Abstract

Background

Children with B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) are at risk for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). Children’s Oncology Group AALL0932 randomized reduction in vincristine and dexamethasone (every 4 weeks vs 12 weeks during maintenance in the average-risk subset of National Cancer Institute standard-B-ALL (SR AR B-ALL). We longitudinally measured CIPN, overall and by treatment group.

Methods

AALL0932 standard-B-ALL patients aged 3 years and older were evaluated at T1-T4 (end consolidation, maintenance month 1, maintenance month 18, 12 months posttherapy). Physical and occupational therapists (PT/OT) measured motor CIPN (hand and ankle strength, dorsiflexion and plantarflexion range of motion), sensory CIPN (finger and toe vibration and touch), function (dexterity [Purdue Pegboard], and walking efficiency [Six-Minute Walk]). Proxy-reported function (Pediatric Outcome Data Collection Instrument) and quality of life (Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory) were assessed. Age- and sex-matched z scores and proportion impaired were measured longitudinally and compared between groups.

Results

Consent and data were obtained from 150 participants (mean age = 5.1 years [SD = 1.7], 48.7% female). Among participants with completed evaluations, 81.8% had CIPN at T1 (74.5% motor, 34.1% sensory). When examining severity of PT/OT outcomes, only handgrip strength (P < .001) and walking efficiency (P = .02) improved from T1-T4, and only dorsiflexion range of motion (46.7% vs 14.7%; P = .008) and handgrip strength (22.2% vs 37.1%; P = .03) differed in vincristine and dexamethasone every 4 weeks vs vincristine and dexamethasone 12 weeks at T4. Proxy-reported outcomes improved from T1 to T4 (P < .001), and most did not differ between groups.

Conclusions

CIPN is prevalent early in B-ALL therapy and persists at least 12 months posttherapy. Most outcomes did not differ between treatment groups despite reduction in vincristine frequency. Children with B-ALL should be monitored for CIPN, even with reduced vincristine frequency.

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood cancer (1). Advances in ALL therapy resulted in excellent outcomes with overall survival exceeding 90% (2), yet survivors remain at risk for late effects from therapy (3). Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a common, sometimes debilitating condition caused by vincristine (4). CIPN impairs critical skills necessary for school and work and can be associated with impaired physical function and quality of life (QOL) (5-8). Despite better ALL risk stratification that decreased treatment toxicity and late effects (9,10), vincristine remains a mainstay of therapy for most ALL patients, and CIPN remains prevalent (11,12).

Although children with ALL are at risk for CIPN, its onset, severity, and resolution posttherapy have not been prospectively evaluated in a multicenter clinical trial. In a 4-site study of 128 pediatric ALL patients on varied protocols evaluated by clinicians, 78% developed CIPN that peaked within 2-4 months, but resolution posttherapy was not evaluated (13). Studies of ALL survivors suggest CIPN persists posttherapy but are limited by small samples or lack of longitudinal data (11,14-17). Further, a major challenge in studying CIPN is the need for specialized clinical assessments by trained providers, which are more sensitive than general provider assessments (18), but have not been previously included in pediatric therapeutic trials. Routinely used toxicity reporting by Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events misses up to 40% of clinically measured CIPN in patients (19), and self-reported symptoms are not sensitive or concordant with clinical evaluations (20). In addition to their increased sensitivity in comparison to symptom reporting, clinical evaluations are also specific to CIPN and are reproducible across settings (13,15,19-21). Clinical evaluation of CIPN by trained providers such as physical and occupational therapists (PT/OT) is therefore needed to assess vincristine toxicity in therapeutic trials. Additionally, understanding the onset and course of CIPN is needed to inform timing of interventions such as physical therapy that can improve symptoms (22,23).

The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AALL0932 Leukemia Physical Function Study (LPFS) was the first study to longitudinally evaluate CIPN using PT/OT evaluations as part of an upfront therapeutic trial. It was embedded in COG AALL0932, a multicenter study that randomly assigned patients to a reduction in vincristine from every 4 weeks to every 12 weeks during maintenance therapy in the average-risk subset of National Cancer Institute (NCI) standard-risk B-ALL (SR AR B-ALL). There was no difference in 5-year disease-free survival between groups (94.1% vs 95.1%; P = .86), and every 12-week dosing is now standard of care (24). Among participants from the LPFS, we aimed to 1) characterize onset, severity, and resolution of CIPN by PT/OT evaluation and 2) determine whether prevalence of CIPN differed between children randomly assigned to every 4- vs 12-week vincristine during maintenance.

Methods

Patients

This prospective study was offered to SR AR B-ALL patients enrolled in COG AALL0932 (NCT01190930) at 32 participating sites (see the Supplementary Methods, available online, for the complete list). Sites with available PT/OT to perform evaluations were selected to ensure high-quality data and included a representative sample of hospital size, academic and community focus, and geographic location. Sites with competing protocols influencing development of neuropathy (such as neuropathy interventions) were excluded. All eligible participants required enrollment on the SR AR B-ALL arm of COG AALL0932 that randomly assigned participants to every 4- vs 12-week vincristine and dexamethasone (VCR/DEX4 vs VCR/DEX12) during maintenance (see Figure 1; Supplementary Figure 1, available online). Average-risk criteria were previously described (Supplementary Box 1, available online) (24). Additional eligibility criteria included those aged 3 years or older at first evaluation with an English- or Spanish-speaking parent. Participants with prior neurodevelopmental disorders (eg, autism, seizures) were excluded. Institutional review board approval at participating institutions and written informed consent (and assent as appropriate) were obtained.

