Abstract

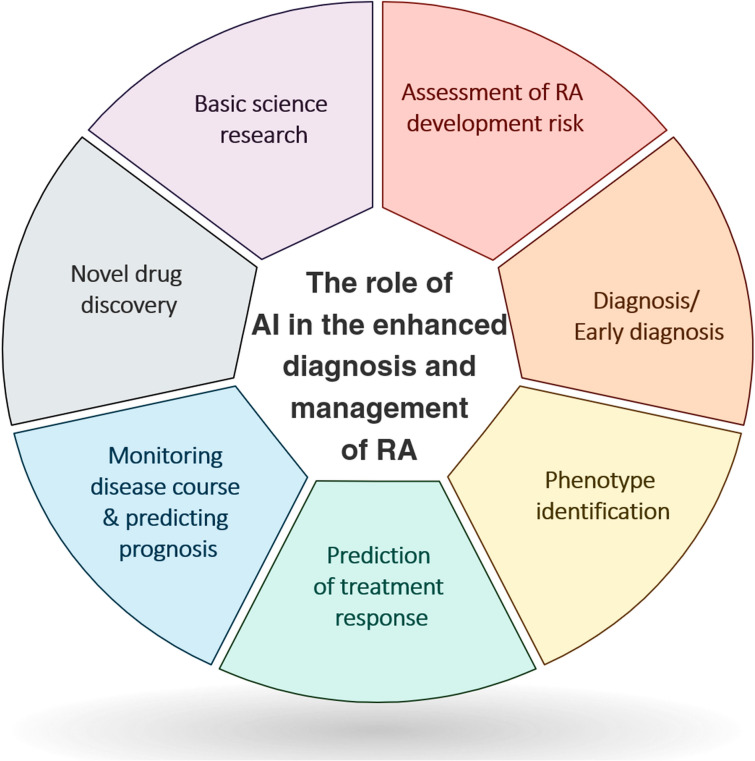

Investigation of the potential applications of artificial intelligence (AI), including machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques, is an exponentially growing field in medicine and healthcare. These methods can be critical in providing high-quality care to patients with chronic rheumatological diseases lacking an optimal treatment, like rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which is the second most prevalent autoimmune disease. Herein, following reviewing the basic concepts of AI, we summarize the advances in its applications in RA clinical practice and research. We provide directions for future investigations in this field after reviewing the current knowledge gaps and technical and ethical challenges in applying AI. Automated models have been largely used to improve RA diagnosis since the early 2000s, and they have used a wide variety of techniques, e.g., support vector machine, random forest, and artificial neural networks. AI algorithms can facilitate screening and identification of susceptible groups, diagnosis using omics, imaging, clinical, and sensor data, patient detection within electronic health record (EHR), i.e., phenotyping, treatment response assessment, monitoring disease course, determining prognosis, novel drug discovery, and enhancing basic science research. They can also aid in risk assessment for incidence of comorbidities, e.g., cardiovascular diseases, in patients with RA. However, the proposed models may vary significantly in their performance and reliability. Despite the promising results achieved by AI models in enhancing early diagnosis and management of patients with RA, they are not fully ready to be incorporated into clinical practice. Future investigations are required to ensure development of reliable and generalizable algorithms while they carefully look for any potential source of bias or misconduct. We showed that a growing body of evidence supports the potential role of AI in revolutionizing screening, diagnosis, and management of patients with RA. However, multiple obstacles hinder clinical applications of AI models. Incorporating the machine and/or deep learning algorithms into real-world settings would be a key step in the progress of AI in medicine.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, Autoimmune diseases, Artificial intelligence, Deep learning, Diagnosis, Imaging, Machine learning, Natural language processing, Precision medicine, Treatment

Key Summary Points

| Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is among the most common rheumatologic diseases. |

| Precision medicine with the aid of artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming more common each day. |

| Numerous machine learning and deep learning algorithms exist that could assist physicians in every step of RA care, including primary prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation. |

| Nonetheless, many challenges exist in the path of expanding AI-guided precision medicine, and especially its application in RA, which could and should be overcome through multi-disciplinary scientific effort. |

Introduction

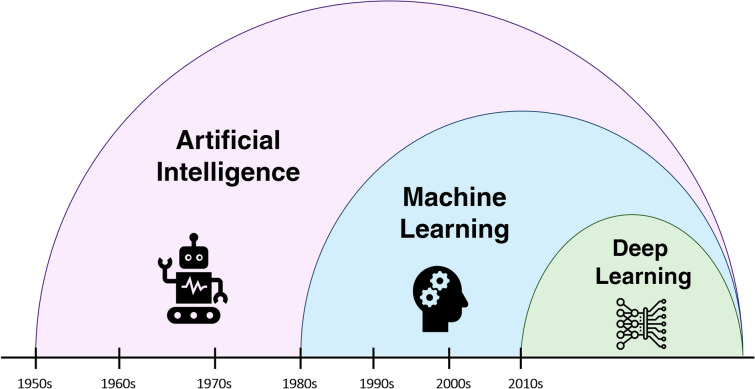

Artificial intelligence (AI) is defined as "the capability of a machine to imitate intelligent human behavior" [1]. In today's world, technologies are expanding faster than ever, with capabilities one could have never thought of in the past. Machines are now able to perform tasks not only as good as humans, but even at higher qualities in many instances. AI is being used in various scientific fields, and medicine is not an exception [2]. Researchers in almost all healthcare sectors and specialties are now studying potential applications of AI, ranging from image processing in pathology [3] and radiology [4], precision medicine, and drug discovery [5] to making estimations and predictions in public health [6]. Machine learning (ML) is a branch of AI, in which the intelligence mentioned above is acquired through practice, similar to how a human learns skills. ML improved significantly in the early 2010s with the introduction of deep learning (DL) [7], which is basically combining multiple ML processes with each other [8].

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the second most prevalent autoimmune disease, with an estimated global prevalence of nearly 20 million cases as of 2019 [9, 10]. The disease is characterized by destructive joint changes starting in the small joints of extremities and may continue to involve larger joints if left untreated. Rheumatoid arthritis is diagnosed clinically, and the lack of well-established diagnostic criteria [11] or a gold standard test makes the diagnosis challenging. Several classification methods have been proposed to distinguish RA from other autoimmune diseases and also stratify patients based on their disease characteristics [11]. Currently, the 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) classification system is the most commonly used criteria for RA diagnosis and classification [12]. Treatment of RA aims to reduce inflammation and joint destruction. Initial therapies include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids, followed by disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) [13]. Methotrexate (MTX) is the initial DMARD choice, although it may be substituted or accompanied by other treatments if indicated [13].

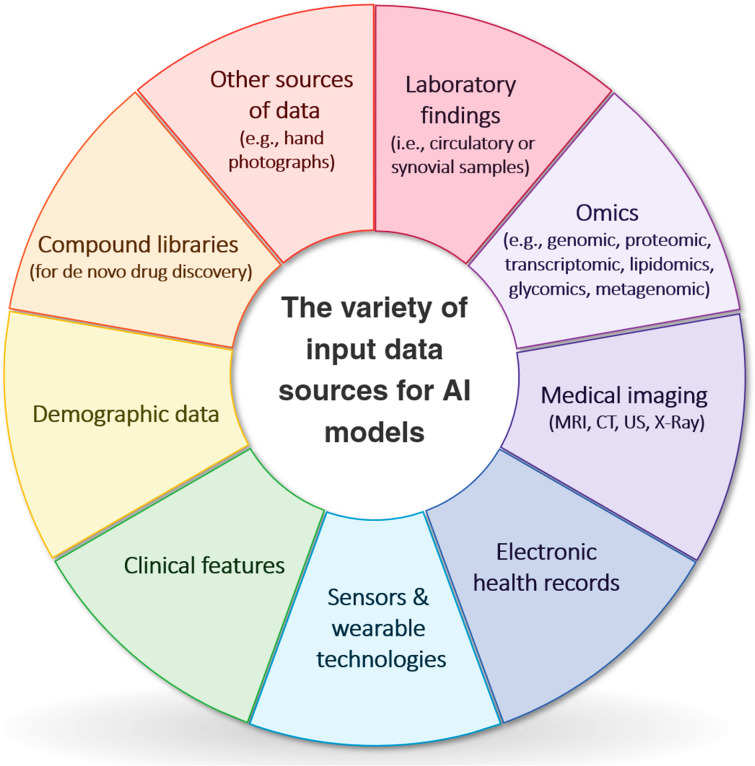

The medicine we know today is a result of experiments and, more precisely, data analysis. Therefore, utilizing the vast amount of the currently available data in the most efficient way is of great value. As evaluating all these data is virtually impossible for humans, AI helps us achieve this goal by incorporating machine-like speed and human-like comprehension. Almost all available data could be used by AI systems: laboratory findings, omics data, medical images, electronic health records (EHRs), data derived from sensors and wearable technologies, clinical features, demographic data, etc. (Fig. 1). The results obtained from these inputs could provide us with useful insights into various aspects of a disease, such as its pathophysiology and epidemiologic features. They could also assist researchers in discovering novel diagnostic methods and biomarkers, leading to quicker and more accurate diagnoses. Moreover, given the invaluable benefits of precision medicine [14], AI algorithms are able to tailor medical services and treatments for each patient according to their unique biological profile (e.g., genomics) and disease status.

Fig. 1.

