Abstract

Over the past three decades, the practice laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty has gained momentum. Mesh migration after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is an uncommon mesh-related delayed complication which is more common after transabdominal preperitoneal repair as compared to total extraperitoneal (TEP) repair. We report the first case of mesh migration into the sigmoid colon after TEP presenting 10 years after surgery. A 72-year-old male presented with left iliac fossa pain and diffuse lump. His computed tomogram scan showed sigmoid colon adherent to internal oblique at the site of hernia repair with a collection containing air specks and calcification. A colonoscopy revealed mesh within the sigmoid colon. He had to undergo a sigmoidectomy with Hartmann's surgery for the same. Here, we discuss the implicated pathophysiology, management and prevention of mesh migration after laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty with literature review.

Keywords: Laparoscopic hernia repair, mesh migration, sigmoid colon, sigmoidectomy

INTRODUCTION

Tension-free repair of inguinal hernia with the use of mesh for posterior wall reinforcement is an important step of both open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair since it decreases the chance of recurrence. Mesh-related complications occurring many years after a laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair have recently started, being reported in the literature. The more serious late mesh-related complications including contraction, erosion and migration into the adjacent organs are rare. There are rare isolated reports of complications for migrated mesh eroding into the colon. Here, we report a patient with migration of mesh into the sigmoid colon 10 years after a total extraperitoneal (TEP) repair for left inguinal hernia. Only two reports of mesh migration into the sigmoid colon after TEP have been reported previously; this is the first reported case of mesh migration into the sigmoid colon presenting 10 years after TEP.

CASE REPORT

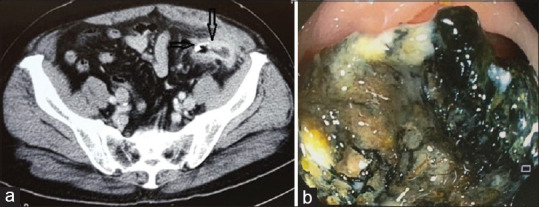

A 72-year-old male patient presented to us with complaints of dull aching pain in the left iliac fossa and constipation for 3 months. He had undergone a TEP for a left inguinal hernia 10 years ago, using a microporous polypropylene mesh and non-absorbable tackers. His comorbidities included hypertension and ischemic heart disease. On examination, he was haemodynamically stable and had a palpable diffusely tender lump in the left iliac fossa measuring around 4 cm × 3 cm. The rest of the abdomen was soft, and per rectal examination was unremarkable. Haematological and biochemical investigations were normal. A contrast-enhanced computed tomogram revealed an ill-defined hypodense collection in the left iliac fossa, abutting the left rectus abdominis and left internal oblique muscles with the loss of fat planes [Figure 1a]. There was a suspicion of communication with distal descending colon and areas of calcification [Figure 1a], and air specks were seen within the collection near the site of communication. Colonoscopy revealed a piece of mesh protruding within the lumen of the sigmoid colon occupying three-fourth of its lumen [Figure 1b]. There were isolated diverticula within the sigmoid.

Figure 1.

(a) Computed tomogram image showing sigmoid adhesion to the left internal oblique (down arrow) and calcification (right arrow). (b) Colonoscopic image showing mesh protruding within the sigmoid lumen

At exploratory laparotomy, a segment of sigmoid colon was found adherent to the abdominal wall and the area of the left internal ring [Figure 2a]. On adhesiolysis, a piece of polypropylene mesh along with metallic tacker was found exposed and penetrated into the sigmoid colon lumen from the preperitoneal space with a purulent collection of approximately 10cc around the area. The adherent segment of the sigmoid colon was resected and a Hartmann's procedure was performed. The mesh and tacks eroding into the sigmoid colon [Figure 2b] were removed, but no attempt was made to disturb medial part of the mesh incorporated in the extraperitoneal space. A lavage was given and a drain was placed in the area. The culture of the pus grew Escherichia coli sensitive to carbapenems, which was administered for 5 days. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on the 6th post-operative day. The histopathology of the specimen showed diverticular disease with perforation of the colon.

Figure 2.

(a) Intraoperative image showing sigmoid colon adherent to the mesh (down arrow). (b) Sigmoidectomy specimen with mesh and tacker (up arrow) visible at the site of perforation

DISCUSSION

Over the past three decades, the practice of laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty has gained momentum. Mesh migration after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is an uncommon mesh-related delayed complication. Late complications of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair have recently started being reported in the literature. In a review of literature from 1992 to 2018 by Gossetti et al., the most common site of mesh migration after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair was the sigmoid colon followed by the urinary bladder.[1]

Mesh infections occurring many years after inguinal hernia surgery have not been well-documented in the literature, and the pathogenesis and risk factors contributing to their development are not well understood. Direct contact between the mesh and viscera is implicated to be the cause of mesh-related visceral complications. This can occur when an inadequately fixed mesh migrates along the path of least resistance or when it is displaced by external forces (primary mesh migration). Another mechanism is when inflammatory granulation tissue at the site of the implanted mesh gradually involves the surrounding viscera through transanatomic spaces (secondary mesh migration).[2] This response can vary from person to person. In addition, sharp edges of the prosthetic mesh or tackers used for mesh fixation can cause serosal injury to viscera, initiating intra-abdominal inflammatory response and adhesions to viscera.[3] The coexistence of diverticular disease of the sigmoid may act as a trigger for the development of erosion or fistula formation.[4]

Thin devascularised peritoneal flaps can affect peritoneal closure, which may result in incomplete colonisation of mesh by mesothelial cells. This results in physical contact between the mesh and viscera, leading to chronic local inflammation.[5] This might explain why mesh migration is more common in transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) hernia repair as compared to TEP.

