Abstract

Background

Multiple yeast species can cause human disease, involving superficial to deep‐seated infections. Treatment of these infections depends on the accurate identification of causative agents; however, reliable methods are not available in many laboratories, especially not in resource‐limited settings. Here, a new multiplex assay for rapid and low‐cost identification of pathogenic yeasts is described.

Methods

A two‐step multiplex assay named YEAST PLEX that comprises of four tubes and identifies 17 clinically important common to rare yeasts was designed and evaluated. The set also provides PCR amplicon of unidentified species for direct sequencing. The specificity of YEAST PLEX was tested using 28 reference strains belonging to 17 species and 101 DNA samples of clinically important non‐target bacteria, parasites, and fungi as well as human genomic DNA. The method was further analyzed using 203 previously identified and 89 unknown clinical yeast isolates. Moreover, the method was tested for its ability to identify mixed yeast colonies by using 18 mixed suspensions of two or three species.

Results

YEAST PLEX was able to identify all the target species without any non‐specific PCR products. When compared to PCR‐sequencing/MALDI‐TOF, the results of YEAST PLEX were in 100% agreement. Regarding the 89 unknown clinical isolates, random isolates were selected and subjected to PCR‐sequencing. The results of sequencing were in agreement with those of YEAST PLEX. Furthermore, this method was able to correctly identify all yeasts in mixed suspensions.

Conclusion

YEAST PLEX is an accurate, low‐cost, and rapid method for identification of yeasts, with applicability, especially in developing countries.

Keywords: Candida, identification, multiplex PCR, yeasts

YEAST PLEX assay is able to directly identify 17 yeast species in two steps (four tubes) and provide PCR amplicon for sequencing for uncovered species.

1. INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of opportunistic fungal diseases, including those caused by yeast infections, has been soaring in recent decades as a result of an increasing number of susceptible patients. 1 Candida species are the third or fourth most common causes of healthcare‐associated infections with a mortality of up to 40%. 2 Candida albicans is still the leading human pathogenic Candida species; however, during the last two decades, non‐C. albicans species such as Candida glabrata, Candida krusei, Candida dubliniensis, Candida lusitaniae, Candida auris, and a list of other uncommon species have emerged and attracted attention as causes of deep‐seated infections. 3 , 4 Together, these rare species may account for 10% of infections in some medical centers. 5 Emerging species such as C. auris can cause hospital outbreaks, the management of which could be difficult because of environmental persistence and the antifungal resistance of C. auris. 6 , 7 , 8 Moreover, other non‐Candida yeasts, including members of the genera Cryptococcus, Trichosporon, Rhodotorula, and Saccharomyces, have also been reported to cause life‐threatening infections and to be resistant to antifungal drugs. 9 , 10

Rapid and accurate identification of yeast isolates is essential for the management and control of nosocomial infections 11 not only because of differences in antifungal susceptibility profile, prognosis, and medical intervention, 12 but also because of surveillance. 13 Apart from physiology‐based methods for identification of yeasts, which are expensive, time‐consuming, and laborious, and which may lead to inconclusive results, 14 several molecular methods have been introduced to identify medically important yeast species. Although DNA sequencing of validated targets is the gold standard approach for accurate identification of fungi, 12 , 15 this option is not available in the majority of laboratories, especially in resource‐limited settings. 16 Other molecular methods, such as specific PCR, nested PCR, 13 PCR‐RFLP, 17 , 18 probe‐based 19 , 20 or SYBR green‐based real‐time PCR, 21 , 22 multiplex PCR or real‐time PCR, 23 , 24 , 25 and microarray techniques, 26 have been introduced for identification of fungi. Each method has its own pros and cons, with most enabling the identification of a limited number of species. Recently, matrix‐assisted laser desorption/ionization time‐of‐flight mass spectrometry (MALDI‐TOF MS) was identified as a rapid, reliable, and high‐throughput diagnostic tool applicable to clinical microbiology, allowing identification of bacterial and fungal isolates within minutes 27 , 28 ; however, this diagnostic approach requires expensive instruments, making it unaffordable in some laboratories. Although a multiplex PCR method for identification of a wide range of medically important yeast species was recently introduced with promising results, 25 the need for further methods is still obvious to provide a range of different options. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to develop a rapid, easy, and low‐cost method for identification a wide range of common and rare pathogenic yeasts using a multiplex PCR approach as an affordable method, especially applicable to resource‐limited settings.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Yeast strains

A set of 28 reference strains of the most clinically important genera and species, including Candida spp., Cryptococcus neoformans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Trichosporon spp., and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, were used as positive controls for evaluating the validity and specificity of the method (Table 1). In addition, 101 DNA samples representing clinically important non‐target bacteria, parasites, and fungi, as well as human genomic DNA, were used as negative controls (Table 1). Reference yeast strains were cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA, Biolife, Italy) and incubated at 35 °C for 1–3 days. DNA was extracted from yeast colonies using glass bead disruption followed by purification using a nucliSENS easyMAG instrument (bioMérieux) and used as the template for specificity testing of the designed primers and for developing the multiplex PCR.

TABLE 1.

