Abstract

PURPOSE:

The objective of this study is to examine the association between an academic medical center and free clinic referral partnership and subsequent hospital utilization and costs for uninsured patients discharged from the academic medical center’s emergency department (ED) or inpatient hospital.

METHODS:

This retrospective, cross-sectional study included 6014 uninsured patients age 18 and older who were discharged from the academic medical center’s ED or inpatient hospital between July 2016 and June 2017 and were followed for 90 days in the organization’s electronic medical record to identify the occurrence and cost of subsequent same-hospital ED visits and hospital admissions. The occurrence of any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions and the cost of subsequent hospital care were compared by free clinic referral status after inverse probability of treatment weighting.

RESULTS:

Overall, 330 (5.5%) of uninsured patients were referred to the free clinic. Compared with patients referred to the free clinic, patients not referred had greater odds of any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions within 90 days (odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval: 1.7–2.0). For patients with any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions, the mean cost of care for those who were not referred to the free clinic was 2.3 times higher (95% confidence interval: 2.0–2.7) compared to referred patients.

CONCLUSION:

An academic medical center-free clinic partnership for follow-up care after discharge from the ED or hospital admission is a promising approach for improving access to care for uninsured patients.

Keywords: Academic medical center, Academic medical center-free clinic partnership, Emergency department visits, Free clinic, Hospital costs, Hospitalizations, Uninsured patients

INTRODUCTION

Not-for-profit hospitals play an essential role in providing health care for the poor and uninsured in the United States. Despite more people becoming insured after Medicaid expansion through the Affordable Care Act, 28.9 million people younger than the age of 65 remained without insurance, and 3 in 10 of uninsured adults went without medically necessary care in 2019.1 Uninsured patients often lack access to primary care and use an emergency department (ED) or are hospitalized due to delaying medical care for an acute or chronic condition.2,3 Additionally, the risks of in-hospital and overall mortality are significantly higher for the uninsured.4–6 At the same time, hospitals need to address continued pressure to contain costs in an environment where uncompensated care represents 5.7% of hospital expenditures.7 One way for hospitals to address the ongoing health care needs for uninsured patients may be through forming partnerships with community clinics to refer patients for primary care.

Previous studies have examined the relationship between access to primary care and subsequent ED and hospital admissions for uninsured patients,8,9 and in particular, geo-graphic areas with a community clinic have better population outcomes.10,11 Although community clinics, such as federally qualified health centers, public clinics, and free clinics, play a critical role in providing medical care for uninsured patients,12–15 referrals from a hospital to a community clinic are often informal, requiring patients to directly schedule an appointment themselves. One way to strengthen the referral process between a hospital and community clinic is to establish a formal referral partnership, where the hospital compensates at a contracted rate, the community clinic’s costs for providing timely follow-up care to the uninsured patients referred to the clinic.

Our objective was to examine the association between an academic medical center—free clinic referral partnership and subsequent ED visits and hospital admissions and, for those with any subsequent hospital care, costs for 90 days after the index encounter for uninsured patients age 18 or older. We hypothesized that referral from the academic medical center to the free clinic would be associated with reduced likelihood of subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions and lower costs for 90 days after discharge from the first hospital encounter, compared with uninsured patients who were not referred to the free clinic.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a retrospective, cross-sectional study of uninsured patients age 18 and older who were discharged from the academic medical center’s ED or inpatient hospital between July 1, 2016, and June 30, 2017. We searched for these patient records in the organization’s electronic medical record (EMR) system to identify the occurrence of all subsequent ED visits and hospital admissions for 90 days following the index hospital encounter date. The sample included all patients discharged from the ED or inpatient hospital who were classified as uninsured based on primary payer. For patients referred to the free clinic, the first ED visit or inpatient hospital discharge with a free clinic referral was classified as the index encounter. For patients not referred to the free clinic, the first ED visit or inpatient hospital discharge during the study period was classified as the index encounter. Patient records with missing demographic information were excluded from the study. Data were obtained from the enterprise-wide electronic medical record system, cost accounting system, and the academic medical center’s population health patient care navigator database.

