Abstract

Recruiting and retaining sufficient participants is one of the biggest challenges researchers face while conducting clinical trials (CTs). This is due to the fact of misconceptions and insufficient knowledge concerning CTs among the public. The present cross-sectional study was conducted from April 2021 to May 2022. We evaluated knowledge and attitude among 480 participants using a pretested Arabic questionnaire. The correlation between knowledge and attitude score was tested through Spearman’s correlation test, and the logistic regression test evaluated the associated factors for knowledge and attitude. Of the studied participants, 63.5% were male and belonged to the age group less than 30 years (39.6%). Nearly two-thirds (64.6%) of them had never heard of CT. More than half of the participants had poor knowledge (57.1%) and attitude (73.5%) towards CTs. Participants’ knowledge scores were significantly associated with education level (p = 0.031) and previous participation in health-related research (p = 0.007). Attitude scores were significantly related to marital status (p = 0.035) and the presence of chronic diseases (p = 0.008). Furthermore, we found a significant positive correlation between knowledge and attitude scores (p < 0.001, Spearman’s rho = 0.329). The present study revealed that most of the study population had poor knowledge and moderate attitudes towards CT. Targeted health education programs at different public places are recommended to improve the public’s knowledge of the importance of CT participation. In addition, exploratory and mixed-methods surveys in other regions of KSA is required to recognize the region-specific health education needs.

Keywords: clinical trials, participation, knowledge, attitude, new drug, Saudi Arabia

1. Introduction

Clinical trials (CTs) are a type of research study design that allows participants in one or more health-related interventions to assess the effects on health-related outcomes [1]. CTs are considered the gold standard for identifying therapeutic strategies and diagnostic tests and contribute to one of the highest levels of evidence-based practice among healthcare practitioners [2,3]. Several studies worldwide reported that CTs are a powerful measure that improves healthcare services through evidence-based clinical practice for formulating public health decisions that lead to healthcare improvements [4,5]. Furthermore, the need for CTs during emergencies and pandemics such as COVID-19 was insisted on by numerous researchers [6,7].

Currently, 292,537 trials are registered with a clinical trial registry of the US National Library of Medicine from 209 countries, with a low contribution from the middle east and north Africa (MENA) countries, including the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) [8,9,10,11]. The number of clinical trials conducted in the KSA in the past 15 years is scarce, considering a population that exceeds 30 million and a huge annual healthcare budget [9]. To manage the necessary health needs of this region, there is an increase in the need for region-specific clinical trials. Despite the increasing prevalence of lifestyle-related and genetic diseases in these countries, the high growth of the population with an increased demand for medication, MENA countries sponsored less than 1% of global clinical trials. Several factors urge these countries to consider, implement, and conduct their own clinical trials [9,12]. The insufficient number of participants in a clinical trial may have several implications, such as nonsignificant results of important findings and loss of resources spent on planning and conducting the trials, as well as loss of reputation of the institution and investigators due to the fact of failed research [11,13].

An adequate number of participants is essential for conducting an effective CT [8]. Recruiting and the retention of sufficient participants is one of the biggest challenges researchers face while conducting CTs. This scenario also continued during the COVID-19 pandemic [8,13,14,15]. Several recommendations have been made to optimize subject participation in CTs. They are broadly divided into participants (i.e., public and patients) and investigator factors. Of these two categories, participants’ factors, such as their knowledge, attitude, and perceptions towards clinical research, including CTs, significantly impacted low recruitment and participation in CTs [8,13].

A study by Al Lawati et al. in 2018 in Oman found low-level participants’ knowledge of CTs; despite their good attitude, their participation in CTs was very low. The study also stated that less than one-third (31.3%) of participants were aware of CTs [16]. Another study conducted in the KSA by Nedal et al. in 2019 found low mean and attitude scores of the study participants towards CTs. They also reported that most of the participants agreed that CTs could be performed with patients, and only 30.5% of the participants agreed that new drugs and other interventions through CTs could be introduced among healthy people [17]. A recent survey assessing general population knowledge and attitude towards CTs stated that only 7.0% of the participants were aware of ClinicalTrails.gov, and 43.1% knew nothing about CTs [18]. The assessment of the general population’s knowledge and attitude towards CTs will help us to remove the misconceptions about CTs by increasing their knowledge according to the knowledge gap on CTs. Hence, the Saudi general population’s willingness to participate in CTs run by the concerned health authorities could significantly increase. Few studies in the KSA have attempted to assess healthcare workers’ and patients’ knowledge and attitude [19,20]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that have assessed the knowledge and attitudes towards CTs among the general public during the COVID-19 era, especially in the northern region of the KSA. Hence, the present study was conducted to assess the knowledge of and attitude towards clinical trials among general population of northern KSA, to identify the factors associated with poor knowledge and attitude among them. Furthermore, we measured the correlation between knowledge and attitude among the study population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

