified | Not specified | Four of 146 (2.7%) stroke or TIA, 4 (2.7%) episodes of pericardial tamponade |

| SMASH-VT 2007 [154] | No | No patient received an AAD (other than beta blockers) before the primary endpoint was reached. | N/A | Followed in the ICD clinic at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months; echocardiography at 3 and 12 months | Not specified | Oral anticoagulation 4–6 weeks, aspirin if fewer than 5 ablation lesions | One pericardial effusion without tamponade, managed conservatively; 1 deep venous thrombosis |

| Stevenson 2008 [146] | No | The previously ineffective AAD was continued for the first 6 months, after which time drug therapy was left to the discretion of the investigator. | Six months, after which time drug therapy was left to the discretion of the investigator | Echocardiogram and neurologist examination before and after ablation; office visit at 2 and 6 months, with ICD interrogation where applicable | Not specified | Three months with either 325 mg/day aspirin or warfarin if ablation had been performed over an area over 3 cm in length | Vascular access complications in 4.7%; no thromboembolic complications |

| Euro-VT 2010 [147] | No | Drug management during follow-up was at the discretion of the investigator. | Drug management during follow-up was at the discretion of the investigator. | At 2, 6, and 12 months, with ICD interrogation where applicable | Investigators were encouraged to program ICD detection for slow VT for at least 20 beats or 10 seconds to allow nonsustained VT to terminate before therapy is triggered. | Not specified | No major bleeding or thromboembolic complications |

| VTACH 2010 [155] | No | Discouraged | Discouraged | Every 3 months from ICD implantation until completion of the study | VF zone with a cutoff rate of 200–220 bpm and a VT zone with a cutoff CL of 60 ms above the slowest documented VT and ATP followed by shock | Not specified | One transient ischemic ST-segment elevation; 1 TIA |

| CALYPSO 2015 [156] | No | Discouraged | Discouraged | At 3 and 6 months | Investigators were required to ensure that VT detection in the ICD is programmed at least 10 beats below the rate of the slowest documented VT. | At the discretion of the treating physician, anticoagulation recommended with aspirin or warfarin for 6–12 weeks | |

| Marchlinski 2016 [148] | Not required | Not dictated by the study protocol | Not dictated by the study protocol | At 6 months and at 1, 2, and 3 years | Not dictated by the study protocol | Per clinical conditions and physician preference | Cardiac perforation (n = 1), pericardial effusion (n = 3) |

| VANISH 2016 [145] | No | Continued preprocedure antiarrhythmic medications | Not specified | A 3-month office visit, echo, ICD check; a 6-month office visit, ICD check; every 6 months thereafter, an office visit, ICD check | VT detection at 150 bpm or with a 10–20 bpm margin if the patient was known to have a slower VT. ATP was recommended in all zones. The protocol was modified to recommend prolonged arrhythmia detection duration for all patients. | Intravenous heparin (without bolus) 6 hours after sheath removal, then warfarin if substrate-mapping approach used or if more than 10 minutes of RF time | Major bleeding in 3 patients; vascular injury in 3 patients; cardiac perforation in 2 patients |

| SMS 2017 [157] | No | At the discretion of the investigator | At the discretion of the investigator | At 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, and at 3- or 6-month intervals until completion of the study or until 33-month follow-up was reached | VF zone at 200–220 bpm, detection 18 of 24 beats, shock only; VT zone detection at least 16 consecutive beats, ATP, and shocks. Where VT rates were exclusively >220 bpm, VT zone at 160–180 bpm was recommended; where VT rates were <220 bpm, VT zone with a CL 60 ms above the slowest VT was recommended | Aspirin (250 mg/day) or warfarin as necessitated by the underlying heart disease | Two tamponades requiring pericardiocentesis |

AAD antiarrhythmic dug, ATP antitachycardia pacing, CL cycle length, ICD implantable cardioverter defibrillator, NIPS noninvasive programmed stimulation, RF radiofrequency, TIA transient ischemic attack, VF ventricular fibrillation, VT ventricular tachycardia

Table 10.

Major complications of ventricular arrhythmia ablation in patients with structural heart disease

| Complication | Incidence | Mechanisms | Presentation | Prevention | Treatment | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | 0%–3% | VT recurrence, heart failure, complications of catheter ablation | Not applicable | Correct electrolyte disturbances and optimize medical status before ablation | — | [146, 154, 155, 300, 350] |

| Long-term mortality | 3%–35% (12–39 months of follow-up) | VT recurrence and progression of heart failure | Cardiac nonarrhythmic death (heart failure) and VT recurrence | Identification of patients with indication for heart transplantation | — | [146, 154, 155, 300] |

| Neurological complication (stroke, TIA, cerebral hemorrhage) | 0%–2.7% | Emboli from left ventricle, aortic valve, or aorta; cerebral bleeding | Focal or global neurological deficits | Careful anticoagulation control; ICE can help detection of thrombus formation, and of aortic valve calcification; TEE to assess aortic arch | Thrombolytic therapy | [146, 154, 155, 300, 350] |

| Pericardial complications: cardiac tamponade, hemopericardium, pericarditis | 0%–2.7% | Catheter manipulation, RF delivery, epicardial perforation | Abrupt or gradual fall in blood pressure; arterial line is recommended in ablation of complex VT | Contact force can be useful, careful in RF delivery in perivenous foci and RVOT | Pericardiocentesis; if necessary, surgical drainage, reversal heparin; steroids and colchicine in pericarditis | [146, 154, 155, 300, 350] |

