Abstract

Background

Globally, increasing coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccination coverage remains a major public health concern in the face of high rates of COVID-19 hesitancy among the general population. We must understand the impact of the determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake when designing national vaccination programmes. We aimed to synthesise nationwide evidence regarding COVID-19 infodemics and the demographic, psychological, and social predictors of COVID-19 vaccination uptake.

Methods

We systematically searched seven databases between July 2021 and March 2022 to retrieve relevant articles published since COVID-19 was first reported on 31 December 2019 in Wuhan, China. Of the 12,502 peer-reviewed articles retrieved from the databases, 57 met the selection criteria and were included in this systematic review. We explored COVID-19 vaccine uptake determinants before and after the first COVID-19 vaccine roll-out by the Food and Drug Authority (FDA).

Results

Increased COVID-19 vaccine uptake rates were associated with decreased hesitancy. Concerns about COVID-19 vaccine safety, negative side effects, rapid development of the COVID-19 vaccine, and uncertainty about vaccine effectiveness were associated with reluctance to be vaccinated. After the US FDA approval of COVID-19 vaccines, phobia of medical procedures such as vaccine injection and inadequate information about vaccines were the main determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

Conclusion

Addressing effectiveness and safety concerns regarding COVID-19 vaccines, as well as providing adequate information about vaccines and the impacts of pandemics, should be considered before implementation of any vaccination programme. Reassuring people about the safety of medical vaccination and using alternative procedures such as needle-free vaccination may help further increase vaccination uptake.

Keywords: Vaccine uptake, COVID-19, Vaccination, Hesitancy, Infodemics

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected communities worldwide, triggering public health interventions aimed at eradicating or reducing the transmission of COVID-19 [1]. The societal impacts of COVID-19 have been economic, social, and psychological [2], [3]. By the end of August 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) had recorded approximately 600 million confirmed cases and 6.5 million deaths due to COVID-19 worldwide [4].

Scientists have developed vaccines to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and reduce serious adverse events such as hospitalisation and death. As of November 2022, 50 COVID-19 vaccines had been approved for global use. In addition, approximately 850 COVID-19 vaccine candidates were undergoing clinical trials [5]. COVID-19 vaccines have been effective in reducing the spread of infection, severity of symptoms, and death [6], [7]. A high population uptake of vaccines can result in the achievement of a herd immunity threshold. A high uptake of effective vaccines, such as that for COVID-19, can lead to substantial reductions in infections [8], [9]. It is estimated that a COVID-19 vaccine with 95% and 80% efficacy will require 63% and 75% of the population, respectively, to be immune to achieve herd immunity against the infection [9], [10]. However, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy has been reported among various populations [11], [12], [13], including low- and middle-income countries where COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy tends to be higher [14]. Globally, by 17 October 2022, 4.98 billion people have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, accounting for 64% of the eligible vaccination population. Among them, 28.3% were from low-income countries [4]. Thus, given the benefits of vaccines and the COVID-19 vaccination prevalence rate, there is a need to investigate COVID-19 vaccine uptake and its associated determinants to increase the success rates of vaccinations globally.

Previous systematic reviews conducted before the start of the COVID-19 vaccination program found that factors related to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy included distrust in institutions, lower educational levels, age, female sex, being a healthcare worker, African-American ethnicity in the US, low-income levels, and the use of social media for sourcing COVID-19 information [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. There is also some evidence that there have been gradual attitudinal changes towards vaccine hesitancy in the general population [13], [24]. Furthermore, no systematic reviews of before-and-after studies (e.g. from the first roll-out of a COVID-19 vaccination program) have been conducted. Therefore, a review of the empirical literature is needed to shed light on the relevant patterns of COVID-19 vaccine-uptake intentions. We carried out a systematic review to explore health behaviours (e.g. vaccine uptake determinants and attitudes) and to determine whether these change over time [25], [26], [27], [28].

Methods

We conducted a systematic review to investigate attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and its determinants during the roll-out of global COVID-19 vaccination programmes. A previously registered protocol on PROSPERO (#CRD42021281769) guided this review. The review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [29]. We wished to understand temporal changes and therefore, for the purpose of this systematic review, Time 1 represents ‘before the first roll-out of the COVID-19 vaccine’ (prior to FDA approval: 11 December 2020), while Time 2 represents ‘after the first roll-out of the COVID-19 vaccine’.

Search terms and strategies

Seven databases were searched: PubMed, Medline and Embase (via Ovid), Scopus, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and CINAHL. Search strategies for the review were aligned to each database according to indexing terms, in addition to Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), truncations, and Boolean operators. Terms describing the concept of COVID-19 were used in each database, and phrases denoting vaccine uptake and intentions were also used in each database. A preliminary literature search began on 12 July 2021 and all searches were completed on 18 March 2022. Searches were not limited to any specific geographical location but were limited to human studies only. The search included studies published since the emergence of COVID-19 in 2019. See Appendix 1 for the specific search terms used for each database.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that explored the determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake based on quantitative nationwide surveys were included in this review. Thus, the included studies surveyed national populations (i.e. either representative or non-representative sample sizes) of at least 100 participants aged 18 years and over. The included studies were required to report the reliability of the non-binary scales used in the study. Only English-language publications were included in this analysis.

Exclusion criteria were applied to cross-national comparison studies (i.e., between-country studies), as we intended to provide country-specific evidence. Studies that used only a defined population characteristic (e.g. health workers or students only) and studies that provided only descriptive findings of COVID-19 vaccine uptake rates were also excluded. No gray literature (such as reports, speeches, and newsletters) was added to the selected papers.

Screening

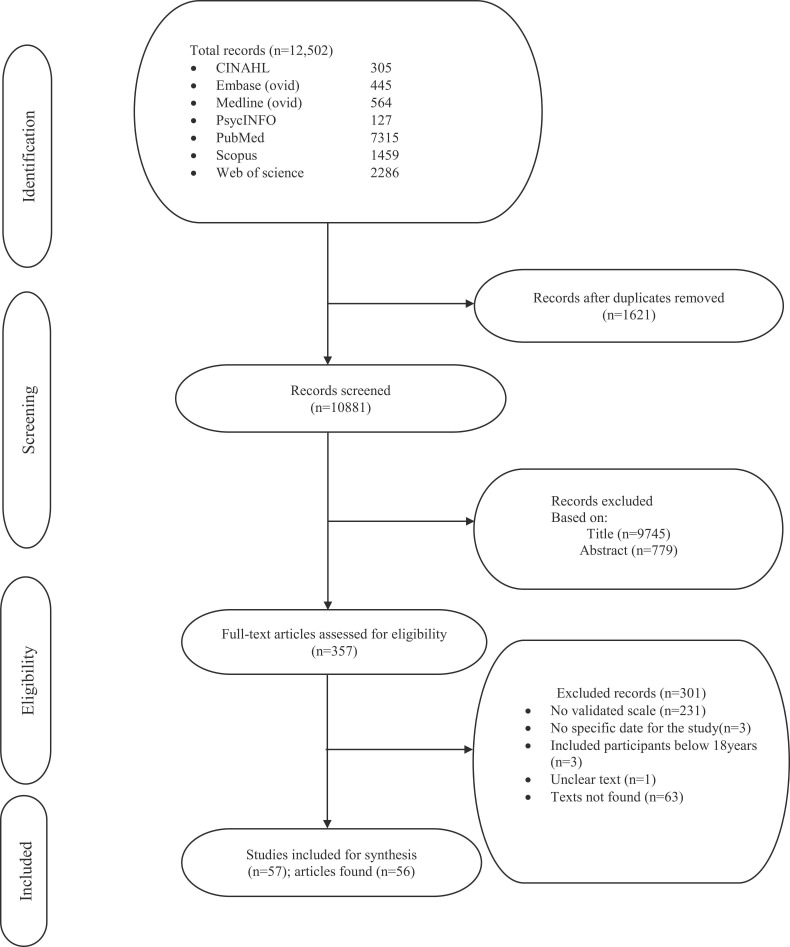

Papers containing search words were extracted from seven databases and imported into Endnote version 20, and duplicates were removed ( Fig. 1). The initial data screening was performed by the first author (PA). The titles of the articles were first screened to identify those relevant to the determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake (Fig. 1). This was followed by screening of abstracts and sample/method sections based on the study design and nationwide studies. The full texts of the articles identified at this stage were screened independently by two authors (PA and JM) to determine their eligibility based on the inclusion criteria of the review (Fig. 1). Disagreements between the two authors (PA and JM) on a paper [30] were resolved by a third investigator (CS).

