Abstract

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are responsible for 90% of all business and 50% of employment globally, mostly female jobs. Therefore, measuring SMEs’ performance under the digital transformation (DT) through methods that encompass sustainability represents an essential tool for reducing poverty and gender inequality (United Nations Sustainable Development Goals). We aimed to describe and analyze the state-of-art performance evaluations of digital transformation in SMEs, mainly focusing on performance measurement. Also, we aimed to determine whether the tools encompass the three pillars of sustainability (environmental, social, and economic). Through a systematic literature review (SLR), a search on Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus resulted in the acceptance of 74 peer-reviewed papers published until December 2021. Additionally, a bibliometrics investigation was executed. Although there was no time restriction, the oldest paper was published in 2016, indicating that DT is a new research topic with increasing interest. Italy, China, and Finland are the countries that have the most published on the theme. Based on the results, a conceptual framework is proposed. Also, two future research directions are presented and discussed, one for theoretical and another for practical research. Among the theoretical development, it is essential to work on a widely accepted SME definition. Among the practical research, nine directions are identified–e.g., applying big data, sectorial and regional prioritization, cross-temporal investigations etc. Researchers can follow the presented avenues and roads to guide their researchers toward the most relevant topics with the most urgent necessity of investigation.

Keywords: Digitalization, Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), Industry 4.0, Triple bottom line (TBL) of sustainability, Sustainable development goals (SDG)

Highlights

-

•

Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) are affected by Digital Transformation (DT)

-

•

The DT in SMEs plays an essential role in the Triple Bottom Line (TBL)

-

•

Performance evaluation approaches for DT in SMEs considering TBL are reviewed

-

•

Most investigations neglect at least one of the three aspects of sustainability

-

•

Research avenues and roads for further investigations are presented and discussed

1. Introduction

Digital Transformation (DT) blurs the boundaries across organizations and industries, challenging the enterprises' competitiveness [1,2]. In this context, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) have inherent characteristics that differentiate them from larger companies [3,4]. For example, more flexibility and agility for adapting to new circumstances [5], limited resources, and specialization capabilities. These characteristics reflect in the DT process [3,4]. Although it is of the utmost importance to develop tools for systematically measuring SMEs’ performance in multiple aspects of the DT, guaranteeing their survival and competitiveness [4], this topic keeps under-researched in the extant literature [4,6].

Besides economic importance, the DT of SMEs also directly involves the social and environmental pillars of sustainability [7]. On the one hand, DT catalyzed the loss of routine and activity-based job positions and increased material consumption, resulting in multiple non-environmentally friendly consequences [8]. On the other hand, SMEs account for 90% of all business and 50% of employment globally [9]. And the job losses due to DT are expected to be more severe in developing countries than in developed ones once activity-based positions represent a larger share of employment in the former ones [8]. However, it was observed in Germany, China, India, and Brazil that 4000 SMEs which earlier adopted digital technologies created jobs almost twice faster as other SMEs [10]. Also, SMEs that trade internationally are more confident in the current and future business environment and have positive prospects of job creation [11]. Finally, based on the observation of 438 Italian SMEs, Denicolai et al. [7] found that DT positively influences the international performance of SMEs. However, although DT and environmental sustainability are positively related, they ended up becoming two competing growth paths.

Given this dilemma, the current paper aims to describe and analyze the state-of-art for evaluating DT in SMEs, primarily focusing on performance measurement. Also, it seeks to determine whether the tools used encompass the three pillars of sustainability (environmental, social, and economic), also known as the sustainability Triple Bottom Line (TBL) [12]. Besides, it aims to identify the institutions and journals that are leading the publications on the theme. In other words, the main research question (RQ) is: “What is the state-of-art of Digital Transformation on the performance of SMEs?“. Followed by the secondary RQs: “Are there papers proposing tools, dimensions, and variables for measuring the impacts of Digital Transformation on the performance of SMEs?” and “If so, do these tools, dimensions, and variables also encompass the three pillars of sustainability (environmental, social, and economic)?“.

Toward this end, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) by analyzing 74 papers in peer-reviewed journals until December 2021. We extracted papers from the databases Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). Here we deliver a preliminary review of the state-of-art theme. The analysis reveals that this is a new research theme with increasing interest in recent years (especially since the COVID-19 pandemic). Though most papers still do not jointly consider environmental and social aspects of sustainability for measuring performance. Also, the lack of standardization about the definition of SME and its defining characteristics hardens data collection and the comparisons between different paper results. Although the implicit difficulties, most papers applied a quantitative approach in a real context (predominantly investigating SMEs in Europe and Asia). Though only 42% directly proposed a quantitative tool for measuring DT performance in SMEs.

Finally, our review proposed a conceptual framework for the theme and pointed out the main future research directions, one theoretical and another practical. Regarding the construction of the body of knowledge, future research is recommended to propose a definition of SME that encompass the no-homogeneous characteristics of SMEs across different industries. Regarding future practical investigations, nine directions are pointed out. Researchers can consider these recommendations for focusing efforts on relevant knowledge frontiers.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a theoretical background about digital transformation, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), and sustainability. Section 3 offers the research design used to obtain and analyze the results, which are presented in Section 4. Finally, based on this investigation's limitations, Section 5 brings the conclusions summarizing the future research directions.

2. Theoretical constructs

This topic mentions numbered questions. Readers can find all mentioned questions in the “Data Extraction Form Fields” (Appendix).

2.1. Digital transformation (DT)

As a point of start, it is crucial to distinguish Digital Transformation (DT) from similar concepts, i.e., Digitization, Digitalization, and Industry 4.0.

Without proposing a formal definition of Industry 4.0, Culot et al. [13] investigated 100 definitions of the term and related concepts, breaking them down into each definition's underlying technological and non-technological definitional elements. According to the authors, although sometimes mentioned as a synonym of Industry 4.0, the concept of DT stresses the implications for strategy and business model innovation, underlines the emerging technologies on the business model, and, in turn, the rise of cross-industry ecosystems. Also, although the term “Industry 4.0” can be applied to other sectors, it is mostly associated with the DT process in the manufacturing sector [13] and supply chain [14].

According to Verhoef et al. [15], digitization is converting analog information into digital. Digitization does not add value to activities. It normally refers to the act of digitalizing internal and external processes. On the other hand, despite conceptual differences, the terms “digitalization” and “digital transformation” are frequently used interchangeably and refer to a broad concept affecting an ecosystem [16].

Digitalization refers to a process where enterprises apply digital technologies in a new way to optimize existing business processes. This enables more efficient coordination among processes. It may add value once it enhances users’ experience [15]. Digitalization is a process to enhance competitive advantages, for example, by offering new services through virtual channels or enabling new systems for operations management [17].

Finally, DT is the most pervasive phase of an enterprise's process toward digitalization. It goes beyond digitalization and changes the whole enterprise leading to the development of a new business model [15]. Reis et al. [16] defined DT as the use of new digital technologies that influences all aspects of customers' lives and enables major business improvements.

Aiming to establish a unified definition of digital transformation, Gong and Ribiere [18] systematically reviewed and analyzed 134 well-received definitions of digital transformation. Subsequently, after identifying primitives, core, and peripherical attributes, the authors proposed a definition and validated it with specialists. They incorporated the specialists’ feedback and ended up with the following definition: “Digital transformation is a fundamental change process, enabled by the innovative use of digital technologies accompanied by the strategic leverage of key resources and capabilities, aiming to radically improve an entity and redefine its value proposition for its stakeholders.“. In this context, an entity may be an organization, a business network, an industry, or a society.

Therefore, here we mainly searched for papers that used the term “digital transformation”. However, once this term may be misused interchangeably with similar concepts, for the initial search, we accepted papers that used the terms “Industry 4.0”, “digital transition”, “digital innovation”, or “digitalization” once the term “digital transformation” is mentioned at least once and they were focused on SMEs.

Considering our main goal, we classified the accepted papers among those that directly proposed a quantitative method for measuring digital transformation performance (Question 3) and those that did not. Also, we classified whether the papers performed an empirical investigation (Question 4) and the nature of their data and method (Questions 9 to 11).

