Abstract

Factors such as antibody clearance and target affinity can influence antibodies’ effective doses for specific indications. However, these factors vary considerably across antibody classes, precluding direct and quantitative comparisons. Here, we apply a dimensionless metric, the therapeutic exposure affinity ratio (TEAR), which normalizes the therapeutic doses by antibody bioavailability, systemic clearance and target-binding property to enable direct and quantitative comparisons of therapeutic doses. Using TEAR, we revisited and dissected the doses of up to 60 approved antibodies. We failed to detect a significant influence of target baselines, turnovers or anatomical locations on antibody therapeutic doses, challenging the traditional perceptions. We highlight the importance of antibodies’ modes of action for therapeutic doses and dose selections; antibodies that work through neutralizing soluble targets show higher TEARs than those working through other mechanisms. Overall, our analysis provides insights into the factors that influence antibody doses, and the factors that are crucial for antibodies’ pharmacological effects.

Introduction

Successfully developing a therapeutic monoclonal antibody requires the integration of expertise from multiple disciplines. Many aspects need to be rigorously evaluated at each development stage, including the target biology and pathological relevance, antibody formats and properties, optimal doses and exposures, and efficacy–toxicity profiles [1]. After antibodies enter the clinical stages, the focus of development will be on establishing safety and efficacy profiles and determining the optimal dose and regimen that will result in the highest efficacy–toxicity ratio [2].

There are many factors that might influence the effective doses for an antibody (Figure 1). Model-informed drug development (MIDD) approaches have had substantial roles in antibody dose selection, optimization and individualization [3]. The implementation of MIDD approaches in dose selection entails thorough consideration of the target attributes (baseline and turnovers), antibody pharmacokinetics (PK), target-binding properties, modes of action (MoAs) and patient characteristics [4–9]. A systematic analysis of these factors by surveying the labeled doses of approved antibodies can help us to better understand the factors that contribute the most to dose selection.

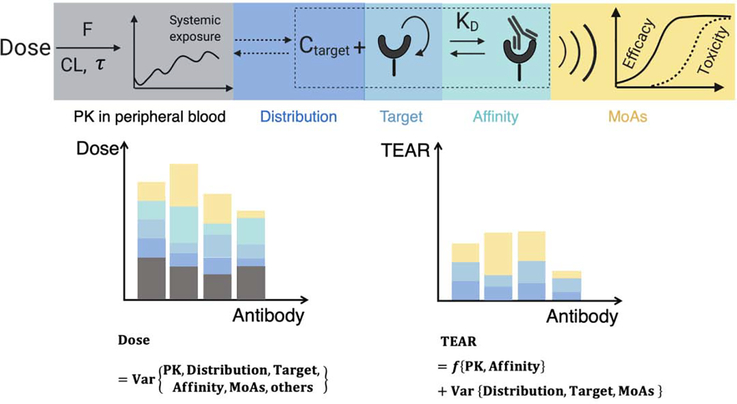

Figure 1.

Schematic of the TEAR. Factors such as the PK in the peripheral blood, antibody distribution, target turnover and baseline, antibody affinity, and MoAs are routinely considered in antibody development. TEAR takes into account the components with higher quantification certainty, including bioavailability (F), systemic clearance (CL), and binding affinity (KD), and serves as a metric reflecting the pRO. The factors beyond pRO that are not considered in TEAR, such as the target distribution, target properties and MoAs, will lead to variance in the TEARs. The impact of these factors can be investigated on the basis of the TEARs.

However, therapeutic doses are mostly determined on a case-by-case basis. The factors that affect antibody therapeutic doses vary considerably, complicating direct and quantitative comparisons across antibody classes and indications [10–12]. Because of their diverse clinical indications and distinctive dose–response relationships, antibodies often have broadly different therapeutic doses, even for those with identical targets and similar target-binding properties. For example, rituximab and obinutuzumab have very different approved doses and dosing regimens for treating chronic lymphocytic leukemia despite their close affinities to CD20 [13]. Furthermore, the factors considered in the dose-searching process differ between early and late clinical trials. First-in-human (FIH) dose decisions often consider the target and target-binding properties to ensure safe animal-to-human translation. By contrast, the confirmation of the therapeutic doses in phase II or III trials is usually based on the clinical efficacy–toxicity profiles and dose–response relationships [10,11,14–17]. As such, the factors affecting antibody doses cannot be directly examined across antibodies. Many retrospective studies have investigated antibody doses and the relevant factors in regulatory perspectives, without quantitative assessments of the pertinent factors that define the therapeutic doses and the dose–response relationships [10,11].

Here, we developed a dimensionless metric, the therapeutic exposure affinity ratio (TEAR), to facilitate direct analyses and quantitative comparisons of the factors that influence therapeutic doses across antibodies. Using TEAR, we revisited all the influencing factors and then performed a quantitative analysis of up to 60 antibodies that have been approved by either the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) from 1997 to 2019. We quantitatively evaluated the factors associated with the doses and dose selections across antibodies, indications, target properties and development stages.

Definition of TEAR

Many factors are involved in the cascade of antibody pharmacological actions. These factors shape the translation from the dose to the efficacy/safety outcome, including the antibody PK, biodistribution into the target tissue, target-binding affinity, target turnovers and many immunological events following target activation (Figure 1). A complete summary of all surveyed antibodies is provided in the supplementary material online, including their PK parameters, label doses, indications and target properties (baselines, turnover, locations and affinity). The variance of therapeutic doses is influenced by almost all the factors involved in antibody pharmacological actions (Figure 1). These factors vary drastically across antibody classes and indications, precluding direct and quantitative comparisons.

TEAR was developed as a dimensionless metric, and it is defined in Box 1. TEAR, by normalizing therapeutic doses through the use of factors with relatively high quantitative certainty, such as bioavailability (F), systemic clearance (CL) and target-binding property (KD), can help us focus on factors that are difficult to quantify or evaluate, such as MoAs and target anatomical locations. The remaining factors that are not included in the TEAR equation account for the variance of TEAR (Figure 1). Instead of comparing therapeutic doses directly, TEAR allows us to compare the affinity-normalized therapeutic concentration and further compare the factors that influence the therapeutic doses. For instance, if most of antibody X’s targets are in the extravascular space, its TEAR should be relatively higher to compensate for the antibody-limited extravascular distributions [18]. Likewise, if antibody Y’s targets are mainly in the blood, its TEAR should be relatively lower than that of antibody X. This speculation is valid only when the target location and antibody tissue distribution affect the therapeutic dose levels; otherwise, there will be a limited difference between the TEARs of X and Y even with different target locations. Similarly, we can use TEAR values to quantitatively and systematically evaluate the factors that influence the therapeutic doses, including the target attributes (baselines and turnovers), MoAs, disease types and even the development stages. TEARs make it possible to make comparisons across antibodies. Moreover, TEARs have a great dynamic range and follow the normal distribution, ensuring robustness in statistical analysis (Figure S1 in the supplementary material online).

