Abstract

Background: The recent introduction of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) smartphone-based strategies has allowed achieving some interesting data on the frequency of different awake bruxism (AB) behaviors reported by an individual in the natural environment. Objective: The present paper aims to review the literature on the reported frequency of AB based on data gathered via smartphone EMA technology. Methods: On September 2022, a systematic search in the Pubmed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases was performed to identify all peer-reviewed English-language studies assessing awake bruxism behaviors using a smartphone-based Ecological Momentary Assessment. The selected articles were assessed independently by two authors according to a structured reading of the articles’ format (PICO). Results: A literature search, for which the search terms “Awake Bruxism” and “Ecological Momentary Assessment” were used, identified 15 articles. Of them, eight fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The results of seven studies using the same smartphone-based app reported a frequency of AB behaviors in the range between 28.3 and 40% over one week, while another investigation adopted a different smartphone-based EMA approach via WhatsApp using a web-based survey program and reported an AB frequency of 58.6%. Most included studies were based on convenience samples with limited age range, highlighting the need for more studies on other population samples. Conclusions: Despite the methodological limits, the results of the reviewed studies provide a standpoint for comparison for future studies on the epidemiology of awake bruxism behaviors.

Keywords: bruxism, awake bruxism, ecological momentary assessment, masticatory muscle activity

1. Introduction

Bruxism is an oral condition that is gaining increasing attention in several disciplines, such as dentistry, psychology, neurology, and sleep medicine.

Recently, a panel of experts provided separate definitions for awake bruxism (AB) and sleep bruxism (SB).

Awake Bruxism (AB) is currently defined as a masticatory muscle activity (MMA) during wakefulness that is characterized by repetitive or sustained tooth contact and/or by bracing or thrusting of the mandible and is not a movement disorder in otherwise healthy individuals [1].

Sleep bruxism (SB) is a masticatory muscle activity during sleep that is characterized as rhythmic (phasic) or non-rhythmic (tonic) and is not a movement disorder or a sleep disorder in otherwise healthy individuals [1].

In accordance with these definitions, AB must be distinguished from SB, which may have different etiology, comorbidities, and consequences because of the different spectrum of muscle activities exerted in relation to the different circadian manifestation.

The prevalence of AB has been reported to be up to 30% across populations, while SB prevalence has been reported to be 6–8% [2]. Nevertheless, until now, most research has focused on SB, while knowledge of AB is fragmental, and less literature data on AB are available compared to SB [2]. There are few epidemiological data on AB, and the findings are not easy to summarize due to the adoption of different assessment strategies. In addition, most of the information on AB prevalence has been reported from research on single-observation point studies [1,2,3,4,5].

Consequently, as part of the works that led to the definition of the Standardized Tool for the Assessment of Bruxism (STAB), [6] the use of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) strategies to report AB behaviors has been recommended and adopted in several studies [1,2,3,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], based on its potential usefulness as a simple method to collect real-time data in the natural environment. Such procedure is also referred to as experience sampling method (ESM) and requires a real-time report of behaviors or feelings, in relation to whichever condition is being studied (e.g., AB behaviors) [21]. In short, over a time frame within the course of daily affairs, an individual is prompted at fixed or random time points to answer questions about what he/she is currently doing and/or experiencing. Doing so, multiple recording points during the day, close in time to the experience in the natural environment, are allowed [22].

Over the years, EMA approaches have been introduced in the field of AB investigations [23,24], with a recent focus on the development of smartphone-based strategies to collect data in the clinical and research settings. By using this strategy, a patient receives information on the smartphone application to use and the instructions on how to use it. Upon receiving an alert, the subjects have to focus on their current oral condition and tap on the corresponding display icon (e.g., relaxed jaw muscles, teeth contact, teeth clenching, teeth grinding, mandible bracing) [7,8]. Such approach allows the collection of data regarding the frequency of the different AB activities reported by an individual in the natural environment. Nonetheless, despite the potential advantages of using this strategy being quite intuitive, also as far as patients’ education purposes are concerned, there are so far only little available data. Studies over a one-week period described a quite wide range of average frequency values for AB behaviors in otherwise healthy young adults [8,10,11,12,13,14,19]. Concerning the specific behaviors, teeth contact is the most common finding, whilst the report of teeth grinding is almost absent. This approach is in line with the need to collect as much data as possible to understand which degree of AB behaviors may become harmful, if any [25,26].

