Abstract

An emerging market for smart, connected products (SCPs) has enabled the manufacturing value proposition towards smart product-service systems (smart PSS). However, a new value proposition of smart PSS has still not been widely adopted by mainstream users because of a gap between expectation and actual delivery. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the smart PSS adoption in the context of smart kitchen appliances from a value-based view. The results show that key value dimensions affect the adoption intention of smart PSS, and adoption intention mediates the effects of key value dimensions on actual use. These findings provide insights into formulating a specific value proposition of a smart PSS business model.

Keywords: Smart PSS, Smart kitchen appliances, Perceived value, Adoption model

Introduction

According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU 2021), the use of the Internet has accelerated during the Covid-19 pandemic, with the number of users surging by 800 million to reach 4.9 billion people in 2021, or 63 per cent of the world’s population. Smart connected products (SCPs) embedded with information technology (IT) in the product itself realize a seamless interconnection between physical products and virtual services through their powerful data processing power and ubiquitous wireless connectivity. They have changed the way of value creation in economic activity, and have triggered an emerging IT-driven business paradigm—smart product-service systems (smart PSS) (Zheng et al. 2019). As an emerging form of PSS, Valencia et al. (2015) defined smart PSS as: “the integration of smart products and e-services into single solutions delivered to the market to satisfy the needs of individual consumers” (p. 16).

As smart kitchen appliances are the most important part of smart homes, they have won the favour and investment of international manufacturers (e.g. Bosch, GE, and Samsung) due to their huge market growth potential (Technavio 2021). For smart kitchen appliances with smart PSS, SCPs have altered the industry structure and the nature of competition in the smart kitchen appliance market, which extends the value proposition of smart PSS from the traditional product use lifecycle to the whole industrial ecosystem (Porter and Heppelmann 2015). Although the expanding potential value proposition of smart PSS provides more opportunities for value creation and value capture, the key to the success of new value proposition is achieving users’ acceptance and continuous use (Nemoto et al. 2021). In other words, the benefits of the value proposition can be realized only if users are willing to adopt smart PSS.

However, recent research (Coskun et al. 2018; Funk et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2017; Mishra et al. 2021; Shin et al. 2018) has shown that smart PSS have not been widely adopted by mainstream users in the smart home market, which makes it difficult to fully demonstrate the advantages of the value proposition of smart PSS in smart kitchen appliances. Smart PSS deliver key value through the e-services generated from information surrounding SCPs (Zheng et al. 2018), but it is challenging to provide a good out-of-the-box experience because services often fail during use, resulting in most e-service delivery falling below users’ expectations (Mustafa et al. 2020; Tan et al. 2016); This has been found to be the case for smart robot assistants (Forgas-Coll et al. 2022), smart voice assistants (Mishra et al. 2021), smart bike-sharing services (Lu et al. 2019), and smart banking services (Alalwan et al. 2018). This gap between actual value delivery and expectations forces users to give up using smart PSS, and they may refuse to use them again in the future as a consequence of earlier bad experiences.

Contemporary service research believes that users are eager to gain perceived value from smart products/services, and these values are the key to influencing users’ physical behaviour (Huang 2018; Polo et al. 2017). Zeithaml (1988, p. 14) defined perceived value as: “the consumer’s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on perceptions of what is received and what is given.” Wang and Ming (2018) pointed out that perceived value represents the product-service value delivered to users, and the evaluation of perceived value can help companies determine whether their product-service meets users’ expectations, so as to optimize the product-service during value creation processes according to evaluation results. In smart PSS, new capabilities of SCPs (e.g. monitoring, control, optimization, and autonomy) serve as the key for value creation, and require the company to have the ability to choose the set of capabilities that its product-service value can deliver (Porter and Heppelmann 2015). Thus, measuring and modeling perceived value is the main challenge for the smart PSS adoption, and central to formulate a competitive value proposition.

In summary, perceived value plays a crucial role in explaining the smart PSS adoption and formulating a competitive value proposition (Gonçalves et al. 2020; Valencia et al. 2015), but existing research has rarely systematically explored the value factors of smart PSS. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the users’ adoption of smart PSS in the context of smart kitchen appliances from a value-based view, with two specific objectives: (1) Verifying the relationships between perceived value, adoption intention, and actual use of smart PSS; (2) Constructing a smart PSS adoption model with perceived value to help organizations understand potential motivations and barriers to users’ adoption of smart PSS.

With a view to reach our objectives, the paper is structured as follows: First, we offer a literature review for smart PSS, perceived value, and adoption model, as well as state our research model and hypotheses; secondly, we describe the methodology and collect the data for testing; Thirdly, we present the results of the hypothesis testing, examined by Structural Equation Modelling (SEM); Fourthly, we discuss the results by examples; Finally, we drew conclusions, implications, and limitations and suggestions for future research.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Smart kitchen appliances with smart PSS

With the popularization of the home IoT technology, the application sector of smart PSS has gradually extended from the manufacturing sector to the smart appliance sector (Zheng et al. 2019). It is continually increasing the application of smart PSS in smart kitchen appliances, as well providing better solutions for personalization, energy efficiency, and predictive maintenance (Aheleroffa et al. 2020). Smart PSS is regarded as an IT-driven value co-creation business strategy, which promotes positive interactions between users and stakeholders through the SCP capabilities of collect, process, and produce information, and generates new e-services from information surrounding SCP as the key values delivered (Zheng et al. 2018). In value co-creation, SCP is regarded as the medium and tools to help companies quickly acquire change in demand or expectation, while e-services are a portal and means to facilitate communication and interaction between users and other stakeholders, which ultimately maximize value in the form of complementary real-goods and virtual-goods (Liu et al. 2019). It follows that the users and multiple stakeholders co-create the value of smart PSS, where the transformation of the value creation mechanism marks traditional kitchen appliances as smart kitchen appliances with smart PSS.

IT can facilitate the interconnectivity between product-service components, enabling better interaction and development of smart kitchen appliances, and brings PSS solutions to a more intelligent level (Gaiardelli et al. 2021). Zheng et al. (2018) pointed out that the IT-driven PSS evolution can be divided into Conventional PSS, IoT-enabled PSS, and Smart PSS, and that the scope of smart PSS covers the two phases of IoT PSS and smart PSS. Further descriptions are provided as follows: (1) Conventional PSS: focuses on efficient delivery of information based on Internet-driven value creation. In this phase, smart kitchen appliances can only provide some basic product functions (e.g. remote control, information feedback), and e-recipes are provided as an additional service; (2) IoT-enabled PSS: based on conventional PSS with IoT. Information is collected and interchanged among the network devices, and different products are coordinated. In this phase, smart kitchen appliances take both online information processing capability and modular service composition, which can complete cooking activities through collecting and exchanging data across devices; (3) Smart PSS: it is enabled by the SCPs, whereby IT is embedded in the product itself for value creation. It is focused on interactive relationships in different contexts between the user and the product by SCPs. Benefiting from embedded IT, smart kitchen appliances have the ability of self-adaptation and response to context from online to offline, which allows them to perceive the cooking situation and provide relevant cooking services proactively.

Smart PSS and perceived value

Smart PSS represents an advanced digital business paradigm of digital servitization, which describes a logical shift from product-centric models to digital service-oriented offerings (Zheng et al. 2019). The logical shift improves the efficiency of service delivery and increases the product-service value by digital technology, which presents the importance of capturing competitive advantage from perceived value, and requires companies to understand users’ perceptions of its delivered products-services value (Zhao and Wang 2021). Perceived value reflects the criteria that are used in the decision-making process, and evaluating the key dimensions of perceived value enables users’ perceptions to compare them to the intended value creation of the companies, thereby providing guidance for formulating competitive value propositions (Rintamäki and Kirves 2017).

