Abstract

Objective

To examine the associations of substance fed and mode of breast milk delivery with occurrence of otitis media and diarrhea in the first year of life.

Study design

At 12 months postpartum, women (n = 813; 62% response) completed a questionnaire that assessed sociodemographics, infant occurrence of otitis media and diarrhea, and the timing of starting/stopping feeding at the breast, expressed milk, and formula. Women who intended to “bottle feed” exclusively were not recruited. Logistic and negative binomial regressions were conducted in the full sample (n = 491) and no-formula (n = 106) and bottle-only (n = 49) subsamples.

Results

Longer duration of expressed milk feeding was associated with increased odds of experiencing otitis media (6-month OR [OR6-month] 2.15, 95% CI 1.01-4.55) in the no-formula subsample. Longer durations of breast milk feeding (OR6-month 0.70, 95% CI 0.54-0.92; 6-month incidence rate ratio [IRR6-month] 0.74, 95% CI 0.63-0.91), and feeding at the breast (OR6-month 0.70, 95% CI 0.54-0.89; IRR6-month 0.74, 95% CI 0.63-0.88) were associated with less diarrhea, and longer formula feeding duration was associated with increased risk of diarrhea (IRR6-month 1.34, 95% CI 1.13-1.54) in the full sample.

Conclusion

Substance fed and mode of breast milk delivery have different contributions to infant health depending on the health outcome of interest. Feeding at the breast may be advantageous compared with expressed milk feeding for reducing the risk of otitis media, and breast milk feeding compared with formula may reduce the risk of diarrhea.

Infant feeding practices have quietly but radically changed in developed countries in the past 2 decades. In the early 1990s, 38% of infants were fed expressed milk, compared with 69%-85% in more recent years.1–3 Many infants are exposed to multiple feeding practices, resulting in different combinations of substances fed (breast milk vs formula) and modes of breast milk delivery (at the breast vs bottle) over time.3 In the first 3 postnatal months alone, 54% of infants are fed a combination of substances and/or modes, yet few studies distinguish the role of the substance fed from the mode of breast milk delivery to evaluate their relative associations with child health outcomes.4,5

Prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding has been associated with improved infant immunologic status, including reduced otitis media and gastrointestinal illness.6–8 The bioactive components of breast milk, such as secretory IgA and IgG, play a role in supporting the developing immune system to fight infections.9,10 The composition of milk, however, can be altered by collection, freezing, storage, and thawing practices. Storing breast milk for later use causes cell death and cytotoxicity, and certain thawing and heating techniques are associated with a significant decrease in these protective immunoglobulins.11–15 The bioactive components of milk fed at the breast may, therefore, differ from those in expressed milk. Thus, feeding at the breast may provide greater protection against infections.

The goal of this study was to examine the associations of substance and mode of infant feeding with otitis media and diarrhea in the first postnatal year. To be able to compare with the current literature, the associations between breast milk (inclusive of feeding at the breast and expressed milk feedings) and child health were examined. We also sought to compare feeding at the breast vs expressed milk feeding and expressed milk feeding vs formula feeding.

Methods

A roster was assembled of all English-speaking women ≥18 years of age who delivered a singleton, liveborn infant at >24 weeks’ gestation at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center during 5 months in 2011 (n = 1244). The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center operates a large delivery service for both high- and low-risk obstetric patients in the Columbus, Ohio area. Women whose medical record indicated their intention to “bottle feed” their infant exclusively (n = 303), women lacking valid contact information (n = 111), prisoners (n = 11), and infant deaths (n = 6) were not recruited.

At 12 months postpartum, a questionnaire was mailed to eligible women (n = 813) to assess sociodemographics, infant feeding practices, and the outcomes of interest (otitis media and diarrhea). Participants received a $10 incentive. This study was reviewed and approved by The Ohio State University Biomedical Institutional Research Board.

Maternal age and parity (primiparous vs multiparous) were obtained from the obstetric record; information about receipt of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) benefits during pregnancy or postpartum (yes/no), maternal postpartum employment or school enrollment (>20 hours/week by 6 months postpartum vs <20 hours/week or >20 hours/week after 6 months postpartum), maternal education (college or postgraduate vs less), relationship status (married or living with partner vs single, not living with partner, separated, or divorced), perceived financial difficulty (just getting by, difficulty, or great difficulty vs easily or very easily able to make ends meet), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white vs African American/black, Hispanic, or other and multiple races), child sex, and childcare attendance outside the home (yes/no) was obtained from the questionnaire. The questionnaire asked mothers: “How many times has a doctor said that your child had an ear infection since he/she was born?” and “How many times has your child had diarrhea (increase in the number of bowel movements) since birth?” These questions formed both binary (ever/never) and count (number of episodes) variables for each child for analysis.

The timing of starting and stopping feeding at the breast, expressed milk feeding, and formula feeding was asked on the questionnaire. Separate variables were calculated for breast milk feeding (inclusive of feeding at the breast and expressed milk), feeding at the breast, expressed milk feeding, and formula feeding. Feeding variables represent the duration of each feeding practice regardless of other feeding practices used during that time.

Statistical Analyses

We first examined associations between infant feeding and child health in the full sample of infants who were fed at the breast, expressed milk, and/or formula in the first postnatal year. Exploratory analyses were carried out in subsamples of infants who were fed no-formula in the first 6 months (ie, infants could have been fed any combination of at the breast and/or expressed milk) and from a bottle-only in first postnatal year (ie, infants could have been fed any combination of expressed milk and/or formula). The subsample analyses were important to reduce confounding by measured and unmeasured factors that influence feeding practice decisions.

