Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Extracorporcal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is increasingly utilized as a bridge to lung transplantation, but ECMO status is not explicitly accounted for in the Lung Allocation Score (LAS). We hypothesized that among waitlist patients on ECMO, patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) would have lower transplantation rates.

METHODS:

Using United Network for Organ Sharing data, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients who were ≥12 years old, active on the lung transplant waitlist, and required ECMO support from June 1, 2015 through June 12, 2020. Multivariable competing risk analysis was used to examine waitlist outcomes.

RESULTS:

1064 waitlist subjects required ECMO support; 40 (3.8%) had obstructive lung disease (OLD), 97 (9.1%) had PAH, 138 (13.0%) had cystic fibrosis (CF), and 789 (74.1%) had interstitial lung disease (ILD). Ultimately, 671 (63.1%) underwent transplant, while 334 (31.4%) died or were delisted. The transplant rate per person-years on the waitlist on ECMO was 15.41 for OLD, 6.05 for PAH, 15.66 for CF, and 15.62 for ILD.

Compared to PAH patients, OLD, CF, and ILD patients were 78%, 69%, and 62% more likely to undergo transplant throughout the study period, respectively (adjusted SHRs 1.78 p = 0.007, 1.69 p = 0.002, and 1.62 p = 0.001). The median LAS at waitlist removal for transplantation, death, or delisting were 75.1 for OLD, 79.6 for PAH, 91.0 for CF, and 88.3 for ILD (p < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Among patients bridging to transplant on ECMO, patients with PAH had a lower transplantation rate than patients with OLD, CF, and ILD.

Keywords: lung transplant, ECMO, pulmonary hypertension, advanced lung disease, lung allocation score

Prior to 2005, lung allocation in the United States was prioritized by length of time on the waitlist, with additional benefit given to patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).1,2 In May 2005 the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN), operated by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), adopted the lung allocation score (LAS) to allocate organs based on severity of illness and the likelihood of post-transplant survival.2 This priority-based system has led to more lung transplants being performed and decreased waitlist mortality, with similar post-transplant survival.3,4 However, there was also a significant change in the distribution of organs based on underlying diagnosis, and not all patients benefitted equally.3–5

The introduction of the LAS system increased the likelihood of transplantation for all diagnoses, but patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) are less likely to be transplanted than those with IPF or cystic fibrosis (CF).5 Waitlist mortality improved for patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and CF, but this effect is not clear for patients with PAH.5,6 These disparities are partially mediated by patients with PAH having relatively low LAS, and the LAS being a poor predictor of mortality in PAH.4,5,7,8 It has been formally recognized that the LAS does not adequately capture disease severity of PAH despite modifications to the score—in February of 2015 bilirubin was included to address PAH severity—so exception criteria have been established for PAH patients with worsening hemodynamics to have their LAS increased to the 90th percentile.9,10 However, not all exceptions are granted, and among PAH patients with a denied request have increased mortality compared to those with an approved exception, highlighting the prognostic impact of a higher LAS.11

Since the LAS system allocates organs based largely on disease severity, there has been a steady rise in pre-trans-plant LAS and clinical acuity on the waiting list.12–14 As a result, since 2005 the use of ECMO bridging has increased by 271%.15,16 Despite this increase in use—and the need for ECMO representing end-stage pathology without transplantation—ECMO status is not specifically incorporated into the LAS and is instead approximated as requiring mechanical ventilation with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 1.0.17–19 Additionally, veno-venous (VV) ECMO is not differentiated from veno-arterial (VA) ECMO.

To our knowledge, prior investigations of the UNOS registry utilized information about ECMO that was recorded at the time of listing or transplantation. However, this approach excludes patients who are initiated on ECMO after listing and did not receive a transplant. In 2015, UNOS began capturing data about ECMO use for all patients at the time of removal from the waitlist for any reason.20 This allows for a more accurate and complete analysis of outcomes on the waitlist for patients bridged with ECMO to lung transplantation.

Given the disparities in LAS and waitlist outcomes across diagnosis groups, it is possible that patients supported on ECMO have differential survival and transplantation rates based on their underlying diagnoses; however this has not been previously investigated. We hypothesized that among waitlist patients supported on ECMO, those with group B diagnoses (i.e., PAH) would have decreased transplantation rates compared to patients with other diagnoses owing to lower LAS.