Detailed features of the primers, target genes, product sizes, and the relevant positive and negative controls used in the designing and development of YEAST PLEX system

| Tube | Target species | Primers | Target | Amplicon size (bp) | Positive controls | Negative controls a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Candida albicans b | F: GCACCACATGTGTTTTTCTTTGAA | ITS | 417 |

C. albicans CBS 705 C. albicans CBS 710 C. albicans ATCC 64553 C. albicans (Clinical isolate 39) C. albicans (Clinical isolate 72) |

Candida albicans CBS 705 Candida albicans CBS 710 Candida albicans ATCC 64553 Candida albicans (n = 2) c Candida dubliniensis ATCC 2018 Candida dubliniensis (n = 3) Candida parapsilosis CBS 711 Candida parapsilosis (n = 4) Candida metapsilosis ATCC 5904 Candida metapsilosis (n = 1) Candida orthopsilosis (n = 4) Candida famata CBS 353 Candida famata (n = 3) Candida auris ATCC 8037 Candida auris ATCC 8033 Candida auris (n = 2) Candida glabrata CBS 630 Candida glabrata CBS 635 Candida glabrata ATCC 90030 Candida glabrata (n = 2) Candida kefyr (n = 2) Candida krusei CBS 868 Candida krusei (n = 5) Candida tropicalis CBS 629 Candida tropicalis CBS 94 Candida tropicalis (n = 3) Candida guilliermondii CBS 798 Candida guilliermondii CBS 935 Candida guilliermondii (n = 2) Candida rugosa CBS 817 Candida rugosa (n = 1) Candida intermedia (n = 1) Candida lusitaniae CBS 634 Candida lusitaniae (n = 4) Candida norvegensis ATCC 1537 Candida inconspicua ATCC 1538 Cryptococcus neoformans CBS 636 Cryptococcus neoformans (n = 1) Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (n = 2) Trichosporon sp. (n = 5) Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATCC 2748 Saccharomyces cerevisiae (n = 1) Geotrichum sp. (n = 4) Aspergillus flavus (n = 2) Aspergillus niger (n = 2) Aspergillus terreus (n = 2) Aspergillus tubingensis (n = 2) Trichophyton rubrum CBS 100237 Trichophyton schoenleinii CBS434.63 Blastocystis sp. (n = 1) Toxoplasma gondii (n = 1) Leishmania major (n = 1) Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 2) Escherichia coli (n = 1) Salmonella sp. (n = 1) Bacillus subtilis (n = 1) Klebsiella sp. (n = 1) Enterobacteriaceae (n = 1) Staphylococcus aureus (n = 2) Homo sapiens (human DNA; n = 4) |

| R: TGGTGGACGTTACCGCCG | ||||||

| Candida dubliniensis | F: ACCACATGTGTTTTGTTCTGG | ITS | 357 |

C. dubliniensis ATCC 2018 C. dubliniensis (Clinical isolate 221) C. dubliniensis (Clinical isolate 390) |

||

| R: TCCGCCTTATACCACTATCA | ||||||

| Candida parapsilosis b | F: GTAGGCCTTCTATATGGGGC | ITS | 308 |

C. parapsilosis CBS 711 C. parapsilosis (Clinical isolate 30) C. parapsilosis (Clinical isolate 32) C. parapsilosis (Clinical isolate 115) |

||

| R: GTTTATACTCCGCCTTTCTTTC | ||||||

| Candida auris | F: AACTAACCCAACGTTAAGTTCAAC | ITS | 282 |

C. auris ATCC 8033 C. auris ATCC 8037 C. auris (Clinical isolate 40) C. auris (Clinical isolate 1020) |

||

| R: CGACAACAAAACGAAAAAAAAAGCG | ||||||

| Candida glabrata | F: TCTCTGCTGTGAATGCCAT | ITS | 230 |

C. glabrata CBS 630 C. glabrata CBS 635 C. glabrata ATCC 90030 C. glabrata (Clinical isolate 45) |

||

| R: ACTCCCCCCCGAAAGAGA | ||||||

| Candida kefyr | F: TCGTCTCGGGTTAACTTGA | ITS | 201 |

C. kefyr (Clinical isolate 189) C. kefyr (Clinical isolate 400) |

||

| R: GTTTTGGTTAAAGCCGTATGCCTCA | ||||||

| Candida krusei | F: TTGCGCGTGCGCAGAGTTG | ITS | 150 |

C. krusei CBS 868 C. krusei (Clinical isolate 22) |

||

| R: GTTGTCTCGCAACACTCGCT | ||||||

| Candida tropicalis | F: TATAGTCGATCTCCTCCCACAG | IGS | 128 |

C. tropicalis CBS 629 C. tropicalis CBS 94 C. tropicalis (Clinical isolate 230) C. tropicalis (Clinical isolate 240) |

||

| R: CCATAAAAATACCCTTCGGAATGC | ||||||

| B | Candida guilliermondii | F: TACAAACAATGTGTAATGAACG d | ITS | 340 |

C. guilliermondii CBS 798 C. guilliermondii CBS 935 C. guilliermondii (Clinical isolate 758) |

|

| R: TGTTTGGTTGTTGTAAGGC | ||||||

| Candida rugosa | F: TACAAACAATGTGTAATGAACG d | ITS | 238 |

C. rugosa CBS 817 C. rugosa (Clinical isolate 21) |

||

| R: GATCGTGAGTCTGTAACAAGCT | ||||||

| Candida intermedia | F: TACAAACAATGTGTAATGAAC c | ITS | 214 | C. intermedia (Clinical isolate 403) | ||

