Abstract

Background & Aims

In an attempt to uncover unmet patient needs, this review aims to synthesise quantitative and qualitative studies on patients’ quality of life and their experience of having liver disease.

Methods

Three databases (CINAHL, Embase, and PubMed) were searched from January 2000 to October 2020. The methodological quality and data extraction of both quantitative and qualitative studies were screened and appraised using Joanna Briggs Institute instruments for mixed-method systematic reviews and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. A convergent, integrated approach to synthesis and integration was used. Studies including patients with autoimmune and cholestatic liver disease, chronic hepatitis B and C, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma were considered.

Results

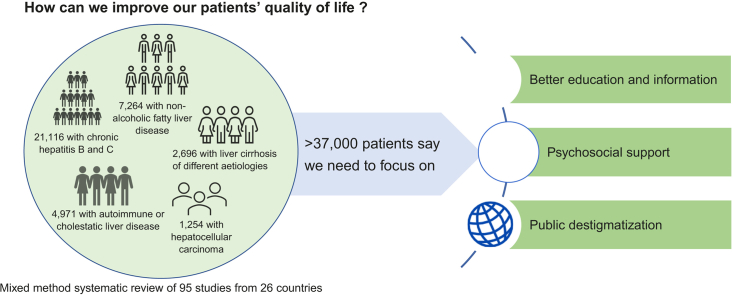

The searches produced 5,601 articles, of which 95 (79 quantitative and 16 qualitative) were included in the review. These represented studies from 26 countries and a sample of 37,283 patients. The studies showed that patients´ quality of life was reduced. Unmet needs for information and support and perceived stigmatisation severely affected patients’ quality of life.

Conclusions

Our study suggests changes to improve quality of life. According to patients, this could be achieved by providing better education and information, being aware of patients’ need for support, and raising awareness of liver disease among the general population to reduce misconceptions and stigmatisation.

Registration number

PROSPERO CRD42020173501.

Lay summary

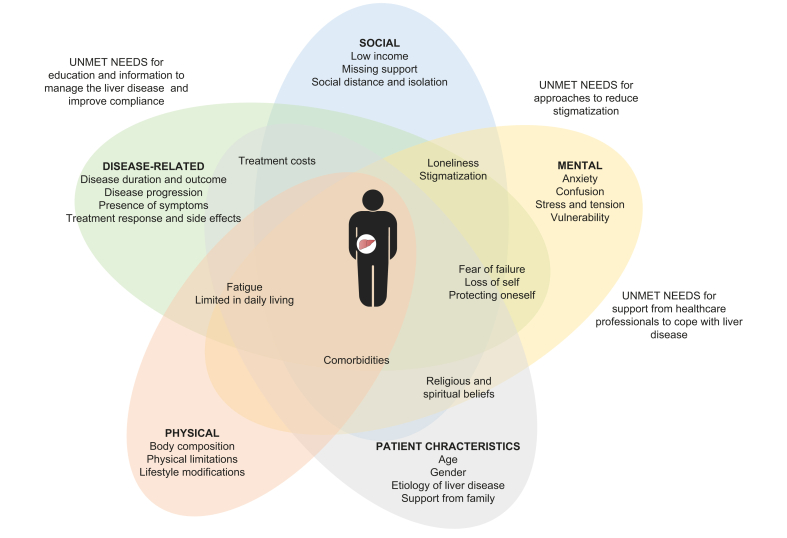

Regardless of aetiology, patients with liver diseases have impaired quality of life. This is associated with disease progression, the presence of symptoms, treatment response, and mental, physical, and social factors such as anxiety, confusion, comorbidities, and fatigue, as well as limitations in daily living, including loneliness, low income, stigmatisation, and treatment costs. Patients highlighted the need for information to understand and manage liver disease, and awareness and support from healthcare professionals to better cope with the disease. In addition, there is a need to raise awareness of liver diseases in the general population to reduce negative preconceptions and stigmatisation.

Keywords: Liver disease, Mixed method, Patient experience, Patient reported outcomes, Quality of life, Systematic review, Unmet needs

Abbreviations: CLDQ, Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life; FACT-Hep, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Hepatobiliary Carcinoma; HBQOL, Hepatitis B Quality of Life; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute; LC-PROM, Liver Cirrhosis Patient Reported Outcome Measure; LDQOL, Liver Disease Quality of Life; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; PBC, Primary Biliary Cholangitis Questionnaire; PedsQL, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory; SF, Short Form; SIP, Sickness Impact Profile; VAS, visual analogue scale; WHOQOL-BREF, WHO Quality of Life

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Patients with liver disease regardless of aetiology and severity have impaired quality of life.

-

•

Patients call for better education and information to understand and manage their liver disease, and for increased awareness and support from healthcare professionals.

-

•

Owing to the limited knowledge of liver diseases among the general population, patients experience stigmatisation, resulting in loneliness and social isolation.

-

•

Addressing unmet needs of patients with liver disease could improve their quality of life.

Introduction

Chronic liver disease is commonly caused by alcohol abuse, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), viral hepatitis, and autoimmunity and may progress to cirrhosis. Liver disease is often associated with serious health problems, hospitalisations, and increased mortality.1 Although clinical management is important for the disease course and physical symptoms, there is usually a lack of focus on the patients’ experience of the disease and quality of life, both of which are important components when assessing the overall health status of patients and planning liver care.2 An important hindrance is the lack of knowledge of liver patients’ mental and social symptoms. These are often left unspoken and go unnoticed.3 This is an unsatisfactory situation because liver disease often negatively impacts patients’ family and social life, employment and financial status, and maintenance of health insurance, all sequelae that are often unseen by healthcare professionals.4

Therefore, the aim was to develop a convergent, integrated synthesis of quantitative and qualitative studies on the perceived quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease in an attempt to reveal unmet patient needs.

Patients and methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for mixed-method systematic reviews5 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.6 A protocol was developed to outline the objective, search strategy, selection criteria, data extraction method, and data synthesis methods.7 The review was registered in PROSPERO CRD42020173501.