2.2. Definitions of SME

Here we understand the term “small and medium enterprises” (SMEs) as a synonym for “small and medium-sized enterprises”. However, there is no globally standardized definition of the term. The most common classifications of an enterprise as an SME are based on a financial measure and/or the number of employees. Besides, even the same country may have different definitions of SME, depending on the sectorial industry. For example, in the USA, a “small enterprise” in the “Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting” sector is based on annual income for all subsectors except for the logging subsector. In the logging subsector, a “small enterprise” is an enterprise with less than 500 employees. For the “small enterprises” defined by the annual income in this sector, the limit value varies from 1 million to 30 million dollars, depending on their subsectors [19]. This definition difference may imply different results interpretations, depending on the sectorial industry.

Another example is Brazil and Chile, South American countries. In Brazil, SMEs must have from 20 to 249 permanent employees. However, there is also another definition of SMEs based on the annual income criterion according to the Statute of Micro and Small Enterprises in Brazil. In this case, SMEs have an annual income from 360,000 BRL (Brazilian currency) up to 3,600,000 BRL, except for SMEs in the banking sector that follow a different definition [20]. It is important to highlight that there is no inflation correction in this definition. In Chile, an SME is defined as “an enterprise with permanent 10 to 199 workers” or “an enterprise whose annual income from sales and services and other business activities is greater than 2400 UF (Chilean currency, automatically inflation corrected), but less than 100,000 UF in the last calendar year” [21]. Also, some countries consider the number of temporary employees in their definition of SME, such as Japan [22].

In summary, the definitions based on the number of employees are usually not the same in terms of the number and the kind of labor relations to consider. Besides, the definition based on financial terms is usually determined by local law, established in terms of a local currency value at the date of the law approval, without inflationary considerations. Hence, to be comparable definitions from different countries, it may be necessary to correct inflation, convert currency, and make the definitions represent similar economic importance to each analyzed economy.

Besides, the lack of a standardized definition is critical for investigating DT. Although some authors may argue that a definition based on the number of employees is enough for comparing SMEs’ performance [[23], [24], [25]], highly digitalized SMEs may have significatively fewer employees and higher economic results than non-digitalized SMEs. This difference in productive means affects the homogeneity assumption of investigations. So, definitions exclusively based on the number of employees are not the most appropriate for investigating SMEs under the DT process, and financial definitions are hard to compare.

The lack of a standard definition hardens different studies’ comparisons and may be considered one of the limitations of any SLR on the theme. In the current SLR, we assumed that all papers that used the acronym “SME” with the explanation “small and medium enterprises” and/or “small and medium-sized enterprises” were referring to a comparable term. We also assumed that, although it is not a synonym, the term “SME” could also encompass “micro” and “self-employed enterprises”.

Because of this limitation, we classified the accepted paper with empirical applications by the size of the investigated samples (Question 5), the continent where the investigated SMEs were established (Question 7), and whether the investigated SMEs were in developing or developed countries (Question 8). We assume that papers comparing more SMEs or encompassed SMEs in multiple countries and economies deal with a more standardized concept of an SME.

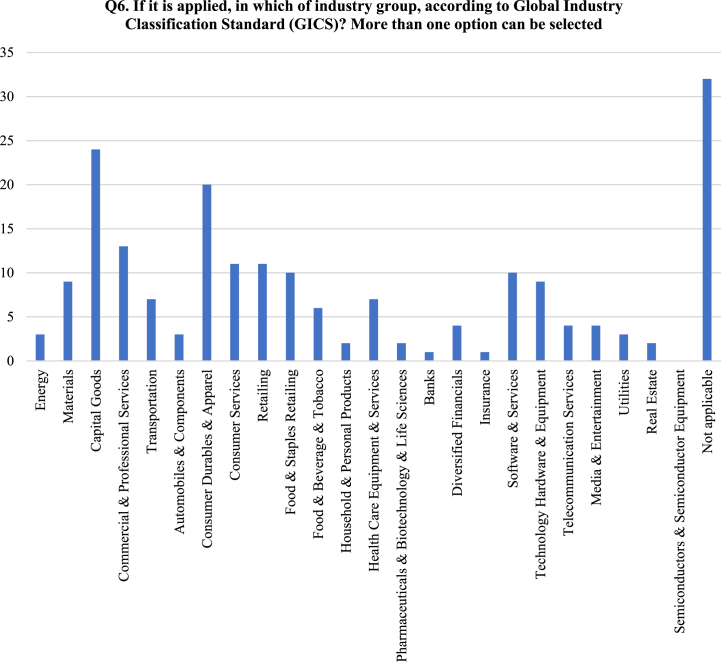

Once evidence suggests that different variables may affect SMEs’ performance depending on the industry [26], we classified empirical papers according to the 24 industry groups of the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) (Question 6) [27].

2.3. SMEs and internationalization

Also, the capacity for internationalization has become a competitive requirement for the survival and growth of many SMEs in different industries [28]. Evidence suggests that internationalization affects SMEs' performance [29]. However, researchers do not have a consensus on the impacts of DT on the internationalization of SMEs. Jin & Hurd [30] concluded that retailing SMEs in New Zealand that started to use Alibaba's digital marketplace eased their internalization. However, Joensuu-Salo et al. [28] concluded that DT did not affect the performance of fiber-based internationalized SMEs in Finland. Lee and Falahat [31] stated that DT is a necessary condition for SMEs' internationalization, though not sufficient. The DT must be coordinated with the enhancement of other resources and capabilities. Similarly, Dethine et al. [32] emphasized that DT for internationalization requires investments and changes in SMEs' internal practices through the mobilization of new resources and by implementing specific capabilities to manage them.

Given this context, we classified accepted papers between those that consider internationalization and those that do not (Question 2).

2.4. The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) of sustainability

The concept of sustainability is commonly based on three pillars: economic, social, and environmental. This is the concept of the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) proposed by Elkington [12]. After the COVID-19 pandemic, the relevance of considering the impacts of TBL on SMEs’ performance increased [33]. Because preliminary investigations showed that SMEs were the most affected by the pandemic and faced more difficulties from interrupting their operations, this may have caused long-term liquid problems and affected the maintenance of jobs [34], especially the female ones [35]. Also, SMEs tend to be less productive and pollute more [36].

However, integrated investigations of the TBL on the SMEs' performance keep under-researched in the extant literature. For example, Chen et al. [3] measured SMEs’ performance by considering almost exclusively aspects pertinent to economic performance. And Pfister and Lehmann [6] performed an SLR about the impact of digital transformation exclusively focused on the economic performance of SMEs. In both cases, the authors did not consider social and environmental pillars.

Ardito et al. [23] investigated how digital and environmental sustainability orientation enhances innovation in North American SMEs. Denicolai et al. [7] investigated how environmental sustainability readiness affected the relationship between DT and internationalization in Italian SMEs. Ukko et al. [37] investigated the impact of environmental sustainability on the relationship between DT and economic sustainability in Finnish SMEs.

Isensee et al. [38] executed an SLR about organizational culture, environmental sustainability, and DT. And Queiroz et al. [39] executed an SLR to understand the impact of DT on the Lean-Green in SMEs. However, none of the above-mentioned papers simultaneously addressed aspects pertinent to social sustainability, such as reducing poverty and gender inequality. These are Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN [40].

Because of this, we classified the accepted papers based on how they treated the three pillars of sustainability (Question 1). We assumed that all papers that investigated SMEs considered at least the economic pillar (represented by the answer “No” for Question 1).

3. Method

As recommended for new fields, the SLR was chosen for this research. This method allows the researcher to perform the mapping and evaluation of existing knowledge on the subject researched and provides conditions for a consistent definition of the research question that is being researched, helping to define the research gap more consistently [41]. The application of SLR for this study comes from the need to identify the stat-of-art for DT in SMEs, primarily mainly focusing on performance measurement.