| R: AGTTGAAGTAACGTATTGCGACAA | ||||||

| Candida lusitaniae | F: TACAAACAATGTGTAATGAACG d | ITS | 174 |

C. lusitaniae CBS 634 C. lusitaniae (Clinical isolate 321) C. lusitaniae (Clinical isolate 806) |

||

| R: AGCAACGCCTAACCGGGGGTTA | ||||||

| Candida norvegensis | F: AGACGACTCCAGAACCCTGA | IGS | 141 | C. norvegensis ATCC 1537 | ||

| R: CACGTGAAAAAGGCGTGACTT | ||||||

| C | Cryptococcus neoformans | F: TTGGACTTTGGTCCATTTATCTACC | ITS | 391 |

Cryptococcus neoformans CBS 636 Cryptococcus neoformans (Clinical isolate 11) |

|

| R: GGCTGACAGGTAATCACCTT | ||||||

| Rhodotorula mucilaginosa | F: GAGAGCGAACTCCTATTCACTTAT | 18S | 314 |

Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (Clinical isolate 10) Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (Clinical isolate 20) |

||

| R: TGCATTACGAACGAGCTAGACC | ||||||

| Trichosporon spp. | F: TACAAACAATGTGTAATGAACG | ITS | 229 |

Trichosporon (Clinical isolate 20) Trichosporon (Clinical isolate 25) |

||

| R: CCATTARGAAACCCTAGT | ||||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | F: GCCTGCGCTTAAGTGCGCGGTCTT | ITS | 119 |

Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATCC 2748 Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Clinical isolate 18) |

||

| R: GTGTGTTGTATTGAAACGGTTT | ||||||

For each primer set, the target species was deleted from the list of negative controls; for example, for C. albicans‐specific primers, C. albicans was deleted from the list.

Primer sets for Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis were selected from a previous study

Regarding the clinical isolates, only the number of the isolates is shown.

Forward primers are shared between Candida guilliermondii, Candida rugosa, Candida intermedia and Candida lusitaniae.

A total of 292 yeast isolates comprising various genera and species previously isolated from various clinical specimens (mainly blood, bronchoalveolar lavage, cerebrospinal fluid, and urine; Table S1) were tested for validation of the assay performance and reproducibility and for comparing the results with those of other methods. Of these yeasts, 203 isolates had already been identified using MALDI‐TOF MS and/or PCR‐sequencing in a previous study, 29 and 89 represented unknown species. Following sufficient growth on SDA plates, DNA was extracted from the clinical isolates using the boiling method. 30 Briefly, colonies were suspended into 50 μl sterile distilled water and boiled for 20 min and centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min; the supernatants were used as DNA template.

2.2. Primer designing and specificity testing

The use of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the ribosomal cistron confers the highest probability of successful identification for a broad range of fungi, including yeasts, with the most clearly defined barcode gap between inter‐ and intraspecific variation. 31 Therefore, considering the various phylogenetic and taxonomic features of the ITS region, this marker was chosen for designing species‐specific primers. The exceptions were Candida tropicalis and Candida norvegensis, and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, in which the intergenic spacer (IGS) region and 18S rDNA were used as the target for primer designing, respectively. Primer pairs, except for Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis which were selected from a previous study, 32 were designed using the Geneious Prime software (https://www.geneious.com) by applying a maximum product size limit of 500 bp. Appropriate care was taken to ensure having the primer pairs with similar annealing temperatures to avoid false‐negative results, to reduce the risk of unspecific amplification and to avoid cross‐reaction with other species. To identify any non‐specific binding sites and to anticipate the specificity of the PCR assay, the selected oligonucleotides (Table 1) were evaluated using Primer‐BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer‐blast/). Furthermore, PCR was carried out for each set of primers using a panel of non‐target fungal/non‐fungal DNAs (Table S1).

