Abstract

In the present study we completed the nucleotide sequence of a Brucella melitensis 16M DNA fragment deleted from B. abortus that accounts for 25,064 bp and show that the other Brucella spp. contain the entire 25-kb DNA fragment. Two short direct repeats of four nucleotides, detected in the B. melitensis 16M DNA flanking both sides of the fragment deleted from B. abortus, might have been involved in the deletion formation by a strand slippage mechanism during replication. In addition to omp31, coding for an immunogenic protein located in the Brucella outer membrane, 22 hypothetical genes were identified. Most of the proteins that would be encoded by these genes show significant homology with proteins involved in the biosynthesis of polysacharides from other bacteria, suggesting that they might be involved in the synthesis of a Brucella polysaccharide that would be a heteropolymer synthesized by a Wzy-dependent pathway. This polysaccharide would not be synthesized in B. abortus and would be a polysaccharide not identified until present in the genus Brucella, since all of the known polysaccharides are synthesized in all smooth Brucella species. Discovery of a novel polysaccharide not synthesized in B. abortus might be interesting for a better understanding of the pathogenicity and host preference differences observed between the Brucella species. However, the possibility that the genes detected in the DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus no longer lead to the synthesis of a polysaccharide must not be excluded. They might be a remnant of the common ancestor of the alpha-2 subdivision of the class Proteobacteria, with some of its members synthesizing extracellular polysaccharides and, as Brucella spp., living in association with eukaryotic cells.

The genus Brucella is described as constituted by six species: Brucella melitensis, B. abortus, B. suis, B. ovis, B. canis, and B. neotomae, each preferentially infecting an animal host. In addition, several biovars are included in the species B. melitensis, B. abortus, and B. suis. The six Brucella species and their biovars are currently differentiated by pathogenicity and host preference characteristics, serotyping, phage typing, dye sensitivities, and culture and metabolic properties (2). In spite of the high degree of DNA homology that has been found between the six species, which would justify a monospecific genus (53, 54), the classical organization of the genus Brucella has been maintained since it is in accordance with the pathogenicity and host preference characteristics of each species, and several molecular markers, allowing the differentiation between the six species and some of their biovars, have been found (55).

Differences in pathogenicity and host preference found between the Brucella species and biovars could be reflected by differences at the DNA level. However, only small differences have been found between the Brucella species in the genes identified until the present (55). Small deletions in several genes have been detected in some Brucella species (11, 13, 17, 44), sometimes leading to the lack of production of the encoded protein (44), and the lack of expression of an existing gene has also been reported (16, 29). DNA deletions of several sizes and DNA inversions have also been described, but they have not been characterized (35). The first report of a gene absent in one of the Brucella species describes the deletion in B. abortus of omp31 coding for an outer membrane protein (OMP) (58). Further studies revealed that the deletion in B. abortus comprises not only omp31 but also several adjacent genes located at both sides of omp31 (57, 58). Partial characterization of this large DNA region deleted in B. abortus led to the discovery of several genes that might be involved in the synthesis of a polysaccharide not identified in Brucella spp. (57). In the present study, we describe the characterization of the entire B. melitensis 16M large DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus, and we evaluate its occurrence in the other Brucella species and biovars.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The Brucella strains used in this study were obtained from the INRA Brucella Culture Collection, Nouzilly (BCCN), France. Bacteria were grown on tryptic soy agar (Gibco-BRL/Life Technologies, Eragny, France) supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) yeast extract (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). For fastidious strains (B. abortus bv. 2 and B. ovis), 5% horse serum (Gibco-BRL) was also added. Species and biovar characterizations were performed by standard procedures (2).

Escherichia coli JM109 cells bearing the recombinant plasmids used in this study were cultured overnight on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing 50 μg of ampicillin ml−1. E. coli KW251 was cultured on LB supplemented with 15 μg of tetracycline ml−1 and 10 mM MgSO4.

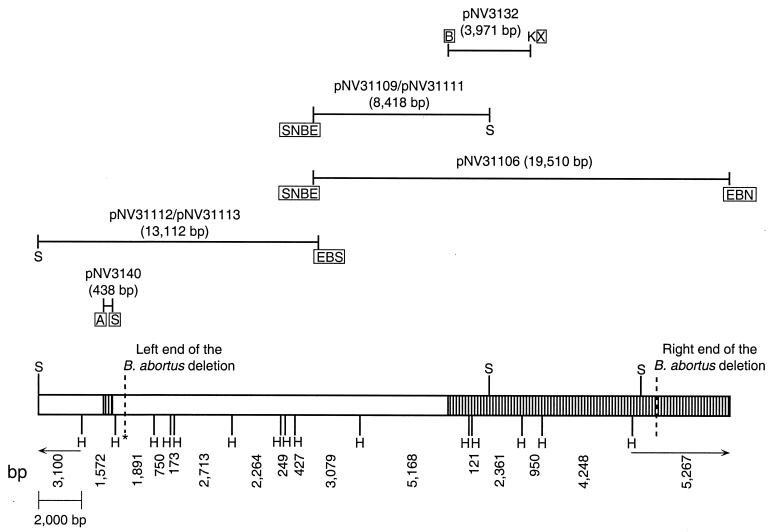

Plasmids pNV3132 and pNV3140 were obtained as described previously (57). The insert of pNV3132, cloned in pGEM-7Zf (Promega, Madison, Wis.), corresponds to the left end of a 17,119-bp B. melitensis 16M DNA fragment previously identified (57) and is part of a large fragment deleted in B. abortus strains (57) (Fig. 1). Plasmid pNV3140 contains a 438-bp DNA fragment from B. melitensis 16M that had been PCR amplified and cloned in pGEM-T (Promega) as described previously (57). This 438-bp DNA fragment is present in both B. melitensis and B. abortus and is close to the left end of the large B. abortus deletion (57) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

B. melitensis 16M DNA inserts of the relevant plasmids used in this study. pNV3132 and pNV3140 were constructed as described previously (57). The insert of pNV31106 is cloned into the NotI site of pGEM-5Zf. The inserts of pNV31109, pNV31111, pNV31112, and pNV31113 are cloned into the SacI site of pGEM-7Zf. Their HindIII and SacI restriction profiles are shown in the B. melitensis 16M DNA fragment drawn in the bottom of the figure, where the limits of the DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus are also shown. The B. melitensis 16M DNA regions previously characterized (57) are patterned. Restriction sites: B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; N, NotI; S, SacI; X, XbaI. The framed restriction sites are not present in the B. melitensis 16M DNA, and they belong to the multiple cloning site of λ-GEM12 or cloning plasmids.

pNV31106 (Fig. 1) was obtained by subcloning, into the NotI site of pGEM-5Zf (Promega), the NotI DNA insert of a recombinant phage from a B. melitensis 16M genomic library constructed in λGEM-12 XhoI half-site arms (Promega) as described previously (56). Plasmids pNV31109 and pNV31111 were obtained by subcloning, into the SacI site of pGEM-7Zf (Promega), the left SacI fragment of the pNV3106 insert (Fig. 1). Both plasmids contain the same B. melitensis 16M DNA insert but in opposite orientations in relation to lacZ.

Plasmids pNV31112 and pNV31113 (Fig. 1) were obtained by subcloning, into the SacI site of pGEM-7Zf, the right SacI fragment of the B. melitensis 16M DNA insert of plasmid pNV31110. Plasmid pNV31110 had been obtained by subcloning, into the BamHI site of pGEM-7Zf, the insert of another phage from the B. melitensis 16M genomic library. The pNV31112 and pNV31113 inserts are identical, but they are cloned in opposite orientations in relation to lacZ.

Genomic library screening and Southern blot hybridization.

The B. melitensis 16M inserts of pNV3132 and pNV3140 were excised by digestion of the plasmids with BamHI and XbaI and with ApaI and SacI, respectively. Both inserts were purified, with the Geneclean II kit (Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.), from an agarose gel after electrophoresis and digoxigenin labeled with the DIG DNA Labeling Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

For screening of the B. melitensis 16M genomic library, constructed in λGEM-12 XhoI half-site arms (Promega) as described previously (56), E. coli KW251 cells were incubated with the recombinant phages, spread, and grown in LB-tetracycline plates as previously described (56). Plaques were overlaid with a nylon disk (Roche Diagnostics) for 10 min and tested for hybridization at 68°C with the digoxigenin-labeled pNV3132 or pNV3140 inserts as probes. Detection of hybridization was performed with the DIG Nucleic Acid Detection Kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Positive plaques were removed from the plates, and the phages were eluted in SM buffer (0.01% gelatin, 100 mM NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]). The global procedure was repeated until all plaques were positive to ensure the purity of each positive phage.