Univariate statistics described the sample and χ2, t, and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare demographics and outcomes between those fed formula and the no-formula subsample and between those fed at the breast and the bottle-only subsample. Preliminary confounders selected a priori because of their hypothesized relationship with infant feeding practices and the outcomes included parity, WIC, mother attending work or school >20 hours/week by 6 months postpartum, maternal education, relationship status, perceived financial difficulty, maternal race, and childcare attendance outside the home. Negative binomial regression examined associations between otitis media and diarrhea and each confounder. Confounders found to be associated with the outcome were retained in adjusted models to examine associations between feeding practices and each health outcome while we controlled for relevant sociodemographics.

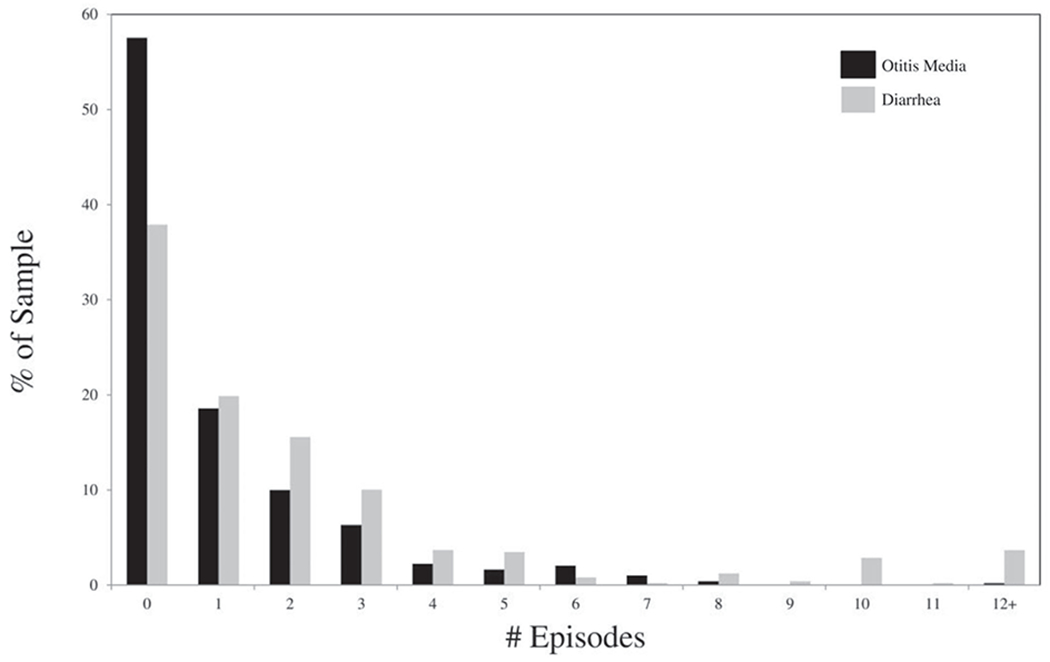

Associations between durations of breast milk feeding, feeding at the breast, expressed milk feeding, and formula feeding and otitis media and diarrhea were examined with the use of logistic and negative binomial regression models. Models predicted outcomes based on 1- (unadjusted and adjusted models), 3-, and 6-month (adjusted models) durations of each feeding variable. Logistic regression tested the association between binary health outcomes (0 episodes vs 1+ episodes) and feeding durations. Negative binomial regression models estimated the incidence rate ratio (IRR) of otitis media and diarrhea in relation to feeding behaviors. Because the otitis media and diarrhea outcomes used in these models represented the number of episodes in the first postnatal year and the dispersion parameter for negative binomial regression models was significantly different from zero, overdispersion of otitis media and diarrhea episodes were confirmed (Figure). Therefore, negative binomial regression methods were appropriate.

Figure.

Distribution of mother-reported episodes of otitis media and diarrhea in the first postnatal year.

Analyses were first conducted in the full sample. Exploratory analyses were then conducted in the no-formula and bottle-only subsamples. Analyses used SAS 9.3 (Cary, North Carolina)16 and STATA Intercooled 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).17

Results

Of the 813 mailed questionnaires, 501 were returned (62% response rate). Unintelligible responses (n = 2), those without feeding (n = 3) or outcome data (n = 1), and infants fed no breast milk or formula in the first 5 postnatal days (n = 4) were excluded. The final sample comprised 491 mother-infant dyads; 22% (n = 106) of children received no formula (no-formula subsample) in the first 6 months and 10% (n = 49) were fed by bottle only (bottle-only subsample) for the first postnatal year. Mothers of infants in the no-formula subsample were older (t = 2.5, P = .01), more likely to be multiparous (χ2 = 4.7, P = .03), highly educated (χ2 = 13.8, P = .0002), and living with a spouse/partner (χ2 = 4.7, P = .03); they were less likely to receive WIC (χ2 = 11.2, P = .0008), to perceive financial difficulty (χ2 = 4.4, P = .04), and to work >20 hours outside the home by 6 months postpartum (χ2 = 6.9, P = .0009) than mothers of infants who were fed formula at least once in the first 6 months (Table I). Infants in the no-formula subsample were more likely to attend childcare outside the home (χ2 = 5.5, P = .02) than infants who were fed formula. Mothers of infants in the bottle-only subsample were younger (t = 2.4, P = .02), more likely to receive WIC (χ2 = 19.8, P ≤ .0001), had lower educational attainment (χ2 = 39.3, P ≤ .0001), perceived more financial difficulty (χ2 = 5.2, P = .02), and were less likely to be living with a spouse/partner (χ2 = 8.8, P = .003) than mothers of infants who were fed at the breast at least once.

