Abstract

Recent observations suggest a role of the choroid plexus (CP) and cerebral ventricle volume (CV), to identify treatment resistance of major depressive disorder (MDD). We tested the hypothesis that these markers are associated with clinical improvement in subjects from the EMBARC study, as implied by a recent pilot study. The EMBARC study characterized biological markers in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of sertraline vs. placebo in patients with MDD. Association of baseline volumes of CV, CP and of the corpus callosum (CC) with treatment response after 4 weeks treatment were evaluated. 171 subjects (61 male, 110 female) completed the 4 week assessments; gender, site and age were taken into account for this analyses. As previously reported, no treatment effect of sertraline was observed, but prognostic markers for clinical improvement were identified. Responders (n = 54) had significantly smaller volumes of the CP and lateral ventricles, whereas the volume of mid-anterior and mid-posterior CC was significantly larger compared to non-responders (n = 117). A positive correlation between CV volume and CP volume was observed, whereas a negative correlation between CV volume and both central-anterior and central-posterior parts of the CC emerged. In an exploratory way correlations between enlarged VV and CP volume on the one hand and signs of metabolic syndrome, in particular triglyceride plasma concentrations, were observed. A primary abnormality of CP function in MDD may be associated with increased ventricles, compression of white matter volume, which may affect treatment response speed or outcome. Metabolic markers may mediate this relationship.

Introduction

The pathophysiology of major depressive disorder (MDD) is heterogeneous. The identification of effective compounds on the basis of a specific underlying neurobiology is hampered by the currently accepted definition of MDD in relevant classifications, including the DSM-5, which does not take biological differentiation into account. Importantly, this variability may not only affect the response to a given pharmacotherapy, but also the natural course of clinical change. This situation has negative implications in the context of clinical trials, in which treatment arms are compared, which may show neurobiological heterogeneity at baseline. To stratify a population on the basis of biological variables would confirm a biologically defined subtype, which is suitable for the treatment of a specific nature.

An argument, which is often brought up as a challenge is the operational complexity of such an approach. However, broadly available and easily accessible biological markers are available. Markers, which are available and have been shown to differentiate patients with depression include inflammatory markers1–5, metabolic markers, in particular those related to metabolic syndrome5, 6, and neuroendocrine1, 7, 8 characteristics. More recently, markers of autonomic regulation, including blood pressure and heart rate variability received renewed attention9–12.

Furthermore, imaging biomarkers have been characterized to differentiate the subjects with presumed different clinical response. Many of these, including volumetry of gray- or white matter segments are of high importance from a research perspective, but are difficult to assess in standard practice13, 14. A more easily accessible imaging marker, which is unfortunately frequently not reported in recent imaging studies, is cerebral ventricular volume (VV), partially by the argument that changes in ventricular volume are biologically unspecific, as many different brain areas may contribute to this phenomenon. Here we explore the alternative hypothesis that choroid plexus driven ventricular expansion results in the compression surrounding anatomical areas, making ventricular volume changes the potential primary factor. In the context of depression, VV is increased in patients with depression in comparison to healthy controls15–17 and may be related to treatment outcome18. We recently demonstrated an association between an increased choroid plexus and ventricular volume and worse treatment outcome in hospitalized patients with depression and identified moderators of this relationship19, i.e. body mass index (BMI) and the salivary aldosterone/cortisol ratio. The effect may be mediated by a compression of of corpus callosum segments, which will affect anatomical projection areas.

In this context it is important to consider that VV and the volume of the corpus callosum show short term structural plasticity. Both underly sleep-related changes20 and VV is sensitive to stress, at least in animals21. A plausible mediator of these phenomena is again the change in activity of the choroid plexus (CP). The volumetric determination of the CP is a relatively new area of investigation, but is feasible with current MRI techniques. Changes have been described in complex pain syndrome22, anorexia nervosa23, multiple sclerosis24 and most recently in major depression25 and psychosis26. Mechanistically, stress leads in an animal model to changes in gene expression of the CP of receptors, which have been linked to MDD, including 5-HT2a, 5-HT2c, glucocorticoid, TNFα, IL1β, BDNF27 as well as IL1 receptor28 and the CRH-receptor29. The choroid plexus may play a role in inducing inflammatory changes in depression and may be involved in sickness behavior2. Downstream mechanisms of the involvement of the CP are therefore at least twofold: an increased CSF release may lead to a mechanical compression of anatomical areas, which are adjacent to the ventricles30. Secondly, molecular moderators may spread into brain tissue via volume transmission31, 32. Those moderators may be produced by the CP itself or stem from the circulation.

We want to replicate our earlier findings of the relationship between clinical outcome of patients with depression on the one hand and ventricular volume, choroid plexus function and corpus callosum volume in a larger sample in this retrospective analysis from data from the EMBARC study. In an exploratory way we also correlate metabolic and autonomic markers with the volume of these anatomical areas in order to generate hypothesis of the causality of the observed relationships.

Methods

The EMBARC study characterized biological markers in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of sertraline vs. placebo in patients with MDD for 8 weeks, followed by an additional treatment section, based on the outcome of the first 8 weeks of treatment. For consort statement see33. This trial is conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each clinical site. Signed informed consent was obtained from subjects in order to participate in the trial. The main objective was to identify clinical and biological moderators of treatment response34. Patients with early onset (before age 30), chronicity (episode duration > 2 years) or recurrent MDD (two or more recurrences including current episode) were enrolled.

