Abstract

Histiocytoses constitute a heterogeneous group of rare disorders, characterised by infiltration of almost any organ by myeloid cells with diverse macrophage or dendritic cell phenotypes. Histiocytoses can start at any age. Diagnosis is based on histology in combination with appropriate clinical and radiological findings. The low incidence and broad spectrum of clinical manifestations often leads to diagnostic delay, especially for adults. In most cases, biopsy specimens infiltrated by histiocytes have somatic mutations in genes activating the MAP kinase cell-signalling pathway. These mutations might also be present in blood cells and haematopoietic progenitors of patients with multisystem disease. A comprehensive range of investigations and molecular typing are essential to accurately predict prognosis, which can vary from spontaneous resolution to life-threatening disseminated disease. Targeted therapies with BRAF or MEK inhibitors have revolutionised salvage treatment. However, the type and duration of treatment are still debated, and the prevention of neurological sequelae remains a crucial issue.

Introduction

Histiocytoses are a clinically heterogeneous group of rare disorders (appendix p 2) with onset at any age, which remain challenging to diagnose and treat. However, recent discoveries of oncogenic mutations in the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cell-signalling pathway have revolutionised clinical management. In the past, detection of phenotypic or ultrastructural markers specific to Langerhans cells (eg, CD1a, CD207, and Birbeck granules) defined the difference between Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) and non-LCH.1 It is now known that a common molecular cause underlies most LCH and other non-LCH entities, notably Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) and some cases of juvenile xanthogranuloma and Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease (RDD). Indeed, the majority of lesions that occur in histiocytoses harbour mutations in CSF1R, ALK, RET, NTRK, RAS, RAF, MAP2K, or other kinase genes, linking myeloid-specific growth factor receptor-binding to ERK activation.

Histiocytes can infiltrate virtually any tissue or organ, with a predilection for skin, bone, lung, lymph nodes, CNS, and heart (appendix p 12).2 Symptoms can reflect tumour mass and compression of adjacent organs, inflammation, tissue destruction, or progressive fibrosis, or a combination of these. Chronic inflammation can also cause constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, weight loss, lethargy). Most reviews have focused on one type of histiocytosis (childhood or adult LCH, ECD, or RDD);3–6 however, disease overlap is not infrequent. Indeed, patients with ECD can also have LCH lesions, and both entities can be associated with RDD-like lesions.7–9 Furthermore, some presentations are not reflected in the current WHO classification.10 Finally, the histiocyte population within a single lesion is heterogeneous,11 and the histology and phenotype of some types of histiocytosis (eg, ECD and juvenile xanthogranuloma) can be indistinguishable.

Thus, the Histiocyte Society endorsed a revised classification in 2016,12 arranging the different histiocytoses into five main groups (L, R, C, M, and H) according to clinical, histological, and molecular characteristics. Since its publication, patients in groups R, C, and M have been found to share molecular alterations;13–16 molecular alterations were previously considered a hallmark of group L. The different histiocytosis types can also share particular clinical or radiological features (eg, neuro-degeneration in LCH and ECD). Thus, it is tempting to hypothesise that some historical histiocytosis types might only correspond to clusters of characteristics of a unique-but-heterogeneous disease. Therefore, an update of our current knowledge on all of these entities within a single review is warranted, while conserving the historical classification for better understanding and easier use in clinical practice.

Pathophysiology

MAP kinase pathway mutations

The presence of the BRAF mutation encoding the V600E (Val600Glu) variant in LCH was first reported in 2010.17 BRAF was already a known oncogenic driver in several human neoplasms.18 That finding from 2010 revolutionised understanding of histiocytoses and opened the way for targeted therapies. BRAF is a protein in the MAP kinase cell-signalling pathway, a cascade of successively activated cytoplasmic proteins. In normal cells, activation of a membrane tyrosine kinase receptor by its specific ligand induces, through the MAP kinase pathway, the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of ERK, which acts as a transcription factor for genes that induce cell proliferation and survival. The BRAFV600E mutation encodes a cytoplasmic mutant protein with constitutive activation, which confers independence from upstream activation by one of the RAS proteins. Although the clonality of some cases of LCH had previously been reported,19 the neoplastic nature of the disease became unequivocal when this somatic oncogene mutation was detected.

Recurrent somatic BRAFV600E mutations in biopsy specimens of tissue infiltrated by LCH have been confirmed by several researchers, regardless of patient age or disease site.20–23 The mutation was also identified in samples from patients with ECD21 or mixed histiocytosis.7 BRAFV600E was detected at a frequency of 50–60% in the largest series of patients with LCH or ECD.11,23,24 Its presence was associated with worse prognoses for a series of 315 children with LCH given standard therapy.25 LCH and ECD biopsy samples lacking the BRAFV600E mutation usually harbour other gene mutations in the MAP kinase signalling pathway. Most often, only one mutation in the MAP kinase pathway is present, but it might be associated with other gene mutations,26–28 some of which can activate other signalling pathways.13,24,27

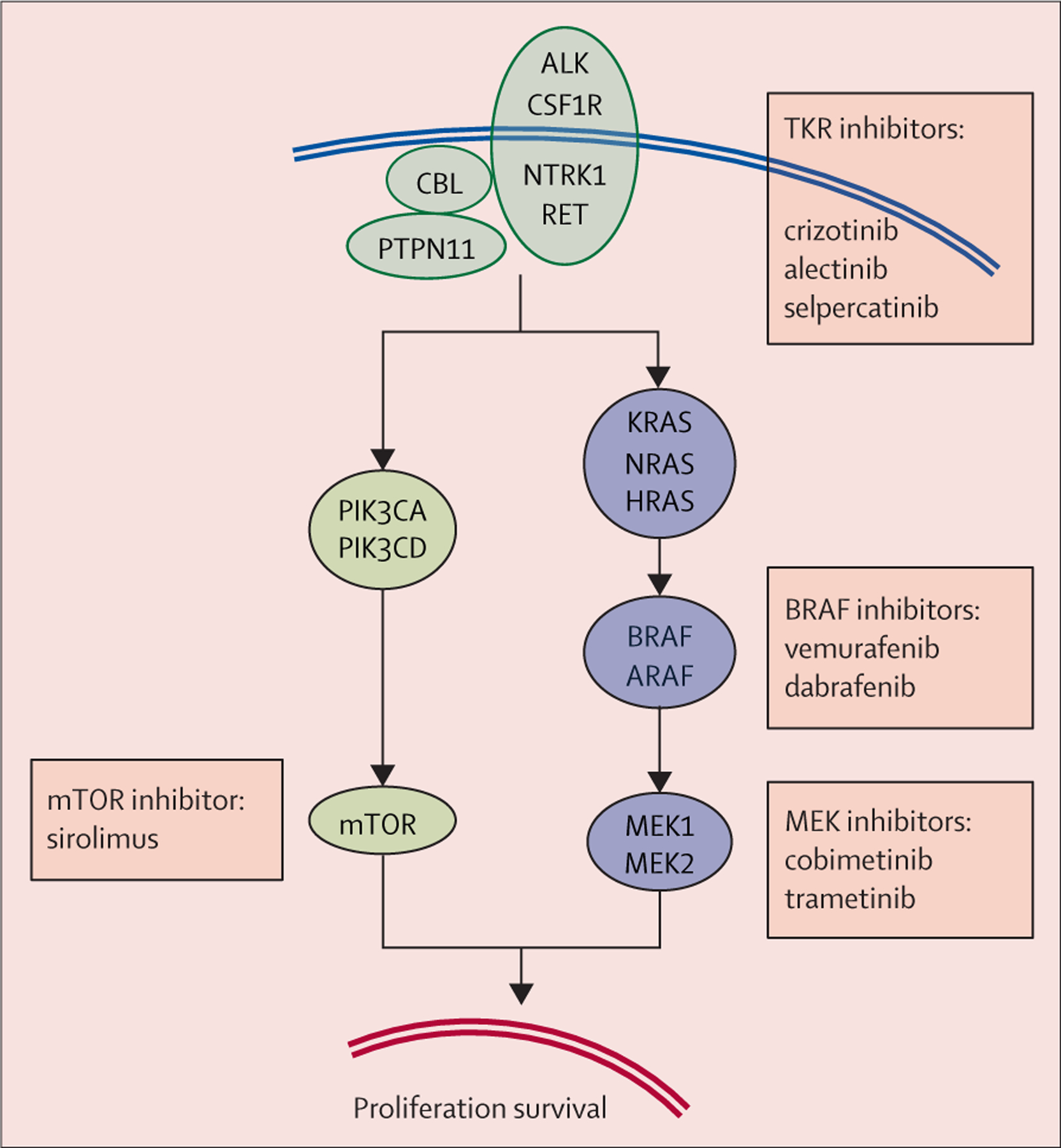

Pertinently, BRAF mutations in histiocytoses can occur at sites other than the predominant V600 residue,29,30 or in another RAF kinase (eg, ARAF).31 Moreover, some histiocytoses are driven by mutations in the MAP kinase pathway that affect MAP2K1, a gene which encodes the MEK1 kinase just downstream from BRAF.26,32 Other MAP kinase-signalling components upstream from BRAF (including NRAS, KRAS, HRAS, and PTPN11) can also be involved (figure 1). Notably, the latter group also includes activating mutations in tyrosine kinase receptors (eg, CSF1R, ALK, NTRK1, and RET).13 Overall, this new molecular profile of macrophage and dendritic cell neoplasm involving CSF1 receptor signalling parallels the spectrum of myeloproliferative disorders caused by somatic activation of genes in the thrombopoietin signalling pathway.

