Abstract

Social dysfunction is a hallmark of schizophrenia that is associated with emotional disturbances. Researchers have employed ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to measure social and emotional functioning in people with schizophrenia. Yet, few studies have evaluated quality of real-world social interactions, and it is unclear how interactions impact emotional experiences in this population. Using novel EMA that passively collects audio data, we examined daily social behavior and emotion in schizophrenia (n=38) and control (n=36) groups. Contrary to hypotheses, both groups interacted with others at the same rate and exhibited similar levels of positive emotion. However, as expected, the schizophrenia group exhibited significantly less high-quality interactions and reported more negative emotion than controls. Social versus non-social context did not influence experienced emotion in either group. This is the first real-world study to passively assess quality of social interactions in schizophrenia. Although those with schizophrenia did not differ in their number of interactions, they were less likely to engage in substantive, personal conversations. Because high-quality interactions are linked with better social outcomes, this finding has important potential treatment implications. Future research should investigate quality of interactions across different types of social activities to gain a more nuanced understanding of social dysfunction in schizophrenia.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, social functioning, emotion, ecological momentary assessment

1. Introduction

Social dysfunction is a core and disabling feature of schizophrenia (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Given its burden, it is vital to accurately identify and measure how people with schizophrenia exhibit social dysfunction in their daily lives. Although multiple definitions of social functioning exist, participation in social interactions and maintenance of interpersonal relationships are consistently referenced as fundamental aspects of this construct (Burns and Patrick, 2007; Figueira and Brissos, 2011; Ro and Clark, 2009). Consequently, two commonly assessed elements of social functioning are frequency of social interactions and quality of interpersonal relationships. Frequency of social interactions is often used as a quantitative measure of social functioning, and involves conversations, activities, and time spent with other people. Compared to healthy people, people with schizophrenia spend less time interacting with others (Brown et al., 2007; Oorschot et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2017). Measuring quality of social relationships offers a more nuanced understanding of social functioning. In this regard, people with schizophrenia display less engagement or involvement during simulated social interactions and report having fewer intimate relationships than healthy people (Blanchard et al., 2015; Kwapil et al., 2009).

Although clinical interviews and laboratory tasks have long been used to assess social functioning in schizophrenia, ecological momentary assessment (EMA) has been frequently implemented in recent years (Mote and Fulford, 2020). The immediacy of EMA protects against retrospective bias and the real-world context in which subjects are assessed increases external validity (Hektner et al., 2007). EMA has widely been used to measure the first element of social functioning, frequency of social interactions (Mote and Fulford, 2020). Yet, less work has used EMA to measure the second element, quality of social relationships. Researchers posit that aspects of one’s interactions with others shape the development of interpersonal relationships (Nisenson et al., 2001). Thus, measuring interaction quality using EMA may allow researchers to better gauge this element of social functioning. Existing EMA studies have estimated quality of interactions by investigating who the subject is interacting with (Granholm et al., 2008), the subject’s performance appraisals of the interaction (Granholm et al., 2013), and contextual factors of social activities (i.e., structured versus unstructured; Kasanova et al., 2018). Although these represent qualitative features of interactions, more definitive measures to identify high-quality versus low-quality interactions are needed. One potential proxy for quality may be found in the content of conversations. People engage in various levels of conversation throughout their day (e.g., small talk, personal disclosures). Research suggests deeper-level conversations lead to greater happiness and well-being (Mehl et al., 2010), and this may be due to their ability to foster closer social connections (Rabin, 2010). Thus, content of conversations is not only an important qualitative aspect of social interactions, but may also strongly influence quality of relationships, the second major element of social functioning. In this way, assessing content of daily conversations as a measure of interaction quality may offer a nuanced understanding of social deficits in schizophrenia.

EMA research has also shown links between social and emotional functioning in those with schizophrenia (Depp et al., 2016; Granholm et al., 2013; Oorschot et al., 2013). Relative to healthy controls, people with schizophrenia exhibit reduced positive and increased negative emotion (Cho et al., 2017). Moreover, laboratory studies of people with schizophrenia show that positive emotion is correlated with more adaptive social functioning (Horan et al., 2008) and negative emotion is associated with worse social functioning, even after accounting for cognitive ability and severity of psychotic symptoms (Grove et al., 2016). Thus, EMA research has investigated emotional experiences within social interactions to better understand impairment in schizophrenia. In line with previous literature, Oorschot et al. (2013) found that people with schizophrenia generally report more negative and less positive emotions compared with healthy controls. However, they reported similar emotional responses when in the company of other people; that is, both people with schizophrenia and controls exhibited increased positive feelings with others. So, it seems people with schizophrenia experience similar emotionality as controls when in social situations. Yet, we know that the social lives of those with schizophrenia drastically differ from the general population; people with schizophrenia spend significantly more time alone (Oorschot et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2017). Thus, differences in positive and negative emotion between those with schizophrenia and healthy controls may be exacerbated by differences in the number of social interactions they participate in daily. It is possible that, when in similar social contexts, differences in emotion between those with and without schizophrenia may be less pronounced. In this way, context (i.e., if the person is in a social interaction) may moderate the relationship between clinical status (schizophrenia versus control) and emotion.

