Abstract

While the Food and Drug Administration’s black-box warnings caution against concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine (OPI–BZD) use, there is little guidance on how to deprescribe these medications. This scoping review analyzes the available opioid and/or benzodiazepine deprescribing strategies from the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, and Cochrane Library databases (01/1995–08/2020) and the gray literature. We identified 39 original research studies (opioids: n = 5, benzodiazepines: n = 31, concurrent use: n = 3) and 26 guidelines (opioids: n = 16, benzodiazepines: n = 11, concurrent use: n = 0). Among the three studies deprescribing concurrent use (success rates of 21–100%), two evaluated a 3-week rehabilitation program, and one assessed a 24-week primary care intervention for veterans. Initial opioid dose deprescribing rates ranged from (1) 10–20%/weekday followed by 2.5–10%/weekday over three weeks to (2) 10–25%/1–4 weeks. Initial benzodiazepine dose deprescribing rates ranged from (1) patient-specific reductions over three weeks to (2) 50% dose reduction for 2–4 weeks, followed by 2–8 weeks of dose maintenance and then a 25% reduction biweekly. Among the 26 guidelines identified, 22 highlighted the risks of co-prescribing OPI–BZD, and 4 provided conflicting recommendations on the OPI–BZD deprescribing sequence. Thirty-five states’ websites provided resources for opioid deprescription and three states’ websites had benzodiazepine deprescribing recommendations. Further studies are needed to better guide OPI–BZD deprescription.

Keywords: opioid, benzodiazepine, concurrent use, deprescribing, tapering

1. Introduction

Opioid overdose remains a pervasive public health problem in the United States (US), with over 80,000 estimated opioid overdose deaths in 2021 [1]. Approximately 18% of opioid overdose deaths involve prescription opioids [2], and 31% to 61% involve benzodiazepines [3,4,5]. Additionally, about 38% of benzodiazepine overdose deaths involve prescription opioids [6]. Prior studies found that concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use was associated with a 1.5- to 10-fold elevated overdose risk compared to opioid use alone [4,7,8,9,10,11].

Even with clinical guidelines and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) black-box warnings cautioning against concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use [12,13,14], many individuals use them concurrently (e.g., 25% of long-term opioid users concomitantly use benzodiazepines) [15]. Clinicians face challenges in avoiding such co-prescription in certain patients (e.g., chronic pain with anxiety or sleep disorders), despite known synergistic respiratory-depression effects and increased adverse health outcome risks (e.g., falls) [12,13,14]. Furthermore, opioid-related policies and restrictions may result in unintended consequences (e.g., abrupt discontinuation). In 2019, the FDA issued a drug safety communication calling for gradual, individualized opioid tapering due to potential harms (e.g., overdose and mental health crisis) from abrupt opioid dose reduction that may lead some patients to seek illicit sources [16]. In 2020, the FDA also updated the boxed warning on all benzodiazepines, cautioning against abrupt discontinuation due to withdrawal reactions such as chest pain, rapid heart rate, shaking, and agoraphobia [17].

Deprescribing is the systematic reduction in dose or discontinuation of a medication [18,19]. Systematic reviews and guidelines have widely varying recommendations on tapering, deprescribing, or discontinuing opioids and benzodiazepines separately. Little is known about strategies and evidence available for deprescribing concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use. We conducted a scoping review of the published, peer-reviewed literature and the publicly available, web-based gray literature (e.g., governmental guidelines, clinical protocols) to collate the available evidence and strategies on deprescribing opioids and/or benzodiazepines to better guide clinical care and target interventions toward concurrent users.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategies

This scoping review complied with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guidelines [20]. The study protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework (10.17605/OSF.IO/ZUMND).

A health sciences librarian (L.E.A) performed the original search, in August 2020, of the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus, and Cochrane Library databases for studies published from January 1995 to August 2020. The search strategy combined database-specific, controlled vocabulary and used truncation and phrase searching in titles and abstracts for articles on deprescribing opioids and benzodiazepines in concurrent and nonconcurrent use. We restricted the search results to the English language. The PubMed search strategy is available in Supplementary Table S1. Additionally, we used relevant keywords (e.g., opioid deprescribing or tapering) to search publicly available, web-based gray literature including deprescribing guidelines or protocols published from (1) the Canadian Deprescribing Network [21] and the US Deprescribing Research Network [22], (2) the US federal government agencies (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and the state health departments (Table S2), and (3) leading health systems and health insurance companies based on net patient revenue or number of members identified by Statista [23] and Definitive Healthcare [24]. Finally, we manually screened reference lists from eligible identified sources.

2.2. Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Data Synthesis

We restricted our search to clinical trials or observational studies reporting details of deprescribing strategies. Such strategies included deprescribing speed and dose reduction specifications in ambulatory adults aged ≥ 18 years using opioids or benzodiazepines. We excluded studies focusing on the deprescription of buprenorphine or methadone use for opioid use disorder.

After a comprehensive literature search and removal of duplicates, at least two investigators (D.L.W., A.B., C.C., N.D., P.-L.H., and A.J.) independently screened each source and extracted data. We screened the articles’ titles, abstracts, and full text using Covidence (Melbourne, Australia) and extracted information of interest using a standardized Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. For original studies, we extracted the author, publication year, country, deprescribing focus (opioid, benzodiazepine, or both), reasons for deprescribing, deprescribing protocols, the successful proportion deprescribed, discontinuation duration, and other deprescribing interventions used in the study (e.g., medication and cognitive behavioral therapy). Given that several published systematic and scoping reviews summarize deprescribing strategies for opioids or benzodiazepines alone [25,26,27,28,29,30], we focused on reporting the studies that deprescribed concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use. For the guidelines/protocols, we extracted deprescribing details, including criteria for considering deprescription, alternative medication therapies, nondrug approaches, and management methods of withdrawal symptoms. We also summarized how states and leading insurance companies referenced or adapted the existing national guidelines. When there were multiple versions of a guideline/protocol available from one entity, we included the information from the most recent version. Disagreements in data extracted between reviewers were resolved by a third investigator (D.L.W. or W.-H.L.-C.).

3. Results

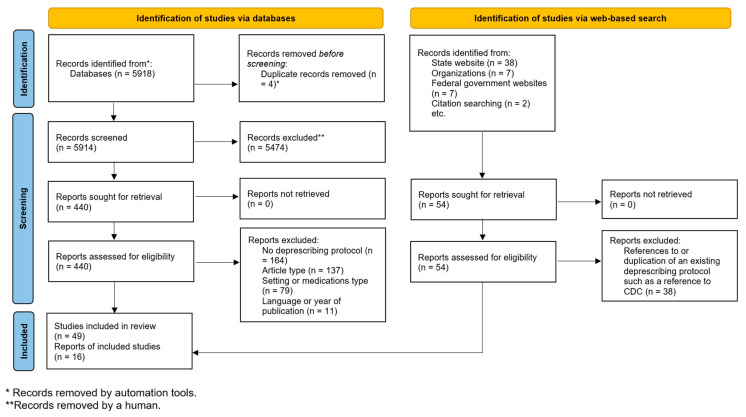

As shown in Figure 1, our peer-reviewed literature search identified 5914 articles after removing duplicates. Title and abstract screening excluded 5474 studies. We reviewed the full text of 440 articles and included 39 eligible original research articles and 10 practice guidelines. Our gray literature search identified 16 unique governmental or health systems’ deprescribing guidelines.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included studies.

