Abstract

Treatment of the double nuclear complex 1a, di-μ-cloro-bis[N-(4-formylbenzylidene)cyclohexylaminato-C6, N]dipalladium, with Ph2PCH2CH2)2PPh (triphos) and NH4PF6 gave the single nuclear species 2a, 1-N-(cyclohexylamine)-4-N-(formyl)palladium(triphos)(hexafluorophasphate). Reaction of 2a with Ph2PCH2CH2NH2 in refluxing chloroform via a condensation reaction of the amine and formyl groups to produce the C=N double bond, gave 3a, 1-N-(cyclohexylamine)-4- N-(diphenylphosphinoethylamine)palladium(triphos)(hexafluorophasphate); a potentially bidentate [N,P] metaloligand. However, attempts to coordinate a second metal by treatment of 3a with [PdCl2(PhCN)2] were to no avail. Notwithstanding, complexes 2a and 3a left to stand in solution spontaneously self-transformed to give in either case the double nuclear complex 10, 1,4-N,N-terephthalylidene(cyclohexilamine)-3,6-[bispalladium(triphos)]di(hexafluorophosphate), after undergoing further metalation of the phenyl ring, then bearing two mutually trans [Pd(Ph2PCH2CH2)2PPh)-P,P,P] moieties: an unprecedented and serendipitous result indeed. On the other hand, reaction of the double nuclear complex 1b, di-μ-cloro-bis[N-(3-formylbenzylidene)cyclohexylaminato-C6, N]dipalladium, with Ph2PCH2CH2)2PPh (triphos) and NH4PF6 gave the single nuclear species 2b, 1-N-(cyclohexylamine)-4-N-(formyl)palladium(triphos)(hexafluorophasphate), Treatment of 2b with H2O/glacial MeCOOH gave cleavage of the C=N double bond and of the Pd···N interaction, yielding 5b, isophthalaldehyde-6-palladium(triphos)hexafluorophosphate, which then reacted with Ph2P(CH2)3NH2 to yield complex 6b, N,N-(isophthalylidene(diphenylphosphinopropylamine)-6-(palladiumtriphos)di(hexafluorophosphate), with two pairs of non-coordinated nitrogen and phosphorus donor atoms. Treatment of 6b with [PdCl2(PhCN)2], [PtCl2(PhCN)2], or [PtMe2(COD)] gave the new double nuclear complexes 7b, 8b and 9b, palladiumdichloro-, platinumdichloro- and platinumdimethyl[N,N-(isophthalylidene(diphenylphosphinopropylamine)-6-(palladiumtriphos)(hexafluorophosphate)-P,P], respectively, showing the behavior of 6b as a palladated bidentate [P,P] metaloligand. The complexes were fully characterized by microanalysis, IR, 1H, and 31P NMR spectroscopies, as appropriate. The X-ray single-crystal analyses for compounds 10 and 5b have been previously described as the perchlorate salts by JM Vila et al.

Keywords: palladacycles, imines, catalysis, Suzuki, cross coupling

1. Introduction

The organometallics known as cyclometallated complexes [1,2], with special emphasis focused on the palladium derivatives, i.e., the palladacycles [3,4,5], have developed over the years into a large group of species. Their structural-related characteristics, reactivity patterns and most of all their applications have brought them to the highest echelon of research. It is noteworthy to mention their usage as metalomesogens [6] as antineoplastic substances [7,8] and in synthetic chemistry, where they have shown a paramount role as catalysts and pre-catalysts [9,10,11,12,13,14] inclusive of the especial case of the phosphorus donor ligands designed by Hermann et al. [15,16] and of the pioneering work by Suzuki [17,18]. As far as their reactivity is concerned, it derives fundamentally from the different nature of the bonds on the metal atom, i.e., the M-C and M-Y (Y = donor atom) bonds, which allow a great variety of processes ranging from insertions [19] to reactions with a rather large number of nucleophiles [20,21], offering a plentiful and alluring chemistry. In the case of palladacycles derived from imines the stereochemistry of the four-coordinated palladium(II) atom is the characteristic square-planar geometry; notwithstanding, five- and six-coordinate palladium complexes have also been reported [22,23,24]. Precisely because the preferred geometry for palladium is square-planar, one would expect that with tridentate polyphosphanes, namely (Ph2PCH2CH2)2PPh (triphos), an uncoordinated phosphorus atom to remain upon binding of the phosphane to palladium. Whereupon they should then be suitable for coordination to another metal and give way to new heterobimetallic compounds. However, this is not the case as we have previously described in the reaction of triphos with dinuclear (μ-Cl)2-bridged palladacycles containing imine, bis(imine) and the related azobenzene ligands. In the resulting complexes, all three phosphorus donors are bonded to the metal to give complexes in which the palladium-nitrogen bond distance; though slightly longer than the value expected for a true Pd-N bond 2.23(4) Å, this suggests pentacoordination of the metal atom, with the latter in a distorted trigonal bipyramid geometry, as depicted in Scheme 1.

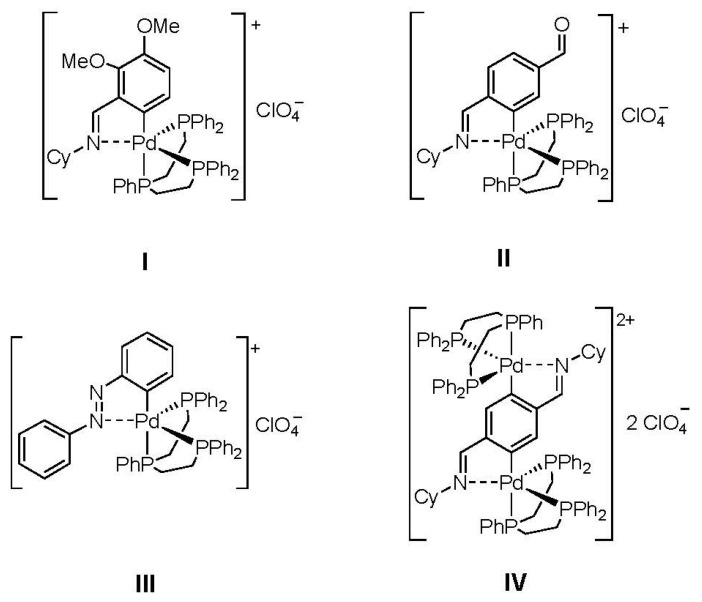

Scheme 1.