Methods

Study design, participants, and data sources

This is a retrospective cohort study of all adults and adolescents greater than 12 years old who were active on the waitlist for lung transplant in the United States from June 1, 2015 through June 12, 2020, and who were receiving ECMO support as a bridge to transplantation. The starting date of the study was chosen because UNOS mandated that all sites report data on ECMO status at the time of removal from the waitlist beginning June 1, 2015. Patients were excluded from this study if data were missing about diagnosis group, if the LAS was missing or listed as zero, or if there was no information available about the timing of ECMO initiation.

All data were obtained from the UNOS and OPTN database, including demographic, clinical, and outcome data. This research was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board, and was conducted in compliance with the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplant ethics statement.

Measurements and outcomes

The primary predictor variable was diagnosis grouping as defined in the LAS calculation.2 Group A includes obstructive lung diseases (OLD) such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and non-CF bronchiectasis, group B includes PAH, group C includes CF, and group D includes IPF and ILD.2 Hereafter, the diagnosis groups will be referred to by the predominant representative diagnosis. The patient time was calculated as time from ECMO implantation until removal from the waitlist for clinical deterioration, death, transplantation, or another documented reason. Outcomes were available for all patients since UNOS data for patients on ECMO was reported at the time of waitlist removal. Patients with outcomes other than transplantation, death, or removal for clinical worsening were included in the analysis and censored at the time of waitlist removal. A sensitivity analysis was performed to examine likely outcomes for these patients.

The primary outcome was transplantation rate during the study period. Secondary outcomes were post-transplant survival, LAS at the time of waitlist removal, and risk of death or removal from the waitlist for clinical deterioration. For the primary outcome, and the risk of death or removal from the waitlist, the risk was calculated over the entire study period accounting for the competing risk of transplant. Post-transplant survival was censored at the end of the study period on June 12, 2020.

Analytical approach

Baseline characteristics across diagnoses were examined using ANOVA testing, the Kruskal-Wallis test, and the chi-squared statistic. The primary outcome of risk of transplantation was examined using a multivariable competing risk regression based on Fine and Gray’s proportional subdistribution hazards model.21 The competing risk model was adjusted for the following variables based on plausible associations with the risk of transplantation and a directed acyclic graph (DAG) used to select covariates: age, blood group, height, and listing for double lung transplant only (Figure S1).22 A sensitivity analysis was conducted including adjustment for additional precision variables. LAS and ECMO configuration were not adjusted for in the model, because we hypothesized that they would be mediators of the primary outcome. Furthermore, we hypothesized that among ECMO patients, PAH patients would have lower LAS scores, and that this would contribute to lower transplantation rates. The secondary outcome of risk of death or removal from the waitlist was also examined using adjusted competing risk regression.

The LAS at time of transplantation were compared using Kruskal-Wallis testing, and included scores that were granted by exception. Unadjusted post-transplant survival was analyzed using a Kaplan-Meier analysis. There was a violation of the proportional hazards assumption when assessing mortality based on diagnosis, so instead of using a Cox proportional hazards model, post-trans-plant survival, adjusting for age, sex, and double lung transplant status, was assessed using Royston and Parmar’s (RP) flexible parametric modeling using cubic splines.23,24 This model allows for a changing hazard over time rather than assuming a proportional hazard ratio throughout the analysis period. Knot selection was optimized using Akaike and Bayseian information criteria (Table S1). Analyses were performed in STATA/IC version 16.1 (StataCorp, LP) using stcrreg, stcox, and stpm2.

Results

Patient characteristics

There were 1064 waitlist candidates who required ECMO support as a bridge to lung transplant during the study period and met inclusion criteria (Figure S2). The median age was 52 years (IQR 37–60), and 464 (43.6%) were female. Forty (3.8%) patients had OLD diagnoses, 97 (9.1%) had PAH, 138 (13.0%) had CF, and 789 (74.1%) had ILD. There were notable differences in age, sex, race, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), and proportion of patients listed for only double-lung transplant across the diagnosis groups, which is consistent with the differing epidemiology and clinical characteristics of the representative conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics for 1,064 Lung Transplant Candidates Supported on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

| Obstructive lung disease – Group A | Pulmonary arterial hypertension – Group B | Cystic fibrosis – Group C | Interstitial lung disease – Group D | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of candidates | 40 | 97 | 138 | 789 | N/A |

| Age, median (IQR) | 55 (48–63) | 39 (27–53) | 27 (22–32) | 55 (46–62) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 21 (53) | 73 (75) | 88 (64) | 282 (36) | <0.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| White | 24 (60) | 58 (60) | 113 (82) | 503 (64) | <0.001 |