Search strategy

A three-step search strategy was utilised.5 First, PubMed was searched with the search terms ‘quality of life’ and ‘liver disease’, followed by an analysis of the words contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles, and of the index terms used to describe the articles. Second, all three databases [CINAHL (via EBSCO), Embase (via Ovid), and PubMed (via Ovid)] were searched using all identified keywords and index terms from the first step from January 2000 to October 2020. To refine the depth and width of the search and to capture available relevant articles, Boolean operators (OR and AND) were utilised to combine keyword and index terms such as patients with ‘autoimmune liver disease’ or ‘cirrhosis’ and outcomes such as ‘patient experience’ or ‘quality of life’. Third, the reference list of all articles selected for critical appraisal and possible inclusion was manually searched for additional studies. Articles published in English were included. The search strategy is presented in Table S1. The search strategy was established in collaboration with a librarian from the hospital’s medical library.

Study selection

Types of studies

Quantitative data from observational analytical or descriptive studies (e.g. case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, and prospective and retrospective cohort studies) and qualitative studies regardless of design and method were included.

Types of participants

Studies that included patients with autoimmune and cholestatic liver disease, chronic hepatitis B and C, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and NASH, cirrhosis of different aetiologies, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were included. There was no restriction regarding disease severity, patient age, sex, or ethnicity. Studies on the experiences and quality of life of families with patients with liver disease or healthcare professionals were not included.

Phenomena of interest

Studies with the primary aim of exploring the quality of life of patients with liver disease using either generic or liver-specific questionnaires were included. Studies comparing patients with liver disease to control groups or general population norms and studies comparing patients with different types of liver diseases or patients with liver disease to other patients with chronic disease were included. Studies exploring patients’ changes in quality of life after clinical interventions were excluded. Finally, studies exploring the experiences and quality of life of patients awaiting or receiving a liver transplant were not included in the review. Qualitative studies that described patients’ experience and perception of having a liver disease were included.

Article screening

Following the search, the articles were imported into a reference management program (Endnote X9, Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA), and duplicate citations were removed. Thereafter, the titles and abstracts of the articles identified from the searches were screened and selected articles were individually reviewed. The full text of the articles selected was obtained and assessed for eligibility. Reasons for excluding any full-text articles were recorded and are presented in Table S2.

Assessment of methodological quality

The studies were critically appraised using the standardised critical appraisal instrument for quantitative and qualitative studies from JBI SUMARI5 presented in Table S3. All studies were included in the review regardless of methodological quality. At any step of the method phase, any disagreements were resolved through a discussion between the authors or input from a research colleague until a consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Quantitative and qualitative data were extracted from the included articles using the standardised JBI data extraction instrument JBI SUMARI.5 These data included details on the authors, year of publications, study methodologies, patient populations and characteristics, including sample sizes, data collection methods, and outcomes of significance to the review objective. If possible, factors demonstrating a significant association with quality of life were extracted. A table of the data extraction is presented in Table S4.

Data synthesis

A descriptive assessment of the data based on the extracted outcomes, followed by a convergent integrated approach according to the JBI methodology for mixed-method systematic reviews, was performed.5 This involved quantitative data being presented as textual descriptions and assembled with qualitative data. The assembled data were categorised based on the similarity in their meanings in an attempt to reveal unmet patient needs and to suggest directions to meet these needs and improve quality of life.

Results

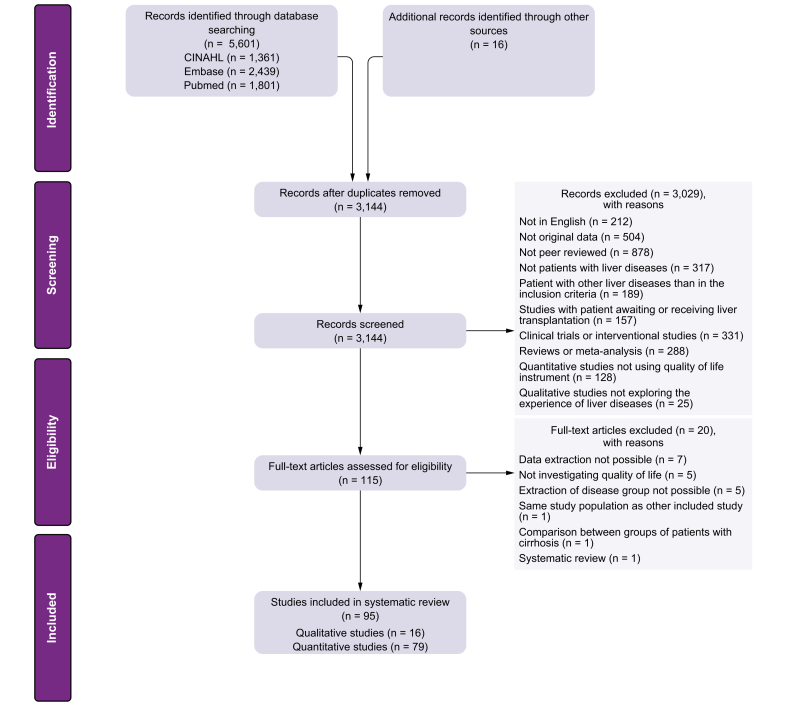

The searches produced a total of 5,601 articles. After the elimination of duplicates, 3,144 articles were reviewed based on titles and abstracts, and 115 were identified for full-text assessment. After full-text reviews, 95 articles (79 quantitative and 16 qualitative) met the inclusion criteria. A summary of the process is presented in the flowchart in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the review process.

Description of included articles

The included articles represented studies from 26 different countries across 6 continents, with the majority being from Asia (36%), Europe (32%), and North America (30%). Among the 79 quantitative studies, the majority were cross-sectional (76%). Studies had a patient population size from 15 to 7,098, and 52% of the studies used control groups or general population norms for comparison. Seventy percent of the studies used generic questionnaires on quality of life, with different versions of the Short Form (SF) being the most common (51%), whereas 47% of the studies used liver-specific questionnaires with the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ) being the most common (30%). All 16 qualitative studies used interviews as a data collection method. The most common analysis method was content analysis (38%), followed by phenomenological (31%) and thematic analysis (19%). The patient population size was between 8 and 41 patients.

Methodological quality of the included studies

A majority of the studies (92%) were categorised as having good or moderate methodological quality. The mean quality score of the quantitative studies was 7.1 (range 4–9), and the mean score for the qualitative studies was 8.2 (range 7–10). The most common source of bias was a lack of description of the patient population or control group, general characteristics, sampling method, and inadequate descriptions of statistical analysis and results.

