Abstract

In the area of company economy, consumer behaviour and consumer attitudes to consumption and debt have been the subject of study ever since this discipline came into practice. This publication is a result of an initial work that provides a conceptual analyses and review, within a line of research that the authors are developing, the aim of which is to establish the characteristics that determine the current consumer behaviour and the actual patterns of conduct that make it possible to devise a new contextual psycho-economic model with regard to consumer behaviour. This work is an exhaustive theoretical review of the numerous authors, theories and models concerning consumer behaviour considered from 1935 to 2021.

Keywords: Behavior, Brand, Company, Consumer, Economy, Models, Psychology

1. Introduction

Jacoby, Johar & Morrin (1998) state that the origin of research into consumer behaviour are to be found Psychology and that it gave rise to a new line of research known as Social Psychology. At first, works were developed with such concepts as attitude, communication and persuasion. Once Social Psychology was accepted as being an important subject it received adherents who promoted work under other constructs, with research into memory, data processing and decision-making [1] (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Main theoretical consumer behavioural models 1935–2021.

| Nº | Model | Year | Author | Main Findings | Type of Model |

Type of Approach |

Pros | Cons | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microeconomic | Macroeconomic | A priori | Empirical | Eclectic | |||||||

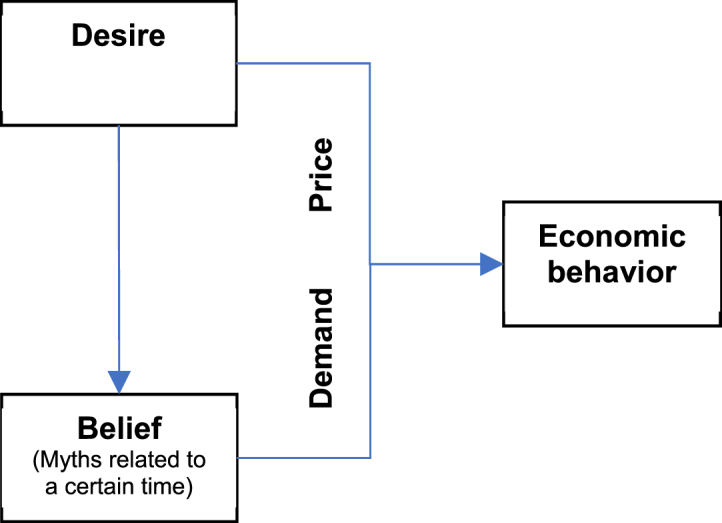

| 1 | Model for the psychological theory of the Underpinnings of Economic behaviour [2] | 1935 | Gabriel Tarde | The suppositions in the theory of the Underpinnings of Economic Behaviour are: (1) Economic behaviour is the result of the combined action of two psychological causes; desire and belief.

|

Its hypothesis was the first effective attempt in the 20th Century to explain economy from different angles: the consumer is a being made of desires and appetites who believes, rightly or wrongly, in the aggregated use of the desire when it is achieved. Within this same perspective, the value of money emerges as a combination of subjective influxes: beliefs, desires, ideas and wills. In such a way that, in the words of Tarde (1935) “economic fluctuations, unlike a barometer's fluctuations, cannot be explained without considering their psychological causes” [2]. | It falls short, because it only considers belief tangentially. | |||||

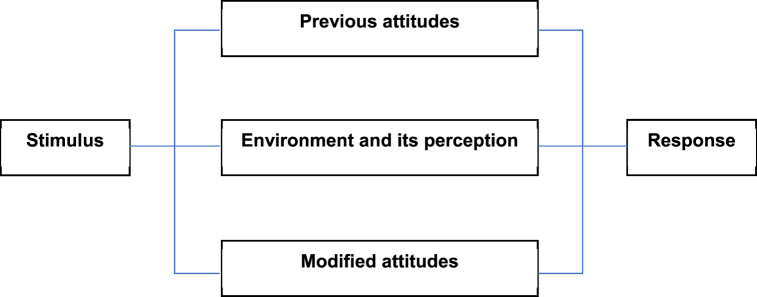

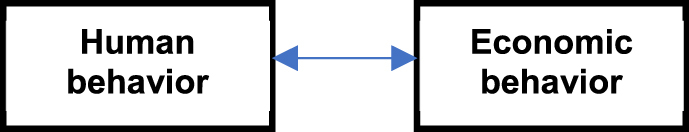

| 2 | Psychological Analysis of Economic Behaviour Model [3] | 1951 | George Katona | The variables interact like that: (1) Psychological variables (Ps) mediate between economic stimulus and behavioural responses (Ps).

(6) As a consequence, consumers' behaviour (B) has an influence over the economic situation (E) with their purchases or their savings. And this interfered with by psychological variables (Ps), has an effect in situations of depression or growth, over the consumer's behaviour (B). |

It includes the classic economic analysis, the psychological variables, especially what is related to attitudes and expectations. | It views mass consumption society as an open dynamic system, given that for him, consumers are not merely passive receivers of the system, but active member who influence it. This perspective, clearly cognitive, places the consumer in an outstanding and active position, invalidating the simplicity of the previous models, e.g., Tarde's Model. The aforementioned does not allow for continuity in the construction of models that contain similar variables. | |||||

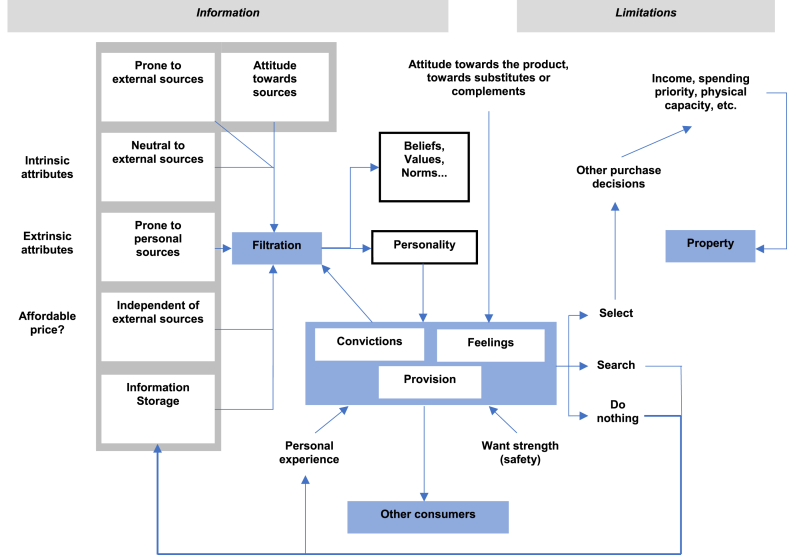

| 3 | Consumer Behavioural Model [4] | 1965 | Andreasen | The process described by Andreasen involves 4 states: internal stimulations, perception and filtering of the information, being prepared to change attitude and, finally, the feasible results. The information perceived by the consumer about the product is obtained via the 5 senses, the messages can be personal or impersonal. The potential consumer's first filter is his/her own perception of these messages, whereas the attitudes will function as a determining factor that will allow or disallow the information to keep flowing. | The model takes into account the fact that every new piece of information or change in the environment can have an effect on the consumer's attitudes and feelings. The consumer's decisions are affected beyond his/her cultural values, personality, desires and experience. | The model has its limitations, including the fact that it is not clearly indicated which type of interaction exists between the consumer and the brand, product or service. It seems that this model only has one communication channel, feedback for products that are not new (for example) are sidelined or hardly explained. Another criticism levelled at the model seems to be that the variables that are taken into account are always weighted towards the attitudes of the consumer, rendering other types of variables too weak, when they could be just as influential. | |||||

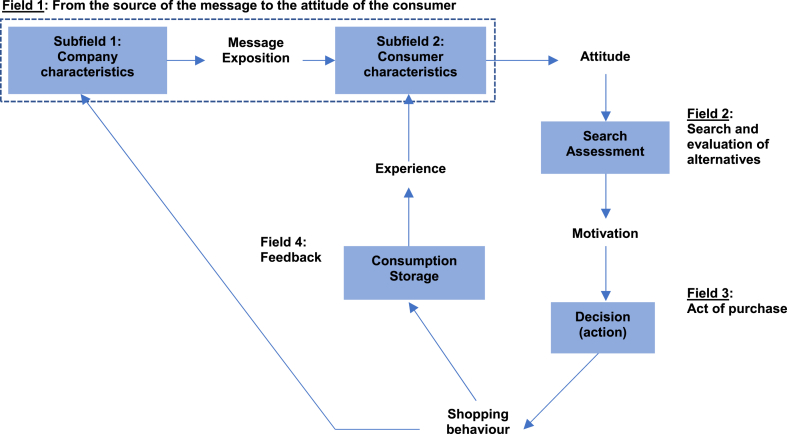

| 4 | Consumer Behavioural Model [5] | 1966 | Nicosia | The model describes a circular flow with more than one option of influences in which each component leads to the next one, where consumers behave in an increasingly active way throughout the consumption process, gradually acquiring knowledge about the product they wish to obtain, and eventually having specific information about the brand that best meet their needs, representing a situation where there are communications (adverts, products, etc.) to the target, to affect their behaviour. In general terms, the model contains 4 major fields:

|

This model makes an outstanding contribution to consumer study [6]. Not only because of its innovative approach, by considering conscious and intentional behaviour, but also because it sees the act of purchasing as yet another stage in the consumption process. It also includes the company's influence in the purchase decision process, and Feedback also exists in its own right. | It can be seen that the model's flow, of a computer nature, is sometimes restrictive and the way it processes the consumer's numerous internal factors is far from complete. Attempting to validate it is fraught with certain difficulties [7]. It does not envisage all the internal factors that affect the consumer's behaviour, and neither does it consider any type of the individual's predisposal towards an object (brand) in particular at the beginning of the consumption process [6]. |

|||||

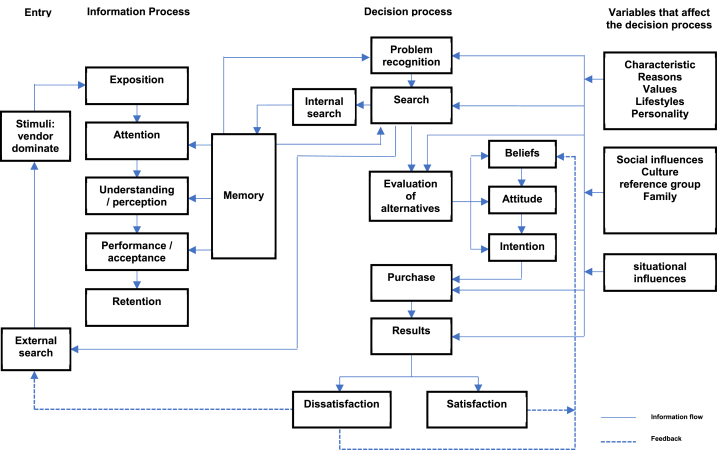

| 5 | Consumer Behaviour and Decision-Making Model [8] | 1968 | Engel, Kollat & Blackwell | The model's main features are as follows:

|

It is one of the most emblematic representations of consumer behaviour. | It tends to understand the decision-making process too schematically. | |||||

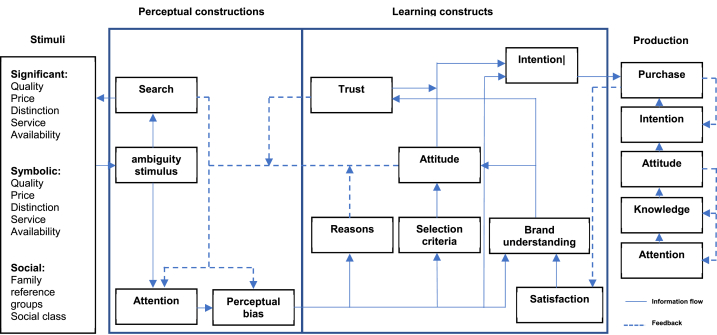

| 6 | Purchaser Behavioural Model [9] | 1969 | Howard & Sheth | This model forms the basis for a general integrating theory for consumer behaviour, because it tries to describe the rational choice behaviour of certain purchasers in conditions where information is incomplete and capacities are limited, 3 levels of decision-making being distinguished:

|

The model identifies many of the variables that influence consumer behaviour and provides a detailed description of how some interact with others. Moreover, and for the first time, the model explicitly recognises the various types of behaviours when searching for information and solving problems. It also recognises that the results of the consumer's decisions are more than mere purchases. | It is often criticised for the limited explanation that is given for the it gives relations considered between the variables involved in the consumption process [10]. And although it has been tested empirically, it is also criticised for its lack of ability to predict [11]. | |||||