The variety of input data sources for artificial intelligence (AI) models, CT computed tomography, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, US ultrasound

Given the emerging role of AI in diagnosis, monitoring, and management of autoimmune rheumatologic diseases, including RA, a thorough understanding of the achievements that have been obtained so far in the field and the existing knowledge gaps is critical to facilitate their incorporation into clinical practice and delineate the path for future studies. In this study, after reviewing the basic concepts of AI, we provide an updated comprehensive summary of the advances and applications of AI in RA clinical practice and research. Furthermore, we point out areas with a paucity of literature and challenges that have to be addressed and provide future directions for researchers on this topic.

Methods

We conducted an online search using PubMed in March 2022 using the following keywords: "rheumatoid arthritis" AND ("artificial intelligence" OR "machine learning" OR "machine intelligence" OR "computational intelligence" OR "deep learning" OR "neural network*" OR "convolutional network*" OR "Bayesian learning" OR "random forest" OR "reinforcement learning" OR "hierarchical learning" OR "computer vision"). No publication date or study type limit was applied to the search. We also searched the reference lists of the retrieved studies for identification of potentially relevant studies. Study selection was independently performed by two reviewers (SM and AN). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments. It is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning

Artificial intelligence is a domain of computer sciences referring to a wide variety of interdisciplinary approaches aimed at enhancing machine capabilities. Machine learning is a subdiscipline of AI constituted of techniques for complex problem solving by automatedly learning the patterns of interaction between variables without explicit programming [15]. Compared to traditional statistical models that are hypothesis-driven and aim to identify relationships between outcomes and datapoints, ML approaches learn from the data, and their goal is to make accurate predictions with less focus on inference. Deep learning is a subset of ML identifying patterns in data using a layered structure of artificial neural networks (Fig. 2). In the past decade, due to the enhancement of computational power and availability of massive datasets, DL has been at the forefront of image analysis, genomic analysis, and drug discovery [16]. Compared to ML approaches (e.g., logistic regression, support vector machine (SVM), and random forest), DL models can perform more complex tasks; however, they require larger training data and longer training time. Moreover, DL models are able to process high-dimensionality data, such as medical images and EHRs [17]. Table 1 depicts the fundamental concepts in the most commonly used ML algorithms and neural networks.

Fig. 2.

Evolution of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and deep learning

Table 1.

Fundamental concepts in the most commonly used artificial intelligence algorithms

The process in which an ML algorithm learns to produce the desired outcome is called "training". Machine learning approaches are commonly categorized into three broad classes based on their training method, namely supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning [18]. In supervised learning, models are trained to predict future values by learning patterns from known input and output data. Random forest, SVM, neural networks, and natural language processing (NLP) models are some of the most popular supervised approaches (Table 1). Natural language processing models aim to analyze text and speech by inferring the words and can be utilized in EHR analysis [19]. In contrast to supervised learning, in unsupervised learning, the goal is not assigning the correct label, but inferring underlying patterns and relationships within the input (e.g., finding clusters within the data by reducing data dimensionality) [15]. In reinforcement learning, the model learns to achieve a specific goal by interacting with its environment through trial and error, demonstration, or a hybrid approach. In healthcare, reinforcement learning is commonly used in models applied in robotic surgery [19].

Understanding the fundamental concepts of AI familiarize physicians with the potential application of AI-based models in their clinical practice and helps them detect robust models applicable in practice. Several guidelines have been developed to ensure production of reliable models. Multiple items should be considered when assessing the robustness of an algorithm, including the size of the dataset used to train the model (as more training data results in a more precise model), external validation of the model, significance of the clinical problem addressed by the model, performance of the model compared to other algorithms or clinician performance, and availability of the utilized algorithm on public repositories, which can enable independent validation of the performance and reproducibility of the model [17, 20–24].

Artificial Intelligence in RA

Assessment of RA Development Risk

Currently, the most commonly used method for detecting pre-clinical RA in individuals is by measuring autoantibodies such as anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) or rheumatoid factor (RF), which could be present even years before the symptomatic disease [25]. However, they have a poor positive predictive value [26]. Hence, a reliable predictor of future RA development is yet to be found, and artificial intelligence could assist in this regard. O'Neil et al. [25] designed regression models with serum proteome as input to identify patients who are likely to eventually develop RA (i.e., progressors) among first-degree relatives of those with confirmed disease (i.e., at-risk population). Among ACPA-negative cases, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression recognized progressors using 17 proteins with an accuracy of 100%. However, another model for ACPA-positive individuals was less accurate (accuracy = 86.9%). Among all at-risk individuals, a third model was developed using 23 proteins as variables which demonstrated 91.2% accuracy (area under the curve (AUC) = 0.93) in the validation set in identifying progressors.

Multiple studies have attempted to identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with RA development risk and the epistatic relationships among them. Kruppa et al. [27] used a random-jungle model and identified a 496-SNP panel closely associated with RA (AUC = 0.89). Negi and colleagues [28] also investigated SNPs and found that four SNPs were significantly associated with the disease, with maximum and minimum odds ratios (OR) being 1.42 and 0.86, respectively. One gene in which polymorphisms are associated with RA is PTPN22 [29, 30]. Briggs et al. [31] identified epistatic relations between PTPN22 and several SNPs that could augment the effect of PTPN22 on susceptibility to RA. Epistatic relationships were also probed by Gonzalez-Reico et al. [32], where they evaluated interactions between human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and non-HLA genes using Bayesian LASSO regression.

Jin et al. demonstrated that some eye diseases are associated with RA development in patients aged 50 and above [33]. In their study, cataract and other non-glaucoma eye diseases significantly increased the risk of developing RA, after adjusting for multiple other covariates (ORs = 1.33 and 1.43, respectively).

Table 2 summarizes studies incorporating ML for the assessment of RA development risk [25, 27, 28, 31–36].

Table 2.

Studies incorporating AI for the assessment of RA development risk

| First author | Model | Algorithms applied | No. of data | Type of the primary data | Validation/Test | Objective | Prominent outcomes presented |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gola et al. (2021) [34] | Supervised ML | Model-based MDR, random forest and Elastic Net |

RA = 868 Controls = 1194 |

Omics data | Nested tenfold cross-validation | Disease prediction | Model: Elastic Net, AUC = 0.86 |

| O’Neil et al. (2021) [25] | Supervised ML | LASSO regression |

Total at-risk = 127 ACPA-negative (not progressor) = 47 ACPA-positive (not progressor) = 63 Progressors = 17 |

Omics data | Whole data (for models 1 and 2), dependent test set (for model 3) | To identify RA susceptibility protein markers | Model 3 (validation, n = 34): accuracy = 91.2%, AUC = 0.931 |

| Jin et al. (2021) [33] | Supervised ML | Logistic regression, random forest |

Arthritis = 2272 No arthritis = 6151 |

Clinical and lab data | N/A | To find eye diseases that increase the risk of arthritis development |

Cataract OR = 1.331 (1.057–1.664) Glaucoma OR = 1.155 (0.703–1.805) (but not statistically significant) Other eye diseases OR = 1.428 (1.174–1.730) Gini Index for other eye diseases = 4.22 (higher than cataract and glaucoma) |

| Chin et al. (2018) [35] | Supervised and unsupervised ML | SVM + NMF |

RA = 1007 Controls = 921,192 |

EHR | Tenfold cross-validation | To identify RA risk factors | Best accuracy using 200 risk factors |

| Negi et al. (2013) [28] | Supervised ML | SVM |

Discovery: RA = 706 Controls = 761 Replication: RA = 927 Controls = 1148 |

Omics | Replication set, cross-validation | To identify SNPs associated with RA | Four SNPs were associated with RA upon replication (highest OR = 1.42, lowest OR = 0.86) |

| Kruppa et al. (2012) [27] | Supervised ML | LASSO regression, logistic regression, random jungle |

RA = 707 Controls = 738 |

Omics | Tenfold cross-validation, Dependent test set | To identify associations between SNPs and RA | Model: random jungle (496 SNPs): AUC = 0.8925 (0.8644–0.9206), sensitivity = 80.09% (74.46–84.73%), specificity = 80.48% (75.13–84.91%) |

| Liu et al. (2011) [36] | Supervised ML | Logistic regression, random forest |

NARAC1 (training): RA = 908 Controls = 1260 NARAC2 (validation): RA = 952 Controls = 1760 |

Omics data | Independent test set | To find a set of SNPs to predict RA status |

Using mean decrease in Gini: Training set: 93 out of 696 SNPs selected (error rate = 0.2, sensitivity = 83%, specificity = 75%) Validation: error rate = 0.3, sensitivity = 74%, specificity = 66% Validation cohort used as training: 88 SNPs selected (error rate = 0.28) |

| Briggs et al. (2010) [31] | Supervised ML | Logistic regression |

Extension: RA = 677 Controls = 750 Replication: RA = 947 Controls = 1756 |

Omics | Replication set | To identify epistatic relationships with the PTPN22 gene in RA susceptibility | Out of 449 SNPs found in extension stage, 7 were replicated (highest ROR = 2.42, lowest ROR = 0.51) |

| Gonzalez-Recio et al. (2009) [32] | Supervised ML | Bayesian LASSO regression |

RA = 868 Controls = 1194 |

Omics | N/A | To identify epistatic relationships between HLA and non-HLA SNPs associated with RA | Highest interaction was between rs10484560 (HLA) and rs2476601 (non-HLA) |

ACPA anti-citrullinated protein antibody, AUC area under the curve, EHR electronic health record, LASSO least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, MDR multi-factor dimensionality reduction, ML machine learning, N/A not available, NARAC North American Rheumatoid Arthritis Consortium, NMF non-negative matrix factorization, OR odds ratio, RA rheumatoid arthritis, ROR ratio of odds ratios, SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism, SVM support vector machine

Diagnosis/Early diagnosis

Early diagnosis of RA is of paramount importance as early interventions in the disease course can impede inflammatory destruction of the joints and lead to better outcomes [37].