Box 1. Definition of TEAR.

TEAR = log (Css/KD). In the definition of TEAR, Css is plasma therapeutic concentration at the steady-state under the approved maintenance doses and dosing regimens, and KD is target affinity, known as the target dissociation constant measured using the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) approach.

When antibodies achieve steady-state kinetics, Css is derived using the following equation:

| [I] |

where F is the bioavailability; Dose and are the therapeutic maintenance dose and dosing interval, respectively; and CL is the systemic clearance. For approved antibodies with nonlinear clearance, the CL at the Css is applied (see the supplementary material online).

Assuming that the KD derived in vitro reveals the antibody–target binding in vivo, Css/KD can be used to reflect the pRO at the approved therapeutic doses, according to the Hill–Langmuir function, as shown in the equations below.

| [II] |

| [III] |

As shown in Equation III, pRO is a function of Css/KD. When Css/KD = 100, TEAR = 2 and pRO ≈ 99%. Notably, pRO cannot be directly interpreted as the RO at the sites of action when the targets are in tissues. However, pRO or TEAR can be taken as an indicator of the relative levels of approved therapeutic doses for an antibody compared to others. The specifications for these parameters are provided in Table S1 in the supplementary material online.

Notably, we defined the log-transformed Css/KD as TEAR considering that the log-transformed Css/KD values fall within a normal distribution, enabling robust statistical comparison (Figure S1 in the supplementary material online).

When available, the FIHD and the MAD tested in the clinical trials of an approved antibody were analyzed. All the tested doses in the phase II trials recorded by the FDA reviews were also included in this study. For single administration in clinical trials, τ was set to the mean dosing interval (14 days). FIHD, MAD and P2D were used to derive three metrics similar to the therapeutic exposure affinity ratio (TEAR), namely TEARFIHD [log (Css,FIHD/KD)], TEARMAD [log (Css,MAD/KD)] and TEARP2D [log (Css,P2D/KD)], for comparison across antibodies. A summary of the FIHDs, MADs and P2Ds is provided in Table S3 in the supplementary material online.

Receptor occupancy in the circulation

Receptor occupancy (RO) is the most common indicator for dose adequacy, which is often used to predict antibody efficacy and safety profiles [14,15]. The measurement of RO in vivo or ex vivo reveals an antibody’s key properties for engaging with its target, a crucial step before the pharmacological actions and therapeutic responses. After the safety profile has been cleared and the risk of hyper-inflammation in the early clinical stages has been minimized, a nearly saturated RO (close to 100%) is usually desired for the highest efficacy potential [14,15]. Together with PK analysis, RO measurement is often integrated to support the evaluation of the effective doses and dosing regimens of antibodies [14,15].

RO is typically measured on circulating targets or blood cells from peripheral blood samples using flow cytometry. Many studies have measured the RO in peripheral blood (pRO) to assist dose selection at the early clinical stages [19–25]. The phase 2 dose of anti-SLAM-7 elotuzumab was set at 20 mg/kg given the fact that the SLAM-7 RO at this dose was ≥ 95% [19]. The anti-CD38 antibody daratumumab had a phase II dose of 16 mg/kg because of the nearly saturated target at this dose level [20,21]. The phase II dose of the anti-PD-1 (programmed cell death protein 1) antibody pembrolizumab was determined based on the evidence that the maximum pRO was reached at ≥ 1 mg/kg every three weeks [22]. Notably, the targets of these antibodies are primarily in the circulation or the lymphoid tissues, which have high antibody permeability. For antibodies with targets in distant tissues where the antibody has limited distribution, the pRO will be limited in its ability to reflect the target engagement at the site of action [26]. Therefore, the anatomical location of the target is often regarded as an important factor that influences antibody therapeutic doses, which will be reviewed in the next section.

Developed based on the Hill–Langmuir function, TEAR can infer the pRO because the plasma concentration is considered in Equation I in Box 1. Based on Equation II in Box 1, TEAR = 0.5 represents pRO ≈ 76%, and TEAR = 2 suggests a nearly complete pRO (≈ 99%). TEAR ≥ 2 indicates that the labeled therapeutic dose is more than enough to saturate the peripheral circulating targets. Likewise, when an antibody has TEAR ≥ 2, other factors beyond the pRO apparently influence the selected therapeutic dose.

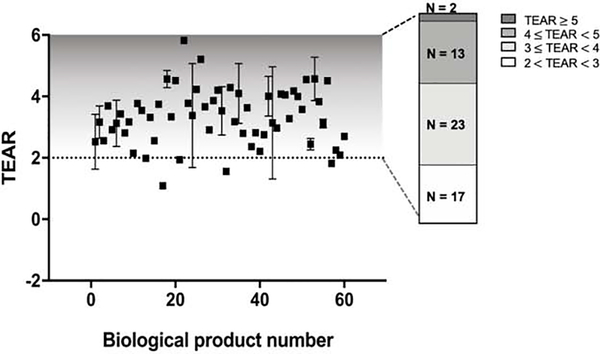

Using TEAR, we evaluated the pRO of most approved antibodies (n = 60) at their therapeutic doses. As seen in Figure 2, the TEARs of the 60 approved antibodies ranged from 1.1 to 5.9, which yielded approximately 92–100% pRO. Interestingly, most of the antibodies (55 out of 60) had TEARs > 2, suggesting that most antibodies at their approved therapeutic doses could almost completely saturate the circulating targets. Moreover, 38 of the 55 antibodies had therapeutic doses at least 10 times higher than the doses yielding 99% pRO (TEAR ≥ 3), and 15 antibodies had therapeutic doses over 100-fold higher than the doses yielding 99% pRO (TEAR ≥ 4). The most intriguing observation was that the antibodies whose targets were primarily in the peripheral blood had even higher TEARs than the antibodies with distal targets. For example, emapalumab, an antibody that neutralizes the circulating interferon-γ (IFNγ), had the highest TEAR (5.83). Therefore, we speculate that additional factors beyond pRO are involved in determining antibodies’ therapeutic doses, even for those whose targets are in the peripheral blood.