3.1. Original Research Studies

Of the 39 studies, 14 (36%) were conducted in the US and 10 (26%) in Canada (Table S3). The publication years ranged from 1995 to 2019. Overall, 5 studies focused on opioid deprescription only, and 31 focused on benzodiazepine deprescription only. Below, we describe in detail three studies (Cunningham et al., 2016 [31]; Gilliam et al., 2018 [32]; Zaman et al., 2018 [33]) that used strategies to deprescribe both medications when used concomitantly (Table S4).

Cunningham et al. (2016) [31] evaluated an intensive 3-week outpatient interdisciplinary rehabilitation program for discontinuing opioids in individuals with a primary diagnosis of fibromyalgia and chronic noncancer pain in a pain rehabilitation center in the US. Individuals in the opioid sample (n = 55) were on average 49 years old and mostly of Caucasian race (91.0%) and female (84.0%). Deprescribing recommendations varied depending on the patients’ morphine equivalent daily dose (MME/day). Patients with ≤100 MME/day were deprescribed off opioids over a mean of 10 days; those taking 100–200 MME/day were deprescribed over a mean of 14 days; and those taking >200 MME/day were deprescribed over a mean of 18 days. From day 1 to day 7 or 11 of the 3-week deprescribing period, participants generally reduced their total opioid dose by 10–20% each weekday (Monday–Friday). They reduced the dose by 2.5–10% each weekday during the remaining taper period. Of the 55 taking opioids, 51 (92.7%) discontinued the opioids during the 3-week program. With the goal of discontinuation of opioid and adjuvant medications for chronic nonmalignant pain, benzodiazepines were deprescribed by developing a deprescribing schedule individualized to each patient. If, at program discharge, the patient had started to reduce their benzodiazepine dose, a generic recommendation was used in the summary note that (1) indicated the initial dose and the current dose and (2) recommended that the primary care provider (PCP) continue the current dose for the next 2–4 weeks and then continue to taper the patient by approximately 25% every 2–4 weeks until completed. The proportion of persons concurrently taking benzodiazepines and opioids and the outcomes of benzodiazepine deprescription were not measured.

Gilliam et al. (2018) [32] evaluated a 3-week interdisciplinary rehabilitation program intervention in noncancer pain patients in the same pain rehabilitation center where the Cunningham et al. (2016) study was conducted [31]. Individuals in the Gilliam et al. (2018) [32] sample who completed the program (285/344 [82.8%]) were on average 49 years old and mostly of Caucasian race (88.7%) and female (62.8%). Among 142 patients taking opioids at baseline who completed the program, 58 (40.8%) were also taking benzodiazepines at baseline. The study also included 43 individuals, who were taking benzodiazepines but not opioids (n = 143) at baseline, who completed the program. The opioid deprescribing schedules reduced doses by 10–20% each weekday from day 1 to day 7 or 11 of the 15-day taper and by 2.5–10% each weekday during the remainder. The benzodiazepine deprescribing protocol was the same as that in the Cunningham (2016) study. The article mentioned that benzodiazepine deprescription could be extended beyond the 3-week program because the risk for complications is greater for benzodiazepine tapers than for opioid tapers. Of the 165 patients taking opioids, 142 (86.1%) completed the deprescribing protocol and discontinued the opioids. Among 58 patients taking opioids and benzodiazepines concurrently at baseline, all (100%) discontinued opioids, and 20 (34.5%) discontinued both medications. Among 43 patients taking benzodiazepines but not taking opioids at baseline, 23 (53.4%) discontinued benzodiazepines.

Zaman et al. (2018) [33] evaluated an electronic intervention in a US Veteran cohort (61% White race and 92% male) receiving primary care in one US Veterans’ administration system and co-prescribed opioids (>90 days in the prior 120 days) and benzodiazepines (defined as having ≥1 overlapping day using both medication classes). Individuals in the sample (n = 145) were on average 62 years old and had a high incidence of mood (61%) and post-traumatic stress (56%) disorders. The intervention consisted of a review note in the patient’s electronic medical record (EMR), an email to the prescriber, and a clinician’s guide on deprescribing opioids and benzodiazepines. The EMR review note and email recommendations for deprescription asked clinicians to “consider benzodiazepine and/or opioid taper (to <100 MME/day or off entirely if still prescribed benzodiazepine)”. The opioid deprescribing schedule in the clinician’s guide recommended reducing the dose by 10–25% every 1 to 4 weeks for most patients and to rapidly reduce the dose every 1 to 7 days in medically dangerous situations. The benzodiazepine deprescribing schedule in the clinician’s guide recommended reducing the dose by 50% for 2 to 4 weeks, then maintaining the dose for 1 to 2 months, and then reducing it by 25% every 2 weeks. Conversion to a long-acting benzodiazepine was recommended as an alternative for patients who were not concurrently prescribed high-dose opioids. The proportion of individuals with ≥100 MME/day at baseline (39/145 [26.8%]) decreased by 30% at six months (26/139 [18.7%]). The mean MME/day decreased from 84.6 MME/day at baseline to 76.2 MME/day at 3-month follow up and to 65.6 MME/day at 6-month follow up, resulting in a 22% decrease over six months. The mean diazepam milligram equivalent daily dose (DME/day) decreased from 16.10 DME/day at baseline to 13.8 DME/day at 3-month follow up and to 13.4 DME/day at 6-month follow up, resulting in a 17% decrease over six months. The number of individuals with co-prescribed opioids and benzodiazepines decreased from baseline by 21% at 3-month follow up. At the 6-month measurement (n = 139), 46 (33.1%) patients were no longer co-prescribed opioids and benzodiazepines (14 [10.1%] discontinued opioids, 23 [16.5%] discontinued benzodiazepines, and 9 [6.5%] discontinued both).

3.2. Guidelines

Among the 26 unique guidelines identified, 16 provided deprescribing schedules for opioids only, and 11 provided deprescribing schedules for benzodiazepines only, with the Oregon Pain Guidance [34] guideline mentioning both medication classes (Table 1). All 26 guidelines included criteria for when to consider deprescription and emphasized the importance of withdrawal symptom management, shared decision-making with patients, and nonpharmacological support. In all, 14 of the 16 (88%) opioid deprescribing guidelines and 9 of 11 benzodiazepine guidelines mentioned the risk of concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use, but none of the 26 had specific deprescribing schedules for concurrent users. Two guidelines recommended that concomitant users deprescribe opioids first, followed by gradual benzodiazepine deprescription [35,36], while the Oregon Pain Guidance [34] guideline recommended the opposite and the Minnesota Department of Human Services website suggested that benzodiazepines may be deprescribed first for patients receiving concurrent high daily MME doses and intermittent benzodiazepines [37]. The Minnesota Department of Human Services website did not define high daily MME in concurrent benzodiazepine use.

