Abstract

New vaccine strategies are needed for the prevention of leptospirosis, a widespread human and animal disease caused by pathogenic leptospires. Our previous work determined that a protein leptospiral extract conferred cross-protection in a gerbil model of leptospirosis. The 31- to 34-kDa protein fraction of Leptospira interrogans serovar autumnalis was shown sufficient for this purpose. In the present study, N-terminal sequencing of a 32-kDa fraction and Southern blotting of genomic DNA with corresponding degenerated oligonucleotide probes identified two of its constituents: hemolysis-associated protein 1 (Hap1) and the outer membrane Leptospira protein 1 (OmpL1). Adenovirus-mediated Hap1 vaccination induces significant protection against a virulent heterologous Leptospira challenge in gerbils, whereas a similar OmpL1 construct failed to protect the animals. These data indicate that Hap1 could be a good candidate for developing a new generation of vaccines able to induce broad protection against leptospirosis disease.

Leptospirosis is an infectious disease in both humans and animals, caused by spirochetes belonging to the genus Leptospira. Pathogenic leptospires were formerly classified as members of the species Leptospira interrogans, which was divided into numerous serogroups. Leptospirosis in mammals is transmitted by direct contact with infected animals or by exposure to water, moist soil, or vegetation contaminated by the urine of infected animals (9, 10, 26). Although leptospirosis has a worldwide distribution, it is most common in tropical and rural areas (9, 10, 21, 35). This acute febrile disease can progress to hepatic and renal dysfunction and hemorrhagic disorders that cause death in 5 to 10% of cases in humans (9, 10, 21) and are more lethal in dogs. In livestock, Leptospira infection is a frequent cause of abortion, stillbirth, infertility, milk drop syndrome, and (occasionally) death (4, 13, 23, 25, 31).

The medical and economic losses caused by such forms of the zoonotic disease justify the use of Leptospira vaccines in human or animal populations at risk. However, available vaccines confer only short-lasting immunity (6 to 12 months) and induce a lipopolysaccharide-directed immune response that is serogroup specific. As these bacterins provide no cross-protection between the different serogroups, several inactivated strains are incorporated into current vaccines to cover the spectrum of the most probable contaminants. However, these vaccines generally provide protection against the lethal onset of the disease but do not prevent persistent shedding of spirochetes from infected animals.

The identification of the common immunogenic proteins of Leptospira would be a major step toward the development of purer, better-defined, and probably more-efficient vaccines. Such vaccines would confer cross-protection against a wide range of pathogenic Leptospira strains. Our previous work showed that a whole proteic extract prepared from pathogenic L. interrogans serovar autumnalis provided significant cross-protection against a heterologous challenge, whereas no protective effect was induced by the same extract prepared from saprophytic Leptospira biflexa strain Patoc (32, 33). The purpose of the present study was to investigate the protective effect of proteic antigens common to the different serogroups of the pathogenic species L. interrogans but not identified or poorly expressed in the saprophytic species (11). We first studied the protective potency of the highly antigenic 31- to 34-kDa protein fraction recognized by analysis of sera from animals immunized with the pathogenic strains and identified the major proteins that constitute the 31- to 34-kDa fraction. Finally, the effects of both proteins found in the 32-kDa fraction were tested in laboratory animals vaccinated with recombinant adenoviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Leptospira strains.

L. interrogans serovar autumnalis (strain 32) was isolated from the liver of a dead dog. This strain, which was selected based on the acute clinical effects observed in infected dogs, lost its virulence following several subcultures.

L. interrogans serogroup Icterohaemorrhagiae (serovars copenhageni strain M20 and icterohaemorrhagiae strain RGA), L. interrogans serovar canicola (strain Hond Utrecht), and L. biflexa strain Patoc were kindly provided by the Pasteur Institute (Paris, France).

A virulent strain of L. interrogans serovar canicola was kindly provided by the Pasteur Institute (Paris, France) and was used for challenge. The virulence of the strain was maintained by regular passages (twice a year) into gerbils in the laboratory.

Leptospires were cultured in EMJH enriched medium at 29°C (7) and grown to 109 leptospires/ml, as estimated by turbidimetry with a Hach apparatus calibrated as previously described (33). Typically, 100 turbidimetric units were equivalent to 2 × 108 to 5 × 108 leptospires/ml.

Preparation of protein extracts from leptospires and amino acid sequencing.

Leptospira serovar autumnalis proteins were separated by chloroform-methanol-water extraction, as previously described (1), and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (12.5% polyacrylamide) was carried out with 5 mg of protein per gel. The 26- to 31- and 31- to 34-kDa fractions were excised from each gel with a cutter.

Preparative electrophoresis was performed with a Prep Cell (Bio-Rad). Purified fractions between 26 and 34 kDa were collected, and the 32-kDa fraction was selected for microsequencing. A 16-amino-acid (16-aa) sequence (peptide A) obtained after lysozyme treatment and a 14-aa N-terminal sequence (peptide B) were determined. Homology search of the GenBank database was performed by the BLAST program with Expasy software.

Southern blot analysis.

Plasmid DNA preparations, restriction enzyme digests, and Southern blot analysis were performed under standard conditions (27). Serovar autumnalis genomic DNA was digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes (2, 36), separated, transferred onto Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and hybridized with two degenerated nucleic probes labeled with [γ-32P]dATP. Probe A (5′-GTNATHAAYTAYTAYGGNTAYGTNAAAR-3′) and probe B (5′-ACNTAYGCNATHGTNGGNTTYGGNYT-3′) corresponded, respectively, to peptide A and peptide B. Hybridization was performed overnight at 39°C (probe A) or 49°C (probe B) under standard conditions, followed by washing in 1% saline sodium citrate (0.3 M sodium citrate, 3 M NaCl [pH 7]) containing 0.1% SDS at 39 or 49°C and exposure to Kodak film at −80°C.