According to the ACR/EULAR 2010 RA classification criteria, RF, ACPAs (often tested as anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) can be used as biomarkers for diagnosis of RA [38]. Nevertheless, RF and ACPA lack optimal sensitivity [39], while ESR and CRP have limited specificity. The absence of an optimal biomarker with high sensitivity and specificity necessitates the development of novel biomarker panels for early identification of RA [40]. Analysis of omics, i.e., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, glycomics, or metagenomic, using ML approaches enables simultaneous assessment of the association of numerous biomolecules with RA [41, 42]. Incorporating omics data into medical decision-making has several benefits. They are easily acquired from body fluids and are objectively interpreted. Furthermore, their extensiveness provides us with a vast amount of information. Of course, their limitation must also be kept in mind, such as being more complex and expensive.

Moreover, imaging findings, e.g., evidence of synovitis, in combination with clinical data and data derived from sensors, play a critical role in diagnosis, monitoring, and management of RA. Improved data analysis using AI can facilitate early detection of the disease and more efficient use of human resources [38, 43]. Herein, we summarize the applications of ML approaches in the diagnosis of RA using omics, imaging, clinical, and sensor data.

Using omics data in the diagnosis of RA

Several studies developed panels of multiple coding or non-coding ribonucleic acid (RNAs) within the serum or plasma to establish an accurate RA diagnosis using ML approaches. In a recent study, Liu and colleagues assessed gene expression profiles of peripheral blood cells and identified 52 differentially expressed genes in patients with RA. Further protein–protein analysis identified nine hub genes with crucial roles in the development of RA, which are fundamental in immune regulation, namely CFL1, COTL1, ACTG1, PFN1, LCP1, LCK, HLA-E, FYN, and HLA-DRA. The logistic regression and random forest models showed an AUC ≥ 0.97 for the panel of these nine messenger RNAs (mRNAs) in distinguishing RA from healthy samples [44]. In one other investigation of gene expression profile, Pratt et al. showed that a 12-gene transcriptional pattern in peripheral blood cluster of differentiation (CD) 4 + T cells could predict the development of RA in patients with undifferentiated arthritis during a median follow-up of 28 months. While the autoantibody showed a higher sensitivity in the ACPA-positive patients, the newly developed expression signature had a higher sensitivity and specificity in seronegative patients. Notably, the expression of most of these genes was induced by interleukin (IL)-6-mediated STAT3 upregulation. The combination of the 12-gene risk metric with the Leiden prediction rule (AUC = 0.84) outperformed the Leiden prediction rule alone—which is a classic tool for predicting RA progression from undifferentiated arthritis—in seronegative patients (AUC = 0.78), highlighting the clinical significance of these biomarkers [45, 46]. Lastly, recently, non-coding RNAs have garnered considerable research attention as diagnostic biomarkers in RA [47]. Ormseth and colleagues used LASSO variable selection with logistic regression to develop a panel of microRNAs (miRNA) differentiating patients with RA from controls, which resulted in the selection of miR-22-3p, miR-24-3p, miR-96-5p, miR-134-5p, miR-140-3p, and miR-627-5p, all of which were upregulated in patients with RA. The miRNA panel showed an AUC of approximately 0.8 in discriminating patients with RA (seropositive or seronegative) from controls. However, the panel might be an unspecific signature in autoimmune diseases as it could not differentiate RA from systemic lupus erythematosus [48].

Multiple investigations employed proteomic approaches to discover circulating diagnostic biomarkers using mass spectrometry. In such studies, the sample sizes are commonly relatively small, whereas each sample includes a large number of input variables. This atypical data pattern makes decision tree-based algorithms suitable for analysis of the data as they can handle the disproportionate high dimensionality of the input data compared to the number of samples [49]. In such settings, Geurts and colleagues showed that the boosted decision tree outperformed other ML approaches, including SVM and k-nearest neighbors (kNN) [49]. Using this method, several patterns of protein peaks were proposed to differentiate patients with RA from controls and patients with other autoimmune diseases with high sensitivity and specificity [49–51]. The association of the positivity of the serum for the proteomic analysis and intensity of the peaks with levels of anti-CCP antibody highlights the potential role of the patterns of protein peaks in early diagnosis of RA [51]. However, the lack of absolute protein quantification or protein identification is a limitation of these studies, which needs to be addressed by detecting the protein species represented by the peaks on the spectra [50].

Several other diagnostic models have been developed using omics data derived from serum, particularly inflammatory and oxidative stress markers. Analysis of circulatory levels of 38 cytokines using an artificial neural network (ANN) resulted in a model with a sensitivity and specificity of 100% in differentiating patients with RA from controls and patients with osteoarthritis (OA). Nevertheless, the ANN is a Blackbox providing limited information for further clinical inference. Therefore, Heard and colleagues utilized a single decision tree to identify cytokines leading the program to its output. These cytokines included CD40L, transforming growth factor (TGF)-α, epidermal growth factor (EGF), interferon (IFN)-γ, eotaxin, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1α, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), fractalkine, growth-regulated oncogene (GRO), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in a descending order of importance for classification of RA, OA, and controls. Of the mentioned cytokines, eotaxin, G-CSF, IL-1alpha, TGF-α, and TNF-α levels were not statistically different between the groups when analyzed using conventional statistics. This finding highlights the necessity of applying ML algorithms in addition to conventional statistical methods for development of optimal diagnostic panels [52]. 4-hydroxy 2-nonenal (HNE) is another inflammatory marker inducing inflammation in various diseases, including RA (with elevated circulatory levels in patients with RA). A recent study investigated the diagnostic value of autoantibodies against unmodified and HNE-modified peptides in detecting RA in Taiwanese women. The model identified three isotypes of anti-HNE-modified peptides discriminative between RA and controls [53].

Machine learning approaches using metabolomics and glycomics have also shown promising results in the diagnosis of RA. Ahmed and colleagues assessed the diagnostic value of damaged proteins of the joints, including oxidized, nitrated, and glycated proteins and oxidation, nitration, and glycation free adducts released in the circulation by investigating plasma, serum, and synovial samples. Their algorithm, which featured levels of ten damaged amino acids in plasma, hydroxyproline, and anti-CCP antibody status, successfully differentiated early RA from controls and patients with other arthritis. Notably, the levels of damaged amino acids were higher in patients with advanced than early stages [54]. Chocholova et al. trained ML-based diagnostic models using glycomics data with a comparable diagnostic accuracy between ANN and LASSO regression in seropositive patients. Nevertheless, ANN outperformed LASSO regression in detecting seronegative patients in their study [55].

In addition to the circulatory biomarkers, major advancements have been accomplished in diagnosis and patient stratification by assessment of synovial tissue [56]. Long et al. found a 16-gene profile expressed in the synovial samples differentiating patients with RA and OA using supervised ML approaches. This can be particularly useful in seronegative and elderly patients having an inflammatory presentation of OA [57]. Correspondingly, Yeo and colleagues found a panel of ten most informative chemokine genes discriminating patients with established RA from uninflamed controls using ML methods. As shown by their study, synovial biomarkers can assist in the early identification of patients developing RA as well. They found that mRNA levels of chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL)4 and CXCL7 can accurately distinguish early RA from resolving arthritis with higher levels in early RA compared to longer established RA or controls [58].

Furthermore, even within RA patients, ML algorithms can facilitate patient stratification. Orange et al. identified three patterns of synovial gene expression using a clustering algorithm, including a high inflammatory subtype with extensive infiltration of leukocytes, a low inflammatory subtype specified by enrichment in pathways mediated by TGF-β, glycoproteins, and neuronal genes, and a mixed subtype. Subsequently, they developed a model predicting the synovial subtype according to the histological features. Notably, in the high inflammatory subgroup, the severity of pain significantly correlated with the CRP levels. Therefore, they concluded that pain mechanisms might be variable in patients with different synovial subtypes. This finding can result in potential clinical application for patient treatment stratification for pain management [59].

In addition to the above-mentioned omics data, the human microbiome has recently drawn immense research attention. Dysbiosis can be associated with various diseases, including RA. Machine learning-based approaches analyzing metagenomic data are optimal for exploiting the large biological datasets created by the evolving microbiome research [60]. Wu and colleagues used a logistic regression prediction algorithm to improve multiclass classification between patients with RA, type 2 diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, and controls. While no biomarker was specific to type 2 diabetes mellitus and RA, their model had a favorable diagnostic performance with an AUC near 0.95, highlighting the value of microbiome biomarkers in disease diagnostics, especially disease screening, within a large-scale population [61]. However, in a recently published meta-analysis, Volkova and colleagues found specific features in the gut microbiome distinguishing RA from healthy controls and other autoimmune diseases using random forest algorithms. They found that increased levels of Clostridiaceae Clostridium and Lachnospiraceae and reduced abundance of Erysipelotrichaceae were the most distinctive features in RA compared to other autoimmune diseases [62]. In addition to the gut microbiome, assessment of the oral microbiome using ML approaches may also provide promising diagnostic biomarkers [63].

Table 3 illustrates studies incorporating ML for diagnosis of RA using omics data [44, 45, 48–55, 57–59, 61, 62, 64, 65].

Table 3.