Examples of single-nuclear, (I–III), and double-nuclear, (IV), pentacoordinated palladium complexes.

Thus, what began as a fortuitous finding resulted in a systematic behavior of these palladacycles was then extended to other organic metalated moieties [25]. More recently, examples of related five-coordinate palladium complexes have appeared with triphosphanes [26], triptycene-based ligands, an example of how especially designed ligands may induce five-coordination [27], and in oxime palladacycles with simultaneous bonding of m-dppe and dppe-P,P to the palladium center [28]. Yet, the story does not end here, since in our efforts to study new patterns of reactivity in single-nuclear palladacycles containing triphos, we have found that a double-nuclear complex is serendipitously obtained; in fact, two different complexes gave the same structure after recrystallization. This is a more than surprising result that has led us to change the initial course of this manuscript by focusing our efforts on the search for a satisfactory explanation, as well as on the related chemistry of the initial palladacycles themselves. Herein, we report the route leading to this conversion along with a tentative explanation for this chemistry.

2. Results

For the convenience of the reader, the compounds and reactions are shown in Scheme 2 and Scheme 3. The compounds described in this paper were characterized by elemental analysis (C,H,N) and by IR and 1H, 31P–{1H} NMR spectroscopy (data in Section 3), as well as by X-ray diffractometric analysis (5b, 10). The cyclometalated complexes 1a [10], 1b [11], 2a, 2b [12] have been reported previously; 2a, 2b as the perchlorate salts.

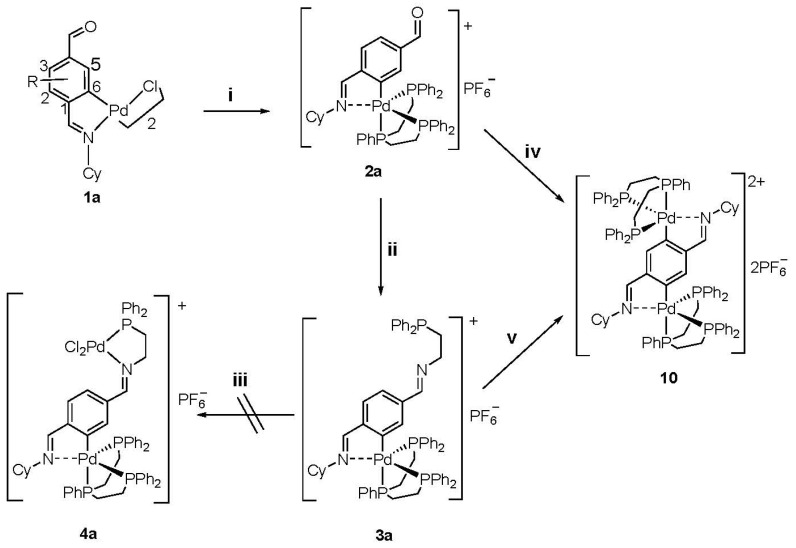

Scheme 2.

(i) triphos/NH4PF6; (ii) Ph2P(CH2)2NH2; (iii) [PdCl2(PhCN)2]; (iv) and (v) left to stand.

Scheme 3.

(i) triphos/NH4PF6; (ii) H2O/glacial MeCOOH; (iii) Ph2P(CH2)3NH2; (iv), (v) [PdCl2(PhCN)2], [PtCl2(PhCN)2], [PtMe2(COD)] as appropriate (there are no b type analogues of 3a and 4a).

The aim of this paper was to show that palladacycles bearing an uncoordinated formyl group could be conveniently transformed into either bidentate-[P,N] or bidentate-[P,P] palladium metaloligands. The first step would be to hinder further reactions of the palladium center, for which purpose the triphos derivatives were chosen; this tightly holds the metal by simultaneous bonding to the metallated phenyl carbon and to the three phosphorus donors of the tridentate phosphane ligand. There are then two possibilities: the first is the addition of new [P,N] donors by direct restoration of the C=N bond with a convenient aminophosphane; the second one is cleavage of the C=N double bond within the metallacycle ring, to give a palladium complex with two formyl moieties, and the addition of two sets of [P,N] donor atoms via the formation of two new C=N bonds. In the latter case, one could expect bis(bidentate-[P,N]) or bidentate-[P,P] coordination, the outcome depending on the length of the aminophosphane ligand. This was achieved (in part) as we describe, vide infra, together with a new and most striking result that somewhat changed our initial research pathway. Thus, treatment of precursor 1a with Ph2PCH2CH2)2PPh (triphos) and NH4PF6 produced the single nuclear complex 2a, which was fully characterized (see Experimental). Then, treatment of complex 2a with Ph2PCH2CH2NH2 in boiling chloroform for 8 h gave 3a. The IR spectrum showed absence of the υ(C=O) stretch and two υ(C=N) bands at 16,371,623 cm−1; the second corresponds to the C=N moiety bonded to the metal atom [29,30]. The 1H NMR spectrum showed two singlet resonances at 8.21, 8.13 ppm; the first (higher frequency) was assigned to the free HC=N proton and the second (lower frequency) to the HC=N proton of the cyclometallated ring [31]. An apparent triplet resonance at 5.83 was assigned to the H5 proton showing coupling to the phosphorus nucleus trans to carbon with 4J(HH) ≈ 4J(PH). The new metaloligand was reacted with PdCl2 or PtCl2 in CHCl3 at room temperature in the hope of producing complexes of type 4a, but to no avail. However, a solution of 2a, on the one hand, and the subsequent solution of 3a, on the other, left to stand for recrystallization by slow evaporation of a chloroform solution gave an unprecedented and serendipitous result which in both cases produced crystallization of the same PF6 salt of a double-nuclear palladacycle, 10; a structure altogether distinct from the one expected on the basis of NMR data. This modified our initial objectives, prompting us to seek a plausible explanation for this finding, and left the pursuit of yet new metaloligands for the last part of the manuscript (vide infra).

Likewise, reaction of the precursor 1b with Ph2PCH2CH2)2PPh (triphos) and NH4PF6 produced the single nuclear complex 2b, which was fully characterized (see Experimental). Treatment of 2b with a mixture of acetic acid/water gave 5b (see Experimental).