DNA sequence analysis.

The sequence of the forward primer for hemolysis-associated protein 1 (Hap1) was 5′-ACCGTGATTTTCCTAACTAAGGA-3′. The sequence of the reverse primer for Hap1 was 5′-AAGCGAGTAAGTAGAATTGAAGGATCGATC-3′. The PCR product amplified from the genomic DNA of serovar autumnalis strain 32 was cloned by TA cloning of the PCRII.1 vector (Invitrogen); both strands of the DNA insert were sequenced (ACT gene).

Prokaryotic expression system. (i) Cloning.

Genomic DNA of L. interrogans serovar autumnalis strain 32 was used as a template for PCR isolation of the target sequences. The sequences of the forward primers for Hap1 and outer membrane Leptospira protein 1 (OmpL1) were 5′-ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCATGAAAAAACTTTCGATTTTGGC-3′ and 5′-ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCATGACATATGCAATTGTAGG-3′, respectively. These primers have a 16-bp sequence (underlined) at the 5′ end (NotI site). The sequences of the reverse primers for hap1 and ompL1 were 5′-CCGCTCGAGCTTAGTCGCGTCAGAAGCAGC-3′ and 5′-CCGCTCGAGGAGTTCGTGTTTATAACCG-3′, respectively, corresponding to aa 265 to 271 for Hap1 and aa 313 to 319 for OmpL1 (without any stop codon). These primers have a 9-bp sequence (underlined) at the 5′ end to create an XhoI site. The 0.9- and 0.85-kb PCR fragments were digested and ligated into the NotI and XhoI sites of a pET-29b expression vector (Novagen, Inc.) to produce a C-terminal fusion protein with a histidine tag, generating pET-29b-hap1 and pET-29b-ompL1 plasmids, respectively. Both strands of the DNA insert were sequenced (ACT gene).

(ii) Recombinant protein production and purification.

The two plasmids containing the sequence encoding either Hap1 or OmpL1 were amplified in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)-competent cells (Stratagene). Bacteria were harvested 180 min after induction with 1 mM β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, and the pellets were washed and sonicated. After centrifugation, the supernatant was directly loaded onto a Hi-Trap chelating column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated with phosphate buffer (NaH2PO4–0.02 M Na2HPO4–0.5 M NaCl [pH 7.2]). Proteins were eluted with a 40- to 250 mM imidazole gradient and then extensively dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of recombinant proteins.

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide), as previously described (22) and transferred onto nitrocellulose sheets (Bio-Rad) with a semidry system in Tris buffer (48 mM Tris [pH = 9.2], 39 mM glycine, 1.3 mM SDS, 20% methanol). After overnight blocking at 4°C with 3% bovine serum albumin in TBST (10 mM Tris [pH = 8], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20), recombinant proteins were selectively identified by Western blotting with antihistidine antibody (Qiagen) followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Promega) or rabbit anti-leptospire serum followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Bio-Rad).

Adenovirus constructs.

SalI-NaeI fragments prepared from pET-29b-hap1 and pET-29b-ompL1 were ligated into pAd5-CMV-link-intron between the SalI site and the NotI blunt-ended site, generating, respectively, the shuttle plasmids pAd5CMV-link-intron-hap1 and pAd5CMV-link-intron-ompL1. The pAd5CMV- link-intron construct contains the cytomegalovirus immediate-early enhancer-promoter region, a chimeric intron, and the simian virus 40 late polyadenylation signal. Recombinant adenoviral genomes pAd-hap1 and pAd-ompL1 were generated by homologous recombination in E. coli BJ5183 (6) using ClaI-linearized pAd5-CMVβgal and the 4-kbp PvuI-NsiI fragment of, respectively, pAd5CMV-link-intron-hap1 and pAd5CMV-link-intron-ompL1. Plasmid pAd5-CMVβgal contains a replication-defective human adenovirus type 5 recombinant genome harboring a CMVβgal expression cassette instead of the E1 region. Recombinant viruses Ad-hap1 or Ad-ompL1 were produced following transfection of 293 cells with 1 μg of PacI-digested pAd-hap1 or pAd-ompL1 and 15 μl of Lipofectamine reagent (Life Technologies) in six-well plates. Clonally derived recombinant viruses were isolated, propagated, and characterized by restriction enzyme analysis and Western blotting to confirm the identity of the recombinant adenovirus and its expression products (5). Recombinant adenovirus deleted in the E1 region without any inserted foreign sequence (Ad-null) was used as a control. Large-scale adenovirus production was performed as previously described (8). Virus stocks were stored at −80°C in PBS with 10% glycerol.

Immunizations.

Six- to 12-week-old Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) were bred in the laboratory.

(i) Immunization with 26- to 31-kDa and 31- to 34-kDa protein fractions.

Three groups of gerbils received two intraperitoneal injections (with a 2-week interval between injections) of 400 μg of protein extract in ground sonicated acrylamide-bis acrylamide gel. For their welfare, animals received 20 mg of acetylsalicilic acid (Vetalgine ND)/kg of body weight at each immunization.

(ii) Recombinant adenovirus immunization.

For each vaccination, animals were anesthesized intraperitoneally with 0.2 mg of ketamine/kg of body weight and 0.08 mg of xylazine/kg of body weight and then vaccinated twice (with a 3-week interval between vaccinations) intramuscularly in the left quadriceps. A 28-gauge needle was used to deliver 50 μl of vaccine containing 109 PFU of the relevant virus construct. Controls received either PBS (trial 1) or recombinant Ad-null (trial 2).

Challenges. (i) Protein fraction (26- to 31- and 31- to 34-kDa)-immunized animals.