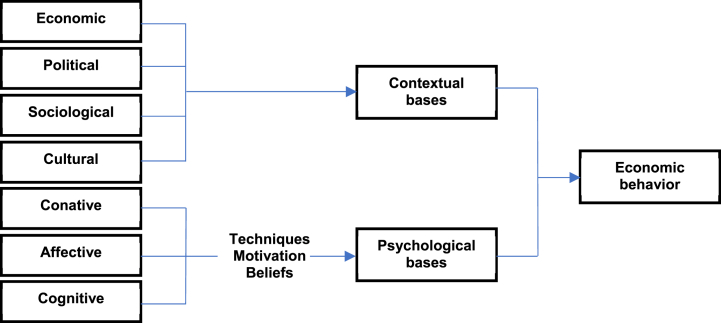

| 7 | Ternary and Graphical Previsional Model [12] | 1978 | Paul Albou | The model by Albou (1978) can be broken down into 2 parts [12]:

|

It is a qualitative model that enables its users to understand how the economic agents react in the presence not only of internal stimuli (psychological aspect) but also from context. | It does not allows for quantitative analyses to objectively determine causality relations. | |||||

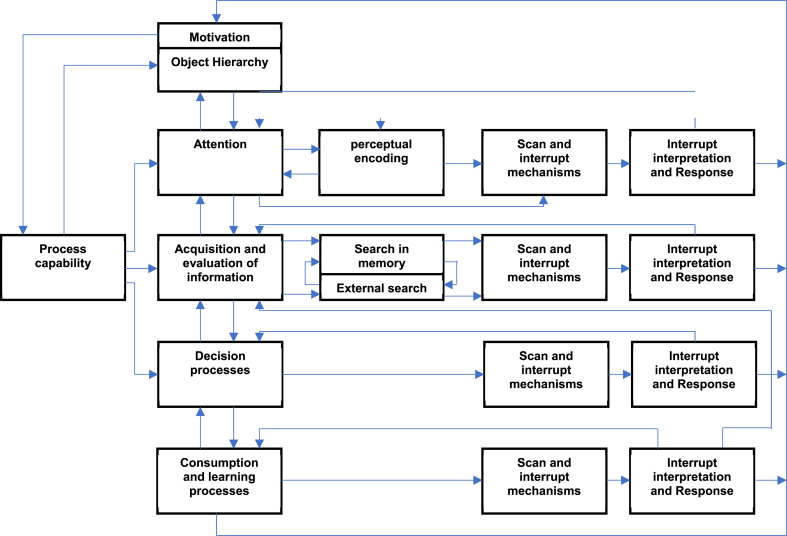

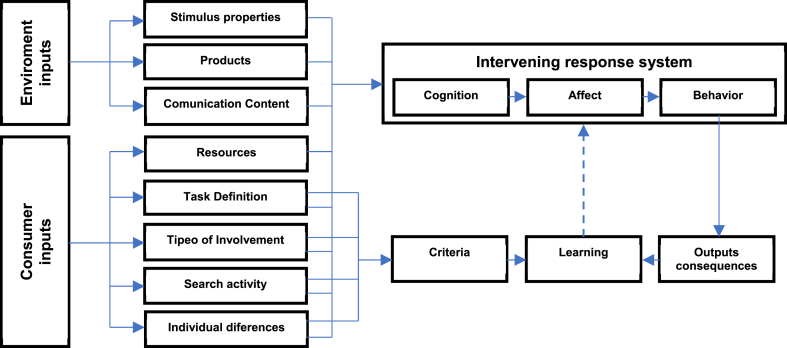

| 8 | Information Processing Model [13] | 1979 | Bettman | The consumer behavioural model by Bettman (1979) is known for specifically tackling the processing of information [13]. As it pays close attention to the individual's cognitive processes, Bettman (1979) provides a simplified description of consumption behaviour, which is considered to be a process of decisions taken by means of simple and individual strategies [13]. Consumption behaviour is considered to be a cyclic process whereby consumers seek and assess information, selecting and deciding from different options, acquiring and learning about a product, and applying consumption experience to future behaviours. Furthermore, the consumption process is explained under the assumption that an individual's processing ability is limited. Therefore, it is assumed that consumers do not use complex analyses when making decisions about consumption, but use strategies that simplify the process. The decision model by Bettman (1979) consists of a series of flow charts containing 7 basic components [13]:

|

Bettman's model provides an original and complete structure of the consumption decision process, identifying most of the variables that affect it [9]. It also stands out because of the special attention that is paid to the consumer's cognitive processes and to the processing of the information. | It has a few drawbacks, mainly owing to the difficulties involved in validating the model; these are caused by its complexity and limited operability [14]. | |||||

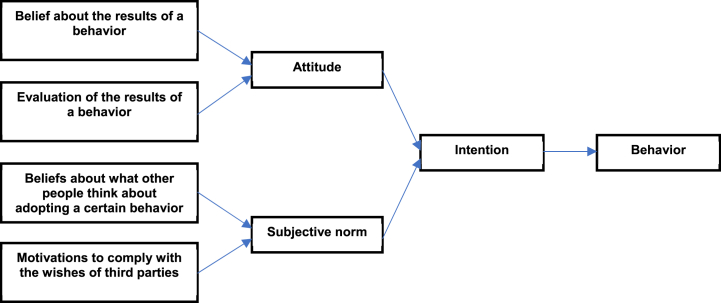

| 9 | Theory of Reasoned Action Model [15] | 1980 | Ajzen & Fishbein | According to the model proposed, individuals act rationally using the knowledge they have, for the purpose of which they systematically use the information they receive. Moreover, it is assumed that the intention to behave (or not to) in a certain way is the best variable for predicting such behaviour, that the intention is determined both by the attitude to that behaviour and by that individual's subjective standard; that not only the attitude but also the subjective standard are preceded by the ideas and regulatory beliefs, respectively. | It enables the user to consider certain factors that hitherto had only been envisaged occasionally, and facilitates an understanding of the behaviour determinants. | It is unable to predict, especially behaviour that occurs habitually and behaviour where individuals are not as aware of the decision process they are carrying out [16]. | |||||

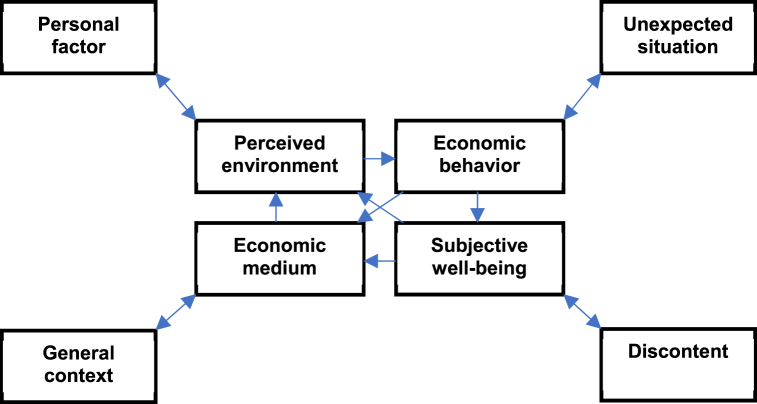

| 10 | Economic Behaviour Integration Model [17] | 1981 | Fred Van Raaij | This model proposes to integrate the economic variables with the psychological variables, persisting in considering the feedback between economic behaviour and the context conditions [18]. The variables in the Economic Behaviour Integration Model by Fred Van Raaij (1981) are defined in the following way [17]:

|

Integrating the economic variables with the psychological variables, allowing for a host of combinations at the same time, which can serve as the basis for more specific models that can be incorporated into it, and it makes significant progress since the model by Katona (1951) because it contains interaction with new elements [3]. | It insists on the need to consider the feedback between economic behaviour and the conditions of the environment. | |||||

| 11 | Consumer Experimental Model [19] | 1982 | Holbrook & Hirschman | Their experimental study researches into the effects of a basic aspect to advertising content concerning the components of the structure of attitude. To be specific, the findings suggest that the factuality/evaluability of a persuasive message has a positive effect on the beliefs considered to be most important; that such beliefs also determine the effect; and that these effects of the communication on the components of attitude are mediated by a set of cognitive reactions, such as the perceived credibility of the message. | The findings suggest implications for marketing decisions, public policies and the future course of research into marketing attitudes [20]. | Market research has focused too much on the static structure of attitude at the expense of its informative determinants. | |||||

| 12 | Dynamic Discrete Choice Model [21] | 1985 | Rao & Vilcassim | One main objective of consumer research is to predict the choices made by an individual consumer or a group of consumers when the conditions that affect choice change. Rao & Vilcassim (1985) present a unified approach for modelling dynamic discrete choice, which includes the two main approaches in the literature: the econometric approach of qualitative choice and the modelling of stochastic choice [21]. | Rao & Vilcassim (1985) have developed an integral model to analyse the consumers' discrete choices throughout time [21]. | The two available approaches for analysing dynamic discrete choices, the stochastic model concerning purchaser behaviour and the probabilistic models for discrete choice, are special cases for their model. | |||||

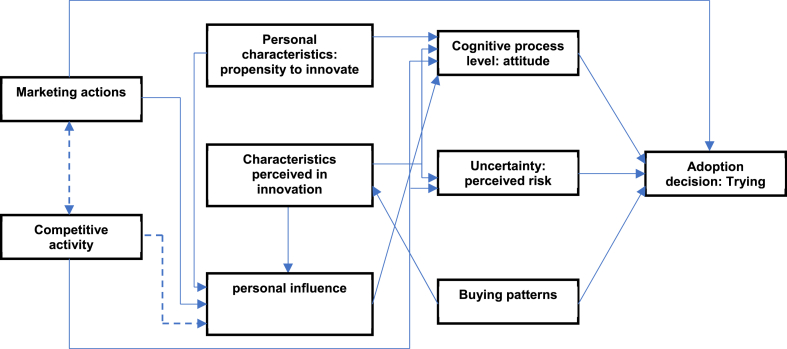

| 13 | Innovation Adoption Model [22] | 1985 | Gatignon & Robertson | Gatignon & Robertson (1985) conceive the adopting of an innovation, or of a new behaviour, as a multi-dimensional process, because its manifestation does not depend upon one single decision, but is related to different elements that interact with each other: the attitudes to the innovation, the risk perceived regarding adopting it, previous purchasing patterns, personal characteristics, the characteristics perceived in innovation, personal influence, the marketing activity and the competitive activity in the market [22]. | Gatignon & Robertson (1985) include as indirect adoption constraints, the individuals' perceptions of the innovation's characteristics [22,23,24,25], the influence of third parties [26,27] and the individuals' propensity to innovate [28,25]. [29]. [30,31,32]. | The empirical evidence obtained by Eastlick & Lotz (1999) in the area of online purchasing seems to endorse the adoption model proposed by Gatignon & Robertson (1985). However, it does not take into account the influence of the reference groups or persons [33,22]. | |||||

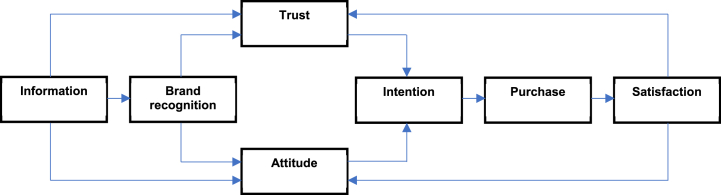

| 14 | Consumer Decision Model [9] | 1989 | Howard | The model by Howard & Sheth (1969) was reviewed and completed by Howard (1989) himself with a view to making it easier to understand and to simplify it [9,34]. Paying attention to evolution of the product in the consumer's behaviour, the model's development is based on 7 elements that are involved in the consumption process and their relations: information, brand recognition, attitude, trust, intention, purchase and purchase satisfaction. According to John Howard, his Model called Consumer Decision Model (CDM) only contains 6 components and the relationships between them; these are preceded by satisfaction, which would be a final variable in the model [9]. |