2.3. Multiplex PCR (YEAST PLEX)

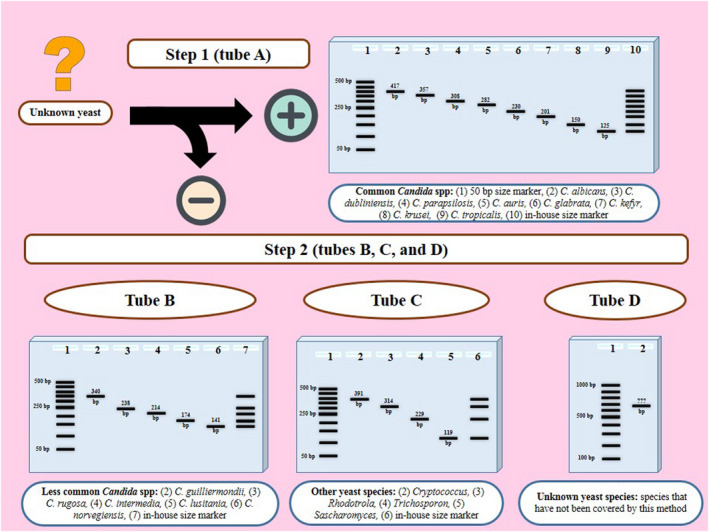

After evaluating the primer pairs in single‐plex reactions, multiplex PCR assays were optimized regarding the annealing temperature (56–62°C), primer concentration (0.2–1 μM), and MgCl2 concentration (1.5–2.5 M; Table S2). For species identification of the yeasts, a stepwise multiplex PCR (referred to as YEAST PLEX) was designed, which included two steps: In the first step, one tube (tube A) was used for identification of eight common species, and in the second step, three tubes (tubes B, C, and D) were used for identification of nine species (Figure 1, Table 1). If the result of tube A was negative, DNA was subjected to tubes B, C, and D, simultaneously. Unlike the tubes A, B, and C, which involve multiplex reactions, tube D is a pan‐fungal single‐plex reaction, which serves as a positive control to exclude personal and technical errors, enabling the generation of PCR amplicons for rare yeasts not covered by tubes A, B, and C. Such amplicons could be used directly for sequencing.

FIGURE 1.

Workflow of the YEAST PLEX assay for identification of unknown yeast isolates and the schematic results after agarose gel electrophoresis. The assay includes two steps: Step 1 (tube A) is used for identification of 8 species, and step 2 (tubes B, C, and D) is used for identification of 9 species. Regarding the species that are not covered in YEAS PLEX, tube D provides a PCR amplicon for direct sequencing

2.4. Preparation of an in‐house size marker for yeast identification

To develop a reliable interpretation of the electrophoresis results obtained by tubes A, B, and C, three tube‐specific in‐house size markers were prepared by mixing the PCR products of the single‐plex PCRs. Thus, in addition to the standard commercial 50‐bp size marker, positive PCR products of eight control species designated to be identified in tube A, were mixed to be used as a specific size marker; the same procedure was applied to tubes B and C. For the identification of each yeast, an aliquot of 5 µl of the PCR products was electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel containing 5 µg/ml ethidium bromide and visualized using an UV transilluminator; the fragment size was compared with the in‐house tube‐specific size marker and the commercial 50‐bp size marker.

2.5. Comparing YEAST PLEX method with sequencing/MALDI‐TOF MS

The YEAST PLEX method was further evaluated by comparing its results for 203 clinical yeast isolates with the results previously obtained by Sanger sequencing and/or MALDI‐TOF MS. Moreover, 89 unknown isolates were first identified using the YEAST PLEX assay, and subsequently, the results for some randomly selected isolates from each species were compared with sequence analysis of the ITS1‐5.8S rDNA‐ITS2 region. 33 Furthermore, all isolates with inconclusive results in the YEAST PLEX; that is, isolates that are not covered by this method, were subjected to sequencing.

2.6. Evaluating the YEAST PLEX method for identification of mixed yeasts

To evaluate the applicability of the YEAST PLEX assay for the identification of yeasts in the mixed cases, 18 suspensions were prepared by mixing colonies of various species. These species were selected either from the same or from different tubes and either by mixing two or three species (Table 2). Mixed samples were subjected to YEAST PLEX assay without any modifications of the method.

TABLE 2.

Details of the 18 mixed yeast suspensions tested by the YEAST PLEX method

| N of samples | Mixed yeast suspension | Correct identification by YEAST PLEX? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Tubes | ||

| 2 | Candida albicans + Candida glabrata | A + A | Yes |

| 2 | Candida albicans + Candida tropicalis | A + A | Yes |

| 2 | Candida krusei + Candida tropicalis | A + A | Yes |

| 1 | Candida albicans + Candida parapsilosis | A + A | Yes |

| 1 | Candida parapsilosis + Candida auris | A + A | Yes |

| 1 | Candida intermedia + Candida lusitaniae | B + B | Yes |

| 1 | Candida guilliermondii + Candida norvegensis | B + B | Yes |

| 1 | Rhodotorula mucilaginosa + Saccharomyces cerevisiae | C + C | Yes |

| 1 | Trichosporon + Saccharomyces cerevisiae | C + C | Yes |

| 2 | Candida albicans + Candida glabrata + Candida tropicalis | A + A + A | Yes |

| 1 | Candida albicans + Candida parapsilosis + Candida auris | A + A + A | Yes |

| 1 | Candida albicans + Candida glabrata + Candida krusei | A + A + A | Yes |

| 1 | Candida tropicalis + Candida norvegensis + Saccharomyces cerevisiae | A + B + C | Yes |

| 1 | Candida parapsilosis + Candida guilliermondii + Cryptococcus neoformans | A + B + C | Yes |

3. RESULTS

3.1. Design of specific primer sets for species identification

The initial evaluation of primer sets using positive and negative controls in single‐plex PCRs confirmed the specificity of the primers. The primers generated amplicons with expected sizes for target species in tube A (C. albicans: 417 bp; Candida dubliniensis: 357 bp; Candida parapsilosis: 308 bp; C. auris: 282 bp; C. glabrata: 230 bp; Candida kefyr: 201 bp; C. krusei: 150 bp; and C. tropicalis: 128 bp), tube B (Candida guilliermondii: 340 bp; Candida rugosa: 238 bp; Candida intermedia: 214 bp; Candida lusitaniae: 174 bp; and C. norvegensis: 141 bp), and tube C (C. neoformans: 391 bp; R. mucilaginosa: 314 bp; Trichosporon spp: 229 bp, and S. cerevisiae: 119 bp). When they were tested for non‐target controls, no unspecific product was detected.

