Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) and obesity are closely inter-related and pose a major burden on health care in terms of morbidity and mortality. Weight loss has favorable metabolic benefits for glycemic control and improvement of metabolic syndrome. Bariatric surgery (BS) is the most effective treatment for weight loss with durable results as compared to lifestyle modification. BS procedures are categorized as restrictive and/or malabsorptive on the basis of physiological changes and their effectiveness varies, depending on the type of procedure. BS procedures have been associated with significant reduction in abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome components and glycemic control requiring fewer medications. Mechanisms for glycemic control include enforced caloric restriction, nutrient malabsorption and intestinal neuroendocrine hormones that diminish appetite and improve beta cell function. However, randomized control trial data for benefits of surgery toward micro and/or macrovascular diabetes complications is lacking. Long-term risks of surgery include nutritional deficiencies, osteoporosis, bone fractures, hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia need to be carefully balanced with metabolic benefits for individual patients.

Keywords: obesity, type 2 diabetes, bariatric surgery, weight loss, metabolic effects

Background

Chronic diseases lead to 7 out of 10 deaths every year in United States (US) and pose a major burden on health care accounting for 86% of national health care costs [1, 2]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and Obesity are two preventable chronic diseases with an approximate prevalence of 9.3% (29.1 million) and 34.9% (78.6 million) in US population [3, 4]. 245 billion dollars were spent on diabetes care in the United States in direct and indirect costs and $147 billion were spent in medical care of obese adults in 2012. Annual medical costs for people with obesity are $1,429 higher than those for people of normal weight [1].

The prevalence of obesity has doubled over the last 40 years and a similar drift is expected for DM prevalence to double in the next 40 years [5]. This trend illustrates a direct relationship between obesity and DM which was described in a prior study where severe obesity with a body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m2 was associated with a 40 fold increased risk of developing DM as compared to normal BMI <23 kg/m2 [6]. Obesity is an independent risk factor for mortality and increases the risk of developing other co-morbidities such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular (CV) disease, stroke, degenerative joint disease, obstructive sleep apnea and cancer [7, 8].

Obesity related morbidity and mortality risk has been shown to be reversible with modest weight loss [9]. Various weight loss interventions including lifestyle modifications and weight loss medications have shown excellent results, with up to 7– 12 % weight loss, but have not been able to show long-term benefits. Weight loss surgeries which were initially introduced in the 1960s have now become standard of care for patients with BMI ≥40 kg/m2 or BMI > 35 kg/m2 with obesity related comorbidities or obese patients who fail lifestyle and medical management. Bariatric surgery (BS) has shown to be the most effective weight-loss therapy with sustained results with approximated weight loss range of 12%–39% of pre-surgical body weight or 40–71% excess weight loss (EWL) [10].

We review here the association between obesity and DM, pathophysiology and metabolic benefits of BS on DM and related comorbidities as well as clinical implications of BS for DM management.

Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes (DM2)

Obesity is a disease state characterized by excess fat accumulation to an extent that is detrimental to health. It is defined as BMI of > 30 kg/m2 by World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity severity is categorized as class I - BMI 30–34.9 kg/m2, class II - BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2 or and class III - BMI > 40 kg/m2 [11]. Class III obesity has been further sub- categorized to quantify the metabolic disease risk in surgical literature as “severe obesity”- BMI ≥ 35 or 40, “morbid obesity”- BMI of ≥ 35 or 40–44.9 or 49.9 and “super obesity”-BMI of ≥ 45 or 50.

Risk factors that promote obesity include genetics, sedentary lifestyle, excess calorie consumption and imbalance between peripheral hormones that cause satiety and hunger. Hormones that promote satiety include Leptin produced solely in adipose tissue, Glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP-1) produced in the small intestine, cholecystokinin, enterostatin, polypeptide Y 3–36, α melanocyte-stimulating hormone, corticotropin-releasing hormone, tumor necrosis factor α TNF-α, and obestatin [12]. In contrast, Ghrelin is a strong appetite stimulant produced in the fundus that also stimulates growth hormone secretion. Other hormones that have a similar effect on appetite include neuropeptide Y, dynorphin, melanin-concentrating hormone, norepinephrine, growth hormone–releasing hormone, orexin-A, and orexin-B. The effect of some of these hormones will be discussed in more detail below.

DM2 is a complex metabolic disorder triggered by a combination of genetic and environmental factors that leads to development of insulin resistance, progressive pancreatic beta cell insufficiency resulting in hyperglycemia.

There are various hypothesized mechanisms by which obesity may lead to insulin resistance and diabetes. Figure 1 describes the possible mechanisms by which obesity may contribute to diabetes and diabetes related complications.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms by which obesity leads to diabetes and diabetes related complications. Adapted from Redinger RN. The Pathophysiology of Obesity and its Clinical Manifestations. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2007; 3(11):856–863, with permission.

The lipocentric model suggests that excess caloric intake causes excess lipogenesis, elevation of circulating free fatty acids and ectopic fat deposition in liver and muscle causing insulin resistance and subsequent hyperinsulinemia. This may lead to “lipotoxicity” via activation of inflammatory pathways and production of inflammatory adipocytokines such as TNF-α, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, retinol-binding protein 4, and resistin which disrupt glucose disposal [12, 13]. In addition, adiponectin (a cytokine released by adipose tissue that decreases insulin resistance) has shown to be deficient in obese patients. It is also suggested that ectopic fat deposition in the pancreas can contribute to impaired insulin secretion and hyperglycemia.