CommunityHealth is the largest volunteer-based free clinic in the United States and located on the West Side of Chicago. Rush University Medical Center (RUMC), a 676-bed academic medical center also located on the West Side of Chicago, sends attending physicians and residents to the free clinic as volunteers to provide clinical services. The academic medical center and free clinic formed an expanded partnership in June 2016 where the free clinic agreed to provide primary and follow-up care for uninsured patients referred from academic medical center’s ED or inpatient units. As part of this relationship, the free clinic contacts patients to schedule a follow-up appointment after discharge and provides follow-up appointments within 14 days of referral. Patient navigators are assigned to identify uninsured patients without a primary care provider in the academic medical center’s ED and on inpatient internal medicine floors. These patients are referred to the free clinic at ED or inpatient hospital discharge. Due to patient navigator staffing limitations, only a small proportion of the uninsured patients without a primary care provider were identified and referred to the free clinic during the study period. Patients who were uninsured and not referred to the free clinic received standard instructions for postdischarge follow-up care that may have included a 1-time visit in the academic medical center’s transition clinic or referral to other community resources. The academic medical center makes an annual lump-sum payment to the free clinic to support the care management infrastructure and to manage referrals from the organization, which may reach to 400, annually.

Measurement of Variables

The primary outcomes included any subsequent same-hospital ED visits or hospital admissions within 90 days after the index encounter discharge date (yes/no) and the total cost of these encounters. Utilization and costs were collected for 90 days after the index encounter discharge date because the referral partnership’s aim was to address both the immediate postdischarge and primary care needs of referred patients. Total cost was measured as the sum of all direct (eg, nursing care, laboratory tests, pharmacy, surgical costs) and indirect costs to the hospital (rather than payments or charges) to provide care in 2017 US dollars. We used a bottom-up approach that summed all hospital costs associated with the subsequent ED visits and hospital admissions to calculate total cost. Additional binary variables were created to indicate any subsequent ED visits (yes/no) and any subsequent inpatient hospital admissions (yes/no) separately. The total cost of subsequent ED visits and total cost of subsequent inpatient hospital admissions were also calculated.

The main independent variable was referral to the free clinic, regardless of whether the appointment was completed (yes/no). Other independent variables included patient demographic characteristics and clinical factors. Patient demographic characteristics included age (18–45, 46–64, 65 and older), sex (male, female), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic other). Clinical factors included type of index encounter (ED visit, inpatient hospital admission); primary reason for care based on the principal International Classification of Diseases-10th edition (ICD-10) diagnosis code, using the Clinical Classification Software Refined;16 number of chronic conditions based on the secondary International Classification of Diseases-10th edition diagnosis codes included in the hospital discharge record, determined using the Elixhauser Comorbidity Software Refined;17,18 and binary indicators for the presence or absence of each of the 5 most common chronic conditions in the study population (hypertension, diabetes, obesity, electrolyte disorders, and alcohol and drug abuse). The total number of chronic conditions (median = 0; range 0–10) was also classified into the presence of 2 or more versus 0–1 chronic conditions.

Statistical Analysis

χ2 tests were used to test the association between free-clinic referral status and all nominal and ordinal variables, and a Mann Whitney U test was used to test the association between the free-clinic referral and total cost. P values are reported based on 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

To account for potential imbalances in observed patient characteristics by free-clinic referral status, we constructed a propensity score for the free-clinic referral using a logistic regression model that included patient demographic characteristics, clinical factors, and index encounter type as predictors. The predicted probability of referral was calculated from the model, and the inverse probability of treatment weight was computed, such that each patient referred to the free clinic had a weight of (1/propensity score) and each patient not referred had a weight of [1/(1−propensity score)]. Data were trimmed at both the lower and upper ends for observations with nonoverlapping propensity scores (n = 6).19 We compared the mean propensity score by quintile bin to ensure that the distribution of the inverse probability of treatment weight was balanced. The standardized mean difference for each covariate was assessed for the weighted and unweighted sample.20,21The distribution of each covariate was considered to be balanced if the standardized mean difference of the inverse probability of treatment weight was less than 20%.22,23

