Abstract

The functional properties of cuprates are strongly determined by the doping state and carrier density. We present an oxygen doping study of YBa2Cu3O7-δ (YBCO) thin films from underdoped to overdoped state, correlating the measured charge carrier density, , the hole doping, p, and the critical current density, . Our results show experimental demonstration of strong increase of with , up to Quantum Critical Point (QCP), due to an increase of the superconducting condensation energy. The ultra-high achieved, 90 MA cm−2 at 5 K corresponds to about a fifth of the depairing current, i.e. a value among the highest ever reported in YBCO films. The overdoped regime is confirmed by a sudden increase of , associated to the reconstruction of the Fermi-surface at the QCP. Overdoping YBCO opens a promising route to extend the current carrying capabilities of rare-earth barium copper oxide (REBCO) coated conductors for applications.

Subject terms: Materials science, Condensed-matter physics, Superconducting properties and materials

Introduction

High temperature superconductors (HTS) are key materials for many applications, with special interest in those related to the energy sector1,2. However, to reach these opportunities, outstanding research had to be made within the last 30 years from the discovery of high temperature superconductivity, to overcome the most critical materials issues3,4. The successful development of superconducting Coated Conductors (CC) is based on the uniform textured deposition of thick, homogeneous nanoengineered structures in kilometres length (a desired correlation over twelve orders of magnitude!). Cuprate materials in the form of CCs have opened up new opportunities in the field of superconducting applications5 and nowadays offer the performance to boost technological innovations such as dissipation-free energy transmission in superconducting grids, highly efficient engines for electrical aviation or compact fusion reactors beyond ITER. However, current carrying capacities are still far from theoretical limits6,7.

While on one hand dissipation free current transport is intrinsically limited by the depairing current density, , beyond which Cooper pair condensation is energetically not favourable, in real systems the dissipation free, critical current density, is smaller due to the motion of magnetic vortices. One major goal in the development of superconducting tapes is to merge with the theoretical limit, . Nowadays, the main approach to increase is the introduction of nanoscaled defects (artificial pinning centres) in the YBCO matrix to immobilize magnetic vortices8–13. The total pinning force, , is enhanced by an increased number of elementary pinning sites of optimised size and distribution14. However, the normal and superconducting (SC) state properties of cuprate materials are strongly governed by hole doping of the superconducting CuO2-planes. Likewise, the elementary pinning strength itself varies with the condensation energy, , per coherence volume which was predicted to peak at the critical doping p* = 0.19 where the pseudogap closes15. In16 it was reported that the mean field value of the heat capacity jump at the critical temperature, , and therefore the condensation energy, increases up to the maximum oxygen stoichiometry O7, beyond optimal doping, in bulk YBCO. More recently, a strong increase of , between the optimal doping (p = 0.16) and p* was found by measurements of the critical fields17,18. These results further emphasize the enhancement of by overdoping YBCO (as confirmed by results of the doping level), which motivated the interest of early studies to achieve overdoped YBCO films19–23. Nevertheless, demonstration of overdoping of YBCO films by oxygen doping has been quite scare up to now.

In this work, we have reached the overdoped state by oxygen post-processing of YBCO thin films with a thickness of 200 and 250 nm, grown from pulsed laser deposition (PLD) and chemical solution deposition (CSD), respectively. We show the influence of oxygen doping on the charge carrier concentration determined by Hall effect measurements all the way to the overdoped state. We find that strongly increases with charge carrier density, far into the overdoped state where a large Fermi surface of well-defined quasiparticles exists24. We demonstrate that overdoped YBCO films achieve record values of 90 MA/cm2 at 5 K self-field, reaching a fifth of the depairing current density. Our results are in line with recent proposals of the controversial extrapolation of the pseudogap line, its relationship with the Quantum Critical Point and a Fermi Surface reconstruction at the critical point25–27, which are crucial issues to understand the nature of high-Tc superconducting cuprates, particularly the overdoped state. We foresee the hybridization of overdoping and nanoengineering of HTS-CC as an emerging opportunity to significantly improve CC performances for a broad range of superconducting energy applications.

Results

Normal state electrical properties and doping state of YBCO thin films

Normal state electrical properties of cuprate superconductors strongly vary with doping. Underdoped YBCO thin films were obtained by using oxygen partial pressure below 1 bar during the post growth oxygenation process. Overdoped YBCO films were achieved by post-growth oxygen heat treatments at low temperatures, enabled by catalytically activated surface oxygen exchange, using a thin Ag surface decoration layer (for details see Supplementary Information SI-Fig. 1). The catalytic effect occurs via a job sharing mechanism where Ag dissociates the molecular oxygen and YBCO incorporates the oxygen ion into the bulk28. Electrical resistance and Hall measurements as a function of temperature have been employed in addition to room temperature c-parameter analysis to determine the doping state of the studied films. Representative examples of the temperature dependence of the Hall resistance and the electrical resistivity at different magnetic fields are given in Fig. 1 for our films. We have inferred the charge carrier density by Hall measurements at constant magnetic field (3 T) and sweeping temperature (SI-Fig. 2). We observe a strong temperature dependence of , respectively , as previously reported for HTS cuprates29,30, with a maximum of around 100 K as shown in Fig. 1a. A similar drop of below 100 K in underdoped YBCO was recently explained by a reconstruction of the Fermi surface in the normal state due to charge-density-wave order31,32. However, in the present case the downturn in , which is also observed in optimally and overdoped YBCO, is caused by the onset of superconductivity, as the applied magnetic field ( T) is too weak to suppress the occurring phase transition to the superconducting state. In this work, we use the charge carrier density extracted at 100 K to study the correlation with superconducting properties, such as the critical current density.

