Abstract

Immunological interaction between the host and Helicobacter pylori seems to play a critical role in follicular formation in gastric mucosa. We reported H. pylori-induced follicular gastritis model using neonatally thymectomized mice. In this study, we investigated the involvement of various cytokines in this model. BALB/c mice were thymectomized on the third day after birth (nTx). At 6 weeks old, these mice were orally infected with H. pylori. Histological studies showed that follicular formation occurred from 8 weeks after the infection and that most of the infiltrating lymphocytes were CD4+ and B cells. Neutrophils increased transiently at 1 week after the infection. Gamma interferon, interleukin-7 (IL-7), and IL-7 receptor were expressed in the stomach of the nTx mice irrespective of the infection. In contrast, expressions of the tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-4 and lymphotoxin-α genes were remarkably upregulated by the infection. Our findings suggest that follicular formation may require cooperative involvement of a Th2-type immune response, tumor necrosis factor alpha and lymphotoxin-α in addition to the Th1-type immune response in H. pylori-induced gastritis in nTx mice.

Evidence is accumulating that Helicobacter pylori infection is involved in the pathogenesis of gastric ulcers, cancer, and low-grade lymphomas of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALToma), in addition to atrophic gastritis (16, 27, 37, 39). Among these diseases, a characteristic feature of MALToma is the development of secondary follicles in the corporal lesions before or at the onset of lymphoma (6). The immunological interaction between the host and H. pylori seems to play a critical role in the pathophysiology of follicular gastritis. However, the mechanisms of host immune reactions to H. pylori infection and subsequent follicular formation in the stomach remain unclear.

Use of gene knockout and/or transgenic mice has revealed the in vivo functions of a number of cytokines or cytokine receptors in not only normal but also various pathological conditions. It is known that lymphotoxin α and β (LT-α and -β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and TNF receptors I and II (TNF-R I and II) are involved in constructing the germinal centers of the Peyer's patches, spleen, or peripheral lymph nodes (19). Moreover, injection of anti-interleukin-7 receptor (IL-7R) antibody into pregnant mice has been shown to inhibit the development of germinal centers in Peyer's patches after birth (1, 10). These findings suggest that multiple factors seem to be required for the formation of germinal centers in lymphoid tissue.

BALB/c mice thymectomized on the third day after birth (nTx) spontaneously develop autoimmune gastritis. In nTx BALB/c mice that show a Th1-predominant reaction in the stomach, CD4-positive Th1 cells often induce autoimmune gastritis, whereas lymphoid follicles never occur (12, 13, 25, 31). In our previous study, we showed that infection of BALB/c mice that had autoimmune gastritis with mouse-adapted H. pylori permitted successful colonization of H. pylori in the corpus, leading to follicular gastritis similar to human MALToma (26). In the present study, we examined by using this murine model the histopathology and cytokine responses in the early development of gastric lymphoid follicles to H. pylori infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and thymectomy.

Male and female BALB/c Cr.Slc mice (Japan SLC, Shizuoka, Japan) were bred in our animal facility in Kyoto University under specific-pathogen-free conditions. Neonatal thymectomy was performed on the third day after birth under ether anesthesia, as described previously (12, 13, 25, 26, 31). In a preliminary study, we confirmed the findings reported previously (12, 13, 25, 26, 31), in which there were no immunological differences between female and male mice; we also confirmed the severity of the autoimmune gastritis and the immunological findings, including antiparietal autoantibodies and infiltrating lymphocytes (data not shown). The mice were divided into four groups (n = 10 in each group): (i) normal (non-nTx) mice without H. pylori infection, (ii) normal (non-nTx) mice with H. pylori infection, (iii) nTx mice without H. pylori infection, and (iv) nTx mice with H. pylori infection.

Bacteria and infection.

H. pylori (TN2FG4) isolated from a patient with a duodenal ulcer was donated from M. Nakao (Pharmaceutical Research Division, Takeda Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan). It was maintained in Blood Agar Base No. 2 with horse serum (5% [vol/vol]) containing amphotericin B at 2.5 mg/liter, trimethoprim at 5 mg/liter, polymyxin B at 1,250 IU/liter, and vancomycin at 10 mg/liter. The plates were incubated in a microaerophilic atmosphere at 37°C for 48 h. The inoculated H. pylori strain, TN2FG4, was CagA and VacA positive as described elsewhere (38). Both nTx and non-nTx mice at 6 weeks old were orally infected with 108 H. pylori organisms as described previously (26). Infected mice were sacrificed 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks later. Colonization of H. pylori was confirmed by PCR Southern blot analysis for the urease gene using DNA extracted from the corpus mucosa. The urease gene was found to be amplified at 12 weeks after infection (26). Noninfected mice were sacrificed at the same time. The sera and stomachs were stored until use. We confirmed the abnormal hyperimmune status by measuring the levels of autoantibody in serum against the parietal cells by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at 6 weeks after thymectomy and before infection, as described previously (26).