Figure 2.

Most approved antibodies have therapeutic doses oversaturating the targets in plasma, as shown by the TEAR metric. Up to 60 licensed antibodies were included in the analysis. Most of the surveyed antibodies had TEARs > 2, indicating that such antibodies could saturate their targets in the peripheral blood (pRO τ 99%) at the therapeutic doses. As shown in the bar chart, two antibodies had TEARs > 5, 15 had TEARs > 4, 23 had TEARs = 3 and 4, and 17 had TEARs = 2 and 3, indicating that factors other than CL, F and KD affect therapeutic dose selection. Each dot represents the TEAR of an antibody in mean ± standard deviation [70]. The antibodies are numbered in alphabetical order and are shown on the x-axis. F, bioavailability; CL, systemic clearance; τ, dosing interval; Ctarget, antibody concentration at the site of action.

Effect of target anatomical locations on therapeutic doses

Antibodies typically have poor tissue penetration ability owing to their large molecular sizes (145 kDa) and high polarity [18]; thus, antibodies whose targets are outside the vascular space or the lymphoid system are expected to have relatively higher therapeutic doses to achieve sufficient exposure at their action sites. The gradient of antibody distribution from the blood into the tissue interstitial space is sharp, with an interstitial–plasma concentration ratio of around 5–15%, and the antibody distribution into the brain is even lower, with a ratio of about 0.1–0.5% [27]. Compared to normal tissues, the antibody distribution in pathological tissues such as tumors could be different owing to alterations in the tissue physiological conditions such as vascular structure and leakiness. Many studies have suggested that the antibody distribution into solid tumors is extremely low, and relatively high doses are required to achieve therapeutic exposure when the distribution is limited in the target tissues [28–30].

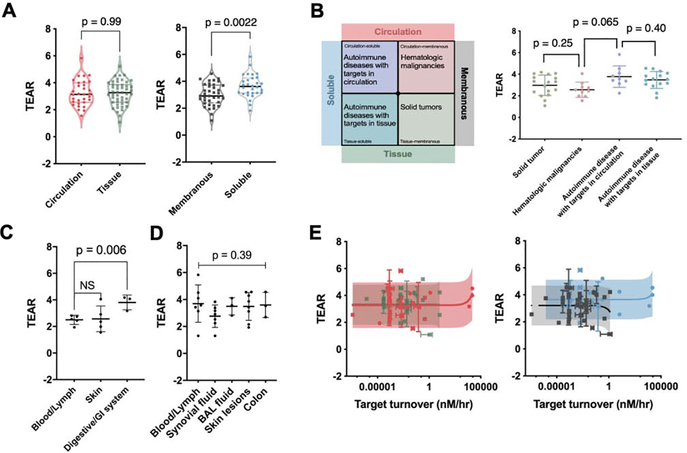

To determine the effect of the target anatomical location on antibody therapeutic doses, we sorted antibodies into two groups on the basis of whether their target anatomical locations were in the circulation or in distal tissues. The criteria for categorization are described in the supplementary material online. Conceptually, antibodies whose targets are in distal tissues are expected to have higher therapeutic doses and greater TEARs than those with circulating targets. We compared the TEARs of the two groups; intriguingly, they were not statistically different (p = 0.99, unpaired Student’s t-test, Figure 3a). This observation was contrary to the traditional perception of the strong influence of antibody distribution on therapeutic dose selection.

Figure 3.

Effects of target anatomical locations, forms and turnovers on therapeutic doses. (a) Target anatomical location does not have a significant impact on antibody therapeutic dose, whereas target cellular location might be associated with therapeutic dose selection. Although there was no significant difference between the TEARs of the circulation and tissue groups (p = 0.99, unpaired Student’s t-test), the TEARs of the soluble and membranous groups were significantly different (p = 0.0022, unpaired Student’s t-test). Each dot represents the mean TEAR of an antibody. The bars represent the median and quartiles. (b) The antibody TEARs are different between certain disease-target scenarios. As shown above, the antibodies were categorized into four disease-target scenarios. The major diseases in each scenario are autoimmune diseases with targets in the circulation (circulation-soluble), hematologic malignancies (circulation-membranous), tissues (tissue-soluble) and solid tumors (tissue-membranous). A significant difference was observed only between the hematologic-malignancies and tissue-target groups (p = 0.0065, unpaired Student’s t-test). No difference in TEAR was observed between the other groups. (c) TEARs are different between tumor anatomical sites. The anticancer antibodies targeting the blood and lymph system had significantly lower TEARs than those targeting the GI system (p = 0.006, unpaired Student’s t-test) but have no substantial difference from the ones targeting skin (p = 0.88, unpaired Student’s t-test). (d) The pathologic locations of autoimmune diseases have no significant impact on antibody TEARs. The TEARs were not significantly different between the target anatomical locations in autoimmune diseases (p = 0.39, ordinary one-way ANOVA). In (b)–(d), each dot represents the TEAR of an antibody. All the data are represented as mean ± SD. (e) Target turnover is not relevant to antibody therapeutic dose. Target turnover was found not to be a significant factor affecting the therapeutic doses in the circulation, tissue, membranous and soluble groups (p = 0.22, 0.98, 0.48 and 0.47, respectively; Pearson’s correlation). The horizontal bars represent the SD in the target turnover rates, the vertical bars represent the SD in the TEARs, and the shadows represent the 90% prediction intervals.

The antibodies were further divided into two groups on the basis of whether their cellular targets were membranous or soluble. We found that the TEARs of the antibodies with soluble targets were notably higher than the TEARs of antibodies with membranous targets (3.7 versus 3.0, p = 0.0022, unpaired Student’s t-test, Figure 3a). This observation suggests that higher therapeutic doses are generally required to effectively suppress soluble targets compared with membranous targets. The different TEARs associated with certain target cellular locations are correlated with another factor: MoAs. This is analyzed and discussed in the MoA section.