Approximately 75% of patients with DM on insulin have been reported to be overweight [14]. In both males and females, BMI is a major predictor of developing DM. In females the risk of developing DM is increased 5 fold with BMI > 25kg/m2, 28 fold with BMI >30 kg/m2 and 93 fold with BMI>35 kg/m2 [15]. Men are 2.2 times more likely to develop DM if there BMI is > 25 kg/m2 and 6.7 times more likely if there BMI is >30 kg/m2 [6] Westland et al. found similar results in there study in which 0.6% of normal weight men developed DM while the incidence of DM was 23.4% in overweight men [16].

Effects of weight loss

Various studies have suggested a positive impact of weight loss on DM and other obesity related complications.

A weight loss of 5 kg has been associated with more than 50% reduction in the risk of developing DM [15]. Similarly a 9 kg weight loss was associated with 30–40% decrease in DM related death [17]. There is a 15 % reduction in fasting blood glucose and a 7% drop in HbA1c seen with weight loss of 5 % body weight [18].

Reisen. et al. found a 20 % reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP) with 10 kg weight loss [19]. A similar improvement is seen in the lipid profile of patients, with a decrease in LDL by 1%, Triglycerides by 3% and increase in HDL by 1% for every kg of weight loss [20].

United States Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) study suggested that 5–10% of initial body weight loss via lifestyle modifications including diet and exercise reduced the incidence of DM2 by 58 % as compared to placebo [21]. The Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) trial showed that intensive lifestyle intervention lead to a weight loss of 8.6% of initial weight [22]. This was associated with mean glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) reduction to 6.6% along with improvement in BP, triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio. However, no benefits on mortality or CVD events were noted with intensive lifestyle modification.

Obesity is known to be a pro-inflammatory state and weight loss is associated with an improvement in obesity related inflammation via increase in adiponectin and reduction in TNF-α, Interleukin-6, Leptin and C-reactive peptide [23].

Restrictive and Malabsorptive Bariatric surgery (BS) procedures

BS procedures are associated with a greater weight loss as compared to other interventions such as lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy [24]. Current guidelines by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and American Society for Metabolic and BS, recommend BS for patients with BMI > 40 kg/m2 and patients with BMI >35 kg/m2 with comorbid diseases that can be alleviated or significantly improved by weight loss [25].

Obese patients with DM2 who undergo BS have remarkable improvement in their glycemic control with approximately 78% obtaining DM resolution and close to 85% experiencing improvement in their blood sugar control and reduction in anti-diabetic medications [26]

The effect of BS on weight loss, resolution of diabetes and cardio-metabolic parameters may vary depending on the type of BS procedures.

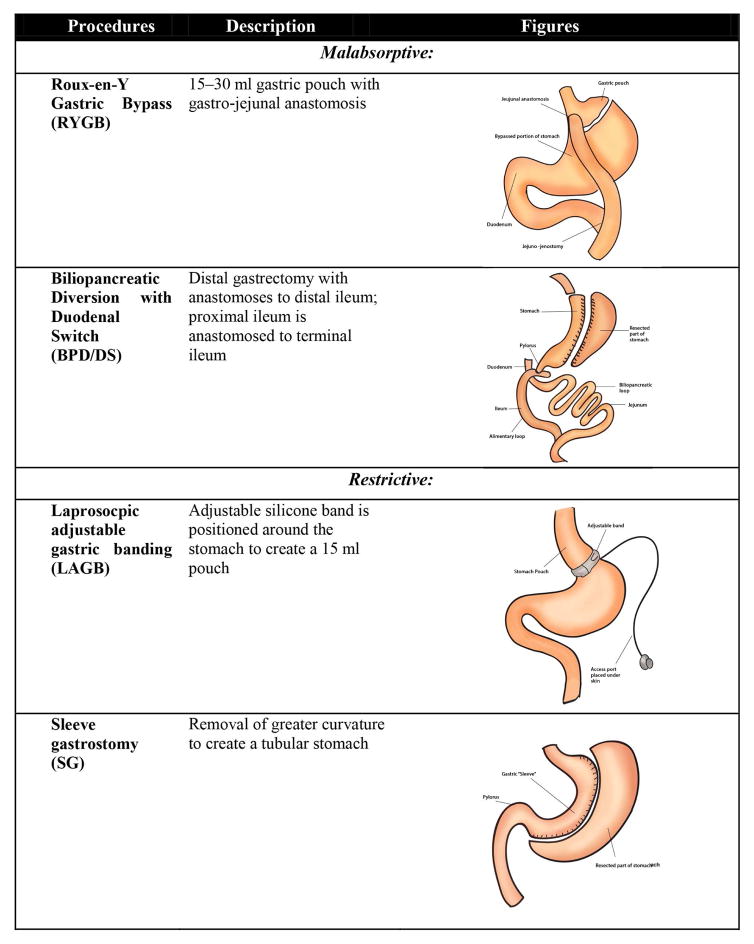

BS procedures are classified on the proposed mechanism of weight loss [27] and are described in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Commonly performed bariatric surgery procedures types, brief description of the procedure and illustrations of anatomical changes.

Malabsorptive

Malabsorptive procedures comprise of partial resection of small intestine, which causes reduction in intestinal mucosal area leading to lesser nutrient absorption. In addition these procedures also restrict caloric intake by limiting stomach size. Up to 85% of patients with DM2 who undergo this type of surgery achieve diabetes remission [28].

• Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB)

RYGB commonly known as gastric bypass surgery is the most commonly performed procedure and is gold standard for BS [29]. This procedure comprises of constructing a small stomach pouch, Roux and biliary limb which leads to restricted caloric intake and decreased absorption of nutrients. 95% of the stomach, the entire duodenum and a portion of the jejunum are bypassed. This surgery is primarily restrictive with some malabsorption.

• Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch (BPD/DS)

The BPD/DS consists of two components, a partial gastrectomy and intestinal bypass. This procedure is thought to preserve physiological digestive process. This surgery is majorly malabsorptive with some restriction.

Restrictive

Gastric restrictive procedures reduce caloric intake and cause satiety by limiting gastric volume. This can be done by surgically resizing the stomach as done in sleeve gastrostomy (SG) or laprosocpic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) or vertical gastroplasty (VBG). These procedures are associated with approximately 46.2% of excess body weight loss (EBW). These types of surgeries have shown to lead to DM remission in 56.7% of patients.

• Laprosocpic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB)

The LAGB is characterized by placement of adjustable band around the proximal stomach below the gastro-esophageal junction forming a small pouch. This procedure has lower morbidity and mortality as compared to other bariatric procedure but has shown to be less beneficial then malabsorptive procedure and is associated with higher risk of re-operations [30].

• Sleeve gastrostomy (SG)

The laparoscopic SG comprises of partial resection of the greater curvature of the stomach. This procedure is comparable to the malabsorptive procedures but has shown to have a greater effect that that of LAGB.

The efficacy of BS on metabolic pathways and diabetes remission depend on the type of surgery. Malabsorptive procedures lead to diabetes remission within days while this response is not seen with gastric restrictive procedures [31]. Diabetes remission was shown in 98% of type DM2 patient undergoing BPD, 84% with RYGB, 72% with VGB and 48% with LAGB [26].

Mechanisms for Diabetes (DM) remission

The main processes that lead to weight loss after BS are calorie restriction via anatomical restriction and malabsorption [10]. 30 to 70% of patients undergoing bariatric surgery develop some degree of malnutrition including protein–calorie deficiency, fat malabsorption, fat soluble vitamins, Vitamins B12 and C, iron, calcium, copper and zinc. Vagal denervation performed with some bariatric procedures may additionally contribute to weight loss via decreasing ghrelin levels. The role of ghrelin will be described later. Another hypothesized modification, which promotes weight loss, is change in intestinal microbiome after bariatric surgery. There is decrease in Firmicutes and increase in Bacteroides/Prevotella and E. coli depicting adaptation to a malnourished state.

There are various hypothesized mechanisms by which BS leads to improvement in glucose homeostasis. Of these three major contributors are weight loss, nutrient malabsorption and rerouting, and gut hormonal changes [32].

Weight loss

Weight loss is a key driver for achieving euglycemia in obese DM patients who undergo BS. Gastric volume restriction leads to early satiety, smaller meal consumption and reduced caloric intake. This improves hepatic insulin sensitivity and improves insulin clearance in the liver leading to lowering of fasting glucose levels. Additionally, caloric restriction reduces hyperinsulinemia and provides “rest” for beta-cell which results in enhanced beta-cell function [33]. The rate of DM remission after BS correlates with the degree of weight loss [34]. Relapse of glycemic control post BS is linked to inadequate surgical weight loss and weight regain. Post-BS patients have an overall decrease in amount of food intake and change in food choices with a decline in inclination towards calorie-rich, sugary and fat rich foods [10,35]. It is interesting that restrictive procedures lead to a lower rate of DM remission as compared to malabsorptive procedures such as RYGB or BPD in which patients become euglycemic within days of surgery and prior to significant weight loss [36, 37]. This suggests that weight loss is not the sole factor contributing to diabetes remission.

Malabsorption of nutrients

Malabsorptive procedures reduce excess intestinal absorption of glucose and lipids, which are thought to increase inflammation by increasing reactive oxygen species. This leads to improved insulin resistance and pancreatic beta-cell function, which decreases deposition of lipid metabolites in adipose and extra-adipose tissue such as skeletal muscles and liver and corrects the impaired adipose tissue signaling [38]. This malabsorption of nutrients is more pronounced with BPD and is not as significant with RYGB suggesting that additional factors may drive improvements in glycemic control [39, 40].

Foregut vs. Hindgut Hypothesis

Another principle to explain the effect of BS on glucose homeostasis is the redirecting of food course via anatomical changes in gastrointestinal tract as seen with RYGB and BPD. Rubino et al. suggested that obesity related overeating lead to chronic overstimulation of the alimental system causing metabolic and hormonal disruptions that are diabetogenic [33].

Based on rats’ studies, they also proposed the theory of the “foregut exclusion hypothesis” which suggests that delivery of nutrients to proximal small intestine leads to a release of a pro-diabetic factor, which is over secreted in diabetics [32]. Bypass of the duodenum and proximal jejunum avoids this effect and improves glycemic control.

Cummings et al. explained this via the “hindgut hypothesis”, which indicates that the improved glucose homeostasis after BS is attributable to hormonal responses to the increased nutrients delivery to distal small intestine [41]. The delivery of incompletely digested food causes overstimulation of specialized entero-endocrine L-cells that cause increased production of incretin hormones GLP-1 and peptide YY (PYY). GLP-1 improves glucose processing by increasing insulin secretion and action and slowing gastric emptying which also contributes to satiety. PYY regulates appetite, decreases adiposity and contributes to insulin induced glucose disposal. Kindel et al. suggested GLP-1 as a main component of gluco-regulation after BS [42].