| Black | 12 (30) | 16 (17) | 8 (6) | 111 (14) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (5) | 14 (14) | 16 (12) | 126 (16) | |

| Other | 2 (5) | 9 (9) | 1 (1) | 49 (6) | |

| BMI at listing, median (IQR) | 23.8 (20.0–26.9) | 23.5 (21.0–28.1) | 20.1 (17.7–22.1) | 27.0 (24.1–30.4) | <0.001 |

| Last LAS, median (IQR) | 75.1 (69.7–78.9) | 79.6 (75.6–83.1) | 91.0 (90.4–91.7) | 88.3 (86.5–89.9) | <0.001 |

| Last LAS, n (%) | |||||

| <70 | 10 (25) | 13 (13) | 8 (6) | 26 (3) | <0.001 |

| 70–79.9 | 23 (57.5) | 31 (32) | 4 (3) | 12 (2) | |

| 80–89.9 | 5 (12.5) | 48 (50) | 16 (12) | 568 (72) | |

| ≥90 | 2 (5) | 5 (5) | 110 (80) | 183 (23) | |

| Double lungs only, n (%) | 26 (65) | 86 (89) | 127 (92) | 501 (63.5) | <0.001 |

| Height cm, median (IQR) | 167 (160–173) | 165 (155–170) | 165 (155–170) | 170 (163–178) | <0.001 |

| Blood type, n (%) | |||||

| O | 20 (50) | 49 (50.5) | 64 (46) | 407 (52) | 0.595 |

| A | 16 (40) | 28 (29) | 53 (38) | 260 (33) | |

| B | 3 (7.5) | 15 (15.5) | 17 (12) | 81 (10) | |

| AB | 1 (2.5) | 5 (5) | 4 (3) | 41 (5) | |

| ECMO mode n (%) | |||||

| VV | 27 (67.5) | 16 (17) | 102 (74) | 478 (61) | <0.001 |

| VA | 8 (20) | 71 (73) | 10 (7) | 187 (24) | |

| VV → VA | 1 (2.5) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 16 (2) | |

| VA → VV | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 19 (2) | |

| Unknown | 4 (10) | 8 (8) | 20 (15) | 89 (11) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IQR, inter-quartile range; LAS, lung allocation score; VA, veno-arterial; VV, veno-venous.

Of the 1064 patients, 644 (60.5%) required initial support with VV ECMO, while 299 (28.1%) initially required VA ECMO. Patients with PAH were significantly more likely to require VA ECMO than patients with other diagnoses (p < 0.001), and patients with CF were the least likely to require VA ECMO. There was no significant difference across diagnosis groups for requiring a change in ECMO configuration. Patients whose initial ECMO configuration was VA were more likely to die or be delisted than patients who initially required VV ECMO (Sub-distribution hazard ratio [SHR] 1.59, 95% CI 1.26–2.00), and less likely to be transplanted (SHR 0.61, 95% CI 0.50–0.73; 16.74 transplants per person-year on ECMO on the waitlist for VV vs 9.13 for VA, p < 0.001). Patients with OLD, CF and ILD had decreased transplant rate and increased risk of death on VA ECMO compared to VV, but PAH patients had similar outcomes (Table S2).

The median time spent on the waitlist while supported on ECMO was 8 days (IQR 4–17, range 0–257). A total of 671 (63.1%) waitlist candidates underwent transplantation during the study period, while 172 (16.2%) died, and 162 (15.2%) were removed from the waitlist for clinical worsening. There were 12 patients (1.1%) who improved and no longer required transplant— 11 of them had ILD and 1 had PAH. There were 44 patients (4.1%) whose outcomes were unknown and documented as “other” at the time of waitlist removal; 1 OLD, 16 PAH, 5 CF, and 22 ILD. Bilateral lung transplant was performed in 615 patients (92.1% of transplants).

Primary outcome

In competing risk analysis, patients with PAH were less likely to be transplanted throughout the entire study period than patients with any other diagnosis (Figure 1). During the study period, 49.5% of PAH patients received a transplant after bridging with ECMO support (48/97) with a transplant rate of 6.05 transplants per person-year on ECMO on the waitlist, compared to 72.5% of OLD patients (29/40) with a transplant rate of 15.41, 73.9% of CF patients (102/138) with a transplant rate of 15.66, and 62.4% of ILD patients (492/789) with a transplant rate of 15.62 (Figure 2). Relative to patients with PAH, OLD patients were 78% more likely to undergo transplant (adjusted SHR 1.78, 95% CI 1.17–2.71), CF patients were 69% more likely (adjusted SHR 1.69, 95% CI 1.22–2.34) and ILD patients were 62% more likely (adjusted SHR 1.62, 95% CI 1.21–2.17) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of transplantation by diagnosis group, unadjusted. ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted transplant rate and median lung allocation score by diagnosis. LAS, lung allocation score.