The challenge was performed 2 weeks after the second immunization. Each animal received 108.7 leptospires in 0.5 ml of a fresh culture of the virulent L. interrogans serovar canicola. Gerbils were observed daily, and the rate of mortality was recorded for 21 days after the challenge.

(ii) Recombinant adenovirus-immunized animals.

The challenges were performed 2 weeks after the second immunization by injection of 104.3 leptospires in 0.5 ml of the virulent strain of L. interrogans serovar canicola. Gerbil mortality was recorded daily after challenge, and surviving animals were sacrificed after 30 days for serum analysis by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Serological analysis. (i) Protein fraction (26- to 31- and 31- to 34-kDa)-immunized animals.

Blood samples were drawn on the day of the challenge and controlled by microscopic agglutination test (MAT) performed with serovar autumnalis, icterohaemorrhagiae, copenhageni, and canicola cultures. Western blot analysis was performed with total serovar autumnalis extract, as previously described (11).

(ii) Recombinant adenovirus-immunized animals.

Blood sampling was done on days 0, 14, 21, 35, and 65, and specific serum antibodies were measured by ELISA. Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates (Nunc) were coated overnight at 4°C with 4 μg of recombinant Hap1 (rHap1) or CsCl-purified Ad5 at 106 PFU per well. Plates were washed three times with TE-t (50 mM Tris [pH = 7.6], 50 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20) and then blocked with TE-t containing 1% (wt/vol) gelatin at 37°C for 30 min. One hundred microliters of diluted serum (1:50 to 1:2,000) was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After five washes, diluted biotin rabbit anti-gerbil IgG (1:1,000) (Bioatlantic) was incubated for 30 min at 37°C, followed by four washes with TE-t. Streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Finally, the plates were washed four times, and 3,3′-5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine chromogenic substrate was added. After 10 min, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 2 M H2SO4. Optical density was measured at 405 nm (Labsystems Multiskan MCC/340).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the hap1 gene from L. interrogans serovar autumnalis strain 32 has been deposited in GenBank database under accession no. AF366366.

RESULTS

Protection against heterologous challenge in animals vaccinated with 26- to 31- and 31- to 34-kDa protein fractions.

By Western blot analysis, dog sera with leptospirosis have been shown to differentially react against proteins from pathogenic (L. interrogans) and nonpathogenic (L. biflexa) leptospire strains. In particular, those sera specifically react against fractions of 26 to 31 kDa and 31 to 34 kDa from serovar autumnalis not found in L. biflexa. To further characterize the immunogenic properties of these fractions, an immunization assay was conducted with a gerbil model of leptospirosis with extraction products from serovar autumnalis fractions of 26 to 31 and 31 to 34 kDa. Two groups (n = 10) of animals were immunized with 26- to 31- or 31- to 34-kDa fractions, and a control group (n = 14) was immunized with a L. biflexa whole-protein extract. Animals were challenged with the pathogenic serovar canicola strain. Ten days after challenge, all animals in the L. biflexa control group had died, whereas 4 of 10 animals immunized with 31- to 34-kDa L. interrogans proteins and 2 of 10 immunized with 26- to 31-kDa L. interrogans proteins were still alive at the end of the trial. The survival rate for animals vaccinated with 31- to 34-kDa proteins was significant (Yates chi-square test; P < 0.05).

Serological controls by MAT and Western blot analyses showed that animals immunized with the 31- to 34-kDa fraction failed to produce agglutinating antibody but only antibodies recognizing two adjacent but well-defined bands in the Western blots. Serological control analyses of the sera of animals immunized with 26- to 31-kDa protein remained negative for MAT but exhibited a smear with Western blotting, indicating that the 26- to 31-kDa protein extract was still mildly contaminated by lipopolysaccharide.

Identification of the major components of the 32-kDa fraction.