Table 1.

Characteristics of unique guidelines and protocols for deprescribing opioids or benzodiazepines.

| Source | Target Population | Deprescribing Rate | Organizations Using the Guideline | Elements in the Guidelines/Protocols (Y = Yes; N = No): (a) Risk of Concurrent Use; (b) Criteria for Considering Tapering Opioid/Benzodiazepine Therapy; (c) Shared Decision-Making with Pts; (d) Withdrawal Management; (e) Nonpharmacological Approaches; (f) Alternative Medication Therapies. |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioids (N = 16) | (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (e) | (f) | |||

| CDC, 2022 [38] | Pts with CNCP | 1. OPI use ≥1 year: reduce dose 10% or less per month. 2. OPI use for shorter durations: reduce initial dose 10% or less per week until ~30%, followed by 10% per week. |

* | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| VA/DoD, 2022 [39] | Pts with CNCP | Gradual and individualized taper: reduce dose 5–20% every 4 weeks or longer. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Minnesota Department of Human Service, 2021 [37] | Pts with CNCP | Individualized taper based on patient tolerance: 1. Slower: reduce dose 5–10% per month to start but may need to reduce rate to less than 5% per month over 2–3 months as tolerated. 2. Faster: reduce initial dose 10% per week or longer; not preferred but used when risk of continuing therapy outweighs risk of rapid taper or when part of treatment program for short time period. 3. May taper BZD first for pts with high daily MME and intermittent BZD. |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Oregon Health Authority, 2020 [40] | Pts on OPIs | Individualized: generally, reduce dose 5–10% per month. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Arizona Department of Health Services, 2018 [41] | Pts on LTOT | Individualized taper based on risk assessment: 1. Slowest (over years): reduce dose 2–10% every 4–8 weeks with pauses in taper as needed. 2. Slow (over months to years): reduce dose 5–20% every 4 weeks with pauses in taper as needed. 3. Faster (over weeks): reduce dose 10–20% every week. 4. Rapid (over days): reduce first dose 20–50%, then 10–20% every day. |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Cigna, 2019 [42] | Pts on LTOT | Individualized taper based on pt health history, preferences, and risk factors, e.g., reduce dose 5–10% per month. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| FDA, 2019 [16] | Pts physically dependent on OPIs | Gradual and individualized taper: 1. No more than 10–25% reduction every 2–4 weeks. 2. More rapid taper: pts on opioids for shorter time periods. |

UnitedHealthcare [43] | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| HHS, 2019 [44] | Pts on LTOT for chronic pain | 1. Common: reduce dose 5–20% every 4 weeks. 2. Gradual: reduce dose 10% per month or slower. 3. Rapid: reduce dose 10% per week up to 30% of the original dose and then 10% per week. |

Sunshine Health [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Mendoza, 2019 [46] | Pts with CNCP | 1. Rapid: reduce dose 20% per week or abrupt discontinuation. 2. Slow: reduce dose 5–20% every 2–4 weeks. |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Lumish, 2018 [47] | Pts ≥65 years with CNCP | Reduce dose 5–20% every 4 weeks. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Murphy, 2018 [48] | Pts with CNCP | Reduce dose 5–10% every 2–4 weeks. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, 2017 [35] | Pts on OPIs | 1. Long-acting OPIs: reduce dose 5–10% per week. 2. Short-acting OPIs: reduce dose 5–15% per week. 3. After reaching 1/4–1/2 of the initial dose, may slow dose reduction rate for pts cooperative with therapy. 4. Taper opioid first to reduce risk of overdose in pts on both OPI and BZD. |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| VA PBM, 2016 [49] | Pts on OPIs | 1. Slowest: reduce dose 2–10% every 4–8 weeks with pauses in taper as needed (e.g., pts taking high doses of long-acting opioids for many years). 2. Slower: reduce dose 5–20% every 4 weeks. 3. Faster: reduce dose 10–20% per week. 4. Rapid: reduce dose 20–50% of first dose, then 10–20% every day. |

United Healthcare [43] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| AMDG, 2015 [36] | Pts with CNCP | 1. Taper off opioid first and then benzodiazepine with a deprescribing rate based on safety profile. 2. Slow: reduce dose by ≤10% per week for pts with no acute safety concerns from a mental/physical health perspective. 3. Rapid: discontinue over 2–3 weeks if pts having severe adverse outcomes (e.g., overdose or SUD). 4. Immediate: discontinuation if diversion/nonmedical use. |

Sunshine Health [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Berna, 2015 [50] | Pts with CNCP | Reduce dose 10% every 5–7 days until reaching 30% of the initial dose, then reduce 10% per week. | United Healthcare [43] | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Oregon Pain Guidance, 2014 [34] | Pts with CNCP | 1. Long-acting OPIs: reduce dose 5–10% per week. 2. Short-acting OPIs: reduce dose 5–15% per week. 3. Slow down rate toward the end of taper. Once reaching 25–50% of initial dose, slow to 5% per week. 4. Taper BZD followed by OPI if both drugs involved. |

Sunshine Health [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Benzodiazepines (N = 11) | |||||||||

| Kaiser Permanente, 2022 [51] | Pts on chronic BZD therapy | Individualized taper based on indication: 1. Slow (reduce dose 10% every 2–4 weeks): function not improved or tolerance developed with long-term Rx. 2. Moderate (reduce dose 10% per week): risks greater than benefit or increased risk with comorbidities. 3. Rapid (reduce dose 25% per week): substance abuse, significant risk due to unstable clinical condition or recent overdose or misuse or diversion of medication. |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| FDA, 2020 [17] | Pts on BZDs | 1. Gradual and individualized taper. 2. When experiencing withdrawal symptoms, may pause the taper or raise BZD to previous dose. Once stable, proceed with more gradual taper. |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | |

| Payne, 2019 [52] | Pts on BZDs | 1. Reduce dose 10–12.5% every 1–2 weeks over 2–12 months. 2. Reduce dose 10–25% every 2 weeks over 4–8 weeks. |

N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | |

| Presbyterian Healthcare Services, 2019 [53] | Pts ≥18 years on BZD or Z-drug therapy | Taper duration (considering prior use duration) 1. Prior use < 3 months: over 1 week 2. Prior use 3 months–1 year: over 1 month 3. Prior use > 1 year: over 3 months Taper dosage 1. Typical 3-month duration, reduce from 100% to 50% of initial dose during the first 4 weeks, then reduce from 50% to 0% during remaining 2 months. 2. More rapid (25% per week) may be appropriate for pts having increased risk of respiratory depression or misusing/diverting Rx. |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Pottie, 2018 [54] | Pts ≥65 years on BZRAs Pts 18–64 years on BZRAs > 4 weeks |

Reduce dose 25% every 2 weeks, then 12.5% near end with duration of taper dependent upon patient tolerance, dependence, and potential for withdrawal effects. | Choosing Wisely Canada [55,56] deprescribing.org [57] CalOptima [58] |