The current project aimed to elucidate the relationship between social functioning and emotion in schizophrenia using two forms of EMA: an active, self-report assessment of momentary emotion and a passive assessment of social interactions using audio recording. This passive method not only lets us objectively measure frequency of daily social interactions, but it also allows for a real-world assessment of the quality of those interactions based on the content of conversation. Data was collected from people with schizophrenia and healthy controls to test two primary hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that clinical status (schizophrenia versus control) would significantly predict social functioning and emotion. Consistent with previous research on social and emotional functioning (Bellack et al., 2007; Barch et al., 2008; Cohen et al., 2012; Strauss et al., 2011; Strauss et al., 2013), we anticipated that those with schizophrenia would exhibit worse social functioning, more negative emotions, and less positive emotions compared to controls. Second, we hypothesized that the relationship between clinical status and emotions would be moderated by context (social versus non-social). This is based on findings that frequency of social interactions has been associated with the experience of positive emotions in the general population (Watson et al., 1992), and people with schizophrenia show similar emotional responses in social situations as controls (Oorschot et al., 2013). This study uniquely contributes to the literature by using passive EMA to measure both quantity and quality of social interactions and is one of the first studies to directly test whether emotional differences found in schizophrenia depend on context (social versus non-social).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Design

Participants in the schizophrenia group (n = 38) were recruited from community mental health centers in Indianapolis, IN and had a primary diagnosis of a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder according to the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.; Sheehan et al., 1998). Other inclusion criteria included: a) age 18–60; b) English fluency; c) no change in medication or outpatient status in the past month; d) ability to give informed consent; e) no active substance dependence; f) no documented intellectual disability; and g) no history of a neurological illness or head injury that resulted in loss of consciousness greater than five minutes. Participants in the control group (n = 36) were recruited via flyers, local healthcare centers, and a volunteer registry. Criteria mirrored the schizophrenia-spectrum group except those who: a) met current criteria for a psychiatric disorder or b) had a history of psychotic symptoms were excluded. Participants who did not do both active and passive EMA protocols were excluded from the current analyses.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The electronically activated recorder (EAR; Mehl, 2007)

The EAR is an application for smartphone devices to collect audio recordings of real-world social interactions. Previous studies have demonstrated its promise for capturing accurate behavioral and clinical information in everyday settings (Pennebaker et al., 2003; Robbins, Mehl et al., 2011). In this study, participants wore the EAR device for two days. This time frame was chosen based on recommendations from the co-creator of the EAR (Mehl, et al., 2012) and findings that two days shows good temporal stability in healthy individuals and convergence with four-week time frames (Mehl et al., 2001; Mehl and Robbins, 2012). The EAR was programed to record for 5 minutes every 90 minutes from 6:00 a.m. to midnight yielding two hours of audio data from each participant. This sampling method allowed us to collect behavioral data from different periods of the day with intervals long enough to capture situational context.

Safeguards were put in place to protect confidentiality: a) subjects could remove the EAR any time they did not wish to be recorded; b) subjects could hear and delete recordings they did not wish to share with the research team; and c) the EAR device included a sign alerting others that it could be recording (i.e., “This device is being used for research purposes. It records nearby surroundings at various intervals and may record your voice”). As in previous studies, less than 1% of files were deleted by participants (Minor et al., 2018; Robbins et al., 2011; Robbins et al., 2014). Additional audio files were excluded from analyses if subjects were sleeping, if there was an audio problem (e.g., inaudible), or if the subject was not wearing the EAR (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, Audio, and Clinical Data of Sample

| Schizophrenia Group (n = 38) | Control Group (n = 36) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | M (SD) | M (SD) | Test statistic | p |

| Age | 46.24 (10.40) | 43.20 (11.92) | t = 1.16 | 0.249 |

| Sex: % Female | 57.9 | 47.2 | χ2 = 0.85 | 0.358 |

| Race: | χ2 = 3.90 | 0.143 | ||

| % White | 34.2 | 57.1 | ||

| % Black | 60.5 | 40.0 | ||

| % Multiracial | 5.3 | 2.9 | ||

| Ethnicity: % Non-Hispanic | 86.8 | 91.7 | χ2 = 1.21 | 0.546 |

| Employment: % Employed | 11.1 | 77.8 | χ2 = 35.76 | 0.000 |

| Marital Status: % Married | 8.3 | 30.6 | χ2 = 6.31 | 0.012 |

| Group-level EAR Data | ||||

| Day of Week wearing EAR (% worn on weekday v. weekend) | 39.5 | 41.7 | χ2 = 1.62 | 0.444 |

| Total audio files | 755 | 701 | t = 0.22 | 0.824 |

| Files included in analyses | 573 (75.9%) | 563 (80.3%) | t = −1.07 | 0.298 |

| Files not analyzed | 182 | 138 | ||

| Subject sleeping | 140 (18.5%) | 102 (14.6%) | t = 0.83 | 0.408 |

| Subject not wearing EAR | 14 (1.9%) | 33 (4.7%) | t = −0.61 | 0.545 |

| Audio problems | 28 (3.7%) | 3 (0.4%) | t = 2.11 | 0.041 |

| Clinical Data of Schizophrenia Group (n = 38) | ||||

| M (SD) | ||||

| PANSS: Total Score (range: 29–203) | 61.76 (13.23) | |||

| PANSS: Positive Symptom Scale (range: 6–42) | 13.43 (4.49) | |||

| PANSS: Negative Symptom Scale (range: 8–56) | 15.65 (5.63) | |||

| PANSS: Cognitive Symptom Scale (range: 7–49) | 14.43 (4.48) | |||

| PANSS: Depressive Symptom Scale (range: 4–28) | 10.57 (3.78) | |||

| PANSS: Hostility Symptom Scale (range: 4–28) | 7.68 (2.94) | |||

Notes. n = number; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; EAR = Electronically Activated Recorder; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

