Abstract

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways are intracellular signaling pathways necessary for regulating various physiological processes, including neurodevelopment. The developing brain is vulnerable to toxic substances, and metals, such as lead, mercury, nickel, manganese, and others, have been proven to induce disturbances in the MAPK signaling pathway. Since a well-regulated MAPK is necessary for normal neurodevelopment, perturbation of the MAPK pathway results in neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD). ASD affects brain parts responsible for communication, cognition, social interaction, and other patterned behaviors. Several studies have addressed the role of metals in the etiopathogenesis of ASD. Here, we briefly review the MAPK signaling pathway and its role in neurodevelopment. Furthermore, we highlight the role of metal toxicity in the development of ASD and how perturbed MAPK signaling may result in ASD.

Keywords: MAPK, Neurodevelopment disorder, Autism, Metal exposure

Introduction

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways are prominent families of intracellular signaling pathways controlling various intracellular functions and development during cell proliferation. They are serine-threonine kinases that regulate various cellular activities [1,2]. Deviation from the regular control of the MAPK signaling pathway has been associated with the development of several human diseases, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and various forms of cancer [1,3] (Figure 1). Neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) reflect various conditions resulting from deviation from optimal brain development, commonly due to a fetus’s exposure to toxic substances or genetic disorders [4]. ASD is an NDD with an early-appearing social communication disorder that affects brain parts responsible for communication, social interaction, cognition, and other patterned behaviors [4,5]. Juvenile health has been dramatically influenced by the environment, as several NDDs have been attributed to exposure of developing fetus to various toxic substances in the external environment. Such neurotoxic substances are predominantly, but not limited to, industrial chemicals. Metals as one of the major environmental toxicants have been linked to aberrant neurodevelopment and may represent a significant cause of NDD. Reports have shown a close relationship between levels of environmental toxicants and increased frequency of ASD [4,6,7]. Here, we review the role of the MAPK signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of ASD and the neurotoxic impact of metal exposures.

Figure 1.

MAPK in normal and perturbed neurodevelopment. Optimum developmental conditions will favor a well-regulated MAPK signaling, therefore normal intracellular functions and development, and consequently normal neurodevelopment. Exposure of the developing brain to neurotoxic substances results in perturbed MAPK signaling, resulting in NDDs such as ASD. ASD is characterized by a defect in social communication and restricted, repetitive sensory-motor behavior.

Overview of MAPK signaling

Four distinct cascades share the MAPK signaling pathway. These cascades, named according to their MAPK class components, include the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2), Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNK1/2/3), p38-MAPK, and ERK5 [8]. Different extracellular and intracellular stimuli activate these pathways. Such triggers include cytokines, hormones, peptide growth factors, and several cellular stressors, such as oxidative stress. The MAPK signaling pathway regulates several activities, including cellular proliferation, differentiation, migration, survival, aging, and death [1,8]. In the nervous system, MAPK plays a variety of roles. MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) mediate antiapoptotic actions of vasopressin in hippocampal neurons. Likewise, plasmalogenmediated cell survival is dependent on the activation of MAPK/ERK pathways [8]. The phosphor-inositode-3 kinase (PI3K) and MAPK play crucial roles in brain angiogenesis. Activated by the insulin signaling pathway, PI3K and MAPK are involved in stimulating the hypoxia-inducible angiogenesis factor [9]. MAPK is also involved in the regulation of myelination and remyelination in the central nervous system by interacting with other intracellular pathways [10]. MAPK signaling is also essential in regulating renal differentiation, cardiovascular and digestive system development, immune responsiveness, and many other systems [8,11]. Deviation from the typical regulation of the MAPK signaling pathway is associated with numerous human diseases’ etiology. ERK signaling is involved in several steps of cancer development. It is a decisive pathway for the survival of human cancer cells, metastasis, and resistance to treatments. In contrast, the JNK pathway is involved in neuronal apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [1,12] (Figure 2). In a study conducted by Rosina et al. to identify differential expression of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) and MAPK pathways in patients affected by moderate and severe idiopathic autism, it was discovered that there was an increase in the activity of mTOR and MAPK pathways in these patients by analyzing the peripheral blood at the protein level, which showed the impact of perturbed MAPK signaling in the etiology of ASD [13].