Studies incorporating AI for diagnosis of RA using omics data

| First author | Model | Algorithms applied | No. of data | Type of the primary data | Validation/ Test | Objective | Prominent Outcomes presented |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volkova et al. (2021) [62] | Supervised ML | Random forest, XGBoost, ridge regression, and SVM | RA = 371 |

16S rRNA sequencing or shotgun metagenomics or both |

Seven-fold-3-times cross-validation | To identify a microbial signature predictive of autoimmune diseases, including RA, MS, and IBD |

Autoimmunity (at genus level, adults): Random forest: AUC = 0.887, F1 = 0.681, XGBoost: AUC = 0.909, F1 = 0.676, SVM RFE: AUC = 0.826, F1 = 0.636, ridge regression: AUC = 0.778, F1 = 0.603, RA (at species level, adults): Random forest: AUC = 0.879, F1 = 0.664, XGBoost: AUC = 0.847, F1 = 0.650, SVM RFE: AUC = 0.845, F1 = 0.647, ridge regression: AUC = 0.795, F1 = 0.628 Most predictive features for RA: reduced concentration of Desulfovibrionaceae Bilophila, Akkermansia, and Veillonellaceae Dialister and increased levels of Lachnospiraceae Clostridium |

| Jung et al. (2021) [64] | Unsupervised ML | Naïve Bayes classifier |

RA = 152 Controls = 28 |

RNA sequencing (synovial tissue) | Tenfold cross-validation | Classifying RA patients to assess clinical features and treatment response |

Classified patients with RA into three subtypes: C1: neutrophil-enriched signature, C2: fibroblast-enriched signature, C3: prominent immune cells and proinflammatory signatures and associated with presence of ACPA and a better treatment response Key regulatory genes in each subtype were also identified |

| Xiao (2021) [65] | Supervised ML | LASSO regression, SVM, random forest, Xgboost, BPNN, and CNN |

Training: RA = 416 Controls = 318 Test: RA = 10 Controls = 13 |

mRNA expression profiling (blood samples) | Independent test set | To select the genes highly associated with RA | The algorithms were based on pre-defined key genes: BPNN: AUC = 0.99, LASSO regression: AUC = 0.91, SVM: AUC = 0.95 |

| Liu et al. (2021) [44] | Supervised ML | Logistic regression, random forest |

RA = 112 Controls = 53 |

mRNA expression profiling data (serum samples) | Fivefold cross-validation | To assess the diagnostic value of a 9 mRNAs-based panel for diagnosis of RA |

Logistic regression: AUC = 0.97 Random forest: AUC = 0.98 |

| Ormseth et al. (2020) [48] | Supervised ML | Random forest, LASSO, and logistic regression |

Discovery: RA = 167 Controls = 91 Validation: RA = 32 SLE = 12 Controls = 32 |

Plasma samples | Nested cross-validation, Independent test set | To assess the diagnostic value of a panel of miRNAs for diagnosis of RA |

Validation cohort: RA vs. controls: AUC = 0.71 (0.58–0.84), seropositive RA vs. controls: AUC = 0.73 (0.58–0.87), seronegative RA vs. controls: AUC = 0.73 (0.57–0.89) Discovery cohort: RA vs. controls: AUC = 0.79 (0.73–0.86), seropositive RA vs. controls: AUC = 0.79 (0.73–0.86) seronegative RA vs. controls: AUC = 0.84 (0.77–0.91) RA remission vs. controls: AUC = 0.85 (0.78–0.92) |

| Long et al. (2019) [57] | Supervised ML | Random forest, SVM, kNN, naïve Bayes, decision tree |

RA = 53 OA = 41 Controls = 25 |

Genome-wide transcriptional profiles from synovial tissue | Tenfold cross-validation, external test set | To assess the diagnostic value of a 16 gene biomarker panel for diagnosis of RA and differentiating RA from OA | Differentiation of RA and OA: Random forest: accuracy = 0.96, sensitivity = 1.00, specificity = 0.90, SVM: accuracy = 0.96, sensitivity = 1.00, specificity = 0.90, kNN: accuracy = 0.96, sensitivity = 0.92, specificity = 1.00, naïve Bayes: accuracy = 0.96, sensitivity = 0.92, specificity = 1.00, decision tree: accuracy = 0.91, sensitivity = 1.00, specificity = 0.80 |

| Wu et al. (2018) [61] | Supervised ML | Logistic regression, kNN, random forest, SVM, GBDT, SGD, adaptive boosting |

RA = 130 T2D = 170 Liver cirrhosis = 123 Controls = 383 |

Microbiome and phenotype information | Fivefold cross-validation | To develop a multi-class classifier for identification of type of disease using shotgun metagenome sequencing | Logistic regression: AUC = 0.96, F1-score = 0.92, kNN: F1-score = 0.86, random forest: F1-score = 0.83, SVM: F1-score = 0.91, GBDT: F1-score = 0.87, SGD: F1-score = 0.84, adaptive boosting: F1-score = 0.90 |

| Yeo et al. (2016) [58] | Supervised ML | Multivariate analysis |

Uninflamed Controls = 10 Resolving Arthritis = 9 Early RA = 17 Established RA = 12 |

Synovial mRNA expression |

N/A | To differentiate RA in different stages using synovial cytokine production profile | Established RA vs. Uninflamed: AUC = 0.996 Early RA vs. Resolving RA: AUC = 0.764 |

| Pratt et al. (2012) [45] | Supervised ML | SVM |

Training cohort: RA = 47 Controls = 64 Test cohort: Undifferentiated arthritis = 62 |

CD4 T cell transcriptome data and serum samples | Hold out validation | To identify potential biomarkers for early RA using markers expressed by peripheral blood CD4 T cells |

Sensitivity = 0.68% (0.48–0.83), specificity = 0.70 (0.60 to 0.87), PLR = 2.2 (1.2–3.8), NLR = 0.4 (0.2–0.8) Removing ACPA-positive subset: sensitivity = 0.85 (0.58–0.96), specificity = 0.75 (0.59–0.86) |

| Orange et al. (2018) [59] | Supervised & Unsupervised ML | SVM and consensus clustering |

RA = 123 OA = 6 |

RNA sequence and histology data | Leave-one-out cross-validation | To classify patients according to synovial tissue inflammation and predict the classification using histological features |

Consensus clustering: Identification of three distinct synovial subtypes SVM: Prediction of subtypes using histological data: high inflammatory vs. other: AUC = 0.88, low inflammatory vs. other: AUC = 0.71, mixed subtype vs. other: AUC = 0.59 |

| Tsai et al. (2021) [53] | Supervised ML | Decision trees, random forest, SVM |

RA = 60 OA = 35 Controls = 60 |

Levels of specific autoantibodies from serum samples | Ten-fold cross-validation | To identify RA patients using serum levels of anti-unmodified and anti-HNE-modified peptide autoantibodies |

HC vs. RA: random forest: AUC = 0.92, SVM: AUC = 0.82, decision tree: AUC = 0.86 OA vs. RA: random forest: AUC = 0.92, SVM: AUC = 0.88, decision tree: AUC = 0.84 |

| Chocholova et al. (2018) [55] | Supervised DL | ANN, L1-regularized logistic regression |

RA = 47 Controls = 53 |

Immunoassays Serum samples |

Hold-out validation, testing set | To differentiate between healthy people and seropositive/ seronegative RA patients by incorporating glycomics using serum samples |

ANN: Seropositive RA vs. non-RA (using anti-CCP and total RF combined with ELLBA-based RCA glycol profiling): AUC = 0.96, sensitivity = 80.6%, specificity = 100.0%, accuracy = 92.5%, NPV = 89.1, PPV = 100 Seronegative RA vs. non-RA (using RCA ELLBA using adsorbed protein A and serum samples): AUC = 0.86, sensitivity = 43.8%, specificity = 90.6%, accuracy = 79.7%, NPV = 84.2, PPV = 58.3 |

| Ahmed et al. (2016) [54] | Supervised ML | Random forest |

RA = 67 OA = 63 Non-RA inflammatory arthritis = 42 Controls = 53 |

Mass spectrometry (plasma and synovial fluid samples) | Fivefold cross-validation, independent test set | To identify patients with early-stage RA and OA by profiling glycated, oxidized, and nitrated proteins and amino acids in synovial fluid and plasma |

Early arthritis vs. HC: Test set validation: AUC = 0.77 (0.69–0.85), sensitivity = 0.73 (0.56–0.86), specificity = 0.72 (0.62–0.81), NPV = 0.05, PPV = 0.62, PLR = 2.6, NLR = 0.38 Early RA vs. other arthritis: Test set validation: AUC = 0.62 (0.5–0.75), sensitivity = 0.60 (0.42–0.76), specificity = 0.61 (0.46–0.72), NPV = 0.97, PPV = 0.23, PLR = 1.5, NLR = 0.67 |

| Heard et al. (2014) [52] | Supervised DL | ANN and decision tree |

RA = 100 OA = 100 Controls = 100 |

Serum inflammatory proteins (LUMINEX assays) | Hold-out validation, independent testing set | To categorize HC, patients with RA and patients with OA using a panel of inflammatory cytokines expressed in serum samples |

For RA: ANN: (both trained using all (N = 38) proteins and using only differently expressed (N = 12) proteins): specificity = 100%, sensitivity = 100% Multi-decision tree (trained using all (N = 38) proteins): specificity = 100%, sensitivity = 95% |

| Niu et al. (2010) [50] | Supervised ML | Boosted decision tree |

Training set: RA = 22 OAID = 26 Controls = 25 Test set: RA = 21 OAID = 24 Controls = 25 |