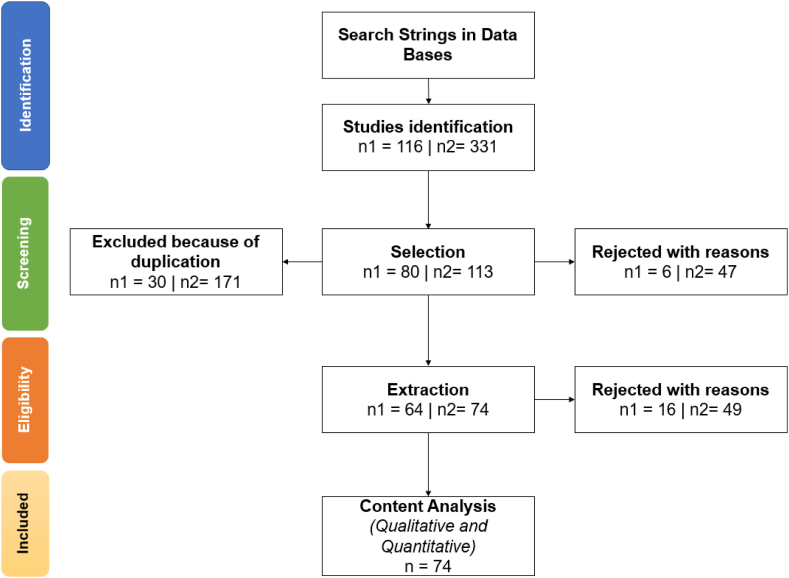

This SLR was based on the steps proposed in the PRISMA Statement Flow Diagram proposed by Ref. [42]. The full SLR process is detailed in Fig. 1, which illustrates the steps to provide transparency and replicability to the SLR process. Initially, the systematic review protocol was elaborated and validated jointly by the four researchers from the beginning of the search to the selection of articles. Throughout the development of the phases, meetings between researchers were held to evaluate the results and resolve any disagreements.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the review process supported by the StArt.

Before the first phase proposed in the PRISMA, the SLR was planned through a research protocol and with the research questions (RQs) formulation–already described in sections 1. Introduction and 2. Theoretical Constructs. So, the first phase was the studies Identification of the studies in the databases. The Studies were searched in two databases. The Scopus from Elsevier and The Web of Science (WoS) from Thomson Reuters Institute of Scientific Information, as can be seen in the Review Protocol (Appendix). They were chosen as they are regularly updated and have a wide breadth of coverage in most scientific subjects [43,44]. Also, these databases also established the quality threshold. Falagas et al. [45] investigated the strengths and weaknesses of the databases PubMed, Scopus, WoS, and Google Scholar for medical studies. In our case, PubMed was excluded from this investigation because it focuses on medicine and life sciences [45].

Harzing & Alakangas [46] investigated Scopus, WoS, and Google Scholar in cross-disciplinary research. Their results reveal constant and essentially steady quarterly growth for publications and citations across the three databases. The authors state that it implies that Scopus, WoS, and Google Scholar offer adequate coverage stability for use in further in-depth cross-disciplinary comparisons. Also, the authors declare that Scopus and Google Scholar became credible alternatives to WoS. However, Falagas et al. [45] argue that the use of Google Scholar may be controversial in some fields because of inadequacies and quality concerns. Given this, we chose to use the two databases whose quality is above controversy. So, the search string was inserted into these two databases.

Besides the quality threshold established by choice of databases, StArt software also enables quality score punctuation (from 0 to 100). The quality criteria (defined in the protocol) are displayed in the extraction activity, allowing the researchers to assign them to the studies and choose a value from a numeric scale to have a quality value calculated for each study. Thus, the researchers may reject a study if it does not meet a minimum quality value or just use the quality value to rank the studies [47].

As proposed by the PRISMA flow, there was a search conducted in the Identification phase, an analysis of the results, and documentation in the processing. In a complementary manner, Fig. 1 presents a flow diagram of the review process (“n1” is the first loop, executed in September, and “n2” is the second loop, executed in December), as supported by the StArt tool.

This process presented in Fig. 1 was supported by StArt. The StArt is an acronym for “State of the Art through Systematic Review”. It is a support tool that helps researchers to apply the SLR technique [48]. Also, the objectives are explicit in the 1. Introduction. The StArt tool permits the registration of the Review Protocol, where information about Primary Sources, Search Strings, Inclusion, and Qualification Criteria can be found. The search method was iterative with the support of the StArt tool. It was established that the Chronogram of the SLR was six months, starting in September and ending in February, with two search conducts (September and December 2021).

After the search was conducted, the results were transferred to the StArt, and the Screening process was done. The StArt automatically reads and searches for the desired keywords in the title, abstract, and keywords. If the keywords are found in the title, the StArt attributes five points per occurrence. Similarly, in the abstracts, StArt attributes three points per occurrence and, in the keywords, two points per occurrence. In the selection step, according to the final punctuation, the software classifies the reading priority into “Very Low”, “Low”, “High”, and “Very High”.

Following the reading priority, two independent analysts read the title, abstract, and keywords, attributed the “Study Selection Criteria” (Appendix), accepting or rejecting the paper. In the Eligibility phase, the extraction step was conducted, and the two independent analysts read the introduction, method, and results. The analysts reclassified the papers, reviewed criteria attribution, answered the 11 questions of the Data Extraction Form Fields (Appendix), and accepted or rejected papers.

The last phase proposed in the PRISMA statement step proposed is the Included that is regarding the Content Analysis. The planning and execution phases (selection and extraction) are registered in the StArt tool. In sequence, accepted papers were saved in Mendeley and organized with the support of an Excel spreadsheet (Summarization) to do a quantitative analysis aiming to do a bibliometric analysis and a qualitative analysis aiming to understand the constructs: digital transformation in SMEs, focusing on performance measurement. The results are summarized in the next sections.

4. Results and discussion

There was no time restriction to the search. Due to the novelty of the theme, among the 331 initially searched papers, the oldest paper was published in 2012, followed by five publications in 2016 and three in 2017. In 2018, 2019, and 2020, there were, respectively, 23, 44, and 94 published papers. The peak was reached in 2021, with 145 papers (45.74%). And there were also 16 papers in the press to be published in 2022. This is evidence of the increasing and recent interest in the theme, probably catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As can be seen in Fig. 1, the SLR started with 331 searched papers. Then, 171 papers were removed because they were duplicated (51.66%). In sequence, 86 were rejected with a registered reason (25.98%). Finally, 74 were accepted (22.36%). The accepted papers followed a similar time distribution, i.e., an increasing number of publications in recent years.

4.1. Journals

Initially, we checked how many journals published papers on the topic analyzed in this research, and the search resulted in 57 journals. This indicates the novelty of the theme once there are still no predominant sources of publication. Table 1 presents the journals and the number of papers published per year.

Table 1.

Papers’ time distribution per journal.

| Journal | Years |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | Total | |

| Sustainability | 3 | 3 | 6 | ||||||

| Journal of Business Research | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |||||

| Technology Innovation Management Review | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Applied Sciences | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Technological Forecasting & Social Change | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Academy of Strategic Management Journal | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Administrative Sciences | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Annals of Operations Research | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Applied Economics Letters | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Business Process Management Journal | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Cogent Economics & Finance | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Cogent Engineering | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Decision Science Letters | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Economic Annals | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| European Journal of Innovation Management | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| European Journal of Management and Business Economics | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| European Management Journal | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Frontiers in Psychology | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Frontiers of Business Research in China | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Global Business Review | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Information | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Information Systems Frontiers | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Intangible Capital | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| International Journal of Agile Systems and Management | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| International Journal of Criminology and Sociology | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| International Journal of Data and Network Science | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| International Journal of Information Management | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| International Journal of Innovation Management | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| International Journal of Production Economics | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| International Journal of Supply Chain Management | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Internet Research | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Journal of Competitiveness | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Journal of Enterprise Information Management | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Journal of Enterprising Culture | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Journal of Global Information Management | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Journal of Strategic Marketing | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Knowledge and Process Management | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Long Range Planning | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Management Decision | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Polish Journal of Management Studies | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Social Sciences & Humanities | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Technovation | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Telecommunications Policy | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Total | 1 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 24 | 29 | 5 | 5 | 74 |

At the bottom of Table 1, we presented the number of papers published each year. The oldest was published in 2016 (by the journal “Internet Research”), followed by three in 2018 and seven in 2019. In 2020, 2021, and 2022, there were, respectively, 24, 29, and 5 accepted papers. Nine journals published more than one paper. They were: “Sustainability” (6), “Journal of Business Research” (5), “Technology Innovation Management Review” (3), “Technological Forecasting and Social Change” (3), “Competitiveness Review” (2), “Journal of Cleaner Production” (2), “Applied Sciences” (2), “Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship” (2), and “Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business” (2). Most of these are leading journals once they are indexed in Journal Citation Report (JCR) listed journals and Chartered Association of Business Schools journals’ ranking list. They may become a prominent source of publications.