Two-part weighted regression models were estimated to test the associations between the free-clinic referral with any subsequent hospital care and total cost, controlling for patient demographic characteristics and clinical factors. The first model was a weighted logistic regression model to estimate the association between free-clinic referral and any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions. The second model was a weighted generalized linear regression model with a gamma distribution and log link function that estimated the association between free-clinic referral and total costs, conditional on having at least 1 subsequent ED visit or hospital admission. Similar sets of models that were stratified by index encounter type were constructed. The area under the receiver operating characteristics curve and Hosmer Lemeshow test statistic were assessed for model goodness-of-fit of each logistic regression model. To predict the number of patients who would have subsequently returned to the ED or inpatient hospital, had they not been referred to the free clinic, coefficients from the fitted logistic regression model were applied to the data set for the counterfactual scenario where patients referred to the free clinic were not referred. Microsoft Excel and SAS version 9.4 were used for data management and analysis.

RESULTS

The sample included 330 (5.5%) patients referred to the free clinic and 5684 (94.5%) patients not referred. Compared with patients not referred to the free clinic, referred patients were older (median age 35 vs 33 years, P = .003), more likely to be male (61.2% vs 50.4%, P < .001), to be Hispanic (37.6% vs 25.3%, P < .001), and to have an inpatient index encounter type (22.1% vs 9.6%, P < .001) (Table 1). Compared with their not referred counterparts, patients referred to the free clinic were less likely to have any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions (13.6% vs 19.9%, P = .005) within 90 days after index encounter discharge (Table 1). Median total cost for patients with any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions was not significantly different (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the Sample (N = 6014)

| Referred Patients N = 330 |

Not Referred Patients N = 5684 |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | |||

| Age, median (IQR) | 35 (27, 50) | 33 (25, 46) | .003 |

| Age categories, n (%) | .013 | ||

| 18–45 | 224 (67.9) | 4240 (74.6) | |

| 46–64 | 93 (28.2) | 1211 (21.3) | |

| 65 and older | 13 (3.9) | 233 (4.1) | |

| Sex, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Male | 202 (61.2) | 2865 (50.4) | |

| Female | 128 (38.8) | 2819 (49.6) | |

| Patient race/ethnicity, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 46 (13.9) | 985 (17.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 140 (42.4) | 2828 (49.8) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 124 (37.6) | 1440 (25.3) | |

| Other | 20 (6.1) | 431 (7.6) | |

| Principal diagnosis, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 45 (13.6) | 512 (9.0) | |

| Diseases of the digestive condition | 37 (11.2) | 372 (6.5) | |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 33 (10.0) | 490 (8.6) | |

| Injury, poisoning, and other consequences of external causes | 27 (8.2) | 777 (13.7) | |

| Mental, behavioral, or neurodevelopmental disorder | 9 (2.7) | 445 (7.8) | |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 32 (9.7) | 557 (9.8) | |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 17 (5.2) | 348 (6.1) | |

| Symptoms, signs, and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings | 47 (14.2) | 882 (15.5) | |

| Other principal diagnoses | 83 (25.2) | 1301 (22.9) | |

| Chronic conditions, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 75 (22.7) | 994 (17.5) | .016 |

| Diabetes | 29 (8.8) | 422 (7.4) | .361 |

| Obesity | 46 (13.9) | 315 (5.5) | <.001 |

| Electrolyte disorders | 36 (10.9) | 197 (3.5) | <.001 |

| Alcohol or drug abuse | 51 (15.5) | 559 (9.8) | .001 |

| Two or more chronic conditions, n (%) | 91 (27.6) | 895 (15.8) | <.001 |

| Index encounter type, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Emergency department | 257 (77.9) | 5136 (90.4) | |

| Inpatient hospital | 73 (22.1) | 548 (9.6) | |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions within 90 days of index encounter discharge date, n (%) | 45 (13.6) | 1132 (19.9) | .005 |

| Any subsequent ED visits, n (%) | 39 (11.8) | 1004 (17.7) | .006 |

| Any subsequent hospital admissions, n (%) | 9 (2.7) | 194 (3.4) | .502 |

| 90-day total cost of subsequent ED visits and hospital admissions, users only, median (IQR) in $ | 1059 (463, 4067) | 746 (413, 2474) | .175 |

ED = emergency department; IQR = interquartile range.