Howard's Model provides a systematic explanation of the individuals' purchasing process [35] while at the same time showing a high ability to predict, because it is simple and can be applied to simulations. | The model may not have the same prediction power for general or brandless products or services. | |||||

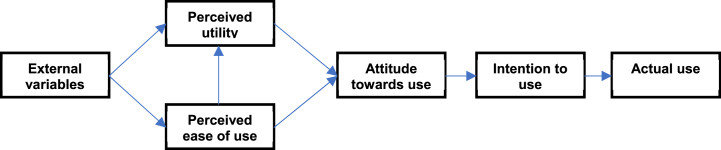

| 15 | Technology Acceptance Model [36] | 1989 | Davis, Bagozzi Warshaw | On the one hand, the model considers two of the main extrinsic reasons (beliefs) that determine acceptance and use of information & communications technologies (ICT): the perceived usefulness and simplicity of use. The first of these is defined as the extent to which the use of a particular system improves the result of the individual's tasks or activities; and the second, the extent to which the use of that system is effort-free [37]. The two are associated –thus, for example, it is more likely that an easy-to-use website is regarded as a useful website [38]– and determine the individual's attitude to the use of technology. This relationship is built on the basis of the theory of reasoned action, according to which attitudes to behaviour are determined by beliefs [37,36]. On the other hand, it is considered that the attitude to use of technology is positively related to intention to use; and this, in turn, to actual use. So, an individual's attitude to technology ends up by affecting his/her actual use [39]. Moreover, intention to use is also affected by perceived use. External variables are also considered, such as documentation or the advice given to the user, which exerts an influence on the perceived use and simplicity of use. | The model stands out because of its contributions to behaviour when using new technologies and, particularly because it considers the effects that external factors have on beliefs, attitudes and intentions [36]. It has been backed up by many research works [40,39,41,42]. | It has certain limitations caused by the limited number of variables included as determinants of attitude to use [41]. | |||||

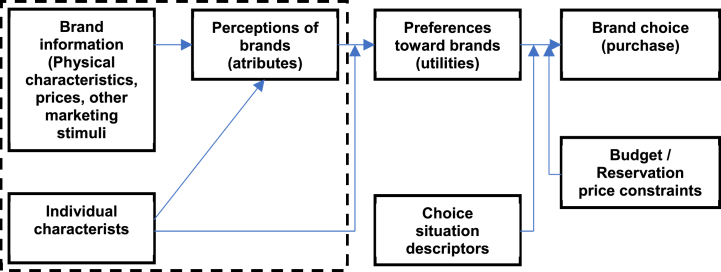

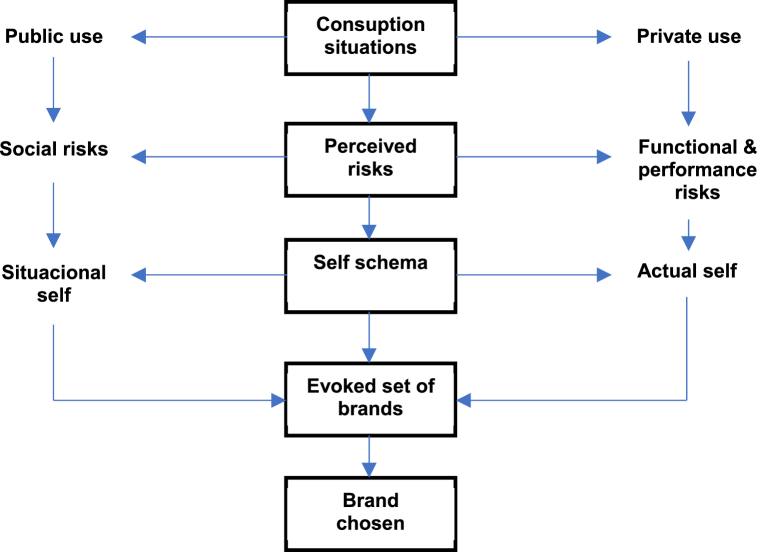

| 16 | Brand Choice Model [43] | 1990 | Lee | The model integrates the many dimensions to self-concepts into one single construction under the framework of symbolic interaction as is applied to the product symbolism. Specifically, the self-concept is defined in a way that is broad enough to incorporate the socially-oriented (situational yo) self-concept and the psychologically-oriented (actual yo) self-concept. | The Brand Choice Model by Lee, D.W. (1990) contributes to providing knowledge about such variables as the consumer's self-concept and research into product symbolism in several ways. The model introduced the concept of perceived risk that has been used in many marketing studies [43]. | Although the model is expected to improve our understanding of the consumer's brand choice behaviour and to improve the prediction of brand choice in certain categories of specific products, it undoubtedly has its shortcomings. As an initial attempt to introduce the symbolic interactionist perspective into consumer behaviour research, the approach has been in the conceptualisation of the “situational yo” and in applying the consumer brand choice concept. So, the scope of the model is not broad, because it does not take into account individual differences. It is highly likely that consumers differ in their perception of product conspicuousness. Such constructions as self-awareness [44] and self-control [45] could add further information if they are integrated into this framework in future research. The model proposed is also very specific as regards product category and the consumption situation to which it can be applied, being so specific as to also suggest how to put into operation and measure the two dimensions of the yo. | |||||

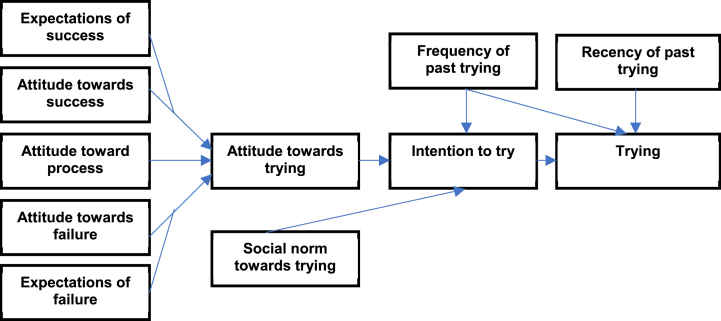

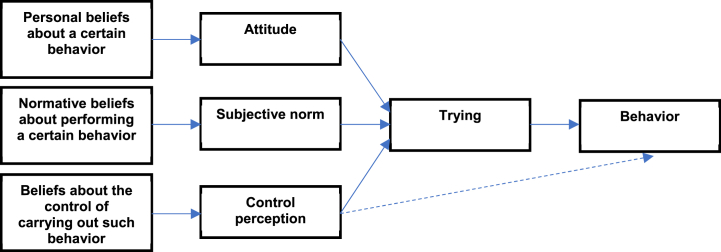

| 17 | Theory of Trying Model [46] | 1990 | Bagozzi & Warshaw | The model by Bagozzi & Warshaw (1990) takes into account the individual's previous behaviour, so it includes the frequency with which he/she behaved in the past and the time that has elapsed since he/she last tried to do it. And although both variables affect behaviours aimed at a specific objective, only the first of these is held to be a determinant of intentions [46]. | According to Bagozzi & Warshaw (1990), to explain the behaviour of individuals it is necessary to take into account their aims. In fact, their model does this through a new variable (trying to behave) which refers to the different attempts that the individual makes to behave in a way when it is by no means guaranteed that he/she will succeed [46]. | This model does not try to explain behaviour as much as the attempt to behave. | |||||

| 18 | Dual Causation Paradigm Model [47] | 1991 | Lea, Tarpy & Webley | The model considers that: (1) Economic behaviour is subjected to a twofold causation, which means certain types of economic behaviour determine the course of affairs in this matter. At the same time, the economy, as a social reality, exerts a major influence in human behaviour.

|

It is the organisation of facts, assumptions, explanations and research into the diverse theories postulated in economic psychology, focusing on the needs for a comprehensive theory of economic behaviour and on the questions that this can still not answer. | The dual causation paradigm [47] is not, in itself, a model according to the concept of its own authors. | |||||

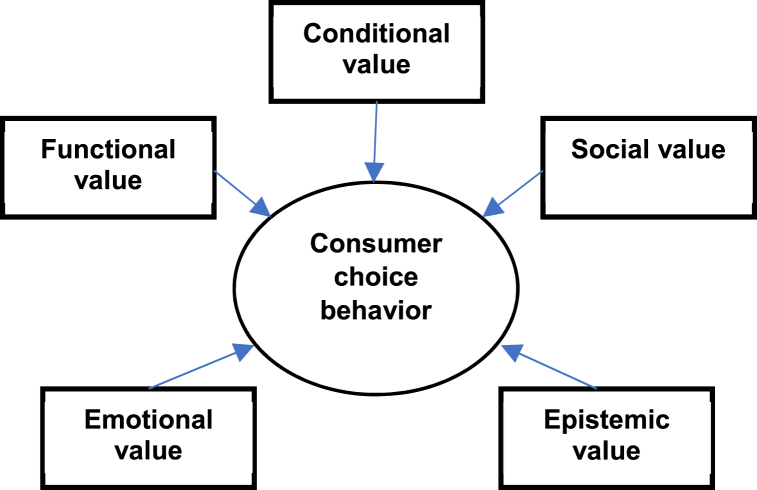

| 19 | Model of Consumption Values [48] | 1991 | Sheth, Newman & Gross | Sheth, Newman & Gross (1991b), consider that the consumer's choice is based on a function of multiple consumption values, more specifically, it is based on 5 value dimensions: functional, social, emotional, epistemic and conditional [48]. Sheth, Newman & Gross (1991a), supplemented by Lin & Huang (2012) also believe that apart from the proposition that the consumer's choice is a function of many consumption values, there are two other propositions consider to be essential when tackling the question of consumption values [49,50]:

|

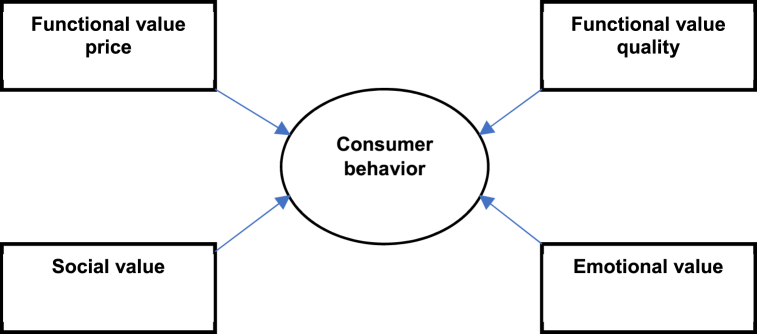

The consumption values theory can be used to predict consumer behaviour, and more than that, this theory can also describe and explain this behaviour. So, it must be pointed out that this theory can be applied to different product categories, and it has a prediction validity regarded as excellent in more than 200 situations already analysed [52]. All of this ends up by endorsing the importance of this theory in understanding the factors that influence consumer behaviour and stressing the numerous dimensions of consumption values to the detriment of the utilitarian and hedonic values studied before. | The model is constructed from the appraisals made by consumers themselves at the sales outlet, beyond theoretical definitions and conceptualisations. | |||||

| 20 | Planned Behaviour Theory Model [53] | 1991 | Ajzen | The model considers intention as an intermediate variable between attitudes and behaviour, which is the result of an intentional cognitive process. It also takes into account attitude and subjective standard as determinants of behaviour intention, incorporating a third factor, concerning the individual's perception of control over behaviour. This variable is considered [54,55] to be an indicator of the potential obstructions perceived between intention and behaviour [56], so it helps to explain both of them. Purchase prediction is affected by the incidence of perception of control over purchase intention. The ability to predict behaviour and the possibility of carrying it out increases as the individual's control over behaviour increases [57,53,15]. Apart from considering beliefs, personal or regulatory, regarding a particular behaviour, it takes into account the individual's beliefs about the possibilities of control over a behaviour. This latter type of belief is associated with the resources, skills and opportunities the facilitate or prevent that behaviour taking place [58,53]. | The theory of planned behaviour [55] is recognised because of the validity of its model [59,60,61,62,63,64,16]. It has proved useful in studying different types of behaviour, having obtained a great deal of empirical evidence, that shows the importance of perceived behaviour control and its effect on intention and behaviour [65,66]. | It has certain limitations, such as those that arise from considering a limited number of variables [46,67,68]. Moreover, it does not sufficiently define the type of relationship that is established between the determinants of intention. | |||||