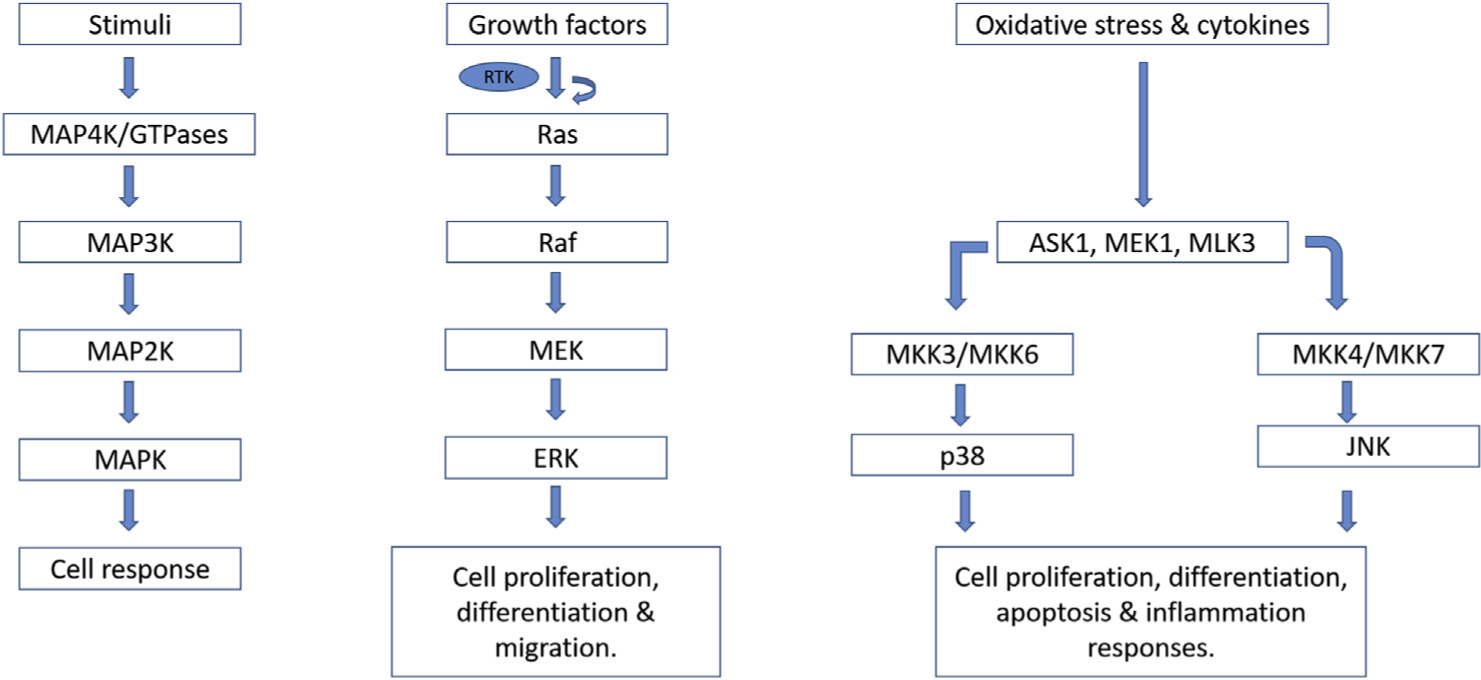

Figure 2.

MAPK signaling pathway. In the MAPK signaling pathway, external stimuli initiate MAP4K/GTPases’ activation, which in turn phosphorylates and activates MAP3K. Activated MAP3K phosphorylates and activates MAP2K, which in turn phosphorylates and activates MAPK. Activated MAPK phosphorylates various other proteins in the cell, which consequently results in cellular responses. Other members of the MAPK family signaling pathway include ERK, p38, and JNK.

