Abstract

A private–academic partnership built the Vaccine Equity Planner (VEP) to help decision-makers improve geographic access to COVID-19 vaccinations across the United States by identifying vaccine deserts and facilities that could fill those deserts. The VEP presented complex, updated data in an intuitive form during a rapidly changing pandemic situation. The persistence of vaccine deserts in every state as COVID-19 booster recommendations develop suggests that vaccine delivery can be improved. Underresourced public health systems benefit from tools providing real-time, accurate, actionable data. (Am J Public Health. 2023;113(4):363–367. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.307198)

Public health leaders can make better, more equitable decisions when they can clearly see and understand the problems. Being presented with potential solutions based on evidence further supports their decision-making and can aid in supporting health equity.

INTERVENTION AND IMPLEMENTATION

We built the Vaccine Equity Planner (VEP) in spring 2021. We intended the VEP to serve US public health planners as an open-access online tool with four main functions:

-

1.

Identify COVID-19 vaccine deserts for both adults and children;

-

2.

Identify facilities within vaccine deserts that could serve as vaccination sites;

-

3.

Focus on specific geographic areas, such as those with high social vulnerability; and

-

4.

Estimate the size of the unvaccinated population in each county as well as the population’s intention to be vaccinated.

We plotted all active COVID-19 vaccination site locations, calculating a catchment area around each site based on the amount of time to reach that site by different methods of transportation (walking, public transit, driving). We defined “vaccine deserts” as areas that did not fall within the catchment area of any in-state vaccination site.1 To identify potential vaccination sites in the deserts, we used publicly available, national, updated data sets of facilities that people would “very likely” trust to get vaccinated: doctors’ offices, pharmacies, community health clinics, schools, grocery stores, and churches or religious centers. We repeated this process using only vaccination sites offering the Pfizer age 12 years and up vaccine and the Pfizer age 5–11 years vaccine (the only vaccines available under emergency use authorization for the pediatric population at the time) to create pediatric vaccine deserts. As vaccines were approved for different age demographics, we added additional displays to the tool.

We overlaid our map with data from the Social Vulnerability Index and data on intention to be vaccinated from the COVID-19 Trends and Impact Survey (for full data sources and methods, see Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We sought feedback from potential users and refined the design and tool accordingly.

We directly disseminated the VEP by e-mail to all state- and jurisdiction-level health commissioners with publicly available contact information and shared the tool on social media. Several leaders and the Association of Immunization Managers responded to our communications with requests for training on the tool, specific data, updates to the tool, or other queries, which we addressed.

PLACE, TIME, AND PERSONS

Our target user was a state or county public health planner in the United States who wanted to expand geographic access to COVID-19 vaccination in their jurisdiction. We refreshed data on vaccination sites, vaccine deserts, and potential vaccination sites weekly starting in June 2021 as demand for vaccination fell.

PURPOSE

Vaccines reduce hospitalization and the risk of escape variants, supporting pandemic response.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified vaccine hesitancy into “three Cs”: people may lack confidence in the effectiveness or safety of the vaccine, may feel complacent about the risk and severity of the disease, or may not have convenient access to the vaccine.3 In the United States, these three Cs vary, resulting in inequitable uptake of vaccines and, in turn, differential disease burden of COVID-19.4

One common method for understanding convenience or geographic access to services is the “desert,” an area devoid of the service in question. Unfortunately, in spring 2021, few US public health departments had the bandwidth available to collect and analyze data from disparate sources to identify COVID-19 deserts and potential ways to ameliorate them.

To provide planners with the necessary data for increasing equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines, members from Ariadne Labs, the Computational Epidemiology Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital, and Google collaborated to gather, curate, and display data from various public sources. The aim was to identify COVID-19 deserts and potential vaccination sites within those deserts as well as share the population’s social vulnerability and intentions to be vaccinated. The goal was to enable better-informed public health planning and decision-making.

EVALUATION AND ADVERSE EFFECTS

We launched the VEP on May 24, 2021. By September 20, 2021, it had roughly 7400 unique page views originating within the United States. Nearly 70% of the incoming Web traffic originated from direct entry of the URL to a browser, suggesting that spread occurred through our communication campaign and word of mouth.

Vaccine Deserts

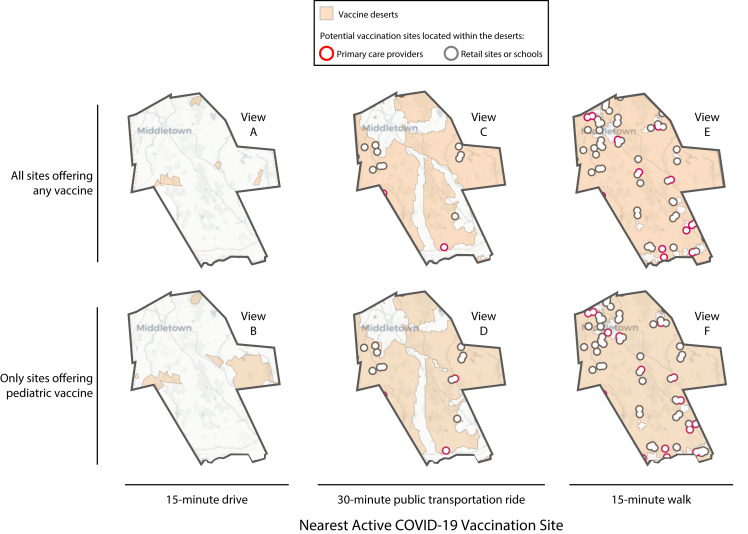

Vaccine deserts existed in every US state, but the extent and location of those deserts depended on the chosen transportation mode and travel time. In general, vaccine deserts were more expansive when the transportation mode was public transit or walking. Additionally, pediatric vaccine deserts tended to be more expansive than adult vaccine deserts because not all vaccination sites offered the Pfizer age 5–11 years vaccine. Many vaccine deserts had one or more potential vaccination sites, including primary care sites, schools, and retail sites (Figure 1, county anonymized).