Despite the fact that perceived value has received widespread attention from the academy, the lack of agreement among scholars concerning the definition and the concept of perceived value results in inconsistent and incommensurable empirical measures (Boksberger and Melsen 2011). From a utilitarian perspective, some researchers believed that the ratio between quality and price will affect the user’s decision-making, but this cost-oriented view overlooks the complexity and multidimensionality of perceived value (Kim et al. 2007; Wang and Wang 2010). From a behavioural perspective, some researchers believed that the intangible costs (e.g. time, convenience, and security) in modern business society are the key factors that determine users’ decisions, but it ignores the importance of costs associated with consumption (Kim et al. 2007). Zeithaml’s (1988) definition of perceived value is the most widely accepted, according to users’ evaluation of the overall utility of products/services from benefit and sacrifice. Many scholars have developed measurements of perceived value with the benefit and sacrifice components to cover the interdependence and weight distribution of perceived value types (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prior research on the perceived value evaluation

| Author(s) | Perceived value | Research context | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benefit | Sacrifice | ||

| Lapierre (2000) | (1) Alternative Solutions; (2) Product Quality; (3) Product Customization; (4) Responsiveness; (5) Flexibility; (6) Reliability; (7) Supplier’s Image; (8) Trust; (9) Supplier Solidarity; (10) Technical Competence | (11) Price; (12) Time/Energy/Effort; (13) Conflict | IT-industry |

| Kim et al. (2007) | (1) Usefulness; (2) Enjoyment | (3) Technicality; (4) Perceived Fee | Mobile internet |

| Wang and Wang (2010) | (1) Information Quality; (2) System Quality; (3) Service Quality | (4) Technological Effort; (5) Perceived Fee; (6) Perceived Risk | Mobile hotel reservation |

| Chong et al. (2012) | (1) Usefulness; (2) Ease of Use (3) Entertainment; (4) Ubiquity; (5) Network Externality | (6) Perceived Risk; (7) Perceived Price Level | Mobile internet |

| Kim et al. (2017) | (1) Facilitating Conditions; (2) Usefulness; (3) Enjoyment | (4) Privacy Risk; (5) Innovation Resistance; (6) Technicality; (7) Perceived Fee | Smart home |

| Hsu and Lin (2018) | (1) Usefulness; (2) Enjoyment | (3) Privacy risk; (4) fee | IoT service |

| Yu et al. (2019) | (1) Enjoyment; (2) Usefulness | (3) Technicality; (4) Fee; (5) Innovation Resistance; (6) Anxiety | Self-service |

| Lee and Leonas (2020) | (1) Speed; (2) Ease-of-Use; (3) Control; (4) Enjoyment | (5) Technology failure | Self-checkout |

Using perceived value to explain adoption

The most prominent model for explaining technology adoption is the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which states that the influences of external variables on behaviour are mediated by usefulness and ease of use (Davis 1989). However, the model was originally developed to explain individuals’ adoption of traditional technology instead of service consumers. The adopters and users of new ICT are individuals who play the dual roles of technology user and service consumer, so Kim et al. (2007) proposed a model to explain end users’ adoption of ICT by perceived value—the Value-based Adoption Model (VAM), which states that perceived value is the principal determinant of adoption of new ICT. In contrast with TAM, VAM borrows the Cost–Benefit Paradigm that adoption decisions are based on comparisons of the uncertain benefits with the uncertain costs of adopting an alternative, which reflects the user’s individual decision-making process with monetary price, thereby representing the end users’ evaluation of the overall utility of products and services (Lin et al. 2012).

VAM further divides perceived benefits and sacrifices into external and cognitive benefits, internal and affective benefits, monetary sacrifice, and non-monetary sacrifice. The following further explains: (1) External and cognitive benefits: these are the benefits gained from the performance of an activity to achieve a specific goal. The external stimulus can lead to changes in internal motivation, which in turn affects the perceived value of products and services (Deci 1971; Kim et al. 2007); (2) Intrinsic and affective benefits: these are the benefits gained from engaging in activities without any enforced intervention. Deci (1971) pointed out that if a person engages in an activity without any physical rewards, that person is considered to be intrinsically motivated to do something. Intrinsic motivation has been found to affect perceived value and behavioural intentions associated with emotion (Babin et al. 1994; Dube-Rioux 1990); (3) Monetary sacrifice: this is the sacrifice of actual price paid for products and services. Users will generally measure utility based on perceptions of the actual price paid, and maximize the “value” from the products and services (Boksberger and Melsen 2011; Kim et al. 2007); (4) Non-monetary sacrifice: this is the sacrifice of intangible costs paid for products and services. Non-monetary costs include time, burden, and risk, and will indirectly affect the perceived value of products and services (Boksberger and Melsen 2011; Kim et al. 2007; Lapierre 2000; Zeithaml 1988).

Following our previous work (Yu and Sung, in press), we found five perceived value dimensions of smart PSS through Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (Table 2): usefulness, flexibility, reliability, fee, and technicality. Given the broad consensus that perceived value affects adoption intention (Chong et al. 2012; Kim et al. 2007, 2017; Lee and Leonas 2020; Wang and Wang 2010), these perceived value dimensions are crucial for explaining the smart PSS adoption.

Table 2.

The perceived value of smart PSS

| Scope | Aspects | Perceived value | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefit | Extrinsic and cognitive benefit | Usefulness | Usefulness is the degree of improvement in the use of product performance after using the smart PSS | Chong et al. (2012), Davis (1989), Kim et al. (2007), Kim et al. (2017), Yu et al. (2019) |

| Flexibility | Flexibility is the smart PSS which handles dynamic users’ needs by reconfiguration | de Moura Leite et al. (2020), Lapierre (2000) | ||

| Intrinsic and affective benefit | Reliability | Reliability is the accuracy, safety, and traceability of the smart PSS during usage | Lapierre (2000) | |

| Sacrifice | Monetary sacrifice | Fee | Fee is the reasonableness and fairness of the relevant price of the smart PSS | Chong et al. (2012), Kim et al. (2007), Kim et al. (2017), Lapierre (2000), Yu et al. (2019) |

| Non-monetary sacrifice | Technicality | Technicality is the difficulty of using smart PSS caused by technologies | Kim et al. (2007), Kim et al. (2017), Lee and Leonas (2020), Wang and Wang (2010), Yu et al. (2019) |

Research model and hypotheses development

VAM was developed for the M-Internet adoption in the era of 3G technology. However, 3G technology corresponds to conventional PSS which focuses on the efficient transmission of data to create value instead of smart PSS. Smart PSS are enabled by the SCPs, which represent digital servitization for value creation from cyberspace to physical space (Zheng et al. 2018). Due to the different value creation mechanisms in the IT-driven evolution of PSS, for this study we believe that it is necessary to customize a specific VAM for smart PSS, including two aspects: (1) value structure: smart PSS follows the service-dominant logic that value is co-created by multiple stakeholders (Zheng et al. 2019). Companies cannot create or deliver value unilaterally, but offer the specific value proposition that users perceive value in real contexts (Vargo and Lusch 2008), which makes it important to understand the key value dimensions that influence adoption. Past studies have mainly considered the effect of overall value on different outcomes, but conceptualizing perceived value as a unidimensional construct may be too simplistic, and may not capture the intricate relationships between different value dimensions and behaviour (Ashraf et al. 2021). Therefore, it is necessary to construct the multi-dimensional value for smart PSS; (2) value scope: SCPs offer exponentially expanding opportunities for new functionality, far greater reliability, much higher product utilization, and capabilities that cut across and transcend traditional product boundaries, which disrupts the individual activities in the smart PSS value chain and reshapes the value system of smart PSS (Chen et al. 2020; Porter and Heppelmann 2015). As the new value system goes beyond the scope of traditional value, it is necessary to re-establish the value scope for the smart PSS adoption.

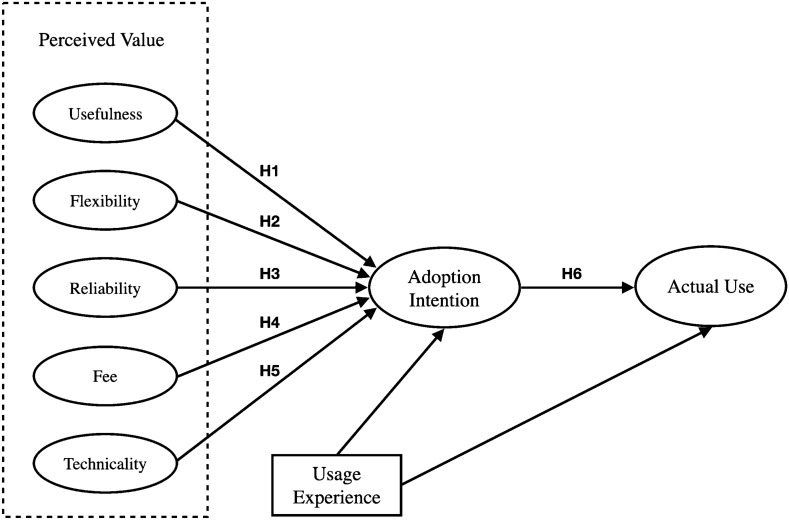

Although using perceived value to explain users’ adoption has been widely recognized (Chong et al. 2012; Kim et al. 2007, 2017; Lee and Leonas 2020; Wang and Wang 2010; Yu et al. 2019), existing studies on perceived value have rarely tested the structures of adoption intention on actual use. Ajzen and Madden (1986) pointed out that people’s behaviour is fundamentally motivational in nature, and the immediate antecedent of any behaviour is the intention to perform the behaviour in question. The viewpoint that using adoption intentions predict behaviour and mediate antecedents of intention and behaviours is widely used in testing and modelling for ICT system studies (e.g. Technology Acceptance Model, Theory of Planned Behaviour, and Theory of Reasoned Action). Therefore, we think that it is necessary to include a construct of actual use to extend VAM to investigate the smart PSS adoption, and whether the adoption intention mediates between the perceived value and actual use (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Research model and hypotheses