MAPK pathway neurodevelopmental perturbations

The MAPK signaling axis comprises a minimum of three components: MAP3K, MAP2K, and MAPK. The MAP2Ks are phosphorylated and activated by MAP3Ks. Activated MAP2Ks, in turn, phosphorylate and trigger MAPKs, which phosphorylate several other proteins, including transcription factors such as Elk-1, c-jun, ATF2, and p53 [1]. MAPK cascades are primarily activated by extracellular growth factors that activate receptors on the cell surface. These surface receptors are receptor tyrosine kinase, and G protein–coupled receptors. Many subfamilies of receptor tyrosine kinase can initiate the MAPK cascades. MAPK activation mediated by G protein–coupled receptor results in the activation of phospholipase C, which, in turn, increases intracellular calcium that activates protein kinase C leading to Raf activation of Raf and the MAPK pathways [2]. In response to cellular stresses such as oxidative, osmotic, hypoxic, and genotoxic stress or proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β, the JNK and p38 pathways are activated. In the ERK signaling pathway, Raf isoforms such as A-Raf, B-Raf, or Raf-1 activates MEK1/2, which, in turn, activates ERK1 or ERK2 (ERK1/2) [1,14,15].

MAPK signaling has been linked to both developmental and maturation processes in the central nervous system. During neurodevelopment, the optimal quantity of progenitor cells needs to be generated and is associated with the formation of necessary neuronal circuits and synapses required for normal brain functions. Perturbations in any of these processes alter normal brain development and consequently result in NDD [2]. Fibroblast growth factor and neurotrophin signaling are the drivers of MAPK signaling during neurodevelopment. During the cerebral cortex development, the ERK plays a crucial role in driving the neural stem cell population [16–18].

Moreover, ERK signaling plays a crucial role in developing the brain’s supporting cells, such as oligodendrocytes and glial cells. Although ERK loss of ERK2 does not affect oligodendrocytes’ proliferation, the decreased expression of ERK/MAPK may result in delayed maturation of oligodendrocytes [2,19]. In ASD, ERK/MAPK pathways are a central hub that interacts with genes and copy number variants. Various genes and copy number variants have been identified and shown to be associated with ASD. Both syndromic and nonsyndromic forms of ASD have been linked to perturbed ERK/MAPK signaling pathway. In ASD, disorders associated with dysregulated ERK/MAPK pathways are collectively identified as ‘RASopathies,’ reflecting a mutation in the genes that encode the signaling pathway elements, which activate the ERKs [2].

Metal neurotoxicity and ASD

Exposure to heavy metals may result in aberrant effects on the nervous system, especially the developing brain, susceptible to environmental factors. Metals may disrupt the strictly regulated brain development process, resulting in neurodevelopment disorders, such as ASD (Figure 3). These metals, including lead, mercury, nickel, and manganese, have been shown to play critical roles in the pathogenesis of ASD during neurodevelopment [4]. Exposure to these metals during the early stages of fetal development may result in brain disorder at concentrations much lower than those affecting adults’ brain function [20]. The blood level of these metals is higher in children with ASD. A study by Li et al. supports the vital role of heavy metal exposure in the etiology of ASD [21].

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of metal-induced perturbed MAPK in ASD. Overexposure to metals (Pb, Hg, Mn, Ni) during neurodevelopment triggers perturbations in MAPK signaling and may contribute to ASD onset. Pb causes increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 of the MAPK family. Hg activates MAPK and PKA/CREB pathway, followed by upregulation of c-fos and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Mn induces oxidative stress, increased p38, ERK1/2, JNK1/2/3, and caspase activities, and Ni is also a contributor to imbalanced antioxidants in oxidative stress.

Lead (Pb)

Lead, soft bluish-white metal with no known functional role in the body, is historically used in alloys, construction materials, paints, pigments, and other metals’ coating elements. With technological advancement, its utilization in electricity, communication, and as an antiknock agent in planes increased [4,22]. The consumption of lead-contaminated water during pregnancy and lactation has been linked with NDD. The most common means of lead toxicity among children is the ingestion of paint chips or dust containing lead [22]. Severe lead blood level initiates neuronal damage in ASD pathogenesis [23]. El-Ansary et al. [24] reported a significant rise of mercury and lead with a concomitant decrease in selenium levels in RBCs of children with ASD compared to healthy control potential lead-induced neurotoxicity in ASD. Exposure of the fetus to lead during pregnancy, even at a low dose, may result in brain damage leading to adverse neurobehavioural development in the offsprings mediated via epigenetic changes [22].