N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Pruskowski, 2018 [59] | “Older” pts in palliative care on BZD | Reduce over 8–12 weeks total, reduce baseline dose 10–25% every 2–3 weeks based on BZD terminal half-life. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Ogbonna, 2017 [60] | Pts on BZDs daily > 1 month | Reduce initial dose 5–25%, then 5–25% every 1–4 weeks as tolerated; reduce supratherapeutic dose 25–30% as tolerated, followed by 5–10% daily, weekly, or monthly as appropriate. Complex cases may require stabilization at 50% dose reduction for several months prior to resuming taper. | CalOptima [58] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| VA PTSD, 2015 [61] | Pts with PTSD | Reduce dose 50% the first 2–4 weeks then maintain dose for 1–2 months. Further reduce dose 25% every 2 weeks. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Oregon Pain Guidance, 2014 [34] | Pts on BZDs | 1. Slow: Reduce initial dose 25–50%, then 5–10% per week with follow up; total dose reduction of long-acting drug 5–10% per week in divided doses. When 25–50% of starting dose is reached, slowly taper further to 5% or less per week. 2. Rapid: Pre-medicate for 2 weeks prior with carbamazepine 200 mg every morning and 400 mg every bedtime or valproate 500 mg twice daily. Continue these medications 4 weeks after BZD is discontinued. Discontinue the current BZD and switch to diazepam 2 mg twice daily × 2 days, followed by 2 mg daily × 2 days, then stop. For high doses, may begin with 5 mg twice daily × 2 days and then continue as described. 3. Taper BZD followed by OPI if both drugs involved. |

Sunshine Health [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Belanger, 2009 [62] | Pts with chronic insomnia | 1. Reduce dose by 25% every 1–2 weeks to smallest minimal dose. 2. Switch short-acting BZD to longer-acting BZD. Reduce initial dose 25% by 2nd week, 50% by 4th week, 100% by 10th week. |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Woodward, 2003 [63] | Pts ≥ 65 years | 1. Short-acting: cease or wean if not needed. 2. Long-acting: reduce dose 10–15% per week. 3. Both 1 and 2: combine with sleep hygiene/psychotherapy. |

Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

Abbreviations: BZD: benzodiazepine; BZRA: benzodiazepine receptor agonist; CNCP: chronic noncancer pain; LTOT: long-term opioid therapy; MME: morphine milligram equivalents; OPI: opioid; Pts: patients; Rx: prescription. * United Healthcare [43] and Sunshine Health [45] cite the 2016 version of the CDC guideline.

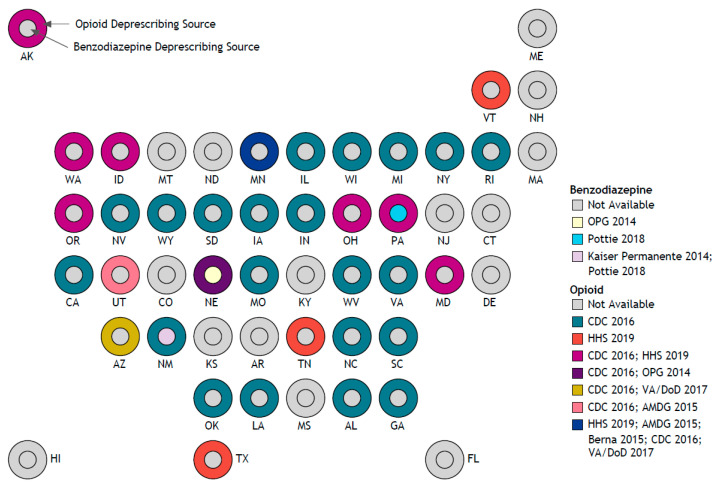

As shown in Figure 2, for opioid deprescription, 35 (70%) of the 50 US states provided resources on their state health department websites, with a majority referencing the CDC 2016 guideline [64] (n = 32) and the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) 2019 guideline [44] (n = 11), and 5 made additional recommendations [35,36,37,40,41]. For benzodiazepine deprescription, three states provide resources—Nebraska, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania—adapted from Oregon Pain Guidance [34], Kaiser Permanente [51], and Pottie et al. (2018) [54], respectively. None of the states’ health department websites provided a deprescribing schedule for concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine users.

Figure 2.

Deprescribing sources of opioid and benzodiazepine by state.

4. Discussion

The findings from our scoping review underscore the importance of developing evidence-based guidance on deprescribing concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use in clinical practice. Of the 39 original, peer-reviewed research articles, only 3 discussed strategies to deprescribe both medications when used concomitantly, and of the 26 unique practice guidelines for deprescribing opioids and/or benzodiazepines, only 4 mentioned deprescribing concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use. The deprescribing recommendations of the three original, peer-reviewed articles were widely divergent on how fast to reduce the opioid and/or benzodiazepine dose and over what time period. Cunningham et al. (2016) [31] and Gilliam et al. (2018) [32] assessed a 3-week intensive interdisciplinary rehabilitation program, whereas Zaman et al. (2018) [33] evaluated an electronic intervention in primary care for US veterans. Due to the differences in deprescribing regimens, settings, and patient populations across the three studies, it is not surprising that there was a large range of successful discontinuation of the opioid, benzodiazepine, or both (21–100%) over a large range of time (3 weeks to 6 months).

Our study also discovered limited and inconclusive evidence on which drug to deprescribe first among concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine users. While none of the three original research studies identified in our review mention the sequential order for deprescribing the two drugs, two of the identified guidelines recommended that opioids be deprescribed first [35,36], and two guidelines suggested the opposite [34,37]. Most state resources we identified cite the 2016 CDC guideline [64], which suggests tapering opioids first. However, the most recently released 2022 CDC opioid guidelines downgraded the evidence category recommendation for concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use from Category A “avoid prescribing opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines concurrently” to Category B “caution with concurrent use” and no longer recommend the sequential order for describing these two medications [38]. This recent change in the CDC opioid guidelines emphasizes the importance of (1) risk–benefit evaluations of concurrent use and (2) planning the sequential order and rate of deprescription based on individual patients’ chronic disease conditions and treatment needs [38]. Two guidelines [34,37] recommend or give an example of tapering benzodiazepines first. This may be due to the greater risks involved with benzodiazepine withdrawal than with opioid withdrawal. For example, the Minnesota Department of Human Services states that patients receiving benzodiazepines intermittently with a high daily MME are more likely to successfully deprescribe benzodiazepine first [37].