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

The stomach was removed from each mouse, fixed with 4% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde (pH 7.2), and prepared for histologic examination. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunohistochemical staining with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) was performed on freshly frozen sections by the avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase method, as described previously (26). Briefly, freshly frozen sections were fixed in acetone for 10 min, rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2), and incubated with 10% normal rat serum (as a blocking agent) for 20 min. They were incubated for 1 h with the biotin-labeled MAbs as follows. The commercially available MAbs to mouse surface markers were rat anti-mouse B220, immunoglobulin M (IgM), CD4, and CD8 MAbs (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). After incubation, the sections were washed with PBS and then incubated with ABC complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) for another 30 min. Sections washed with PBS were reacted with a fresh mixture of 0.05% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine and 0.005% H2O2 in Tris buffer (0.05 M, pH 7.6) and then washed with distilled water. The controls were exposed to normal rat serum instead of the MAbs. These control samples showed no staining.

Flow cytometry.

Infiltrating cells were isolated from the stomach of nTx mice with or without H. pylori infection according to the method reported previously (26). For flow cytometric analysis, 106 viable infiltrating cells were incubated with phycoerythrin or fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated MAbs, anti-γδ-TCR and MAC-1 (Pharmingen) at 4°C for 30 min. The labeled cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with an Epics XL (Coulter, Miami, Fla.).

Semiquantitive RT-PCR.

To analyze cytokine gene expressions by reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR), total RNA was extracted with the RNA extraction solution Isogen (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) from the murine stomach. Total RNA was reverse transcribed into DNA with the SuperScript Preamplification System (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). The total RNA in the reaction mixture was heated at 42°C for 50 min and at 70°C for another 15 min and then chilled on ice.

PCR was performed with a mixture of cDNA, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, a 200 mM concentration of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, N.J.), a 50 pM concentration of each specific primer, and 1.0 U of Taq DNA polymerase (AmpliTaq Gold; Perkin-Elmer). The specific primers of mouse TNF-α, IL-4, IL-7, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and β-actin were purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, Calif.). The specific primers of LT-α and IL-7R were synthesized according to the sequence described previously (1, 15). The primer sequences in this study were as follows: for IL-4, 5′-CCAGCTAGTTGTCATCCTGCTCTCCTTTCTCG and 3′-CGTGGTACTTACTCAGGTTCAGGTGTAGTGAC; for IL-7, 5′-GCCTGTCACATCATCTGAGTGAA and 3′-CAGGAGGCATCCAGGAACTTCTG; for IL-7R, 5′-CGAGTGAAATGCCTAACTC and 3′-GCGTCCAGTTGCTTTCAC; for IFN-γ, 5′-TGCATCTTGGCTTTGCAGCTCTTCCTCATGGC and 3′-CGGTTCAAACTCCAGTTGTTGGTGTCCAGGT, for TNF-α, 5′-TTCTGTCTGAACTTCGGGGTGATCGGTCC and 3′-GTATGAAGCAAATCGGCTGACGGTGTGGG; for LT-α, 5′-TCTCCACCTCTTGAGGGTG and 3′-ACGATCCGTGCTTGCTCTC; and for β-actin, 5′-GTGGGCCGCTCTAGGCACCAA and 3′-CTCTTTGATGTCACGCACGATTTC. Amplification was performed with a thermal cycler (GeneAmp PCR System 9600R; Perkin-Elmer) for 35 cycles, each of which consisted of 20 s at 95°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The final cycle induced an extension step for 10 min at 72°C. A 10-ml portion of each PCR product was electrophoresed on a 2.0% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. The densities of bands on the gels were measured by an image autoanalyzing system (Fotodyne, FOTOanalyst, and Archive ECLIPSE; Advanced American Biotechnology, Fullerton, Calif.) and expressed as the absorbance level. Semiquantitative levels of each cytokine were corrected by the β-actin density of each sample.

