Abstract

Background and Purpose

Impaired level of consciousness (LOC) on presentation at hospital admission in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) may affect outcomes and the decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment (WOLST).

Methods

Patients with ICH were included across 121 Florida hospitals participating in the Florida Stroke Registry from 2010–2019. We studied the effect of LOC on presentation on in-hospital mortality (primary outcome), WOLST, ambulation status on discharge, hospital length of stay, and discharge disposition.

Results

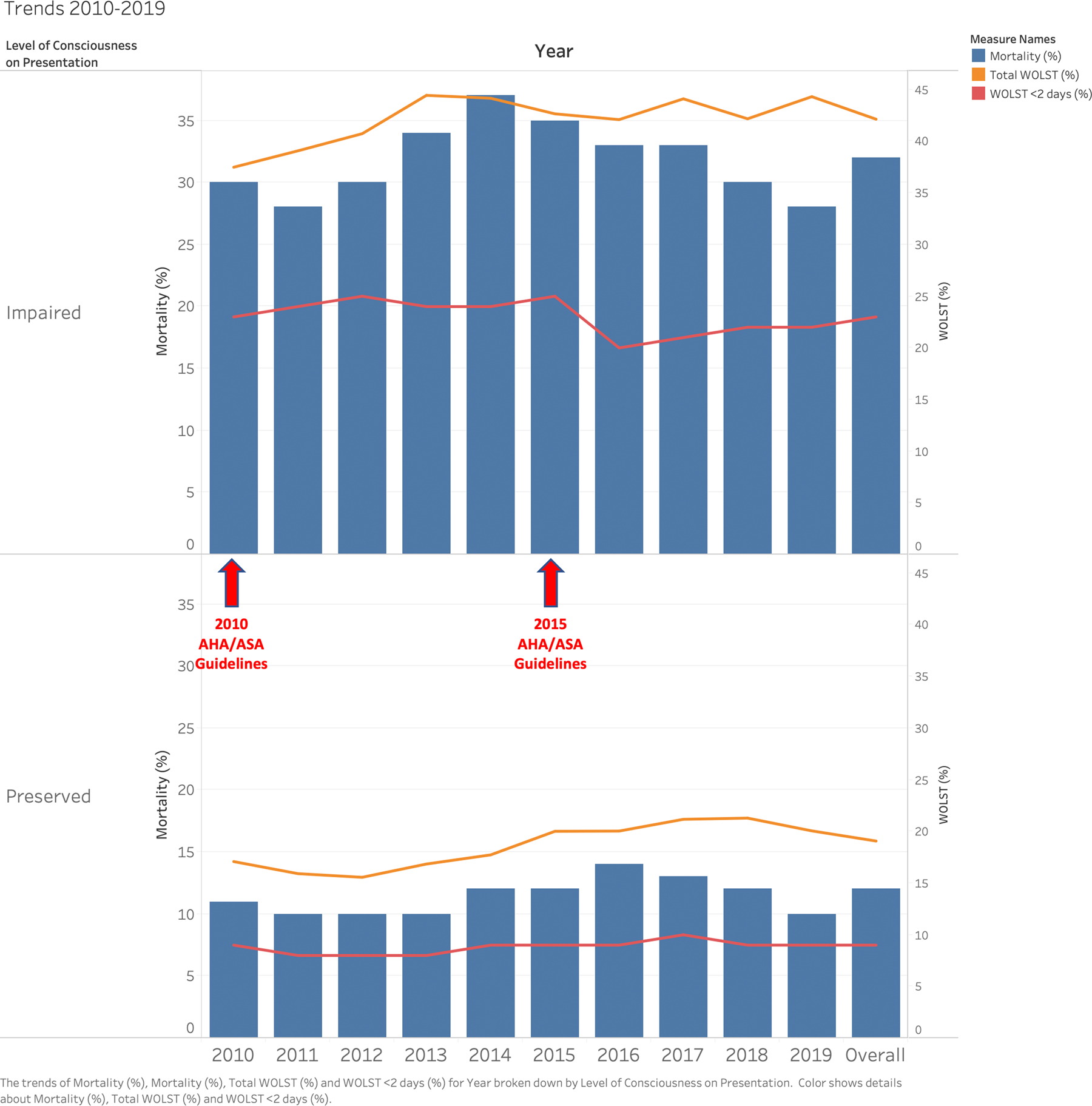

Among 37,613 cases with ICH (mean age 71, 46% women, 61% white, 20% Black, 15% Hispanic), 12,272 (33%) had impaired LOC at onset. Compared to cases with preserved LOC, patients with impaired LOC were older (72 vs. 70 years), more women (49% vs. 45%), more likely to have aphasia (38% vs. 16%), had greater ICH score (3 vs. 1), greater risk of WOLST (41% vs. 18%), and had an increased in-hospital mortality (32% vs. 12%). In the multivariable-logistic regression with generalized estimating equations accounting for basic demographics, comorbidities, ICH severity, hospital size and teaching status, impaired LOC was associated with greater mortality (OR 3.7, 95% CI 3.1–4.3, p < .0001), and less likely discharged home or to rehab (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.3 – 0.4, p < .0001). WOLST significantly mediated the effect of impaired LOC on mortality (mediation effect 190, 95% CI 152 – 229, p < .0001). Early WOLST (<2 days) occurred among 51% of patients. A reduction in early WOLST was observed in patients with impaired LOC after the 2015 AHA/ASA ICH guidelines recommending aggressive treatment and against early do-not-resuscitate.

Conclusions

In this large multicenter stroke registry, a third of ICH cases presented with impaired LOC. Impaired LOC was associated with greater in-hospital mortality and worse disposition at discharge, largely influenced by early decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment.

Keywords: Withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, intracerebral hemorrhage, impaired level of consciousness, mortality

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is associated with high early and late mortality (40% and 55%, respectively).1–4 After severe acute brain injury, however over a third of patients can reach independence at 6–12 months follow-up.5–7 Early do-not-resuscitate (DNR) is associated with doubling the hazard of death independent of basic demographics, location, intraventricular hemorrhage, and