Entero-endocrine hormones

The gastrointestinal tract comprises of an intricate neuroendocrine system and produces more than 100 hormonally active peptides [10]. Incretins are neuroendocrine hormones produced by the intestinal mucosa in response to food stimulus that cause increased insulin secretion [43]. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) is produced by duodenal K cells and GLP-1 comes from ileal L-cells and together these hormones account for 60% of the nutrient dependent insulin release. This incretin effect on insulin secretion is impaired in DM2.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)

GLP-1 is the best-studied incretin and appears to play an important role in glucose regulation, satiety and weight loss after BS. GLP-1 suppresses glucagon and ghrelin secretion and delays gastric emptying, which improves post-prandial hyperglycemia [44]. In some patients following RYGB, hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia with neuroglycopenia is observed and attributed to increases in GLP-1. Increases are also observed following SG but not after Lap Banding.

Laferrere et al. found no difference in GLP-1 levels with diet induced weight loss but reported an increase in post-prandial GLP-1 levels within 4 weeks of RYGB [43]. Samat et al. saw similar results in obese patients with DM2 at 1 year after gastric bypass surgery [45]. They found that GLP-1 was significantly elevated and was associated with increased insulin sensitivity and suppressed ghrelin. This increase in GLP-1 and improvement in beta-cell function was more pronounced in the RYGB group as compared to SG or intensive medical therapy group 2 years post-BS in the Surgical Therapy and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently (STAMPEDE) trial [46].

Ghrelin

Ghrelin is an appetite stimulant hormone which is majorly produced by A-like cells in the stomach fundus. This hormone regulates food intake, and has additional effects that leads to impaired insulin sensitivity and reduced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [43]. Ghrelin levels increase after diet induced weight loss [47]. On the contrary, low levels of ghrelin have been associated with RYGB and GS and may contribute to weight loss but are not seen with LAGB [10]. Ghrelin levels are affected by type of bariatric surgery, time from surgery and vagal nerve involvement.

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP)

GIP plays a part in lipid metabolism and is thought to have a direct relation to obesity. The impact of BS on GIP is not well understood but is thought to be related to removal of duodenal K cell during BS which leads to low GIP levels, less fat deposition and weight loss [10].

Additional neuroendocrine hormones, which play a role in BS induced weight loss and glucose homeostasis, include PYY, Glucagon like peptide 2 and oxyntomodulin. Other gastrointestinal hormones that have been studies in this regard and do not appear to play a major role include obestatin, cholecystokinin, apolipoprotein A4, enterostatin, neurotensin, motilin and vasoactive intestinal peptide.

Metabolic effects of Bariatric surgery and Outcomes

The metabolic effects of different types of BS on some of the obesity related complications and gut neuro-endocrine hormones have been described in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3.

Bariatric surgery procedures and their effect on metabolic parameters and obesity related complications. Adapted from Ara Keshishian. Weight loss procedure surgical procedures and outcomes. http://www.dssurgery.com/weight-loss-surgery-poster.php.

Figure 4.

Effects of bariatric surgery on intestinal neuroendocrine hormones. Adapted from Mingrone G. Role of the incretin system in the remission of type 2 diabetes following bariatric surgery. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2008; 18(8):574–579, with permission.

Weight loss

Presently, BS is the most effective approach to obesity in terms of magnitude of weight loss achieved and long term results. It has been associated with weight loss in the range of 12% to 39% of pre- surgical body weight or 40–71% EWL [10].

The Swedish Obese Subject (SOS) study was a major prospective study that assessed the effects of intentional weight loss via conventional treatment vs. BS in obese patients [48]. The results revealed that the intervention group had a % body weight loss of approximately 23% at 2 years, 17% at 10 years, 16% at 15 years and 18% at 20 years post-surgery [49]. The average weight loss in the control group was 0–1% during this time.

Similar results were seen in meta-analysis by Buchwald et al and systematic review by Ribaric et al. showed an average EWL of 61.2% and 75.3% respectively in patients undergoing BS [26, 50]. Gill et al. found a similar trend in obese DM2 patient who underwent SG with EWL of 47% [51]

The STAMPEDE trial showed more weight loss in BS group as compared to medical-therapy group after 1 year (RYGB −29.4±9.0 kg, SG −25.1±8.5 kg, medical therapy − 5.4±8.0 kg, P<0.001) and 3 years (RYGB − 24.5±9.1%, SG −21.1±8.9%, medical-therapy − 4.2±8.3%, P<0.001) [52, 53]

Meta-analysis of Randomized control trials (RCTs) in patients with DM2 and obesity undergoing BS by Gloy et al. showed a greater weight loss with BS (mean difference −26 kg (95% confidence interval −31 to −21), P<0.001) as compared to conventional treatment [54].

Glycemic Control in Diabetes (Observational and Randomized Control Trials (RCTs)

BS contributes to improved glycemic control via various mechanisms as described above and Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Role of intestinal hormones in glucose homeostasis following Roux-en Y surgery. Adapted from Ionut V, Bergman RN. Mechanisms Responsible for Excess Weight Loss after Bariatric Surgery. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2011; 5(5):1263–1282, with permission.

The concept of BS as a potential remedy for DM initially came from observational studies. Pories et al. found normalization of glucose tolerance in DM patients undergoing RYGB as early as 10 days after procedure [55]. 99% of obese DM2 patient showed an improvement in fasting plasma glucose and 83% of these patients had normalization of HBA1c and did not require any diabetes therapy at 7.6 years post-BS [56]. The SOS study found diabetes remission in 72% of patients with DM2 undergoing BS as compared to 21% in conventional group [57]. The DM prevalence 8 years after BS in SOS study remained stable while an increase in incidence of diabetes in control group was noted from 7.8 to 24.9%.

