Abstract

Regulatory enzymes often have different roles in distinct subcellular compartments. Yet, most drugs indiscriminately saturate the cell. Thus, subcellular drug-delivery holds promise as a means to reduce off-target pharmacological effects. A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) sequester combinations of signaling enzymes within subcellular microdomains. Targeting drugs to these ‘signaling islands’ offers an opportunity for more precise delivery of therapeutics. Here, we review mechanisms that bestow protein kinase A (PKA) versatility inside the cell, appraise recent advances in exploiting AKAPs as platforms for precision pharmacology, and explore the impact of methodological innovations on AKAP research.

Subcellular Organization and AKAPs

Enzymes do not drift aimlessly within a cytoplasmic soup. Rather, enzymatic reactions often occur within the confines of highly organized intracellular signaling nanodomains [1]. Such enzyme compartmentalization enhances the fidelity of signal transduction events and permits the parallel processing of chemical signals within the same cell. Research efforts over the past three decades have advanced our understanding of how cells have evolved such a sophisticated local signaling machinery. Membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria and nuclei have long been appreciated as delimiting specific cell processes. Non-membrane-bound compartments have more recently gained attention. Whether referred to as membraneless organelles, phase separation, or macromolecular complexes, this emergent class of subcellular structures organizes enzymes, effectors, and substrates to enhance the relay of cellular information [2]. Scaffold and anchoring proteins maintain the integrity of these non-membrane-bound subcellular assemblies [3].

Here, we focus on AKAPs, defined by their ability to bind the regulatory (R) subunits of PKA. Each of these anchoring proteins exhibits a preference for type I and/or type II PKA and is targeted to a defined subcellular location [4,5]. As will be discussed in the proceeding sections, the members of this ever-expanding AKAP family vary in size, conformation, and ability to scaffold combinations of signaling molecules (Table 1). Concerted efforts from numerous investigators have identified over 60 AKAPs in the human genome, demonstrating the fundamental utility of PKA anchoring in cells. In this review, we explore the current understanding of how PKA signaling is diversified: first by the modular structure of its holoenzyme (i.e., the intact kinase: two catalytic subunits bound to a regulatory subunit dimer); and second by its association with distinct anchoring proteins. We then focus on the potential of AKAPs as precision tools for pharmacology and recent technological advances that reshape investigations into AKAP biology.

Table 1.

Known AKAPs.a

| Gene | Protein names | Selectivity | Cellular location | Binding partners | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKAP1 | D-AKAP1 AKAP121/149 S-AKAP84 AKAP140 |

Dual | Outer mitochondrial membrane, ER, nuclear membrane, sperm midpiece | PP1, PP2B, mRNA, sestrin2, RSK1, Src | [5,43,99,100] |

| AKAP2 | AKAP2 AKAP-KL |

Type II | Actin, plasma membrane | MYPT1, AQP0 | [4,5,14] |

| AKAP3 | AKAP3 AKAP110 FSP95 |

Dual | Axoneme, cytoplasm in spermatids | PDE4A, Gα13, BRAP2, ROPN1, SPA17, CABYR, AKAP4 | [4] |

| AKAP4 | AKAP4 AKAP82 FSC1 |

Dual | Fibrous sheath | ERK1/2, RhoA, FSIP1, FSIP2, AKAP3 | [5] |

| AKAP5 | AKAP79 AKAP150 AKAP75 AKAP5 |

Type II | Plasma membrane Recycling endosomes | PKC, CaM, PP2B, NFAT, MAGUKs, l-type Ca2+ channels, CaV3, AC5/6, TRPV1/4, Kir2.1, KCNQ2–5, TREK, β-AR | [47–53,101–105] |

| AKAP6 | mAKAP AKAP100 |

Type II | Nuclear membrane | PKA, PKCε, MEK5, ERK5, RSK3, PKD, PP2A, PP2B, PDE4D3, Epac1, HDAC4, PLCε, MEF2, NFAT, AC5 | [69,86,106] |

| AKAP7 | AKAP18 (αβγδε) AKAP15 (αβγδε) |

Type II | Plasma membrane, cytosol, vesicles, nucleus | l-type Ca2+ channels, AQP2-vesicles, PLB, SERCA2a, I-1 | [5,14,42,68] |

| AKAP8 | AKAP95 AKAP8 |

Type II | Nucleus | AMY-1, CASP3, Cx43, MCM2, RSK1, cyclinD/E, HDAC3, p16, PDE4D5/A, DPY30, p68 RNA helicase, RNA | [5,107] |

| AKAP8L | AKAP8L NAKAP95 HAP95/HA95 |

Type I, catalytic subunit | Nucleus | mTORC1, core subunits of H3K4 HMT complexes | [108] |

| AKAP9 | AKAP350 AKAP450 Yotiao CG-NAP Hyperion |

Type II | Centrosomes Golgi apparatus Synapses Plasma membrane |

PDE4D3, PKN, PKC, dynein, PP1, PP2A, pericentrin, γ-tubulin, MTCL1, CK1, Cam, CIP4, cyclin E, Cdk2, Ran, Golgin A2, myosin VI, Epac1, MAPRE1, NMDAR, KCNQ1, IP3R, AC9 | [5,109,110] |

| AKAP10 | D-AKAP2 | Dual | Endocytic vesicles | PDZK1, NHERF1/2, Rab4, Rab11 | [4,5] |

| AKAP11 | AKAP220 | Type II | Vesicles Peroxisomes Centrosome |

PP1, GSK3β, IQGAP, actin, AQP2-vesicles | [54–57] |

| AKAP12 | Gravin AKAP250 SSeCKS (mouse) |

Type II | Actin Centrosome Cytosol |

CaM, PDE4D, PKC, β-adrenergic receptors, Plk1 | [5,58] |

| AKAP13 | AKAP-Lbc Ht31 Rt31 |

Type II | Cytosol | Gα12, RhoA, PKNα, MLTK, MKK3, p38α, PKD, PKCη, SHP-2, IKKβ | [5] |

| AKAP14 | AKAP28 TAKAP80 (rat) |

Type II | Ciliary axonemes | [4] | |

| AKAP17A | AKAP17A SFRS17A |

Dual | Spliceosome, nucleus | [4] | |

| PCNT | Pericentrin Kendrin |

Type II | Centrosome | γ-tubulin, γ-TURC, PCM1, LIC, AKAP450, DISC-1, Chk1, PKCβII, BCR-Abl, CHD3, CHD4, IFT, PC2 | [4] |

| MAP2 | MAP2B; | Type II | Microtubules | Tubulin, l-type Ca2+ channels, actin, myosin VIIa, NFs, src, fyn, grb2 | [5,35] |

| MAP2D AKAP80 |

Dual | Golgi apparatus | GSK3β, vimentin, β-tubulin | ||

| PDE4DIP | PDE4DIP Myomegalin/MMGL CMYA2 |

Dual | Golgi apparatus, centrosomes | cMyBPC, troponin I, ANKRD1, CDK5RAP2, AKAP450, EB1/MAPRE1 | [111] |

| STUB1 | CHIP STUB1 |

Type II | Aquaporin2 vesicles | CDK18, aquaporin2 | [112] |

| TNNT2 | Cardiac troponin T cTnT |

Dual | Myofilaments | Actin, MORF4L2, troponin I, KDM1A | [113] |

| LDB3 | Cypher ZASP |

Type II | Sarcomeric Z-lines | PP2B, l-type Ca2+ channels | [114] |

| ACBD3 | PAP7 | Type I | Golgi apparatus, mitochondria | Giantin, Golgin160, Golgin45, Numb, PI4KB, TUG, Htt, PBR, 3A, SseF/G, DMT1, PARP1, SREBP1, FAPP2, TBC1D22A, PPM1L | [4] |

| ITGA4 | α4-integrin | Type I | Plasma membrane | β-integrins, Hsp90 | [4] |

| C2orf88 | smAKAP | Type I | Plasma membrane | [27] | |

| SPHKAP | SKIP | Type I | Mitochondrial intermembrane space | Sphingosine kinase type I, ChChd3 | [5,28,29] |

| MYRIP | MyRIP | Type II | Perinuclear | MyosinVa, myosinVIIa, Rab27a, actin | [4,115] |

| MYO7A | Myosin VIIA | Type I | Microtubules, actin filaments | Microtubules, actin, vezatin, Shroom2, Keap1, MAP2B, harmonin, whirlin, pcdh15, sans, usherin, Vlgr1 | [4] |