Costs reported in 2017 dollars. All statistics reported in this table are unweighted.

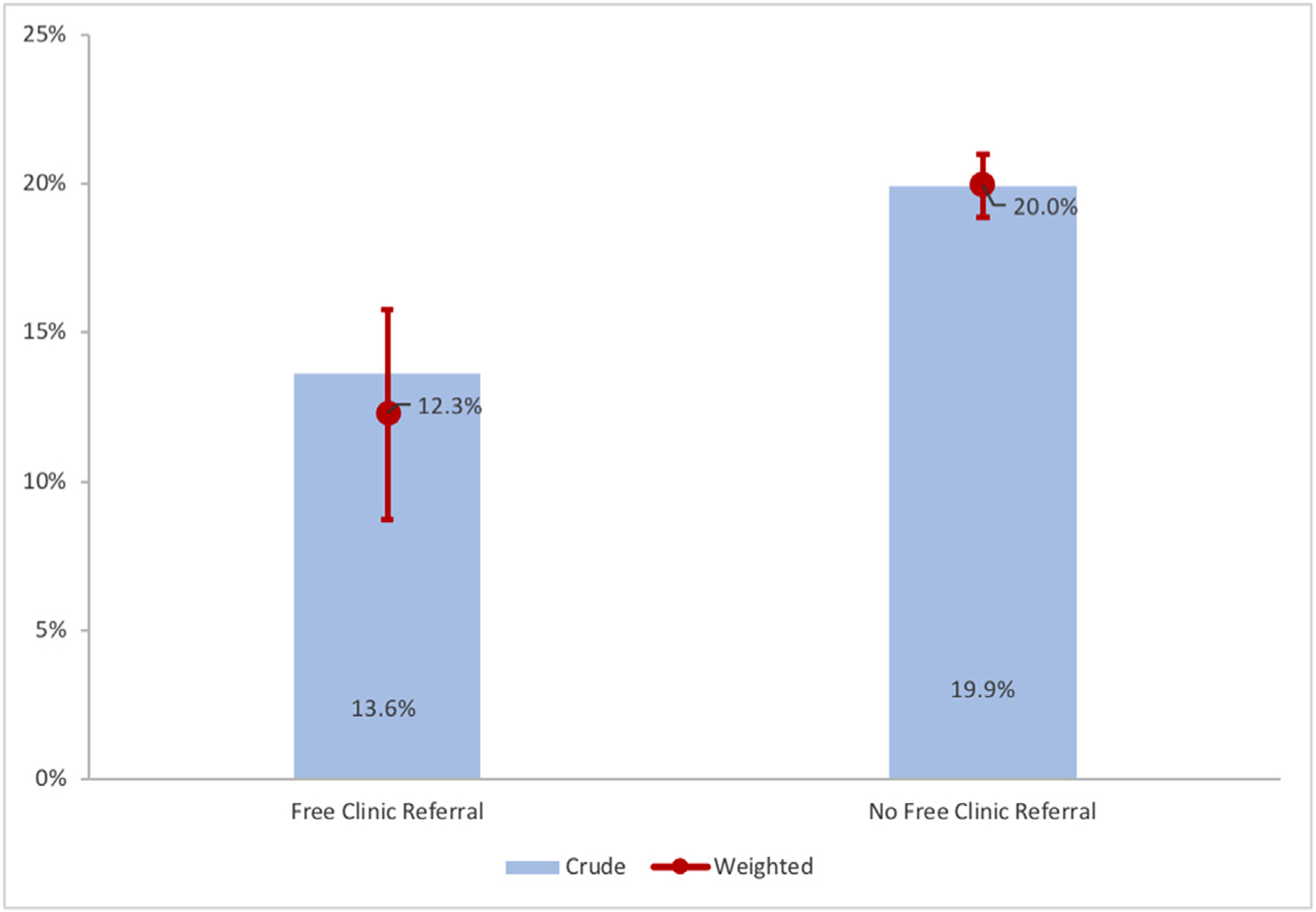

Supplementary Table 1, available online, reports the variables included in the propensity score model for the free-clinic referral, with unweighted and weighted distributions. Weighting decreased the standardized mean difference by referral status for all covariates (Supplementary Figure, available online), and all standardized mean differences after weighting were less than 5%, demonstrating balance between groups. Furthermore, propensity scores within quintile bin were also balanced between referral groups (Supplementary Table 2, available online). The mean weighted proportion of patients with any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions was 12.3% for referred patients and 20.0% for patients not referred to the free clinic, respectively (Figure).