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart for the systematic review.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data from the studies used in the current review were extracted independently by two authors (PA and JM). Data were extracted under the following headings: author, year, aim, country, study period, sample size, study design, scales and reliabilities, number of participants, recruitment method, and results ( Table 1). Data quality was assessed by two authors using an adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for cohort studies (Table 1). The quality of the studies ranged from unsatisfactory to good, with 17 (30%) of the 57 studies appraised as unsatisfactory, 31 (54%) as satisfactory, and 9 (16%) as good (Table 1). Major quality issues included inadequate information on sample justification and statistical power and study results that did not adjust for relevant predictors, risk factors, or confounders.

Table 1.

Summary of included nationwide studies for before-and-after the approval of COVI-19 vaccine by FDA.

| BEFORE FIRST COVID-19 VACCINE APPROVAL (Time 1) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No |

Author (s)Name/Country |

Aim of study |

Study design / Participants’ recruitment method/ Sample size/ Study date. |

Main outcome of the study |

Measures & Reliabilities/ Quality assessment scores |

||||

| Domains |

|||||||||

| Uptake Rates | Demographic Predictors | Psychological Predictors | Social Predictors | Infodemics | |||||

| 1 | Abu et al. (2021) Jordan |

To evaluate the perception and hesitant attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccine and the reasons associated with such hesitancies. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique Between July and August 2020 -Sample size: 1287 |

-Religiosity | -Desire for natural supplements, COVID-19 vaccine adverse side effect, and previous experience with COVID-19. | -Lack of information on COVID-19 -Financial cost related to the access of COVID-19 vaccine |

All measures (α = 0.88) 5point: Satisfactory |

||

| 2 | Al Halabi et al. (2021) Lebanon |

To assess the intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and factors associated with vaccine refusal. | -Cross-sectional survey using Self-administered questionnaire through Snowballing sampling was conducted from November to December 2020. -Sample size: 579 |

-40.9% hesitancy rate -37.7% were neutral, and 21.4% acceptance rate. |

-Gender, marital status predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Self-developed vaccine hesitancy questions (α = 0.84), fear of COVID-19 scale (α = 0.87), knowledge on COVID-19 (α = 0.90), attitudes towards COVID-19 (α = 0.83), practice about COVID-19 (α = 0.89). 3ponts: Unsatisfactory |

|||

| 3 | Alawadhi et al. (2021) Kuwait |

-To evaluate the determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among both citizens and non-citizens | -Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique from May to September 2020. -Sample size: 724. |

-67% agreed to take COVID-19 vaccine. | - Gender, age educational levels, income levels, marital status, and being a health worker. | - Knowledge of COVID-19 self-protection perception, following recommendation from authorities, being able to correctly recognize COVID-19 protective measures, previous experience with COVID-19 and influenza vaccine, and risk perception towards influenza infections, confidence in the media, doctors, hospitals, or the ministry of health, trust in government policies, engaging in more panic behaviours, and expression of fear and worries. | -Engaging in protective measures, informing oneself about COVID-19, | -Knowledge question on treatment, transmission, transmission route, incubation, and immunity (α = 0.6), correct preventive measures questions (α = 0.7). -Taking preventive measures (α = 0.80), panic (α = 0.70), and fear (α = 0.70) 5points: Satisfactory |

|

| 4 | Ansari-Moghaddam et al. (2021) Iran |

Identify predictors of COVID-19 vaccine intentions using protection motivational theory. | -Web-based cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique during the month of June 2020. -Sample size: 265 |

Perceived severity, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived response efficacy. | -Perceived susceptibility (α = 0.93), perceived severity (α = 0.77), and perceived response efficacy (α = 0.85) 3points: Unsatisfactory. |

||||

| 5 | Baeza-Rivera et al. (2021) Chile |

To assess predictors of COVID-19 vaccination intent. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique in December 2020 -Sample size: 1033 |

-Greater belief about vaccine effectiveness, and injunctive norms regarding self-care measures | Beliefs about vaccine effectiveness (a=0.86), conspiracy belief about COVID-19 (a=0.89), and injunctive norms (a=0.88) 5points: Satisfactory |

||||

| 6 | Cerda et al. (2021) Chile |

To identify refusal and hesitancy factors regarding COVID-19 vaccine. | -Online cross-sectional survey through snowball and convenience sampling techniques was conducted during August and September 2020. -Sample size: 370 |

-77% acceptance rate 28% were undecisive. - 28% acceptance rate when side effects were unknown, and 44% rejection rate. |

Gender, younger age, and education | - Side effects of COVID-19 vaccine, risk perception regarding COVID-19, lack of knowledge of COVID-19 vaccines, preferences for others to be vaccinated first, COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness concerns, perception protection of COVID-19 of oneself and others, perceived benefit of COVID-19 vaccine, increase perception of the severity of COVID-19, and previous experience of COVID-19. | Health believed model components questionnaire (a=0.757). 5points: Satisfactory |

||

| 7 | Chu and Liu (2021) USA |

-To examine five set of heath behaviour theories variables, how these variables influence individuals’ intentions to receive COVID-19 vaccine. | Online cross-sectional survey using a convenience sampling technique during late September 2020. Sample size: 934 |

-Fear of COVID-19, perceived community benefit and positive attitudes towards COVID-19, stronger safety concerns, beliefs about COVID-19 vaccine and barriers to getting COVID-19 vaccine, positive attitudes towards COVID-19, and having had previous vaccination | -Perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 (a=0.74), perceived severity of COVID-19 (a=0.92, fear of COVID-19 (a=0.96), attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines (a=0.98), perceived individual benefits of COVID-19 vaccines (a=0.91), perceived community benefit of COVID-19 vaccines (a=0.85), perceived barriers to getting COVID-19 vaccine (a=0.88, self-efficacy (a=0.77, vaccine hesitancy (a=0.98, COVID-19 vaccine intentions (a=0.98). 7points: Good |

||||

| 8 | Earnshaw et al. (2020) USA |

To explore the relationship between COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and intentions to receive COVID-19 vaccine. | Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique during April 2020. Sample size: 845 |

-Women and less educated individuals were less likely to receive COVID-19 vaccine. | -Believed in conspiracies | -Compliance to public health recommendation (a=0.84) support for COVID-19 public policies (a=0.93), medical mistrust (a=0.88). 5points: Satisfactory |

|||

| 9 | El-Elimat et al. (2021) Jordán. |

-To assess COVID-19 vaccine acceptability and attitudes predictive factors. | Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique through snowballing, conducted in November 2020. Sample Size: 3100 |

-37.4% acceptance rate, 36.3% hesitancy rate, and 26.3% uncertainty rate. | -Age, employment status, and gender | Trust in COVID-19 information and vaccines, having taken influenza vaccine before, trust in the safety of COVID-19 vaccine, willingness to pay for COVID-19 vaccine | -Believe that COVID-19 pandemic is a conspiracy | Self-developed attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines scale (a=0.6). 6points: Satisfactory |

|

| 10 | Graffigna et al. (2020) Italy |

To investigate the role of health engagement, perceived COVID-19 susceptibility and severity, and the general attitudes towards vaccines on willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine. | -Cross-sectional survey using random and stratified sampling techniques somewhere in May 2020). -Sample size: 1004 |

-58.6% acceptance rate | -General attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccine, perceived severity and perceived susceptibility and health engagement. | Health engagement scale ((a=0.75). 4points: Unsatisfactory. |

|||

| 11 | Guillon and Kergall (2021) France |

To examine the relationship between COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination intention. |

-Online survey using quota sampling technique, conducted in November 2020. -Sample Size: 1146 |

60.6% hesitancy rate and 25% acceptance rate. |

-Male gender, and smokers | -Previous vaccination history, COVID-19 vaccine concerns about safety, perceived good health, COVID-19 risk perception, perceived vaccine efficacy, trust in institutions, and willingness to take risk in the health domain. | -COVID-19 perceived threat (α = 0.67), perceived benefits of COVID-19 vaccination (α = 0.92). perceived barriers to COVID-19 vaccination (α = 0.81), trust in institutions (α = 0.78). conspiracy beliefs (α = 0.84), risk preferences (α = 0.71). 5 points: Satisfactory |

||

| 12 | Head et al. (2020) USA |

To address public intention to accept COVID-19 vaccine and determine the factors associated COVID-19 vaccine uptake. |

-Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique in the month of May 2020. -Sample size: 3159 |