Objective ratings of social behaviors were coded from audio recordings. Specifically, frequency of social interactions and quality of those interactions were coded using a standardized coding system, the Social Environment Coding of Sound Inventory (SECSI; Mehl, 2017; Mehl et al., 2012; Mehl et al., 2007). Social interactions were calculated as frequency of recordings where subjects speak with another person during the five-minute interval (0=no interaction; 1=interaction). As such, one interaction was the maximum coded for a single 5-minute EAR recording. Quality of interactions was determined based on the content of conversations. High-quality interactions involved participating in personal, substantive conversation (i.e., subject’s disclosure of thoughts/opinions or personal/emotional disclosures); Low-quality interactions involved no conversation, practical talk (i.e., “I will pick Sally up at 5:00 PM”), or small talk (i.e., “How’s the weather?”). Quality of interactions was a dichotomous variable (0=low-quality interaction; 1= high quality interaction). The entire recording received a “1” if participants achieved a high-quality interaction at any point during the 5-minute interval. Five trained raters completed the coding. Inter-rater reliability was initially established using a subset (10%) of randomly selected files; a high degree of reliability (ICC >0.9) was found for both codes.

2.2.2. Daily social journal

Social journals are paper assessments where subjects report on their activities throughout the day. Subjects recorded one journal entry each hour over the two days they wore the EAR. At each interval, subjects recorded what they were doing and rated their level of positive and negative emotions during the activity. Emotion ratings were made on seven-point Likert scale (0=No positive/negative feeling, 6=Extreme positive/negative feeling) with higher scores indicating higher levels of positive/negative emotions. Similar forms of EMA using diary methods have been successfully implemented for both clinical and healthy populations (e.g., Csikszentmihalyi and Larson, 1987; Myin-Germeys et al., 2003; Myin-Germeys, et al., 2001). To promote convenience and subject compliance, social journals were small, paper packets that could be folded and carried in a pocket or purse. Each entry was brief, taking approximately 1–2 minutes to complete. This social journal has been used to detect differences in emotion between people with schizotypy and healthy controls (Minor et al., 2018; Minor et al., 2020).

2.3. Procedure

This research was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Indiana University. Subjects were offered two-way transportation to the laboratory and underwent an informed consent process prior to study participation. In the lab, subjects completed semi-structured interviews to gather demographic and clinical information, including symptom severity (assessed via the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scales [PANSS; Kay et al., 1987]). Next, subjects were given EMA materials and training on how to use them. Specifically, subjects received a mobile device with the EAR application and were instructed to wear it in a protective carrying case attached to the outside of their clothing (e.g., belt, shirt pocket, pants pocket) over the next two days. Subjects were unaware of when recordings would occur but were told the device would record about five percent of the two-day period. Subjects were also provided a blank social journal packet, instructed to keep the packet with them, and complete one journal entry during each waking hour over the two-day period. Subjects were paid up to $50 for completing EMA procedures.

2.4. Analyses

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 24. Chi-square tests for independence and independent samples t-tests were used to compare groups on demographic and EAR data. We also calculated symptom severity in the schizophrenia group using a 5-factor structure of the PANSS: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, cognitive symptoms, depressive symptoms, and hostility symptoms (Bell et al., 1994).

Multilevel modeling was used to test hypotheses due to its ability to model nested data: assessment time points (Level 1) were nested within individuals (Level 2). First, two multilevel binary logistic regression models were conducted to assess whether group predicted EAR measures of social functioning. In these analyses, we included the random intercept and group status (schizophrenia/control) as the level-2 predictor, and outcome variables were EAR social interaction code (Model 1) and EAR quality of interaction code (Model 2). Next, two multi-level regression analyses were used to test if clinical status (schizophrenia/control) predicted reported emotion from the social journal. Again, we included the random intercept and group status as the level-2 predictor; outcome variables were social journal positive emotion (Model 1) and negative emotion (Model 2). Finally, two multilevel models were created to determine if the group effect on social journal positive emotion (Model 1) and negative emotion (Model 2) varied by context (social versus non-social) as determined by the EAR social interaction code. In each of these models, we included the random intercept, group status as a level-2 predictor, context as a level-1 predictor with random slope, as well as the interaction between level 1 and 2 predictors.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 outlines demographic and audio data between groups as well as clinical information of the schizophrenia group. Groups did not differ on age, sex, race, nor ethnicity. The control group was significantly more likely to be employed and married compared to the schizophrenia group. Overall, participants completed 98.08% of all social journal entries (schizophrenia group: 96.82%, control group: 99.43%). The only EAR data point that differed between groups was in the number of audio problems, such that the schizophrenia group experienced more audio problems than the control group. The schizophrenia group exhibited mild symptom severity on all PANSS scales. Secondary analyses were conducted exploring the effects of symptom severity on EAR and social journal measures in the schizophrenia group. Specifically, we examined how daily functioning measures of those considered in remission of illness (as defined by Andreasen et al., 2005) compared to those not in remission. We also tested associations between symptom domains and EMA measures. See Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for details of these analyses.

