Abstract

Purpose

The utilization rate of robotic surgery for bariatric procedures is not well-described. Our study identified the proportion of metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) procedures in the United States between 2015 and 2020 performed using a robotic (R-) or laparoscopic (L-) approach.

Materials and Methods

A descriptive analysis of the 2015–2020 Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP) Participant User Data File (PUF) datasets was performed. The primary outcome was (1) surgical cases performed annually and (2) proportion of cases performed using a R- or L- approach. Analysis was done separately for sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS), and revisional bariatric surgery (RBS). Statistical analysis consisted of means and proportions, fold difference, annual slope, and Student’s t tests or chi-square tests as appropriate, with statistical significance set to p < .05.

Results

A total of 1,135, 214 procedures were captured between 2015 and 2020. R-RYGB increased from 2554 to 6198 (6.8% to 16.7%), R-SG increased from 5229 to 17,063 (6.0% to 17.2%), R-RBS increased from 993 to 3386 (4.7% to 17.4%), and R-BPD-DS increased from 221 to 393 (22.0% to 28.4%). The greatest annual increase was observed among R-RBS and R-SG (3.70-fold difference; slope 2.4% per year and 2.87-fold difference; slope 2.2% per year, respectively).

Conclusion

There is a nationwide increase in the utilization of a R- approach in bariatric surgery. There are concerns related to the potential increase in healthcare expenditures related to robotics. Further studies are needed to establish key performance indicators along with guidelines for training, adoption and utilization of a R- approach.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Robotics, Robotic utilization, Bariatrics, Bariatric surgery, Sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, Duodeno-ileostomy, Revisional bariatric surgery, Laparoscopy

Introduction

The first documented case of robotic bariatric surgery took place in 1998 when Drs. Cadiere and Himpens in Belgium performed a robotic-assisted laparoscopic gastric banding [1, 2]. Since that time, the robotic surgical system has undergone several iterations of innovation in regards to the surgical platform’s functionality and efficiency [3]. Also, the time period till a surgeon develops expertise with the robotic platform has been truncated, with surgeons in today’s era requiring fewer cases to become more proficient with the platform [4]. Lastly, although still under significant scrutiny in the surgical community, more recent literature suggests that the outcomes of robotic-assisted surgery are improving over time [5].

The advantages of using a robotic approach include easier hand-sewing in anatomically confined spaces, better control of stoma size, a lower likelihood of potential tissue injury, and a possible decrease in wound infection rates [2, 3]. Even in the absence of regulatory committee guidelines supporting the use of robotics in bariatric surgery, bariatric surgeons in the United States of America (USA) have begun incorporating robotics into their routinely performed procedures. In regard to bariatric surgery caseload, there has been a noticeable increase in the number of bariatric surgeries performed annually in the USA, with a rise from 158,000 cases in 2011 to 256,000 in 2019; however, the change in the type of surgical approach used is not as well-described in the literature [6].

With the advent of the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP), case numbers along with the 30-day surgical outcomes are collected and shared with MBSAQIP-accredited centers using the Participant User Data File (PUF). The objective of our study was to investigate the proportion of bariatric cases that were performed using a robotic approach for the years 2015–2020 to have a better understanding of the adoption rates and the utilization trends of robotic-assisted surgery in MBSAQIP-accredited centers.

Methods

After receiving Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, the 2015–2020 PUF datasets were requested from the MBSAQIP Data Registry. The MBSAQIP collects bariatric surgery data from various accredited hospital systems in the USA and Canada. To receive accreditation, the hospital system must successfully complete a peer-review evaluation conducted by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS).

Given the primary aim of the study was to identify the most recent trends in robotic utilization rates in the field of bariatric surgery, the primary outcomes included: (1) the total number of bariatric surgery cases performed annually from 2015 to 2020 and (2) the proportion of cases performed using a robotic (R-) or laparoscopic (L-) approach. Surgical procedures included sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS), in addition to revisional bariatric surgery (RBS). In order to provide clear and consistent analysis between the various PUF years, it is important to acknowledge the difference in nomenclature in PUF years and how the incongruencies were resolved. The 2015–2019 PUF datasets do not make a clear distinction between revisions and conversions, whereas the 2020 PUF dataset clearly stratifies RBS cases into two types: revisions and conversions. In our analysis, RBS is defined as an all-encompassing term capturing both revisions and conversions; therefore, revisions and conversions were combined into a single RBS parameter in the 2020 PUF file for our analysis.

