Abstract

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) channels are multi-modally activated cation permeable channels that are expressed most organ tissues including the skin. TRPV4 is highly expressed in the skin and functions in skin resident cells such as epidermal keratinocytes, melanocytes, immune mast cells and macrophages, and cutaneous neurons. TRPV4 plays many crucial roles in skin homeostasis to affect an extensive range of processes such as temperature sensation, osmo-sensation, hair growth, cell apoptosis, skin barrier integrity, differentiation, nociception and itch. Since TRPV4 functions in a plenitude of pathological states, TRPV4 can become a versatile therapeutic target for diseases such as chronic pain, itch and skin cancer.

1. Introduction

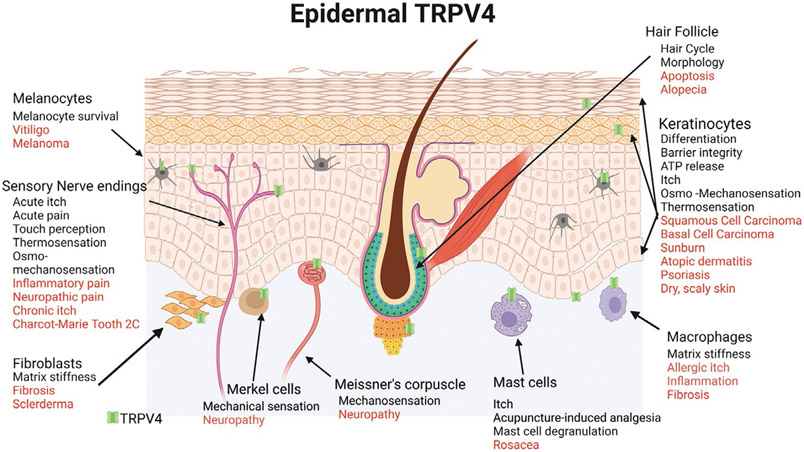

The surface epithelium, the epidermis of skin provides barrier protection against dehydration and the potentially harmful external environment (Fuchs, 2009; Patapoutian, 2005; Roosterman et al., 2006; Tominaga & Caterina, 2004). The epidermis also assumes an underappreciated sensory and sentinel function as a “frontline sensor” of a potentially harmful environment (Fuchs, 2009). TRPV4 belongs to a family of transmembrane non-selective calcium permeable ion channels, TRP channels. TRPV4 was initially identified as an osmolarity sensor, and is now known to be multi-modally activated by warm temperature, mechanical force (osmotic and shear stress), phorbol ester derivatives, UVB (type B ultraviolet rays), and a wide number of chemical agonists (Boudaka, Al-Yazeedi, & Al-Lawati, 2020; Liedtke et al., 2003; Moore et al., 2013). TRPV4 is abundant in the skin and mediates calcium influx into many resident skin cells including epidermal keratinocytes, melanocytes, immune cells such as mast cells and macrophages, endothelial cells of skin blood vessels and cutaneous neurons to affect wide range of processes such as hair growth, cell apoptosis, skin barrier integrity and differentiation, the release of paracrine and autocrine factors, nociception and itch as illustrated in Fig. 1 (Caterina & Pang, 2016; Chen et al., 2016; Liedtke et al., 2000; Liedtke & Friedman, 2003a; Moore & Liedtke, 2017; Olivan-Viguera et al., 2018; Sokabe et al., 2010; Szabó et al., 2019). TRPV4 might also be involved in skin aging and sexually dimorphic differences in skin. Skin inflammation is an evolutionarily-refined protective mechanism that clarifies noxious cues and irritants and initiates regeneration. However, the involvement of TRPV4 in dysregulation of these processes facilitates acute and chronic diseases involving pain, itch, fibrosis, and cancer (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The role of TRPV4 in skin homeostasis (black) and pathophysiological processes (red). TRPV4 is expressed in many cell types in the skin including keratinocytes, melanocytes, sensory nerve endings, immune cells such a macrophages and mast cells, hair follicles and fibroblasts. Created with BioRender.

2. TRPV4 in skin barrier function

TRPV4 has been implicated in the maintenance of skin barrier integrity. TRPV4 has been shown to contribute to inter-cellular junction formation in keratinocytes by interacting with β-catenin and enhancing cell-cell junction development and formation of tight barrier between keratinocytes (Sokabe et al., 2010). In human skin keratinocytes, activation of TRPV4 by warm temperature (33°C), or its chemical agonists lead to cell-cell junction development, augmentation of barrier integrity and acceleration of barrier recovery after disruption of the stratum corneum (Kida et al., 2012). Activation of TRPV4 was demonstrated to strengthen the tight junction associated barrier of epidermal cells, which resulted in the upregulation of occludin and claudin-4 tight junction structural proteins and tight junction regulatory factor, protein kinase C (PKC) (Akazawa et al., 2013). Additionally, knock down of TRPV4 resulted in increased inter-cellular permeation and reduced trans-epidermal resistance (Kida et al., 2012).