To further explore the impact of the target location on therapeutic doses, we cross-examined the TEARs in four disease-target scenarios: the circulation-soluble, circulation-membranous, tissue-soluble and tissue-membranous scenarios. As shown in Figure 3b, the prevalent diseases in each scenario were autoimmune diseases with targets in the circulatory system (circulation-soluble), hematologic malignancies (circulation-membranous), autoimmune diseases with tissue targets (tissue-soluble) and solid tumors (tissue-membranous). Notably, the TEARs were significantly lower for the antibodies in the circulation-membranous group than in the circulation-soluble group (p = 0.0065, unpaired Student’s t-test, Figure 3b). The fact that the TEARs of the two groups were different could be associated with differing MoAs. In the circulation-soluble group were antibodies with targets such as B-cell-activating factor (BAFF), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IFNγ, IL-5, immunoglobulin E (IgE), IL-6 and IL-6R. These antibodies elicit treatment effects by neutralizing soluble ligands. In the circulation-membranous group were antibodies with targets primarily expressed in the circulating cells, such as PD-1, CD38, SLAM family member 7 (SLAMF7) and CD20, mostly relating to immune dysfunction. No significant difference was detected between any other two groups.

We further explored the target anatomical sites by disease type, as described in the supplementary material online. We found that the anticancer antibodies targeting the blood and lymph system have significantly lower TEARs than those targeting the gastrointestinal (GI) system (p = 0.006, unpaired Student’s t-test, Figure 3c), but have no substantial difference with the ones targeting the skin. One possible explanation for these observations is the similar MoAs between the antibodies in the blood and lymph system and the skin groups and the different MoA of the antibodies in the GI system group. The antibodies in the blood and lymph system and the skin groups elicit treatment effects via systemic effects by recruiting immune cells from the periphery towards the induction sites. The antibodies in the GI system group (ramucirumab, panitumumab and bevacizumab) mainly block the pathogenic receptor–ligand interactions. A similar analysis of antibodies in the treatment of autoimmune diseases suggested that the TEARs were not significantly different across the anatomical sites (p = 0.39, unpaired Student’s t-test, Figure 3d). Notably, the analyzed antibodies for autoimmune diseases have the same MoA (neutralizing soluble ligands). These observations suggest that compared with the disease type and target anatomical location, antibody MoAs might have a more significant role in antibody dose selection.

Therapeutic doses for antibodies with systemic effects

For antibodies with systemic effects, the primary target locations can have a reduced influence on the therapeutic doses. For example, for antibodies treating metastatic malignancies, the therapeutic effect should go beyond the primary tumor sites and reach the metastatic lesions [31–34]. Therefore, the antibody distributions into the primary tumor sites might become less important to the overall response and the required doses for therapy. One recent trial showed that patients whose metastases at multiple anatomical sites responded to a similar degree to pembrolizumab are likely to have a better survival benefit, even though these anatomical sites could have different degrees of antibody distribution [33,35,36].

The dose–response relationships for pembrolizumab and several other checkpoint inhibitors are quite flat and sometimes obscure, partly owing to the heterogeneity in metastatic sites and lesions [37–39]. One recent study suggested that the relatively flat dose–response curve for pembrolizumab in the dose range of 2–10 mg/kg was confounded by various factors owing to the intricate interplay of patient demographic, disease status, antibody exposure and treatment response [40]. Interestingly, the poor responders to checkpoint inhibitors often have distinct degrees of response across metastatic lesions. One theory for this is that systemic activation of the immune function is required in the responding patients. The systemic immune activation is closely related to antibody exposure in the secondary lymphoid tissues, and is less dependent on antibody penetrations to either the primary tumor sites or the metastases [41–43]. This theory is reinforced by the observation that the antitumor immunity newly recruited from the periphery rather than the locally reinvigorated immunity had greater contributions to the response to the checkpoint blockades [41–43]. Several studies observed high recruitments of peripherally activated immunity in the responding lesions [44–47]. The ‘systemic effect’ of checkpoint inhibitors is recapped by the responding lesions in the brain, which antibodies almost cannot penetrate [27,47]. Thus, the therapeutic doses of antibodies with systemic effects will be less dependent on the extent of such antibodies’ distribution into the primary target sites, confirming our finding that there is no correlation between the target anatomical location and the therapeutic dose (Figure 3c). The flat dose–response curves for many immunotherapies suggest a low threshold of dose and exposure for systemic activation of the immune function [22,23,25,48].

Effect of target turnovers on therapeutic doses

Previous theoretical studies have broadly evaluated the factors that might influence antibody therapeutic doses. These theoretical analyses were primarily based on the target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD) modeling framework [49]. Antibody doses expected for therapy were simulated using the TMDD model with sufficient target engagement. A theoretical study suggested that target baselines and turnovers significantly influence the effective doses of antibodies [50]. Target anatomical locations, antibody MoAs and many other pharmacologically relevant factors have not been considered in such analyses [50,51].

We evaluated the impacts of target baseline levels and target turnovers on dose selection. We calculated the turnovers of the targets for each approved antibody. The calculation of the target turnovers is shown in Box 2, which involved multiplying the target baseline (target plasma or equivalent plasma concentrations) by the degradation rate. The turnovers reflect the total target replenishing amount per hour. A total of 56 antibodies and the turnovers of their respective targets are summarized in the supplementary material online. Unexpectedly, no significant correlation was detected between the TEARs and the target turnovers (p = 0.23, Pearson’s correlation). We also did not observe a clear correlation between the TEARs and the target turnovers in any subgroup: that is, the circulation, tissue, membranous and soluble subgroups (Figure 3e). These observations were contrary to the theoretical predictions, suggesting that the influence of the target turnovers on therapeutic doses is probably not as significant as is generally thought. We also did not observe a significant correlation between the TEARs and the target baselines (Figure S2 in the supplementary material online).

Box 2. Target turnover rates.

We defined the target turnover rate as the total amount of targets produced by the system per hour. The target turnover rate is calculated by multiplying the target baseline concentration (nM) with the target first-order degradation rate (h−1), as shown in the equation below.

| [IV] |

Specifically, for a soluble target, the plasma baseline was directly adopted, and the degradation rate was derived based on the reported plasma half-life. For a membranous target, the degradation rate was set to the antibody-complex endocytosis rate, and the target baseline was converted into an equivalent plasma concentration.

| [V] |

RN is the receptor number/cell. CN is the cell number per 1 μL blood or 1 μg tissue. For tumors, 1 μg is close to 109 tumor cells [63]. Vp represents the plasma volume (2.6 L) [27]. The target turnover rate reflects the total turnover rate of the target in the system, which enables direct comparisons across target types and locations. A summary of all the target turnovers is provided in Table S2 in the supplementary material online.