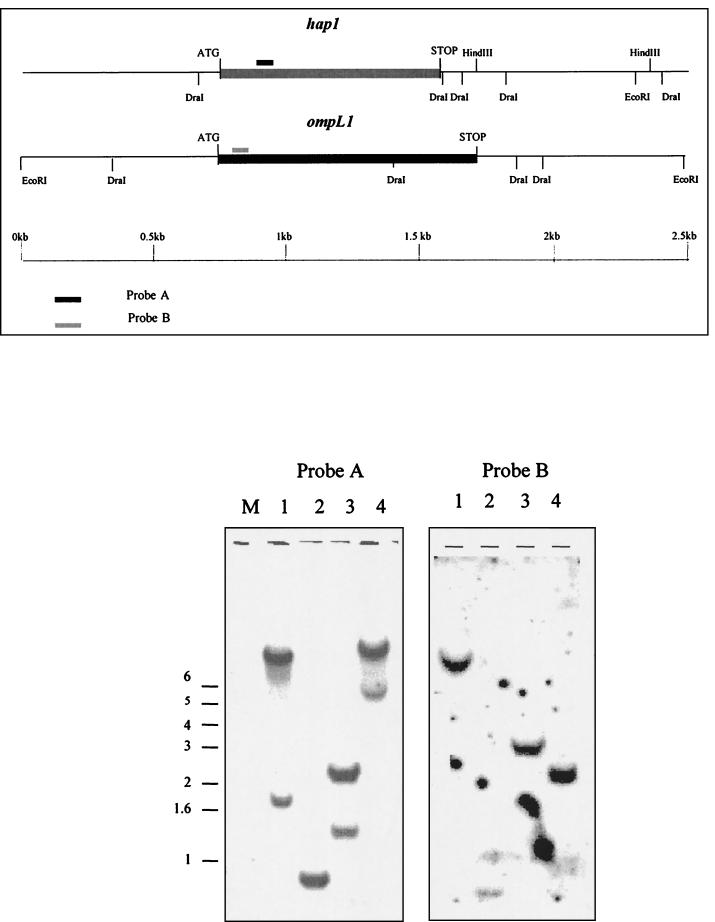

Preparative electrophoresis was performed only with the 31- to 34-kDa fraction in order to separate the major proteins found at 32 and 34 kDa. The purified 32- and 34-kDa fractions were then selected for amino acid sequencing. Peptide sequencing performed with the 32-kDa fraction identified two sequences: TFLPYGSVINYYGYVK (peptide A) and TYAIVGFGLQLDLG (peptide B). According to the BLAST analysis, peptide A showed 93% identity to a part of Hap1 from L. interrogans serovar lai (GenBank accession no. AAB68646, aa 49 to 64). Peptide B was identical to a peptide present in OmpL1 from Leptospira kirschneri (GenBank accession no. AAA74591, aa 26 to 39). To ensure that these peptides were not part of other nonrelated proteins, degenerated oligonucleotide probes were designed (probes A and B, corresponding to peptide A and peptide B) to identify other potential genes coding for these peptides. The hybridization results for probes A and B are presented in Fig. 1. Hybridization with peptide A allowed detection of fragments at 0.9 to 1, 2.3, and >6 kb (we considered only the most intensive fragment), and hybridization with peptide B allowed detection of fragments at 0.8 to 0.9, 2.7 to 2.9, and >6 kb for genomic DNA digested, respectively, by DraI, EcoRI, and BglII. The sizes of these fragments were concordant with those obtained from maps described for hap1 and ompL1. Therefore, it was concluded that the 32-kDa antigenic fraction contained at least two proteins: Hap1 and OmpL1. For technical reasons, amino acid sequencing of the 34-kDa fraction was unsuccessful.

FIG. 1.

(Top) A restriction map of the 2.5-kb fragment containing the hap1 gene from L. interrogans serovar lai and the 2.5-kb EcoRI fragment containing the ompL1 gene from L. kirshneri serovar grippotyphosa (15) is shown. (Bottom) Southern blot of L. interrogans serovar autumnalis genomic DNA digested by four restriction enzymes (see restriction maps) and probed with probes A and B, corresponding to peptides A and B. Lanes 1, BglII; lanes 2, DraI; lanes 3, EcoRI; lanes 4, HindIII. M, molecular mass markers.

Production and purification of rHap1.

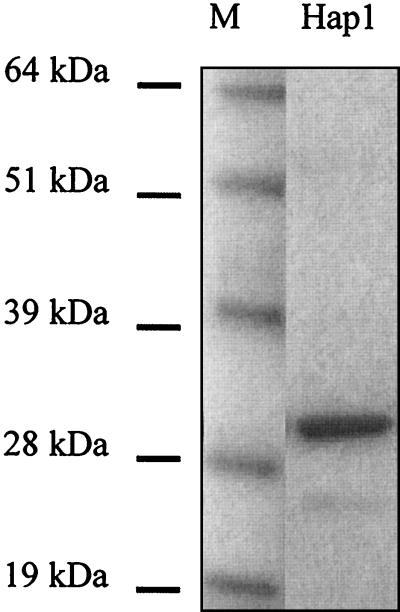

Upon E. coli production, rHap1 was detected in both bacteria and the culture medium. Western blot analysis of the bacterial lysate identified three bands between 28 and 32 kDa, whereas a single band at 31 kDa was detected in the culture medium. Affinity chromatography (Hi-Trap chelating column) allowed selective purification of one of the three proteins found in the bacterial lysate (Fig. 2). As this purified protein comigrated with the recombinant protein found in the culture medium, it was used as the antigen in ELISA.

FIG. 2.

Coomassie brilliant blue-staining of SDS-PAGE gels showing purified rHap1 (Hap1). M, molecular mass markers.

Gerbil antibody response to adenovirus-mediated immunization.

Recombinant adenovirus was chosen as an in vivo eukaryotic expression system. Two adenoviral constructs were generated, Ad-hap1 and Ad-ompL1. Both recombinant adenoviruses are designed as a replication-defective adenovirus expressing a Hap1 or OmpL1 open reading frame under the control of the IE gene promoter from human cytomegalovirus. An immunization assay was conducted using both recombinant adenoviruses Ad-hap1 and Ad-ompL1.

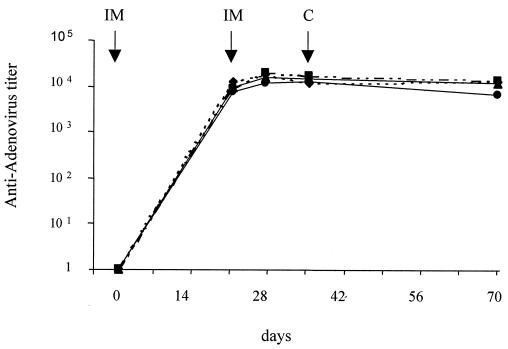

The humoral immune response of gerbils immunized with either Ad-hap1 or Ad-ompL1 or a combination of both recombinant adenoviruses was analyzed by IgG ELISA against the adenovirus vector itself (Fig. 3). After the first injection, antiadenovirus response increased rapidly, reaching a plateau that was boosted neither by a second injection nor after the challenge. Moreover, there was no significant decrease in response throughout the whole experiment.

FIG. 3.

Anti-adenovirus ELISA antibody responses in intramuscularly immunized animals (IM) with Ad-hap1 (●), Ad-ompL1 (▪), Ad-hap1 plus Ad-ompL1 (♦), and Ad-null (▴), followed by intraperitoneal heterologous challenge (C). Each point corresponds to the pool of sera sampled at each time point during assay 2.