Data Analysis

Using the 2015–2020 MBSAQIP PUF datasets, we first excluded patients with previous foregut surgery, absence of stapler used/anastomosis completed, and lack of 30-day follow-up data. We then created three separate groups based on the following criteria: (1) Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) (principal operative procedure CPT code = 43644); sleeve gastrectomy (SG) (principal operative procedure CPT code = 43775); and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS) (principal operative procedure CPT code = 43845). For our fourth group, which combined conversions and revisions into the revisional bariatric surgery (RBS) group (using variables “CPTUNLISTED_REVCONV” for 2015–2019 and “PROCEDURE_TYPE” for 2020), we only excluded patients with lack of 30-day follow-up data. For 2015–2019, we used the “SURGICAL_APPROACH” variable to extract “conventional laparoscopic (thoracoscopic)” and “robotic-assisted” groups. For 2020, the “SURGICAL_APPROACH” variable was coded differently (i.e., “endoscopic,” “laparoscopic,” and “open”); therefore, we only extracted “laparoscopic” patients and used the “ROBOTIC_ASST” variable to differentiate conventional laparoscopic from robotic-assisted patients.

Within each group, we compared demographic and clinical outcomes for conventional laparoscopic versus robotic procedures using Student’s t tests for normally distributed continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 28 (Armonk, NY, IBM Corp.). For computation of the procedure type percentages, the common denominator used for the calculation was the total number of cases captured by merging PUF 2015–2020 after the application of our previously described exclusion criteria. To evaluate trends in robotic surgery over time within each of the four groups, we replicated the approach used by Sheetz et al. (2020) by calculating the proportion of robotic surgeries at our start date (2015) and end date (2020), then obtaining the fold difference (i.e., 2020 proportional robotic surgery usage divided by 2015 proportional robotic surgery usage), and finally determining the annual change in the proportional use of robotic surgery by calculating the linear regression slope for the trend from 2015 to 2020, with year representing the continuous independent variable. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

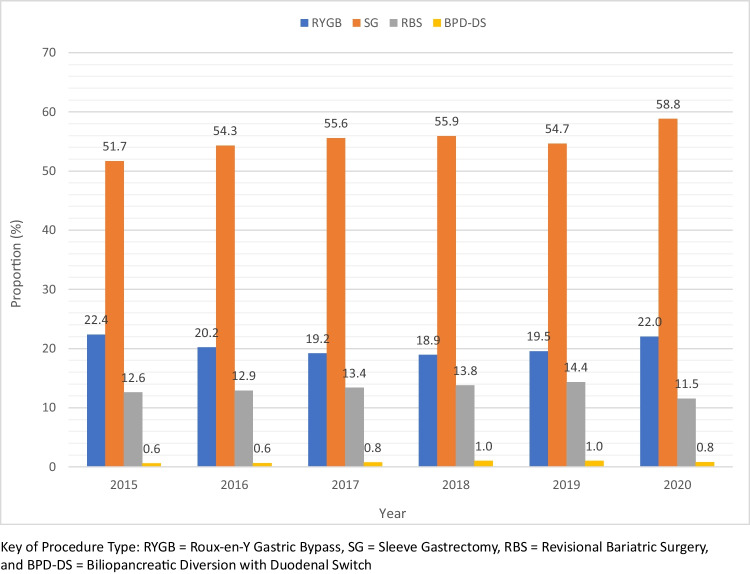

After reformatting and merging of the 2015–2020 PUF datasets, there were 1,135,214 data points, which reduced to 1,014,752 after excluding previous foregut surgery, absence of stapler used/anastomosis completed, and lack of 30-day follow-up data for the RYGB, SG, and BPD-DS groups. The proportions of each type of bariatric procedure investigated stratified into procedure type by year is presented in Fig. 1. The total number of metabolic bariatric surgery (MBS) cases included in our study for the years 2015–2020 was 1,014,752 cases. Patient demographics for all MBS cases included in our study (RYGB, SG, RBS, and BPD-DS) are presented in Table 1. The total number of metabolic bariatric surgery (MBS) procedures divided by type and year of performance are shown in Table 2. The total number for the years 2015–2020 for SG, RYGB, BPD-DS, and RBS was 626,198 cases (61.7%), 230,031 cases (22.7%), 9211(0.9%), and 149,312 cases (14.7%), respectively (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of MBS performed annually by procedure type

Table 1.

Basic demographics of MBS patients from 2015 to 2020 combined

| Variable | RYGB | SG | BPD-DS | RBS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lap (n = 199,175) | Robot (n = 23,565) | p valuec | Lap (n = 537,856) | Robot (n = 64,821) | p valuec | Lap (n = 6403) | Robot (n = 2044) | p valuec | Lap (n = 121,459) | Robot (n = 12,855) | p valuec | |

| Age (year) (mean ± SD)b | 45.2 ± 11.8 | 45.9 ± 12.0 | < .001 | 44.1 ± 12.1 | 44.0 ± 12.0 | .15 | 43.9 ± 11.5 | 42.9 ± 11.0 | .001 | 49.3 ± 11.4 | 49.4 ± 11.2 | .85 |