Education, employment in healthcare sector, political orientation | -Low-commitment altruism, perceived threat to physical health, belief in the problematic nature of COVID-19 in community worry had positive relation with an intent to vaccinate against COVID-19. | Behavioural intention items (a=0.91), altruism scale: high commitment altruism((a=0.83), low commitment altruism (a=0.81), COVID-19 related worry (a=0.82), perceived severity of COVID-19 (a=0.706). 5points: Satisfactory. |

|||

| 13 | Irfan et al. (2022) Pakistan |

To investigate factors responsible for public intention to get COVID-19 vaccine, and how these factors shape intentions to get COVID-19 vaccine. | Face-to-face cross-sectional survey using random sampling sampling technique was conducted in November and December 2020. Sample size: 900 |

-Attitudes towards COVID-19, risk perception of the pandemic, and perceived benefits of COVID-19 vaccine positively related with intentions to get COVID-19 vaccine. | -Vaccine cost and unavailability of vaccine negatively impacted COVID-19 vaccination intentions. | -Attitudes about COVID-19 (a=0.90), environmental impact of COVID-19 (a=0.80), Cost of COVID-19 (a=0.89), risk perception of COVID-19 (a=0.9), perceived vaccine benefits (a=0.94), unavailability of vaccine (a=0.92,), intention to get COVID-19 (a=0.82). 6points: Satisfactory |

|||

| 14 | Jackson et al. (2021) UK |

To examine attitudes towards vaccination in general and the relationship between smoking status and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19 pandemic. | Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique, conducted in September and October 2020. Sample Size: 29148 |

Types of smokers | -Mistrust of vaccine benefit (α = 0.96), worries about unforeseen future effects (α = 0.77), concerns about commercial profiteering (α = 87), preference for natural immunity (α = 0.89). 6points: Satisfactory. |

||||

| 15 | Kourlaba et al. (2021) Greece |

-To determine the association of socio-demographic factors, clinical factors, as well as knowledge, attitudes, and practices and COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Mix method study design was conducted using random sampling and stratified sampling techniques during the months of April and May 2020. -Sample size: 1004 |

-57.7% acceptance rate, 26.0% unwillingness rate, and 16.3% were unsure. | -Age, marital status, employment status, belonging to a vulnerable group or having a family member belonging to a vulnerable group, having no children. | -Correct knowledge regarding transmission of COVID-19 routes and appropriate control and prevention measures, believe in the contagious nature of COVID-19 and the importance of herd immunity, previous experience with flu vaccination. | -Sources of information. | -Disbelieve in conspiracy about COVID-19, believing that COVID-19 is a biological weapon, | Knowledge about COVID-19 (a=0.58). 6points: Satisfactory. |

| 16 | Latkin et al. (2021) USA |

To assess the impact of social norms on COVID-19 vaccine intention. | -Online longitudinal survey using convenience sampling technique from March to July 2020. -Sample size: 592 |

-59.1% acceptance rate, 16.7% neutral and 24.2% unwillingness rate. | - Black race, educational level, more political conservative ideology, gender. | - No prior experience with influenza vaccine, COVID-19 scepticism, perceived social norms of preventive behaviours, less trust in information from CDC, trust in information from white house, perception of contracting COVID-19 - |

-Observance of COVID-19 preventive | -COVID-19 scepticism (a=0.85), descriptive social norms of perception of peers` concern about COVID-19(a=0.77). 5points: Satisfactory. |

|

| 17 | Malik et al. (2020) USA |

-To assess determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance willingness. | -Online cross-sectional survey recruiting participants through Cloud Research platform. The study was conducted in May 2020. -Sample size: 672 |

-67% reported willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine. | -Gender, age, race, education, employment status, and geographic location. |

- Previous experience with influenza vaccine uptake related with lower intentions to accept COVID-19 vaccine. | Perceived risk scale (a=0.72). 6points: Satisfactory. |

||

| 18 | Marchlewska et al. (2022) Poland |

Study 1: To examine the relationship between different national identity and COVID-19 vaccination attitudes. Study 2: replicate study 1 and to assess the effect of identification with all humanity and COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Online survey recruiting participants through random sampling technique. The study was conducted in March 2020. -Sample size: 432 (study1) -Sample size: 807(study2) |

Study 1: 51% acceptance rate. |

-Gender | Study 1: -National narcissism, and national identification. Study 2: -National narcissism, national identification, and Identification with all humanity. |

Study 1: -Conspiracy belief Study 2: -Conspiracy belief |

Study 1: -National narcissism (α = 0.92, national identification (α = 0.90), COVID-19 Conspiracy belief (α = 0.93) Study 2: -National narcissism (α = 0.95), national identification (α = 0.93), COVID-19 vaccine conspiracy beliefs (α = 0.92), dentification with all humanity (α = 0.94) 6points: Satisfactory. |

|

| 19 | Mercadante et al. (2020) USA |

To access the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on flu vaccine intention, and assess vaccine intention using the Health Behaviour Model (HBM) | Online cross-sectional survey through convenience sampling technique during the month of October 2020. Sample size: 525 |

-Age, race, and education. | -Knowledge on the importance of flu vaccine, and perceived benefits vaccines. | -5 C scale (a=0.749). and CoBQ (a=0.636), and scales Combined (a=0.765). 8points: Good. |

|||

| 20 | Ouyang et al. (2022) China (Mainland) |

To explore the prevalence and factors associated COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. | Online cross-sectional survey through convenience sampling technique during the month of April 2020. Sample size: 1004 |

-Age, income, health information literacy, and frontline workers | -information from media, frequency of social media use, and diversity of social media use | -Vaccine hesitancy scale (α = 0.60) media trust (α = 0.78), health information literacy (α = 0.78), and lack of confidence in COVID-19 vaccine (α = 0.78). 5points: Satisfactory |

|||

| 21 | Pivetti et al. (2021) Italy |

To investigate the relationship between COVID-19 related conspiracy beliefs and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance behavioural intentions. | -Online cross-sectional survey through convenience sampling technique was conducted during April-May 2020. - Sample size: 590 |

- | -Faith in science, and general attitudes towards vaccines predicted attitudes towards COVID19 vaccine uptake | -Conspiracy belief, and COVID-19 related conspiracy . |

-Moral purity (a=0.58), faith in science (a=0.82), conspiracy belief (a=0.78), COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs (0.86), attitudes towards vaccines (a=0.92), attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccine (a=0.93). 7points: Good. |

||

| 22 | Prati (2020) Italy |

To examine intentions to receive COVID-19 vaccine. -To determine factors associated with vaccine acceptance willingness. |

Online cross-sectional survey using virtual snowballing sampling technique was conducted in April 2020. Sample size: 624 |

-75.8% acceptance rate, -5.1% unwillingness rate, and 10.1% were uncertain |

-Low levels of worries and institutional trust related with no intention of receiving COVID-19 vaccine. | Institutional trust (a=0.78). 4points: Unsatisfactory |

|||

| 23 | Rahman et al. (2021) Bangladesh |

To explore COVID-19 vaccine demand, hesitancy, and nationalism, vaccine uptake and domestic vaccine preferences. | -Online survey using snowballing sampling technique was conducted from October to December 2020. -Sample size: 1018 |

-Vaccine nationalism, vaccine demand, (Prioritizing one’s country for vaccination) related COVID-19 vaccine uptake. |

-Vaccine demand (a=0.70), vaccine hesitancy (a=73), vaccine nationalism (a=0.90). 6points: Satisfactory |

||||

| 24 | Reiter et al. (2020) USA |

To explore COVID-19 vaccine acceptability related variables. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique was conducted during the month of May 2020. - Sample size: 2006 |

69% acceptance rate, and 31% hesitancy rate. | -Income levels, having private health insurance, liberal political learners, and gender | -Previous experience with COVID-19, perceived risk of getting COVID-19 in the future, perceive severity of COVID-19, and perceived effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccine. | -Recommendation of COVID-19 vaccine by health provider. | -Belief that COVID-19 vaccine is harmful. | Stigma associated with COVID-19 (a=0.75). 5points: Satisfactory. |

| 25 | Roberts at al. (2022) USA |

To identify the role of political attitudes, personality, mental health, and substance use on anti-vax attitudes and vaccine hesitancy. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique was conducted during the month of September and October 2020. - Sample size: 1004 |

-Age, income, gender, ethnicity, education, and political orientation | -COVID-19 related stress/worry, and experience of fewer negative impact of COVID-19. | -Higher approval of President Trump job, and adherence to COVID-19 safety behaviours. | -Anti-vax scale (a=0.79), extraversion (a=0.71), agreeableness (a=0.76), conscientiousness (a=0.78), negative emotionality (a=0.85), open-mindedness (a=0.68), mental health (a=0.93), problematic social media use (a=0.88), liberal and conservative social attitudes (a=0.92), COVID-19 related safety behaviours (a=0.81), COVID-19 Stress/worry (a=0.92). 4points: Unsatisfactory |

||

| 26 | Sethi et al. (2021) UK |

To identify factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | Cross sectional online survey through convenience sampling technique was conducted in Septeigmber and October 2020. -Sample size: 4884 |