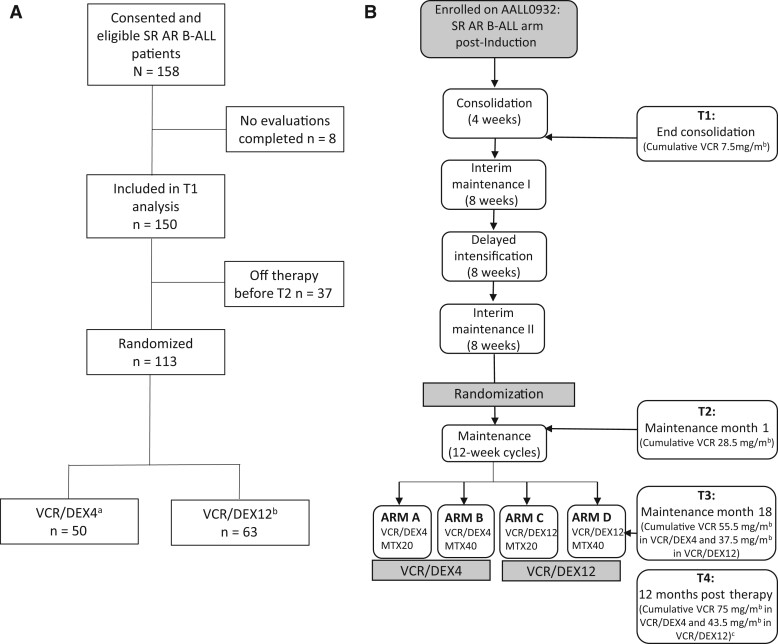

Figure 1.

(A) Consort diagram for participants enrolled on Leukemia Physical Function Study. (B) Study schema and cumulative vincristine dose for SR AR B-ALL arm of Children’s Oncology Group AALL0932. aAssigned cumulative vincristine dose in VCR/DEX4 is 75 mg/m2 in males and 55.5 mg/m2 in females. bAssigned cumulative vincristine dose in VCR/DEX12 is 43.5 mg/m2 in males and 37.5 mg/m2 in females. cVincristine dose at T4 is the cumulative dose for male participants; cumulative dose for females is the same as T3. SR AR B-ALL = average-risk subset of National Cancer Institute standard-risk B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia; T1 = end consolidation; T2 = maintenance month 1; T3 = maintenance month 18; T4 = 12 months posttherapy; VCR/DEX4 = every 4-week vincristine and dexamethasone pulses in maintenance; VCR/DEX12 = every 12-week vincristine and dexamethasone pulses in maintenance.

Study Design

Eligible participants from the average-risk arm of AALL0932 (see Figure 1; Supplementary Figure 1, available online) were offered enrollment. Premaintenance therapy included 18 scheduled vincristine doses (1.5 mg/m2; maximum 2 mg). Participants were randomly assigned at start of maintenance using a 2 × 2 factorial design to 1 of 4 regimens of every 4- or 12-week vincristine (1.5 mg/m2; maximum 2 mg on day 1) with dexamethasone (6 mg/m2 per day on days 1-5) and a starting dose of 20 or 40 mg/m2 per week of oral methotrexate (MTX) for 2 years (girls) or 3 years (boys) from the start of interim maintenance I (24). Because vincristine is associated with CIPN, participants were analyzed by every VCR/DEX4 vs VCR/DEX12. Evaluations occurred at end consolidation (T1), maintenance month 1 (T2), maintenance month 18 (T3), and 12 months posttherapy (T4).

Evaluations and Outcomes

To generalize procedures across sites, each PT/OT received comprehensive video training and achieved more than 90% proficiency by written test. Those who did not initially attain more than 90% proficiency received individualized training. Everyone completed quarterly conference calls and a yearly performance review to ensure ongoing data fidelity. To minimize sedation-related impairment, evaluations were not performed following lumbar punctures. Primary outcomes included sensory and motor CIPN measured by impairment in sensory and motor evaluations below. Secondary outcomes included functional and proxy-reported impairments.

Sensory CIPN

Mechanical pressure and vibration sensation were measured using Semmes Weinstein monofilaments and a 128 Hz Rydel-Seiffer tuning fork (25,26). Light touch was impaired if a 3.22 size/0.16 g force monofilament by index finger or 3.84size/0.6 g force monofilament by plantar great toe was not detected (25). Vibration sensation z scores were calculated in reference to age- and sex-matched population means (26).

Motor CIPN

Dominant handgrip strength was assessed by myometer (Performance Health, Warrenville, IL, USA) in a seated position with elbow flexed at 90 degrees and forearm in neutral position (27). The average of 2 trials was used. Isokinetic ankle dorsiflexion strength was measured using handheld dynamometer with the participant lying supine (Chatillon DFX-II, Chicago, IL, USA) (28), and passive ankle dorsiflexion and plantarflexion range of motion (ROM) were measured by goniometer (29), with the best of both 2 trials on each side averaged (30-32).

Functional Evaluations

Walking efficiency was measured by the Six-Minute Walk Test. Participants were instructed by standardized script to walk as fast as possible for 6 minutes with distance recorded (33). Manual dexterity was measured by Purdue Pegboard. Participants were instructed through standardized script to place pegs in a pegboard for 30 seconds, with number of pegs recorded (34).

Proxy-reported Assessments

Parents or guardians completed validated proxy-report instruments, the Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument (PODCI), and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales (PedsQL) (35,36). PODCI measures of physical function in children with musculoskeletal conditions, subconstructs upper extremity function, transfer/mobility, and sports/physical function were analyzed (35). PedsQL measures QOL in children with cancer including a physical health subscale (36,37).

Evaluation of Severity and Impairment

Z scores were calculated in reference to mean age- and sex-matched population values (26-29,33-35). Impairment was defined as z score less than 1.3 for PT/OT outcomes and PODCI domains (indicating function below the 10th percentile of the general population) (16). Impairment on the PedsQL was defined as a z score less than -2.0 as a conservative approach to avoid misclassification of somatic complaints in children with cancer as previously described (36,37).