Perceived value and adoption intention

In social exchange theory, “value” is regarded as the determinants of any social behaviour, and is thus the essence of reciprocal exchange transactions or, more specifically, social interactions (Boksberger and Melsen 2011). Heinonen et al. (2019) believe that the process of social interaction reflects the formation of perceived value, which is always related to the function of trade-off offering generated (benefit) or decreased (sacrifice) value. This value function, defined in terms of perceived gain or loss relative to a reference point, is considered an effective way to predict behavioural intentions because users tend to choose the behaviour that leads to value maximization (Hsu and Lin 2018; Kim et al. 2007). Currently, the view of perceived value as a ratio of benefits to sacrifices is widely accepted in information system research and represents one of the dominant views in the literature (Chong et al. 2012; Hsu and Lin 2018; Kim et al. 2017; Lee and Leonas 2020; Wang and Wang 2010; Yu et al. 2019).

Usefulness is the degree of improvement in the use of product performance after using smart PSS. SCPs embedded with sensors, processors, software, and interconnected components into products, are driving the significant improvements in product performance (Porter and Heppelmann 2015). For example, smart kitchen appliances can realize remote control and monitor for heating precisely through mobile devices in an IoT environment. Improving performance has shown that the matching between the capabilities of the user and the functionalities offered by the technology increase the perceived value of smart PSS, thereby positively affecting adoption intentions (Chi 2018; Foroughi et al. 2019; Rafique et al. 2020; Tao et al. 2020). Thus, we hypothesize:

H1

Perceived usefulness is positively related to adoption intention.

Flexibility is the smart PSS which handles dynamic users’ needs by reconfiguration. Smart PSS enables the company to respond to the emerging and changing user demands in a flexible way by automatic decision supports based on user-generated content (de Moura Leite et al. 2020; Rapaccini and Adrodegari 2022). For example, smart kitchen appliances can flexibly recommend e-recipes to the user based on massive user/product-generated data, and provide new opportunities for food sales while meeting user demands. The value that the flexibility brings to users contributes to a better user experience, thereby improving the willingness to adopt smart PSS (Carrera-Rivera et al. 2022). Thus, we hypothesize:

H2

Perceived flexibility is positively related to adoption intention.

Reliability is the accuracy, safety, and traceability of smart PSS during usage. Recently, many paid e-services have been closely bundled with product use, benefiting from the high popularity of online payment, which makes the finance-related usage experience stands out as an issue of user trust in smart PSS. (Al-Saedi et al. 2020; Singh and Sinha 2020). Trust is regarded as the value of reliability that the user can perceive in smart PSS; it enables users to overcome their concerns about risks and reduces their uncertainties, thereby positively affecting their adoption intentions. Thus, we hypothesize:

H3

Perceived reliability is positively related to adoption intention.

Fee is the reasonableness and fairness of the relevant price of the smart PSS. In smart PSS, SCPs are regarded as the tools to guide generated e-services for value delivery (Zheng et al. 2019). This means that purchasing the product is only the beginning of the expense, and the key to profit is treating a product’s price and a service’s fee as a whole. However, a high price with excess fees deters most potential users (Li et al. 2021a, b; Marikyan et al. 2019; Wünderlich et al. 2015) because the worry and guilt caused by spending much money may reduce the value that users perceive, which then negatively affects their adoption intention (Hong et al. 2020; Li et al. 2021a, b; Park et al. 2018). Thus, we hypothesize:

H4

Perceived fee is negatively related to adoption intention.

Technicality is the difficulty of using smart PSS caused by technologies. ICT leads new types of interactions of smart PSS which enable the user to complete tasks independently (e.g. self-service, DIY, and remote control), but a new type of interaction still requires learning and adaptation on the part of users. In the process of learning, these technologies may have no obvious gains in usage, but cause users to exert some effort (Kim et al. 2007; Wang and Wang 2010). In other words, the more technological effort users put into the use, the less likely they are to get a high-value perception, thereby negatively affecting their adoption intentions (Lee and Leonas 2020; Rapaccini and Adrodegari 2022). Thus, we hypothesize:

H5

Perceived technicality is negatively related to adoption intention.

Adoption and actual use

Goals or resolutions stand a better chance of being realized when they are furnished with implementation intentions (Ajzen and Madden 1986). The motivation-based behaviour theory emphasizes the role of intention in shaping behaviour (e.g. Behavioural Reasoning Theory, Theory of Reasoned Action, and Theory of Planned Behaviour), which has been widely used to explain information systems adoption (e.g. Technology Acceptance Model, The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology). For consumer products/services, the behavioural intention stimulated by perceived value is regarded as a measurement of the intention of the specific behaviour (Hsiao and Chen 2018; Kim et al. 2007), and the intensity of the intention will determine the actual behaviour (Ajzen 2020). Although there are few VAM-related studies investigating the construct of actual use, there is abundant evidence that adoption intention can predict actual use (e.g. Davis et al. 1989; Mathieson et al. 2001; Venkatesh and Bala 2008; Venkatesh et al. 2012; Patil et al. 2020). Thus, we hypothesize:

H6

Adoption intention is positively related to actual use.

Control variables

Previous studies have reported that past usage experience may impact on smart PSS adoption (Baishya and Samalia 2020; Venkatesh et al. 2012) because consumers who use smart PSS for a longer time are more likely to adopt them than those who use them for a few weeks. Therefore, we included usage experience (UE) as a control variable in the model to more accurately explain the causal relationship among the latent variables.

Method

Measures

The instruments were adopted from prior studies to ensure the content validity of the scale. First, five perceived value dimensions of usefulness, flexibility, reliability, fee, and technicality were adopted from our previously published paper (as mentioned in Sect. 2.1). Secondly, since VAM explicitly states that perceived value affects adoption intention, we adopted the construct of adoption intention from Kim et al. (2007). Thirdly, actual use was adopted from Davis et al. (1989), Mathieson et al. (2001), and Venkatesh et al. (2012) to measure the events over a period of time, which could avoid the temporal mismatches between belief measurement and behaviour measurement.

To ensure that important aspects were not overlooked, and that the questions were accurate measures, the questionnaire was reviewed by three doctoral researchers in IoT-related majors and two professionals in the IoT field for appropriateness assessment. The assessment included scale wording, instrument length, questionnaire format, and the structure of the questionnaire. After careful examination and some slight revision, the wording was more precise to constitute a complete scale for this study (Table 3). Since the scale was initially developed in English, a double translation (English–Chinese–English) protocol was used (Hambleton 1993). This procedure was accomplished by two native English speakers who have a master’s degree in Chinese language. The questionnaire was pre-tested on 20 potential respondents to check for linguistic nuances for each item, which were then re-phrased accordingly.

Table 3.