Figure 1:

Proteins of the MAP kinase cell-signalling pathway involved by activating mutations, and inhibitors already reported to benefit patients with histiocytoses

Most mutations in histiocytoses are point mutations or small deletions or insertions, but some gene fusions result in production of chimeric proteins.2,27–29,33 Altogether, more than 90% of cases of LCH and ECD share mutations activating the MAP kinase pathway. Notably, the MAP kinase pathway is strongly activated (attested by ERK phosphorylation and nuclear translocation) in patients with LCH without identified mutations.26 Various proportions of cases of other histiocytoses,22,27 including the R group histiocytoses,14,34 also have mutations in the MAP kinase pathway. However, the pathogenesis of RDD is probably not uniform across its phenotypic spectrum.3 In a study of 55 cases of juvenile xanthogranuloma, 40 (73%) had a mutation in the MAP kinase pathway.13 Furthermore, in a series of 21 cases of malignant histiocytosis, all had mutations activating the MAP kinase pathway.15

Although ultradeep targeted sequencing has shown high frequencies of microclonal areas within normal epithelium,35 detection, by any standard method, of somatic clonal mutations that activate oncogenes strongly supports the idea that most histiocytoses—even those not classified as malignant—result from neoplastic transformation. Pertinently, forced BrafV600E expression in mouse myeloid precursors induces histiocyte accumulation reminiscent of human histiocytosis.23,36 Finally, the remarkable clinical effects of specific inhibitors and the frequent relapses after stopping treatment are evidence of histiocyte dependence on the activated MAP kinase pathway (an example of oncogene addiction).37–41

Histiocyte progenitor involvement

Macrophages and dendritic cells, including Langerhans cells, can be derived in vitro by differentiation of CD34+ bone marrow cells or blood monocytes.42,43 According to data from mice, in-vivo macrophage populations have diverse origins. Some macrophages, notably microglia and Langerhans cells, are thought to be self-renewing and derived from early yolk sac progenitors, whereas other macrophage and dendritic cell populations are continually replenished by precursors derived from bone marrow.44–46 Human Langerhans cells can also derive from transplanted bone marrow progenitors.47,48 In 2014, Berres and colleagues described a series of children with high-risk, BRAF-mutated LCH, who were found to have BRAF mutation in normal blood monocytes or CD34+ bone marrow cells.23 This finding suggested that histiocyte accumulation in some patients might result from an altered bone marrow progenitor able to differentiate, migrate through blood as a monocyte, and infiltrate peripheral tissues.

Cell heterogeneity within histiocytosis biopsy specimens

The first classification of histiocytoses was based on the presence or absence of Langerhans cell markers.1 Langerhans cells are immature dendritic cells in Malpighian epithelia. Non-Langerhans cell histiocytes are also currently thought to be of macrophage or dendritic cell lineages. In routine diagnostic practice, only a few markers are required to differentiate between different histiocytoses. Co-expression of CD1a and CD207 characterises Langerhans cells. CD68 and CD163 are the macrophage or dendritic cell markers most frequently used to confirm the cells are mononucleated or multinucleated histiocytes.

Analysis of some patients’ biopsy samples has shown that histiocytosis neoplastic cells can be heterogeneous. Indeed, some patients can have overlap histiocytoses (ie, a combination of two or more of LCH, ECD, and RDD) with the same mutation, suggesting a common origin.7–9 Some patients with malignant histiocytoses have different phenotypes in different biopsy specimens.49 Even within the same LCH biopsy specimen, histiocytes can express phenotypic variation,50 and cells expressing BRAFV600E might lack CD207 expression.51

Neoplastic cell heterogeneity within an LCH biopsy sample was confirmed in a 2019 study by high-throughput single-cell analysis. More than 19 000 single-cell transcriptomes from seven LCH biopsy samples revealed 14 neoplastic cell clusters.11 Combining those findings with epigenetic and phenotypic results suggested that those clusters ranged from poorly to highly differentiated cells. More single-cell analyses of different types of histiocytosis are still required. However, it will probably not be possible to identify one type of histiocytosis with a single normal macrophage or dendritic cell counterpart at a definite stage of differentiation.

Childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Epidemiology

The annual incidence of LCH is five to nine cases per 1 000 000 people for children younger than 15 years.52 Most cases are sporadic, but variant SMAD6 has been associated with susceptibility to LCH.53

Clinical presentation

Presenting features of LCH are extremely variable. The most frequent are bone pain or fracture, skin papules, lymphadenopathy, palpable tumour, polyuria and polydipsia related to diabetes insipidus, and exophthalmia (table 1).

Table 1:

Clinical features, investigations, and treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Erdheim-Chester disease, and Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease

| Most frequent revealing clinical features | Initial investigations* when diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy | Most frequent first-line systemic therapies for multiorgan or disseminated forms | Most frequent systemic second-line and salvage therapies† | Reference guidelines | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Bone pain or fracture; vertebra plana‡; skin papules; lymphadenomegaly; palpable tumour; diabetes insipidus‡; exophthalmos‡; deafness or chronic otorrhoea; systemic symptoms with fever, hepatosplenomegaly, or haematological cytopenia (risk organs); pneumothorax | For all patients: blood tests (full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or CRP, albumin, renal function tests, liver function tests, coagulation tests); chest and skeletal radiographs According to initial investigations: CT scan or MRI focused on involved area; brain MRI when diabetes insipidus or any sign of CNS involvement or visual or hearing dysfunction; chest high-resolution CT scan when signs of lung involvement |

Vinblastine combined with corticosteroids | Should be decided according to initial extension and risk organ involvement status, as assessed by a trained team. With risk organ involvement: BRAF or MEK inhibitors§ Without risk organ involvement: monotherapy or combined chemotherapies with cladribine, and, in less documented approaches, cytarabine or clofarabine | 4, 21 |

| Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Bone pain or fracture; skin papules; lymphadenopathy; palpable tumour; diabetes insipidus‡; exophthalmos‡; repeated dental loss; pneumothorax; dyspnoea, dry cough | 18F-FDG-PET (full body); chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT scan; brain MRI; blood tests (full blood count, CRP, albumin, renal function tests, liver function tests) | Cytarabine, alone or combined with methotrexate; vinblastine combined with corticosteroids; cladribine | BRAF or MEK inhibitors | 4, 36 |

| Erdheim-Chester disease | Lower limb pain; general symptoms (fatigue, weight loss, fever); xanthelasma; diabetes insipidus‡; exophthalmos‡; dyspnoea, dry cough; signs of cardiac involvement (eg, tamponade); signs of CNS involvement (degenerative or tumoural) | 18F-FDG-PET (full body); chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT scan; brain MRI; cardiac MRI; blood tests (full blood count, CRP, albumin, renal function tests, liver function tests) | Interferon alfa-2a or pegylated interferon alfa-2a; other potential options are anakinra, infliximab, or sirolimus plus corticosteroids; BRAF or MEK inhibitors for life-threatening cases (eg, CNS or heart involvement) | BRAF or MEK inhibitors | 5 |

| Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease | Lymphadenopathy; skin nodules; nasal obstruction, epistaxis, nasal dorsum deformity; dyspnoea, dry cough; signs of CNS or nerve root involvement; testicular enlargement | Children: chest x-ray with neck and abdominal ultrasound scans Adults: neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT scan; 18F-FDG-PET is recommended by some experts All patients: brain MRI when signs of orbital or CNS involvement; blood tests (full blood count, CRP, albumin, renal function tests, liver function tests) |

Corticosteroids; sirolimus; methotrexate; azathioprine | Several drugs or combined chemotherapies or MEK inhibitors reported to be active in case reports or small case series | 3 |

18F-FDG-PET=18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET. CRP=C-reactive protein.

Aimed to determine the extent of the disease; thus, each clinical feature drives specific investigation of the potentially involved organ(s), including for any signs of endocrine dysfunction or autoimmunity.

See more details and references in appendix pp 3–8.

Features which are suggestive of the disease.

BRAF inhibitors: vemurafenib, dabrafenib, encorafenib. MEK inhibitors: cobimetinib, trametinib, binimetinib, selumetinib.

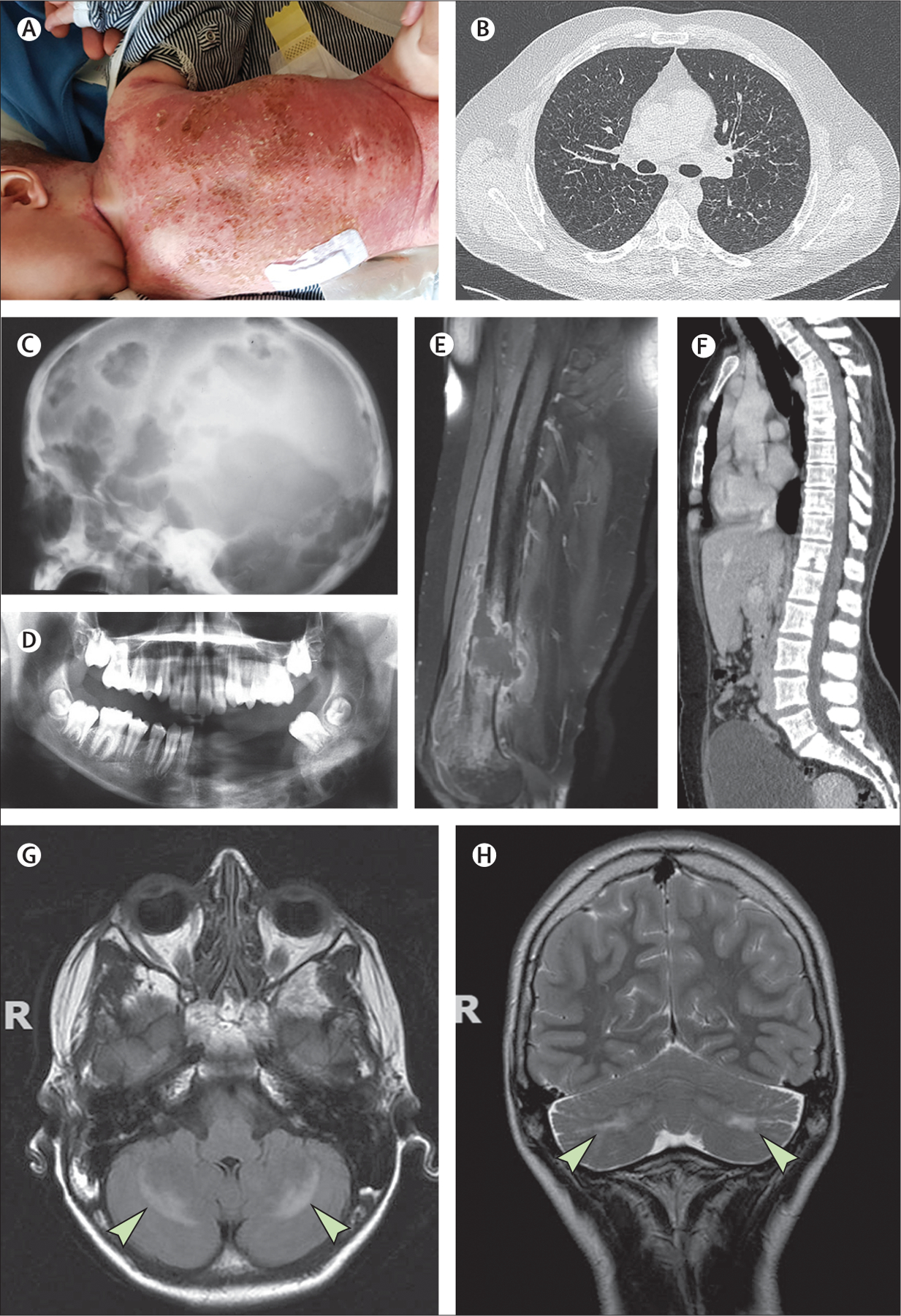

Skin lesions are usually multiple (figure 2A) and polymorphic: reddish-brownish crusted papules, petechiae, vesicles, pustules, or painful ulcerations in skinfolds. Multiple LCH papulovesicular lesions, possibly present at birth, can represent self-healing Hashimoto-Pritzker disease or, more seriously, a component of aggressive multisystemic Letterer-Siwe disease.12 By contrast, Langerhans cell histiocytoma, a rare form of LCH usually detected at birth, consists of one to three cutaneous nodules.50

Figure 2: Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

(A) Young child with disseminated Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) skin lesions. (B) Chest CT scan showing multiple cysts. (C) X-rays showing LCH involvement of the skull. (D) X-rays showing LCH involvement of the mandible, as revealed by so-called floating teeth. (E) MRI showing a femoral lesion revealed by a fracture. (F) CT scan showing the spinal column. (G, H) MRI showing degenerative neuro-LCH on axial T2 spin echo-weighted images, which reveal symmetrical hyperintensities within the cerebellar corpus medullare (arrows).