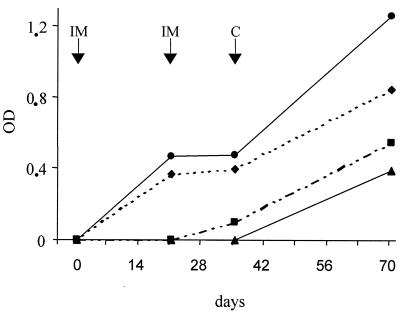

The humoral response against Hap1 was determined by ELISA against recombinant rHap1 (Fig. 4). No antibody response against Hap1 was detected in the control after immunization. As expected with group 2 (Ad-ompL1), no significant antibody response against Hap1 was developed after immunization. In groups 1 (Ad-hap1) and 3 (Ad-hap1 plus Ad-ompl1), there was a significant increase in the antibody titer after the first injection, which was not boosted by the second immunization. Furthermore, heterologous challenge induced an immune response against Hap1 in the group control (Ad-null) and a strong increase in immune response in the surviving gerbils of the other groups. It is noteworthy that the highest boost effect of the response against Hap1 was obtained with group 1 (Ad-hap1).

FIG. 4.

Anti-rHap1 ELISA antibody responses in intramuscularly immunized animals (IM) expressed as optical densities with Ad-hap1 (●), Ad-ompL1 (▪), Ad-hap1 plus Ad-ompL1 (♦), and Ad-null (▴), followed by intraperitoneal heterologous challenge (C). Each point corresponds to the pool of sera sampled at each time point during assay 2.

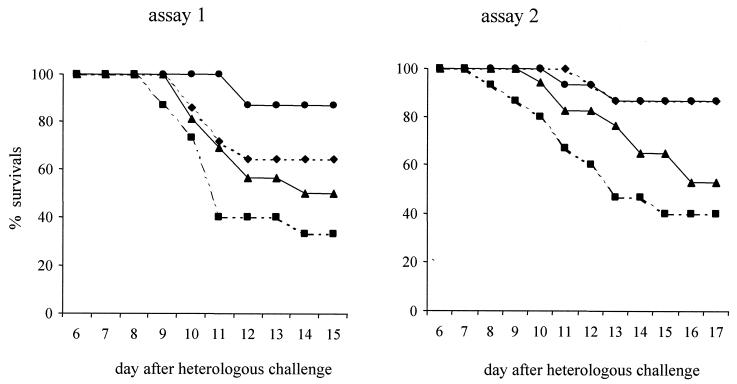

Protective effect against challenge.

Gerbils were challenged with L. interrogans serovar canicola 2 weeks after the last adenovirus injection, and mortality rates were recorded 30 days after the challenge. The experiments were performed twice, with controls receiving either PBS or Ad-null (Table 1). During the two trials, no significant difference was observed between controls receiving PBS and Ad-null (8 of 16 survivals in the first trial versus 9 of 17 in the second 30 days postchallenge). The consistency of results in the control groups led us to analyze the combined results of the two experiments. In the two trials, mortality rates were not significantly different between animals vaccinated with recombinant adenovirus expressing OmpL1 (Ad-ompL1) and controls (11 of 30 versus 17 of 33). In the first trial, 13 of 15 Ad-hap1-vaccinated animals survived versus 8 of 16 controls (exact chi-square unilateral test; P < 0.03). Similar results were observed in the second trial: 13 of 15 versus 9 of 17. The survival rate of gerbils vaccinated with Ad-hap1 was significantly higher than those of both controls (P < 0.01) and gerbils vaccinated with Ad-ompL1 (P < 0.001). Survival of animals vaccinated with both adenovirus-expressed proteins was 9 of 14 versus 8 of 16 in the control group for the first trial and 13 of 15 versus 9 of 17 for the second. This difference was only statistically significant for the second trial (P < 0.01). Analysis of the combined results from both experiments showed no significant protection with Ad-hap1 and Ad-ompL1 together 30 days after challenge.

TABLE 1.

Protective effect of immunization with Ad-hap1, Ad-ompL1, or a combination of both, followed by intraperitoneal heterologous challengea

| Treatment group | Surviving animals/groupb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Total (%) | |

| Ad-hap1 | 13/15 | 13/15 | 26/30 (87) |

| Ad-ompL1 | 5/15 | 6/15 | 11/30 (36.6) |

| Ad-hap1 + Ad-ompL1 | 9/14 | 13/15 | 22/29 (75.8) |

| Ad-null | 9/17 | 17/33 (51) | |

| PBS | 8/16 | ||

Animals were vaccinated twice at 3-week intervals and challenged with L. interrogans serovar Canicola 2 weeks after the last vaccine injection.

Values on the number of surviving animals 30 days after challenge divided by the number of animals challenged.

Statistical analysis of mortality incidence (log rank test) for the two trials is shown in Table 2. Animals immunized by the two proteins expressed by adenovirus, compared to control animals, showed a significant survival rate for the second trial (P < 0.005) but not for the first. When these animals were compared with those immunized with Ad-ompL1, the difference was statistically significant for both experiments (P < 0.02 and P < 0.005). Moreover, when the results for the two experiments were combined, this difference was significant compared to the control or the group immunized by Ad-ompL1 (P < 0.01 and P < 0.005). Table 1 shows that the group immunized by Ad-ompL1 had a lower rate of survival (5 of 15; 6 of 15), regardless of the experiment. Figure 5 indicates that death occurred earlier in this group than in the others. In terms of the rate of death, there was significant difference between this group and the control group over all the experiments.

TABLE 2.