3.2. Developing the multiplex PCR (YEAST PLEX)

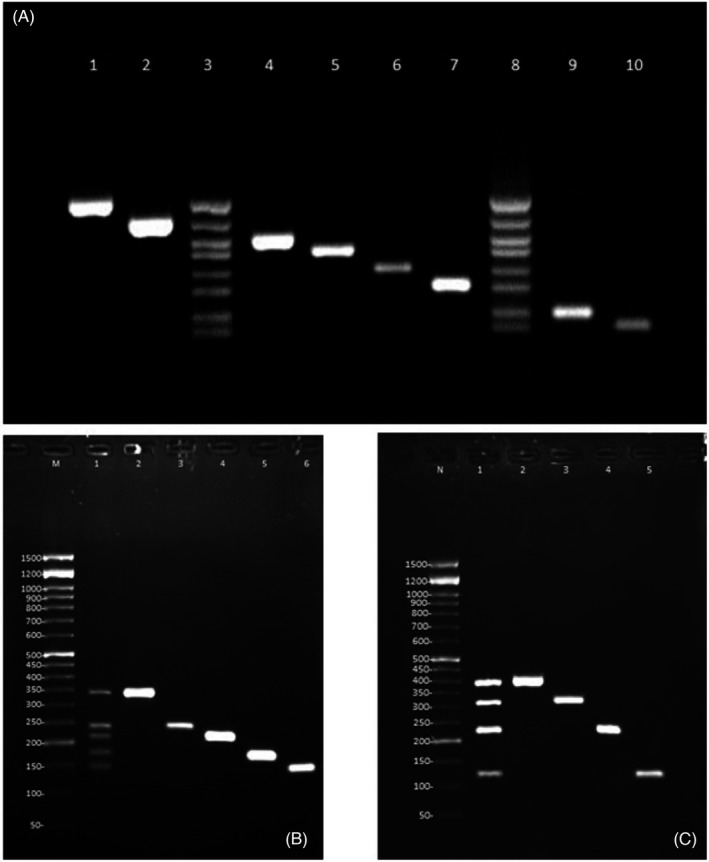

Based on the results obtained by the use of different primer concentrations, MgCl2 concentration, templates, and different annealing temperatures, the best conditions for performing the multiplex reactions were identified (Table S2). Results showed that 0.2–0.6 μM of primers are suitable for the amplification in all tubes, but no significant differences were observed when using different MgCl2 concentrations or annealing temperatures. Moreover, the interpretation of the electrophoresis results generated by YEAST PLEX using the in‐house ITS size marker resulted in accurate identification and faster and easier interpretation of results when compared to using the routine commercial size marker (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Results of the YEAST PLEX assay for tubes A, B, and C. Panel A: Lanes 1: C. albicans, lane 2: C. dubliniensis, lane 3: in‐house size marker, lane 4: C. parapsilosis, lane 5: C. auris, lane 6: C. glabrata, lane 7: C. kefyr, lane 8: in‐house size marker, lane 9: C. krusei, and lane 10: C. tropicalis. Panel B: Lane M: 50‐bp size marker, lane 1: in‐house size marker, lane 2: C. guilliermondii, lane 3: C. rugosa, lane 4: C. intermedia, lane 5: C. lusitaniae, and lane 6: C. norvegensis. Panel C: Lane M: 50‐bp size marker, lane 1: in‐house size marker, lane 2: Cryptococcus, lane 3: Rhodotorula, lane 4: Trichosporon, lane 5: Saccharomyces

3.3. Application of YEAST PLEX for identification of the clinical isolates

Testing of the 292 clinical yeast isolates revealed that YEAST PLEX enables reliable identification of the common isolates. Comparing the results of YEAST PLEX with those of sequencing/MALDI‐TOF MS of the 203 previously identified isolates, all isolates were correctly identified, with an exception of four Candida orthopsilosis isolates, a species which is not covered by the YEAST PLEX. Therefore, as expected for other species that are not covered by YEAST PLEX, for C. orthopsilosis isolates, positive results were obtained with ~500‐bp amplicons in tube D. Interestingly, 5 of the 203 (2.46%) isolates, that is, C. albicans (n = 1), C. parapsilosis (n = 2), C. glabrata (n = 1), and C. kefyr (n = 1), were found to be a mixed isolates of two species (Table 3). Regarding the 89 unknown yeast isolates, 80 were identified as C. albicans (n = 34), C. parapsilosis (n = 23), C. tropicalis (n = 16), Candida lusitaniae (n = 3), C. glabrata (n = 3), and C. auris (n = 1) using YEAST PLEX, and four isolates were identified as unknown species with ~500‐bp amplicons in tube D. The remaining five isolates were found to be a mix of C. glabrata with C. tropicalis (n = 3) and C. glabrata with C. albicans (n = 2). Sequence analysis of 49 randomly selected isolates from different species confirmed the YEAST PLEX results. The four isolates that YEAST PLEX was unable to identify were found to be C. orthopsilosis (n = 2), Candida metapsilosis (n = 1), and Wickerhamomyces anomalus (n = 1).