Mutations in the TRPV4 gene are known to cause autosomal dominant disorders: Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2C (CMT2C), scapuloperoneal spinal muscular atrophy, and congenital distal spinal muscular atrophy, which are neuropathies characterized by limb, diaphragm, and laryngeal muscle weakness (Landouré et al., 2010; McCray et al., 1993). Skin biopsies from patients with CMT2C revealed reduced density of Meissner corpuscles and intra-papillary myelinated endings as well as shortened intermodal lengths (Manganelli et al., 2015). A novel heterozygous mutation identified in the TRPV4 gene at position c.2355G > T, resulting in a tryptophan to cysteine substitution at amino acid 785 (p.Trp785Cys), was identified in family members who showed signs of congenital distal spinal muscular atrophy, skeletal abnormalities including osteonecrosis of the femoral head, and scaly skin (Liu et al., 2020a). Investigations into hereditary TRPV4 channelopathy disorders continue, and it can be considered likely that more links to epidermal signaling and function will be discovered.

3. TRPV4 in hair growth

Two recent studies revealed a contradictory role of TRPV4 in hair growth. TRPV4 was shown to be expressed on intact human hair follicles and was detected on the outer root sheath layer of the hair follicle epithelium (Szabó et al., 2019). In these human hair follicles, activation of TRPV4 via agonists disrupted hair shaft elongation, decreased intra-follicular proliferation, and induced premature catagen regression and apoptosis in culture (Szabó et al., 2019). On the other hand, a similar study in mice demonstrated that activation of TRPV4 using a small molecule agonist induced telogen to anagen transition and hair follicle regeneration by increasing the promotion of anagen promoting growth factors and downregulating the expression of anagen inhibiting factors (Yang et al., 2020). These two studies appear to reveal a contradictory role of TRPV4 in hair growth, which might be explained by the differences in the experimental set-up and species differences as Szabó et al. evaluated anagen maintenance ex vivo using cultured human hair follicles, while Yang et al examined follicle regeneration used in vivo mice studies. Further work is necessary to evaluate the role of TPRV4 in hair growth in vivo in humans.

4. TRPV4 in sensory perception

4.1. Osmo- and mechanosensation

TPRV4 was first identified as an osmosensitive ion channel and has been shown to function as an osmo-mechanosensor to maintain cellular osmotic homeostasis in many cellular systems (Liedtke et al., 2000; Liedtke & Friedman, 2003a; Moore & Liedtke, 2017). In fish, TRPV4 in skin keratinocytes senses the osmolarity of the aquatic environment and facilitates the immune effector mechanisms, as demonstrated in the fish model organism Danio rerio (zebrafish) (Galindo-Villegas et al., 2016). Pharmacological and genetic inhibition experiments demonstrated that skin keratinocytes through a TRPV4/Ca2+/transforming growth factor (TGF)-β–activated kinase 1 (TAK1)/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathways sensed osmotic stress to induce developmental immunity (Galindo-Villegas et al., 2016). TRPV4 was implicated also in the regulation of the mRNA and protein expressions of isotocin, a protein which controls ion regulation through modulating the functions of ionocytes in zebrafish (Liu et al., 2020b). TRPV4 gene knockdown decreased ionic contents (Na+, Cl−, and Ca2+) of whole larvae, the H+-secreting function of larval skin of zebrafish, and the numbers of ionocytes and epidermal stem cells in zebrafish larval skin. These results highlight the role of TRPV4 modulating ion balance through the isotocin pathway (Liu et al., 2020b).

In the chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), TRPV4 expression pattern in the skin and gills were regulated according to changes in salinity and temperature. In particular, TRPV4 x1 and TRPV4 x2 mRNAs, which are TRPV4 variants derived through alternate splicing, were predominant in the gill and skin including at the lateral line. TRPV4 x1 expression were significantly increased with increase in salinity and temperature, whereas TRPV4 x2 mainly responded to temperature decrease. Overall, TRPV4 contributes to the regulation of hydromineral balance in the chum salmon, by varying its transcription expression and alternate splicing (Lee, Lee, & Kim, 2021).

TRPV4 has been linked to dermato-fibrotic disorders such as scleroderma where both skin keratinocytes and fibroblasts have been implicated. In terms of relevant signaling mechanisms in the skin in dermato-fibrotic disorders, a pro-fibrotic role of fibroblast-expressing TRPV4, as well as a pro-inflammatory role of TRPV4, have emerged (Abdullah et al., 2014; Akiyama et al., 2016a; Aubdool & Brain, 2011; Chen et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2013; Mollanazar, Smith, & Yosipovitch, 2016; Moore et al., 2013; Rahaman et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2017). TRPV4 serves as a mechanosensitive Ca2+-permeable channel and regulates matrix stiffness and TGFβ1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMT) (Sharma et al., 2019). TRPV4 was identified as a candidate plasma membrane mechanosensor that transmits matrix-sensing signals by translocation of yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) in response to matrix stiffness and TGFβ1 in keratinocytes. TRPV4 deletion blocked both matrix stiffness-induced and TGFβ1-induced expression of YAP and TAZ proteins and was essential to long noncoding RNA expression (Sharma et al., 2019; Sharma, Ma, & Rahaman, 2020).