Bone lesions are frequent. They can be asymptomatic or can manifest in the form of swelling, chronic pain, or, more rarely, fracture. Lytic bone lesions, which can be solitary (eosinophilic granuloma) or multiple, are suggestive of childhood LCH (figure 2C–E). More than half of these lesions involve flat bones (eg, skull, ribs, or pelvis).52 Vertebral body fractures (predominantly in the thoracic spine) can result in vertebra plana (figure 2F). Bone lesions can extend into adjacent soft tissues, including the dura.

A third of patients with LCH have lymphadenopathy. Splenomegaly is mostly limited to young children with multisystem LCH. Orbital involvement of LCH often causes exophthalmos, which is typically bilateral. Deafness or chronic otorrhoea can be signs of mastoid involvement. Lung involvement is detailed in the section on adult LCH, later in this Seminar.

In young children, massive hepatomegaly is the most frequent manifestation of hepatic involvement in the context of systemic Letterer–Siwe disease. Bile duct infiltration causing sclerosing cholangitis is another manifestation of LCH that is rare but characteristic of the disease. Diffuse gastrointestinal tract infiltration in children can result in malabsorption and diarrhoea.54 Posterior pituitary involvement, affecting 15% of children with LCH, can cause diabetes insipidus; anterior pituitary hormones can also be deficient.

Haematological involvement of LCH frequently causes hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or macrophage-activation syndrome (or a combination of these).

Diagnosis and initial investigations

Diagnosis of LCH is based on clinical, radiological, and histological findings. Clinical examination should include, for example, general appearance, skin lesions, and palpation of the lymph nodes, spleen, and liver. Blood tests and imaging are also important, and the choice of tests depends on age and symptoms (table 1); these investigations aim to establish the extent of the disease.55 For histology, a sample can be obtained by biopsy or surgical excision; histology is characterised by infiltration of tissues by CD1a+ CD207+ histiocytes. Once diagnosed, childhood LCH can be classified as single system (with only one affected organ) or multisystem (when two or more organs are involved); LCH with pulmonary involvement is classified separately. Haematopoietic dysfunction or involvement of the liver, spleen, or CNS are associated with poorer prognoses (the haematopoietic system, liver, and spleen are known as risk organs). Children with diabetes insipidus or neurological symptoms should have MRI of the brain.

Treatments

Isolated LCH in bone or lymph nodes usually requires no specific treatment after diagnosis. Surgery can sometimes help to prevent complications (eg, bone fracture, brain or spinal cord compression). Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors can have analgesic effects on bone lesions.56

For childhood LCH requiring systemic therapy, first-line treatment is a combination of vinblastine and corticosteroids. The combination of cladribine (also known as 2'-chlorodeoxyadenosine or 2CDA) with cytarabine is an effective second-line therapy for children with LCH with risk organ involvement.55,57 Several salvage therapies have been used (appendix pp 3–5); these salvage therapies can have high acute toxicity compared with targeted therapy.37 Thus, for selected patients at high risk, many expert centres are prescribing the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib for patients carrying BRAFV600E and a MEK inhibitor for patients not carrying BRAFV600E. Children with resistant LCH without risk organ involvement might benefit from cladribine monotherapy.58 In a French prospective cohort study of 44 children with LCH (without risk organ involvement) resistant to first-line therapy, 31 (70·5%) did not experience progression of disease while taking cladribine monotherapy, and only two (6·5%) of these 31 patients without progression relapsed after stopping it.59

Prognosis

The first-line treatment regimen achieves a response at 6 weeks in 65% of children with risk organ involvement, and 86% of children without risk organ involvement.60 Responses to treatment are evaluated with the Disease Activity Score;61 not responding to treatment indicates a poor prognosis. Targeted therapy is likely to produce substantial clinical responses with limited short-term toxicity in most patients. Although vemurafenib is active in children with BRAFV600E mutations,37,38 its long-term toxicity is unknown.

In a prospective cohort study of 1478 children treated for LCH, among the 995 children enrolled after 1998, 5-year and 10-year survival rates were both 98·7%.62 Among all 1478 patients, 316 (21·4%) developed at least one permanent sequela of LCH, including endocrine anomalies (223 [15·1%]), cholangitis or liver cirrhosis (40 [2·7%]), severe neurological defects (87 [5·9%]), respiratory insufficiency (20 [1·4%]), or deafness (29 [2·0%]). The risk of CNS degenerative lesions in a large cohort of 1897 children with LCH was estimated at 4·1%.63 BRAFV600E mutation, pituitary involvement, skull base lesions, and orbital bone involvement were associated with a risk of CNS degenerative lesions (figure 2G, H), estimated at 33·1% in that series; long-term (≥15 years) follow-up is recommended for patients with these risk factors.

Children with vertebral involvement should undergo orthopaedic evaluation for the risk of scoliosis, a condition that might occur at puberty onset. Liver function blood tests obtained 2–5 years post-diagnosis can reveal sclerosing cholangitis. Long-term morbidity can be quantified using a specific scoring system (the Langerhans cell histiocytosis morbidity score), which correlates with health-related quality of life.64

Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Epidemiology and risk

The annual incidence of LCH for patients older than 18 years is at least 0·07 per 1 000 000; this figure is probably an underestimation arising from the involvement of a wide range of medical specialties.65 In the French Registry of Histiocytoses, patients older than 15 years account for over 25% of LCH entries. Smoking is a major risk factor for pulmonary LCH in young adults.66

Clinical presentation

The pattern of organ involvement in adults is very similar to that in children, but multisystem disease can have a slow evolution, with few symptoms. Repeated dental losses and dental cysts are sometimes revelatory of LCH, and pituitary involvement can precede other symptoms by several years (table 2). Bone lesions can mimic lytic metastases or myeloma. Pulmonary LCH is characterised by micronodules and cysts (figure 2B), predominantly in the upper lobes. Pulmonary LCH can be asymptomatic or associated with dyspnoea, dry cough, or recurrent pneumothorax.67 Liver involvement can cause jaundice due to sclerosing cholangitis, or masses.68

Table 2:

Clinical features of histiocytoses with single organ involvement that are often associated with difficult or late diagnosis of histiocytosis

| Age | Histiocytosis group | |

|---|---|---|

| Recurrent normolipaemic xanthelasma | Adult | ECD |

| Exophthalmos | Any age | L and R |

| Diabetes insipidus | Any age | L |

| Cerebellar syndrome | Any age | L |

| Pachymeningitis | Any age | R |

| Testis involvement | Adult | ECD and R |

| Painful legs | Adult | ECD |

| Vertebra plana | Child more often than adult | LCH |

| Recurrent dental losses with cysts | Any age | LCH |

| Recurrent pneumothorax | Adolescent and young adult | LCH |

| Interstitial lung disease | Adult | ECD and R |

| Obstructive renal failure | Adult | ECD and R |

ECD=Erdheim-Chester disease. LCH=Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Diagnosis and initial investigations

Diagnostic criteria and revealing signs and symptoms are similar to those in children. The investigations for adult LCH depend on the initial clinical features,69 with CNS MRI recommended for all patients. All clinical signs of endocrine dysfunction, including diabetes insipidus and anterior pituitary dysfunction, should be evaluated at diagnosis and during follow-up, even for asymptomatic patients.70,71 High-resolution CT scan is key to diagnosing pulmonary LCH, showing nodules that are small or cavitated (or both), and the progressive evolution of these nodules to cysts. Pulmonary function tests frequently detect reduced diffusion capacity.

Treatments

Some patients presenting with single-system involvement (eg, young adults with asymptomatic lung involvement or those with skin or bone lesions) might require only counselling on lifestyle habits or surveillance. Disseminated skin lesions can regress with topical nitrogen mustard, thalidomide, or phototherapy.69 Bisphosphonates can be prescribed for multiple LCH bone lesions. Several drugs have reported activity as first-line, non-targeted, systemic treatment of LCH in adults (appendix pp 6–8).2 Cytarabine can be used, alone or combined with methotrexate.72 For adults with LCH with risk organ involvement, cladribine can be considered. Efficacy of non-targeted regimens can be assessed after two or three cycles of cladribine or six cycles of vinblastine with corticosteroid.

Targeted vemurafenib therapy also has great efficacy in adults with BRAFV600E mutations.39–41,73 Moreover, MEK inhibitors targeting the MAP kinase pathway downstream from BRAF are also highly active against LCH (even BRAFV600E-negative LCH) with mutations in ARAF, RAF1, NRAS, KRAS, MAP2K1, or MAP2K2, or in the absence of detected mutations.74

Prognosis

Prognosis of LCH in adults is greatly affected by response to treatment and occurrence of relapses. Prognosis can range from an absence of sequelae to severe organ (liver, lung) dysfunction or neurodegeneration.