79.3% acceptance rate. 13.86% were unsure, and 6.9% hesitancy rate. | -Education gender, age, ethnicity, and smokers |

-Overall, vaccine hesitancy increases as the perceived vaccine effectiveness decreases. | -Overall questionnaire was (a=0.91) 5points: satisfactory. |

||

| 27 | Shih et al. (2021) USA |

To estimate differences in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance by generation. | -Online cross-sectional survey using Convenience sampling technique was conducted in March 2020. -Sample size: 713 |

-Baby Boomers generation, millennials generation, race/ethnicity, income, political affiliation. | -Increase perceived risk was also associated with decrease COVID-19 vaccine rejection, this association was more significant among Baby Boomers generation compared to Millennials generation. | -Vaccine hesitancy scale (a=0.89). 6points: Satisfactory |

|||

| 28 | Shmueli (2021) Israel |

To identify attitudes and beliefs relating to COVID-19 vaccine. To determine factors, motivators and barriers resulting in decisions to receive COVID-19 vaccination. | Web-based survey through convenience sampling technique was carried out during the months of May and June 2020. Sample size: 398 |

-80% were willing to accept COVID-19 vaccine. | Gender, and education | -Having received influenza vaccine previously, perceived benefits, cues to action, perceived severity, subjective norms, and self-efficacy, |

-Perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 (a=0.83). perceived severity of COVID-19 (a=0.73), perceived benefits of COVID-19 vaccines (a=0.87), cues to action (a=0.79), health motivation (a=0.759, subjective norms (a=0.86). 5points: satisfactory |

||

| 29 | Trzebinski et al. (2021) Poland |

To investigate how assumption about the world, meaning in life, and life satisfaction relate with attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination. | -Online longitudinal survey through convenience sampling technique was carried out during the first half of December 2020 (study1). -Sample size: 266 |

Study 1: -Life satisfaction correlated positively with willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19, and assumption about the positivity of the world increase COVID-19 vaccination intention when orderliness view of the world is low. |

-Basic hope scale (a=0.882): orderliness (a=0.812), positivity (a=0.807), meaning of life scale (a=0.887), life satisfaction scale (a=0.888, and perceived vaccination safety scale (a=0.763). 3points: Unsatisfactory. |

||||

| 30 | Wang et al. 2021 Korea |

To investigate the moderation role of conspiracy beliefs in health belief model and psychometric paradigm and preventive actions and vaccination intention. | Web-based survey using quota sampling technique was carried out during the months of August 2020 Sample size: 1524 |

-Gender, age, low education, high income, having large number of children, conservative ideology, and self-rated poor health | -COVID-19 prevention related self-efficacy negatively predicted COVID-19 vaccination intention. | -COVID-19 preventive actions, media exposure positively predicted COVID-19 vaccination intention. | -Preventive actions (a=0.93), vaccination intention (a=0.65), belief in conspiracy theories (a=0.85), perceived susceptibility (a=0.76), perceived severity (a=0.78), perceived barriers (a=0.50), perceived benefit (a=0.56), self-efficacy (a=0.87), exposure to media (a=0.60), risk perception (a=0.86), benefit perception (a=0.81), trust in government (a=0.86), trust in experts (a=0.45), trust in science (a=0.75), and negative affect (a=0.91), and knowledge (a=0.84). 8points: Good |

||

| AFTER FIRST COVID-19 VACCINE APPROVAL (Time2) | |||||||||

| No. | Author(s)Name/Country | Aim of study | Study design / Participants’ recruitment method/ Sample size/ Study date. | Main outcome of the study | Measures & Reliabilities. | ||||

| Domains | |||||||||

| Uptake Rates | Demographic Predictors | Psychological Predictors | Social Predictors | Infodemics | |||||

| 1 | Ahmed et al. (2021) Somalia |

To investigate adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures and acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convivence sampling technique between later December to late January 2021 -Sample size: 4543 |

-76.8% of the participants agreed to receive COVID-19 vaccine. | Concern about vaccine being effective, fear of bad side effect of COVID-19 vaccine, confidence in strong immune system and the notion that COVID-19 is over in Somalia. | belief that COVID-19 vaccine may contain substances derived from pigs. | -Adherence scale (α = 0.67). 3points: Unsatisfactory |

||

| 2 | Alibrahim et al. (2021) Kuwait |

To explore the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and evaluate general attitudes towards a vaccine, and examine predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convivence sampling through snowballing was conducted from March to April 2021 -Sample size: 1147 |

-73.8% acceptance rate. - |

-Marital status, gender, age, residence, smoking status, and income. | -Concerns about side effect and safety of COVID-19 vaccine, concern about COVID-19 vaccine efficacy, concerns about the fast development of COVID-19 vaccine COVID-19, no worries about catching COVID-19, negative attitudes towards vaccine benefits, desire for natural immunity, concerns abouts commercial profiteering of COVID-19 vaccine, attitudes towards previous vaccines, and lack of adequate information about COVID-19 |

-Trust of vaccine benefit (a=0.93) -Worries about vaccine effect (a=0.79) -Concerns about commercial profiteering (a=0.79) -Preference for natural immunity (a=81) -Full scale (a=0.89). 5points: Satisfactory |

||

| 3 | Al-Qerem et la. (2022) Iraq |

To assess COVID-19 vaccine uptake variables and reasons for COVID-19 vaccination hesitancies. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convivence sampling technique between May and July 2021 -Sample size: 1765 |

-88.6% of participants were willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19. | -Income, and education, | -Concerns about side effect and safety of COVID-19 vaccine related with hesitancy attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccine, perceived seriousness of COVID-19 related with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, and lack of adequate information about COVID-19 vaccine and rigor in testing the vaccine related with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. | -Practice towards COVID-19 (a=0.80), COVID-19 Knowledge (a=0.59) 4points: unsatisfactory |

||

| 4 | Al-Rawashdeh et a. (2022) Jordan |

To examine predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Online cross-sectional survey through Snowballing sampling technique was conducted in the month of January 2021 -Sample size: 281 |

-Females gender was unwilling to accept COVID-19 vaccine compared to males. | -Perceived better health status compared with perceived poor health status related negatively with COVID-19 uptake, and perceived adequate measures of the government regarding controlling the pandemic, perceived susceptibility and severity of COVID-19, and attitudes towards COVID-19 related positively with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Intention to vaccinate (a=0.94), perceived susceptibility and severity of COVID-19 (a=0.92), COVID-19 knowledge (a=0.75), and COVID-19 attitudes (a=0.77). 3points: unsatisfactory |

|||

| 5 | Alwi et al. (2021) Malaysia |

To investigate the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among the general population. | Online cross-sectional survey through Snowballing sampling technique was conducted late December 2020. Sample size: 1411 |

-83.3% acceptance rate, and 16.7% were hesitant to take COVID-19 vaccine. - |

-Ethnicity, religion, age, race, marital status, income levels, current residence, and having chronic illness. | -Concerns about the side effects of COVID-19 vaccine, safety, lack of information on COVID-19, belief in traditional remedies, and fear of injection. | - COVID-19 vaccine concern questionnaire (a=0.6) | ||

| 6 | Babicki et al. (2021) Poland |

To assess the effect of vaccination on mental well-being, attitudes regarding adherence to government recommendations about limiting viral transmission, and factors associated with intentions to vaccinate against COVID-19. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convivence sampling technique between March and April 2021 -Sample size: 1677 |

-98.9% participants were willing to accept COVID-19 vaccine. | -Rural residence, low education, divorced, non-health workers, income levels predicted COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. | -Anxiety regarding COVID-19 infection related with willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19. - Previous experience with COVID-19 infection, previous experience with COVID-19 infection related with willingness to vaccinate. |

-Adherance to government recommendations related with unwillingness to vaccinate against COVID-19. | -Generalised anxiety disorder (a=0.92), quality of life (a=0.85). 5points: Satisfactory |

|

| 7 | Belsti et al. (2021) Ethiopia |

To investigate the willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine. | -Population-based online survey using Convenience sampling technique through snowballing during February to March 2021. -Sample size: 1184 |

-31.4% of acceptance rate, and 47.32% hesitancy rate, and 21.31% were unsure of receiving the vaccine. |

-Gender, age marital status, place of residence, private sector worker, education, non-healthcare worker, affiliation to orthodox religion. | -Knowledge regarding the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccine, supporting the idea that vaccination increase autoimmune diseases believing in the impossibility of reducing incidence of COVID-19 without the help of vaccination, believing in the fair distribution of COVID-19 vaccine, and perceiving that COVID-19 vaccine has side effects. |