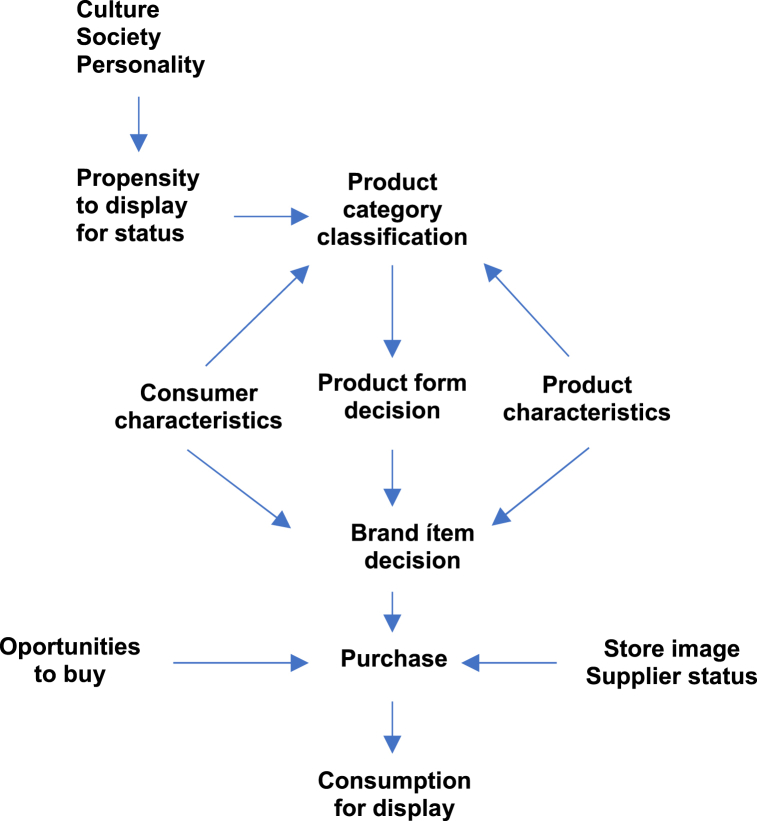

| 21 | Demand for Status Goods Model [69] | 1992 | Roger Mason | Mason (1992) developed a conceptual model of market behaviour that examines the processes of searching, assessing and selecting through which status goods are purchased and consumed [69]. | The individual consumer will move through purchase and consumption intention. | Quest for status behaviour is greater in societies where the emphasis is placed on social status and in searching there is a tendency to consume to exhibit. | |||||

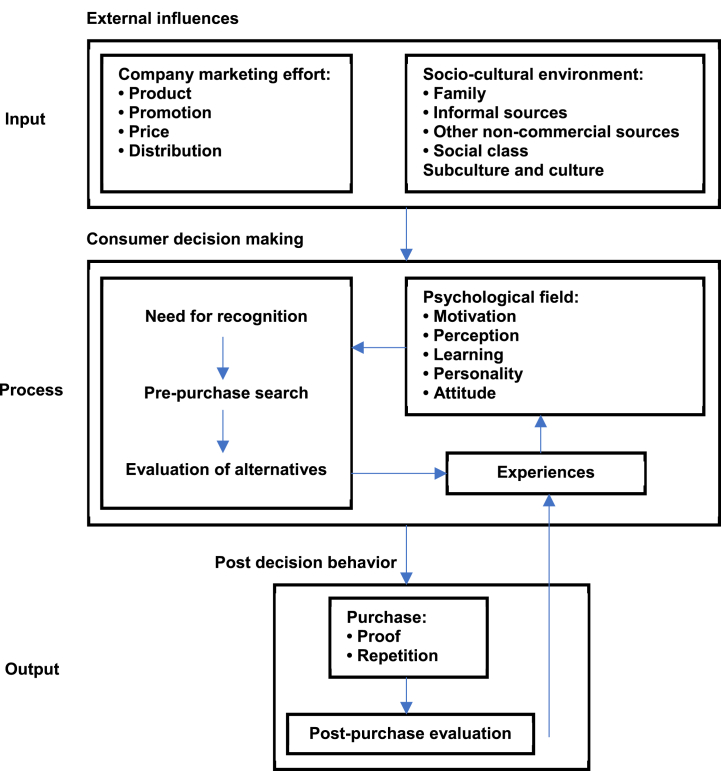

| 22 | Basic Consumer Decision-Making Model [70] | 1993 | Schiffman & Kanuk | According to Schiffman & Kanuk (1993), the input phase influences consumers so that they accept that they need a product or service [70]. This acceptance comes from two main sources of information: the company's marketing efforts (product, promotion, price and distribution channels) and the external sociological influences (family, informal sources, social class, culture and subculture) on the consumer. The so-called process phase, focuses on the way in which decisions are made (acceptance of the need, searching before purchase and assessment of options), where the psychological factors inherent to each individual influence (motivation, perception, leaning, personality and attitude). The output phase consists of two main activities: purchase behaviour and subsequent assessment after the purchase. The marketing efforts made by the companies to influence the consumer can be observed in this model. | The model is so all-encompassing that it can take in not only simple decisions but also complex ones. | The model does not aim to take in complex decisions, but to simplify the approach to decision-making. | |||||

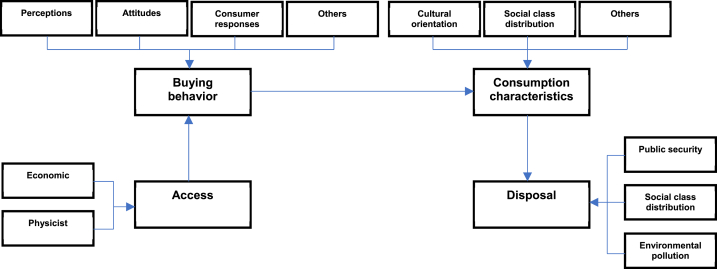

| 23 | A-B-C-D Paradigm Model [71] | 1995 | Raju | To understand consumer behaviour in any global market, Raju (1995) proposed the A-B-C-D paradigm (Access-Buying Behaviour-Consumption Characteristics-Disposal) [71]. The four aspects considered in the initials stand for the four sequential stages used to represent the purchasing and consumption processes in any culture, so:

|

This paradigm can be applied universally in any culture, because it includes all the purchasing and consumption aspects within a fairly simple and specific framework, which can be seen in its hierarchical form, which has been organised from the consumers viewpoint. | The model is an effective tool in which all the market functions are implicit, as long as there is an in-depth understanding of each one of the stages involved. | |||||

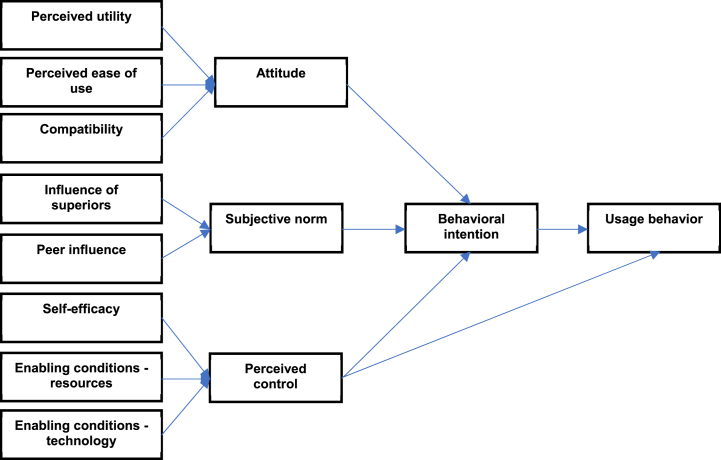

| 24 | Decomposed Theory of Planned Behaviour Model [41] | 1995 | Taylor & Todd | Attitude is considered to mean the individual's predisposal (positive or negative) to adopting the new technology, and it is thought to be conditioned by its perceived usefulness, how easy it is perceived to use it and compatibility. The perceived use is defined as the extent to which an individual believes that by adopting a certain technology, he/she will improve the results of his/her tasks or activities. Perceived ease of use means how difficult the individual perceives that it will be to use the technology [37]. Compatibility is associated with the extent to which the innovation adapts to prior experiences that the individual has had, his/her values and requirements. | The model by Taylor & Todd (1995) increases the predicting power of the model by Schifter & Ajzen (1985), by including the innovation characteristics [55,41]. It also provides a better understanding of the real nature of the technology acceptance model [37] because it includes the aspects concerning the subjective standard and perceived control [72]. | The main drawbacks to the model by Taylor & Todd (1995) are consideration of the interrelations between the sets of beliefs that affect attitudes, the subjective standard and perceived control regarding behaviour [41]. So, it is to be expected that ease of use has a bearing on the perceived usefulness as is established by the Technology Acceptance Model [37,36]. Furthermore, Taylor & Todd (1995) have detected high correlation levels between perceived usefulness, the influence of the different reference groups and self-efficacy and the facilitating conditions [41]. | |||||

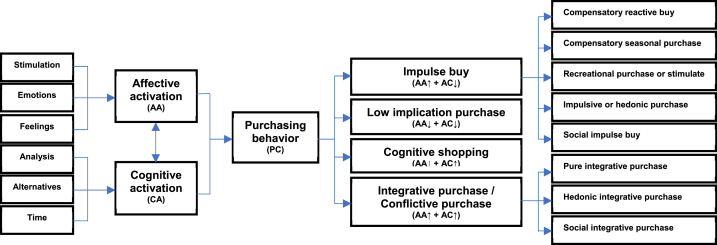

| 25 | Cognitive -Affective Purchase Model (CAC) [73] | 1998 | Quintanilla, Luna & Berenguer | This is a structural model, considered by Quintanilla, Luna & Berenguer (1998) that attempts to categorise different experiential purchase states on the basis of their affective and cognitive activation, considering that both high cognitive and high affective activation can be states with high consumer involvement [73]. It is not only structural because of the composition of the elements that come into play in the types of purchase but it also permits those structures to be composed of functional purchases made by the consumer, as will be explained later. The CAC model is a conceptualisation of impulse buying and purchasing in general that envisages, through a simple scheme, the basic elements involved in purchasing behaviour, cognitive purchasing and affective purchasing. Different purchasing styles emerge with these coordinates and they characterise most of our purchase behaviours as consumers. |

The main advantage we get from the CAC structural model is that it clearly makes it possible to display the forces involved without valuing the symbolic content they express. So, as a result of this model, its applied and functional aspect enables the user to distinguish between many types of purchasing behaviour that occur normally in the consumption market. | The CAC structural model [73] enables the user to make a distinction between the personal elements involved in purchasing. This classification is simple and theoretical at the same time, enabling the user to subsequently develop what is known as the CAC functional model, where purchase typologies are established on the basis of the structures involved. | |||||

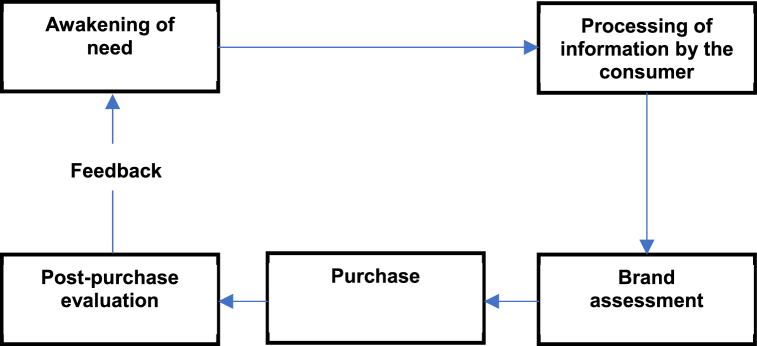

| 26 | Consumer Purchase Decision Model [74] | 1998 | Assael | The model proposed by Assael (1998) begins with a need, which arouses the wish to satisfy that need, so the potential consumer starts the process of seeking and receiving information. In doing so, he/she carries out a brand assessment, and later decides on the purchase and makes a post-purchase assessment [74]. | Although his Model is clearly simple, it has had a great impact on the principles of Marketing, because in many cases it became the iconic blueprint used to explain, in simple terms, the consumers' decision-making process. | The way it is designed takes Feedback into account, albeit not within the 5 stages described in the Process. | |||||