The clinical parameter of interest was the Hamilton-depression rating scale (17 item; HAMD-17). For correlational analysis of clinical improvement we used the ratio between the HAMD-17 at outcome divided to the HAMD-17 at baseline (HAMD-17 ratio). A value of 1 means no change from baseline, a value of 0.7 means a reduction to 70% of the baseline value. Response was defined as a HAMD-17 ratio ≤ 0.5.

For these primary analyses we focused on subjects, who completed the first 4 weeks of the placebo-controlled treatment phase. In the current dataset, 207 subjects had assessments with the Hamilton depression rating scale (HAMD) at baseline, of which 171 (; age 37.5 ± 13.4; HAMD-17: 18.8 ±4.7) had an assessment at week 4. We a priori chose the 4-week treatment interval in order to optimize the time for clinical improvement with the number of drop-outs. For a time course of the correlation of the HAMD-17 value with imaging parameters, which we generated as a sensitivity analysis and to show consistency, please see Table S1.

Imaging was processed as described before34, 35. Of the subjects, who completed 4 weeks of treatment, 171 also had imaging data at baseline. Association of volumes of CV, CP and of the corpus callosum (CC), with treatment response were evaluated. The relationship of the volume of choroid plexus, cerebral ventricular volumes and the corpus callosum with response after 4 weeks from baseline (≤50 % reduction of the HAMD) was assessed; gender, age, and total brain volume were taken into account for the primary MANCOVA analysis. For the analysis of correlations Pearson correlation coefficients and p-values are provided. The relationship between the volumes of the choid plexus- and ventricular volumes should be regarded as primary analysis, as this analysis serves to replicate our earlier findings. As the anatomical parameters of interest are considered to be highly correlated and therefore not independent correction for multiple testing was not performed. The correlations with metabolic and autonomic parameters have to be regarded as exploratory.

Results

A correlation between baseline HAMD-17 and the volumes of interest was performed in order to determine potential state related effects. Choroid plexus volumes were significantly correlated with the HAMD-17 score at baseline (n = 217; right: Pearson R: 0.22, p = 0.002; left: Pearson R = 0.17, p = 0.017), whereas no correlation between ventricular volumes or corpus callosum sections and baseline depression severity could be detected (all p > 0.20 with the exception of the right lateral ventricle, which showed a trend toward a significant correlation (Pearson R = 0.13; p = 0.06).

Regarding the analysis of factors related to treatment outcome: No statistically significant treatment effect of sertraline was observed, as reported earlier36, but prognostic markers for therapy response were identified. Therefore, treatment was not a factor of the analyses. Comparing responders and non-responders, we adjusted for gender and age. An overall global significant difference between responders and non-responders was observed for volumetric parameters (p = 0.007, see table 2). Univariate analyses revealed that responders at week 4 had significantly smaller volumes of the choroid plexi and lateral ventricles, whereas the volume of mid-anterior and mid-posterior CC was significantly larger compared to non-responders (Table 2).

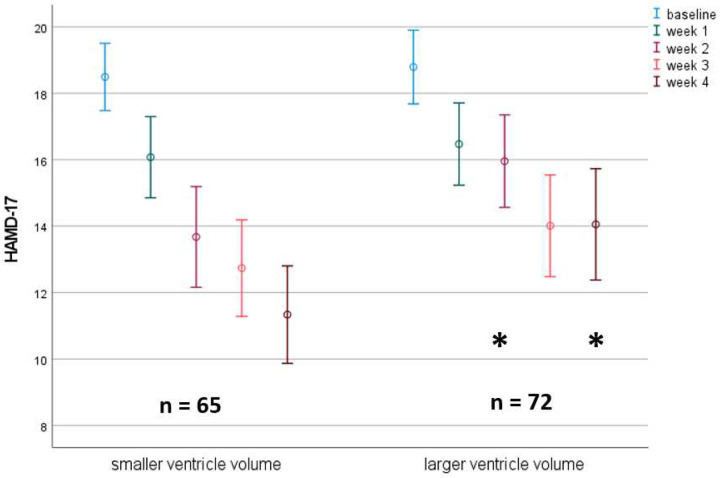

Vice versa, splitting the population at the median for the ventricular volume demonstrates the difference of the course of depressive symptoms between the two VV groups clearly (Fig. 1): A significant difference between HAMD-17 scores for the high vs. low VV-volume groups were observed at week 2 and week 4.

Figure 1:

Time course of HAMD-17 score in subjects with larger vs. smaller right lateral ventricle volume. A median split was used to separate the groups. Only subjects without missing values are depicted.

As a sensitivity analysis we also compared the anatomical structures split into responders vs. non-responders for each timepoint of the study, up to 8 weeks. Choroid plexus volumes at baseline differentiated these groups starting at week 4 up to week 8 (p < 0.05), however, other parameters did not reach statistical significance past week 4. Please see suppl. Table S1 for the stability of the correlation between volume of anatomical structures and treatment effect over time.