Erdheim-Chester disease

Epidemiology and clinical presentation

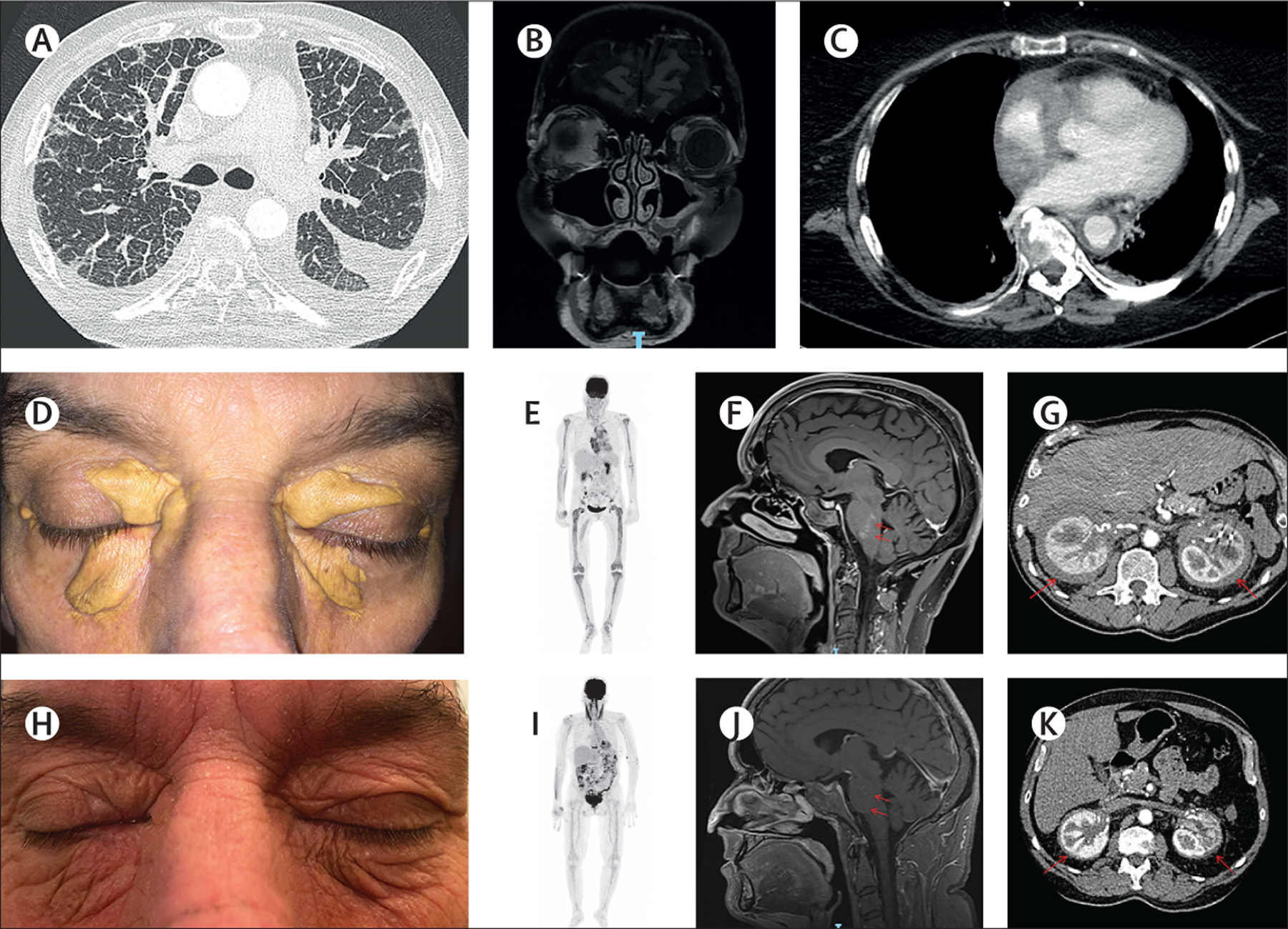

The median age at diagnosis of ECD is 55 years, with a male:female ratio of 2·4:1.75 Symptoms of ECD can include fatigue, weight loss, fever, lower limb pain, polyuria, and polydipsia (table 1). Normolipaemic relapsing xanthelasma (figure 3D) is typical of ECD,76 and can precede other symptoms by several years. As in LCH, orbital infiltration (figure 3B) can cause exophthalmos. Serosal involvement is frequent and can cause effusions; effusions can be abundant and can even result in cardiac tamponade, which might present as emergency with cardiac failure (appendix p 9). Pituitary involvement occurs in 28% of patients with ECD and results in diabetes insipidus.

Figure 3: Erdheim-Chester disease.

(A) Chest CT scan showing lung and pleural involvement of Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD). (B) Coronal, post-gadolinium, T1-weighted MRI showing bilateral ECD infiltration of the orbits (predominantly in the right eye). (C) Chest CT scan showing a so-called coated aorta in a patient with ECD. Xanthelasma in a patient with ECD (D) before treatment and (H) after 3 years of interferon alfa-2a. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET scans showing (E) pretreatment metabolite uptake in the long bones that was (I) decreased after 12 months of cobimetinib. MRI-documented response of (F) a CNS tumour to (J) 12 months of vemurafenib (red arrows). CT scans showing (G) perirenal lesions and (K) their regression after 3 years of cobimetinib (red arrows).

CNS involvement of histiocytosis can be classified into two major subtypes: tumoural (figure 3F and appendix p 13 [image B]) or degenerative (figure 2G, H); a given patient can have both. Vascular infiltration of vertebrobasilar vessels can cause strokes. Neurodegenerative symptoms, often considered a late effect of LCH, can be present early in ECD. Histiocytic lesions restricted to the CNS in some patients77–79 represent a diagnostic challenge (table 2). Most often, tumoural CNS lesions present with acute or rapidly progressive symptoms (eg, headache, increased intracranial pressure syndrome, focal neurological deficits, seizures, or cognitive impairment).1 CNS neurodegeneration often begins as progressive cerebellar dysfunction, sometimes complicated by pyramidal symptoms, pseudobulbar palsy, and cognitive or behavioural disturbances, but with relative sparing of memory.2,80,81 Cognitive impairment affects 17% of patients with ECD.

Autoimmunity has been reported in 41% of patients with ECD, most frequently in the form of thyroiditis, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, pernicious anaemia, or polymyalgia rheumatica.82 Finally, ECD or mixed histiocytosis can arise in adults as part of myeloproliferative neoplasia associated with clonal haematopoiesis.83

Diagnosis and initial investigations

Diagnosis of ECD relies on highly suggestive clinical and radiological manifestations, and histology showing infiltration of tissue by small CD1a– mononucleated histiocytes, sometimes associated with Touton cells. ¹⁸F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT scanning is recommended for all adults with suspected or histologically confirmed ECD (table 1). All patients should undergo chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT scanning to detect lung, vascular, and retroperitoneal infiltration, as well as cardiac and brain MRI. Unlike LCH lesions, bilateral hypermetabolic sclerosing long bone involvement affecting both metaphysis and diaphysis is highly suggestive of ECD. Plain x-rays might not detect those lesions, but bone MRI, scintigraphy, or 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET scanning (figure 3E) is more sensitive.

ECD can also be associated with respiratory symptoms and chest CT scans might reveal ground glass opacities or interlobular septal thickening (figure 3A).84 Pleural, pericardial, or peritoneal thickening can be seen on CT scans or MRI. MRI reveals cardiac involvement in 53% of patients with ECD,75 frequently manifesting as a right atrial mass (in 37% of patients), potentially associated with infiltration of the right intraventricular groove and conduction anomalies.85,86 Moreover, 46% of patients with ECD have periaortic thickening, known as coated aorta (figure 3C).75 Retroperitoneal fibrosis is a hallmark of ECD, revealed by CT as so-called hairy kidneys in 58% of patients (figure 3G).75 That infiltration leads, in 25% of those cases, to hydronephrosis, requiring ureteric stenting.

MRI shows contrast-enhanced tumoural neurohistiocytosis lesions with mass effect and some perilesional oedema. Frequent MRI findings include white matter hyperintense T2 signals, mainly in the posterior fossa (ie, cerebellum and brainstem), and spontaneous hyperintense T1 signals in deep nuclei (ie, dentate nuclei and pallidum); these MRI findings are very similar to those seen in LCH, but are more frequent in ECD than in LCH. When concurrent, these lesions are suggestive of degenerative neurohistiocytosis. Irreversible supratentorial and infratentorial atrophy can develop over time.87 Facial sinus osteosclerosis is suggestive of ECD; it is often asymptomatic and discovered on CT or MRI.88

Treatments

Patients with ECD obtain clinical benefit with interferon alfa-2a or pegylated interferon alfa (figure 3D, H),89 either of which are usually prescribed as first-line treatment. Anakinra and infliximab are also effective in several patients;90,91 their efficacies (including for tumour regression) vary among patients. Several other drugs, including sirolimus92 and tocilizumab,93 have shown activity in some patients. Cladribine is another potential therapeutic option.94

Small molecule oral inhibitors targeting the MAP kinase pathway have revolutionised the management of patients with high-risk histiocytosis. Vemurafenib is active in patients with BRAFV600E mutations (figure 3F, J).39–41,73 MEK inhibitors are also highly effective in patients with mutations activating the MAP kinase pathway (figure 3E, I and G, K).74 A few patients with ALK or RET fusion have benefited from ALK and RET inhibitors in some studies.13,33 Responses to MEK inhibitors have been obtained even in patients with no known mutations, as the effect of MEK inhibitors is not restricted to the histiocytosis type.74,95

Most patients experience reactivation of ECD after treatment discontinuation.96 Targeted therapies can cause toxic effects in patients: short-term toxic effects, such as skin lesions, are frequent (appendix pp 10–11), but long-term toxic effects remain unknown. Therefore, targeted therapies are recommended for life-threatening histiocytoses or high-risk local disease (eg, ophthalmic, cardiac, or neurological involvement), but further investigation is required to establish optimal doses, durations, and combinations of therapies. First-line therapy for mild disease is still debated. Targeted BRAF or MEK inhibitors do not worsen autoimmunity in patients with ECD.82

Therapeutic responses to interferon alfa are usually slower and can be assessed after 6–12 months. PET-CT scanning, usually biannually, is the best way to evaluate the effectiveness of interferon alfa97 and targeted therapies;40,70,96 other imaging modalities are also important to assess organ involvement (head and heart MRI, aortic CT scan). Serum C-reactive protein helps gauge the level of systemic inflammation.

Prognosis

Advanced age at diagnosis and CNS, lung, or retroperitoneal involvement are associated with worse prognosis.75 MRI can detect neurodegenerative changes before clinical symptoms appear.2 Patients with ECD can develop myelodysplasia, myeloproliferative neoplasms,83 or leukaemia.98

Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease

Epidemiology and risk

The prevalence of RDD is five per 1 000 000.3 Mean age at diagnosis is 20·6 years. Most cases are sporadic, although some are inherited. Patients harbouring the SLC29A3 germline mutation, responsible for H syndrome, often have RDD lesions.99 Germline mutation of TNFRSF, coding for FAS and responsible for autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome type 1, confers an increased risk of developing RDD.100

Clinical presentation

Cervical lymph node enlargement is the classic manifestation of RDD (table 1); however, as for other histiocytoses, virtually any organ can be involved (appendix p 12). Nasal obstruction is frequent, and tracheal obstruction can occur rarely. Bone, perirenal, and lung masses have also been described.101–102 Reportedly, 10% of patients with RDD have autoimmune manifestations.103 Furthermore, RDD has sometimes been associated with hyper-IgG4 syndrome.104 Most CNS involvement of RDD consists of meningeal masses that mimic meningiomas, or a more diffuse pattern with dural thickening or pachymeningitis.105

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is obtained from biopsy. Histology shows tissue infiltration by large histiocytes expressing S100, which have abundant emperipolesis and large nucleolated nuclei; these histiocytes are also sometimes seen in vessel lumens.