Statistical analysis.

All results were expressed as mean ± the standard deviation for each sample, except where noted. The generalized Wilcoxon t test was used to compare absorbance levels between nTx only and nTx with H. pylori infection for each cytokine. A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry.

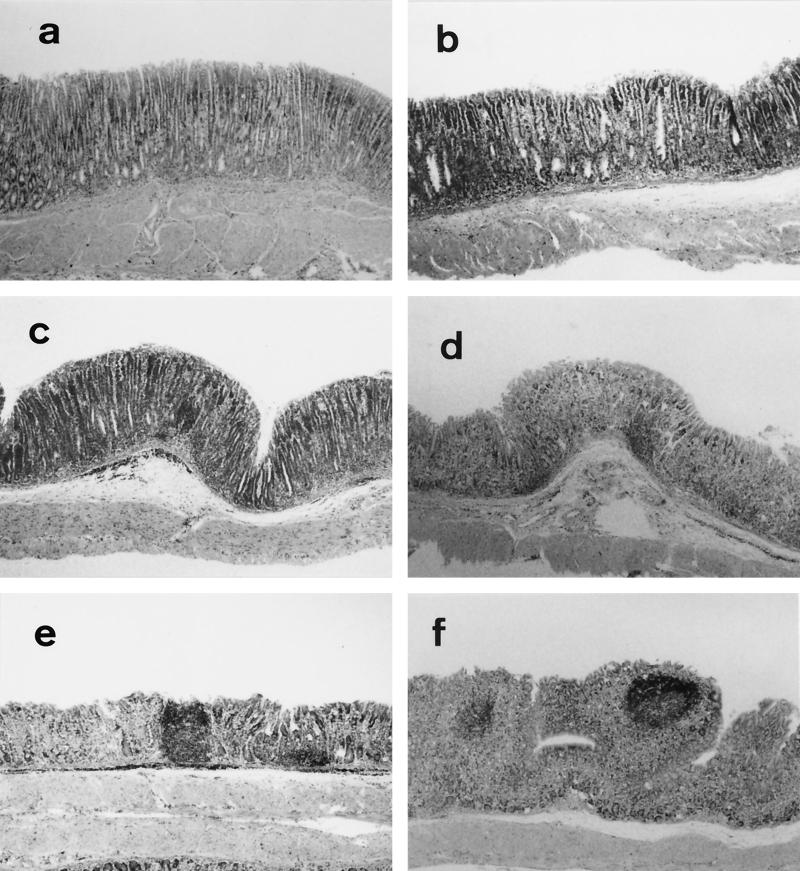

Approximately 60% of the nTx mice developed severe inflammation in the body, with no or weak inflammation in the antral mucosa. We used the nTx mice that developed inflammation for the following experiment. Infiltration of mononuclear cells occurred in the lamina propria of the corpus mucosa as early as 6 weeks after nTx in association with the production of autoantibodies against parietal cells (data not shown). As the inflammatory cell population expanded along the glands, the destruction of parietal cells and chief cells became prominent, resulting in glandular atrophy. However, no germinal centers were observed, and the diffusely or massively infiltrating cells consisted mainly of lymphocytes and a few other mononuclear cells, including plasma cells and macrophages. These pathological features basically remained unchanged throughout the experiment (Fig. 1a). These observations are consistent with our previous reports (12, 13, 25, 26, 31).

FIG. 1.

Histologic findings of the gastric mucosa in neonatally thymectomized (nTx) BALB/c mice with H. pylori infection. Neonatal thymectomy was performed on the 3rd day after birth. nTx mice at 6 weeks old were orally infected with H. pylori and sacrificed 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks later. (a) At the age of 18 weeks, noninfected nTx mice showed infiltration of mononuclear cells and gland atrophy characterized by loss of parietal and chief cells, with replacement by proliferating epithelial cells. Magnification, ×50. Histologic findings of nTx mice without H. pylori infection were not changed throughout the experiment. (e and f) In infected nTx mice, follicle formation was observed at 8 weeks after infection in 7 of 10 mice (P < 0.05 versus noninfected nTx mice) (e), and the body mucosa clearly showed germinal center formation at 12 weeks after infection in 6 of 10 mice (P < 0.05 versus noninfected nTx mice) (f). The photographs in panels b, c, and d show gastric histology at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after H. pylori infection in nTx mice, respectively.

