Abstract

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) often is characterized by an eosinophilic inflammatory pattern, nowadays referred to as type 2 inflammation, although the mucosal inflammation is dominated by neutrophils in about a third of the patients. Neutrophils are typically predominant in 50% of CRS without nasal polyps (CRSsNP), but also are found to play a role in severe type 2 CRS with nasal polyp (CRSwNP) disease. This review aims at summarizing the current understanding of the eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation in CRS pathophysiology, and provides a discussion of their reciprocal interactions and the clinical impact of the mixed presentation in severe type 2 CRSwNP patients. A solid understanding of these interactions is of utmost importance when treating uncontrolled severe CRSwNP with biologicals that are preferentially directed towards type 2 inflammation. We here focus on recent findings on both eosinophilic and neutrophilic granulocytes, their subgroups and the activation status, and their interactions in CRS.

Keywords: Chronic rhinosinusitis, type 2 inflammation, eosinophils, neutrophils, activation, extracellular traps, Charcot-Leyden crystals, interleukin-17, biologicals

Heterogeneity of CRS

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is an increasing health problem affecting up to 15% of the population in western countries. CRS patients are phenotypically classified as CRS with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and CRS without nasal polyps (CRSsNP). (1, 2) While phenotyping of CRS is well established, it has been demonstrated that both CRS phenotypes can be further differentiated into endotypes, based on the underlying immune responses and cellular differentiation. (3-5) CRSwNP is in general the most severe phenotype with high rates of recurrence and comorbid asthma, and is traditionally characterized by a strong type 2 biased eosinophilic inflammation and Staphylococcus (S.) aureus colonization rates of 67%. (5-8) CRSsNP on the other hand has long been considered a type 1 – type 17 inflammation, with increased levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17 and IL-21, and a predominant presence of neutrophils. (9-11) While this dichotomous type 1 – type 2 classification is still valid in general, CRS endotyping has stressed the complexity of CRS with a frequent presentation of mixed inflammatory patterns and cellular diversity, making it obvious that type 1 – type 2 differentiation alone is not sufficient to explain the pathophysiology. (3, 5, 12-15)

Eosinophilic-neutrophilic inflammation has long been presented as black and white, almost implying mutual exclusion in CRS. Recent endotype-focused studies have challenged this traditional image, showing a more versatile picture than was anticipated based on cytokine profiles in both CRSsNP and CRSwNP patients. (12, 13) The most severe CRSsNP patients have a predominant eosinophilic inflammation and the majority of severe CRSwNP patients display a mixed pattern of eosinophilic-neutrophilic inflammation.

Despite the heterogeneity of CRS, there is a clear association between type 2 immune responses and the severity of clinical features in both CRSsNP and CRSwNP. CRS patients with a type 2 immune response have higher rates of recurrence and comorbid asthma, and a more frequent and severe presentation of clinical symptoms, while the presence of a type 1 or type 17 inflammation is inversely correlated with recurrence and associated with a milder clinical picture. (5, 12, 16-18) Interestingly, the fraction of CRS patients with a type 2 inflammation is significantly increasing in both Caucasian and Asian populations. (15, 19, 20) Because type 2 inflammation is the decisive factor for disease severity in both CRSsNP and CRSwNP, this review will be focused on eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation, their interplay and the clinical relevance in CRS with a type 2 immune response.

Type 2 CRSsNP

About 50% of the Caucasian CRSsNP patients show a mild to moderate – in some cases mixed – type 2 inflammation, similar but less pronounced compared to those in severe CRSwNP. (5, 12, 16) Type 2 immune responses in CRSsNP are – just like their CRSwNP counterparts – characterized by increased levels of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, total IgE, S. aureus enterotoxin specific (SE)-IgE and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), and elevated numbers of eosinophils in both the blood and nasal mucosa. (12) In addition, eosinophil extracellular traps (EETs) and Charcot-Leyden crystal (CLC, the crystalized form of galectin-10) deposition are also present in CRSsNP, and strongly associated with the underlying type 2 inflammation. (12) The number of neutrophils, on the other hand, are unaltered in the blood and mucosa of type 2 CRSsNP patients. (12)

Interestingly, the presentation of an eosinophilic type 2 inflammation in CRSsNP patients is associated with a worse clinical outcome, indicated by increased ratios of comorbid asthma, headache and NP recurrence over 12 years, and reduced smell/taste. (12, 16) In addition, tissue eosinophilia in CRSsNP is associated with disease severity, defined by CT, endoscopy and Smell Identification Test (SIT) scores, and reduced improvement in disease-specific and general quality of life after surgery. (21, 22)

Type 2 CRSwNP

The most severe CRSwNP patients display a type 2 inflammatory pattern – a phenomenon observed internationally in Europe, the US and Asia–, associated with profound eosinophilic inflammation. (5, 16, 20) This eosinophilic inflammation is characterized by increased eosinophil infiltration and the presence of EETs in association with S. aureus colonization and CLCs, mainly subepithelially at sites where the epithelial barrier is damaged. (7, 12, 20, 23-25)

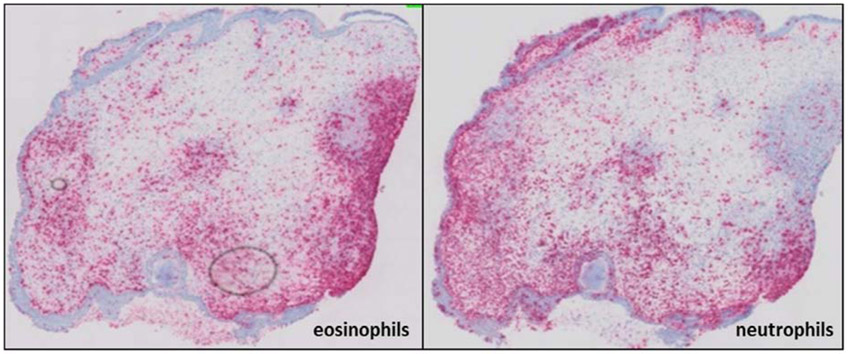

Interestingly, several studies over the last decade report the existence of a mixed eosinophilic-neutrophilic inflammation in CRSwNP patients. (4, 26) Chinese studies found that 35.8% of the CRSwNP patients displayed a mixed phenotype, associated with type 2 inflammation. (27, 28) In the western population, 26% of CRSwNP patients have been reported to display a mixed inflammation pattern. (29) Indeed, a substantial neutrophilic inflammation co-occurring with – and affected by – eosinophilia was recently demonstrated in the majority of severe type 2 CRSwNP patients (figure 1). (13, 23) In addition, a CRS cluster analysis demonstrated elevated levels of neutrophil-related proteins, such as IL-6, IL-8 and MPO, in highly type 2 eosinophilic CRSwNP patients, with a severe clinical outcome. (5)

Figure 1:

Mixed presence of eosinophils and neutrophils in CRSwNP. Eosinophils (left) and neutrophils (right) in the mucosa of CRSwNP via immunohistochemistry staining of major basic protein (MBP) and elastase, respectively.