Treatments

Childhood RDD usually responds to corticosteroids,2 and sometimes to sirolimus. Activity of several first-line non-targeted systemic treatments against adult RDD has been reported.2 Mildly active systemic RDD in adults can be treated first with methotrexate or azathioprine. For RDD with risk organ involvement, cladribine is an option. Finally, patients with organ-threatening or life-threatening disease might benefit from MEK inhibitors.74,101

Cutaneous and mucosal histiocytoses

Group C non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses include a wide variety of entities, with localised skin or mucosa lesions infiltrated by mononuclear and multinuclear CD1a– histiocytes.12

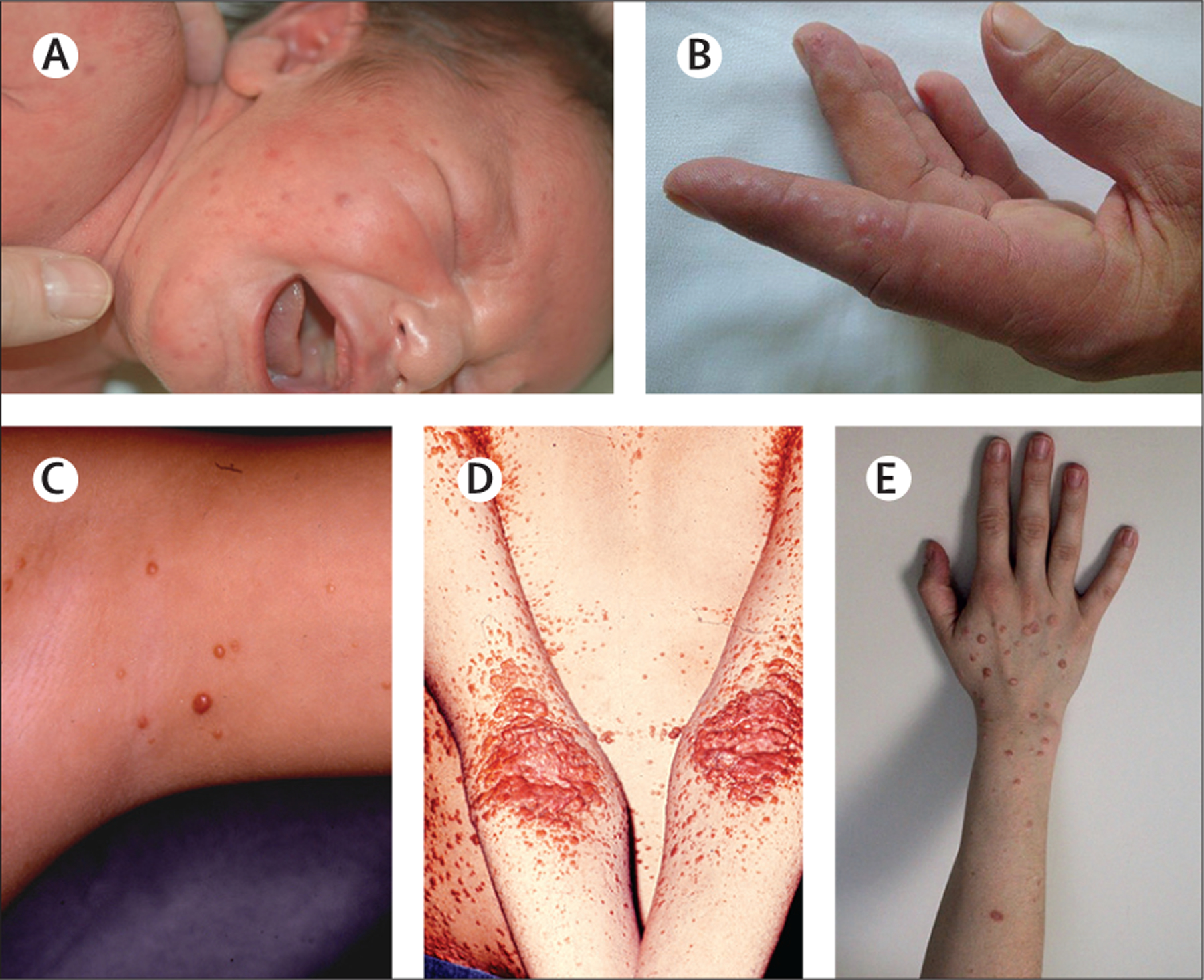

Clinical presentation

Lesions can be red, yellow to brownish papules, nodules, or plaques, depending on fat deposition (figure 4A–E). Juvenile xanthogranuloma is the most frequent group C histiocytosis,106 usually manifesting as a few small nodules appearing during the first years of life, localised on the head and neck or trunk. When multiple juvenile xanthogranuloma nodules are present, they can be associated with chronic uveitis, ocular hypertonia, or hyphaema. Juvenile xanthogranuloma has several variants: micronodular, macronodular, giant (>5 cm), and subcutaneous. The other multiple skin lesions of histiocytoses are classified according to age, clinical features, and their evolution (table 3).

Figure 4: Group C cutaneous histiocytosis.

(A) An infant with multiple benign cephalic histiocytosis lesions. Adults with (B) multicentric reticulohistiocytosis, (C) generalised eruptive histiocytosis, (D) xanthoma disseminatum, and (E) mucinous progressive histiocytosis.

Table 3:

Group C histiocytoses with predominantly cutaneous or mucosal involvement

| Age, sex | Typical locations | Appearance | Clinical differential diagnosis | Evolution and associated conditions | Immunophenotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papular xanthoma* | Adolescents and adults younger than 40 years; male more often than female | Trunk, limbs, head and neck | Solitary yellowish papule or nodule | .. | .. | CD68+, CD163+, FXIIIa−, CD1a− |

| Solitary reticulohistiocytoma | Median age 35 years; male and female equally often | Trunk, limbs, head | Solitary, small (5 mm in diameter) papulonodular lesion | Juvenile xanthogranuloma; dermatofibroma; cyst | Usually no regression | CD68+, CD163+, FXIIIa+/−, CD1a− |

| Juvenile xanthogranuloma | Children more commonly than young adults; male more often than female | Head, neck, upper trunk; buccal possible; any site possible | Single nodule bigger than 2cm in diameter, or multiple papules that are reddish progressing to yellow-brown | Mastocytoma; Spitz naevus; other histiocytoses; dermatofibroma | Gradual involution | CD68+, CD163+, FXIIIa+, CD1a− |

| Benign cephalic histiocytosis | Infants (<1 year); male and female equally often | Head and neck, mostly face; spares mucosae | Multiple papules that are red-brown or sometimes yellowish | Flat warts; juvenile xanthogranuloma; generalised eruptive histiocytosis; mastocytosis | Regression over months or years (median 4 years) | CD68+, CD163+, FXIIIa+, CD1a− |

| Generalised eruptive histiocytosis | Young adults more commonly than children; male more often than female | Trunk and proximal limbs; spares skin folds and mucosae | Innumerable macules and papules that are flesh-coloured to red | Multiple juvenile xanthogranulomas; benign cephalic histiocytosis; xanthoma disseminatum; sarcoidosis; mastocytosis | Involution most often, or progression to xanthogranuloma, xanthoma disseminatum, or nodular progressive histiocytosis in several months or years | CD68+, CD163+, FXIIIa+, CD1a− |

| Nodular progressive histiocytosis | Median age 50 years; male and female equally often | Frequent: buccal, laryngeal, ocular, and genital involvement Possible: face (with leonine appearance), trunk | Multiple or disseminated pink, yellow-orange, or red-brownish lesions up to 5 cm in diameter; two distinct types: deep nodules to tumours, or superficial xanthomatous papules | Generalised eruptive histiocytosis; multiple juvenile xanthogranulomas; xanthoma disseminatum; progressive hereditary mucinous histiocytosis; sarcoidosis; leprosy | Progression | CD68+, CD163+, FXIIIa+, CD1a− |

| Xanthoma disseminatum | Young adults; male more often than female | Any skin, eyelid, skin folds; mucosae involved in 50% of patients, sometimes life-threatening | Hundreds of lesions: symmetrical, coalescing, round to oval, orange to yellow-brown papules and nodules | Multiple juvenile xanthogranuloma; generalised eruptive histiocytosis; eruptive xanthomas | Slow involution over years, or progression; sometimes associated with MGUS, multiple myeloma, or Waldenström’s disease | CD68+, CD163+, FXIIIa+, CD1a− |

| Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis | Median age 40 years; male more often than female | Face, head; periungual (coral bead); mucosae (oral, pharyngeal, nasal) involved in 50% of patients | Flesh-coloured or pink-reddish-brown papules and nodules; pruritus | RDD; leprosy; sarcoidosis; fibroblastic rheumatism | Possible regression but frequent recurrence; symmetrical destructive polyarthritis; rarely lung, heart, or nodal involvement; 25% of patients have an associated cancer, autoimmune disease, or dyslipidaemia | CD68+, CD163+, FXIIIa−, CD1a− |

| Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma | Median age 55 years; male and female equally often | Face, mostly periocular; frequent eye involvement; trunk | Xanthelasmas on upper eyelids, confluent nodules forming firm yellowish plaques; telangiectasias; ulceration; atrophy | Xanthelasma; normolipaemic xanthomas; ECD; lipoidic necrobiosis | In almost all cases: monoclonal gammopathy Possibly: multiple myeloma, CLL, lymphomas | CD68+, CD163+, FXIIIa−, CD1a− |

| Hereditary† progressive mucinous histiocytosis | Younger than 18 years; female more often than male | Face; hands; forearm; legs | Flesh-coloured or red-brown symmetrical papules | Nodular progressive histiocytosis; generalised eruptive histiocytosis; lichen planus; multiple dermatofibromas | No regression | CD68+, CD163+/−, XIIIa+/−, CD1a− |

MGUS=monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. RDD=Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease. ECD=Erdheim-Chester disease. CLL=chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

A normolipaemic xanthoma.

Most cases are hereditary but there are rare sporadic cases.