Mercury (Hg)

Mercury, a ubiquitous naturally occurring element, has a wide range of uses in industry and manufacturing processes [25]. Mercury intoxication has been linked to brain damage in developing fetuses. ASD children have a higher susceptibility to heavy metal intoxication than non-ASD children. The role of Hg in the pathogenesis of ASD includes, but not limited to, degeneration of microtubule, inflammation of the neurons, lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, dysfunctions in the cellular mitochondrion, inhibition of glutamic acid decarboxylase activity, decrease in the level of reduced glutathione, increase in the level of oxidized glutathione, perturbed calcium homeostasis and signaling, and increase in the level of proinflammatory cytokines in the brain [26]. Levels of mercury in urine, blood, and hair were positively associated with ASD [27]. Also, mercury toxicity can initiate immunologic changes such as specific brain antibodies’ production [26]. A reduced mercury level and brain antibodies were recommended as a therapeutic approach to treat ASD [28]. However, the pathophysiological etiologies associated with the development of ASD remain controversial. Gil-Hernandez et al. [29] reported no relationship between mercury neurotoxicity and the etiology of ASD based on no difference in urinary mercury levels between ASD and non-ASD children. This observation was also confirmed by Wright et al. [30]. However, a comprehensive report on the relationship between mercury and autism shows that the vast majority (74%) of such studies indicates both direct and indirect association between mercury and ASD onset [31].

Nickel (Ni)

Nickel is a transition element with a significant contribution to plants’ morphological and physiological functions, eukaryotes, algae, and bacteria [32]. However, at high amounts, nickel alters various metabolic processes in plants, inhibiting enzymatic activities, and the process of photosynthesis. Humans’ exposure to nickel-polluted environments may result in multiple pathological effects, including lung fibrosis, cancer, cardiovascular, and renal diseases [33]. The neurotoxic effects of nickel are associated with its propensity to cause oxidative stress [4,34]. Nickel decreases the activity of superoxide dismutase and catalase, thereby increasing reactive oxygen species [35]. Nickel has also been linked to epigenetic effects by causing DNA methylation, histone modification, and microRNA expression, resulting in altered gene expression [33]. Ijomone et al. [34] concluded that nickel induces developmental neurotoxicity by causing degeneration of cholinergic, dopaminergic, and GABAergic neurons. Perturbation in these neurotransmitter systems has been linked to ASD [4].

Manganese (Mn)

Manganese is an essential trace element necessary for several physiological processes. However, manganese accumulation or impaired hepatobiliary excretion can result in neurotoxic effects and NDD [36]. Several studies supported the association between ASD and Mn exposure as measured by air distribution, hair, urine, and Mn’s blood levels, although with some conflicting findings [37–39]. Manganese overexposure results in oxidative stress causing an imbalance between reactive oxygen species and antioxidants. In addition, ASD has been linked to a perturbation of the dopaminergic system [40]. Interestingly, Mn overexposure is established to trigger dopaminergic dysfunctions; hence it is considered an environmental risk factor for ASD [4,41].