TRPV4 expression was found to be increased in burn scars with post-burn pruritus and the severity of the itch was correlated to the expression of TRPV4 (Yang et al., 2015). In another study, fibroblasts showed increased TRPV4 expression when stressed; their collagen synthesis was greatly attenuated after treatment with the selective TRPV4 inhibitor HC-067047 or when derived from Trpv4 null mice (Rahman et al., 2016), The experiments suggest that this phenomenon is a more general mechanism and that TRPV4 might be critically involved in the pathogenesis of scleroderma and other fibrosing disorders (Goswami et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2017).

4.2. Thermo-sensation

The epidermis senses a wide range of temperatures. Here, cells in the skin such as cutaneous nerve endings and keratinocytes contain temperature gated ion channels. TRPV4 was shown to be activated by warm temperatures (27–35 °C) in heterologous expression systems and in primary keratinocytes cultures (Chung, Lee, & Caterina, 2003; Guler et al., 2002; Tominaga, Liedtke, & Heller, 2007). TRPV4 is highly expressed in peripheral sensory free nerve endings and is located at cutaneous mechanosensory terminals, including Merkel cells, Meissner corpuscles, penicillate and intra-epidermal terminals, and in keratinocytes (Suzuki et al., 2003a). The role of TRPV4 in normal thermosensation in mammals is unclear as there has been contrasting results in the in vivo animal studies. Using TRPV4-deficient mice, no differences in escape latency from heat stimuli were observed in either radiant paw heating or the hot plate assays when compared to wild-type (WT) animals (Liedtke & Friedman, 2003b; Suzuki et al., 2003a). In contrast, in another study, TRPV4-deficient mice selected warmer floor temperatures in a selective gradient test, exhibited a strong preference for 34 °C, and had prolonged withdrawal latencies during acute tail heating than WT animals (Lee et al., 2005). Under hyperalgesic conditions, induced by subcutaneous injection of capsaicin or carrageenan, TRPV4-deficient mice showed longer escape latencies from a hot surface, relative to WT controls (Todaka et al., 2004). Further evidence that TRPV4 contributes to noxious heat sensation, mice with full TrpV4 deletions or keratinocytes specific TrpV4 deletions, were less sensitive to thermal stimuli after UVB induced hyperalgesia than control animals (Moore et al., 2013). These data suggest that TRPV4 plays a role in epidermal noxious thermosensation, a component of "forefront" signaling in the skin.

In the Japanese grass lizard, expression analysis of Trpv4 mRNA revealed that its expression in tissues and organs is specifically controlled in cold environments and hibernation (Nagai et al., 2012). Although cold treatment and hibernation reduced TRPV4 expression in tissues, such as the brain, tongue, heart, lung, and muscle, levels of Trpv4 mRNA in the skin remained unaffected after entering hibernation and cold treatment, suggesting that TRPV4 in the skin may act as an environmental temperature sensor throughout the reptilian life cycle, including hibernation, perhaps maintaining critical epidermal integrity during hibernation (Nagai et al., 2012).

5. TRPV4 in cutaneous immune regulation

In addition to its role as a protective barrier, the skin is home to many immune cell types that protect against invading pathogens and tissue damage. One such cell type that expresses TRPV4 is the mast cell (Kim et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2007). Stimulation of mast cells (RBL-283 cells) either by irradiation using a low-power laser, or sheer-stress, resulted in histamine release, which was blocked by Ruthenium Red, which can also block TRPV4 (Yang et al., 2007; Yang, Chen, & Zhou, 2009). In a human mast cell (MC)-related cell line, HMC-1, the authors documented TRPV4 mRNA expression and the response of HMC-1 cells to stimulation with the TRPV4- activator 4αPDD, which elicited a current and a Ca2+ signal. The role of TRPV4 in human MC was elucidated in more detail (Chen et al., 2017; Mascarenhas et al., 2017).