3.2. Group as a Predictor of Social and Emotional Functioning in Daily Life

Our hypotheses that group status (schizophrenia/control) would predict social functioning indices were partially supported. Group did not significantly predict EAR frequency of social interactions, OR=0.93, 95% CI=[0.55, 1.57], p=0.777, but did significantly predict EAR quality of interactions, OR=0.47, 95% confidence interval (CI)=[0.28, 0.77], p=0.003. Thus, for those in the schizophrenia group, the odds of engaging in a high-quality interaction at a given time point was 53% lower than for controls (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Social Behavior and Experienced Emotion in Schizophrenia and Control Groups

| Schizophrenia (n = 38) | Control (n = 36) | |

|---|---|---|

| Social Interaction: Frequency (SD) | 41.43% (27.22) | 42.63% (24.76) |

| High-quality Interaction: Frequency (SD) | 19.04% (19.06) | 31.74% (18.49) |

| Positive Emotion: Mean (SD) | 4.42 (1.43) | 4.87 (0.92) |

| Negative Emotion: Mean (SD) | 2.23 (1.22) | 1.63 (0.73) |

Notes. Frequency = Percent of audio records; SD = Standard deviation; Positive and negative emotion scores ranged from 1–7.

Results partially supported hypotheses that group status (schizophrenia/control) would predict reported emotions from the social journal. The effect of group status on social journal positive emotion only approached significance, B=−0.50, SE=0.27, p=0.074; however, group status did significantly predict social journal negative emotion, B=0.65, SE=0.24, p=0.008. The schizophrenia group reported more negative emotions than controls (see Table 2).