MAPK signaling and metal neurotoxicity in ASD pathogenesis

MAPK signaling pathways are altered during neurodevelopment because of the fetus’s overexposure to several metals, which have neurotoxic effects on the developing brain (Figure 3). There are several mechanisms by which metal neurotoxicity causes perturbed MAPK signaling in ASD. According to Leal et al., lead modulates the ERK1/2 and p38 of MAPK signaling in the cerebellum of Brazilian catfish Rhamdia quelen, showing this metal’s potential role in perturbed MAPK signaling [42]. The study also reported that both in vivo and in vitro lead exposure resulted in significantly increased phosphorylation of both MAPKs [42]. Fujimural and Usuki suggested that methylmercury (MeMercury) induces neuronal degeneration by causing hyperactivity of site-specific neurons induced by the activation of MAPK and PKA/CREB pathways followed by upregulation of c-fos and brain-derived neurotrophic factor [43]. Cordova et al. showed that overexposure of fetus to Mn during critical neurodevelopment stages results in dysfunction in motor coordination with a parallel rise in oxidative stress markers, increased phosphorylation of p38 (MAPK), and activity of caspase in the striatum [44]. In a study conducted by Peres et al. in immature rats, Mn led to the activation of MAPK signaling (ERK1/2 and JNK1/2/3) in slices of immature hippocampus and striatum, suggesting a potential role of Mn in perturbed MAPK signaling in the juvenile or developing brain [45]. Some studies also suggest metal-induced neuroinflammation as a mechanism for perturbed MAPK in ASD [4,46]. Zhu et al. highlighted the roles of PKA and Ca2+-dependent p38 activation in protecting against manganese neuronal apoptosis [47]. The study emphasized that p38 MAPK/CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) activation through PKA activation and increased cellular Ca2+ aided in mitigating Mn-induced neuronal apoptosis regulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor, thereby elucidating the process of Mn-induced neurotoxicity and the impact of the MAPK signaling pathway [47].

Conclusion

MAPK signaling plays a crucial role in neurodevelopment. As discussed in this article, the developing fetus is vulnerable to overexposure to certain substances such as metals. Overexposure to these metals results in a perturbed MAPK signaling pathway, consequently altering neurodevelopment’s standard process, thereby resulting in neurodevelopment disorders such as ASD. These metals use several mechanisms to cause disturbances in the normal process of neurodevelopment. Some cause an imbalance between antioxidants and free radicals, resulting in oxidative stress, while some have epigenetic effects, leading to alterations in the genes coding for the MAPK signaling pathway. Several studies found a potential relationship between metal overexposure and ASD, explaining the potential role of these metals in the pathogenesis of ASD. However, the relationship between these metals and ASD and metal exposure remains controversial and requires future studies. Further research is needed to provide additional evidence on the relationship between metal exposure and ASD and elucidate the role of metal-induced perturbed MAPK in the etiopathogenesis of ASD.

Acknowledgements

O.M.I. acknowledges the International Brain Research Grants (IBRO) to The Neuro-Lab, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria. M.A. is supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH), USA grants: NIEHS R01 10563 and NIEHS R01 07331.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

References

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

* * of outstanding interest

- 1.Kim EK, Choi EJ: Pathological roles of MAPK signaling pathways in human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1802: 396–405.20079433 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vithayathil J, Pucilowska J, Landreth GE: ERK/MAPK signaling and autism spectrum disorders. Prog Brain Res 2018, 241: 63–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pucilowska J, Vithayathil J, Tavares EJ, Kelly C, Karlo JC, Landreth GE: The 16p11.2 deletion mouse model of autism exhibits altered cortical progenitor proliferation and brain cytoarchitecture linked to the ERK MAPK pathway. J Neurosci 2015, 35:3190–3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ijomone OM, Olung NF, Akingbade GT, Okoh COA, Aschner M: Environmental influence on neurodevelopmental disorders: potential association of heavy metal exposure and autism. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2020, 62:126638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lord C, Elsabbagh M, Baird G, Veenstra-Vanderweele J: Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 2018, 392:508–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickerson AS, Rahbar MH, Han I, Bakian AV, Bilder DA, Harrington RA, et al. : Autism spectrum disorder prevalence and proximity to industrial facilities releasing arsenic, lead or mercury. Sci Total Environ 2015, 536:245–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts AL, Lyall K, Hart JE, Laden F, Just AC, Bobb JF, et al. : Perinatal air pollutant exposures and autism spectrum disorder in the children of Nurses‘ Health Study II participants. Environ Health Perspect 2013, 121:978–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y, Liu WZ, Liu T, Feng X, Yang N, Zhou HF: Signaling pathway of MAPK/ERK in cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, senescence and apoptosis. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 2015, 35(6):600–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng Y, Zhang L, Hu Z: Cerebral insulin, insulin signaling pathway, and brain angiogenesis. Neurol Sci 2016, 37:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaesser JM, Fyffe-Maricich SL: Intracellular signaling pathway regulation of myelination and remyelination in the CNS. Exp Neurol 2016, 283(Pt B):501–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurtzeborn K, Kwon HN, Kuure S: MAPK/ERK signaling in regulation of renal differentiation. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burotto M, Chiou VL, Lee JM, Kohn EC: The MAPK pathway across different malignancies: a new perspective. Cancer 2014, 120:3446–3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosina E, Battan B, Siracusano M, Di Criscio L, Hollis F, Pacini L, et al. : Disruption of mTOR and MAPK pathways correlates with severity in idiopathic autism. Transl Psychiatry 2019, 9:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis RJ: Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell 2000, 103:239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W: MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26:3279–3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bottcher RT, Niehrs C: Fibroblast growth factor signaling during early vertebrate development. Endocr Rev 2005, 26: 63–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutin G, Fernandes M, Palazzolo L, Paek H, Yu K, Ornitz DM, et al. : FGF signalling generates ventral telencephalic cells independently of SHH. Development 2006, 133:2937–2946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pucilowska J, Puzerey PA, Karlo JC, Galan RF, Landreth GE: Disrupted ERK signaling during cortical development leads to abnormal progenitor proliferation, neuronal and network excitability and behavior, modeling human neuro-cardio-facial-cutaneous and related syndromes. J Neurosci 2012, 32: 8663–8677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fyffe-Maricich SL, Karlo JC, Landreth GE, Miller RH: The ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates the timing of oligodendrocyte differentiation. J Neurosci 2011, 31:843–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grandjean P, Landrigan PJ: Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals. Lancet 2006, 368:2167–2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.*.Li H, Li H, Li Y, Liu Y, Zhao Z: Blood mercury, arsenic, cadmium, and lead in children with autism spectrum disorder. Biol Trace Elem Res 2018, 181:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Heavy metals exposure particularly during early-life have been thought to be risk factors for ASD. The authors provide data supporting the roles of heavy metals exposure in children, especially mercury, in the etiology of ASD.