Treatment and prognosis

Wide excision of juvenile xanothogranuloma is unnecessarily invasive, as it often resolves spontaneously. However, some disseminated group C histiocytoses, especially in adults, might require iterative nodule ablation.107

Malignant histiocytosis

For completeness, we mention malignant histiocytoses, which are extremely rare conditions. The histological diagnosis is difficult, and more than half of around 100 cases seen in the French Histiocytosis Referral Centre were revised to undifferentiated malignant tumours rich in reactive macrophages (Emile JF, unpublished). When associated with another haematological neoplasm, the disorder should be classified as secondary malignant histiocytosis.12 The prognosis is usually poor, but transient responses to chemotherapy or targeted therapy have been reported.108,109,110

Laboratory investigations

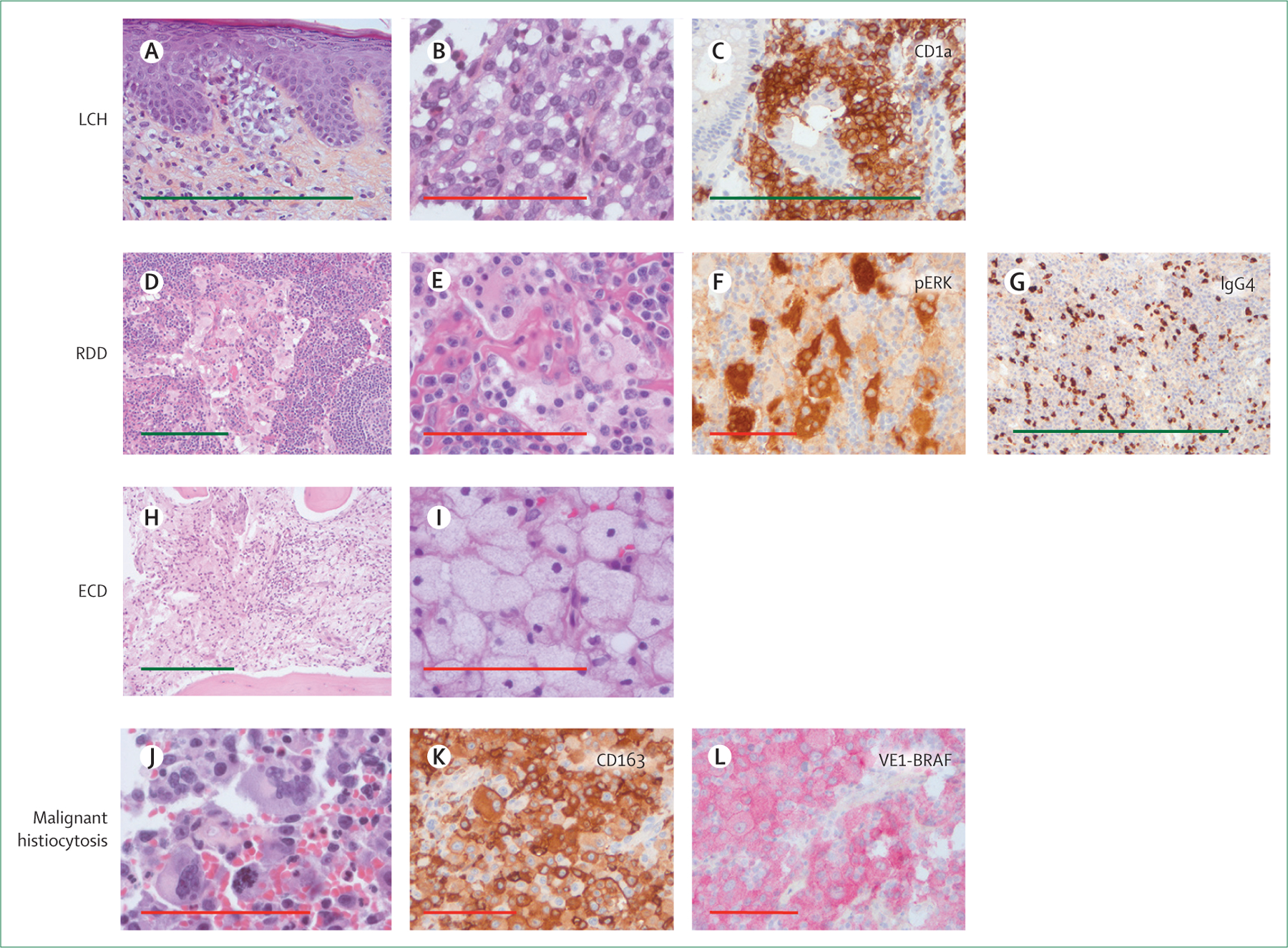

Biopsies should be considered mandatory to exclude differential diagnoses and confirm histiocyte tissue infiltration. Histology, immunolabelling (figure 5A–L), and molecular testing should be done on samples fixed in buffered formalin for 12–72 h. When possible, a specimen other than bone is preferred, because molecular testing on decalcified bone can be difficult. Some reactive lesions (eg, scabies and dermatopathic lymphadenitis) rich in CD1a+ histiocytes can sometimes be mistaken for LCH. Massive histiocyte tissue infiltration in several conditions (eg, Gaucher’s disease, mycobacterial infection in immunocompromised patients) can also lead to erroneous diagnoses of histiocytosis. Therefore, histology is mandatory but only supportive, and clinical and radiological findings should be at least consistent and at best typical.

Figure 5: Histology of some histiocytoses.

Histology of formalin-fixed biopsy specimens with infiltration by: LCH (A, B, C); RDD (D, E, F, G); ECD (H, I); or malignant histiocytosis (J, K, L). Original magnifications were ×40 (D, H), ×100 (A), and ×400 (B, E, I, J) for haematoxylin and eosin staining; and ×100 (C, G) and ×200 (F, K, L) for immunohistochemistry. Green scale bar is 500 μm. Red scale bar is 100 μm. LCH=Langerhans cell histiocytosis. RDD=Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease. ECD=Erdheim-Chester disease. VE1-BRAF=clone specific to BRAFV600E.

Diagnoses of all atypical and malignant diseases should be confirmed at expert centres. Immunohistochemistry is also mandatory for diagnosis, with at least: CD1a and CD207 for LCH; CD1a, S100, and a macrophage marker (CD163 or CD68) for RDD; and CD1a and a macrophage marker (CD163 or CD68) for ECD. Finally, phospho-ERK1/2 labelling can be useful for considering targeted therapy.

Detection of mutations in genes in the MAP kinase pathway is becoming increasingly useful to confirm difficult diagnoses and is important for all multisystem histiocytoses. Among 197 adults whose biopsies showed clear histiocytic infiltration, BRAFV600E allele frequency was less than 5% in 49 (24.8%) patients;111 thus, techniques to detect mutations must have high sensitivity. Cell-free DNA in serum or plasma (liquid biopsy) can help detect mutant DNA in plasma, but test negativity does not exclude the presence of mutations in affected tissues. Indeed, detection of mutations might depend on the extent of disease.112,113 BRAFV600E is also detectable in whole blood,114 plasma,112,115 or urine of patients with LCH or ECD.115

Minimum initial laboratory evaluations include full blood count, C-reactive protein, albumin, renal function tests, and liver function tests. Patients with RDD or ECD should also be tested for autoimmunity.3,82 Patients with anaemia should have direct antiglobulin test, haptoglobin, reticulocyte count, and blood smear analysed; bone-marrow investigation is recommended for those with cytopenia or abnormal differential leukocyte count.

Controversies, uncertainties, and outstanding research questions

Ontogeny and classification

Until recently, histiocytoses were considered idiopathic inflammatory diseases. The discovery of clonal oncogenic mutations in most patients with LCH or ECD showed that these conditions are rooted in neoplasia.48 For the 10% of patients with ECD who have concomitant myeloid malignancy (eg, myelodysplastic syndrome or a myeloproliferative neoplasm or an overlap syndrome of the two),83 their histiocytes, blood monocytes, and blood progenitor cells harbour the same mutation, and some of these patients have the same mutations in tumour suppressor genes (eg, TET2, SRSF2, and others),28,116 suggesting the existence of a clonal histiocyte progenitor. However, direct involvement of myeloid progenitor cells has only been shown in 30–50% of adults and a minority of paediatric cases.23,116,117 The association between group L histiocytosis and myelodysplastic syndrome or myeloproliferative neoplasms, and the higher frequencies of epigenetic controlling-gene mutations driving these diseases, are strongly reminiscent of mastocytoses.118 Indeed, in histiocytosis and mastocytosis, a bone marrow progenitor, with a few acquired genetic alterations, can generate a clone or subclone that is able to initiate pathological tissue infiltration by mature mast cells or histiocytes and potentially cause myelodysplastic syndrome or a myeloproliferative neoplasm.

Some malignant histiocytoses are associated with lymphoma and share common gene translocations or immunoglobulin rearrangements.119 Moreover, the WHO classification places histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms under lymphoid neoplasms.10 However, substantial evidence led the Histiocyte Society to classify histiocytoses as neoplasms of myeloid origin.2,4,6,12

Optimising targeted therapies

The European Medicines Agency granted orphan disease designation to LCH (May, 2016) and ECD (February, 2017), thereby authorising vemurafenib use for both conditions. The US Food and Drug Administration also approved vemurafenib for patients with ECD with BRAF mutation (November, 2017) and granted breakthrough therapy designation for its use in histiocytoses (October, 2019). Those authorisations are supported by the major clinical benefits obtained in adults39–41,73 and children37,38 carrying BRAFV600E. Despite the absence of prospective, randomised, phase 3 clinical trials, vemurafenib is the standard treatment for patients with active and refractory group L histiocytoses with the BRAFV600E mutation. Patients intolerant of vemurafenib might also benefit from other BRAF or MEK inhibitors.96 Furthermore, most active and refractory histiocytoses involving activation of the MAP kinase pathway also achieve major clinical responses to a MEK inhibitor,74,95 and we recommend this treatment for this indication.

However, several important questions remain to be answered. Which patients should receive first-line inhibitors? A few case reports argue for treating adults in emergency settings.80,81 However, BRAF and MEK inhibitors can cause severe adverse events and their long-term toxic effects remain unknown in children and adults. Therefore, recommendations support multidisciplinary team meetings between specialists experienced in histiocytoses before any patient receives targeted therapy.