After H. pylori infection, the gastric mucosa of the nTx mice did not show significant alteration for the first 2 weeks (Fig. 1b and c). At 4 weeks after infection, clusters of mononuclear cells appeared at the bottom of the lamina propria in the gastric mucosa (Fig. 1d). A distinct change in lymphoid cell infiltration was seen at 8 weeks after infection (14 weeks old, Fig. 1e): unlike noninfected nTx mice, infected mice showed a lymphoid follicle in the corpus mucosa in 7 of 10 mice (P < 0.05 versus noninfected nTx mice). At 12 weeks after infection (18 weeks old), many secondary follicles developed in 6 of 10 mice (P < 0.05 versus noninfected nTx mice) (Fig. 1f), whereas no follicular formation was observed in noninfected nTx mice throughout the experiment (Fig. 1a). As we previously reported (26), such a histologic feature observed in these infected mice resulted in no significant difference of the mononuclear cell infiltration from the uninfected mice (data not shown). There was little or no inflammation in both the noninfected and infected normal (non-nTx) mice, as described previously (26). No γδ-T-cell-receptor-positive cells could be detected among the intraepithelial lymphocytes in the gastric mucosa of either infected or noninfected nTx mice (data not shown). B220- and IgM-positive cells predominantly infiltrated in the mucosa in association with the follicle formation 12 weeks after H. pylori infection, confirming our previous study (26).

Flow cytometry.

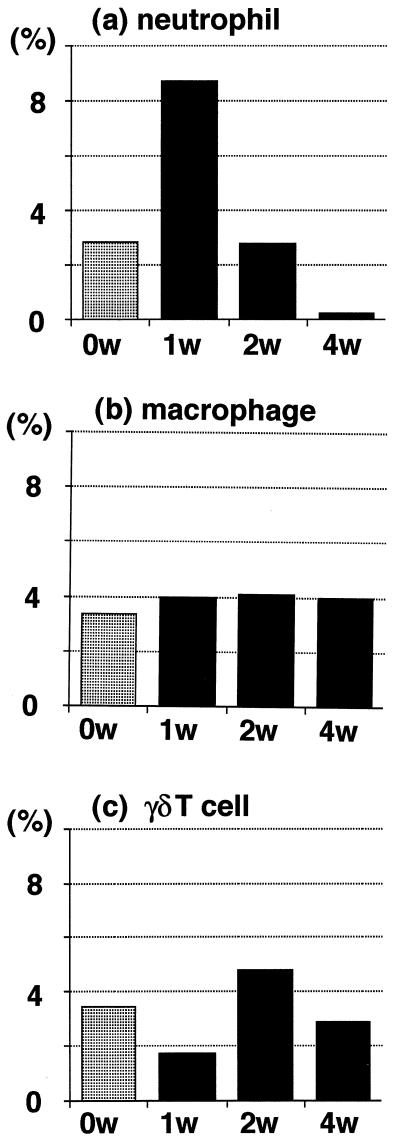

In the infected nTx mice, flow cytometric analysis demonstrated a transient but prominent increase in the number of neutrophils after 1 week (Fig. 2a). The percentages of infiltrating macrophages and γδ T cells did not change after infection (Fig. 2b and c).

FIG. 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of mononuclear cells infiltrating the gastric mucosa of nTx mice after H. pylori infection. Infected nTx mice were sacrificed 1, 2, and 4 weeks later. Infiltrating mononuclear cells were collected from the whole stomachs of three mice at each time point. (a) The panel shows that neutrophils were transiently increased at 1 week after H. pylori infection (P < 0.05 versus noninfected nTx mice; 2.7, 8.6, 2.9, and 0.3% at 0, 1, 2, and 4 weeks, respectively). Panels b and c show that the ratios of both macrophages (3.4, 4.0, 4.1, and 4.0% at 0, 1, 2, and 4 weeks) and γδ T cells (3.5, 1.8, 4.7, and 2.9% at 0, 1, 2, and 4 weeks) were not significantly changed by H. pylori infection. The data are representative of three separate experiments and are expressed as the percentage of all of the infiltrating cells.

Semiquantitative cytokine expressions by RT-PCR.