For asthma it is well-known that the presentation of a mixed type 2 – type 17 inflammatory pattern is associated with a mixed eosinophilic – neutrophilic picture, as observed in the more severe and difficult to control asthma phenotype. (30, 31) In contrast, in CRS, the most severe patient group shows a predominant type 2 inflammation with high levels of neutrophil-related proteins, but low IL-17 levels, not linking type 17 to neutrophilia and disease severity. (5, 32) This indicates that while there is more of a predominant type 2 inflammation than a mixed type 2 – type 17 inflammation, the most severe CRSwNP patients do have a mixed eosinophilic – neutrophilic inflammation. Despite the fact that IL-17 is traditionally considered a major driving force of neutrophilia, these findings show that IL-17 levels are not a good indicator for the presence of neutrophils in the tissue of severe type 2 CRSwNP. (5, 13) However, this only seems to be the case specifically for CRSwNP patients with a severe type 2 inflammation, as some non-endotype-based studies still observed a regulatory role for IL-17 on neutrophils in CRSwNP. (33) Interestingly, CLCs could be functional to orchestrate neutrophilia specifically in this severe CRSwNP group, as we will discuss later in this review. (13, 23, 24)

Eosinophilic inflammation

Increased eosinophilic inflammation is a hallmark of severe CRSwNP in Caucasian patients, while CRSsNP patients with a type 2 immune response also display a certain degree of eosinophilic inflammation – albeit far less severe compared to CRSwNP. (7, 12, 13) Recruitment of eosinophils in the tissue of CRS is well-known to be mediated by IL-5, RANTES and eotaxins, but recent studies also demonstrated increased eosinophil migration towards S. aureus at subepithelial regions in CRSwNP tissue. (4, 7, 34-37) Interestingly, eosinophils have increased potential to affect the CRS pathophysiology due to their prolonged survival in CRS tissue, supported by elevated levels of IL-5, IL-33 and TSLP, protecting the eosinophils from apoptosis. (36-42) IL-33 and TSLP could also stimulate eosinophils and their recruitment towards impaired epithelium indirectly, by inducing IL-5 secretion of ILC2s. (7, 43)

Increased CD69 expression – a marker for eosinophil activation – was observed in eosinophils present in the nasal polyps compared to those in the blood of CRSwNP patients. (44-46) Interestingly, eosinophils are already in a priming state in the blood of CRSwNP patients, which indicate that while eosinophils are in an increased state of preparedness in the blood of CRSwNP patients, they are locally activated in the nasal polyp tissue. (47)

Once activated, eosinophils are known to secrete cytotoxic granule proteins with a primary role in protective immunity, but are very toxic at high concentrations, contributing to tissue damage and remodeling. (48-52) Besides protein mediators, eosinophils also produce pro-inflammatory lipids as cysteinyl leukotrienes that can further promote eosinophil recruitment, mucus secretion and increased vascular permeability in CRSwNP. (53-55) Eosinophils have also been reported to produce anti-inflammatory prostaglandin E2(PGE2) and pro-inflammatory prostaglandin D2(PGD2), but levels of PGE2 are decreased, while levels of PGD2 are increased in CRSwNP. (53, 56)

Another way by which eosinophils can cause tissue damage is through formation of EETs, as observed in the tissue of both CRSsNP and CRSwNP patients with a type 2 inflammation. (7, 12) These EETs consist of extracellular DNA and contain large amounts of granule proteins, which can facilitate capturing and killing of pathogens. (57) In CRSwNP, EETs are mainly observed in subepithelial regions with epithelial barrier defects, leading to the entrapment of S. aureus. (7, 25) EETs are also highly present in mucus from patients with eosinophilic CRS, increasing the mucus viscosity. (58) Interestingly, EET formation is closely associated with disease severity in chronic rhinosinusitis, regardless of the presence of NP. (59)

EET formation lays at the basis of CLC deposition, the crystalized form of galectin-10. (24, 60) CLCs are abundantly present in the mucosa and mucus of both patients with CRSsNP and CRSwNP, and are associated with type 2 inflammation. (12, 23, 24) Recent discoveries have demonstrated that CLCs are more than a degradation product of eosinophils, as they affect the epithelial barrier and sustain a neutrophilic inflammation in CRSwNP. (23) An enhanced neutrophil migration caused by CLCs was observed both in vitro and in mouse models and their association was confirmed in the tissue of severe type 2 CRSwNP patients. (13, 23, 24) CLCs also contribute to inflammation by inducing neutrophilic inflammation and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome after uptake by macrophages, causing IL-1β-driven inflammation. (23, 61) However, only the crystalized form of galectin-10 elicits those pro-inflammatory effects in CRSwNP, while soluble galectin-10 displayed anti-inflammatory effects. (23) Recently developed CLC-dissolving antibodies suppressed airway inflammation, goblet-cell metaplasia, bronchial hyperreactivity and IgE synthesis, induced by CLC or by house dust mite inhalation in a humanized mouse model. (24)

Type 2 CRSsNP, characterized by tissue eosinophilia with EET formation and CLC deposition, had significantly higher rates of asthma and recurrence, and reduced improvement in quality of life (based on RSDI and CSS scores), compared to CRSsNP without an eosinophilic type 2 response. (22, 62) However, recurrence among type 2 CRSsNP patients was still remarkably lower than that described in patients with CRSwNP (19% vs. 79% after 12 years). (6, 63) Also in CRSwNP patients, elevated numbers of activated eosinophils in the mucosa, and increased Gal10 mRNA expression in the mucus are associated with higher rates of recurrence. (64-66) Moreover, the presentation of an eosinophilic inflammation in CRSwNP was reflected by disease severity, defined by comorbid asthma, olfactory dysfunction, nasal polyp size and degree of sinonasal inflammation on CT scan. (5, 44, 55, 65, 67-69)

Interestingly, increased CLC mRNA expression was the only eosinophil-related mediator that correlates with olfactory loss in CRSsNP and CRSwNP patients. (70) This matches the observation that the presence of EETs in the tissue of CRS patients was associated with reduced olfactory function and higher Lund-Mackay scores, regardless the presence of nasal polyps. (59) These data indicated that the activation of eosinophils, more than the presence alone is decisive for the clinical outcome in both CRSsNP and CRSwNP. Identification of reliable eosinophil activation markers are thus essential for appropriate therapy assignment.

There are additional studies that may shed some light on how eosinophilic inflammation might be locally regulated within the nasal mucosa via production of endogenous factors. For example, the highly glycosylated protein DMBT1 (deleted in malignant brain tumor 1, also known as gp-340 and salivary agglutinin), produced within nasal mucosal glands and secreted into the nasal passage, is highly over-expressed in CRSwNP. (71) This has taken on greater significance with the recent discovery that a subset of nasal DBMT1 is decorated with unique and specific sialylated and sulfated glycan ligands for Siglec-8, a receptor selectively expressed on eosinophils and whose engagement causes eosinophils to die (so-called DMBT1S8). Whether the levels of DMBT1S8 are altered in various forms of CRS is currently being investigated. (72, 73)

Finally, it is important to recognize that there are some reports, such as those employing anti-eosinophil pharmacologic approaches, that raise some interesting conundrums regarding the role of eosinophils in CRS. In one sizable study, an oral agent called dexpramipexole, which causes a gradual but marked reduction in eosinophils, was administered to explore its impact on signs and symptoms of CRSwNP. As expected, use of the drug resulted in a ≈95% reduction in blood and NP eosinophils, but unexpectedly this resulted in no clinical improvement, and in fact an increase in tissue mast cells was observed. (74) A similar pattern was observed in a case report during treatment with reslizumab, an anti-IL-5 antibody. (75) This is confusing because of favorable results in phase three trials of anti-IL-5 and anti-IL-5R antibody treatments (see below).