Table I.

Sociodemographics for the full study sample, and the no-formula and bottle-only subsamples

| Full study sample, N = 491 | Formula at least once, n = 385 | No-formula subsample, n = 106 | Test statistic and P value* | At breast at least once, n = 442 | Bottle-only subsample, n = 49 | Test statistic and P value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |||||||

| Maternal age, mean (SD), y‡ | 31.0 (4.9) | 31.1 (4.9) | 32.4 (4.6) |

t = 2.5 P = .01 |

31.0 (4.8) | 29.5 (5.3) |

t = 2.5 P = .02 |

| Parity, n (%)§ | |||||||

| 0 | 245 (49.9) | 197 (52.5) | 43 (40.6) | χ2 = 4.7 | 219 (49.6) | 26 (53.1) | χ2 = 0.22 |

| 1+ | 256 (50.1) | 178 (47.5) | 63 (59.4) | P = .03 | 223 (50.4) | 23 (46.9) | P = .64 |

| WIC receipt, n (%)§ | |||||||

| Yes | 137 (28.0) | 116 (31.1) | 16 (15.1) | χ2 = 11.2 | 110 (25.0) | 22 (44.9) | χ2 = 19.8 |

| No | 352 (72.0) | 257 (68.9) | 90 (84.9) | P = .0008 | 330 (75.0) | 27 (55.1) | P ≤ .0001 |

| Mother attended work or school >20/week in first 6 months postpartum, n (%)§ | |||||||

| Yes | 295 (60.1) | 243 (63.1) | 52 (49.1) | χ2 = 6.9 | 270 (61.1) | 25 (51.0) | χ2 = 1.9 |

| No | 196 (39.1) | 142 (36.9) | 54 (50.9) | P = .0009 | 172 (38.9) | 24 (49.0) | P = .17 |

| Maternal education level, n (%)§ | |||||||

| Some college or less | 156 (31.8) | 138 (35.9) | 18 (17.0) | χ2 = 13.8 | 121 (27.4) | 35 (71.4) | χ2 = 39.3 |

| College or postgraduate degree | 334 (38.2) | 246 (64.1) | 88 (83.0) | P = .0002 | 320 (72.6) | 14 (28.6) | P ≤ .0001 |

| Relationship status at start of pregnancy, n (%)§ | |||||||

| Living with spouse/partner | 433 (88.4) | 333 (86.7) | 100 (94.3) | χ2 = 4.7 | 396 (89.8) | 37 (75.5) | χ2 = 8.8 |

| Single/not living with spouse/partner | 57 (11.6) | 51 (13.3) | 6 (5.7) | P = .03 | 45 (10.2) | 12 (24.5) | P = .003 |

| Perceived financial difficulty at start of pregnancy, n (%)§ | |||||||

| Yes | 225 (45.8) | 186 (48.3) | 39 (36.8) | χ2 = 4.4 | 195 (44.1) | 30 (61.2) | χ2 = 5.2 |

| No | 266 (54.2) | 199 (51.7) | 67 (63.2) | P = .04 | 247 (55.9) | 19 (38.8) | P = .02 |

| Maternal race, n (%)§ | |||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 372 (75.8) | 286 (74.3) | 86 (81.1) | χ2 = 2.1 | 340 (76.9) | 17 (34.7) | χ2 = 3.2 |

| All others | 119 (24.2) | 99 (25.7) | 20 (18.9) | P = .15 | 102 (23.1) | 32 (65.3) | P = .07 |

| Child characteristics | |||||||

| Child sex, n (%)§ | |||||||

| Male | 255 (51.9) | 207 (53.8) | 48 (45.3) | χ2 = 2.4 | 231 (47.7) | 24 (49.0) | χ2 = 0.20 |

| Female | 236 (48.1) | 178 (46.2) | 58 (54.7) | P = .12 | 211 (52.3) | 25 (51.0) | P = .66 |

| Childcare outside the home, n (%)§ | |||||||

| Yes | 239 (48.8) | 198 (51.6) | 65 (61.3) | χ2 = 5.5 | 216 (49.0) | 23 (46.9) | χ2 = 0.07 |

| No | 251 (51.2) | 186 (48.4) | 41 (38.7) | P = .02 | 225 (51.0) | 26 (53.1) | P = .79 |

| Infant Health Outcomes (counts in first postnatal year) | |||||||

| Otitis Media, median (IQR)¶ | 0 (0,1) | 0 (0,1) | 0 (0,2) | z = −.04 P = .97 | 0 (0,1) | 0 (0,2) | z = 0.79 P = .43 |

| Diarrhea, median (IQR)¶ | 1 (0,3) | 1 (0,3) | 1 (0,2) | z = −2.6 P = .01 | 1 (0,3) | 4 (0,4) | z = 3.2 P = .002 |

The no-formula subsample includes infants who were fed any combination of at the breast and/or expressed milk.