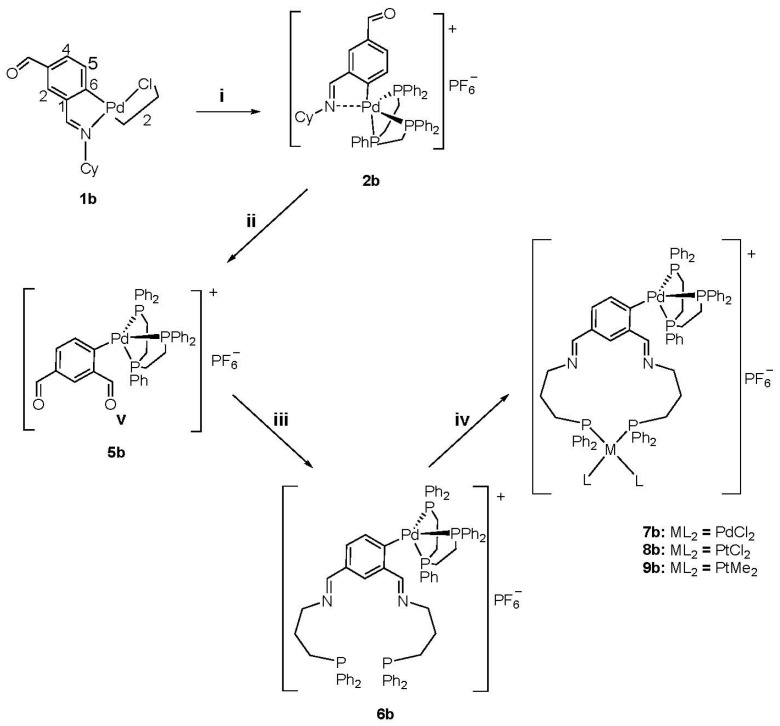

A crystal structural analysis for complex 5b could be performed. Thus, suitable crystals of 5b were grown by slowly evaporating a chloroform solution of the compound. Crystal data are given in the Supporting Information. The ORTEP illustration of complex 5b is shown in Figure 1. The compound crystalizes in the P21/n space group with two acetone solvent molecules. The crystals consist of discrete molecules separated by van der Waals distances.

Figure 1.

ORTEP drawing of complex 5b with thermal ellipsoid plot shown at 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms and PF6 counterions have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (˚) for 5b: Pd(1)-C(1) 2.080(3), Pd(1)-P(1) 2.3098(8), Pd(1)-P(2) 2.2762(8), Pd(1)-P(3) 2.3334(8), P(2)-Pd(1)-P(1) 83.97(3), P(2)-Pd(1)-P(3) 83.48(3) P(1)-Pd(1)-P(3) 163.65(3), C(1)-Pd(1)-P(3) 97.36(8), C(1)-Pd(1)-P(2) 176.84(9), C(1)-Pd(1)-P(1) C6 Pd1 P1 94.63(8). Selected crystallographic data: a, 13.1305(4); b, 14.8772(4); c, 20.4043(7) Å. β, 102.551(1)°. Volume 3890.6(2) Å3. Z = 2. 2Θ range for data collection/° 4.92 to 52.74. Reflections collected, 50817. Independent reflections, 7952 [Rint = 0.0481, Rsigma = 0.0303]. Final R indexes [I > = 2σ (I)] R1 = 0.0407, wR2 = 0.0891. Final R indexes [all data] R1 = 0.0501, wR2 = 0.0937.

The four coordinated palladium atom is bonded to the phenyl carbon atom of the metallated phenyl ring, and to three phosphorus atoms of the triphos lignad. The coordination sphere of the palladium may be described as slightly distorted square-planar; the palladium atom is 0.136 from the mean coordination plane [C(6), P(1), P(2), P(3)]. The angles between adjacent atoms in the coordination sphere of palladium are fairly close to the expected value of 90° with the smaller values for the bite angles for the tridentate ligand [P(1)-Pd(1)-P(2) = 83.97° and P(2)-Pd(1)-P(3) = 83.48°] consequent upon chelation and the sum of angles at palladium is 359.44°; the palladium coordination plane [Pd(1), C(6), P(1), P(2), P(3)] and the metalated phenyl ring are at 76.16°. The C(2)-C(7)-O(1) oxygen is directed toward the palladium atom; however, the Pd(1)-O(1) distance of 2.780 Å precluded any interaction between both atoms.

Treatment of 5b with two equivalents of 3-diphenylphosphinopropylamine, Ph2PCH2CH2CH2NH2, gave 6b as an air-stable solid (see Experimental): a novel tetradentate [N,P,N,P] metaloligand. The IR and NMR spectra showed the absence of the υ(C=O) stretches and of the HC=O resonances, respectively. Instead, two bands at 1639 and 1625 cm−1 were assigned to the υ(C=N) vibrations in the IR spectrum. The 1H NMR spectrum showed two resonances at 8.03 and 7.97 ppm ascribed to the two non-equivalent HC=N protons. Several coordination possibilities arise, considering there are four new donor atoms; however, attempts to prepare complexes inducing [N,P,N,P] tetracoordination or alternatively bis(bidentate-[P,N]) coordination failed, and only compounds with 6b as bidentate-[P,P] metaloligand could be achieved. Thus, reaction of 6b with [PdCl2(PhCN)2], [PtCl2(PhCN)2] or [PtMe2(COD)] gave the new dinuclear complexes 7b-9b, as air-stable solids which were fully characterized (see Experimental). The most salient feature of the NMR spectra of 7b–9b as opposed to 6b was the downfield shift of the 31P resonance for the non-coordinated PPh2 donors from −18.3 (6b) ppm to 17.9 (7b), −4.9 (8b) and 18.0 (9b). The latter two also showed the phosphorus coupling to the platinum nucleus, [J(PtP) = 3296] and [J(PtP) = 2426], respectively.