| OPA1 | OPA1, Dynamin-like 120 kDa protein mitochondrial | Dual | Mitochondrial intermembrane space (inner membrane), lipid droplets | Perilipin, CGI-58 | [5,116] |

| CMYA5 | Myospryn | Type II | Costameres, lysosomes, intercalated disks | Dysbindin, calpain3, PP2B, desmin | [4] |

| EZR | Ezrin villin-2 cytovillin AKAP78 |

Dual | Cell-cell junction, filipodia, microvilli, other plasma membrane protrusions | Microtubules, actin, EBP50, DCC, Dbl, several membrane proteins, moesin | [4,5,70,117] |

| NF2 | Merlin neurofibromin-2 |

Type I | Plasma membrane, nucleus, actin, microtubules, cell-cell junctions | Lats1/2, EBP50, DCAF1, Dbl, actin, several membrane proteins, moesin | [4,117] |

| MSN | Moesin | Type II | Filopodia, cell-cell junctions, microvilli, other plasma membrane protrusions | Microtubules, actin, crumbs, EBP50, Dbl, DCC, several membrane proteins, merlin, ezrin | [117] |

| WASF | WAVE1, Scar | Type II | Actin cytoskeleton, dendritic spines | Abi, actin, Arp2/3, HSPC300, Sra-1/CYFIP1 | [5] |

| RAB32 | Rab32 | Type II | Mitochondria, melanosomes, lysosomes | mTor, LRRK2, SNX6, Varp | [118] |

| PIK3CG | p110γ PI3K-gamma |

Type II | Plasma membrane | PDE3B, Gβγ, Ras, Rab8a | [119] |

| NBEA | Neurobeachin | Type II | Golgi apparatus, trans Golgi network, synapses, nucleus | SAP102, Notch1 | [5] |

| CHD8 | Chd8 | Type II | Nuclear, perinuclear | Ash2l, Wdr5 | [120] |

| GSKIP | GSKIP | Type II | Cytosol | GSK3β, likely Tau | [121] |

| SYNM | Synemin | Type II | Costameres, intercalated disks, sarcolemma, focal adhesions | PP2A, other intermediate filament proteins | [4] |

| CBFA2T3 | MTG16 ETO2 |

Type II | Nucleus | IRF2BP2, HDAC1/2/3/6/8, SMRT, NCoR, ZNF651/2, HEB, TCF7L2/4 | [122] |

| RUNX1T1 | MTG8 CBFA2T1 ETO |

Type II | Nucleus, possibly centrosome and Golgi apparatus | LTβR, TCF7L2/4, PLZF, Sin3A, MTG16, BCL6, HDAC1/2/3 | [122] |

| ARFGEF2 | BIG2 | Dual | Trans Golgi network, endosomes | Exo70, GABA(A)Rβ, Filamin A, ARF4/5, Myosin IIa, PDE3A, FKBP13, PP1γ, TNFR1, β-catenin | [4,123] |

| CRYBG3 | vlAKAP | Type II | Binding motifs for β/γ crystalline, ricin B | [45] | |

| RSPH3 | RSP3 RSPH3 AKAP97 |

Type II | Radial spokes | Erk1/2 | [4] |

| AKAP85 | Golgi apparatus | Not cloned | [4] | ||

| rg (Drosophila melanogaster) | DAKAP550 neurobeachin |

Type II | Plasma membrane, cytoplasm | [4] | |

| Akap200 (D. melanogaster) | DAKAP200 | Type II | Plasma membrane | CaM, actin, PKC | [4] |

| aka-1 (Caenorhabditis elegans) | AKAPce | Type I | Binding domains for FYVE and TGF-βR | [4] |

A Contemporary Perspective on PKA Signaling

Covalent attachment of phosphate to proteins is an essential and ubiquitous mode of post-translational modification [6–8]. Protein phosphorylation events are highly regulated through the activity, substrate selectivity, and localization of over 540 protein kinases [9]. Moreover, the opposing actions of kinases and phosphatases ensure that protein phosphorylation is reversible and transient. While some kinases have exclusive roles such as pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, with only one known protein substrate [10], others such as CK1, CK2, and calmodulin-dependent kinases have many substrates and participate in numerous signaling pathways [11,12]. PKA falls into the latter category. This cAMP-activated serine/threonine kinase has hundreds of substrates, and regulates myriad cellular processes ranging from transcriptional regulation and energy metabolism to cytoskeletal rearrangements and ion channel gating [13,14]. Furthermore, many PKA-responsive processes run concurrently within the molecular congestion of the cell. Thus, avoiding crosstalk among these pathways is a remarkable and highly evolved phenomenon that requires exquisite spatial and temporal coordination. Perhaps not surprisingly, several modes of regulation ensure that spatiotemporal organization is operational. These include differential cAMP association/dissociation kinetics that influence the activation state of the enzyme; molecular flexibility that provides a range of action for the kinase; and subcellular localization that dictates which substrates become phosphorylated by individual pools of PKA. All of these features are built into PKA’s modular holoenzyme configuration and its interaction with AKAPs [13,15].

PKA holoenzymes contain two catalytic (PKAc) subunits attached to an R subunit dimer [13]. There are three versions of PKAc: α, β, and γ (genes PRKACA, PRKACB, or PRKACC); and four versions of R: RIα, RIβ, RIIα, and RIIβ (genes PRKAR1A, PRKAR1B, PRKAR2A, and PRKAR2B). In adults, PKAc α and β are expressed in most tissues, with PKAc γ expressed primarily in male reproductive tissues (Human Protein Atlas). R subunit expression is more variable as RI and RII isoforms exhibit overlapping distributions in most tissues (Human Protein Atlas). While PKA holoenzymes are compartmentalized with many substrates throughout the cytosol via AKAPs, this kinase is also known to act inside organelles such as mitochondria, the Golgi apparatus, and secretory vesicles [13,15,16]. Any free catalytic subunit can migrate to the nucleus where it regulates gene expression; however, biochemical data suggesting that R subunits are expressed in considerable excess of C in most cells cast some doubt on the potential for nuclear PKA [17].

The mechanism of holoenzyme activation has served as a standard example of second messenger signaling for five decades [18]. Even so, deeper insights continue to accumulate due to unrelenting interest in PKA. In the holoenzyme, regulatory subunits autoinhibit the catalytic subunit via a sequence of amino acids that occupy the substrate-binding interface of the kinase [13]. In RII subunits, this is a true RRXS substrate that can be phosphorylated, while RI subunits contain a pseudosubstrate at this site. cAMP binding to R acts as an allosteric switch that permits the C subunit to catalyze transfer of phosphate from ATP to a serine or threonine. This activation sequence occurs rapidly and transiently within individual nanodomains of elevated cAMP [19–21] (Figure 1). This fundamental tenet of compartmentalized signaling argues that catalysis must occur proximal to the site of enzyme activation. In the case of PKA activity, the ebb and flow of cAMP availability is controlled by the opposing actions of adenylyl cyclases, which generate second messenger, and phosphodiesterases (PDE), which terminate this signal [19,21] (see Box 1 for details of localized PKA activation).