| Gender (n, %) |

Female: 161,133 (80.9%) Male: 38,042 (19.1%) |

Female: 19,205 (81.5%) Male: 4360 (18.5%) |

.06 |

Female: 427,596 (79.5%) Male: 110,260 (20.5%) |

Female: 52,051 (80.3%) Male: 12,770 (19.7%) |

< .001 |

Female: 4616 (72.1%) Male: 1787 (27.9%) |

Female: 1502 (73.5%) Male: 542 (26.5%) |

.21 |

Female: 104,212 (85.8%) Male: 17,247 (14.2%) |

Female: 11,068 (86.1%) Male: 1787 (13.9%) |

.59 |

| Race (n, %) |

Black: 28,084 (14.1%) White: 147,190 (73.9%) Other: 23,901 (12.0%) |

Black: 3770 (16.0%) White: 17,698 (75.1%) Other: 2097 (8.9%) |

< .001 |

Black: 104,344 (19.4%) White: 378,113 (70.3%) Other: 55,399 (10.3%) |

Black: 14,779 (22.8%) White: 44,078 (68.0%) Other: 5964 (9.2%) |

< .001 |

Black: 602 (9.4%) White: 5148 (80.4%) Other: 653 (10.2%) |

Black: 405 (19.8%) White: 1420 (69.5%) Other: 219 (10.7%) |

< .001 |

Black: 21,620 (17.8%) White: 88,786 (73.1%) Other: 11,053 (9.1%) |

Black: 2519 (19.6%) White: 9308 (72.4%) Other 1028 (8.0%) |

< .001 |

| Preoperative body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) (mean ± SD)a | 45.7 ± 8.5 | 45.3 ± 8.5 | < .001 | 44.9 ± 8.1 | 44.9 ± 8.8 | .09 | 51.4 ± 9.5 | 52.5 ± 10.0 | < .001 | 39.0 ± 10.9 | 40.0 ± 10.5 | < .001 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification (n, %) |

1: 395 (0.2%) 2: 32,065 (16.1%) 3: 157,745 (79.2%) 4: 8,960 (4.5%) 5: 10 (.005%) |

1: 47 (0.2%) 2: 4006 (17.0%) 3: 18,663 (79.2%) 4: 848 (3.6%) 5: 1 (.004%) |

< .001 |

1: 1,610 (0.3%) 2: 124,776 (23.2%) 3: 393,675 (73.2%) 4: 17,749 (3.3%) 5: 46 (.009%) |

1: 262 (0.4%) 2: 13,901 (21.4%) 3: 48,193 (74.3%) 4: 2,460 (3.8%) 5: 5 (.008) |

< .001 |

1: 21 (0.3%) 2: 668 (10.4%) 3: 5316 (83.0%) 4: 398 (6.2%) 5: 0 |

1: 0 2: 252 (12.3%) 3: 1675 (81.9%) 4: 117 (5.7%) 5: 0 |

.006 |

1: 729 (0.6%) 2: 37,196 (30.6%) 3: 80,201 (66.0%) 4: 3289 (2.7%) 5: 44 (.04%) |

1: 64 (0.5%) 2: 3689 (28.7%) 3: 8,805 (68.5%) 4: 296 (2.3%) 5: 1 (.008%) |

< .001 |

| COPD (n, %) |

Yes: 3386 (1.7%) No: 195,789 (98.3%) |

Yes: 542 (2.3%) No: 23,023 (97.7%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 7530 (1.4%) No: 530,326 (98.6%) |

Yes: 972 (1.5%) No: 63,849 (98.5%) |

.03 |

Yes: 147 (2.3%) No: 6256 (97.7%) |

Yes: 30 (1.5%) No: 2014 (98.5%) |

.02 |

Yes: 1822 (1.5%) No: 119,637 (98.5%) |

Yes: 218 (1.7%) No: 12,637 (98.3%) |

.10 |

| Diabetes (n, %) |

Insulin: 25,494 (12.8%) Non-insulin: 41,827 (21.0%) None: 131,854 (66.2%) |

Insulin: 3,280 (13.9%) Non-insulin: 5,051 (21.4%) None: 15,234 (64.6%) |

< .001 |

Insulin: 33,885 (6.3%) Non-insulin: 88,208 (16.4%) None: 415,763 (77.3%) |

Insulin: 4,148 (6.4%) Non-insulin: 10,955 (16.9%) None: 49,718 (76.7%) |

.001 |

Insulin: 762 (11.9%) Non-insulin: 1,376 (21.5%) None: 4265 (66.6%) |

Insulin: 277 (13.6%) Non-insulin: 402 (19.7%) None: 1,365 (66.8%) |

.05 |

Insulin: 5830 (4.8%) Non-insulin: 13,360 (11.0%) None: 102,269 (84.2%) |

Insulin: 733 (5.7%) Non-insulin: 1543 (12.0%) None: 10,579 (82.3%) |

< .001 |

| Dialysis (n, %) |

Yes: 399 (0.2%) No: 198,776 (99.8%) |

Yes: 47 (0.2%) No: 23,518 (99.8%) |

.22 |

Yes: 2151 (0.4%) No: 535,705 (99.6%) |

Yes: 324 (0.5%) No: 64,497 (99.5%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 13 (0.2%) No: 6390 (99.8%) |