Table 2.

Transplant Rates Compared Across Diagnosis Groups

| Outcome | Obstructive lung disease – Group A n = 40 |

Pulmonary arterial hypertension – Group B n = 97 |

Cystic fibrosis – Group C n = 138 |

Interstitial lung disease – Group D n = 789 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transplantation, No. (%) | 29 (72.5) | 48 (49.5) | 102 (73.9) | 492 (62.4) |

| Transplant rate, transplants per person years on waitlist on ECMO | 15.41 | 6.05 | 15.66 | 15.62 |

| Unadjusted SHR for transplant (95% CI) | 1.63 (1.08–2.48) | 1 | 1.83 (1.33–2.53) | 1.51 (1.13–2.02) |

| Adjusteda SHR for transplant | 1.78 (1.17–2.71) | 1 | 1.69 (1.22–2.34) | 1.62 (1.21–2.17) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenatation; SHR, sub-distribution hazard ratio.

The bold values are statistically significant based on the statistical analysis used (i.e. the confidence interval does not cross 1, and the p-value was <0.05).

Adjusted for age at the time of waitlist activation, ABO blood type, height, and listing only for double lung transplant.

Secondary outcomes

The risk of death or removal from the waitlist for clinical deterioration was similar between diagnosis groups (Figure S3, Table S3). Given that a patient’s LAS determines his or her priority on the waiting list, the final LAS, including exception scores, were compared between diagnosis groups. The median LAS at the time of waitlist removal for the entire cohort was 88.2 (IQR 85.4–90.2). The median LAS at time of waitlist removal was 75.1 for OLD patients, 79.6 for PAH patients, 91.0 for CF patients, and 88.3 for ILD patients (p < 0.001 for between group comparisons) (Figure 2). Exception scores were granted to 16 patients; 2 patients with OLD had an average LAS increase of 8.1, 9 PAH patients increased an average of 24.7, 1 CF patient increased 4.2, and 4 ILD patients increased an average of 39.5.