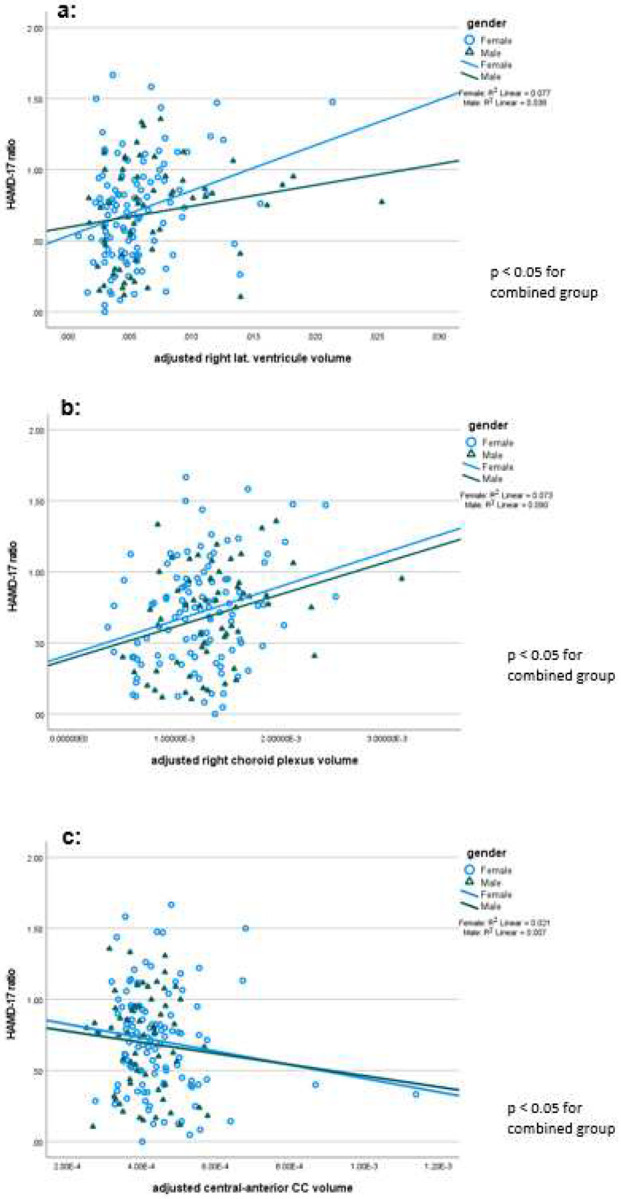

In addition to the comparisons between responders and non-responders correlations between baseline parameters and the HAMD-17 ratio were performed, which is independent of a chosen cut off. These correlational analyses confirmed the relationship between clinical change on one hand and ventricular volume, choroid plexus volume and CC segment volumes at baseline on the other hand (Tab. 3, Fig. 2). These data as well as the previous ones confirm the difference between responders and non-responders regarding anatomical structures and therefore the results from our pilot study. In addition, we explored other factors, which may affect the volume of the anatomical arias in an exploratory fashion. These analyses, are part of Tab.3 and need replication. We found that the volumes of both lateral ventricles were positively correlated to LDL-cholesterol and triglyceride levels. The volume of the left VV was significantly correlated and the right VV showed a trend towards a significant correlation to systolic blood pressure. A similar pattern was observed for the CP volumes. All these parameters are also positively correlated to age, which we corrected for in the primary analysis.

Figure 2:

a) Correlation of HAMD-17 by right lateral ventricle volume: a larger ventricle volume is associated with less favorable clinical improvement after 4 weeks, independent of gender. b: Correlation of HAMD-17 by right lateral ventricle volume: A choroid plexus volume is associated with less favorable clinical improvement after 4 weeks, independent of gender. c: Correlation of HAMD-17 by central anterior CC volume ratio: A smaller CC volume is associated with less favorable clinical improvement after 4 weeks, independent of gender.

In order to determine the relationship between the anatomical areas of interest, ventricular volumes were correlated with CC segments and CP volumes. A significant positive correlation between CP volumes and lateral ventricle volumes was established. More importantly, a significant negative correlation between third ventricular volumes and the mid-anterior and mid-posterior CC segments, as well as a significant negative correlation between the lateral ventricles and the mid-posterior CC volume were observed (Table S2).

DTI parameters as assessed for the corpus callosum did not predict outcome. However, the volume of the mid-anterior and mid posterior CC segments, adjusted for total brain volume, correlated negatively with the axial diffusivity of these segments (mid-anterior: R = −0.42, p < 0.001, n = 191; mid-posterior: R=−0.15; p =0.036, n = 196), whereas the CC-segment volumes were not associated with fractional anisotropy (for all, p > 0.1).

Discussion

The primary outcome of this study is that an easily accessible imaging marker, i.e. lateral ventricular volumes, show a strong predictive value for the improvement of depressive symptoms in MDD patients treated with either sertraline or placebo. Mechanistically, this appears to be related to an alteration in choroid plexus function, both of which may affect corpus callosum integrity.

The strong relationship of ventricular volume to choroid plexus volume on one hand and the volume of CC segments on the other hand could be of theoretical interest for the pathophysiology of some forms of MDD. A working hypothesis could be that changes in choroid plexus function, i.e. an increased release of CSF volume19, 37, or an increased release of specific bioactive molecules, including inflammation mediators24, 31, may lead to a change in white matter volume and/or integrity. The increased ventricular volume or, alternatively, such bioactive molecules may affect white matter function either by mechanical compression or an effect on white matter integrity via alternations of oligodendrocyte function. This could be related to changes in myelination or changes in the volume regulation of axons within the CC. Disturbance of white matter integrity has indeed frequently been described in patients with depressive disorders, mainly by using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) methods38–43. In support of the hypothesis of the choroid plexus involvement in this pathway: the activity of the choroid plexus is affected by neuroendocrine influences, which have been linked to MDD, in particular vasopressin and aldosterone19, 37, as well as metabolic markers related to an increased BMI19, 44. These findings are also in line with the role of inflammation as both aldosterone45–47 and high BMI48–51 show a close association to increased inflammation. Finally, inflammation has recently been associated with increased choroid plexus volume in patients with depression25 and multiple sclerosis24.