The dimensions and items of value-based adoption

| Dimensions | Items | References |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived value | ||

| Usefulness | (USE1) Using smart kitchen appliances enhances my task effectiveness | Davis (1989), Kim et al. (2007) |

| (USE2) Using smart kitchen appliances gives me greater control over my work | ||

| (USE3) Using smart kitchen appliances makes it easier to do my task | ||

| (USE4) Using smart kitchen appliances improves my task performance | ||

| (USE5) Using smart kitchen appliances saves me time and effort in performing tasks | ||

| Flexibility | (FLE1) Smart kitchen appliances have flexibility in responding to your requests | Lapierre (2000) |

| (FLE2) Smart kitchen appliance companies have the ability to adjust their products and services to meet unforeseen needs | ||

| (FLE3) Smart kitchen appliances have a way of handling change | ||

| Reliability | (REL3) Smart kitchen appliances have accuracy and clarity of billing | Lapierre (2000) |

| (REL4) Smart kitchen appliances have the ability to keep promises of product quality | ||

| (REL5) Smart kitchen appliances have the ability to keep promises of service quality | ||

| Fee | (FEE1) I think the fee that I have to pay for the use of smart kitchen appliances is too high | Chong et al. (2012), Kim et al. (2007) |

| (FEE2) I think the price of using product is a burden to me | ||

| (FEE3) I think the price of using service is a burden to me | ||

| (FEE4) I think the fee of using product is unreasonable | ||

| (FEE5) I think the fee of using service is unreasonable | ||

| Technicality | (TECH1) I think smart kitchen appliances provide an easy navigation interface. (reversed) | Kim et al. (2007), Wang and Wang (2010) |

| (TECH2) I think smart kitchen appliances can be connected instantly. (reversed) | ||

| (TECH3) I think it is easy to get smart kitchen appliances to do what I want them to do. (reversed) | ||

| Adoption intention | ||

| Adoption intention | (AI1) I intend to use smart kitchen appliances in the future | Kim et al. (2007) |

| (AI2) I predict I would use smart kitchen appliances in the future | ||

| (AI3) I plan to use smart kitchen appliances in the future | ||

| Actual use | ||

| Actual use | (AU1) I often use smart kitchen appliances | Davis et al. (1989), Mathieson et al. (2001), Venkatesh and Bala (2008) |

| (AU2) I often connected to smart kitchen appliances the last month | ||

| (AU3) I often spend time using smart kitchen appliances each day | ||

For this research, we conducted a survey by online questionnaire, and the questionnaire was divided into two parts: (1) user information: including gender, age, education, usage experience, and occupation; (2) value-based adoption scale: the scale was measured on a 7-point Likert scale, with anchors ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. It is worth noting that since there was no computer recording the actual usage frequency in this study, we applied self-reported measures. Although self-reported frequency measures should not be regarded as precise measures of actual usage frequency, previous research suggests they are appropriate as relative measures (Blair and Burton 1987; Hartley et al. 1977).

Questionnaire and data collection

Since the Asia–Pacific region has become the main driving force for the growth of the smart kitchen appliance market in the future (Technavio 2021), China is a good environment for the study of smart kitchen appliances. In this investigation, the samples are based on the users who already use smart kitchen appliances, because we could not ask people who had no experience of using such smart kitchen appliances to answer what they perceive the value to be based on their (lack of) experience. This type of sample selection has been widely applied in information systems research and represents a mainstream voice as well (e.g. Davis et al. 1989; Kim et al. 2007; Venkatesh et al. 2012; Ashraf et al. 2021).

The data for this study were collected from June 14 to August 13, 2021, via a self-administered online survey. Questionnaire advertising was posted for 2 months at public forums in China. The participants could respond to the online questionnaire by clicking the URL provided in the message. In order to ensure that the questionnaire could be accurately delivered to the target users, before filling out the questionnaire, potential respondents were reminded not to participate in the survey if they did not have experience of using large smart cooking appliances (e.g. extractor hoods, stoves, and food waste disposers), small smart cooking appliances (e.g. rice cookers, induction cooktops, pressure cookers, ovens, and microwaves), smart refrigerators, or smart dishwashers. After completing the questionnaire, each of the respondents could enter a lottery, with a reward of up to US$30.

Sample characteristics

A total of 546 questionnaires were recovered. In order to effectively eliminate duplicate responses to the survey, we deleted 28 invalid responses with duplicate IP addresses from our data sample, leaving 518 valid questionnaires, with an effective recovery rate of 94.9% (see a description of the sample characteristics in Table 4). First, the distribution of males (42.1%) and females (57.9%) was relatively even, and most of them were between 18 and 39 years old (84.0%). A younger age means being more open to new technologies (Cruz-Cárdenas et al. 2019), so those participants are most likely to adopt smart kitchen appliances. Secondly, most of the respondents in this survey had a college education or above (90.3%). Education is seen as a very important demographic variable when explaining people’s willingness to adopt appliances with new technology, because using new technologies requires a certain level of knowledge, and education level has a positive impact on the risk-taking preference for novelty (Rojas-Méndez et al. 2017). In addition, the jobs of the respondents are mostly professional (58.5%), while students only constituted 12.9% of the sample, which avoids the excessive homogeneity of age and education level caused by the student sample in some previous studies (Cruz-Cárdenas et al. 2019). In summary, the respondents are consistent with existing knowledge that young and highly educated professional people are more open to new information technology, and have higher income and consumption potential (Wang and Wang 2010). Therefore, such sample attributes are objective and effective for this study.

Table 4.

Demographic attributes of the respondents (n = 518)

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 218 | 42.1 | 42.1 |

| Female | 300 | 57.9 | 100.0 |

| Age | |||

| 18–29 | 220 | 42.5 | 42.5 |

| 30–39 | 215 | 41.5 | 84.0 |

| 40–49 | 63 | 12.2 | 96.1 |

| ≥ 50 | 20 | 3.9 | 100.0 |

| Job | |||

| Student | 67 | 12.9 | 12.9 |

| Professional | 303 | 58.5 | 71.4 |

| Self-employed | 58 | 11.2 | 82.6 |

| Others | 90 | 17.4 | 100.0 |

| Education | |||

| Under senior high school | 4 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Senior high school | 46 | 8.9 | 9.7 |

| College | 416 | 80.3 | 90.0 |

| Graduate and above | 52 | 10 | 100.0 |

| Usage experience | |||

| 1–2 years | 243 | 46.9 | 46.9 |

| 3–4 years | 182 | 35.1 | 82.0 |

| 5 years and above | 93 | 18.0 | 100.0 |

| Monthly income | |||

| CNY 5,000 and below | 160 | 30.9 | 30.9 |

| CNY 5001–7000 | 93 | 18.0 | 48.9 |

| CNY 7001–9000 | 80 | 15.4 | 64.3 |

| CNY 9001–11000 | 51 | 9.8 | 74.1 |

| CNY 11001–13000 | 46 | 9.0 | 83.1 |

| CNY 13001 and above | 88 | 17.0 | 100 |

On the other hand, we report the distribution of respondents by smart PSS use in Table 5. Since most of the respondents may have experienced more than one type of smart kitchen appliance, we used a multiple-choice question based on the four categories of smart kitchen appliances (Technavio 2018) to investigate the respondents’ experience with different types of smart kitchen appliances. Most respondents have experienced small smart kitchen appliances (96%) that are more affordable for young people, followed by smart refrigerators (61%) and smart dishwashers (43%) that families mainly use, and lastly, the large smart kitchen appliances (30%) that are uncommon in the consumer market.

Table 5.

Distribution of respondents by smart PSS use

| Smart PSS | Number of respondents (n = 518) | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

| Large smart cooking appliances | 155 | 30 |

| (e.g. extractor hoods, stoves, and food waste disposers) | ||

| Small smart cooking appliances | 497 | 96 |

| (e.g. rice cookers, induction cooktops, pressure cookers, ovens, and microwaves) | ||

| Smart refrigerators | 316 | 61 |

| Smart dishwashers | 223 | 43 |

Results

Non‑response bias

Non-response bias refers to a situation in which people being unwilling to answer a questionnaire may lead to biased results. Although, we tried to increase the response rate as much as possible by way of lottery, non-response bias still is a significant concern for online surveys (Alvarez and Beselaere 2005). To assessing the non-response bias in the results of this study, we conducted a Chi-Square test on the characteristics of the early respondents (n = 390) and late respondents (n = 128) according to the procedure suggested by Armstrong and Overton (1977). The test result showed that the respondents did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) in terms of their gender, age, job, education, or monthly income, so we excluded the possibility of nonresponse bias.

Common method bias

Data may have common method bias when they are collected from the same source, which could threaten the validity of the study (Podsakoff and Organ 1986). In this survey, the data were collected via an online questionnaire which allowed us to quickly remove duplicate responses by IP address, but we still used Harman’s one-factor test to identify any potential common method bias. The results showed that the first (largest) factor explained 30.882% of the variance and no general factor accounted for more than 50% of the variance, which was in line with the Harman’s (1976) suggestions. It indicated that common method bias may not be a serious problem in the data set.