The bottle-only subsample includes infants who were fed any combination of expressed milk and/or formula.

Group comparisons tested differences between those fed formula before 6 months vs those fed no formula before 6 months (no-formula subsample).

Group comparisons tested differences between those ever fed at the breast vs those never fed at the breast (bottle-only subsample).

t test.

χ2 test.

Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test.

Feeding Patterns in the First Year of Life

Few infants (6.5%) were fed one substance exclusively by the same mode in the first postnatal year. Of these, 41% were fed at the breast only, 59% were fed formula only, and no infants were fed expressed milk only for the entire first postnatal year. The majority of infants (93.5%) were fed multiple substances and/or modes. Of these, 76% of infants were fed at the breast, expressed milk, and formula in the first postnatal year. The median duration of breast milk feeding was 7 months (IQR 2.5, 12.2), with longer median durations of feeding at the breast (median 6.0; IQR 1.0, 12.0) than expressed milk feeding (median 4.0; IQR 1.0, 8.8) reported. The median duration of formula feeding was 10.9 months (IQR 3.0, 12.0). All infants in the bottle-only subsample received at least some formula; 61% received expressed milk at least once.

Otitis Media

The median number of otitis media episodes was 0.0 (IQR 0.0, 1.0); 58% of infants did not experience otitis media in the first postnatal year (Table I and Figure). More episodes of otitis media were associated with being a child of a white, non-Hispanic mother (χ2 = 6.53, P = .01), being a child of a multiparous mother (χ2 = 3.94, P = .04), and attending childcare outside the home (χ2 = 14.14, P = .0002). WIC, mother attending work or school >20 hours/week by 6 months postpartum, maternal education, relationship status, and perceived financial difficulty were not associated with episodes of otitis media.

Logistic Regression (Binary Models).

Duration of feeding at the breast was associated with reduced odds of ever experiencing otitis media in the first postnatal year for the full sample, after adjustment for confounding variables (OR1-month, adjusted 0.96, 95% CI 0.92-0.99; OR6-month, adjusted 0.77, 95% CI 0.61-0.98; Table II). In the no-formula subsample, longer duration of feeding expressed milk was associated with increased odds of ever experiencing otitis media (OR1-month, adjusted 1.14, 95% CI 1.00-1.29; OR6-month, adjusted 2.15, 95% CI 1.01-4.55).

Table II.

Associations between infant feeding practices and otitis media outcomes

| Logistic regression (binary) |

Negative binomial regression (continuous count) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration |

||||||||

| 1 month |

3 months |

6 months |

1 month |

3 months |

6 months |

|||

| Type of feeding | Unadjusted model OR (95% CI) | Adjusted model OR (95% CI) | Adjusted model OR (95% CI) | Adjusted model OR (95% CI) | Unadjusted model IRR (95% CI) | Adjusted model IRR (95% CI) | Adjusted model IRR (95% CI) | Adjusted model IRR (95% CI) |

| All observations (n = 491) | ||||||||

| Breast milk | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | 0.91 (0.80-1.03) | 0.83 (0.64-1.07) | 0.98 (0.94-1.01) | 0.97 (0.94-1.01) | 0.95 (0.89-1.01) | 0.85 (0.70-1.04) |

| At the breast | 0.96 (0.92-0.99) | 0.96 (0.92-0.99) | 0.88 (0.78-0.99) | 0.77 (0.61-0.98) | 0.98 (0.94-1.01) | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) | 0.94 (0.89-1.01) | 0.84 (0.70-1.02) |

| Expressed milk | 1.01 (0.97-1.10) | 0.99 (0.96-1.05) | 1.00 (0.87-1.16) | 1.01 (0.76-1.35) | 1.00 (0.96-1.04) | 0.98 (0.95-1.02) | 0.97 (0.90-1.05) | 0.92 (0.73-1.15) |

| Formula | 1.02 (0.98-1.06) | 1.02 (0.98-1.06) | 1.06 (0.94-1.19) | 1.12 (0.88-1.42) | 1.01 (0.98-1.05) | 1.01 (0.98-1.05) | 1.03 (0.96-1.09) | 1.08 (0.89-1.31) |

| Exploratory subgroup analyses | ||||||||

| No-formula (n = 106) | ||||||||

| At the breast | 0.82 (0.60-1.13) | 0.73 (0.52-1.04) | 0.40 (0.14-1.11) | 0.16 (0.02-1.23) | 0.99 (0.75-1.31) | 0.88 (0.66-1.17) | 0.67 (0.28-1.60) | 0.46 (0.08-2.56) |

| Expressed milk | 1.15 (1.03-1.28) | 1.14 (1.00-1.29) | 1.47 (1.00-2.13) | 2.15 (1.01-4.55) | 1.10 (0.99-1.22) | 1.06 (0.95-1.18) | 1.20 (0.87-1.65) | 1.43 (0.75-2.71) |

| Bottle-only (n = 49) | ||||||||

| Expressed milk | 1.14 (0.93-1.41) | 1.12 (0.90-1.39) | 1.41 (0.74-2.71) | 1.99 (0.54-7.33) | 1.06 (0.93-1.21) | 1.05 (0.93-1.20) | 1.11 (0.86-1.44) | 1.37 (0.63-2.97) |

| Formula | 0.63 (0.30-1.21) | 0.53 (0.23-1.24) | 0.15 (0.01-1.88) | 0.02 (0.00-3.54) | 0.95 (0.80-1.14) | 0.94 (0.78-1.14) | 0.89 (0.61-1.30) | 0.70 (0.23-2.14) |

Durations represent total duration throughout the first postnatal year, not necessarily consecutive duration.