Analysis

Demographics (see Table 1) were compared between VCR/DEX4 and VCR/DEX12 as were demographics and T1 impairment between participants who were randomly assigned vs dropped out prerandomization and who completed vs did not complete T4. Impairment was compared between males and females at T4 because of difference in cumulative vincristine doses and time since therapy initiation. All frequency comparisons used Fisher exact tests.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics overall and by treatment arm at enrollment

| Characteristic | Overalla | VCR/DEX4 | VCR/DEX12 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 150) | (n = 50) | (n = 63) | |

| Age, No. (%), y | |||

| <5 | 86 (57.3) | 32 (64.0) | 37 (58.7) |

| 5-6.9 | 41 (27.3) | 12 (24.0) | 20 (31.8) |

| 7-9.9 | 23 (15.3) | 6 (12.0) | 6 (9.5) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Male | 77 (51.3) | 22 (44.0) | 41 (65.1) |

| Female | 73 (48.7) | 28 (56.0) | 22 (34.9) |

| Race, No. (%) | |||

| Other | 15 (10.0) | 6 (12.0) | 6 (9.5) |

| Unknown | 27 (18.0) | 5 (10.0) | 16 (25.4) |

| White | 108 (72.0) | 39 (78.0) | 41 (65.1) |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 39 (26.0) | 16 (32.0) | 17 (27.0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 108 (72.0) | 34 (68.0) | 44 (69.8) |

| Unknown | 3 (2.0) | — | 2 (3.2) |

| Methotrexate dose, No. (%)b | |||

| 20 mg/m2 | 57 (50.4) | 26 (52.0) | 31 (49.2) |

| 40 mg/m2 | 56 (49.6) | 24 (48.0) | 32 (50.8) |

The overall count includes 37 patients who consented to the study and had data from time-point 1 that was analyzed but went off therapy prior to randomization (comparisons between randomly assigned and not randomly assigned participants shown in Supplementary Table 1, available online). VCR/DEX4 = every 4-week vincristine and dexamethasone pulses in maintenance; VCR/DEX12 = every 12-week vincristine and dexamethasone pulses in maintenance.

Methotrexate dose indicates starting dose of methotrexate and is only available for randomized participants.

Z scores with standard deviations and proportions of participants with impaired outcomes were calculated for each time-point based on age- and sex-matched mean population values. Children aged younger than 4 years were excluded from vibration, ankle strength, and walking efficiency analyses because of absence of published age-matched means for these outcomes (26,28,33). Linear mixed effects models with unstructured covariance structure were used to model Z scores across time-points while accounting for within-person correlations in longitudinal data. Wald tests with Satterthwaite degrees of freedom corrections were used to compare average Z scores at each time-point in reference to T1. Similar models and tests were used to examine post-T2 group differences across time. Prevalence of impairment in the sample was compared with expected age- and sex-matched population impairment based on normative data using 1-sided 1-sample test of proportions, and odds of impairment were compared between VCR/DEX4 and VCR/DEX12 atT3 and T4 (postintervention) controlling for T2 using the generalized estimating equation approach for binary repeated measures (38). All tests used a .05 statistical significance level and were 2-sided unless otherwise specified.

Results

Participant Characteristics

From October 2011 to March 2013, 158 participants enrolled on the LPFS from 32 institutions; 8 participants were never evaluated (Figure 1) resulting in 150 analyzed, with an average age at diagnosis of 5.1 years (SD = 1.7). Thirty-seven participants left the therapeutic study premaintenance prior to being randomly assigned, resulting in 113 analyzed by treatment group (VCR/DEX4 n = 50, VCR/DEX12 n = 63). There were more females in VCR/DEX4 than VCR/DEX12 (56.0% vs 34.9%), but other demographics (Table 1) and reported use of PT/OT services and Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events toxicities requiring vincristine dose modification were similar between groups (24). There was no statistically significant difference in T1 impairment between randomly assigned participants and those who dropped out prerandomization (Supplementary Table 1, available online) or between participants who completed vs did not complete T4 (Supplementary Table 2, available online). There was no statistically significant difference in outcomes between males and females at T4 (Supplementary Table 3, available online).

Impairment by PT/OT Evaluation

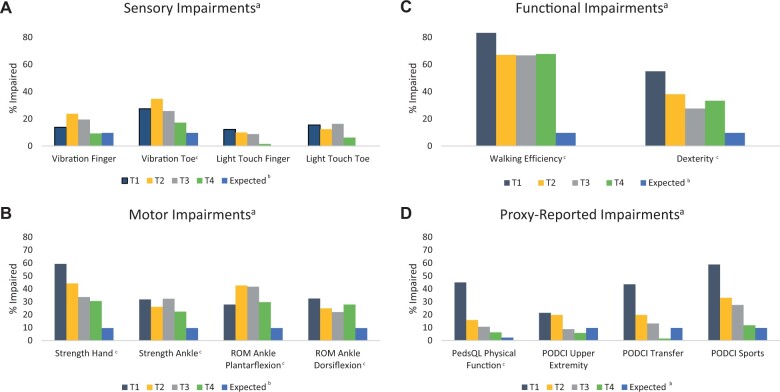

Number of completed evaluations by time-point are shown in Supplementary Table 4 (available online). Among participants analyzed at T1, 81.8% had at least 1 motor or sensory impairment (74.4% motor, 34.1% sensory). The most prevalent PT/OT impairments included handgrip strength (59.3%), dexterity (55.0%), and walking efficiency (83.3%) (Figure 2). At T4, 67.6% of participants analyzed had at least 1 motor or sensory impairment (61.8% motor, 25.0% sensory). Prevalence of impairment remained higher in participants than expected population norms 12 months posttherapy for all PT/OT outcomes except finger vibration sensation.

Figure 2.