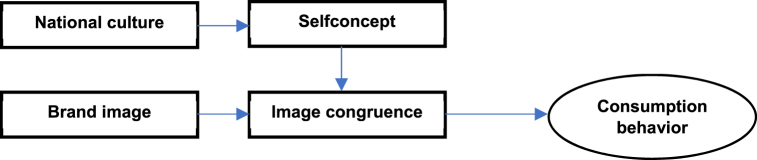

| 27 | Consumer Behaviour Symbolic Culture Model [75] | 1999 | Páramo | This model [75] considers the relationship between national culture, the consistency between self-concept and image, and consumer behaviour. Its main approach consists of the impact that national culture (the approach made by Hofstede, 1980) has on consumer behaviour via the concept of self-congruence [76]. National culture and brand image will be considered as separate and independent variables. | The self-concept will depend on the national culture, and image congruence will be a measurement of the similarity between self-concept and brand image. Consumer behaviour will depend on the degree of image congruence [75]. | Studies concerning self-concept in an international context have hardly ever been undertaken [77,78,79], which allows this model to integrate the analysis of self-concept from the perspective of the proposed product's symbolism. | |||||

| 28 | Perceived Value Model – PERVAL [80] | 2001 | Sweeney & Soutar | Sweeney & Soutar (2001) developed a model with a view to explaining the values that affect decision-making when certain consumers make choices [80]. Great importance is attached to the perceived value model (PERVAL) in measuring the value perceived by the consumer, because it enables the multidimensionality of the construct value to be compared empirically [81]. | This model, developed by Sweeney & Soutar, 2001, has a scale with 19 variables, and the model was tested on long-lasting consumption goods in Australia [80]. This PERVAL scale has habitually been used in studies associated with value as perceived by the consumer and is one of the most effective tools for these types of studies [82]. | It can be seen in this model that Sweeney & Soutar (2001), do think that certain values, epistemic value and conditional value, are not important, when they do affect consumer behaviour [80]. | |||||

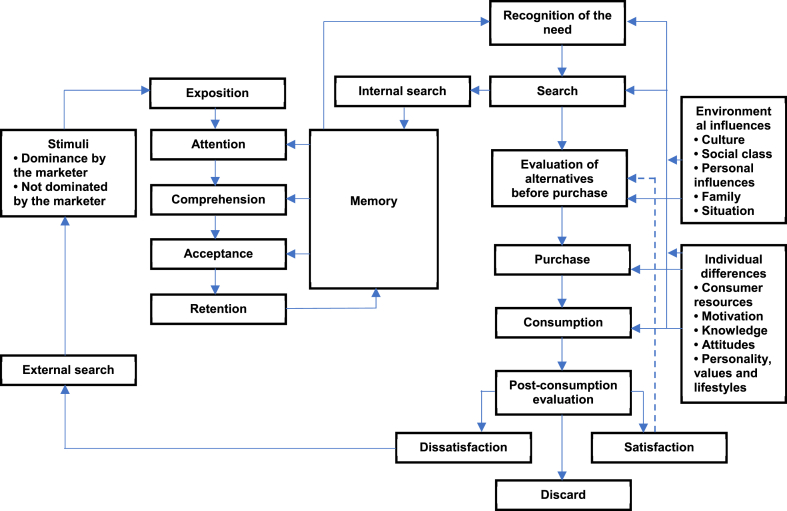

| 29 | Consumer Decision-Process Model [83] | 2002 | Blackwell, Miniard & Engel | Blackwell et al. (2002) stresses that what is bought and used is finally the result of some kind of decision [83]. They point out that if this decision is to be more reliable and appropriate, instead of allowing oneself to be led by just a set of indicators, it is better for the purchaser to base their decisions on something more complete and integral such as a map. These authors think the Consumer Decision Process Model is: a map of the consumers' minds, that the marketers and managers use to guide the mixture of products, the communication and sales strategies [83]. | X | The model shows in diagram form, the activities that take place when decisions are made, showing how the different internal and external forces interact and how they affect the way in which consumers think, assess and act. | In this model the consumer's decision is affected by marketing stimuli that may or may not be from the interested company's domain. | ||||

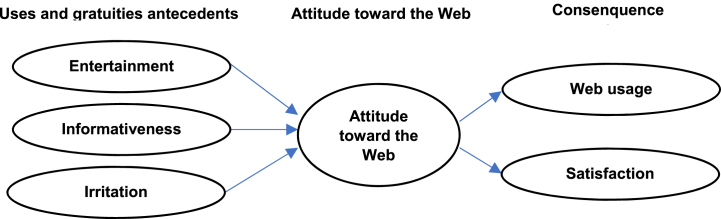

| 30 | Uses &Gratifications Theory Model in the context of e-consumer behaviour [84] | 2002 | Xueming Luo | The model predicts the use of the Web and consumer satisfaction, on the basis of the attitude to the Web, but conceived from three dimensions that include entertainment, information and irritation. The U&G Theory has many underlying constructions. In the literature, the most important and soundest aspects of the U&G Theory include entertainment, information and irritation [85] [86] [87,88] [89] [90,91]. | One basic assumption inherent to the U&G Model is that users actively participate in the use of the media and interact closely with the communication media. | Given that the interactive nature of the Web requires considerable consumer participation, applying the Uses & Gratifications Theory to improve our understanding of e-consumer behaviour would appear to be valid [89]. | |||||

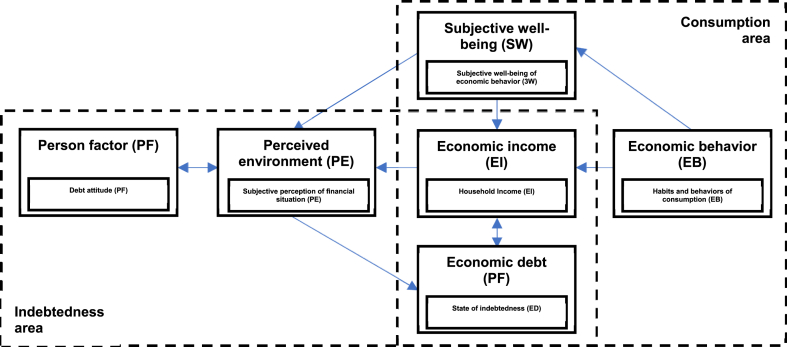

| 31 | Consumer Psycho-economic Model (MPC) [92] | 2005 | Rodríguez-Vargas | In all the approaches made by Ortega & Rodríguez-Vargas (2005), what makes their subsequent validation easier and allows them to be applied to any economic environment, is the tested validity of their scales [[93], [94], [95], [96]] and the fact that they are linked to a sound theory. Rodríguez-Vargas (2006) structure the Consumer Psycho-economic Model from a holistic and comprehensive perspective, but above all it is objective and measurable, and the following variables are interrelated: Nuclear Family Income, Consumption Habits, Subjective Well-Being with the Consumption Style, State of Indebtedness, Perceived Financial Situation, Attitude to Indebtedness [97]. | X | One of the advantages of this model is that its approach is rather globalising and this makes it possible to suggest more specific models integrated into it. | Some of the opportunities to obtain a more integral and complete model is to include variables associated with the context, the self-concept and the effect of the brands. | ||||

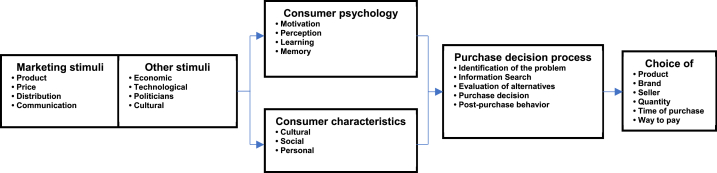

| 32 | Purchase Behaviour Model [98] | 2006 | Kotler & Keller | Kotler & Keller (2006) find that marketing stimuli are composed of the following variables: product, price, distribution and communication [98]. Other stimuli are also involved in the process, namely the so-called variables external to the purchaser: economic, technological, political and cultural. All the variables in the model enter the consumer's black box, where they become an observable purchase response, which can be: product selection, brand selection, distributor selection, purchasing moment and purchase amount. While the researcher wants to understand the way in which the stimuli turn into responses, within the black box that is the consumer, the latter responds modulated by their characteristics of a cultural, social, personal and psychological nature. |

X | The marketing stimuli and the stimuli of other factors enter the consumer's black box and cause certain responses. | The stages in this model occur mainly when the consumer is faced with a new and complex purchase situation, but not when he/she is faced with routine purchases or when then the consumer is loyal to a brand. | ||||

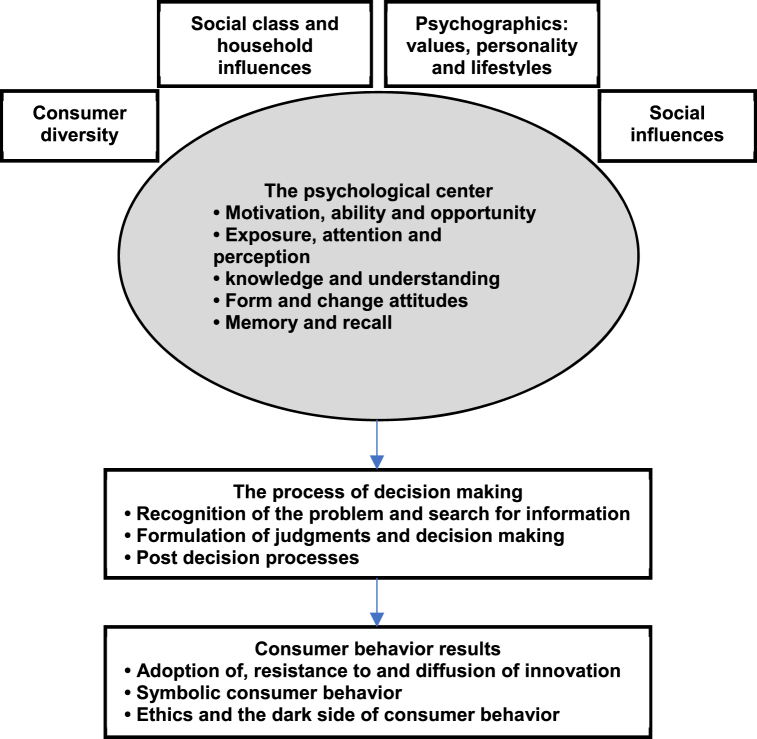

| 33 | Consumer Purchase Behaviour Model [99] | 2010 | Hoyer & McInnis | Hoyer & McInnis (2010) state that consumer behaviour takes in 4 areas, each one of which is associated with all the others [99]. Their model focuses on what they call the psychological centre, where they consider that when making their decisions, consumers must show the following: motivation, skill and opportunity; exposure, attention and perception; a knowledge and an understanding of the information, and; memory and recovery. These underlie the decision-making process and define the results of consumer behaviour. | Consumer behaviour contains 4 areas, each one of which is associated with all the others. | The variables in the model do not take into account the fact that consumers are influenced by ethical questions and social responsibility or by the negative side of marketing [99], but these affect the results of consumer behaviour, just like the symbolic use of products and the diffusion of ideas, products, or services via a market. | |||||

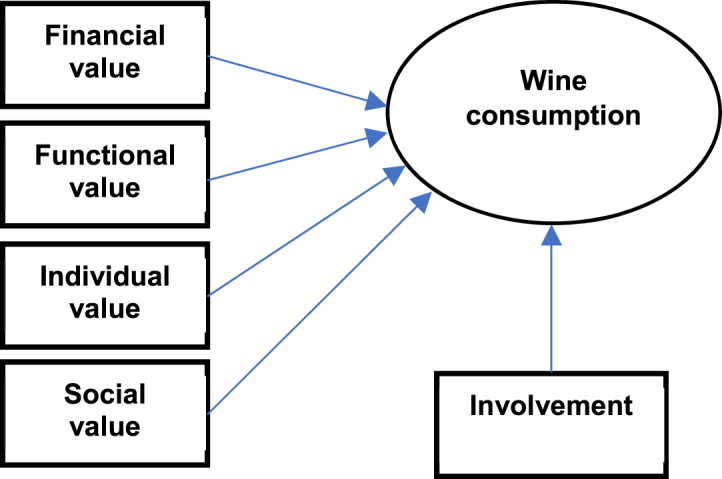

| 34 | Luxury Consumption Model [100] | 2014 | Wiedmann, Behrens, Klarmann & Hennings | Wiedmann et al. (2014) set out to verify the influence of the four consumption values on consumers' choice of wine in Germany [100]. It must also be mentioned that specifically for the product being studied, they aimed to find not only the influence of the values, but also involvement with wine as an influencing factor when it came to choosing one particular product instead of another. | The four values of the PERVAL Model are present in wine consumption, as well as involvement, as is stressed, as factors that affect selection behaviour where this product is concerned. It is observed that the values have the same characteristics as outlined by Sheth, Newman & Gross (1991a), in the consumption values theory [50], and Sweeney & Soutar (2001), in the PERVAL Model [80]. | The model was considered for only one luxury product, wine, in just one country. | |||||