There is a persistent improvement in glycemia in obese DM2 patients undergoing BS in RCTs. Schauer et al. found a reduction in HbA1c in the BS arm (mean HbA1c 6.5%) as compared to medical therapy group (mean HbA1c 7.5%) at 1 year and 3 years (mean HbA1c RYGB 6.7%, SG 7%, medical therapy 8.4%) [52, 53]. In the BS group, the mean HbA1c and fasting serum glucose decreased to normal range in 83 % of patients and the diabetes medication requirements declined in 80% [58].

Mingrone et al. found biochemical remission of DM in obese DM2 patient undergoing BS at 2 years (RYGB 75% and BPPD 95 %) [59]. HbA1c was remarkably improved from baseline in the BS group (RYGB (−25.18±20.89%, BPD −43.01±9.64%, medical-therapy group −8.39±9.93). At 5 years follow up 50 % of the patients in BS arm maintained DM remission [60].

In the Diabetes Surgery Study, Ikrammuddin et al found a goal HBA1c of ≤7% in 75 % of patients undergoing BS as compared to 32% in the medical therapy group (OR, 6.0; 95% CI, 2.6–13.9) [61].

Gloy et al. noted a pooled relative risk for diabetes remission with BS of 22.1 (3.2 to 154.3, P=0.002) as compared to non-surgical treatment [54].

The role of BS in diabetes remission and the magnitude of improvement in glycemia are dependent on various factors. Procedure type (malabsorptive BS (BPD and RYGB)), younger age, higher peak weight loss, shorter duration of diabetes (<5 years 95%, 6–10 years 75%, >10 years 54%) lower diabetes severity (diet controlled) and lower central obesity have been associated with a higher DM remission rate [26, 62, 63]

Patient with type 1 DM undergoing BS did had some minor improvement in HbA1c despite similar weight loss to patients with DM2 [62].

Dyslipidemia

Visceral obesity is a key factor in developing insulin resistance and impairment of lipids metabolic pathway. BS plays an important role in correction of impaired lipid processing due to insulin resistance by inducing weight loss and improving insulin dependent glucose uptake. Hyperlipidemia improved in 70% of BS patients with a decline in TC, LDL and TG and increase in HDL [31, 64].

The SOS study reported an improvement in lipid profile of post-BS patients, with an increase in HDL concentrations by 18.7% and decrease in TG by 29.9% in the surgical vs. control group [49]. Garcia-Marirrodriga et al. found a positive impact of BS in patients undergoing RYGB with a decline in TC, LDL and TG and significant increase in HDL levels. There was a direct correlation between the improvement in lipid profile and extent of EWL [65].

RCTS including study by Mingrone et al., STAMPEDE trial and the Diabetes Surgery Study found a decrease in TG and increase in HDL but no significant difference in LDL concentrations with BS as compared to medical therapy [52, 59, 61].

A meta-analysis of RCTs for bariatric surgery by Gloy et al. found no difference in mean change in total cholesterol from pooled data from RCTs between BS and non-surgical arms (mean difference −0.4 mmol/L (−0.8 to 0.00), P=0.05)[54].

The positive effects of BS on lipid profile can be explained by the direct response to weight loss as well as changes is neuroendocrine hormones such as GLP1, PYY and ghrelin.

Bariatric surgery and Macrovascular complications of Diabetes

Hypertension, CV disease and peripheral vascular disease are the major macrovascular complications of type 2 DM. Obesity has been related to the development of hypertension and CV disease which is attributed to metabolic derangement seen with obesity.

• Hypertension

Hypertension has a strong association with obesity and approximately 1% body weight loss can improve systolic BP by 1 mm hg and diastolic BP by 2 mm Hg [7].Patients with hypertension had improvement in their BP in 79% of the cases and complete resolution in 61% of cases after BS [27].

The SOS study had mixed results regarding effects of BS on hypertension. BS patients showed an improvement in BP at 1 year, followed by progressive rise over the consequent years which was thought to be associated to increasing age and weight gain [66, 7]. Meta-analysis by Wilhelm et al. showed a significant benefit in obese patients undergoing BS with BP improvement reported in 63% and resolution in 50% of patients [67]

The study by Mingrone et al., the STAMPEDE trial and the Diabetes Surgery Study in DM2 patients undergoing BS vs. medical therapy did not show any significant difference in blood pressure between the two groups, but there was a notable decrease in the number of anti-hypertensive medications [52,59, 61].

There is a complex association between BS and the effects it has on hypertension, which can be confounded by other variable such as age, degree of weight loss, weight regain and other co-morbidities.

• Cardiovascular (CV) disease

Obesity has an association with impaired heart function which may be due to left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction or early atherosclerosis leading to ischemic heart disease. It is also an independent risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Weight loss has been associated with improvement in CV risk. Vogel et al. estimated a CV risk reduction from 6 to 4 % after BS [68].

The SOS study reported a decrease in CV events and CV mortality in patients undergoing BS as compared to control group [49]. The STAMPEDE trial showed a significant decrease in the high-sensitivity CRP level and need for cardiovascular medication [52].The Utah obesity study showed a lower coronary calcium score at 5 years in post-BS patients as compared to conventional therapy group [69].

This suggests that BS can over time delays the progression of atherosclerosis. These findings can be attributed to the overall improvement in metabolic profile of these patients and improvement in the obesity related pro-inflammatory state and CV risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Bariatric surgery and Microvascular complications of Diabetes

Traditionally hypertension and glycemic control are key determinants of the development of diabetes associated microvascular complications that include diabetic nephropathy, neuropathy and retinopathy. Even though observational studies have shown some association between BS and microvascular complications, the RCTS comparing surgery to medical therapy for DM thus far have not establish a significant impact of BS in improving microvascular complications or delaying the progression of microvascular disease with DM.