TABLE 3.

Comparative results of the YEAST PLEX assay with DNA sequencing/MALDI‐TOF MS with regard to the identification of 203 yeast isolates

| DNA sequencing/MALDI‐TOF MS | YEAST PLEX | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | N | Single species a | Mixed | Unknown (amplicon size in tube D) |

| Candida albicans | 109 | 108 | 1 (C. albicans + C. parapsilosis) | – |

| Candida parapsilosis | 54 | 52 | 2 (C. parapsilosis + C. albicans) | – |

| Candida tropicalis | 14 | 14 | – | – |

| Candida lusitaniae | 8 | 8 | – | – |

| Candida glabrata | 7 | 6 | 1 (C. glabrata + C. parapsilosis) | – |

| Candida orthopsilosis | 4 | – | – | 4 (~500 bp) |

| Candida kefyr | 3 | 2 | 1 (C. kefyr + C. parapsilosis) | – |

| Candida guilliermondii | 2 | 2 | – | – |

| Candida dubliniensis | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Candida intermedia | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Total | 203 | 194 | 5 | 4 b |

In agreement with DNA sequencing/MALDI‐TOF MS.

All four isolates were identified as C. orthopsilosis by sequencing of the ITS region.

3.4. Evaluating the YEAST PLEX method for identification of mixed yeast isolates

Based on the results obtained in this study, all mixed samples including samples with 2 or 3 species in the same test tube as well as mixed cases from different test tubes were correctly identified, and the YEAST PLEX assay was shown to be highly reliable in these cases (Table 2).

4. DISCUSSION

The genus Candida with over 30 distinct human pathogenic species is the most common cause of invasive yeast infections. 34 Some non‐Candida yeasts are also important pathogens, since they can cause life‐threatening diseases. 35 From both epidemiological and clinical viewpoints, proper methods are required for accurate identification of these pathogens. In this study, we described YEAST PLEX as an accurate, simple, and low‐cost (less than one US dollar per sample) method for identification of various yeast pathogens.

The selection of molecular target(s) is the cornerstone of developing DNA‐based identification methods. In the present study, except for three species (C. tropicalis, C. norvegensis and R. mucilaginosa), the ITS region was used as the molecular target. This region had been proposed as the universal DNA barcode marker for identification of fungi because of the simplicity of its amplification due to the high copy numbers and its high resolution in species differentiation. 31 Accordingly, our method could be considered superior to a similar method 25 that is mainly based on targets other than ITS. Moreover, because the sensitivity of PCR is negatively associated with the length of the amplicon size, an amplicon‐size limit of 500 bp was applied when designing the primers. Compared with the recently described multiplex assay, which used amplicon sizes of about 700–800 bp, with some even being longer than 1100 bp, 25 our YEAST PLEX primers could result in a higher sensitivity, making it a better approach for both detection and identification of yeasts directly from clinical specimens.

The hands‐on time and the extent of species/genera coverage along with the cost and reagent/instrument requirements are important factors when evaluating a method, especially in resource‐limited settings. Almost all of currently available methods are limited in one or more ways. For instance, PCR‐RFLP, specific PCR, or nested PCR 13 , 17 , 18 can only identify a limited number of species, and real‐time PCR‐based methods 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 require expensive reagents/instruments. Regarding the non‐molecular methods, such as the MALDI‐TOF MS, the high cost is the main limitation for resource‐limited settings. 36 Recently, a three‐step multiplex PCR method was described that is able to identify 21 of the most clinically important yeasts. 25 Although this method has the lowest reagent/instrument requirements, it still has some limitations that we covered in the YEAST PLEX. Regarding the coverage, although the YEAST PLEX directly identifies 17 species/genera, tube D, which uses universal ITS1 and ITS4 primers for pathogens that are not covered by this method, provides amplicons for sequencing. Accordingly, it could be claimed that all yeasts are identifiable by YEAST PLEX, either directly by its results or by sequence analysis of the amplicon of tube D. Rapid identification is another important factor, especially when there is a need for timely initiation of treatment. With this factor in mind, YEAST PLEX was designed to involve two steps. The first step (tube A) quickly identifies the most common and important Candida species. In the case of a negative result, the isolate in question will be subjected to tubes B, C, and D, simultaneously (step 2). In this way, the hands‐on time will be reduced because there is no need to wait for the results of tube B, before moving on to tube C and then finally to tube D. Indeed, YEAST PLEX requires only about 3–6 h (depending on the need to include one or two run(s) of PCR) to identify a yeast isolate or provide a PCR amplicon of uncovered species for sequencing. Moreover, this method has a low reagent requirement and can be performed using conventional PCR machines. Accordingly, YEAST PLEX appears to be a good choice for identification of yeasts in low‐income and in large‐scale studies where it is important to decrease the costs.