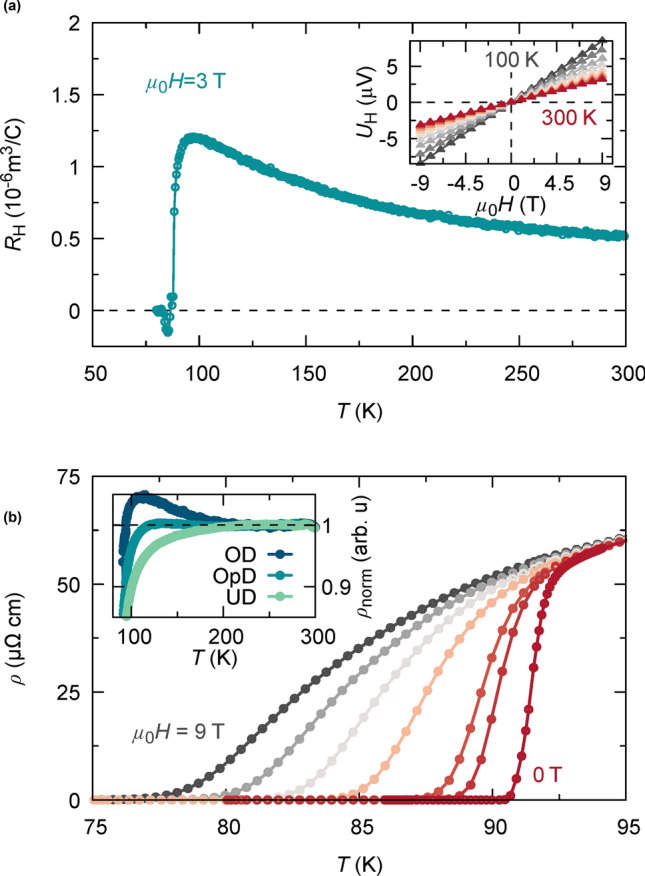

Figure 1.

Electrical analysis of YBCO thin films. (a) Hall constant obtained at 3 T as a function of temperature. is perfectly linear within the analysed field range (− 9 to 9 T) and vanishes in zero field condition at all T as shown in the inset. Charge carrier density is obtained via Hall effect measurements using . (b) In-plane resistivity, , as a function of temperature at different magnetic fields (0, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 T, to evaluate the field dependent superconducting transition temperature, . Inset shows normalized resistivity, , where is the linear slope at high temperatures (. Doping dependent deviation from unity is observed, as shown for an underdoped (UD, downwards deviation), optimally doped (OpD) and overdoped (OD, upwards bending) 200 nm thick YBCO film, respectively.

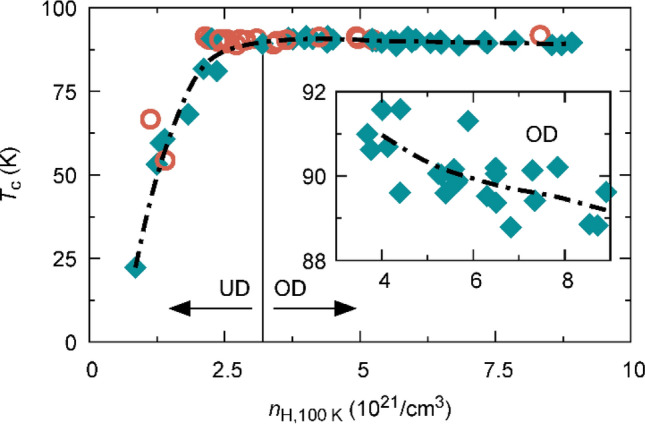

Figure 2.

Phase diagram of YBCO thin films. Zero field critical temperature as a function of charge carrier density, , obtained by Hall effect measurements at 100 K for thin YBCO films grown by PLD (200 nm thick, cyan diamonds) and CSD (250 nm thick, red circles). Vertical line marks optimally doping, while arrows indicate underdoped (UD) and overdoped (OD) regime. Inset magnifies in the overdoped regime, showing a weak but distinct decrease with increasing charge carrier density, from above 91 K to around 89 K.

The resistivity, in Fig. 1b reveals a broadening of the superconducting transition width with increasing magnetic field. From measurements we have inferred the coherence length, , and a characteristic magnetic field, , as discussed below. The deviation of from a linear temperature dependence at low T is shown in the inset of Fig. 1b which correlates with under- and overdoping, respectively, consistent with previous reports33.

Figure 2 displays the critical temperature as a function of the Hall number, , measured at 100 K. rapidly increases at low values of , as expected from the parabolic dependence of on doping generally found in cuprate superconductors34 (assuming direct proportionality between the charge carrier density and doping in the underdoped region). Above the optimal doping of about /cm3, decreases, but following a much weaker dependence, as shown in the inset. This deviation from a parabolic dependence of was reported previously33 and can be explained by an analysis of the doping dependence of the charge carrier density, as performed in the following.

In the underdoped regime, we calculated from measurements of using the parabolic dependence with K, generally found for cuprates. However, this method was found insufficient for optimally and overdoped thin films. Hence, for these higher doped films we determined the doping number from measurements of the -parameter by HR-XRD, as described in the methods (see also SI-Fig. 3a,b).