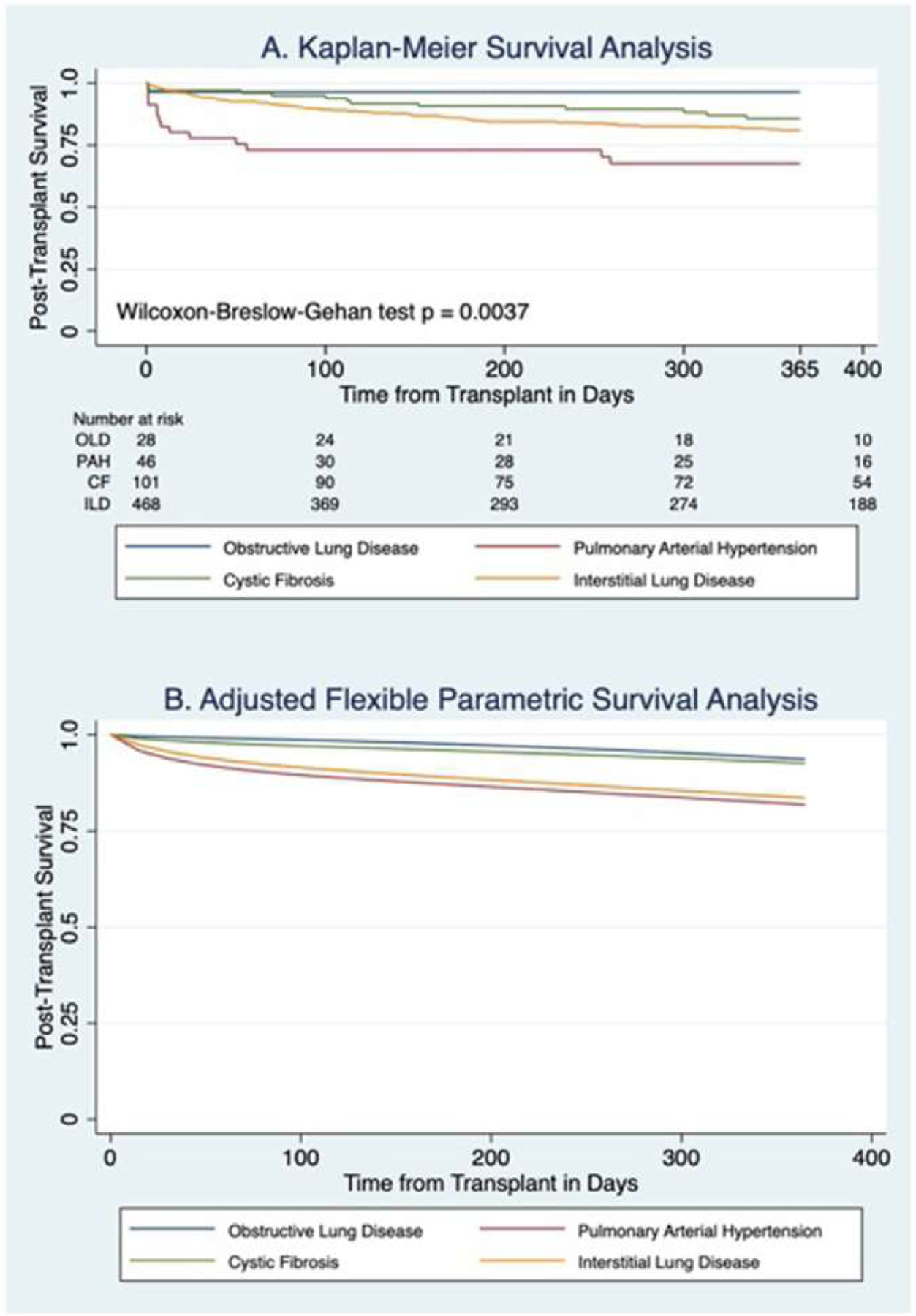

The median follow up time post-transplant was 367 days (IQR 165–743), and follow up time beyond 1 year was available for 51.2% of patients. Median follow up time was significantly longer for CF patients compared to all other groups (562 days for CF vs 363.5 days for OLD, 348.5 days for PAH, and 366 days for ILD, p = 0.0136). There was a significant difference in 1 year post-transplant survival by diagnosis using an unadjusted Kaplan-Meier analysis with Wilcoxon-Breslow-Gehan testing (p = 0.0037) (Figure 3A). This model was unadjusted, and violated proportional-hazards assumption, so additional survival analysis was performed. In a RP flexible parametric survival model adjusted for age, sex, and receiving a double lung transplant, there was no statistically significant difference in of the hazard ratio for death at 1 year post-transplant (Figure 3B, Table 3). Notably, patients with PAH and ILD had relatively high early post-transplant mortality, and patients with CF and OLD had statistically significantly improved survival at 30 days post-transplant compared to PAH patients (Table 3). However, at 1 year post-transplant there were no differences between diagnoses in the hazard ratios for mortality (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Post-transplant survival by diagnosis group (A) Kaplan-Meier curve for unadjusted, analysis censored at 1 year (B) Flexible parametric survival analysis censored 1 year post-transplant. Parametric survival analysis is adjusted for age, sex, and double lung transplant. CF, cystic fibrosis; ILD, interstitial lung disease; OLD, obstructive lung disease; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Table 3.

Post-Transplant Survival and Hazard Ratios at 30 Days and 1 Year Post-Transplant

| Obstructive lung disease – Group A | Pulmonary arterial hypertension – Group B | Cystic fibrosis – Group C | Interstitial lung disease – Group D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 day survival rate (95% CI) | 0.99 | 0.94 (0.92–0.96) | 0.98 | 0.96 |

| (0.98–1.00) | (0.97–0.998) | (0.94–0.97) | ||

| HR at 30 days (95% CI) | 0.10 | 1 | 0.20 | 0.48 |

| (0.02–0.65) | (0.06–0.63) | (0.21–1.07) | ||

| 1 year survival rate (95% CI) | 0.94 | 0.82 (0.79–0.85) | 0.93 | 0.84 |

| (0.87–1.00) | (0.88–0.97) | (0.80–0.87) | ||

| HR at 1 year (95% CI) | 1.57 | 1 | 0.93 | 1.56 |

| (0.50–4.98) | (0.35–2.46) | (0.64–3.80) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

The bold values are statistically significant based on the statistical analysis used (i.e. the confidence interval does not cross 1, and the p-value was <0.05).