In rosacea, a facial skin inflammatory disorder, mast cells are exposed to high levels of the antibacterial peptide LL37, a proteolytic cleavage fragment of the innate immune precursor protein cathelicidin, which originates from neutrophils and macrophages. LL37 activates Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor member X2 (MRGPRX2) (Takahashi et al., 2018), a promiscuous G-protein-coupled receptor that can be activated by multiple pro-inflammatory mediators (Liu & Dong, 2015; McNeil et al., 2015; Meixiong et al., 2019; Navines-Ferrer et al., 2018; Tiwari et al., 2016). In a study using TRPV4-Crispr huMC and the TRPV4-selective inhibitor HC-067047, it was demonstrated that mast cell degranulation by either MRGPRX2-activating compound 48/80 or LL37 was TRPV4-dependent (Mascarenhas et al., 2017). Moreover, LL37 up-regulated Trpv4 mRNA, which was eliminated in MRGPRX2-Crispr huMC. These findings strongly suggest that MRGPRX2 signals upstream of TRPV4.

In addition to mast cells, TRPV4 is expressed in macrophages, also in the skin, and is suggested to be the link between mechanical forces and immune responses (Michalick & Kuebler, 2020). TRPV4 was found to be expressed in macrophages in various tissues such as lungs, joints, blood vessels, and skin (Hamanaka et al., 2010). In the skin, TRPV4 mediates substrate stiffness-induced macrophage polarization (Dutta, Goswami, & Rahaman, 2020). It was determined that fibrosis induced stiffer skin tissue and promoted M1 macrophage subtype in a TRPV4-dependent manner. In vitro, stiff matrix (50kPa) alone increased the expression of macrophage M1 markers in a TRPV4-dependent manner, and this response was further augmented by the addition of soluble factors; which did not occur with soft matrix (1 kPa). To test the requirement for TRPV4 in M1 macrophage polarization spectrum in response to increased stiffness, gain-of-function assays were performed, where TRPV4 was reintroduced into TRPV4 knockout macrophages and this significantly upregulated the expression of M1 markers (Dutta et al., 2020).

6. TRPV4 in nociception

There are multiple lines of evidence that support a role of TRPV4 in nociception in the skin, either depending on TRPV4 in the keratinocytes, in sensory neurons and perhaps in other cell lineages. Pain behaviors linked to epidermal TRPV4 include: osmotically-evoked pain (Alessandri-Haber et al., 2003, 2005; Liedtke & Friedman, 2003a), pressure and acidic nociception (Suzuki et al., 2003b), and mechanical hyperalgesia in neuropathic (Alessandri-Haber et al., 2004; Chen, Yang, & Wang, 2011; Ding et al., 2010; Fan et al., 2021; García-Mesa et al., 2021) and inflammatory pain (Chen et al., 2013, 2014; Segond von Banchet et al., 2013). TRPV4 in sensory neurons in DRGs and TGs that innervate the skin can be sensitized by pro-inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandin E2, activator of proteinase-receptor 2 (PAR-2), an integrator of proteolytic signaling in inflammation, leading to increased nociception to hypotonic, mild hypertonic stimuli or mechanical stimuli (Alessandri-Haber et al., 2006). It was found that TRPV4 is co-expressed with PAR2 by rat DRG neurons. Intra-plantar injection of PAR2 agonist caused mechanical hyperalgesia in mice and sensitized pain responses in a TRPV4-dependent manner (Grant et al., 2007).

TRPV4’s role in facilitating and promoting inflammation and pain was also supported by observations in a mouse model of skin inflammation in which UVB radiation generated sunburn tissue damage (UV-burn) and associated pathological pain (Moore et al., 2013). Following UVB over-exposure to their hindpaws, mice with induced Trpv4 deletions in keratinocytes and mice treated with topical TRPV4-inhibitors to their hindpaws were less sensitive to noxious thermal and mechanical stimuli versus control animals. These animals also showed dramatically reduced skin inflammation, evidenced by reduced macrophage recruitment and neutrophil infiltration and reduced secretion of inflammatory mediators such as IL6. These findings indicate that TRPV4-expressing keratinocytes of the hindpaw act as non-neural sensing and pain-generating cells, suggesting that activation of TRPV4 channels in skin keratinocytes, not in innervating sensory neurons, are sufficient to switch on neural pain networks and response-mechanisms. Exploring a possible underlying mechanism, it was determined that epidermal keratinocyte TRPV4 is essential for UVB-evoked skin tissue damage and increased expression of the pro-pain and pro-itch mediator endothelin-1 (ET-1) (Moore et al., 2013).

In regard to breast pain, TRPV4 was found be upregulated in the keratinocytes of painful breast tissue (Gopinath et al., 2005).

7. TRPV4 in itch

Itch is an irritating sensation of the skin that leads to a scratch reflex (Dhand & Aminoff, 2014). In humans, TRPV4 expression was found to be elevated in: burn scars of patients with pruritus (Yang et al., 2015); the skin biopsies of patients with chronic idiopathic pruritus(CIP) (Luo et al., 2018); and pruritic lesional skin of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis patients (Nattkemper et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2021).