Our observation that the HDRS-17 score correlates significantly to choroid plexus volumes at baseline, only by trend to ventricular volumes and not to CC segment volumes implies that choroid plexus volume shows a state characteristic, and that ventricular volume shows somewhat lesser plasticity in relationship to mood and may have a more trait/chronicity related characteristic. Corpus callosum segments volume furthermore appear mainly to be trait- or risk markers. As mentioned in the introduction, stress leads to an increase in ventricular volume in animals21. Childhood abuse has been related to later life increase ventricular volumes and reduced white matter volume52, 53 and also the therapy refractoriness in depression54, 55. This could imply that early life stress affects ventricular and white matter structure via a prolonged choroid plexus activation. However, a recent analysis, based on the self-report depression scale QIDS-SR did not confirm a difference regarding subjects with and without childhood adversity regarding clinical response56.

Other factors, which determine the size of the ventricles, which are potentially mediated via choroid plexus alterations are related to metabolic disorders. In particular, high fat diet is related to an increased ventricular volume in animals in the context of traumatic stress57. The finding of the correlation between triglyceride levels and systolic blood pressure at baseline on one hand and choroid plexus volumes and ventricular volumes on the other hand reported here confirm the influence of metabolic parameters to differentiate patients with depression1. Interestingly, and a link between increased ventricular volume and metabolic dysfunction, in particular hyperlipidemia, in subjects with normal pressure hydrocephalus58 has also been observed. Similarly, in our pilot study we previously described a strong correlation between BMI and both choroid plexus- and ventricular volume19.

As mentioned, markers of inflammation and metabolic disturbances are preferentially present in subjects with atypical depression, in comparison both to healthy subjects and patients with melancholic depression1, 59, 60. This is in line with the current findings, as atypical depression appears to be less responsive to standard antidepressant treatment61. Of importance, patients with atypical depression show in general an earlier age of onset62. The current study only enrolled patients with an age of onset ≤ 30 years, which means that there is probably an enrichment of this subtype in comparison to the general population. Age of onset appears to be associated with specific neurobiological differences in depression63, which may be related to alterations in autonomic function and endocrine characteristics. Whether age of onset also differentiates brain morphology needs further confirmation.

Regarding the relationship of DTI parameters, no relationship with clinical change was observed. This is in contrast to studies, which reported DTI parameters as predictive for response, for example to ketamine64, 65. Nevertheless, we observed that the volume of CC segments correlated inversely with axial diffusivity (AD), i.e. a smaller CC segment volume was correlated to an increased AD. An earlier DTI report from the EMBARC study, which focused on the structural connectivity in specific anatomical areas did find an increase in fractional anisotropy (FA) in non-remitters35. As AD and FA are correlated, this outcome appears consistent, but is nevertheless in contrast to a number of earlier cited findings39, 40, 42, 43, 66. This shows the importance to take into consideration that FA and AD and other DTI markers can be influenced by varying mechanisms, which depend on one hand on the structural integrity of an axon, but also an axonal density67.

Limitations of the study are the post hoc nature of the current analyses, however, they were motivated by the attempt to replicate data from an earlier study19 and the primary variables of interest are identical. Therefore, with all caution, the current analysis overall confirms the previous pilot study. It has, however, to be considered that inclusion/exclusion criteria differ between the studies.

In conclusion, we (re-)identified an easily accessible imaging marker which appears to be related to the clinical course of depression. Ventricular volume may affect other imaging parameters and should therefore be taken into account in future imaging studies, at least in studies in MDD. In addition, the current findings go beyond a strictly descriptive association. With the additional observation of the relationship of increased ventricular volumes and increased choroid plexus volumes, our findings provide a plausible hypothesis, how neuroendocrine and metabolic parameters mechanistically influence depressive symptoms. A new focus on choroid plexus function in stress-related disorders appears to be supported.

Acknowledgement

Data and/or research tools used in the preparation of this manuscript were obtained from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Data Archive (NDA). NDA is a collaborative informatics system created by the National Institutes of Health to provide a national resource to support and accelerate research in mental health.

The EMBARC study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers U01MH092221 (Trivedi, M.H.) and U01MH092250 (McGrath, P.J., Parsey, R.V., Weissman, M.M.). This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or of the Submitters submitting original data to NDA.

Some of the data have been published in abstract form68.

Conflict of interest:

HM: full time employee at Reviva Pharmaceuticals. He also is the owner of Murck-Neuroscience LLC, which develops a patent in the area of major depression.