For how long is treatment required? BRAF or MEK inhibitors induce major clinical and metabolic responses in almost all patients, but in a vemurafenib basket trial only six (43%) of 14 patients responded according to RECIST (response evaluation criteria in solid tumours),41 and in another study of vemurafenib, nine (75%) of 12 responders still had mutant BRAF detectable in their plasma more than 6 months after starting treatment.37 Furthermore, 15 (75%) of 20 adults,96 and 24 (80%) of 30 children37 relapsed after stopping inhibitor therapy. Thus, in the absence of severe adverse effects, treatment with vemurafenib should not be interrupted during the first 18 months of administration. As is the case for treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia with imatinib,120 we suspect that prolonging treatment and mutant-BRAF clearance from plasma might become helpful predictors of recurrence after treatment discontinuation; however, that remains to be proven prospectively. In addition, combinations of BRAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors warrant investigation, as was done for melanomas.121

Another area in need of research is degenerative neurohistiocytosis. This is a severe complication of group L histiocytosis, the pathophysiological mechanisms of which remain unelucidated. A paraneoplastic syndrome has been suspected. Recent post-mortem analyses of patients’ brains with degenerative lesions revealed BRAFV600E-positivity in a few cells in atrophic areas.122,123 Notably, Mass and colleagues recently developed a model that might have important clinical impact.122 They studied genetically modified mice with a small fraction of microglia expressing a Braf mutation. Carriers of this mutation progressively developed clinical and histological signs of neurodegeneration; early vemurafenib administration delayed the onset of neurodegenerative disease. No consensus exists for the treatment of neurodegenerative symptoms and CNS lesions.

Conclusion

The last decade has seen significant progress made in the field of histiocytoses. Many advances have resulted from the discovery of somatic clonal molecular alterations in tissue samples. Active research networks dedicated to these rare diseases have accelerated that progress. Further analyses and clustering of clinical, imaging, histological, and molecular characteristics of large series of children and adults with histiocytosis will help better define homogeneous or overlapping entities, and assess optimal preventive or curative treatments.

Supplementary Material

Search strategy and selection criteria.

We searched PubMed and Embase for relevant articles on histiocytosis. For PubMed, the key search terms included: “histiocytos*”, “Erdheim Chester”, “Rosai Dorfman”, “sarcoma” AND (“dendritic” OR “Langerhans” OR “histiocyt*”) OR (“LCH” AND “Langerhans*”) OR (“Histiocytosis”). We reviewed articles published between Jan 1, 2010, and Jan 14, 2021. For Embase, the key search terms included: “histiocytosis”, “sinus histiocytosis”. We reviewed articles published between Jan 1, 2010, and Jan 14, 2021. For both PubMed and Embase, we reviewed only articles written in English. We selected articles on the basis of relevance to this Seminar, evaluated by reading at least the abstract; for citation in this Seminar we favoured the more recent original articles. For full search strings, please see appendix p 14.

Acknowledgments

We thank the physicians who provided clinical or metabolic pictures of histiocytoses (A Aouba, D Bessis, C Bodemer, F Cambazard, P Maksud, V Pallure, and O Sangueza), as well as Janet Jacobson for editorial assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Programme de Recherche Translationnelle en Cancérologie (grant reference 19–143) and from the Association pour le Recherche et l'Enseignement en Pathologie. This Seminar is dedicated to the memory of our dear friend and colleague, Johannes Visser.

Footnotes

See Online for appendix

Declaration of interests

OA-W reports personal fees from Envisagenics, Pfizer Boulder, AIChemy, Janssen, Merck, H3 Biomedicine, Prelude Therapeutics, and Foundation Medicine, and grants from LOXO Oncology, during the conduct of the study. FC-A and JH are investigators (FC-A being the principal investigator) of an academic study on the efficacy of cobimetinib for treating histiocytoses (COBRAH, NCT 04007848). AI reports grants, research support, and travel funding from Carthera; grants from Transgene, Sanofi, Air Liquide, and Nutritheragene; personal fees from Novocure; and personal fees and travel funding from Leo Pharma, outside the submitted work. BJR received reimbursement for travel and lodging expenses from Eli Lilly and Company. JD reports grants from X4 Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Jean-François Emile, EA4340 BECCOH, Université de Versailles SQY, Service de Pathologie, Hôpital Ambroise Paré, AP-HP, Boulogne, France.

Fleur Cohen-Aubart, Internal Medicine Department 2, French National Referral Center for Rare Systemic Diseases and Histiocytoses, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, AP-HP and Sorbonne Université, Paris, France.

Matthew Collin, Translational and Clinical Research Institute, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

Sylvie Fraitag, Pathology Department, Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital, AP-HP, Paris, France.

Ahmed Idbaih, UMR S 1127, CNRS/Inserm, Institut du Cerveau et de la Moelle Épinière, Hôpitaux Universitaires La Pitié Salpêtrière-Charles Foix, AP-HP and Sorbonne Université, Paris, France.

Omar Abdel-Wahab, Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Barrett J Rollins, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Department of Medicine, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Jean Donadieu, EA4340 BECCOH, Université de Versailles SQY, Service de Pathologie, Hôpital Ambroise Paré, AP-HP, Boulogne, France; Service d’Hématologie Oncologie Pédiatrique, Centre de Référence des Histiocytoses, Hôpital Armand-Trousseau, AP-HP, Paris, France.

Julien Haroche, Internal Medicine Department 2, French National Referral Center for Rare Systemic Diseases and Histiocytoses, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, AP-HP and Sorbonne Université, Paris, France.