Statistical analysis of the surviving curves produced by the log rank testa

| Group(s) | Expt 1

|

Expt

2

|

Total

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | P | χ2 | P | χ2 | P | |

| Ad-hap1/control | 6.64 | <1.10−2 | 5.52 | <2.10−2 | 10.77 | <5.10−3 |

| Ad-hap1/Ad-ompL1 | 8.9 | <5.10−3 | 9.22 | <5.10−3 | 14.35 | <1.10−3 |

| Ad-hap1 + Ad-ompL1/control | 1.34 | NSb | 8.54 | <5.10−3 | 7.56 | <1.10−2 |

| Ad-hap1 + Ad-ompL1/Ad-ompL1 | 5.48 | <2.10−2 | 8.62 | <5.10−3 | 9.91 | <5.10−3 |

| Ad-ompL1/control | 4.59 | <5.10−2 | 3.87 | <5.10−2 | 7.48 | <1.10−2 |

Statistical analysis was performed with the log rank test. Significance was determined by comparison to the control group or the Ad-ompL1-immunized group.

NS, not significant.

FIG. 5.

Survival curves of gerbils after intramuscular immunization with Ad-hap1 (●), Ad-ompL1 (▪), Ad-hap1 plus Ad-ompL1 (♦), or PBS for assay 1 or Ad-null for assay 2 (▴), followed by intraperitoneal heterologous challenge.

DISCUSSION

Our previous work showed that leptospire protein extracts can induce cross-protection within pathogenic strains of Leptospira in the gerbil model (32, 33). The purpose of the present study was to provide a more precise definition of the proteins involved in this response, i.e., to identify those proteins common to pathogenic strains that would be most suitable as vaccines, providing cross-protection against several Leptospira serovars. Previous results obtained by Gitton et al. (11, 12) and Haake et al. and Zuerner et al. (15, 37) showed that a 31- to 34-kDa protein fraction of L. interrogans was highly antigenic, i.e., the sera of infected animals were strongly recognized regardless of the infecting serovar. Moreover, this fraction seemed to be conserved in L. interrogans (pathogenic) but not in L. biflexa (saprophytic) (11, 15). Thus, this fraction appears to contain one or more proteins that could be useful for vaccine development (32). This led us to isolate the 31- to 34-kDa fraction and test its ability to induce significant protection in the gerbil model (32) when challenged by a heterologous L. interrogans serovar canicola strain. Immunization of gerbils with the 31- to 34-kDa protein fraction from serovar autumnalis resulted in partial protection against a challenge: vaccinated animals were significantly more resistant to heterologous challenge by L. interrogans serovar canicola (4 of 10 versus 0 of 10 in the control group).

Aminoterminal sequencing of the 32-kDa fraction purified by preparative electrophoresis from an extract of serovar autumnalis allowed the identification of peptide B and sequencing after lysozyme treatment produced peptide A. Peptide A was highly (93%) homologous to Hap1, first described by Lee et al. (24) and Kim et al. (M. J. Kim, K. A. Kim, S. J. Eom, S. C. Park, and Y. J. Lee, First Meet. Int. Leptospirosis Soc., 1996) and later designated LipL32 by Haake et al. (16), whereas peptide B was identical to an OmpL1 region of L. kirschneri (14). The Hap1 gene was isolated and sequenced on a DNA fragment containing the sphH sphingomyelinase gene (24). OmpL1 is a transmembrane outer membrane protein that functions as a porin in the leptospiral membrane (14, 30). So far, there has been no direct evidence in in vivo tests of protection by one of these proteins used alone.

Degenerated oligonucleotide probes corresponding to these peptides were designed to confirm that they belonged to these proteins and not to others sharing the same peptide sequences. As these probes only recognized the DNA sequences previously identified as regions encoding Hap1 and OmpL1, one or both were clearly implicated in the cross-protection observed in vivo. As another minor constituent of the 32-kDa fraction might not have been identified by aminoterminal sequencing of this fraction, the critical role of at least one of these proteins in protection remained to be demonstrated.

These proteins were first expressed in E. coli to use them as pure immunogens in protective trials and as soluble antigens for ELISAs. Expression of OmpL1 in E. coli gave results similar to those previously described by Haake et al. and Shang et al. (14, 30). Three 28- to 32-kDa bands appeared when an antihistidine antibody or a polyclonal rabbit antiserum against leptospires was used in Western blotting (data not shown). This recombinant protein could not be produced in large amounts because of its high toxicity in E. coli (30). Hap1 extracted from bacterial bodies and probed with the same sera gave three bands (28, 31, and 32 kDa), and this protein was also found as a single band (31 kDa) in the culture medium (data not shown). This result is not concordant with a previous report (16) of incomplete processing of Hap1 in E. coli, indicating that the recombinant protein was distributed equally between the membrane and the cytoplasm. No mention was made of its presence in culture medium. These data were interpreted as evidence of inefficient cleavage of the peptide signal in E. coli (16). Hap1 was described by Lee et al. (24) as a hemolysin secreted into the medium, which is in agreement with our results (data not shown).

As most potential cross-protective immunogens should have conserved sequences, the coding regions of these two proteins isolated from L. interrogans serovar autumnalis were sequenced and compared with the deduced amino acid sequences of counterparts isolated from other serovars. The Hap1 protein of L. interrogans serovar lai (GenBank accession no. AAB68646) and that of serovar autumnalis (GenBank accession no. AF366366) were found to be identical. Comparison of the Hap1 protein of L. interrogans serovar lai or serovar autumnalis with L. kirschneri serovar grippotyphosa (GenBank accession no. AAF60198) showed the same amino acid sequence except a prolin (Res-215), which generally plays a role in protein conformation. The partial sequence of the OmpL1 protein from L. interrogans serovar autumnalis was identical to that of L. kirschneri serovar grippotyphosa, except for 6 aa (not shown), 2 of which belonged to the same side chain group.