In view of this, it is important to summarize the current findings in this emerging research field to provide a basis for comparisons as well as possible suggestions for future research. Within these premises, a scoping review was performed to report on AB prevalence data gathered via smartphone-based EMA technology.

2. Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

On 10 September 2022, a systematic search of the literature was performed to identify all peer-reviewed English-language citations that were relevant to the review topic, viz., smartphone-based Ecological Momentary Assessment of Awake Bruxism.

As a first step, a search using Medical Subjects Headings (MeSH) terms in the National Library of Medicine Medline (PubMed) database was performed by using the query “Awake Bruxism” AND “Ecological Momentary Assessment” to identify a list of potential papers for inclusion. As a next step, the same strategy was adopted to identify papers in the Scopus and Google Scholar databases. In addition, search expansion strategies were adopted to identify any additional potentially relevant citation (i.e., related articles, hands-on search in private libraries, reference lists of the included articles). The literature search was limited to all the articles on adult populations (>18 years). The inclusion criteria were limited to: (1) studies written in English, (2) papers focused on the frequency of AB evaluated via a smartphone-based EMA approach.

The selected articles were read according to a PICO-like structured strategy (i.e., Population/Intervention/Comparison/Outcome). The population (“P”) was described in terms of sample size, inclusion criteria, and demographic characteristics. The intervention (“I”) concerned information on the study design, the assessment approach, the number and qualification of the examiners and the statistical analysis. The comparison (“C”) included data on the control group depending on the study design, if it is present. The outcome (“O”) was reported in terms of AB frequency data. The main conclusions of each study’s authors were also included.

Two of the authors (A.C., A.B.) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all articles and performed a full-text eligibility check. The articles that were potentially meeting the inclusion criteria for the review were retrieved in full text. In all cases of doubt regarding the potential inclusion of an article or data interpretation, the main supervisor (D.M.) was involved. All the leading authors of the included investigations were contacted to join the review team and contribute to the expansion of the research strategy in the additional steps. Each of them also contributed with a handmade search in his/her own university library catalogue. Once the review team agreed on the articles included in the review, the two main reviewers performed data extraction based on the above-described PICO strategy. Some authors involved in the STAB preparation were also invited to contribute to the literature review discussion.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

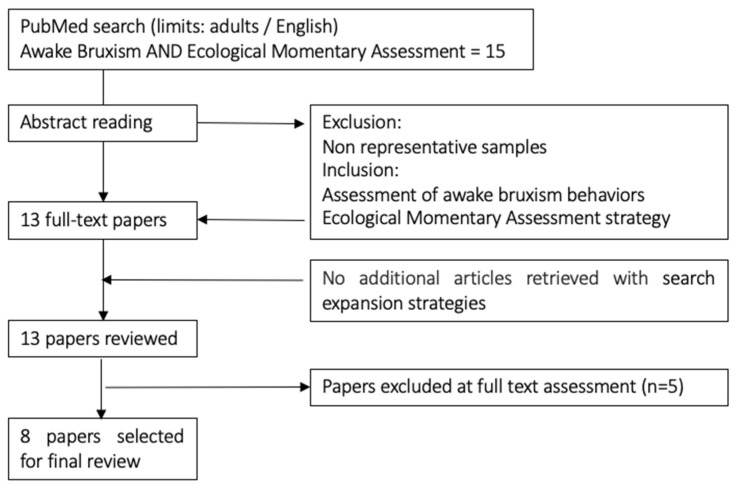

The literature search identified 15 articles. Title and abstract reading led to the exclusion of two articles, which were clearly not relevant [20,27]. The full text for the remaining 13 articles was retrieved. Of these, five were excluded [7,9,15,16,17] for not fulfilling the inclusion criteria, (i.e., the reason for exclusion was No information about AB frequency); thus, a total of eight papers [8,10,12,13,14,16,18,19] were included in the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature search strategy. Different steps and criteria for the selection of papers.

The included papers covered a wide spectrum of populations of different sex, age and ethnic background. The studies were performed on subjects living in Italy, Portugal, Israel and Brazil. The age of the subjects varied from 19 to 35 years, and the sample size ranged from 30 to 151. Regarding the sex distribution, a predominance of females was found.