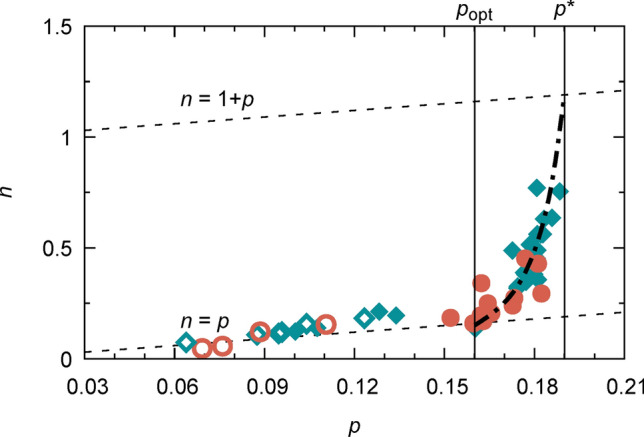

In Fig. 3 we plot the evolution of the charge carrier density, , at T = 100 K with doping, . Here we use the charge carrier density per Cu in the CuO2-planes, , with the volume of the unit cell (the factor ½ is owing to the fact that YBCO has two CuO2-planes per unit cell). In this calculation, we assumed a constant = 0.173 nm3, owing to the fact that in the range of oxygen doping explored, the variation in is rather small (< 1%)35 while large variations in occur. We notice that although the same general behaviour is observed for both types of films, both reaching the overdoped state, PLD films could usually reach a higher oxygenation state than CSD. This could probably be associated to different oxygenation kinetics affecting the microstructure of the film (strain, defects, etc.). For p < 0.16, we find in a broad doping range (underdoped regime). Above optimal doping (p > 0.16), sharply increases. A similar result was reported previously, where was measured at low temperatures using very high magnetic fields suppressing the superconducting state (e.g. at 50 K and up to 88 T)31. This can be understood by a Fermi surface reconstruction (FSR) in proximity to the pseudogap (PG) critical point at p*, resulting in a non-unique relation between the charge carrier density, , and doping, , over the full range of the cuprate phase diagram27. In the far overdoped regime, cuprate superconductors have been recently shown to exhibit a large cylindrical Fermi Surface (FS) with in the zero temperature limit31,32,36,37. Below the critical doping, the volume of the FS reduces by one hole per Cu in the CuO2 plane to , e.g. due to the introduction of an antinodal gap opening which seems to arise from short range antiferromagnetic correlations in the system25. This transition is expected to occur within a narrow doping range between the optimal doping and the closing of the PG at the critical doping , as observed in our study. The PG critical point at p* has been shown to have all the features of a quantum critical point at 38.

Figure 3.

Evolution of the charge carrier density with doping. YBCO normal state charge carrier density per CuO2-plane, n, is drawn as a function of doping . The charge carrier density is given by at 100 K. The doping is obtained for optimally and overdoped samples (full symbols) via HR-XRD measurements of the -parameter and for underdoped films (open symbols) from the parabolic doping dependence of . The vertical lines indicate optimally and critical doping. Below we find , corresponding to a Fermi-surface with small hole and/or electron pockets in the underdoped regime. For a large, cylindrical FS is expected in the metallic overdoped regime, with . A transition between a small and a large Fermi-surface occurs above . This is in good agreement with previous reports, but remarkable, as within this work is obtained by Hall effect measurements using small fields above the onset of superconductivity at 100 K.

It is remarkable that the charge carrier density measured at 100 K, above the onset of superconductivity, preserves the expected behaviour for of a single band metal with a Fermi-surface containing small hole-like pockets on the underdoped site and a sharp transition towards a large Fermi-volume, due to a reconstruction of the Fermi surface, in overdoped YBCO. The latter is also the reason for the observed deviation from a parabolic doping dependence of on , shown in Fig. 2.

Superconducting properties of YBCO films: Correlation with doping and condensation energy

The main result of this work is shown in Fig. 4, where we plot the inductive critical current density, , as a function of in (a) at self-field and (b) at an applied magnetic field of 7 T, determined by magnetisation measurements at 5 K (SI-Fig. 4). For both cases, we find a strong increase of with , extending beyond optimal doping, far into the overdoped regime up to the equivalent value of p* = 0.19 (corresponding values for optimal and critical doping are indicated with vertical dashed lines). Notice the ultrahigh values of inductive at self-field and 5 K, , achieved beyond optimal doping up to p*.

Figure 4.

Dependence of on charge carrier density: Self-field inductive critical current density, , at 5 K versus charge carrier density in (a) self-field and (b) an applied magnetic field of 7 T of YBCO thin films obtained by CSD (red circles, 250 nm) and PLD (cyan diamonds, 200 nm). The critical current density is determined by SQUID magnetisation measurements. is strongly enhanced by increasing the charge carrier density far into the overdoped regime. Optimal and critical doping, and , are marked with vertical lines, while the shadowed area around indicates the uncertainty of defining the critical doping in terms of via Fig. 3. Error bars correspond to uncertainties in film thickness.

An evaluation of the depairing current within the Ginzburg–Landau theory39 is done in the following in order to compare the obtained experimental values with this theoretical limit, though strictly valid only near :

| 1 |

with the temperature and material dependent magnetic penetration depth and coherence length , the flux quantum and the reduced temperature . Using values for as reported in40 for YBCO bulk and as obtained within this work, we can estimate for optimally and overdoped YBCO, as shown in Table 1. The ratio for YBCO thin films analysed within this work, approximately doubles from ~ 9% to ~ 18% going from optimally to overdoped (p = p*), and further evidences the relevance of going to the overdoped state. The maximum obtained within this study is 89.4 MA/cm2, reaching about a fifth of the fundamental limit. To the best of the authors knowledge, this is among the highest inductive values reported for REBCO thin film superconductors at zero field41–45. We suggest, that this increase of in YBCO films with the charge carrier density up to p* is a consequence of the increase of the condensation energy with charge carrier density, as shown in the following.

Table 1.

Estimation of the ratio of critical current density of this work, , over depairing critical current density, . and obtained within this work, from40 and calculated using Eq. (1).

| ξ(0) (nm) | λ(0) (nm) | (MA/cm2) | (MA/cm2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal doped | 1.7 | 134 | 30 | 330 | 9% |

|

Overdoped (p = p*) |

1.6 | 112 | 90 | 500 | 18% |

Vortex matter in HTS cuprates has demonstrated to be extremely rich with new vortex phases that were not expected from the low temperature superconductivity knowledge46–48, specially related to the high thermal energy and flux creep phenomena49 that these cuprates experience. In this context, the pinning energy (which is proportional to the condensation energy, 41) can be related to an effective activation energy determined from magnetoresistance measurements, which can be written generally as 50, where is a constant close to unity and a material dependent parameter. The characteristic magnetic field is proportional to the pinning energy, and thus closely related to the condensation energy23. We have obtained by analysing the vortex glass transition line, given by the empirical formula 51–53, with , where is the critical temperature at zero field and the field dependent vortex-glass transition temperature. We find that depends on the Hall number, as shown in Fig. 5a. As increases from to /cm3, doubles from to T. Thus, suggesting an increase of the condensation energy,, of the order of a factor two within this doping range. This is in agreement with the trend observed from the analysis of the condensation energy, , determined from measurements of the specific heat jump in Bi221254 and YBCO55, and the upper and lower critical fields, and in YBCO17, which can be correlated, according to BCS theory, to the zero temperature condensation energy per unit volume, and . In these two cases, also approximately doubles from optimal to the critical doping17,56. In the inset of Fig. 5a we report a linear dependence of on , which reinforce the condensation energy,, as the underlying quantity governing both parameters, thus further suggesting .

Figure 5.