The current analytical cross-sectional study was conducted among the general population of Aljouf Province of the KSA from April 2021 to May 2022. Aljouf Province is situated in the northern part of the KSA with a population of approximately half a million.

2.2. Sample Size Estimation and Sampling Method

We used the World Health Organization’s (WHO) sample size calculator with the expected population proportion of 50%, design effect of 1, 95% confidence interval (CI), 5% margin of error, and an 80% study power. Considering these measurements, we concluded that 384 was the minimum participants required for this population-based survey. However, the research team took an additional 25%; thus, the final estimated sample size was 480. Using consecutive sampling methods, we recruited 480 participants for the present study. Using this method, the research team collected data from different public places, such as malls, parks, and supermarkets.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The present study included participants aged 18 years and over who belonged to Aljouf Province. We excluded those who were less than 18 years of age, healthcare workers, health science college students, and those who were mentally ill.

2.4. Data Collection

After ethical approval from the local committee of bioethics from Jouf University (approval no: 06-06-41) and other necessary approvals, the survey team initiated the data collection process. The data collector for the current research visited public places and invited participants as per the inclusion criteria. In order to recruit participants for all days of the week, the number of invited participants per day was limited to 50. We briefed them on the purpose of the study, the participants, their roles in the survey, the benefits, risks, and whom to communicate with for further details. After obtaining their willingness to participate through informed consent, the coinvestigators requested the selected person to fill out the data collection form (Google workspace form) on the research team’s electronic gadgets (mobiles, Tab, etc.). The data collection proforma did not include any identifying details of the participants (deidentified data). Hence, we maintained the anonymity of the participants. Furthermore, we maintained the COVID-19 prevention procedures as given by the concerned authorities. After completing the survey, the research team provided the participants with health education related to CTs. We developed the Arabic version of the data collection form based on open-source pieces of existing literature [16,17,19].

The experts from clinical research, clinical pharmacology, and public health entities extracted and finalized the contents in the first stage (i.e., face and content validity). Next, two bilingual (English–Arabic) experts translated the CT questionnaire into Arabic. Furthermore, another set of nonmedical bilingual persons conducted a back translation process. Finally, the original English version and the back-translated version were compared for similarity. We gave the final Arabic version questionnaire to a randomly selected 30 participants from the general population for pilot testing. The participants from the pilot study population provided feedback to ensure all questions on the data collection form were clear. Furthermore, the pilot study analysis did not find any missing data. The construct validity was assessed with the pilot study’s responses. The Cronbach’s alpha (α) value of the developed questionnaire was 0.81 for knowledge (test–retest, r = 0.89; split-half = 0.91) and 0.86 for the attitude section (test–retest, r = 0.86; split-half = 0.90). Therefore, the team conducted the data collection with the pretested form. The data collection proforma consisted of three parts. The first part inquired about the sociodemographic details; the second and third part parts assessed the participants’ knowledge and attitude towards CTs. The research team followed all COVID-19 infection prevention strategies suggested by the Ministry of Health during the data collection process.

2.5. Calculation and Categorization of Knowledge and Attitude Score

The knowledge section consisted of 12 questions in which a participant’s correct score was calculated as 1, and wrong/not sure were scored as 0 (the answer key to the correct/wrong scores were available for the principal investigators and coinvestigators, and it was entered accordingly for statistical analysis). The attitude section consisted of 9 questions in which a participant’s positive answer was calculated as 1, and a no/not sure/negative answer was scored as 0. The total scores were combined and converted to 100 percent. The knowledge and attitude percentages were subclassified into three categories: excellent (≥80% of possible score), moderate (60–79% of possible score), and low (<60% of possible scores). Furthermore, we combined low and medium categories as a single category. We compared them with the excellent category according to Bloom’s criteria, commonly used criteria to categorize the knowledge, attitude, and practice of the public for the health-related surveys [17,21].