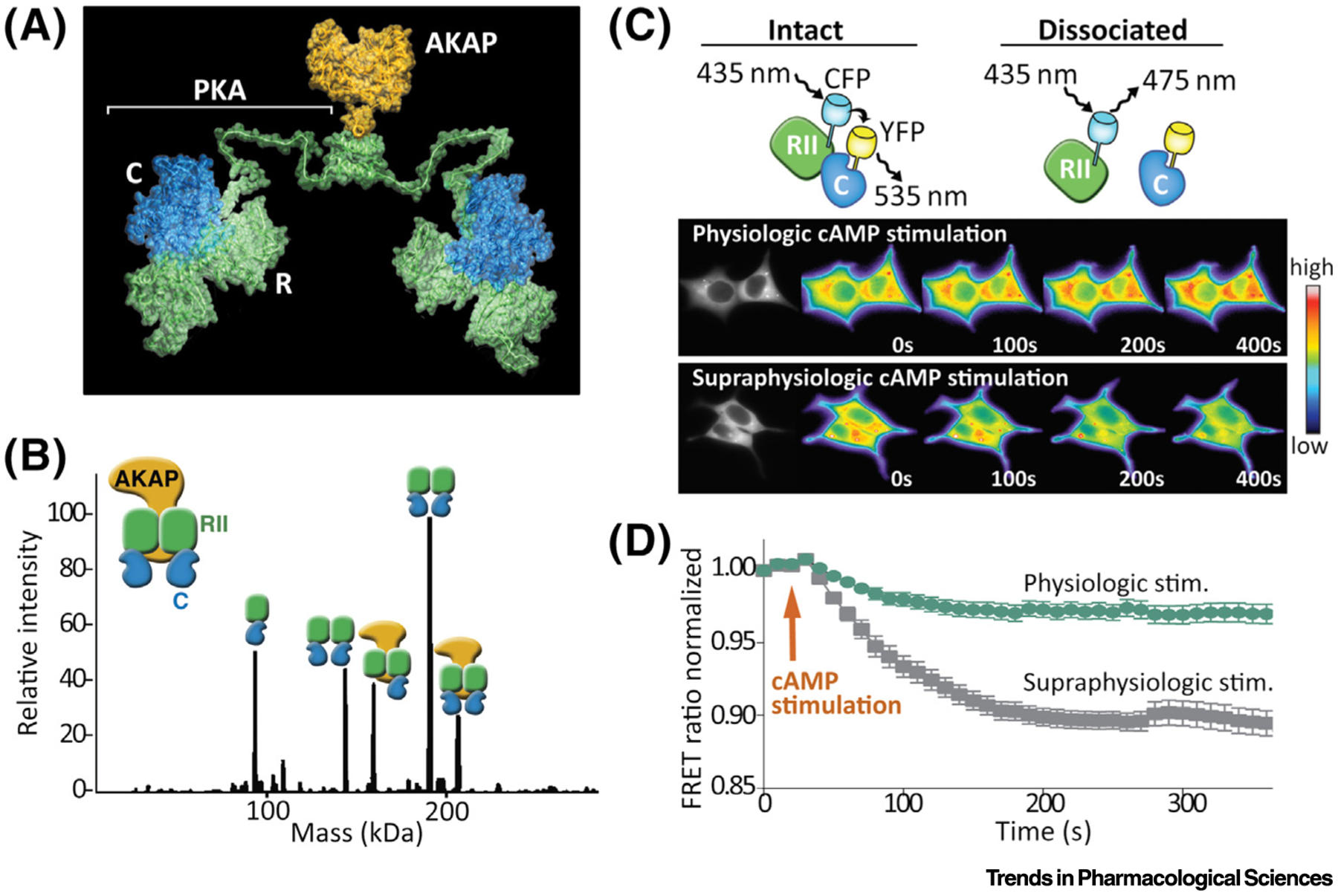

Figure 1. Active PKA Is Spatially Constrained.

(A) Structural model of an AKAP18-bound type II PKA holoenzyme. An RIIα (green) dimer is bound to two catalytic subunits (blue) and anchored to AKAP18 (gold) (adapted, with permission, from [19]). (B) Native mass spectrometry of RII+C+AKAP79 (297–427) complexes. In the presence of excess cAMP, the predominant species identified all involve PKAc still bound to R subunits. (C) Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements from cells expressing RII–CFP and PKAc–YFP. The β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol was administered to all conditions. Supraphysiological accumulation of cAMP is induced by treatment with the PDE3 inhibitor rolipram. (D) Upon delivery of the agonist (cAMP stimulation) under physiological conditions (green), a minimal loss of FRET indicates that the PKA holoenzyme remains largely intact. By contrast, upon supraphysiologic accumulation of cAMP (grey) loss of FRET signal indicates pronounced dissociation of the R:C interface. (B–D adapted , with permission, from [20]). Abbreviations: AKAP, A-kinase anchoring protein; C, catalytic subunit; PKA, protein kinase A; PKAc, PKA catalytic subunit; R, receptor; stim, stimulation.

Box 1. Localized Catalytic Activity of PKA.

The spatiotemporal action of PKA requires that this kinase remains close to its site of activation. Evidence for this concept has accumulated over the years, but prevailing dogma has limited its assimilation [19,92,93]. A classic view of PKA activation considers that the catalytic subunits are released from the PKA holoenzyme in the presence of cAMP [18]. Many of these mechanistic conclusions are predicated on the experimental use of the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin in conjunction with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX. These drugs saturate the cell with supraphysiological levels of cAMP. By contrast, when hormonal stimuli are used without manipulation of phosphodiesterase activity, the majority of PKAc is not released from the R subunit dimer [20] (see Figure 1A in main text). Several lines of evidence support this conclusion. Native mass spectrometry studies in the presence of cAMP show most PKAc in complex with R and AKAPs (see Figure 1B in main text). Live-cell imaging with Förster resonance energy transfer- (FRET) based biosensors that detect PKA holoenzyme formation (see Figure 1C in main text) reveals that hormonal stimulation or treatment with physiological agonists has no effect on the composition of anchored PKA holoenzymes (see Figure 1D in main text). Another contributing factor may be how tightly PKAc binds R subunits when cAMP is not available. This revised model of PKA activation indicates that recruitment by AKAPs into signaling islands determines which PKA substrates are phosphorylated [20,91]. Hence, PKA anchoring is the principle determinant in specifying the action of this key regulatory enzyme.

While the PKA catalytic subunits are considered redundant, the four regulatory subunits appear to be structurally and functionally distinct. These R subunit variants act as interchangeable components that diversify PKA function [22]. Type II holoenzymes were first recognized to anchor to AKAPs. This occurs via the amino-terminal docking and dimerization domains of RII that bind with high affinity to an amphipathic helix on the surface of AKAPs [23–26]. RI can similarly be associated with AKAPs such as sphingosine kinase interacting protein (SKIP) and small membrane AKAP (smAKAP), however holoenzymes containing RI subunits are also thought to exist in in the cytosol free [27–29]. Biochemical studies have further demonstrated differences in PKA activity due to cAMP affinity differences among the R subunits [30,31]. R subunits also exhibit different extents of molecular flexibility, with RIIβ maintaining a more rigid holoenzyme conformation as compared to RIIα [32]. This latter property impacts function. We have demonstrated that the rigidity of an R subunit dictates both the range of action for the catalytic subunit and the level of PKA phosphorylation of proximal substrates [19]. Another distinction among R subunits is how they accommodate catalytic subunit myristoylation. Incorporation of myristoylated PKAc contributes to the rigidity of type I PKA holoenzymes. By contrast, the same lipid modification is thought to enhance flexibility within the type II PKA holoenzyme, making it more amenable to association with membranes [33,34]. Taken together, such differences in the physiochemical profile of R subunit dimers expand the versatility and utility of PKA holoenzymes (see Box 2 for a discussion of R subunits in disease). However, spatiotemporal segregation that arises from association with AKAPs is likely to have a greater influence on PKA holoenzyme functions.

Box 2. R Subunit Expression in Disease.

Tissue-specific patterns of R subunit expression result in different ratios of type I and type II holoenzymes. In addition, changes in R subunit expression levels may alter kinase function and have been linked to disease [13,17,22,94]. Reduced levels or function of RIα causes Carney complex, an autosomal dominant disease accompanied by a variety of tumors [95]. Decreases in RIIβ are found in cortisol-producing adenomas of patients with ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome. Cushing’s syndrome adenomas are also caused by mutations in PKAc that render the kinase incapable of binding to R subunits [95,96]. In the liver cancer fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FLC), where one copy of PKAcα is fused with Hsp40, tumor levels of the RIα subunit are elevated while RIIβ levels are reduced [79,97]. Interestingly, in one case of FLC that lacks the hallmark fusion enzyme, tumors carry inactivating mutations in RIα [98]. Thus, changes in regulatory subunit expression and the ratio of type I to type II PKA holoenzymes are emblematic of tumorigenesis, and an area of active investigation.

Diversifying PKA Signaling through AKAPs

The notion that structural proteins tether PKA to distinct subcellular locations was introduced in the early 1980s when the microtubule-associated protein MAP2 was discovered as a kinase-anchoring protein [35]. Subsequent development of a solid-phase RII binding assay aided in the discovery of additional AKAPs (then called RII binding proteins) [36]. These early developments set the stage for work that defined the molecular basis of PKA anchoring [23,24,37,38]. AKAPs interact with R subunits through a 14–18-residue amphipathic helix that is evolutionarily conserved from nematodes to humans [23,39] (Table 1). Although a sequence motif is not evident, this helix is formed from alternating pairs of polar and hydrophobic residues, with certain hydrophilic anchors vital for strong binding [25,26,40,41]. Disruption of this pattern is deleterious as polymorphisms in the helix alter PKA binding and cause functional deficits [42]. AKAP helices vary in their preference for type I or type II PKA holoenzymes [4,43]. Type-I-selective helices are longer and have a larger region of interaction with the R subunit, perhaps necessitated by the less flexible binding interface on RI versus RII [44]. More recently, Heck and Scholten used known AKAP helix sequences to develop software that analyzes protein sequences and identifies PKA-binding domains [45]. It is possible that all of PKA is anchored within the cell. Since most cells express 10–15 different AKAPs, it is becoming clear that there are excess intracellular PKA-anchoring sites compared to the levels of kinase (Figure 2A).