ICH volume.3, 4 The withhold or withdrawal of life sustaining treatment (WOLST) is common and is driven by the “poor prognosis” beliefs; leading to a self-fulfilling prophecy in patients who may have a reasonable neurologic outcome if treated aggressively.7–9 Current prognostic models are biased by the failure to account for WOLST.10–12 Impaired level of consciousness and the inability to follow commands shortly after acute brain injury may affect the decision of WOLST.13, 14

We aimed to evaluate the effect of impaired level of consciousness on presentation after ICH on outcomes and their temporal trends using data from Florida Stroke Registry (FSR) hospitals participating in the AHA Get with the Guideline-Stroke® (GWTG-S). We hypothesized that impaired level of consciousness on presentation at hospital admission is associated with high mortality after ICH and influenced by the decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment.

Materials and Methods

Data Availability Statement

FSR analyses are available per request sent to the FSR Biostatistics Core and after approval of the FSR Publication Committee.

Study Population

Using the Florida Stroke Registry (FSR), we identified a total of 37,613 cases across 121 centers with a final diagnosis of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) between 2010 and 2019. At ICH onset, 12,272 (33%) cases had impaired level of consciousness (LOC) that was identified using one of the GTWG-S questions on the presence of altered level of consciousness on initial exam findings. We followed the STROBE guidelines in this article.

Case Identification and Data Abstraction

Originally funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders (NINDS), the stroke registry included data from Get with the Guideline-Stroke® (GWTG-S) participating hospitals in Florida and Puerto Rico (2010–2017) and was referred to as the Florida-Puerto Rico Collaboration to Reduce Stroke Disparities (FL-PR CReSD).15–17 Since 2017 the registry continued as the Florida Stroke Registry with funding support through the state of Florida (COHAN-A1). Deidentified data from hospitalized patients with the primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, and stroke not otherwise specified are included in the registry.

The University of Miami’s institutional review board approved this study. Each participating center received institutional ethics approval to enroll patients in the Registry without requiring individual patient consent under the common rule or a waiver of authorization and exemption from subsequent review by their institutional review board.