Yes: 2 (0.1%) No: 2402 (99.9%) |

.57 |

Yes: 2429 (0.2%) No: 119,030 (99.8%) |

Yes: 26 (0.2%) No: 12,829 (99.8%) |

.85 |

| Renal insufficiency (n, %) |

Yes: 1195 (0.6%) No: 197,980 (99.4%) |

Yes: 189 (0.8%) No: 23,376 (99.2%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 3227 (0.6%) No: 534,629 (99.4%) |

Yes: 454 (0.7%) No: 64,367 (99.3%) |

.07 |

Yes: 51 (0.8%) No: 6352 (99.2%) |

Yes: 14 (0.7%) No: 2030 (99.3%) |

.70 |

Yes: 607 (0.5%) No: 120,852 (99.5%) |

Yes: 64 (0.5%) No: 12,791 (99.5%) |

.54 |

| DVT (n, %) |

Yes: 3784 (1.9%) No: 195,391 (98.1%) |

Yes: 424 (1.8%) No: 23,141 (98.2%) |

.45 |

Yes: 8605 (1.6%) No: 529,251 (98.4%) |

Yes: 972 (1.5%) No: 63,849 (98.5%) |

.51 |

Yes: 134 (2.1%) No: 6269 (97.9%) |

Yes: 53 (2.6%) No: 1991 (97.4%) |

.15 |

Yes: 2915 (2.4%) No: 118,544 (97.6%) |

Yes: 308 (2.4%) No: 12,547 (97.6%) |

.88 |

| PE (n, %) |

Yes: 2589 (1.3%) No: 196,586 (98.7%) |

Yes: 330 (1.4%) No: 23,235 (98.6%) |

.13 |

Yes: 6454 (1.2%) No: 531,402 (98.8%) |

Yes: 778 (1.2%) No: 64,043 (98.8%) |

.77 |

Yes: 102 (1.6%) No: 6301 (98.4%) |

Yes: 33 (1.6%) No: 2011 (98.4%) |

.96 |

Yes: 2186 (1.8%) No: 119,273 (98.2%) |

Yes: 218 (1.7%) No: 12,637 (98.3%) |

.91 |

| GERD (n, %) |

Yes: 78,077 (39.2%) No: 121,098 (60.8%) |

Yes: 10,557 (44.8%) No: 13,008 (55.2%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 145,221 (27.0%) No: 392,635 (73.0%) |

Yes: 18,020 (27.8%) No: 46,801 (72.2%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 2113 (33.0%) No: 4290 (67.0%) |

Yes: 519 (25.4%) No: 1525 (74.6%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 51,620 (42.5%) No: 69,839 (57.5%) |

Yes: 5964 (46.4%) No: 6891 (53.6%) |

< .001 |

| Hypertension (n, %) |

Yes: 102,376 (51.4%) No: 96,799 (48.6%) |

Yes: 12,607 (53.5%) No: 10,957 (46.5%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 245,800 (45.7%) No: 292,056 (54.3%) |

Yes: 30,142 (46.5%) No: 34,679 (53.5%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 3278 (51.2%) No: 3125 (48.8%) |

Yes: 1,065 (52.1%) No: 979 (47.9%) |

.44 |

Yes: 49,434 (40.7%) No: 72,025 (59.3%) |

Yes: 5656 (44.0%) No: 7199 (56.0%) |

< .001 |

| Hyperlipidemia (n, %) |

Yes: 56,377 (28.3%) No: 142,798 (71.7%) |

Yes: 7093 (30.1%) No: 16,472 (69.9%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 117,252 (21.8%) No: 420,604 (78.2%) |

Yes: 14,260 (22.0%) No: 50,561 (78.0%) |

.12 |

Yes: 1594 (24.9%) No: 4809 (75.1%) |

Yes: 492 (24.1%) No: 1552 (75.9%) |

.47 |

Yes: 24,049 (19.8%) No: 97,410 (80.2%) |

Yes: 2777 (21.6%) No: 10,078 (78.4%) |

< .001 |

| Immunosuppressed (n, %) |

Yes: 3187 (1.6%) No: 195,988 (98.4%) |

Yes: 471 (2.0%) No: 23,094 (98.0%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 10,219 (1.9%) No: 527,637 (98.1%) |