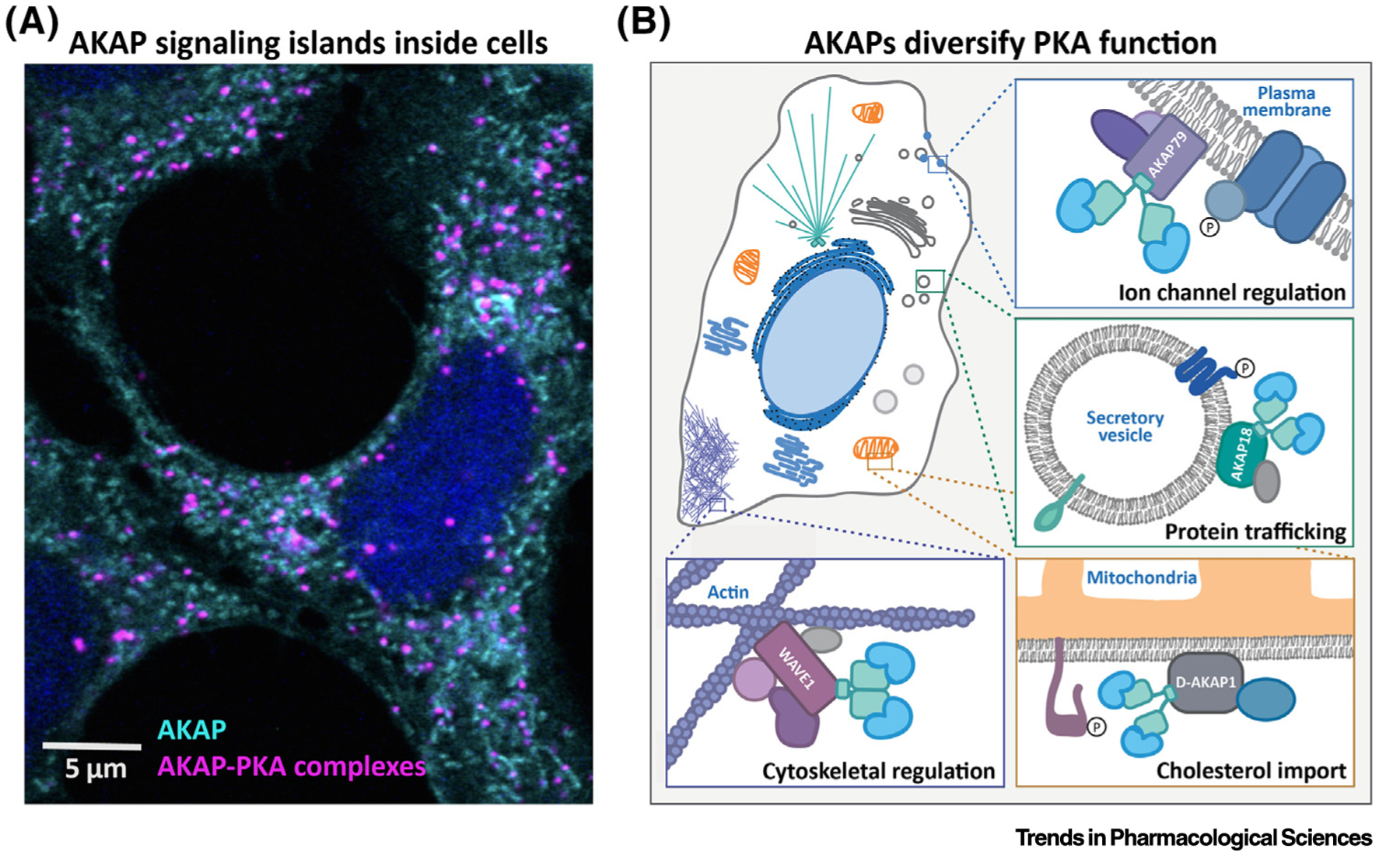

Figure 2. AKAPs Recruit PKA to Distinct Subcellular Locations to Expand Enzyme Versatility.

(A) immunofluorescent labeling of mitochondrial D-AKAP1 (cyan) and proximity ligation detection of D-AKAP1–PKA signaling islands (magenta). (B) AKAP signaling islands are found in distinct signaling compartments throughout the cell. Each AKAP localizes to a specific subcellular domain and associates with unique groupings of signaling molecules. Abbreviations: AKAP, A-kinase anchoring protein; PKA, protein kinase A.

Targeting motifs encoded within AKAPs tether their enzyme binding partners to organelles and other subcellular structures [46]. AKAP targeting concentrates PKA at distinct subcellular locations near sources of cAMP, including the plasma membrane at ion channels and receptors, the Golgi apparatus, the mitochondria (outer membrane and intermembrane space), the centrosome, specific regions within active cytoskeletal machinery, vesicles, and others (Figure 2A,B and Table 1). Subcellular targeting by AKAPs restricts signaling to the intended targets, allowing cells to avoid crosstalk among PKA pathways [46]. Another key aspect of AKAP signaling is that each anchoring protein organizes combinatorial assemblies of distinct signaling proteins via recruitment. These include ion channels, additional kinases, phosphatases, phosphodiesterases, adenylyl cyclases, GTPases, and components of the cytoskeleton (Table 1).

Targeting and recruitment is how AKAPs establish unique signaling islands. For example, AKAP79 (AKAP150; gene AKAP5), localizes to the plasma membrane via a phospholipid-associating polybasic motif at the amino terminus [47,48]. At the membrane, AKAP79 is further enriched at certain locations via binding motifs for membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) scaffold proteins and L-type calcium channels [49,50]. Additional to type II PKA, it can recruit protein kinase C, adenylyl cyclase 5/6, calmodulin, and protein phosphatase 2B (PP2B, calcineurin) [51–53]. These AKAP79-bound factors comprise a specialized network of enzymes and substrates that respond to the chemical signals in their immediate environment, such as calcium. Meanwhile, in the same cell another scaffolding protein, AKAP220 (gene AKAP11), brings PKA to vesicles along with protein phosphatase 1, glycogen synthase 3, and the GTPase-activating protein IQGAP1 [54–56]. These constituents form a completely different signaling island wherein PKA performs a distinct role in the control of vesicle trafficking or modulation of aquaporin 2 water pores in the kidney [57]. Likewise, Gravin /AKAP250 (gene AKAP12) anchors the mitotic kinases Aurora A and Plk1 at spindle poles during metaphase [58]. Loss of Gravin or specific disruption of its interaction with either Aurora A or Plk1 results in mitotic delay [59]. This role for Aurora A is distinct from its roles at other subcellular locations, such as phosphorylation of Hec1 at the kinetochore [60]. Thus, assembly of different AKAP complexes ensures that common signaling elements can be organized to simultaneously accomplish multiple tasks in the same cell (Figure 2B).

Exploiting AKAPs for Drug Delivery

Coupling AKAP signaling complexes with subcellular tasks presents an opportunity for more precise manipulation in the treatment of disease. Drug therapies that counteract pathological signaling events are often complicated by off-target effects. The standard definition of this common phenomenon is when a drug acts on molecules other than its intended target with deleterious consequences. More recently, another off-target effect, which we term indiscriminate drug delivery, has gained attention. This form of toxicity can arise for two reasons. First, most drugs are unable to differentiate among intracellular subpopulations of their target, and thereby affect all signaling pathways involving the target protein. Additionally, the drug target may perform cell type-specific functions [61]. For example, PP2B/calcineurin inhibitors are used to suppress the immune system in organ transplant patients. While this decreases the risk of host rejection, patients can experience several adverse effects including neurological defects and pancreatic β-cell death, leading to diabetes mellitus [62]. In this way, a well-tolerated drug such as cyclosporine or FK506/tacrolimus that exhibits high fidelity for its protein target in immune cells can have significant off-target effects in other cell types. Such target complications restrict patient lifestyle and compromise treatment options.