Charge carrier density dependence of superconducting parameters: (a) Characteristic magnetic field, , versus charge carrier density at 100 K. is obtained by electrical measurements of the vortex glass transition line. It provides a measure of the pinning energy and thus is closely linked to the superconducting condensation energy, . The red diamond is reproduced from23 (280 nm, PLD), falling on the same line as our results. Inset shows versus , revealing a linear relation between these independently measured quantities. This emphasizes the strong correlation of the critical current density and the condensation energy. Dashed line is a guide to the eye. (b) Superconducting coherence length as a function of Hall number at 100 K. is obtained by electrical measurements of , determined from flux flow resistivity analysis up to 9 T (SI-Fig. 5b). A weak decrease with increasing charge carrier doping is observed, which alone cannot account for the strongly enhanced in the overdoped region. y-error bars correspond to uncertainties from the underlying fit procedures.

To verify the plausibility of our results, we analyse the expected relationship between the depairing current density, , the condensation energy, and the charge carrier density, . Therefore, we consider the condensation energy per pair , which is equal to the critical kinetic energy at zero temperature:

| 2 |

with the depairing critical velocity of a pair and the mass of the electron pair. The condensation energy per pair is equal to the condensation energy per unit volume divided by the superconducting pair density , hence . Using the critical velocity, we can generally write the depairing critical current density as

| 3 |

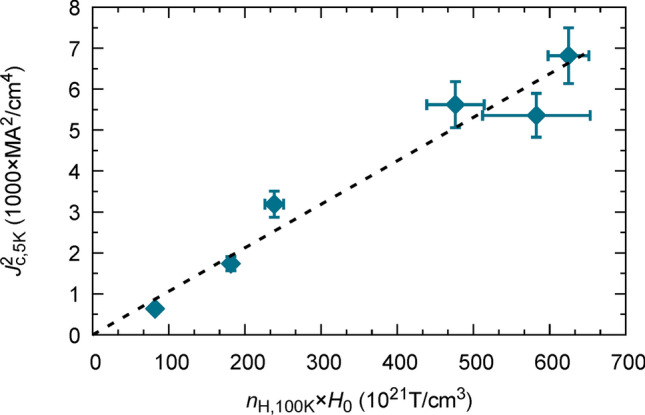

Combining Eq. (2) and (3) we obtain

| 4 |

Therefore, we expect that the square of the depairing critical current density varies as the superconducting pair density multiplied by the condensation energy. We further assume that varies with the measured Hall carrier density . Therefore, we expect that going from optimal doping to the highest achieved over-doping, increases by a factor of 3, while increases by a factor of 2. From the derived expression, the depairing critical current density is expected to increase over that range by a factor of 2.5, which is consistent with our results reported in Fig. 4a, suggesting that the measured self-field inductive critical current density varies similarly to the depairing critical current density. Equation 4 is experimentally verified in Fig. 6 with , and experimentally determined values. Thus, we believe that the increase of with ultrahigh critical currents up to p* is fully consistent with an increase of the condensation energy, , in YBCO films, in agreement with previous results determined from specific heat56 and critical fields17 measurements. Some of these works have suggested the existence of a peak in the condensation energy , and thus in the density of states, , at p* when the PG closes and cuprates enter the strange metal state before reaching the Fermi liquid behaviour15,17,27,56. This is one of the features of a QCP irrespective of the details of the microscopic model used to describe the PG formation23,27,57,58. Unfortunately, this has been measured up to now only in Ca-doped YBCO and La1.8-xEu0.2SrxCuO427 and iron-pnictide superconductors59–62, but it could suggest a universal behaviour. It would be very interesting to be able to overdope these YBCO films beyond the present p* value to confirm also the peak in .

Figure 6.

Experimental verification of Eq. (4), , using . The three parameters , and are derived experimentally, in this work, from independent measurements.

In this work, we have evaluated the self-field inductive from saturated SQUID magnetization curves, to ensure being in the vortex pinning regime63,64, which is further confirmed by the strong increase of also for 7 T (Fig. 4b). Hence, variations of the coherence length might contribute to the increase of the critical current, as the pinning energy, , scales with 56 and the coherence length itself exhibits a dependence on doping65–67. To be able to exclude that a major contribution arises from changes in , we have analysed for several samples spanning a broad doping range, as shown in Fig. 5b. is extracted from electrical measurements of the flux flow resistivity up to 9 T as described in68–70. We observe only a small variation of , while the Hall number changes by more than a factor 4. Thus, the enhancement due to this modified coherence length would account for an upper limit of 25%, much less than the observed increase of > 300% within the doping range from to /cm3. Thus, we conclude that the enhancement of observed is mainly governed by the modified condensation energy due to the increase of oxygen doping.

Consequences in pinning behaviour and comparison with nanoengineered films

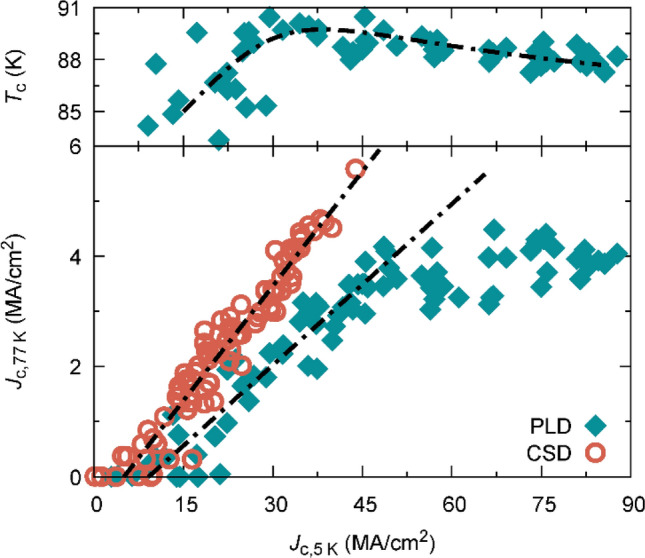

YBCO films are very sensitive to atomic and nanoscale defects due to the small coherence length in high temperature superconductors, which in addition leads to strong thermal fluctuations, especially at high temperatures, which strongly hinder vortex pinning. The consequence is that very different behaviour is observed for different pinning centres at different temperatures. While columnar defects are more advantageous at high temperatures, weak uncorrelated pinning sites strongly contribute to the overall pinning force at reduced temperatures41,71. The effect of random point defects is observed to be more significant at low temperatures10. vs is shown in Fig. 7 for films grown by PLD and CSD. In both types of samples, we observe a strong correlation between at the two different temperatures up to about MA/cm2. However, CSD and PLD films follow different trends, which may be attributed to different pinning efficiencies associated to two different microstructures. CSD films typically preserve a much stronger distorted matrix, giving raise to strong pinning in strained regions, being more efficient at higher temperatures12. Above MA/cm2, PLD films show a deviation from the initial linear relation with , resulting in a much weaker dependence ( increases from 3 to 4 MA/cm2, while almost doubles from 50 to 90 MA/cm2). We propose that this saturation is caused by the reduced efficiency of weak pinning sites at high temperatures. Notice, in Fig. 7 upper panel, the consistency of with self-field , further demonstrating the intrinsic relationship of these two magnitudes with the charge carrier density (Figs. 7, 8).