The no-formula subsample includes infants who were fed any combination of at the breast and/or expressed milk.

The bottle-only subsample includes infants who were fed any combination of expressed milk and/or formula.

Confounders in adjusted models: parity, maternal race, and child care attendance outside the home.

Negative Binomial Regression (Continuous Count Models).

Durations of breast milk feeding, feeding at the breast, expressed milk feeding, and formula feeding were not associated with episodes of otitis media in the full sample or the exploratory no-formula or bottle-only subsamples of infants.

Diarrhea

The median number of diarrhea episodes in the first postnatal year was 1.0 (IQR 0.0, 3.0); 38% of infants did not experience diarrhea in the first postnatal year (Table I and Figure). Fewer diarrhea episodes were reported in the no-formula subsample compared with those that were fed at least some formula (z = −2.6, P = .01). The bottle-only subsample had more diarrhea episodes than those fed at the breast at least once (z = 3.2, P = .002). More diarrhea episodes were associated receipt of WIC (χ2 = 6.1, P = .01), perceived financial difficulty (χ2 = 19.4, P < .0001), and childcare attendance outside the home (χ2 = 11.0, P = .0009). Parity, mother attending work or school >20 hours/week by 6 months postpartum, maternal education, relationship status, and race were not associated with episodes of diarrhea.

Logistic Regression (Binary Models).

Breast milk feeding (OR1-month, adjusted 0.94, 95% CI 0.90-0.99; OR6-month, adjusted 0.70, 95% CI 0.54-0.89) and feeding at the breast (OR1-month, adjusted 0.94, 95% CI 0.90-0.98; OR6-month, adjusted 0.70, 95% CI 0.54-0.92) durations were associated with a reduced odds of ever having diarrhea in the first postnatal year for the full sample (Table III). Formula feeding duration was associated with increased odds of diarrhea in the full sample unadjusted model (OR1-month 1.04, 95% CI 1.00-1.08), however, this result was not statistically significant in the adjusted model (OR1-month, adjusted 1.03, 95% CI 0.99-1.07). Feeding durations were not associated with ever having diarrhea in the exploratory no-formula or bottle-only subsamples.

Table III.

Associations between infant feeding practices and diarrhea outcomes

| Logistic regression (binary) |

Negative binomial regression (continuous count) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration |

||||||||

| 1 month |

3 months |

6 months |

1 month |

3 months |

6 months |

|||

| Type of feeding | Unadjusted model OR (95% CI) | Adjusted model OR (95% CI) | Adjusted model OR (95% CI) | Adjusted model OR (95% CI) | Unadjusted model IRR (95% CI) | Adjusted model IRR (95% CI) | Adjusted model IRR (95% CI) | Adjusted model IRR (95% CI) |

| All observations (n = 491) | ||||||||

| Breast milk | 0.92 (0.89-0.96) | 0.94 (0.90-0.99) | 0.84 (0.73-0.96) | 0.70 (0.54-0.92) | 0.93 (0.90-0.96) | 0.95 (0.93-0.98) | 0.91 (0.86-0.97) | 0.75 (0.63-0.91) |

| At the breast | 0.92 (0.90-0.96) | 0.94 (0.90-0.98) | 0.83 (0.74-0.94) | 0.70 (0.54-0.89) | 0.93 (0.90-0.96) | 0.95 (0.93-0.98) | 0.91 (0.86-0.96) | 0.74 (0.63-0.88) |

| Expressed milk | 0.97 (0.92-1.01) | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | 0.94 (0.81-1.08) | 0.88 (0.66-1.18) | 0.95 (0.92-0.99) | 0.98 (0.94-1.01) | 0.95 (0.89-1.02) | 0.86 (0.70-1.06) |

| Formula | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 1.09 (0.97-1.23) | 1.19 (0.94-1.51) | 1.07 (1.04-1.10) | 1.05 (1.02-1.08) | 1.10 (1.04-1.17) | 1.34 (1.13-1.54) |

| Exploratory subgroup analyses | ||||||||

| No-formula (n = 106) | ||||||||

| At the breast | 0.98 (0.71-1.35) | 0.98 (0.71-1.34) | 0.93 (0.36-2.39) | 0.87 (0.13-5.70) | 1.13 (0.87-1.46) | 1.15 (0.90-1.49) | 1.55 (0.73-3.32) | 2.41 (0.56-11.27) |

| Expressed milk | 1.07 (0.95-1.24) | 1.05 (0.95-1.17) | 1.16 (0.40-5.45) | 1.35 (0.72-2.55) | 0.99 (0.92-1.08) | 1.00 (0.92-1.09) | 1.00 (0.78-1.28) | 1.00 (0.61-1.64) |

| Bottle-only (n = 49) | ||||||||

| Expressed milk | 1.01 (0.80-1.28) | 1.04 (0.80-1.35) | 1.11 (0.50-2.45) | 1.23 (0.25-5.98) | 0.89 (0.80-1.00) | 0.96 (0.85-1.10) | 0.93 (0.72-1.20) | 0.81 (0.37-1.74) |

| Formula | 0.81 (0.47-1.42) | 0.77 (0.44-1.32) | 0.45 (0.09-2.29) | 0.20 (0.01-5.24) | 1.12 (0.96-1.31) | 1.05 (0.91-1.22) | 1.11 (0.83-1.49) | 1.35 (0.56-3.28) |

Durations represent total duration throughout the first postnatal year, not necessarily consecutive duration.