Neutrophilic inflammation

Neutrophil infiltration has been found to be elevated in severe type 2 CRSwNP patients. (13) As discussed above, neutrophilia can occur independent from IL-17 in several CRS endotypes, especially in severe type 2 immune responses. Interestingly, CLCs can orchestrate a neutrophilic inflammation and increased neutrophil infiltration correlated significantly with markers of severe eosinophilia as EETs and CLCs in severe type 2 CRSwNP patients. (13) These findings imply that CLCs overrule IL-17 in the regulation of the increased neutrophil infiltration in severe type 2 immune responses. However, increased IL-8 production caused by CLCs indicate a potential indirect role for CLCs in the regulation of neutrophil recruitment, like earlier demonstrated for neutrophil elastase. (23, 76) S. aureus colonization is also linked to increased neutrophil migration in CRSwNP and could therefore have a prominent role in vivo triggering neutrophilia in CRSwNP. (8, 77-79)

Increased neutrophil survival has been described in patients with severe asthma. (80-84) Interestingly, neutrophil survival was only associated with tissue levels of IL-17 in CRSsNP, but not in type 2 CRSwNP, underlining the IL-17 independency of neutrophilic inflammation in severe type 2 CRSwNP. (13) GM-CSF, G-CSF, TNF-α and IL-4 stimulate the generation of long-living populations of neutrophils, however, the involvement of these cytokines in neutrophil survival, nor increased neutrophil survival has yet been described in type 2 CRSwNP. (13, 84, 85)

While mature neutrophils are dominant in the blood of CRSwNP patients, a significant shift of activated neutrophils is observed in the tissue of CRSwNP, indicating that neutrophils get activated once they enter the CRSwNP microenvironment. (13, 86, 87) Activated neutrophils contribute to the anti-bacterial cascade via phagocytosis of S. aureus and oxidative burst, and are involved in the development of airway hyperreactivity. (88, 89) Multiple studies reported increased proteolytic activity of both elastase and cathepsin G – granule proteins secreted by activated neutrophils – in the tissue of type 2 CRSwNP patients. (13, 26, 87) Once secreted, elastase and cathepsin G are less effective in microbial killing, but are able to enhance secretion and activation of IL-1 family cytokines as IL-1β, IL-33 and IL-36γ in an extremely efficient manner. (90) IL-1β and IL-33 are key players in the induction of type 2 responses in eosinophilic nasal polyps. In contrast, IL-36γ promotes the secretion of IL-8 and IL-17 from tissue neutrophils, reinforcing a positive feedback loop on their own recruitment. (26, 91-93) Substrates for neutrophil proteases as elastin, collagen and fibronectin are major components of the extracellular matrix, and their degradation is linked to tissue remodeling. (94) In addition, neutrophil serine proteases have a direct negative effect on the nasal epithelial barrier integrity and elastase can initiate goblet cell metaplasia and increased mucus production. (83, 95, 96) These findings indicate that neutrophils are not only more frequent in a severe type 2 environment, but they also affect the local inflammation via increased (proteolytic) activity.

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), generally consisting of neutrophil DNA associated with granule proteins, are present in secretions of CRSwNP and at subepithelial regions in tissue of both CRSsNP and CRSwNP patients. (13, 97-99) The pathway of NET formation is highly dependent on the individual micro-organism identity, pathogen size and additional stimuli. (99-101) CLCs evoke neutrophil death in vitro, making it likely that CLCs in tissue and secretions might contribute to tissue damage in CRS patients. (23, 99) It should be noted that neutrophil cytolysis and NET formation are different phenomena with different underlying molecular mechanisms. (102) Moreover, S. aureus – present in the majority of CRSwNP – has been found to degrade NETs, which then promotes its own survival. (103) This could explain the increased presence of NETs in CRSsNP where NETs were shown to be associated with bacterial colonization, while CLC deposition is more pronounced in CRSwNP. (12) In secretions of eosinophilic CRSwNP patients, NETs were found to increase the mucus viscosity, leading to plug formation, hampering mucociliary clearance and eventually airway damage. (104) Moreover, NETs could have pro-inflammatory effects on macrophages and stimulate tissue remodeling of the extracellular matrix. (99, 101, 105)

Interestingly, research over the last decade demonstrated the involvement of neutrophils in the establishment of a type 2 response, as dsDNA associated with NETs may directly contribute to the pathogenesis by inducing a type 2 immune response. (106) IL-33 treatment of neutrophils resulted in a polarization of the cells and also to the elective production of type 2 cytokines, like IL-4, IL-5, IL-9 and IL-13. (107) The expression of IL-9 in a subgroup of neutrophils was recently described in the tissue of CRSwNP patients. (108) Understanding the heterogeneity of neutrophils in CRS, caused by micro-environment or tissue specific stimuli could help in understanding their contribution across endotypes. So far, subsetting of neutrophils in CRS resulted in the identification of an activated subset (CD16high CD62Ldim) and IL-9 expressing neutrophils. (13, 86, 108) In asthma, in which NETs have been identified under in vivo conditions, it has been postulated that CXCR4high neutrophils are more prone to form NETs, however, no evidence on that has been found in the tissue of CRS so far. (109, 110)

Markers of severe or moderate neutrophilic inflammation are elevated in patients with difficult to treat CRS and increased presence of neutrophils in subepithelial regions of nasal polyps is associated with severe refractoriness of CRS. (111-113) Neutrophils produce high amounts of MMP-9 in CRSwNP tissue, which is linked to poor wound healing quality and regeneration of tissue after FESS. (114-116) In spite of these insights, the contribution of neutrophils in the pathophysiology and persistence of Chronic rhinosinusitis, especially in a type 2 context, remains largely unknown and needs attention to enable further improvement of treatments and endotyping of patients.

Mixed eosinophilic-neutrophilic inflammation

Based on the mixed presence described above, eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation cannot be seen as separate processes. Neutrophil infiltration was associated with EET formation and CLC-deposition – hallmarks of eosinophilic inflammation – in severe type 2 CRSwNP patients and an increased neutrophil migration towards epithelial cells was observed upon CLC stimulation in vitro. (13, 23) In addition, it is known that activated neutrophils can enhance eosinophil transmigration, and that IL-8 - mediated neutrophil recruitment induces an accumulation of eosinophils. (88, 117, 118) Interestingly, recent studies reported the expression of IL-5R and IL-9 on tissue neutrophils in asthmatic CRSwNP and the potential of neutrophils to initiate a type 2 response that could lay the basis for eosinophil infiltration. (96, 108, 110, 119) Also in mice models, neutrophil proteases elastase and cathepsin G have been reported to induce eosinophil degranulation in a Ca+2-dependent manner in vitro. (120) On the other hand, PGD2 released by activated eosinophils can – in synergy with leukotriene E4 – enhance Th2 responses and induce the production of non-classical Th2 inflammatory mediators, including IL-8 and GM-CSF at concentrations that would be sufficient to affect neutrophil migration, survival and activation. (121) Moreover, eosinophil-derived MBP has the potential to activate neutrophils and stimulate its O2− production. (122, 123) These findings indicate that, especially in severe type 2 CRSwNP patients, interplay between eosinophils and neutrophils could be essential in the maintenance of the chronicity of the disease – even after targeting the eosinophilic inflammation – by stimulating each other’s influx. (Figure 2)

Figure 2:

Pathophysiology of a mixed eosinophilic-neutrophilic inflammation in severe type 2 CRSwNP. Both an eosinophilic inflammation (left side) and a neutrophilic inflammation (right side) contribute to the pathophysiology in the mucosa of severe type 2 CRSwNP. Both responses impact the course of the disease and reciprocal interactions between eosinophils and neutrophils contribute to the persistency and severity of the disease. EETs, eosinophil extracellular traps; NETs, neutrophil extracellular traps; CLCs, Charcot-Leyden crystals, MBP, major basic protein; ECP, eosinophil cationic protein; EDN, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin; RANTES, regulated on activation, normal cell expressed and secreted.