For Southern blot hybridization, DNA was extracted from Brucella strains (57) and digested with HindIII. Restriction fragments were resolved by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis and then transferred, by capillarity with 0.4 M NaOH, onto a nylon membrane (Roche Diagnostics). Plasmids pNV31106 and pNV31112, labeled with digoxigenin as described above, were used as probes for hybridization at 68°C with the HindIII Brucella spp. DNA fragments. DNA markers III and VI (Roche Diagnostics) were used as molecular weight standards and were hybridized with probes constituted by the same markers labeled with digoxigenin. Detection of hybridization was performed with the DIG Nucleic Acid Detection Kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

PCR and DNA sequencing.

Insert DNA from plasmids pNV31112 and pNV31113 (Fig. 1) was unidirectionally digested with exonuclease III by using the Erase-a-Base system (Promega) as specified by the manufacturer. A series of plasmids differing in ca. 400 bp was obtained for each initial plasmid and used to determine the entire sequence of both strands of the 13,112-bp insert. Plasmid DNA was obtained and purified by using the Wizard Plus SV Minipreps System (Promega) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Purified plasmid DNA was sequenced by primer-directed dideoxy sequencing (45) with an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) and the forward pUC19 primer. Some specific Brucella DNA primers were also used to complete the sequence. The same procedure was followed for sequencing both strands of the 8,418-bp insert of pNV31109 and pNV31111 (Fig. 1).

PCR was performed with the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche Diagnostics) according to the instructions of the manufacturer, by using 100 ng of Brucella spp. DNA template, extracted as previously described (57), and 2 μM concentrations of each primer. Cycling conditions were those described previously (57). Primers for amplification of part of the bme19 gene in Brucella spp. were Bme19-1 (5′-TTC CCT TTT GCC GCT CTG-3′) and Bme19-2 (5′-CGC TTC AGT TCG TCG CAA-3′) that were designed according to the bme19 sequence of B. melitensis 16M determined in this work. PCR-amplified products were electrophoresed through a 0.8% agarose gel and purified from the gel with the Geneclean II kit. The purified amplification products were sequenced with the Bme19-1 and Bme19-2 primers.

DNA and protein analysis.

Search for open reading frames (ORFs) and putative genes in the DNA sequences was performed with the DNAStrider 1.2 program (32) and the GeneMark.fbf prediction program (47) (Website, http://dixie.biology.gatech.edu/GeneMark/fbf.cgi), respectively. Searches for DNA and protein homologies were performed with the FASTA program (39) (FASTA Website, http://www.infobiogen.fr/services/analyseq/cgi-bin/fasta_in.pl; version 2, June 2000). Cellular location and PROSITE motifs of the predicted proteins were determined with the PSORT (37) (Website, http://psort.nibb.ac.jp/form.html) and MOTIF programs (30) (Website, http://www.motif.genome.ad.jp/), respectively.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The B. melitensis 16M nucleotide sequence determined here has been deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ databases under accession number AF076290.

RESULTS

DNA sequence of the B. melitensis 16M DNA fragments cloned in pNV31112/pNV31113 and pNV31109/pNV31111.

A B. melitensis 16M DNA fragment of 17,119 bp, cloned in pGEM-7Zf giving recombinant plasmid pNV3103, was sequenced in a previous study (57). This fragment contained 9,948 bp corresponding to the right side of a large deletion detected in B. abortus strains (57). However, the left end of the B. abortus deleted fragment could not be determined. In order to completely characterize the B. abortus deletion, two B. melitensis 16M DNA fragments were used as probes to screen a B. melitensis 16M genomic library. The first B. melitensis 16M DNA fragment, which was cloned in pGEM-7Zf resulting in recombinant pNV3132 plasmid, is composed of 3,971 bp located at the left end of the previously sequenced pNV3103 insert (57) (Fig. 1). The second B. melitensis 16M DNA fragment, which was cloned in pGEM-T resulting in recombinant pNV3140 plasmid, corresponds to 438 bp known to be located adjacent to the left end of the fragment deleted in B. abortus (57) (Fig. 1). Screening of a B. melitensis 16M genomic library by using the pNV3132 and pNV3140 inserts as digoxigenin-labeled probes allowed us to select two recombinant phages containing overlapping inserts hybridizing with pNV3132 and pNV3140, respectively. Subcloning of the B. melitensis 16M DNA insert of these phages, as described in Materials and Methods, allowed us to obtain plasmids pNV31109/pNV31111 and pNV31112/pNV31113 (Fig. 1), which were used to determine the nucleotide sequence of the left end of the fragment missing in B. abortus.

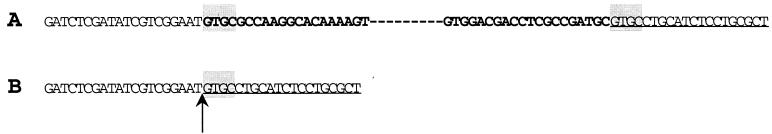

In the present work we have identified 19,383 bp from the B. melitensis 16M genome, of which 4,267 bp correspond to DNA adjacent to the left end of the fragment missing in B. abortus and 15,116 bp correspond to the left end of the fragment deleted in B. abortus (Fig. 1). Analysis of the nucleotide sequence has allowed us to determine that the whole fragment deleted in B. abortus accounts for 25,064 bp. Searching for a possible explanation for how the deletion occurred in B. abortus, the B. melitensis 16M nucleotide sequence flanking both sides of the B. abortus deletion was compared with the corresponding B. abortus sequence (Fig. 2). Two direct repeats of four nucleotides (GTGC) were detected in B. melitensis 16M at both sides of the fragment deleted in B. abortus (Fig. 2). These direct repeats might have been involved in the deletion formation in B. abortus since only one of the repeated sequences is found in this species (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the B. melitensis 16M DNA flanking the 25-kb fragment deleted in B. abortus (A) and of the corresponding region in B. abortus 544 (B). The B. abortus sequence was determined in a previous work (57). The direct repeats of four nucleotides found at both sides of the B. melitensis 16M DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus are shaded. The point where the deletion occurred is marked with an arrow in B. abortus, and the DNA flanking the right side of the deletion is underlined in B. melitensis and B. abortus.

Putative genes and encoded proteins identified in the B. melitensis 16M DNA fragments cloned in pNV31112/pNV31113 and pNV31109/pNV31111.

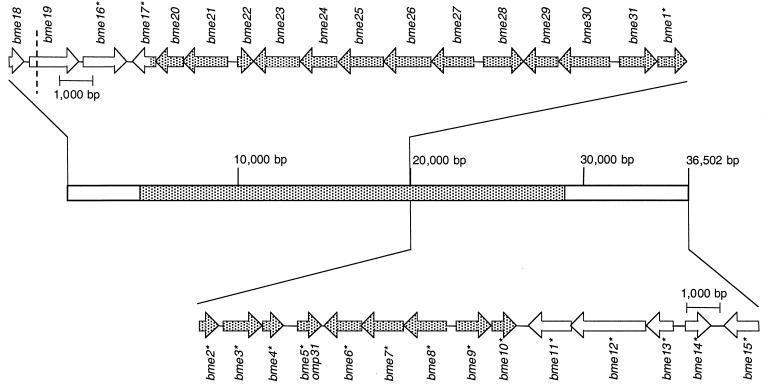

Sequencing of the B. melitensis 16M DNA cloned in plasmids pNV31112/pNV31113 and pNV31109/pNV31111 has allowed us to identify 17 new putative genes potentially encoding proteins (Fig. 3; Tables 1 and 2). Three of these genes (bme16, bme17, and bme1) had been partially sequenced previously in B. melitensis 16M and/or B. abortus 544 (57). Putative genes were identified with GeneMark.fbf and sequence comparison, with FASTA, of the encoded proteins with other proteins in the database.

FIG. 3.