The role of TRPV4 in itch has been demonstrated by a number of labs, some with conflicting results (Moore et al., 2018). Using TRPV4 knockout mice, Akiyama et al. demonstrated the intradermal injection of serotonin, histamine, the PAR2 agonist SLIGRL, and the non-histaminergic chloroquine to assess for scratching behavior (Akiyama et al., 2016b). Serotonin induced less itching compared to the wild type mice, chloroquine enhanced scratching in the TRPV4 knockout mice, whereas no difference was observed between wild-type and TRPV4 knockout mice for the histamine and SLIGRL injected animals. On the other hand, other studies found that mice lacking TRPV4 had reduced histamine induced itch compared to wild type animals, whereas no difference was observed for chloroquine-induced itch (Chen et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2016).

Chen et al. took these studies further with the use of the keratinocyte specific TRPV4 conditional knockout (cKO) mice to assess the roles of TRPV4 in the action of the histaminergic pruritogens including histamine, compound 48/40, endothelin-1, and chloroquine. Endothelin, a known pruritogen, was previously shown to be secreted in a TRPV4-dependent manner from epidermal keratinocytes (Moore et al., 2013). In the skin-specific TRPV4 cKO animals, scratching behaviors were significantly attenuated in all histaminergic pruritogens tested but not chloroquine, suggesting a role for keratinocytic TRPV4 in histaminergic itch (Chen et al., 2016). Direct activation of TRPV4 with its agonist GSK1016790A (GSK101) induced scratching bouts and topical treatment with a TRPV4 antagonist, GSK205 was effective in attenuating histaminergic pruritogen induced scratching (Chen et al., 2016). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that histaminergic pruritus involving TRPV4 channels is signaled via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway as inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK), upstream of ERK, using the selective inhibitor U0126, as topical treatment reduced scratching behavior (Chen et al., 2016). In vitro, histamine, 48/80, and ET-1 produced Ca2+-transients in cultured primary keratinocytes that were TRPV4-dependent, and Ca2+ influx via TRPV4 increased phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (p-ERK) in keratinocytes (Chen et al., 2016). More recently the specific contribution of TRPV4 in sensory neurons to itch was investigated by employing a sensory neuron TRPV4 conditional knockout mouse model. It was determined that for acute itch, cKO of TRPV4 in sensory neurons significantly attenuated scratching behaviors evoked by histamine, 48/40 and 5-HT, but not SLIGRL and chloroquine, in mice (Zhang et al., 2022). Together, these studies suggest that TRPV4 in the skin, in both keratinocytes and sensory neurons, regulates histaminergic itch.

TRPV4 has been implicated in itch caused by cholestatic liver disease. It was demonstrated that lysophosphatyl choline (LPC) is elevated in the sera of patients with cholestatic itch and in the mouse model of cholestatic itch. LPC acts as a strong pruritogen in mice and non-human primates (Chen et al., 2021). Chen et al. demonstrated that LPC caused itch by binding directly to TPRV4 channels on keratinocytes, resulting in ERK activation and the keratinocytes’ vesicular extrusion of miRNA-146, which, in turn, activates TRPV1-positive proprioceptor sensory neurons (Chen et al., 2021).

Crotamiton (N-ethyl-o-crotonotoluidide) has been used as an anti-itch agent in humans over many decades (Kittaka, Yamanoi, & Tominaga, 2017). Using electrophysiological recordings, it was demonstrated that crotamiton inhibited TRPV4 channels, followed by large currents after crotamiton washouts. In mice, crotamiton significantly reduced the TRPV4 agonist GSK1016790A-induced scratching behaviors (Kittaka et al., 2017). The wealth of experimental evidence above highlights TRPV4 channel as an important regulator in itch and therefore should be considered as a new target for itch relief.

8. TRPV4 in skin cancer

TRPV4 channels are functionally expressed in human melanoma cell lines and pharmacological activation of TRPV4 in human melanoma cells was shown to cause severe cellular disarrangement, necrosis, and apoptosis (Olivan-Viguera et al., 2018). Another report also demonstrated that both melanocytes and melanoma cells ectopically express TRPV4. Similarly, activation of TRPV4 resulted in the decline of cell viability for melanoma A2058 and A375 cells and enhanced apoptosis of A375 cells. These studies revealed that TRPV4 mediates melanoma cell death via channel activation and calcium influx. They also characterized a new mechanism, whereby TRPV4 ion channel regulated the AKT pathway to drive the antitumor process (Zheng et al., 2019).

Recently it was reported that activation of TRPV4-induced exocytosis occurred in both heterologous expression systems and melanoma A375 cells (Li et al., 2022). Application of TRPV4 via its specific agonists resulted in vesicle priming from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) followed by morphological changes of mitochondrial crista, which lead to cell ferroptosis. A signaling mechanism underlying stimulus-triggered exocytosis was revealed, whereby when TRPV4 was activated, the resulting calcium entry enhanced protein folding and vesicle trafficking to promote exocytosis in melanoma (Li et al., 2022).