The direct protective effect of these common proteins (Hap1 and/or OmpL1) obtained from serovar autumnalis was then tested against lethal onset after a heterologous challenge. Due to the very low production yield of recombinant protein OmpL1 in E. coli, this antigen was not involved in vaccination trials. rHap1 produced in E. coli was tested in vaccination trials but showed no evidence of direct protection (data not shown). Therefore, it would seem likely that the mode of production and/or extraction of this recombinant protein and/or its presentation to the immune system are unsuitable for the elicitation of an appropriate immune response.

Replication-defective recombinant adenoviruses expressing Hap1 or OmpL1 were designed to facilitate direct gene transfer of these proteins into gerbils (20). Ad-hap1 induced significant protection against a challenge, whereas Ad-ompL1 induced no protection in immunized gerbils. The survival rate of gerbils vaccinated with Ad-hap1 was significantly higher than that of both controls and animals vaccinated with Ad-ompL1.

Haake et al. (17) found that the recombinant proteins OmpL1 and LipL41, alone or together, afforded no protection during virulent homologous challenge in the hamster model of leptospirosis, whereas significant protection was obtained when animals were immunized with the membrane-associated forms of these two proteins. This author deduced that they provide synergistic protection, although the way in which OmpL1 and LipL41 associate with membrane is an important determinant for immunoprotection. However, in our experiments, the group immunized by Ad-ompL1 afforded no significant protection compared to the control groups; moreover, the analysis of the combined experiments by the log rank test showed that the OmpL1 protein expressed by adenovirus had a negative effect on the two experiment groups versus the control group (P < 0.05). When taken together, the results for both experiments showed the most negative effect by Ad-ompL1 (P < 0.01). Therefore, it seemed of interest for us to test immunization with both Ad-hap1 and Ad-ompL1. Survival of animals immunized with both proteins expressed in adenovirus and that of the control group was statistically lower only in the second experiment (P < 0.05). But combining the data from both experiments improved the significance of the results from P < 0.05 to P < 0.01, indicating that the protective effect by Hap1 occurred throughout both experiments. This rate of survival, compared to that of the Ad-hap1 group alone, was not as significant. As the association of the two proteins had a negative effect when protection was significant with Ad-hap1 alone, it is likely that the OmpL1 protein expressed by adenovirus was responsible for this negative effect. However, it is unclear which mechanism or mechanisms facilitate the effect elicited by OmpL1.

As previously demonstrated for many genes (including those coding for proteins targeted to the cell nucleus), recombinant adenoviruses can elicit not only T-cytotoxic responses but also a strong antibody response against the foreign gene product (19). It is noteworthy that these eukaryotic vectors can be used against bacterial diseases, for which antibody response remains the main specific effector of immune response.

It has been suggested that hemolysins (28) play an important role in the virulence and pathogenesis of many bacteria and leptospires in particular (3, 29, 34). Moreover, Hap1 is only produced by pathogenic leptospires (16), which might reflect its role in virulence. The protective effect induced by Ad-hap1 immunization inhibits the virulent activity of the pathogenic strains. Moreover, this protein appears to be a powerful immunogen, as in the case of other bacteria for which hemolysins have been used as the main vaccine component (18). Follow-up studies are needed to define how the immunity resulting from Ad-hap1 immunization can be improved. Moreover, determination of the immunity mechanism and of the location of immunoprotective epitopes could make it possible to use other systems of immunization.

In conclusion, our results show that the cross-protective effect within pathogenic strains of Leptospira is shared by Hap1 protein mediated by an adenovirus vector. This finding should facilitate the design and development of new generations of vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the French Ministry of Agriculture, the ANRT, and Virbac Laboratories (Carros Cedex, France).