Of the 26 identified guidelines on deprescribing opioids or benzodiazepines, 22 mentioned the risk of concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use and recommended against concurrent use. In the midst of the US opioid crisis, several agencies have included concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use as a negative quality indicator to prevent potentially unsafe prescription use. For example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) included concurrent use (defined as ≥30 cumulative days during one year) on the Medicare Part D Display Page to facilitate quality improvement by the plans [65]. It is important to note that, while recommendations are often made to avoid concurrent use from the start, once this therapy has begun, there is a lack of clear guidance and agreement on deprescription other than a suggestion to provide individualized therapy in a safe and effective manner. To improve controlled-substance prescription and reduce patients’ risk of adverse outcomes such as overdose, many states have made it mandatory for prescribers and pharmacists to review a patient’s controlled-substance prescription records through prescription drug monitoring programs. This process provides opportunities to assess other controlled substances that the patient may be using and could impact deprescription initiatives and strategies.

Even though two of the three studies we included successfully deprescribed concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use over three weeks, those studies’ success can largely be attributed to an intensive rehabilitation program that may not be feasible for most patients and may not be generalizable to patients seen in ambulatory practice. In addition, of the three studies, only Gilliam et al. (2018) reported the patients’ physical and emotional functioning six months after the deprescription. There is still a knowledge gap on the net benefit of deprescribing one or both medications for concurrent users. Our previous research shows that long-term, low-dose, concurrent users were not associated with an increased risk of overdose [66]. Deprescribing strategies are generally driven by safety considerations such as high-dose use (e.g., higher doses associated with falls/fractures and overdose), high-risk populations (e.g., older adults, patients with a history of substance use disorders), likelihood of developing withdrawal symptoms, and patients’ fear of precipitated withdrawal resulting in drug-seeking patterns [36]. Therefore, to minimize negative impacts, clinicians must communicate with patients on deprescribing strategies (e.g., when to continue, pause, or discontinue the taper) and set up clear expectations of deprescribing goals (e.g., full discontinuation vs. maintaining the minimum effective dose). Alternative medication may be considered to manage the original indication, including pain (e.g., gabapentin for patients with neuropathic pain, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for patients with pain and depression or anxiety) or insomnia (e.g., trazodone for sleep disturbance) and any withdrawal symptoms (e.g., clonidine for blood pressure changes, loperamide for diarrhea). Clinicians must integrate appropriate risk–benefit ratio considerations based on individual patients’ chronic disease conditions and treatment needs with any deprescribing efforts [38]. Another factor influencing deprescribing efforts may be found in the reluctance of physicians to deprescribe or discontinue medications that were initiated or prescribed by other clinicians [67]. To remedy this challenge, there is a need for better communication and care coordination between prescribers. Appropriate coordination of patient care ensures successful and safe concurrent use deprescription, especially among older adults and those with mental health disorders [47].

Two major limitations to this scoping review are the small number of disparate studies/guidelines identified on concurrent use deprescription and the possibility of missing studies/guidelines published through other mechanisms. Although we were unable to draw a systematic recommendation or generate a deprescribing algorithm for concurrent use due to study/guideline disparity and heterogeneity, the three identified peer-reviewed studies consistently reported significant decreases in concurrent use. To mitigate the number of studies/guidelines we might have missed, we included a librarian in our search strategy development, used rigorous methods in our sampling process, and conducted backward searching of the included studies and reviews identified by our searches. Despite these limitations, this scoping review provides valuable insight for deprescribing opioids and benzodiazepines and identifies knowledge gaps for future studies.

5. Conclusions

Few deprescribing schedules are available for concurrent opioid and benzodiazepines use, and existing peer-reviewed studies and guidelines are discordant on this important topic. The current, peer-reviewed literature reports significant success for discontinuing one of the two drug classes when including an intensive rehabilitation program and moderate success for discontinuing both drug classes using other interventions. To improve patient safety and quality of care, future studies on deprescribing concurrent use should further clarify optimal strategies, particularly for high-risk populations, such as the elderly and pregnant individuals. Any deprescribing decision must be based on the individual patient’s chronic disease condition and treatment needs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julie Cunningham from Mayo Clinic for providing details on the deprescribing methods used in the studies by Cunningham (2016) and Gilliam (2018).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm12051788/s1: Table S1: PubMed search strategy; Table S2: Opioid and benzodiazepine deprescribing sources identified via state health departments; Table S3: Studies reporting details of deprescribing strategies for opioids or benzodiazepines only by country (n = 36); Table S4. Studies reporting deprescribing strategies for concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use (n = 3). References [68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103] are cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W., D.L.W., D.F., L.E.A., C.C., N.D. and W.-H.L.-C.; methodology, Y.W., D.L.W., D.F., L.E.A., A.B., C.C., N.D. and W.-H.L.-C.; software, W.-H.L.-C.; validation, Y.W., D.L.W. and D.F.; formal analysis, Y.W., D.L.W. and D.F.; investigation, Y.W., D.L.W., D.F., L.E.A., A.B., C.C., N.D., P.-L.H., A.J. and W.-H.L.-C.; resources, W.-H.L.-C.; data curation, Y.W., D.L.W., D.F., L.E.A., A.B., C.C., N.D., P.-L.H. and A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W., D.L.W., D.F. and W.-H.L.-C.; writing—review and editing, Y.W., D.L.W., D.F., L.E.A., A.B., C.C., N.D., P.-L.H., A.J., T.W.P., J.B., S.M., F.A.O., J.P., S.S., R.S., C.R.U. and W.-H.L.-C.; visualization, Y.W., D.L.W., D.F., L.E.A., A.B., C.C., N.D., P.-L.H., A.J., T.W.P., J.B., S.M., F.A.O., J.P., S.S., R.S., C.R.U. and W.-H.L.-C.; supervision, D.L.W. and W.-H.L.-C.; project administration, D.L.W. and W.-H.L.-C.; funding acquisition, W.-H.L.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article in the results section, Table 1 and Tables S2–S4, and Figure 2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. Lo-Ciganic and Wilson have received grant funding from Merck Sharp and Dohme and Bristol Myers Squibb. All these conflicts of interest are unrelated to this project.

Disclaimer

The views presented here are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs or the United States Government.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by NIH/NIA R21AG060308 and NIH/NIDA R01DA050676.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention U.S. Overdose Deaths in 2021 Increased Half as Much as in 2020—But Are Still Up 15% [(accessed on 19 July 2022)]; Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2022/202205.htm.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prescription Opioid Overdose Death Maps. [(accessed on 28 July 2022)]; Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/prescription/maps.html.