In non-melanoma skin cancer, TRPV4 was reduced in premalignant lesions when compared to the level of TRPV4 found in healthy or inflamed skin keratinocytes (Fusi et al., 2014). It was shown that TRPV4 was markedly downregulated in both the premalignant lesions of NMSC such as solar keratosis (SK) and Bowen’s disease (BD), and in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma (BCC). In cultured keratinocytes, cell exposure to a variety of proinflammatory mediators, including IL-8, which is released from keratinocytes upon TRPV4 stimulation, led to a reduction of TRPV4 expression (Benemei et al., 2014; Liedtke et al., 2014). It could be possible that the expression of TRPV4 differs between patients, cancer types, and sub-types and micro- and macroenvironments, and therefore larger and more targeted studies are needed to determine the role of TRPV4 in skin cancers.

9. Conclusions

In summary, TRPV4 is expressed in many cell types in the skin and plays critical roles in skin homeostasis such as barrier maintenance, hair growth, immune regulation, nociception and itch. Since TRPV4 functions in pathological states such as chronic pain, itch and skin cancer, we should not lose sight of TRPV4 as a therapeutic target for such diseases.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 1KL2TR002554 and NINDS award number K01-NS121195-01A1. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

I would like to thank Lily Orta for her work on Fig. 1.