FIGURE 1—

Vaccine Deserts in 1 Sample US County, by Travel Mode, Travel Time, and Vaccine Type: November 10, 2022

Note. A vaccine desert is an area that does not have access to an active COVID-19 site within the time and by the transportation method selected.

Potential Vaccination Sites Located in Deserts

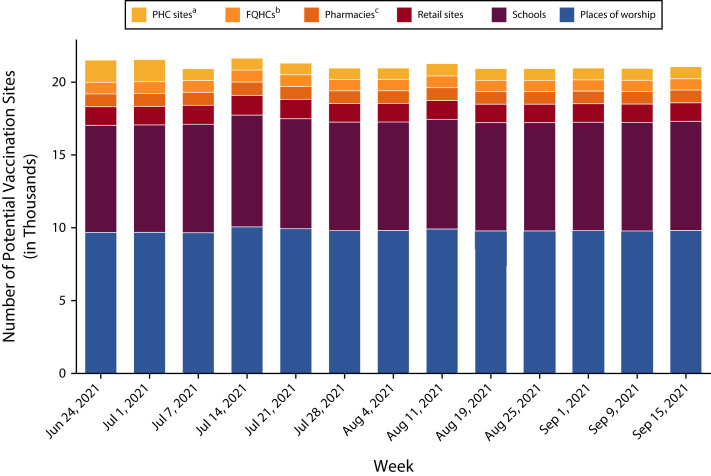

Over 13 weeks with available data, the VEP identified approximately 21 000 potential vaccination sites across the United States. Most of these sites were places of worship (10 000), schools (7000–8000), or retail sites (1000). The smallest categories—with fewer than 1000 potential sites each—included health-related facilities that were not already providing COVID-19 vaccination: primary care sites, federally qualified health centers, and pharmacies (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Number of Potential Vaccination Sites Located in Vaccine Deserts, by Week and Type of Site: United States, June 24–September 15, 2021

Note. FQHC = Federally qualified health center; PHC = Primary health care. A vaccine desert is an area outside a 15-minute drive to the nearest active COVID-19 vaccination site.

aIncludes family medicine physicians, internal medicine physicians, pediatricians, and general practitioners.

bFQHC not already vaccinating.

cPharmacies not already vaccinating.

SUSTAINABILITY

There is great potential for intersectoral partnerships to support public health leaders by leveraging data, analytic, communication, and technological skills to generate evidence to support decision-making. The VEP continues to support the Association of Immunization Managers in increasing vaccine access across its jurisdictions.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

The VEP revealed vaccine deserts in every US state. In general, it showed that vaccine deserts were more common in rural areas, and many potential vaccination sites within these deserts were schools; however, there are also many untapped medical clinics.

A successful response to the COVID-19 pandemic is supported by widespread, equitable access to the COVID-19 vaccines. Geographic access is necessary to the WHO’s convenience factor and is a potentially powerful lever for increasing equity of access. Surveys have found that 15% of unvaccinated people are concerned about the difficulty of traveling to a vaccination site, and 20% are concerned about the need to take time off work, which would be exacerbated by long travel times.4 Additionally, geographic access can support the confidence of unvaccinated people: 53% of unvaccinated people report that they were more likely to accept the vaccine from their own trusted health care provider, such as a primary health care site, family medicine physician, or pediatrician, compared with other types of sites.5 Improving local access leads to local reporting from friends and neighbors communicating why they got vaccinated and boosted, and the unvaccinated are influenced by their peers.6

In the rapid deployment of COVID-19 vaccines in the United States, the barriers to equitable distribution were numerous and closely related to larger structural barriers in public health delivery.7 Planners had to consider a population’s confidence and complacency regarding vaccines, as well as to promote convenient access, which would support equitable distribution to the most vulnerable.3,8 Meeting these goals required a certain bandwidth to analyze data, understand needs, and plan accordingly. After months of battling the pandemic, not all public health departments in the United States had the time or resources to do so. For our part, we will consider applying what we have learned from building the VEP to display other clinical and service deserts. The VEP was built through a partnership between academia and the private sector, and further investment is needed to promote such collaboration to build tools to support data-driven public health decision-making.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Ariadne Labs COVID-19 Vaccine Delivery team was funded in part by The Commonwealth Fund. The Computational Epidemiology Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Facebook, and The Rockefeller Foundation. HealthLandscape provided some of the data used.

Thank you to all reviewers and public health leaders who provided feedback.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No human participants were involved in the conduct of this research. Therefore, this study has not been subject to review by an institutional review board.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rader B, Astley CM, Sewalk K, et al. medRxiv 2021. 10.1101/2021.06.09.21252858 [DOI]

- 2.Read AF, Baigent SJ, Powers C, et al. Imperfect vaccination can enhance the transmission of highly virulent pathogens. PLoS Biol. 2015;13(7):e1002198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SAGE Working Group. Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser Family Foundation. 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity

- 5.American COVID-19 Vaccine Poll. 2021. https://covidvaccinepoll.com/app/aarc/covid-19-vaccine-messaging/#

- 6.Schneider KE, Dayton L, Rouhani S, Latkin CA. Implications of attitudes and beliefs about COVID-19 vaccines for vaccination campaigns in the United States: a latent class analysis. Prev Med Rep. 2021;24:101584. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen AK, Hughes Iv R, DeWald E, Rosenbaum S, Pisani A, Orenstein W. Ensuring equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines in the US: current system challenges and opportunities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(1):62–69. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaiser Family Foundation. 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-experiences-vaccine-access-information-needs