- 3.Jones C.M., McAninch J.K. Emergency Department Visits and Overdose Deaths From Combined Use of Opioids and Benzodiazepines. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015;49:493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park T.W., Saitz R., Ganoczy D., Ilgen M.A., Bohnert A.S. Benzodiazepine prescribing patterns and deaths from drug overdose among US veterans receiving opioid analgesics: Case-cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2698. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes T., Mamdani M.M., Dhalla I.A., Paterson J.M., Juurlink D.N. Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011;171:686–691. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu S., O’Donnell J., Gladden R.M., McGlone L., Chowdhury F. Trends in Nonfatal and Fatal Overdoses Involving Benzodiazepines—38 States and the District of Columbia, 2019–2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021;70:1136–1141. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7034a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dasgupta N., Funk M.J., Proescholdbell S., Hirsch A., Ribisl K.M., Marshall S. Cohort Study of the Impact of High-Dose Opioid Analgesics on Overdose Mortality. Pain Med. 2016;17:85–98. doi: 10.1111/pme.12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garg R.K., Fulton-Kehoe D., Franklin G.M. Patterns of Opioid Use and Risk of Opioid Overdose Death among Medicaid Patients. Med. Care. 2017;55:661–668. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez I., He M., Brooks M.M., Zhang Y. Exposure-Response Association Between Concurrent Opioid and Benzodiazepine Use and Risk of Opioid-Related Overdose in Medicare Part D Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw. Open. 2018;1:e180919. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawkins E.J., Goldberg S.B., Malte C.A., Saxon A.J. New Coprescription of Opioids and Benzodiazepines and Mortality Among Veterans Affairs Patients With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2019;80:18m12689. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calcaterra S.L., Severtson S.G., Bau G.E., Margolin Z.R., Bucher-Bartelson B., Green J.L., Dart R.C. Trends in intentional abuse or misuse of benzodiazepines and opioid analgesics and the associated mortality reported to poison centers across the United States from 2000 to 2014. Clin. Toxicol. 2018;56:1107–1114. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2018.1457792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Food and Drug Administration FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA Warns about Serious Risks and Death When Combining Opioid Pain or Cough Medicines with Benzodiazepines; Requires Its Strongest Warning. [(accessed on 4 September 2017)]; Available online: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM518672.pdf.

- 13.Dowell D., Haegerich T.M., Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315:1624–1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria(R) for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019;67:674–694. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeffery M.M., Hooten W.M., Jena A.B., Ross J.S., Shah N.D., Karaca-Mandic P. Rates of Physician Coprescribing of Opioids and Benzodiazepines after the Release of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines in 2016. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019;2:e198325. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Food and Drug Administration FDA Identifies Harm Reported from Sudden Discontinuation of Opioid Pain Medicines and Requires Label Changes to Guide Prescribers on Gradual, Individualized Tapering. [(accessed on 16 January 2022)]; Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/122935/download.

- 17.U.S. Food and Drug Administration FDA Requiring Boxed Warning Updated to Improve Safe Use of Benzodiazepine Drug Class Includes Potential for Abuse, Addiction, and Other Serious Risks. [(accessed on 16 January 2022)]; Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/142368/download.

- 18.Scott I.A., Hilmer S.N., Reeve E., Potter K., Le Couteur D., Rigby D., Gnjidic D., Del Mar C.B., Roughead E.E., Page A., et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: The process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015;175:827–834. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinman M., Reeve E. Deprescribing. UpToDate. 2022. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/deprescribing.

- 20.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K.K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., Moher D., Peters M.D.J., Horsley T., Weeks L., et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canadian Deprescribing Network. [(accessed on 20 July 2022)]. Available online: https://www.deprescribingnetwork.ca/canadian-deprescribing-network.

- 22.US Deprescribing Research Network US Deprescribing Research Network. [(accessed on 16 September 2022)]. Available online: https://deprescribingresearch.org/

- 23.Statista Largest Health Insurance Companies in the U.S. in 2021, by Revenue. [(accessed on 28 January 2022)]. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/985501/largest-health-insurance-companies-in-us-by-revenue/

- 24.Definitive Healthcare. Top 10 Largest Health Systems in the U.S. [(accessed on 11 November 2021)]. Available online: https://www.definitivehc.com/blog/top-10-largest-health-systems.

- 25.Lee J.Y., Farrell B., Holbrook A.M. Deprescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists taken for insomnia: A review and key messages from practice guidelines. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2019;129:43–49. doi: 10.20452/pamw.4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollmann A.S., Murphy A.L., Bergman J.C., Gardner D.M. Deprescribing benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in community-dwelling adults: A scoping review. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2015;16:19. doi: 10.1186/s40360-015-0019-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nickerson K., Lieschke G., Rajappa H., Smith A., Inder K.J. A scoping review of outpatient interventions to support the reduction of prescription opioid medication for chronic non cancer pain. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022;31:3368–3389. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Kleijn L., Pedersen J.R., Rijkels-Otters H., Chiarotto A., Koes B. Opioid reduction for patients with chronic pain in primary care: Systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2022;72:e293–e300. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis M.P., Digwood G., Mehta Z., McPherson M.L. Tapering opioids: A comprehensive qualitative review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020;9:586–610. doi: 10.21037/apm.2019.12.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathieson S., Maher C.G., Ferreira G.E., Hamilton M., Jansen J., McLachlan A.J., Underwood M., Lin C.C. Correction to: Deprescribing Opioids in Chronic Noncancer Pain: Systematic Review of Randomised Trials. Drugs. 2020;80:1577–1578. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunningham J.L., Evans M.M., King S.M., Gehin J.M., Loukianova L.L. Opioid Tapering in Fibromyalgia Patients: Experience from an Interdisciplinary Pain Rehabilitation Program. Pain Med. 2016;17:1676–1685. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnv079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilliam W.P., Craner J.R., Cunningham J.L., Evans M.M., Luedtke C.A., Morrison E.J., Sperry J.A., Loukianova L.L. Longitudinal Treatment Outcomes for an Interdisciplinary Pain Rehabilitation Program: Comparisons of Subjective and Objective Outcomes on the Basis of Opioid Use Status. J. Pain. 2018;19:678–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaman T., Rife T.L., Batki S.L., Pennington D.L. An electronic intervention to improve safety for pain patients co-prescribed chronic opioids and benzodiazepines. Subst. Abus. 2018;39:441–448. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2018.1455163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oregon Pain Guidance of Southern Oregon. Opioid Prescribing Guidelines: A Provider and Community Resource. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]. Available online: https://www.virginiapremier.com/wp-content/uploads/OPG_Guidelines.pdf.

- 35.Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services Nebraska Pain Management Guidance Document: A Provider and Community Resource. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]; Available online: https://dhhs.ne.gov/Guidance%20Docs/Pain%20Management%20Pain%20Guidance%20Document.pdf#search=opioid%20prescribing.

- 36.Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group Interagency Guideline on Prescribing Opioids for Pain. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]; Available online: https://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/files/2015amdgopioidguideline.pdf.

- 37.Minnesota Department of Human Services Tapering and Discontinuing Opioid Use. [(accessed on 28 July 2022)]; Available online: https://mn.gov/dhs/opip/opioid-guidelines/tapering-opioids/

- 38.Dowell D., Ragan K.R., Jones C.M., Baldwin G.T., Chou R. CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain—United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2022;71:1–95. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Use of Opioids in the Management of Chronic Pain. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]; Available online: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot/VADoDOpioidsCPG.pdf.

- 40.Oregon Health Authority Public Health Division Oregon Opioid Tapering Guidelines. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]; Available online: https://www.oregon.gov/omb/Topics-of-Interest/Documents/Oregon-Opioid-Tapering-Guidelines.pdf.

- 41.Arizona Department of Health Services Arizona Opioid Prescribing Guidelines. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]; Available online: https://www.azdhs.gov/documents/audiences/clinicians/clinical-guidelines-recommendations/prescribing-guidelines/az-opioid-prescribing-guidelines.pdf.