The no-formula subsample includes infants who were fed any combination of at the breast and/or expressed milk.

The bottle-only subsample includes infants who were fed any combination of expressed milk and/or formula.

Confounders in adjusted models: receipt of WIC, perceived financial ability, and child care attendance outside the home.

Negative Binomial Regression (Continuous Count Models).

In the full sample, longer durations of breast milk feeding (IRR1-month, adjusted 0.95, 95% CI 0.93-0.98; IRR6-month, adjusted 0.75, 95% CI 0.63-0.91) and feeding at the breast (IRR1-month, adjusted 0.95, 95% CI 0.93-0.98; IRR6-month, adjusted 0.74, 95% CI 0.63-0.88) were associated with fewer episodes of diarrhea, and longer duration of formula feeding (IRR1-month, adjusted 1.05, 95% CI 1.02-1.08; IRR6-month, adjusted 1.34, 95% CI 1.13-1.54) was associated with more episodes of diarrhea (Table III). Although expressed milk feeding was associated with fewer episodes of diarrhea in the full sample, unadjusted model (IRR1-month 0.95, 95% CI 0.92-0.99), the adjusted model did not reach statistical significance (IRR1-month, adjusted 0.98, 95% CI 0.94-1.01). Feeding durations were not associated with diarrhea episodes in the no-formula or bottle-only subsamples.

Discussion

This study identified distinct contributions of substance and mode in infant feeding practices during the first year of life on otitis media and diarrhea in a prospective cohort. This work begins to identify unique and separate associations of substance fed (breast milk vs formula) and mode of breast milk delivery (at the breast vs bottle) and demonstrates the importance of exploring these distinctive exposures in infant feeding research.

One month of feeding at the breast was associated with 4% reduced odds of ever having otitis media in the full sample, adjusted model, and a 17% reduced odds for infants fed at the breast for 6 months. Among infants who were fed no-formula in the first 6 months postpartum, the odds of experiencing otitis media increased by approximately 14% for infants fed expressed milk for 1 month and by 115% with 6 months of expressed milk feeding, after we controlled for confounding variables. The restriction of this sample to exclude infants fed formula allows us to elucidate the distinct role of mode of breast milk delivery from substance fed and provides evidence that expressed milk feeding increases risk for otitis media. This finding suggests that feeding mode rather than substance fed underlies the differences in otitis media risk.

Duration of breast milk feeding (inclusive of feeding at the breast and expressed milk) and feeding at the breast, specifically, were associated with reduced risk of diarrhea, and increased formula duration was associated with increased risk of diarrheal illness in the full sample, adjusted models. The reduced odds of experiencing diarrhea based on breast milk or feeding at the breast durations were similar. Specifically, the odds of experiencing diarrhea for infants fed breast milk or at the breast for 6 months were both reduced by approximately 30% and the number of diarrhea episodes was reduced by 25% for infants fed breast milk for 6 months and by 26% for infants fed at the breast for 6 months. Furthermore, the expected number of diarrhea episodes for infants fed formula for 6 months increased by 34%. This finding suggests that the substance fed, rather than the mode of feeding, may underlie differences in risk of diarrheal illness.

Mother-infant dyads no longer fit into a single feeding category classified by substance. Rather, feeding behaviors are inclusive of multiple substances, different modes, and various proportions of breast milk (eg, 100% breast milk vs a combination of breast milk and formula) within a given month or even day are used.3 Very few women (6.5% in our sample, which did not include women who stated an intention to “bottle feed” exclusively) feed their infant the same substance via the same mode throughout the first postnatal year. In addition, in our sample 71% of all infants were fed at the breast, expressed milk, and formula in the first year, further illustrating the complexity of how infants are fed. When the substance is explored without regard to the mode of breast milk delivery, unique contributions of each are impossible to examine. The need to classify infant feeding practices not only by substance but also by mode of breast milk delivery has been articulated elsewhere.18–20

Although there is a large amount of support for the beneficial contribution of prolonged breastfeeding to infant health, the distinctive contributions of substance and mode have not yet been fully identified.21–25 Beaudry et al7 reported that children who are breastfed have a 37%-47% reduced risk of diarrhea and a 43%-58% reduced risk of otitis media compared with infants fed formula or cow’s milk from a bottle. Ladomenou et al23,26 reported that infants breastfed exclusively for the first 6 months experienced approximately 4 episodes of otitis media compared with nearly 12 episodes experienced by infants exposed to partial or no breastfeeding. Additionally, the pooled odds of otitis media is 2 times greater when formula is introduced between 3 and 6 months of age, compared with exclusive breastfeeding.27 These findings are in line with several studies related to diarrhea and other gastrointestinal infections.25,28–37 One limitation, however, is that these studies do not differentiate between feeding at the breast and expressed milk feeding in their definitions of breastfeeding.

The Infant Feeding Practices Study II explored associations between various feeding modes and child health by identifying increased risk for coughing and wheezing and increased weight gain when infants were fed expressed milk from a bottle and formula or formula only compared with infants fed at the breast.5,6 Our work extends these findings to common infant illnesses, otitis media and diarrhea, and further illustrates that feeding expressed milk may not be equivalent to feeding at the breast in its relationships to infant health.