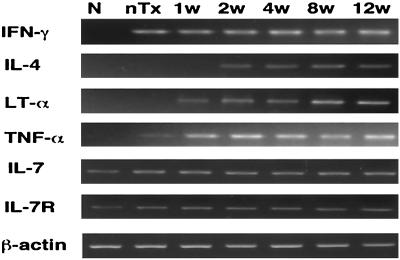

Gene expressions of IFN-γ, IL-7, and IL-7R were similarly detected by RT-PCR in both the infected and noninfected nTx mice (Fig. 3). On the other hand, weak expressions of IL-4, TNF-α and LT-α genes were detected in 1, 6, and 2 of 8 noninfected nTx mice, respectively (Table 1). However, LT-α, TNF-α, and IL-4 gene expressions started to be upregulated in all infected nTx mice from 1, 1, and 2 weeks after infection, respectively (Fig. 3); at 12 weeks after H. pylori infection expressions were significantly higher than those of noninfected nTx mice (Table 1). In normal (non-nTx) mice either with or without infection, these cytokines could not be detected (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR of various cytokine mRNAs in the gastric mucosa after H. pylori infection. IFN-γ mRNA was present in nTx mice, but its expression was not altered by H. pylori infection. LT-α, TNF-α, and IL-4 gene expressions were upregulated in all infected nTx-mice at 1, 1, and 2 weeks after infection, respectively. There were no differences in the gene expression of the IL-7 and IL-7R genes between infected and noninfected nTx mice. N, noninfected normal (non-nTx) mice; nTx, noninfected nTx mice at 18 weeks old. The designations 1w, 2w, 4w, 8w, and 12w refer to 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks, respectively, after infection in nTx mice.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of cytokine gene expressions in the stomachs of nTx mice with or without H. pylori infection as determined by RT-PCR

| Cytokine | Groupa | Positive prevalence (no. of animals positive/ total no. of animals) | Relative intensity of mRNAb ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | nTx | 8/8 | 469.00 ± 109.00 |

| nTx+Hp | 10/10 | 488.95 ± 96.23 | |

| IL-7 | nTx | 8/8 | 153.45 ± 17.97 |

| nTx+Hp | 10/10 | 109.33 ± 33.26 | |

| IL-7R | nTx | 8/8 | 404.73 ± 43.70 |

| nTx+Hp | 10/10 | 519.42 ± 61.39 | |

| IL-4 | nTx | 1/8 | 30.15 ± 32.01 |

| nTx+Hp | 8/10 | 168.80 ± 17.57 | |

| TNF-α | nTx | 6/8 | 91.34 ± 32.90 |

| nTx+Hp | 7/7 | 237.68 ± 39.73 | |

| LT-α | nTx | 2/8 | 65.93 ± 36.97 |

| nTx+Hp | 9/10 | 181.29 ± 41.61 |

nTx, thymectomized mice without H. pylori infection; nTx+Hp, thymectomized mice with H. pylori infection.

Values are means ± the standard deviations. The densities of the bands were measured by an image autoanalyzing system (Fotodyne, FOTOanalyst, and Archive ECLIPSE) and corrected by using the β-actin density of each sample. Samples were obtained from the mouse stomachs 12 weeks after H. pylori infection. For the last three pairs of values (i.e., for IL-4, TNF-α, and LT-α), the values for the infected animals were significantly different (P < 0.05) from the values for the noninfected nTx mouse group as calculated by using the Wilcoxon t test.

DISCUSSION

There are no lymphoid tissues such as lymphoid follicles or intraepithelial lymphocytes in the normal stomach (5). However, some H. pylori-positive patients develop follicular gastritis with germinal centers (6), which may be an important predisposing condition for MALToma (39). The mechanism by which follicular formation occurs in H. pylori-positive chronic gastritis is still unclear. In our histologic study, follicular gastritis was the most characteristic feature in the infected nTx BALB/c mice (26). This feature has never been observed in the noninfected nTx mice or infected normal mice in our previous (12, 25, 26, 31) and the present studies. Moreover, infection of normal mice with H. pylori, in contrast to infection of nTx mice, induced little infiltration of mononuclear cells in the gastric mucosa (26). These findings suggest that host factors play important roles in the development of gastritis and even follicular formation after H. pylori infection. Supporting this idea, recent studies with the H. felis (5, 21) or H. pylori (17) mouse model demonstrated that inflammation of the stomach was severe in C57BL/6J but weak in BALB/c mice. The C57BL/6J mouse is known to be a Th1-dominated strain for intracellular infections such as those by Leishmania major, whereas the BALB/c mouse is believed to be Th2 dominated (9). Indeed, in the case of Helicobacter infection, gastric inflammation seems to be predominantly associated with Th1 response (11, 22). It appears reasonable that H. pylori infection induced severe gastritis in nTx BALB/c mice, because the microenvironment in the stomach changes to be Th1 dominant by nTx (13, 25).