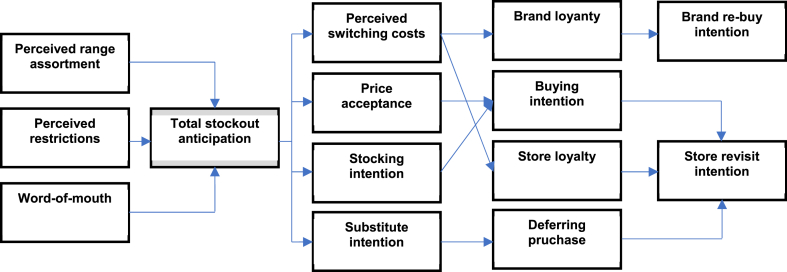

| 35 | Consumer Behavioural Model when consumers are faced with Total Depletion of a Food Product [101] | 2015 | Yangui & Hajtaïeb | This model explains consumer behaviour when they expect a food product will no longer be available, which could be of interest not only to the distributor (or the seller) but also to the manufacturer of the products concerned [102]. The findings show that expecting total depletion is influenced by word of mouth and the perceived variety or assortment of the product range. Consumers' reactions in the event of total depletion differ partially from the reactions found by previous research into simple stockouts. |

The model helps to prevent the causes of total stockouts and tries to meet consumers' needs by adapting their marketing actions to the consumers' reactions to a total food stockout [103]. | The model does not research into moderating factors, which could be the subject of future research. An attempt to replace the product is not a consequence of this anticipation, because it concentrates on one single product (milk); this affects the possibility of generalising the findings for other food product categories. | |||||

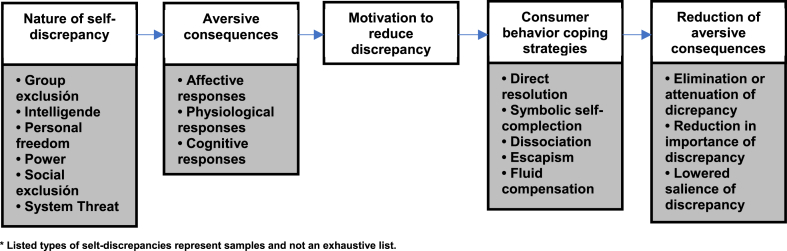

| 36 | Compensatory Consumer Behavioural Model [104] | 2017 | Mandel, Rucker, Levav & Galinsky | The compensatory consumer behavioural model [104] explains the psychological consequences of personal discrepancies in consumer behaviour, outlining 5 different strategies by means of which consumers cope with their own discrepancies: (1) direct resolution, (2) symbolic self-completion, (3) disassociation, (4) escapism and (5) fluid compensation. | The model depicts a sequential process in which once a self-discrepancy is activated, this can have affective, physiological or cognitive consequences that prompt people to deal with the discrepancy. The motive for dealing with the discrepancy may affect consumer behaviour through at least five different strategies. Finally, consumer behaviour, particularly in the form of consumption, can potentially reduce self-discrepancy [104]. | Consumer behavioural models like this one are constituted in an environment for regulating personal discrepancies or incongruencies between how one currently sees oneself and how one wishes to see oneself, i.e., the potential for compensatory consumption behaviour commences when a person perceives a discrepancy or an inconsistency between the ideal yo and the actual yo [105]. | |||||

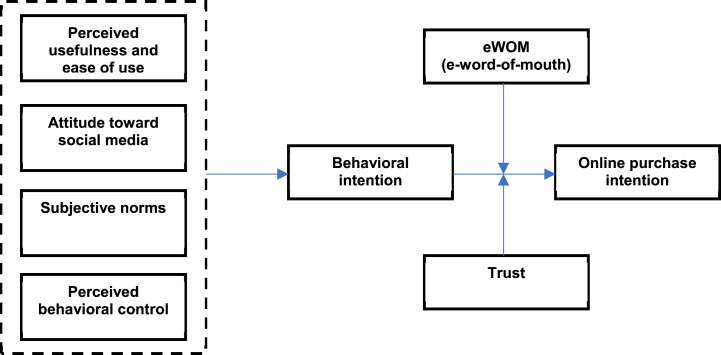

| 37 | Online Purchase Intention Model [106] | 2018 | Di Virgilio & Antonelli | Di Virgilio & Antonelli (2018) constructed a customer Theoretical Online Purchase Intention Model, based on the Planned Purchase Theory Model [53]. It establishes that there is a direct effect of customers' behaviour intention, when we buy through social network platforms; this becomes even clearer because the use of the Web is becoming part of everyday life online transactions are increasing at an exponential rate. Apart from the specific application of the relationship with the specific channel, value is added to the model considering the effect of mediation that affects purchase intention through trust in the specific platform and the availability of electronic communication played by word of mouth (eWOM) [107,108,109]. | The model illustrates the effect of mediation of the variables on online purchase intention. | The theoretical model proposed is an extension of the planned behaviour theory by Ajzen (1991) and it incorporates trust and electronic word of mouth communication as part of the customers' online purchase intention [110,111,112,10]. | |||||

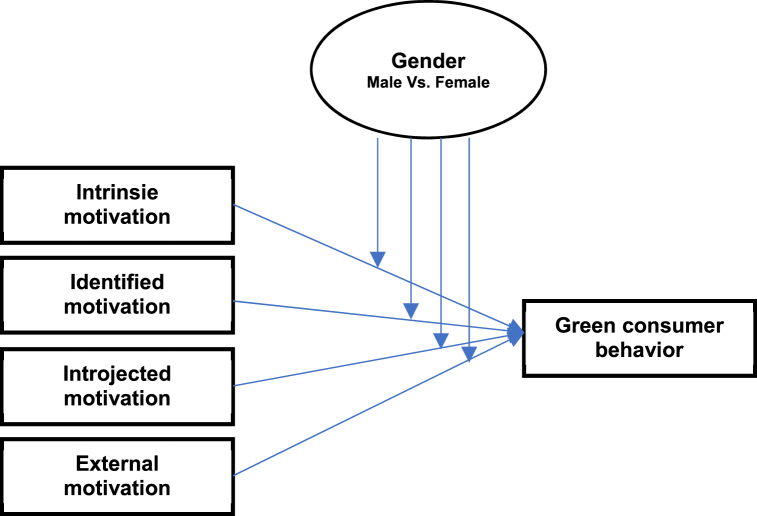

| 38 | Green Purchase Behaviour Model [113] | 2020 | Gilal, Chandani, Gilal, Gilal, Gilal, and Channa | This study researches into the effects of the regulations encouraging consumers to behave in an ecologically-friendly way using data concerning millennial Pakistani consumers. The external motivations are determinants for encouraging people to consume responsibly, where the marketing strategies fulfil a primal function. It must also be pointed out that gender is a decisive factor, where women are more inclined to purchase responsibly [113]. Eco-labelling is among the external motivations, this is a more influential factor in persons with greater purchasing power and higher education. Moreover, this is more credible and a decisive component if the person concerned has a greater global awareness about organic products or if they have had a more positive experience with similar products [114]. However, despite having a major influence, only 1 out of every 4 people know how to identify whether or not a product has an eco-label [115]. |

Collectively, this study contributes to the literature on green consumer behaviour in two ways. Firstly, we can link the motivational regulations with green consumer behaviour by examining the effects of external, introjected, identified and intrinsic motivations in green purchase behaviour and determine which motivational regulation is most promising for increasing green behaviour among consumers. Secondly, we can contribute to an examination of the gender differences regarding how the external introjected, identified and intrinsic regulations are associated with green behaviour in men and women. These findings can help green marketing companies in general, and the brand managers in particular, to design and implement marketing strategies that are separate and suitable for male and female customers. | Consumers' ecological behaviour cannot always be explained by extrinsic reasons [116,117]. | |||||

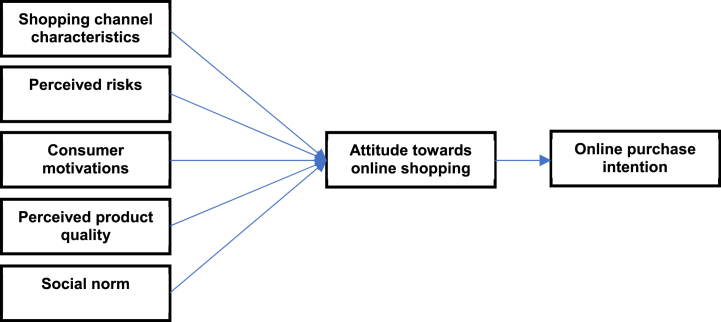

| 39 | Consumer Online Purchase Intention Model [118] | 2021 | Vasilica-Maria | The theoretical model includes indirect relations between the characteristics of the purchase channel, the perceived risks, the consumer's motivations, the perceived quality of the product and the social standard with the online purchase intention, through the online purchase attitude factor. | Vasilica-Maria (2021) decided to propose these indirect relationships, because that is how they are analysed in most studies, attitude to online purchasing even being considered as a mediating variable [119,118]. | Such variables as cultural differences and the generations to which the consumers belong could be included in the model, because these proved to have a moderating effect [120,121]. | |||||

Throughout time, there have been many authors who, as a consequence of their research into consumer behaviour, have defined different types of purchasing. These purchasing types have been incorporated into the different theoretical consumer behavioural models, with a view to explaining in the social and economic areas, not only consumers' individual behaviour but also consumers’ collective behaviour.

Moreover, the theoretical conception of behavioural models has evolved greatly over the past 50 years. Ehrenberg, Goodhart & Barwise (1990) refer to this evolution when they mention the different approaches given to the three methodological approaches -aprioristic, empirical and eclectic-in the drawing up of consumer behavioural models in recent years [122].

Making use of the theoretical concepts of consumer economy and psychology, the aprioristic approach understands consumer behaviour as one of the facets of human conduct, and its attitude is governed only and exclusively by its positioning in relation to social phenomena. Even with this limited view, the aprioristic approach was marked by work in the motivational area and in research into attitudes.

In contrast to the aprioristic approach, which seeks to explain consumption behaviour in preconceived theoretical structures, the empirical approach postulates laws from the observation of behavioural patterns, mainly on the basis of panel and survey data.

The eclectic approach, combining the positive aspects of the two earlier ones by bringing together the theoretical concepts of the aprioristic approach and the specific findings of the market studies arising from the empirical approach, emerged at the end of the 1960s.

These three approaches can be summarised in the following way [123]:

Aprioristic.- This is an approach in which theories and concepts pre-established in other sciences are utilised, its strength lying in the use of a major theoretical base. However, the studies developed in contexts not included in the consumption scenario, often use experiments with students in laboratories.

Empirical.- This is an approach in which data are used obtained from field tests and from the panels, with theoretical formulations designed from the observation of behavioural patterns, highlighting the utilisation of research applied to actual scenarios, which enables the user to measure consumption phenomena. However, its weakness lies in the lack of theories coming from social sciences and the relative absence of explanatory power.

Eclectic.- This is an approach in which makes use of the theoretical precepts of the aprioristic approach and the studies and experiments of the empirical approach. Therefore, this approach's scope is its biggest strongpoint, given that the researcher is able to trace guidelines for the marketing actions and for basic research. Yet, as it is more complex, the drawback with this type of approach stems from the fact that there are too many variables and interrelations, and so it requires the support of a greater amount of studies from other spheres of knowledge.

In the same way as there are different approaches, there are also different kinds of defined models. The economic factor has been taken as the reference for this analysis, considering two types of models collected by Manzuoli [124].

1.1. The microeconomic model

A model proposed at the beginning of the 19th Century, which stresses the pattern of goods and prices in the global economy as axes that are central to it. This model is based on suppositions with regard to a “standard consumer” about whom the theory concerned is postulated. It revolves around the act of purchasing, i.e., trying to predict the product to be chosen by the consumer and the amount concerned. This model takes tastes and preferences for granted, and does not take into account the origin of the necessities and their appraisal. The characteristics of this model where consumers are concerned are:

-

-

The consumer's requirements and wishes are unlimited. Therefore, it is not possible to meet them completely.