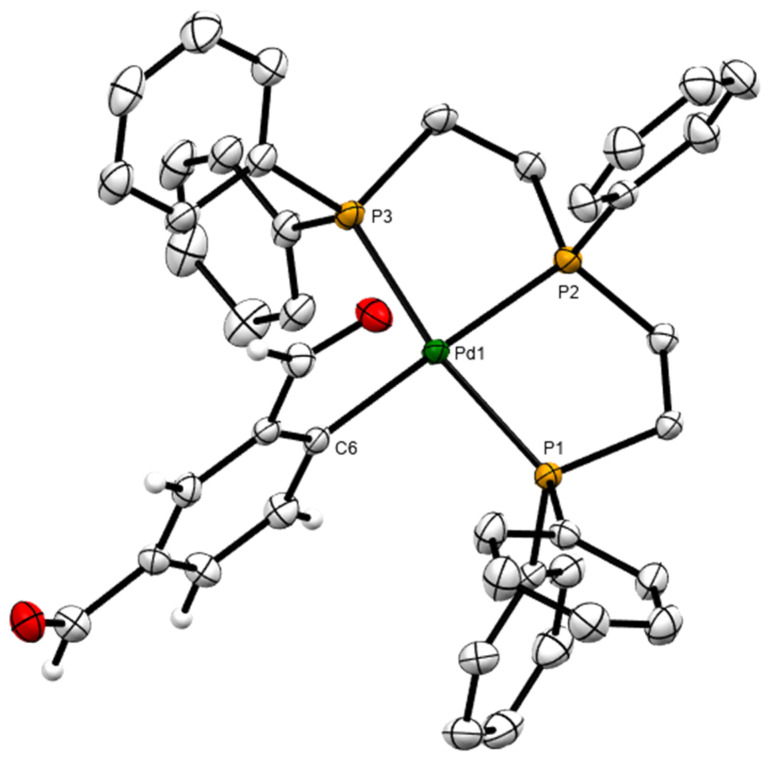

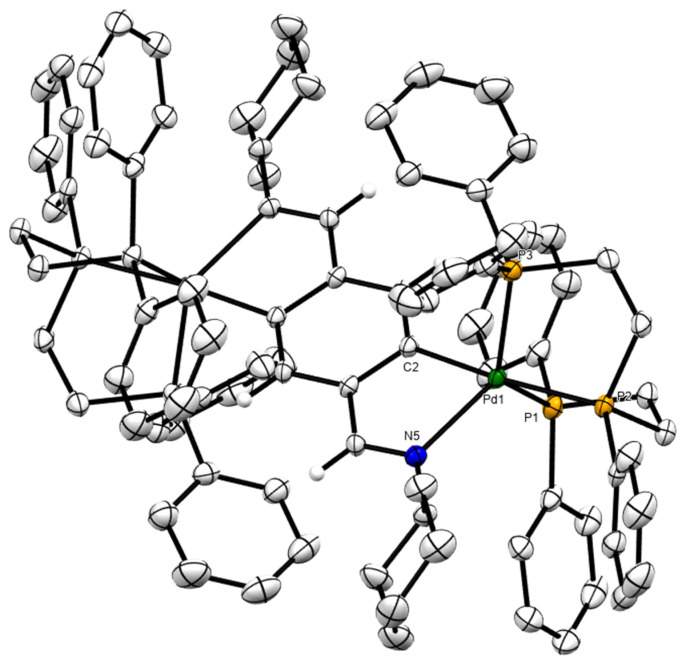

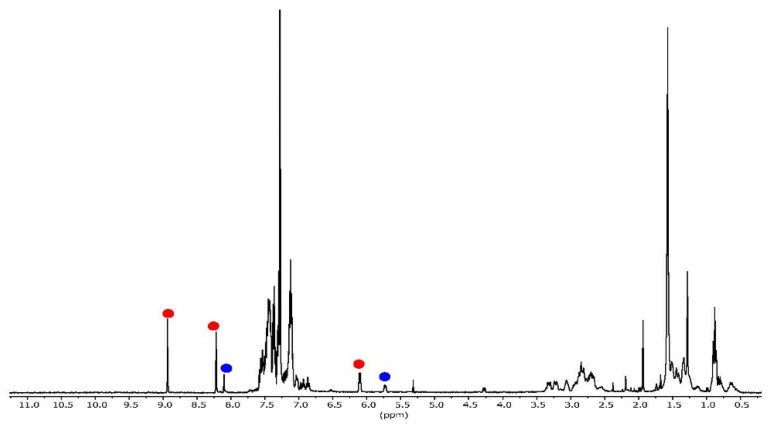

The molecular structure of 10 contains a discrete centrosymmetric dinuclear cation of [{(Ph2PCH2CH2)2PPh-P,P,P}Pd{N(Cy) = (H)C}C6H2{C(H) = N(Cy)}Pd{(Ph2PCH2-CH2)2-PPh-P,P,P}]2+ (half of the cation per asymmetric unit) and two hexafluorophosphate ions (crystal data are given in the Supporting Information; the ORTEP illustration of complex 10 is shown in Figure 2). The cation is analogous to the one prepared and discussed by us earlier as the ClO4 salt [25]; therefore, we did not consider it necessary to discuss the structure again. Nevertheless, an important point should be considered here in relation to the Pd···N distance that marks the penta-coordination environment on the palladium atom namely 2.2869(19) (structure from compound 2a) and 2.296 Å (structure from compound 3a), being less than our previous finding of 2.338 Å [25], and it is, to the best of our knowledge, the shortest distance known for this type of compounds, and very close the palladium-nitrogen bond length found in an authentic pentacoordinated palladium(II) complex of 2.23(2) Å [32]. To seek a plausible explanation for this, let us say irrefutable crystallographic results, we reasoned that formation of complex 10 requires activation of a second phenyl C-H bond, with metallation by a Pd(triphos) moiety and condensation of a cyclohexylamine to the formyl group; additionally, it would be expected that the presence of trace amounts of acid and/or water should facilitate the process. Likewise, to check that this is not a one-time reaction, compound 2a was left to stand in CDCl3 in an NMR tube, whereupon resonances other than those expected seemed to slowly dawn within the first 24 h advocating evolution of a novel compound. Then, the CDCl3 NMR solution was left to stand further upon which single-crystals appeared; an X-ray crystallographic analysis showed them to be compound 10. Initially, the 1H NMR spectra showed a mixture of two products assignable to complex 2a and an emerging compound 10. Thus, resonances of circa 9.0, 8.5 and 6.2 ppm were assigned to the HC=O, HC=N and H5 protons, respectively, for 2a (Figure 3, red circles), and new resonances of circa 8.2 and 5.7 ppm were assigned to the HC=N and H5 protons, respectively, for 10 (Figure 3, blue circles).