Mass spectrometry (serum samples) | Hold-out validation | To identify the serum proteomic pattern for classifying patients with RA and OAID | For RA: accuracy = 85.7%, sensitivity = 85.71%, specificity = 87.76% |

| Geurts et al. (2005) [49] | Supervised ML | Decision tree ensemble methods, kNN, SVM | RA: N = 206 (RA: N = 68, controls: N = 138), | Mass spectrometry (serum samples) | Leave-one-out cross-validation | To identify biomarkers related to a given disease from datasets obtained from mass spectrometry |

For RA: Boosted decision tree: sensitivity = 83.82%, specificity = 94.93% kNN: sensitivity = 82.35%, specificity = 82.61% SVM: sensitivity = 88.24%, specificity = 89.86% |

| de Seny et al. (2005) [51] | Supervised ML | Decision tree boosting |

RA = 34 Other inflammation group = 39 Non-inflammation group = 30 |

Mass spectrometry (serum samples) | Leave-one-out cross-validation | To identify serum protein biomarkers specific for RA |

RA versus controls: Classifying 2 spectra from one patient independently: sensitivity = 85%, specificity = 91% Combining classification of the 2 spectra sensitivity = 94%, specificity = 90% RA versus PsA: Classifying 2 spectra from one patient independently: sensitivity = 94%, specificity = 86% Combining classification of the 2 spectra sensitivity = 97%, specificity = 76% |

ACPA anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies, ANN artificial neural network, AUC area under the curve, BPNN backpropagation neural network, CCP cyclic citrullinated peptide, CNN convolutional neural network, DL deep learning, GBDT gradient boosted decision tree, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, kNN k-nearest neighbors, LASSO least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, ML machine learning, MS multiple sclerosis, NLR negative likelihood ratio, NPV negative predictive value, OA osteoarthritis, PLR positive likelihood ratio, PPV positive predictive value, PsA psoriatic arthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, SGD stochastic gradient descent, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, SVM support vector machine, XGBoost gradient boosting decision tree (eXtreme Gradient Boosting)

Using imaging Data in the Diagnosis of RA

Radiological findings are critical in the diagnosis and staging of RA [66]. Conventional radiography is a commonly available and widely used modality. Multiple models have been developed to diagnose RA using inputs of hand X-ray data [67, 68], such as convolutional neural networks (CNN), with an accuracy as high as near 95% [67]. Compared with conventional radiography and computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound are superior in detecting early soft tissue changes [66]. The characteristic imaging features of RA are synovitis, bone erosions, bone marrow edema, joint space narrowing, joint effusion, and subcortical cysts. Late imaging findings may include subluxation or luxation, scar formation, fibrosis, and bony ankylosis [66]. To the best of our knowledge, AI-based models have been exploited in the detection of synovitis [69–71], bone erosions [72, 73], bone marrow edema [74], and joint space narrowing [75]. However, we did not find investigations on other features, such as subcortical cysts, joint effusion, or late imaging findings.

Machine learning-based algorithms, both supervised and unsupervised, have been developed to detect and quantify synovitis using MRI images [71, 76]. Computer-aided diagnostic approaches have been highly consistent with manual synovitis quantifications in dynamic-contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI, while they can significantly reduce the time spent by the observer reading the image [76, 77]. We did not find any DL-based study assessing synovitis on wrist MRI. Moreover, few studies were designed to classify and quantify synovitis using ultrasound images [70, 78, 79]. In a recent investigation, Wu and colleagues developed a DL-based model assessing the severity of RA by classifying synovial proliferation captured by ultrasound [78].

Several studies used images obtained from different modalities to create models detecting and grading bone lesions. Most studies utilized hand X-ray images to identify erosions [73, 80]. A recent study showed that severity scores acquired from a DL-based model analyzing hand X-ray images could be comparable to the scoring of a human assessor [81]. Artificial intelligence-based models also performed well in detecting joint space narrowing in RA on plain X-rays [75, 80]. However, conventional radiography may underestimate number and size of erosions because of their projectional character [72]. Therefore, utilizing CT images for automatic detection and quantification of bone erosions can facilitate a more accurate assessment of disease activity [72, 82]. Moreover, clustering methods have been useful in detecting and quantifying bone marrow edema, a prominent feature in RA, on wrist MRI [74].

Other than conventional radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI, molecular imaging can also play a key role in diagnosis and management of patients with RA [83]. Nevertheless, we did not find any AI-based investigation of enhancing or analyzing molecular imaging data in RA. In addition to the radiologic modalities, reliable diagnostic models have been developed using hand photographs [84] or a combination of thermal and RGB hand images, demographic data, and hand gripping force [85]. Notably, given the accessibility of acquiring the required data, such algorithms can be used as screening tools for RA [85].

Table 4 provides a summary of the ML and DL studies that used imaging data as input to diagnose patients with RA.

Table 4.

Studies incorporating AI for diagnosis of RA using imaging data

| First author | Model | Algorithms applied | No. of data | Type of the primary data | Validation/ Test | Objective | Prominent Outcomes presented | Comparison with conventional methods if performed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al. (2022) [78] | Supervised DL | DenseNet | RA = 1337 (L0 = 313, L1 = 657, L2 = 178, L3 = 189) | Ultrasound images (the wrist, proximal interphalangeal, and the MCP | Holdout test set | To classify synovial proliferation in ultrasound images of patients with RA |

Synovial proliferation (SP)-no versus SP-yes (grade L0 versus grades L1 and L2 and L3 in OESS): AUC = 0.886 (95% CI 0.836, 0.936), accuracy = 82.1%, sensitivity = 70.0%, specificity = 94.3% Healthy versus Diseased (grades L0 and L1 versus grades L2 and L3): AUC = 0.916 (95% CI 0.883, 0.952), accuracy = 80.4%, sensitivity = 90.8%, specificity = 70.0% |

N/A |

| Alarcon-Paredes et al. (2021) [85] | Supervised ML | A collection of classifiers, including random forest, and wrapper feature selection method |

Training: RA = 100 Controls = 100 Test: RA = 18 Controls = 20 |

Thermal and RGB images recording gripping force + demographic data |

Tenfold cross-validation, independent validation set | To develop an algorithm for diagnosis of RA using easy-to-acquire variables |

RGB images, age, and grip force: random forest accuracy = 0.945, sensitivity = 0.941, specificity = 0.95, AUC = 0.962 Thermal images, age, and grip force: random forest: accuracy = 0.90, sensitivity = 0.888, specificity = 0.912, AUC = 0.954 |

N/A |

| Mate et al. (2021) [67] | Supervised ML | CNN, SVM, ANN |

RA = 160 Controls = 130 |

Hand X-ray | Part of data as test set | To diagnose RA using hand X-ray | Using CNN: accuracy = 94.46%, sensitivity = 0.95, specificity = 0.82 | N/A |

| Ureten et al. (2020) [68] | Supervised DL | CNN |

Testing set: RA = 25 Controls = 20 |

Hand X-ray | Part of data as test set | To diagnose RA using hand X-ray | Inflammatory arthritis: accuracy = 73.33%, sensitivity = 0.6818, specificity = 0.7826, precision = 0.75, error rate = 0.0167 | N/A |

| Reed et al. (2020) [84] | Supervised ML | SVM, random forest, logistic regression, Google's TensorFlow (TF) Inception v3 model for the photographic algorithm |

RA = 117 OA = 56 PsA = 38 OA/RA = 45 OA/PsA = 17 Gout = 7 |

Hand photograph, a 9-part questionnaire, and clinical data | Leave-one-out cross-validation | To establish a diagnosis of hand arthritis using several types of input data |

Differentiating inflammatory arthritis from OA: logistic regression: accuracy = 0.975, PPV = 0.982, sensitivity = 0.986, specificity = 0.937, SVM: accuracy = 0.971, PPV = 0.973%, sensitivity = 0.991%, specificity = 0.905% Differentiating inflammatory arthritis from OA with inclusion of RF, CCP, ESR and CRP results: logistic regression: accuracy = 0.971, PPV = 0.977%, sensitivity = 0.986%, specificity = 0.921%, Differentiating RA from other arthritis: SVM: accuracy = 0.911, PPV = 0.911%, sensitivity = 0.938%, specificity = 0.873%, random forest: accuracy = 0.911, PPV = 0.926%, sensitivity = 0.920%, specificity = 0.898% |

N/A |

| Hirano et al. (2019) [80] | Supervised DL | CNN |

RA = 108 Radiographs = 216 (training = 186, test = 30) |

Hand X-ray | Part of data as validation and test sets | To assess radiographic finger joint destruction in RA |

For joint space narrowing: accuracy = 49.3–65.4% For erosion: accuracy = 70.6–74.1% |

The correlation coefficient between scores by the model and clinicians per image: for joint space narrowing: 0.72–0.88 and for erosion: 0.54–0.75 |

| Rohrbach et al. (2019) [81] | Supervised DL | CNN | Images = 102,265 | Hands and feet X-ray | Hold-out test dataset | Bone erosion scoring | Global accuracy for scoring eroded joints in the test set = 65.8% | Yes, the agreement between the CNN's predictions and the human scores was comparable with the agreement between different human scorers |

| Aizenberg et al. (2018) [74] | Supervised ML | atlas-based segmentation, fuzzy C-means clustering |

Training = 56 Validation = 485 |

Wrist MRI (T1-Gd scans) | Leave-one-out cross-validation | Automatic quantification of bone marrow edema in early arthritis |

Accuracy of atlas-based segmentation compared to manual segmentation: Lowest recall in pisiform (mean ± SD) = 0.58 ± 0.09 Highest recall in capitate (mean ± SD) = 0.82 ± 0.03 |