4.2. Countries

Fig. 2 presents the map of countries with scientific production on sustainable SMEs’ performance. Italy, China, Finland, Indonesia, and the UK are the countries that most developed research on the topic, publishing 11, 9, 8, and 7 papers, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Publications per country of affiliation of the first author.

Table 2 shows the 42 countries that have published papers on the topic in the databases, reporting in detail the quantity published by each country. The Single Paper (SP) column informs that the paper was written only by authors from the country. First Paper (FP) indicates international collaboration, signaling that the first author is affiliated with the country in question. Collaboration Paper (CP) also indicates that the publication was developed through international collaboration; however, the first author is not from the country in question. Finally, Total Paper (TP) refers to the sum of all publications.

Table 2.

Distribution of the paper per country of affiliation of each author.

| Country | TP | TP (%) | SP | FP | CP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 11 | 14.86% | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| China | 9 | 12.16% | 3 | 6 | |

| Finland | 9 | 12.16% | 6 | 3 | |

| Indonesia | 8 | 10.81% | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| UK | 7 | 9.46% | 3 | 4 | |

| Spain | 6 | 8.11% | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| France | 5 | 6.76% | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Germany | 5 | 6.76% | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| USA | 5 | 6.76% | 5 | ||

| Austria | 4 | 5.41% | 4 | ||

| Malaysia | 4 | 5.41% | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Brazil | 2 | 2.70% | 1 | 1 | |

| Canada | 2 | 2.70% | 1 | 1 | |

| Czech Republic | 2 | 2.70% | 2 | ||

| Hungary | 2 | 2.70% | 2 | ||

| India | 2 | 2.70% | 1 | 1 | |

| Netherlands | 2 | 2.70% | 1 | 1 | |

| Pakistan | 2 | 2.70% | 2 | ||

| Russia | 2 | 2.70% | 1 | 1 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 2 | 2.70% | 1 | 1 | |

| Serbia | 2 | 2.70% | 1 | 1 | |

| Slovakia | 2 | 2.70% | 1 | 1 | |

| Slovenia | 2 | 2.70% | 1 | 1 | |

| Switzerland | 2 | 2.70% | 2 | ||

| Taiwan | 2 | 2.70% | 2 | ||

| Thailand | 2 | 2.70% | 2 | ||

| Argentina | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Australia | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Chile | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Colombia | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Georgia | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Greece | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Iran | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Japan | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Jordan | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Nepal | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Portugal | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| South Korea | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Sweden | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 1.35% | 1 | ||

| Vietnam | 1 | 1.35% | 1 |

Analyzing the top five countries (Italy, China, Finland, Indonesia, and the UK), it is possible to note that except for the UK, all the others tend to publish in collaboration with researchers from the same country. Although one of the most productive countries, Finland stands out as a unique country that did not collaborate with other countries. This tendency to do research without international collaborations may affect the possibility of executing cross-country investigations about SMEs [5,49].

Table 3 shows the 161 institutions (universities, research centers, companies etc.) that have published papers on the topic in the databases, reporting in detail the quantity published by each institution. The Single Paper (SP) column informs that the paper was written only by authors from the university. First Paper (FP) indicates institutional collaboration, signaling that the first author is affiliated with the institution in question. Collaboration Paper (CP) also indicates that the publication was developed through institutional collaboration; however, the first author is not from the institution in question. Finally, Total Paper (TP) refers to the sum of all publications.

Table 3.

Distribution of the paper per institution of affiliation of each author.

| University | TP | TP (%) | SP | FP | CP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUT University | 3 | 4,05% | 3 | ||

| University of Turin | 3 | 4,05% | 1 | 2 | |

| Seinäjoki University of Applied Sciences | 2 | 2,70% | 2 | ||

| Telkom University | 2 | 2,70% | 1 | 1 | |

| Università Politecnica delle Marche | 2 | 2,70% | 1 | 1 | |

| University of Lorraine | 2 | 2,70% | 1 | 1 | |

| University of Málaga | 2 | 2,70% | 1 | 1 | |

| Åbo Akademi University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Al-Balqa Applied University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Alexander Dubček University of Trenčín | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Amity University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Amrita Sai Institute of Science and Technology | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Aston University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Beijing Normal University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Beijing Union University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Beijing University of Technology | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| BLC Group | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| California State Polytechnic University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Catarinense Federal Institute | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Caucasus University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Chiang Mai University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Comillas Pontifical University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Corregedoria Regional da Polícia Federal no Estado do Paraná | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Corvinus University of Budapest | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Czech University of Agriculture in Prague | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Dalian University of Technology | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Danube University Krems | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Delft University of Technology | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Entrepreneurship Northwest | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Fachbereich Wiesbaden Business School | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Faculty of Information Studies in Novo Mesto | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Federal University of Santa Catarina | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Flores University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| FPT University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Fundação Getúlio Vargas | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Gadjah Mada University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Government College of Management Sciences | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Graz University of Technology | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Hanken School of Economics | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Hansung University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Hazara University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Institute of Technology and Business in České Budějovice | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| International University of La Rioja | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Islamic University of Indonesia | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Jaypee University of Engineering and Technology | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Jiangsu University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Jilin University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Jouf University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| KEDGE Business School | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| KSRM College Of Engineering (A) | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| La Rochelle Business School | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| LBEF Campus | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Leonardo de Vinci University Center | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Link Campus University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Luleå University of Technology | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Lund University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Madan Mohan Malaviya University of Technology | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Management Development Institute | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Marconi International University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Menlo College | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Metropolitan University Prague | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Modern Business School | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Mount Royal University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| National Cheng Kung University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| National Dong Hwa University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| National Kaohsiung Normal University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| National Research University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| National Research University Higher School of Economics | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| National Taiwan University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| National Technical University Athens | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Old Dominion University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Open University of Catalonia | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Osnabrück University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Oxford Brookes University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Paris School of Business | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Polytechnic University of Bari | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Polytechnic University of Turin | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Pontifical Catholic University of Parana | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Prince Sultan University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| PSN College of Engineering and Technology | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Renmin University of China | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Salzburg University of Applied Sciences | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| São Camilo University Center | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| SASTRA Deemed University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| School of Management Fribourg | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Shanghai Jiao Tong University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Sitchting GreenEcoNet | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Slovak University of Agriculture | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Sree Kavitha Institute of Management | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| STIE Bank BPD Jateng | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Sukkur IBA University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| SVKM’S NMIMS University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Technical University of Darmstadt | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Tokyo Institute of Technology | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Tsinghua University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| United Arab Emirates University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universidad Católica del Norte | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universidad EAN | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universidad Nacional del Sur | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universidade da Beira Interior | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universita Ca' Foscari Venezia | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Università del Piemonte Orientale | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universita LUM Jean Monnet | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universitas Islam Negeri Sultan Syarif Kasim Riau | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universitas Islam Sultan Agung | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universitas Kristen Petra | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universitas Muria Kudus | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universitas Stikubank Semarang | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Université Du Québec À Trois-Rivières | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universiti Malaysia Pahang | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universiti Sains Malaysia | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universiti Teknologi Malaysia | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Universiti Utara Malaysia | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Applied Sciences Osnabrück | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Belgrade | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Calabria | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Catania | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Derby | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Deusto | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Eastern Finland | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Innsbruck | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of International Business and Economics | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Leicester | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Lincoln | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Maribor | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Modena and Reggio Emilia | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Pavia | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Pecs | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Queensland | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Rome Tor Vergata | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Salento | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of São Paulo | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Siegen | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of South Florida | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Southampton | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of St. Gallen | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Sunderland | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Tehran | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Trento | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Turku | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Vaasa | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Valladolid | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Warwick | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Westminster | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of York | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| University of Žilina | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Uva Wellassa University of Sri Lanka | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Vienna University of Applied Sciences | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Wuhan University of Technology | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Xi'an Jiaotong University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 | ||

| Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University | 1 | 1,35% | 1 |

Besides the tendency to collaborate inside the same country, researchers tend to collaborate only with colleagues from the same institution.