ORF distribution of the B. melitensis 16M DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus and flanking DNA. The patterned area shows the DNA deleted in B. abortus. Genes identified in a previous study (57) are marked with an asterisk. The extension of bme19 is shown as determined by sequence homology of the encoded protein with other proteins in the database. However, a stop codon (marked with a dashed line) is detected in the reference strains of B. abortus and the three biovars of B. melitensis, but it is not detected in the other Brucella reference strains (see Results).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of proteins deduced from the putative genes found in B. melitensis 16M DNA inserts of plasmids pNV31112 and pNV31109a

| Protein | Starting nucleotide (putative start codon) | Ending nucleotide | Transcription strand | No. of amino acids | Size (kDa) | Cellularb localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bme18c | 459 | Direct | ||||

| Bme19d | 586 (ATG) and 970 (CTG) | 2082 | Direct | 498 and 370 | 54.6 and 40.3 | C |

| Bme16e | 2199 (ATG) | 3479 | Direct | 426 | 43.7 | CM |

| Bme17e | 4331 (ATG) | 3675 | Reverse | 218 | 24.9 | C |

| Bme20 | 5137 (ATG) | 4328 | Reverse | 269 | 31.0 | CM |

| Bme21 | 6441 (ATG) | 5140 | Reverse | 433 | 49.1 | C |

| Bme22 | 6731 (ATG) | 7285 | Direct | 184 | 21.1 | C |

| Bme23 | 8561 (ATG) | 7248 | Reverse | 437 | 48.7 | C |

| Bme24 | 9661 (ATG) | 8600 | Reverse | 353 | 38.9 | CM |

| Bme25 | 11116 (ATG) | 9782 | Reverse | 444 | 48.3 | P |

| Bme26 | 12456 (ATG) | 11095 | Reverse | 453 | 49.2 | C |

| Bme27 | 13723 (ATG) | 12494 | Reverse | 409 | 45.5 | C |

| Bme28 | 13990 (ATG) | 15231 | Direct | 413 | 45.2 | CM |

| Bme29 | 16200 (ATG) | 15187 | Reverse | 337 | 37.5 | C |

| Bme30 | 17709 (ATG) | 16216 | Reverse | 497 | 53.6 | CM |

| Bme31 | 18002 (ATG) | 19123 | Direct | 373 | 39.9 | CM |

| Bme1e | 19120 (ATG) | 20001 | Direct | 293 | 27.5 | OM or CM |

For pNV31109, only the putative genes not previously described (57) are shown.

The most probable cellular localization of each protein was determined with the PSORT program (http://psort.nibb.ac.jp/form.html). C, cytoplasm; CM, cytoplasmic membrane; OM, outer membrane; P, periplasm.

Only DNA encoding the C-terminal end of Bme18 was cloned in pNV31112. Therefore, the start position, number of amino acids, size, and cellular localization are not given for this protein.

A stop codon was found in the B. melitensis 16M bme19 nucleotide sequence at position 751, which might block the transduction of the hypothetical Bme19 protein. This stop codon was found in the B. abortus and the three B. melitensis biovars reference strains but not in the other Brucella species reference strains. Data for the two possible Brucella Bme19 proteins are shown.

Bme1, Bme16, and Bme17 partial coding sequences have been previously described in B. melitensis (Bme1 and Bme16) or B. abortus (Bme16 and Bme17) (57).

TABLE 2.

Most representative homologies of the B. melitensis 16M hypothetical proteins encoded by pNV31112 and pNV31109 to other proteinsa

| B. melitensis 16M protein | No. of aab | Similar proteins | Source | No. of aab | Proposed or determined function | % Identity (aa overlap)b | Expectation value | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bme18c | 152 | PA5030 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 438 | Probable transporter | 42.6 (136) | 3.0 × 10−15 | AE004916 |

| YnfM | Escherichia coli | 417 | Transport protein | 43.4 (129) | 1.2 × 10−13 | AE000255 | ||

| Bme19 | 498d | DR1928 | Deinococcus radiodurans | 501 | Glycerol kinase | 57.5 (489) | 1.6 × 10−111 | AE002031 |

| Riorf79 | Agrobacterium rhizogenes | 500 | Glycerol kinase | 58.4 (495) | 1.8 × 10−111 | AB039932 | ||

| Bme16 | 426 | PyrP | Escherichia coli | 442 | Uracil transport protein | 59.1 (421) | 2.1 × 10−83 | D90738 |

| UraA | Escherichia coli | 429 | Uracil permease | 37.9 (419) | 1.6 × 10−43 | X73586 | ||

| Bme17 | 218 | SCF62.20 | Streptomyces coelicolor | 215 | Unknown | 43.7 (208) | 1.5 × 10−29 | AL121855 |

| AAC14880 | Chlorobium trepidum | 240 | Unknown | 31.2 (157) | 4.9 × 10−6 | AF060080 | ||

| Bme20 | 269 | SCF62.19 | Streptomyces coelicolor | 269 | Glucose-1-phosphate cytidylyl transferase | 39.8 (254) | 2.8 × 10−38 | AL121855 |

| DdhA | Yersinia enterocolitica 0:8 | 261 | Glucose-1-phosphate cytidylyl transferase | 37.3 (257) | 2.6 × 10−32 | U46859 | ||

| Bme21 | 433 | SCF62.18 | Streptomyces coelicolor | 416 | Unknown | 48.0 (410) | 5.1 × 10−81 | AL121855 |

| BAA16904 | Synechocystis sp. | 433 | Unknown | 48.4 (417) | 2.3 × 10−79 | D90901 | ||

| Bme22 | 184 | StrX | Streptomyces glaucescens | 182 | NDP–4-ketohexose-3,5-epimerase | 45.2 (155) | 1.1 × 10−28 | AJ006985 |

| RfbC | Synechocystis sp. | 189 | dTDP–6-deoxymannose dehydrogenase | 47.4 (154) | 1.2 × 10−26 | D90901 | ||

| Bme23 | 437 | SCF62.22 | Streptomyces coelicolor | 424 | Unknown | 51.7 (420) | 6.3 × 10−93 | AL121855 |

| Cj1295 | Campylobacter jejuni | 435 | Unknown | 32.8 (430) | 6.6 × 10−45 | AL139078 | ||

| Bme24 | 353 | SCF62.21 | Streptomyces coelicolor | 341 | Epimerase-dehydratase | 49.6 (341) | 7.3 × 10−58 | AL121855 |

| StrP | Streptomyces glaucescens | 358 | Hydroxystreptomycin biosynthesis | 46.8 (342) | 1.3 × 10−52 | AJ006985 | ||

| Bme25 | 444 | Not found | ||||||

| Bme26 | 453 | SCF62.27 | Streptomyces coelicolor | 441 | Aminotransferase | 56.4 (427) | 7.8 × 10−90 | AL121855 |

| MxcL | Stigmatella aurantiaca | 420 | Aldehyde aminotransferase | 31.5 (410) | 9.1 × 10−26 | AF299336 | ||

| Bme27 | 409 | SCL2.15c | Streptomyces coelicolor | 387 | Sugar transferase | 31.4 (290) | 3.8 × 10−12 | AL137778 |

| MTH173 | Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum | 382 | LPS biosynthesis RfbU related protein | 25.9 (382) | 6.0 × 10−11 | AE000805 | ||

| Bme28 | 413 | SCF62.25 | Streptomyces coelicolor | 407 | Unknown | 37.4 (364) | 2.3 × 10−41 | AL121855 |

| Bme29 | 337 | LgtD | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | 337 | Glycosyl transferase | 26.3 (327) | 1.8 × 10−11 | U14554 |

| LgtA | Neisseria subflava | 348 | N-Acetylglucosamine transferase | 25.6 (332) | 9.1 × 10−11 | AF240672 | ||

| Bme30 | 497 | GumJ | Xylella fastidiosa | 510 | Unknown | 21.8 (477) | 7.9 × 10−15 | AE004046 |

| WzxC | Escherichia coli | 492 | Export protein | 22.5 (457) | 1.1 × 10−14 | U38473 | ||

| Bme31 | 373 | WecA | Escherichia coli | 367 | UndP–N-acetylhexosamine transferase | 35.9 (331) | 3.3 × 10−20 | AF248031 |

| Rfe | Salmonella typhimurium | 367 | UndP-GlcNAc transferase | 33.0 (342) | 5.0 × 10−20 | AF233324 | ||

| Bme1 | 293 | LgtF | Aquifex aeolicus | 251 | β-1,4-Glucosyltransferase | 31.8 (258) | 4.1 × 10−15 | AE000754 |

| WaaE | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 258 | Glucosyl transferase | 33.3 (264) | 1.0 × 10−14 | AF146532 |

Only the homologous proteins giving the two highest expectation values are shown, but in most cases other homologous proteins with the same function gave high scores.

aa, amino acid.

bme18 was not entirely cloned in pNV31112. Therefore, the number of amino acids shown in the table corresponds to the C-terminal domain of Bme18.