Yes, correlation with visual BME scores: r = 0.83, p < 0.dee |

| Murakami et al. (2017) [73] | Supervised DL | MSGVF Snakes algorithm and DCNN classifier |

Training: RA = 90 Controls = 39 Test: RA = 30 |

Hand X-ray | Threefold cross-validation, Independent testing dataset | identification of bone erosions | True-positive rate (sensitivity) = 80.5%, False-positive rate = 0.84% | N/A |

| Czaplicka et al. (2015) [76] | Supervised ML | Automatic segmentation | RA = 32 | Pre-and post-contrast wrist MRI | N/A | To determine inflamed synovial membrane volume | Following segmentation of wrist bones and automatic quantification of volume of synovitis: Correlation between the total RAMRIS score and the total volume of synovitis (automated segmentation): rs = 0.87, which is as same as manual segmentation | Yes: Manual versus automated segmentation: Pearson’s coefficient of correlation = 0.82, rs = 0.70) |

| Töpfer et al. (2014) [72] | Supervised DL | 3D segmentation | N = 18 | HR-pQCT of the second to fourth metacarpophalangeal joints | N/A | Quantification of bone erosions |

for erosions with volumes > 10 mm3: Intraoperator precision error = 3.02%/0.92 mm3, Interoperator precision error = 5.99%/1.53 mm3 for smaller erosions: Intraoperator precision error = 6.11%/0.32 mm3, Interoperator precision error = 8.27%/0.35 mm3 Intraoperator and interoperator precision error for erosions segmented fully automatically < manually edited erosions |

Yes, The correlation between manual measurements and segmentation volumes: r = 0.61 |

| Boesen et al. (2012) [77] | N/A | DYNAMIKA software | N = 54 | DCE MRI of the wrist | N/A | To assess the correlation of DCE MRI analyzed by a computer-aided approach and the scores of the RAMRIS system | Computed aided analysis of DCE MRI correlated with RAMRIS synovitis and BME with a shorter performance time for the observer | The time the observer spent was compared between the computer-aided approach and RAMRIS synovitis and BME |

| Langs et al. (2008) [75] | Supervised ML | Automated segmentation using LLM and ASM |

Set A = 40 radiographs Set B = 17 radiographs |

Hand X-ray | Cross-validation | To measure joint space widths and detect erosions on the bone contour |

Joint space widths measurement: coefficient of variation = 2–7% for repeated measurements AUC for erosion detection = 0.89 |

Yes, joint space widths and erosions, detected by a radiologist was the standard of reference |

| Tripoliti et al. (2007) [71] | Unsupervised ML | Fuzzy C-means algorithm | N = 25 patients (Both in baseline and 1-year follow-up = 17 comprising 504 images [300 (baseline) and 204 (follow-up)] | Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI | N/A | Segmentation and quantification of inflammatory tissue of the hand | Performance in identifying regions compared with physicians: sensitivity = 97.7%, PPV = 83.35% | Yes |

| Scheel et al. (2002) [69] | Supervised ML | Neural network |

RA = 22 (72 joints) Controls = 8 (64 joints) |

Laser imaging data | N/A | To assess proximal finger joint inflammation using laser-based imaging technique | Accuracy = 83%, sensitivity = 80%, specificity = 89% (in detecting inflammatory changes) | N/A |

ANN artificial neural network, ASM active shape models, AUC area under the curve, BME bone marrow edema, CCP cyclic citrullinated peptide, CNN convolutional neural network, CRP C-reactive protein, CT computed tomography, DCE dynamic contrast-enhanced, DL deep learning, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, HR-pQCT high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT, LLM local linear mapping, ML machine learning, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, MSGVF multiscale gradient vector flow, OA osteoarthritis, PPV positive predictive value, PsA psoriatic arthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, RAMRIS rheumatoid arthritis MRI scoring system, RF rheumatoid factor, SVM support vector machine

Using Clinical and Sensor Data for Diagnosis of RA

Several models have been developed for the diagnosis of RA using clinical data (Table 5) [86–88]. Singh and colleagues showed that a fuzzy inference system could have an acceptable diagnostic performance when fed with data on clinical symptoms [87]. In a novel approach, Fukae et al. converted clinical information to two-dimensional array images and used CNN (AlexNet) to distinguish patients with RA. The results of their algorithm showed a favorable agreement with the diagnosis made by three rheumatologists [88].

Table 5.

Studies incorporating AI for diagnosis of RA using clinical or sensors data

| First author | Model | Algorithms applied | No. of data | Type of the primary data | Validation/ Test | Objective | Prominent Outcomes presented |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fukae et al. (2020) [88] | Supervised ML | CNN (AlexNet and Resnet-18) |

Training: RA = 225 Controls = 785 Test: RA = 10 Controls = 40 |

Clinical data converted to two-dimensional array images | Independent testing dataset | To diagnose RA using clinical data converted to two-dimensional array images |

AlexNet: accuracy = 98%, precision = 91%, recall = 100% |

| Sharon et al. (2019) [90] | Unsupervised ML | kNN and random forest |

Dataset 1 = 40 Dataset 2 = 310 |

Microscopic features of lymphocytes captured by electronic image sensor | Hold-out and tenfold cross-validation | To classify RA patients using microscopic images of lymphocytes |

Tenfold cross-validation method: Random Subspace classifier: random forest: precision = 97.6, recall = 97.5, F-measure = 97.55, AUC = 100.0, accuracy rate = 97.5, kNN: precision = 97.6, recall = 97.5, F-measure = 97.55, AUC = 99.7, accuracy rate = 97.5; bagging classifier: random forest: precision = 89.8, recall = 90.0, F-measure = 89.9, AUC = 97.7, accuracy rate = 90.0, kNN: precision = 91.1, recall = 90.0, F-measure = 90.54, AUC = 94.7, accuracy rate = 90.0 Hold-out method: Random subspace classifier: random forest: precision = 83.3, recall = 75.0, F-measure = 78.93, AUC = 100, accuracy rate = 75.0, kNN: precision = 68.8, recall = 66.7, F-measure = 67.73, AUC = 87.5 accuracy rate = 66.67; bagging classifier: random forest: precision = 86.6, recall = 87.0, F-measure = 86.8, AUC = 97.1, accuracy rate = 86.96, kNN: precision = 81.0, recall = 71.4, F-measure = 75.9, AUC = 95.8, accuracy rate = 71.43 |

| Bardhan et al. (2019) [91] | Unsupervised ML | K-means, fuzzy C-means, Otsu, single and multi-seeded region growing, SVM |

RA = 60 Controls = 50 |

Knee joint thermograms | Three-fold cross-validation | To identify arthritis and RA using knee thermograms | RA classification rate obtained with accuracy-based feature selection = 73% |

| Singh et al. (2012) [87] | Supervised ML | Fuzzy inference system | N = 150 | Clinical symptoms | N/A | N/A | The performance of the diagnostic system for arthritis was acceptable |

| Wyns et al. (2004) [86] | Supervised & Unsupervised DL | Kohonen neural network (includes self-organizing maps) |

RA = 51 SpA = 43 Other = 26 No definite diagnosis = 40 |

Clinical data | Hold-out test set | Prediction of diagnosis in patients with early arthritis | Accuracy = 62.3%, 65.3% (without undetermined samples) |

AUC area under the curve, CNN convolutional neural network, DL deep learning, kNN k-nearest neighbors, ML machine learning, RA rheumatoid arthritis, SVM support vector machine

Sensor data, which are rich datasets for disease diagnosis and monitoring, are acquired using technologies such as wearable devices, thermography sensors, and image sensors [89–91]. In a recent study, ML algorithms using features extracted from lymphocyte images generated by an electronic image sensor were highly accurate for RA classification, with accuracy rates as high as 97.5%. Notably, electronic image sensors convert optical images into electronic data [90]. Furthermore, thermograms are noninvasive methods used to assess joint inflammation in RA [92]. Bardhan et al. developed a two-stage classification algorithm correctly labeling nearly three-fourths of the knee thermograph scans (stage one was detection of arthritis-affected knees, and stage two was detection of knees affected by RA) [91].

Phenotype identification using EHRs

In the context of EHRs, "phenotype" is a clinical condition or characteristic that can be obtained via an automated method from EHR system or clinical data repository using a specific group of data elements and logical expressions. Electronic health records contain a comprehensive pool of data, which can be widely used in clinical and translational research. Nevertheless, due to the large amount of data, the manual review and extraction can be extremely time-consuming and inefficient. Both rule-based and ML (supervised or unsupervised) models have been used to identify disease status using EHRs. Phenotype identification algorithms usually combine various sources of information, e.g., billing codes, laboratory data, medication exposures, and NLP, to make accurate predictions [93, 94].

Several models have been developed to identify patients with RA efficiently from EHRs using NLP and ML (Table 6) [95–109]. Support vector machine is one of the most commonly used algorithms for phenotype identification. In 2010, Carrol and colleagues developed an SVM model with a favorable performance (AUC > 0.90) in predicting RA disease status using naïve and refined data (i.e., naïve data curated to only include RA-related items). Notably, the SVM model had higher patient identification precision than a deterministic model [108]. Importantly, given the changes in EHR systems, addition of novel DMARDs, and updates of the ICD codes, the validity of such phenotype identification algorithms should be routinely investigated with contemporary data. A recent assessment of the performance of Carrol et al.'s model using 2017 data showed that even though the diagnostic codes and medications have changed from 2010, the model still performed robustly and outperformed rule-based algorithms. Nevertheless, updating the model using ICD-10 codes resulted in a slight improvement in the sensitivity of the model [100]. In a recent study, Maarseveen et al. found that between naïve Bayes, SVM, gradient boosting, random forest, decision tree, neural networks, and a random classifier, SVM outperformed others in disease identification using EHR [99]. They showed that the performance of the proposed model was similar to a manual chart review using the 1987 and 2010 RA classification criteria [110].