Figure 2.

ORTEP drawing of complex 10 (from 2a) with thermal ellipsoid plot shown at 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms for the metalated phenyl ring and C=N groups are shown; the remaining hydrogen atoms and PF6 counterions have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (°) for 10: Pd(1)-C(2) 2.046(2), Pd(1)-N(5) 2.2869(19), Pd(1)-P(1) 2.3127(6), Pd(1)-P(2) 2.3416(6), Pd(1)-P(3) 2.3147(6), P(2)-Pd(1)-P(1) 85.06(2) P(2)-Pd(1)-P(3) 84.22(2) P(1)-Pd(1)-P(3) 122.09(2) P(2)-Pd(1)-N(5) 107.21(5) N(5)-Pd(1)-P(3) 120.29(5) P(1)-Pd(1)-N(5) 116.58(5) C(2)-Pd(1)-P(3) 93.36(6) C(2)-Pd(1)-P(2) 174.27(6) C(2)-Pd(1)-P(1) 91.93 (6) C(2)-Pd(1)-N(5) 78.50(8). Selected crystallographic data: a, 11.6509(4); b, 22.6116(9); c, 15.5974(7) Å. β, 96.339(1)°. Volume 4083.9(3) Å3. Z = 2. 2Θ range for data collection/° 4.52 to 52.74. Reflections collected, 86,534. Independent reflections, 8351 [Rint = 0.0539, Rsigma = 0.0256]. Final R indexes [I >= 2σ (I)] R1 = 0.0384, wR2 = 0.0903. Final R indexes [all data] R1 = 0.0460, wR2 = 0.0945.

Figure 3.

1H NMR plot for the 2a→10 shift at r.t. at room temperature. Compound 2a, red circles; compound 10, blue circles.

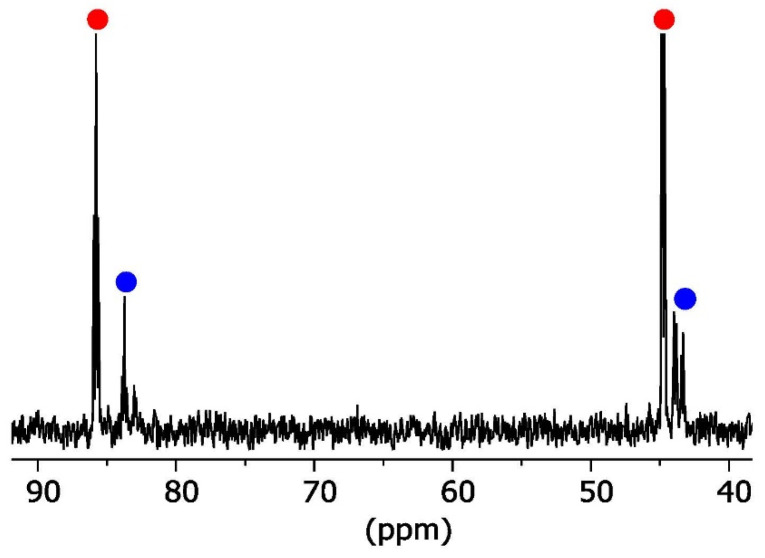

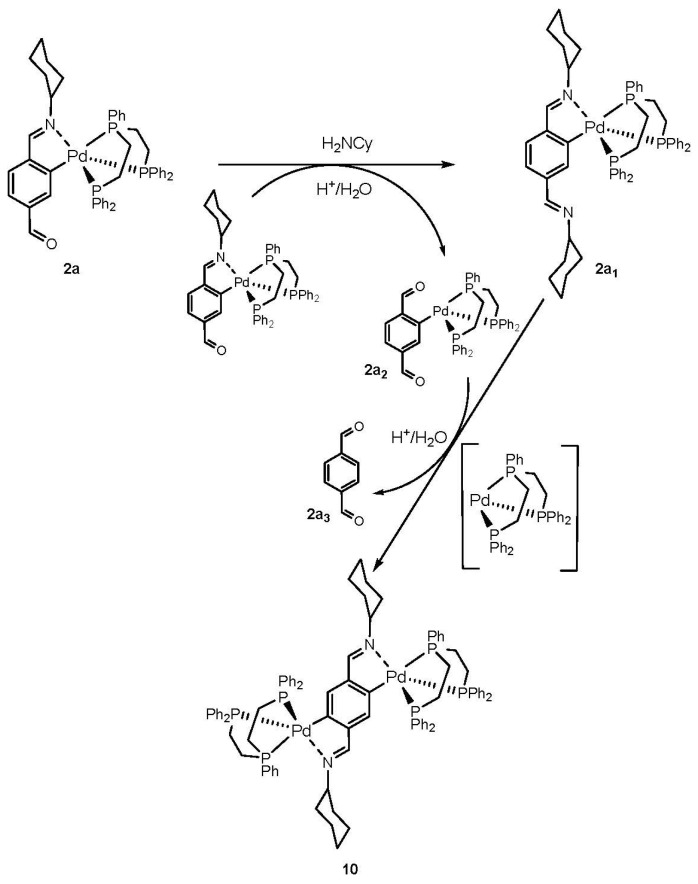

Additionally, the 31P{H} NMR spectrum also showed triplet and doublet resonances assignable to compound 2a, circa 86 and 45 ppm, respectively (Figure 4, red circles), plus another triplet resonance at circa 82 ppm, and two doublets at circa 43 ppm (Figure 4, blue circles), which were assigned to the central 31P nucleus and to the two inequivalent phosphorous, respectively, for compound 10. This transformation was even more apparent in time and intermediate species could also be detected, especially in the 31P NMR spectra and tentatively assigned (Figure 4). Therefore, following these experimental observations and considering that it is well known that commercial solvents, inclusive of NMR solvents, contain traces of acid and water, as is the case with CHCl3 and CDCl3, and most important of all the irrefutable evidence of crystal formation of the dinuclear palladium complex, we very tentatively propose the following mechanism for this transformation, an unprecedented reactivity pattern, Scheme 4. The first step is hydrolysis of the C=N double bond in compound 2a by trace acid/water producing the diformyl palladated species 2a2 and cyclohexylamine; the latter may undergo condensation with the HC=O group in 2a to give 2a1. Species 2a2 undergoes de-metallation liberating terephthalaldehyde, 2a3, and the electrophile Pd(triphos), which activates the phenyl C-H bond in 2a1 metallating the aromatic ring to yield the double-nuclear complex 10. We also suggest that solvent coordination may possibly stabilize the intermediate species.