Figure 7.

Superconducting physical properties correlations for PLD and CSD films. dependence with self-field inductive (upper panel) showing the intrinsic relation of both quantities with the charge carrier density. Self-field as a function of self-field for YBCO films obtained by PLD and CSD (lower panel). The different linear trends for <50 MA/cm2 reveal growth dependent pinning defect landscapes, with possibly higher strong-pinning contribution in CSD films. With increasing in PLD films, saturates, probably due to a reduced contribution of weak pinning at high temperatures and the proximity to the superconducting transition in the overdoped regime, as indicated in the upper panel by a decreased for high films. All lines are guide to the eye.

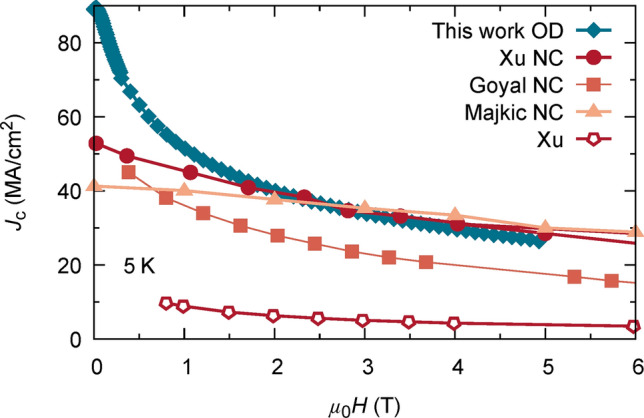

Figure 8.

at 5 K of some best performing YBCO films. Field dependence of reported high critical current densities for several nanocomposite (NC) YBCO thin films in comparison with overdoped (OD) YBCO obtained in this work (PLD). Overdoped YBCO exhibits a remarkable self-field inductive , almost 60% higher than previous record films, compensating the fast decrease of at low fields as typical for pristine YBCO films. From literature reproduced results cover the currently best-practice strategies of nanoengineering YBCO of coated conductors: 15% Zr doped (Gd,Y)BCO (Xu NC, MOCVD, at 4.2 K, reproduced under CC-BY)42, nanoscale defected REBCO with 4% BZO (Goyal NC, PLD, at 5 K, reproduced under CC-BY)78, REBCO with 15% Zr addition (Majkic NC, MOCVD, at 4.2 K, raw data was kindly provided by the author)79. Additionally we show a pristine YBCO film (Xu, MOCDV, at 4.2 K, reproduced with permission from AIP publishing) as reported in72.

The strong increase of with doping motivates for a comparison of the in-field properties with reported values from other optimized approaches, including the more recent nanoengineering of the microstructure by the embedding of nanoparticles and nanorods in HTS films and coated conductors. at low temperatures is shown in Fig. 8 for various different samples (see Figure caption for details on sample composition). The most striking feature is the strong enhancement of the inductive at self-field () in the overdoped film, compared to conventional approaches by nanodefecting the matrix, as discussed above. Up to T, overdoping enables an outstanding increase of . Weak pinning, the expected main contribution in pristine YBCO films, is known to rapidly decrease with small magnetic fields10, explaining the rapid decrease of below 1 T for the overdoped PLD sample. However, the extraordinary high self-field inductive asserts high at even intermediate fields, comparable to the best performing nanocomposites, whose pinning is governed by 1D nanorods and strained regions around 3D nanoparticles. We also show a representative example of a pristine optimally doped YBCO film, as reported in72, highlighting the potential of overdoping YBCO. We notice that in this study, was obtained by magnetisation measurements, so these results should better be compared with other inductive measurements, but we want to stress that typically, inductive measurements do suffer from extensible flux-creep effects specially at high magnetic field. Therefore, we encourage future work achieving the overdoped state in nanoengineered films to reach ultrahigh critical current densities also at high magnetic fields.

Discussions

We have fabricated overdoped YBCO thin films by means of different post-processing oxygen heat treatments being able to tune the doping state and reach the critical doping value p* = 0.19, close to the Quantum Critical Point. The overdoped state is confirmed by a small decrease of and a transition of the normal state charge carrier density from to , where p is the doping state of the Cu2O planes, in agreement with the proposed reconstruction of the Fermi surface above optimal doping (p = 0.16). However, this result is remarkable, as was obtained above the onset of superconductivity at 100 K, preserving the expected behaviour from the limit . We suggest that low temperature measurements at high fields, necessary to suppress superconductivity, would be highly interesting to reveal the further temperature evolution of in these thin films.

The evaluated overdoped regime is characterised by an increase of the condensation energy, leading to extraordinary self-field values at low temperatures, up to one fifth of the depairing current, reaching 90 MA/cm2 at 5 K. We experimentally demonstrate a strong increase of with the charge carrier density, , at self-field and high magnetic fields of 7 T up to the critical point p*, and we verified the theoretical relation between , and (Eq. 4) from three independent experimental parameters. The distinct behaviour of observed at 5 K and 77 K, suggests that we have been able to modify the weak pinning individual strength through the modification of the condensation energy by doping. p-doping strategies with oxygen post-processing treatments are expected to be scalable and uniform in long length, therefore, we envisage a viable hybridisation of overdoping and nanoengineering of YBCO films, which offers powerful prospects to further push prevailing limitations of dissipation-free current transport in cuprate superconductors and Coated Conductors at high magnetic fields of interest for applications. We reinforce the interest to find ways to overdope YBCO films beyond the present critical value p* to confirm the existence of a peak in condensation energy, , at higher doping levels and shine light on the consequences of crossing the Quantum Critical Point.