Proportion of participants with impaired A) motor, B) sensory, C) functional, and D) proxy-reported outcomes at T1 (end consolidation) through T4 (12 months posttherapy) compared with expected population impairment. aN for each evaluation is displayed in Supplementary Table 4 (available online). bExpected population impairment was calculated based on z score cutoffs used to define impairment and was 9.7% for z scores less than −1.3 and 2.3% for z scores less than −2.0. Expected population impairment was not calculated for dichotomous variables (light touch sensation). cIndicates proportion impaired was statistically significantly higher in study population at T4 than expected population impairment at a statistical significance level of .05. PedsQL = Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales; PODCI = Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument; ROM = range of motion; T1 = end consolidation; T2 = maintenance month 1; T3 = maintenance month 18; T4 = 12 months posttherapy.

Longitudinal Severity of Impairment

Peak severity of impairment, measured by mean z score, varied by outcome (Table 2). Most severe impairment at T1 was in strength (handgrip, ankle), plantarflexion ROM, walking efficiency, and dexterity. Most severe impairment in vibration sensation and dorsiflexion ROM occurred at T2. The only PT/OT outcomes that statistically significantly improved from T1 to T4 were handgrip strength (P < .001) and walking efficiency (P = .02). There were no new statistically significant findings, and patterns remained similar when comparing T2 to T4 outcomes.

Table 2.

Mean z score for sensory, motor, functional, and proxy-reported outcomes in all participants in reference to age- and sex-matched population mean values

| Outcome | T1 (n = 150)a | T2 (n = 107)a | T3 (n = 100)a | T4 (n = 73)a | P | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean z score (SD) | Mean z score (SD) | Mean z score (SD) | Mean z score (SD) | (T1vT4)b | (T2vT4)b | |

| Sensory | ||||||

| Vibration index finger | −0.12 (1.74) | −0.98 (3.85) | −0.36 (2.94) | −0.22 (3.18) | .75 | .27 |

| Vibration great toe | −0.36 (1.84) | −1.57 (4.30) | −1.06 (4.26) | −1.09 (6.96) | .42 | .69 |

| Motor | ||||||

| Strength, handgrip, kg | −1.49 (1.05) | −1.01 (1.11) | −0.80 (1.00) | −0.67 (1.28) | <.001 | .04 |

| Strength, ankle dorsiflexion, kg | −0.51 (1.77) | −0.02 (2.19) | −0.18 (2.78) | −0.00 (2.17) | .16 | .90 |

| ROM, ankle dorsiflexion, degrees | −0.71 (1.35) | −1.02 (1.23) | −1.02 (1.32) | −0.67 (1.33) | .70 | .05 |

| ROM, ankle plantarflexion, degrees | −0.46 (2.33) | 0.19 (2.43) | 0.21 (2.04) | 0.02 (1.93) | .16 | .45 |

| Functionc | ||||||

| Walking efficiency | −2.62 (1.90) | −2.07 (1.86) | −1.99 (1.82) | −1.84 (2.19) | .03 | .82 |

| Dexterity | −1.47 (1.31) | −0.98 (1.28) | −0.61 (1.21) | −0.91 (1.89) | .05 | 1.00 |

| Proxy report | ||||||

| PedsQL physical function | −1.76 (1.33) | −0.76 (1.16) | −0.48 (1.05) | 0.02 (0.99) | <.001 | <.001 |

| PODCI upper extremity | −0.41 (1.07) | −0.47 (1.12) | −0.14 (1.12) | 0.24 (0.79) | <.001 | <.001 |

| PODCI transfer | −1.72 (2.56) | −0.53 (1.44) | −0.25 (1.00) | 0.13 (0.34) | <.001 | <.001 |

| PODCI sports | −2.03 (1.84) | −0.97 (1.40) | −0.85 (1.36) | 0.02 (0.80) | <.001 | <.001 |

Sample sizes refer to number of subjects with at least 1 measure at the time-point. Number of completed evaluations at each time-point are shown in Supplementary Table 4 (available online). PedsQL = Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales; PODCI = Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument; ROM = range of motion; T1 = end consolidation; T2 = maintenance month 1; T3 = maintenance month 18; T4 = 12 months posttherapy.

All P values are derived from mixed linear models.

Walking efficiency is measured by Six-Minute Walk test and dexterity by score on Purdue Pegboard.

Impairment by Treatment Arm

When comparing prevalence of impairment by PT/OT evaluation between VCR/DEX4 and VCR/DEX12 at T3 and T4, controlling for T2 (near randomization) prevalence, most outcomes did not statistically significantly differ between groups (Table 3; Supplementary Table 5, available online). At T4, there was more frequent dorsiflexion ROM impairment (46.7% vs 14.7%; P = .008) and less frequent handgrip strength impairment (22.2% vs 37.1%; P = .03) in VCR/DEX4 than VCR/DEX12, but no difference in other motor, sensory, or functional outcomes between groups when controlling for T2 (Table 3). Comparison of impairment in VCR/DEX4 vs VCR/DEX12 at T3 is shown in Supplementary Table 5 (available online). In linear mixed effect models examining z scores at T3 and T4 adjusting for T2 (near randomization) function, higher dorsiflexion ROM z scores for VCR/DEX12 (vs VCR/DEX4) at T4 (P = .004) was the only statistically significant finding (Table 3; Supplementary Table 5, available online).

Table 3.