This study was restricted to FSR cases with a final diagnosis of ICH. Data collected included patient demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status), comorbidities (smoking, alcohol/drug use, hypertension, diabetes), the presence of aphasia or language disturbance, time from stroke onset to arrival in the emergency department, time to the initial head computed tomography (door to CT), hospital level characteristics (academic status, stroke center type – comprehensive, primary, or thrombectomy capable), and disease severity (ICH and/or GCS scores).11, 12

The withhold or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment status was identified as documented in GWTG-S as a discrete data element, in addition to the timing of WOLST as following: day 0 or 1, day 2 or after, or timing unclear. Outcomes included in-hospital mortality, ambulation status at discharge (independent, need assistance, unknown), hospital length of stay, and discharge disposition (home/in patient rehabilitation or other).

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was to determine the risk of in-hospital mortality by level of consciousness on presentation after ICH. Our secondary outcomes included ambulation status on discharge, hospital length of stay, and discharge disposition status by LOC. We also evaluated temporal trends in the proportion of mortality and WOLST by the LOC.

For patient characteristics, continuous variables were summarized as median with first and third quartiles (Q1 and Q3). Pearson chi-squared and Kruskall-Wallis tests were used to compare descriptive statistics. A multivariable-logistic regression with generalized estimating equations (GEE) accounted for demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status), comorbidities (smoking, alcohol/drug use, hypertension, diabetes), ICH severity (using ICH and/or GCS scores), hospital size and teaching status was calculated to test the association of LOC and the different outcomes on discharge. Mediation analysis was conducted by the product of coefficients method as outlined by Iaccobucci (2012) in order to determine whether WOLST and the timing of WOLST mediate in-hospital mortality in impaired LOC patients.18 Logistic models were fitted by first regressing the dichotomized mediator “WOLST” on the exposure “impaired LOC” (path a) and then regressing the outcome “in-hospital mortality” on WOLST after adjusting for impaired LOC (path b). The product of the standardized regression coefficients was itself standardized and a z-test was conducted to determine whether the medication effect was significantly different from zero. We adjusted for basic demographics in the mediation analysis model (age, sex, race/ethnicity).

Most variables had missing values in fewer than 5% of cases, except for onset to arrival time (57% missing), ICH score (82% missing), length of stay (12% missing) and GCS score (73% missing). The complete case approach and the missing indicator approach were used to include the full sample for variables with a large proportion of missingness as previously described.19 The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 software (SAS Institute).

Results

Study Population

A sample of 37,613 ICH cases was included in this study from which 12,272 (33%) had impaired LOC at hospital admission. Median age was 71 (Q1, Q3; 58, 81) years, 46% were women, 61% white, 20% black, and 15% Hispanic. Two thirds of patients had hypertension, 24% had diabetes, and 11% were smokers. Over a third of patients had no health insurance (38%). Compared to patients with preserved LOC, patients with impaired LOC were older (72 vs. 70, p<.001) years, more likely women (49% vs. 45%, p<.001), more likely to have aphasia or language disturbance (38% vs. 16%, p<.001), had lower median GCS score (9 vs. 15, P<.001), and had greater median ICH score (3 vs. 1, p<.001). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Characteristics and Outcomes of Intracerebral Hemorrhage Patients Stratified by Level of Consciousness on Presentation

| Characteristics/Outcome*+ | Overall Patients (n = 37,613) |

Patients with Preserved Level of Consciousness (n = 25,341) |

Patients with Impaired Level of Consciousness (n = 12,272) |

P Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Q1, Q3), y | 71 (58, 81) | 70 (58, 80) | 72 (59, 82) | <.001 |

| Female (%) | 17,439 (46) | 11,431 (45) | 6,008 (49) | <.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | <.001 | |||