Yes: 1231 (1.9%) No: 63,590 (98.1%) |

.43 |

Yes: 96 (1.5%) No: 6307 (98.5%) |

Yes: 43 (2.1%) No: 2001 (97.9%) |

.05 |

Yes: 2672 (2.2%) No: 118,787 (97.8%) |

Yes: 283 (2.2%) No: 12,572 (97.8%) |

.66 |

| Myocardial infarction (n, %) |

Yes: 2789 (1.4%) No: 196,386 (98.6%) |

Yes: 306 (1.3%) No: 23,259 (98.7%) |

.24 |

Yes: 5916 (1.1%) No: 531,940 (98.9%) |

Yes: 713 (1.1%) No: 64,108 (98.9%) |

.05 |

Yes: 89 (1.4%) No: 6314 (98.6%) |

Yes: 33 (1.6%) No: 2011 (98.4%) |

.46 |

Yes: 1700 (1.4%) No: 119,759 (98.6%) |

Yes: 193 (1.5%) No: 12,662 (98.5%) |

.35 |

| Cardiac surgery (n, %) |

Yes: 1992 (1.0%) No: 197,183 (99.0%) |

Yes: 236 (1.0%) No: 23,329 (99.0%) |

.75 |

Yes: 5378 (1.0%) No: 532,478 (99.0%) |

Yes: 583 (0.9%) No: 64,238 (99.1%) |

.008 |

Yes: 70 (1.1%) No: 6333 (98.9%) |

Yes: 14 (0.7%) No: 2030 (99.3%) |

.13 |

Yes: 1336 (1.1%) No: 120,123 (98.9%) |

Yes: 180 (1.4%) No: 12,675 (98.6%) |

.02 |

| PTC/PTCA (n, %) |

Yes: 4183 (2.1%) No: 194,992 (97.9%) |

Yes: 542 (2.3%) No: 23,023 (97.7%) |

.11 |

Yes: 9143 (1.7%) No: 528,713 (98.3%) |

Yes: 1102 (1.7%) No: 63,719 (98.3%) |

.96 |

Yes: 128 (2.0%) No: 6275 (98.0%) |

Yes: 35 (1.7%) No: 2009 (98.3%) |

.40 |

Yes: 2429 (2.0%) No: 119,030 (98.0%) |

Yes: 270 (2.1%) No: 12,585 (97.9%) |

.52 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea (n, %) |

Yes: 86,840 (43.6%) No: 112,335 (56.4%) |

Yes: 10,604 (45.0%) No: 12,961 (55.0%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 194,704 (36.2%) No: 343,152 (63.8%) |

Yes: 23,465 (36.2%) No: 41,356 (63.8%) |

.92 |

Yes: 2849 (44.5%) No: 3554 (55.5%) |

Yes: 903 (44.2%) No: 1141 (55.8%) |

.80 |

Yes: 28,421 (23.4%) No: 93,038 (76.6%) |

Yes: 3419 (26.6%) No: 9436 (73.4%) |

< .001 |

| Therapeutic anti-coagulation (n,%) |

Yes: 5577 (2.8%) No: 193,598 (97.2%) |

Yes: 825 (3.5%) No: 22,740 (96.5%) |

< .001 |

Yes: 14,522 (2.7%) No: 523,334 (97.3%) |

Yes: 1880 (2.9%) No: 62,941 (97.1%) |

.03 |

Yes: 218 (3.4%) No: 6185 (96.6%) |

Yes: 69 (3.4%) No: 1975 (96.6%) |

.99 |

Yes: 4251 (3.5%) No: 117,208 (96.5%) |

Yes: 488 (3.8%) No: 12,367 (96.2%) |

.09 |

n number, RYGB Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass, SG Sleeve Gastrectomy, BPD-DS Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch, and RBS Revisional Bariatric Surgery

aAnalyses are limited to patients with complete data for all variables

bSD, standard deviation

cNormally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed with Student’s t tests; categorical variables are presented as frequencies (%) and analyzed with chi-square test

Table 2.

Number of MBS performed annually by procedure type

| Year | SG (n) | RYGB (n) | BPD-DS (n) | RBS (n) | Total MBS/year | Total MBS + others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 86,878 | 37,604 | 1004 | 21,175 | 146,661 | 168,093 |

| 2016 | 101,416 | 37,744 | 1171 | 24,062 | 164,393 | 186,772 |

| 2017 | 111,385 | 38,434 | 1550 | 26,789 | 178,158 | 200,374 |

| 2018 | 114,461 | 38,741 | 2036 | 28,188 | 183,426 | 204,837 |

| 2019 | 112,917 | 40,356 | 2065 | 29,654 | 184,992 | 206,570 |

| 2020 | 99,141 | 37,152 | 1385 | 19,444 | 157,122 | 168,568 |

| Total 2015–2020 | 626,198 | 230,031 | 9211 | 149,312 | 1,014,752 | 1,135,214 |

n number, SG Sleeve Gastrectomy, RYGB Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass, BPD-DS Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch, RBS Revisional Bariatric Surgery, and MBS Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery

Between 2015 and 2019, there was an increase in the total number of bariatric procedures performed, with the number of cases rising from 146,661 to 184,992. This increase was seen in the number of SG (86,878 to 112,917), RYGB (37,604 to 40,356), BPD-DS (1004 to 2065), and RBS (21,175 to 29,654) cases performed. Despite the overall increase in the number of RYGB cases, the proportion of RYGB cases decreased from 22.4 to 19.5%. Meanwhile, the proportion of SG, RBS, and BPD-DS cases all increased from 51.7% to 54.7%, 12.6% to 14.4%, and 0.6% to 1.0%, respectively. When compared to 2019, in 2020, there was an overall decline in the number of bariatric procedures performed from 184,992 cases to 157,122 cases (Table 2).