Methods

Film fabrication

The YBa2Cu3O7-δ thin films are grown using chemical solution deposition (CSD) and pulsed laser deposition (PLD) on 5 × 5 mm2 LaAlO3 (100) and SrTi O3 (100) single crystal substrates with thicknesses of 200 nm (PLD) and 250 nm (CSD), respectively. In case of CSD, the stoichiometric amount of precursor metal trifluoroacetate salts is dissolved in an alcoholic solution and deposited by spin-coating, followed by a pyrolysis (∼300 °C) and growth (∼800 °C) temperature treatment at PO2 = 0.2 mbar73,74. PLD layers are deposited at 800 °C at PO2 = 0.3 mbar with a pulse frequency of 5 Hz75. The PLD-targets were fabricated by Oxolutia SL (Spain) and consist of pressed and sintered, stoichiometric YBCO powder at 87% density. After growth, a 100 nm thick surface decoration layer of patterned Ag is deposited on the surface by sputtering at RT (SI-Fig. 1a). This Ag layer catalytically enhances oxygen exchange activity of YBCO during the following oxygenation process, as a job sharing mechanism facilitates the dissociation and incorporation of O2 (SI-Fig. 1b)28,76. Additionally, the silver coating provides good electrical contact for electrical measurements. Dewetting of the Ag layer into small islands with diameters of about 0.1 µm is observed at around 300 °C. However, this effect is not detrimental to its catalytic activity nor electrode functionality. Hole doping of YBCO is achieved by oxygen incorporation during the post growth oxygenation at 1 bar with an oxygen flux density of 0.16 l min-1 cm-2 at different intermediate temperatures (280–550 °C) with dwell times between 30 and 240 min.

Structural characterisation

Layers obtained by either growth technique are epitaxial textured, twinned and highly c-axis oriented with no trace of secondary phases, as determined by X-ray diffraction measurements (Bruker D8 Discover), as shown in SI-Fig. 3a. In the presented films with thicknesses above 200 nm, no macroscopic strain due to lattice mismatch with the used substrates (LaAlO3 and SrTiO3) was observed.

The c-lattice parameter is obtained by HR-XRD measurements using the Nelson–Riley method, which allows the determination of the lattice parameter with very high precision, as aberration errors are minimised at very high angles (see SI-Fig. 3b). For optimally and overdoped films, we determined the doping number via the c-parameter, using the empirical equation with 20,77. The prefactors depend on the sample type and growth process. In this work we have used values reported in77 (, , ). A small systematic constant offset was corrected by introducing the additional parameter .

Magnetic and electrical analysis

SQUID magnetometry (Quantum Design) was used to determine critical current densities via the width of the magnetisation loop, as explained in SI-Fig. 4a, using the Bean critical state model for thin discs.

In-depth electrical analysis was performed using a Physical Property Measurement System (Quantum Design) over a broad temperature range. Contacts for electrical measurements were glued with silver paint on top of 400 µm squared Ag electrodes sputtered at the corners of the films. Electrical measurements were performed in Van der Pauw and Hall configuration in fields up to 9 T , averaged over two permutations of the electrical contacts and positive and negative excitation current in DC mode. The studied YBCO films are highly twinned, therefore the influence of metallic CuO chains short circuiting the Hall voltage along the b-direction is neglected in the calculation of the Hall coefficient . The critical temperature at zero field, , and the field dependent vortex-glass transition temperature, , are determined from measurements to the point where the electrical resistance in response to a small excitation current vanishes. The vortex-glass transition line is used to obtain the characteristic magnetic field, , by linear fitting as explained in SI-Fig. 5a. From the same measurements, we were able to determine the upper critical field, , and in the zero temperature limit, , using the classical Werthamer-Helfand-Hohenberg relation, which in turn defines the coherence length, . The determination of is shown in SI-Fig. 5b.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness through the “Severo Ochoa” Programme for Centres of Excellence in R&D (Grant No. SEV-2015-0496), the EU ULTRASUPERTAPE (ERC-2014-ADG-669504) and EUROTAPES project (FP7-NMP-Large-2011-280432), and the Spanish CONSOLIDER Excellence Network (Grant No. MAT2015-68994-REDC), COACHSUPENERGY project (Grant No. MAT2014-56063-C2-1-R) and SuMaTe project (RTI2018-095853-B-C21), both cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund, and from the Catalan Government with Grant No. 2014-SGR-753 and 2017-SGR-1519. Authors also thank the network collaboration of EU COST action NANOCOHYBRI CA16218.We also acknowledge the Scientific Services at ICMAB. We thank Juri Banchewski for some of the last transport experiments. A.S. is grateful for illuminating discussions on the manuscript with Stephan Steinhauer (KTH, Sweden).

Author contributions

A.S., A.P. and T.P designed the experimental study. A.S. performed the experimental work and analysed the data. A.S. prepared the manuscript with contributions from co-authors. All authors contributed to the scientific discussion.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

A. Stangl, Email: alexander.stangl@grenoble-inp.fr

T. Puig, Email: teresa.puig@icmab.es

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-87639-4.