3.2. Summary of the Studies

Several studies had common methodological features. In most cases, the study sample was represented by students and/or by a restricted age group, and the majority of the participants were females (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the findings from studies included in the final review. PICO Table.

| Study’s First Author and Year | Population (Patients/Problem) | Intervention | Comparison (Control Group) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bracci et al., 2018 [8] | N = 46 (26 F, 20 M; m.a. 24.2 ± 1.7) Italy University students |

Ecological momentary assessment using a dedicated smartphone application to record a real-time report on AB behaviors | Not applicable | AB frequency: 28.3% |

| Zani et al., 2019 [10] | N = 30 (21 F, 9 M; 24 ± 3.5) Italy University students |

Ecological momentary assessment using a dedicated smartphone application to record a real-time report on AB behaviors | Not applicable | AB frequency: 38% |

| Pereira NC et al., 2020 [18] | N = 38 (15 F, 23 M; m.a. 22.1) Brazil Subjects representative of the general population |

Ecological momentary assessment using an online device (mentimeter) to record a real-time report on AB behaviors | Not applicable | AB frequency: 58.6% |

| Câmara-Souza et al., 2020 [13] | N = 69 (50 F, 19 M; m.a. 18.6 ± 1.5) Brazil University students |

Ecological momentary assessment using a dedicated smartphone application to record a real-time report on AB behaviors | Not applicable | AB frequency: 38.4% |

| Zani et al., 2021 [14] | N = 153 (93 F, 60 M; m.a. 22.9 ± 3.2) Italy University students |

Ecological momentary assessment using a dedicated smartphone application to record a real-time report on AB behaviors | Not applicable | AB frequency: 23.6 |

| Dias et al., 2021 [12] | N = 31 (27 F, 4 M; a.r. 20–24) Portugal University students |

Ecological momentary assessment using a dedicated smartphone application to record a real-time report on AB behaviors | Not applicable | AB frequency: 37.5% |

| Emodi-Perlman et al., 2021 [16] | N = 106 (67 F, 39 M; m.a. 24.4 ± 2.99) Israel University students |

Ecological momentary assessment using a dedicated smartphone application to record a real-time report on AB behaviors | Not applicable | AB frequency: 40.3% |

| Bucci et al., 2022 [19] | N = 151 (99 F, 52 M; m.a. 27.2 ± 8.1) Italy Subjects representative of the general population |

Ecological momentary assessment using a dedicated smartphone application to record a real-time report on AB behaviors | Not applicable | AB frequency: 37.5% |

m.a., mean age; a.r., age range; AB, awake bruxism.

In all studies [8,10,12,13,14,16,18,19], in order to evaluate AB behaviors, the participants had to answer (i.e., EMA) by tapping on the display within 5 min from the alert on the current condition of their jaw muscles, and they were monitored over a one-week period; in some cases, intervals of several weeks were also evaluated [10,12]. All studies [8,10,12,13,14,16,19] except one [18] adopted the same smartphone-based application.

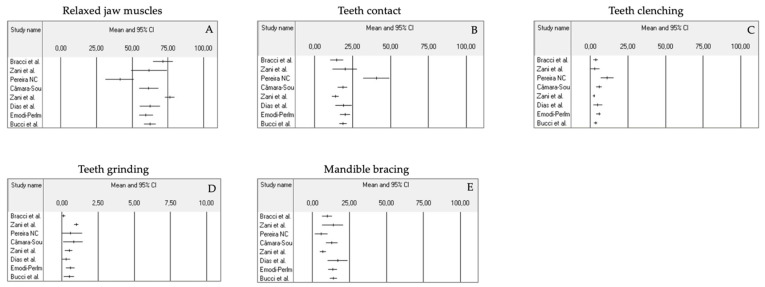

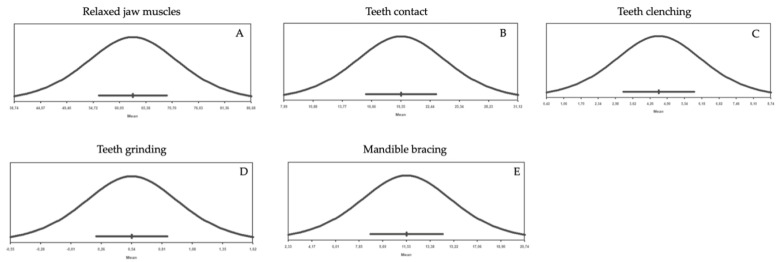

The findings in the eight papers suggested that the frequency of AB behaviors report (i.e., the percentage of positive alerts over one week) in young adults was within the 28.3–58.6% range considering the sum of tooth contact, teeth clenching, teeth grinding, mandible bracing frequency. In detail, the seven studies that used the same smartphone-based app (BruxApp®, WMA Srl., Florence, Italy) reported an AB frequency range between 28.3 and 40% [8,10,12,13,14,16,19], while another investigation adopted a different smartphone-based EMA approach via WhatsApp using a web-based survey program called Mentimeter® and reported an AB frequency of 58.6% (Table 2, Figure 2A–E and Figure 3A–E) [18].