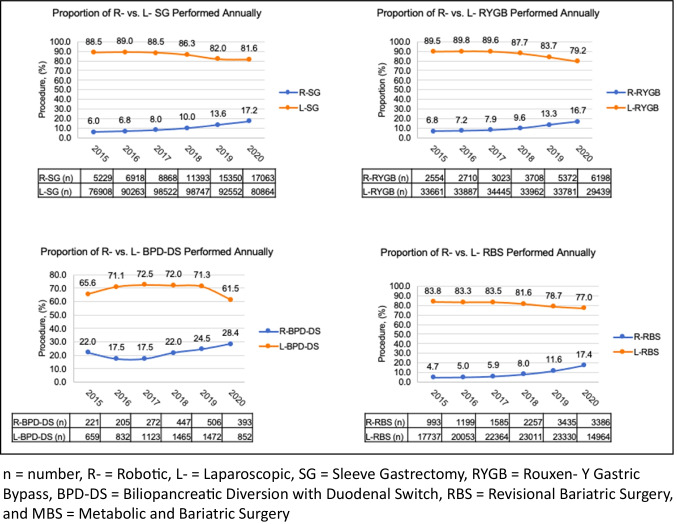

Figure 2 compares the proportion of cases performed robotically and laparoscopically for the years 2015–2020 divided by procedure type. Overall, the number of RYGB, SG, BPD-DS, and RBS cases performed robotically increased steadily between 2015 and 2020.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of R- vs. L- MBS performed annually

Between 2015 and 2020, the number of R-RYGB cases increased from 2554 to 6198 (6.8% to 16.7%), the number of R-SG cases increased from 5229 to 17,063 (6.0% to 17.2%), the number of R-RBS cases increased from 993 to 3386 (4.7% to 17.4%), and the number of R-BPD-DS cases increased from 221 to 393 (22.0% to 28.4%) (Fig. 2). To determine the average rate of growth observed among each type of bariatric procedure performed, annual slope was calculated. The greatest annual increase was observed among R-RBS (3.70-fold difference; slope 2.4% per year, 95% CI (1.0–3.8%)) and R-SG (2.87-fold difference; slope 2.2% per year, 95% CI (1.4–3.1%)). Of the 4 procedures analyzed, R-BPD-DS had the slowest rate of annual growth over the 5-year span (1.29-fold difference, slope 1.6% per year; 95% CI (− 0.5–3.7%)) (Table 3). Of note, the proportion of cases that were performed using an open approach is not included in Table 3; therefore, the summation of the proportions does not equal 100%.

Table 3.

Fold difference and annual slope of MBS performed for the years 2015 and 2020

| Procedure | Proportional use, % | Fold difference | Annual slope | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 2015 | Year 2020 | |||

| SG | 51.7 | 58.8 | 1.14 | |

| R-SG | 6.0 | 17.2 | 2.87 | 2.2% (95% CI 1.4–3.1%) |

| L-SG | 88.5 | 81.6 | 0.92 | |

| RYGB | 22.4 | 22.0 | 0.98 | |

| R-RYGB | 6.8 | 16.7 | 2.46 | 2.0% (95% CI 1.0–3.0%) |

| L-RYGB | 89.5 | 79.2 | 0.88 | |

| BPD-DS | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.33 | |

| R-BPD-DS | 22.0 | 28.4 | 1.29 | 1.6% (95% CI − 0.5–3.7%) |

| L-BPD-DS | 65.6 | 61.5 | 0.94 | |

| RBS | 12.6 | 11.5 | 0.91 | |

| R-RBS | 4.7 | 17.4 | 3.70 | 2.4% (95% CI 1.0–3.8%) |

| L-RBS | 83.8 | 77.0 | 0.92 | |

The proportions in summation do not equal 100% as the proportion of cases that were performed using an open approach is not included in the table

R Robotic, L Laparoscopic, SG Sleeve Gastrectomy, RYGB Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass, BPD-DS Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch, RBS Revisional Bariatric Surgery, CI Confidence Interval

Discussion

Recent ASMBS numbers using data from the BOLD, ACS/MBSAQIP, National Inpatient Sample dataset, and outpatient estimates have shown an increase in the number of bariatric surgeries performed annually [6]. Based upon the outcomes presented in our analyses, the overall increase in the number of bariatric surgeries performed between 2015 and 2019 was 1.23-fold. This increase can partially be attributed to the increased awareness of the metabolic sequela, physical burdens, and cognitive impairment associated with obesity, with surgery being an effective treatment strategy for those suffering from obesity. The rise in bariatric cases can also be attributed to the ASMBS’s focus on safety and key performance indicators. Surprisingly, there was a decline in the number of bariatric procedures performed in the year 2020 compared to 2019. This is contradictory to the upward trend observed up until the year 2019. Similarly, ASMBS estimates showed a decrease in the total number of bariatric cases from 256,000 cases in 2019 to 198,651 cases in 2020. The unexpected decline in cases is likely secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic which led to the halting of elective procedures across various hospital systems in the USA, including bariatric cases [7].