A potential mechanism, applicable to both formula and expressed milk, is the potential for microbial contamination of the bottle from which the infant is fed. Previous studies have reported that 55% of mothers who prepared formula for their infant did not always wash their hands before preparation, one-third of mothers who expressed milk never sterilized the pump collection kit, and 17%-32% did not thoroughly wash the bottle nipple between feeds.38,39 Additionally, and specifically related to otitis media, standard bottles used to feed infants often create a negative pressure during feeding. This negative pressure is then transferred from the bottle to the middle ear of the infant during feedings, which may precipitate otitis media.40 Finally, the protective components of breast milk may be altered by collection, freezing, and storage practices.11–15

In addition to identifying the distinct contributions of substance fed and mode of breast milk delivery to infant health, this study demonstrated large socioeconomic differences in feeding patterns. Mothers in the no-formula subsample were of greater socioeconomic status (SES) than those who fed their infant formula and women in the bottle-only subsample were of lower SES than those who fed their infant at the breast. This finding is in line with research that shows positive associations between SES and breastfeeding initiation and duration and may be explained by health care and information resources available to and accessed by mothers of greater SES.41,42

There were limitations to this work. First, we relied on mothers’ retrospective accounts of feeding practices that began 12 months prior and the recall of the introduction of nonhuman milk liquids such as formula in this timeframe may not be accurate.43,44 Second, there may be additional confounding variables not accounted for in this study. Next, women who stated an intention to “bottle feed” exclusively were not recruited for this study. Finally, because of the small numbers of dyads who exclusively participated in any one mode or substance in the first postnatal year, it was impossible to identify large mutually exclusive groups that solely relied on one substance or mode for analysis. The exploratory analyses used stratification to focus on specific subsamples of interest; however, the statistical power of these models was limited due to small sample sizes.

We presented several strengths in this work. First, although recall bias may affect the accuracy of reporting formula feeding practices, literature demonstrates reliability of retrospective recall of infant health and breastfeeding practices over short periods, such as 1-3 years; some women report accurate breastfeeding recall 20 years after birth.43–46 Second our questionnaire provided a consistent definition of diarrhea for all respondents to allow mothers to report their own baby’s stool pattern and to minimize the potential for misclassification of typical infant stool as diarrhea. Third the aim of our exploratory analyses was to control for measured and unmeasured factors that influence early feeding practice decisions. Next, our sample was diverse: 28% of mothers indicated that they received WIC and the sample comprised 24% nonwhite participants. Therefor our results may apply to families of varying sociodemographic characteristics. Finally, the negative binomial regression models were ideal for the outcome data where zero episodes were common.

Larger studies that differentiate feeding at the breast from expressed milk feeding are needed to confirm that feeding the breast is preferable to expressed milk feeding and that expressed milk feeding is preferable to formula feeding. In addition, future research in this area should expand on the findings presented here by exploring these associations across multiple domains of health and development. ■

Acknowledgments

Supported by internal funds of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, the National Institutes of Health (NIH; K23ES14691), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001070). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the NIH. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank the women who participated in the Moms2Moms Study at Chelsea Dillon, Kendra Heck, Rachel Ronau, and Kamma Smith (Nationwide Children’s Hospital) for data collection and administrative support. We also thank Katherine Strafford, MD (Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center), for her support of the project, and Mark Klebanoff, MD, and Benjamin McDonald, MD (Nationwide Children’s Hospital), for commenting on the manuscript.