Description of included patients

The patient population consisted of patients with autoimmune or cholestatic liver disease (19 studies),[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26] chronic hepatitis B or C (35 studies),[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61] NAFLD or NASH (15 studies),[62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76] cirrhosis of different aetiologies (but mainly alcohol and hepatitis; 17 studies),[77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93] and HCC (9 studies).[94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102] Six studies explored the quality of life in children with liver disease (3 in children with autoimmune or cholestatic liver disease,9,12,23 2 in children with NAFLD,70,71 and 1 in children with hepatitis B).52 A total of 37,283 patients participated in the included studies. Half of the studies included patients aged 50 years or older. Most studies on patients with chronic hepatitis B or C included patients under 50 years of age (71%). Fifty-five percent of the studies had a patient population with more men than women. However, in studies of patients with autoimmune or cholestatic disease, more women than men were included (83%). In all of the included studies, most of the patients were Child-Pugh class A (64%) and had a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score under 15 (56%). Most studies (89%) included patients from various gastroenterology and hepatology in- and outpatient settings, whereas the rest used data from national surveys or from patient-reported outcome databases. The characteristics of the studies and the patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies and patients (N = 95).

| Study design and method | Number of studies (%) |

|---|---|

| Quantitative studies (all using questionnaire) | 79 (83%) |

| Cross-sectional study | 60 (76%) |

| Prospective study | 14 (18%) |

| Case-control study | 5 (6%) |

| Qualitative studies (all using interview) | 16 (17%) |

| Content analysis | 6 (38%) |

| Phenomenological analysis | 5 (31%) |

| Thematic analysis | 3 (19%) |

| Grounded theory analysis | 1 (6%) |

| Combination of analyses | 1 (6%) |

| Study design divided into liver disease group | |

| Autoimmune or cholestatic liver disease | |

| Quantitative studies | 17 (18%) |

| Qualitative studies | 2 (2%) |

| Hepatitis B or C | |

| Quantitative studies | 28 (29%) |

| Qualitative studies | 7 (7%) |

| NAFLD and/or NASH | |

| Quantitative studies | 13 (14%) |

| Qualitative studies | 2 (2%) |

| Cirrhosis of different aetiology | |

| Quantitative studies | 14 (15%) |

| Qualitative studies | 3 (4%) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | |

| Quantitative studies | 7 (7%) |

| Qualitative studies | 2 (2%) |

| Quality of life questionnaire | |

| Generic questionnaires | 59 (70%) |

| Short Form (SF-6D, SF-8, SF-12, SF-36) | 40 (51%) |

| European Quality of Life (EQ-5D) | 10 (13%) |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) | 5 (6%) |

| Other | 4 (5%) |

| Liver-specific questionnaires | 37 (47%) |

| Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ) | 24 (30%) |

| Primary Biliary Cholangitis Questionnaire (PBC) | 5 (6%) |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Hepatobiliary carcinoma (FACT-Hep) | 4 (5%) |

| Other | 4 (5%) |

| Studies using more than one questionnaire to measure quality of life | 20 (25%) |

| Study characteristics | |

| Study location | |

| Asia (China, Hong Kong, India, Iran, Japan, Korea, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, Turkey) | 34 (36%) |

| Europe (Denmark, England, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Serbia, Sweden) | 30 (32%) |

| North America (Canada, USA) | 29 (30%) |

| South America (Brazil) | 3 (3%) |

| Australia/Oceania (Australia) | 3 (3%) |

| Africa (Ghana) | 1 (1%) |

| Studies from multiple countries | 4 (4%) |

| Patient population size | |

| Studies with <50 patients | 27 (28%) |

| Studies with 50–150 patients | 25 (26%) |

| Studies with >150 patients | 43 (46%) |

| Studies using control group or general population norms | 41 (52%) |

| Quality assessment | |

| Good | 33 (35%) |

| Moderate | 54 (57%) |

| Poor | 8 (8%) |

| Patient population characteristics (N = 37,283) | |

| Adults >18 years of age | 36,599 (98%) |

| Children <18 years of age | 684 (2%) |

| Patients with autoimmune or cholestatic liver disease | 4,971 (13%) |

| Patients with hepatitis B or C | 21,116 (57%) |

| Patients with NAFLD and/or NASH | 7,246 (19%) |

| Patients with cirrhosis of different aetiology | 2,696 (8%) |

| Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma | 1,254 (3%) |

| Age group (Reported in 81 studies) | |

| <50 years | 37 (46%) |

| 50–60 years | 33 (41%) |

| >60 years | 11 (13%) |

| Sex (Reported in 88 studies) | |

| <50% men | 36 (41%) |

| 50–60% men | 18 (20%) |

| >60% men | 34 (39%) |

| Disease severity (Reported in 11 and 9 studies) | |

| Child-Pugh class A > 50% | 7 (64%) |

| Child-Pugh class B or C > 50% | 4 (36%) |

| Model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) score <15 | 5 (56%) |

NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Patients’ quality of life

Patients’ quality of life was reduced compared with control groups or the general population, regardless of the liver disease aetiology. The use of questionnaires and the presentation of quality of life scores varied, which made comparison across aetiology and severity of the liver disease difficult. See Table 2 for summary of findings from the included studies. Disease progression was found to be associated with impaired quality of life.79,81,[83], [84], [85],[89], [90], [91], [92],97,99,101 Other disease-related factors such as disease duration and severity, response to treatment, and side effects of medication also negatively affect the quality of life in patients.9,12,[22], [23], [24], [25], [26] Mental, physical, and social factors, such as body composition, comorbidities, fatigue, lack of information on the disease, and low income together with patient characteristics, such as younger age at diagnosis, alcohol use, and female sex, were associated with impaired quality of life.8,10,11,15,18,21,30,33,35,[42], [43], [44],48,49,58,59,66,67,72,74

Table 2.