Spatial targeting of drugs within cells may ameliorate the off-target affects associated with indiscriminate drug delivery [61]. This is the central doctrine of precision pharmacology, which exploits the spatiotemporal profile of a drug target to more accurately deliver therapeutic agents. The ability of AKAPs to scaffold multiple kinases and phosphatases naturally creates a cellular locus for the concerted action of drugs. This has driven the development of reagents that target AKAP signaling islands to perturb interactions with PKA, protein phosphatases, or certain phosphodiesterases [5,63]. A limitation of peptide disruptors is that they block AKAP–enzyme interfaces indiscriminately. For example, VIVIT or PXIXIT peptides derived from PP2B-binding proteins like AKAP79 displace the phosphatase from all binding partners [64–66]. Likewise, PKA anchoring disruptors cannot be used to discriminate which anchoring protein is responsible for a given cellular event [40,44,67].

However, there are isolated examples of preferential disruption of PKA from specific AKAPs [68–70]. In the nervous system, AKAP79 binds to adenylyl cyclase 5/6 (AC5/6), thereby bringing PKA to the site of cAMP production [52]. Disrupting the AKAP79–AC5/6 interaction with a peptide uncouples prostaglandin responsive activation of TRPV1 channels [71]. Interestingly, uncoupling the AKAP79–AC5 interaction decreases pain-associated spontaneous activity in dorsal root ganglion neurons after spinal cord injury [72]. These investigators are currently targeting this protein–protein interaction as a strategy to control chronic pain. This highlights the utility of peptides and peptidomimetics that disrupt protein–protein interactions as an emerging therapeutic strategy [73]. Nonetheless, small molecules still dominate drug development due to their superior bioavailability, cell permeability, and stability.

Undoubtedly the greatest therapeutic benefit will come from targeting individual AKAP signaling islands. In the laboratory, this is often achieved by genetic manipulation [74–77]. More recently, gene-editing techniques have been used [57,78]. However, this strategy awaits widespread translation into the clinic. Another therapeutic approach is directing drug combinations to an AKAP signaling island. In the liver cancer fibrolamellar carcinoma, a genomic deletion fuses PKAc with part of the chaperone heat shock protein 40 kDa (Hsp40), which recruits heat shock protein 70 kDa (Hsp70). Using a cell culture model of this disease, a recent drug screen found that combinations targeting Hsp70 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) had a synergistic effect on cell proliferation specifically in cells expressing the fusion protein [79]. A related strategy is the development of multitargeted therapeutics, including bispecific small molecules and proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) [80]. In an ideal application, a small molecule that binds to the AKAP of interest would be conjugated to an inhibitor for an AKAP-bound enzyme, such as analogs of the PKA inhibitor H89. Proof of principle for this strategy has been demonstrated in cells and zebrafish using mitosis as a model [60]. This study used chemical biology methods to direct SNAP-tag ligand chloropyrimidine (CLP)-modified inhibitors to a SNAP-tagged targeting domain from either AKAP450, which targets centrosomes, or Mis12, a component of the chromosome-associated kinetochore. Targeted inhibition of pololike kinase 1 (PLK1) at centrosomes disrupted mitosis significantly more than indiscriminate inhibition. Furthermore, use of CLP-labeled Aurora A inhibitors at the kinetochore decreased phosphorylation of S69 on the Aurora A substrate Hec1 at that location while leaving phosphorylation of Hec1 S69 at centrosomes unchanged [60]. A similar approach used molecular tethers on the extracellular surface of neurons to enrich drugs near their targets on specific cell types [81]. While the benefit of drugs that act as coincidence detectors is clear, translating this approach into the clinic will require adaptation of the targeting mechanism as well as structural optimization of compounds.

One example of potential AKAP drug targeting involves delivering calcineurin inhibitors to AKAP79/150 signaling islands. Potential human disease applications for this system include diabetes and dementia. In a mouse model that lacks the AKAP150 calcineurin-binding motif, loss of calcineurin at this signaling island results in enhanced glucose tolerance, concurrent with more economical insulin release [76]. Additionally, neurons in these mice demonstrate disrupted long-term depression (synaptic weakening) [82]. In a clinical study of dementia patients, those receiving calcineurin inhibitors were found to be less than one tenth as likely to develop dementia versus the general population [83]. One strategy to accomplish this local inhibition involves conjugating calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine or tacrolimus to a molecule that specifically targets AKAP79/150. Importantly, the targeting moiety should not mimic or target the calcineurin binding motif or any region of AKAP79/150 that is shared with other calcineurin-associated molecules, as this would disrupt additional signaling pathways of the phosphatase. Current strategies being investigated to achieve subcellular or tissue-specific targeting include nanobodies, peptides, and peptidomimetics. If the drug involves bulky targeting domains, one must also overcome barriers such as the extracellular matrix, the blood–brain barrier, and the plasma membrane, while also ensuring that the compound remains soluble and active [61,84]. Alternatively, membrane-associating modifications could also enrich drugs where AKAP79/150 localizes, thereby improving specificity. Dozens of AKAPs, each with multiple complex components, offer abundant opportunities for targeted drug design. Nonetheless, compound development depends upon basic knowledge of AKAP roles and their constituent molecules.