| Florida White | 21,599 (61) | 14,464 (60) | 7,135 (61) | |

| Florida Black | 7,031 (20) | 4,709 (20) | 2,322 (20) | |

| Florida Hispanic | 5,217 (15) | 3,560 (15) | 1,657 (14) | |

| Insurance Status (%) | <.001 | |||

| Private | 11,871 (32) | 7,680 (30) | 4,191 (34) | |

| Medicare | 11,438 (30) | 6,612 (26) | 4,826 (39) | |

| No Insurance | 4,470 (12) | 2,723 (11) | 1,747 (14) | |

| Unknown | 9,834 (26) | 8,326 (33) | 1,508 (12) | |

| Smoking (%) | 4,206 (11) | 2,916 (12) | 1,290 (11) | .004 |

| Drugs or Alcohol Use (%) | 2,085 (6) | 1,400 (6) | 685 (6) | NS |

| Hypertension (%) | 25,654 (68) | 17,359 (69) | 8,295 (68) | NS |

| Diabetes (%) | 8,950 (24) | 6,022 (24) | 2,928 (24) | NS |

| Onset to Arrival Time (Q1, Q3), min | 171 (60, 489) | 168 (60, 486) | 177 (61, 498) | <.001 |

| Door to CT Time (Q1, Q3), min | 34 (14, 87) | 33 (13, 89) | 36 (16, 83) | <.001 |

| Aphasia or Language Disturbance (%) | 8,645 (23) | 4,020 (16) | 4,625 (38) | <.001 |

| GCS score (Q1, Q3)** | 14 (8, 15) | 15 (12, 15) | 9 (5, 13) | <.001 |

| ICH Score (Q1, Q3)** | 2 (1, 3) | 1 (0, 1) | 3 (1, 4) | <.001 |

| Stroke Center Type (%) | <.001 | |||

| CSC | 26,032 (69) | 17,108 (68) | 8,924 (73) | |

| PSC | 7,181 (19) | 5,086 (20) | 2,095 (17) | |

| TSC | 3,769 (10) | 2,710 (11) | 1,059 (9) | |

| Other | 631 (2) | 437 (2) | 194 (2) | |

| Teaching Hospital (%) | 12,006 (32) | 7,068 (28) | 4,938 (40) | <.001 |

| Length of Stay (Q1, Q3), days** | 5 (3, 10) | 5 (3, 10) | 5 (2, 11) | <.001 |

| Surgical Treatment | <.001 | |||

| EVD | 557 (44) | 254 (37) | 303 (51) | |

| Craniotomy Clot Evacuation | 395 (31) | 244 (36) | 151 (25) | |

| Stereotaxic Evacuation | 33 (3) | 19 (3) | 14 (2) | |

| Endoscopic Evacuation | 16 (1) | 9 (1) | 7 (1) | |

| Hemicraniectomy | 31 (2) | 14 (2) | 17 (3) | |

| In-Hospital Mortality (%) | 6,925 (18) | 3,058 (12) | 3,867 (32) | <.001 |

| WOLST (%) | <.001 | |||

| Day 0 or 1 | 4,872 (51) | 2,160 (47) | 2,712 (54) | |

| Day 2 or after | 4,577 (48) | 2,358 (51) | 2,219 (44) | |

| Timing unclear | 183 (2) | 95 (2.1) | 88 (2) | |

| Ambulation at Discharge (%) | <.001 | |||

| Independent | 8,022 (21) | 6,674 (26) | 1,348 (11) | |

| Unable/Need Assistance | 15,025 (40) | 9,586 (38) | 5,439 (44) | |

| Unknown | 14,566 (39) | 9,081 (36) | 5,485 (45) | |

| Discharge Disposition (%) | <.001 | |||

| Home/Rehab | 15,927 (42) | 12,798 (51) | 3,129 (26) | |

| Other | 21,686 (58) | 12,543 (50) | 9,143 (75) |

Abbreviations: CT, Computed Tomography; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ICH, Intracerebral Hemorrhage; CSC, Comprehensive Stroke Center; PSC, Primary Stroke Center; TSC, Thrombectomy-Capable Stroke Center; EVD, external ventricular drain; WOLST, withhold or withdrawal life-sustaining treatment.

Data are presented as number (%) unless otherwise specified.

Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

ICH score had 82% of missing data, length of stay had 12% of missing data and GCS score had 73% of missing data.