Homologies for Bme19 were searched considering that the bme19 ORF extended from nucleotides 586 to 2082 of the published sequence, ignoring a stop TAG codon found at nucleotide position 751. This stop codon was detected in the B. abortus and the three B. melitensis biovar reference strains but not in the other Brucella reference strains.

(i) bme18, bme19, and bme16

The three ORFs are located outside the 25-kb DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus and would be transcribed from the direct strand (Table 1; Fig. 3). The first ORF of 459 bp (bme18) would encode a highly hydrophobic (data not shown) putative protein of 152 amino acids showing 42.6 and 43.4% identity with the C-terminal ends of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA5030 and E. coli YnfM, respectively, that have been defined as probable transport proteins (Fig. 3; Tables 1 and 2). Identity with only the C-terminal end of both proteins suggests that the entire bme18 sequence is not cloned in plasmids pNV31112/pNV31113.

As detected by homology with other proteins in the database, bme19 would encode a protein of 498 amino acids that is probably located in the bacterial cytoplasm with >55% identity with the glycerol kinases (putative proteins and proteins identified by experimental evidence) of several bacteria (Fig. 3; Tables 1 and 2), enzymes that catalyze the formation of glycerol-3-phosphate from ATP and glycerol. However, a TAG stop codon was detected at amino acid position 56 that might block the synthesis of the hypothetical protein. Search for putative start codons downstream of this TAG codon with GeneMark.fbf allowed us to identify a putative gene, with a CTG start codon located 217 nucleotides downstream of this TAG stop codon, that would encode a protein of 370 amino acids that would be much smaller than the homologous glycerol kinases, which range in size between 482 and 501 amino acids. Sequencing of the bme19 region containing this hypothetical TAG stop codon in biovars 2 and 3 of B. melitensis and in the reference strains of the species B. abortus, B. suis, B. ovis, B. canis, and B. neotomae revealed that this stop codon is only present in the three described biovars of the species B. melitensis and in the reference strain of B. abortus. In the four other species reference strains the TAG codon is replaced by a CAG codon that would not stop the synthesis of the protein. Therefore, although the entire nucleotide sequence of bme19 has not been determined in these species, at least in B. suis, B. ovis, B. canis, and B. neotomae the bme19 gene would probably code for a full-length putative glycerol kinase, as determined by homology of Bme19 with glycerol kinases from other bacteria. Three cysteine residues conserved in the glycerol kinases of E. coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Thermus flavus that have been suggested to participate in the catalytic function of the enzyme (31) were also detected in the B. melitensis 16M Bme19 protein (amino acid positions 111, 253, and 267). Other characteristics of Bme19 that account for its function as a glycerol kinase are (i) that it contains two PROSITE motifs for carbohydrate kinases and (ii) that it contains the amino acid sequence YALEG that has been found in other glycerol kinases (31), the glycine residue being important for the conformation and functional properties of the enzyme (41).

bme16 has been partially characterized previously in B. melitensis 16M and B. abortus 544 (57) and would encode a 426-amino-acid protein with 12 transmembrane regions that would be located at the cytoplasmic membrane (Table 1). Bme16 showed 59.1% identity with PyrP from E. coli defined as a uracil transport protein and ca. 40% identity with other proteins (Table 2) identified or defined as uracil permeases. Some of these uracil permeases, such as E. coli K-12 UraA and Bacillus caldolyticus PyrP, are also predicted to be integral membrane proteins with 12 transmembrane-spanning segments (4, 21), which accounts for the function of Bme16 as a uracil permease. Uracil permeases allow the uptake of uracil and are involved in the biosynthesis of pyrimidine nucleotides via the salvage pathways (4, 21).

(ii) bme17, bme20, and bme21

The transcription of ORFs bme17, bme20, and bme21 would occur from the reverse strand (Table 1; Fig. 3). ORF bme17 has been partially characterized previously in B. abortus 544 (57). The left end of the B. abortus deletion is located inside this ORF (Fig. 3) that would encode in B. melitensis 16M a protein of 218 amino acids with a probable cytoplasmic location (Table 1). Bme17 displayed 43.7% identity with a putative protein of Streptomyces coelicolor (protein SCF62.20) of unknown function and lower homology degrees with proteins of other bacteria also with an unknown function (Table 2). Although the function of SCF62.20 from Streptomyces coelicolor has not been defined, the corresponding gene is located in a cluster encoding proteins that seem related to the synthesis of a polysaccharide (accession number AL121855), and some other genes from this cluster also show homology with the Brucella genes identified here (see below).

Bme20, predicted to be a cytoplasmic membrane protein, would be made up of 269 amino acids and displayed ca. 40% identity with proteins shown to act, or defined, as glucose-1-phosphate cytidylyltransferases from several bacteria (52, 64) (Fig. 3; Tables 1 and 2). Glucose-1-phosphate cytidylyltransferases catalyze the production of CDP–d-glucose from CTP and d-glucose-1-phosphate and are important for the construction of bacterial polysaccharides (52, 64).

The ORF bme21 (Fig. 3) would encode a cytoplasmic protein of 433 amino acids (Table 1) showing 48% identity with proteins SCF62.18 and BAA16904 from Streptomyces coelicolor and Synechocystis sp., respectively (Table 2). Function for these two proteins has not been assigned but their genes are located close to other genes that might be involved in the synthesis of a polysaccharide (accession numbers AL121855 and D90901, respectively). BAA16904 from Synechocystis sp. is located downstream of rfbC, encoding a dTPD-6-deoxy-l-mannose-dehydrogenase that shows 47.4% identity with the B. melitensis 16M Bme22 hypothetical protein encoded by bme22 that is located downstream of bme21 (Fig. 3; Table 2). The S. coelicolor SCF62.18 protein shows 34.1% identity with a C-methyltransferase from Streptomyces fradiae. Bme21 also showed 34.8 and 35.6% identity with SnoG and NovU from Streptomyces nogalater and Streptomyces spheroides, respectively. Both proteins are involved in the synthesis of the aminocoumarin antibiotic novobiocin, a noviose sugar being one of its three moieties. Function as C-methyltransferase for nucleotide-sugar has been proposed for Streptomyces spheroides NovU (48). Bme21 also displayed 29.9% identity with EryBIII from Saccharopolyspora erythraea that has been identified as a C-methyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of dTDP-mycarose (20). Alignment of EryBIII and several putative C-methyltransferases identified 53 conserved amino acids (20). Bme21 showed identity in 50 of these amino acid positions, which accounts for its function as a C-methyltransferase (data not shown).

(iii) bme22

The bme22 gene, which would be transcribed from the direct strand, was predicted to code for a protein of 184 amino acids probably located in the cytoplasm (Table 1; Fig. 3). Search for homology with other proteins in the database revealed that Bme22 from B. melitensis displayed ca. 45% identity with nucleotide-sugar epimerases from several bacteria (Table 2), among them StrX and Y4gL from Streptomyces glaucescens and Rhizobium sp., respectively. StrX from Streptomyces glaucescens is thought to act as an NDP–4-ketohexose-3,5-epimerase involved in the synthesis of the amino-glycoside 5′-hydroxystreptomycin (7) and the Y4gL protein from Rhizobium sp., defined as a dTDP–4-dehydrorhamnose-3,5-epimerase, is predicted to be involved in the synthesis of a polysaccharide (18).

(iv) bme23, bme24, bme25, bme26, and bme27

The five genes bme23, bme24, bme25, bme26, and bme27 would be transcribed from the reverse strand (Table 1; Fig. 3), the end of bme23 overlapping by 38 nucleotides the end of bme22 that would be transcribed from the direct strand. Bme23, a probable cytoplasmic protein, would be made up of 437 amino acids (Table 1) and showed 51.7% identity with SCF62.22 from Streptomyces coelicolor (Table 2), a protein of unknown function but encoded by a gene located in a cluster containing several genes that seem related to the synthesis of a polysaccharide (accession number AL121855). Bme23 also showed 32.8% identity with Cj1295 of Campylobacter jejuni. The function of this protein is also unknown, but its gene is located close to other C. jejuni genes that might be involved in the synthesis of a polysaccharide (i.e., putative sugar-nucleotide epimerase–dehydratase, aminotransferase, or acetyltransferase) (accession number AL139078) (Table 2).

Bme24 was predicted to be located in the cytoplasmic membrane and to be constituted by 353 amino acids (Table 1). Hypothetical function for Bme24, according to homology with other proteins in the database, would be that of sugar-nucleotide epimerase–dehydratase (Table 2).