Table 2.

Mean values of the frequency data (percentage of positive answers for the different AB behaviors over the 7-day observation period)—comparison among studies.

| Bracci et al., 2018 [8] | Zani et al., 2019 T1 [10] | Zani et al., 2019 T2 [10] | Pereira NC et al., 2020 [18] | Câmara-Souza et al., 2020 [13] | Zani et al., 2021 [14] | Dias et al., 2021 T1 [12] | Dias et al., 2021 T2 [12] | Dias et al., 2021 T3 [12] | Emodi-Perlman et al., 2021 [16] | Bucci et al., 2022 [19] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 46 | N = 30 | N = 30 | N = 38 | N = 69 | N = 153 | N = 31 | N = 31 | N = 31 | N = 106 | N = 151 | |

| Activity | Mean frequency | Mean frequency | Mean frequency | Mean frequency | Mean frequency | Mean frequency | Mean frequency | Mean frequency | Mean frequency | Mean frequency | Mean frequency |

| Relaxed jaw muscles | 71.7 | 62 | 74 | 41.4 | 61,6 | 76.4 | 62.5 | 67.8 | 69.0 | 59.7 | 62.5 |

| Teeth contact | 14.5 | 20 | 11 | 40.9 | 18.6 | 13.6 | 19.1 | 16.2 | 14.7 | 20.2 | 18.8 |

| Mandible bracing | 10.0 | 14 | 13 | 5.9 | 13.1 | 7.0 | 17.2 | 16.9 | 15.8 | 13.7 | 14.3 |

| Teeth clenching | 3.7 | 3 | 2 | 11.2 | 5.9 | 2.5 | 4.9 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 5.7 | 3.6 |

| Teeth grinding | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Gender differences | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | /// | /// | /// | No | /// |

Figure 2.

(A–E) Mean values distribution of the frequency data and confidence interval for AB behaviors (e.g., relaxed jaw muscles, teeth contact, teeth clenching, teeth grinding, mandible bracing)—comparison among studies [8,10,12,13,14,16,18,19].

Figure 3.

(A–E) Reported frequency data of AB behaviors (e.g., relaxed jaw muscles, teeth contact, teeth clenching, teeth grinding, mandible bracing).

Among the different AB behaviors, teeth contact appeared to be the most common behavior. Report of teeth grinding was almost absent, as shown in Table 2, Figure 2A–E and Figure 3A–E.

4. Discussion

A major concern for current bruxism knowledge is the paucity of literature data on the epidemiology of awake bruxism with respect to sleep bruxism [2]. A common suggestion from several reviews is that an improvement of such knowledge would be helpful to clarify its clinical relevance [26,28,29,30,31].

Considering that bruxism is a masticatory muscle activity, the recommended strategy is to have electromyographic recordings of the jaw muscles during wakefulness. Nonetheless, performing an hour-long EMG recording of jaw muscle activity during wakefulness is difficult due to potentially poor patient compliance, as well as for technical reasons [1,2]. Consequently, to date, the information on AB prevalence is mainly based on retrospective self-reported data collections at a single observation point, with questionnaire approaches adopted in both clinical and research settings. Such a strategy requires an individual to recollect the frequency of a habit over the timespan covered by the report, thus representing a potential risk of bias. In addition, the intensity and duration of specific masticatory muscle activities cannot be quantified via a self-report [1]. It is also interesting to note that, currently, there are no universally adopted questionnaires for the assessment of AB [20]. The most frequent approach provides the use of AB items included in history using instruments that were designed for broader scopes, such as the report of temporomandibular disorders (e.g., Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) [32], oral behaviors (e.g., Oral Behaviors Checklist) [33] and bruxism in general (e.g., Bruxscale) [34].