Mortality and Withhold/Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Treatment

In-hospital mortality was reported in 6,925 (18%) cases; 32% in those with impaired LOC at onset and 12% in non-impaired LOC (p < .001). WOLST was decided in 9,632 (26%) cases; 41% in those with impaired LOC and 18% in non-impaired LOC (p < .001). We found that WOLST occurred in 28% in those with health insurance and 25% in those without (p <.0001). In cases with WOLST, the decision was made early, on day 0 or 1 of admission in 51% cases. In the impaired LOC group, 54% of WOLST happened early on day 0 or 1 vs 47% in the preserved LOC group. (Table 1) Temporal trends of mortality and WOLST are shown in Figure 1. Although both 2010 and 2015 AHS/ASA guidelines recommended aggressive treatment and against early DNR, a decreased in early WOLST in those with impaired LOC was observed only after 2015.10, 20

Figure 1-. Temporal trends from 2010 to 2019 for In-hospital Mortality and Withhold/Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Treatment among ICH patients with and without impaired LOC at onset.

Caption: Bar graph (blue) and line (orange) showing trends of mortality and withhold/withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment (WOLST) by level of consciousness on presentation in intracerebral hemorrhage patients between 2010 and 2019 using the Florida Stroke Registry. The red line shows early (day 0 and 1) WOLST. Although both 2010 and 2015 AHS/ASA guidelines recommend aggressive treatment and against early DNR, a decreased in early WOLST was observed after 2015 in patients with impaired LOC.

In multivariable models, using the complete case approach, accounting for basic demographics, comorbidities, ICH score, hospital size and teaching status, impaired LOC on presentation was associated with higher mortality (odds ratio 1.5, 95% CI 1.1–2.1, p=.005). Using the missing indicator approach to account for the missing data for the ICH score, impaired LOC was associated with greater mortality (odds ratio 3.7, 95% CI 3.1–4.3, p < .0001). Using the missing indicator approach to account for the missing data for the GCS score, impaired LOC was also associated with greater mortality (odds ratio 3.7, 95% CI 3.1–4.4, p < .0001). Using the missing indicator approach accounting for basic demographics, comorbidities, hospital size and teaching status, impaired LOC on presentation was also associated with higher mortality (odds ratio 4, 95% CI 3.4–5, p < .0001).

WOLST significantly mediated the effect of impaired LOC on mortality (mediation effect 190, 95% CI 152 – 229, p < .0001). Additionally, early (day 0 or 1) WOLST mediated the effect of impaired LOC on mortality (mediation effect 67, 95% CI 40 – 95, p< .0001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2-. Withhold/Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Treatment Mediates Mortality in Impaired Level of Consciousness Patients.

Caption: Impaired level of consciousness on presentation is associated with increased mortality in intracerebral hemorrhage patients OR 3.7 (95% CI 3.1 – 4.3, P < .0001); adjusted for basic demographics, comorbidities, ICH severity, hospital size and teaching status. The withhold/withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment largely mediates mortality (mediation effect 190 95% CI 152 – 229, P <.0001); adjusted for basic demographics.

Ambulation Status on Discharge, Hospital Length of Stay, and Discharge Disposition

In a multivariable model, those with impaired LOC on presentation were less likely discharged home or to rehab (odds ratio 0.3, 95% CI 0.3 – 0.4, p < .0001) and were less likely to ambulate on discharge (odds ratio 0.3, 95% CI 0.3 – 0.4, p < .0001). A quarter of patients with impaired LOC were discharged to home or to rehab. We found no relation between impaired LOC and length of stay (odds ratio 1, 95% CI 0.9 – 1.1, p=.91) (Table 1). Total of 11% of cases with impaired LOC were independent at discharge in comparison to 26% of those without impaired LOC (p < .001).

Discussion

In this large multi-center stroke registry, a third of ICH cases presented with impaired LOC. Impaired LOC on presentation was associated with greater mortality, and worse disposition and ambulation status at discharge. Mortality was largely affected by the decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment. To our knowledge, this study is one of the largest studies to investigate the role of impaired consciousness on in-hospital mortality after intracerebral hemorrhage.