- 42.Cigna Patient-Centered Safe Opioid Tapering Resource Guide. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]. Available online: https://chk.static.cigna.com/assets/chcp/pdf/resourceLibrary/prescription/opioid-taper-resources.pdf.

- 43.United Healthcare Services Inc Opioid Tapering Recommendations. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]. Available online: https://www.bhoptions.com/-/media/Files/HPN/pdf/Provider-Services/Opioid-Tapering-Recommendations.ashx?la=en.

- 44.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services HHS Guide for Clinicians on the Appropriate Dosage Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-Term Opioid Analgesics. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]; Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf.

- 45.Sunshine Health. Recommendations for Discontinuing and Tapering Opioids. 2022. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]. Available online: https://www.sunshinehealth.com/content/dam/centene/Sunshine/pdfs/SH-PRO-Opioid%20Tapering%20_083120_DIGITAL.pdf.

- 46.Mendoza M., Russell H.A. Is it time to taper that opioid? (And how best to do it) J. Fam. Pract. 2019;68:324–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lumish R., Goga J.K., Brandt N.J. Optimizing Pain Management Through Opioid Deprescribing. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2018;44:9–14. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20171213-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy L., Babaei-Rad R., Buna D., Isaac P., Murphy A., Ng K., Regier L., Steenhof N., Zhang M., Sproule B. Guidance on opioid tapering in the context of chronic pain: Evidence, practical advice and frequently asked questions. Can. Pharm. J. 2018;151:114–120. doi: 10.1177/1715163518754918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Opioid Taper Decision Tool: A VA Clinician’s Guide. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]; Available online: https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/AcademicDetailingService/Documents/Pain_Opioid_Taper_Tool_IB_10_939_P96820.pdf.

- 50.Berna C., Kulich R.J., Rathmell J.P. Tapering Long-term Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: Evidence and Recommendations for Everyday Practice. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015;90:828–842. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaiser Permanente Benzodiazepine and Z-Drug Safety Guideline. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]. Available online: https://wa.kaiserpermanente.org/static/pdf/public/guidelines/benzo-zdrug.pdf.

- 52.Payne R.A., Joshi K.G. Helping patients through a benzodiazepine taper. Curr. Psychiatry. 2019;18:9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Presbyterian Healthcare Services Benzodiazepines: Tapering and Prescribing. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]. Available online: https://onbaseext.phs.org/PEL/DisplayDocument?ContentID=pel_00943236.

- 54.Pottie K., Thompson W., Davies S., Grenier J., Sadowski C.A., Welch V., Holbrook A., Boyd C., Swenson R., Ma A., et al. Deprescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can. Fam. Physician. 2018;64:339–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choosing Wisely Canada. A Toolkit for Reducing Inappropriate Use of Benzodiazepines and Sedative-Hypnotics among Older Adults in Hospitals. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]. Available online: https://choosingwiselycanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/CWC_BSH_Hospital_Toolkit_v1.3_2017-07-12.pdf.

- 56.Choosing Wisely Canada. A Toolkit for Reducing Inappropriate Use of Benzodiazepines and Sedative-Hypnotics among Older Adults in Primary Care. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]. Available online: https://choosingwiselycanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/CWC-Toolkit-BenzoPrimaryCare-V3.pdf.

- 57.deprescribing.org. Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonist Deprescribing Algorithm. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]. Available online: https://deprescribing.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/deprescribing_algorithms2019_BZRA_vf-locked.pdf.

- 58.CalOptima Deprescribing Benzodiazepines in Older Adults. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]. Available online: https://www.caloptima.org/~/media/Files/CalOptimaOrg/508/Providers/Pharmacy/Medi-Cal/Updates/2021-08_DeprescribingBenzodiazepines_508.ashx.

- 59.Pruskowski J., Rosielle D.A., Pontiff L., Reitschuler-Cross E. Deprescribing and Tapering Benzodiazepines #355. J. Palliat. Med. 2018;21:1040–1041. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ogbonna C.I., Lembke A. Tapering Patients Off of Benzodiazepines. Am. Fam. Physician. 2017;96:606–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Effective Treatments for PTSD: Helping Patients Taper from Benzodiazepines. [(accessed on 12 July 2022)]; Available online: https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/AcademicDetailingService/Documents/Academic_Detailing_Educational_Material_Catalog/59_PTSD_NCPTSD_Provider_Helping_Patients_Taper_BZD.pdf.

- 62.Bélanger L., Belleville G., Morin C.M. Management of Hypnotic Discontinuation in Chronic Insomnia. Sleep Med. Clin. 2009;4:583–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woodward M.C. Deprescribing: Achieving Better Health Outcomes for Older People Through Reducing Medications. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2003;33:323–328. doi: 10.1002/jppr2003334323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dowell D., Haegerich T.M., Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2016;65:1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Part C and D Performance Data. [(accessed on 20 December 2022)]; Available online: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/PerformanceData.