In our patient, the possible causes of mesh migration into the sigmoid colon could have been a missed breach in the peritoneum which resulted in contact between the sigmoid colon and mesh. Another cause could be serosal injury to the colon by tacker, eventually leading to localised inflammatory response. Sigmoid diverticulitis causing inflammation, abscess and erosion could be a possible cause of mesh migration in our patient.

The most common presentation of patients with mesh migration into the sigmoid colon is rectal bleeding, colonic obstruction and sigmoiditis [Table 1] [Supplementary File (114.4KB, pdf) ]. Our patient presented with a tender lump in the abdomen, which is an uncommon presentation. Acute inflammation and sigmoid wall thickening is a common colonoscopic finding.[6] Colonoscopy in our patient revealed mesh eroding into the sigmoid lumen.

Table 1.

Mesh migration into the sigmoid colon after laparoscopic repair - Reports from literature (January 1992-May 2018)

| Author | Duration since hernia repair | Technique | Clinical presentation | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray et al.[SF-1] | 8 months | TAPP | Colovesical fistula | Sigmoidectomy and suture repair |

| McDonald and Chung[SF-2] | 4 years | TAPP | Large bowel obstruction | Low anterior resection |

| Panzironi et al.[SF-3] | 5 years | TAPP | Large bowl obstruction | Sigmoidectomy |

| Rieger and Brundell (2002)[SF-4] | 6 years | TAPP | Colovesical fistula | N/A |

| Bonner and Prohm[SF-5] | 2 years | TAPP | Rectal bleeding | Sigmoidectomy |

| Lange et al.[SF-6] | N/A | TAPP | Rectal bleeding | Sigmoidectomy |

| Benes et al.[SF-7] | 4 months | TAPP | Rectal bleeding | Suture repair |

| 7 months | TAPP | Rectal bleeding | Suture repair | |

| 9 months | TAPP | Rectal bleeding | Sigmoidectomy | |

| Tamam et al.[SF-8] | 7 years | TEP | Colovesical fistula | Sigmoidectomy and suture repair |

| Han et al.[SF-9] | 2 months | TEP | Pelvic abscess | Sigmoidectomy |

| Karls et al.[SF-10] | 12 years | TAPP | Sigmoiditis | Sigmoidectomy |

| Degheili et al.[SF-11] | 5 months | TAPP | Scrotal fistula | Laparotomy and suture repair |

| Unlisted Authors (2015)[SF-12] | 5 years | TAPP | Colocutaneous fistula | Sigmoidectomy |

| Ramakrishnan et al.[SF-13] | 38 months | TAPP | N/A | Suture repair with the removal of mesh |

| Na et al.[SF-14] | 4 years | TAPP | Haematochezia | Sigmoidectomy |

| Ramanathan et al.[SF-15] | 7 years | TAPP | Colovesical fistula | Suture repair |

TAPP: Transabdominal preperitoneal, TEP: Total extraperitoneal, N/A: Not available, SF: Supplemetary file (114.4KB, pdf)

A definitive diagnosis of mesh migration may be difficult due to varied presentations and time to event, which can take several years after the surgery.

Surgical excision of infected mesh with resection or suture repair of involved viscera is required for the management of mesh migration. Sigmoidectomy was the most common surgery performed for mesh-related complications involving the sigmoid colon [Table 1] [Supplementary File (114.4KB, pdf) ].

It is important to avoid any contact between the mesh and peritoneum to avoid mesh migration. In TAPP repair, complete suturing of well-vascularised flap and repair of any peritoneal breech in TEPP should be ensured. The European hernia society guidelines suggest mesh fixation to be unnecessary in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair.[7] The correct choice of mesh is important as well. Macroporous, monofilament, semiabsorbable mesh should be used instead of microporous mesh.[1]

CONCLUSION

Mesh migration into the sigmoid colon is an uncommon late sequel of laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty. The definitive diagnosis of this condition may be difficult due to diverse clinical presentations and time to event, which can take up to several years. It is important for the surgeon to be aware of the detailed surgical history of the patient. The management of these cases is multidisciplinary, involving surgeon, gastroenterologist, endoscopist and radiologist. It is important to have a high index of suspicion when interpreting clinical and radiological findings. Proper surgical technique and mesh selection can help to avoid such grave mesh-related complications of inguinal hernia repair.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his name and initial will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal his identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY FILE

REFERENCES

- 1.Gossetti F, D'Amore L, Annesi E, Bruzzone P, Bambi L, Grimaldi MR, et al. Mesh-related visceral complications following inguinal hernia repair: An emerging topic. Hernia. 2019;23:699–708. doi: 10.1007/s10029-019-01905-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamamoto S, Kubota T, Abe T. A rare case of mechanical bowel obstruction caused by mesh plug migration. Hernia. 2015;19:983–5. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowbey PK, Bagchi N, Goel A, Sharma A, Khullar R, Soni V, et al. Mesh migration into the bladder after TEP repair: A rare case report. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:52–3. doi: 10.1097/01.sle.0000202185.34666.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Amore L, Gossetti F, Manto O, Negro P. Mesh plug repair: Can we reduce the risk of plug erosion into the sigmoid colon? Hernia. 2012;16:495–6. doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0921-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamy A, Paineau J, Savigny JL, Vasse N, Visset J. Sigmoid perforation, an exceptional late complication of peritoneal prosthesis for treatment of inguinal hernia. Int Surg. 1997;82:307–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ratajczak A, Kościński T, Banasiewicz T, Lange-Ratajczak M, Hermann J, Bobkiewicz A, et al. Migration of biomaterials used in gastroenterological surgery. Pol Przegl Chir. 2013;85:377–80. doi: 10.2478/pjs-2013-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, Bouillot JL, Campanelli G, Conze J, et al. European hernia society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia. 2009;13:343–403. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0529-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.