Measurement model

We conducted CFA using the Mplus 8.0 software. Hinkin (1998) stated that CFA could evaluate the goodness of fit of a model through chi-square, degrees of freedom, and fit indices. The analysis results of the model show that χ2 = 578.850, df = 254, CFI = 0.957, TLI = 0.949, RMSEA = 0.050, and SRMR = 0.039. Carmines and Mclver (1981) suggested that a chi-square two or three times as large as the degrees of freedom is acceptable, and our model shows the χ2/df = 2.279 < 3, which meets the criterion. On the other hand, Hinkin (1998) stated that because the chi-square test is too sensitive to the impact of sample size, it is recommended to use a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) greater than 0.90 when evaluating the fit of a single model. Our model shows the CFI = 0.957 > 0.90, which is higher than the criterion. Therefore, the measurement model showed an acceptable model fit (Table 6).

Table 6.

Overall model fit of the measurement model

| Index | Criteria | Research model |

|---|---|---|

| Chi-square | Small is better | 578.580 |

| df | Larger is better | 254.000 |

| Chi-square/df | < 3 | 2.279 |

| CFI | > 0.90 | 0.957 |

| TLI | > 0.90 | 0.949 |

| RMSEA | < 0.08 | 0.050 |

| SRMR | < 0.08 | 0.039 |

Reliability and validity

To demonstrate the construct validity of the measure, we followed Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) suggestion. The results of the model showed that the standardized factor loadings of the 25 observed variables ranged from 0.621 and 0.904, which were all above 0.50. The CR of the seven latent variables ranged from 0.788 to 0.907, and the AVE values ranged from 0.554 and 0.722, indicating that the latent variable measurements had good variation explanation and a high degree of internal consistency (Table 7). Furthermore, the analysis exhibited that the correlation coefficients between factors were all lower than the square root of the individual factor AVE (Table 8). Therefore, the measurement model proved to have sufficient combination reliability, convergence validity, and discriminative validity.

Table 7.

Confirmatory factor analysis

| Factor | Item | Std. loading | t value | R2 | p | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usefulness | USE1 | 0.833 | 50.581 | 0.694 | *** | 0.907 | 0.662 |

| USE2 | 0.837 | 52.075 | 0.701 | *** | |||

| USE3 | 0.807 | 44.522 | 0.651 | *** | |||

| USE4 | 0.784 | 39.976 | 0.615 | *** | |||

| USE5 | 0.805 | 44.180 | 0.648 | *** | |||

| Flexibility | FLE1 | 0.727 | 26.018 | 0.529 | *** | 0.788 | 0.554 |

| FLE2 | 0.752 | 28.365 | 0.566 | *** | |||

| FLE3 | 0.752 | 28.419 | 0.566 | *** | |||

| Reliability | REL1 | 0.809 | 42.822 | 0.654 | *** | 0.886 | 0.722 |

| REL2 | 0.904 | 65.023 | 0.817 | *** | |||

| REL3 | 0.833 | 48.706 | 0.694 | *** | |||

| Fee | FEE1 | 0.621 | 21.113 | 0.386 | *** | 0.896 | 0.636 |

| FEE2 | 0.831 | 46.710 | 0.691 | *** | |||

| FEE3 | 0.854 | 51.877 | 0.729 | *** | |||

| FEE4 | 0.845 | 48.488 | 0.714 | *** | |||

| FEE5 | 0.812 | 41.854 | 0.659 | *** | |||

| Technicality | TECH1 | 0.862 | 49.833 | 0.743 | *** | 0.871 | 0.693 |

| TECH2 | 0.823 | 43.388 | 0.677 | *** | |||

| TECH3 | 0.811 | 40.919 | 0.658 | *** | |||

| Adoption intention | AI1 | 0.841 | 45.850 | 0.707 | *** | 0.848 | 0.650 |

| AI2 | 0.799 | 39.063 | 0.638 | *** | |||

| AI3 | 0.778 | 35.512 | 0.605 | *** | |||

| Actual use | AU1 | 0.859 | 36.500 | 0.738 | *** | 0.820 | 0.605 |

| AU2 | 0.766 | 29.187 | 0.587 | *** | |||

| AU3 | 0.700 | 24.515 | 0.490 | *** |

Table 8.

Correlation analysis

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. UE | ||||||||

| 2. USE | − 0.015 | 0.814 | ||||||

| 3. FLE | 0.022 | 0.441 | 0.744 | |||||

| 4. REL | − 0.044 | 0.480 | 0.606 | 0.850 | ||||

| 5. FEE | 0.032 | − 0.115 | − 0.144 | − 0.141 | 0.797 | |||

| 6. TECH | − 0.036 | − 0.390 | − 0.440 | − 0.516 | 0.146 | 0.832 | ||

| 7. AI | − 0.006 | 0.532 | 0.635 | 0.547 | − 0.224 | − 0.531 | 0.806 | |

| 8. AU | 0.020 | 0.283 | 0.339 | 0.291 | − 0.119 | − 0.284 | 0.533 | 0.778 |

Results for the structural model and hypothesis testing

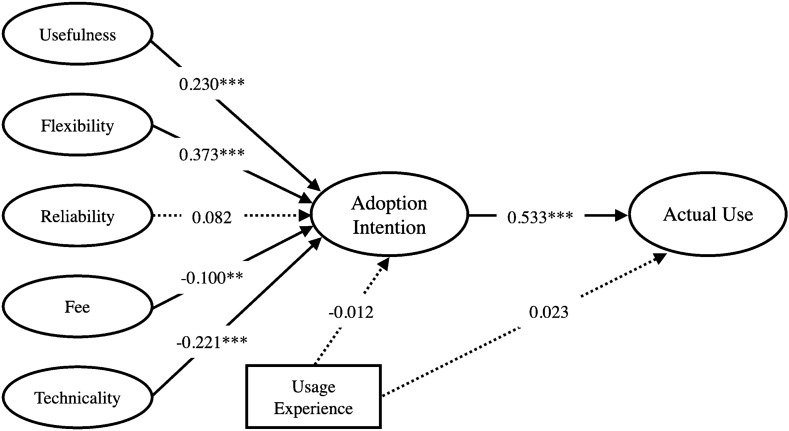

The structural model represented an acceptable fit to the data (χ2 = 606.544, df = 277, CFI = 0.956, TLI = 0.949, RMSEA = 0.048, and SRMR = 0.039), so we can further examine the relationship between latent variables (Table 9). First, the four antecedents of perceived value had significant effects on adoption intention: usefulness (β = 0.230, p < 0.001), flexibility (β = 0.373, p < 0.001), fee (β = − 0.100, p < 0.05), and technicality (β = − 0.221, p < 0.001), but reliability (β = 0.082, p > 0.05) was not statistically significant for the explanatory power of adoption intention. These results show that key value dimensions affect adoption intention, which supported hypotheses H1, H2, H4, and H5. Secondly, the path from adoption intention to actual use was significant (R2 = 0.533, p < 0.000), which is consistent with our expectation that a higher evaluation of adoption intention will lead to an increase in actual use. Thus, this result supported H6. Finally, usage experience has no significant impact on adoption intention (R2 = − 0.012, p > 0.05) and actual use (R2 = 0.023, p > 0.05) in this study, which indicates that the control variable does not affect the relationship among the latent variables.

Table 9.

Results of hypotheses tests (n = 518)

| Hypotheses | Paths | t-Values | Coefficients | p | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | Usefulness → Adoption intention | 5.007 | 0.230 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 2 | Flexibility → Adoption intention | 6.633 | 0.373 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 3 | Reliability → Adoption intention | 1.403 | 0.082 | 0.162 | Not supported |

| Hypothesis 4 | Fee → Adoption intention | − 2.603 | − 0.100 | ** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 5 | Technicality → Adoption intention | − 4.571 | − 0.221 | *** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 6 | Adoption intention → Actual use | 13.479 | 0.533 | *** | Supported |

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

On the other hand, our study hypothesized that adoption intention might be expected to moderate the relationship between perceived value and actual use, so we conducted an additional test to examine the direct effects of six antecedents including adoption intention on actual use. The results showed that adoption intention is significant for actual use (β = 0.583, p < 0.001), but five antecedents are not significant for actual use: usefulness (β = 0.001, p > 0.05), flexibility (β = − 0.025, p > 0.05), reliability (β = − 0.051, p > 0.05), fee (β = − 0.059, p > 0.05), and technicality (β = 0.027, p > 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the impact of perceived value on the adoption of smart PSS in the context of smart kitchen appliances. The results show that the smart kitchen appliances’ usage depends on the user’s intention, and the intention is determined by the perceived value of usefulness, flexibility, fee, and technicality of smart kitchen appliances (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Hypothesis testing results

Extrinsic and cognitive benefits

From the perspective of external cognitive benefits, usefulness and flexibility have a significant effect on adoption intention, and flexibility has the greatest effect on adoption intention among the five latent variables. First of all, the result of usefulness is in line with previous studies (Davis 1989; Vonk and Geertman 2008), and our study supports that the product performance affects intention again (R2 = 0.230, p < 0.001). In smart kitchen appliances, e-services have significantly increased the performance of products (e.g. e-recipes, electronic temperature control, and real-time monitoring), which not only provides users with higher cooking efficiency but also significantly reduces the possibility of errors caused by human operations. However, it is worth noting that some performance improvement of smart PSS often takes a long time to be realized (e.g. improving product efficiency, improving energy efficiency, and extending product life), so the potential benefits of usefulness for adoption intention deserves broader attention in smart PSS design, for example, providing a visible interface for the energy consumption of smart kitchen appliances.