Overall questionnaire (a=0.70). 5points: Satisfactory. |

||

| 8 | Benis et al. (2021) USA |

To investigate attitudes towards vaccination and identify attributes affecting COVID-19 vaccination. | Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique in the December 2020 Sample size: 1728 |

73.8% acceptance rate. | -Males and ethnic minority, -higher risk group, having greater number of children, and those with higher education. |

The desire to protect one’s family and relatives, agreeing to the view that vaccination is a civic responsibility, fear of being infected with COVID-19, high confidence in healthcare systems and providers, and pharmaceutical industry. | Reasons to take and recommend COVID-19 vaccine (a=0.76) 6points: Satisfactory |

||

| 9 | Castellano-Teje et la. (2021) Spain |

To explore psychological factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convivence sampling technique was conducted from January to March 2021 -Sample size: 300 |

-27.85% hesitancy rate, 6.71% resistant, 65.44% acceptance rate | -Age, and healthcare professionals predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Self-perceived correctness of performing COVID-19 preventive measures, belief in the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccine and security, belief that the vaccine will put an end to the pandemic, high confidence in the vaccine, fear of COVID-19, previous experience with COVID-19, and caring for a vulnerable individual. | -COVID-19 fear (a=0.85) -Anxiety (a=0.90). 4points: unsatisfactory |

||

| 10 | Domnich et al. (2022) Italy |

To evaluate the attitudes regarding COVID-19 and flu vaccines, to quantify hesitancy rates and factors associated with acceptance of these vaccines. | -Online longitudinal cross-sectional survey using stratified random sampling technique was conducted in October and November 2021 -Sample size: 2463 |

- 85.1% acceptance rate | -Gender and age predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Belief in vaccines as being safe, crucial for public health, and the view that COVID-19 variants contiguous to emerge related with willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine, and previous vaccination history (flu), and willingness to pay for flu vaccine related with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | All Measures (full scale) (a=0.83). 8points: Good |

||

| 11 | Fernandes et al. (2021) Portugal |

To examine individuals’ willingness to self-vaccinate and their children. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convivence sampling technique was conducted from January to March 2021 -Sample size: 649 |

-63% acceptance rate, | -Knowledge about COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccine, concerns about the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccine, positive beliefs and attitudes, perceived risk of COVID-19 were the predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake | -Following healthcare professionals’ recommendation | -Perceived threat to COVID-19 (a=0.58) -Trust in management of COVID-19 (a=0.84). 3points: Unsatisfactory |

||

| 12 | Freeman et al. (2021) UK |

To test effectiveness of messaging by hesitancy level and several sociodemographic factors. To test mediation of any effects by beliefs about COVID-19 vaccination. | Online Random Control Trial was conducted using quota sampling technique in the month of January and February 2021. Sample size: 18841 |

-66.1% acceptance rate, 15.6% of were doubtful, and 18.4% hesitant. |

-Types of information predicted COVID vaccine willingness. | Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (a=0·98), collective importance (a=0.88), speed of development- (a=0.85), self-efficacy (a=71) COVID-19 vaccine side effect (a=0.78). 9points: very Good. |

|||

| 13 | Freeman et al. (2021) UK. |

-To determine prevalence of blood-injection-injury fears and its relation with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. | Online cross-sectional survey using quota sampling technique was conducted from January-February. 2021. Sample size: 15014 |

-13.8% were hesitant towards COVID-19 vaccine. | -Age predicted vaccine hesitancy when fear of injection was controlled for. -Income levels were associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy attitudes. |

-Fear of injection related with higher levels of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy when all demographic factors are controlled, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was associated with specific phobia, medical fear, and injection fear, blood injection injury fear accounted for about 10% vaccine hesitancy among adult population. | -Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (a=0.97), specific Phobia Scale (blood-injection-injury) (a=0.94), medical fear survey (injections and blood) (a=0.90). 8points: Good |

||

| 14 | Gan et al. (2021) China |

Investigating willingness to receive COVID-19 and its associated factors. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convivence sampling technique was conducted in October and November 2021 -Sample size: 1009 |

-60.4% acceptance rate, 7.1% were unwilling, and 32.5% were unsure. | -Education and age related positively with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Trust in the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19, perception of COVID-19 incidence, and previous vaccination history (flu) predicted COVID-19 vaccine intentions. | - Paying attention to information about COVID-19 predicted COVID-19 vaccine intentions. | -Knowledge about COVID-19 (a=0.41), hygiene habits (a=0.59). 5points: Satisfactory. |

|

| 15 | Hassain et al. (2021) Bangladesh |

To assess the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its associated factors. | -Face-to-face and online survey using snowball and quota sampling technique were conducted in February 2021 -Sample size: 1497 |

-46.2% expressed hesitancy attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination. | -Religion, and place of residence related with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Poor adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures predicted COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy attitudes. | -Vaccine hesitancy scale (a=0.83), COVID-19 preventive behaviours (a=0.86), Knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine (a=0.64), Knowledge about vaccination process (a=0.77, COVID-19 vaccine conspiracy (a=0.72), attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccine (a=0.74), perceived susceptibility (a=0.66), perceived severity (a=0.61), perceived benefits (a=0.84), and perceived barriers (a=0.70). 8points: Good |

||

| 16 | Karabela et al. (2021) Turkey |

To investigate the association between perceived causes of COVID-19, attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccine and levels of trust regarding infodemics information source | -Online cross-sectional survey using cluster sampling technique was conducted during the month of February 2021 - Sample size: 1216 |

54% of the acceptance rate, and 16% hesitancy rate, and 30% were indecisive. | -As age increases attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccine decreases | -Information from YouTube, reliance on WhatsApp information, information from government institution, health professionals, newspapers, television, significant others | -Increased perception of conspiracies and faith factors | -Perception of causes of COVID-19 Scale (PCa-COVID-19), conspiracy theories (a=0.96), environmental factors (a=0.85), faith factors (a=0.90) 6points: Satisfactory. |

|

| 17 | Khunchandani et al. (2021) USA |

To assess the impact of COVID-19 infection in social network on COVID-19 vaccination willingness. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convivence sampling technique was conducted in June 2021 -Sample size: 1602 |

-89% acceptance rate, and 11% not willing to accept COVID-19 vaccine. | -Ethnicity, place of residence, education marital status, political orientation related with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Previous experience with COVID-19 associated with COVID-19 vaccine willingness. | Previous experience with COVID-19. (a=0.79). 7points: Good |

||

| 18 | Lo et al. (2021) Taiwan |

To understand the relationship between mental models and COVID-19 vaccine willingness. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convivence sampling technique was conducted in April 2021 -Sample size: 1100 |

Gender | Sources of vaccine recommendation predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | Belief in both artificial origin of COVID-19 related with COVID-19 vaccination intention. | Powerlessness. (a=82). 4points: Unsatisfactory |

||

| 19 | Maciuszek et al. (2022) Poland |

To investigate the relation between declared intention to vaccinate and the actual vaccination uptake. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convivence sampling technique was conducted from February to August 2021 -Sample size: 918 |

-Fear of side effects, distrust for COVID-19 vaccine producing companies, safety concerns and effectiveness, the desire of helping to stop the pandemic, the belief that vaccines are effective to prevent diseases and return to normal life, and concern about the fast development of COVID-19 vaccine. | -Reason for refusal scale for Time 1: (a=0.80), reason for refusal scale for Time2 (a=0.74, reason for COVID-19 acceptance scale: Time 1 (a=0.91), reason for COVID-19 acceptance scale Time 2 (a=0.96). 5points: Satisfactory |

||||

| 20 | Patwary et al. (2021) Bangladesh |

To identify factors of COVID-19 acceptance or hesitancy using the theory of planned behaviour and health behaviour model. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique was conducted in July and August 2021 -Sample size: 543 |

85% acceptance rate. | -Body size, smoking habits, age, and schooling. | -Fear of side effect of the vaccine, doubt about the effectiveness, susceptibility to COVID-19, perceived high severity of COVID-19, greater benefits of vaccination, possessing high cues to actions, stating greater subjective norms, self-efficacy, previous experience with vaccination, greater trust and satisfaction with health authorities, high levels of perceived barriers, and preference for natural immunity. | Possessing COVID-19 related information correlated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Satisfaction with health authorities (a=0.72, perceived susceptibility (a=0.92), perceived severity (a=0.61), perceived benefits (a=0.79), perceived barriers (a=0.76), cues to actions (a=0.72, subjective norms (a=0.89). 5points: Satisfactory. |

|

| 21 | Pang et al. 2021 China |

To explore the effect of information framing on COVID-19 vaccination intentions. | -Online survey using convenience sampling technique was conducted from March to April 2021 -Sample size: 280 |