In US, 13.5% to 15% of patients in the neurological intensive care unit undergo WOLST, preceding up to 61% of all deaths.21–23 The concern is that pessimism among clinicians may result in premature WOLST and subsequently lead to a fatal outcome.8 In-hospital mortality following ICH is influenced by the rate at which treating hospitals use DNR orders.24 In-hospital mortality among WOLST patients was predicted to be 35% had they continued maximal therapy.25 Approximately 20% were also predicted to have modified Rankin scores of 0–3 with continuation of maximal therapy.25 Our results showed an in-hospital ICH mortality rate of 18%, which is lower than reported, but higher WOLST (26%) than previously reported.1–4 WOLST was done early on day 0 or 1 in 51% of patients, despite the AHA/ASA recommendations to postpone new DNR orders at least until the second full day of hospitalization.10, 20 However, we observed a decrease in early WOLST in patients with impaired LOC after the 2015 AHA/ASA guidelines publication. Interestingly, the rates of WOLST in our study are higher than the in-hospital mortality rates highlighting the uncertainty of our prognostication models. The current prognostic models, including the ICH score, are biased by the failure to account for WOLST.10–12 Avoidance of early DNR in the first 5 days after ICH resulted in a substantially lower mortality than predicted.26

Impaired level of consciousness and the inability to follow commands shortly after acute brain injury may affect the decision of WOLST in traumatic brain injury and in cardiac arrest patients.13, 14 Our study supports these findings in ICH patients with higher mortality and WOLST in patients with impaired LOC. We also found that WOLST primarily mediated the high in-hospital mortality rates in impaired LOC. In a case-series of 87 supratentorial ICH patients, GCS of ≤8 and large ICH volume were associated with high mortality of 67%, with 77% WOLST rate in those who died.8 These findings may reflect the pessimistic view bias (self-fulfilling prophecy) after acute brain injury. More importantly, 15% of patients in coma are in the state of cognitive motor dissociation and they have brain activation to commands measured by electroencephalogram and/or magnetic resonance imaging with higher chances of long-term functional recovery.27

In this study, 11% of patients with impaired LOC were independent on discharge and 26% were discharged to home or rehabilitation. More patients would be expected to recover during a longer time period as over a third of acute brain injury patients can reach independence at 6–12 months follow-up.5–7

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. We identified impaired LOC cases based on the presence of altered level of consciousness on initial exam findings, which may encompass patients with different level of consciousness; from confusional state to coma. Nevertheless, these patients had lower GCS score and worse disease severity. The use of GCS score to identify impaired LOC was not possible in our cohort due to significant missing values in 73%. Additionally, we had high missingness of the ICH score (82%). Our data lack the long-term outcomes after ICH including cognitive and functional outcomes. In-hospital mortality is insufficient for discussing prognosis with families and long-term follow-up data are important measures to fully assess the impact of the self-fulfilling prophecy. Moreover, as with most large-scale registry-based studies, our study lacks detailed information on patients, e.g., radiographic (hemorrhage size, etiology, location, the presence or absence of intraventricular hemorrhage), the use of anesthetics and/or sedatives, and detailed clinical assessments (brainstem reflexes and motor exam). We used ICH score to reflect the hemorrhage severity and used both the complete case and the missing indicator approaches. Although we found a statistically significant difference in the rate of WOLST between those with health insurance (28%) and those without (25%) in this large sample, other factors such as demographics, clinical characteristics, family support/preferences, and imaging features may have an important effect on this difference and warrant further careful exploration in future studies. Finally, we didn’t have data on the withheld or withdrawn treatments, such as mechanical ventilation, vasopressors use, feeding tube placement, and tracheostomy. Despite these limitations, the study provides a reasonable overview of the practice patterns and outcomes in patients presenting with impaired LOC after ICH in a real world hospital settings of a large number of patients included in a state-wide stroke registry.