Secondly, the flexibility of smart PSS to cope with dynamic users’ needs in complex situations has been widely discussed in recent years. Studies have discussed in detail the evaluation, development, and design methods of smart PSS adaptability from the technical perspective (de Moura Leite et al. 2020; Li et al. 2021a, b), while our study found the flexibility of smart PSS effect on adoption intention (R2 = 0.373, p < 0.001) from the user’s perspective. It means that the lag and mismatch between user needs and solutions will significantly reduce users’ intention to use the smart products and services. In smart kitchen appliances, the cooking demand often occurs intensively in a relatively short period. If the user’s needs are not solved in a timely manner, it may lead to a reduction in the user’s intention to use smart kitchen appliances, and may then weaken the attractiveness of novel smart technologies in the kitchen appliances market. Therefore, the reconfiguration is not only a current issue in the flexibility of smart PSS, but also a vital design concept throughout engineering, management, and marketing.

In addition, the design of performance-based services requires a high degree of flexibility to adapt to users’ needs (Holgado and Macchi 2021), which means that the smart PSS design must accommodate usefulness and flexibility. In smart kitchen appliances, a highly flexible system increases operating difficulty that may affect the cooking performance, while only increasing performance in a single cooking scenario may make it difficult to meet the dynamic users’ needs. To cope with this dilemma, a self-adaptable solution design with context-awareness was included in the discussion to match an appropriate function and a specific context (Zheng et al. 2019). For example, smart rice cookers can automatically match customized heating modes for users by the cloud platform and sensors, which can not only ease the user interface with a large number of parameters, but also improves the operating efficiency during cooking.

Intrinsic and affective benefits

Although the results show that reliability has no statistically significant effect on adoption intention (p > 0.05), reliability reached a moderate or higher correlation with usefulness and flexibility (r > 0.3), so we still believe that reliability of smart PSS deserves the attention of follow-up research. Compared with traditional kitchen appliances, since the electronic control and real-time monitoring of smart kitchen appliances improves the accuracy of temperature control and the potential safety hazards in the cooking process, users’ awareness of smart kitchen appliances is likely to be established on accuracy, safety, and traceability. Therefore, reliability may not be a major consideration in the consumption process, but it still plays a subtle role in the decision-making process.

Monetary sacrifice

As expected, perceived fee had a negative effect on adoption intention (R2 = − 0.100, p < 0.05). Although some research reports predict that the demand for high-end innovative kitchen appliances will increase continually (Technavio 2021), our findings suggest that users still need a long period of deliberation to decide to adopt a novel and expensive smart kitchen appliance. Nowadays, due to the global chip industry being struck by the Covid-19 pandemic, the insufficient capacity has led to a surge in chip prices which are finally passed on to users who adopt smart kitchen appliances; this may diminish the perceived value of smart kitchen appliances for users. Therefore, designers should be very cautious about the trade-off between R&D costs and retail prices in the development stage.

Besides, empirical evidence shows that smart homes usually take a family as a unit of consumption, which leads to actual users possibly not being purchasers or bill payers, and it also means that it is difficult for all users in a family to perceive the fee. Since users have a general preconceived impression that appliances with smart functions are more expensive (Coskun et al. 2018), this particular situation may mean that smart kitchen appliances with reasonable prices will not be adopted around users, and so the business performance will not meet market expectations. Therefore, the stakeholders must be clearly defined from the lifestyle of modern families in the beginning of smart PSS design, so as to provide users with accurate tangible value and relieve the loss of intangible value, for example including all family members in a management platform, and providing electronic bills and online payment through a user-friendly interface.

Non-monetary sacrifice

The technology affects adoption has been discussed for many years (e.g. Theory of Reasoned Action, Technology Acceptance Model, and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology), and our analysis shows that adoption intention was also negatively affected by technicality (R2 = − 0.221, p < 0.001) in smart PSS. Although digital technology enables smart PSS to support two-way communication (Valencia et al. 2015), mass information activities are also a double-edged sword. Information-induced complex operation (e.g. navigation, connection) may reduce the benefits of smart PSS and reduce users’ adoption intention over time, and this effect may be more pronounced for new users. In smart kitchen appliances, despite the visual interface being able to help improve the operating experience of cooking, the complicated connection and scattered switching logic among devices may cause an increase in the resistance to adoption. Therefore, how to tightly connect to different products/services and seamlessly access smart home networks is still a challenge for the adoption of smart kitchen appliances.

Indirect impact and control variables

In our model, the crux is to predict whether users will actually use the smart PSS, so we conducted an additional test for the six antecedents’ direct effect on actual use. The results showed that perceived usefulness, flexibility, reliability, fee, and technicality had no significant effect on actual use (p > 0.05), so adoption intention fully mediated the effects of usefulness, flexibility, fee and technicality on actual use. This finding means that users will not immediately use the smart PSS due to perceived value, but users’ impressions will gradually change in the process of value enhancement, and then they will adopt it. Therefore, taking perceived value into smart PSS development is a long-term strategy.

Usage experience as a control variable does not affect the results. A reasonable explanation is that users who have used them for a longer period of time do not necessarily want to continue using smart PSS, and they may have more complaints. On the other hand, users with less experience may not necessarily want to use smart PSS, but they may still have a sense of novelty.

Conclusions

This study verified the relationships between perceived value, adoption intention, and actual use of smart PSS in the context of smart kitchen appliances, and developed an adoption model of smart PSS that provides insights into formulating a competitive value proposition for its business model. The specific conclusions are as follows: (1) Product aspect: we found that users are more willing to adopt high-performance products (usefulness), but are equally sensitive to the cost (fee) required to improve product performance. This shows the role of an extreme cost-performance strategy in promoting the long-term profitability and popularization of smart PSS, and also implies that a shift toward new kinds of relationships with customers that provide sustainable value was recognized by users; (2) Service aspect: our finding that technicality affects adoption intention reflects the importance of building simple and fluent services for products. As the basis of competition gradually shifts from the functionality of a discrete product to the performance of the broader product system (Porter and Heppelmann 2015), we should think about how to enhance an across-device business for collaborative service capabilities of smart PSS, and close the gap between e-services and users through a seamless user experience; (3) System aspect: In recent years, the agility and the adaptability of reconfiguration (flexibility) has received widespread attention in smart PSS (de Moura Leite et al. 2020), while we found that flexibility has a significant effect on the adoption intention of smart PSS. It paves the way for a self-adaptable solution interweaving smart PSS and daily life, thereby narrowing the distance between smart PSS and real contexts.

Theoretical implications

Since the benefits of the new value proposition can be realized only if users are willing to adopt smart PSS, we developed an adoption model and scale for smart PSS to fill in the research gaps. First, the study empirically proves the importance of perceived value in explaining users’ behavioural intentions of smart PSS, which bridges a gap between the adoption of emerging information systems and service-based value creation, thus providing a theoretical basis for the popularization and success of a smart PSS business model. Secondly, the dimension of the scale reflects the value that smart PSS offers to users, and illustrates which perceived value affects the adoption. Although users are still quite concerned about what functions the products and services have and how much they need to pay, we also notice that a simpler, smoother, and more personalized experience is gradually affecting the smart PSS adoption, which provides a theoretical reference for formulating a competitive value proposition. Thirdly, our model can help to understand the interests pursued by multiple stakeholders in a value co-creation network of smart PSS, which contributes to users better participating in the process of value co-creation. It’s more realistic to understand the value co-creation of smart PSS from the viewpoint of adoption, as well providing a more pragmatic theory for building a better co-creation environment. Fourthly, this study not only identified that the value scope of smart PSS may cover the context of smart kitchen appliances, but also extends the model structure of VAM (Kim et al. 2007) by a construct of actual use, so as to more accurately explain the causality of smart PSS adoption from the users’ perceptions. Finally, our research responds to the call for information system research to move the “what” toward the “why” (Kar and Dwivedi 2020), thereby supporting theory building in information system management and deploying a comprehensive vision with user-centered strategic action.