-Gender, and education predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake | -Higher understanding of COVID-19 infection, perceived effectiveness of the vaccine positively predicted COVID-19 vaccination intention, and risk disclosure had the greatest impact COVID-19 vaccination intention. | Compliance with government COVID-19 prevention and control measures. | Framing messages (two groups) (a= 91) and (a=0.90). 3points: Unsatisfactory |

||

| 22 | Santirocchi et al. (2022) Italy |

To examine the rate of COVID-19 vaccination; and the demographic and psychological factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. | -Online cross-sectional survey using snowballing sampling technique was conducted from March to May 2021 -Sample size: 971 |

-3.6% hesitancy rate, 78.5% acceptance rate | -Gender, marital status, age, and education predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -COVID-19 vaccine uptake correlated with perceived risk of COVID-19, pro-sociality, fear of COVID-19, use of preventive behaviours, trust in government, trust in science, and trust in medical professional. | Misinformation negatively related with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Intention to be vaccinated (a=0.88, perceived Risk (a=0.62, fear of COVID-19 (a=0.86), use of, preventive behaviours (a=0.92). 5points: Satisfactory |

|

| 23 | Schmitz et al. (2022) Belgium |

Study1: To examine which motivational factors contribute to individuals’ intention and actual behaviour to take COVID-19 vaccine. |

Study1: Online longitudinal cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling technique was conducted from December to May 2021 -Sample size: 8887 |

Age, and levels of education related with intentions to vaccinate against COVID-19 vaccine uptake. | -Controlled motivation, distrust-based amotivation, and effort-based amotivation, andemic-related health concerns, infection-related risk perception and autonomous motivation, distrust-based amotivation, and effort-based amotivation | Pandemic-related health concerns (a=0.66; a=0.67), infection-related risk perception (a=0.63; a=0.71), autonomous motivation (a=0.94; a=0.71, controlled motivation (a=0.69; a=0.74), distrust-based amotivation (a=0.91; a=0.90), effort-based amotivation (a=0.79; a=0.78) 5points: Satisfactory |

|||

| 24 | Seboka et al. (2021) Ethiopia |

To assess willingness to pay for COVID-19 vaccine, the demand and intent to vaccinate against COVID-19. | Online cross-sectional survey using convenience and snowballing sampling techniques was conducted between February-March 2021. Sample size: 1160 |

46.55% acceptance rate, 32.7% were unsure, and 20.69% hesitancy rate. | -Gender, and age | -Previous experience with COVID-19, perceived susceptibility, concern about COVID-19 vaccine safety, and desire that more people should be vaccinated first. | -Affordability of vaccines correlated with higher levels of uncertainty and unwillingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine. | -Perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 (a=0.72), perceived severity of COVID-19 (a=0.84), perceived benefits of COVID-19 vaccines (a=0.53), perceived barriers and cues to action (a=0.71). 4points: Unsatisfactory |

|

| 25 | Trzebinski et al. (2021) Poland |

To investigate how assumption about the world, meaning in life, and life satisfaction related with attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination. | -Online longitudinal survey through convenience sampling technique was carried out during middle of January 2021 -Sample size: 266 |

Study 2: - Life satisfaction, orderliness assumption of the world tends to reduce the positive impact of positivity assumption on willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine. |

-Basic hope scale (a=0.875): orderliness (a=0.809), positivity a= 0.775), life satisfaction scale (a=0.884), perceived vaccination safety scale (a=0.775). 3points: Unsatisfactory |

||||

| 26 | Xiao et al. (2021) China |

To explore psychosocial factors responsible for COVID-19 vaccination willingness. | -Online cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling through snowballing technique was conducted in January 2021 -Sample size: 2528 |

-44.2% reported COVID-19 hesitancy rate, and -55.8% reported COVID-19 acceptance rate. |

Gender, place of residence, and age. | - Side effects of COVID-19 vaccine, self reported health status, high response efficacy to vaccination (e.g., Vaccine protects me and my family), high self-efficacy regarding successful vaccination against COVID-19 predicted COVID-19 vaccination intentions. | -Protection Motivation Theory constructs (a=0.80), perceived susceptibility (a=0.86), perceived Severity (a=0.80), response efficacy (a=0.83), self-efficacy (a=0.73), and response cost. (a=69). 6points: Satisfactory |

||

| 27 | Zheng et al. (2022) USA |

To evaluate factors influencing COVID-19 vaccination intention | Online cross-sectional survey using quota sampling method was conducted in February 2021 Sample size: 800 |

-Education, income, general health status, age, and gender. | -Perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 side effect, and knowledge about COVID-19. | -Perceived susceptibility (a=0.86), perceived severity (a=0.86), vaccination intention (a=0.94), doctor-patient communication (a=0.92). 4points: Unsatisfactory |

|||

Data analysis

The features of all studies are summarised, including the determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake (Table 1). Researchers were unable to conduct a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of the measurement of COVID-19 vaccine determinants (i.e., some studies used dichotomous measures and others used scales); hence, data was described narratively. Predictive factors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake were grouped under four broad headings: demographic, social, psychological, and infodemic (false or misleading information in digital and physical environments during the breakout of a disease) [31].

Results

Overall, 12,502 articles were identified from seven databases. After removing duplicates, 10,881 articles were screened by title and abstract, and 357 articles were identified. Finally, 57 articles met the inclusion criteria after screening the full text of the selected articles (see flow chart for details: Fig. 1). To reiterate, the use of the COVID-19 vaccine uptake only reflects intentions or willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine.

Characteristics of the selected studies

Most (97%) of the studies included in our review employed a web-based recruitment method for data collection [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85]. Only one study used a face-to-face data collection method, and one used both face-to-face and web-based data collection methods [86]. In terms of study design, four studies used a longitudinal survey design [39], [87], one used an experimental design [88], one employed a mixed-methods study design [49], and 52 employed a cross-sectional study design [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [89], [90], [91] (refer to Table 1). Eleven studies were undertaken in the US [44], [45], [48], [51], [52], [55], [67], [75], [84], [87], [92]; four in the UK [36], [56], [81], [88]; five in Italy [47], [53], [54], [64], [73]; four in China [66], [71], [74], [93]; three each in Poland [39], [62], [69], [82] and Bangladesh [86], [94]; two each in Jordan [60], [78], Ethiopia [34], [38], Kuwait [42], [61] and Chile [76], [89]; and one each in Malaysia [33], Somalia [32], Lebanon, Turkey [37], Greece [49], India [95], Israel [58], Iraq [59], Taiwan [68], Spain [63], Portugal [96], Pakistan [97], Belgium [91], Iran [98], France [80] and South Korea [85].

After the completion of the search and screening process, it was seen that 30 of the 57 studies (40, 41, 43–59, 73, 77, 79, 81–83, 85, 86, 93, 94, 98, and 99)were conducted during Time 1, and 27 studies (33–40, 60–65, 67–70, 72, 74–76, 87, 92, 95, and 97) were undertaken during Time 2. Notably, one study [39] met the criteria for the both timelines (i.e., two studies were presented in a single paper: Study 1 was conducted during Time 1 and Study 2 during Time 2); hence, this study was included for both time periods.

COVID-19 vaccine uptake/hesitancy rates

The COVID-19 vaccine uptake rates from the 31 studies for Time 1 ranged from 21.4% [40] to 73.8% [92], whilst hesitancy rates ranged from 5.1% [54] to 74.0% [80]. Notwithstanding, for Time 2, the 27 studies found uptake rates ranging from 46.6% [38] to 98.9% [62], and hesitancy estimates ranged from 5.6% [73] to 47.3% [34].