Summary

In conclusion, WOLST is decided early and frequently after ICH mediating the rate of in-hospital mortality in patients with impaired LOC. Clinicians should provide aggressive care and avoid early WOLST after presentation to limit the impact of this self-fulfilling prophecy in acute brain injury patients. A randomized clinical trial of early vs. delayed WOLST could pose ethical challenges. Future studies should focus on long-term mortality, cognitive and functional outcomes in patients with impaired level of consciousness after ICH. Investigations targeting early therapeutic interventions in this population are warranted.28 More studies on biomarkers to detect short and long-term recovery are needed to better inform prognosis and clinical decisions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Study concept and design: Ayham Alkhachroum, Negar Asdaghi MD MSc, Erika Marulanda Londono MD, Carolina M Gutierrez PhD, and Tatjana Rundek MD PhD

Acquisition of Data: Antonio J Bustillo MSPH

Analysis and interpretation of data: Ayham Alkhachroum, Antonio J Bustillo MSPH

Drafting the manuscript: Ayham Alkhachroum MD, Antonio J Bustillo MSPH, Daniel Samano MD MPH, Evie Sobczak MS, Mohan Kottapally MD, Amedeo Merenda MD

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Negar Asdaghi MD MSc, Erika Marulanda-Londono MD, Carolina M Gutierrez PhD, Sebastian Koch MD, Jose G. Romano MD, Kristine O’Phelan MD, Jan Claassen MD PhD, Ralph L. Sacco MD MS, and Tatjana Rundek MD PhD

Statistical analysis: Antonio J Bustillo MSPH

Study supervision: Ayham Alkhachroum MD and Tatjana Rundek MD PhD

Source of Funding

The Florida Stroke Registry is funded by the Florida Department of Health Funding #: COHAN A1

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ICH

Intracerebral hemorrhage

- WOLST

The withhold or withdrawal of life sustaining treatment

- FSR

Florida Stroke Registry

- GWTG-S

AHA Get with the Guideline-Stroke®

- LOC

level of consciousness

Footnotes

Disclosures

AB, NA, EML, CG, DS, ES, ML, AM, SK, JR, KO report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

AA is supported by an institutional KL2 Career Development Award from the Miami CTSI NCATS UL1TR002736.

SK reports a patent to Medical Device for treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage issued.

JR is supported by grant funding from NIH R01 NS084288, NIH R01 MD012467 and U24 NS107267. JR reports grants from Genentech outside the submitted work.

JC is supported by grant funding from the NIH R01 NS106014 and R03 NS112760, and the DANA Foundation. Additionally, JC reports grants from McDonnel Foundation, and other from iCE Neurosystems outside the submitted work.

RLS is funded by the Florida Department of Health for work on the Florida Stroke Registry and by grants from National Institutes of Health (R01 NS029993, R01 MD012467, R01 NS040807, U10NS086528), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR002736 and KL2 TR002737). RLS receives personal compensation from the American Heart Association for his role as Editor in Chief of Stroke.

TR is funded by the Florida Department of Health for work on the Florida Stroke Registry and by the grants from National Institutes of Health (R01 MD012467, R01 NS029993, R01 NS040807, 1U24 NS107267), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR002736 and KL2 TR002737).

This work represents the authors’ independent analysis of local or multicenter data gathered using the AHA Get With The Guidelines® (GWTG) Patient Management Tool but is not an analysis of the national GWTG dataset and does not represent findings from the AHA GWTG National Program

List of Supplemental Materials

STROBE checklist.