Figure 4.

31P NMR plot for the 2a→10 shift at room temperature. Compound 2a, red circles; compound 10, blue circles.

Scheme 4.

Diagram for a plausible mechanism for the formation of compound 10 (from 2a).

3. Experimental Methods

3.1. General Procedures

Solvents were purified by standard methods [33]. The reactions were carried out under dry nitrogen. The triphosphine (Ph2PCH2CH2)2PPh (triphos), 2-diphenyl-phosphinoethanoamine, Ph2P(CH2)2NH2 and 3-diphenylphosphinopropanoamine Ph2P(CH2)3NH2 were purchased from Aldrich-Chemie. PdCl2, PtCl2 and PtMe2(COD) were purchased from commercial sources. Elemental analyses were performed with a Thermo Finnigan elemental analysis, model Flash 1112. IR spectra were recorded on Jasco model FT/IR-4600 spectrophotometer. 1H NMR and spectra in solution were recorded in acetone−d6 or CDCl3 at room temperature on Varian Inova 400 spectrometers operating at 400 MHz using 5 mm o.d. tubes; chemical shifts, in ppm, are reported downfield relative to TMS using the solvent signal as reference (acetone−d6 δ 1H: 2.05 ppm, CDCl3 δ 1H: 7.26 ppm). 31P NMR spectra in solution were recorded in acetone−d6 or CDCl3 at room temperature on Varian Inova 400 spectrometer operating at 162 MHz using 5 mm o.d. tubes and are reported in ppm relative to external H3PO4 (85%). Coupling constants are reported in Hz. All chemical shifts are reported downfield from standards. The preparation of the cyclometalated complexes 1a [10], 1b [11], 2a, 2b [12] has been reported previously; 2a, 2b as the perchlorate salts.

3.2. Preparation of the Complexes

3.2.1. Synthesis of 3a

Compound 2a (55 mg, 0.056 mmol) and 2-diphenylphosphinoethanoamine (14.90 mg, 0.065 mmol) were refluxed in chloroform (20 cm3) under argon for 3 h in a Dean–Stark equipment. After cooling to room temperature, the resulting solution was reduced to low volume. Then, after addition of n-hexane, the solid formed was filtered off and dried. Yield: 56.2 mg, 85%. Anal. found: C, 63.0; H, 5.3; N, 2.4. C62H63F6N2P4Pd requires C, 63.1; H, 5.4; N, 2.4%. IR: u(C=N) 1625m,1603m cm−1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm, J Hz): 8.12 [s, 1H, HC=N], 6.81 [d, 1H, H2, J(PHH) = 7.3], 6.7 [d, 1H, H3, J(HH) = 7.3;] 6.04 [d, 1H, H5, J(PH) = 7.3]. 31P-{1H} NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm) 83.5 [t, 1P, J(PP) = 25.0 Hz], 42.7 [d, 2P].

3.2.2. Synthesis of 5b

Compound 2b (55 mg, 0.056 mmol) and water (10 cm3) were added in glacial acetic acid (15 cm3) and the resulting mixture was stirred for 48 h at 25 °C. Then, the acetic acid was removed under reduced pressure and extracted with dichloromethane. After drying with anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtering and reducing the solvent volume, a yellow solid was obtained, which was recrystallized from dichloromethane/hexane. Yield: 42.20 mg, 82%. Anal. found: C, 54.7; H, 4.1. C42H38F6O2P4Pd requires C, 54.9; H, 4.2. IR: u(C=O) 1683s, 1659 s cm−1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm, J Hz): 9.83, 9.66 [s, 2H, HC=O], 7.79[s, 1H, H2], 6.96[d, 1H, H4, J(HH) = 7.0], 6.54[dd, 1H, H5, J(PH) = 6.6]. 31P-{1H} NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm) 82.7 [t, 1P, J(PP) = 24.8 Hz], 41.6 [d, 2P].

3.2.3. Synthesis of 6b

Compound 6b was synthesized from 5b (40 mg, 0.044 mmol) and 2-diphenyl-phosphinopropanoamine (21.41 mg, 0.088 mmol) following a similar procedure to that for 3a but using 1:2 molar ratio. Yield: 43.15 mg, 75%. Anal. found: C, 66.0; H, 5.3; N, 2.4. C72H70F6N2P4Pd requires C, 66.1; H, 5.4; N, 2.4%. IR: u(C=N) 1639 m,1625 m cm−1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm, J Hz): 8.03, 7.97 [s, 2H, HC=N], 7.0 [s, 1H, H2], 6.7 [d, 1H, H4, J(HH) = 7.5] 6.04 [dd, 1H, H5, J(PH) = 7.4]. 31P-{1H} NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm) 89.0 [t, 1P, J(PP) = 25.0 Hz], 41.7 [d, 2P], -18,3 [s, 2P].

3.2.4. Synthesis of 7b

Compound 6b (40 mg, 0.031 mmol) and [PdCl2(PhCN)2] (11.89 mg, 0.031 mmol) were added in dry oxygen-free chloroform (15 cm3) and the resulting mixture stirred at 25 °C for 2 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue recrystallized form chloroma/hexane. Yield: 28.08 mg, 61%. Anal. found: C, 58.2; H, 4.6; N, 1.8. C72H70Cl2F6N2P4Pd2 requires C, 58.2; H, 4.7; N, 1.9%. IR: u(C=N) 1625m,1603 cm−1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm, J Hz): 8.0, 7.93 [s, 2H, HC=N], 6.8 [s, 1H, H2], 6.3 [d, 1H, H4, J(HH) = 7.7] 6.01 [dd, 1H, H5, J(PH) = 7.4]. 31P-{1H} NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm) 109.4 [t, 1P, J(PP) = 23.0 Hz], 44.2 [d, 2P], 17.9 [s, 2P].