At the early stage of H. pylori infection in this study, neutrophils in the gastric mucosa transiently increased at 1 week and then decreased in a time-dependent manner. These findings confirmed that neutrophils are mainly involved in the acute phase of the reaction against H. pylori infection and not in the chronic phase (4, 23). Macrophages and γδ T cells are thought to play important roles in the local immune responses to bacterial antigens, including H. pylori (30, 34, 35). However, the distribution of macrophages and γδ T cells has been poorly explored in the H. pylori-infected gastric mucosa (8, 30, 33, 34). Our previous and present studies have shown that macrophages mainly infiltrated at the bottom of gastric mucosa of nTx mice after H. pylori infection, although their numbers and ratios did not significantly change (12, 25, 26, 31). On the other hand, γδ T cells in the gastric mucosa were not changed after infection, which suggested that γδ T cells were not mainly involved in the early stage of H. pylori-infected gastritis.

Among the infiltrating mononuclear cells, B cells increased in numbers, along with formation of the germinal center at 12 weeks after H. pylori infection in the nTx mice. Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 take important roles of maturation and proliferation of B cells (2). IL-4 knockout mice lack intestinal Peyer's patches, which suggests that the Th2 cytokines are involved in the development of constitutive lymph follicles (36). However, the actual roles and direct linkage of the Th2 responses to acquired follicular formation are still not established. In the previous study, we showed that Th2 cytokines as well as Th1 cytokines were involved in the development of follicular gastritis after long-standing H. pylori infection with respect to Th1/Th2 ratio (26). This suggested that similar to constitutive germinal centers (32), a synergistic effect of Th1 and Th2 cytokines may be important in the formation of secondary follicles in the H. pylori-infected stomach. However, it was still unclear whether additional molecules besides Th1 and Th2 cytokines are involved in these characteristic histologic changes or not. Recently, it has been shown that, in addition to Th2 cytokines, several molecules, such as TNF-α, TNF-R, LT-α/β, IL-7, and IL-7R, are involved in the development of splenic follicular dendritic cell clusters, lymph nodes, Peyer's patches, or the primary germinal centers (3, 10, 14, 15, 19, 28, 29). However, the mechanisms of organogenesis in these lymphoid organs are not identical. TNF signaling through the TNF-R is essential for the formation of secondary lymphoid tissues (29). IL-7- or IL-7R-deficient mice lack the Peyer's patches but possess the cecal and colonic patches (37). In contrast, LT-α-deficient mice completely lack germinal centers in the gastrointestinal tract, suggesting that LT-α/β may have a crucial role in the formation of germinal centers in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (3, 14). The present study showed that in addition to IL-4, a Th2-type cytokine, gene expressions of TNF-α and LT-α were upregulated in the H. pylori-infected nTx mice compared to those in noninfected nTx mice, while neither the expression of the IL-7R gene nor the expression of the IL-7 gene was changed. Taken together, these results show that Helicobacter infection can induce follicular gastritis only in mice with autoimmune gastritis, which requires Th1 cytokine-mediated process, and not in normal BALB/c mice. This indicated that the cytokine milieu induced by autoimmune gastritis might have an effect on the development of gastric secondary follicles in chronic Helicobacter infection. Recently, it has been reported that a CXC chemokine called B-cell-attracting chemokine 1 (BCA-1) in humans (18) and B-lymphocyte chemoattractant (BLC) in mice (7) is important for the development of B-cell areas of secondary lymphoid tissues. Mazzucchelli et al. investigated whether BCA-1 was induced in chronic H. pylori gastritis and involved in the formation of lymphoid follicles and MALToma (20). Although we did not investigate BLC in the present study, LT and TNF were shown to have a regulatory role in the upstream of BLC (24). Therefore, it is reasonable that LT and TNF are also key molecules in the development of the lymphoid follicles in the stomach.