Table 3 and Fig. 3 show that authors from 32 countries developed research in international collaboration. For Souza & Barbastefano [50], the increase of papers with multiple authors in an area can be explained by the presence of new collaborative tools, government funding (stimulating cooperation among institutions), sharing of high costs with research and development, the need for specialization and the interdisciplinary character of the current science.

Fig. 3.

Network of collaborations on the theme sustainable performance of SMEs.

Collaboration between authors from different countries forms a social network that a graphic can represent. Fig. 3 shows the social network formed between authors from the countries to develop papers published on the topic. Each vertex represents a country, and the borders correspond to the connections between these countries through publications in partnership.

We created Fig. 3, Table 2, Table 3 using the UCINET tool, as according to Moreno-Mendoza et al. [51], it is one of the most popular software packages for the structural analysis of social networks. The informative visualization tool called UCINET is propitious to identify the position of some influential kinds of literature [52]. UCINET uses matrix representations of networks as input data and can provide a rich set of characterizations [53].

This paper analyzes the social network established among countries whose researchers published studies on the theme to check the most influential nations. In the social network analyzed in this paper, centrality and betweenness indicators are presented. According to Badar et al. [54], a centrality degree provides the benefits of knowledge sharing via direct links, and a betweenness degree provides the benefits of brokerage and control of knowledge by having links that span social divides. The greater the degree of an individual, the more the individual tends to be in a central position and the more relationships with it [55].

Table 4 presents the centrality indexes of the countries of the collaboration network presented in Fig. 3. The centrality degree represents the number of direct links of a country, containing both input and output degrees.

Table 4.

Centrality indexes of the countries of the collaboration network.

| Country | Degree | Normalized degree |

|---|---|---|

| UK | 17.000 | 0.138 |

| Italy | 11.000 | 0.089 |

| Austria | 9.000 | 0.073 |

| France | 9.000 | 0.073 |

| China | 7.000 | 0.057 |

| USA | 7.000 | 0.057 |

| Germany | 6.000 | 0.049 |

| Spain | 6.000 | 0.049 |

| Argentina | 5.000 | 0.041 |

| Brazil | 5.000 | 0.041 |

| Chile | 5.000 | 0.041 |

| Colombia | 5.000 | 0.041 |

| Finland | 5.000 | 0.041 |

| Russia | 5.000 | 0.041 |

| Indonesia | 4.000 | 0.033 |

| Iran | 3.000 | 0.024 |

| Malaysia | 3.000 | 0.024 |

| Netherlands | 3.000 | 0.024 |

| Pakistan | 3.000 | 0.024 |

| Switzerland | 3.000 | 0.024 |

| Georgia | 2.000 | 0.016 |

| India | 2.000 | 0.016 |

| Nepal | 2.000 | 0.016 |

| Saudi Arabia | 2.000 | 0.016 |

| Sweden | 2.000 | 0.016 |

| Australia | 1.000 | 0.008 |

| Canada | 1.000 | 0.008 |

| Serbia | 1.000 | 0.008 |

| Slovakia | 1.000 | 0.008 |

| Slovenia | 1.000 | 0.008 |

| Sri Lanka | 1.000 | 0.008 |

| United Arab Emirates | 1.000 | 0.008 |

| Czech Republic | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Greece | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Hungary | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Japan | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Jordan | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Portugal | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| South Korea | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Taiwan | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Thailand | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Vietnam | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Although Italy is the most productive country, the UK has established more partnerships with other countries in published papers. This prominent position is reflected in the centrality index.

Table 5 presents the betweenness indexes of the countries of the collaboration network presented in Fig. 3. The betweenness is the power of control potential of a country concerning others that depend on it to interact and the possibility of transforming in any way the social relations in which it is involved [56]. The betweenness index is divided into betweenness (number of node pairs that a country can link) and normalized betweenness (representation of degree in percentage).

Table 5.

Betweenness indexes of the countries of the collaboration network.

| Country | Betweenness | Normalized betweenness |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 95.450 | 11.640 |

| China | 85.000 | 10.366 |

| UK | 81.850 | 9.982 |

| France | 66.450 | 8.104 |

| Austria | 39.567 | 4.825 |

| Germany | 38.000 | 4.634 |

| Italy | 34.783 | 4.242 |

| Spain | 27.450 | 3.348 |

| Switzerland | 19.350 | 2.360 |

| Finland | 12.100 | 1.476 |

| Russia | 7.950 | 0.970 |

| Netherlands | 4.050 | 0.494 |

| Indonesia | 4.000 | 0.488 |

| Malaysia | 3.000 | 0.366 |

| Argentina | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Australia | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Brazil | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Canada | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Chile | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Colombia | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Czech Republic | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Georgia | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Greece | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Hungary | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| India | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Iran | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Japan | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Jordan | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Nepal | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Pakistan | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Portugal | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Serbia | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Slovakia | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Slovenia | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| South Korea | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Sri Lanka | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Sweden | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Taiwan | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Thailand | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| United Arab Emirates | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Vietnam | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Abbasi et al. [57] stated that the betweenness degree of an existing node is a significantly better predictor of preferential attachment by new entrants than the centrality degree because authors with a high betweenness degree can be seen as supervisors. According to Table 5, the USA presented the highest betweenness degrees, being an essential collaborative country in the network. Its researchers have great mediation for developing papers, and they can act as a conduit for propagating information [58].

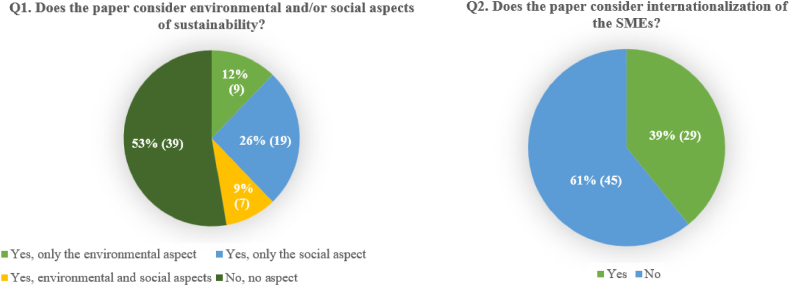

4.3. Papers’ analysis

Fig. 4 summarizes the results of Questions 1 and 2 from the Data Extraction Form Fields (Appendix). As can be seen, 53% of the papers considered neither social nor environmental sustainability. Though 26% considered social sustainability only, 12% environmental only, and 9% both. And 61% of the papers did not consider internationalization. The fact that the minority of papers consider internalization can cause a direct consequence of the lack of a universally accepted definition of what an SME is. Researchers investigating micro and self-employed enterprises may not be interested in internationalization. While researchers investigating larger SMEs from some business subsectors (such as tourism) may be interested. Further investigations should clearly establish their definitions for an SME focus on sectorial analysis.

Fig. 4.

Summarization of the answers for Questions 1 and 2 (from Data Extraction Form Fields). The number of analyzed elements is in parentheses after the percentage.

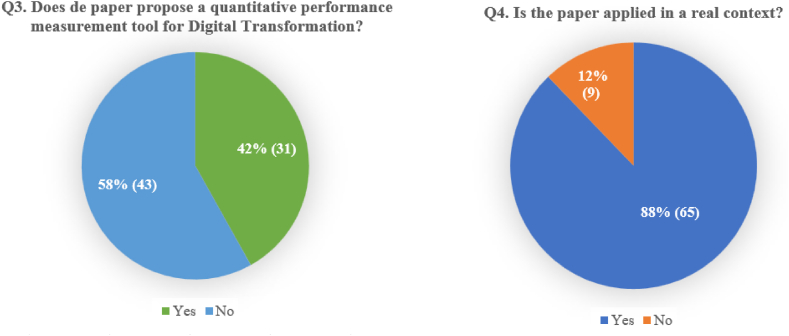

Fig. 5 summarizes the results of Questions 3 and 4 from the Data Extraction Form Fields (Appendix). Only 42% of the analyzed paper directly proposed a quantitative approach for measuring digital transformation performance, and 88% of the papers presented empirical applications. This may indicate that the theoretical background of the theme is still under construction, and there is a gap in developing quantitative approaches for measuring the digital transformation performance of SMEs.