• Diabetic Nephropathy

Diabetic nephropathy affects 40 % of patients with DM2 and the conventional therapy for this is aimed at improving BP control, blood sugar control and hyperlipidemia [70]. Observational studies by Iaconelli et al. and Miras et al. showed an improvement in albuminuria with weight loss surgery. RYGB was associated with decrease in proteinuria in prospective studies. The STAMPEDE trial did not show any benefit of BS on development of albuminuria as compared to the intensive medical therapy [53]. There was no significant difference in the serum creatinine level and the estimated glomerular filtration rate between the two groups.

• Diabetic Retinopathy (DR)

The effect of BS on diabetic retinopathy was studied in the STAMPEDE trial which concluded that diabetic retinopathy did not significantly differ between the BS arm and the control arm at 2 years [63]. A recent meta-analysis raised the concern for worsening of diabetic retinopathy post-BS [71]. The study reported that patients without retinopathy prior to BS did not progress in 92.5% of cases while those with pre-operative disease remained stable in 57.4%, progressed in 23.5 % and improved in 19.2%.

• Diabetic Neuropathy

Müller-Stich et al. evaluated the role of BS in type 2 DM on diabetic neuropathy in DiaSurg 1 study. They found a significant improvement in Neuropathy symptom score with a 67% reversal in symptomatic neuropathy [72]. There is a need for multicenter RCT to better delineate the effect of bariatric procedures on cardiometabolic and microvascular complications of DM2. The Alliance for Randomized Medication vs. Metabolic Surgery will aim to do this. Prevention and Treatment of Diabetes Complications with Gastric Surgery or Intensive Medicines (PRODIGIES) trial is an ongoing trial which may shed light on this issue (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01974544).

Bariatric Surgery Associated Adverse Events and Complications

The mortality associated with bariatric procedures has been reported as 0.28% at 30 days after surgery and 0.35% between 30 days and 2 years post-procedure [73]. The Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery showed a similar mortality rate of 0.3% at 30 days [74]. The SOS study reported that bariatric surgery was associated with a lower overall mortality in the BS group (Hazard ratio 0.76) as compared to the conventional treatment group (Hazard ratio 0.71) [48]. There was a need for reoperation due to bleeding, gastric leaks and small bowel obstruction was seen in 8% BS patients in RCTs [52, 59, 61]

Major surgical complications (i.e. DVTs, infection, gastric leaks, fistulas, small bowel obstruction) are seen in 5–40% of cases and occur more commonly in smokers and DM [74, 75]. Many (30–70%) post-bariatric surgery patients suffer from nutritional deficiencies with anemia being the most common that may necessitate iron infusion therapy [76]. Reactive hypoglycemia is another complication seen with these procedures hypothesized to be due to exaggerated post-prandial insulin response to GLP-1 or from nesidioblastosis [77]. Post-bariatric surgery hypoglycemia syndrome is rare but can be debilitating. The exact pathophysiology is variable and management, including reversal of the surgery, can be challenging.

Conclusion

Diabetes and obesity not only coexist, but promote and exacerbate each other. Weight gain leads to increased insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia and a progressive decline in beta-cell function. Insulin analogs and oral hypoglycemic therapies (i.e. sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones) further weight gain and thwart lifestyle modification. BS has shown to be superior to conventional methods for durable weight loss. BS has also shown to have an overall mortality benefit in severe obesity and has favorable effects on metabolic parameters and comorbidities such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular risk and glycemic control in diabetes. Thus far, randomized control trials of bariatric surgery vs. medical therapy for diabetes have documented superior efficacy of surgical weight loss to produce diabetes remission and improve quality of life. The long-term effects of BS on diabetes complications remain unanswered. Thus, monitoring for glycemic control and serial surveillance remains the treatment of choice for prevention and delaying the progression of diabetes related vascular complications.

Key Points.

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are closely inter-related; excess adiposity leads to inflammation, insulin resistance and beta cell failure in predisposed individuals.

Currently, bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for obesity and results in long-term weight loss and improvement in metabolic profile and obesity related complications.

Bariatric surgery leads to significant improvement in glycemic control and metabolic syndrome components through weight loss but benefits for micro/macro vascular complications of diabetes remain unclear.

Long-term risk for nutritional deficiencies, osteoporosis/bone fractures and various surgical complications need to be considered for individual patient management.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to disclose

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Death and Mortality. NCHS FastStats Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm.