- 22.Khalid M, Abdollahi M: Epigenetic modifications associated with pathophysiological effects of lead exposure. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev 2019, 37: 235–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang M, Hossain F, Sulaiman R, Ren X: Exposure to inorganic arsenic and lead and autism spectrum disorder in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chem Res Toxicol 2019, 32:1904–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Ansary A, Bjørklund G, Tinkov AA, Skalny AV, Al Dera H: Relationship between selenium, lead, and mercury in red blood cells of Saudi autistic children. Metab Brain Dis 2017, 32:1073–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidson PW, Myers GJ, Weiss B: Mercury exposure and child development outcomes. Pediatrics 2004, 113(4 Suppl): 1023–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kern JK, Geier DA, Audhya T, King PG, Sykes LK, Geier MR: Evidence of parallels between mercury intoxication and the brain pathology in autism. Acta Neurobiol Exp 2012, 72: 113–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sulaiman R, Wang M, Ren X: Exposure to aluminum, cadmium, and mercury and autism spectrum disorder in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chem Res Toxicol 2020, 33:2699–2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kern JK, Geier DA, Mehta JA, Homme KG, Geier MR: Mercury as a hapten: a review of the role of toxicant-induced brain autoantibodies in autism and possible treatment considerations. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2020, 62:126504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.*.Gil-Hernández F, Gómez-Fernández AR, la Torre-Aguilar MJ, Pérez-Navero JL, Flores-Rojas K, Martín-Borreguero P, et al. : Neurotoxicity by mercury is not associated with autism spectrum disorders in Spanish children. Ital J Pediatr 2020, 46:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The role of heavy metals in etiology of ASD is still being debated. Here the authors show no evidence to support the relationship between mercury neurotoxicity and ASD in Spain.