Furthermore, we examined the antibodies with extremely high or low target turnovers. A few antibodies with high target turnovers seem to have high TEARs, such as eculizumab. The target of eculizumab [complement component 5 (C5)] has the highest target turnover (15,385 nM· h−1) among all the analyzed targets. Eculizumab has a TEAR as high as 4.52, which is higher than the TEARs of 90% of the analyzed antibodies, implying that the high dose of eculizumab might be related to the high turnover of its target C5. The target of risankizumab (IL-23) has a much lower turnover (0.00193 nM· h−1) than C5, but risankizumab was labeled with an even higher therapeutic dose, resulting in the TEAR of risankizumab being as high as that of eculizumab (4.55 versus 4.52). Another striking case is erenumab, an antibody targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor (CGRPR). CGRPR was found to have one of the slowest turnovers (3.9∙10−5 nM· h−1), but erenumab has a 3.78 TEAR, higher than those of 70% of the surveyed antibodies. Overall, although the target turnovers probably influence the therapeutic doses of some antibodies, their general relevancy to therapeutic doses warrants further investigation.

Therapeutic doses for antibodies with different modes of action

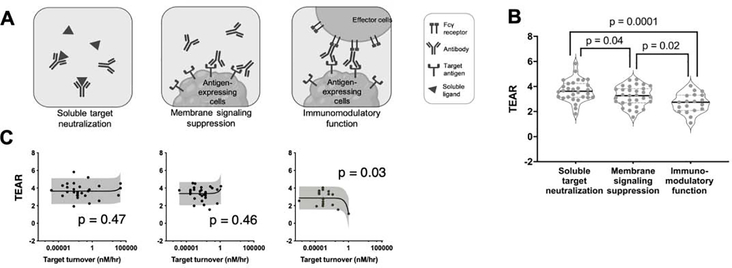

In general, therapeutic antibodies elicit pharmacological effects via three distinct MoAs (Figure 4a): target neutralization (soluble targets), intracellular signaling suppression (membranous targets) and immunomodulation (interaction with the immune system). The schematic of these three types of MoA is shown in Figure 4a. Antibodies can activate the immune function via the Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) on the effector cells through their Fc domains upon antibody–target binding. Antibodies can trigger natural killer cells to secrete various proteins for lysing the target cells [antibody-dependent cellular toxicity (ADCC)], or through macrophages for inducing phagocytosis [antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP)]. Antibody Fc domains can also recruit C1q, triggering complement cascade and exerting complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

The MoA is a pivotal factor in discerning therapeutic doses. (a) Antibodies elicit therapeutic efficacy via three distinct mechanisms: soluble target neutralizing, membranous signaling suppression and immunomodulatory function. (b) The TEARs are significantly different between antibodies with varying mechanisms of action. The antibodies in the immunomodulatory-function group had the lowest TEARs (mean TEAR = 2.7), whereas the antibodies that act through soluble-target-neutralization seem to have the highest therapeutic doses (mean TEAR = 3.7). The antibodies in the signaling-suppression group had significantly lower TEARs compared with the ones in the soluble-target-neutralization group (3.2 versus 3.7, p = 0.04, unpaired Student’s t-test). The TEARs in the signaling-suppression and soluble-target-neutralization groups were significantly higher than those in the immunomodulatory-function group (p = 0.02, P = 0.0001, unpaired Student’s t-test). Each dot represents the TEAR of an antibody. All the data are represented as mean ± SD. (c) The target turnover rates were correlated with the TEARs of the antibodies with an immunomodulatory function (p = 0.03, respectively; Pearson’s correlation), but not with the TEARs of the antibodies that neutralize soluble targets or suppress membrane signaling (p = 0.47 and 0.46, respectively; Pearson’s correlation). The horizontal bars represent the SD in the target turnover rates, the vertical bars represent the SD in the TEARs, and the gray shadows represent the 90% prediction intervals.

We compared the TEARs of antibodies with different MoAs. The antibodies that suppress membranous signaling had significantly lower TEARs than the ones that neutralize targets (p = 0.02, unpaired Student’s t-test, Figure 4b). For antibodies targeting distinct components of the same pathway (receptor versus ligand), antibodies suppressing the transmembrane receptor generally have lower TEARs than those neutralizing the ligands. For instance, the anti-IL-5R antibody benralizumab had a lower TEAR than the anti-IL-5 antibodies mepolizumab and reslizumab (2.8 versus 4.1 and 3.7). This trend also holds for anti-IL-17/17R antibodies, where brodalumab has a much lower TEAR than ixekizumab and secukinumab (2.1 versus 3.3 and 3.1). The antibodies in both the signaling-suppression and target-neutralization groups had significantly higher TEARs than the antibodies in the immunomodulatory-function group (p = 0.0001, p = 0.02, unpaired Student’s t-test, Figure 4b). The low TEARs of the antibodies working via the effector function might suggest that a relatively low target engagement is required for activating the immune function [16,23,25]. Among the five antibodies with TEARs < 2, four act via the immune function. For instance, the anti-GD2 antibody dinutuximab, which binds to the neuroblastoma cell surface GD2 and induces cell lysis via the effector function, had the lowest TEAR among the 60 surveyed antibodies (TEAR = 1.09).

We also observed TEAR differences between antibodies targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), but through different MoAs. Panitumumab mainly eradicates tumor cells by suppressing intracellular signaling, whereas necitumumab and cetuximab elicit tumor-killing effects through both the effector function and signaling suppression [52]. Cetuximab and necitumumab, two antibodies acting through multiple cellular immune responses, have much lower TEARs than panitumumab, an antibody with limited involvement of cellular effector functions (3.3 and 3.6 versus 4.1). Conversely, the anti-CD20 antibodies obinutuzumab, ofatumumab and rituximab, all of which elicit strong ADCC in treating chronic lymphoid leukemia, had close TEARs (2.8, 2.7 and 2.5). The significantly different TEARs of the antibodies in the circulation-membranous and circulation-soluble groups (Figure 3b) are also related to their distinct MoAs. In the circulation-membranous group, most antibodies elicit an effect via signaling suppression and the immunomodulatory function, whereas the antibodies in the circulation-soluble group primarily work by neutralizing soluble targets.

Interestingly, in the immunomodulatory-function group, the TEARs of antibodies with higher target turnovers were smaller (p = 0.03, Pearson’s correlation, Figure 4c). This is probably associated with the rate of endocytosis of the antibody–target complex and its persistence time on cell surfaces, which are both crucial for the effector function [53,54].