- 2.Gerteis J, Izrael D, Deitz D, et al. Multiple Chronic Conditions Chartbook. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. AHRQ Publications No, Q14–0038. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Diabetes Statistics Report. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden C, Carroll M, Kit B, Flegal K. Prevalence of Childhood and Adult Obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. Survey of Anesthesiology. 2014;58(4):206. doi: 10.1097/01.sa.0000451505.72517.a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flegal K, Carroll M, Kit B, Ogden C. Prevalence of Obesity and Trends in the Distribution of Body Mass Index Among US Adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan J, Rimm E, Colditz G, Stampfer M, Willett W. Obesity, Fat Distribution, and Weight Gain as Risk Factors for Clinical Diabetes in Men. Diabetes Care. 1994;17(9):961–969. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noria S, Grantcharov T. Biological effects of bariatric surgery on obesity-related comorbidities. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2013;56(1):47–57. doi: 10.1503/cjs.036111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel A, Hildebrand J, Gapstur S. Body Mass Index and All-Cause Mortality in a Large Prospective Cohort of White and Black U.S. Adults. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e109153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen M, Ryan D, Apovian C, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Circulation. 2013;129(25 suppl 2):S102–S138. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ionut V, Bergman R. Mechanisms Responsible for Excess Weight Loss after Bariatric Surgery. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2011;5(5):1263–1282. doi: 10.1177/193229681100500536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obesity and overweight. Geneva (Switzerland): World health organization; Fact sheet no 311. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenney R, Short D. Tipping the Balance: the Pathophysiology of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2011;91(6):1139–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mantzoros C. Obesity And Diabetes. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung R. Obesity as a disease. British Medical Bulletin. 1997;53(2):307–321. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colditz G. Weight Gain as a Risk Factor for Clinical Diabetes Mellitus in Women. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1995;122(7):481. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-7-199504010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westlund K, Nicolayson R. A ten year mortality and morbidity study related to serum cholesterol. A follow-up of 3751 men aged 40–49. Scand J Lab Invest. 1972;30(Suppl 127):1– 24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson D, Pamuk E, Thun M, Flanders D, Byers T, Heath C. Prospective Study of Intentional Weight Loss and Mortality in Overweight White Men Aged 40–64 Years. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;149(6):491–503. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wing RR, Shoemaker M, Marcus MDM, McDermott M, Gooding W. Variables associated with weight loss and improvements in glycaemic control in type 2 diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med. 1990;147:1749–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reisin E, Abel R, Modan M, Silverberg D, Eliahou H, Modan B. Effect of Weight Loss without Salt Restriction on the Reduction of Blood Pressure in Overweight Hypertensive Patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 1978;298(1):1–6. doi: 10.1056/nejm197801052980101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Datnlo AM, Kris-Etherton PM. Effects of weight reduction on blood lipids and lipoproteins: a meta analysis. Am J Gin Nutr. 1992;56:320–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes with Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reduction in Weight and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes: One-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forsythe L, Wallace J, Livingstone M. Obesity and inflammation: the effects of weight loss. Nutrition Research Reviews. 2008;21(02):117. doi: 10.1017/s0954422408138732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Expert panel report: Guidelines (2013) for the management of overweight and obesity in adults. Obesity. 2014;22(S2):S41–S410. doi: 10.1002/oby.20660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugerman H. The ASBS Consensus Conference on the state of bariatric surgery and morbid obesity: Health implications for patients, health professionals and third-party payors. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2005;1(2):105. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26*.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric Surgery. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27*.Colquitt J, Picot J, Loveman E, Clegg A. Surgery for obesity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(2):CD003641-CD003641. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003641.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh A, Kota S, Singh R. Bariatric surgery and diabetes remission: Who would have thought it? Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2015;19(5):563. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.163113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Bariatric Surgery Procedures - ASMBS. 2016. [Accessed February 13, 2016]. Available at: https://asmbs.org/patients/bariatric-surgery-procedures.