| AV block | 0%–1.4% | Energy delivery near the conduction system | Fall in blood pressure and ECG changes | Careful monitoring when ablation is performed near the conduction system; consider cryoablation | Pacemaker; upgrade to a biventricular pacing device might be necessary | [146, 154, 300, 350] |

| Coronary artery damage/MI | 0.4%–1.9% | Ablation near coronary artery, unintended coronary damage during catheter manipulation in the aortic root or crossing the aortic valve | Acute coronary syndrome; confirmation with coronary catheterization | Limit power near coronary arteries and avoid energy delivery <5 mm from coronary vessel; ICE is useful to visualize the coronary ostium | Percutaneous coronary intervention | [146, 154, 155, 300, 350] |

| Heart failure/pulmonary edema | 0%–3% | External irrigation, sympathetic response due to ablation, and VT induction | Heart failure symptoms | Urinary catheter and careful attention to fluid balance and diuresis, optimize clinical status before ablation, reduce irrigation volume if possible (decrease flow rates or use closed irrigation catheters) | New/increased diuretics | [146, 154, 155, 300] |

| Valvular injury | 0%–0.7% | Catheter manipulation, especially retrograde crossing the aortic valve and entrapment in the mitral valve; energy delivery to subvalvular structures, including papillary muscle | Acute cardiovascular collapse, new murmurs, progressive heart failure symptoms | Careful catheter manipulation; ICE can be useful for identification of precise location of energy delivery | Echocardiography is essential in the diagnosis; medical therapy, including vasodilators and dobutamine before surgery; IABP is useful in acute mitral regurgitation and is contraindicated in aortic regurgitation | [146, 154, 155, 300] |

| Acute periprocedural hemodynamic decompensation, cardiogenic shock | 0%–11% | Fluid overloading, general anesthesia, sustained VT | Sustained hypotension despite optimized therapy |

Close monitoring of fluid infusion and hemodynamic status -Optimize medical status before ablation -pLVAD -Substrate mapping preferred, avoid VT induction in higher-risk patients |

Mechanical HS | [146, 154, 155, 300, 351] |

| Vascular injury: hematomas, pseudoaneurysm, AV fistulae | 0%–6.9% | Access to femoral arterial and catheter manipulation | Groin hematomas, groin pain, fall in hemoglobin | Ultrasound-guided access | Ultrasound-guided compression, thrombin injection, and surgical closure | [146, 154, 155, 300, 350] |

| Overall major complications with SHD | 3.8%–11.24% | [146, 154, 155, 300, 350] | ||||

| Overall all complications | 7%–14.7% | [300, 352, 353] | ||||

AV atrioventricular, ECG electrocardiogram, HS hemodynamic support, IABP intra-aortic balloon pump, ICE intracardiac echocardiography, MI myocardial infarction, pLVAD percutaneous left ventricular assist device, RF radiofrequency, RVOT right ventricular outflow tract, SHD structural heart disease, TEE transesophageal echocardiography, TIA transient ischemic attack, VT ventricular tachycardia

Fig. 13.

Factors influencing outcomes post VA ablation. ICD = implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVAD = left ventricular assist device; VA = ventricular arrhythmia; VT = ventricular tachycardia

Postprocedural Care: Access, Anticoagulation, Disposition

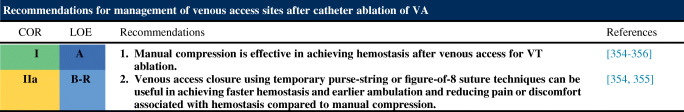

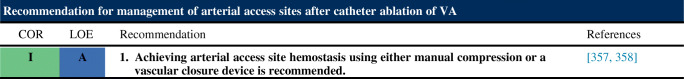

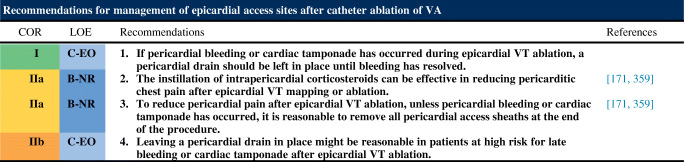

Postprocedural Care: Access

Postprocedural Care: Anticoagulation

Incidence and Management of Complications

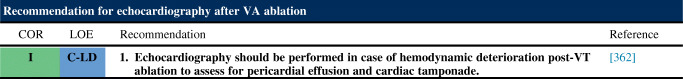

Hemodynamic Deterioration and Proarrhythmia

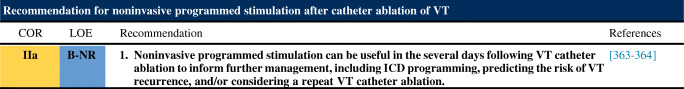

Follow-up of Patients Post Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia

Training and Institutional Requirements and Competencies

This section contains the general training and institutional requirements with an emphasis on lifelong learning, professionalism, and acquisition and maintenance of knowledge and skills. In addition, institutional requirements for specific procedures are reviewed.

Training Requirements and Competencies for Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Arrhythmias

Institutional Requirements for Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia

Future Directions