Practical implications

This study provides practical management knowledge and experience for the popularization of smart PSS from a value-based view, which will benefit organizations which are on the verge of digital transformation. First, the scale provides specific guidelines for adopting smart PSS. Specific recommendations for building high-quality e-services can be extrapolated from our scale, which helps provide users with some unexpected experiences to support smart PSS innovation with user experience. Secondly, the scale was objectively quantified and validated as an analytical tool. The four dimensions of usefulness, flexibility, fee, and technicality can be used as effective evaluation measurement indicators for the smart PSS adoption, which can support the rational decision-making of designers and better determine the priorities for smart PSS development. Thirdly, our model could guide manufacturers to plan their value system that is disrupted by SCPs, and to maximize the value between multiple stakeholders and users to support the co-creative business strategy for smart PSS. Finally, although smart PSS tend to create value from long-term relationships, most providers and customers ultimately fail to secure a financial return on their investment (Kamalaldin et al. 2020). This study describes the shift of provider-customer relationships that affect adoption from a value-based view, which helps engineering managers and service designers to judge the potential revenue and growth of the smart PSS business model.

Limitations and future research needs

The current research has several limitations due to the human and material resources, which can be resolved in future research: (1) This study only considered smart kitchen appliances to discuss smart PSS in China, but the smart PSS adoption is a worldwide phenomenon. Future research can investigate the perceived value of smart PSS in different areas with a wider distribution of respondents, which would be helpful for strategic fine-tuning in response to different situations of adoption; (2) Although self-reported frequency is appropriate as a relative measure (Blair and Burton 1987; Hartley et al. 1977), this does not rule out the rare case of error; we therefore still encourage future research to objectively record the actual frequency of use by computer if the conditions permit; (3) Increasing value can be achieved with cost and time, but the truly challenging task is to reach the optimal perceived value level based on given boundaries regarding technologies, development time, and financial limitations. Therefore, future research can focus on the perceived quality attribute of smart PSS, to help us understand the engineering design decisions with user satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge everyone who has contributed in data collections.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aheleroffa S, Xu X, Lu YQ, et al. IoT-enabled smart appliances under industry 4.0: a case study. Adv Eng Inform. 2020;43:101043. doi: 10.1016/j.aei.2020.101043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior: frequently asked questions. Hum Behav Emerg Tech. 2020;2:314–324. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Madden TJ. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22:453–474. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(86)90045-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alalwan AA, Dwivedi YK, Rana NP, Algharabat R. Examining factors influencing Jordanian customers’ intentions and adoption of internet banking: extending UTAUT2 with risk. J Retail Consum Serv. 2018;40:125–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.08.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saedi K, Al-Emran M, Ramayah T, Abusham E. Developing a general extended UTAUT model for M-payment adoption. Technol Soc. 2020;62:101293. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez RM, Beselaere CV. Web-based survey. In: Kempf-Leonard K, editor. Encyclopedia of social measurement. London: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 955–962. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JS, Overton TS. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J Mark Res. 1977;14:396–402. doi: 10.1177/002224377701400320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf AR, Tek NT, Anwar A, Lapa L, Venkatesh V (2021) Perceived values and motivations influencing m-commerce use: a nine-country comparative study. Int J Inf Manage 59:102318. 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102318

- Babin BJ, Darden WR, Griffin M. Work and/or fun: measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J Consum Res. 1994;20:644–656. doi: 10.1086/209376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baishya K, Samalia HV. Extending unified theory of acceptance and use of technology with perceived monetary value for smartphone adoption at the bottom of the pyramid. Int J Inf Manage. 2020;51:102036. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair E, Burton S. Cognitive processes used by survey respondents to answer behavioral frequency questions. J Consum Res. 1987;14:280–288. doi: 10.1086/209112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boksberger PE, Melsen L. Perceived value: a critical examination of definitions, concepts and measures for the service industry. J Serv Mark. 2011;25:229–240. doi: 10.1108/08876041111129209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmines EG, Mclver JP. Social measurement models with unobserved variables: analysis of covariance structures. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications Inc; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera-Rivera A, Larrinaga F, Lasa G (2022) Context-awareness for the design of Smart-product service systems: literature review. Comput Ind 142:103730. 10.1016/j.compind.2022.103730

- Chen Z, Lu M, Ming X, Zhang X, Zhou T. Explore and evaluate innovative value propositions for smart product service system: a novel graphics-based rough-fuzzy DEMATEL method. J Clean Prod. 2020;243:118672. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chi T. Understanding Chinese consumer adoption of apparel mobile commerce: an extended TAM approach. J Retail Consum Serv. 2018;44:274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chong XL, Zhang JL, Lai KK, Nie L. An empirical analysis of mobile internet acceptance from a value-based view. Int J Mob Commun. 2012;10:536–557. doi: 10.1504/IJMC.2012.048886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun A, Kaner G, Bostan İ. Is smart home a necessity or a fantasy for the mainstream user? A study on users’ expectations of smart household appliances. Int J Des. 2018;12:7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Cárdenas J, Zabelina E, Deyneka O, Guadalupe-Lanas J, Velín-Fárez M. Role of demographic factors, attitudes toward technology, and cultural values in the prediction of technology-based consumer behaviors: a study in developing and emerging countries. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2019;149:119768. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis FD (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quart 13:319–340

- Davis FD, Bagozzi RP, Warshaw PR. User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Manage Sci. 1989;35:982–1003. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Moura Leite AFCS, Canciglieri MB, Goh YM, Monfared RP, Loures EFR, Junior C. Current issues in the flexibilization of smart product-service systems and their impacts in industry 4.0. Proc Manuf. 2020;51:1153–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.promfg.2020.10.162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL (1971) Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. J Pers Soc Psychol 18:105–115. 10.1037/h0030644

- Dube-Rioux L (1990) The power of affective reports in pre-dicting satisfaction judgments. Adv Consum Res 17:571–576

- Forgas-Coll S, Huertas-Garcia R, Andriella A, et al. The effects of gender and personality of robot assistants on customers’ acceptance of their service. Serv Bus. 2022;16:359–389. doi: 10.1007/s11628-022-00492-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18:39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foroughi B, Iranmanesh M, Hyun SS. Understanding the determinants of mobile banking continuance usage intention. J Enterp Inf Manag. 2019;32:1015–1033. doi: 10.1108/JEIM-10-2018-0237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Funk M, Eggen B, Hsu YJ. Designing for systems of smart things. Int J Des. 2018;12:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gaiardelli P, Pezzotta G, Rondini A, et al. Product-service systems evolution in the era of Industry 4.0. Serv Bus. 2021;15:177–207. doi: 10.1007/s11628-021-00438-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves L, Patrício L, Teixeira JG, Wünderlich N. Understanding the customer experience with smart services. J Serv Manage. 2020;31:723–744. doi: 10.1108/JOSM-11-2019-0349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton RK. Translating achievement tests for use in cross-national studies. Eur J Psychol Assess. 1993;9:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Harman HH. Modern factor analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley C, Brecht M, Pagerey P, Weeks G, Chapanis A, Hoecker D. Subjective time estimates of work tasks by office workers. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1977;50:23–36. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1977.tb00355.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen K, Campbell C, Ferguson SL. Strategies for creating value through individual and collective customer experiences. Bus Horiz. 2019;62:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2018.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin TR. A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organ Res Methods. 1998;1:104–121. doi: 10.1177/109442819800100106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong A, Nam C, Kim S. What will be the possible barriers to consumers’ adoption of smart home services? Telecommun Policy. 2020;44:101867. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2019.101867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao KL, Chen CC. What drives smartwatch purchase intention? Perspectives from hardware, software, design, and value. Telemat Inform. 2018;35:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2017.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CL, Lin JCC. Exploring factors affecting the adoption of internet of things services. J Comput Inf Syst. 2018;58:49–57. doi: 10.1080/08874417.2016.1186524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TL. Creating a commercially compelling smart service encounter. Serv Bus. 2018;12:357–377. doi: 10.1007/s11628-017-0351-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Telecommunication Union (2021) Measuring digital development: Facts and figures 2021. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. Retrieved from https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/FactsFigures2021.pdf