References

- 1.Rogalla H, Kes PH. 100 Years of Superconductivity. Taylor & Francis; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiohara Y, Taneda T, Yoshizumi M. Overview of materials and power applications of coated conductors project. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2012;51:010007. doi: 10.1143/JJAP.51.010007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haugan TJ, Puig T, Matsumoto K, Wu J. Artificial pinning centers in (Y, RE)-Ba-Cu-O superconductors: Recent progress and future perspective. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2020;33:040301. doi: 10.1088/1361-6668/ab4ccd. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obradors X, et al. Comprehensive Nanoscience and Technology. Elsevier; 2011. Nanostructured superconductors with efficient vortex pinning; pp. 303–349. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obradors X, Puig T. Coated conductors for power applications: Materials challenges. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2014;27:044003. doi: 10.1088/0953-2048/27/4/044003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larbalestier DC, Gurevich A, Feldmann DM, Polyanskii A. High-Tc superconducting materials for electric power applications. Nature. 2001;414:368–377. doi: 10.1038/35104654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Civale L. Pushing the limits for the highest critical currents in superconductors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019;116:10201–10203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905568116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haugan T, Barnes PN, Wheeler R, Melsenkothen F, Sumption M. Addition of nanoparticle dispersions to enhance flux pinning of the YBa2Cu3O7-x superconductor. Nature. 2004;430:867–870. doi: 10.1038/nature02792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacManus-Driscoll JL, et al. Strongly enhanced current densities in superconducting coated conductors of YBa2Cu3O7-x + BaZrO3. Nat. Mater. 2004;3:439–443. doi: 10.1038/nmat1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutiérrez J, et al. Strong isotropic flux pinning in solution-derived YBa2Cu3O7-x nanocomposite superconductor films. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:367–373. doi: 10.1038/nmat1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang S, et al. High-performance high-Tc superconducting wires. Science. 2006;311:1911–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.1124872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llordés A, et al. Nanoscale strain-induced pair suppression as a vortex-pinning mechanism in high-temperature superconductors. Nat. Mater. 2012;11:329–336. doi: 10.1038/nmat3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soler L, et al. Ultrafast transient liquid assisted growth of high current density superconducting films. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13791-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadovskyy IA, Koshelev AE, Kwok W, Welp U, Glatz A. Targeted evolution of pinning landscapes for large superconducting critical currents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019;116:10291–10296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1817417116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tallon JL, Loram JW. Doping dependence of T* - what is the real high-Tc phase diagram? Phys. C Supercond. its Appl. 2001;349:53–68. doi: 10.1016/S0921-4534(00)01524-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deutscher G. New Superconductors: From Granular to High T C. World Scientific; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grissonnanche G, et al. Direct measurement of the upper critical field in cuprate superconductors. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talantsev EF, et al. Oxygen deficiency, stacking faults and calcium substitution in MOD YBCO coated conductors. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2013;23:1–4. doi: 10.1109/TASC.2012.2233843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talantsev EF, et al. Hole doping dependence of critical current density in YBa2Cu3O7-δ conductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014;104:242601. doi: 10.1063/1.4883483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arpaia R, Andersson E, Trabaldo E, Bauch T, Lombardi F. Probing the phase diagram of cuprates with YBa2Cu3O7-δ thin films and nanowires. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2018;2:024804. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.2.024804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baghdadi R, et al. Fabricating nanogaps in YBa2Cu3O7−δ for hybrid proximity-based josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2015;4:014022. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.4.014022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strickland NM, Semwal A, Williams GVM, Verebelyi DT, Zhang W. Optimizing the doping state of YBCO coated conductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2004;17:S473–S476. doi: 10.1088/0953-2048/17/9/002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naqib SH, Islam RS. Possible quantum critical behavior revealed by the critical current density of hole doped high-T c cuprates in comparison to heavy fermion superconductors. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51467-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vignolle B, et al. Quantum oscillations in an overdoped high-Tc superconductor. Nature. 2008;455:952–955. doi: 10.1038/nature07323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doiron-Leyraud N, et al. Pseudogap phase of cuprate superconductors confined by Fermi surface topology. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02122-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Storey JG. Hall effect and Fermi surface reconstruction via electron pockets in the high-Tc cuprates. EPL. 2016;113:2. doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/113/27003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proust C, Taillefer L. The remarkable underlying ground states of cuprate superconductors. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2019;10:409–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031218-013210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stangl, A. PhD Thesis on Oxygen kinetics and charge doping for high critical current YBCO films. (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2019). ISBN: 9788449087103. URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/667212.