MF: lifetime disclosures: Research Support: Abbott Laboratories; Acadia Pharmaceuticals; Alkermes, Inc.; American Cyanamid; Aspect Medical Systems; AstraZeneca; Avanir Pharmaceuticals; AXSOME Therapeutics; BioClinica, Inc; Biohaven; BioResearch; BrainCells Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb; CeNeRx BioPharma; Centrexion Therapeutics Corporation; Cephalon; Cerecor; Clarus Funds; Clexio Biosciences; Clintara, LLC; Covance; Covidien; Eli Lilly and Company;EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Euthymics Bioscience, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; FORUM Pharmaceuticals; Ganeden Biotech, Inc.; Gentelon, LLC; GlaxoSmithKline; Harvard Clinical Research Institute; Hoffman-LaRoche; Icon Clinical Research; Indivior; i3 Innovus/Ingenix; Janssen R&D, LLC; Jed Foundation; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development; Lichtwer Pharma GmbH; Lorex Pharmaceuticals; Lundbeck Inc.; Marinus Pharmaceuticals; MedAvante; Methylation Sciences Inc; National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression (NARSAD); National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM); National Coordinating Center for Integrated Medicine (NiiCM); National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA); National Institutes of Health; National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); Neuralstem, Inc.; NeuroRx; Novartis AG; Novaremed; Organon Pharmaceuticals; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development, Inc.; PamLab, LLC.; Pfizer Inc.; Pharmacia-Upjohn; Pharmaceutical Research Associates., Inc.; Pharmavite® LLC; PharmoRx Therapeutics; Photothera; Praxis Precision Medicines; Premiere Research International; Protagenic Therapeutics, Inc.; Reckitt Benckiser; Relmada Therapeutics Inc.; Roche Pharmaceuticals; RCT Logic, LLC (formerly Clinical Trials Solutions, LLC); Sanofi-Aventis US LLC; Shenox Pharmaceuticals, LLC; Shire; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI); Synthelabo; Taisho Pharmaceuticals; Takeda Pharmaceuticals; Tal Medical; VistaGen; WinSanTor, Inc.; Wyeth- Ayerst Laboratories; Advisory Board/Consultant: Abbott Laboratories; Acadia; Aditum Bio Management Company, LLC; Affectis Pharmaceuticals AG; Alfasigma USA, Inc.; Alkermes, Inc.; Altimate Health Corporation; Amarin Pharma Inc.; Amorsa Therapeutics, Inc.; Ancora Bio, Inc.; Angelini S.p.A; Aptinyx Inc.; Arbor Pharmaceuticals, LLC; Aspect Medical Systems; Astella Pharma Global Development, Inc.; AstraZeneca; Auspex Pharmaceuticals; Avanir Pharmaceuticals; AXSOME Therapeutics; Bayer AG; Best Practice Project Management, Inc.; Biogen; BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; BioXcel Therapeutics; Biovail Corporation; Boehringer Ingelheim; Boston Pharmaceuticals; BrainCells Inc; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Cambridge Science Corporation; CeNeRx BioPharma; Cephalon, Inc.; Cerecor; Clexio Biosciences; Click Therapeutics, Inc; CNS Response, Inc.; Compellis Pharmaceuticals; Cybin Corporation; Cypress Pharmaceutical, Inc.; DiagnoSearch Life Sciences (P) Ltd.; Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co. Inc.; Dr. Katz, Inc.; Dov Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eisai Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; ElMindA; EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Enzymotec LTD; ePharmaSolutions; EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Esthismos Research, Inc.; Euthymics Bioscience, Inc.; Evecxia Therapeutics, Inc.; ExpertConnect, LLC; FAAH Research Inc.; Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Forum Pharmaceuticals; Gate Neurosciences, Inc.; GenetikaPlus Ltd.; GenOmind, LLC; GlaxoSmithKline; Grunenthal GmbH; Happify; H. Lundbeck A/S; Indivior; i3 Innovus/Ingenis; Intracellular; Janssen Pharmaceutica; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; JDS Therapeutics, LLC; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC; Knoll Pharmaceuticals Corp.; Labopharm Inc.; Lorex Pharmaceuticals; Lundbeck Inc.; Marinus Pharmaceuticals; MedAvante, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Mind Medicine Inc.; MSI Methylation Sciences, Inc.; Naurex, Inc.; Navitor Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Nestle Health Sciences; Neuralstem, Inc.; Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc.; Neuronetics, Inc.; NextWave Pharmaceuticals; Niraxx Light Therapeutics, Inc; Northwestern University; Novartis AG; Nutrition 21; Opiant Pharmecuticals; Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc.; Organon Pharmaceuticals; Osmotica; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals; Ovid Therapeutics, Inc.; Pamlab, LLC.; Perception Neuroscience; Pfizer Inc.; PharmaStar; PharmaTher Inc.; Pharmavite® LLC.; PharmoRx Therapeutics; Polaris Partners; Praxis Precision Medicines; Precision Human Biolaboratory; Prexa Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Protagenic Therapeutics, Inc; PPD; PThera, LLC; Purdue Pharma; Puretech Ventures; Pure Tech LYT, Inc.; PsychoGenics; Psylin Neurosciences, Inc.; RCT Logic, LLC (formerly Clinical Trials Solutions, LLC); Relmada Therapeutics, Inc.; Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Ridge Diagnostics, Inc.; Roche; Sanofi-Aventis US LLC.; Sensorium Therapeutics; Sentier Therapeutics; Sepracor Inc.; Servier Laboratories; Schering-Plough Corporation; Shenox Pharmaceuticals, LLC; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Sonde Health; Sunovion Pharmaceuticals; Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Synthelabo; Taisho Pharmaceuticals; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited; Tal Medical, Inc.; Tetragenex; Teva Pharmaceuticals; TransForm Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; University of Michigan, Department of Psychiatry; Usona Institute, Inc.; Vanda Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Versant Venture Management, LLC; VistaGen; Xenon Pharmaceuticals Inc.; Speaking/Publishing: Adamed, Co; Advanced Meeting Partners; American Psychiatric Association; American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology; AstraZeneca; Belvoir Media Group; Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Cephalon, Inc.; CME Institute/Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Global Medical Education, Inc.; Imedex, LLC; MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia; MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed Elsevier; Novartis AG; Organon Pharmaceuticals; Pfizer Inc.; PharmaStar; United BioSource, Corp.; Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories; Equity Holdings: Compellis; Neuromity; Psy Therapeutics; Sensorium Therapeutics; Royalty/patent, other income: Patents for Sequential Parallel Comparison Design (SPCD), licensed by MGH to Pharmaceutical Product Development, LLC (PPD) (US_7840419, US_7647235, US_7983936, US_8145504, US_8145505); and patent application for a combination of Ketamine plus Scopolamine in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), licensed by MGH to Biohaven. Patents for pharmacogenomics of Depression Treatment with Folate (US_9546401, US_9540691). Copyright: for the MGH Cognitive & Physical Functioning Questionnaire (CPFQ), Sexual Functioning Inventory (SFI), Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ), Discontinuation-Emergent Signs & Symptoms (DESS), Symptoms of Depression Questionnaire (SDQ), and SAFER; Belvoir; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Wolkers Kluwer; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