Mean z scores and prevalence of impairment for sensory, motor, functional, and proxy-reported outcomes in participants randomly assigned to every 4-week vincristine and dexamethasone (VCR/DEX4) during maintenance compared with every 12-week vincristine and dexamethasone (VCR/DEX12) at T4 (12 months posttherapy)

| Outcome | VCR/DEX4 | VCR/DEX12 | P, % impaireda | P, z scorea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 33) |

(n = 40) |

|||||

| Mean z score (SD) | Impaired | z score (SD) | Impaired | |||

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |||||

| Sensory | ||||||

| Vibration index finger | −0.55 (4.53) | 2 (7.1) | 0.02 (1.57) | 4 (10.8) | .68 | .23 |

| Vibration great toe | −0.20 (3.37) | 4 (14.3) | −1.78 (8.79) | 7 (19.4) | .53 | .36 |

| Light touch index finger | —c | 1 (3.2) | —c | 0 (0.0) | —d | —c |

| Light touch great toe | —c | 3 (9.7) | —c | 1 (2.9) | —d | —c |

| Any sensory impairment | —c | 8 (25.8) | —c | 9 (24.3) | .93 | —c |

| Motor | ||||||

| Strength, handgrip, kg | −0.43 (1.53) | 6 (22.2) | −0.85 (1.03) | 13 (37.1) | .03 | .06 |

| Strength, ankle dorsiflexion, kg | −0.25 (2.38) | 7 (28.0) | 0.18 (2.01) | 6 (18.2) | .81 | .95 |

| ROM ankle dorsiflexion | −1.20 (1.25) | 14 (46.7) | −0.21 (1.24) | 5 (14.7) | .008 | .004 |

| ROM ankle plantarflexion | −0.22 (1.96) | 10 (32.3) | 0.22 (1.91) | 9 (24.3) | .34 | .10 |

| Any motor impairment | —c | 21 (67.7) | —c | 21 (56.8) | .61 | —c |

| Any motor or sensory impairment | —c | 23 (74.2) | —c | 23 (62.2) | .53 | —c |

| Functionb | ||||||

| Walking efficiency | −1.44 (1.73) | 19 (61.3) | −2.18 (2.48) | 27 (73.0) | .25 | .12 |

| Dexterity | −0.71 (2.10) | 10 (35.7) | −1.06 (1.73) | 11 (31.4) | .83 | .26 |

| Any functional | —c | 25 (80.7) | 28 (75.7) | .63 | —c | |

| Proxy report | ||||||

| PedsQL physical function | 0.11 (0.88) | 1 (3.3) | −0.06 (1.08) | 3 (8.8) | —d | .56 |

| PODCI upper extremity | 0.17 (0.97) | 2 (6.3) | 0.30 (0.60) | 2 (5.4) | —d | .55 |

| PODCI transfer | 0.06 (0.44) | 1 (3.2) | 0.19 (0.22) | 0 (0.0) | —d | .05 |

| PODCI sports | −0.10 (0.90) | 5 (16.1) | 0.11 (0.71) | 3 (8.1) | .04 | .049 |

| Any proxy report | —c | 5 (15.6) | —c | 7 (17.5) | .40 | —c |

| Any impairment | —c | 28 (84.9) | —c | 37 (92.5) | .23 | —c |

P value refers to the comparison of T4 odds of impairment (generalized estimating equation approach for binary repeated measures) and mean z scores (linear mixed models) between randomly assigned groups, controlling for baseline (T2). ROM = range of motion; PedsQL = Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales; PODCI = Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument.

Walking efficiency is measured by Six-Minute Walk test and dexterity by score on Purdue Pegboard.

Z scores not applicable for dichotomous variables.

Unable to model because of low case counts.

Because of the higher prevalence of females than males in VCR/DEX4 compared with VCR/DEX12, a follow-up analysis using mixed linear effects models measured whether group by time effects differed by sex. Only dorsiflexion ROM and ankle strength had group by time effects that differed by sex. Dorsiflexion ROM had a group difference only in males (P = .003) and ankle strength only in females (P = .001), with VCR/DEX12 performing better for both outcomes.

Proxy-Reported Outcomes

Proxy-reported impairment was prevalent at T1 (44.9% PedsQL, 21.4% PODCI upper extremity, 43.5% PODCI transfer, 58.8% PODCI sports; Figure 2). Impairment was most severe at T1 for most proxy-reported outcomes and improved by T4 (vs T1; all P < .001; Table 2). Proxy-reported outcomes did not differ between VCR/DEX4 and VCR/DEX12 at T3 or T4 when controlling for T2 impairment, except for more frequent and severe impairment in PODCI sports in VCR/DEX4 vs VCR/DEX12 at T4 (Table 3; Supplementary Table 5, available online).

Discussion

This was the first study to use PT/OT evaluations to assess CIPN prospectively and longitudinally in children with ALL enrolled on a multicenter therapeutic trial during therapy and posttherapy. We demonstrated 81.8% of childhood ALL patients had peripheral motor or sensory impairment within 2 months of therapy, after 5 doses of vincristine, acknowledging that physical functioning could be affected by proximal myopathy from the 28-day steroid course and overall deconditioning from acute illness and intensive induction. Motor or sensory impairments persisted on examination up to 12 months posttherapy in 67.6% of survivors, even though proxy-reported impairments resolved. Finally, despite reduction in vincristine and dexamethasone frequency during maintenance, there was no statistically significant difference in most motor, sensory, functional, or proxy-reported outcomes between treatment groups posttherapy.

A key finding is CIPN develops within 2 months of therapy and does not resolve by 12 months posttherapy. The high early prevalence of CIPN is consistent with a study of 128 children treated for ALL on varied therapeutic regimens, where 78% developed CIPN by the Total Neuropathy Score–Pediatric Vincristine tool peaking within 2-4 months (13). We further demonstrated CIPN persists at least 12 months after cessation of vincristine in 67.6% of participants. This contrasts a study of 26 children with ALL where prevalence of CIPN by pediatric-modified total neuropathy score (ped-m TNS) decreased from 84.6% during therapy to 11.5% posttherapy (17). Our findings may differ because we included quantitative functional outcomes that add additional information to the mostly symptom-based impairments evaluated by ped-m TNS. Further, although ped-m TNS is validated in children receiving therapy, it is not validated posttherapy and may miss subtle CIPN findings in survivors (39). We do not believe attrition from T1 to T4 impacted the estimated posttherapy prevalence because there was no difference in T1 impairment between participants who dropped out vs completed T4. Our estimated CIPN prevalence may underestimate the general ALL survivor prevalence, as participants were from sites with PTs/OTs and may have been more likely to receive these services (23,40). It is also possible that CIPN improved beyond 12 months posttherapy, which we were not able to assess. A previous evaluation of long-term childhood cancer survivors found the cumulative incidence of CIPN increased as many as 20 years postdiagnosis but was limited by retrospective analysis and self-report (41). A recent analysis of at least 5-year ALL survivors found that 16% had CIPN by clinical evaluation, suggesting it persists beyond 12 months (42). This was a cross-sectional analysis that assessed only grade 2 or higher CIPN, making it difficult to interpret whether the lower prevalence of CIPN compared with our study reflects continued improvement posttherapy. Future studies should focus on prospectively and longitudinally evaluating CIPN using clinical evaluations in ALL survivors more than 12 months posttherapy to better understand its long-term natural course. Nevertheless, the finding that CIPN develops early and persists at least 12 months posttherapy has important clinical implications because it is amenable to early intervention that may prevent progression and improve symptoms (23,40).