Figure.

Crude and weighted proportion of patients with any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions within 90 days after index encounter discharge. Red line represents 95% CI of the weighted proportion with any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions. CI = confidence interval; ED = emergency department.

Table 2 reports the results of the weighted logistic regression model for any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions. Patients not referred to the free clinic were significantly more likely to have a subsequent ED visit or hospital admission (odds ratio [OR] = 1.84, 95% CI, 1.66–2.03) (Table Supplementary 3, available online). Conditional on having any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions, patients not referred to the free clinic had 2.34 times higher total costs (95% CI, 2.01–2.72) than their referred counterparts (Table 3; Supplementary Table 4, available online).

Table 2.

Multivariable Logistic IPTW Analysis, Any Subsequent ED Visits or Hospital Admissions (N = 6008)

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Not referred to free clinic | 1.84 (1.66–2.03) | <.001 |

CI = confidence interval; ED = emergency department; IPTW = inverse probability treatment weighting; OR = odds ratio; ROC = receiver operating characteristic.

Area under the ROC curve = 0.58; Model adjusts for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, principal diagnosis, presence of chronic conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, electrolyte disorders, alcohol or drug abuse; having 2 or more chronic conditions, and index visit type of hospitalization; model is weighted with inverse probability of treatment weight.

Table 3.

Generalized Linear IPTW Analysis, 90-Day Total Costs for Patients with Any Subsequent ED Visits or Hospital Admissions (N = 1174)

| Variable | Cost Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Not referred to free clinic | 2.34 (2.01–2.72) | <.001 |

CI = confidence interval; ED = emergency department; IPTW = inverse probability treatment weighting.

Model adjusts for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, principal diagnosis, presence of chronic conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, electrolyte disorders, alcohol or drug abuse; having 2 or more chronic conditions, and index visit type of hospitalization; model is weighted with inverse probability of treatment weight.

Additionally, patients not referred to the free clinic had significantly higher odds of having at least 1 subsequent hospital admission, compared with their referred counterparts (OR = 2.38, 95% CI, 1.86–3.05) (Supplementary Table 5, available online). In weighted logistic regression models stratified by index encounter type, patients with an index ED visit who were not referred to the free clinic were 1.67 times more likely (95% CI, 1.50–1.87) to have any subsequent ED visits or hospital and patients with a hospital admission as the index encounter type who were not referred to the free clinic were 3.02 times more likely (95% CI, 2.22–4.10) to have any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions as patients who were referred (Supplementary Table 6, available online).

We then calculated the predicted probability of any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions for patients referred to the free clinic, assuming they had not been referred, using the coefficients from the weighted logistic regression model. The probability of any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions would have been 21.8% rather than 13.6%, translating into 28 more patients who would have had at least 1 subsequent ED visit or hospital admission of the 330 patients referred to the free clinic.

DISCUSSION

Uninsured patients referred to the free clinic, regardless of whether they kept the appointment, were less likely to return to the ED or be readmitted within 90 days of their index hospital encounter, despite being older and having greater clinical complexity. Our results support prior findings that referral for follow-up care reduces subsequent ED visits and hospitalizations for uninsured patients.3,24 Block et al24 evaluated the effectiveness of The Access Partnership, an academic medical center-primary care center partnership to provide care for uninsured patients in Baltimore. They found that patients referred for follow-up care had 2 fewer ED visits leading to admission per 100 patient-months compared with patients who declined participation in the program. In a study of Project Access Dallas that provided community care coordination services, a primary care physician and access to a network of physicians, hospitals, and ancillary services to uninsured patients, DeHaven et al3 found that patients who were enrolled in the intervention had 35% fewer ED visits, 65% fewer hospital days, and 60% lower direct costs in the 12 months following program referral compared with uninsured patients who were not referred. Their intervention differed from our referral partnership by requiring patients to have at least 2 ED visits in the prior year and having a larger network of physicians, community clinics, and pharmacies; however, our results were similar.