References

- 1.Pinho J, Costa AS, Araújo JM, Amorim JM, Ferreira C. Intracerebral hemorrhage outcome: A comprehensive update. J Neurol Sci 2019;398:54–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarrete-Navarro P, Rivera-Fernández R, López-Mutuberría MT, Galindo I, Murillo F, Dominguez JM, et al. Outcome prediction in terms of functional disability and mortality at 1 year among icu-admitted severe stroke patients: A prospective epidemiological study in the south of the european union (evascan project, andalusia, spain). Intensive Care Med 2003;29:1237–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zahuranec DB, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, Gonzales NR, Longwell PJ, Smith MA, et al. Early care limitations independently predict mortality after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 2007;68:1651–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zahuranec DB, Morgenstern LB, Sanchez BN, Resnicow K, White DB, Hemphill JC 3rd. Do-not-resuscitate orders and predictive models after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 2010;75:626–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wabl R, Williamson CA, Pandey AS, Rajajee V. Long-term and delayed functional recovery in patients with severe cerebrovascular and traumatic brain injury requiring tracheostomy. J Neurosurg 2018;131:114–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wahlster S, Sharma M, Chu F, Granstein JH, Johnson NJ, Longstreth WT, et al. Outcomes after tracheostomy in patients with severe acute brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurocrit Care 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Lazaridis C Withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in perceived devastating brain injury: The key role of uncertainty. Neurocrit Care 2019;30:33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker KJ, Baxter AB, Cohen WA, Bybee HM, Tirschwell DL, Newell DW, et al. Withdrawal of support in intracerebral hemorrhage may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Neurology 2001;56:766–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verkade MA, Epker JL, Nieuwenhoff MD, Bakker J, Kompanje EJ. Withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment in a mixed intensive care unit: Most common in patients with catastropic brain injury. Neurocrit Care 2012;16:130–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemphill JC 3rd, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, Becker K, Bendok BR, Cushman M, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 2015;46:2032–2060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemphill JC, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC, Tuhrim S. The ich score : A simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage editorial comment: A simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2001;32:891–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke JL, Johnston SC, Farrant M, Bernstein R, Tong D, Hemphill JC. External validation of the ich score. Neurocrit Care 2004;1:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turgeon AF, Lauzier F, Simard JF, Scales DC, Burns KE, Moore L, et al. Mortality associated with withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy for patients with severe traumatic brain injury: A canadian multicentre cohort study. CMAJ 2011;183:1581–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmer J, Torres C, Aufderheide TP, Austin MA, Callaway CW, Golan E, et al. Association of early withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy for perceived neurological prognosis with mortality after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2016;102:127–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smaha LA, Association AH. The american heart association get with the guidelines program. Am Heart J 2004;148:S46–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sacco RL, Gardener H, Wang K, Dong C, Ciliberti-Vargas MA, Gutierrez CM, et al. Racial-ethnic disparities in acute stroke care in the florida-puerto rico collaboration to reduce stroke disparities study. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Asdaghi N, Romano JG, Wang K, Ciliberti-Vargas MA, Koch S, Gardener H, et al. Sex disparities in ischemic stroke care: Fl-pr cresd study (florida-puerto rico collaboration to reduce stroke disparities). Stroke 2016;47:2618–2626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iacobucci D Mediation analysis and categorical variables: The final frontier 2012;22 (4), 582–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Shen C, Li X, Robins JM. On weighting approaches for missing data. Stat Methods Med Res 2013;22:14–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgenstern LB, Hemphill JC, Anderson C, Becker K, Broderick JP, Connolly ES, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 2010;41:2108–2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diringer MN, Edwards DF, Aiyagari V, Hollingsworth H. Factors associated with withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in a neurology/neurosurgery intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2001;29:1792–1797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naidech AM, Bernstein RA, Bassin SL, Garg RK, Liebling S, Bendok BR, et al. How patients die after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2009;11:45–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varelas PN, Abdelhak T, Hacein-Bey L. Withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies and brain death in the intensive care unit. Semin Neurol 2008;28:726–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemphill JC 3rd, Newman J, Zhao S, Johnston SC. Hospital usage of early do-not-resuscitate orders and outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2004;35:1130–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weimer JM, Nowacki AS, Frontera JA. Withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy in patients with intracranial hemorrhage: Self-fulfilling prophecy or accurate prediction of outcome? Crit Care Med 2016;44:1161–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgenstern LB, Zahuranec DB, Sánchez BN, Becker KJ, Geraghty M, Hughes R, et al. Full medical support for intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 2015;84:1739–1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Claassen J, Doyle K, Matory A, Couch C, Burger KM, Velazquez A, et al. Detection of brain activation in unresponsive patients with acute brain injury. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2497–2505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alkhachroum A, Eliseyev A, Der-Nigoghossian CA, Rubinos C, Kromm JA, Mathews E, et al. Eeg to detect early recovery of consciousness in amantadine-treated acute brain injury patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2020;91:675–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

FSR analyses are available per request sent to the FSR Biostatistics Core and after approval of the FSR Publication Committee.