Fig. 5.

Summarization of the answers for Questions 3 and 4 (from Data Extraction Form Fields). The number of analyzed elements is in parentheses after the percentage.

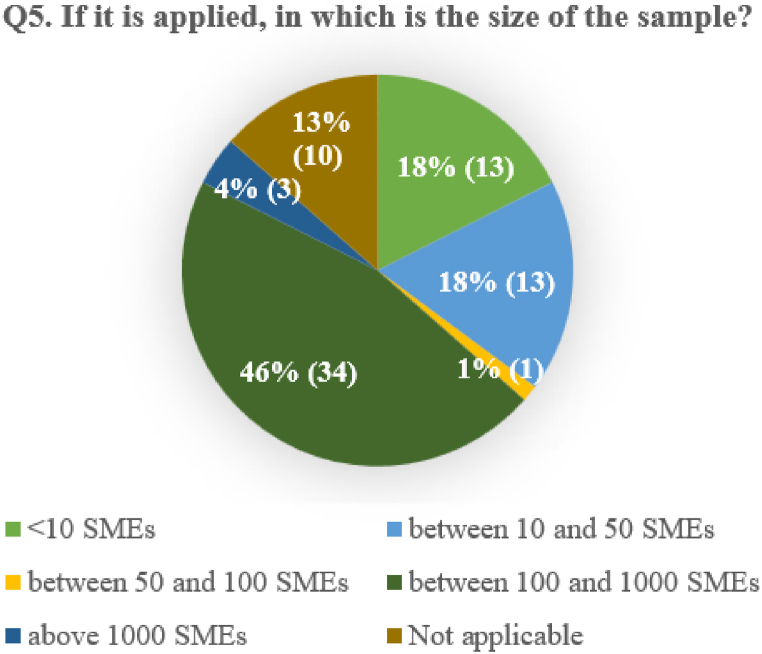

Fig. 6 summarizes the results of Question 5 from the Data Extraction Form Fields (Appendix). It shows that 46% of the paper with empirical applications dealt with samples between 100 and 1000 SMEs. Eighteen percent deal with samples between 10 and 50 SMEs. There is still a lack of papers that deal with more than 1000 SMEs (4%). This may represent a potential area to be investigated using big data techniques. Similarly, papers that deal with samples between 50 and 100 SMEs are the rarest (1%), probably due to methodological constraints. This sample size is seen as “too big” for most qualitative approaches and “too small” for most non-deterministic quantitative approaches.

Fig. 6.

Summarization of the answers for Questions 5 (from Data Extraction Form Fields). The number of analyzed elements is in parentheses after the percentage.

Fig. 7 summarizes the results of Question 6 from the Data Extraction Form Fields (Appendix). The most investigated industry groups are those related to the manufacturing sector: Capital Goods, Consumer Durable & Apparel, Technology Hardware & Equipment, and Material. Followed by industry groups related to the service sector: Commercial & Professional Services, Consumer Services, Retailing, Food & Staple Retailing, Software Services, Health Care Equipment & Services, and Transportation.

Fig. 7.

Summarization of the answers for Questions 6 (from Data Extraction Form Fields).

There is a lack of papers in the industry groups of Automobiles & Components, Food & Beverage & Tobacco, Household & Personal Products, Energy, Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology & Life Sciences, Banks, Diversified Financials, Insurance, Telecommunication Services, Media & Entertainment, Utilities, Real State, and Semiconductors & Semiconductor Equipment. Probably, there are no SMEs in certain industry groups due to business environment characteristics. However, for the mentioned industry groups where there are SMEs, there is a gap in research.

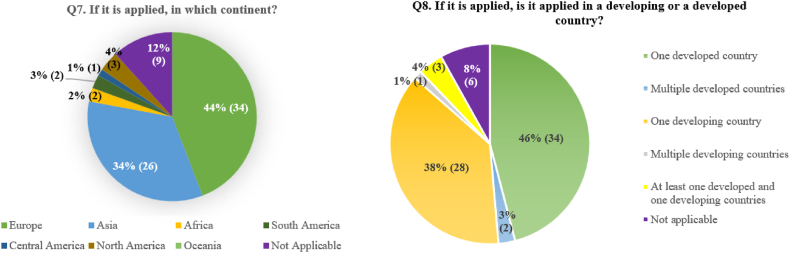

Fig. 8 summarizes the results of Questions 7 and 8 from the Data Extraction Form Fields (Appendix). Forty-four percent of the empirical papers were in Europe, and 34% were in Asia. There is a lack of investigations in North America (only 4%), South America (3%), and Central America (1%). The whole American continent corresponds to 8% of the investigations. Only 1% of the investigations were in Africa and none in Oceania. Forty-six percent of the papers considered SMEs only in a unique, developed country, and 38% of the papers considered SMEs only in a unique, developing country. Only 16% of the papers considered SMEs in different countries. In this case, most papers investigated SMEs in multiple developed countries. There is a lack of investigations considering multiple countries, especially developing countries, and comparative investigations between SMEs in developed and developing countries.

Fig. 8.

Summarization of the answers for Questions 7 and 8 (from Data Extraction Form Fields). The number of analyzed elements is in parentheses after the percentage.

Fig. 9 summarizes the results of Questions 9 and 10 from the Data Extraction Form Fields (Appendix). Eighty-four percent of the papers dealt with primary data. Among papers that used secondary or mixed data, it is worth noting two cases due as examples of data and definition standardization for SMEs. Zhu et al. [59] investigated 1000 SMEs in China based on the micro-survey data, China Enterprise Surveys (CES), launched by the World Bank. Wang and Bai [60] investigated 303 SMEs that are publicly listed on China's GEM, which is the board of the Shenzhen Stock Exchange. The goal of GEM is to provide a financial channel for SMEs with high-tech orientation and growth potential [61]. SMEs listed on the GEM are expected to answer to restrict regulation strict regulations to disclose financial and operational data for the market [61]. Consequently, they can be good samples for investigating the relationship between firm-specific characteristics and performance in China [61]. We argue that similar models could be followed by other countries and economic regions.

Fig. 9.

Summarization of the answers for Questions 9 and 10 (from Data Extraction Form Fields). The number of analyzed elements is in parentheses after the percentage.

Sixty-three percent of the papers applied quantitative approaches, 26% qualitative, and 8% mixed approaches. Once there are demonstrated gains in applying mixed approaches in the management literature [62,63], there is a gap for applying more mixed approaches in this context.

Finally, Table 6 summarizes the results of Question 11 from the Data Extraction Form Fields (Appendix). As can be seen, the most used quantitative approaches are those related to exploratory data analysis and statistical tests (“Regressions”), 46% of quantitative approaches. The second most used quantitative approaches are those related to multivariate analysis (28%), followed by a simple quantitative description of the sample (14.5%). Two groups of multi-criteria decision approaches were identified, one related to fuzzy logic and another to Decision Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL). Two papers used both techniques integrated.

Table 6.

Summarization of the answers for Questions 11 (from Data Extraction Form Fields).

| Method | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Regressions | 32 |

| Hierarchical | 10 |

| Linear (Least Square) | 9 |

| Linear (Partial Least Square) | 2 |

| Logit | 1 |

| Probit | 2 |

| Tobit | 2 |

| Bootstrap | 3 |

| Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | 3 |

| Multivariate Analysis | 19 |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | 1 |

| Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) | 2 |

| Cluster Analysis (K-Means) | 1 |

| Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) | 15 |

| Descriptive Statistics | 10 |

| Methods integrated with fuzzy logic | 4 |

| T-spherical fuzzy cloud model | 1 |

| Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (F-AHP) | 1 |

| Fuzzy DEMATEL | 2 |

| DEMATEL | 4 |

| Grey Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (G-DEMATEL) | 1 |

| DEMATEL based Analytical Network Process (DANP) | 1 |

| Fuzzy DEMATEL | 2 |

It is worth noting that no paper applied a quantitative method for measuring performance, such as Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) and Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), was applied. There is an avenue for future research regarding performance measurement. Particularly, the DEA models are mostly deterministic [64,65], though there are also non-deterministic models [66]. The use of a deterministic model may enable investigations with smaller samples (such as from 50 to 100 SMEs). Besides, developing countries may have fewer SMEs than developed countries, and researchers in developing countries may have more limited resources than their colleagues in developed countries. In this regard, the use of deterministic models may enable and facilitate significant research (in conditions under limited resources).