Regarding test accuracy, YEAST PLEX was evaluated as a reliable assay in identification of yeasts. The results obtained by this method were in agreement with those of sequencing/MALDI‐TOF MS. Of note, YEAST PLEX was found to be a promising method in detecting mixed isolates, as it was able to identify five isolates that reflected mixes of two species and that were thought to be pure isolates based on sequencing/MALDI‐TOF MS data. This could be a result of an unequal mixing pattern, where the less abundant strain remained undetected by sequencing/MALDI‐TOF MS, while by YEAST PLEX, and due to the small amplicon sizes, the less abundant strain had a higher chance of being detected. Moreover, YEAST PLEX correctly identified 18 mixed suspensions of two or three species from the same or different genera. This feature could be very important, as in a recent multicenter study on mixed yeast spp. infections, it was reported that from a total of 6895 culture‐positive otherwise sterile specimens, 150 (2.2%) represented a mix of two species, either from the same or from different genera. Geographical variation was observed in the prevalence of mixed cases, and the prevalence ranged from 0% for Thailand, the USA, Serbia, and Austria to 6.4% for Poland. 37 Mixed rates of 4.03% and 8.78% due to two, three, and even four distinct species have also been reported in other studies. 37 , 38 , 39 Accordingly, management of such infections could be challenging. Moreover, because having a pure colony is a prerequisite for performing antifungal susceptibility testing, mixed pattern could interfere with this method and lead to invalid results. YEAST PLEX could be a low‐cost method for detecting such mixed cases, thereby assisting in the management of patients and reporting accurate susceptibility patterns to antifungal drugs, a feature that would warrant further studies in this regard.

A concern with the method described in this study might relate to the low amplicon‐size difference (e.g., <50 bp) in some cases. However, using the in‐house prepared size marker, the interpretation of results is much easier than when using the usual size markers. As a limitation, some rare yeasts, such as Geotrichum species, are not covered by YEAST PLEX. Moreover, regarding the identification of mixed isolates, our results are based on a limited number of mixed suspensions. Regarding the 89 unknown clinical isolates, due to financial and technical limits, we were not able to confirm the results of YEAST PLEX assay by sequencing all the isolates, and only randomly selected isolates were checked, which is another limitation of the study.

We have tested a multiplex PCR for detection of pathogenic yeast directly from some clinical samples, and we have plan to expand the variations and increase the number of the samples before reporting the results.

5. CONCLUSION

According to the results of the present study, the YEAST PLEX assay could be relied on as a simple, low‐cost, and rapid method for accurate identification of a wide range of clinically important yeast species with a minimum of reagent and instrumental requirements relative to other methods. Moreover, this method was found to be promising for detecting and differentiating mixed yeast isolates.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1

Table S2

Aboutalebian S, Mahmoudi S, Charsizadeh A, Nikmanesh B, Hosseini M, Mirhendi H. Multiplex size marker (YEAST PLEX) for rapid and accurate identification of pathogenic yeasts. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36:e24370. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24370

Funding information

This study was financially supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran (Grant No. 196066)