Another important finding is that functional outcomes including walking efficiency and dexterity remained impaired posttherapy, despite proxy-reported improvement. We found 33.3% of participants had impaired dexterity, and 67.7% had impaired walking efficiency posttherapy, consistent with reports that more than half of long-term ALL survivors have impaired walking efficiency (16). Interestingly, proxy-reported outcomes including QOL and function normalized. Despite this discrepancy, we believe the PT/OT–identified impairments are clinically significant as they represent function below the 10th percentile of the normal population. Impaired dexterity and walking efficiency can impact health and QOL. ALL survivors are at risk for impaired handwriting, which can be influenced by dexterity (6). Impaired walking efficiency can interfere with exercise and may increase the risk for obesity among ALL survivors already at risk for this late effect (7). The discordance between PT/OT evaluations and proxy report may be due to adaptation to changes in function or reduction in expectations, resulting in less perceived impairment. Additionally, deficits in walking efficiency and dexterity may not influence domains assessed by PedsQL and PODCI, or impairment may not be perceived by parents and therefore missed by proxy report (35,36). These findings suggest continued clinical evaluation may be warranted over proxy-reported measures in survivors.

This study was the first to assess CIPN using PT/OT evaluations in a pediatric multicenter therapeutic trial. Aside from dorsiflexion ROM, handgrip strength, and PODCI sports participation, other outcomes did not differ between VCR/DEX4 and VCR/DEX12 posttherapy. Further, although outcomes largely included peripheral motor and sensory impairment from CIPN, functional outcomes that can be impacted by steroid-associated myopathy, including walking efficiency and other proxy-reported outcomes, did not differ despite reduction in steroid pulses (43,44). Similar to our findings, observational studies found no dose relationship between vincristine and CIPN in children with ALL (11,17), but we demonstrated this in a randomized prospective study. One possible explanation for similar findings between groups is that CIPN develops early and persists; therefore reduction in vincristine frequency during maintenance may not alter the clinical course (45). In a study assessing variations in CEP72 and their association with CIPN, only 15% of patients with the high-risk TT genotype developed CIPN beyond 6 months of therapy, suggesting most patients are not affected by vincristine modifications late in therapy (45). Future therapeutic studies could consider reduction of vincristine premaintenance as an alternative approach to decreasing CIPN, as this may offer similar survival outcomes (46).

Most outcomes did not differ between treatment groups, however, dorsiflexion ROM varied most statistically significantly between VCR/DEX4 and VCR/DEX12 with increased frequency and severity of impairment in VCR/DEX4 posttherapy. The susceptibility of ankle ROM to higher cumulative doses of vincristine is consistent with previous findings that survivors who received a cumulative vincristine dose of more than 39 mg/m2 were at higher risk for impaired ankle ROM than survivors exposed to 39 mg/m2 or less (16). In our study, scheduled cumulative vincristine doses ranged from 37.5 mg/m2 (VCR/DEX12 females) to 75 mg/m2 (VCR/DEX4 males). Motor nerve fibers that direct movement may be more susceptible to higher cumulative vincristine doses leading to this finding (47). Impaired ankle ROM is clinically meaningful because it is associated with impaired gait and slowed walking in children (32) and a fall risk in adults (48). We also found more frequent and severe impairment in PODCI sports in VCR/DEX4 compared with VCR/DEX12. It is possible that impaired dorsiflexion ROM caused subtle gait changes that contributed to this finding, because gait changes have previously been associated with impairment in the PODCI sports domain (49). As VCR/DEX12 becomes more widely used, better ankle ROM may benefit the long-term health and function of ALL survivors (24). Nevertheless, because other outcomes did not improve despite reduction in vincristine frequency, it remains imperative to evaluate for CIPN in all children treated for ALL during therapy and posttherapy.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of potential limitations. Attrition from T1 to T4 limited sample size. It is possible this limited our ability to detect subtle differences between treatment arms. However, attrition was similar to the overall therapeutic study, and there was no difference in T1 impairment between those who dropped out and completed T4 so we do not believe it impacted longitudinal patterns of CIPN (24). Despite this limitation, this was the first pediatric multisite study to use PT/OT assessment of CIPN in an upfront therapeutic trial and provides novel insight into vincristine toxicity and the natural course of CIPN. There were also individual missing evaluations across time-points among participants who remained in the study. We believe these were because of the length of evaluations, and despite this limitation, the comprehensive evaluation for CIPN provides unique, robust data. There were more males in VCR/DEX12 than VCR/DEX4 despite randomization. In post hoc exploratory analysis, only 2 of 12 outcomes had possible group by time effects that differed by sex. As these were ad hoc analyses in only 2 outcomes with differing sex findings, we do not believe this impacted our overall conclusion that outcomes generally did not differ between treatment groups. Males and females were treated with different durations of maintenance therapy leading to variation in cumulative vincristine exposure in VCR/DEX4 vs VCR/DEX12 and variation in time because of treatment initiation between males and females at T4. We do not believe this impacted results because there were no differences in impairment by sex at T4, but future studies are needed to determine if prevalence of CIPN posttherapy will decrease in males who are treated with 2 years of maintenance (24). Finally, there is a risk for misclassification bias because participants were at risk for steroid myopathy that can cause proximal weakness (43,44). Although motor and sensory evaluations focused on distal deficits specific to CIPN, it is possible that secondary functional outcomes may be affected by myopathy.