- 66.Lo-Ciganic W.H., Hincapie-Castillo J., Wang T., Ge Y., Jones B.L., Huang J.L., Chang C.Y., Wilson D.L., Lee J.K., Reisfield G.M., et al. Dosing profiles of concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use associated with overdose risk among US Medicare beneficiaries: Group-based multi-trajectory models. Addiction. 2022;117:1982–1997. doi: 10.1111/add.15857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Linsky A., Simon S.R., Marcello T.B., Bokhour B. Clinical provider perceptions of proactive medication discontinuation. Am. J. Manag. Care. 2015;21:277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Darnall B.D., Ziadni M.S., Stieg R.L., Mackey I.G., Kao M.C., Flood P. Patient-Centered Prescription Opioid Tapering in Community Outpatients with Chronic Pain. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018;178:707–708. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goodman M.W., Guck T.P., Teply R.M. Dialing back opioids for chronic pain one conversation at a time. J. Fam. Pract. 2018;67:753–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sullivan M.D., Turner J.A., DiLodovico C., D’Appollonio A., Stephens K., Chan Y.F. Prescription Opioid Taper Support for Outpatients With Chronic Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pain. 2017;18:308–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kurita G.P., Hojsted J., Sjogren P. Tapering off long-term opioid therapy in chronic non-cancer pain patients: A randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Pain. 2018;22:1528–1543. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang H., Akbar M., Weinsheimer N., Gantz S., Schiltenwolf M. Longitudinal observation of changes in pain sensitivity during opioid tapering in patients with chronic low-back pain. Pain Med. Malden Mass. 2011;12:1720–1726. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fung C.H., Martin J.L., Alessi C., Dzierzewski J.M., Cook I.A., Moore A., Grinberg A., Zeidler M., Kierlin L. Hypnotic Discontinuation Using a Blinded (Masked) Tapering Approach: A Case Series. Front. Psychiatry. 2019;10:717. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gorenstein E.E., Kleber M.S., Mohlman J., Dejesus M., Gorman J.M., Papp L.A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for management of anxiety and medication taper in older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2005;13:901–909. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.10.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hadley S.J., Mandel F.S., Schweizer E. Switching from long-term benzodiazepine therapy to pregabalin in patients with generalized anxiety disorder: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:461–470. doi: 10.1177/0269881111405360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rickels K., DeMartinis N., Garcia-Espana F., Greenblatt D.J., Mandos L.A., Rynn M. Imipramine and buspirone in treatment of patients with generalized anxiety disorder who are discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine therapy. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:1973–1979. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rosenbaum J.F., Moroz G., Bowden C.L. Clonazepam in the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: A dose-response study of efficacy, safety, and discontinuance. Clonazepam Panic Disorder Dose-Response Study Group. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:390–400. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199710000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roy-Byrne P., Russo J., Pollack M., Stewart R., Bystrisky A., Bell J., Rosenbaum J., Corrigan M.H., Stolk J., Rush A.J., et al. Personality and symptom sensitivity predictors of alprazolam withdrawal in panic disorder. Psychol. Med. 2003;33:511–518. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703007402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rynn M., Garcia-Espana F., Greenblatt D.J., Mandos L.A., Schweizer E., Rickels K. Imipramine and buspirone in patients with panic disorder who are discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine therapy. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:505–508. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000088907.24613.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schweizer E., Case W.G., Garciaespana F., Greenblatt D.J., Rickels K. Progesterone coadministration in patients discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine therapy—Effects on withdrawal severity and taper outcome. Psychopharmacology. 1995;117:424–429. doi: 10.1007/BF02246214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baillargeon L., Landreville P., Verreault R., Beauchemin J.P., Gregoire J.P., Morin C.M. Discontinuation of benzodiazepines among older insomniac adults treated with cognitive-behavioural therapy combined with gradual tapering: A randomized trial. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2003;169:1015–1020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Belanger L., Morin C.M., Bastien C., Ladouceur R. Self-efficacy and compliance with benzodiazepine taper in older adults with chronic insomnia. Health Psychol. 2005;24:281–287. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Belleville G., Guay C., Guay B., Morin C.M. Hypnotic taper with or without self-help treatment of insomnia: A randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007;75:325–335. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dellechiaie R., Pancheri P., Casacchia M., Stratta P., Kotzalidis G.D., Zibellini M. Assessment of the efficacy of buspirone in patients affected by generalized anxiety disorder, shifting to buspirone from prior treatment with lorazepam—A placebo-controlled, double-blind-study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1995;15:12–19. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gosselin P., Ladouceur R., Morin C.M., Dugas M.J., Baillargeon L. Benzodiazepine discontinuation among adults with GAD: A randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006;74:908–919. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morin C.M., Colecchi C.A., Ling W.D., Sood R.K. Cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation among hypnotic-dependent patients with insomnia. Behav. Ther. 1995;26:733–745. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80042-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Morin C.M., Bastien C., Guay B., Radouco-Thomas M., Leblanc J., Vallieres A. Randomized clinical trial of supervised tapering and cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with chronic insomnia. Am. J. Psychiat. 2004;161:332–342. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morin C.M., Belanger L., Bastien C., Vallieres A. Long-term outcome after discontinuation of benzodiazepines for insomnia: A survival analysis of relapse. Behav. Res. Ther. 2005;43:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.O’Connor K., Marchand A., Brousseau L., Aardema F., Mainguy N., Landry P., Savard P., Léveillé C., Lafrance V., Boivin S., et al. Cognitive-behavioural, pharmacological and psychosocial predictors of outcome during tapered discontinuation of benzodiazepine. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2008;15:1–14. doi: 10.1002/cpp.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tannenbaum C., Martin P., Tamblyn R., Benedetti A., Ahmed S. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: The EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174:890–898. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Baandrup L., Glenthoj B.Y., Jennum P.J. Objective and subjective sleep quality: Melatonin versus placebo add-on treatment in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder withdrawing from long-term benzodiazepine use. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Curran H.V., Collins R., Fletcher S., Kee S.C., Woods B., Iliffe S. Older adults and withdrawal from benzodiazepine hypnotics in general practice: Effects on cognitive function, sleep, mood and quality of life. Psychol. Med. 2003;33:1223–1237. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mercier-Guyon C., Chabannes J.P., Saviuc P. The role of captodiamine in the withdrawal from long-term benzodiazepine treatment. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2004;20:1347–1355. doi: 10.1185/030079904125004457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Oude Voshaar R.C., Gorgels W., Mol A.J.J., Van Balkom A., Van de Lisdonk E.H., Breteler M.H.M. Tapering off long-term benzodiazepine use with or without group cognitive-behavioural therapy: Three-condition, randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2003;182:498–504. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.6.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rubio G., Bobes J., Cervera G., Teran A., Perez M., Lopez-Gomez V., Rejas J. Effects of Pregabalin on Subjective Sleep Disturbance Symptoms during Withdrawal from Long-Term Benzodiazepine Use. Eur. Addict. Res. 2011;17:262–270. doi: 10.1159/000324850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vicens C., Fiol F., Llobera J., Campoamor F., Mateu C., Alegret S., Socias I. Withdrawal from long-term benzodiazepine use: Randomised trial in family practice. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2006;56:958–963. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vicens C., Bejarano F., Sempere E., Mateu C., Fiol F., Socias I., Aragonès E., Palop V., Beltran J.L., Piñol J.L., et al. Comparative efficacy of two interventions to discontinue long-term benzodiazepine use: Cluster randomised controlled trial in primary care. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2014;204:471–479. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.134650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vorma H., Naukkarinen H., Sarna S., Kuoppasalmi K. Treatment of out-patients with complicated benzodiazepine dependence: Comparison of two approaches. Addict. 2002;97:851–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zitman F.G., Couvee J.E. Chronic benzodiazepine use in general practice patients with depression: An evaluation of controlled treatment and taper-off—Report on behalf of the Dutch Chronic Benzodiazepine Working Group. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2001;178:317–324. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.4.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cardinali D.P., Gvozdenovich E., Kaplan M.R., Fainstein I., Shifis H.A., Pérez Lloret S., Albornoz L., Negri A. A double blind-placebo controlled study on melatonin efficacy to reduce anxiolytic benzodiazepine use in the elderly. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2002;23:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kitajima R., Miyamoto S., Tenjin T., Ojima K., Ogino S., Miyake N., Fujiwara K., Funamoto Y., Arai J., Tsukahara S., et al. Effects of tapering of long-term benzodiazepines on cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia receiving a second-generation antipsychotic. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;36:300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nakao M., Takeuchi T., Nomura K., Teramoto T., Yano E. Clinical application of paroxetine for tapering benzodiazepine use in non-major-depressive outpatients visiting an internal medicine clinic. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006;60:605–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yang C.M., Tseng C.H., Lai Y.S., Hsu S.C. Self-efficacy enhancement can facilitate hypnotic tapering in patients with primary insomnia. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2015;13:242–251. doi: 10.1111/sbr.12111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article in the results section, Table 1 and Tables S2–S4, and Figure 2.