2.6. Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 20.0, was used to enter and analyze the data. Descriptive statistics are presented as the frequency and percentage, and continuous data are depicted as the mean and standard deviation (SD). Knowledge and attitude scores were tested for normal distribution by Shapiro–Wilk analysis. The correlation between knowledge and attitude scores was tested through Spearman’s correlation test. The univariate analysis of the present study was performed through the Chi-square test, and multivariable analysis was executed by the binomial logistic regression analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical tests used in this research were two-tailed.

3. Results

We contacted 550 eligible individuals during the data collection period. Of the 550 individuals, 480 eligible participants provided consent to participate in the present survey (response rate = 87.27%). Of the 480 studied individuals, the majority (63.5%) were male, currently married (75.2%), working in public sectors (40.6%), with an education level of university or above (62.7%), and 84.8% of them never participated in any health research (Table 1).

Table 1.

Background and health-related characteristics of the participants (n = 480).

| Variable | Number (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | Less than 30 years 30 to 45 years Above 45 years |

190 165 125 |

39.6 34.4 26.0 |

| Gender | Male Female |

305 175 |

63.5 36.5 |

| Marital status | Married Unmarried * |

361 119 |

75.2 24.8 |

| Employment status | Public sector job Private job/self-employed/business Unemployed Retired |

195 111 102 72 |

40.6 23.1 21.3 15.0 |

| Education level | Up to high school University level |

179 301 |

37.3 62.7 |

| Income ** | Less than SAR 5000 SAR 5000 to 10,000 More than SAR 10,000 |

161 172 147 |

33.5 35.8 30.6 |

| Presence of any chronic diseases | Yes No |

124 356 |

25.8 74.2 |

| Previous participation in health research | Yes No |

73 407 |

15.2 84.8 |

* Unmarried: single, divorced, separated, and widowed. ** USD 1 = 3.75.

The participants’ knowledge-related responses are depicted in Table 2. Nearly two-thirds (64.6%) of them had never heard of CT, and 56.3% were aware of the Saudi FDA. Regarding the CT implementation process, most participants believed that the research team could initiate CT on patients without written consent, and 65% of the participants responded that the participants could withdraw at any time during the CT process. The mean ± SD score of the knowledge section was 7.10 ± 2.03.

Table 2.

Responses of the participants for the knowledge items (n = 480).

| Item | Number (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you ever heard about clinical trials (CTs)? | Yes No/not sure |

170 310 |

35.4 64.6 |

| Definition of a CT | Correct answer Wrong answer |

192 288 |

40.0 60.0 |

| Have you heard of an ethics review committee for a CT? | Yes No |

93 387 |

19.4 80.6 |

| Have you heard about the Saudi FDA? | Yes No |

270 210 |

56.3 43.7 |

| Does the general authority of food and drug administration have any role in CT’s policy? | Yes No |

376 104 |

78.3 21.7 |

| Are there any ethical guidelines to regulate CTs? | Yes No |

398 82 |

82.9 17.1 |

| Is there a direct benefit to the participants in CTs? | Correct answer Wrong answer |

98 382 |

20.4 79.6 |

| Is there a direct benefit to the Saudi community due to the people participating in CTs? | Yes No |

415 65 |

86.5 13.5 |

| When can the research team start a CT? | Correct answer Wrong answer |

235 245 |

49.0 51.0 |

| Can the research team initiate the CT without the consent of the participants? | Yes No |

436 44 |

90.8 9.2 |

| Are the participants free to withdraw from the CT at any time? | Yes No |

312 168 |

65.0 35.0 |

| Patients’ confidential information (such as name) can be disclosed in the published article? | Yes No |

183 297 |

38.1 61.9 |

| Total knowledge score (mean ± SD) | 7.10 ± 2.03 | ||

Regarding attitude-related responses, only 24.2% of the respondents agreed to test a new drug on the patients. However, approximately two-thirds (66.7%) of them agreed to test an approved drug on the patients. The majority (88.1%) of the participants denied agreeing to test a new drug on pediatric patients. The mean ± SD of the attitude score was 4.38 ± 2.04 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participants’ responses in each attitude section (n = 480).

| Item | Number (n) | Percentage % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you agree to test a new experimental non-approved drug on patients? | Yes No/not sure |

116 364 |

24.2 75.8 |

| Do you agree to test an already approved drugs on patients? | Yes No/not sure |