- 30.Wright B, Pearce H, Allgar V, Miles J, Whitton C, Leon I, et al. : A comparison of urinary mercury between children with autism spectrum disorders and control children. PloS One 2012, 7, e29547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kern JK, Geier DA, Sykes LK, Haley BE, Geier MR: The relationship between mercury and autism: a comprehensive review and discussion. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2016, 37:8–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zambelli B, Uversky VN, Ciurli S: Nickel impact on human health: an intrinsic disorder perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1864:1714–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Genchi G, Carocci A, Lauria G, Sinicropi MS, Catalano A: Nickel: human health and environmental toxicology. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.*.Ijomone OM, Miah MR, Akingbade GT, Bucinca H, Aschner M: Nickel-induced developmental neurotoxicity in C. elegans includes cholinergic, dopaminergic and GABAergic degeneration, altered behaviour, and increased SKN-1 activity. Neurotox Res 2020, 37:1018–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Here, the authors used the innovative nematode, C. elegans, model to investigate suceptibility of nervous system to Ni toxicity following early life exposures. Authors show that exposure at early life to the metal, Ni, causes neuronal damage across several neurotransmitter systems and alters behavior at the late stage of life.

- 35.Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D, Rose-John S: The pro-and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1813:878–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuschl K, Mills PB, Clayton PT: Manganese and the brain. Int Rev Neurobiol 2013, 110:277–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucchini R, Placidi D, Cagna G, Fedrighi C, Oppini M, Peli M, et al. : Manganese and developmental neurotoxicity. Adv Neurobiol 2017, 18:13–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahbar MH, Samms-Vaughan M, Dickerson AS, Loveland KA, Ardjomand-Hessabi M, Bressler J, et al. : Blood manganese concentrations in Jamaican children with and without autism spectrum disorders. Environ Health 2014, 13:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdullah MM, Ly AR, Goldberg WA, Clarke-Stewart KA, Dudgeon JV, Mull CG, et al. : Heavy metal in children‘s tooth enamel: related to autism and disruptive behaviors? J Autism Dev Disord 2012, 42:929–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavăl D: A dopamine hypothesis of autism spectrum disorder. Dev Neurosci 2017, 39:355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miah MR, Ijomone OM, Okoh CO, Ijomone OK, Akingbade GT, Ke T, et al. : The effects of manganese overexposure on brain health. Neurochem Int 2020, 135:104688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leal RB, Ribeiro SJ, Posser T, Cordova FM, Rigon AP, Zaniboni Filho E, et al. : Modulation of ERK1/2 and p38(MAPK) by lead in the cerebellum of Brazilian catfish Rhamdia quelen. Aquat Toxicol 2006, 77:98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.**.Fujimura M, Usuki F: Site-specific neural hyperactivity via the activation of MAPK and PKA/CREB pathways triggers neuronal degeneration in methylmercury-intoxicated mice. Toxicol Lett 2017, 271:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The MAPK signalling could be crucial to developmental neurotoxicity of metals. The authors demonstrated that methylmecury triggered MAPK and PKA/CREB pathways followed by c-fos and BDNF upregulation, which induced site-specific neural hyperactivity and consequently neuronal degeneration.

- 44.Cordova FM, Aguiar AS Jr, Peres TV, Lopes MW, Gonçalves FM, Pedro DZ, et al. : Manganese-exposed developing rats display motor deficits and striatal oxidative stress that are reversed by Trolox. Arch Toxicol 2013, 87:1231–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peres TV, Pedro DZ, de Cordova FM, Lopes MW, Gonçalves FM, Mendes-de-Aguiar CB, et al. : In vitro manganese exposure disrupts MAPK signaling pathways in striatal and hippocampal slices from immature rats. BioMed Res Int 2013, 2013: 769295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.*.Qasem H, Al-Ayadhi L, Bjørklund G, Chirumbolo S, El-Ansary A: Impaired lipid metabolism markers to assess the risk of neuroinflammation in autism spectrum disorder. Metab Brain Dis 2018, 33:1141–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The association between ASD and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and other inflammatory markers was investigated. A higher level of most of these biomarkers in ASD confirms the role of neuroinflammation in the etiology of ASD.

- 47.**.Zhu G, Liu Y, Zhi Y, Jin Y, Li J, Shi W, et al. : PKA- and Ca(2+)-dependent p38 MAPK/CREB activation protects against manganese-mediated neuronal apoptosis. Toxicology letters 2019, 309:10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The role of p38 MAPK/CREB activation in protecting against manganese-mediated neuronal apoptosis revealed that p38 MAPK/CREB activation helped mitigate Mn-induced neuronal apoptosis, thereby improving the knowledge of Mn-induced neurotoxicity and the molecular target to opposing it.