Interestingly, even though the total number of bariatric procedures being performed decreased in 2020, the use of the robotic platform continued to rise. As seen in our analyses, there was a consistent increase in the utilization of robotics over time for SG, RYGB, BPD-DS, and RBS. The annual growth slope for R-SG, R-RYGB, R-BPD-DS, and R-RBS was 2.2%, 2.0%, 1.6%, and 2.4%, respectively.

According to ASMBS estimates, SG accounted for the majority of the bariatric procedures performed between 2013 and 2020 [6]. Prior to 2013, RYGB was the most commonly performed bariatric procedure. Between 2013 and 2017, there was a slow steady decrease in the number of RYGB cases being performed. Between 2017 and 2019, the number of RYGB cases performed increased again. These numbers were calculated based upon aggregate data from the BOLD, ACS/MBSAQIP, and the National Inpatient Sample dataset, along with outpatient estimation datasets. Similarly, our data indicates that between 2015 and 2020, SG was the most commonly performed procedure. In addition, in our study and based on MBSAQIP data, RYGB saw a small decline from 22.4% in 2015 to 18.9% in 2018 but rose back to 22.0% by 2020. The renewed interest in RYGB cases in MBSAQIP-accredited centers is interesting and deserves further investigation. Our analysis also showed a steady increase in the adoption of the robotic platform over time. Of note, although R-BPD-DS case load per year showed a modest increase, the overall proportion of cases that are BPD-DS cases was extremely low at less than or equal to 1.0%.

The adoption of the robotic platform in bariatric surgery remains controversial because of concerns related to increased healthcare expenditures and the lack of clear clinical benefits related to outcome measures. Several studies have reported on the cost associated with the robotic approach in the field of bariatric surgery. Khorgami et al. in a retrospective analysis of the National Inpatient Sample demonstrated a high impact on cost of robotic-assisted procedures with an odds ratio of 3.6, CI 3.2–4.0 [8]. Bailey et al. further investigated the outcomes of RYGB in a systematic review and found no significant difference in minor and major complications between a R- and L- approach; however, the cost of a R- approach ($15,447) was greater than a L- approach ($11,956) [9]. More recently, Pokala et al. investigated both cost and outcomes for SG and RYGB between R- and L- approaches. In their retrospective analysis of the Vizient administrative database, they found no difference between overall complications, mortality, and 30-day readmission; however, the R- approach was associated with increased cost [10]. Our group has previously demonstrated using our institutional financial database that the adoption of a robotic approach in performing SG and RYGB is not cost-prohibitive and can be implemented without a significant increase in healthcare expenditures [11, 12]. Despite healthcare expenditure concerns, the increased adoption rates seen in this study reflect a certain level of interest among surgeons performing bariatric surgery.

Our findings related to the increase in the adoption rate of a robotic approach in the field of bariatric surgery is consistent with what was previously reported in general surgery. Sheetz et al. found that the availability of the robotic platform for general surgery cases correlated with a significant trend towards less laparoscopic general surgery being performed. Based upon their findings using a state specific registry, the use of laparoscopic general surgery decreased from 53.2% to 51.3%. Prior to the use of robotics, there had been a trend in increased utilization of laparoscopy as general surgeons converted from using an open surgical approach to a laparoscopic approach [13].

Two other retrospective studies similar to our analysis utilized the MBSAQIP PUF files to estimate the proportion of bariatric surgeries performed using a robotic approach [5, 14]. Tatarian et al. demonstrated that the proportion of robotic bariatric surgeries had risen from 6.7% in 2015 to 10.3% in 2018 [5]. Thomas et al. performed a similar study with results comparable to Tatarian et al., demonstrating a 1.96-fold increase in the number of robotic bariatric cases performed between 2015 and 2018 [14]. More recently, Morales-Marroquin et al. demonstrated that between 2015 and 2019, there was an increasing trend in robotic surgery that correlated with a decline in laparoscopy [15]. Although our findings are in line with what was previously reported, our study categorized all the commonly performed MBS procedures separately (SG, RYGB, RBS, and BPD-DS) and included more recent data by incorporating the 2020 PUF in order to see whether there is a difference in the adoption rates between the different procedures. According to our estimates, the largest fold difference in the adoption of robotic-assisted bariatric surgeries between 2015 and 2020 was seen in R-RBS cases (3.70-fold difference between 2015 and 2020) indicating that the interest in this new technology may be related to some of the advantages of the robotic approach including 3D visualization and articulating instruments, all of which may be helpful in overcoming the technical challenges more commonly encountered in RBS cases. However, R-SG had the second highest annual increase in proportional use (annual slope) indicating that R-SG may be currently utilized as an entry level case for training prior to performing more complicated anastomotic procedures.