As recently suggested by several studies [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] and by the expert consensus papers on bruxism definition [1,3], these limitations may be overcome by adopting EMA strategies, which are based on the report of a condition in real time. Such an approach is not a novelty in the field of psychological sciences [23] and has gained popularity also in medical science [35,36,37]. The application of the EMA principles to the study of AB has emerged as an interesting assessment option, since it is a simple method to collect real-time data in the natural environment. The EMA approach may be optimized with the use of smartphone apps, which are easy to use and intuitive [38,39]. The smartphone-based EMA approach is carried out in the natural setting and may be prolonged for several days, thus offering a potential advantage in terms of ecological validity, even compared with hour-long EMG recordings during wakefulness. In detail, it allows for the real-time collection of self-report data on the momentary presence of different oral conditions (e.g., relaxed jaw muscles, tooth contact, teeth clenching, teeth grinding, mandible bracing) that are related to the spectrum of AB activities. This approach allows monitoring AB behaviors over time and testing for potential Ecological Momentary (EMI) Intervention effects.

In this view, it is important to summarize the current knowledge on AB to provide a basis for comparison as well as possible suggestions for future studies. Based on that, a literature review was executed to report on AB prevalence data gathered via smartphone-based EMA technology.

Only eight papers met the inclusion criteria [8,10,12,13,14,16,18,19]. A major concern emerging from the literature overview is that many studies dealing with the EMA assessment of AB demonstrated a potentially poor external validity of their findings. Many studies were performed in convenience samples of non-representative populations, which is the main reason for our decision to avoid any qualitative and quantitative assessment of the findings. In fact, most investigations were performed on a study sample recruited exclusively from university students [8,10,12,13,14,16], with the exception of Pereira et al. [18] and Bucci et al. [19] studies. It is also important to point out that the studies that met the inclusion criteria originated from the same group of researchers, with some variations. Such flaws may affect the external validity of the findings and the consistency of the prevalence data across the studies. From a methodological viewpoint, taking into account the above considerations, the findings of the present review should be interpreted with caution and be viewed as a narrative standpoint for future comparisons.

In general, the papers included in the final review [8,10,12,13,14,16,18,19] reported an average AB frequency behavior over a one-week period within the range of 23.6–58.6% for otherwise healthy young adults. Nonetheless, it is important to underline that all studies, except Pereira et al.’s [18], used the same study protocol, and the prevalence of AB among these articles was much more consistent, varying from 23.6% to 40.3%. In the study by Pereira et al. [18], which instead used a different method based on WhatsApp messages, the prevalence of AB behaviors was higher (58.6%). In fact, all but one study [8,10,12,13,14,16,19] used the same dedicated smartphone application, which sends alerts at randomly during the day to collect data on self-reported AB. In this case, the subjects must answer (i.e., EMA) by tapping on the display icon that corresponds to the current condition of his/her jaw muscles: relaxed jaw muscles; teeth contact; teeth clenching; teeth grinding; mandible bracing (i.e., jaw clenching without teeth contact). On the other hand, Pereira et al. [18] used a web-based survey program called Mentimeter®. For this program the possible responses are as follows: (a) I am not touching my teeth; (b) I am not touching my teeth, but I feel my muscles are contracted; (c) I am slightly touching my teeth; (d) I am clenching my teeth; or (e) I am grinding my teeth. It is interesting to note how the relaxed jaw muscle condition is absent amongst the potential options. This between-study difference could explain the higher percentage of AB behaviors compared to the other studies, in addition to other potential explanations concerning differences in the socio-cultural aspects of the study populations.

In all studies, the subject answered to an alert, i.e., EMA, by tapping on the smartphone display within 5 min. The monitoring period was 7 consecutive days for all studies, but the investigation by Pereira et al. [18] was based on 10 alerts/day instead of the 20 alerts at random intervals used in the other studies. It is important to point out that the exclusion of subjects with signs or symptoms of TMD or other painful chronic disorders based on the recommendations of the Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (DC/TMD) [32] is a common feature of all studies.

It is interesting to note that, among the different AB behaviors, teeth contact was the most frequently reported behavior in all studies, whilst teeth clenching was much less frequently reported than commonly believed, and the report of teeth grinding was almost absent. Concerning sex differences, four studies examined this aspect and did not find any consistent pattern for the differences between AB prevalence in males and females. On the other hand, Zani et al. [14] found that the mean of the relaxed jaw muscles condition was higher in males than in females. Câmara-Souza et al. [13] underlined that significantly higher AB values were found in females, who had approximately 1.5 times more AB episodes than males. In general, these findings point towards a potentially higher report of AB in females.