320 160 |

66.7 33.3 |

| Do you agree to test a new experimental drug on healthy volunteers? | Yes No/not sure |

256 224 |

53.3 46.7 |

| Do you agree to test a new experimental drug on child patients? | Yes No/not sure |

57 423 |

11.9 88.1 |

| Do you agree to test an already approved drug on child patients? | Yes No/not sure |

221 259 |

46.0 54.0 |

| Are you willing to participate in a CT? | Yes No/not sure |

56 424 |

11.7 88.3 |

| Do you want to know more about CT? | Yes No |

359 121 |

74.8 25.2 |

| What is your perception towards CT? | Positive answer Negative answer |

309 171 |

64.4 35.6 |

| Would you trust the research team which is conducting the CT? | Yes No/not sure |

360 120 |

75.0 25.0 |

| Total attitude score | 4.38 ± 2.04 | ||

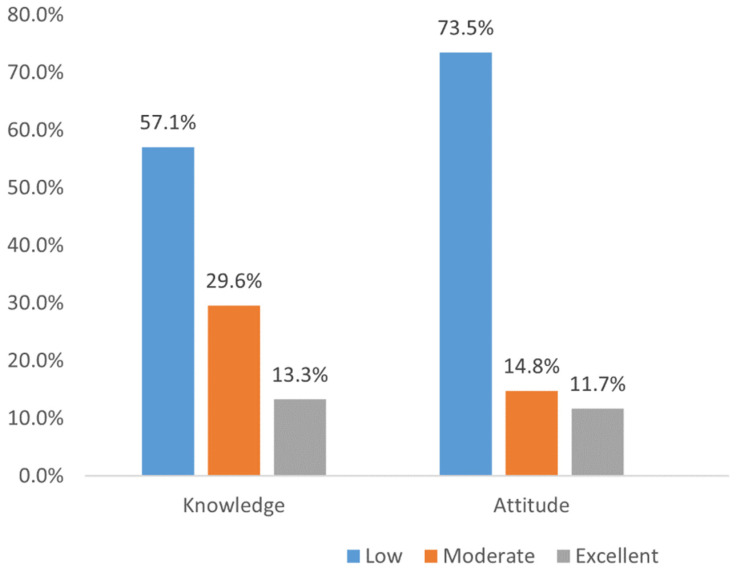

Of the studied population, 13.3% and 11.7% had excellent knowledge and attitudes towards CT. The remaining participants belonged to either the poor or moderate categories (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Knowledge and attitude categories (n = 480).

The participants’ background characteristics and their association with the knowledge and attitude scores are presented in Table 4. The participants’ knowledge scores were significantly associated with education level (p = 0.006) and their previous participation in health-related research (p = 0.005). The attitude scores were significantly related to marital status (p = 0.019) and the presence of chronic diseases (p = 0.006).

Table 4.

Participants’ characteristics and their association with knowledge and attitude categories (n = 480). Test applied: chi-square test.

| Variable | Knowledge | Attitude | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Low and Moderate (n = 416) |

Excellent (n = 64) |

p-Value | Low and Moderate (n = 424) |

Excellent (n = 56) |

p-Value | ||

| Age group (years) | Less than 30 years 30 to 45 years Above 45 years |

190 165 125 |

159 (83.7) 149 (90.3) 108 (86.4) |

31 (16.3) 16 (9.7) 17 (13.6) |

0.187 | 163 (85.8) 149 (90.3) 112 (89.6) |

27 (14.2) 16 (9.7) 13 (10.4) |

0.366 |

| Gender | Male Female |

305 175 |

266 (87.2) 150 (85.7) |

39 (12.8) 25 (14.3) |

0.369 | 268 (87.9) 156 (89.1) |

37 (12.1) 19 (10.9) |

0.397 |

| Marital status | Married Unmarried |

361 119 |

314 (87.0) 102 (85.7) |

47 (13.0) 17 (14.3) |

0.415 | 326 (90.3) 98 (82.4) |

35 (9.7) 21 (17.6) |

0.019 * |

| Employment status | Public sector job Private job/self-employed Unemployed Retired |