Bme25, probably located in the periplasmic space, would be made up of 444 amino acids (Table 1). However, the PSORT program predicted an N-terminal signal sequence cleavable by the signal peptidase protein at amino acid 27 that would release a mature protein of 417 amino acids and 45.6 kDa. No homology with other proteins in the database was found for the B. melitensis 16M Bme25 protein.

Bme26 and Bme27 would probably be located in the bacterial cytoplasm and would be composed of 453 and 409 amino acids, respectively (Table 1). Bme26 shows homology with proteins from several bacteria defined or identified as aminotransferases, the SCF62.27 protein from Streptomyces coelicolor being the protein giving the highest level of identity (56.4%) (Table 2). Bme27 shows ca. 30% identity with proteins defined as sugar transferases (Table 2) and contains the motif EX7E that is found in many glycosyltransferases (3, 46).

(v) bme28

The bme28 gene would be transcribed from the direct strand and would code for a protein of 413 amino acids that would be probably located in the cytoplasmic membrane (Table 1; Fig. 3). Significant homology was only found with SCF62.25 from S. coelicolor (Table 2), a protein with unassigned function but whose gene is located in a cluster of genes that seem related to the synthesis of a polysaccharide (accession number AL121855).

(vi) bme29 and bme30

Genes bme29 and bme30 would be transcribed from the reverse strand (Table 1; Fig. 3). The bme29 gene would code for a cytoplasmic protein of 337 amino acids (Table 1) giving the highest percentages of homology with glycosyl transferases LgtD and LgtA from Neisseria spp. (Table 2) intervening in the biosynthesis of lipooligosaccharide (5, 14, 26). The amino acid sequence EX7E, which is found in many glycosyltransferases (3, 46), was also found in Bme29.

Bme30, which would be made up of 497 amino acids, was predicted to contain multiple transmembrane segments and to be located in the cytoplasmic membrane (Table 1). About 22% identity was found between Bme30 and several proteins involved in the synthesis of bacterial polysaccharides, which have been associated with the export of the polysaccharide across the cytoplasmic membrane, such as Wzx from E. coli (33, 49) (Table 2), Wzx from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (50) and ExoT from Rhizobium meliloti (23) (data not shown).

(vii) bme31 and bme1

Transcription of bme31 and bme1 would take place from the direct strand (Table 1; Fig. 3). The bme31 gene would code for a protein of 373 amino acids containing multiple transmembrane-spanning segments that would probably be located in the cytoplasmic membrane (Table 1). The PSORT program predicted an N-terminal signal sequence cleavable by signal peptidase at amino acid 21 that would release a protein of 352 amino acids and 37.6 kDa. Bme31 showed ca. 35% identity with proteins defined as undecaprenyl phosphate–N-acetylglucosamine transferase (UndP-GlcNAc transferase) from several bacteria (Table 2). UndP-GlcNAc transferase has been shown to be involved in the synthesis of bacterial polysaccharides by catalyzing the addition of the first sugar of a polysaccharide unit (GlcNAc from a UDP-GlcNAc sugar nucleotide donor substrate) to a UndP acceptor (1, 38, 61). UndP-GlcNAc transferases are predicted to be integral membrane proteins (61), as is also the case for Bme31.

The entire sequence of the bme1 gene, whose 3′ end has been characterized previously (57), revealed an ORF that would code for a protein of 293 amino acids predicted to be located either in the outer membrane or in the cytoplasmic membrane (Table 1). According to the PSORT program, Bme1 might be a lipoprotein with a possible modification site at amino acid 18. Bme1 showed ca. 30% identity with proteins from several bacteria identified as glycosyl transferases involved in the biosynthesis of polysaccharides (Table 2), which accounts for a more probable location of Bme1 in the inner membrane.

Occurrence in the genus Brucella of the 25-kb DNA fragment deleted from B. abortus

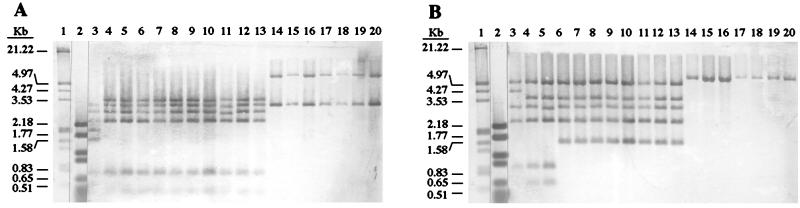

HindIII-digested DNA from the reference strains of all of the Brucella species and biovars was tested in Southern blot hybridization against digoxigenin-labeled pNV31112 and pNV31106 probes in order to investigate the occurrence in the Brucella genus of the 25-kb DNA fragment deleted from B. abortus.

Probe pNV31112 gave with B. melitensis 16M DNA (bv. 1) the HindIII band profile deduced from the nucleotide sequence and shown in Fig. 1 (Fig. 4A, lane 3). B. melitensis bv. 2 and 3 reference strains, B. ovis, B. canis, and B. neotomae reference strains and the reference strains of the five biovars of B. suis showed the same pattern, but it was different from that displayed by B. melitensis bv. 1. Thus, two HindIII fragments of 1,572 and 1,891 bp, revealed with B. melitensis bv. 1, were not detected in B. melitensis bv. 2 and 3, B. suis, B. ovis, B. canis, and B. neotomae, but these strains gave a 3,463-bp HindIII fragment that was not detected in B. melitensis bv. 1. The HindIII fragments of 1,572 and 1,891 bp are contiguous in B. melitensis 16M (bv. 1) (Fig. 1), suggesting that the absence of these two fragments and apparition of a HindIII fragment of 3,463 bp in the other Brucella strains is due to the absence of the HindIII site marked with an asterisk in Fig. 1. This HindIII site would also be absent in B. abortus as the 1,572-bp HindIII restriction fragment, which would be located outside the 25-kb deleted DNA fragment, is not detected (Fig. 4A, lanes 14 to 20). All of the B. abortus biovars only showed a HindIII band of 3,100 bp, which was also present in the other Brucella strains, and a specific HindIII fragment of ca. 6,100 bp comprising DNA at both sides of the 25-kb deletion (Fig. 4A, lanes 14 to 20).

FIG. 4.

Southern blot hybridization of Brucella spp. DNA HindIII restriction fragments with pNV31112 (A) and pNV31106 (B) digoxigenin-labeled probes. Lanes: molecular mass markers (lanes 1 and 2), B. melitensis 16M (bv. 1) (lane 3), B. melitensis 63/9 (bv. 2) (lane 4), B. melitensis Ether (bv. 3) (lane 5), B. suis 1330 (bv. 1) (lane 6), B. suis Thomsen (bv. 2) (lane 7), B. suis 686 (bv. 3) (lane 8), B. suis 40 (bv. 4) (lane 9), B. suis 513 (bv. 5) (lane 10), B. ovis 63/290 (lane 11), B. canis RM6/66 (lane 12), B. neotomae 5K33 (lane 13), B. abortus 544 (bv. 1) (lane 14), B. abortus 86/8/59 (bv. 2) (lane 15), B. abortus Tulya (bv. 3) (lane 16), B. abortus 292 (bv. 4) (lane 17), B. abortus B3196 (bv. 5) (lane 18), B. abortus 870 (bv. 6) (lane 19), and B. abortus C68 (bv. 9) (lane 20).

Probe pNV31106 gave with B. melitensis 16M DNA (bv. 1) the HindIII band profile deduced from the nucleotide sequence and shown in Fig. 1 (Fig. 4B, lane 3). The reference strains of B. melitensis bv. 2 and 3 displayed the same hybridization pattern that differed from that of B. melitensis bv. 1. Thus, a band of 4,248 bp seen in B. melitensis bv. 1 was not detected in B. melitensis bv. 2 and 3 that displayed two specific bands of ca. 3,600 and 650 bp. These results suggest that biovars 2 and 3 of B. melitensis contain an additional HindIII site located in the B. melitensis bv. 1 HindIII fragment of 4,248 bp (Fig. 1). This additional HindIII site would also be present in the five biovars of B. suis and in B. ovis, B. canis, and B. neotomae reference strains (Fig. 4B, lanes 6 to 13), but these strains would have lost the right HindIII site of the 950-bp HindIII fragment of B. melitensis (Fig. 1). This event would explain the loss of the HindIII fragments of 950 and 650 bp detected in B. melitensis bv. 2 and 3 and the apparition of a HindIII fragment of 1,600 bp (Fig. 4B, lanes 6 to 13). As expected, the seven B. abortus biovar reference strains only developed a 6,100-bp HindIII fragment (Fig. 4B, lanes 14 to 20), also detected with the pNV31112 probe, corresponding to DNA adjacent to both sides of the 25-kb fragment deleted in this species.