Compounds 8b and 9b were prepared analogously from [PdCl2PhCN)2] and [PtMe2COD)], respectively.

3.2.5. Synthesis of 8b

Compound 6b (40 mg, 0.031 mmol); [PtCl2(PhCN)2] (14.63 mg, 0.031 mmol) C72H70Cl2F6N2P4PdPt requires C, 54.9; H, 4.; N, 1.8%. Yield: 32.68 mg, 67%. Anal. found: C, 58.2; H, 4.6; N, 1.8. C72H70Cl2F6N2P4Pd2 requires C, 58.2; H, 4.7; N, 1.9%. IR: u(C=N) 1625m,1603 cm−1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm, J Hz): 8.0, 7.93 [s, 2H, HC = N], 6.8 [s, 1H, H2], 6.3 [d, 1H, H4, J(HH) = 7.7] 6.01 [dd, 1H, H5, J(PH) = 7.4]. 31P-{1H} NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm) 109.3 [t, 1P, J(PP) = 23.0 Hz], 44.1 [d, 2P], -4.9 [s, 2P, J(PtP) = 3296].

3.2.6. Synthesis of 9b

Compound 6b (40 mg, 0.031 mmol); [PdMe2(COD)] (10.33 mg, 0.031 mmol) C74H76Cl2F6N2P4PdPt requires C, 5.4; H, 4.8; N, 1.7%. Yield: 35.3 mg, 71%. Anal. found: C, 58.2; H, 4.6; N, 1.8. C72H70Cl2F6N2P4Pd2 requires C, 58.2; H, 4.7; N, 1.9%. IR: u(C = N) 1625m,1603 cm−1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm, J Hz): 8.0, 7.85 [s, 2H, HC=N], 6.6 [s, 1H, H2], 6.2 [d, 1H, H4, J(HH) = 7.7], 6.0 [dd, 1H, H5, J(PH) = 7.4], 1.43 [s, 6H, Me, J(PtH) = 67.4]. 31P-{1H} NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm) 109.3 [t, 1P, J(PP) = 23.0 Hz], 92.6 [d, 2P], 18.0 [s, 2P, J(PtP) = 2426].