The academic medical center-free clinic partnership extended beyond simply referring patients in several important ways that warrant discussion. The free clinic proactively reached out to patients referred to the clinic for appointment scheduling, which is likely to have increased the proportion of patients who completed their first appointment in the free clinic. Second, the academic medical center patient care navigators who were responsible for referring patients to the free clinic had established relationships with the front desk staff at the free clinic, facilitating patient referrals at the time of ED or hospital discharge. The free clinic provided both immediate postdischarge care and primary care, thereby serving as a medical home for patients. The 90-day follow-up time frame in our study allowed us to capture the impact of the referral partnership on not only the immediate postdischarge care needs but also broader health and social care needs that may increase the risk for subsequent care in the ED or hospital if left unaddressed. Finally, the partnership may have been further strengthened due to the fact that the academic medical center’s attending physicians and residents volunteer to provide medical care at the free clinic. These unique aspects of the partnership are likely to be associated with a reduction in subsequent ED visits and hospital admissions.

Our results inform other hospitals and community clinics of 1 possible way to better meet the needs of uninsured patients discharged from the ED or inpatient hospital who do not have a primary care provider. Although our results are promising, other approaches for providing care to uninsured patients discharged from the hospital have been implemented, such as transitional care clinics, and future research should compare the outcomes of a hospital-community health center partnership with other methods of providing follow-up and ongoing primary care.

Limitations

Although this study was unique by examining outcomes associated with an academic medical center—free clinic referral partnership for uninsured patients, there are limitations. First, this was an observational study and not a randomized trial, and while we used advanced statistical methods to account for potential selection bias between patients referred and not referred to the free clinic, our results should be interpreted with caution. Randomized trials of care management for high users more broadly have shown low or no cost savings.25 Additionally, subsequent hospital care was limited to same-hospital ED visits and hospital admissions. We could not capture care that occurred outside of the academic medical center, and therefore, our results represent a lower bound of subsequent ED visits and hospital admissions. Fewer than 6% of uninsured patients were referred to the free clinic during the study period. While we used inverse probability of treatment weighting to adjust for differences in observed characteristics between patients who were referred to the free clinic compared with those who were not referred, the possibility of selection bias remains. Furthermore, of those patients who were referred to the free clinic, a small number had any subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions (n = 45), which limits the generalizability of our analysis of subsequent costs. However, given that a relatively small proportion of patients incurred subsequent hospital costs, prospectively identifying patients who are at risk for subsequent hospital care is critical for prioritizing resources. We did not have detailed data about the proximity of follow-up care to each patient’s home residence for the patients not referred to the free clinic and could not account for geo-graphic proximity to either follow-up care or the academic medical center in our analyses. Future work should examine the proximity of home address to other health care providers. Although follow-up appointment completion has been shown to be a significant predictor of hospital read-mission for patients without an established primary care provider,26 we did not have information about whether a referred patient completed a follow-up visit at the free clinic. Finally, we were not able to disentangle the extent to which the reduction in subsequent ED visits or hospital admissions was due to having an initial postdischarge follow-up appointment compared with the establishment of an ongoing medical home.

CONCLUSION

As policies for meeting the health care needs for uninsured patients continue to evolve, hospitals must ensure as part of their mission that there are avenues in place to direct patients to follow-up care. In addition to other financial approaches that could be used to redistribute funding from hospitals to free clinics, our results provide evidence to support hospital-community health center partnerships as a potential strategy to improve access for uninsured patients.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE.

Uninsured patients who were referred to the free clinic for care after discharge from the academic medical center’s emergency department or inpatient hospital were significantly less likely to have subsequent emergency department visits or hospital admissions within 90 days after discharge.

The cost of subsequent emergency department visits and hospital admissions within 90 days after the initial encounter discharge date was significantly higher for patients who were not referred to the free clinic compared with referred patients.