- Kamalaldin A, Linde L, Sjödin D, Parida V. Transforming provider-customer relationships in digital servitization: a relational view on digitalization. Ind Mark Manage. 2020;89:306–325. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kar AK, Dwivedi YK. Theory building with big data-driven research—moving away from the “What” towards the “Why”. Int J Inf Manage. 2020;54:102205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HW, Chan HC, Gupta S. Value-based adoption of mobile internet: an empirical investigation. Decis Support Syst. 2007;43:111–126. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2005.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Park Y, Choi J. A study on the adoption of IoT smart home service: using value-based adoption model. Total Qual Manag Bus Excell. 2017;28:1149–1165. doi: 10.1080/14783363.2017.1310708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre J. Customer-perceived value in industrial contexts. J Bus Ind Mark. 2000;15:122–145. doi: 10.1108/08858620010316831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Leonas KK. Millennials’ intention to use self-checkout technology in different fashion retail formats: perceived benefits and risks. Cloth Text Res J. 2020;39:1–17. doi: 10.1177/0887302X20926577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Yigitcanlar T, Erol I, Liu A. Motivations, barriers and risks of smart home adoption: from systematic literature review to conceptual framework. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2021;80:102211. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.102211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li XY, Chen CH, Zheng P, Jiang Z, Wang L. A context-aware diversity-oriented knowledge recommendation approach for smart engineering solution design. Knowl Based Syst. 2021;215:106739. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2021.106739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TC, Wu S, Hsu SC, Chou YC. The integration of value-based adoption and expectation–confirmation models: an example of IPTV continuance intention. Decis Support Syst. 2012;54:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.dss.2012.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Ming X, Song W (2019) A framework integrating interval-valued hesitant fuzzy DEMATEL method to capture and evaluate co-creative value propositions for smart PSS. J Clean Prod 215:611–625. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.089

- Lu D, Lai IKW, Liu Y. The consumer acceptance of smart product-service systems in sharing economy: the effects of perceived interactivity and particularity. Sustainability. 2019;11:928. doi: 10.3390/su11030928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marikyan D, Papagiannidis S, Alamanos E. A systematic review of the smart home literature: a user perspective. Technol Forecast and Soc Change. 2019;138:139–154. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2018.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson K, Peacock E, Chin WW. Extending the technology acceptance model. SIGMIS Database. 2001;32:86–112. doi: 10.1145/506724.506730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A, Shukla A, Sharma SK. Psychological determinants of users’ adoption and word-of-mouth recommendations of smart voice assistants. Int J Inf Manage. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa SZ, Kar AK, Janssen MFWHA. Understanding the impact of digital service failure on users: integrating Tan’s failure and DeLone and McLean’s success model. Int J Inf Manage. 2020;53:102119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto Y, Dhiman H, Röcker C. Design for continuous use of product-service systems: a conceptual framework. Proc Des Soc. 2021;1:983–992. doi: 10.1017/pds.2021.98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park K, Kwak C, Lee J, Ahn JH. The effect of platform characteristics on the adoption of smart speakers: empirical evidence in South Korea. Telemat and Inform. 2018;35:2118–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2018.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil P, Tamilmani K, Rana NP, Raghavan V. Understanding consumer adoption of mobile payment in India: extending meta-UTAUT model with personal innovativeness, anxiety, trust, and grievance redressal. Int J Inf Manage. 2020;54:102144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, Organ DW. Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J Manag. 1986;12:531–544. doi: 10.1177/014920638601200408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polo Peña AI, Frías Jamilena DM, Rodríguez Molina MÁ. The effects of perceived value on loyalty: the moderating effect of market orientation adoption. Serv Bus. 2017;11:93–116. doi: 10.1007/s11628-016-0303-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porter ME, Heppelmann JE. How smart, connected products are transforming competition. Harv Bus Rev. 2015;93:64–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rafique H, Almagrabi AO, Shamim A, Anwar F, Bashir AK. Investigating the acceptance of mobile library applications with an extended technology acceptance model (TAM) Comput Educ. 2020;145:103732. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaccini M, Adrodegari F. Conceptualizing customer value in data-driven services and smart PSS. Comput Ind. 2022;137:103607. doi: 10.1016/j.compind.2022.103607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rintamäki T, Kirves K (2017) From perceptions to propositions: profiling customer value across retail contexts. J Retail Consum Serv 37:159–167. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.07.016

- Rojas-Méndez JI, Parasuraman A, Papadopoulos N. Demographics, attitudes, and technology readiness: a cross-cultural analysis and model validation. Mark Intell Plan. 2017;35:18–39. doi: 10.1108/MIP-08-2015-0163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Park Y, Lee D. Who will be smart home users? An analysis of adoption and diffusion of smart homes. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2018;134:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2018.06.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Sinha N (2020) How perceived trust mediates merchant’s intention to use a mobile wallet technology. J Retail Consum Serv 52:101894. 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101894

- Tan CW, Benbasat I, Cenfetelli RT. An exploratory study of the formation and impact of electronic service failures. MIS Q. 2016;40:1–29. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2016/40.1.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao D, Wang T, Wang T, Zhang T, Zhang X, Qu X. A systematic review and meta-analysis of user acceptance of consumer-oriented health information technologies. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;104:106147. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Technavio (2018) Global smart kitchen appliance market 2019-2023 (Report No. IRTNTR30452). Technavio Research, London. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200124005172/ en/Global-Smart-Kitchen-Appliance-Market-2019-2023%C2%A0%C2%A0Growing-Demand

- Technavio (2021) Smart Kitchen Appliance Market by Product, Distribution Channel, and Geography—Forecast and Analysis 2021–2025 (Report No. IRTNTR43951). London: Technavio Research. Retrieved from https://www.technavio.com/report/smart-kitchen-appliance-market-industry-analysis

- Valencia A, Mugge R, Schoormans JPL, Schifferstein HNJ. The design of smart product-service systems (PSSs): an exploration of design characteristics. Int J Des. 2015;9:13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo SL, Lusch RF (2008) Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution. J Acad Mark Sci 36:1–10. 10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6

- Venkatesh V, Bala H. Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decis Sci. 2008;39:273–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5915.2008.00192.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh V, Thong JYL, Xu X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012;36:157–178. doi: 10.2307/41410412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vonk G, Geertman S. Improving the adoption and use of planning support systems in practice. Appl Spat Anal Policy. 2008;1:153–173. doi: 10.1007/s12061-008-9011-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PP, Ming XG (2018) Value evaluation method of industrial product-service based on customer perception. Int J Serv Oper and Inform 9:15–39. 10.1504/IJSOI.2018.088515

- Wang HY, Wang SH. Predicting mobile hotel reservation adoption: Insight from a perceived value standpoint. Int J Hosp Manag. 2010;29:598–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wünderlich NV, Heinonen K, Ostrom AL, Patricio L, Sousa R, Voss C, Lemmink JG. “Futurizing” smart service: implications for service researchers and managers. J Serv Mark. 2015;29:442–447. doi: 10.1108/JSM-01-2015-0040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Seo I, Choi J. A study of critical factors affecting adoption of self-customisation service: focused on value-based adoption model. Total Qual Manag Bus Excell. 2019;30:1–16. doi: 10.1080/14783363.2019.1665822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Sung TJ (in press) Perceived values to evaluate smart product-service systems of smart kitchen appliances. Eng Manag J. 10.1080/10429247.2022.2075210

- Zeithaml VA. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J Mark. 1988;52:2–22. doi: 10.2307/1251446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Wang X. Perception value of product-service systems: neural effects of service experience and customer knowledge. J Retail Consum Serv. 2021;62:102617. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P, Lin TJ, Chen CH, Xu X. A systematic design approach for service innovation of smart product-service systems. J Clean Prod. 2018;201:657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P, Wang ZX, Chen CH, Khoo LP. A survey of smart product-service systems: Key aspects, challenges and future perspectives. Adv Eng Inform. 2019;42:100973. doi: 10.1016/j.aei.2019.100973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data