We thank C. Fillonneau, A. Fournier, S. Raimondi, and M. Touchard for exellent technical assistance and B. Blanchet for invaluable assistance with experimental work. V. Gonon, M. Hebben, S. Arrabal, S. Mercier and C. Denesvre are thanked for suggestions during the course of this work and C. Thorin for her helpful statistical advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auran N E, Johnson R C, Ritzi D M. Isolation of the outer sheath of Leptospiraand its immunogenic properties in hamsters. Infect Immun. 1972;5:968–975. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.6.968-975.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baril C, Herrmann J L, Richaud C, Margarita D, Saint Girons I. Scattering of the rRNA genes on the physical map of the circular chromosome of Leptospira interrogansserovar icterohaemorrhagiae. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7566–7571. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7566-7571.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer D C, Eames L N, Sleight S D, Ferguson L C. The significance of leptospiral hemolysin in the pathogenesis of Leptospira pomonainfections. J Infect Dis. 1961;108:229–236. doi: 10.1093/infdis/108.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett R M, Christiansen K, Clifton-Hadley R S. Estimating the costs associated with endemic disease of dairy cattle. J Dairy Res. 1999;66:455–459. doi: 10.1017/s0022029999003684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burleson F G, Chambers T M, Wiedbrauk D L. Virology: a laboratory manual. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chartier C, Degryse E, Gantzer M, Dieterlé A, Pavirani A, Mehtali M. Efficient generation of adenovirus vectors by homologous recombination in Escherchia coli. J Virol. 1996;70:4805–4810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4805-4810.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellighausen H C, McCullough W G. Nutrition of Leptospirapomona and growth of 13 other serotypes: fractionation of oleic albumin complex and a medium of bovin albumin and polysorbate 80. Am J Vet Res. 1965;26:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eloit M, Gilardi-Hebenstreit P, Toma B, Perricaudet M. Construction of a defective adenovirus vector expressing the pseudorabies virus glycoprotein gp50 and its use as a live vaccine. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:2425–2431. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-10-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faine S, Adler B, Bolin C, Perolat P. Leptospira and leptospirosis. 2nd ed. Victoria, Australia: Mediscience, Melbourne; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farr R W. Leptospirosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1–8. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gitton X, Andre-Fontaine G, Andre F, Ganiere J P. Immunoblotting study of the antigenic relationships among eight serogroups of Leptospira. Vet Microbiol. 1992;32:293–303. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90152-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gitton X, Daubie M B, Andre F, Ganiere J P, Andre-Fontaine G. Recognition of Leptospira interrogansantigens by vaccinated or infected dogs. Vet Microbiol. 1994;41:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guitian J, Thurmond M C, Hietala S K. Infertility and abortion among first-lactation dairy cows seropositive or seronegative for Leptospira interrogans serovar hardjo. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1999;215:515–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haake D A, Champion C I, Martinich C, Shang E S, Blanco D R, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding OmpL1, a transmembrane outer membrane protein of pathogenic Leptospirasp. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4225–4234. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4225-4234.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haake D A, Walker E M, Blanco D R, Bolin C A, Miller M N, Lovett M A. Changes in the surface of Leptospira interrogansserovar grippotyphosa during in vitro cultivation. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1131–1140. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.1131-1140.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haake D A, Chao G, Zuerner R L, Barnett J K, Barnett D, Mazel M, Matsunaga J, Levett P N, Bolin C A. The leptospiral outer membrane protein LipL32 is a lipoprotein expressed during mammalian infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2276–2285. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2276-2285.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haake D A, Mazel M K, McCoy A M, Milward F, Chao G, Matsunaga J, Wagar E. Leptospiral outer membrane protein OmpL1 and LipL41 exhibit synergistic immunoprotection. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6572–6582. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6572-6582.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haga Y, Ogino S, Ohashi S, Ajito T, Hashimoto K, Sawada T. Protective efficacy of an affinity-purified hemolysin vaccine against experimental swine pleuropneumonia. J Vet Med Sci. 1997;59:115–120. doi: 10.1292/jvms.59.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juillard V, Villefroy P, Godfrin D, Pavirani A, Venet A, Guillet J G. Long-term humoral and cellular immunity induced by a single immunization with replication-defective adenovirus recombinant vector. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:3467–3473. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klonjkowski B, Denesvre C, Eloit M. Adenoviral vectors for vaccines. In: Seth P, editor. Adenoviruses: basic biology to gene therapy. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes Company; 1999. pp. 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko A I, Galvao Reis M, Ribeiro Dourado C M, Johnson W D, Jr, Riley L W. Urban epidemic of severe leptospirosis study in Brazil. Salvador Leptospirosis Study Group. Lancet. 1999;354:820–825. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)80012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langoni H, de Souza L C, da Silva A V, Luvizotto M C, Paes A C, Lucheis S B. Incidence of leptospiral abortion in Brazilian dairy cattle. Prev Vet Med. 1999;40:271–275. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(99)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S H, Kim K A, Park Y G, Seong I W, Kim M J, Lee Y G. Identification and partial characterization of a novel hemolysin from Leptospira interrogansserovar lai. Gene. 2000;254:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marotto P C, Nascimento C M, Eluf-Neto J, Marotto M S, Andrade L, Sztajnbok J, Seguro A C. Acute lung injury in leptospirosis: clinical and laboratory features, outcomes, and factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1561–1563. doi: 10.1086/313501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ribotta M, Higgins R, Perron D. Swine leptospirosis: low risk of exposure for humans? Can Vet J. 1999;40:809–810. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saylers A A, Whitt D D. Bacterial pathogenesis: a molecular approach. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Segers R P, Van Der Drift A, de Nijs A, Corcione P, Van Der Zeijst B A, Gaastra W. Molecular analysis of a sphingomyelinase C gene from Leptospira interrogansserovar hardjo. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2177–2185. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2177-2185.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shang E S, Exner M M, Summers T A, Martinich C, Champion C I, Hancock R E W, Haake D A. The rare outer membrane protein, OmpL1, of pathogenic Leptospiraspecies is a heat-modifiable porin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3174–3181. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3174-3181.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smyth J A, Fitzpatrick D A, Ellis W A. Stillbirth/perinatal weak calf syndrome: a study of calves infected with Leptospira. Vet Rec. 1999;145:539–542. doi: 10.1136/vr.145.19.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sonrier C. Les antigènes de leptospires: caractérisation de fractions inductrices de protection homologue et croisée. Ph.D. thesis. Lyon, France: University of Claude Bernard Lyon I; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sonrier C, Branger C, Michel V, Ruvöen-Clouet N, Ganière J P, Andre-Fontaine G. Evidence of cross-protection within Leptospira interrogansin an experimental model. Vaccine. 2000;19:86–94. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson J C, Marshall R B. In vitro studies of haemolysis by Leptospira interrogansserovar pomona and ballum. Vet Microbiol. 1986;11:285–292. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(86)90030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trevejo R T, Rigau-Perez J G, Ashford D A, McClure E M, Jarquin-Gonzalez C, Amador J J, de los Reyes J O, Gonzalez A, Zaki S R, Shieh W J, McLean R G, Nasci R S, Weyant R S, Bolin C A, Bragg S L, Perkins B A, Spiegel R A. Epidemic leptospirosis associated with pulmonary hemorrhage—Nicaragua, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1457–1463. doi: 10.1086/314424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuerner R L, Herrmann J L, Saint Girons I. Comparison of genetic maps for two Leptospira interrogansserovars provides evidence for two chromosomes and intraspecies heterogeneity. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5445–5451. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5445-5451.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zuerner R L, Knudtson W, Bolin C A, Trueba G. Characterization of outer membrane and secreted proteins of Leptospira interrogansserovar pomona. Microb Pathog. 1991;10:311–322. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]