195 111 102 72 |

173 (88.7) 92 (82.9) 91 (89.2) 60 (83.3) |

22 (11.3) 19 (17.1) 11 (10.8) 12 (16.7) |

0.512 | 175 (89.7) 100 (90.1) 85 (83.3) 64 (88.9) |

20 (10.3) 11 (9.9) 17 (16.7) 8 (11.1) |

0.461 |

| Education level | Up to high school University or higher |

179 301 |

165 (92.2) 251 (83.4) |

14 (7.8) 50 (16.6) |

0.006 * |

158 (88.3) 266 (88.4) |

21 (11.7) 35 (11.6) |

0.973 |

| Income ** (monthly) | Less than SAR 5000 SAR 5000 to 10,000 More than SAR 10,000 |

161 172 147 |

137 (85.1) 145 (84.3) 134 (91.2) |

24 (14.9) 27 (15.7) 13 (8.8) |

0.154 |

143 (88.8) 152 (88.4) 129 (87.8) |

18 (11.1) 20 (11.6) 18 (12.2) |

0.958 |

| Presence of any chronic diseases | Yes No |

124 356 |

103 (83.1) 313 (87.9) |

21 (16.9) 43 (12.1) |

0.113 | 101 (81.5) 323 (90.7) |

23 (18.5) 33 (9.3) |

0.006 * |

| Previous participation in health research | Yes No |

73 407 |

54 (74.0) 362 (88.9) |

19 (26.0) 45 (11.1) |

0.005 * | 60 (82.2) 364 (89.4) |

13 (17.8) 43 (10.6) |

0.206 |

* Significant value (p < 0.05). ** 1 USD = SAR 3.75.

We ran a binary logistic regression to find the categories of factors associated with knowledge and attitude of CTs. After adjusting with the other covariables of the present study, we found that the knowledge category was significantly associated with education level (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.73, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.15–2.84, p = 0.031) and previous participation in health research (AOR = 0.63, 95 CI = 0.47–0.89, p = 0.007). The attitude category was significantly associated with marital status (AOR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.17–2.98, p = 0.035) and the presence of any chronic diseases (AOR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.54–0.91, p = 0.008) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with the northern Saudi general population’s knowledge and attitude towards CTs. The test applied: binomial logistic regression analysis (n = 480).

| Variables | Knowledge (Poor and Moderate vs. Excellent) |

Attitude (Poor and Moderate vs. Excellent) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) **/95% Confidence Interval (CI) | p-Value | AOR ** (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| Age group (years) | Less than 30 years 30 to 45 years Above 45 years |

Ref. 0.56 (0.29–1.09) 0.79 (0.41–1.54) |

0.088 0.500 |

Ref. 0.66 (0.38–1.31) 0.73 (0.35–1.50) |

0.238 0.389 |

| Gender | Male Female |

Ref. 1.12 (0.63–2.01) |

0.704 |

Ref. 1.02 (0.54–1.91) |

0.960 |

| Marital status | Married Unmarried |

Ref. 1.14 (0.61–2.11) |

0.689 |

Ref. 1.84 (1.17–2.98) |

0.035 * |

| Employment status | Public sector job Private job/self-employed Unemployed Retired |

Ref. 1.24 (0.50–3.06) 0.98 (0.44–2.18) 1.48 (0.58–3.74) |

0.637 0.951 0.411 |

Ref. 0.48 (0.19–1.20) 0.54 (0.26–1.15) 0.55 (0.21–1.44) |

0.117 0.111 0.225 |

| Education level | Up to high school University or higher |

Ref. 1.73 (1.15–2.84) |

0.031 * |

Ref. 1.15 (0.60–2.18) |

0.677 |

| Income (monthly) | Less than SAR 5000 SAR 5000 to 10,000 More than SAR 10,000 |

Ref. 0.62 (0.31–1.19) 1.58 (0.79–2.74) |

0.148 0.728 |

Ref. 1.06 (0.57–1.98) 0.91 (0.53–2.11) |

0.854 0.512 |

| Presence of any chronic diseases | Yes No |

Ref. 0.66 (0.37–1.18) |

0.159 |

Ref. 0.71 (0.54–0.91) |

0.008 * |

| Previous participation in health research | Yes No |

Ref. 0.63 (0.47–0.89) |

0.007 * |

Ref. 0.49 (0.23–1.04) |

0.062 |

* Significant value (two-tailed). ** Adjusted variables in logistic regression (enter method) age group, gender, married status, employment status, education level, income, presence of chronic diseases, and previous participation in health research.