Summary of findings from studies included in the systematic review.

| Patients | Autoimmune or cholestatic liver disease | Chronic hepatitis B or C | NAFLD or NASH | Cirrhosis | HCC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative studies | ||||||

| Quality of life total mean scores of patients with liver diseases across the included studies | ||||||

| Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ) mean score | 5.5∗∗ | 4.1–5.8∗ | 4.9–5.6† | 4.3–5.3‡ | – | |

| European Quality of Life (EQ-5D) | Total mean score | 0.89∗∗ | 0.37–1.0† | 0.67∗∗ | – | – |

| Mean visual analogue scale (VAS) score | 80∗∗ | 57–85† | – | – | – | |

| Hepatitis B Quality of Life (HBQOL) mean score | – | 64.4–81.4# | – | – | – | |

| Short-Form (SF) different versions | Mental component summary | 40.1–66.7∗ | 43.0–51.3∗ | 39.2–49.5∗ | 41.0–45.3‡ | – |

| Physical component summary | 38.6–69.2∗ | 43.7–54.0∗ | 38.5–46.4∗ | 30.8–38.6‡ | – | |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Hepatobiliary Carcinoma (FACT-Hep) mean score | – | – | – | – | 74–126‡ | |

| Liver Cirrhosis Patient Reported Outcome Measure (LC-PROM) mean score | – | – | – | 189∗∗ | – | |

| Liver Disease Quality of Life (LDQOL) mean score | – | – | – | 55.3∗∗ | – | |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) mean score | 71.6–78.3‡ | 72.7–74.58# | – | – | ||

| Primary Biliary Cholangitis Questionnaire (PBC) mean score | 89.4∗∗ | – | – | – | – | |

| Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) mean score | – | – | – | 4.36∗∗ | – | |

| WHO Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) mean score | – | 70.8∗∗ | – | – | – | |

| Studies not reporting total mean score but sub-scores for individual quality of life domains, number and % | 6 (35%) | 6 (21%) | 2 (15%) | 3 (21%) | 2 (28%) | |

| Studies reporting quality of life results in graphic, number and % | 3 (18%) | 3 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (14%) | 1 (14%) | |

| Qualitative studies | ||||||

| Main findings from interviews | Patients felt de-legitimation of experiences. The disease resulted in an unreliable body, fatigue, planning a life to conserve energy, and struggling to maintain normality and emotional consequence. Patients missed support. | The diagnosis was a shock followed by disappointment and lack of support. Patients needed education and information to manage the disease. Patients had fear of rejection and stigma. Patients had Insufficient self-care due to limited knowledge. | Patients lacked information and knowledge on the disease. In addition, they lacked support to make lifestyle modifications. NASH had impact on patients’ social life and work performance. Patients experienced stigma. | Patients feared disease outcome and needed support to cope with the disease and treatment. They felt loneliness, loss of self and social isolation due to limits in daily living. They experienced negative preconceptions and stigma. | HCC was associated with physical symptoms and psychosocial stress. Patients’ were highly aware of changes and symptoms, but needed information and support to manage the disease. | |

Range of quality of life scores indicate minimum and maximum total mean score from studies using the questionnaire.

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Indicates the use of the questionnaire in 5–9 studies.

Indicates the use of the questionnaire in 4 studies.

Indicates the use of the questionnaire in 3 studies.

Indicates the use of the questionnaire in 2 studies.

Indicates the use of the questionnaire in 1 study.

Patients’ experience of having a liver disease

Patients had fear of the disease outcome, their physical condition, and treatment costs. They were shocked to be diagnosed with a liver disease, which triggered a life transition,29,37,55,80,88 although patients with hepatitis B also understood the disease as an intergenerational family condition.59 Patients generally tried to manage the disease in a positive way, but a lack of knowledge could result in insufficient self-care. This resulted in a feeling of failure.29,37,55,80,88

Across aetiologies, patients described being afraid to reveal having liver disease because of the fear of misperception. Patients adopted a number of strategies such as denial to protect themselves. The diagnosis of liver disease introduced a feeling of stigmatisation in all patient groups caused by attributes associated with the disease such as alcohol or drug use. This resulted in social distance and isolation, which negatively impacted patients’ social life.29,37,47,55,56,62,65,80,88

Patients with autoimmune and cholestatic liver disease described that having an invisible and rare disease resulted in family and healthcare professionals underestimating the impact of the disease. Patients described de-legitimation of their experience, lack of consideration of needs, and trivialisation of fatigue.16,18 Patients with cirrhosis felt disappointed because treatment options were limited as a result of their late diagnosis.77,80,88 They described more limitations in their daily living because of disease progression and symptoms than patients with less severe liver diseases, which resulted in a feeling of loss of self and loneliness.29,37,55,80,88 Patients with cirrhosis felt vulnerable when experiencing symptoms and had difficulties with treatment compliance.77,80,88 Some patients expressed being religious or spiritual, which gave them a sense of faith and hope.77,80 Patients with HCC were highly aware of changes and new symptoms. They described a desire to control how the disease was affecting their quality of life, which navigated treatment decisions.94,95

Patients’ unmet needs

Regardless of liver disease aetiology, all patients described that limited information and understanding of the disease created anxiety and considerable confusion.29,37,55,57,62,65,80,88 Patients expressed a need for awareness and support from healthcare professionals to cope with liver disease.29,37,55,57,62,65,80,88 In particular, patients with NAFLD or NASH admitted poor understanding of the disease. Some patients were advised to make lifestyle modifications but did not receive any information or support on how to proceed. Others were told that NAFLD should not be a concern and that comorbidities were of greater concern.62,65 Patients with HCC described that unmet information needs negatively affected their quality of life.94,95 In addition, patients experienced negative preconceptions and stigmatisation because of sparse knowledge of liver disease in the general population.29,39,56,65,80,88 Based on the findings, a conceptual model of the impact of liver disease on patients’ quality of life was developed (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Conceptual model on the impact of liver disease on patients’ quality of life.

Discussion

This systematic review sought to explore patients’ quality of life and their experience of having a chronic liver disease and to reveal unmet needs. We found that regardless of aetiology, the quality of life was impaired in patients with liver disease as a result of disease progression and several mental, physical, and social factors. Patients highlighted an unmet need for information to understand and manage their liver disease and awareness and support from healthcare professionals to better cope with their situation. In addition, negative preconceptions and stigmatisation negatively affected patients’ quality of life.