Given that the data collection span covered one week, a potential EMI (Ecological Momentary Intervention) effect may also be considered. This is demonstrated by the fact that the use of the application over time leads to a decrease in AB behaviors, as highlighted by Zani et al. and Dias et al. [12,14]. The authors adopted a study design with multiple monitoring weeks and noticed that the percentage of AB reports went down from 38% to 26% and from 37.5% to 31%, respectively. This may also suggest potentially therapeutic opportunities. EMI based on the biofeedback mechanism has already been used effectively in people who show potentially dangerous behaviors as a strategy to recognize and modify them [10,40]. The use of technology has introduced a new possible way for clinicians to engage patients from a therapeutic viewpoint, which may be adopted for AB as well, when required. In this scenario, myofascial pain patients with anxiety personality and stress sensitivity are theoretically the ideal target for the app-based EMI approach, due to the potential influence on emotion-related mandible bracing [10].

Future epidemiological studies should carefully avoid the selection of non-representative populations and recruit large study samples. On the other hand, it is fundamental that future investigations are based on carefully organized and standardized training sessions addressing the issue of patients’ comprehension, as suggested by Nykänen et al. [17]. Indeed, poor patients’ compliance and comprehension, along with the presenting clinician’s untrained skills, may represent methodological flaws and sources of bias hampering the generalization of the findings.

Concerning the above, the current body of evidence is of low quality because it is mainly based on a single smartphone application to record a real-time report on AB behaviors, and therefore generalization will only be possible in the future with the use of different EMA methods and the involvement of as many other investigators as possible.

The findings presented in this review could be seen as a reference point for future investigations on the epidemiological features of AB. Future EMA research on the frequency of AB activities in healthy individuals and on their additive frequency in selected populations with comorbid conditions (e.g., psychological and social impairment, orofacial pain, sleep disorders) may contribute to a better understanding of this complex topic. The EMA approach—which is also called experience sampling methodology (ESM)—might be used in association with other strategies, as suggested in the STAB [6]. A combination of the different approaches may represent the best possible strategy to overcome the limitations of the different stand-alone approaches.

5. Conclusions

The present review assessed the literature on the report of data on awake bruxism behaviors gathered via smartphone-based EMA technology. The reviewed articles have some methodological limits, such as convenience samples and a limited age range. As part of this literature review, some suggestions to improve the standardization of data collection are presented, based on the current bruxism construct and the proposals by the international expert panel that worked on the Standardized Tool for the Assessment of Bruxism.

The results of seven studies using the same smartphone-based app reported a frequency of AB behaviors in the range between 28.3 and 40% over one week, while another investigation adopted a different smartphone-based EMA approach via WhatsApp using a web-based survey program and reported an AB frequency of 58.6%.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—D.M., A.C. and A.B.; writing original draft—A.C. and D.M.; review and editing of the draft with multiple rounds of comments—A.B., J.A., M.B.C.-S., R.B., P.C.R.C., R.D., A.E.-P., R.F., B.H.-H., A.M., L.N., N.S., E.W. and F.L.; supervision of final draft—D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