DISCUSSION

The nucleotide sequence of a B. melitensis 16M large DNA fragment of 25,064 bp (Fig. 3), known to be deleted in B. abortus (57, 58) and partially sequenced previously (57), has been entirely determined. A short direct repeat of 4 bp (GTGC) was found in B. melitensis 16M at each side of the fragment deleted in B. abortus (Fig. 2), the deletion removing one of this 4-bp repeat in B. abortus (Fig. 2). Short direct repeats have been reported to intervene in the generation of large deletions by a mechanism of illegitimate recombination involving strand slippage during replication that removes one of the direct repeats (40, 59, 60). It has been shown, in bacterial model systems, that deletion frequencies are increased by reducing the distance between the direct repeats (10), by increasing the direct repeat lengths, and by the presence of inverted repeats flanking the direct repeats (40). No inverted repeats were found flanking the 4-bp direct repeats located at both sides of the B. melitensis 16M DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus. However, several regions able to form hairpin structures have been detected in the deleted fragment (data not shown) that might have contributed to the excision of the 25-kb fragment in B. abortus. This deletion would have a low formation frequency since the length of the direct repeats is very short, the distance between them is very long, and no inverted repeats are found close to the direct repeats. Moreover, the deletion has been detected only in B. abortus and probably occurred before the differentiation of this species in its biovars, all of them lacking the 25-kb DNA fragment (Fig. 4).

Twenty-one putative genes identified in the B. melitensis 16M DNA are completely deleted in B. abortus (Fig. 3), two other genes located in each end of the deleted fragment (bme10 and bme17) are partially removed from this species, and the corresponding proteins might not be synthesized in B. abortus. Most of these 23 genes would code for proteins showing a significant degree of identity with proteins involved in the synthesis of polysaccharides in other bacteria (57) (Table 2), suggesting that they might lead to the synthesis of a Brucella polysaccharide. Two main pathways have been described for the biosynthesis of polysaccharides in bacteria. In both mechanisms the synthesis of the polysaccharide subunit starts with the linkage of a sugar nucleotide, usually UDP-GlcNAc, to UndP that is anchored to the inner membrane. The first pathway, known as the Wzy (polymerase)-dependent pathway, has been shown to be involved in the synthesis of many lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O-chains, mainly in heteropolymeric O-chains (those made of repeating units of different sugars) (61, 62). In the Wzy-dependent pathway, the repeat units of the polysaccharide are synthesized, at the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane, by the action of glycosyltransferases that transfer a sugar from a nucleotide-sugar complex. The repeat units are exported across the cytoplasmic membrane by Wzx, a multiple membrane-spanning protein, and polymerized at the periplasmic face by the Wzy polymerase (61, 62). The second main mechanism for the biosynthesis of bacterial polysaccharides, known as the Wzy-independent pathway, has been observed in homopolymeric polysaccharides (made of repeating units of the same sugar). The polysaccharide is synthesized, in the cytosolic face of the inner membrane, by the sequential addition of sugars by glycosyltransferases, and then it is transported across the cytoplasmic membrane by an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter (61, 62). In the case of LPS molecules, the O-polysaccharide chains synthesized by the Wzy-dependent or Wzy-independent pathway would then be ligated to the lipid A core complex by the WaaL ligase (61, 62). The mechanism of transport of LPS and polysaccharides not attached to lipid A core, such as capsular polysaccharides and exopolysaccharides (EPS), across the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria remains almost unexplored. However, some periplasmic proteins and OMPs have been suggested to be involved in this process in some capsular polysaccharides and EPS (8, 19, 43, 49, 50, 63).

According to homologies with other proteins in the database, Bme31 might be the enzyme catalyzing the transfer of the first sugar of a polysaccharide unit (probably GlcNAc that would be transferred from a UDP-GlcNAc sugar-nucleotide donor substrate) to UndP attached to the cytoplasmic membrane. Six putative glycosyltransferases (Bme1, Bme6, Bme7, Bme8, Bme27, and Bme29), enzymes that add a sugar unit from a nucleotide-sugar substrate to a polysaccharide growing chain, were identified in the 25-kb DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus (57) (Table 2). A specific sugar transferase is required for each different linkage between the sugars of a polysaccharide unit, thus suggesting that if the genes identified in the DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus lead to the synthesis of a polysaccharide, it would be made up of at least six sugar units, in addition to the initiator GlcNAc.

Eight hypothetical proteins that might be involved in the synthesis of nucleotide-sugar complexes or in the chemical modification of sugars have also been identified: Bme9, Bme10, Bme22, and Bme24 show homology with epimerases and dehydratases from other polysaccharide clusters (57) (Table 2); Bme4 was identified as a putative acetyltransferase (57), Bme26 was identified as a putative aminotransferase, and Bme21 was identified as a putative methyltransferase; Bme20 might act as a glucose-1-phosphate cytidylyltransferase catalyzing the production of the sugar-nucleotide CDP–d-glucose from CTP and d-glucose-1-phosphate; and Bme9 showed 64.0% identity in 356 amino acids overlapping with Gmd from B. melitensis 16M (data not shown), a putative GDP-mannose dehydratase involved in biosynthesis of the LPS O-chain (24). However, the highest level of identity (68.1% identity) was obtained with NoeL (57), a GDP-mannose dehydratase from Rhizobium sp. (18).

According to its hydrophobicity profile, Bme3 was previously proposed to be equivalent to Wzx (57), a multiple membrane-spanning protein that promotes the export of polysaccharides across the cytoplasmic membrane in the Wzy-dependent pathway (15, 62). However, the multiple membrane-spanning hypothetical protein Bme30 identified in this work showed homology with Wzx from E. coli and serovar Typhimurium and with ExoT from R. meliloti, a protein that seems to be involved in the export of EPS (23). Therefore, Bme30 seems to be a better candidate than Bme3 for the transport of the hypothetical Brucella polysaccharide across the cytoplasmic membrane. Wzy, the polymerase in the Wzy-dependent pathway, is also predicted to be located in the cytoplasmic membrane and to contain multiple membrane-spanning segments (62). B. melitensis 16M Bme3, showing a hydrophobicity profile similar to that of Wzy from other bacteria (data not shown), is the sole hypothetical protein without a clear assigned function that seems to fulfill this requirement. Thus, Bme3 might be the Wzy polymerase for the synthesis of the Brucella polysaccharide.

Another protein intervening in the synthesis of bacterial polysaccharides by the Wzy-dependent pathway is Wzz, which is involved in the chain length determination (62). The Wzz functional homologous proteins are ca. 42 kDa, contain two highly conserved potential transmembrane domains in the N- and C-terminal regions, and have been mainly associated with the biosynthesis of bacterial O-polysaccharides and some capsular polysaccharides (62). Several proteins of ca. 80 kDa mainly involved in the biosynthesis of EPS have been identified as Wzz-like proteins although, in general, their function has not been experimentally established. These proteins are larger than the Wzz functional homologues and contain a C-terminal cytoplasmic domain that Wzz lacks (25, 62). One of the Wzz-like proteins is ExoP from Rhizobium meliloti, which is thought to intervene in the polymerization and/or export process of the succinoglycan octasaccharide units (6, 42), although it has also been suggested that ExoP must play another critical role in the biosynthesis of this EPS (25). The B. melitensis 16M bme12 gene would code for a protein of 79 kDa (57), predicted to be located in the cytoplasmic membrane with two membrane-spanning domains in the N- and C-terminal ends of the protein, which shows homology with ExoP from R. meliloti (57) and a similar hydrophobicity profile (data not shown). Therefore, Bme12 might be involved in the regulation of polysaccharide length and/or export of the polysaccharide.