3.3. Crystal Structure Analysis and Details on Data Collection and Refinement

Compound 5b: 2215129, compound 10: 2215130 (starting from 3a) and 2144107 (starting from 2a) CCDC and CCDC. See Supplementary Materials Tables S1–S9.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the palladacycles bearing 1,3- and 1,4-bidentate imines are appropriate starting materials to prepare new metaloligands, especially those derived from the meta-substituted ligands. The metallacycles undergo stepwise cleavage of the C=N double bonds to render the two non-coordinated formyls groups; treatment with aminophosphine ligands gives species with two phosphorus donors. The resulting complexes, which may be coined as bidentate [P,P] metaloligands, can effectively bind to palladium or platinum in a chelate fashion to render stable homo- or hetero-double nuclear compounds. In the course of this research paper, we have found a totally serendipitous result, which shows the ease with which bonds on palladium can self-modify in palladacycles. Namely, compounds 2a and 3a are spontaneously and independently transformed into the double nuclear complex 10, inclusive of a second metalation of the phenyl ring. Whether or not the tentatively proposed mechanism for this situation is totally or in part correct, the X-ray diffraction result is unquestionable evidence of this outcome. A further interesting feature of 10 is the value for the palladium-nitrogen bond, which makes it the shortest distance found to date in this type of complexes. Further studies are presently in progress in order to shed more light regarding this process.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules28052328/s1, Tables S1–S9 For the crystal structures of 10 and 5b.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.V. and F.R.; methodology, G.A.; software, F.R.; validation, J.M.V., B.a.J. and F.R.; formal analysis, J.M.O.; investigation J.M.V.; resources, J.M.O.; data curation, B.a.J.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.V. and B.a.J.; writing—review and editing, J.M.V.; visualization, J.M.V. and F.R.; supervision, J.M.V.; project administration, J.M.O.; funding acquisition, J.M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is only available form the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was made possible thanks to the financial support received from the Xunta de Galicia (Galicia, Spain) under the Grupos de Referencia Competitiva Programme (Project GRC2019/14).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Albrecht M. Cyclometalation using d-block transition metals: Fundamental aspects and recent trends. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:576–623. doi: 10.1021/cr900279a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omae I. Cyclometalation Reactions: Five-Membered Ring Products as Universal Reagents. Springer; Tokyo, Japan: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vila J.M., Pereira M. The Pd-C Building Block of Palladacycles: A Cornerstone for Stoichiometric C-C and C-X Bond Assemblage. In: Dupont J., Pfeffer M., editors. Palladacycles. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH; Weinheim, Germany: 2008. pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albert J., D’Andrea L., Granell J., Pla-Vilanova P., Quirante J., Khosa M.K., Calvis C., Messeguer R., Badía J., Baldomà L., et al. Cyclopalladated and cycloplatinated benzophenone imines: Antitumor, antibacterial and antioxidant activities, DNA interaction and cathepsin B inhibition. J. Inorganic Biochemistry. 2014;140:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryabov A.D. The Exchange of Cyclometalated Ligands. Molecules. 2021;26:210. doi: 10.3390/MOLECULES26010210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilis M., Batalu D., Pasuk I., Cîrcu V. Cyclometalated palladium(II) metalomesogens with Schiff bases and N-benzoyl thiourea derivatives as co-ligands. J. Mol. Liq. 2017;233:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.02.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Y., Song T., Cao Y., Gong G., Zhang Y., Zhao H., Zhao G. Synthesis and characterization of planar chiral cyclopalladated ferrocenylimines: DNA/HSA interactions and in vitro cytotoxic activity. J. Organomet. Chem. 2018;871:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.06.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert J., Bosque R., Cadena M., D’Andrea L., Granell J., González A., Quirante J., Calvis C., Messeguer R., Badía J., et al. A new family of doubly cyclopalladated diimines. A remarkable effect of the linker between the metalated units on their cytotoxicity. Organometallics. 2014;33:2862–2873. doi: 10.1021/om500382f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramírez-Rave S., Morales-Morales D., Grévy J.M. Microwave assisted Suzuki-Miyaura and Mizoroki-Heck cross-couplings catalyzed by non-symmetric Pd(II) CNS pincers supported by iminophosphorane ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2017;462:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2017.03.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arthurs R.A., Hughes D.L., Richards C.J. Planar chiral palladacycle precatalysts for asymmetric synthesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020;18:5466–5472. doi: 10.1039/d0ob01331e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranieri A.M., Burt L.K., Stagni S., Zacchini S., Skelton B.W., Ogden M.I., Bissember A.C., Massi M. Anionic Cyclometalated Platinum(II) Tetrazolato Complexes as Viable Photoredox Catalysts. Organometallics. 2019;38:1108–1117. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alonso D.A., Nájera C., Pacheco M.C. Oxime-Derived Palladium Complexes as Very Efficient Catalysts for the Heck-Mizoroki Reaction. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2002;344:172–183. doi: 10.1002/1615-4169(200202)344:23.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucio-Martínez F., Adrio L.A., Polo-Ces P., Ortigueira J.M., Fernández J.J., Adams H., Pereira M.T., Vila J.M. Palladacycle catalysis: An innovation to the Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction. Dalt. Trans. 2016;45:17598–17601. doi: 10.1039/c6dt03542f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pretorius R., McDonald A., da Costa L.R.B., Müller-Bunz H., Albrecht M. Palladium(II), Rhodium(I), and Iridium(I) Complexes Containing O-Functionalized 1,2,3-Triazol-5-ylidene Ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019;2019:4263–4272. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201900724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrmann W.A., Brossmer C., Öfele K., Reisinger C.-P., Priermeier T., Beller M., Fischer H. Palladacycles as Structurally Defined Catalysts for the Heck Olefination of Chloro- and Bromoarenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995;34:1844–1848. doi: 10.1002/anie.199518441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrmann W.A., Böhm V.P.W., Reisinger C.P. Application of palladacycles in Heck type reactions. J. Organomet. Chem. 1999;576:23–41. doi: 10.1016/S0022-328X(98)01050-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyaura N., Suzuki A. Stereoselective synthesis of arylated (E)-alkenes by the reaction of alk-1-enylboranes with aryl halides in the presence of palladium catalyst. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1979;19:866–867. doi: 10.1039/c39790000866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki A. Carbon-carbon bonding made easy. Chem. Commun. 2005;38:4759–4763. doi: 10.1039/b507375h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albert J., D’Andrea L., Granell J., Tavera R., Font-Bardia M., Solans X. Synthesis and reactivity towards carbon monoxide of an optically active endo five-membered ortho-cyclopalladated imine: X-ray molecular structure of trans-(μ-Cl)2[Pd(κ2-C,N-(R)-C6H4-CH{double bond, long}N-CHMe-Ph)]2. J. Organomet. Chem. 2007;692:3070–3080. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2007.03.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vila J.M., Gayoso M., Pereira M.T., López M., Alonso G., Fernández J.J. Cyclometallated complexes of PdII and MnI with N,N-terephthalylidenebis(cyclohexylamine) J. Organomet. Chem. 1993;445:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0022-328X(93)80218-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vila J.M., Gayoso M., Pereira M.T., López-Torres M., Fernández J.J., Fernández A., Ortigueira J.M. Synthesis and characterization of cyclometallated complexes of palladium(II) and manganese(I) with bidentate Schiff bases. J. Organomet. Chem. 1996;506:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickmu G.C., Smoliakova I.P. Cyclopalladated complexes containing an (sp3)C–Pd bond. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020;409:213203. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thombal R.S., Feoktistova T., González-Montiel G.A., Cheong P.H.Y., Lee Y.R. Palladium-catalyzed synthesis of β-hydroxy compounds: Via a strained 6,4-palladacycle from directed C-H activation of anilines and C-O insertion of epoxides. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:7260–7265. doi: 10.1039/d0sc01462a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albert J., Gómez M., Granell J., Sales J., Soláns X. Five- and Six-Membered Exo-Cyclopalladated Compounds of N-Benzylideneamines. Synthesis and X-ray Crystal Structure of [PdBr{p-MeOC6H3(CH2)2N=CH(2,6-Cl2C6H3)}(PPh3)] and [PdBr{p-MeOC6H3(CH2)2N=CH(2,6-Cl2C6H3(PEt3)2] Organometallics. 1990;9:1405–1413. [Google Scholar]

- 25.López-Torres M., Fernández A., Fernández J.J., Suárez A., Pereira M.T., Ortigueira J.M., Vila J.M., Admas H. Mono- and Dinuclear Five-coordinate Cyclometalated Palladium(II) Compounds. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:4583–4587. doi: 10.1021/ic001094g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bedford R.B., Betham M., Butts C.P., Coles S.J., Cutajar M., Gelbrich T., Hursthouse M.B., Scullyd P.N., Wimperisc S. Five-coordinate Pd(II) orthometallated triarylphosphite complexes. Dalton Trans. 2007:459–466. doi: 10.1039/b613524b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kistes I., Gelman D. Carbometalated Complexes Possessing Tripodal Pseudo-C3-Symmetric Triptycene-Based Ligands. Organometallics. 2018;37:526–529. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samiee S., Shiralinia A., Hoviezi E., Gable E.H. Mono- and dinuclear oxime palladacycles bearing diphosphine ligands: An unusual coordination mode for dppe. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019;33:e5098. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onoue H., Moritani I. Ortho-Metalation reactions of N-phenylbenzaldimine and its related compounds by palladium (II) acetate. J. Organomet. Chem. 1972;43:431–436. doi: 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)81621-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onoue H., Minami K., Nakagawa K. Aromatic metalation reactions by palladium (II) and platinum (II) on aromatic aldoximes and ketoximes. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1970;43:3480–3485. doi: 10.1246/BCSJ.43.3480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ustynyuk Y.A., Chertkov V.A., Barinov I.V. The interaction of nickelocene with benzal anilines. J. Organomet. Chem. 1971;29:C53–C54. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cecconi F., Ghilardi C.A., Midollini S., Moneti S., Orlandini A., Scapacci G. Palladium complexes with the tripodal phosphine tris-(2-diphenylphos-phinoethyl) amine. Synthesis and structure of trigonal, tetrahedral, trigonal bipyramidal, and square planar complexes. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1989;2:211–216. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armarego W.L. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals. Butterworth-Heinemann; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data is only available form the authors on request.