- 29.Ando Y, Lavrov AN, Komiya S, Segawa K, Sun XF. Mobility of the doped holes and the antiferromagnetic correlations in underdoped high-Tc cuprates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;87:1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.017001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wuyts B, Moshchalkov VV, Bruynseraede Y. Resistivity and Hall effect of metallic oxygen-deficient YBa2Cu3Ox films in the normal state. Phys. Rev. B. 1996;53:9418–9432. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.53.9418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badoux S, et al. Change of carrier density at the pseudogap critical point of a cuprate superconductor. Nature. 2016;531:210–214. doi: 10.1038/nature16983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collignon C, et al. Fermi-surface transformation across the pseudogap critical point of the cuprate superconductor La1.6-xNd0.4SrxCuO4. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;95:224517. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.224517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castro H, Deutscher G. Anomalous Fermi liquid behavior of overdoped high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2004;70:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tallon JL, Bernhard C, Shaked H, Hitterman RL, Jorgensen JD. Generic superconducting phase behavior in high-T, cuprates: T, variation with hole concentration in YBa2C3O7-delta. Phys. Rev. B. 1995;51:911–914. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.51.12911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jorgensen JD, et al. Structural properties of oxygen-deficient YBa2Cu3O7-d. Phys. Rev. B. 1990;41:1863. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.41.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He Y, et al. Fermi surface and pseudogap evolution in a cuprate superconductor. Science. 2014;344:608–611. doi: 10.1126/science.1248221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujita K, et al. Simultaneous transitions in cuprate momentum-space topology and electronic symmetry breaking. Science. 2014;344:612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1248783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tallon JL, et al. Critical doping in overdoped high-Tc superconductors: A quantum critical point? Phys. Status Solidi. 1999;215:531–540. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3951(199909)215:1<531::AID-PSSB531>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tinkham M. Introduction to Superconductivity. McGraw-Hill; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sonier JE, et al. Hole-doping dependence of the magnetic penetration depth and vortex core size in YBa2Cu3Oy: Evidence for stripe correlations near 1/8 hole doping. Phys. Rev. B. 2007;76:134518. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.76.134518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwok W, et al. Vortices in high-performance high-temperature superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2016;79:116501. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/79/11/116501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu A, et al. Strongly enhanced vortex pinning from 4 to 77 K in magnetic fields up to 31 T in 15 mol.% Zr-added (Gd, Y)-Ba-Cu-O superconducting tapes. APL Mater. 2014;2:046111. doi: 10.1063/1.4872060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang J, et al. Enhanced flux pinning properties in YBa2Cu3O7−δ/(CoFe2O4)0.3(CeO2)0.7 multilayer thin films. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2015;25:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang F, Tian H. BaZrO3 (BZO) nanoparticles as effective pinning centers for YBa2Cu3O7 − δ (YBCO) superconducting thin films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019;30:4137–4143. doi: 10.1007/s10854-019-00705-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang J, et al. Enhanced flux pinning properties of YBCO thin films with various pinning landscapes. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2017;27:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blatter G, Feigel’Man MV, Geshkenbein VB, Larkin AI, Vinokur VM. Vortices in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1994;66:1125–1388. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.66.1125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crabtree GW, Nelson DR. Vortex physics in high-temperature superconductors. Phys. Today. 1997;50:38–45. doi: 10.1063/1.881715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Figueras J, et al. The loss of vortex line tension sets an upper limit to the irreversibility line in YBa 2 Cu 3 O 7. Nat. Phys. 2006;2:402–407. doi: 10.1038/nphys311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eley S, Miura M, Maiorov B, Civale L. Universal lower limit on vortex creep in superconductors. Nat. Mater. 2017;16:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nmat4840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu SL, Shao HM, Wang ZH. The activation energy U(T, H) in Er-doped melted textured growth YBa 2Cu3O7-δ crystal. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2007;20:444–447. doi: 10.1088/0953-2048/20/5/006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lundqvist B, Rydh A, Eltsev Y, Rapp A, Andersson M. Empirical scaling of the vortex glass line above 1 T for high superconductors of varying anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B. Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1998;57:14064. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.57.R14064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rydh A, Rapp A, Andersson M. Consistent description of the vortex glass resistivity in high- Tcsuperconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999;83:1850–1853. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.1850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andersson M, Rydh A, Rapp A. Scaling of thevortex-liquid resistivity in optimally doped and oxygen-deficient YBa2Cu3O7−δsingle crystals. Phys Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2001;63:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loram JW, Luo J, Cooper JR, Liang WY, Tallon JL. Evidence on the pseudogap and condensate from the electronic specific heat. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2001;62:59–64. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3697(00)00101-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Junod A, Roulin M, Revaz B, Erb A. Experimental survey of critical fluctuations in the specific heat of high-temperature superconductors. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 2000;280:214–219. doi: 10.1016/S0921-4526(99)01581-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deutscher G. Impact of pseudo-gap states on the pinning energy and irreversibility field of high temperature superconductors. APL Mater. 2014;2:096108. doi: 10.1063/1.4894781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norman MR, Pines D, Kallin C. The pseudogap: Friend or foe of high Tc? Adv. Phys. 2005;54:715–733. doi: 10.1080/00018730500459906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daou R, et al. Broken rotational symmetry in the pseudogap phase of a high-Tc superconductor. Nature. 2010;463:519–522. doi: 10.1038/nature08716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kurth F, et al. Unusually high critical current of clean P-doped BaFe2As2 single crystalline thin film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015;106:2. doi: 10.1063/1.4908257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Putzke C, et al. Anomalous critical fields in quantum critical superconductors. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:1–6. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ishida J, Iimura S, Hosono H. Effects of disorder on the intrinsically hole-doped iron-based superconductor KC a2 F e4 A s4 F2 by cobalt substitution. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;96:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hashimoto K, et al. A sharp peak of the zero-temperature penetration depth at optimal composition in BaFe2(As1-xPx)2. Science. 2012;336:1554–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1219821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Talantsev E, Crump WP, Tallon JL. Thermodynamic parameters of single- or multi-band superconductors derived from self-field critical currents. Ann. Phys. 2017;529:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Talantsev EF, Tallon JL. Universal self-field critical current for thin-film superconductors. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:2. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ando Y, Segawa K. Magnetoresistance of untwinned YBa2Cu3Oy single crystals in a wide range of doping: Anomalous hole-doping dependence of the coherence length. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;88:4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.167005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tallon L, Loram W, Cooper R, Panagopoulos C, Bernhard C. Superfluid density in cuprate high-Tc superconductors: A new paradigm. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2003;68:1–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.68.180501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wen HH, et al. Hole doping dependence of the coherence length in La2-xSr xCuO4 thin films. Europhys. Lett. 2003;64:790–796. doi: 10.1209/epl/i2003-00627-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gordeev SN, et al. Resistivity of clean YBa2Cu3O7−δ in the pinned-liquid state. Phys. Rev. B. 1999;60:10477–10483. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.60.10477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ivlev BI, Kopnin NB. Flux flow in layered high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 1990;42:10052–10059. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.42.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bartolomé E, et al. Intrinsic anisotropy versus effective pinning anisotropy in YBa2Cu3O7 thin films and nanocomposites. Phys. Rev. B. 2019;100:054502. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.100.054502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blatter G, Geshkenbein VB, Koopmann JAG. Weak to strong pinning crossover. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;92:3–6. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.067009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu A, Jaroszynski J, Kametani F, Larbalestier D. Broad temperature range study of Jc and Hirr anisotropy in YBa2Cu3Ox thin films containing either Y2O3 nanoparticles or stacking faults. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015;106:052603. doi: 10.1063/1.4907891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Obradors X, et al. Progress towards all-chemical superconducting YBa2Cu3O7-coated conductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2006;19:2. doi: 10.1088/0953-2048/19/3/003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Obradors X, et al. Growth, nanostructure and vortex pinning in superconducting YBa 2 Cu 3 O 7 thin films based on trifluoroacetate solutions. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2012;25:123001. doi: 10.1088/0953-2048/25/12/123001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sieger M, et al. Tailoring microstructure and superconducting properties in thick BaHfO3 and Ba2Y(Nb/Ta)O6 doped YBCO films on technical templates. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2017;27:2. doi: 10.1109/TASC.2017.2767139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cayado P, et al. Untangling surface oxygen exchange effects in YBa2Cu3O6+x thin films by electrical conductivity relaxation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:14129–14140. doi: 10.1039/C7CP01855J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liang R, Bonn DA, Hardy WN. Evaluation of CuO2 plane hole doping in YBa2 Cu3 O6+x single crystals. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2006;73:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goyal A, Wee SH. Optimal, nanodefect configurations via strain-mediated assembly for optimized vortex-pinning in superconducting wires from 5K–77K. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017;871:012039. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/871/1/012039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Majkic G, et al. Engineering current density over 5 kA mm2 at 42 K, 14 T in thick film REBCO tapes. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2018;31:10. doi: 10.1088/1361-6668/aad844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.