Sensitivity analyses

There were 44 patients with a waitlist removal reason of “other.” These patients’ outcomes are unknown, however it is implausible that they were transplanted without it being documented by UNOS. Sensitivity analyses were performed assuming all of these patients died or were removed for clinical deterioration, or excluding them from the cohort entirely. If all of these patients died or worsened, then PAH patients would have increased risk of death / removal from the waitlist and decreased rate of transplant compared to all other diagnosis groups (Table 4). When these patients were excluded from the cohort entirely, PAH patients had decreased transplantation compared to patients with all other diagnoses, and there was no difference in the risk of death or removal from the waitlist.

Table 4.

Sensitivity Analysis with Competing Risk Regression Analyses Performed with Different Assumptions for 44 Patients with a Final Waitlist Outcome of “Other”

| Obstructive lung disease – Group A | Pulmonary arterial hypertension – Group B | Cystic fibrosis – Group C | Interstitial lung disease – Group D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR transplanta | SHR death/removala | SHR transplanta | SHR death/removala | SHR transplanta | SHR death/removala | SHR transplanta | SHR death/removala | |

| Assuming all “other” outcome patients died or were removed | 1.89 p = 0.003 |

0.46 p = 0.020 |

1 | 1 | 1.84 p < 0.001 |

0.55 p = 0.007 |

1.73 p = 0.001 |

0.61 p < 0.001 |

| Excluding all “other” outcome patients from the analysis | 1.53 p = 0.045 |

0.57 p = 0.107 |

1 | 1 | 1.45 p = 0.025 |

0.75 p = 0.229 |

1.42 p = 0.016 |

0.76 p = 0.146 |

Abbreviation: SHR, sub-distribution hazard ratio.

The bold values are statistically significant bases on the statistical analysis used (i.e. the confidence interval does not cross 1, and the p-value was <0.05).

Adjusted for initial age, ABO blood type, height, and listing only for double lung transplant.

We selected covariates for our primary analyses using a DAG, and we conducted a sensitivity analysis including additional precision variables in the model. These variables were sex, race / ethnicity, and center volume of ECMO-bridge-to-transplant patients. This sensitivity analysis had the same findings as the primary analysis with PAH patients having lower transplant rates than patients with all other diagnoses (Table S4). Additional sensitivity analysis evaluating an OPTN / UNOS policy change in 2017 is included in the supplement.25,26

Discussion

PAH patients bridged to transplant with ECMO were less likely to be transplanted than patients with OLD, CF, or ILD. This is despite PAH patients having similar post-transplant survival at 1-year compared patients with other diagnoses on adjusted analysis. This study demonstrates that there are disparate waitlist outcomes for patients bridged to transplant with ECMO.

The LAS system is designed to be priority-based and allocate organs according to need and potential benefit; however, it has created inequalities in the distribution of organs based on underlying diagnosis.2,3,5 Specifically, patients with PAH have seen less benefit and have worse waitlist outcomes than those with other diagnoses.5,27,28 Patients with PAH often have lower LAS due to the criteria incorporated in the formula, and the LAS is generally a poor predictor of mortality in patients with PAH.4,5,7,27 While specific exception score criteria have been outlined for PAH patients, a significant proportion of these requests are denied, and PAH patients have worse outcomes after an exception denial than patients with other diagnoses.11

There has been a marked increase in the use of ECMO as a bridge to transplant in the last decade, and thus evaluation of organ distribution among these patients is clinically important.15,16 Despite the increase in use, ECMO status, regardless of configuration, is not specifically incorporated into the LAS, and is instead approximated as requiring mechanical ventilation.17–19 This may further disadvantage patients with PAH who, as discussed, often have lower LAS, and who more often require VA ECMO.

PAH patients had a lower final LAS compared to CF and ILD patients even when accounting for exception scores. This difference was most notable when looking at the extremes of LAS in this cohort as only 5% of patients with PAH had an LAS > 90 compared to 80% of CF patients and 23% of ILD patients. Of note, patients with OLD had similar final LAS to PAH patients, but still had significantly increased rate of transplantation, so it is clear the disparity in outcome is not entirely explained by LAS.

Interestingly, candidates requiring VA ECMO compared with those on VV ECMO had decreased transplant rates and increased risk of death or delisting across all diagnosis groups except PAH. However, the vast majority of PAH patients bridging to transplant utilized VA ECMO rather than VV, and typically pulmonary hypertension is considered an indication for VA ECMO support.28 Therefore, the small number of PAH patients supported on VV ECMO were likely highly selected for this configuration—for example, PAH patients with an atrial septal defect—making comparing outcomes difficult.29 The increased mortality among patients requiring VA ECMO support in this cohort may be explained by those patients having more severe disease that requires both cardiac and respiratory support, challenges to mobilization and physical therapy on VA ECMO, and because VA ECMO has a higher complication rate in general.30 Since PAH patients were more likely to require VA ECMO, this likely contributes to the difference in transplant rates seen between diagnoses. We did not adjust for ECMO configuration in the analysis because we believe the type of support is intrinsically linked to the underlying diagnosis, and as a mediator of the outcome rather than a confounder. Further analysis is warranted to examine the potential effect of incorporating ECMO status and configuration into the LAS on waitlist mortality, transplant rate and post-transplant survival.