CCF: nothing to disclose

CC: personal fees from Janssen, Perception, and Takeda; and grants from Clexio, Livanova, AFSP, and the National Institute of Mental Health.

MHT: research support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Cyberonics Inc., National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression, NIMH, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and Johnson & Johnson; consulting and speaker fees from Abbott Laboratories Inc., Akzo (Organon Pharmaceuticals Inc.), Allergan Sales LLC, Alkermes, Astra Zeneca, Axon Advisors, Brintellix, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon Inc., Cerecor, Eli Lilly & Company, Evotec, Fabre Kramer Pharmaceuticals Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Health Research Associates, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, MedAvante Medscape, Medtronic, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Development America Inc., MSI Methylation Sciences Inc., Nestle Health Science-PamLab Inc., Naurex, Neuronetics, One Carbon Therapeutics Ltd, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pamlab, Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals Inc., Pfizer Inc., PgxHealth, Phoenix Marketing Solutions, Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Ridge Diagnostics, Roche Products Ltd, Sepracor, SHIRE Development, Sierra, SK Life and Science, Sunovion, Takeda, Tal Medical/Puretech Venture, Targacept, Transcept, VantagePoint, Vivus, and Wyeth- Ayerst Laboratories.

Footnotes

Tables 1 to 3 are available in the Supplementary Files section

Registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov: Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response for Clinical Care for Depression (EMBARC); https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01407094; NCT01407094.

Supplementary Files

References:

- 1.Lamers F, Vogelzangs N, Merikangas KR, de Jonge P, Beekman AT, Penninx BW. Evidence for a differential role of HPA-axis function, inflammation and metabolic syndrome in melancholic versus atypical depression. Mol Psychiatry 2013; 18(6): 692–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008; 9(1): 46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 65(9): 732–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raison CL, Rutherford RE, Woolwine BJ, Shuo C, Schettler P, Drake DF et al. A randomized controlled trial of the tumor necrosis factor antagonist infliximab for treatment-resistant depression: the role of baseline inflammatory biomarkers. JAMA psychiatry 2013; 70(1): 31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richter N, Juckel G, Assion HJ. Metabolic syndrome: a follow-up study of acute depressive inpatients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2010; 260(1): 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamers F, de Jonge P, Nolen WA, Smit JH, Zitman FG, Beekman AT et al. Identifying depressive subtypes in a large cohort study: results from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Clin Psychiatry 2010; 71(12): 1582–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juruena MF, Cleare AJ, Papadopoulos AS, Poon L, Lightman S, Pariante CM. The prednisolone suppression test in depression: dose-response and changes with antidepressant treatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010; 35(10): 1486–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murck H, Schussler P, Steiger A. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: the forgotten stress hormone system: relationship to depression and sleep. Pharmacopsychiatry 2012; 45(3): 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buttner M, Jezova D, Greene B, Konrad C, Kircher T, Murck H. Target-based biomarker selection - Mineralocorticoid receptor-related biomarkers and treatment outcome in major depression. J Psychiatr Res 2015; 66–67: 24–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kemp AH, Quintana DS, Gray MA, Felmingham KL, Brown K, Gatt JM. Impact of depression and antidepressant treatment on heart rate variability: a review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67(11): 1067–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Licht CM, de Geus EJ, Zitman FG, Hoogendijk WJ, van Dyck R, Penninx BW. Association between major depressive disorder and heart rate variability in the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65(12): 1358–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelmann J, Murck H, Wagner S, Zillich L, Streit F, Herzog DP et al. Routinely accessible parameters of mineralocorticoid receptor function, depression subtypes and response prediction: a post-hoc analysis from the early medication change trial in major depressive disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry 2022: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drevets WC, Ongur D, Price JL. Neuroimaging abnormalities in the subgenual prefrontal cortex: implications for the pathophysiology of familial mood disorders. Mol Psychiatry 1998; 3(3): 220–226, 190–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samann PG, Hohn D, Chechko N, Kloiber S, Lucae S, Ising M et al. Prediction of antidepressant treatment response from gray matter volume across diagnostic categories. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2013; 23(11): 1503–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlegel S, Maier W, Philipp M, Aldenhoff JB, Heuser I, Kretzschmar K et al. Computed tomography in depression: association between ventricular size and psychopathology. Psychiatry Res 1989; 29(2): 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kempton MJ, Salvador Z, Munafo MR, Geddes JR, Simmons A, Frangou S et al. Structural neuroimaging studies in major depressive disorder. Meta-analysis and comparison with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68(7): 675–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Via E, Cardoner N, Pujol J, Martinez-Zalacain I, Hernandez-Ribas R, Urretavizacaya M et al. Cerebrospinal fluid space alterations in melancholic depression. PLoS One 2012; 7(6): e38299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardoner N, Pujol J, Vallejo J, Urretavizcaya M, Deus J, Lopez-Sala A et al. Enlargement of brain cerebrospinal fluid spaces as a predictor of poor clinical outcome in melancholia. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64(6): 691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murck H, Luerweg B, Hahn J, Braunisch M, Jezova D, Zavorotnyy M et al. Ventricular volume, white matter alterations and outcome of major depression and their relationship to endocrine parameters - A pilot study. World J Biol Psychiatry 2020: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernardi G, Cecchetti L, Siclari F, Buchmann A, Yu X, Handjaras G et al. Sleep reverts changes in human gray and white matter caused by wake-dependent training. Neuroimage 2016; 129: 367–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henckens MJ, van der Marel K, van der Toorn A, Pillai AG, Fernandez G, Dijkhuizen RM et al. Stress-induced alterations in large-scale functional networks of the rodent brain. Neuroimage 2015; 105: 312–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou G, Hotta J, Lehtinen MK, Forss N, Hari R. Enlargement of choroid plexus in complex regional pain syndrome. Scientific reports 2015; 5: 14329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavagnino L, Amianto F, Mwangi B, D’Agata F, Spalatro A, Zunta-Soares GB et al. Identifying neuroanatomical signatures of anorexia nervosa: a multivariate machine learning approach. Psychol Med 2015; 45(13): 2805–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleischer V, Gonzalez-Escamilla G, Ciolac D, Albrecht P, Kury P, Gruchot J et al. Translational value of choroid plexus imaging for tracking neuroinflammation in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021; 118(36). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Althubaity N, Schubert J, Martins D, Yousaf T, Nettis MA, Mondelli V et al. Choroid plexus enlargement is associated with neuroinflammation and reduction of blood brain barrier permeability in depression. Neuroimage Clin 2022; 33: 102926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Senay O, Seethaler M, Makris N, Yeterian E, Rushmore J, Cho KIK et al. A preliminary choroid plexus volumetric study in individuals with psychosis. Hum Brain Mapp 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sathyanesan M, Girgenti MJ, Banasr M, Stone K, Bruce C, Guilchicek E et al. A molecular characterization of the choroid plexus and stress-induced gene regulation. Transl Psychiatry 2012; 2: e139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong ML, Licinio J. Localization of interleukin 1 type I receptor mRNA in rat brain. Neuroimmunomodulation 1994; 1(2): 110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong ML, Licinio J, Pasternak KI, Gold PW. Localization of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptor mRNA in adult rat brain by in situ hybridization histochemistry. Endocrinology 1994; 135(5): 2275–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murck H, Lehr L, Jezova D. A viewpoint on aldosterone and BMI related brain morphology in relation to treatment outcome in patients with major depression. J Neuroendocrinol 2022: e13219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dantzer R. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior: mechanisms and implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2001; 933: 222–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skipor J, Thiery JC. The choroid plexus--cerebrospinal fluid system: undervaluated pathway of neuroendocrine signaling into the brain. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2008; 68(3): 414–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper CM, Chin Fatt CR, Jha M, Fonzo GA, Grannemann BD, Carmody T et al. Cerebral Blood Perfusion Predicts Response to Sertraline versus Placebo for Major Depressive Disorder in the EMBARC Trial. EClinicalMedicine 2019; 10: 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trivedi MH, McGrath PJ, Fava M, Parsey RV, Kurian BT, Phillips ML et al. Establishing moderators and biosignatures of antidepressant response in clinical care (EMBARC): Rationale and design. J Psychiatr Res 2016; 78: 11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pillai RLI, Huang C, LaBella A, Zhang M, Yang J, Trivedi M et al. Examining raphe-amygdala structural connectivity as a biological predictor of SSRI response. J Affect Disord 2019; 256: 8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb CA, Trivedi MH, Cohen ZD, Dillon DG, Fournier JC, Goer F et al. Personalized prediction of antidepressant v. placebo response: evidence from the EMBARC study. Psychol Med 2019; 49(7): 1118–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheldon CA, Kwon YJ, Liu GT, McCormack SE. An integrated mechanism of pediatric pseudotumor cerebri syndrome: evidence of bioenergetic and hormonal regulation of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. Pediatr Res 2015; 77(2): 282–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benedetti F, Yeh PH, Bellani M, Radaelli D, Nicoletti MA, Poletti S et al. Disruption of white matter integrity in bipolar depression as a possible structural marker of illness. Biol Psychiatry 2011; 69(4): 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen G, Guo Y, Zhu H, Kuang W, Bi F, Ai H et al. Intrinsic disruption of white matter microarchitecture in first-episode, drug-naive major depressive disorder: A voxel-based meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2017; 76: 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Diego-Adelino J, Pires P, Gomez-Anson B, Serra-Blasco M, Vives-Gilabert Y, Puigdemont D et al. Microstructural white-matter abnormalities associated with treatment resistance, severity and duration of illness in major depression. Psychol Med 2014; 44(6): 1171–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo WB, Liu F, Xue ZM, Gao K, Wu RR, Ma CQ et al. Altered white matter integrity in young adults with first-episode, treatment-naive, and treatment-responsive depression. Neurosci Lett 2012; 522(2): 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Repple J, Meinert S, Grotegerd D, Kugel H, Redlich R, Dohm K et al. A voxel-based diffusion tensor imaging study in unipolar and bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord 2017; 19(1): 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wise T, Radua J, Nortje G, Cleare AJ, Young AH, Arnone D. Voxel-Based Meta-Analytical Evidence of Structural Disconnectivity in Major Depression and Bipolar Disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2016; 79(4): 293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nilsson C, Lindvall-Axelsson M, Owman C. Neuroendocrine regulatory mechanisms in the choroid plexus-cerebrospinal fluid system. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 1992; 17(2): 109–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rocha R, Rudolph AE, Frierdich GE, Nachowiak DA, Kekec BK, Blomme EA et al. Aldosterone induces a vascular inflammatory phenotype in the rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2002; 283(5): H1802–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hlavacova N, Wes PD, Ondrejcakova M, Flynn ME, Poundstone PK, Babic S et al. Subchronic treatment with aldosterone induces depression-like behaviours and gene expression changes relevant to major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2012; 15(2): 247–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bay-Richter C, Hallberg L, Ventorp F, Janelidze S, Brundin L. Aldosterone synergizes with peripheral inflammation to induce brain IL-1beta expression and depressive-like effects. Cytokine 2012; 60(3): 749–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller GE, Freedland KE, Carney RM, Stetler CA, Banks WA. Pathways linking depression, adiposity, and inflammatory markers in healthy young adults. Brain Behav Immun 2003; 17(4): 276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cooper JN, Tepper P, Barinas-Mitchell E, Woodard GA, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Serum aldosterone is associated with inflammation and aortic stiffness in normotensive overweight and obese young adults. Clin Exp Hypertens 2012; 34(1): 63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Kloet AD, Pioquinto DJ, Nguyen D, Wang L, Smith JA, Hiller H et al. Obesity induces neuroinflammation mediated by altered expression of the renin-angiotensin system in mouse forebrain nuclei. Physiol Behav 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pires PW, McClain JL, Hayoz SF, Dorrance AM. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism prevents obesity-induced cerebral artery remodeling and reduces white matter injury in rats. Microcirculation 2018; 25(5): e12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Clark DB, Casey BJ, Giedd JN, Boring AM et al. A.E. Bennett Research Award. Developmental traumatology. Part II: Brain development. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45(10): 1271–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Bellis MD, Zisk A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2014; 23(2): 185–222, vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry JID - 0213264 2001; 49(12): 1023–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nelson J, Klumparendt A, Doebler P, Ehring T. Childhood maltreatment and characteristics of adult depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2017; 210(2): 96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Medeiros GC, Prueitt WL, Rush AJ, Minhajuddin A, Czysz AH, Patel SS et al. Impact of childhood maltreatment on outcomes of antidepressant medication in chronic and/or recurrent depression. J Affect Disord 2021; 291: 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalyan-Masih P, Vega-Torres JD, Miles C, Haddad E, Rainsbury S, Baghchechi M et al. Western High-Fat Diet Consumption during Adolescence Increases Susceptibility to Traumatic Stress while Selectively Disrupting Hippocampal and Ventricular Volumes. eNeuro 2016; 3(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Israelsson H, Carlberg B, Wikkelso C, Laurell K, Kahlon B, Leijon G et al. Vascular risk factors in INPH: A prospective case-control study (the INPH-CRasH study). Neurology 2017; 88(6): 577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lamers F, Bot M, Jansen R, Chan MK, Cooper JD, Bahn S et al. Serum proteomic profiles of depressive subtypes. Transl Psychiatry 2016; 6(7): e851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lasserre AM, Glaus J, Vandeleur CL, Marques-Vidal P, Vaucher J, Bastardot F et al. Depression with atypical features and increase in obesity, body mass index, waist circumference, and fat mass: a prospective, population-based study. JAMA psychiatry 2014; 71(8): 880–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Zisook S, Cook I et al. Do atypical features affect outcome in depressed outpatients treated with citalopram? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2010; 13(1): 15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Novick JS, Stewart JW, Wisniewski SR, Cook IA, Manev R, Nierenberg AA et al. Clinical and demographic features of atypical depression in outpatients with major depressive disorder: preliminary findings from STAR*D. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(8): 1002–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Herzog DP, Wagner S, Engelmann J, Treccani G, Dreimuller N, Muller MB et al. Early onset of depression and treatment outcome in patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2021; 139: 150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sydnor VJ, Lyall AE, Cetin-Karayumak S, Cheung JC, Felicione JM, Akeju O et al. Studying pre-treatment and ketamine-induced changes in white matter microstructure in the context of ketamine’s antidepressant effects. Transl Psychiatry 2020; 10(1): 432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vasavada MM, Leaver AM, Espinoza RT, Joshi SH, Njau SN, Woods RP et al. Structural connectivity and response to ketamine therapy in major depression: A preliminary study. J Affect Disord 2016; 190: 836–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo WB, Liu F, Chen JD, Xu XJ, Wu RR, Ma CQ et al. Altered white matter integrity of forebrain in treatment-resistant depression: a diffusion tensor imaging study with tract-based spatial statistics. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2012; 38(2): 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bishop JH, Shpaner M, Kubicki A, Clements S, Watts R, Naylor MR. Structural network differences in chronic muskuloskeletal pain: Beyond fractional anisotropy. Neuroimage 2018; 182: 441–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murck H, Fava M, Cusin C, Chin Fatt C, trivedi M. Brain Ventricle Morphology as Predictor of Treatment-Response-Findings From the EMBARC-Study. Biological Psychiatry 2021; 89(9, SUPPLEMENT): S367–S368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]