REFERENCES

- 1. Aydin M, Kustimur S, Kalkanci A, Duran T. Identification of medically important yeasts by sequence analysis of the internal transcribed spacer and D1/D2 region of the large ribosomal subunit. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2019;36(3):129‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cortegiani A, Misseri G, Chowdhary A. What’s new on emerging resistant Candida species. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(4):512‐515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colombo AL, Júnior JN, Guinea J. Emerging multidrug‐resistant Candida species. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017;30(6):528‐538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Posteraro B, Spanu T, Fiori B, et al. Antifungal susceptibility profiles of bloodstream yeast isolates by sensititre yeastone over nine years at a large Italian teaching hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(7):3944‐3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tortorano A, Peman J, Bernhardt H, et al. Epidemiology of candidaemia in Europe: results of 28‐month European confederation of medical mycology (ECMM) hospital‐based surveillance study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;23(4):317‐322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mirhendi H, Charsizadeh A, Aboutalebian S, et al. South Asian (Clade I) Candida auris meningitis in a paediatric patient in Iran with a review of the literature. Mycoses, 2022;65(2):134‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mahmoudi S, Rezaie S, Ghazvini RD, et al. In vitro interaction of geldanamycin with triazoles and echinocandins against common and emerging Candida species. Mycopathologia. 2019;184(5):607‐613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meis JF, Chowdhary A. Candida auris: a global fungal public health threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(12):1298‐1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chitasombat MN, Kofteridis DP, Jiang Y, Tarrand J, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Rare opportunistic (non‐Candida, non‐Cryptococcus) yeast bloodstream infections in patients with cancer. J Infect. 2012;64(1):68‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lin SY, Lu PL, Tan BH, et al. The epidemiology of non‐Candida yeast isolated from blood: the Asia surveillance study. Mycoses. 2019;62(2):112‐120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pfaller MA, Castanheira M. Nosocomial candidiasis: antifungal stewardship and the importance of rapid diagnosis. Med Mycol. 2016;54(1):1‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leaw SN, Chang HC, Sun HF, Barton R, Bouchara J‐P, Chang TC. Identification of medically important yeast species by sequence analysis of the internal transcribed spacer regions. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(3):693‐699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taira CL, Okay TS, Delgado AF, Ceccon MEJR, de Almeida MTG, Del Negro GMB. A multiplex nested PCR for the detection and identification of Candida species in blood samples of critically ill paediatric patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pincus D, Orenga S, Chatellier S. Yeast identification—past, present, and future methods. Med Mycol. 2007;45(2):97‐121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Linton CJ, Borman AM, Cheung G, et al. Molecular identification of unusual pathogenic yeast isolates by large ribosomal subunit gene sequencing: 2 years of experience at the United Kingdom mycology reference laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(4):1152‐1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khodadadi H, Karimi L, Jalalizand N, Adin H, Mirhendi H. Utilization of size polymorphism in ITS1 and ITS2 regions for identification of pathogenic yeast species. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66(2):126‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trost A, Graf B, Eucker J, et al. Identification of clinically relevant yeasts by PCR/RFLP. J Microbiol Methods. 2004;56(2):201‐211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mirhendi H, Makimura K, Khoramizadeh M, Yamaguchi H. A one‐enzyme PCR‐RFLP assay for identification of six medically important Candida species. Nippon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 2006;47(3):225‐229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Foongladda S, Mongkol N, Petlum P, Chayakulkeeree M. Multi‐probe real‐time PCR identification of four common Candida species in blood culture broth. Mycopathologia. 2014;177(5–6):251‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maaroufi Y, Heymans C, De Bruyne J‐M, et al. Rapid detection of Candida albicans in clinical blood samples by using a TaqMan‐based PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(7):3293‐3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nemcova E, Cernochova M, Ruzicka F, Malisova B, Freiberger T, Nemec P. Rapid identification of medically important Candida isolates using high resolution melting analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Decat E, Van Mechelen E, Saerens B, et al. Rapid and accurate identification of isolates of Candida species by melting peak and melting curve analysis of the internally transcribed spacer region 2 fragment (ITS2‐MCA). Res Microbiol. 2013;164(2):110‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Innings Å, Ullberg M, Johansson A, et al. Multiplex real‐time PCR targeting the RNase P RNA gene for detection and identification of Candida species in blood. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(3):874‐880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fujita S‐I, Senda Y, Nakaguchi S, Hashimoto T. Multiplex PCR using internal transcribed spacer 1 and 2 regions for rapid detection and identification of yeast strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(10):3617‐3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arastehfar A, Fang W, Pan W, et al. YEAST PANEL multiplex PCR for identification of clinically important yeast species: stepwise diagnostic strategy, useful for developing countries. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;93(2):112‐119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang A, Li J‐W, Shen Z‐Q, Wang X‐W, Jin M. High‐throughput identification of clinical pathogenic fungi by hybridization to an oligonucleotide microarray. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(9):3299‐3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahmed A, Azim A, Baronia A, Marak RS, Gurjar M. Invasive candidiasis in non neutropenic critically ill‐need for region‐specific management guidelines. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2015;19(6):333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aslani N, Janbabaei G, Abastabar M, et al. Identification of uncommon oral yeasts from cancer patients by MALDI‐TOF mass spectrometry. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mirhendi H, Charsizadeh A, Eshaghi H, Nikmanesh B, Arendrup MC. Species distribution and antifungal susceptibility profile of Candida isolates from blood and other normally sterile foci from pediatric ICU patients in Tehran, Iran. Med Mycol. 2020;58(2):201‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aboutalebian S, Mahmoudi S, Okhovat A, Khodavaisy S, Mirhendi H. Otomycosis due to the rare fungi talaromyces purpurogenus, Naganishia albida and Filobasidium magnum. Mycopathologia. 2020;185(3):569‐575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schoch CL, Seifert KA, Huhndorf S, et al. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(16):6241‐6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aboutalebian S, Ahmadikia K, Fakhim H, et al. Direct detection and identification of the most common bacteria and fungi causing otitis externa by a stepwise multiplex PCR. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lott TJ, Kuykendall RJ, Reiss E. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the 5.8S rDNA and adjacent ITS2 region of Candida albicans and related species. Yeast. 1993;9(11):1199‐1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gabaldón T. Recent trends in molecular diagnostics of yeast infections: from PCR to NGS. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2019;43(5):517‐547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Friedman DZP, Schwartz IS. Emerging fungal infections: new patients, new patterns, and new pathogens. J Fungi. 2019;5(3):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robert M‐G, Cornet M, Hennebique A, et al. MALDI‐TOF MS in a medical mycology laboratory: on stage and backstage. Microorganisms. 2021;9(6):1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Medina N, Soto‐Debrán JC, Seidel D, et al. MixInYeast: a multicenter study on mixed yeast infections. J Fungi. 2020;7(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cassagne C, Normand AC, Bonzon L, et al. Routine identification and mixed species detection in 6,192 clinical yeast isolates. Med Mycol. 2016;54(3):256‐265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yang YL, Chu WL, Lin CC, Zhou ZL, Chen PN, Lo HJ. Mixed yeast infections in Taiwan. Med Mycol. 2018;56(6):770‐773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Table S2