Patients with PAH bridging to transplant on ECMO had increased early risk of death post-transplant, but similar post-transplant risk of death at 1 year compared to patients with OLD, CF, and ILD. While PAH patients had poor early post-transplant outcomes and increased hazard ratio of death compared to CF and OLD patients at 30 days post-transplant, the survival disparity narrowed after the acute perioperative period and the hazard ratios for mortality at 1 year post transplant were similar between all diagnoses. These findings reflect known trends seen among lung transplant patients and are not specific to those bridging to transplant with ECMO.31,32 Since post-transplant outcomes became more congruous over time, the worse early post-transplant outcomes for PAH patients does not justify the disparity seen in LAS or transplant rate.

Our primary finding was consistently demonstrated on sensitivity analyses. For patients with a waitlist removal code of “other” true outcomes are unknown; however, it seems unlikely that these patients were ultimately transplanted without this information being captured in the UNOS database. In the liver transplant literature it has been reported that patients are often misclassified and coded as removed from the waitlist for “other” reasons, but in fact had died or were removed from the list for clinical worsening.33 It is likely a safe assumption that patients with this designation ultimately died or were delisted, and in this scenario patients with PAH had decreased risk of transplant and increased risk of death or removal from the waitlist for clinical deterioration compared to all other diagnoses.

There are several limitations in this analysis. All analyzed data were obtained from OPTN/UNOS and there may be missing information and inaccuracies in this database based on the quality of documentation and reporting. This includes missing information about outcome, which was specifically addressed in the above sensitivity analysis. We did not address predictors of waitlist outcomes that are not collected by OPTN/UNOS. While we included as many patient records as possible, the sample size is small for certain subgroups within the dataset, such as the relatively few patients with OLD, and the relatively small proportion of patients who died on the waitlist. Therefore, there is the possibility for Type II statistical error in the analysis on waitlist mortality, and for lack of power in drawing conclusions about differences in LAS; large, prospective follow-up studies are necessary. We did not have information available about mechanical ventilation or sedation while on ECMO, which may be important co-factors. Finally, we did not include waitlist candidates younger than age 12, because lungs are allocated by a different system in this age group.34

In summary, patients with PAH bridging to transplant on ECMO have lower transplantation rates than patients with OLD, CF, and ILD. Differences in LAS and the type of ECMO support required between diagnoses may explain this discrepancy. These findings, in combination with prior studies showing disparities in outcomes in the LAS era based on diagnosis, warrant further attention.2,3,5,10,11 One strategy for mitigating these disparities may be incorporating ECMO status and configuration specifically in the LAS, and adjusting for the impact ECMO has on survival based on underlying diagnosis. Future studies could illuminate the impact of such a modification.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure statement

MA is supported by National Institutes of Health grant: K23 HL150280. This funding is unrelated to this manuscript. The remaining authors have no financial conflicts of interest or financial attachments to disclose in relation to this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2021.08.005.

References

- 1.Orens JB, Shearon TH, Freudenberger RS, et al. Thoracic organ transplantation in the United States, 1995–2004. Am J Transplant 2006;6(5 Pt 2): 1188–97. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egan TM, Murray S, Bustami RT, et al. Development of the new lung allocation system in the United States. Am J Transplant 2006;6(5 Pt 2):1212–27. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egan TM, Edwards LB. Effect of the lung allocation score on lung transplantation in the United States. J Heart Lung Transplant 2016;35:433–9. 10.1016/j.healun.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hachem RR, Trulock EP. The new lung allocation system and its impact on waitlist characteristics and post-transplant outcomes. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;20:139–42. 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H, Shiboski SC, Golden JA, et al. Impact of the lung allocation score on lung transplantation for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:468–74. 10.1164/rccm.200810-1603OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaffer JM, Singh SK, Joyce DL, et al. Transplantation for idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: improvement in the lung allocation score era. Circulation 2013;127:2503–13. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benza RL, Miller DP, Frost A, Barst RJ, Krichman AM, McGoon MD. Analysis of the lung allocation score estimation of risk of death in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension using data from the REVEAL Registry. Transplantation 2010;90:298–305. 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181e49b83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomberg-Maitland M, Glassner-Kolmin C, Watson S, et al. Survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients awaiting lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013;32:1179–86. 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preparing your patients for changes to the lung allocation system - OPTN. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/news/changes-to-the-lung-allocation-system/