Demographic determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake

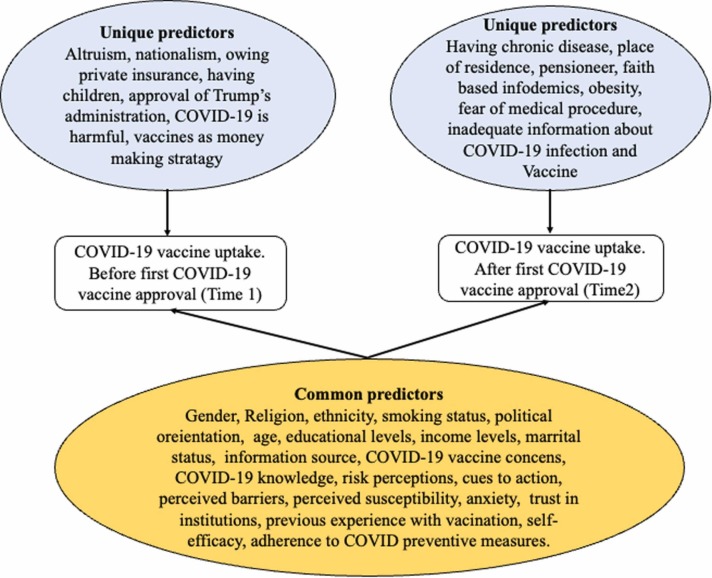

For both time periods, 17 studies that compared women vs. men reported that men were more likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccine [40], [42], [45], [46], [51], [55], [60], [61], [64], [71], [73], [74], [75], [80], [82], [84], [87]; however, in four studies, women were more likely to accept the COVID-19 vaccine [38], [74], [85], [92]. Older age was associated with increased COVID-19 vaccine uptake compared to younger age [34], [37], [49], [51], [52], [56], [63], [73], [74], [75], [84], [85], [89], [91], [94], [99], and this result was stable across the time periods, with six studies reporting higher uptake in younger age groups [38], [42], [46], [61], [64], [93]. Across both periods, 18 studies found that education levels correlated positively with COVID-19 vaccine uptake [34], [45], [48], [51], [52], [56], [58], [59], [62], [66], [67], [73], [75], [84], [87], [89], [91], [92]. A negative relationship with education level was observed in studies conducted in Kuwait, Korea, and China during Time 1 [42], [71], [85]. During Times 1 and 2, studies conducted in the US and UK found that compared to ethnic majority groups, ethnic minorities (e.g. Black or Asian ethnicity) were hesitant towards the COVID-19 vaccine [51], [52], [56], [87], but in other studies in the USA, people of Asian ethnicity were more willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine [51], [67], [85], [92]. These results were observed across both the time periods. Most studies have found that income is positively associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake [55], [59], [61], [62], [75], [84], [85] during both periods. Two studies conducted in China and Kuwait reported a negative relationship between income and COVID-19 vaccine uptake [42], [93] during Time 1. For marital status, results were consistent for both times, with single people (i.e. not married, widowed, or divorced) being more willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine compared to those who were married [33], [34], [40], [42], [73]. The reverse was also found in Poland and Kuwait, as single people were more hesitant than married people about the COVID-19 vaccine [61], [62] during Time 2 (Table 1). In Bangladesh and Kuwait, non-smokers compared with smokers [61], [94] were found to be hesitant towards the COVID-19 vaccine during Time 2. In the UK, during Time 1, smokers, when compared with non-smokers, were found to be hesitant towards the COVID-19 vaccine [81]. Urban residence compared with rural residence was a predictor of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance during Time 2 [34] but was associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy during Time 1 [61], [62], [86]. In the US, identifying as liberal was associated with the highest intent to be vaccinated against COVID-19 compared to those who were identified as moderate and conservative [48], [55], [67], [85], [87] for both time periods. Self-reported health was unrelated to COVID-19 vaccine uptake during both periods [60], [74], [75], [80], [85]. Similarly, being in a vulnerable group or having a family member belonging to a vulnerable group did not impact the COVID-19 vaccine uptake [49], [63], [92]. Four studies reported religious affiliation as a significant predictor of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [32], [33], [34], [78]. One study found that having no children [49], and two studies found that having children [85], [92] predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake during Time 1 only. During Time 1, having private health insurance [55] was associated with vaccine uptake. During Time 2, chronic disease, being a pensioner, or being obese was associated with a tendency to refuse the COVID-19 vaccine [33], [94] (Table 1).

Psychological predictors of COVID-19 uptake

Concerns regarding the fast development, safety, negative side effects, commercial profiteering, and the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine were common psychological factors negatively associated with its vaccine uptake at Times 1 and 2 [32], [33], [34], [38], [42], [46], [47], [48], [53], [54], [55], [59], [61], [64], [66], [69], [71], [74], [75], [76], [78], [86], [89], [94], [96], [97], [100]. Fear, anxiety, panic, and worries regarding COVID-19 were positively related to vaccine uptake during both time periods [62], [63], [84], [92]. Another variable found to be a common positive predictor during the two time periods was knowledge regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, including its preventive measures and a COVID-19 vaccine [34], [39], [42], [44], [63], [75], [85], [86], [89], [96], [101]. Trust in science, COVID-19 information sources, government institutions, preventive measures against the COVID-19 pandemic, health professionals, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, and the media were found to correlate positively with COVID-19 vaccine uptake for both time periods [42], [46], [53], [54], [60], [73], [80], [87], [92], [94]. However, in China, media trust negatively predicted COVID-19 uptake at Time 1 [93]. Researchers have found that perception of the severity of COVID-19 infection [42], [47], [55], [58], [59], [60], [85], [94], [102] and perceived susceptibility to the pandemic [38], [47], [48], [55], [60], [61], [85], [94], [102] were positive predictors of vaccine uptake for both periods. Overall, risk perception towards COVID-19 infection and influenza infections [42], [73], [80], [85], [87], [91], [96], [97] and perceived benefits of COVID-19 vaccine [42], [52], [58], [94], [97] were notable variables found to be directly linked with vaccine uptake for both periods.

Additionally, the following factors were common positive predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake for both Times 1 and 2: self-efficacy, confidence in receiving the COVID-19 vaccine without any side effects [58], [74], [78], [85]; life satisfaction and a positive view of the world [39]; health engagement; belief in the importance of herd immunity [47], [49]; and concerns about the safety of relatives and friends; and society [69], [73], [74], [92]. However, less self-efficacy in preventing the infection negatively predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake in a study conducted in Bangladesh during Time 2 [94]. During both times, desire for natural immunity, confidence in having a strong immune system, and belief in traditional remedies as a cure for COVID-19 were found to be associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [32], [33], including the desire for others to be vaccinated first [38], [42].

During both periods, previous experience of COVID-19 infection was positively associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake [38], [55], [61], [62], [63], [67], [89]. Likewise, 10 studies reported that intention to vaccinate against COVID-19 was higher among participants with previous experience with vaccination, including influenza vaccination, compared to those with no or minimal vaccination history [44], [46], [49], [51], [52], [58], [64], [66], [87], [94]. Fear of medical procedures (e.g. blood injury and injection phobia) [33], [88], ‘assuming that the world is in order’ [39], and lower perception of COVID-19 incidence [66] were found to predict COVID-19 hesitancy during Time 2. Positive predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake also included the view that vaccination is a civic responsibility, COVID-19 pandemic-related health concerns, national identification with all humanity, and vaccine nationalism (i.e. prioritising one’s country for vaccination), while national narcissism, controlled motivation, distrust-based amotivation, and effort-based amotivation negatively predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake [72], [91], [92].

Social predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake

Information from the mass media, official national websites, government institutions, health professionals, newspapers, national television, YouTube, and significant others (e.g. family and friends) positively predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake [49], [85], [103] for both time periods. However, in China, the frequency of social media use, reliance on information from WhatsApp, and using different social media were negatively correlated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake at Time 1 [93], [103]. In the US, information from the White House during 2019–2021 and higher approval of President Trump were associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy during Time 1 [84], [87] (Table 1).

Moreover, calls to action, such as recommendations from government authorities and health professionals, were directly related to COVID-19 vaccine uptake during the two timelines [42], [55], [58], [62], [71], [96]. Another common positive predictor of COVID-19 vaccine uptake for both periods was being informed about preventive measures and required adherence to these measures [42], [49], [64], [84], [86], [87]. In Jordan and Bangladesh, willingness to pay for the COVID-19 vaccine predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake for both time periods [46], [72], [85]. Perceiving COVID-19 preventive measures as a social norm related both positively [58] and negatively [94] to COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Israel and Bangladesh, respectively, for both time periods. Notwithstanding, five studies reported that barriers to vaccine access (e.g. cost) were directly linked to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [44], [85], [86], [94], [97].

Seven studies indicated that inadequate information regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine negatively predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake [32], [33], [59], [61], [69], [71], [94]. However, in an experimental study, hesitant participants exposed to collective information on COVID-19 by researchers tended to be willing to accept COVID-19 vaccine [88]. Notably, these findings were peculiar to the Time 2 period. Finally, altruistic behaviours were linked directly with COVID-19 vaccine uptake for Time 1 [48] (Table 1).