Considering the homology of several putative genes located in the B. melitensis 16M 25-kb DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus with genes involved in the synthesis of several bacterial EPS, the possibility that these genes lead to the synthesis of an EPS must be taken into account. This possibility would be reinforced by the identification of proteins involved in the transport of the polysaccharide across the periplasm and the outer membrane. Genes encoding periplasmic proteins and OMPs have been identified in several clusters directing the synthesis of several bacterial EPS and capsular polysaccharides and are thought to be involved in the export of the polysaccharide across the periplasm and the outer membrane (8, 19, 43, 49, 50, 63). Three proteins predicted to be located in the periplasmic space—Bme2, Bme11, and Bme25—would be encoded in the 25-kb DNA fragment of B. melitensis 16M deleted in B. abortus (57) (Table 1). Bme11 showed homology with R. meliloti ExoF (57) involved in the synthesis of the EPS succinoglycan. ExoF shows homology with the periplasmic E. coli KpsD protein, which is involved in the biosynthesis of the K5 capsule (43, 63), and was suggested to play a role in the export of the rhizobial EPS succinoglycan (22). Accordingly, periplasmic Bme11 might be involved in the last steps of export of the hypothetical B. melitensis polysaccharide. Bme5 that corresponds to Omp31 (56, 57), a B. melitensis 16M major immunogenic OMP, might be involved in the export of the polysaccharide across the outer membrane, as was shown for other bacterial OMPs. This is the case for the OMP Wza encoded in the cluster responsible for the synthesis of the EPS colanic acid in E. coli and Salmonella enterica (43, 49, 50), the OMP AmsH of Erwinia amylovora involved in the synthesis of EPS (8), and the Neisseria meningitidis OMP CtrA involved in capsule expression (19).

The B. melitensis periplasmic Bme2 and Bme25 proteins did not show clear homology with other proteins in the database (57) (Table 2), and it is difficult to determine their hypothetical functions. Taking into account the probable periplasmic locations of these proteins, if they are involved in the synthesis of a Brucella spp. polysaccharide they might act in the last steps of the pathway after the export of the polysaccharide across the cytoplasmic membrane. Bme17, Bme23, and Bme28 showed homology with three Streptomyces coelicolor proteins of unknown function but whose genes are located close to other genes that seem involved in the synthesis of a polysaccharide (accession number AL121855), and they might also be related to the synthesis of a Brucella polysaccharide.

Several clusters for the biosynthesis of bacterial polysaccharides are controlled by the action of regulatory proteins (9, 27, 51). Bme13 and Bme14, which would be encoded by genes flanking the right side of the B. melitensis 16M DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus (Fig. 3), showed homology with regulatory proteins (57) and might have a regulatory role in the synthesis of the hypothetical Brucella polysaccharide. However, they might be unrelated to this process and be involved in the regulation of another process. Finally, putative B. melitensis 16M proteins encoded by genes flanking the left side of the large DNA fragment deleted from B. abortus (Bme18, Bme19, and Bme16) (Fig. 3; Table 2) seem to be unrelated to the synthesis of a polysaccharide.

Considering that the 25-kb DNA fragment deleted in B. abortus has been detected in all of the other Brucella species (Fig. 4), if the genes that have been identified lead to the synthesis of a polysaccharide, that polysaccharide would be present in all of the Brucella species with the exception of B. abortus. Since the polysaccharides identified in the genus Brucella have been detected in all of the species including B. abortus, the genes described here and in a previous study (57) might intervene in the synthesis of a polysaccharide not identified until now. In spite of the fact that most of these genes are homologous to genes involved in the synthesis of other bacterial polysaccharides and that Omp31 (Bme5) has been shown to be synthesized in all of the Brucella species except B. abortus (58) and to be located in the Brucella outer membrane (12), the possibility that they no longer lead to the synthesis of a polysaccharide must be taken into account. Genes encoding homologs of several flagellum-related proteins have been found in B. abortus that, as in the other Brucella species, is a nonmotile bacterium, and it was hypothesized that brucellae may have lost motility during evolution because it is not essential or even detrimental for its cycle as animal pathogens (28). The genus Brucella is a member of the alpha-2 subdivision of the class Proteobacteria that contains other members that live in close association with eucaryotic cells, such as Rhizobium and Agrobacterium spp., both of which synthesize an EPS important for the interaction with the host plant cells. The common ancestor of the alpha-2 subdivision of the class Proteobacteria has been suggested to have EPS (36), and the genes found in the B. melitensis 16M DNA fragment of 25 kb deleted in B. abortus might be a remnant of this common ancestor.

Deletions that enhance the virulence of bacterial pathogens have been described and suggested to complement gene acquisition, such as pathogenicity islands, in the evolution of bacterial pathogens, even allowing a broadening of the host range (34). The deletion that occurred in B. abortus might have contributed to an evolution of Brucella spp., allowing the adaptation to survive in a new animal host. Further studies are necessary to determine whether a polysaccharide not identified until present is synthesized in the genus Brucella. Discovery of a novel polysaccharide, probably not synthesized in B. abortus, would be of great interest since polysaccharides are virulence factors in Brucella spp. and other microorganisms and this might also explain some of the differences in pathogenicity and host preference among the brucellae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Manuel Sánchez Hernández for his valuable help with DNA sequence determination and Jean Michel Verger and Maggy Grayon for providing Brucella strains.