- 10.Chan KM. Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and equity of donor lung allocation in the era of the lung allocation score: are we there yet? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:385–7. 10.1164/rccm.200906-0976ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wille KM, Edwards LB, Callahan LR, McKoy AR, Chan KM. Characteristics of lung allocation score exception requests submitted to the national Lung Review Board. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:812–4. 10.1016/j.healun.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valapour M, Skeans MA, Heubner BM, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2013 annual data report: lung. Am J Transplant 2015;15(S2):1–28. 10.1111/ajt.13200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawford TC, Grimm JC, Magruder JT, et al. Lung transplant mortality is improving in recipients with a lung allocation score in the upper quartile. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;103:1607–13. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayanga JA, Lira A, Vlahu T, et al. Lung transplantation in patients with high lung allocation scores in the US: evidence for the need to evaluate score specific outcomes. J Transplant 2015;2015:836751. 10.1155/2015/836751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayanga JWA, Hayanga HK, Holmes SD, et al. Mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to lung transplantation: closing the gap. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019;38:1104–11. 10.1016/j.healun.2019.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tipograf Y, Salna M, Minko E, et al. Outcomes of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;107:1456–63. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason DP, Thuita L, Nowicki ER, Murthy SC, Pettersson GB, Blackstone EH. Should lung transplantation be performed for patients on mechanical respiratory support? The US experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;139:765–773.e1. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dussault NE, Katsis JM, Garrity ER, Churpek MM, Parker WF. Calculating the lung allocation score error for ECMO patients. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020;39:S141–2. 10.1016/j.healun.2020.01.1059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LAS Calculator - OPTN. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/resources/allocation-calculators/las-calculator/

- 20.Change requiring collection of data at time of removal for lung candidates supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) now effective. UNOS. Published April 14, 2016. Accessed March 13, 2021. https://unos.org/news/collection-of-data-at-time-of-removal-for-lung-candidates/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Statist Assoc 1999;94:496–509. 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lederer DJ, Bell SC, Branson RD, et al. Control of confounding and reporting of results in causal inference studies, guidance for authors from editors of respiratory, sleep, and critical care journals. Annal Am Thoracic Soc 2019;16:22–8. 10.1513/annalsats.201808-564ps. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royston P, Parmar MKB. Flexible parametric proportional-hazards and proportional-odds models for censored survival data, with application to prognostic modelling and estimation of treatment effects. Stat Med 2002;21:2175–97. 10.1002/sim.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Royston P, Lambert P. Flexible Parametric Survival Analysis Using Stata: Beyond the Cox Model. Stata Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.OPTNUNOS Policy Notice Modifications to the Distr.pdf Accessed June 7, 2021. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2539/thoracic_policynotice_201807_lung.pdf

- 26.20180621_thoracic_committee_report_lung.pdf Accessed June 7, 2021. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2517/2018062l_thoracic_committee_report_lung.pdf

- 27.George MP, Champion HC, Pilewski JM. Lung transplantation for pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ 2011;1:182–91. 10.4103/2045-8932.83455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartolome S, Hoeper MM, Klepetko W. Advanced pulmonary arterial hypertension: mechanical support and lung transplantation. Eur Respir Rev 2017;26:170089. 10.1183/16000617.0089-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenzweig EB, Brodie D, Abrams DC, Agerstrand CL, Bacchetta M. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a novel bridging strategy for acute right heart failure in group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension. ASAIO J 2014;60:129–33. 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makdisi G, Wang I. Extra Corporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) review of a lifesaving technology. J Thorac Dis 2015;7: E166–76. 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.07.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC, et al. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-fifth adult heart transplantation report-2018; focus theme: multiorgan transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018;37(10): 1155–68. 10.1016/j.healun.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ISHLT: The International Society for Heart & Lung Transplantation - /. Accessed March 29, 2021. https://ishltregistries.org/registries/slides.asp?yearToDisplay=2019

- 33.David G, Benjamin F, James T, et al. Underreporting of liver transplant waitlist removals due to death or clinical deterioration: results at 4 major centers. Transplantation 2013;96:211–6. 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182970619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sweet SC. Update on pediatric lung allocation in the United States. Pediatr Transplant 2009;13:808–13. 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2009.01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.