In conclusion, the cytokine milieu induced by autoimmune gastritis might and cooperative roles of LT-α, TNF-α, and Th1 and Th2-type immune responses may be involved in the development of gastric secondary follicles by H. pylori infection. Further studies are needed to clarify the precise mechanism for the acquired formation of germinal centers in the stomach by H. pylori infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research (C) from the Ministry of Culture and Science of Japan (09670543), a grant-in-aid for Research for the Future from The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS-RFTF97I00201), and Research Funds from the Japanese Foundation for Research and Promotion of Endoscopy (JFE-1997).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi S, Yoshida H K, Honda K, Maki K, Saijo K, Ikuta K, Saito T, Nishikawa S. Essential role of IL-7 receptor alpha in the formation of Peyer's patch anlage. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choe J, Kim H, Armitage R J, Choi Y S. The functional role of B cell antigen receptor stimulation and IL-4 in the generation of human memory B cells from germinal center B cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:3757–3766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Togni P D, Goellner J, Ruddle N H, Streeter P R, Fick A, Mariathasan S, Smith S C, Carlson R, Shornick L P, Strauss-Schoenberger J. Abnormal development of peripheral lymphoid organs in mice deficient in lymphotoxin. Science. 1994;264:703–707. doi: 10.1126/science.8171322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon M F. Campylobacter pylori and chronic gastritis. In: Rathbone B J, Heatley R V, editors. Campylobacter pylori and gastroduodenal disease. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific; 1989. pp. 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enno A, O'Rourke J L, Howlett C R, Jack A, Dixon M F, Lee A. MALToma-like lesions in the murine gastric mucosa after long-term infection with Helicobacter felis—a mouse model of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric lymphoma. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:217–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genta R M, Wentzell H H, Graham D Y. Gastric lymphoid follicles in Helicobacter pylori infection: frequency, distribution and response to triple therapy. Hum Pathol. 1993;342:577–583. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan M D, Ngo V N, Ansel K M, Ekland E H, Cyster J G, Williams L T. A B-cell-homing chemokine made in lymphoid follicles activates Burkitt's lymphoma receptor-1. Nature. 1998;391:799–803. doi: 10.1038/35876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatz R A, Meimarakis G, Bayerdirffer E, Stolte M, Kirchner T, Enders G. Characterization of lymphocytic infiltrates in Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:222–228. doi: 10.3109/00365529609004870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinzel F P, Sadic M D, Holaday B J, Coffman R L, Locksley R M. Reciprocal expression of interferon gamma or interleukin 4 during the resolution or progression of murine leishmaniasis. Evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1989;169:59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hikida M, Nakayama Y, Yamashita Y, Kumazawa Y, Nishikawa S, Ohmori H. Expression of recombination activating genes in germinal center B cells: involvement of interleukin 7 (IL-7) and the IL-7 receptor. J Exp Med. 1998;188:365–372. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itoh T, Wakatsuki Y, Yoshida M, Usui T, Matsunaga Y, Kaneko S, Chiba T, Kita T. The vast majority of gastric T cells are polarized to produce T helper 1 type cytokines upon antigenic stimulation despite the absence of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:560–570. doi: 10.1007/s005350050373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones C M, Callaghan J M, Gleeson P M, Mori Y, Masuda T, Toh B H. The parietal cell autoantibodies recognized in neonatal thymectomy-induced murine gastritis are the α and β subunits of the gastric proton pump. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katakai T, Mori K J, Masuda T, Shimizu A. Differential localization of Th1 and Th2 cells in autoimmune gastritis. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1325–1334. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.9.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koni P A, Sacca R, Lawton P, Browning J L, Ruddle N H, Flavell R A. Distinct roles in lymphoid organogenesis for lymphotoxin α and β revealed in lymphotoxin α-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;6:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korner H, Cook M, Riminton D S, Lemckert F A, Hoek R M, Ledermann B, Kontgen F, Fazekas de St. Groth B, Sedgwick J D. Distinct roles for lymphotoxin-alpha and tumor necrosis factor in organogenesis and spatial organization of lymphoid tissue. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2600–2609. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuipers E J, Uyterlinde A M, Pena A S, Roosendaal R, Pals G, Nelis G F, Festen H P, Meuwissen S G. Long-term sequelae of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Lancet. 1995;345:1525–1528. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee A, O'Rourke J L, De Ungiria M C, Robertson B, Daskalopulos G, Dixon M F. A standardized mouse model of Helicobacter pylori infection: introducing the Sydney strain. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1386–1397. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Legler D F, Loetscher M, Roos R S, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Moser B. B cell-attracting chemokine 1, a human CXC chemokine expressed in lymphoid tissues, selectively attracts B lymphocytes via BLR1/CXCR5. J Exp Med. 1998;187:655–660. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto M, Marianthasan S, Nahm H M, Baranyay F, Peschon J J, Chaplin D D. Role of lymphotoxin and the type I TNF receptor in the formation of germinal centers. Science. 1996;271:1289–1291. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazzucchelli L, Blaser A, Kappeler A, Schrli P, Laissue J A, Baggiolini M, Uguccioni M. BCA-1 is highly expressed in Helicobacter pylori-induced mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue and gastric lymphoma. J Exp Med. 1998;104:R49–R54. doi: 10.1172/JCI7830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohammadi M, Redkine R, Nedrud J, Czinn S. Role of the host in pathogenesis of Helicobacter-associated gastritis: H. felis infection of inbred and congenic mouse strains. Infect Immun. 1996;64:238–245. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.238-245.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammadi M, Nedrud J, Redline R, Lycke N, Czinn S J. Murine CD4 T-cell response to Helicobacter infection: TH1 cells enhance gastritis and TH2 cells reduce bacterial load. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1848–1857. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mooney C, Keenan J, Munster D, Wilson I, Allardyce R, Bagshaw P, Chapman B, Chadwick V. Neutrophil activation by Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1991;32:853–857. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.8.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ngo V N, Korner H, Gunn M D, Schmidt K N, Riminton D S, Cooer M D, Browning J L, Sedgwick J D, Cyster J G. Lymphotoxin α/β and tumor necrosis factor are required for stromal cell expression of homing chemokine in B and T cell area of the spleen. J Exp Med. 1999;189:403–412. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishio A, Hosono M, Watanabe Y, Sakai M, Okuma M, Masuda T. A conserved epitope on H+/K+-adenosine-triphosphatase of parietal cells discerned by a murine gastritogenic T cell clone. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1408–1414. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oshima C, Okazaki K, Matsushima Y, Sawada M, Chiba T, Takahashi K, Hiai H, Katakai T, Kasakura S, Masuda T. Induction of follicular gastritis following postthymectomy autoimmune gastritis in Helicobacter pylori-infected BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 2000;68:100–106. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.100-106.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsonnet J, Friedmann G D, Vandersteen D P, Chang Y, Vogelman J H, Orentreich N, Sibley R K. Helicobacter pylori infection and risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Episkopou V, Kollias G. Immune and inflammatory responses in TNF alpha-deficient mice: a critical requirement for TNF alpha in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1397–1411. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Grell M, Pfizenmaier K, Bluethmann H, Kollias G. Peyer's patch organogenesis is intact yet formation of B lymphocyte follicles is defective in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice deficient for tumor necrosis factor and its 55-kDa receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6319–6323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roark C E, Vollmer M K, Campbell P A, Born W K, O'Brien R L. Response of a γδ T cell receptor invariant subset during bacterial infection. J Immunol. 1996;156:2214–2220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakaguchi S, Fukuma K, Kuribayashi K, Masuda T. Organ-specific autoimmune diseases in mice by elimination of T cell subset. 1. Evidence for the active participation of T cells in natural self-tolerance: deficit of a T cell subset as a possible cause of autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1985;161:72–87. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Secord E A, Rizzo L V, Barroso E W, Umetsu D T, Thorbecke G J, DeKruyff R H. Reconstitution of germinal center formation in nude mice with Th1 and Th2 clones. Cell Immunol. 1996;174:173–179. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seifarth C, Deusch K, Reich K, Classen M. Local cellular immune response in Helicobacter pylori associated type B gastritis—selective increase of CD4+ but not of γδ T cells in the immune response to H. pylori antigens. Z Gastroenterol. 1996;34:215–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seifarth C, Funk A, Reich K, Dahne I, Classen M, Deusch K. Selective increase of CD4+ and CD25+ T cells but not of γ/δ T cells in H. pylori-associated gastritis. In: Mestecky J, editor. Advances in mucosal immunology. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press, Inc.; 1995. pp. 931–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stolte M, Eidt S. Helicobacter pylori and the evolution of gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;214:13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vajdy M, Kosco-Vibois M H, Kopf M, Köhler G, Lycke N. Impaired mucosal immune respose in interleukin 4-targeted mice. J Exp Med. 1995;181:41–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walsh J H, Peterson W L. The treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in the management of peptic ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:984–991. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510123331508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe T, Tada M, Nagai H, Sasaki S, Nakao M. Helicobacter pylori infection induces gastric cancer in Mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wotherspoon A C, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon M R, Isaacson P G. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet. 1991;338:1175–1176. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]