We found a significant positive correlation (applied test: Spearman’s correlation test) between knowledge and attitude scores (p < 0.001, rho = 0.329) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlation between participants knowledge and attitude towards CT (n = 480). Test applied: Spearman’s correlation test.

| Spearman’s Coefficient Value (rho) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge–Attitude | 0.329 | <0.001 * |

* Significance: p-value < 0.05 (two-tailed test).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to assess the northern Saudi general population’s knowledge, attitude, and associated factors towards CT. This population-based study revealed that the knowledge regarding CTs was generally low in several statements. We found that nearly two-thirds (64.6%) of the participants had never heard of CTs. Similar to the present study, Al-Lawati et al. (Oman) and Al Rawashdeh et al. (KSA) found that their study participants had a low level of awareness about CTs [16,17]. Interestingly, a survey conducted in 2022 in the USA reported that a lower proportion (41.7%) of participants was unaware of CTs [22]. A recent survey conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in the KSA by Alqahtani et al. also supports our findings. In their study, the awareness results concerning ethics committees and consent requirements were similar to the present study [23].

We categorized the knowledge score as per Bloom’s criteria [17,21]. The present study showed that most of the northern Saudi general population had either low (57.1%) or moderate (29.6%) overall knowledge scores. Some recently concluded surveys also reported similar findings [20,24,25]. However, a Jordanian study and a study conducted in the USA found that most of their study participants had moderate to good knowledge of CTs [22,26]. Possible variations between studies could be attributed to the differences including the study settings, sociocultural factors, and survey tools. We found that level of education was a significant factor associated with knowledge of CTs (p = 0.031). Interestingly, we did not find any other sociodemographic characteristics related to the participants’ knowledge. Similarly, Altaf et al. and Awwad et al. reported that people with higher education had significantly better knowledge of CT than others [20,26]. In contrast, Al Rawashdeh et al. and Ahram et al. reported that knowledge was significantly associated with other factors, namely, age group, gender, income, and employment status [17,27]. However, their report of an association with previous participation in health-related research was similar to our study.

A positive attitude is essential among the population to participate in CTs. It can encourage people to participate in CTs. Furthermore, a positive attitude is similar to infections and spreads among other family and community members [28,29]. However, we found that most of the participants had a low (73.5%) or moderate attitude towards CTs (14.8%). Our findings are supported by some studies in the KSA and other parts of the world, although a few studies reported a moderately positive attitude towards CTs [16,18,30,31]. This indicates that a poor attitude towards participating in CTs is a global phenomenon and needs immediate attention from stakeholders. Our population-based study revealed that a positive attitude was significantly higher among unmarried participants (p = 0.035) and the presence of chronic diseases (p = 0.008). Similar to the present study, several authors found that the presence of chronic diseases such as cancer might be a significant factor for participating in a CT [17,32]. This could be due to the increased sensitization among the patients, who might be looking for better treatment for their chronic diseases. Although CTs among healthy volunteers is equally important, as they can act as comparative groups and for prevention-based trials, the attitude among them is very low [33,34]. Another important factor revealed by the present study was marital status. A possible explanation is that currently married people might be thinking of commitments with family in the event of negative consequences due to the fact of their participation in a CT. The current survey found a positive correlation between participants’ knowledge and attitude scores (p < 0.001, rho = 0.329). The results of the present study in this context were similar to other studies, which also indicated a positive correlation between the population’s knowledge and attitude [17,26].

We performed this population-based cross-sectional survey in northern Saudi during the COVID-19 era with a standard and validated tool. However, the current survey has some limitations. First, we applied a questionnaire-based cross-sectional design, and the constraints related to this design must be considered while interpreting the findings of the current survey, such as recall bias and exaggerated responses. Next, we utilized a consecutive sampling method. Hence, the possibility of selection bias cannot be avoided. In addition, due to the wide sociocultural variation across the country (KSA), the present research findings cannot be generalized to the entire Saudi general population and other Middle East countries. Finally, the utilized study design attempted to find the association not the causation.