Our study has several limitations. First, although based on the largest bariatric specific national database, this study is a retrospective study based on prospectively collected data which may result in errors related to the quality and accuracy of data entry. In addition, our study does not capture data from non-accredited bariatric centers or outpatient centers and does not include data on newly performed procedures like single anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy (SADI) or one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) which were reported in 2020 (488 and 1338 cases for SADI and OAGB according to ASMBS estimates). Second, the study is only a descriptive study of the trends in utilization. The study did not include any data about surgeon or patient-specific factors leading to the increased adoption rates. Lastly, given that a R- approach is coded in the MBSAQIP database as “robotic-assisted,” it is unclear whether those robotic cases were performed using a fully robotic approach or a hybrid approach where only one part of the procedure was performed robotically.

Conclusion

The data presented in our analyses demonstrates a nationwide increase in the utilization of a robotic approach in bariatric surgery. Given the concerns related to the potential increase in healthcare expenditures related to this novel technology, it is important to conduct further studies to establish well agreed upon key performance indicators comparing the robotic approach to the standard laparoscopic approach in conjunction with establishing guidelines for training, adoption, and utilization.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent does not apply.

Conflict of Interest

Wayne B. Bauerle, Pooja Mody, Allison Estep, and Jill Stoltzfus declare no competing interests. Maher El Chaar is a consultant at Intuitive Surgical and receives honoraria for lectures, presentations, and educational events.

Footnotes

Key Points

• The utilization rates of robotics in bariatric surgery are not well established.

• The greatest annual increase in robotic bariatric surgery was in revisional bariatric surgery.

• There is a nationwide increase in the use of a robotic approach in the field of bariatric surgery.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cadiere GB, Himpens J, Vertruyen M, et al. The world's first obesity surgery performed by a surgeon at a distance. Obes Surg. 1999;9(2):206–209. doi: 10.1381/096089299765553539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acquafresca PA, Palermo M, Rogula T, et al. Most common robotic bariatric procedures: review and technical aspects. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2015;9:9. doi: 10.1186/s13022-015-0019-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah J, Vyas A, Vyas D. The history of robotics in surgical specialties. Am J Robot Surg. 2014;1(1):12–20. doi: 10.1166/ajrs.2014.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vilallonga R, Fort JM, Gonzalez O, et al. The initial learning curve for robot-assisted sleeve gastrectomy: a surgeon's experience while introducing the robotic technology in a bariatric surgery department. Minim Invasive Surg. 2012;2012:347131. doi: 10.1155/2012/347131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tatarian T, Yang J, Wang J, et al. Trends in the utilization and perioperative outcomes of primary robotic bariatric surgery from 2015 to 2018: a study of 46,764 patients from the MBSAQIP data registry. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(7):3915–3922. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-07839-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011–2019: ASMBS; 2021 [Available from: https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers.

- 7.Singhal R, Tahrani AA, Sakran N, et al. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on global bariatric surgery PRActiceS - the COBRAS study. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2021;15(4):395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2021.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khorgami Z, Aminian A, Shoar S, et al. Cost of bariatric surgery and factors associated with increased cost: an analysis of national inpatient sample. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(8):1284–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey JG, Hayden JA, Davis PJ, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) in obese adults ages 18 to 65 years: a systematic review and economic analysis. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(2):414–426. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pokala B, Samuel S, Yanala U, et al. Elective robotic-assisted bariatric surgery: is it worth the money? A national database analysis. The American Journal of Surgery. 2020;220(6):1445–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King K, Galvez A, Stoltzfus J, et al. Cost analysis of robotic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in a single academic center: how expensive is expensive? Obes Surg. 2020;30(12):4860–4866. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-04881-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Chaar M, Gacke J, Ringold S, et al. Cost analysis of robotic sleeve gastrectomy (R-SG) compared with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (L-SG) in a single academic center: debunking a myth! Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(5):675–679. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2019.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheetz KH, Claflin J, Dimick JB. Trends in the adoption of robotic surgery for common surgical procedures. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(1):e1918911-e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scarritt T, Hsu CH, Maegawa FB, et al. Trends in utilization and perioperative outcomes in robotic-assisted bariatric surgery using the MBSAQIP database: a 4-year analysis. Obes Surg. 2021;31(2):854–861. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-05055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morales-Marroquin E, Khatiwada S, Xie L, et al. Five year trends in the utilization of robotic bariatric surgery procedures, United States 2015–2019. Obes Surg. 2022;32(5):1539–1545. doi: 10.1007/s11695-022-05964-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]