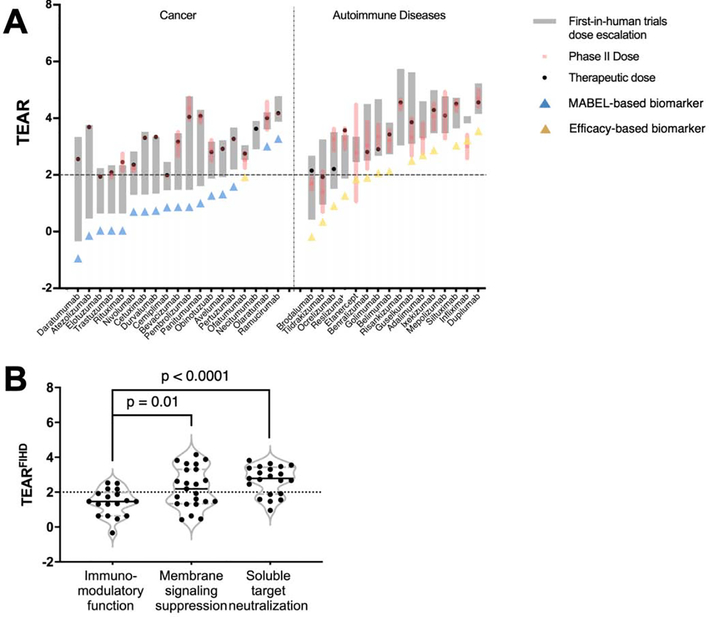

First-in-human doses and dose escalation

The doses that are tested during antibody development include FIH doses (FIHDs), maximum administered doses (MADs) in FIH trials and phase II doses (P2Ds). We analyzed these dose metrics and evaluated the potential factors involved in FIHD and P2D selection. Similarly, to enable comparisons across antibodies, we derived three metrics: TEARFIHD, TEARMAD and TEARP2D (Box 1). Among the 48 antibodies analyzed, we found high variabilities in the FIHDs and in the dose escalation ranges in the FIH trials. The lowest TEARFIHD was 10,000-fold lower than the highest. With regard to the dose escalation ranges of the FIH trials, whereas the MADs were only two times higher than the FIHDs for some antibodies, other antibodies had up to 10,000-fold dose escalation ranges in their FIH trials.

We further explored the FIHDs, dose escalations in phase I and the selections of P2Ds in the antibodies treating cancer and autoimmune diseases. As shown in Figure 5a, 16 of the 19 anticancer antibodies (84%) had relatively conservative FIHDs (TEARFIHD values < 2), whereas the analyzed antibodies for treating autoimmune diseases had relatively higher TEARFIHD values. The substantial difference in FIHDs between the two groups might result from the immunomodulatory functions of anticancer antibodies. The majority of antibodies in the cancer group have effector functions, in contrast to antibodies in the autoimmune disease group. In fact, therapeutic antibodies acting through the effector function (i.e., the immunomodulatory-function group) had relatively low and conservative FIHDs compared with the ones suppressing signaling or the ones neutralizing soluble targets (1.5 versus 2.3, p = 0.01; 1.5 versus 2.7, p < 0.0001; unpaired Student’s t-test; Figure 5b). This observation corresponds to a recent FDA report showing that more than half of the immunomodulatory antibodies as investigational new drugs were far from saturating their targets at the FIHDs [10]. The conservative FIHD selection for the immunomodulatory antibodies was driven by the specific FIHD selection guidance from the FDA [55], suggesting MABEL as the approach for selecting the starting doses of biologics with immune agonistic properties [14,56]. The antibodies with the highest TEARFIHD in the cancer groups, olaratumab and ramucirumab, mainly act by blocking the pathogenic receptor through ligand interaction rather than by effector functions.

Figure 5.

MoA has an impact on antibodies’ FIHD escalations. (a) The dose-escalating ranges in the FIH trials are denoted by gray bars, whose lower and upper edges represent the FIHDs and MADs in the FIH trials, respectively. The TEARs of the P2Ds (TEARP2D) are given in mean ± SD and are represented by red bars and shadows. The solid black circles pertain to the TEARs of the therapeutic doses. The blue and yellow triangle symbols denote the antibodies that used MABEL approaches or treatment efficacy as the P2D selection rationale. Forty antibodies were included in the analysis and were grouped by their MoAs. The names of the tested antibodies are indicated on the x-axis. (b) The TEARFIH values were significantly different between antibodies with varying MoAs. The TEARFIH values in the signaling-suppression and soluble-target-neutralization groups were significantly higher than those in the immunomodulatory-function group (p = 0.01, P < 0.0001, unpaired Student’s t-test). Each dot represents the mean TEARFIH value of an antibody. All the data are represented as mean ± SD.

We also investigated the impact of target properties in FIHD selection. The antibodies with soluble targets (the neutralizing group) had much higher TEARFIHD values than the membranous target group (p = 0.002, Figure S3a in the supplementary material online). Other target properties, including the target locations, baselines and degradation rates, were not found to have a significant impact on FIHD selection (Figure S3a–c in the supplementary material online). Notably, for antibodies with the effector function, the target turnovers did not play a significant part in their FIHDs (Figure S3c in the supplementary material online). The TEARFIHD values were slightly lower in the first-in-class antibodies than in the next-in-class antibodies, but the difference was not statistically significant (2.1 versus 2.4, p = 0.33, Figure S3d in the supplementary material online).

The P2D selection and the resultant TEARP2D also differed between the two disease groups. About half of the analyzed anticancer antibodies had one dose tested in phase II trials. All the antibodies in the autoimmune disease group had multiple doses tested and even underwent additional rounds of dose escalation in phase II trials (Figure 5a). These observations are probably associated with the enrollment barriers for the antibodies for cancer treatment [57], in which low and non-effective doses are not ethically acceptable, limiting the dose ranges being tested [58]. For antibodies treating autoimmune disease, finding the optimal dose–response relationships with the optimal efficacy and safety profiles is crucial.

Although the efficient dose escalation in FIH trials and appropriate P2D selection is associated with success in late-stage clinical trials of antibodies, there is no guidance for selecting a P2D from FIH trials. We surveyed the P2D selection rationales in 49 surveyed antibodies. Although toxicity-guided P2D selection was not observed, two types of P2D selection biomarkers were frequently applied to the surveyed antibodies: MABEL-based and efficacy-based biomarkers (see the supplementary material online). P2D selection rationales were significantly different in anticancer antibodies and anti-autoimmune-disease antibodies (Figure 5a). Seventeen out of 19 anticancer antibodies (90%) adopted the MABEL approach for P2D selection. Conversely, efficacy-related biomarkers were frequently used to select P2Ds for antibodies treating autoimmune diseases. Another interesting finding was that the therapeutic doses of anticancer antibodies were close to the maximum administered doses in FIH trials, which might result from the flat dose–response relationships that were frequently observed in immunomodulatory antibodies.