5. Conclusions

The present study revealed that most of the population has poor knowledge and moderate attitudes towards CTs. The knowledge categories were significantly associated with educational level, and the attitude categories were significantly associated with the presence of chronic diseases and marital status. Furthermore, we found a positive correlation between knowledge and attitude scores. Hence, we recommend improving the public’s knowledge of the importance of CT participation. This can be achieved through targeted health education programs at different public places. Such health education programs would improve the perceptions and attitude of the general population to participate in CTs, which is much needed for new drug development. Considering the present study’s limitations, we suggest an exploratory and mixed-methods survey in other regions of KSA to recognize region-specific health education needs.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Amal Fahad Almunahi and Abdulelah Ayad Alruwaili for their help in the research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., A.E.T., A.L.M.A. and W.S.S.A.; methodology, A.T., M.A., N.S.A., F.K.S.A. and A.A.A.A.; software, A.T., W.S.S.A. and A.E.T.; validation, M.A., A.T., A.L.M.A. and W.S.S.A.; formal analysis, A.T.; investigation, F.K.S.A. and A.A.A.A.; resources, M.A. and A.E.T.; data curation, A.T., W.S.S.A., N.S.A., F.K.S.A., A.A.A.A. and A.L.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A., A.T., W.S.S.A. and F.K.S.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A.A.A., N.S.A., A.L.M.A. and A.E.T.; visualization, N.S.A. and A.T.; supervision, M.A.; project administration, M.A.; funding acquisition, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Local Bioethics committee of Jouf University (approval no: 06-06-41).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study will be provided by the principal investigator upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Jouf University, under grant No. (DSR-2021-01-03163).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) [(accessed on 15 January 2022)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform.

- 2.Hariton E., Locascio J.J. Randomised controlled trials—The gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: Randomised controlled trials. Bjog. 2018;125:1716. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John K.S., McNeal K.S. The Strength of Evidence Pyramid: One Approach for Characterizing the Strength of Evidence of Geoscience Education Research (GER) Community Claims. J. Geosci. Educ. 2017;65:363–372. doi: 10.5408/17-264.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pascual M.A., Fors M.M., Jiménez G., López I., Torres A. Public health approach of clinical trials: Cuban’s experience of research translation into clinical practice. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014;14:P149. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-S2-P149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landray M.J., Bax J.J., Alliot L., Buyse M., Cohen A., Collins R., Hindricks G., James S.K., Lane S., Maggioni A.P., et al. Improving public health by improving clinical trial guidelines and their application. Eur. Heart J. 2017;38:1632–1637. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unger J.M., Xiao H. The COVID-19 pandemic and new clinical trial activations. Trials. 2021;22:260. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05219-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Psotka M.A., Abraham W.T., Fiuzat M., Filippatos G., Lindenfeld J., Ahmad T., Bhatt A.S., Carson P.E., Cleland J.G.F., Felker G.M., et al. Conduct of Clinical Trials in the Era of COVID-19: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;76:2368–2378. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang G.D., Bull J., Johnston McKee K., Mahon E., Harper B., Roberts J.N. Clinical trials recruitment planning: A proposed framework from the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2018;66:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali S., Alghamdi M.A., Alzhrani J.A., De Vol E.B. Magnitude and characteristics of clinical trials in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional analysis. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2017;7:126–129. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US-FDA Drug Trials Snapshots Summary Report Five-Year Summary and Analysis of Clinical Trial Participation and Demographics Contents. [(accessed on 12 October 2022)]; Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/143592/download.

- 11.ClincalTrials.Gov Trends, Charts, and Maps of Clinical Trials Participation. [(accessed on 15 February 2021)]; Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/resources/trends.