-

-

The budget allocated will be utilised to maximise their needs.

-

-

The consumers' preferences are dependent and constant.

-

-

The consumers are perfectly aware of the degree of satisfaction that a product will give them.

-

-

The marginal use or satisfaction generated by every additional unit will be less than the satisfaction generated by the previous ones.

-

-

Consumers recognise the price of an item of goods as the only measure of sacrifice that is required to obtain it. Therefore, it does not fulfil any other function in the purchasing decision.

-

-

Consumers are perfectly rational in the sense that, in view of their subjective preferences, they will always act in a deliberate way to maximise their satisfaction.

Given these suppositions, economists argue that totally rational consumers who make decisions based on logical and conscious calculations, will invariably purchase the goods that offer them the best cost-benefit. Despite its limitations, certain aspects of the model have been modernised and are still relevant, with their well-known influence on thought in the Purchase-Decision Process.

1.2. The macroeconomic model

The macroeconomy has developed a model that focuses on the aggregated flows of the economy. The monetary value of the resources, their trend and how they evolve. This model groups together the incomes of the persons into consumption and saving. It analyses the hypothesis of “relative income” which explains that the proportion of income that a family gives over to consumption only changes when a change in income places that family in another social bracket. This will not happen if all the income levels are raised at the same time. Another hypothesis is the so-called “permanent income”, where an analysis is given for the reasons why some individuals change their consumption habits slowly even when their incomes change suddenly, establishing that people consider sudden income changes are temporary and, thus, expect them to have little effect on consumption activity. Although its contributions are interesting, one of the major drawbacks to this model is that it stresses the economic variables and ignores the effects of psychological factors.

These first models were based upon economic systems in order to understand the allocation of limited resources in the face of unlimited needs, so they now recognised the importance of requirement as an initial factor for a model that understands the consumer.

When reviewing the literature, it is also possible to find integrated models that describe consumer behaviour. Some authors point to three consumer behavioural models as being the most complete and exhaustive: the models devised by Howard-Sheth, Nicosia and Engel, Blackwell & Miniard [125,126]. Along the same lines, it is considered that the Howard Model has great predicting ability [127].

Other integral models were those by Markin, Kerby & Holbrook and the experimental consumer model by Hirschman. They are all very similar to the models devised by Howard-Sheth & Engel, Blackwell & Miniard [126].

Rao & Vilcassim (1985) prepare a mathematical model without graphical representation [21]. The model's most important premise argues that an individual's choice is what maximises its usefulness subject to certain restrictions (such as resources). It amounts to a certain progress because it is a match to the problem, but it does not provide any new concepts and neither does it present specific results for its actions [125].

Although the information processing model by Bettman (1979) is complete, according to its author, it is not an integrated model [13].

As a consequence, although all the aforementioned models have contributed to an understanding of consumer behaviour, this work will concentrate on economic models that have been tested statistically on high-impact research work, with proposals that takes us from 1935 up to 2021.

The main theories and/or models that have brought about evolution in time and that best represent the interaction between variables that can predict economic behaviour, are explained below. They are split into periods covering more than 90 years; these models are classified on the basis of their economic area and approach. The main findings of each one are highlighted, together with an analysis of their pros and cons.

2. Eras of research and development of models

2.1. UP to the 1950s

Since the 1930s, theories have been considered, which could well be regarded as the first models [2], such as the Psychological Theory of the Underpinnings of Economic Behaviour (Fig. 1), considered by Tarde (1935). Later on, in the 1950s, marketing experts were postulating theories to explain, comprehend and predict consumer behaviour [128], trying to understand from its motivations [129] the psychological consequences of the unconfirmed expectations [130]. Katona (1951) also belonged to that period [3] with his Economic Behaviour Psychological Analysis Model (Fig. 2). Every year, the findings yielded by new studies, often divergent, generate new research trends into the subject.

Fig. 1.

Model of the theory of the causation of economic behaviors [2], by Gabriel Tarde (1935).

Fig. 2.

Model of psychological analysis of economic behavior [3], by George Katona (1951).

2.2. The 1960s

The early 1960s were marked by the development of hierarchical models concerning the effects of advertising on purchasers, such as those proposed in the works of Colley (1961) & Lavidge & Steiner (1961), not to mention the memorable proposal of the 4Ps model (product; price; promotion and place) [131,132] put forward by Professor Jerome McCarthy [133]. Between 1955 and 1975, there was a major increase of interest in the concept of involvement [134,135], as well as research into cognition based on the crystallisation of attitude processes [136] and the beginning of formulations of integrated consumer behaviour models by Andreasen (1965), Nicosia (1966) and Howard & Sheth (1969), which made an outstanding contribution to consumer study [4,34,6,5], although with some of these models (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 6) empirical validation is difficult [7]. Later on, Engel, Kollat & Blackwell (1968) suggested one of the most emblematic portrayals of consumer behaviour (Fig. 5), with a trend towards understanding the decision-making process in a way that was too schematic [137,8]. After that, the model was developed by Engel, Blackwell & Miniard (1986) and the most recent modification to be found in the literature is the one perfected by Engel, Kollat & Miniard (1990) in the Consumer Behavioural and Decision-Making Model [138,139]. At the end of that decade, Howard & Sheth (1969), developed the Purchaser Behavioural Model to analyse the selection process for the product or the brand, which has been extensively studied and used by different researchers [11,[140], [141], [142],142,34,143,35,144,145]. However, it has been tested empirically and its lack of forecasting capacity has been brought to light [11].

Fig. 3.

Model of consumer behavior [4], by Andreasen (1965).

Fig. 4.

Model of consumer behavior model [5], by Nicosia (1966).

Fig. 6.

Model of consumer behavior [9], by Howard and Sheth (1969).

Fig. 5.

Model of consumer behavior and decision making [8], by Engel, Kollat and Blackwell (1968).

2.3. The 1970s

In the 1970s, Albou (1978) considered the Ternary and Graphical Previsional Model (Fig. 7), classified as qualitative and which enables the user to understand how the economic agents react in the presence of stimuli coming not only from the (psychological aspect) but also from the context [12]. Subsequently, Bettman (1979) made himself known for specifically tackling the Processing of Information in his Model of the same name (Fig. 8), providing a simplified description of consumption behaviour, considering this to be a process of decisions taken by means of simple and individual strategies [13], which yields an original and complete structure of the consumption decision-making process, pinpointing most of the variables that affect it [9]. With all the above, the Bettman Model has certain disadvantages, mainly the difficulties involved in validating the model, which are caused by its complexity and its limited operability [14].

Fig. 7.

Ternary and forecast graph model [12], by Paul Albou (1978).

Fig. 8.

Model of information processing [13], by Bettman (1979).

2.4. The 1980s

In the 1980s, when great emphasis was put on important models that defined the future, Ajzen & Fishbein (1980) proposed the Theory of Reasoned Action Model (Fig. 9), which made a major contribution to the study of human behaviour in general, and consumer behaviour in particular, so its contributions are important in these fields of study [15]. To be specific, it enables the user to consider certain factors that hitherto had only been considered in an isolated way, and it makes it easier to understand behavioural determinants. Yet it does have some limitations, including its inability to forecast, especially with regard to certain kinds of behaviour that occur habitually where the individual is unaware of the decision process taking place [16]. Inspired by the ideas of Dulany (1968), the theory of reasoned action was originally put forward by Fishbein (1967), and they prompted a series of research works concerning the processing of information [146,147,148], taking into account the multidimensional nature of attitude [149,150], apart from the cognitive response models [151,152,153]. It was subsequently improved by Ajzen & Fishbein (1980), to explain how beliefs, attitudes and intentions determine consumer behaviour [15].

Fig. 9.

Model of the theory of reasoned action [15], by Ajzen and Fishbein (1980).

Van Raaij (1981) proposed the Economic Behaviour Integration Model (Fig. 10) in which he combines the economic variables with the psychological variables [17], insisting on considering the feedback between economic behaviour and the context conditions [18], making it patent that this model features an aspect of dynamism that makes it extremely interesting, allowing for multiple combinations, while at the same time being able to serve as the basis for more specific models that can be integrated into it. In this way, it made significant progress from the model by Katona (1951) by incorporating the interaction with new elements [3]. The following year, Holbrook & Hirschman (1982) suggested the market research was concentrating too much on the static nature of attitude to the detriment of its informative determinants, and promoted their Experimental Consumer Model (Fig. 11), in whose analysis the findings suggest implications for marketing decisions, public policies and the future course of research into attitudes in marketing [20,19].

Fig. 10.

Integration model on economic behavior [17], by Fred van Raaij (1981).

Fig. 11.

Experimental model of the consumer [19], by Holbrook and Hirschman (1982).

Midway through this decade, one main aim of consumer research was to predict the choices an individual consumer or a group of consumers when a change affects the conditions that bear an influence on selection. Rao & Vilcassim (1985) present a unified approach for modelling dynamic discrete choice processes, in a model of the same name (Fig. 12) that subsumes the two main approaches adopted in the literature: the econometric approach of qualitative choice and stochastic choice models [21]. At the same time, Gatignon & Robertson (1985) developed a global model for the processes of innovation diffusion (Fig. 13), under the assumption that the first people to adopt a new product are hoping to obtain some kind of benefit or improvement [22], which is associated with other works according to which the most innovative consumers are generally well informed [154,27] and make greater distinctions with regard to the information they need, considering that the marketing actions, which are associated with segmentation, positioning and decisions with respect to price, product, distribution and communication, have an effect on how quickly adoption takes place [155].

Fig. 12.

Model of dynamic discrete choice [21], by Rao and Vilcassim (1985).

Fig. 13.

Model of innovation adoption [22], by Gatignon and Robertson (1985).

At the end of the decade, the model by Howard & Sheth (1969) was reviewed and completed by Howard (1989) himself, with a view to improving its comprehension and simplicity [9,34]. Paying attention to the way the product evolved where consumer behaviour was concerned, the model is developed on seven elements that are involved in the consumption process and its relationships: information, brand recognition, attitude, trust, intention, purchase and purchase satisfaction. According to John Howard, his Model, referred to as the Consumer Decision Model (Fig. 14) consist of only six components and the relationships between them, which precede the satisfaction element, which would be a final variable in the model [9]. And, at the same time, Davis, Bagozzi & Warshaw (1989) considered the final version of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Fig. 15), which was developed by Davis (1989) using the theory of reasoned action [15,37,36] to explain the behaviour of the individual when adopting new technologies through the impact of external factors on an individual's attitudes and intentions [36], a reference model being considered in the study of the acceptance of computerised applications, as well as adopting and using the Web [156,38]. Thus, an individual's attitude to technology ends up by affecting his/her actual use [39]. The TAM model stands out because of the contribution it makes to behaviour when using new technologies and, specifically, when considering how external factors influence beliefs attitudes and intentions [36]. It has been supported by many research works [40,39,41,42], including the following: Adams et al. (1992), Venkatesh & Davis (1994), Taylor & Todd (1995) and Koufaris (2002). Be that as it may, it does have certain restrictions arising from the limited number of variables incorporated [41] as determinants regarding attitude towards use (Taylor & Todd, 1995) (see Fig. 16).

Fig. 14.

Consumer decision model (CDM) [9], by Howard (1989).

Fig. 15.

Model of technology acceptance [36], by Davis, Bagozzi and Warshaw (1989).

Fig. 16.

Brand Choice Model [43], by Dong Hwan Lee (1990).

Moreover, around 1990, research was aimed at trying to perfect integrated behavioural models, in order to be able to account for the process of forming attitudes and introducing implication as a moderating variable [157,158,159,160,161]. More recently, studies have found non-cognitive alternatives to be a channel for influencing the processing of information devised to persuade when it comes to adopting certain attitudes, such as humour [162,163], conditioning [164,165,166], exposure [167,168], preconscious processing [169] and attitude towards advertising [170,167].