Methodological Developments That Impact AKAP Research

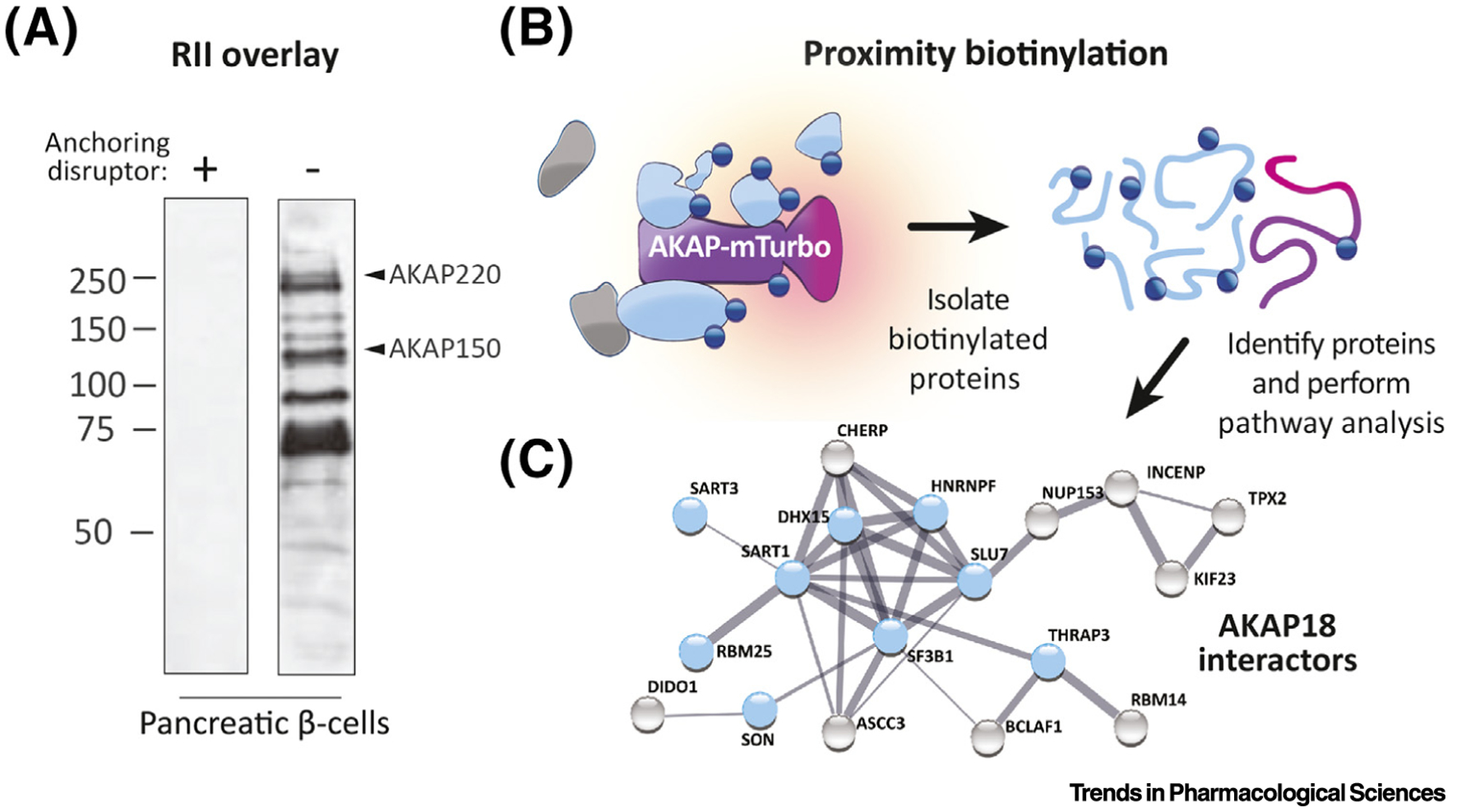

Empirically assigning AKAP signaling islands to the coordination of specific physiologic processes is a necessary prelude to therapeutic intervention. Traditionally, the RII overlay far-western blot approach has been used to catalog the tissue-specific expression of AKAPs. For example, insulin-secreting pancreatic β-islet cells express a range of AKAPs, including AKAP79/150, a multivalent anchoring protein that coordinates aspects of insulin secretion [76,85] (Figure 3A, right lane). A standard control for these studies is to block the PKA–AKAP interaction upon preincubation with anchoring disruptor peptides HT-31 or AKAPis [40] (Figure 3A, left lane). Affinity purification of AKAPs through the capture of R subunits on cAMP–agarose is often considered a more sensitive means to detect AKAPs in a given tissue [86]. One advantage of this latter approach is that mass spectrometry identification can be used to survey the entire AKAP landscape in different tissues.

Figure 3. Identifying AKAPs in Cells and Tissues.

(A) RII overlay shows binding of RII probe to AKAP helices after SDS-PAGE and immobilization on a membrane. The left lane was preincubated with the AKAP disruptor peptide Ht31 prior to RII incubation. Arrows indicate subsequently identified AKAPs in the right lane. (Images adapted from [76]). (B) Diagram depicting a proximity biotinylation experiment using an AKAP as the bait molecule fused to the promiscuous biotin ligase miniTurbo. Once labeled, the proteins are isolated and subjected to denaturing wash conditions. (C) Mass spectrometry identification and pathway analysis can yield protein interaction networks and candidate cell processes. Network depicted represents proteins that associate significantly more with a nuclear AKAP18 isoform versus a cytosolic isoform. Blue nodes indicate proteins involved in RNA splicing (Figure adapted from [42]). Abbreviations: AKAP, A-kinase anchoring protein; PKA, protein kinase A; R, receptor.

Recent methodological developments have enabled more nuanced approaches to identifying AKAPs. In situ proximity labeling allows for proteomic interrogation of a molecule’s immediate environment in living cells (~10 nm diameter) [42,87,88] (Figure 3B). This technique uses a biotin ligase (BirA or miniTurbo) or peroxidase (APEX) tag to efficiently label proximal proteins with biotin, thereby allowing streptavidin affinity purification and subsequent identification by mass spectrometry. Clear advantages of applying proximity proteomics to AKAP biology include the ability to attach the biotin ligase to different components of the AKAP signaling island. For example, fusion of miniTurbo to RI facilitates identification of type-I-selective AKAPs. Conversely, fusion of the same moiety to RII reveals RII-selective AKAPs. Perhaps more interestingly, fusion of miniTurbo to the catalytic subunit not only illuminates the entire spectrum of AKAPs that engage PKA holo-enzymes, but can also detect changes in these complexes upon hormonal stimulation. For instance, PKA may be more associated with mitochondrial AKAPs in cortisol-secreting adrenal cells that have been exposed to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) [89].

Once an AKAP of interest is identified, it can then be fused to biotin ligase for proximity labeling of the molecular complex (Figure 3B). Subsequent pathway analysis provides quantitative biochemical and bioinformatic clues regarding the composition and biological role of compartment-specific AKAP complexes. This approach has recently been used to construct and compare interactomes for different versions of AKAP18 [42] (Figure 3C). Future applications of this technique will probe changes in AKAP signaling island architecture upon deletion or gene silencing of individual components of the cAMP signaling cascade. Finally, the ability to label proteins within live animals and tissues makes proximity biotinylation a preferred approach in terms of physiological relevance [90]. These advances in technology will undoubtedly lead to the discovery of new anchoring proteins and further define the AKAP signaling environment at a system-wide level.

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

PKA holoenzymes are no longer considered to be freely diffusing kinases. This is because most if not all of this key regulatory enzyme class is associated with AKAPs (Figure 2A). Moreover, recent structural and cell biological approaches have revealed that upon physiological stimulation, PKA activity remains tightly restricted to its site of activation [20,91] (Figure 1). PKA’s modular structure combined with its regions of intrinsic disorder create a flexible and dynamic enzyme complex that has a range of action on the order of 200–400 Å. These parameters define the scope of anchored PKA signaling. However, association with individual AKAPs provides the cellular context in which the substrate selectivity of PKA is conferred (Figure 2B). Thus, the specificity imparted by AKAPs for PKA and other enzymes presents an opportunity to therapeutically target discrete cellular processes.

Several studies have set precedence for exploiting AKAP signaling islands as venues for precision pharmacology. If drugs are to be efficiently targeted to AKAPs, future efforts will need to focus on peptidomimetics, small molecules, or nanobodies that bind to specific anchoring proteins [61]. Similarly, effective use of combinatorial drug regimens will require further knowledge of AKAP signaling complex composition (see Outstanding Questions). Continuing to advance these efforts with the combination of recent biochemical approaches and classical cell and molecular biology techniques will provide new frontiers in drug delivery and treatment of disease.

Outstanding Questions.

Do the actions of individual hormones, neurotransmitters, or prostaglandins proceed through distinct AKAP signaling islands?

What genetic lesions in AKAPs are linked to neurological and cardiovascular diseases and cancers?

How do pathological changes in R subunit expression and altered ratios of type I to type II PKA holoenzymes underlie certain endocrine disorders, adenomas, and carcinomas?

How do disease-causing PKAc variants perturb downstream signaling when incorporated into AKAP signaling islands?

What is the molecular basis of AKAP targeting to the full range of intracellular organelles?

Can we develop small molecules, peptidomimetics, or nanobodies directed toward AKAP signaling islands for use as precision therapeutics?

Highlights.

Protein kinase A (PKA) is a versatile and spatially restricted cell signaling enzyme.

A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) define which substrates have access to PKA.

Local signaling islands shape the cellular role of PKA and other AKAP-associated enzymes.

Recent in situ pharmacological strategies suggest that AKAPs can be used as platforms for drug targeting.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank F. Donelson Smith for assistance and discussions regarding the manuscript. M.H.O. and J.D.S. are supported by the National Institutes of Health grants F32DK121415 (M.H.O.), DK119186 (J.D.S.), and DK119192 (J.D.S.) and a research grant from the Fibrolamellar Foundation (J.D.S.).