CIPN is prevalent among children treated for ALL within 2 months of therapy and persists at least 12 months posttherapy. Reduction in vincristine frequency did not decrease the prevalence of most CIPN outcomes. Screening and interventions aimed at improving CIPN should be initiated early in therapy, and surveillance should continue posttherapy.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to the Children’s Oncology Group (COG), including U10CA180886-06S1 (BIQSFP), U10CA98543 (Chair’s Grant), U10CA98413 (Statistics and Data Center), U10CA180886 (NCTN Network Group Operations Center Grant), U10CA180899 (NCTN Statistics and Data Center), UG1CA189955 (NCORP Grant for Cancer Control Studies); a Community Clinical Oncology Research Program grant U10CA095861 from the National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Prevention to COG; and the St. Baldrick’s Foundation.

Dr Rodwin was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute through the Yale Cancer Prevention and Control Training Program (T32 CA250803 to RLR), as well as the Yale Pediatric Scholar Program (RLR), the William O. Seery Mentored Research Award for Cancer Research, Bank of America, N.A., Trustee (RLR), and the Hyundai Hope on Wheels Young Investigator Award (RLR).

Notes

Role of the funders: Funding sources were not involved in design of the study, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation, or decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Disclosures: SPH is the Jeffrey E. Perelman Distinguished Chair in Pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, receives honoraria from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Servier, is on Jazz Pharmaceuticals advisory board, is a member of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology executive committee, and is an owner of Amgen common stocks. No other authors report any disclosures.

Author contributions: MD, ER, NJW, SPH, MLL, MJH, ALA, KKN, NKL: study concept and study design. MKW, RJS, ALA, NKL contributed to data collection. RLR, JAK, EH, MD, NKL contributed to data curation. RLR, JAK, EH, MD, ALA, KKN, SKL contributed to methodology. RLR, JAK, EH, MD, MKW, ALA, KKN, NKL contributed to formal analysis. RLR, JAK, EH, MD, NKL contributed to verifying underlying data. RLR, JAK, EH, ALA, NKL contributed to writing original draft. RLR, JAK, EH, MD, MKW, CEM, RJS, ER, NJW, SPH, MLL, MJH, ALL, KKN, NKL contributed to writing-review and editing. All authors had access to the data and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Prior presentations: A portion of these data were presented at the 53rd Congress of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology meeting, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Data Availability

De-identified data would be shared upon reasonable request to corresponding author with subsequent approval by the Children’s Oncology Group Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Committee Chair, and a signed data usage agreement. The study protocol is currently available online (24).

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Rozalyn L Rodwin, Department of Pediatrics, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA.

John A Kairalla, Department of Biostatistics, Colleges of Medicine and Public Health & Health Professions, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA.

Emily Hibbitts, Department of Biostatistics, Colleges of Medicine and Public Health & Health Professions, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA.

Meenakshi Devidas, Department of Global Pediatric Medicine, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA.

Moira K Whitley, Department of Pediatrics, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA.

Caroline E Mohrmann, Department of Pediatrics, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis Children’s Hospital, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Reuven J Schore, Division of Oncology, Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC, USA; Cancer Biology Research Program, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC, USA.

Elizabeth Raetz, Department of Pediatrics, NYU Langone Medical Center, New York, NY, USA.

Naomi J Winick, Department of Pediatrics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Stephen P Hunger, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Mignon L Loh, Department of Pediatrics, Benioff Children’s Hospital, and the Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Institute, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Marilyn J Hockenberry, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA; School of Nursing, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA.

Anne L Angiolillo, Division of Oncology, Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC, USA; Cancer Biology Research Program, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC, USA.

Kirsten K Ness, Department of Epidemiology and Cancer Control, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA.

Nina S Kadan-Lottick, Cancer Prevention and Control, Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Washington, DC, USA.