Nieves Vizcaíno was financed by project FAIR5-CT97–3360 from the European Union.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander D C, Valvano M A. Role of the rfe gene in the biosynthesis of the Escherichia coli O7-specific lipopolysaccharide and other O-specific polysaccharides containing N-acetylglucosamine. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7079–7084. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.7079-7084.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alton G G, Jones L M, Angus R D, Verger J M. Techniques for the brucellosis laboratory. Paris, France: Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amor P A, Whitfield C. Molecular and functional analysis of genes required for expression of group IB K antigens in Escherichia coli: characterization of the his-region containing gene clusters for multiple cell-surface polysaccharides. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:145–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5631930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen P S, Frees D, Fast R, Mygind B. Uracil uptake in Escherichia coli K-12: isolation of uraAmutants and cloning of the gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2008–2013. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2008-2013.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arking D, Tong Y, Stein D C. Analysis of lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis in the Neisseriaceae. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:934–941. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.934-941.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker A, Niehaus K, Pühler A. Low-molecular-weight succinoglycan is predominantly produced by Rhizobium melilotistrains carrying a mutated ExoP protein characterized by a periplasmic N-terminal domain and a missing C-terminal domain. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:191–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beyer S, Distler J, Piepersberg W. The str gene cluster for the biosynthesis of 5′-hydroxystreptomycin in Streptomyces glaucescensGLA.0 (ETH 22794): new operons and evidence for pathway-specific regulation by StrR. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;250:775–784. doi: 10.1007/BF02172990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bugert P, Geider K. Molecular analysis of the ams operon required for exopolysaccharide synthesis of Erwinia amylovora. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:917–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman M R, Kao C C. EpsR modulated production of extracellular polysaccharides in the bacterial wilt pathogen Ralstonia (Pseudomonas) solanacearum. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:27–34. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.27-34.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chédin F, Dervyn E, Dervyn R, Ehrlich S D, Noirot P. Frequency of deletion formation decreases exponentially with distance between short direct repeats. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:561–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cloeckaert A, Debbarh H S A, Vizcaíno N, Saman E, Dubray G, Zygmunt M S. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the Brucella melitensis bp26gene coding for a protein immunogenic in infected sheep. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;140:139–144. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(96)00169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cloeckaert A, de Wergifosse P, Dubray G, Limet J N. Identification of seven surface-exposed Brucellaouter membrane proteins by use of monoclonal antibodies: immunogold labeling for electron microscopy and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3980–3987. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3980-3987.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cloeckaert A, Verger J M, Grayon M, Zygmunt M S, Grépinet O. Nucleotide sequence and expression of the gene encoding the major 25-kilodalton outer membrane protein of Brucella ovis: evidence for antigenic shift, compared with the the other Brucellaspecies, due to a deletion in the gene. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2047–2055. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2047-2055.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danaher R J, Levin J C, Arking D, Burch D L, Sandlin R, Stein D C. Genetic basis of Neisseria gonorrhoeaelipooligosaccharide antigenic variation. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7275–7279. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7275-7279.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman M F, Marolda C L, Monteiro M A, Perry M B, Parodi A J, Valvano M A. The activity of a putative polyisoprenol-linked sugar translocase (Wzx) involved in Escherichia coliO antigen assembly is independent on the chemical structure of the O repeat. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:35129–35138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ficht T A, Bearden S W, Sowa B A, Adams L G. DNA sequence and expression of the 36-kilodalton outer membrane protein gene of Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3281–3291. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3281-3291.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ficht T A, Bearden S W, Sowa B A, Marquis H. Genetic variation at the omp2locus of the brucellae: species-specific markers. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1135–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freiberg C, Fellay R, Bairoch A, Broughton W J, Rosenthal A, Perret X. Molecular basis of symbiosis between Rhizobiumand legumes. Nature. 1997;387:394–401. doi: 10.1038/387394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frosch M, Müller D, Bousset K, Müller A. Conserved outer membrane protein of Neisseria meningitidisinvolved in capsule expression. Infect Immun. 1992;60:798–803. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.798-803.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaisser S, Böhm G A, Doumith M, Raynal M-C, Dhillon N, Cortés J, Leadlay P F. Analysis of eryBI, eryBIII and eryBVII from the erythromycin biosynthetic gene cluster in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;258:78–88. doi: 10.1007/s004380050709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghim S-Y, Neuhard J. The pyrimidine biosynthesis operon of the thermophile Bacillus caldolyticusincludes genes for uracil phosphoribosyltransferase and uracil permease. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3698–3707. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3698-3707.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glucksmann M A, Reuber T L, Walker G C. Family of glycosyl transferases needed for the synthesis of succinoglycan by Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7033–7044. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.7033-7044.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glucksmann M A, Reuber T L, Walker G C. Genes needed for the modification, polymerization, export, and processing of succinoglycan by Rhizobium meliloti: a model for succinoglycan biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7045–7055. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.7045-7055.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Godfroid F, Cloeckaert A, Taminiau B, Danese I, Tibor A, de Bolle X, Mertens P, Letesson J-J. Genetic organization of the lipopolysaccharide O-antigen biosynthesis region of Brucella melitensis 16M (wbk) Res Microbiol. 2000;151:655–668. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(00)90130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.González J E, Semino C E, Wang L-X, Castellano-Torres L E, Walker G C. Biosynthetic control of molecular weight in the polymerization of the octasaccharide subunits of succinoglycan, a symbiotically important exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13477–13482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gotschlich E. Genetic locus for the biosynthesis of the variable portion of Neisseria gonorrhoeaelipooligosaccharide. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2181–2190. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray J X, Djordjevic M A, Rolfe B G. Two genes that regulate exopolysaccharide production in Rhizobiumsp. strain NGR234: DNA sequences and resultant phenotypes. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:193–203. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.193-203.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halling S M. On the presence and organization of open reading frames of the nonmotile pathogen Brucella abortussimilar to class II, III, and IV flagellar genes and to LcrD virulence superfamilly. Microb Comp Genomics. 1998;3:21–29. doi: 10.1089/omi.1.1998.3.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halling S M, Zehr E S. Polymorphism in Brucellaspp. due to highly repeated DNA. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6637–6640. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6637-6640.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmann K, Bucher P, Falquet L, Bairoch A. The PROSITE database, its status in 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:215–219. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang H-S, Kabashima T, Ito K, Yin C-H, Nishiya Y, Kawamura Y, Yoshimoto T. Thermostable glycerol kinase from Thermus flavus: cloning, sequencing, and expression of the enzyme gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1382:186–190. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(97)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marck C. “DNA Strider”: a “C” program for the fast analysis of DNA and protein sequences on the Apple Macintosh family of computers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1829–1836. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.5.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marolda C L, Feldman M F, Valvano A A. Genetic organization of the O7-specific lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis cluster of Escherichia coliVW187 (O7:K1) Microbiology. 1999;145:2485–2495. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-9-2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maurelli A T, Fernández R E, Bloch C A, Rode C K, Fasano A. “Black holes” and bacterial pathogenicity: a large genomic deletion that enhances the virulence of Shigella spp. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3943–3948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michaux-Charachon S, Bourg G, Jumas-Bilak E, Guigue-Talet P, Allardent-Servent A, O'Callaghan D, Ramuz M. Genome structure and phylogeny in the genus Brucella. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3244–3249. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3244-3249.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreno E. Evolution of Brucella. In: Plommet M, editor. Advances in brucellosis research. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Pudoc Scientific Publishers; 1992. pp. 198–218. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakai K, Kanehisa M. Expert system for predicting protein localization sites in gram-negative bacteria. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1991;11:95–110. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohta M, Ina K, Kusuzaki K, Kido N, Arakawa Y, Kato N. Cloning and expression of the rfe-rff gene cluster of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1853–1862. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peeters B P H, de Boer J H, Bron S, Venema G. Structural plasmid instability in Bacillus subtilis: effect of direct and inverted repeats. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;212:450–458. doi: 10.1007/BF00330849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pettigrew D W, Liu W Z, Holmes C, Meadow N D, Roseman S. A single amino acid change in Escherichia coliglycerol kinase abolishes glucose control of glycerol utilization in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2846–2852. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2846-2852.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reuber, T. L., and G. C. Walker. 1993. Biosynthesis of succinoglycan, a symbiotically important exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti.74:269–280. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Roberts I S. The biochemistry and genetics of capsular polysaccharide production in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:285–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sangari F J, García-Lobo J M, Agüero J. The Brucella abortusvaccine strain B19 carries a deletion in the erythritol catabolic genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:337–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saxena I M, Brown R M, Fevre M, Geremia R A, Henrissat B. Multidomain architecture of β-glycosyl transferases: implications for mechanism of action. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1419–1424. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1419-1424.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shmatkov A M, Melikyan A M, Chernousko F L, Borodovsky M. Finding prokaryotic genes by the “frame-by-frame” algorithm: targeting gene starts and overlapping genes. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:874–886. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.11.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steffensky M, Mühlenweg A, Wang Z-X, Li S-M, Heide L. Identification of the novobiocin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces spheroidesNCIB 11891. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;41:1904–1909. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.5.1214-1222.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stevenson G, Andrianopoulos K, Hobbs M, Reeves P R. Organization of the Escherichia coliK-12 gene cluster responsible for production of the extracellular polysaccharide colanic acid. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4885–4893. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4885-4893.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stevenson G, Lan R, Reeves P R. The colanic acid cluster of Salmonella entericahas a complex history. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;191:11–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stout V, Torres-Cabassa A, Maurizi M R, Gutnick D, Gottesman S. RcsA, an unstable positive regulator of capsular polysaccharide synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1738–1747. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1738-1747.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thorson J S, Kelly T M, Liu H-W. Cloning, sequencing, and overexpression in Escherichia coli of the α-d-glucose-1-phosphate cytidylyltransferase gene isolated from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1840–1849. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1840-1849.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verger J M, Grimont F, Grimont P A D, Grayon M. Brucella, a monospecific genus as shown by deoxyribonucleic acid hybridization. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1985;35:292–295. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verger J M, Grimont F, Grimont P A D, Grayon M. Taxonomy of the genus Brucella. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1987;138:235–238. doi: 10.1016/0769-2609(87)90199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vizcaíno N, Cloeckaert A, Verger J M, Grayon M, Fernández-Lago L. DNA polymorphism in the genus Brucella. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1089–1100. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vizcaíno N, Cloeckaert A, Zygmunt M S, Dubray G. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the Brucella melitensis omp31gene coding for an immunogenic major outer membrane protein. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3744–3751. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3744-3751.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vizcaíno N, Cloeckaert A, Zygmunt M S, Fernández-Lago L. Molecular characterization of a Brucella species large DNA fragment deleted in Brucella abortus: evidence for a locus involved in the synthesis of a polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2700–2712. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2700-2712.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vizcaíno N, Verger J M, Grayon M, Zygmunt M S, Cloeckaert A. DNA polymorphism at the omp-31 locus of Brucella spp.: evidence for a large deletion in Brucella abortus, and other species-specific markers. Microbiology. 1997;143:2913–2921. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-9-2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang J, Masuzawa T, Li M, Yanagihara Y. An unusual illegitimate recombination accurs in the linear-plasmid-encoded outer-surface protein A of Borrelia afzelii. Microbiology. 1997;143:3819–3825. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weston-Hafer K, Berg D E. Palindromy and the location of deletion endpoints in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 1989;121:651–658. doi: 10.1093/genetics/121.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Whitfield C. Biosynthesis of lipopolysaccharide O antigens. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:178–185. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whitfield C, Amor P A, Köplin R. Modulation of the surface architecture of gram-negative bacteria by the action of surface polymer:lipid A-core ligase and by determinants of polymer chain length. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:629–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2571614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wunder D E, Aaronson W, Hayes S F, Bliss J M, Silver R P. Nucleotide sequence and mutational analysis of the gene encoding KpsD, a periplasmic protein involved in transport of polysialic acid in Escherichia coliK1. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4025–4033. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.4025-4033.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang L, Radziejewska-Lebrecht J, Krajewska-Pietrasik D, Toivanen P, Skurnik M. Molecular and chemical characterization of the lipopolysaccharide O-antigen and its role in the virulence of Yersinia enterocoliticaserotype O:8. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:63–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.1871558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]