In severe asthma, it is well known that the mixed presence of eosinophils and neutrophils is associated with disease severity and a harder to treat phenotype, defined by glucocorticoid resistance and more pronounced airway obstruction and hyperreactivity compared to predominantly eosinophilic inflammation. (124-126) Recently, the same observations were made in Caucasian CRSwNP patients, where an increased neutrophilic inflammation in association with eosinophilia was demonstrated in the most severe, difficult to treat high type 2 CRSwNP patients that suffer reduction or loss of smell, severe nasal obstruction and increased prevalence of asthma. (5, 13) CRSwNP patients with a mixed granulocytic phenotype have increased severity of tissue inflammation with a greater overall inflammatory burden, reflected by worse CT-scores, olfactory function, disease-specific quality of life and higher symptom burden, compared to predominantly eosinophilic or neutrophilic CRSwNP patients. (29, 68) The same observation was done in Asian CRS patients regarding recurrence. (112) A mixed granulocytic presence in the sputum of asthmatics was associated with severe comorbid CRS, as evaluated by the Lund-Mackay score. (127) Eosinophils and neutrophils can thus stimulate each other’s influx in CRSwNP that results in a mixed inflammation and the establishment of a more persistent and severe pathogenesis of CRSwNP.

Treatment strategies for eosinophilic – neutrophilic inflammation in CRS

Glucocorticosteroids (GCS) do target type 2 inflammatory responses better than non-type 2 responses, however, GCS resistance has been observed even in patients with type 2 CRSwNP. (27, 128) This non-responsiveness could be partially explained by the presence of a neutrophilic inflammation in CRSwNP as neutrophil-low polyps had significantly greater reductions in bilateral polyp scores, nasal congestion scores and total symptom scores, compared to neutrophil-high patients. (27) Indeed, corticosteroid treatment decreases the eosinophilic inflammation, while the neutrophilic inflammation remains unaltered or even increases. (27, 86, 98, 129-132)

Due to the predominant type 2 inflammatory pattern in severe CRS patients, current therapies target the eosinophilic/type 2 inflammation via anti-IL-4R alpha, anti-IgE, anti-IL-5 or IL-5Rα approaches. (3, 133, 134) Phase 3 trials have recently been reported with mepolizumab (anti-IL-5) and benralizumab (anti-IL-5Rα); dupilumab (anti-IL-4R) and xolair (anti-IgE) are already approved for CRSwNP in the United States and Europe. However, these innovative drugs reduce the polyp score only in about 30 to 70% of patients. (133, 135-140) Recent studies demonstrated the presence of functional IL-5Rα on a number of other cells relevant in CRS, including neutrophils, plasma cells and epithelial cells. (119, 141, 142) However, it is still unknown if non-responders are more neutrophilic than responders, but we do have evidence that neutrophils remain present in the tissue and keep affecting the pathogenesis in patients with a mixed eosinophilic-neutrophilic inflammation. (143) In fact, we recently observed the disappearance of eosinophils, EETs and CLCs in subjects with CRSwNP, who were treated for asthma with mepolizumab and benralizumab for more than 6 months, but underwent surgery for resistant nasal polyps, while neutrophils were abundant in these nasal polyp tissues (personal observation). Interestingly, treatment of bronchiectasis patients with brensocatib – an oral inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase 1 (DDP-1) that is responsible for neutrophil serine protease activation – was associated with improvements in clinical outcomes in a 24-week trial. (144)

Asthmatic patients diagnosed with predominant eosinophilic inflammation can be well-controlled with GCS or anti-IL-5 biologics. Patients with neutrophilic asthma, on the other hand, are often steroid insensitive, and to date the most effective treatment for this group is macrolides since there are currently no biologics approved for neutrophilic asthma. However, like CRSwNP, the most severe asthmatic patients have a mixed granulocytic inflammation and are difficult-to-control as they show a poor response to GCS. (30, 126, 145) Moreover, gene signatures of neutrophils did not show any significant change after treatment with benralizumab (anti-IL5Ra) in asthmatic patients. (146) These associations between CRSwNP and asthma indicates that these diseases are driven by comparable mechanisms, therefore future insights in the mixed inflammation of severe CRSwNP patients can be extrapolated to get a better understanding of asthma as well.

Conclusion and future clinical implications

While CRS is a complex disease with heterogeneous inflammatory patterns, there is a clear link between the presence of type 2 immunity and severity and persistency in both CRSsNP and CRSwNP. While severe type 2 CRSsNP is characterized by a predominant eosinophilic inflammation, severe type 2 CRSwNP patients display a mixed eosinophilic-neutrophilic inflammation. In the latter, the mixed inflammation is established by – among others – a wide range of reciprocal interactions between eosinophils and neutrophils themselves, establishing a difficult-to-manage disease. Treatments of predominant eosinophilic or neutrophilic inflammations are well-established in airway disease and still in development, while patients with a mixed inflammation may be less responsive to these specific treatments. Therefore, new treatment options, targeting the mixed inflammation by a combination of biologics may be helpful in certain patients with refractory severe and uncontrolled CRSwNP. As this phenomenon is also observed in severe asthmatics, new insights in the treatment of mixed inflammations in CRSwNP could be extrapolated for treatment of severe asthmatics, and vice versa.

Acknowledgments

Funding: C.B. was supported by grants from FWO Flanders (1515516N, EOS project nr. GOG2318N), the Interuniversity Attraction Poles Grant P7/30 and Sanofi (A17/TT/1942 and A19/TT/0828). B.S.B. is supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (U19AI136443). H.U.S. is supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 310030_184816). H.U.S. also acknowledges financial support by the Russian Government Program “Recruitment of the Leading Scientists into the Russian Institutions of Higher Education”.

Abbreviations

- CRS

Chronic Rhinosinusitis

- CRSsNP

Chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps

- CRSwNP

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

- S. aureus

Staphylococcus aureus

- IFN-γ

Interferon-gamma

- IL

Interleukin

- IgE

Immunoglobulin E

- SE-IgE

Staphylococcus enterotoxin-specific Immunoglobulin E

- ECP

Eosinophil cationic protein

- EETs

Eosinophil extracellular traps

- NETs

Neutrophil extracellular traps

- CLCs

Charcot-Leyden crystals

- SIT

Smell Identification Test

- MPO

Myeloperoxidase

- RANTES

Regulated on Activation, Normal T cell Expressed and Secreted

- TSLP

Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin

- ILC2

Group 2 Innate Lymphoid cell

- CD

Cluster of Differentiation

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- Gal10

Galectin 10

- NLRP3

NLR family pyrin domain containing 3

- RSDI

Rhinosinusitis Disability Index

- CSS

Chronic Sinusitis Survey

- DMBT1

Deleted in Malignant Brain Tumor 1

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte/Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor

- G-CSF

Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor

- TNF-α

Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha

- dsDNA

Double-stranded DNA

- CXCR4

C-X-C chemokine receptor 4

- MMP-9

Matrix metalloproteinase 9

- FESS

Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery

- MBP

Major Basic Protein

- GCS

Glucocorticosteroids

- DDP-1

dipeptidyl peptidase 1

- EDN

Eosinophil-derived neurotoxin

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: C.B. is has received research funding and/or is a consultant for Sanofi, Regeneron, Genzyme, Novartis, and GSK. T.D. declares that he has no relevant conflicts of interest. B.S.B. has received research funding from Acerta Pharma / AstraZeneca, as well as consulting fees from Regeneron, Sanofi, and GlaxoSmithkline. B.S.B. also receives remuneration for serving on the scientific advisory board of Third Harmonic Bio and Allakos, Inc. and owns stock in Allakos. He is a co-inventor on existing Siglec-8–related patents and thus may be entitled to a share of royalties received by Johns Hopkins University during development and potential sales of such products. B.S.B. is also a co-founder of Allakos; the terms of this arrangement are being managed by Johns Hopkins University and Northwestern University in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. H.U.S. is a consultant for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Esocap.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Khan A, Vandeplas G, Huynh TMT, Joish VN, Mannent L, Tomassen P, et al. The Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GALEN rhinosinusitis cohort: a large European cross-sectional study of chronic rhinosinusitis patients with and without nasal polyps. Rhinology. 2019;57(1):32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachert C, Han JK, Wagenmann M, Hosemann W, Lee SE, Backer V, et al. EUFOREA expert board meeting on uncontrolled severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and biologics: Definitions and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(1):29–36.33227318 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachert C, Zhang N, Hellings PW, Bousquet J. Endotype-driven care pathways in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(5):1543–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Zele T, Claeys S, Gevaert P, Van Maele G, Holtappels G, Van Cauwenberge P, et al. Differentiation of chronic sinus diseases by measurement of inflammatory mediators. Allergy. 2006;61(11):1280–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomassen P, Vandeplas G, Van Zele T, Cardell LO, Arebro J, Olze H, et al. Inflammatory endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis based on cluster analysis of biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(5):1449–56 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calus L, Van Bruaene N, Bosteels C, Dejonckheere S, Van Zele T, Holtappels G, et al. Twelve-year follow-up study after endoscopic sinus surgery in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. Clinical and translational allergy. 2019;9:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gevaert E, Zhang N, Krysko O, Lan F, Holtappels G, De Ruyck N, et al. Extracellular eosinophilic traps in association with Staphylococcus aureus at the site of epithelial barrier defects in patients with severe airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(6):1849–60.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Zele T, Gevaert P, Watelet JB, Claeys G, Holtappels G, Claeys C, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization and IgE antibody formation to enterotoxins is increased in nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(4):981–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho SH, Kim DW, Gevaert P. Chronic Rhinosinusitis without Nasal Polyps. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology In practice. 2016;4(4):575–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahern S, Cervin A. Inflammation and Endotyping in Chronic Rhinosinusitis-A Paradigm Shift. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Greve G, Hellings PW, Fokkens WJ, Pugin B, Steelant B, Seys SF. Endotype-driven treatment in chronic upper airway diseases. Clinical and translational allergy. 2017;7:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delemarre T, Holtappels G, De Ruyck N, Zhang N, Nauwynck H, Bachert C, et al. Type 2 Inflammation in Chronic Rhinosinusitis without Nasal Polyps: Another Relevant Endotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delemarre T, Holtappels G, De Ruyck N, Zhang N, Nauwynck H, Bachert C, et al. A substantial neutrophilic inflammation as regular part of severe type 2 chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(1):179–88.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.König K, Klemens C, Haack M, Nicoló MS, Becker S, Kramer MF, et al. Cytokine patterns in nasal secretion of non-atopic patients distinguish between chronic rhinosinusitis with or without nasal polys. Allergy, asthma, and clinical immunology : official journal of the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2016;12:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Zhang N, Bo M, Holtappels G, Zheng M, Lou H, et al. Diversity of T(H) cytokine profiles in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: A multicenter study in Europe, Asia, and Oceania. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(5):1344–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens WW, Peters AT, Tan BK, Klingler AI, Poposki JA, Hulse KE, et al. Associations Between Inflammatory Endotypes and Clinical Presentations in Chronic Rhinosinusitis. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology In practice. 2019;7(8):2812–20.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan BK, Klingler AI, Poposki JA, Stevens WW, Peters AT, Suh LA, et al. Heterogeneous inflammatory patterns in chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps in Chicago, Illinois. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(2):699–703 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Zele T, Holtappels G, Gevaert P, Bachert C. Differences in initial immunoprofiles between recurrent and nonrecurrent chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28(3):192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karin J, Tim D, Gabriele H, Cardell LO, Marit W, Claus B. Type 2 Inflammatory Shift in Chronic Rhinosinusitis During 2007-2018 in Belgium. Laryngoscope. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Gevaert E, Lou H, Wang X, Zhang L, Bachert C, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis in Asia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(5):1230–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soler ZM, Sauer DA, Mace J, Smith TL. Relationship between clinical measures and histopathologic findings in chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141(4):454–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soler ZM, Sauer D, Mace J, Smith TL. Impact of mucosal eosinophilia and nasal polyposis on quality-of-life outcomes after sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142(1):64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gevaert E, Delemarre T, De Volder J, Zhang N, Holtappels G, De Ruyck N, et al. Charcot-Leyden crystals promote neutrophilic inflammation in patients with nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):427–30.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Persson EK, Verstraete K, Heyndrickx I, Gevaert E, Aegerter H, Percier J-M, et al. Protein crystallization promotes type 2 immunity and is reversible by antibody treatment. Science. 2019;364(6442):eaaw4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morshed M, Yousefi S, Stöckle C, Simon HU, Simon D. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin stimulates the formation of eosinophil extracellular traps. Allergy. 2012;67(9):1127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Li ZY, Jiang WX, Liao B, Zhai GT, Wang N, et al. The activation and function of IL-36γ in neutrophilic inflammation in chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(5):1646–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wen W, Liu W, Zhang L, Bai J, Fan Y, Xia W, et al. Increased neutrophilia in nasal polyps reduces the response to oral corticosteroid therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(6):1522–8 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei Y, Zhang J, Wu X, Sun W, Wei F, Liu W, et al. Activated pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in neutrophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(3):1002–5.e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Succar EF, Li P, Ely KA, Chowdhury NI, Chandra RK, Turner JH. Neutrophils are underrecognized contributors to inflammatory burden and quality of life in chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy. 2020;75(3):713–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ray A, Kolls JK. Neutrophilic Inflammation in Asthma and Association with Disease Severity. Trends Immunol. 2017;38(12):942–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Volder J, Vereecke L, Joos G, Maes T. Targeting neutrophils in asthma: A therapeutic opportunity? Biochemical Pharmacology. 2020;182:114292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derycke L, Eyerich S, Van Crombruggen K, Pérez-Novo C, Holtappels G, Deruyck N, et al. Mixed T helper cell signatures in chronic rhinosinusitis with and without polyps. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e97581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derycke L, Zhang N, Holtappels G, Dutre T, Bachert C. IL-17A as a regulator of neutrophil survival in nasal polyp disease of patients with and without cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11(3):193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hulse KE, Stevens WW, Tan BK, Schleimer RP. Pathogenesis of nasal polyposis. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2015;45(2):328–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bachert C, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, Johansson SGO, van Cauwenberge P. Total and specific IgE in nasal polyps is related to local eosinophilic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(4):607–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon HU, Yousefi S, Schranz C, Schapowal A, Bachert C, Blaser K. Direct demonstration of delayed eosinophil apoptosis as a mechanism causing tissue eosinophilia. J Immunol. 1997;158(8):3902–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nonaka M, Pawankar R, Saji F, Yagi T. Distinct expression of RANTES and GM-CSF by lipopolysaccharide in human nasal fibroblasts but not in other airway fibroblasts. International archives of allergy and immunology. 1999;119(4):314–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bagley CJ, Lopez AF, Vadas MA. New frontiers for IL-5. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(6, Part 1):725–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geering B, Stoeckle C, Conus S, Simon HU. Living and dying for inflammation: neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils. Trends Immunol. 2013;34(8):398–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohno I, Lea R, Finotto S, Marshall J, Denburg J, Dolovich J, et al. Granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) gene expression by eosinophils in nasal polyposis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1991;5(6):505–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong CK, Hu S, Cheung PF, Lam CW. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin induces chemotactic and prosurvival effects in eosinophils: implications in allergic inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43(3):305–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cherry WB, Yoon J, Bartemes KR, Iijima K, Kita H. A novel IL-1 family cytokine, IL-33, potently activates human eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(6):1484–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang N, Van Crombruggen K, Gevaert E, Bachert C. Barrier function of the nasal mucosa in health and type-2 biased airway diseases. Allergy. 2016;71(3):295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yun Y, Kanda A, Kobayashi Y, Van Bui D, Suzuki K, Sawada S, et al. Increased CD69 expression on activated eosinophils in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis correlates with clinical findings. Allergology international : official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology. 2020;69(2):232–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsumoto K, Appiah-Pippim J, Schleimer RP, Bickel CA, Beck LA, Bochner BS. CD44 and CD69 represent different types of cell-surface activation markers for human eosinophils. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;18(6):860–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Julius P, Luttmann W, Knoechel B, Kroegel C, Matthys H, Virchow JC Jr. CD69 surface expression on human lung eosinophils after segmental allergen provocation. The European respiratory journal. 1999;13(6):1253–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dupuch V, Tridon A, Ughetto S, Walrand S, Bonnet B, Dubray C, et al. Activation state of circulating eosinophils in nasal polyposis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018;8(5):584–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yousefi S, Simon D, Simon HU. Eosinophil extracellular DNA traps: molecular mechanisms and potential roles in disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(6):736–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frigas E, Motojima S, Gleich GJ. The eosinophilic injury to the mucosa of the airways in the pathogenesis of bronchial asthma. The European respiratory journal Supplement. 1991;13:123s–35s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soragni A, Yousefi S, Stoeckle C, Soriaga AB, Sawaya MR, Kozlowski E, et al. Toxicity of eosinophil MBP is repressed by intracellular crystallization and promoted by extracellular aggregation. Molecular cell. 2015;57(6):1011–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watelet JB, Bachert C, Claeys C, Van Cauwenberge P. Matrix metalloproteinases MMP-7, MMP-9 and their tissue inhibitor TIMP-1: expression in chronic sinusitis vs nasal polyposis. Allergy. 2004;59(1):54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimizu S, Ogawa T, Takezawa K, Tojima I, Kouzaki H, Shimizu T. Tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor in nasal mucosa and nasal secretions of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyp. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2015;29(4):235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pérez-Novo CA, Watelet JB, Claeys C, Van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C. Prostaglandin, leukotriene, and lipoxin balance in chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(6):1189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pérez-Novo CA, Claeys C, Van Zele T, Holtapples G, Van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C. Eicosanoid metabolism and eosinophilic inflammation in nasal polyp patients with immune response to Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins. American journal of rhinology. 2006;20(4):456–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bochner BS, Stevens WW. Biology and Function of Eosinophils in Chronic Rhinosinusitis With or Without Nasal Polyps. Allergy, asthma & immunology research. 2021;13(1):8–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshimura T, Yoshikawa M, Otori N, Haruna S, Moriyama H. Correlation between the prostaglandin D(2)/E(2) ratio in nasal polyps and the recalcitrant pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis associated with bronchial asthma. Allergology international : official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology. 2008;57(4):429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yousefi S, Gold JA, Andina N, Lee JJ, Kelly AM, Kozlowski E, et al. Catapult-like release of mitochondrial DNA by eosinophils contributes to antibacterial defense. Nat Med. 2008;14(9):949–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ueki S, Konno Y, Takeda M, Moritoki Y, Hirokawa M, Matsuwaki Y, et al. Eosinophil extracellular trap cell death–derived DNA traps: Their presence in secretions and functional attributes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(1):258–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hwang CS, Park SC, Cho HJ, Park DJ, Yoon JH, Kim CH. Eosinophil extracellular trap formation is closely associated with disease severity in chronic rhinosinusitis regardless of nasal polyp status. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ueki S, Tokunaga T, Melo RCN, Saito H, Honda K, Fukuchi M, et al. Charcot-Leyden crystal formation is closely associated with eosinophil extracellular trap cell death. Blood. 2018;132(20):2183–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodríguez-Alcázar JF, Ataide MA, Engels G, Schmitt-Mabmunyo C, Garbi N, Kastenmüller W, et al. Charcot-Leyden Crystals Activate the NLRP3 Inflammasome and Cause IL-1β Inflammation in Human Macrophages. J Immunol. 2019;202(2):550–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith TL, Litvack JR, Hwang PH, Loehrl TA, Mace JC, Fong KJ, et al. Determinants of outcomes of sinus surgery: a multi-institutional prospective cohort study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142(1):55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.DeConde AS, Mace JC, Levy JM, Rudmik L, Alt JA, Smith TL. Prevalence of polyp recurrence after endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. The Laryngoscope. 2017;127(3):550–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vlaminck S, Vauterin T, Hellings P, Jorissen M, Acke F, Van Cauwenberge P, et al. The importance of local eosinophilia in the surgical outcome of chronic rhinosinusitis: a 3-year prospective observational study. American Journal of Rhinology and Allergy. 2014;28:260–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vlaminck S, Acke F, Prokopakis E, Speleman K, Kawauchi H, van Cutsem JC, et al. Surgery in Nasal Polyp Patients: Outcome After a Minimum Observation of 10 Years. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2020:1945892420961964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qi S, Yan B, Liu C, Wang C, Zhang L. Predictive significance of Charcot-Leyden Crystal mRNA levels in nasal brushing for nasal polyp recurrence. Rhinology. 2020;58(2):166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hauser LJ, Chandra RK, Li P, Turner JH. Role of tissue eosinophils in chronic rhinosinusitis-associated olfactory loss. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017;7(10):957–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lou H, Meng Y, Piao Y, Zhang N, Bachert C, Wang C, et al. Cellular phenotyping of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Rhinology. 2016;54(2):150–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ikeda K, Shiozawa A, Ono N, Kusunoki T, Hirotsu M, Homma H, et al. Subclassification of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyp based on eosinophil and neutrophil. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(11):E1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lavin J, Min JY, Lidder AK, Huang JH, Kato A, Lam K, et al. Superior turbinate eosinophilia correlates with olfactory deficit in chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(10):2210–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Z, Kim J, Sypek JP, Wang IM, Horton H, Oppenheim FG, et al. Gene expression profiles in human nasal polyp tissues studied by means of DNA microarray. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(4):783–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gonzalez-Gil A, Li TA, Porell RN, Fernandes SM, Tarbox HE, Lee HS, et al. Isolation, identification, and characterization of the human airway ligand for the eosinophil and mast cell immunoinhibitory receptor Siglec-8. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bochner BS. "Siglec"ting the allergic response for therapeutic targeting. Glycobiology. 2016;26(6):546–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Laidlaw TM, Prussin C, Panettieri RA, Lee S, Ferguson BJ, Adappa ND, et al. Dexpramipexole depletes blood and tissue eosinophils in nasal polyps with no change in polyp size. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(2):E61–e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Staudacher AG, Peters AT, Carter RG, Welch KC, Stevens WW. Decreased nasal polyp eosinophils but increased mast cells in a patient with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease treated with reslizumab. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2020;125(4):490–3.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nakamura H, Yoshimura K, McElvaney NG, Crystal RG. Neutrophil elastase in respiratory epithelial lining fluid of individuals with cystic fibrosis induces interleukin-8 gene expression in a human bronchial epithelial cell line. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1992;89(5):1478–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Suh JD, Ramakrishnan V, Palmer JN. Biofilms. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2010;43(3):521–30, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang X, Du J, Zhao C. Bacterial biofilms are associated with inflammatory cells infiltration and the innate immunity in chronic rhinosinusitis with or without nasal polyps. Inflammation. 2014;37(3):871–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huvenne W, Callebaut I, Reekmans K, Hens G, Bobic S, Jorissen M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B augments granulocyte migration and survival via airway epithelial cell activation. Allergy. 2010;65(8):1013–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grunwell JR, Stephenson ST, Tirouvanziam R, Brown LAS, Brown MR, Fitzpatrick AM. Children with Neutrophil-Predominant Severe Asthma Have Proinflammatory Neutrophils With Enhanced Survival and Impaired Clearance. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology In practice. 2019;7(2):516–25.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Uddin M, Nong G, Ward J, Seumois G, Prince LR, Wilson SJ, et al. Prosurvival activity for airway neutrophils in severe asthma. Thorax. 2010;65(8):684–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sigua JA, Buelow B, Cheung DS, Buell E, Hunter D, Klancnik M, et al. CD49d-expressing neutrophils differentiate atopic from nonatopic individuals. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):901–4.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Silvestre-Roig C, Hidalgo A, Soehnlein O. Neutrophil heterogeneity: implications for homeostasis and pathogenesis. Blood. 2016;127(18):2173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chakravarti A, Rusu D, Flamand N, Borgeat P, Poubelle PE. Reprogramming of a subpopulation of human blood neutrophils by prolonged exposure to cytokines. Laboratory Investigation. 2009;89(10):1084–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Garley M, Jabłońska E. Heterogeneity Among Neutrophils. Archivum immunologiae et therapiae experimentalis. 2018;66(1):21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Arebro J, Drakskog C, Winqvist O, Bachert C, Kumlien Georén S, Cardell L-O. Subsetting reveals CD16high CD62Ldim neutrophils in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Allergy. 2019;74(12):2499–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim YS, Han D, Kim J, Kim DW, Kim YM, Mo JH, et al. In-Depth, Proteomic Analysis of Nasal Secretions from Patients With Chronic Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps. Allergy, asthma & immunology research. 2019;11(5):691–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arebro J, Ekstedt S, Hjalmarsson E, Winqvist O, Kumlien Georen S, Cardell LO. A possible role for neutrophils in allergic rhinitis revealed after cellular subclassification. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ekstedt S, Säfholm J, Stenberg H, Tufvesson ET, Diamant Z, Bjermer L, et al. Dividing neutrophils in subsets, reveals a significant role for CD16highCD62Ldim neutrophils in the development of airway hyperreactivity. European Respiratory Journal. 2019;54(suppl 63):PA4092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Clancy DM, Henry CM, Sullivan GP, Martin SJ. Neutrophil extracellular traps can serve as platforms for processing and activation of IL-1 family cytokines. Febs j. 2017;284(11):1712–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23(5):479–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Teufelberger AR, Nordengrun M, Braun H, Maes T, De Grove K, Holtappels G, et al. The IL-33/ST2 axis is crucial in type 2 airway responses induced by Staphylococcus aureus-derived serine protease-like protein D. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(2):549–59.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kato A. Immunopathology of chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergology international : official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology. 2015;64(2):121–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jasper AE, McIver WJ, Sapey E, Walton GM. Understanding the role of neutrophils in chronic inflammatory airway disease. F1000Research. 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kao SS, Ramezanpour M, Bassiouni A, Wormald PJ, Psaltis AJ, Vreugde S. The effect of neutrophil serine proteases on human nasal epithelial cell barrier function. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019;9(10):1220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Voynow JA, Fischer BM, Malarkey DE, Burch LH, Wong T, Longphre M, et al. Neutrophil elastase induces mucus cell metaplasia in mouse lung. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2004;287(6):L1293–L302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hwang JW, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Choi IH, Han HM, Lee KJ, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in nasal secretions of patients with stable and exacerbated chronic rhinosinusitis and their contribution to induce chemokine secretion and strengthen the epithelial barrier. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2019;49(10):1306–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cao Y, Chen F, Sun Y, Hong H, Wen Y, Lai Y, et al. LL-37 promotes neutrophil extracellular trap formation in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2019;49(7):990–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Delgado-Rizo V, Martínez-Guzmán MA, Iñiguez-Gutierrez L, García-Orozco A, Alvarado-Navarro A, Fafutis-Morris M. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Its Implications in Inflammation: An Overview. Frontiers in immunology. 2017;8:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Warnatsch A, Tsourouktsoglou TD, Branzk N, Wang Q, Reincke S, Herbst S, et al. Reactive Oxygen Species Localization Programs Inflammation to Clear Microbes of Different Size. Immunity. 2017;46(3):421–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dicker AJ, Crichton ML, Pumphrey EG, Cassidy AJ, Suarez-Cuartin G, Sibila O, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps are associated with disease severity and microbiota diversity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(1):117–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yousefi S, Stojkov D, Germic N, Simon D, Wang X, Benarafa C, et al. Untangling "NETosis" from NETs. European journal of immunology. 2019;49(2):221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Thammavongsa V, Missiakas DM, Schneewind O. Staphylococcus aureus degrades neutrophil extracellular traps to promote immune cell death. Science. 2013;342(6160):863–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ueki S, Melo RC, Ghiran I, Spencer LA, Dvorak AM, Weller PF. Eosinophil extracellular DNA trap cell death mediates lytic release of free secretion-competent eosinophil granules in humans. Blood. 2013;121(11):2074–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Grabcanovic-Musija F, Obermayer A, Stoiber W, Krautgartner W-D, Steinbacher P, Winterberg N, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation characterises stable and exacerbated COPD and correlates with airflow limitation. Respiratory Research. 2015;16(1):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Toussaint M, Jackson DJ, Swieboda D, Guedan A, Tsourouktsoglou TD, Ching YM, et al. Host DNA released by NETosis promotes rhinovirus-induced type-2 allergic asthma exacerbation. Nat Med. 2017;23(6):681–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sun B, Zhu L, Tao Y, Sun H-X, Li Y, Wang P, et al. Characterization and allergic role of IL-33-induced neutrophil polarization. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2018;15(8):782–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Delemarre T, De Ruyck N, Holtappels G, Bachert C, Gevaert E. Unravelling the expression of interleukin-9 in chronic rhinosinusitis: A possible role for Staphylococcus aureus. Clinical and translational allergy. 