Table 6.

Studies incorporating AI for phenotyping RA using EHR

| First author | Model | Algorithms applied | No. of data | Type of the primary data | Validation/ Test | Objective | Prominent Outcomes presented |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cai et al. (2021) [95] | Supervised ML | Random forest, logistic regression | N = 4001 | EHR | Independent testing dataset | Efficient identification of eligible patients for clinical trial recruitment |

At the tertiary hospital: sensitivity = 98%, PPV = 21.8% At the community hospital: sensitivity = 98%, PPV = 24.3% The model resulted in reduction of ineligible patients from chart review by 40.5% at the tertiary care center and by 57.0% at the community hospital |

| Fernández-Gutiérrez et al. (2021) [96] | Supervised ML | Decision trees | N = 9657 (RA = 1484) | EHR | Tenfold cross-validation, independent testing dataset | To identify patients with a condition from EHR | Accuracy = 86.19, sensitivity = 72.2, specificity = 92.64, PPV = 81.92, NPV = 87.83 |

| Ferte et al. (2021) [97] | Unsupervised ML | SAFE algorithm, random forest, logistic regression |

Training = 9102 Test = 2359 |

EHR | Cross validation | Extending PheNorm [102] by combining diagnosis codes and medical concepts | For RA: AUC = 0.943 (0.940–0.945), AUPRC = 0.754 (0.744–0.763) |

| Maarseveen et al. (2021) [98] | Supervised ML | SVM |

Training = 2000 Test = 1000 |

EHR | Independent testing dataset | Extending PheNorm [102] by combining diagnosis codes and medical concepts | sensitivity = 0.85, specificity = 0.99, PPV = 0.86, NPV = 0.99 |

| Maarseveen et al. (2020) [99] | Supervised ML | SVM, gradient boosting, random forest, decision tree, neural networks, and a random classifier | N = 30,000 | EHR | Tenfold cross-validation | To identify patients with RA from EHR | SVM: F1 score = 0.81, PPV = 0.94, NPV = 0.97, sensitivity = 0.71, specificity = 1.00 |

| Huang et al. (2020) [100] | Supervised ML | SVM | EMR | Independent validation dataset | To evaluate the performance of a phenotyping algorithm trained by a previous version of diagnostic codes and effect of updating diagnostic codes |

In all patients with RA: Previous model: AUC = 0.93, PPV = 91%, NPV = 0.87, specificity = 0.95, sensitivity = 0.76 Updated version: AUC = 0.94, PPV = 91%, NPV = 0.88, specificity = 0.95, sensitivity = 0.77 |

|

| Ning et al. (2019) [101] | Supervised & Unsupervised ML | SEmantics-Driven Feature Extraction (SEDFE), adaptive elastic-net penalized logistic regression, PheNorm | Training = 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 | EHR | Manual validation | To develop a feature extraction model independent from the EHR and classify rheumatoid arthritis, CAD, CD, UC, and pediatric PAH |

For RA: Supervised (with SEDFE and 300 labels): AUC = 0.940 PheNorm (with SEDFE): AUC = 0.944 |

| Yu et al. (2018) [102] | Supervised & Unsupervised ML | PheNorm, adaptive elastic-net penalized logistic regression, XPRESS algorithms, Anchor algorithms |

Training = 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 For XPRESS: N = 750 (except for CAD), N = 741 (for CAD) |

EHR | Manual validation, fivefold cross-validation | To classify rheumatoid arthritis, CAD, CD, and UC using unlabeled data |

For RA: PheNormvote (with SAFE): AUC = 0.937 Supervised (with SAFE and 300 labels): AUC = 0.935 XPRESS algorithms: AUC = 0.896 Anchor algorithms: AUC = 0.890 |

| Gronsbell et al. (2019) [103] | Supervised & Unsupervised ML | Unsupervised clustering, followed by regularized regression on | N = 435 | EMR | Independent validation dataset | To identify disease status and predict the most informative features using unlabeled data | AUC = 0.928 |

| Gronsbell et al. (2018) [104] | Semi-supervised ML | Semi-supervised approach | N = 44,014 (Labeled = 500, Unlabeled = 43,514) | EMR | Tenfold cross-validation | To develop a semi-supervised phenotyping algorithm | For RA: AUC = 94.93 |

| Zhou et al. (2016) [105] | Supervised ML | Random forest and C5.0 decision tree |

Two data sets: N= 5208 and N = 475,580 |

EHR | Two independent testing datasets | To accurately and rapidly identify the most informative predictors for classification of RA in primary care EHR in a cost-effective manner |

Using the Cardiff-Cellma population with a prevalence of 27% for RA: PPV = 85.6%, specificity = 94.6%, sensitivity = 86.2% and overall accuracy = 92.29% Using the primary care population: in the worst-case scenario: PPV = 30.9%, specificity = 99%, sensitivity 83% = in the best-case scenario: PPV = 91.3%, specificity = 99.9%, and sensitivity 94% |

| Lin et al. (2015) [106] | Supervised ML | NLP and classification rules |

Case = 600 Controls = 430 |

EMR | Tenfold cross-validation, independent test set | To identify RA patients with methotrexate-induced liver toxicity | F1-score = 0.847, Precision = 0.8, Recall = 0.899 |

| Chen et al. (2013) [107] | Supervised ML | Active learning and SVM |

RA = 185 Controls = 191 |

EHR | Five-fold cross-validation | Phenotype identification using active learning to reduce the number of required annotated samples | AUC > 0.95 |

| Carrol et al. (2011) [108] | Supervised ML | SVM | N = 376 | EHR | Ten-fold cross-validation | To predict RA disease status | Naïve dataset: Precision = 93.3 ± 0.5, Recall = 79.7 ± 5.2, F measure = 85.1 ± 3.7, AUC = 94.2 ± 1.3; Refined dataset: Precision = 93.3 ± 0.5, Recall = 85.8 ± 5.7, F measure = 88.6 ± 4.0, AUC = 96.6 ± 1.1 |

| Liao et al. (2010) [109] | Supervised ML | Penalized logistic regression with adaptive LASSO procedure |

Training: RA = 96 Controls = 404 Validation: NN = 400 |

EMR | Threefold cross-validation, hold-out test set | To classify RA and non-RA cases |

Complete algorithm: PPV = 94% (95% CI 91–96%) sensitivity = 63% (95%CI 51–75%) |

AUC area under the curve, CAD coronary artery disease, CD Crohn's disease, EHR electronic health record, EMR electronic medical record, LASSO least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, ML machine learning, NLP natural language processing, NPV negative predictive value, PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension, PPV positive predictive value, RA rheumatoid arthritis, SVM support vector machine, UC ulcerative colitis

Several other supervised ML models have been developed for phenotype identification. Zhou and colleagues applied random forests algorithm and proposed a model identifying the most informative predictors of RA status using a large pool of data from patients in primary and secondary care settings, with an overall accuracy of 92.3%, which was comparable with methods derived from expert clinical opinion [105].

Not only can ML models facilitate disease status prediction, but they also could aid in stratification of patients. For instance, Lin et al. developed a classification algorithm to predict cases with MTX-induced liver toxicity. They found that incorporating temporality, i.e., the temporal relation between the presence of liver toxicity events and receiving MTX, can improve the performance of the model [106].

In a novel approach, Cai et al. developed a supervised model to facilitate participant selection for clinical trials by providing an alternative solution for the costly and time-consuming process of eligibility screening and chart review. They combined random forest and logistic LASSO regression to produce a model identifying potentially eligible patients from EHRs for an RA clinical trial. Compared with two rule-based systems, the AI algorithm had a better positive predictive value than one and a better sensitivity than the other; therefore, creating a balance between including and excluding too many patients for manual review [95].

Requirement of a large number of labeled data for training the supervised models is a major challenge in their application for phenotype identification. The quantity of needed annotated samples can be reduced by using semi-supervised and unsupervised models [101, 102]. Semi-supervised models usually use a small-sized labeled dataset and also a large-sized unlabeled dataset to classify data. Few semi-supervised models have been created for phenotype identification using EHRs. Gronsbell and colleagues developed a semi-supervised model that was validated with real data from patients with RA and multiple sclerosis (MS) with a performance comparable to the supervised methods [104]. Moreover, Chen et al. combined SVM and active learning, a form of semi-supervised learning method, and developed a model that outperformed passive learning and reduced the number of the required annotated samples by approximately two-thirds [107]. PheNorm is an unsupervised phenotyping algorithm that has been validated using four phenotypes, namely coronary artery disease, RA, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis, with an accuracy comparable to that of supervised models [102]. Lastly, Gronsbell et al. developed a two-step model, with the first step being an unsupervised clustering method followed by a regularized regression as the second step using unlabeled observations to identify the most informative features from text fields available in the entire EHR. Their model showed a favorable performance (AUC = 0.93) with improved efficiency by reducing the number of labels required [103].

Importantly, the potential of EHRs can be further unraveled by enhancing the performance of the models through developing more complex networks incorporating DL and ANN [111, 112]. Algorithms with high performance can ultimately supersede ICD billing codes, which have the limitation of considerable error rates due to inconsistent terminology [113].