References

- Abdullah H, et al. (2014). Rhinovirus upregulates transient receptor potential channels in a human neuronal cell line: Implications for respiratory virus-induced cough reflex sensitivity. Thorax, 69(1), 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akazawa Y, et al. (2013). Activation of TRPV4 strengthens the tight-junction barrier in human epidermal keratinocytes. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology, 26(1), 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, et al. (2016a). Involvement of TRPV4 in Serotonin-Evoked Scratching. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 136(1), 154–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, et al. (2016b). Involvement of TRPV4 in serotonin-evoked scratching. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 136(1), 154–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri-Haber N, et al. (2003). Hypotonicity induces TRPV4-mediated nociception in rat. Neuron, 39(3), 497–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri-Haber N, et al. (2004). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 is essential in chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain in the rat. The Journal of Neuroscience, 24(18), 4444–4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri-Haber N, et al. (2005). TRPV4 mediates pain-related behavior induced by mild hypertonic stimuli in the presence of inflammatory mediator. Pain, 118(1-2), 70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri-Haber N, et al. (2006). A transient receptor potential vanilloid 4-dependent mechanism of hyperalgesia is engaged by concerted action of inflammatory mediators. The Journal of Neuroscience, 26(14), 3864–3874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubdool AA, & Brain SD (2011). Neurovascular aspects of skin neurogenic inflammation. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. Symposium Proceedings, 15(1), 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benemei S, et al. (2014). The TRPA1 channel in migraine mechanism and treatment. British Journal of Pharmacology, 171(10), 2552–2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudaka A, Al-Yazeedi M, & Al-Lawati I (2020). Role of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channel in skin physiology and pathology. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 20(2), e138–e146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, & Pang Z (2016). TRP channels in skin biology and pathophysiology. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 9(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Yang C, & Wang ZJ (2011). Proteinase-activated receptor 2 sensitizes transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, transient receptor potential vanilloid 4, and transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 in paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain. Neuroscience, 193, 440–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, et al. (2013). Temporomandibular joint pain: A critical role for Trpv4 in the trigeminal ganglion. Pain, 154(8), 1295–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, et al. (2014). TRPV4 is necessary for trigeminal irritant pain and functions as a cellular formalin receptor. Pain, 155(12), 2662–2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, et al. (2016). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 ion channel functions as a pruriceptor in epidermal keratinocytes to evoke histaminergic itch. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 291(19), 10252–10262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, et al. (2017). TRPV4 moves toward center-fold in rosacea pathogenesis. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 137(4), 801–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, et al. (2021). Epithelia-sensory neuron cross talk underlies cholestatic itch induced by lysophosphatidylcholine. Gastroenterology, 161(1), 301–317.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MK, Lee H, & Caterina MJ (2003). Warm temperatures activate TRPV4 in mouse 308 keratinocytes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(34), 32037–32046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhand A, & Aminoff MJ (2014). The neurology of itch. Brain, 137(Pt 2), 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding XL,et al. (2010). Involvement of TRPV4-NO-cGMP-PKG pathways in the development of thermal hyperalgesia following chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion in rats. Behavioural Brain Research, 208(1), 194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta B, Goswami R, & Rahaman SO (2020). TRPV4 plays a role in matrix stiffness-induced macrophage polarization. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 570195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, et al. (2021). Role of TRPV4-P2X7 pathway in neuropathic pain in rats with chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion. Neurochemical Research, 46(8), 2143–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E (2009). Finding one’s niche in the skin. Cell Stem Cell, 4(6), 499–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusi C, et al. (2014). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) is downregulated in keratinocytes in human non-melanoma skin cancer. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 134(9), 2408–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Villegas J, et al. (2016). TRPV4-mediated detection of hyposmotic stress by skin keratinocytes activates developmental immunity.Journal of Immunology, 196(2), 738–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Mesa Y, et al. (2021). Involvement of cutaneous sensory corpuscles in non-painful and painful diabetic neuropathy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath P, et al. (2005). Increased capsaicin receptor TRPV1 in skin nerve fibres and related vanilloid receptors TRPV3 and TRPV4 in keratinocytes in human breast pain. BMC Womens Health, 5(1), 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami R, et al. (2016). TRPV4 ion channel is associated with scleroderma. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant AD, et al. (2007). Protease-activated receptor 2 sensitizes the transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 ion channel to cause mechanical hyperalgesia in mice. The Journal of Physiology, 578(Pt 3), 715–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guler AD, et al. (2002). Heat-evoked activation of the ion channel, TRPV4. The Journal of Neuroscience, 22(15), 6408–6414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamanaka K, et al. (2010). TRPV4 channels augment macrophage activation and ventilator-induced lung injury. American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, 299(3), L353–L362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida N, et al. (2012). Importance of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) in epidermal barrier function in human skin keratinocytes. Pflügers Archiv, 463(5), 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KS,et al. (2010). Functional expression of TRPV4 cation channels in human mast cell line (HMC-1). Korean Journal of Physiology & Pharmacology, 14(6), 419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, et al. (2016). Facilitation of TRPV4 by TRPV1 is required for itch transmission in some sensory neuron populations. Science Signaling, 9(437), ra71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittaka H, Yamanoi Y, & Tominaga M (2017). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) channel as a target of crotamiton and its bimodal effects. Pflügers Archiv, 469(10), 1313–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landouré G, et al. (2010).Mutations in TRPV4 cause charcot-marie-tooth disease type 2C. Nature Genetics, 42(2), 170–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Lee SY, & Kim YK (2021). Molecular characterization of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) gene transcript variant mRNA of chum salmon Oncorhynchus keta in response to salinity or temperature changes. Gene, 795, 145779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, et al. (2005). Altered thermal selection behavior in mice lacking transient receptor potential vanilloid 4. The Journal of Neuroscience, 25(5), 1304–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, et al. (2022). Activation of TRPV4 induces exocytosis and ferroptosis in human melanoma cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, & Friedman JM (2003a). Abnormal osmotic regulation in trpv4−/− mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100(23), 13698–13703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, & Friedman JM (2003b). Abnormal osmotic regulation in trpv4−/− mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100, 13698–13703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, et al. (2000). Vanilloid receptor-related osmotically activated channel (VR-OAC), a candidate vertebrate osmoreceptor. Cell, 103(3), 525–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, et al. (2003). Mammalian TRPV4 (VR-OAC) directs behavioral responses to osmotic and mechanical stimuli in C. elegans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100, 14531–14536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W, et al. (2014). Keratinocyte growth regulation TRP-ed up over downregulated TRPV4? The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 134(9), 2310–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, & Dong X (2015). The role of the Mrgpr receptor family in itch. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, 226, 71–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, et al. (2013). TRPA1 controls inflammation and pruritogen responses in allergic contact dermatitis. The FASEB Journal, 27(9), 3549–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, et al. (2020a). Novel TRPV4 mutation in a large Chinese family with congenital distal spinal muscular atrophy, skeletal dysplasia and scaly skin. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 419, 117153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ST, et al. (2020b). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 modulates ion balance through the isotocin pathway in zebrafish (Danio rerio). American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 318(4), R751–r759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, et al. (2018). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4-expressing macrophages and keratinocytes contribute differentially to allergic and nonallergic chronic itch. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 141(2), 608–619.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganelli F, et al. (2015). Charcot-marie-tooth disease: New insights from skin biopsy. Neurology, 85(14), 1202–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas NL, et al. (2017). TRPV4 mediates mast cell activation in cathelicidin-induced rosacea inflammation. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 137(4), 972–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCray BA, et al. (1993). Autosomal dominant TRPV4 disorders. In Adam MP, et al. (Eds.), GeneReviews(®). Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle Copyright © 1993-2022, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil BD, et al. (2015). Identification of a mast-cell-specific receptor crucial for pseudo-allergic drug reactions. Nature, 519(7542), 237–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meixiong J, et al. (2019). Activation of mast-cell-expressed mas-related G-protein-coupled receptors drives non-histaminergic itch. Immunity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalick L, & Kuebler WM (2020). TRPV4-A missing link between mechanosensation and immunity. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollanazar NK, Smith PK, & Yosipovitch G (2016). Mediators of chronic pruritus in atopic dermatitis: Getting the itch out? Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology, 51(3), 263–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, & Liedtke WB (2017). Frontiers in neuroscience osmomechanical-sensitive TRPV channels in mammals. In Emir TLR (Ed.), Neurobiology of TRP channels (pp. 85–94). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis (c) 2018 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, et al. (2013). UVB radiation generates sunburn pain and affects skin by activating epidermal TRPV4 ion channels and triggering endothelin-1 signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(34), E3225–E3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, et al. (2018). Regulation of pain and itch by TRP channels. Neuroscience Bulletin, 34(1), 120–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai K, et al. (2012). Structure and hibernation-associated expression of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channel (TRPV4) mRNA in the Japanese grass lizard (Takydromus tachydromoides). Zoological Science, 29(3), 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattkemper LA, et al. (2018). The genetics of chronic itch: Gene expression in the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with severe itch. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 138(6), 1311–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navines-Ferrer A, et al. (2018). MRGPRX2-mediated mast cell response to drugs used in perioperative procedures and anaesthesia. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 11628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivan-Viguera A, et al. (2018). Pharmacological activation of TRPV4 produces immediate cell damage and induction of apoptosis in human melanoma cells and HaCaT keratinocytes. PLoS One, 13(1), e0190307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patapoutian A (2005). TRP channels and thermosensation. Chemical Senses, 30(Suppl. 1), i193–i194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman SO, et al. (2014). TRPV4 mediates myofibroblast differentiation and pulmonary fibrosis in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M, et al. (2016). Electrophysiological characterization of voltage-dependent calcium currents and TRPV4 currents in human pulmonary fibroblasts. American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, 310(7), L603–L614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosterman D, et al. (2006). Neuronal control of skin function: The skin as a neuro-immunoendocrine organ. Physiological Reviews, 86(4), 1309–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segond von Banchet G, et al. (2013). Neuronal IL-17 receptor upregulates TRPV4 but not TRPV1 receptors in DRG neurons and mediates mechanical but not thermal hyperalgesia. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences, 52, 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Ma L, & Rahaman SO (2020). Role of TRPV4 in matrix stiffness-induced expression of EMT-specific LncRNA. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 474(1-2), 189–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, et al. (2017). TRPV4 ion channel is a novel regulator of dermal myofibroblast differentiation. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. ajpcell 00187 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, et al. (2019). TRPV4 regulates matrix stiffness and TGFβ1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 23(2), 761–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokabe T, et al. (2010). The TRPV4 channel contributes to intercellular junction formation in keratinocytes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 285(24), 18749–18758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, et al. (2003a). Localization of mechanosensitive channel TRPV4 in mouse skin. Neuroscience Letters, 353(3), 189–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, et al. (2003b). Impaired pressure sensation in mice lacking TRPV4. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 278(25), 22664–22668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó IL, et al. (2019). TRPV4 is expressed in human hair follicles and inhibits hair growth in vitro. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 139(6), 1385–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, et al. (2018). Cathelicidin promotes inflammation by enabling binding of self-RNA to cell surface scavenger receptors. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari V, et al. (2016). Mas-related G protein-coupled receptors offer potential new targets for pain therapy. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 904, 87–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaka H, et al. (2004). Warm temperature-sensitive transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) plays an essential role in thermal hyperalgesia. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 279(34), 35133–35138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M (2007). Frontiers in neuroscience the role of TRP channels in thermosensation. In Liedtke WB, & Heller S (Eds.), TRP ion channel function in sensory transduction and cellular signaling cascades. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Copyright © 2007, Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, & Caterina MJ (2004). Thermosensation and pain. Journal of Neurobiology, 61(1), 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, et al. (2021). Cimifugin relieves pruritus in psoriasis by inhibiting TRPV4. Cell Calcium, 97, 102429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Chen J, & Zhou L (2009). Effects of shear stress on intracellular calcium change and histamine release in rat basophilic leukemia (RBL-2H3) cells. Journal of Environmental Pathology, Toxicology and Oncology, 28(3), 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WZ, et al. (2007). Effects of low power laser irradiation on intracellular calcium and histamine release in RBL-2H3 mast cells. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 83(4), 979–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YS, et al. (2015). Increased expression of three types of transient receptor potential channels (TRPA1, TRPV4 and TRPV3) in burn scars with post-burn pruritus. Acta Dermato-Venereologica, 95(1), 20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, et al. (2020). Transient stimulation of TRPV4-expressing keratinocytes promotes hair follicle regeneration in mice. British Journal of Pharmacology, 177(18), 4181–4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, et al. (2019). Mechanism for regulation of melanoma cell death via activation of thermo-TRPV4 and TRPV2. Journal of Oncology, 2019, 7362875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Dias F, Fang Q, Henry G, Wang Z, Suttle A, et al. (2022). Involvement of sensory neurone-TRPV4 in acute and chronic itch behaviours. Acta Dermato-Venereologica 102: adv00651. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v102.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]