Glossary

- IRR

Incidence rate ratio

- SES

Socioeconomic status

- WIC

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

References

- 1.Labiner-Wolfe J, Fein SB, Shealy KR, Wang C. Prevalence of breast milk expression and associated factors. Pediatrics 2008;122(suppl 2):S63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binns CW, Win NN, Zhao Y, Scott JA. Trends in the expression breastmilk 1993-2003. Breastfeed Rev 2006;14:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geraghty SR, Khoury JC, Kalkwarf HJ. Human milk pumping rates of mothers of singletons and mothers of multiples. J Hum Lact 2005;21:413–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li RW, Magadia J, Fein SB, Grummer-Strawn LM. Risk of bottle-feeding for rapid weight gain during the first year of life. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166:431–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soto-Ramirez N, Karmaus W, Zhang H, Davis S, Agarwal S, Albergottie A. Modes of infant feeding and the occurrence of coughing/wheezing in the first year of life. J Hum Lact 2013;29:71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer MS, Chalmers B, Hodnett ED, Sevkovskaya Z, Dzikovich I, Shapiro S, et al. Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): a randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA 2001;285:413–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaudry M, Dufour R, Marcoux S. Relation between infant-feeding and infections during the first 6 months of life. J Pediatr 1995;126:191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Trikalinos TA, Lau J. A Summary of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Evidence Report on Breastfeeding in Developed Countries. Breastfeed Med 2009;4(suppl 1):S17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldman AS. The immune system of human milk: antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating properties. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1993;12:664–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breakey AA, Hinde K, Valeggia CR, Sinofsky A, Ellison PT. Illness in breastfeeding infants relates to concentration of lactoferrin and secretory Immunoglobulin A in mother’s milk. Evol Med Public Health 2015;2015:21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williamson MT, Murti PK. Effects of storage, time, temperature, and composition of containers on biologic components of human milk. J Hum Lact 1996;12:31–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence RA. Storage of human milk and the influence of procedures on immunological components of human milk. Acta Paediatr Suppl 1999;88:14–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penn AH, Altshuler AE, Small JW, Taylor SF, Dobkins KR, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Effect of digestion and storage of human milk on free fatty acid concentration and cytotoxicity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;59:365–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zonneveld MI, Brisson AR, van Herwijnen MJ, Tan S, van de Lest CH, Redegeld FA, et al. Recovery of extracellular vesicles from human breast milk is influenced by sample collection and vesicle isolation procedures. J Extracell Vesicles 2014. Aug 14;3. 10.3402/jev.v3.24215. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jocson MA, Mason EO, Schanler RJ. The effects of nutrient fortification and varying storage conditions on host defense properties of human milk. Pediatrics 1997;100:240–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SAS software, v9.3 [computer program]. Cary (NC): SAS Institute Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.STATA 12.0 Statistics/Data Analysis. College Station (TX): Stata; 1985-2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasmussen KM, Geraghty SR. The quiet revolution: breastfeeding transformed with the use of breast pumps. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1356–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geraghty SR, Rasmussen KM. Redefining “breastfeeding” initiation and duration in the age of breastmilk pumping. Breastfeed Med 2010;5:135–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felice JP, Rasmussen KM. Breasts, pumps and bottles, and unanswered questions. Breastfeed Med 2015;10:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovar MG, Serdula MK, Marks JS, Fraser DW. Review of the epidemiologicevidence for an association between infant-feeding and infant health. Pediatrics 1984;74:615–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrahams SW, Labbok MH. Breastfeeding and otitis media: a review of recent evidence. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2011;11:508–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ladomenou F, Moschandreas J, Kafatos A, Tselentis Y, Galanakis E. Protective effect of exclusive breastfeeding against infections during infancy: a prospective study. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:1004–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowatte G, Tham R, Allen KJ, Tan DJ, Lau MXZ, DAi X, et al. Breastfeeding and childhood acute otitis media: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2015;104:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ajetunmobi OM, Whyte B, Chalmers J, Tappin DM, Wolfson L, Fleming M, et al. Breastfeeding is associated with reduced childhood hospitalization: evidence from a Scottish Birth Cohort (1997-2009). J Pediatr 2015;166:620–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ladomenou F, Kafatos A, Tselentis Y, Galanakis E. Predisposing factors for acute otitis media in infancy. J Infect 2010;61:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNiel ME, Labbok MH, Abrahams SW. What are the risks associated with formula feeding? A re-analysis and review. Breastfeed Rev 2010;18:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paine R, Coble RJ. Breast-feeding and infant health in a rural US community. Am J Dis Child 1982;136:36–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunningham AS. Morbidity in breast-fed and artificially fed infants. II. J Pediatr 1979;95:685–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Shannon FT, Taylor B. Infant health and breast-feeding during the first 16 weeks of life. Aust Paediatr J 1978;14:254–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Shannon FT, Taylor B. Breast-feeding, gastrointestinal and lower respiratory illness in the first two years. Aust Paediatr J 1981;17:191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fallot ME, Boyd JL, Oski FA. Breast-feeding reduces incidence of hospital admissions for infection in infants. Pediatrics 1980;65:1121–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howie PW, Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, Clark A, Florey CD. Protective effect of breast feeding against infection. BMJ 1990;300:11–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raisler J, Alexander C, O’Campo P. Breast-feeding and infant illness: a dose-response relationship? Am J Public Health 1999;89:25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen A, Rogan WJ. Breastfeeding and the risk of postneonatal death in the United States. Pediatrics 2004;113:e435–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santos FS, Santos FC, dos Santos LH, Leite AM, de Mello DF. Breastfeeding and protection against diarrhea: an integrative review of literature [in Portuguese]. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2015;13:435–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan J, Vesel L, Bahl R, Martines JC. Timing of breastfeeding initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding during the first month of life: effects on neonatal mortality and morbidity—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:468–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Labiner-Wolfe J, Fein SB, Shealy KR. Infant formula—handling education and safety. Pediatrics 2008;122(suppl 2):S85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Labiner-Wolfe J, Fein SB. How US mothers store and handle their expressed breast milk. J Hum Lact 2013;29:54–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown CE, Magnuson B. On the physics of the infant feeding bottle and middle ear sequela: ear disease in infants can be associated with bottle feeding. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2000;54:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heck KE, Braveman P, Cubbin C, Chavez GF, Kiely JL. Socioeconomic status and breastfeeding initiation among California mothers. Public Health Rep 2006;121:51–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dubois L, Girard M. Social determinants of initiation, duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding at the population level: the results of the Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Quebic (ELDEQ 1998-2002). Can J Public Health 2003;94:300–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li R, Scanlon KS, Serdula MK. The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. Nutr Rev 2005;63:103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Launer LJ, Forman MR, Hundt GL, Sarov B, Chang D, Berendes HW, et al. Maternal recall of infant feeding events is accurate. J Epidemiol Community Health 1992;46:203–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Natland ST, Andersen LF, Nilsen TI, Forsmo S, Jacobsen GW. Maternal recall of breastfeeding duration twenty years after delivery. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Gelder MM, Roeleveld N. Validation of maternal self-report in retrospective studies. Early Hum Dev 2011;87:43–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]