Finally, no paper applied techniques of machine learning, probably because of the constraints of data availability and the lack of data standardization. Papers that could investigate more than 1000 SMEs were scarce. We argue that there is an urgent necessity for an international systematization regarding SMEs, their characteristic measures, and data collection.

4.4. Conceptual framework

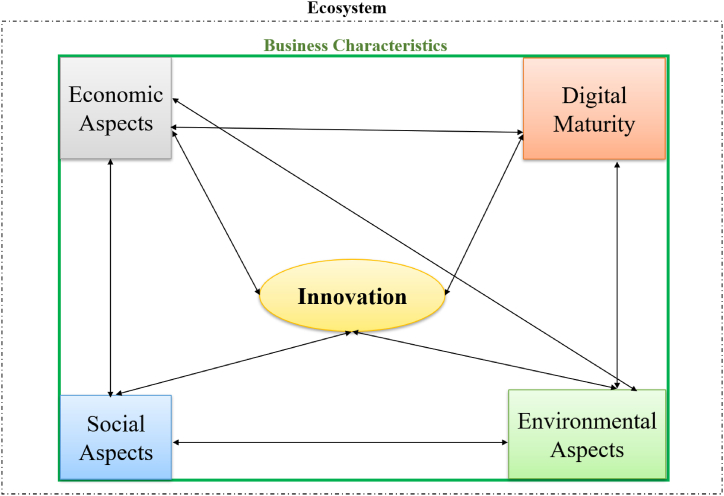

The term “performance” in this paper encompasses operational and financial performance. As represented in Fig. 10, SMEs’ performance (dependent variable) is proposed to be the direct result of four pillars, i.e., economic aspects, social aspects, environmental aspects, and digital maturity (independent variables). However, the allocation of these aspects depends on the characteristics of the SME and the ecosystem where the SME is inserted (environmental variables).

Fig. 10.

Conceptual framework affecting the SMEs' performance.

The term “business characteristics” imply contextual factors such as the industry, age, size, ownership etc. Also, “business characteristics” encompass enablers such as the business model (BM) and strategy. It is particularly important how SME inserts innovation in its BM and strategy, as well as how the ecosystem deals with innovation. Innovation is expected to have a mediating effect between the four pillars and the resulting performance.

Ecosystems represent competitors, suppliers, customers, regulatory systems, governmental programs etc. For example, government programs may foster the digital maturity of SMEs [67]. And the use of a digital platform to connect with customers, suppliers, and competitors may improve the SMEs’ learning capabilities [24]. All these ecosystem aspects may be affected by the level of internationalization [28].

Bouwman et al. [68] investigated whether SMEs that undergo DT perform better when they allocate more resources for BM experimentation and engage more strategy implementation. The authors confirmed that spending time and resources on both contribute to overall firm performance. However, they recognize that no single condition is the cause of an outcome of a better firm's performance. On the other hand, several conditions act in combination to cause better performance. Furthermore, they state that innovativeness plays an important role, mediating the relationships between resources for BM experimentation as well as BM strategy implementation and the overall firm performance.

The authors see innovativeness as the practical aspect of innovation [68]. Here it is referred to as innovation. Innovation was also the adopted term by Holopainen et al. [25] when investigating the impact of the market and technological orientation in healthcare SMEs. Saunila [69] showed that three aspects of innovation capability have some effect on different aspects of SME performance. Saunila [69] concluded that the relationship between innovation capability and SMEs’ performance is significant in the presence of performance measurement. Given this, investigations on measuring performance represent a direct effort to improve innovation. Saunila [70] proposed a framework for improving innovation capability through performance measurement in SMEs. The framework proposed by this paper interacts with the framework proposed by the author because we consider “business characteristics” what she considers “contextual factors” and “enablers”. We consider that “work climate and well-being” and “leadership culture” belong to the pillar social aspects. So, her framework illustrates the bi-directional relationship between innovation and social aspects. Ardito et al. [23] investigated how digital and environmental orientations affect the innovation performance of SMEs. The authors concluded that both affect innovation performance.

However, when SMEs adopt both orientations jointly, it has a negative impact on innovation [23]. Also, Ukko et al. [37] suggested that sustainability strategy serves as a promoter in the relation between managerial capability and financial performance but inhibits the relation between operational capability and financial performance. Given these pieces of evidence it is expected that good performance is the result of delicate trade-off among the four pillars, once they can positively or negatively influence each other. The nature of this influence may differ depending on the business characteristics, mainly on the BM. However, further investigation is required.

5. Conclusions

Our bibliometric results also show that the researchers with the most publications on measuring the sustainable performance of SMEs passing through the DT process are affiliated with institutions in Italy, China, Finland, Indonesia, and the UK. These researchers tend to collaborate with other researchers in the same country and even in the same institution. Although Italy is the most productive country, the centrality index proves that the UK has established more partnerships with other countries. Also, the betweenness degree shows that researchers affiliated with institutions in the USA are essential to the international research network. These researchers have great mediation for developing papers, and they can act as a conduit for propagating information.

Based on our SLR findings, our first conclusion is that measuring the sustainable performance of SMEs passing through the DT process is a theme with recent increasing interest. Possibly, the interest was catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic (from 2020 on). Consequently, although there are nine leading academic journals publishing on the theme, none of them is already established as a predominant authority on the theme. Also, our findings indicate there are still theoretical and practical gaps in investigations regarding measuring SMEs’ performance, simultaneously considering the DT process and the TBL of sustainability.

The practical aspects of our SLR findings were the following: (1) There are more papers in the manufacturing industry than in the services; (2) SMEs in some specific industries are under-investigated, i.e., automobiles & components, food & beverage & tobacco, household & personal products, media & entertainment etc.; (3) SMEs in some geographical regions are under-investigated (i.e., the three American continents, Africa, and Oceania); (4) There are few papers cross-country investigations, especially considering countries from developing economies; (5) Few papers used more than 1000 SMEs in their samples. Also, a few papers did cross-temporal investigations. This may be a consequence of a lack of standardized data; (6) Most papers applied regressions and structural equation modeling (SEM), but few papers applied mixed methods or performance measurements tools such as the non-deterministic Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) or the deterministic Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). Further investigations are recommended to fill these gaps.

We proposed a framework for measuring the sustainable performance of SMEs passing through the DT process as a theoretical result of our SLR. It is recommended for future research to validate this framework. Also, our findings suggest that different papers work with different definitions of SMEs. The proposition of a standardized and widely accepted definition of SME would be a significant contribution to the body of knowledge. Particularly, besides the different definitions of SMEs in each industry and country, it is possible to imagine that SMEs in the same industry may be non-homogeneous (i.e., different sizes, ages, ownerships, business models, strategies etc.). And this lack of homogeneity may affect performance and compromise benchmarking. Further investigations could define SMEs based on the concept of homogeneity. In this regard, cross-country collaborations and investigations would contribute to widening the cross-country and cross-industry definition of SME and DT process in SMEs.

Digital Transformation is an area with maturity, and many systematic reviews exist. However, few are elaborated on DT in SMEs. A search for the terms “digital transformation” and “SME” in December 2022 (one year after the last search of the current SLR) resulted in three literature reviews. Chavez et al. [71] examined the literature on digitalization in SMEs when handling deviations and analyzed the integration of digital tools. Using PRISMA 2020 approach, Madhavan et al. [72] investigated pre-pandemic and pandemic-period research interest in Industry 4.0 and 5.0 for SMEs. In agreement with our findings, the authors concluded that there is an increasing interest during the pandemic and a conceptual shift during this period for five interest focus. Queiroz et al. [39] applied Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), a machine learning technique, to perform an SLR investing how DT can be an enabler of lean-green practices in SMEs. The LDA technique is expected to be cost-saving and faster for SLR. Further investigations are recommended to explore other SLR tools, such as machine learning techniques.