Concluding remarks

Selecting the appropriate dose for a given indication is crucial for developing a therapeutic antibody, especially at the first clinical stage and in the following efficacy confirmation and optimization trials. The decision-making in antibody dose selection is a multifactorial process, and many factors contribute to the variance of doses. The factors that influence the effective doses beyond antibody PK and its target affinity remain ambiguous.

Here, we developed a dimensionless metric, TEAR, and used it to revisit the factors that could influence therapeutic doses and dose selection. While showing some similarities with the widely used metric Dose/ED50 in analyzing dose–response profiles [59–61], TEAR, by taking out factors with relatively high certainty such as clearance and bioavailability, supports the analysis of other potential factors, including target abundance, turnovers, anatomical locations and MoAs (Figure 1).

Our analyses have provided insights into the factors that affect therapeutic doses, as well as the factors that are crucial for antibody pharmacological actions. Our review highlights the importance of MoAs and challenges the traditional perception of the importance of target turnovers and anatomical locations in selecting therapeutic doses, yielding substantial implications for the future development of therapeutic antibodies. We failed to find a significant influence of target abundance on antibody doses, challenging our traditional perceptions, and we should be cautious in interpreting the theoretical modeling result [50]. Although the current analyses suggest that a further understanding of the immunomodulatory function in the exposure–response relationship could help to optimize antibody efficacy, a closer examination is warranted in a variety of antibody development cases not included in the current study.

Note that our analyses have a few limitations. First, we applied KD values measured under in vitro conditions to derive the TEARs. Even though we considered the average of multiple measurements, there was sometimes a gap between the in vitro and in vivo binding conditions. Many physiological factors (e.g., tumor stroma) physically shape an antibody’s interactions with its targets [62]. Second, the baseline and turnovers for the targets in solid tumors were calculated with the assumption that only 109 tumor cells were present [63]. The number of tumor cells varies widely across cancer patients at different stages of diagnosis. Third, the time-varying antibody PK and antidrug antibodies were not considered in the analyses. Many studies have shown that antidrug antibody incidences, frequently reported in treating autoimmune diseases [64], can substantially alter antibody clearance. Dose adjustments are often needed in patient populations with high titers of antidrug antibodies. Furthermore, altered catabolic states of patients can change antibody clearances and affect dose–response relationships [64,65]. For example, it has been suggested that cancer cachexia in late-stage melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer patients was correlated with rapid catabolism and poorer overall survival in pembrolizumab treatment [66,67]. Fourth, the novel antibody formats, including antibody–drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies and antibody fragments, were not included in the analysis owing to their distinct PK and pharmacodynamics properties, making it challenging to derive, compare or rationalize their TEARs. Lastly, we only analyzed several pharmacologically relevant factors. Decisions regarding antibody doses are often made after considering many practical and financial factors, such as ethical restrictions, cost-effectiveness, patient compliance, and the standard of care. The roles of those factors on antibody dose selection have been summarized elsewhere [68,69].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We revisited and dissected the factors that might affect the therapeutic doses of 60 approved antibodies using the dimensionless metric TEAR (therapeutic exposure affinity ratio).

We found that contrary to the traditional perceptions and the results of many pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses, the target replenishing rates and anatomical locations do not significantly affect the antibodies’ therapeutic doses.

Antibodies’ modes of action are crucial but often overlooked factors affecting the therapeutic doses of antibodies, and they also shape the dose selection steps at the clinical development stages.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carter PJ and Lazar GA (2018) Next generation antibody drugs: pursuit of the ‘high-hanging fruit’. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 17, 197–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mould DR and Meibohm B (2016) Drug development of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. BioDrugs 30, 275–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao X et al. (2020) Model-based evaluation of the efficacy and safety of nivolumab once every 4 weeks across multiple tumor types. Ann. Oncol 31, 302–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chimalakonda AP et al. (2013) Factors influencing magnitude and duration of target inhibition following antibody therapy: implications in drug discovery and development. AAPS J. 15, 717–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davda JP and Hansen RJ (2010) Properties of a general PK/PD model of antibody-ligand interactions for therapeutic antibodies that bind to soluble endogenous targets. MAbs 2, 576–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao Y et al. (2013) Second-generation minimal physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model for monoclonal antibodies. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn 40, 597–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Y and Jusko WJ (2014) Incorporating target-mediated drug disposition in a minimal physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model for monoclonal antibodies. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn 41, 375–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed S et al. (2019) Guiding dose selection of monoclonal antibodies using a new parameter (AFTIR) for characterizing ligand binding systems. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn 46, 287–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein AM and Ramakrishna R (2017) AFIR: a dimensionless potency metric for characterizing the activity of monoclonal antibodies. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol 6, 258–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tosi D et al. (2015) Clinical development strategies and outcomes in first-in-human trials of monoclonal antibodies. J. Clin. Oncol 33, 2158–2165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viala M et al. (2018) Strategies for clinical development of monoclonal antibodies beyond first-in-human trials: tested doses and rationale for dose selection. Br. J. Cancer 118, 679–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachs JR et al. (2016) Optimal dosing for targeted therapies in oncology: drug development cases leading by example. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 1318–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oflazoglu E and Audoly LP (2010) Evolution of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapeutics in oncology. MAbs 2, 14–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller PY and Brennan FR (2009) Safety assessment and dose selection for first-in-human clinical trials with immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 85, 247–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller PY et al. (2009) The minimum anticipated biological effect level (MABEL) for selection of first human dose in clinical trials with monoclonal antibodies. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 20, 722–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saber H et al. (2016) An FDA oncology analysis of immune activating products and first-in-human dose selection. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 81, 448–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal S et al. (2016) Nivolumab dose selection: challenges, opportunities, and lessons learned for cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 4, 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lobo ED et al. (2004) Antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J. Pharm. Sci. 93, 2645–2668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.FDA (2015) 761035Orig1s000: Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review(s), FDA [Google Scholar]