A.B. ideated the BruxApp software. A.C., J.A., M.B.C.-S., R.B., P.C.R.C., R.D., A.E.-P., R.F., B.H.-H., A.M., L.N., N.S., E.W., F.L. and D.M. do not have any conflict of interest concerning this investigation.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Lobbezoo F., Ahlberg J., Wetselaar P., Glaros A.G., Kato T., Santiago V., Winocur E., De Laat A., De Leeuw R., Koyano K., et al. International consensus on the assessment of bruxism: Report of a work in progress. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018;45:837–844. doi: 10.1111/joor.12663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manfredini D., Colonna A., Bracci A., Lobbezoo F. Bruxism: A summary of current knowledge on aetiology, assessment and management. Oral Surg. 2019;13:358–370. doi: 10.1111/ors.12454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lobbezoo F., Ahlberg J., Glaros A.G., Kato T., Koyano K., Lavigne G.J., de Leeuw R., Manfredini D., Svensson P., Winocur E. Bruxism defined and graded: An international consensus. J. Oral Rehabil. 2013;40:2–4. doi: 10.1111/joor.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manfredini D., Winocur E., Guarda-Nardini L., Paesani D., Lobbezoo F. Epidemiology of bruxism in adults: A systematic review of literature. J. Orofac. Pain. 2013;27:99–110. doi: 10.11607/jop.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahlberg J., Piirtola M., Lobbezoo F., Manfredini D., Korhonen T., Aarab G., Hublin C., Kaprio J. Correlates and genetics of self-reported sleep and awake bruxism in a nationwide twin cohort. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020;47:1110–1119. doi: 10.1111/joor.13042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manfredini D., Ahlberg J., Aarab G., Bracci A., Durham J., Ettlin D., Gallo L.M., Koutris M., Wetselaar P., Svensson P., et al. Towards a standardised tool for the assessment of bruxism (STAB)—Overview and general remarks of a multidimensional bruxism evaluation system. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020;47:549–556. doi: 10.1111/joor.12938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manfredini D., Bracci A., Djukic G. BruxApp: The ecological momentary assessment of awake bruxism. Minerva Stomatol. 2016;65:252–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bracci A., Djukic G., Favero L., Salmaso L., Guarda-Nardini L., Manfredini D. Frequency of awake bruxism behaviors in the natural environment. A seven day, multiple-point observation of real time report in healthy young adults. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018;45:423–429. doi: 10.1111/joor.12627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colonna A., Lombardo L., Siciliani G., Bracci A., Guarda-Nardini L., Djukic G., Manfredini D. Smartphone-based application for EMA assessment of awake bruxism: Compliance evaluation in a sample of healthy young adults. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020;24:1395–1400. doi: 10.1007/s00784-019-03098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zani A., Lobbezoo F., Bracci A., Ahlberg J., Manfredini D. Ecological Momentary Assessment and Intervention principles for the study of awake bruxism behaviors, part 1: General principles and preliminary data on healthy young Italian adults. Front. Neurol. 2019;10:169. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emodi-Perlman A., Manfredini D., Shalev T., Yevdayev I., Frideman-Rubin P., Bracci A., Arnias-Winocur O., Eli I. Awake Bruxism-Single-Point Self-Report versus Ecological Momentary Assessment. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10:1699. doi: 10.3390/jcm10081699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dias R., Vaz R., Rodrigues M.J., Serra-Negra J.M., Bracci A., Manfredini D. Utility of Smartphone-based real-time report (Ecological Momentary Assessment) in the assessment and monitoring of awake bruxism: A multiple-week interval study in a Portuguese population of university students. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021;48:1307–1313. doi: 10.1111/joor.13259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Câmara-Souza M.B., Carvalho A.G., Figueredo O.M.C., Bracci A., Manfredini D., Rodrigues Garcia R.C.M. Awake bruxism frequency and psychosocial factors in college preparatory students. Cranio. 2020;14:1–7. doi: 10.1080/08869634.2020.1829289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zani A., Lobbezoo F., Bracci A., Djukic G., Guarda-Nardini L., Favero R., Ferrari M., Aarab G., Manfredini D. Smartphonebased evaluation of awake bruxism behaviours in a sample of healthy young adults: Findings from two University centres. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021;48:989–995. doi: 10.1111/joor.13212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osiewicz M.A., Lobbezoo F., Bracci A., Ahlberg J., Pytko-Polończyk J., Manfredini D. Ecological Momentary Assessment and Intervention Principles for the Study of Awake Bruxism Behaviors, Part 2: Development of a Smartphone Application for a Multicenter Investigation and Chronological Translation for the Polish Version. Front. Neurol. 2019;10:170. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emodi-Perlman A., Manfredini D., Shalev T., Bracci A., Frideman-Rubin P., Eli I. Psychosocial and Behavioral Factors in Awake Bruxism-Self-Report versus Ecological Momentary Assessment. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10:4447. doi: 10.3390/jcm10194447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nykänen L., Manfredini D., Lobbezoo F., Kämppi A., Colonna A., Zani A., Almeida A.M., Emodi-Perlman A., Savolainen A., Bracci A., et al. Ecological Momentary Assessment of Awake Bruxism with a Smartphone Application Requires Prior Patient Instruction for Enhanced Terminology Comprehension: A Multi-Center Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11:3444. doi: 10.3390/jcm11123444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira N.C., Oltramari P.V.P., Conti P.C.R., Bonjardim L.R., de Almeida-Pedrin R.R., Fernandes T.M.F., de Almeida M.R., Conti A.C.C.F. Frequency of awake bruxism behaviour in orthodontic patients: Randomised clinical trial: Awake bruxism behaviour in orthodontic patients. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021;48:422–429. doi: 10.1111/joor.13130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bucci R., Manfredini D., Lenci F., Simeon V., Bracci A., Michelotti A. Comparison between Ecological Momentary Assessment and Questionnaire for the Assessment of Frequency of Waking-Time Non-Functional Oral Behaviours. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11:5880. doi: 10.3390/jcm11195880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bracci A., Lobbezoo F., Häggman-Henrikson B., Colonna A., Nykänen L., Pollis M., Ahlberg J., Manfredini D., International Network for Orofacial Pain and Related Disorders Methodology INfORM Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives on Awake Bruxism Assessment: Expert Consensus Recommendations. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11:5083. doi: 10.3390/jcm11175083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiffman S., Stone A.A., Hufford M.R. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Runyan J.D., Steinke E.G. Virtues, ecological momentary assessment/intervention and smartphone technology. Front. Psychol. 2015;6:481. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glaros A.G., Williams K., Lausten L., Friesen L.R. Tooth contact in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Cranio. 2005;23:188–193. doi: 10.1179/crn.2005.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen C.Y., Palla S., Erni S., Sieber M., Gallo L.M. Nonfunctional tooth contact in healthy controls and patients with myogenous facial pain. J. Orofac. Pain. 2007;21:185–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manfredini D., Ahlberg J., Wetselaar P., Svensson P., Lobbezoo F. The bruxism construct: From cut-off points to a continuum spectrum. J. Oral Rehabil. 2019;46:991–997. doi: 10.1111/joor.12833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manfredini D., Lobbezoo F. Role of psychosocial factors in the etiology of bruxism. J. Orofac. Pain. 2009;23:153–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poluha R.L., Canales G.T., Bonjardim L.R., Conti P.C.R. Oral behaviors, bruxism, malocclusion and painful temporomandibular joint clicking: Is there an association? Braz. Oral Res. 2021;35:e090. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2021.vol35.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svensson P., Jadidi F., Arima T., Baad-Hansen L., Sessle B.J. Relationships between craniofacial pain and bruxism. J. Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:524–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2008.01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manfredini D., Lobbezoo F. Relationship between bruxism and temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review of literature from 1998 to 2008. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2010;109:e26–e50. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Restrepo C., Gomez S., Manrique R. Treatment of bruxism in children: A systematic review. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:849–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lobbezoo F., Ahlberg J., Manfredini D., Winocur E. Are bruxism and the bite casually related? J. Oral Rehabil. 2012;39:489–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2012.02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schiffman E., Ohrbach R., Truelove E., Look J., Anderson G., Goulet J.P., International RDC/TMD Consortium Network. International association for Dental Research. Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. International Association for the Study of Pain et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014;28:6–27. doi: 10.11607/jop.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markiewicz M.R., Ohrbach R., McCall W.D. Oral behaviors checklist: Reliability of performance in targeted waking-state behaviors. J. Orofac. Pain. 2006;20:306–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van der Meulen M.J., Lobbezoo F., Aartman I.H., Naeije M. Self-reported oral parafunctions and pain intensity in temporomandibular disorder patients. J. Orofac. Pain. 2006;20:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Timmer B.H.B., Hickson L., Launer S. The use of ecological momentary assessment in hearing research and future clinical applications. Hear. Res. 2018;369:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell M.A., Gajos J.M. Annual Research Review: Ecological momentary assessment studies in child psychology and psychiatry. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2020;61:376–394. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yim S.J., Lui L.M., Lee Y., Rosenblat J.D., Ragguett R.-M., Park C., Subramaniapillai M., Cao B., Zhou A., Rong C., et al. The utility of smartphone-based, ecological momentary assessment for depressive symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;274:602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raento M., Oulasvirta A., Eagle N. Smartphones: An emerging tool for social scientist. Sociol. Methods Res. 2009;37:426–454. doi: 10.1177/0049124108330005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Runjan J.D., Steenbergh T.A., Bainbridge C., Daugherty D.A., Oke L., Fry B.N. A smartphone ecological momentary assessment/intervention Bapp^ for collecting real-time data and promoting selfawareness. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bylsma L.M., Taylor-Clift A., Rottenberg J. Emotional reactivity to daily events in major and minor depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011;120:155–167. doi: 10.1037/a0021662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.