On the other hand, a search for the terms “digital transformation” and “performance” in December 2022 resulted in 58 literature reviews. And another search for “performance” and “digital transformation” resulted in 141 literature reviews. This indicates that a meta-review focused on performance measuring that secondarily encompasses DT and SMEs is highly recommended.

All research presents limitations, and ours is no exception. However, these limitations can serve as guidelines for further research avenues and roads, enabling the knowledge flow for knowledge building in the field. The main limitation of our research is the limited number of papers (74). For further investigations, we recommend encompassing conference papers. This agrees with the results of Madhavan et al. [72], that found a significant number of papers at conferences. Also, alternative databases, e.g., Google Scholar, may be explored, but using checklists that would allow measuring the quality of the selected article, such as the Critical Appraisal Skills Program [73].

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research is funded by Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (Fondecyt) Project 11230332.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Additional information

Supplementary content related to this article has been published online at [URL].

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Appendix.

The protocol of our systematic literature review is presented in Table 7. This protocol is also registered in the StArt software.

Table 7.

Adopted protocol for the systematic literature review (SLR).

| Literature review protocol | ||

|---|---|---|

| Objective | To describe and analyze the state-of-art for performance evaluations of Digital Transformation in SMEs. Also, to investigate if these tools encompass sustainability (environmental, social, and economic). Besides, identify the institutions and journals leading the publications on the theme. | |

| Research Question | Main Question: What is the state-of-art of Digital Transformation on the performance of SMEs? | |

| Secondary Question 1: Are there papers proposing tools, dimensions, and variables for measuring the impacts of Digital Transformation on the performance of SMEs? | ||

| Secondary Question 2: If so, do these tools, dimensions, and variables also encompass the three pillars of sustainability (environmental, social, and economic)? | ||

| Keywords and Synonyms | digital transformation; digital transition; digital innovation; digitalization; SME; small and medium enterprises; small and medium-sized enterprises; small and medium business; small and medium-sized business; small and middle enterprises; small and mid-sized enterprises; small and middle compan*; small and middle firm; covid; coronavirus; performance; pandemic; evaluation; measurement | |

| Source Selection Criteria Definition | Criteria: The sources should be available and globally recognized as high-quality sources. | |

| Studies Language: English | ||

| Source Search Methods: The sources should be available and globally recognized as high-quality sources. | ||

| Source List: Web of Sciences; Scopus | ||

| Study Selection Criteria | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|

|

|

| Studies Type Definition | Papers and literature reviews published in journals | |

| Studies Initial Selection: | Initial search executed in September 2021 | |

| Studies Quality Evaluation: | The quality is defined by the data basis selected | |

| Data Extraction Form Fields | 1. Does the paper consider environmental and/or social aspects of sustainability? | |

| A. Yes, only environmental; B. Yes, only social; C. Yes, environmental, and social; D. No | ||

| 2. Does the paper consider the internationalization of SMEs? | ||

| A. Yes; B. No | ||

| 3. Does de paper propose a quantitative performance measurement tool for Digital Transformation? | ||

| A. Yes; B. No | ||

| 4. Is the paper applied in a real context? | ||

| A. Yes; B. No | ||

| 5. If it is applied, what is the size of the sample? | ||

| A. <10 SMEs; B. Between 10 and 50 SMEs; C. Between 50 and 100 SMEs; D. Between 100 and 1000 SMEs; E. Above 1000 SMEs; F. Not applicable (in case answer 4 is no) | ||

| 6. If it is applied, according to the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS), in which industry group? More than one option can be selected | ||

| All the 24 industry groups of the GICS, followed by the options “Not possible to determine through the paper”, and “Not applicable (in case answer 4 is no)”. | ||

| 7. If it is applied, in which continent? More than one option can be selected | ||

| A. Europe, B. Asia, C. Africa, D. South America, E. Central America, F. North America, G. Oceania. H. Not possible to determine through the paper, I. Not applicable (in case answer 4 is no). | ||

| 8. If the paper is applied, is it applied in a developing or a developed country? | ||

| A. One developed country; B. Multiple developed countries; C. One developing country; D. Multiple developing countries; E. At least one developed and one developing country; F. Not possible to determine through the paper; G. Not applicable (in case answer 4 is no). | ||

| 9. What is the data? | ||

| A. Primary data; B. Secondary data; C. Primary and secondary data | ||

| 10. What is the method? | ||

| A. Qualitative; B. Quantitative; C. Mixed Methods | ||

| 11. In the case of a method that encompasses quantitative approaches, which is the used approach? More than one option can be selected | ||

| A list of approaches established through the extraction of the papers (e.g., structural equations, Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) etc.) followed by the options “Not applicable” (in case the paper is exclusively qualitative). | ||

| Results Summarization | The summarization of the results is elaborated through an Excel spreadsheet. Accepted papers are also saved in Mendeley. The state-of-art is established and summarized. The findings will be published in a literature review. | |

References

- 1.Grover V., Kohli R. Revealing your hand: caveats in implementing digital business strategy. MIS Q. 2013;37(2):655–662. https://misq.umn.edu/visions-and-voices-on-emerging-challenges-in-digital-business-strategy.html Retrieved April 4, 2022, from. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyytinen K., Yoo Y., Boland R.J., Jr. Digital product innovation within four classes of innovation networks. Inf. Syst. J. 2016;26(1):47–75. doi: 10.1111/isj.12093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y.-Y.K., Jaw Y.-L., Wu B.-L. Effect of digital transformation on organisational performance of SMEs. Internet Res. 2016;26(1):186–212. doi: 10.1108/IntR-12-2013-0265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.González-Varona J.M., López-Paredes A., Poza D., Acebes F. Building and development of an organizational competence for digital transformation in SMEs. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2021;14(1):15–24. doi: 10.3926/jiem.3279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troise C., Corvello V., Ghobadian A., O'Regan N. How can SMEs successfully navigate VUCA environment: the role of agility in the digital transformation era. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2022;174 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfister P., Lehmann C. Returns on digitisation in SMEs – a systematic literature review. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2021 doi: 10.1080/08276331.2021.1980680. In Press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denicolai S., Zucchella A., Magnani G. Internationalization, digitalization, and sustainability: are SMEs ready? A survey on synergies and substituting effects among growth paths. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2021;166 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira G.V., Estevez E., Cardona D., Chesñevar C., Collazzo-Yelpo P., Cunha M.A., Diniz E.H., Ferraresi A.A., Fischer F.M., Garcia F.C.O., Joia L.A., Luciano E.M., Albuquerque J.P., Quandt C.O., Rios R.S., Sánchez A., Silva E.D., Silva-Junior J.S., Scholz R.W. South American expert roundtable: increasing adaptive governance capacity for coping with unintended side effects of digital transformation. Sustainability. 2020;12(2):718. doi: 10.3390/su12020718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Bank, World Bank SME Finance . 2022. Development News, Research, Data.https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance Retrieved August 1, 2022, from. [Google Scholar]

- 10.North K., Aramburu N., Lorenzo O.J. Promoting digitally enabled growth in SMEs: a framework proposal. J. Enterprise Inf. Manag. 2019;33(1):238–262. doi: 10.1108/JEIM-04-2019-0103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.OECD . 2017. Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2017. Retrieved. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elkington J. Towards the sustainable corporation: win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994;36(2):90–100. doi: 10.2307/41165746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Culot G., Nassimbeni G., Orzes G., Sartor M. Behind the definition of Industry 4.0: analysis and open questions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020;226 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira M.R., Sousa T.B., Silva C.V., Silva F.A., Costa P.H.K. Supply Chain Management 4.0: perspectives and insights from a bibliometric analysis and literature review. World Rev. Intermodal Transp. Res. 2022;11(1):70–107. doi: 10.1504/WRITR.2022.123099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verhoef P.C., Broekhuizen T., Bart Y., Bhattacharya A., Dong J.Q., Fabian N., Haenlein M. Digital transformation: a multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021;122:889–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]