2020;10(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dworski R, Simon HU, Hoskins A, Yousefi S. Eosinophil and neutrophil extracellular DNA traps in human allergic asthmatic airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(5):1260–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Radermecker C, Sabatel C, Vanwinge C, Ruscitti C, Maréchal P, Perin F, et al. Locally instructed CXCR4(hi) neutrophils trigger environment-driven allergic asthma through the release of neutrophil extracellular traps. Nature immunology. 2019;20(11):1444–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Liao B, Liu JX, Li ZY, Zhen Z, Cao PP, Yao Y, et al. Multidimensional endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis and their association with treatment outcomes. Allergy. 2018;73(7):1459–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kim DK, Kim JY, Han YE, Kim JK, Lim HS, Eun KM, et al. Elastase-Positive Neutrophils Are Associated With Refractoriness of Chronic Rhinosinusitis With Nasal Polyps in an Asian Population. Allergy, asthma & immunology research. 2020;12(1):42–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kim DK, Lim HS, Eun KM, Seo Y, Kim JK, Kim YS, et al. Subepithelial neutrophil infiltration as a predictor of the surgical outcome of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Rhinology. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Watelet JB, Demetter P, Claeys C, Van Cauwenberge P, Cuvelier C, Bachert C. Neutrophil-derived metalloproteinase-9 predicts healing quality after sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(1):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Watelet JB, Claeys C, Van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C. Predictive and monitoring value of matrix metalloproteinase-9 for healing quality after sinus surgery. Wound repair and regeneration : official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society. 2004;12(4):412–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Watelet JB, Demetter P, Claeys C, Cauwenberge P, Cuvelier C, Bachert C. Wound healing after paranasal sinus surgery: neutrophilic inflammation influences the outcome. Histopathology. 2006;48(2):174–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nakagome K, Matsushita S, Nagata M. Neutrophilic inflammation in severe asthma. International archives of allergy and immunology. 2012;158Suppl 1:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kikuchi I, Kikuchi S, Kobayashi T, Hagiwara K, Sakamoto Y, Kanazawa M, et al. Eosinophil Trans-Basement Membrane Migration Induced by Interleukin-8 and Neutrophils. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2006;34(6):760–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gorski SA, Lawrence MG, Hinkelman A, Spano MM, Steinke JW, Borish L, et al. Expression of IL-5 receptor alpha by murine and human lung neutrophils. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Liu H, Lazarus SC, Caughey GH, Fahy JV. Neutrophil elastase and elastase-rich cystic fibrosis sputum degranulate human eosinophils in vitro. The American journal of physiology. 1999;276(1):L28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Xue L, Fergusson J, Salimi M, Panse I, Ussher JE, Hegazy AN, et al. Prostaglandin D2 and leukotriene E4 synergize to stimulate diverse TH2 functions and TH2 cell/neutrophil crosstalk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(5):1358–66.e1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Haskell M, Moy J, Gleich G, Thomas L. Analysis of signaling events associated with activation of neutrophil superoxide anion production by eosinophil granule major basic protein. Blood. 1995;86(12):4627–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Moy JN, Thomas LL, Whisler LC. Eosinophil major basic protein enhances the expression of neutrophil CR3 and p150,95. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92(4):598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Irvin C, Zafar I, Good J, Rollins D, Christianson C, Gorska MM, et al. Increased frequency of dual-positive TH2/TH17 cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid characterizes a population of patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(5):1175–86.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hastie AT, Moore WC, Meyers DA, Vestal PL, Li H, Peters SP, et al. Analyses of asthma severity phenotypes and inflammatory proteins in subjects stratified by sputum granulocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(5):1028–36 e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Moore WC, Hastie AT, Li X, Li H, Busse WW, Jarjour NN, et al. Sputum neutrophil counts are associated with more severe asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(6):1557–63.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nishio T, Wakahara K, Suzuki Y, Nishio N, Majima S, Nakamura S, et al. Mixed cell type in airway inflammation is the dominant phenotype in asthma patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergology international : official journal of the Japanese Society of Allergology. 2019;68(4):515–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gurrola J II, Borish L. Chronic rhinosinusitis: Endotypes, biomarkers, and treatment response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(6):1499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Green RH, Brightling CE, Woltmann G, Parker D, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Analysis of induced sputum in adults with asthma: identification of subgroup with isolated sputum neutrophilia and poor response to inhaled corticosteroids. Thorax. 2002;57(10):875–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pujols L, Alobid I, Benítez P, Martínez-Antón A, Roca-Ferrer J, Fokkens WJ, et al. Regulation of glucocorticoid receptor in nasal polyps by systemic and intranasal glucocorticoids. Allergy. 2008;63(10):1377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Cox G. Glucocorticoid treatment inhibits apoptosis in human neutrophils. Separation of survival and activation outcomes. J Immunol. 1995;154(9):4719–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Liles WC, Dale DC, Klebanoff SJ. Glucocorticoids inhibit apoptosis of human neutrophils. Blood. 1995;86(8):3181–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bachert C, Han JK, Desrosiers M, Hellings PW, Amin N, Lee SE, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pauwels B, Jonstam K, Bachert C. Emerging biologics for the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015;11(3):349–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Bachert C, Sousa AR, Lund VJ, Scadding GK, Gevaert P, Nasser S, et al. Reduced need for surgery in severe nasal polyposis with mepolizumab: Randomized trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(4):1024–31.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Bachert C, Zhang N, Cavaliere C, Weiping W, Gevaert E, Krysko O. Biologics for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(3):725–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Bachert C, Mannent L, Naclerio RM, Mullol J, Ferguson BJ, Gevaert P, et al. Effect of Subcutaneous Dupilumab on Nasal Polyp Burden in Patients With Chronic Sinusitis and Nasal Polyposis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2016;315(5):469–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gevaert P, Van Bruaene N, Cattaert T, Van Steen K, Van Zele T, Acke F, et al. Mepolizumab, a humanized anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody, as a treatment option for severe nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(5):989–95.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Gevaert P, Omachi TA, Corren J, Mullol J, Han J, Lee SE, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in nasal polyposis: 2 randomized phase 3 trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(3):595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Gevaert P, Calus L, Van Zele T, Blomme K, De Ruyck N, Bauters W, et al. Omalizumab is effective in allergic and nonallergic patients with nasal polyps and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(1):110–6.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Barretto KT, Brockman-Schneider RA, Kuipers I, Basnet S, Bochkov YA, Altman MC, et al. Human airway epithelial cells express a functional IL-5 receptor. Allergy. 2020;75(8):2127–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Buchheit KM, Dwyer DF, Ordovas-Montanes J, Katz HR, Lewis E, Vukovic M, et al. IL-5Rα marks nasal polyp IgG4- and IgE-expressing cells in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(6):1574–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Lan F, Zhang L. Understanding the Role of Neutrophils in Refractoriness of Chronic Rhinosinusitis With Nasal Polyps. Allergy, asthma & immunology research. 2020;12(1):1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Chalmers JD, Haworth CS, Metersky ML, Loebinger MR, Blasi F, Sibila O, et al. Phase 2 Trial of the DPP-1 Inhibitor Brensocatib in Bronchiectasis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(22):2127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Wu W, Bleecker E, Moore W, Busse WW, Castro M, Chung KF, et al. Unsupervised phenotyping of Severe Asthma Research Program participants using expanded lung data. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(5):1280–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Sridhar S, Liu H, Pham T-H, Damera G, Newbold P. Modulation of blood inflammatory markers by benralizumab in patients with eosinophilic airway diseases. Respiratory Research. 2019;20(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]