- 20.FDA (2015) 761036Orig1s000: Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review(s), FDA [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lokhorst HM et al. (2015) Targeting CD38 with daratumumab monotherapy in multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med 373, 1207–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patnaik A et al. (2015) Phase I study of pembrolizumab (MK-3475; Anti-PD-1 Monoclonal Antibody) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res 21, 4286–4293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heery CR et al. (2017) Avelumab for metastatic or locally advanced previously treated solid tumours (JAVELIN Solid Tumor): a phase 1a, multicohort, dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 18, 587–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herbst RS et al. (2014) Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 515, 563–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Topalian SL et al. (2012) Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 366, 2443–2454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang M et al. (2016) Receptor occupancy assessment by flow cytometry as a pharmacodynamic biomarker in biopharmaceutical development. Cytometry B Clin. Cytom 90, 117–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao Y and Jusko WJ (2014) Survey of monoclonal antibody disposition in man utilizing a minimal physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn 41, 571–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thurber GM et al. (2008) Antibody tumor penetration: transport opposed by systemic and antigen-mediated clearance. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 60, 1421–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bensch F et al. (2017) (89)Zr-Lumretuzumab PET imaging before and during HER3 antibody lumretuzumab treatment in patients with solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 6128–6137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freeman DJ et al. (2012) Tumor penetration and epidermal growth factor receptor saturation by panitumumab correlate with antitumor activity in a preclinical model of human cancer. Mol. Cancer 11, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mistry HB et al. (2019) Resistance models to EGFR inhibition and chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer via analysis of tumour size dynamics. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol 84, 51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Claret L et al. (2018) Comparison of tumor size assessments in tumor growth inhibition-overall survival models with second-line colorectal cancer data from the VELOUR study. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol 82, 49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osorio JC et al. (2019) Lesion-level response dynamics to programmed cell death protein (PD-1) blockade. J. Clin. Oncol 37, 3546–3555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bilen MA et al. (2019) Sites of metastasis and association with clinical outcome in advanced stage cancer patients treated with immunotherapy. BMC Cancer 19, 857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dijkers EC et al. (2010) Biodistribution of 89Zr-trastuzumab and PET imaging of HER2-positive lesions in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 87, 586–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan C et al. (2019) Deep learning reveals cancer metastasis and therapeutic antibody targeting in the entire body. Cell 179, 1661–1676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pardoll DM (2012) The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 252–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribas A et al. (2016) Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA 315, 1600–1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schadendorf D et al. (2015) Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol 33, 1889–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dai HI et al. (2020) Characterizing exposure-response relationship for therapeutic monoclonal antibodies in immuno-oncology and beyond: challenges, perspectives, and prospects. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 108, 1156–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fransen MF et al. (2013) Local targets for immune therapy to cancer: tumor draining lymph nodes and tumor microenvironment. Int. J. Cancer 132, 1971–1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fransen MF et al. (2018) Tumor-draining lymph nodes are pivotal in PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint therapy. JCI Insight 3, e124507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gasteiger G et al. (2016) Lymph node – an organ for T-cell activation and pathogen defense. Immunol. Rev 271, 200–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spitzer MH et al. (2017) Systemic immunity is required for effective cancer immunotherapy. Cell 168, 487–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yost KE et al. (2019) Clonal replacement of tumor-specific T cells following PD-1 blockade. Nat. Med 25, 1251–1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu C et al. (2019) Dynamic metrics-based biomarkers to predict responders to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 120, 346–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eguren-Santamaria I et al. (2020) PD-1/PD-L1 blockers in NSCLC brain metastases: challenging paradigms and clinical practice. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 4186–4197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brahmer JR et al. (2010) Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J. Clin. Oncol 28, 3167–3175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mager DE and Jusko WJ (2001) General pharmacokinetic model for drugs exhibiting target-mediated drug disposition. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn 28, 507–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agoram BM (2009) Use of pharmacokinetic/ pharmacodynamic modelling for starting dose selection in first-in-human trials of high-risk biologics. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 67, 153–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Penney M and Agoram B (2014) At the bench: the key role of PK-PD modelling in enabling the early discovery of biologic therapies. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 77, 740–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shim H (2011) One target, different effects: a comparison of distinct therapeutic antibodies against the same targets. Exp. Mol. Med 43, 539–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deans JP et al. (2002) CD20-mediated apoptosis: signalling through lipid rafts. Immunology 107, 176–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou Y et al. (2012) Impact of intrinsic affinity on functional binding and biological activity of EGFR antibodies. Mol. Cancer Ther 11, 1467–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.US Department of Health and Human Services et al. (2010) Guidance for Industry: S9 Nonclinical Evaluation for Anticancer Pharmaceuticals, FDA [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duff G (2006) Expert Scientific Group on Phase One Clinical Trials: Final Report, XXXXX

- 57.Unger JM et al. (2016) The role of clinical trial participation in cancer research: barriers, evidence, and strategies. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 35, 185–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wages NA et al. (2018) Design considerations for early-phase clinical trials of immune-oncology agents. J. Immunother. Cancer 6, 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshimasu T et al. (2015) A theoretical model for the hormetic dose-response curve for anticancer agents. Anticancer Res. 35, 5851–5855 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mandema JW et al. (2014) Time course of bone mineral density changes with denosumab compared with other drugs in postmenopausal osteoporosis: a dose-response-based meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 99, 3746–3755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blair RM et al. (2001) Threshold analysis of selected dose-response data for endocrine active chemicals. APMIS 109, 198–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tang Y and Cao Y (2020) Modeling the dynamics of antibody-target binding in living tumors. Sci. Rep 10, 16764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Del Monte U (2009) Does the cell number 109 still really fit one gram of tumor tissue? Cell Cycle 8, 505–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petitcollin A et al. (2020) Modelling of the time-varying pharmacokinetics of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies: a literature review. Clin. Pharmacokinet 59, 37–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Enrico D et al. (2020) Antidrug antibodies against immune checkpoint blockers: impairment of drug efficacy or indication of immune activation? Clin. Cancer Res 26, 787–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li H et al. (2017) Time dependent pharmacokinetics of pembrolizumab in patients with solid tumor and its correlation with best overall response. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn 44, 403–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Turner DC et al. (2018) Pembrolizumab exposure-response assessments challenged by association of cancer cachexia and catabolic clearance. Clin. Cancer Res 24, 5841–5849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garrison LP Jr (2016) Cost-effectiveness and clinical practice guidelines: have we reached a tipping point? An overview. Value Health 19, 512–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lange A et al. (2014) A systematic review of cost-effectiveness of monoclonal antibodies for metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 50, 40–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Efremova M et al. (2018) Targeting immune checkpoints potentiates immunoediting and changes the dynamics of tumor evolution. Nat. Commun 9, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.