COVID-19 Infodemic predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake

Common infodemics, specifically the belief that COVID-19 is a biological weapon or a myth, correlated negatively with COVID-19 vaccine uptake at both Times 1 and 2 [32], [37], [45], [46], [50], [73], [82]. In one study, the reverse of this relationship was reported at Time 2 [37]. Belief that the COVID-19 pandemic is a strategy for big pharma to make money, caused by 5 G mobile networks, and that the COVID-19 vaccine is harmful predicted less willingness to be vaccinated for COVID-19. These factors were notable at Time 1 (46, 47, 54, 55, and 88). Nonetheless, during Time 2, not believing in the existence of COVID-19 and the belief that the COVID-19 vaccine contained substances derived from animals such as pigs was related to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [32]. Paradoxically, religious faith factors, such as ‘the pandemic is humanity’s destiny, were related to positive intentions to accept the COVID-19 vaccine [37]. (see Fig. 2 for a summary of all the identified predictors in this review).

Fig. 2.

A pictorial representation of the determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake for before-and-after the first approval of COVID-19 vaccine by FDA.

Discussion

We found that there tended to be more COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy prior to the first FDA approval of a COVID-19 vaccine (Time 1) than after (Time 2). Attitudes aligning with acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine also increased over time, representing a positive move towards vaccination. We found that people were concerned about the rapid development of the COVID-19 vaccine, its safety, side effects, and its effectiveness. These factors were reported consistently across both time periods by 27 studies conducted across five continents (Africa, Asia, North and South America, and Europe) and were found to be negatively related to COVID-19 vaccine uptake during both time periods.

Our findings were similar to those of previous studies on influenza vaccine uptake [89], [104], [105]. Previous studies found higher levels of anxiety, fear, and worry to be positive predictors of influenza vaccine uptake [106]. In agreement with other studies (e.g.[104, 107, 108], perception of the risk of COVID-19 infection and perceived benefit of COVID-19 vaccine were found to correlate positively with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Likewise, COVID-19 information from health professionals, government institutions, and other social media (e.g. national websites) was related to COVID vaccine uptake for both time periods. These findings were similar to those of studies on influenza vaccines and other pandemic vaccine uptake studies conducted in the US [105], [109]. Our review found evidence that previous experience with vaccination predicts the willingness to accept a vaccine [107]. Specifically, previous experiences of both COVID-19 infection and influenza vaccination were positively related to COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Cues to action (e.g. recommendations from professionals), being informed about COVID-19 preventive measures, and adherence to these measures were positively associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. That is, respondents who followed such health behaviours might have positive attitudes towards health behaviours in general, including vaccination [110]. Studies of influenza vaccine uptake intentions have reported self-efficacy as one of the determinants of influenza vaccine uptake [110], and our review of COVID-19 vaccine uptake provided additional evidence to support such a relationship.

Infodemics have been reported to impede vaccine uptake in different populations globally [111]. The COVID-19 infodemics identified in this review were also negatively associated with the COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Paradoxically, religious faith in COVID-19 infodemics was positively correlated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake. A possible reason for this could be that religious bodies sensitised individuals to the need to be vaccinated against COVID-19 to facilitate their ritual activities as the pandemic halted many religious gatherings worldwide.

Another unique factor found to predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy after FDA approval was fear of medical procedures (e.g. injection), which is in line with findings from general vaccination programs in India [112]. An underestimated perception of COVID-19 incidence, that is, participants might have lost focus on the pandemic, perhaps due to lack of or ignoring information available from different media, could have lessened the desire or urgency to vaccinate against the pandemic. Studies also indicated that inadequate information regarding both COVID-19 infection and the vaccine related to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. This finding will be of interest to relevant stakeholders, especially as it occurred after the first roll-out of the COVID-19 vaccine. In addition, nationalism (e.g. national narcissism) and certain types of motivation have been found to predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

Common demographic factors linked to COVID-19 vaccine uptake included sex, marital status, age, education, area of residence, and religious affiliation. Religious affiliation was found to show specific relationships in terms of predicting COVID-19 vaccine uptake because religious affiliation negatively predicted COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Jordan, Somalia, Malaysia, and Ethiopia, which is consistent with previous literature [113]. In terms of sex, the majority of the studies reviewed supported previous studies suggesting that males were more likely to accept a vaccine than females [114].

To the best of our knowledge, this systematic review is the first to explore the determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake across two time periods. This timely exploration of differences in the trends of COVID-19 vaccine uptake determinants provides an overview to stakeholders about attitudinal changes occurring over time since the emergence of COVID-19. Again, the selection of studies that were assessed for quality ensured an adequate level of accuracy and confidence in our findings. However, our review has the following limitations. Most of the studies were cross-sectional surveys. Caution concerning the interpretation of our results should be taken, as we were unable to determine causation between the variables. Qualitative studies and studies published in languages other than English were excluded from the review because of the time and cost involved.

The global aim of achieving high uptake of a COVID-19 vaccine could be achieved if specific concerns associated with vaccine hesitancy, such as safety, effectiveness, potential side effects, and benefits related to COVID-19 vaccines, including disbeliefs and adequate information about the pandemic, are clearly communicated and understood. Addressing the difference in pre- and post-first FDA approval of COVID-19 vaccine determinants is important for policymakers to understand the factors that emphasise current COVID-19 vaccination programs. Infodemics were additional factors in this regard which were associated with hesitancy attitudes. A strategy found to help address misinformation is psychological inoculation (i.e. exposing individuals to a version of already known information, which they can refute) [115]. Again, since phobia of medical procedures was found to contribute to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy after FDA approval, clinicians may consider dealing with medical procedure phobias by considering different administration routes of COVID-19 vaccines, for example, needleless injection procedures to increase COVID-19 vaccine coverage. This seems to be an important predictor given that 69% of participants (participating in an influenza survey) opted for a needleless route of administration [116]. Finally, a standardised method of measuring COVID-19 vaccine uptake will help ensure precision in the future, as most of the studies measured uptake dichotomously, which limits accuracy and makes it difficult to compare studies on COVID-19 uptake; hence, measuring COVID-19 vaccine uptake using a well-validated scale may help increase the measurement precision of COVID-19 uptake.

Our study identified 30 [39], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [72], [76], [78], [80], [81], [82], [84], [85], [92], [93], [97], [98] and 27 studies [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [66], [67], [68], [69], [71], [73], [74], [75], [86], [91], [92], [94], [96] for Time 1 and Time 2 respectively. Over time, our review found that COVID-19 uptake rates tended to increase, with COVID-19 vaccine concerns, sources of information, and cues to actions being common predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Specifically, nationalism and inadequate information about COVID-19 were unique predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake prior to FDA approval. After FDA approval, phobia of medical procedures, such as fear of injection, was one of the main determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Future national research studies should investigate other predictors of health behaviour, such as the COVID-19 vaccine uptake literature, which is limited. Future studies should explore certain psychological factors, such as mindfulness, self-compassion, and affective symptoms (e.g. anxiety) as potential predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake. It is possible that intentions or willingness may not lead to actual behaviours; therefore, investigation of the factors that lead to COVID-19 vaccine uptake behaviours may help increase COVID-19 uptake. Finally, studies focusing on regions known to have high vaccine hesitancies, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, are limited.

Research in context

By the end of August 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) had recorded approximately 600 million cases of COVID-19 infections and 6.5 million consequent deaths worldwide. Vaccines are an effective means of reducing the spread of infection and preventing diseases, for example, by achieving the herd immunity threshold. However, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy has been reported among various populations globally, particularly in resource-poor countries.

To understand this phenomenon, we reviewed materials published between July 2021 and March 2022. We searched PubMed, MEDLINE(Ovid), Web of Science, Embase (Ovid), Scopus, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and dimensions for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies relevant to COVID-19 vaccine uptake intentions published in English since COVID-19 was reported on 31 December 2019 in Wuhan, China.

This novel review explores the determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake since the emergence of COVID-19. We distilled the evidence with regard to demographic, psychological, social, and infodemic determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake, focusing on studies involving national populations in different countries. We identified common COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy determinants, such as concerns regarding COVID-19 vaccine safety, negative side effects, fast development of COVID-19 vaccine, and uncertainty about vaccine effectiveness, as well as country-specific predictors. We also assessed real-world evidence of factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy both before and after FDA approval, such as phobia of medical procedures and inadequate information about vaccines and the pandemic.

Implications

This review informs clinicians and stakeholders about the most relevant predictors of COVID-19 vaccine uptake that should be considered to enhance vaccination success. Specifically, campaigns should consider concerns surrounding COVID-19 vaccine such as information about vaccines and pandemics and safety of vaccination procedures to increase COVID-19 vaccination coverage.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Appendix 1.