References

- 1.Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society. Histiocytosis syndromes in children. Lancet 1987; 1: 208–09. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Rollins BJ, et al. Histiocytoses: emerging neoplasia behind inflammation. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: e113–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abla O, Jacobsen E, Picarsic J, et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and clinical management of Rosai-Dorfman-Destombes disease. Blood 2018; 131: 2877–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez-Galindo C, Allen CE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 2020; 135: 1319–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goyal G, Heaney ML, Collin M, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease: consensus recommendations for evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment in the molecular era. Blood 2020; 135: 1929–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen CE, Beverley PCL, Collin M, et al. The coming of age of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Nat Immunol 2020; 21: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hervier B, Haroche J, Arnaud L, et al. Association of both Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Erdheim-Chester disease linked to the BRAFV600E mutation. Blood 2014; 124: 1119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Razanamahery J, Diamond EL, Cohen-Aubart F, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease with concomitant Rosai-Dorfman like lesions: a distinct entity mainly driven by MAP2K1. Haematologica 2020; 105: e5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muma S, Brotherton BJ, Halestrap P. Empirical treatment of massive lymphadenopathy in a child with mixed type histiocytosis in Kenya. Lancet 2020; 395: e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016; 127: 2375–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halbritter F, Farlik M, Schwentner R, et al. Epigenomics and single-cell sequencing define a developmental hierarchy in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Cancer Discov 2019; 9: 1406–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emile J-F, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood 2016; 127: 2672–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durham BH, Lopez Rodrigo E, Picarsic J, et al. Activating mutations in CSF1R and additional receptor tyrosine kinases in histiocytic neoplasms. Nat Med 2019; 25: 1839–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fatobene G, Haroche J, Hélias-Rodzwicz Z, et al. BRAF V600E mutation detected in a case of Rosai-Dorfman disease. Haematologica 2018; 103: e377–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egan C, Nicolae A, Lack J, et al. Genomic profiling of primary histiocytic sarcoma reveals two molecular subgroups. Haematologica 2020; 105: 951–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garces S, Medeiros LJ, Patel KP, et al. Mutually exclusive recurrent KRAS and MAP2K1 mutations in Rosai-Dorfman disease. Mod Pathol 2017; 30: 1367–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badalian-Very G, Vergilio J-A, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 2010; 116: 1919–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002; 417: 949–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu RC, Chu C, Buluwela L, Chu AC. Clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Lancet 1994; 343: 767–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satoh T, Smith A, Sarde A, et al. B-RAF mutant alleles associated with Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a granulomatous pediatric disease. PLoS One 2012; 7: e33891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haroche J, Charlotte F, Arnaud L, et al. High prevalence of BRAF V600E mutations in Erdheim-Chester disease but not in other non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Blood 2012; 120: 2700–03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Go H, Jeon YK, Huh J, et al. Frequent detection of BRAF V600E mutations in histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms. Histopathology 2014; 65: 261–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berres M-L, Lim KPH, Peters T, et al. BRAF-V600E expression in precursor versus differentiated dendritic cells defines clinically distinct LCH risk groups. J Exp Med 2014; 211: 669–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emile J-F, Diamond EL, Hélias-Rodzewicz Z, et al. Recurrent RAS and PIK3CA mutations in Erdheim-Chester disease. Blood 2014; 124: 3016–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Héritier S, Emile J-F, Barkaoui M-A, et al. BRAF mutation correlates with high-risk Langerhans cell histiocytosis and increased resistance to first-line therapy. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 3023–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chakraborty R, Hampton OA, Shen X, et al. Mutually exclusive recurrent somatic mutations in MAP2K1 and BRAF support a central role for ERK activation in LCH pathogenesis. Blood 2014; 124: 3007–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diamond EL, Durham BH, Haroche J, et al. Diverse and targetable kinase alterations drive histiocytic neoplasms. Cancer Discov 2016; 6: 154–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee LH, Gasilina A, Roychoudhury J, et al. Real-time genomic profiling of histiocytoses identifies early-kinase domain BRAF alterations while improving treatment outcomes. JCI Insight 2017; 2: e89473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakraborty R, Burke TM, Hampton OA, et al. Alternative genetic mechanisms of BRAF activation in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 2016; 128: 2533–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Héritier S, Hélias-Rodzewicz Z, Chakraborty R, et al. New somatic BRAF splicing mutation in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Mol Cancer 2017; 16: 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson DS, Quispel W, Badalian-Very G, et al. Somatic activating ARAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 2014; 123: 3152–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson DS, van Halteren A, Quispel WT, et al. MAP2K1 and MAP3K1 mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2015; 54: 361–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang KTE, Tay AZE, Kuick CH, et al. ALK-positive histiocytosis: an expanded clinicopathologic spectrum and frequent presence of KIF5B-ALK fusion. Mod Pathol 2019; 32: 598–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson TE, Wachsmann M, Oliver D, et al. BRAF mutation leading to central nervous system rosai-dorfman disease. Ann Neurol 2018; 84: 147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martincorena I, Fowler JC, Wabik A, et al. Somatic mutant clones colonize the human esophagus with age. Science 2018; 362: 911–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson DS, Marano RL, Joo Y, et al. BRAF V600E and Pten deletion in mice produces a histiocytic disorder with features of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0222400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donadieu J, Larabi IA, Tardieu M, et al. Vemurafenib for refractory multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: an international observational study. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 2857–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Héritier S, Jehanne M, Leverger G, et al. Vemurafenib use in an infant for high-risk Langerhans cell histiocytosis. JAMA Oncol 2015; 1: 836–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile J-F, et al. Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood 2013; 121: 1495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Emile J-F, et al. Reproducible and sustained efficacy of targeted therapy with vemurafenib in patients with BRAF(V600E)-mutated Erdheim-Chester disease. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 411–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, et al. Vemurafenib in Multiple Nonmelanoma Cancers with BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 726–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yasmin N, Bauer T, Modak M, et al. Identification of bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7) as an instructive factor for human epidermal Langerhans cell differentiation. J Exp Med 2013; 210: 2597–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGovern N, Schlitzer A, Gunawan M, et al. Human dermal CD14+ cells are a transient population of monocyte-derived macrophages. Immunity 2014; 41: 465–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science 2010; 330: 841–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schulz C, Gomez Perdiguero E, Chorro L, et al. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science 2012; 336: 86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collin M, Bigley V. Human dendritic cell subsets: an update. Immunology 2018; 154: 3–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emile JF, Haddad E, Fraitag S, Canioni D, Fischer A, Brousse N. Detection of donor-derived Langerhans cells in MHC class II immunodeficient patients after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Br J Haematol 1997; 98: 480–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Collin MP, Hart DNJ, Jackson GH, et al. The fate of human Langerhans cells in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Exp Med 2006; 203: 27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson RL, Boisot S, Ball ED, Wang H-Y. A case of interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma/histiocytic sarcoma--a diagnostic pitfall. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2013; 7: 378–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dupeux M, Boccara O, Frassati-Biaggi A, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytoma: a benign histiocytic neoplasm of diverse lines of terminal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol 2019; 41: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sahm F, Capper D, Preusser M, et al. BRAFV600E mutant protein is expressed in cells of variable maturation in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 2012; 120: e28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, Bellec S, Thomas C, Clavel J. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008; 51: 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peckham-Gregory EC, Chakraborty R, Scheurer ME, et al. A genome-wide association study of LCH identifies a variant in SMAD6 associated with susceptibility. Blood 2017; 130: 2229–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singhi AD, Montgomery EA. Gastrointestinal tract Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a clinicopathologic study of 12 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 2011; 35: 305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH): guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 years. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013; 60: 175–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braier J, Rosso D, Pollono D, et al. Symptomatic bone langerhans cell histiocytosis treated at diagnosis or after reactivation with indomethacin alone. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014; 36: e280–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Donadieu J, Bernard F, van Noesel M, et al. Cladribine and cytarabine in refractory multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis: results of an international phase 2 study. Blood 2015; 126: 1415–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weitzman S, Braier J, Donadieu J, et al. 2'-Chlorodeoxyadenosine (2-CdA) as salvage therapy for Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). results of the LCH-S-98 protocol of the Histiocyte Society. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009; 53: 1271–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barkaoui MA, Queheille E, Aladjidi N, et al. Long-term follow-up of children with risk organ-negative Langerhans cell histiocytosis after 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine treatment. Br J Haematol 2020; 191: 825–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gadner H, Minkov M, Grois N, et al. Therapy prolongation improves outcome in multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 2013; 121: 5006–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Donadieu J, Piguet C, Bernard F, et al. A new clinical score for disease activity in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2004; 43: 770–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rigaud C, Barkaoui MA, Thomas C, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: therapeutic strategy and outcome in a 30-year nationwide cohort of 1478 patients under 18 years of age. Br J Haematol 2016; 174: 887–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Héritier S, Barkaoui M-A, Miron J, et al. Incidence and risk factors for clinical neurodegenerative Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a longitudinal cohort study. Br J Haematol 2018; 183: 608–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nanduri VR, Pritchard J, Levitt G, Glaser AW. Long term morbidity and health related quality of life after multi-system Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur J Cancer 2006; 42: 2563–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goyal G, Shah MV, Hook CC, et al. Adult disseminated Langerhans cell histiocytosis: incidence, racial disparities and long-term outcomes. Br J Haematol 2018; 182: 579–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Colby TV, Hartman T, Limper AH. Pulmonary Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1969–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Le Guen P, Chevret S, Bugnet E, et al. Management and outcomes of pneumothorax in adult patients with Langerhans cell Histiocytosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2019; 14: 229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abdallah M, Généreau T, Donadieu J, et al. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the liver in adults. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2011; 35: 475–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Girschikofsky M, Arico M, Castillo D, et al. Management of adult patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of Euro-Histio-Net. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013; 8: 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Courtillot C, Laugier Robiolle S, Cohen Aubart F, et al. Endocrine manifestations in a monocentric cohort of 64 patients with Erdheim-Chester disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101: 305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sagna Y, Courtillot C, Drabo JY, et al. Endocrine manifestations in a cohort of 63 adulthood and childhood onset patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur J Endocrinol 2019; 181: 275–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cao XX, Li J, Zhao AL, et al. Methotrexate and cytarabine for adult patients with newly diagnosed Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a single arm, single center, prospective phase 2 study. Am J Hematol 2020; 95: E235–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Diamond EL, Subbiah V, Lockhart AC, et al. Vemurafenib for BRAF V600-mutant Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis: analysis of data from the histology-independent, phase 2, open-label VE-BASKET Study. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4: 384–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Diamond EL, Durham BH, Ulaner GA, et al. Efficacy of MEK inhibition in patients with histiocytic neoplasms. Nature 2019; 567: 521–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cohen-Aubart F, Emile J-F, Carrat F, et al. Phenotypes and survival in Erdheim-Chester disease: Results from a 165-patient cohort. Am J Hematol 2018; 93: E114–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chasset F, Barete S, Charlotte F, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD): Clinical, pathological, and molecular features in a monocentric series of 40 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74: 513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Picarsic J, Pysher T, Zhou H, et al. BRAF V600E mutation in Juvenile Xanthogranuloma family neoplasms of the central nervous system (CNS-JXG): a revised diagnostic algorithm to include pediatric Erdheim-Chester disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2019; 7: 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sandoval-Sus JD, Sandoval-Leon AC, Chapman JR, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease of the central nervous system: report of 6 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014; 93: 165–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hunt D, Milne P, Fernandes P, Bigley V, Collin M. Targeted treatment of brainstem neurohistiocytosis guided by urinary cell-free DNA. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2016; 4: e299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cohen-Aubart F, Emile J-F, Maksud P, et al. Marked efficacy of vemurafenib in suprasellar Erdheim-Chester disease. Neurology 2014; 83: 1294–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Euskirchen P, Haroche J, Emile J-F, Buchert R, Vandersee S, Meisel A. Complete remission of critical neurohistiocytosis by vemurafenib. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015; 2: e78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Roeser A, Cohen-Aubart F, Breillat P, et al. Autoimmunity associated with Erdheim-Chester disease improves with BRAF/MEK inhibitors. Haematologica 2019; 104: e502–05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Papo M, Diamond EL, Cohen-Aubart F, et al. High prevalence of myeloid neoplasms in adults with non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 2017; 130: 1007–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Arnaud L, Pierre I, Beigelman-Aubry C, et al. Pulmonary involvement in Erdheim-Chester disease: a single-center study of thirty-four patients and a review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62: 3504–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haroche J, Cluzel P, Toledano D, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Cardiac involvement in Erdheim-Chester disease: magnetic resonance and computed tomographic scan imaging in a monocentric series of 37 patients. Circulation 2009; 119: e597–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gianfreda D, Palumbo AA, Rossi E, et al. Cardiac involvement in Erdheim-Chester disease: an MRI study. Blood 2016; 128: 2468–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Diamond EL, Hatzoglou V, Patel S, et al. Diffuse reduction of cerebral grey matter volumes in Erdheim-Chester disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2016; 11: 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Drier A, Haroche J, Savatovsky J, et al. Cerebral, facial, and orbital involvement in Erdheim-Chester disease: CT and MR imaging findings. Radiology 2010; 255: 586–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Arnaud L, Hervier B, Néel A, et al. CNS involvement and treatment with interferon-α are independent prognostic factors in Erdheim-Chester disease: a multicenter survival analysis of 53 patients. Blood 2011; 117: 2778–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cohen-Aubart F, Maksud P, Saadoun D, et al. Variability in the efficacy of the IL1 receptor antagonist anakinra for treating Erdheim-Chester disease. Blood 2016; 127: 1509–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cohen-Aubart F, Maksud P, Emile J-F, et al. Efficacy of infliximab in the treatment of Erdheim-Chester disease. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77: 1387–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gianfreda D, Nicastro M, Galetti M, et al. Sirolimus plus prednisone for Erdheim-Chester disease: an open-label trial. Blood 2015; 126: 1163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Berti A, Cavalli G, Guglielmi B, et al. Tocilizumab in patients with multisystem Erdheim-Chester disease. OncoImmunology 2017; 6: e1318237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goyal G, Shah MV, Call TG, Litzow MR, Hogan WJ, Go RS. Clinical and radiologic responses to cladribine for the treatment of Erdheim-Chester Disease. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3: 1253–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cohen Aubart F, Emile J-F, Maksud P, et al. Efficacy of the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib for wild-type BRAF Erdheim-Chester disease. Br J Haematol 2018; 180: 150–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cohen Aubart F, Emile J-F, Carrat F, et al. Targeted therapies in 54 patients with Erdheim-Chester disease, including follow-up after interruption (the LOVE study). Blood 2017; 130: 1377–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Arnaud L, Malek Z, Archambaud F, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography scanning is more useful in followup than in the initial assessment of patients with Erdheim-Chester disease. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60: 3128–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ghobadi A, Miller CA, Li T, et al. Shared cell of origin in a patient with Erdheim-Chester disease and acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2019; 104: e373–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Molho-Pessach V, Ramot Y, Camille F, et al. H syndrome: the first 79 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 70: 80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maric I, Pittaluga S, Dale JK, et al. Histologic features of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy in patients with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 2005; 29: 903–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jacobsen E, Shanmugam V, Jagannathan J. Rosai-Dorfman disease with activating KRAS mutation - response to cobimetinib. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 2398–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Moyon Q, Boussouar S, Maksud P, et al. Lung involvement in Destombes-Rosai-Dorfman disease: clinical and radiological features and response to the MEK inhibitor cobimetinib. Chest 2020; 157: 323–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol 1990; 7: 19–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Menon MP, Evbuomwan MO, Rosai J, Jaffe ES, Pittaluga S. A subset of Rosai-Dorfman disease cases show increased IgG4-positive plasma cells: another red herring or a true association with IgG4-related disease? Histopathology 2014; 64: 455–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Andriko JA, Morrison A, Colegial CH, Davis BJ, Jones RV. Rosai-Dorfman disease isolated to the central nervous system: a report of 11 cases. Mod Pathol 2001; 14: 172–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]