- 30.Parikh M, Fielding G, Ren C. U.S. experience with 749 laparoscopic adjustable gastric bands: intermediate outcomes. Surgical Endoscopy. 2005;19(12):1631–1635. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. Weight and Type 2 Diabetes after Bariatric Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. The American Journal of Medicine. 2009;122(3):248–256. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karra E, Yousseif A, Batterham RL. Mechanisms Facilitating Weight Loss And Resolution Of Type 2 Diabetes Following Bariatric Surgery. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;21(6):337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.01.006. Web. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubino F, R'bibo S, del Genio F, Mazumdar M, McGraw T. Metabolic surgery: the role of the gastrointestinal tract in diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6(2):102–109. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ponce J, Haynes B, Paynter S, Fromm R, Lindsey B, Shafer A, Manahan E, Sutterfield C. Effect of lap-band-induced weight loss on type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Obesity Surg. 2004;14(10):1335–1342. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halmi KA, Mason E, Falk JR, Stunkard A. Appetitive behavior after gastric bypass for obesity. Int J Obes. 1981;5:457–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isbell J, Tamboli R, Hansen E, et al. The Importance of Caloric Restriction in the Early Improvements in Insulin Sensitivity After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1438–1442. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchwald H, Oien D. Metabolic/Bariatric Surgery Worldwide 2008. Obesity Surgery. 2009;19(12):1605–1611. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evans J, Goldfine I, Maddux B, Grodsky G. Are Oxidative Stress-Activated Signaling Pathways Mediators of Insulin Resistance and -Cell Dysfunction? Diabetes. 2003;52(1):1–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marceau P, Hould FS, Simard S, Lebel S, Bourque RA, Potvin M, Biron S. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. World J Surg. 1998;22(9):947–954. doi: 10.1007/s002689900498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brolin R. Malabsorptive Gastric Bypass in Patients With Superobesity. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2002;6(2):195–205. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cummings D. Endocrine mechanisms mediating remission of diabetes after gastric bypass surgery. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2009;33:S33–S40. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kindel T, Yoder S, Seeley R, D’Alessio D, Tso P. Duodenal-Jejunal Exclusion Improves Glucose Tolerance in the Diabetic, Goto-Kakizaki Rat by a GLP-1 Receptor-Mediated Mechanism. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2009;13(10):1762–1772. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0912-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laferrère B. Effect of gastric bypass surgery on the incretins. Diabetes & Metabolism. 2009;35(6):513–517. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(09)73458-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holst J, Vilsboll T, Deacon C. The incretin system and its role in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2009;297(1–2):127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samat A, Malin S, Huang H, Schauer P, Kirwan J, Kashyap S. Ghrelin suppression is associated with weight loss and insulin action following gastric bypass surgery at 12 months in obese adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(10):963–966. doi: 10.1111/dom.12118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kashyap S, Bhatt D, Wolski K, et al. Metabolic Effects of Bariatric Surgery in Patients With Moderate Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: Analysis of a randomized control trial comparing surgery with intensive medical treatment. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2175–2182. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cummings D, Weigle D, Frayo R, et al. Plasma Ghrelin Levels after Diet-Induced Weight Loss or Gastric Bypass Surgery. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(21):1623–1630. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa012908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström C, et al. Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Mortality in Swedish Obese Subjects. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(8):741–752. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Bariatric Surgery and Long-term Cardiovascular Events. JAMA. 2012;307(1):56. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50*.Ribaric G, Buchwald J, McGlennon T. Diabetes and Weight in Comparative Studies of Bariatric Surgery vs Conventional Medical Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obesity Surgery. 2013;24(3):437–455. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1160-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51*.Gill R, Birch D, Shi X, Sharma A, Karmali S. Sleeve gastrectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2010;6(6):707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schauer P, Kashyap S, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric Surgery versus Intensive Medical Therapy in Obese Patients with Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(17):1567–1576. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1200225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schauer P, Bhatt D, Kirwan J, et al. Bariatric Surgery versus Intensive Medical Therapy for Diabetes — 3-Year Outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(21):2002–2013. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1401329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54*.Gloy V, Briel M, Bhatt D, et al. Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2013;347(oct22 1):f5934–f5934. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pories W, Card J, Flickinger E, Meelheim H, Swanson M. The Control of Diabetes Mellitus (NIDDM) in the Morbidly Obese with the Greenville Gastric Bypass. Annals of Surgery. 1987;206(3):316–323. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198709000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pories W, Swanson M, MacDonald K, et al. Who Would Have Thought It? An Operation Proves to Be the Most Effective Therapy for Adult-Onset Diabetes Mellitus. Annals of Surgery. 1995;222(3):339–352. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sjostrom C, Peltonen M, Wedel H, Sjostrom L. Differentiated Long-Term Effects of Intentional Weight Loss on Diabetes and Hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;36(1):20–25. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schauer P, Burguera B, Ikramuddin S, et al. Effect of Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2004;19(1):60–61. doi: 10.1177/011542650401900160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric Surgery versus Conventional Medical Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(17):1577–1585. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1200111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric–metabolic surgery versus conventional medical treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: 5 year follow-up of an open-label, single-centre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2015;386(9997):964–973. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ikramuddin S, Korner J, Lee W, et al. Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass vs Intensive Medical Management for the Control of Type 2 Diabetes, Hypertension, and Hyperlipidemia. JAMA. 2013;309(21):2240. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maraka S, Kudva Y, Kellogg T, Collazo-Clavell M, Mundi M. Bariatric surgery and diabetes: Implications of type 1 versus insulin-requiring type 2. Obesity. 2015;23(3):552–557. doi: 10.1002/oby.20992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.TorquatiI A, Lutfi R, Abumrad N, Rirchards W. Is Roux-en- Gastric Bypass Surgery the Most Effective Treatment for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Morbidly Obese Patients? Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2005;9(8):1112–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bouldin M, Ross L, Sumrall C, Loustalot F, Low A, Land K. The Effect of Obesity Surgery on Obesity Comorbidity. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2006;331(4):183–193. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200604000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garcia-Marirrodriga I, Amaya-Romero C, Ruiz-Diaz G, et al. Evolution of Lipid Profiles after Bariatric Surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2011;22(4):609–616. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0534-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sjöström C, Peltonen M, Sjöström L. Blood Pressure and Pulse Pressure during Long-Term Weight Loss in the Obese: The Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) Intervention Study. Obesity Research. 2001;9(3):188–195. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67*.Wilhelm S, Young J, Kale-Pradhan P. Effect of Bariatric Surgery on Hypertension: A Meta-analysis. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2014;48(6):674–682. doi: 10.1177/1060028014529260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Benraouane F, Litwin S. Reductions in cardiovascular risk after bariatric surgery. Current Opinion in Cardiology. 2011;26(6):555–561. doi: 10.1097/hco.0b013e32834b7fc4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Priester T, Ault T, Davidson L, et al. Coronary Calcium Scores 6 Years After Bariatric Surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2014;25(1):90–96. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1327-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Docherty N, le Roux C. Improvements in the metabolic milieu following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and the arrest of diabetic kidney disease. Exp Physiol. 2014;99(9):1146–1153. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2014.078790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71*.Cheung D, Switzer N, Ehmann D, Rudnisky C, Shi X, Karmali S. The Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Diabetic Retinopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obesity Surgery. 2014;25(9):1604–1609. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1539-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Müller-Stich B, Fischer L, Kenngott H, et al. Gastric Bypass Leads to Improvement of Diabetic Neuropathy Independent of Glucose Normalization—Results of a Prospective Cohort Study (DiaSurg 1 Study) Annals of Surgery. 2013;258(5):760–766. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3182a618b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73*.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Sledge I. Trends in mortality in bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery. 2007;142(4):621–635. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perioperative Safety in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(5):445–454. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa0901836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Encinosa W, Bernard D, Du D, Steiner C. Recent Improvements in Bariatric Surgery Outcomes. Medical Care. 2009;47(5):531–535. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e31819434c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Davies D, Baxter J, Baxter J. Nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2007;17(9):1150–1158. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goldfine A, Mun E, Devine E, et al. Patients with Neuroglycopenia after Gastric Bypass Surgery Have Exaggerated Incretin and Insulin Secretory Responses to a Mixed Meal. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2007;92(12):4678–4685. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]