This is the first systematic review on the quality of life in patients with liver disease that uses a mixed-method approach. Mixed-method research originated in social science, but has recently expanded into health science.103 It integrates quantitative measures with qualitative analyses, which helps provide a wider and deeper understanding of the impacts of liver diseases on patients’ quality of life. The strength of this review is the systematic approach. The development of a search protocol before the review helped to reduce the impact of biases, ensure accountability and transparency, and maximise the likelihood of correct data extraction.104 The weaknesses of the review are the possibility that relevant articles were not included because of language limitations and the fact that only a limited number of databases were searched. In addition, the review does not include grey literature and may thus be subject to publication bias. The quality of the review depends on the quality of the studies included. Most studies, whether quantitative or qualitative, had moderate or good methodological quality. A common source of bias was the lack of descriptions of patients’ demographics; therefore, it is possible that the patients studied were not necessarily representative of the entire population of patients with liver disease. In addition, most studies were cross-sectional in design, so causal inference cannot be drawn from the results. Moreover, studies used in the review examined a wide range of factors associated with quality of life without a priori hypotheses; therefore, the findings might be incidental. However, given the extensive nature of this review, this error would be minimised by repeated findings in several studies, increasing the confidence in the external validity of the observed associations.

The review was successful in identifying studies from 26 different countries across 6 continents. Although our findings on patients’ quality of life are consistent across different countries, only a few studies from Africa and South America, areas where liver disease is a major health burden, were identified.105

Regardless of the aetiology of the liver disease, patients’ quality of life was impaired. The pattern of impairment may vary between different aetiologies and severity. However, the heterogeneous nature of the different questionnaires used to measure quality of life and the ways in which findings were reported made comparison challenging. This has been highlighted in other studies, which recommend the use of a robust generic questionnaire in combination with a disease-specific questionnaire to measure quality of life in patients with liver disease. In addition, it has been suggested that further studies on quality of life should incorporate a qualitative element, which would be valuable in determining the full humanistic burden of living with a liver disease.106

Our review identified an unmet need for patient information. Limited knowledge has been identified as a significant barrier to disease management.107 One practical implication is to provide written information to address patients’ information needs concerning liver disease and treatment. Such a simple educational intervention has proven to increase the patients’ knowledge.108 However, it remains to be seen whether increased patient knowledge will translate into improved quality of life. In addition, an emerging area of research in the field of improving patient knowledge is health literacy, that is, the capacity to find, understand, and act on health information. Patients with cirrhosis may have limited health literacy.109 Therefore, larger intervention studies are needed to determine which educational efforts are needed and their effect on disease management and quality of life.

The review points to a need for improved patient support. Support is linked to better disease management and outcomes in patients with chronic diseases.110 Thus, individualised support, driven by a formal assessment of patients’ needs rather than by assumptions regarding prognosis should be offered. Moreover, healthcare professionals may encourage patients to seek support in different patient associations or organisations that provide support. Studies of patients with other chronic diseases have shown that self-management programs can improve the disease and strengthen the mindset of patients.111 There is a need to assess the effectiveness of supportive care interventions to accommodate liver patients’ unmet needs and improve their quality of life.

Regardless of aetiology, patients with liver disease experience stigmatisation, which negatively affects patients’ quality of life. Stigmatisation in patients with liver disease is associated with depression, a lack of social support, and a decrease in the tendency to seek health care.112 Even among healthcare professionals, cirrhosis is considered a low-ranking disease.113 Healthcare professionals need to be aware of these perceptions and their impact on patients’ interaction with the healthcare system and should consider addressing stigmatisation when counselling patients.

In conclusion, this is the first mixed-method systematic review that summarises findings from a growing body of literature on the quality of life of patients with liver disease. Our review substantiates the general conception that, regardless of aetiology, liver disease has major impact on patients’ lives. As something new, our methodology makes way for a deeper understanding by exploring the main self-reported causes of impaired quality of life. Apart from the symptoms of liver disease, these causes include unmet needs for information, education, support from families and healthcare professionals, and calls for increased public awareness with a focus on de-stigmatisation. An increased focus on such ‘soft’ issues will likely help patients better cope with liver disease and improve their quality of life.

Financial support

L.L.G. received a grant from the Region of Southern Denmark’s Foundation for Health Research. The funder played no role in the design, collection, analysis, or writing of the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

Contributed to the study concept and design: L.L.G. Contributed to the data collection, analysis, writing, and conceptualisation of the manuscript: both authors.

Data availability statement

The dataset used in this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest. Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the advice from and review by Professor Hendrik Vilstrup, Department of Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark in connection with the development of this systematic review.

Footnotes

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100370.

Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Tsochatzis E.A., Bosch J., Burroughs A.K. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2014;838:1749–1761. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orr J.G., Homer T., Ternent L., Newton J., McNeil C.J., Hudson M., et al. Health related quality of life in people with advanced chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1158–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wainwright S.P. Transcending chronic liver disease: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 1997;6:43–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.1997.tb00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajaj J.S., Wade J.B., Gibson D.P., Heuman D.M., Thacker L.R., Sterling R.K., et al. The multi-dimensional burden of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy on patients and caregivers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1646–1653. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aromataris E., Munn Z., editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. 2017. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mother D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grønkjær L.L., Lauridsen M.M. Patients’ experience of having a liver disease and the impact on their quality of life: a mixed-method systematic review protocol. JBI Evid Synth. 2020 doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackburn P., Freeston M., Baker C.R., Jones D.E.J., Newton J.L. The role of psychological factors in the fatigue of primary biliary cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2007;27:654–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bozzini A.B., Neder L., Silva C.A., Porta G. Decreased health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with autoimmune hepatitis. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2019;95:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung A.C., Patel H., Meza-Cardona J., Cino M., Sockalingam S., Hirschfield G.M. Factors that influence health-related quality of life in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1692–1699. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-4013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyson J.K., Wilkinson N., Jopson L., Mells G., Bathgate A., Heneghan M.A., et al. The inter-relationship of symptom severity and quality of life in 2055 patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:1039–1050. doi: 10.1111/apt.13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gulati R., Radhakrishnan K.R., Hupertz V., Wyllie R., Alkhouri N., Worley S., et al. Health-related quality of life in children with autoimmune liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:444–450. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31829ef82c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janik M.K., Wunsch E., Raszeja-Wyszomirska J., Moskwa M., Kruk B., Krawczyk M., et al. Autoimmune hepatitis exerts a profound, negative effect on health-related quality of life: a prospective, single-centre study. Liver Int. 2019;39:215–221. doi: 10.1111/liv.13960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jorgensen R. A phenomenological study of fatigue in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Adv Nurs. 2006;55:689–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milovanovic T., Popovic D., Stojkovic L.M., Dumic I., Dragasevic S., Milosavljevic T. Quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Dig Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1159/000506980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montali L., Frigerio A., Riva P., Invernizzi P. It’s as if PBC didn’t exist: the illness experience of woman affected by primary biliary cirrhosis. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1429–1445. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.565876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raszeja-Wyszomirska J., Kucharshi R., Zygmunt M., Safranow K., Miazgowski T. The impact of fragility fractures on health-related quality of life in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepat Mon. 2015;15 doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.25539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raszeja-Wyszomirska J., Wunsch E., Krawczyk M., Rigopoulou E.I., Bogdanos D., Milkiewicz P. Prospective evaluation of PBC-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires in patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Liver Int. 2015;35:1764–1771. doi: 10.1111/liv.12730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raszeja-Wyszomirska J., Wunsch E., Krawczyk M., Rigopoulou E.I., Kostrzewa K., Norman G.L., et al. Assessment of health related quality of life in polish patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2016;40:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schramm C., Wahl I., Weiler-Normann C., Voigt K., Wiegard C., Glaubke C., et al. Health-related quality of life, depression, and anxiety in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2014;60:618–624. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sogolow E.D., Lasker J.N., Short L.M. Fatigue as a major predictor of quality of life in woman with autoimmune liver disease. Women’s Health Issue. 2008;18:336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi A., Moriya K., Ohira H., Arinaga-Hino T., Zeniya M., Torimura T., et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with autoimmune hepatitis: a questionnaire study. PloS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trevizoli I.C., Pinedo C.S., Teles V.O., Seixas R.B.P.M., Carvalho E. Autoimmune hepatitis in children and adolescents: effect on quality of life. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:861–865. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Untas A., Booujut E., Corpechot C., Zenasni F., Chazouilleres O., Jaury P., et al. Quality of life and illness perception in primary biliary cirrhosis: a controlled cross-sectional study. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2015;39:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong L.L., Fisher H.F., Stocken D.D., Rice S., Khanna A., Heneghan M.A., et al. The impact of autoimmune hepatitis and its treatment on health utility. Hepatology. 2018;68:1487–1497. doi: 10.1002/hep.30031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yagi M., Tanaka A., Abe M., Namisaki T., Yoshiji H., Takahashi A., et al. Symptoms and health-related quality of life in Japanese patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Sci Rep. 2018;12542:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31063-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdo A.A. Health-related quality of life of Saudi hepatitis B and C patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:397–403. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2012.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abedi G., Rostami F., Nadi A. Analyzing the dimensions of the quality of life in hepatitis B patients using confirmatory factor analysis. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7:22–31. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v7n7p22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adjei C.A., Naab F., Donkor E.S. Beyond the diagnosis: a qualitative exploration of the experiences of persons with hepatitis B in the Accra Metropolis, Ghana. BMJ Open. 2017:7. doi: 10.1136/mbjopen-2017-017665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Björnsson E., Verbaan H., Oksanen A., Fryden A., Johansson J., Friberg S., et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with different stages of liver disease induced by hepatitis C. Scan J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:878–887. doi: 10.1080/00365520902898135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonkovsky H.L., Snow K.K., Malet P.F., Back-Madruga C., Fontana R.J., Sterling R.K., et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2007;46:420–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen M.C., Hung H.C., Chang H.J., Yang S.S., Tsai W.C., Chang S.C. Assessment of educational needs and quality of life of chronic hepatitis patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:148. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2082-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cosassais S., Schwarzinger M., Pol S., Fontaine H., Larrey D., Pageaux G.P., et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis c infection: severe comorbidities and disease perception matter more than liver-disease stage. PloS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daida Y.G., Boscarino J.A., Moorman A.C., Lu M., Rupp L.B., Gordon S.C., et al. Mental and physical health status among chronic hepatitis b patients. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:1567–1577. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02416-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doyle J.S., Grebely J., Spelman T., Alavi M., Matthews G.V., Thompson A.J., et al. Quality of life and social functioning during treatment of recent hepatitis c infection: a multi-centre prospective cohort. PloS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drazic Y.N., Caltabiano M.L. Chronic hepatitis B and C: exploring perceived stigma, disease information, and health-related quality of life. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15:172–178. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ezbarami Z.T., Hassani P., Tafreshi M.Z., Majd H.A. A qualitative study on individual experiences of chronic hepatitis B patients. Nurs Open. 2017;4:310–318. doi: 10.1002/nop2.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta R., Avasthi A., Chawla Y.K., Grover S. Psychiatric morbidity, fatigue, stigma and quality of life of patients with hepatitis b infection. J Clin Hepatol. 2020;10:429–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.HassanpourDehkordi A., Mohammadi N., NikbakhatNasrabadi A. Hepatitis-related stigma in chronic patients: a qualitative study. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;29:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haq N., Hassali M.A., Shafie A.A., Saleem F., Aljadhey H. A cross sectional assessment of health related quality of life among patients with hepatitis-B in Pakistan. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:91. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jang Y., Ahn S.H., Lee K., Lee J., Kim J.H. Psychometric evaluation of the Korean version of the hepatitis B quality of life questionnaire. PloS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horváth G., Keleti T., Makara M., Ungvari G.S., Gazdag G. Effect of hepatitis C infection on the quality of life. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2018;54:386–390. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang R., Rao H., Shang J., Chen H., Li J., Xie Q., et al. A cross-sectional assessment of health-related quality of life in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection with EQ-5D. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:124. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0941-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jang E.S., Kim Y.S., Kim K.A., Lee Y.J., Chung W.J., Kim I.H., et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in Korean patients with chronic hepatitis C infection using SF-36 and EQ-5D. Gut Liver. 2018;12:440–448. doi: 10.5009/gnl17322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karacaer Z., Cakir B., Erdem H., Ugurlu K., Durmus G., Ince N.K., et al. Quality of life and related factors among chronic hepatitis b-infected patients: a multi-center study, Turkey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:153. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0557-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim S.J., Han K.T., Lee S.Y. Quality of life correlation with socioeconomic status in Korean hepatitis-B patients: a cross sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:55. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0251-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hill R., Pfeil M., Moore J., Richardson B. Living with hepatitis C: a phenomenological study. J Clin Nurs. 2014;24:428–438. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lam E.T.P., Lam C.L.K., Lai C.L., Yuen M.F., Fong D.Y.T., So T.M.K. Health-related quality of life of Southern Chinese with chronic hepatitis B infection. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:52. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu Y., Zhang S., Zhao Y., Du J., Jin G., Shai S., et al. Development and application of the Chinese (Mainland) version of chronic liver disease questionnaire to assess the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with chronic hepatitis B. PloS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu M., Li L., Zheng S.J., Zhao J., Ungvari G.S., Hall B.J., et al. Prevalence of major depression and its associations with demographic and clinical characteristics and quality of life in Chinese patients with HBV-related liver disease. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31:287–290. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mittal P., Matreja P.S., Rao H.K., Khanna P. Prevalence and impact of hepatitis on the quality of life of patients. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol. 2015;5:90–94. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwarzenberg S.J., Ling S.C., Cloonan Y.K., Lin H.H.S., Evon D.M., Murray K.F., et al. Health-related quality of life in pediatric patients with chronic hepatitis b living in the United States and Canada. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:760–769. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strauss E., Porto-Ferreira F.A., de Almeida-Neto C., Teixeira M.C.D. Altered quality of life in the early stages of chronic hepatitis C is due to the virus itself. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014;38:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vahidnia F., Stramer S.L., Kessler D., Shaz B., Leparc G., Krysztof D.E., et al. Recent viral infection in US blood donors and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) Qual Life Res. 2017;26:349–357. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valizadeh L., Zamanzadeh V., Zabihi A., Negarandeh R., Amiri S.R.J. Qualitative study on the experiences of hepatitis B carriers in coping with the disease. Jpn J Nur Sc. 2019;16:194–201. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wallace J., McNally S., Richmond J., Hajarizadeh B., Pitts M. Managing chronic hepatitis B: a qualitative study exploring the perspectives of people living with chronic hepatitis B in Australia. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:45. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wallace J., Pitts M., Liu C., Lin V., Hajarizadeh B., Richmond J., et al. More than a virus: a qualitative study of the social implications of hepatitis B infection in China. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:137. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0637-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woo G., Tomlinson G., Yim C., Lilly L., Therapondos G., Wong D.K.H., et al. Health state utilities and quality of life in patients with hepatitis B. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:445–451. doi: 10.1155/2012/736452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang H., Ren R., Liu J., Mao Y., Pan G., Men K., et al. Health-related quality of life among patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a cross-sectional study in Jianping County of Liaoning Province, China. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/6716103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhuang G., Zhang M., Liu Y., Guo Y., Wu Q., Zhou K., et al. Significant impairment of health-related quality of life in mainline Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B: a cross-sectional survey with pair-matched healthy controls. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:101. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou K.N., Zhang M., Wu Q., Ji Z.H., Zhang X.M., Zhuang G.H. Psychometrics of chronic liver disease questionnaire in Chinese chronic hepatitis B patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2494–3501. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i22.3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Avery L., Exley C., McPherson S., Trenell M.I., Anstee Q.M., Hallsworth K. Lifestyle behavior change in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a qualitative study of clinical practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1968–1971. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Balp M., Krieger N., Przybysz R., Way N., Cai J., Zappe D., et al. The burden of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) among patients from Europe: a real-world patient-reported outcomes study. JHEP Rep. 2019;1:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chawla K.S., Talwalkar J.A., Keach J.C., Malinchoc M., Lindor K.D., Jorgensen R. Reliability and validity of the chronic liver disease questionnaire (CLDQ) in adults with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;16:3. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2015-000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cook N.S., Nagar S.H., Jain A., Balp M.M., Mayländer M., Weiss O., et al. Understanding patient preferences and unmet needs in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): insights from a qualitative online bulletin board study. Adv Ther. 2019;36:478–491. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0856-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dan A.A., Kallman J.B., Wheeler A., Younoszai Z., Collantes R., Bondini S., et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with non-alcoholic liver disease. Aliment Pharmcol Ther. 2007;26:815–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.David K., Kowdley K.V., Unalp A., Kanwal F., Brunt E.M., Schwimmer J.B., et al. Quality of life in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: baseline data from the NASH CRN. Hepatology. 2009;49:1904–1912. doi: 10.1002/hep.22868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Golabi P., Otgonsuren M., Cable R., Felix S., Koenig A., Sayiner M., et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with impairment of health related quality of life (HRQOL) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;9:14. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0420-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huber Y., Boyle M., Hallsworth K., Tiniakos D., Straub B.K., Labenz C., et al. Health-related quality of life in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associates with hepatic inflammation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:2085–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kerkar N., D’Urso C., Van Nostrand K., Kochin I., Gault A., Suchy F., et al. Psychosocial outcomes for children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease over time and compared with obese controls. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:77–82. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31826f2b8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kistler K.D., Molleston J., Unalp A., Abrams S.H., Behling C., Schwimmer J.B., et al. Symptoms and quality of life in obese children and adolescents with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:396–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Samala N., Desai A., Vilar-Gomez E., Smith E.R., Gawrieh S., Kettler C.D., et al. Decrease quality of life s significantly associated with body composition in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2980–2988. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sayiner M., Stepanova M., Pham H., Noor B., Walters M., Younossi Z.M. Assessment of health utilities and quality of life in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3:1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2016-000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tapper E.B., Lai M. Weight loss results in significant improvements in quality of life for patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective cohort study. Hepatology. 2016;63:1184–1189. doi: 10.1002/hep.28416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Younossi Z.M., Stepanova M., Henry L., Racila A., Lam B., Pham H.T., et al. A disease-specific quality of life instrument for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: CLDQ-NAFLD. Liver Int. 2017;37:1209–1218. doi: 10.1111/liv.13391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Younossi Z.M., Stepanova M., Anstee Q.M., Lawitz E.J., Wong V.W.S., Romero-Gomez M., et al. Reduced patient-reported outcome scores associate with level of fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:2552–2560. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abdi F., Daryani N.E., Khorvash F., Yousefi Z. Experiences of individuals with liver cirrhosis. A qualitative study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2015;38:252–257. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bajaj J.S., Thacker L.R., Wade J.B., Sanyal A.J., Heuman D.M., Sterling R.K., et al. PROMIS computerized adaptive tests are dynamic instruments to measure health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1123–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hansen L., Chang M.F., Lee C.S. Physical and mental quality of life in patients with end-stage liver disease and their informal caregivers. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fagerström C., Frisman G.H. Living with liver cirrhosis. A vulnerable life. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017;40:38–46. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Janani K., Jain M., Vargese J., Srinivasan V., Harika K., Micheal T. Health-related quality of life in liver cirrhosis patients using SF-36 and CLDQ questionnaires. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018;4:232–239. doi: 10.5114/ceh.2018.80124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kanwal F., Gralnek I.M., Hays R.D., Zeringue A., Durazo F., Han S.B., et al. Health-related quality of life predicts mortality in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:793–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Les I., Doval E., Flavia M., Jacas C., Cardenas G., Esteban R., et al. Quality of life in cirrhosis is related to potentially treatable factors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:221–227. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283319975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Marchesini G., Bianchi G., Amodio P., Salerno F., Merli M., Panella C., et al. Factors associated with poor health-related quality of life of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:170–178. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nagel M., Labenz C., Wörns M.A., Marquardt J.U., Galle P.R., Schattenberg J.M., et al. Impact of acute-on-chronic liver failure and decompensated liver cirrhosis on psychosocial burden and quality of life of patients and their close relatives. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:10. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1268-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Obradovic M., Gluvic Z., Petrovoc N., Obradovic M., Tomasevic R., Dugalic P., et al. A quality of life assessment and the correlation between generic and disease-specific questionnaires scores in outpatients with chronic liver disease-pilot study. Rom J Intern Med. 2017;55:129–137. doi: 10.1515/rjim-2017-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Parkash O., Iqbal R., Jafri F., Azam I., Jafri W. Frequency of poor quality of life and predictors of health related quality of life in cirrhosis at a tertiary care hospital Pakistan. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:446. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shabanloei R., Ebrahimi H., Ahmadi F., Mohammadi E., Dolatkhah R. Despair of treatment. A qualitative study of cirrhotic patients’ perception of treatment. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017;40:26–37. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shiraki M., Nishiguchi S., Saito M., Fukuzawa Y., Mizuta T., Kaibori M., et al. Nutritional status and quality of life in current patients with liver cirrhosis as assessed in 2007–2011. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:106–112. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sumskiene J., Sumskas L., Petrauskas D., Kupcinskas L. Disease-specific health-related quality of life and its determinants in liver cirrhosis patients in Lithuania. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7792–7797. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i48.7792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tapper E.B., Baki J., Parikh N.D., Lok A.S. Frailty, psychoactive medications, and cognitive dysfunction are associated with poor patient-related outcomes in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2019;69:1676–1685. doi: 10.1002/hep.30336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thiele M., Askgaard G., Timm H.B., Hamberg I., Gluud L.L. Predictors of health-related quality of life in outpatients with cirrhosis: results from a prospective cohort. Hepat Res Treat. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/479639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang Y., Yang Y., Lv J., Zhang Y. LC-PROM: validation of a patient reported outcomes measure for liver cirrhosis patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:75. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0482-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hansen L., Rosenkranz S.J., Vaccaro G.M., Chang M.F. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma near the end of life. A longitudinal qualitative study of their illness experience. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38:19–27. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fan S., Eiser C. Illness experience in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: an interpretative phenomenological analysis study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:203–208. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834ec184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fan S.-Y., Eiser C., Ho M.-C., Lin C.-Y. Health-related quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: the mediation effects of illness perceptions and coping. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1353–1360. doi: 10.1002/pon.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li L., Mo F., Hui E.P., Chan S.L., Koh K., Tang N.L.S., et al. The association of liver function and quality of life of patients with liver cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;66:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12876-019-0984-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Palmieri V.O., Santovito D., Margari F., Lozupone M., Minerva F., Gennaro C.D., et al. Psychopathological profile and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cirrhosis. Clin Exp Med. 2015;15:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s10238-013-0267-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ryu E., Kim K., Cho M.S., Kwon I.G., Kim H.S., Fu M.R. Symptom cluster and quality of life in Korean patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:3–10. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b4367e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Steel J.L., Chopra K., Olek M.C., Carr B.I. Health-related quality of life: hepatocellular carcinoma, chronic liver disease, and the general population. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:203–215. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sun V., Ferrell B., Juarez G., Wagman L.D., Yen Y., Chung V. Symptom concerns and quality of life in hepatobiliary cancers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:45–52. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.E45-E52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Qiao C., Zhai X., Ling C., Lang Q.B., Dong H.J., Liu Q., et al. Health-related quality of life evaluated by tumor node metastasis staging system in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2689–2694. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i21.2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Guetterman T.C., Fetters M.D., Creswell J.W. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:554–561. doi: 10.1370/afm.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kennedy-Martin T., Bae J.P., Paczkowski R. Health-related quality of life burden of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a robust pragmatic literature review. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2018;19:28. doi: 10.1186/s41687-018-0052-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Asrani S.K., Devarbhavi H., Eaton J. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70:151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.McSweeney L., Breckons M., Fattakhova G., Oluboyede Y., Vale L., Ternent L., et al. Health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcome measures in NASH-related cirrhosis. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100099. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Low J.T.S., Rohde G., Pittordou K., Candy B., Davis S., Marshall A., et al. Supportive and palliative care in people with cirrhosis: international systematic review of the perspective of patients, family members and health professionals. Hepatology. 2018;69:1260–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Volk M.L., Fisher N., Fontana R.J. Patient knowledge about disease self-management in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:302–305. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Grønkjær L.L., Berg K., Søndergaard R., Møller M. Assessment of written patient information pertaining to cirrhosis and its complications: a pilot study. J Patient Exp. 2020;7:499–506. doi: 10.1177/2374373519858025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Huh J., Ackerman M.S. Collaborative help in chronic disease management: supporting individualized problems. CSCW Conf Comput Support Coop Work. 2012;2021:853–862. doi: 10.1145/2145204.2145331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hellqvist C., Berterö C., Dizdar N., Sund-Levander M., Hagell P. Self-management education for persons with Parkinson’s disease and their care partners: a quasi-experimental case-control study in clinical practice. Parkinsons Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/6920943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vaughn-Sandler V., Sherman C., Aronsohn A., Volk M.L. Consequences of perceived stigma among patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:681–686. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2942-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Album D., Westin S. Do diseases have a prestige hierarchy? A survey among physicians and medical students. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.