References

- 1.Scott JD and Pawson T (2009) Cell signaling in space and time: where proteins come together and when they’re apart. Science 326, 1220–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeynaems S et al. (2018) Protein phase separation: a new phase in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 28, 420–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langeberg LK and Scott JD (2015) Signalling scaffolds and local organization of cellular behaviour. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 16, 232–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pidoux G and Tasken K (2010) Specificity and spatial dynamics of protein kinase A signaling organized by Akinase-anchoring proteins. J. Mol. Endocrinol 44, 271–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deak VA and Klussmann E (2016) Pharmacological interference with protein-protein interactions of akinase anchoring proteins as a strategy for the treatment of disease. Curr. Drug Targets 17, 1147–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer EH (2013) Cellular regulation by protein phosphorylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 430, 865–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen P (2002) The origins of protein phosphorylation. Nat. Cell Biol 4, E127–E130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pawson T and Scott JD (2005) Protein phosphorylation in signaling – 50 years and counting. Trends Biochem. Sci 30, 286–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manning G et al. (2002) The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science 298, 1912–1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gudi R et al. (1995) Diversity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase gene family in humans. J. Biol. Chem 270, 28989–28994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knippschild U et al. (2005) The casein kinase 1 family: participation in multiple cellular processes in eukaryotes. Cell. Signal 17, 675–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun AP and Schulman H (1995) The multifunctional calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase: from form to function. Annu. Rev. Physiol 57, 417–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor SS et al. (2012) Assembly of allosteric macromolecular switches: lessons from PKA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 13, 646–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser ID and Scott JD (1999) Modulation of ion channels: a “current” view of AKAPs. Neuron 23, 423–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott JD et al. (2013) Creating order from chaos: cellular regulation by kinase anchoring. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 53, 187–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lefkimmiatis K and Zaccolo M (2014) cAMP signaling in subcellular compartments. Pharmacol. Ther 143, 295–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker-Gray R et al. (2017) Mechanisms for restraining cAMP-dependent protein kinase revealed by subunit quantitation and cross-linking approaches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 114, 10414–10419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krebs EG et al. (1985) The functions of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase In Mechanisms of Receptor Regulation (Crooke ST and Poste G, eds), pp. 324–367, Plenum [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith FD et al. (2013) Intrinsic disorder within an AKAP-protein kinase A complex guides local substrate phosphorylation. eLife 2, e01319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith FD et al. (2017) Local protein kinase A action proceeds through intact holoenzymes. Science 356, 1288–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musheshe N et al. (2018) cAMP: from long-range second messenger to nanodomain signalling. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 39, 209–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skalhegg BS and Tasken K (2000) Specificity in the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. Differential expression, regulation, and subcellular localization of subunits of PKA. Front. Biosci 5, D678–D693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carr DW et al. (1991) Interaction of the regulatory subunit (RII) of cAMP-dependent protein kinase with RII-anchoring proteins occurs through an amphipathic helix binding motif. J. Biol. Chem 266, 14188–14192 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott JD et al. (1990) Type II regulatory subunit dimerization determines the subcellular localization of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem 265, 21561–21566 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newlon MG et al. (1999) The molecular basis for protein kinase A anchoring revealed by solution NMR. Nat. Struct. Biol 6, 222–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gold MG et al. (2006) Molecular basis of AKAP specificity for PKA regulatory subunits. Mol. Cell 24, 383–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burgers PP et al. (2012) A small novel A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) that localizes specifically protein kinase A-regulatory subunit I (PKA-RI) to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem 287, 43789–43797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Means CK et al. (2011) An entirely specific type I A-kinase anchoring protein that can sequester two molecules of protein kinase A at mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108, E1227–E1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovanich D et al. (2010) Sphingosine kinase interacting protein is an A-kinase anchoring protein specific for type I cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chembiochem 11, 963–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ueland PM and Doskeland SO (1976) Adenosine 3’:5’-cyclic monophosphate-dependence of protein kinase isoenzymes from mouse liver. Biochem. J 157, 117–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dostmann WR and Taylor SS (1991) Identifying the molecular switches that determine whether (Rp)-cAMPS functions as an antagonist or an agonist in the activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase I. Biochemistry 30, 8710–8716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang P et al. (2012) Structure and allostery of the PKA RIIbeta tetrameric holoenzyme. Science 335, 712–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang P et al. (2015) An isoform-specific myristylation switch targets type II PKA holoenzymes to membranes. Structure 23, 1563–1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tillo SE et al. (2017) Liberated PKA catalytic subunits associate with the membrane via myristoylation to preferentially phosphorylate membrane substrates. Cell Rep. 19, 617–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theurkauf WE and Vallee RB (1982) Molecular characterization of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase bound to microtubule-associated protein 2. J. Biol. Chem 257, 3284–3290 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lohmann SM et al. (1984) High-affinity binding of the regulatory subunit (RII) of cAMP-dependent protein kinase to microtubule-associated and other cellular proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 81, 6723–6727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carr DW et al. (1992) Association of the type II cAMP-dependent protein kinase with a human thyroid RII-anchoring protein. Cloning and characterization of the RII-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem 267, 13376–13382 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carr DW et al. (1992) Localization of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase to the postsynaptic densities by A-kinase anchoring proteins: characterization of AKAP79. J. Biol. Chem 24, 16816–16823 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng M et al. (2015) Spatial organization in protein kinase A signaling emerged at the base of animal evolution. J. Proteome Res 14, 2976–2987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alto NM et al. (2003) Bioinformatic design of A-kinase anchoring protein-in silico: A potent and selective peptide antagonist of type II protein kinase A anchoring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 100, 4445–4450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gotz F et al. (2016) AKAP18:PKA-RIIalpha structure reveals crucial anchor points for recognition of regulatory subunits of PKA. Biochem. J 473, 1881–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith FD et al. (2018) Single nucleotide polymorphisms alter kinase anchoring and the subcellular targeting of A-kinase anchoring proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115, E11465–E11474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang LJ et al. (1997) Identification of a novel dual specificity protein kinase A anchoring protein, D-AKAP1. J. Biol. Chem 272, 8057–8064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carlson CR et al. (2006) Delineation of type I protein kinase A-selective signaling events using an RI anchoring disruptor. J. Biol. Chem 281, 21535–21545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burgers PP et al. (2015) A systematic evaluation of protein kinase A-A-kinase anchoring protein interaction motifs. Biochemistry 54, 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong W and Scott JD (2004) AKAP Signalling complexes: Focal points in space and time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 5, 959–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dell’Acqua ML et al. (1998) Membrane-targeting sequences on AKAP79 bind phosphatidylinositol-4, 5- bisphosphate. EMBO J. 17, 2246–2260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bal M et al. (2010) Ca2+/calmodulin disrupts AKAP79/150 interactions with KCNQ (M-Type) K+ channels. J. Neurosci 30, 2311–2323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colledge M et al. (2000) Targeting of PKA to glutamate receptors through a MAGUK-AKAP complex. Neuron 27, 107–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oliveria SF et al. (2007) AKAP79/150 anchoring of calcineurin controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and nuclear signaling. Neuron 55, 261–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klauck TM et al. (1996) Coordination of three signaling enzymes by AKAP79, a mammalian scaffold protein. Science 271, 1589–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bauman AL et al. (2006) Dynamic regulation of cAMP synthesis through anchored PKA-adenylyl cyclase V/VI complexes. Mol. Cell 23, 925–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coghlan VM et al. (1995) Association of protein kinase A and protein phosphatase 2B with a common anchoring protein. Science 267, 108–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whiting JL et al. (2015) Protein kinase A opposes the phosphorylation-dependent recruitment of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta to A-kinase anchoring protein 220. J. Biol. Chem 290, 19445–19457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Logue JS et al. (2011) AKAP220 protein organizes signaling elements that impact cell migration. J. Biol. Chem 286, 39269–39281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schillace RV and Scott JD (1999) Association of the type 1 protein phosphatase PP1 with the A-kinase anchoring protein AKAP220. Curr. Biol 9, 321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whiting JL et al. (2016) AKAP220 manages apical actin networks that coordinate aquaporin-2 location and renal water reabsorption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, E4328–E4337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canton DA et al. (2012) Gravin is a transitory effector of pololike kinase 1 during cell division. Mol. Cell 48, 547–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hehnly H et al. (2015) A mitotic kinase scaffold depleted in testicular seminomas impacts spindle orientation in germ line stem cells. eLife 4, e09384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bucko PJ et al. (2019) Subcellular drug targeting illuminates local kinase action. eLife 8, e52220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao Z et al. (2020) Targeting strategies for tissue-specific drug delivery. Cell 181, 151–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farouk SS and Rein JL (2020) The many faces of calcineurin inhibitor toxicity-what the FK? Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis 27, 56–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kennedy EJ and Scott JD (2015) Selective disruption of the AKAP signaling complexes. Methods Mol. Biol 1294, 137–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dell’Acqua ML et al. (2002) Mapping the protein phosphatase-2B anchoring site on AKAP79. Binding and inhibition of phosphatase activity are mediated by residues 315–360. J. Biol. Chem 277, 48796–48802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li H et al. (2012) Balanced interactions of calcineurin with AKAP79 regulate Ca(2+)-calcineurin-NFAT signaling. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 19, 337–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang L et al. (2020) A novel peptide exerts potent immunosuppression by blocking the two-site interaction of NFAT with calcineurin. J. Biol. Chem 295, 2760–2770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hoshi N et al. (2005) Distinct enzyme combinations in AKAP signalling complexes permit functional diversity. Nat. Cell Biol 7, 1066–1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lygren B et al. (2007) AKAP complex regulates Ca2+ re-uptake into heart sarcoplasmic reticulum. EMBO Rep. 8, 1061–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dodge-Kafka KL et al. (2005) The protein kinase A anchoring protein mAKAP coordinates two integrated cAMP effector pathways. Nature 437, 574–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dukic AR et al. (2017) A protein kinase A-ezrin complex regulates connexin 43 gap junction communication in liver epithelial cells. Cell. Signal 32, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Efendiev R et al. (2013) Scaffolding by A-kinase anchoring protein enhances functional coupling between adenylyl cyclase and TRPV1 channel. J. Biol. Chem 288, 3929–3937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bavencoffe A et al. (2016) Persistent electrical activity in primary nociceptors after spinal cord injury is maintained by scaffolded adenylyl cyclase and protein kinase A and is associated with altered adenylyl cyclase regulation. J. Neurosci 36, 1660–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.D’Annessa I et al. (2020) Bioinformatics and biosimulations as toolbox for peptides and peptidomimetics design: where are we? Front. Mol. Biosci 7, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Soderling SH et al. (2003) Loss of WAVE-1 causes sensori-motor retardation and reduced learning and memory in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 100, 1723–1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tunquist BJ et al. (2008) Loss of AKAP150 perturbs distinct neuronal processes in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 12557–12562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hinke SA et al. (2012) Anchored phosphatases modulate glucose homeostasis. EMBO J. 31, 3991–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Newhall KJ et al. (2006) Dynamic anchoring of PKA is essential during oocyte maturation. Curr. Biol 16, 321–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stover JD et al. (2017) CRISPR epigenome editing of AKAP150 in DRG neurons abolishes degenerative IVD-induced neuronal activation. Mol. Ther 25, 2014–2027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Turnham RE et al. (2019) An acquired scaffolding function of the DNAJ-PKAc fusion contributes to oncogenic signaling in fibrolamellar carcinoma. eLife 8, e44187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maniac C. and Ciull A. (2019) Bifunctional chemical probes inducing protein-protein interactions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 52, 145–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shields BC et al. (2017) Deconstructing behavioral neuro-pharmacology with cellular specificity. Science 356, eaaj2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sanderson JL et al. (2012) AKAP150-anchored calcineurin regulates synaptic plasticity by limiting synaptic incorporation of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors. J. Neurosci 32, 15036–15052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Taglialatela G et al. (2015) Reduced incidence of dementia in solid organ transplant patients treated with calcineurin inhibitors. J. Alzheimers Dis 47, 329–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lim SI (2020) Fine-tuning bispecific therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther 212, 107582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lester LB et al. (1997) Anchoring of protein kinase A facilitates hormone-mediated insulin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 94, 14942–14947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dodge KL et al. (2001) mAKAP assembles a protein kinase A/PDE4 phosphodiesterase cAMP signaling module. EMBO J. 20, 1921–1930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fernández-Suárez M et al. (2008) Protein-protein interaction detection in vitro and in cells by proximity biotinylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 130, 9251–9253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim DI et al. (2014) Probing nuclear pore complex architecture with proximity-dependent biotinylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, E2453–E2461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Midzak A and Papadopoulos V (2016) Adrenal mitochondria and steroidogenesis: from individual proteins to functional protein assemblies. Front Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 7, 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Spence EF et al. (2019) In vivo proximity proteomics of nascent synapses reveals a novel regulator of cytoskeleton-mediated synaptic maturation. Nat. Commun 10, 386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Isensee J et al. (2018) PKA-RII subunit phosphorylation precedes activation by cAMP and regulates activity termination. J. Cell Biol 217, 2167–2184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang S et al. (1995) Regulation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase: enzyme activation without dissociation. Biochemistry 34, 6267–6271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kopperud R et al. (2002) Formation of inactive cAMP-saturated holoenzyme of cAMP-dependent protein kinase under physiological conditions. J. Biol. Chem 277, 13443–13448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lacroix A et al. (2015) Cushing’s syndrome. Lancet 386, 913–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Espiard S and Bertherat J (2015) The genetics of adrenocortical tumors. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am 44, 311–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Calebiro D et al. (2014) PKA catalytic subunit mutations in adrenocortical Cushing’s adenoma impair association with the regulatory subunit. Nat. Commun 5, 5680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Riggle KM et al. (2016) Enhanced cAMP-stimulated protein kinase A activity in human fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Pediatr. Res 80, 110–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Graham RP et al. (2018) Fibrolamellar carcinoma in the Carney complex: PRKAR1A loss instead of the classic DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion. Hepatology 68, 1441–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu Y et al. (2020) A-kinase anchoring protein 1: emerging roles in regulating mitochondrial form and function in health and disease. Cells 9, 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rinaldi L et al. (2017) Mitochondrial AKAP1 supports mTOR pathway and tumor growth. Cell Death Dis. 8, e2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Murphy JG et al. (2019) AKAP79/150 recruits the transcription factor NFAT to regulate signaling to the nucleus by neuronal L-type Ca(2+) channels. Mol. Biol. Cell 30, 1743–1756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Keith DJ et al. (2012) Palmitoylation of A-kinase anchoring protein 79/150 regulates dendritic endosomal targeting and synaptic plasticity mechanisms. J. Neurosci 32, 7119–7136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sekiguchi F et al. (2013) AKAP-dependent sensitization of Ca(v) 3.2 channels via the EP(4) receptor/cAMP pathway mediates PGE(2) -induced mechanical hyperalgesia. Br. J. Pharmacol 168, 734–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hoshi N et al. (2003) AKAP150 signaling complex promotes suppression of the M-current by muscarinic agonists. Nat. Neurosci 6, 564–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sandoz G et al. (2006) AKAP150, a switch to convert mechano-, pH- and arachidonic acid-sensitive TREK K(+) channels into open leak channels. EMBO J. 25, 5864–5872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kapiloff MS et al. (2009) An adenylyl cyclase-mAKAPbeta signaling complex regulates cAMP levels in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem 284, 23540–23546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Clister T et al. (2019) AKAP95 organizes a nuclear microdo-main to control local cAMP for regulating nuclear PKA. Cell Chem. Biol 26, 885–891.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Melick CH et al. (2020) A-kinase anchoring protein 8L interacts with mTORC1 and promotes cell growth. J. Biol. Chem 295, 8096–8105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Verma NK et al. (2019) CG-NAP/kinase interactions fine-tune T cell functions. Front. Immunol 10, 2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li Y et al. (2019) Regulation of I(Ks) potassium current by isoproterenol in adult cardiomyocytes requires type 9 adenylyl cyclase. Cells 8, 981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bouguenina H et al. (2017) EB1-binding-myomegalin protein complex promotes centrosomal microtubules functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 114, E10687–e10696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dema A et al. (2020) Cyclin-dependent kinase 18 controls trafficking of aquaporin-2 and its abundance through ubiquitin ligase STUB1, which functions as an AKAP. Cells 9, 673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sumandea CA et al. (2011) Cardiac troponin T, a sarcomeric AKAP, tethers protein kinase A at the myofilaments. J. Biol. Chem 286, 530–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lin C et al. (2013) Cypher/ZASP is a novel A-kinase anchoring protein. J. Biol. Chem 288, 29403–29413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Goehring AS et al. (2007) MyRIP anchors protein kinase A to the exocyst complex. J. Biol. Chem 282, 33155–33167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rogne M et al. (2018) OPA1-anchored PKA phosphorylates perilipin 1 on S522 and S497 in adipocytes differentiated from human adipose stem cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 29, 1487–1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Michie KA et al. (2019) Two sides of the coin: ezrin/radixin/moesin and merlin control membrane structure and contact inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci 20, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Drizyte-Miller K et al. (2020) The small GTPase Rab32 resides on lysosomes to regulate mTORC1 signaling. J. Cell Sci 133, jcs236661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Perino A et al. (2011) Integrating cardiac PIP3 and cAMP signaling through a PKA anchoring function of p110gamma. Mol. Cell 42, 84–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Goodman JV and Bonni A (2019) Regulation of neuronal connectivity in the mammalian brain by chromatin remodeling. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 59, 59–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Dema A et al. (2016) The A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) glycogen synthase kinase 3beta interaction protein (GSKIP) regulates beta-catenin through its interactions with both protein kinase a (PKA) and GSK3beta. J. Biol. Chem 291, 19618–19630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Steinauer N et al. (2017) Emerging roles of MTG16 in cell-fate control of hematopoietic stem cells and cancer. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 6301385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Li CC et al. (2016) Enhancement of β-catenin activity by BIG1 plus BIG2 via Arf activation and cAMP signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, 5946–5951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]