- 12.Nair S.C., Ibrahim H., Celentano D.D. Clinical trials in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region: Grandstanding or grandeur? Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2013;36:704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thoma A., Farrokhyar F., McKnight L., Bhandari M. Practical tips for surgical research: How to optimize patient recruitment. Can. J. Surg. 2010;53:205–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh A.G., Chaturvedi P. Clinical trials during COVID-19. Head Neck. 2020;42:1516–1518. doi: 10.1002/hed.26223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassi A., Arfin S., Joshi R., Bathla N., Hammond N.E., Rajbhandari D., Tirupakuzhi Vijayaraghavan B.K., Venkatesh B., Jha V. Challenges in operationalising clinical trials in India during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Glob. Health. 2022;10:e317–e319. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00546-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Lawati H., Al-Baimani K., Al-Zadjali M., Al-Obaidani N., Al-Kiyumi Z., Al-Khabori M.K. Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Clinical Trial Participation in Oman: A cross-sectional study. Sultan. Qaboos. Univ. Med. J. 2018;18:e54–e60. doi: 10.18295/squmj.2018.18.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Rawashdeh N., Damsees R., Al-Jeraisy M., Al Qasim E., Deeb A.M. Knowledge of and attitudes toward clinical trials in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031305. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel E.U., Zhu X., Quinn T.C., Tobian A.A.R. Public Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Clinical Trials in the COVID-19 Era. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022;62:469–471. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Tannir M.A., Katan H.M., Al-Badr A.H., Al-Tannir M.M., Abu-Shaheen A.K. Knowledge, attitudes, practices and perceptions of clinicians towards conducting clinical trials in an Academic Tertiary Care Center. Saudi Med. J. 2018;39:191–196. doi: 10.15537/smj.2018.2.21093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altaf A., Bokhari R., Enani G., Judeeba S., Hemdi A., Maghrabi A., Tashkandi H., Aljiffry M. Patients’ attitudes and knowledge toward clinical trial participation. Saudi Surg. J. 2019;7:69–74. doi: 10.4103/ssj.ssj_23_19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feleke B.T., Wale M.Z., Yirsaw M.T. Knowledge, attitude and preventive practice towards COVID-19 and associated factors among outpatient service visitors at Debre Markos compressive specialized hospital, north-west Ethiopia, 2020. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0251708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yadav S., Todd A., Patel K., Tabriz A.A., Nguyen O., Turner K., Hong Y.-R. Public knowledge and information sources for clinical trials among adults in the USA: Evidence from a Health Information National Trends Survey in 2020. Clin. Med. 2022;22:416–422. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2022-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alqahtani A.M., Almazrou S.H., Alalweet R.M., Almalki Z.S., Alqahtani B.F., AlGhamdi S. Impact of COVID-19 on Public Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Participating in Clinical Trials in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021;14:3405–3413. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S318753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elshammaa K., Hamza N., Elkholy E., Mahrous A., Elnaem M., Elrggal M. Knowledge, attitude, and perception of public about participation in COVID-19 clinical trials: A study from Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022;30:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2022.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosconi P., Roberto A., Cerana N., Colombo N., Didier F., D’Incalci M., Lorusso D., Peccatori F.A., Artioli G., Cavanna L., et al. Knowledge and attitudes towards clinical trials among women with ovarian cancer: Results of the ACTO study. J. Ovarian Res. 2022;15:45. doi: 10.1186/s13048-022-00970-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awwad O., Maaiah S., Almomani B.A. Clinical trials: Predictors of knowledge and attitudes towards participation. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021;75:e13687. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahram M., Farkouh A., Haddad M., Kalaji Z., Yanis A. Knowledge of, attitudes to and participation in clinical trials in Jordan: A population-based survey. East Mediterr. Health J. 2020;26:539–546. doi: 10.26719/2020.26.5.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrade G. The ethics of positive thinking in healthcare. J. Med. Ethics Hist. Med. 2019;12:18. doi: 10.18502/jmehm.v12i18.2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eagleson C., Hayes S., Mathews A., Perman G., Hirsch C.R. The power of positive thinking: Pathological worry is reduced by thought replacement in Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2016;78:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Staniszewska A., Lubiejewska A., Czerw A., Dąbrowska-Bender M., Duda-Zalewska A., Olejniczak D., Juszczyk G., Bujalska-Zadrożny M. Awareness and attitudes towards clinical trials among Polish oncological patients who had never participated in a clinical trial. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018;27:525–529. doi: 10.17219/acem/68762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson A., Borfitz D., Getz K. Global Public Attitudes about Clinical Research and Patient Experiences with Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw. Open. 2018;1:e182969. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taafaki M.R., Brown A.C., Cassel K.D., Chen J.J., Lim E., Paulino Y.C. Knowledge and Attitudes of Guam Residents towards Cancer Clinical Trial Participation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:15917. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192315917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.NIH Why Should I Participate in a Clinical Trial? [(accessed on 19 December 2022)]; Available online: https://www.nih.gov/health-information/nih-clinical-research-trials-you/why-should-i-participate-clinical-trial#:~:text=Healthy%20volunteers%20say%20they%20participate,from%20the%20clinical%20trial%20staff.

- 34.Ranjan R., Agarwal N.B., Kapur P., Marwah A., Parveen R. Factors Influencing Participation of Healthy Volunteers in Clinical Trials: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study in Delhi, North India. Patient Prefer. Adherence. 2019;13:2007–2015. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S206728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study will be provided by the principal investigator upon request.