References

- 1. Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A.. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):83-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maloney KW, Devidas M, Wang C, et al. Outcome in children with standard-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of Children’s Oncology Group Trial AALL0331. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(6):602-612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mulrooney DA, Hyun G, Ness KK, et al. The changing burden of long-term health outcomes in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a retrospective analysis of the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(6):e306-e316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bjornard KL, Gilchrist LS, Inaba H, et al. Peripheral neuropathy in children and adolescents treated for cancer. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(10):744-754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Varedi M, Lu L, Howell CR, et al. Peripheral neuropathy, sensory processing, and balance in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2315-2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reinders-Messelink HA, Schoemaker MM, Hofte M, et al. Fine motor and handwriting problems after treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;27(6):551-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rodwin RL, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of neuromuscular dysfunction in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(8):1536-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kandula T, Farrar MA, Cohn RJ, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: clinical, neurophysiological, functional, and patient-reported outcomes. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(8):980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dixon SB, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. Reduced morbidity and mortality in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(29):3418-3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pui CH, Yang JJ, Hunger SP, et al. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: progress through collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(27):2938-2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramchandren S, Leonard M, Mody RJ, et al. Peripheral neuropathy in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2009;14(3):184-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ness KK, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, et al. Limitations on physical performance and daily activities among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(9):639-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lavoie Smith EM, Li L, Chiang C, et al. Patterns and severity of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2015;20(1):37-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tay CG, Lee VWM, Ong LC, Goh KJ, Ariffin H, Fong CY.. Vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(8):e26471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jain P, Gulati S, Seth R, Bakhshi S, Toteja GS, Pandey RM.. Vincristine-induced neuropathy in childhood ALL (acute lymphoblastic leukemia) survivors: prevalence and electrophysiological characteristics. J Child Neurol. 2014;29(7):932-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ness KK, Hudson MM, Pui CH, et al. Neuromuscular impairments in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: associations with physical performance and chemotherapy doses. Cancer. 2012;118(3):828-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gilchrist LS, Tanner LR, Ness KK.. Short-term recovery of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy after treatment for pediatric non-CNS cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(1):180-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rodwin RL, Ross WL, Rotatori J, et al. Newly identified chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in a Childhood Cancer Survivorship Clinic. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;69(3):e29550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gilchrist LS, Marais L, Tanner L.. Comparison of two chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy measurement approaches in children. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(2):359-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hayek S, Dhaduk R, Sapkota Y, et al. Concordance between self-reported symptoms and clinically ascertained peripheral neuropathy among childhood cancer survivors: the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(12):2256-2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith EML, Li L, Hutchinson RJ, et al. Measuring vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Nursing. 2013;36(5):E49-E60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wright GEB, Amstutz U, Drogemoller BI, et al. ; for the Canadian Pharmacogenomics Network for Drug Safety Consortium. Pharmacogenomics of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy implicates pharmacokinetic and inherited neuropathy genes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;105(2):402-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tanner L, Sencer S, Hooke MC.. The Stoplight Program: a proactive physical therapy intervention for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2017;34(5):347-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Angiolillo AL, Schore RJ, Kairalla JA, et al. Excellent outcomes with reduced frequency of vincristine and dexamethasone pulses in standard-risk B-lymphoblastic leukemia: results from Children’s Oncology Group AALL0932. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(13):1437-1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bell-Krotoski JA, Fess EE, Figarola JH, Hiltz D.. Threshold detection and Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments. J Hand Ther. 1995;8(2):155-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blankenburg M, Boekens H, Hechler T, et al. Reference values for quantitative sensory testing in children and adolescents: developmental and gender differences of somatosensory perception. Pain. 2010;149(1):76-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bohannon RW, Wang YC, Bubela D, Gershon RC.. Handgrip strength: a population-based study of norms and age trajectories for 3- to 17-year-olds. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2017;29(2):118-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beenakker EA, van der Hoeven JH, Fock JM, Maurits NM.. Reference values of maximum isometric muscle force obtained in 270 children aged 4-16 years by hand-held dynamometry. Neuromuscul Disord. 2001;11(5):441-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Soucie JM, Wang C, Forsyth A, et al. ; for the Hemophilia Treatment Center Network. Range of motion measurements: reference values and a database for comparison studies. Haemophilia. 2011;17(3):500-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Casey EB, Jellife AM, Le Quesne PM, Millett YL.. Vincristine neuropathy. Clinical and electrophysiological observations. Brain. 1973;96(1):69-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dropcho EJ. Neurotoxicity of cancer chemotherapy. Semin Neurol . 2010;30(3):273-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gilchrist L, Tanner L.. Gait patterns in children with cancer and vincristine neuropathy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2016;28(1):16-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Geiger R, Strasak A, Treml B, et al. Six-Minute Walk Test in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2007;150(4):395-399, 399.e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wilson BC, Iacoviello JM, Wilson JJ, Risucci D.. Purdue Pegboard performance of normal preschool children. J Clin Neuropsychol. 1982;4(1):19-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lerman JA, Sullivan E, Barnes DA, Haynes RJ.. The Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument (PODCI) and functional assessment of patients with unilateral upper extremity deficiencies. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):405-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K, Dickinson P.. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer. 2002;94(7):2090-2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zheng DJ, Lu X, Schore RJ, et al. Longitudinal analysis of quality-of-life outcomes in children during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group AALL0932 trial. Cancer. 2018;124(3):571-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liang K-Y, Zeger SL.. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13-22. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gilchrist LS, Tanner L.. The pediatric-modified total neuropathy score: a reliable and valid measure of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in children with non-CNS cancers. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):847-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wright MJ, Hanna SE, Halton JM, Barr RD.. Maintenance of ankle range of motion in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2003;15(3):146-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rodwin RL, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of neuromuscular dysfunction in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(8):1536-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goodenough CG, Diouf B, Yang W, et al. Association between CEP72 genotype and persistent neuropathy in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2022;36(4):1160-1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Muratt MD, Perondi MB, Greve JM, Roschel H, Pinto AL, Gualano B.. Strength capacity in young patients who are receiving maintenance therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a case-control study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66(7):1277-1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guis S, Mattéi JP, Lioté F.. Drug-induced and toxic myopathies. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17(6):877-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Diouf B, Crews KR, Lew G, et al. Association of an inherited genetic variant with vincristine-related peripheral neuropathy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2015;313(8):815-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Attarbaschi A, Mann G, Zimmermann M, et al. ; on behalf of the AIEOP-BFM (Associazione Italiana di Ematologia e Oncologia Pediatrica & Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster) Study Group. Randomized post-induction and delayed intensification therapy in high-risk pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: long-term results of the international AIEOP-BFM ALL 2000 trial. Leukemia. 2020;34(6):1694-1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kavčič M, Zečkanović A, Jazbec J, Debeljak M.. Association of CEP72 rs924607 TT genotype with vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy measured by motor nerve conduction studies. Klin Padiatr. 2020;232(6):331-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Menz HB, Morris ME, Lord SR.. Foot and ankle risk factors for falls in older people: a prospective study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(8):866-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. O’Sullivan R, French HP, Van Rossom S, Jonkers I, Horgan F.. The association between gait analysis measures associated with crouch gait, functional health status and daily activity levels in cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2021;14(2):227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

De-identified data would be shared upon reasonable request to corresponding author with subsequent approval by the Children’s Oncology Group Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Committee Chair, and a signed data usage agreement. The study protocol is currently available online (24).