Later, as described by Lopes, E.L. & Silva, D. (2011), research reflected an interest in understanding information processing focusing on [123]:

2.5. The 1990s

At the beginning of this decade [46], Bagozzi & Warshaw (1990) promoted the Theory of Trying Model (Fig. 17). Just like the planned behaviour theory [57], it is an extension of the theory of reasoned action [15], although it was especially developed to explain behaviour patterns where the individual attempts to reach a specific goal when there is a degree of uncertainty regarding its attainment. When being devised, it was considered that the reasoned action model [15] did not enable its users to suitably explain those cases where an individual's behaviour is interrupted by barriers that prevent or hinder him/her from achieving the objectives that he/she was endeavouring to attain [16].

Fig. 17.

Model of the theorý of trying [46], by Bagozzi and Warshaw (1990).

Immediately after, Lea, Tarpy & Webley, (1991) promoted the Dual Causation Paradigm Model (Fig. 18), which is not a model in itself. Nevertheless, it represents the organising of deeds, suppositions, explanations and research into the variety of economic psychology theories, concentrating on the need for a comprehensive theory for economic behaviour and on the questions that this cannot yet answer [47].

Fig. 18.

Model of dual causation paradigm [47], by Lea, Tarpy and Webley (1991).

Sheth, Newman & Gross (1991a), in their Model of Consumption Values (Fig. 19) state that consumer choice is based upon a multiple consumption values function, more specifically, it is based upon five value dimensions: functional, social, emotional, epistemic and conditional [50]. Supplemented by Lin & Huang (2012), apart from the proposition that consumer choice is a function of multiple consumption values, there are two more proposals considered to be essential when tackling the question of consumption values [49], Sheth, Newman & Gross (1991a): The consumption values make different contributions in any choice situation [50] [175] [49], and the consumption values are independent [175] [49], given that the consumers’ choice may either be determined by a specific value or jointly two or more values together.

Fig. 19.

Model of consumption value [48], by Sheth, Newman and Gross (1991).

At the same time, the Planned Behaviour Theory Model (Fig. 20) was devised by Ajzen (1985) with a view to overcoming the limitations of the reasoned action theory [57,15] and to improving the ability to explain of behaviours where the individual does not have complete control over implementation. Subsequently, Mason (1992) developed a conceptual behaviour model for the market, which he called the Demand for Status Goods Model (Fig. 21), where he examined the processes of searching, assessment and selection involved in purchasing and consuming status goods, in which status-seeking behaviour is greater in societies where the emphasis is placed on social status and in doing so there is a greater trend towards consuming to exhibit [69].

Fig. 20.

Model of the theory of planned behavior [53], by Ajzen (1991).

Fig. 21.

Model of the demand for status assets [69], by Roger mason (1992).

Later on, Schiffman & Kanuk (1993) promoted the Basic Consumer Decision-Making Model (Fig. 22), which does not aim to take in complex decisions, but rather to simplify the approach to decision-making [70]. However, it is also so extensive, that it can cover not only simple decisions but also complex ones [70]. Subsequently, to understand consumer behaviour in any global market, Raju (1995) proposed the A-B-C-D Paradigm Model (Access-Buying Behaviour-Consumption Characteristics-Disposal) (Fig. 23). Access-Buying Behaviour-Consumption Characteristics-Disposal, the four aspects envisage in the initials refer to the four sequential stages used to represent the purchasing and consumption processes in any culture.

Fig. 22.

Basic model of consumer decision making [70], by Leon Schiffman & Leslie Kanuk (1993).

Fig. 23.

Model of a-B-C-d paradigm [71], by Raju (1995).

Midway through the 1990s, Taylor & Todd (1995) proposed the Decomposed Theory of Planned Behaviour (Fig. 24), which tries to explain the adoption of new technologies on the basis of the elements [41] already considered by the theory of planned behaviour [55]: attitude, subjective standard and perceived control. Later on, Quintanilla, Arocas & Contrí (1998) considered a Structural Cognitive-Affective-Purchase Model (CAC) (Fig. 25) in which an attempt is made to categorise different experiential states on the basis of their affective and cognitive activation, considering that not only high cognitive activation but also high cognitive activation could be states where the consumer is highly involved [73]. Later on, Assael (1998) proposed the Consumer Purchase Decision Model (Fig. 26), which became the iconic blueprint utilised to simply explain the consumers’ decision-making process [74]. Finally, Páramo (1999) considered the relationship in national culture, the congruence between self-concept and image, and consumer behaviour, through his Symbolic Culture Model (Fig. 27). His main approach concerns the impact that domestic culture (the approach of Hofstede, 1980) exerts upon consumer behaviour via the concept of self-congruence [76,75]. National culture and brand image will be regarded as separate and independent variables.

Fig. 24.

Model of the decomposed theory of planned behavior [41], by Taylor and Todd (1995).

Fig. 25.

Affective-cognitive purchase model (CAC) [73], by Quintanilla, Luna and Berenguer (1998).

Fig. 26.

Model of consumer purchase decision [74], by Assael (1998).

Fig. 27.

Symbolic-cultural model of consumer behavior [75], by Páramo (1999).

2.6. 2000–2009

Sweeney & Soutar (2001) developed the Perceived Value Model - PERVAL (Fig. 28) in order to account for the values that affect decision-making in the choices of certain consumers [80], which has had a considerable effect on the measurement of the value as perceived by the consumer, given that it enables the user to empirically compare the multidimensional nature of the value construct [81]. Subsequently, Blackwell, Miniard & Engel, J. (2002) stressed that what is bought and is used is finally a result of some decision, pointing out that if this decision is to be the most reliable and appropriate [83], instead of the purchaser merely being carried away by a set of indicators, it is better for the decision to be based upon something more complete and entire such as a map, in his Consumer Decision Process Model (Fig. 29), which depicts schematically the activities that occur when decisions are taken, showing how the different internal and external forces interact and how they affect the way in which consumers think, assess and act. At the same time, Xueming Luo (2002) proposed the Uses and Gratifications Theory model in the context of e-consumer behaviour (Fig. 30), which predicts the use of the Web and satisfaction as consumers, based upon their attitude to the Web itself, but conceived from three dimensions that include entertainment, information and irritation [84].

Fig. 28.

Model of perceived value – PERVAL [80], by Sweeney and Soutar (2001).

Fig. 29.

Cdp model - consumer decision process [83], by Blackwell, Miniard and Engel, J. (2002).

Fig. 30.

Model of the theory of uses and gratifications and behavior of the electronic consumer [84], by Xueming Luo (2002).

Midway through the noughties, Rodríguez-Vargas (2005) presented the Consumer Psycho-economic Model (Fig. 31), which stems from the theories inherent to the Economic Behaviour Integration Model [92,17], which aims to link the contributions from the study undertaken [176] by Denegri, Palavecinos & Ripoll (1998), especially the tool utilised in it, with the theoretical model [17] by Fred Van Raaij (1981). However, it is all the approaches considered [96] by Ortega & Rodríguez-Vargas (2005), that allow for its subsequent validation and applicability to any economic situation, in view of the demonstrated validity of its scales [[93], [94], [95]] and its association with a sound theory. Rodríguez-Vargas (2006) structure the Consumer Psycho-economic model not only from a holistic and comprehensive perspective, but, above all, from an objective and measurable perspective, in which the following variables are interrelated: Nuclear Family Income, Consumption Habits, Subjective Well-Being with the Consumption Style, State of Indebtedness, Perceived Financial Situation and Attitude to Indebtedness [97].

Fig. 31.

Psychoeconomic model of the consumer [92], by Rodríguez-Vargas (2005).

Kotler & Keller (2006) found that marketing stimuli consist of the following variables: product, price, distribution and communication [98]. Furthermore, other stimuli involved in the process are the so-called variables external to the purchaser: economic, technological, political and cultural. That is how they present the Purchase Behaviour Model (Fig. 32).

Fig. 32.

Purchasing Behavior Model [98], by Kotler and Keller (2006).

2.7. 2010 to 2021

Hoyer & McInnis (2010) suggest that consumer behaviour contains four areas, each one of which is associated with all the others [99]. Their Consumer Purchase Behavioural Model focuses on (Fig. 33) what they call the psychological centre, where they consider that when taking their decisions, consumers must have the following: motivation, skill and opportunity; exposure, attention and perception; knowledge and an understanding of the information, and; la memory and recovery. The aforementioned underlie the decision-making process and define the results of consumer behaviour.

Fig. 33.

Model of consumer buying behavior [99], by Hoyer and McInnis (2010).

Wiedmann et al. (2014) aimed to verify the effects of the four consumption values on the consumers’ choice of wine in Germany [100], using their Luxury Consumption Model (Fig. 34), where those values have the same characteristics as outlined [50] by Sheth, Newman & Gross (1991a), in the theory of consumption values, and Sweeney & Soutar (2001), in the PERVAL model [80]. It must also be pointed out that specifically for the product studied, the idea is to identify not only the effect of those values, but also involvement with wine as an influencing factor when it comes to choosing one particular product instead of another.

Fig. 34.

Model for luxury consumption [100], by Wiedmann (2014).

Another research study, carried out by Yangui & Hajtaïeb (2015), developed the Consumer Behavioural Model when consumers were faced with a Total Depletion of a Food Product, (Fig. 35), which explains consumer behaviour by anticipating a total depletion of a food product [101], which could be of interest not only to the distributor (or the seller) but also to the product manufacturer [102], because it helps to prevent the causes of total depletion and endeavours to meet the customers' requirements by adapting their marketing activities to the consumers’ reactions to a total food depletion [103].

Fig. 35.

Model of consumer behavior in the face of a total shortage of a food product [101], by Yangui and Hajtaïeb (2015).

Mandel, Rucker, Levav & Galinsky (2017), proposed the Compensatory Consumer Behaviour Model (Fig. 36), which explains the psychological consequences of personal discrepancies in consumer behaviour, setting out five different strategies through which consumers cope with self-discrepancies: symbolic self-completion, disassociation, escapism and fluid compensation [104].

Fig. 36.

Compensatory model of consumer behavior [104], by Mandel, Rucker, Levav and Galinsky (2017).

Later on, Di Virgilio & Antonelli (2018) constructed the Online Purchase Intention Theoretical Model (Fig. 37), from the Planned Purchase Theory Model [53]. It establishes that there is a direct effect of customer intention behaviour on their purchase intention [106]. When we buy through social network platforms, this becomes even more obvious, because using the Web is becoming part of everyday life and online transactions are increasing at an exponential rate.

Fig. 37.

Model of online purchase intention [106], by Di Virgilio and Antonelli (2018).

Academic research into consumer behaviour has found that motivation is a crucial determinant that promotes green purchase behaviour [177,178,179]. As such, all the market academics and professionals are looking for new ways to support the motivation of their customers [180,181,182]. As a result, the link between motivation and green purchase behaviour has been the subject of considerable attention in recent years [183,184,185]. Although an exact understanding of what prompts consumers to purchase ecological products is still evolving [186,187,188], most of the studies describe motivation by extrinsic means, i.e., the perception of control over behaviour, subjective standards and attitude, and then examine the effect on green purchase behaviour [189,190]. However, Gilal, Chandani, Gilal, Gilal, Gilal, & Channa (2020) argue that ecological behaviour of consumers [113] cannot always be well explained through extrinsic motives [116,117]. In accordance with this theoretical notion, Gilal, Chandani, Gilal, Gilal, Gilal & Channa (2020) consider that the diverse effects of the types of motivation provide a more accurate way of researching into the link between the types of customer motivation and their ecological behaviour [113]. Apart from examining the effects of the types of motivation on consumers' ecological behaviour, their Green Consumer Behaviour Model (Fig. 38) also attempts to consider the moderation of the gender. From the professionals’ perspective, studying gender differences is of paramount importance, because such differences are held to be important when it comes to market segmentation [191,192] and they are generally identified as key moderators in consumer research [193,177,194,195,196,197]. Therefore, in current scenarios, it is very important to find out whether the motivational regulations in green consumer behaviour can be differentiated by gender group.

Fig. 38.

Model of green consumer behavior [113], by Gilal, Chandani, Gilal, Gilal, Gilal, and Channa (2020). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Finally, after providing a rundown of dozens of models over almost 90 years, we find the approach made by Vasilica-Maria (2021), who consider the Consumer Online Purchase Intention Model (Fig. 39), which contains indirect relationships between the characteristics of the purchase channel, the perceived risks, consumer motivation, the perceived quality of the product and the social standard with online purchase intention through attitude to online purchase [118].

Fig. 39.