Predicting Treatment Response

Methotrexate is generally the initial DMARD choice for RA. If MTX fails to suppress the disease (which is the case in half of MTX monotherapy patients [114]), the treatment is stepped-up, and other anti-inflammatory drugs are administered, which are usually more expensive [115]. However, treatment failure still persists in some patients on second- or third-line medications, which can only be overcome by trial and error. Hence, a precision medicine treatment approach (also known as personalized or individualized medicine) based on each patient's biological profile could reduce treatment irresponsiveness and its consequences for both the patient and the healthcare system. The data used for choosing the proper treatment plan for a patient could range from simple variables, such as sex and age, to complex data, such as proteomics and transcriptomics.

Patients' demographic and clinical information are generally easily accessible. Such availability of vast amounts of input can result in accurate precision medicine algorithms. Machine learning algorithms have been shown to be able to predict response to MTX with AUCs as high as 0.84 using demographic and clinical data, such as past medical history and laboratory measures [116, 117]. Patients who do not respond to initial treatment should be stepped-up to more powerful medications. Morid et al. [118] evaluated multiple supervised and semi-supervised ML techniques to find the most accurate one to forecast a need for treatment step-up within 1 year among 120,237 patients. One-class SVM showed the best performance with a sensitivity and specificity of 89% and 83%, respectively. Despite the step-up therapy and trying several regimens, response failure persists in some patients (i.e., difficult-to-treat patients) [119]. An extreme gradient boosting algorithm [119] was able to identify these patients with a comparatively high accuracy (AUC = 0.73, sensitivity = 79%, specificity = 50%).

Omics are valuable input sources for predicting treatment response and vary greatly between patients due to different genetic materials and disease molecular basis. Artacho et al. created a random forest model that could identify MTX responders using gut microbiome data with an AUC of 0.84 [114]. When only patients with high (≥ 80%) or low (≤ 20%) chances of response were taken into account, the AUC of the algorithm increased to 0.94. The algorithm did not select pharmacogenetic predictors when provided as input, demonstrating a close relationship between gut microbiota and treatment response [114]. In another study, Plant et al. [120] incorporated transcriptomics and were able to predict MTX response among patients in early treatment stages with an AUC of 0.78. Not all studies yielded such favorable results, and AUCs for predicting MTX response reached as low as 0.61 [115].

Utilizing omics data seems more beneficial in predicting response to second- or third-line biological DMARDs (bDMARDs) than MTX [121, 122]. For instance, an SVM algorithm recognized patients responding to infliximab with an AUC of 0.92 using genomics data [122]. Some studies fed clinical data (e.g., lab results and disease activity measurements) in addition to omics, to their algorithms [123–125] and produced treatment response prediction AUCs as high as 0.83 [126], although the results were fairly heterogeneous.

Imaging data can also be employed in models predicting response to treatment. Kato et al. [127] developed a scoring system based on severity of synovitis, tenosynovitis, and enthesitis on ultrasound images in patients with RA and spondyloarthritis, assessing treatment response. An unsupervised random forest, in addition to uniform manifold approximation and a projection algorithm, was implemented, which divided patients into two clusters with significantly different responses to treatment as measured by the American College of Rheumatology 20, 50, and 70 (ACR20/50/70) criteria.

However, several shortcomings need to be acknowledged in studies applying AI to predict response to treatment. The variety of evaluation methods in determining treatment response makes the comparison of the results between different studies difficult and inaccurate. The EULAR criteria [128] was the most commonly used measure of response, which takes disease activity scores, ESR, and patient's global assessment into account (several variations exist). However, some studies used other definitions for treatment responsiveness, such as the continuation of MTX administration [117] and dose adjustments [129]. Furthermore, most studies are performed on MTX, and few have evaluated treatment outcomes using other RA treatments, especially non-biological DMARDs. Identifying patients for whom non-biological DMARDs are safe and effective substitutes using AI algorithms can be immensely helpful considering the higher cost of bDMARDs and their unavailability to many patients [130].

Table 7 lists studies incorporating ML for predicting treatment response in RA [114–127, 129, 131–134].

Table 7.

Studies incorporating AI for assessment of treatment response in RA

| First author | Model | Algorithms applied | No. of data | Type of the primary data | Validation/Test | Objective | Prominent outcomes presented |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lim et al. (2022) [131] | Supervised ML | Neural networks, SVM, logistic regression, elastic nets, random forest, boosted trees |

Training = 279 Test = 70 |

Demographic, clinical, lab, and omics data | Five-fold cross-validation, hold-out test set |

To predict response to MTX Criteria: DAS28 |

100 features (95 genetic), Model: boosted trees, AUC = 0.828, sensitivity = 0.6875, specificity = 0.8684 |

| Amin Shipa et al. (2021) [116] | Supervised ML | Logistic regression, LASSO logistic regression, SVM, naïve bayes, random forest, bagging, decision single tree, gradient boosting |

Training = 655 (358 responders) Validation = 225 (130 responders) |

Demographic, clinical, and lab data | Independent test set |

To predict response to MTX Criteria: DAS28-ESR ≤ 3.2 at 6 months |

Model: SVM, accuracy = 86%, AUC = 0.84 |

| Artacho et al. (2021) [114] | Supervised ML | Random forest |

Training = 26 (10 responders) Validation 1 = 21 Validation 2 (RA patients not on MTX) = 20 |

Gut microbiome | Test set |

To predict response to MTX in patients with new-onset RA Criteria: 1.8 DAS28 improvement by month 4 with no additional biologic drug |

AUC = 0.84, True negative rate = 83.3%, True positive rate = 78% AUC = 0.94 (for patients with high (≥ 80%) or low (≤ 20%) chance of responding) |

| Gosselt et al. (2021) [125] | Supervised ML | Logistic regression, LASSO regression, random forest, extreme gradient boosting |

Training = 249 (125 responders) Test = 106 (53 responders) |

Demographic, clinical, and genotype data | Tenfold cross-validation, hold-out test set |

To predict response to MTX Criteria: DAS28 ≤ 3.2 at 3 months |

Model: logistic regression, AUC = 0.77 (0.68–0.86), sensitivity = 81% specificity = 60%, accuracy = 71%, PPV = 67%, NPV = 76% |

| Jung et al. (2021) [64] | Unsupervised ML | Naïve Bayes | N = 152 | Omics data | N/A | To predict treatment response based on synovial tissue subtype |

Classification yielded 3 groups: C1: 17.6% response to infliximab C2: 40% response to triple DMARDs and 29.4% response to infliximab C3: 77.8% response to triple DMARDs and 63.6% response to infliximab |

| Kato et al. (2021) [127] | Unsupervised ML | Random forest + uniform manifold approximation and projection |

N = 38 [RA (26) and spondyloarthritis (12)] ACR20 = 26 ACR50 = 21 ACR70 = 17 |

Ultrasound imaging | N/A |

To predict response to MTX at 12 weeks Criteria: ACR20/50/70% |

Significantly more ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 in cluster group 1 (p = 0.007, 0.034, and 0.016, respectively) |

| Koo et al. (2021) [132] | Supervised ML | LASSO linear regression, ridge linear regression, SVM, random forest, extreme gradient boosting |

N = 1397 (564 responders) TNF inhibitors = 793 (252 responders) Non-TNF Inhibitors = 504 (312 responders) Adalimumab = 289 (91 responders) Etanercept = 220 (75 responders) Golimumab = 122 (41 responders) Infliximab = 162 (45 responders) Abatacept = 194 (62 responders) Tocilizumab = 410 (250 responders) |

Demographic, clinical, and lab data | Five-fold cross-validation, hold-out test set |

To predict response to bDMARDs Criteria: DAS28-ESR ≤ 2.6 |

All bDMARDs → Model: Ridge AUC = 0.619, accuracy = 61.5%, sensitivity = 29.6%, specificity = 83.1% TNF inhibitors → Model: Ridge AUC = 0.655, accuracy = 70.0%, sensitivity = 21.3%, specificity = 92.6% Non-TNF inhibitors → Model: Ridge AUC = 0.607, accuracy = 57.8%, sensitivity = 64.5%, specificity = 51.7% Adalimumab → Model: Ridge AUC = 0.688, accuracy = 69.8%, sensitivity = 29.6%, specificity = 88.1% Etanercept → Model: Ridge, random forest AUC = 0.656, accuracy = 67.2%, 66.2%, sensitivity = 36.4%, 0%, specificity = 83.7%, 100% Golimumab→ Model: Ridge AUC = 0.694, accuracy = 63.9%, sensitivity = 41.7%, specificity = 79.2% Infliximab→ Model: Ridge AUC = 0.626, accuracy = 70.8%, sensitivity = 23.1%, specificity = 88.6% Abatacept→ Model: Ridge AUC = 0.679, accuracy = 68.4%, sensitivity = 30.6%, specificity = 84.6% Tocilizumab → Model: SVM AUC = 0.556, accuracy = 61.0%, sensitivity = 80.0%, specificity = 22.9% |

| Luque-Tevar et al. (2021) [126] | Supervised ML | LASSO regression, ridge regression |

Training = 74 (responders = 52) Validation = 25 (responders = 14) |

Clinical, lab, and omics data | Independent test set |

To predict response to TNF inhibitors Criteria: EULAR |

Model: LASSO regression (mixed clinical and molecular parameters), AUC = 0.83 |

| Maciejewski et al. (2021) [115] | Supervised ML | Linear regression, random forest, SVM with kernel, LASSO/ridge regression | N = 100 (responders = 50) | Omics data | Five-fold cross-validation |

To predict response to MTX Criteria: EULAR |

Model: LASSO/ridge regression, AUC = 0.61 ± 0.02 |