3.3. Moderation of Context on the Relationship between Group and Emotion

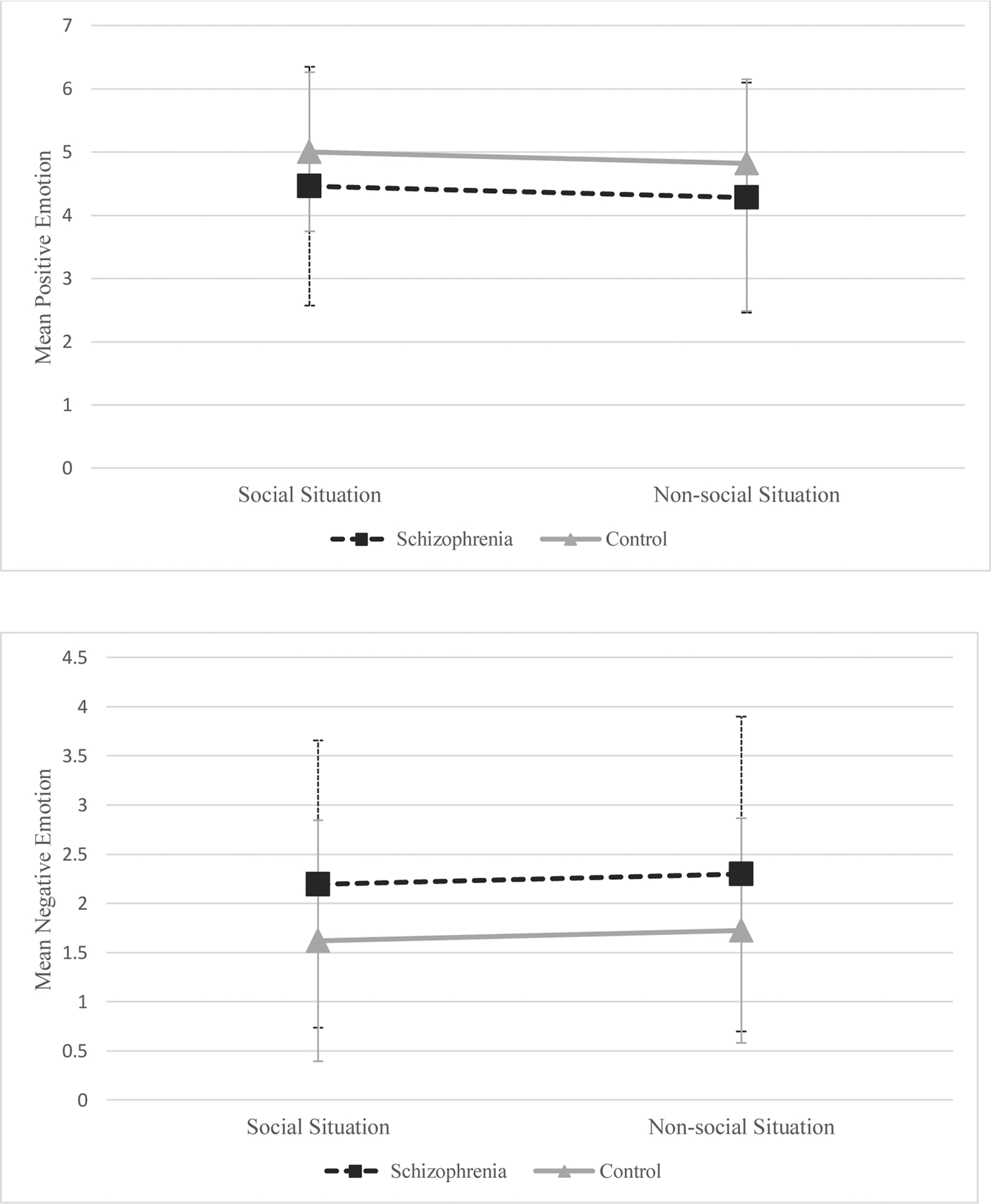

The group by context interaction was not significant for social journal positive emotion, B=−0.14, SE=0.17, p=0.390, nor negative emotion, B=−0.01, SE=0.15, p=0.973. As in previous models, the main effect of group was significant for social journal negative emotion, but not positive emotion. The main effect of context was not significant for either social journal negative emotion, B=0.003, SE=0.07, p=0.970, or positive emotion, B=0.02, SE=0.08, p=0.809. The hypotheses that group by context interactions would occur for positive and negative emotion were not supported (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mean Level of Emotion in Each Group Across Contexts.

Note. Schizophrenia group: n = 38; Control group: n = 36. Figure shows estimated marginal means for each emotion based on the multi-level models.

4. Discussion

This study sought to identify real-world social and emotional deficits in schizophrenia by implementing active and passive EMA. Three interesting findings emerged. First, although schizophrenia and control groups interacted with others at the same rate, those in the schizophrenia group exhibited significantly fewer high-quality interactions. This suggests social dysfunction in schizophrenia may not result from a lack of interaction, but rather deficits in deeper-level exchanges. Next, compared to controls, people with schizophrenia exhibited similar levels of positive emotion, but more negative emotion, in their daily lives. Lastly, context did not moderate the relationship between clinical status and reported emotion; levels of positive and negative emotion were similar in both groups across social and non-social contexts.

Contrary to hypotheses, clinical status (schizophrenia versus control) did not predict frequency of social interactions. Previous EMA studies suggest those with schizophrenia spend significantly more time alone (Oorschot et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2017). One explanation for the discrepancy in our findings could be the novel way in which we assessed frequency of social interactions. First, the EAR used a shorter sampling duration (i.e., two days) compared to most other studies who survey participants over 6–7 days (Mote et al., 2019). Second, whereas the EAR passively assessed social interactions, previous forms of EMA have used self-report and operationalized social interactions differently. For example, other studies asked participants to estimate how many times they communicated with someone since the last survey (Granholm et al., 2013), document whether they are “currently interacting” (Leendertse et al., 2018), or document if they are “currently alone” (Oorschot et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2017). In contrast, we used EAR audio recordings and operationalized social interactions as the presence of interactive speech with another person.

Both existing EMA and EAR approaches have strengths and weaknesses. Asking participants to estimate number of interactions since a previous survey has the benefit of assessing social behavior between EMA intervals; however, it is vulnerable to retrospective error and leaves room for interpretation. Participants may not recall every interaction nor consider brief exchanges as interactions. Moreover, when reporting on current social behavior, participants may not report interactions that occurred a few minutes prior to being asked (but within the 5-minute interval of an EAR recording). Finally, asking if a subject is currently alone measures whether subjects are around others, but not necessarily interacting. By providing a sample of audio data to be coded, the EAR objectively assesses frequency of social interactions as defined by conversations. However, it may miss social behavior in which there is no speaking or social behavior that occurred between recorded intervals. In this way, the discrepancy between our results and previous studies may be explained by differences in EMA methods.

In line with our expectations, clinical status predicted quality of interactions. Whereas control participants exhibited high-quality interactions in nearly a third of their files, those with schizophrenia demonstrated high-quality interactions in less than one-fifth of files. This suggests that, although those in the schizophrenia group interact as much as control participants, they spend less time engaging in substantive, more personal conversations (e.g., sharing thoughts, opinions, or emotional information). Because this is the first EMA study to examine such qualitative aspects of social interactions, these results are innovative and crucial for understanding social deficits in those with schizophrenia.

Deficits in high-quality interactions have important clinical implications for those with schizophrenia. It has been theorized that deeper conversations, rather than mere small talk, lead to stronger social connections and, therefore, greater well-being (Rabin, 2010). Furthermore, Fiorillo and Sabatini (2011) found that quality of social relationships predicted individuals’ health above and beyond quantity of interactions. When compared to healthy people, those with schizophrenia have fewer friends, narrower social networks, and diminished social support (Goldberg et al., 2003; Carpenter, 2019). Thus, the lack of high-quality interactions found in the schizophrenia group may suggest that diminished engagement in deeper-level conversations is driving these differences in quality and quantity of relationships. Although cognitive impairment and negative symptom severity have been theorized to drive social dysfunction in schizophrenia (Merlotti et al., 2018; Riehle et al., 2018), these symptom domains were not associated with daily social functioning in our sample (see Supplementary Table 2), suggesting deficient social engagement is pervasive in this disorder. People with schizophrenia desire social affiliation (Blanchard et al., 2015) and identify improving social functioning as a primary therapeutic goal (Shumway et al., 2003). Distinguishing between quantity and quality of social interactions in the treatment of schizophrenia could have important implications for social skills training programs. Results suggest that the development of treatment approaches that specifically foster deep social connections, rather than surface-level interactions, would be beneficial to increase social affiliation and quality of relationships.