A formal academic medical center—free clinic partnership is a potential strategy for reducing subsequent emergency department visits and hospital admissions for uninsured patients.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.06.011.

References

- 1..Tolbert J, Orgera K, Damico A. Key Facts About the Uninsured Population. Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at: https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/. Accessed May 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufman A, Derksen D, McKernan S, et al. Managed care for uninsured patients at an academic health center: a case study. Acad Med 2000;75(4):323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeHaven M, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Gimpel N, et al. The effects of a community-based partnership, Project Access Dallas (PAD), on emergency department utilization and costs among the uninsured. J Public Health 2012;34(4):577–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdullah F, Zhang Y, Lardaro T, et al. Analysis of 23 million US hospitalizations: Uninsured children have higher all-cause in-hospital mortality. J Public Health 2010;32(2):236–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hadley J, Steinberg EP, Feder J. Comparison of uninsured and privately insured hospital patients. condition on admission, resource use, and outcome. JAMA 1991;265(3):374–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. The relationship of health insurance and mortality: Is lack of insurance deadly? Ann Intern Med 2017;167 (6):424–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garthwaite C, Gross T, Notowidigdo M, Garthwaite C, Gross T, Notowidigdo M. Who Bears the Cost of the Uninsured? Nonprofit Hospitals. Available at: https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/who-bears-the-cost-of-the-uninsured-nonprofit-hospitals. Accessed November 7, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grumbach K, Keane D, Bindman A. Primary care and public emergency department overcrowding. Am J Public Health 1993;83 (3):372–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai MH, Xirasagar S, Carroll S, et al. Reducing high-users’ visits to the emergency department by a primary care intervention for the uninsured: A retrospective study. Inquiry 2018;55:46958018763917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rust G, Baltrus P, Ye J, et al. Presence of a community health center and uninsured emergency department visit rates in rural counties. J Rural Health 2009;25(1):8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham P, Sheng Y. Trends in preventable inpatient and emergency department utilization in California between 2012 and 2015: The role of health insurance coverage and primary care supply. Med Care 2018;56(6):544–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darnell JS. Free clinics in the United States: a nationwide survey. Arch Intern Med 2010;170(11):946–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gertz AM, Frank S, Blixen CE. A survey of patients and providers at free clinics across the United States. J Community Health 2011;36(1):83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchison J, Thompson ME, Troyer J, Elnitsky C, Coffman MJ, Lori Thomas M. The effect of North Carolina free clinics on hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions among the uninsured. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sack DE, Chakravarthy R, Gerhart CR, et al. Emergency department use among student-run free clinic patients: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med 2021;36(3):830–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Clinical Classification Software Refined (CCSR). Available at: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccsr/ccs_refined.jsp. Accessed March 2021.

- 17.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Elixhauser Comorbidity Software Refined for ICD-10-CM. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tools-software/comorbidityicd10/comorbidity_icd10_archive.jsp. Accessed May 25, 2021.

- 18.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36(1):8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stürmer T, Rothman KJ, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Treatment effects in the presence of unmeasured confounding: dealing with observations in the tails of the propensity score distribution−a simulation study. Am J Epidemiol 2010;172(7):843–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thoemmes FJ, West SG. The use of propensity scores for nonrandomized designs with clustered data. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46 (3):514–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015;34(28):3661–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuart EA, Lee BK, Leacy FP. Prognostic score-based balance measures can be a useful diagnostic for propensity score methods in comparative effectiveness research. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66(8 Suppl): S84–S90.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 2009;28(25):3083–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Block L, Ma S, Emerson M, Langley A, Torre Ddl, Noronha G. Does access to comprehensive outpatient care alter patterns of emergency department utilization among uninsured patients in East Baltimore? J Prim Care Community Health 2013;4 (2):143–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams BC. Limited effects of care management for high utilizers on total healthcare costs. Am J Manag Care 2015;21(4):e244–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chakravarthy V, Ryan MJ, Jaffer A, et al. Efficacy of a transition clinic on hospital readmissions. Am J Med 2018;131 (2):178–184.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.