Our hypothesis that group (schizophrenia/control) would predict reported emotion was only partly supported. Compared to controls, people with schizophrenia reported similar levels of positive emotion but more negative emotion. A meta-analysis of EMA studies suggests that, when reporting their day-to-day experiences, those with schizophrenia report more negative and less positive emotion than controls (Cho et al., 2017); thus, our results only partially align with this literature. Our method of measurement may, again, explain this discrepancy. The social journal uses a singular item to rate participants’ level of ‘positive feeling.’ Other EMA studies have calculated positive emotion by averaging ratings of various mood states (e.g., ‘cheerful,’ ‘relaxed,’ ‘satisfied;’ Oorschot et al., 2013). This more detailed assessment requires less participant interpretation and may more accurately capture emotional experiences. Alternatively, similar levels of positive emotion in our groups could be due to the generally mild symptom severity of our schizophrenia sample, as emotional dysfunction is associated with cognitive impairment and negative symptoms (Riehle et al., 2018; Strauss, 2013).

Contrary to our hypothesis, context did not moderate the relationship between clinical status and emotion. For positive emotion, these results are understandable as groups did not differ in this domain. Moreover, researchers have previously found that those with schizophrenia do not differ from controls in positive emotion during social experiences (Edwards et al., 2018; Kasanova et al., 2018). For negative emotion, group differences were found, but participants’ context when reporting emotion did not influence this difference. Although previous research has examined emotional experiences of people with schizophrenia during social activities, this was one of the first studies to examine the moderating effect of context on group differences in emotion. Yet, Oorschot et al. (2013) found people with schizophrenia and healthy controls similarly reported significantly less positive and more negative emotion when alone compared to with others. Our results do not align with this study, as social context did not influence emotion in either group. As mentioned above, our methods of measuring social versus non-social context and emotion differed from this study; these differences may explain some variability in our results. More research is needed to clarify if and how social interactions impact emotional experiences in those with and without schizophrenia.

Strengths of this project include the use of both active and passive EMA to provide a deeper understanding of social and emotional deficits in people with schizophrenia. However, this study also has limitations. First, our relatively small sample makes power to detect true relationships a concern. Moreover, our schizophrenia sample exhibited mild symptom severity and may not reflect social functioning of those with more severe symptomology. Thus, these results should be replicated in larger samples. Second, our use of passive EMA required us to simplify the definition of social functioning (i.e., frequency of interactions and high-quality conversations) since we could only code for concrete social behaviors captured via audio recording. There are latent factors (e.g., social cognition, social problem solving, subject’s performance appraisals) and behaviors that cannot be measured via audio (e.g., facial expression) to also consider in determining deficits in social functioning in schizophrenia. Participants may also act differently in social situations because they are wearing a recording device. Although such reactivity is concerning, previous studies suggests that participants habituate to the EAR within a few hours (Mehl and Holleran, 2007). We also alleviated this issue by 1) ensuring participants were unaware of when they were recorded; and 2) allowing participants to listen to and delete sensitive recordings before our team accesses them. Lastly, our measure of emotion using the social journal heavily relies on subject compliance; some may forget to complete journal entries in-the-moment, making this assessment not a true EMA. We tried to mitigate this concern by explaining the importance of in-the-moment ratings to participants, making the social journal packet small and convenient to carry, and making journal entries brief to not over-burden participants.

Results of this project yield important implications for future work. As mentioned, this is the first study to examine social functioning in schizophrenia using passive audio data. Additionally, we investigated differences in both quantity and quality of social interactions. Future studies are needed to further implement these methods. For example, Kasanova et al. (2018) examined emotional experiences during structured versus unstructured social activities. Results found that people with schizophrenia matched controls on frequency of unstructured social activities, but patients spent significantly less time in structured social activities. Moreover, patients reported the same emotional experiences in both social and non-social contexts. Our research design using the EAR could extend Kasanova et al.’s (2018) findings by determining how quality of interactions maps onto both structured and unstructured activity in the lives of those with schizophrenia. Quality of interactions, rather than frequency of social activities, may be more related to differences in emotional experiences.

Relatedly, the EAR may also be applied to research examining differences in who people interact with. Granholm et al. (2008) examined how much time people spend with familiar versus unfamiliar people and found the schizophrenia group spent more time with family or friends compared to coworkers and strangers. Participant’s appraisals of specific interaction partners (e.g., extent to which they like the other person) may also affect their willingness to engage in high-quality of interactions. Thus, future work may examine quality of interactions as a function who the person is interacting with and if that differently affects those with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls. Overall, incorporating the EAR into future studies will help us better understand the real-life social experiences of those with schizophrenia. Examining social functioning at this more granular level is a promising avenue for EMA research in schizophrenia.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Passive ecological momentary assessment offers unbiased social functioning measure

Content of conversation can be used as a proxy for quality of social interactions

People with schizophrenia may interact with others at the same rate as controls

People with schizophrenia engage in lower quality social interactions than controls

People with schizophrenia report more negative emotion compared to controls

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank our research team, especially Beshaun Davis, Matthew Marggraf, and Kathryn Hardin, for their hard work completing interviews and collecting the data for this project. We also thank the participants who volunteered for this research.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award (sub-award to K.S. Minor) [grant numbers KL2TR001106, UL1TR001108 PI: A. Shekhar]; and the American Psychological Foundation Pearson Early Career Grant (PI: K.S. Minor). This funding had no role in designing the study, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the completed manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest

None

References

- Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT Jr, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR, Weinberger DR 2005. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. The American journal of psychiatry, 162 (3), 441–449. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Yodkovik N, Sypher-Locke H, Hanewinkel M, 2008. Intrinsic motivation in schizophrenia: Relationships to cognitive function, depression, anxiety, and personality. J. Abnorm. Psychol 117 (4), 776. doi: 10.1037/a0013944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MD, Lysaker PH, Beam-Goulet JL, Milstein RM, & Lindenmayer JP (1994). Five-component model of schizophrenia: assessing the factorial invariance of the positive and negative syndrome scale. Psychiatry research, 52(3), 295–303. 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90075-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellack AS, Green MF, Cook JA, Fenton W, Harvey PD, Heaton RK, Laughren T, Leon AC, Mayo DJ, Patrick DL, Patterson TL, Rose A, Stover E, Wykes T, 2007. Assessment of community functioning in people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses: A white paper based on an NIMH-sponsored workshop. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 33(3), 805–822. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Park SG, Catalano LT, Bennett ME, 2015. Social affiliation and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Examining the role of behavior skills and subjective responding. Schizophrenia Research, 168, 491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LH, Silvia PJ, Myin-Germeys I, Kwapil TR, 2007. When the need to belong goes wrong: The expression of social anhedonia and social anxiety in daily life. Association for Psychological Science, 18(9), 778–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01978.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Patrick D, 2007. Social functioning as an outcome measure in schizophrenia studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 116, 403–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WT, 2019. Social withdrawal as psychopathology of mental disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 97, 85–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Gonzalez R, Lavaysse LM, Pence S, Fulford D, Gard. DE, 2017. Do people with schizophrenia experience more negative emotion and less positive emotion in their daily lives? A meta-analysis of experience sampling studies. Schizophrenia Research, 183, 49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Callaway DA, Najolia GM, Larsen JT, Strauss GP, 2012. On “risk” and reward: Investigating state anhedonia in psychometrically defined schizotypy and schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol 121 (2), 407. doi: 10.1037/a0026155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AA, Minor KS, 2010. Emotional experience in patients with schizophrenia revisited: Meta-analysis of laboratory studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36, 1, 143–150. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M, Larson R, 1987. Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 175, 9, 526–536. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198709000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depp CA, Moore RC, Perivoliotis D, Holden JL, Swendsen J, Granholm EL, 2016. Social behavior, interaction appraisals, and suicidal ideation in schizophrenia: The dangers of being alone. Schizophrenia Research, 172 (1–3), 195–200. Doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CJ, Cella M, Emsley R, Tarrier N, Wykes THM, 2018. Exploring the relationship between the anticipation and experience of pleasure in people with schizophrenia: An experience sampling study. Schizophrenia Research, 202, 72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.06.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueira ML, Brissos S, 2011. Measuring psychosocial outcomes in schizophrenia patients. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 24, 91–99. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283438119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo D, Sabatini F, 2011. Quality and quantity: The role of social interactions in self reported individual health. Social Science & Medicine, 73, 11, 1644–1652. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg R, Rollins A, Lehman A, 2003. Social network correlates among people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Rehabil J 26,4, 393–404. doi: 10.2975/26.2003.393.402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, Ben-Zeev, Fulford D, Joel S, 2013. Ecological momentary assessment of social functioning in schizophrenia: Impact of performance appraisals and affect on social interactions. Schizophrenia Research, 145, 120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, Loh C, Swendsen J, 2008. Feasibility and validity of computerized ecological momentary assessment in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull 34(3), 507–514. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove TB, Tso IF, Chun J, Mueller SA, Taylor SF, Ellingrod VL, McInnis MG, Deldin PJ, 2016. Negative affect predicts social functioning across schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Findings from an integrated data analysis. Psychiatry Research, 243, 198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hektner JM, Schmidt JA, Csikszentmihalyi M, 2007. Experience sampling method: Measuring the quality of everyday life. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Blanchard JJ, Clark LA, Green MF, 2008. Affective traits in schizophrenia and schizotypy. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(5), 856–874. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasanova Z, Oorschot M, Myin-Germeys I, 2018. Social anhedonia and asociality in psychosis revisited. An experience sampling study. Psychiatry Research, 270, 375–381. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.09.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA, 1987. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 13(2), 261–276. 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwapil TR, Silvia PJ, Myin-Germeys I, Anderson A, Coates SA, Brown LH, 2009. The social world of the socially anhedonic: Exploring the daily ecology of asociality. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 103–106. 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.10.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leendertse P, Myin-Germeys I, Lataster T, Simons CJP, Oorschot M, Lardinois M, Schneider M, van Os J, Reininghaus U, For Genetic Risk and Outcome of Psychosis investigators, 2018. Subjective quality of life in psychosis: evidence for an association with real world functioning? Psychiatry Research, 26, 116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR, 2007. Eavesdropping on health: a naturalistic observation approach for social health research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1, 359–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00034.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR, 2017. The electronically activated recorder or EAR: a method for the naturalistic observation of daily social behavior. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26, 184–190. doi: 10.1177/0963721416680611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR, Holleran SE, 2007. An empirical analysis of the obtrusiveness of and participants’ compliance with the electronically activated recorder (EAR). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 23, 248–257. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.23.4.248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR, Pennebaker JW, Crow DM, Dabbs J, Price JH, 2001. The electronically activated recorder (EAR): a device for sampling naturalistic daily activities and conversations. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 33, 517–523. 10.3758/BF03195410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR, & Robbins ML, 2012. Naturalistic observation sampling: The Electronically Activated Recorder (EAR). In Mehl MR, & Conner TS (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (pp. 176–192). New York, NY: Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR, Robbins ML, Deters FG, 2012. Naturalistic observation of health-relevant social processes: the electronically activated recorder methodology in psychosomatics. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74, 410–417. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182545470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR, Vazire S, Holleran SE, Clark S, 2010. Eavesdropping on happiness: Well being is related to having less small talk and more substantive conversation. Psychol Sci, 21, 4, 539–541. doi: 10.1177/0956797610362675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR, Vazire S, Ramirez-Esparza N, Slatcher RB, Pennebaker JW, 2007. Are women really more talkative than men? Science, 317, 82. doi: 10.1126/science.1139940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlotti E, Mucci A, Caputo F, Galderisi S, 2018. Cognitive deficits in psychotic disorders and their impact on social functioning. Journal of Psychopathology, 24(2), 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Minor KS, Davis BJ, Marggraf MP, Luther L, Robbins ML, 2018. Words matter: Implementing the electronically activated recorder in schizotypy. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 9, 2, 133–143. 10.1037/per0000266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor KS, Hardin KL, Beaudette DM, Waters LC, White AL, Gonzenbach V, Robbins ML, 2020. Social functioning in schizotypy: How affect influences social behavior in daily life. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76, 12, 2212–2221. 10.1002/jclp.23010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mote J, Fulford D, 2020. Ecological momentary assessment of everyday social experiences of people with schizophrenia: A systematic review. Schizophrenia Research, 216, 56–68. 10.1016/j.schres.2019.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, van Os J, 2003. The experience sampling method in psychosis research. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 15, S33–S38. 10.1097/00001504-200304002-00006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, van Os J, Schwartz JE, Stone AA, Delespaul PA, 2001. Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 58, 1137–1144. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisenson LG, Berenbaum HG, Good TL (2001). The development of interpersonal relationships in individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatry, 62(3), 111–125. http://dx.doi.org.proxy.ulib.uits.iu.edu/10.1521/psyc.64.2.111.18618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oorschot M, Lataster T, Thewissen V, Lardinois M, van Os J, Delespaul PA, E. G, Myin-Germeys I, 2012. Symptomatic remission in psychosis and real-life functioning. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 201(3), 215–220. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.104414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oorschot M, Lataster T, Thewissen V, Lardinois M, Wichers M, van Os J, Delespaul P, Myin-Germeys I, 2013. Emotional experience in negative symptoms of schizophrenia—No evidence for a generalized hedonic deficit. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(1), 217–225. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Mehl MR, Niederhoffer KG, 2003. Psychological aspects of natural language use: Our words, our selves. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 547–577. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin RC, 2010. Talk deeply, be happy? The New York Times. https://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/03/17/talk-deeply-be-happy/ (accessed 10 October 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Riehle M, Mehl S, Lincoln TM, 2018. The specific social costs of expressive negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Reduced smiling predicts interactional outcome. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138(2), 133–144. http://dx.doi.org.proxy.ulib.uits.iu.edu/10.1111/acps.12892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro E, Clark LA, 2009. Psychosocial functioning in the context of diagnosis: Assessment and theoretical issues. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 313–324. 10.1037/a0016611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins ML, Focella ES, Kasle S, López AM, Weihs KL, Mehl MR, 2011. Naturalistically observed swearing, emotional support, and depressive symptoms in women coping with illness. Health Psychology, 30, 789–792. 10.1037/a0023431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins ML, López AM, Weihs KL, Mehl MR, 2014. Cancer conversations in context: Naturalistic observation of couples coping with breast cancer. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 380–390. 10.1037/a0036458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins ML, Mehl MR, Holleran SE, Kasle S, 2011. Naturalistically observed sighing and depression in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a preliminary study. Health Psychology, 30, 129–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M, Reininghaus U, van Nierop M, Janssens M, Myin-Germeys I, GROUP Investigators, 2017. Does the Social Functioning Scale reflect real-life social functioning? An experience sampling study in patients with a non-affective psychotic disorder and healthy control individuals. Psychological Medicine, 47, 2777–2786. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC, 1998. The Mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumway M, Saunders T, Shern D, Pines E, Downs A, Burbine T, Beller J, 2003. Preferences for schizophrenia treatment outcomes among public policy makers, consumers, families, and providers. Psychiatric Services, 54(8), 1124–1128. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, 2013. The emotion paradox of anhedonia in schizophrenia: Or is it? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(2), 247–250. 10.1093/schbul/sbs192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Gold JM, 2012. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(4) 364–373. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Llerena K, Gold JM, 2011. Attentional disengagement from emotional stimuli in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 131(1), 219–223. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Kappenman ES, Culbreth AJ, Catalano LT, Lee BG, Gold JM, 2013. Emotion regulation abnormalities in schizophrenia: cognitive change strategies fail to decrease the neural response to unpleasant stimuli. Schizophr. Bull 39(4), 872–883. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Mclntyre CW, Hamaker S, 1992. Affect, personality, and social activity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 63, 1011–1025. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.