Graphical abstract

Keywords: Docosahexaenoic acid, Hippocampus, Insulin resistance, Cognitive function, High-fat diet, Aging

Highlights

-

•

DHA improves systemic glucose metabolism disorders.

-

•

DHA prevents hippocampal neuroinflammation.

-

•

DHA attenuates hippocampal oxidative stress.

-

•

DHA inhibits hippocampal amyloid formation and Tau phosphorylation.

-

•

DHA ameliorates hippocampal insulin resistance.

-

•

DHA improves cognitive function.

Abstract

Introduction

Diminished brain insulin sensitivity is associated with reduced cognitive function. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is known to maintain normal brain function.

Objectives

This study aimed to determine whether DHA impacts hippocampal insulin sensitivity and cognitive function in aged rats fed a high-fat diet (HFD).

Methods

Eight-month-old female Sprague-Dawley rats were randomly divided into three groups (n = 50 each). Rats in the aged group, HFD group, and DHA treatment group received standard diet (10 kcal% fat), HFD (45 kcal% fat), and DHA-enriched HFD (45 kcal% fat, 1% DHA, W/W) for 10 months, respectively. Four-month-old female rats (n = 40) that received a standard diet served as young controls. Neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, amyloid formation, and tau phosphorylation in the hippocampus, as well as systemic glucose homeostasis and cognitive function, were tested.

Results

DHA treatment relieved a block in the insulin signaling pathway and consequently protected aged rats against HFD-induced hippocampal insulin resistance. The beneficial effects were explained by a DHA-induced decrease in systemic glucose homeostasis dysregulation, hippocampal neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. In addition, DHA treatment broke the reciprocal cycle of hippocampal insulin resistance, Aβ burden, and tau hyperphosphorylation. Importantly, treatment of model rats with DHA significantly increased their cognitive capacity, as evidenced by their increased hippocampal-dependent learning and memory, restored neuron morphology, enhanced cholinergic activity, and activated cyclic AMP-response element-binding protein.

Conclusion

DHA improves cognitive function by enhancing hippocampal insulin sensitivity.

Introduction

Aging is often accompanied by general deleterious physiological changes, such as loss of muscle mass, fat accumulation, and insulin resistance. In the central nervous system (CNS), aging is associated with progressive cognitive functional decline, which is exacerbated in many neurodegenerative disorders, including mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1], [2].

High fat consumption is an important characteristic of the Western-style diet. High-fat diet (HFD)-induced metabolic abnormalities are the major origins of several physiological dysfunctions, including type 2 diabetes (T2DM) [3], nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [4], cardiovascular disease [5], [6], and cancer [7]. Likewise, a HFD also alters the cerebral metabolic and bioenergetic function [8], [9] and exacerbates brain aging and cognitive decline [10]. With the aging of the global population, the combined effects of aging and HFD in the elderly facilitate the development of age-related cognitive decline. Chronic neuroinflammation and oxidative stress are thought to be two key contributors to this process [10].

The brain is an insulin-sensitive organ [11]. Insulin receptors are abundantly expressed on all cell types and widely distributed throughout the brain, including the hippocampus, hypothalamus, and cortex [12], [13]. Within the brain, insulin binds to its receptors to initiate a complex signaling cascade and specifically modulates multiple brain functions [13]. Indeed, compromised brain insulin signaling, that is, brain insulin resistance, is a shared pathological mechanism of metabolic and cognitive disorders [11]. Recent studies have indicated that brain insulin resistance leads to cognitive dysfunctions, including learning and memory deficits [11], [14], [15], [16]. On the contrary, bolstering brain insulin signaling improves learning and memory ability [17], [18]. Additionally, overnutrition can rapidly induce brain insulin resistance even before peripheral insulin signaling is impaired [19]. Furthermore, a long-term HFD induces severe brain insulin resistance [14], resulting in multifaceted effects on metabolism, aging, and cognitive function [11]. Mechanistically, multiple causative factors contribute to the pathogenesis of brain insulin resistance, including oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [20].

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, C22:6n-3) is the most abundant omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) in the brain. Previous findings have suggested that DHA helps to maintain brain function. For example, poor omega-3 PUFA status is associated with autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [21]. Moreover, DHA supplementation exerts favorable effects on depression and cognitive function by impacting inflammatory processes, neurotransmitter activities, and cell communication [22], [23]. In line with this, a decrease in brain DHA has been shown to result in impaired cognitive ability [24], [25]. However, enriching diets with DHA can improve age-related cognitive decline [26], [27]. Multiple mechanisms have been revealed to underlie DHA functions in the brain, including synaptic effects, neurogenesis, neuroprotection, regulation of brain glucose uptake, and anti-inflammation [25]. Additionally, animal studies have shown that DHA supplementation protects against peripheral insulin resistance [28], [29], [30]. However, little is known about the efficacy of DHA as an insulin sensitizer in the brain.

To address this question, we studied hippocampal insulin signaling changes in relation to DHA supplement in chronically HFD-fed rats—a model of brain insulin resistance. Subsequently, we explored the mechanism of action by assessing systemic glucose homeostasis, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, amyloid formation, and tau phosphorylation in hippocampus. In addition, we examined how the cognitive function was affected in this study.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All experiments involving animals were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Wuhan University of Science and Technology, China (Approval no. WUST-19026).

Animal maintenance

Female, 8-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Vital River Laboratory Animal Center (Beijing, China). The animals were housed individually in clear plastic cages and maintained under standard laboratory conditions (temperature 24 ± 1 °C, 12–12-h dark-light circle, and humidity 45%–65%) and received food and water ad libitum. A veterinarian conducted routine health checks weekly, and those animals with chronic respiratory disease, infection, or a tumor were excluded from this study.

Diet preparation

The standard diet (10 kcal% fat) and HFD (45 kcal% fat) were prepared with D12450B (Research Diets) and D12451 (Research Diets) formulations. DHA was supplied as algae oil microcapsules (Cabio Biotech Co. Ltd., Wuhan, China) to minimize possible lipid oxidation and odor. The DHA-enriched HFD (45 kcal% fat, 1% DHA, W/W) was made using the D12451 (Research Diets) formulation but with partial replacement of lipid with algae oil. The diets were packed and sealed into plastic bags, evacuated using a vacuum pump, and stored at –20 °C. The composition of the diets is provided in Tables S1 and S2.

Study design

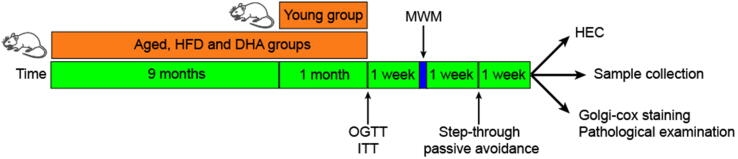

The animals were randomly divided into three groups (n = 50). Rats in the aged group (Aged), high-fat diet group (HFD), and DHA treatment group (DHA) received the standard diet, HFD, and DHA-enriched HFD, respectively. When the rats were 17 months of age, 40 additional 3-month-old female rats that were purchased from the same vendor and received the standard diet were included in the study as young controls (Young). When the aged animals reached 18 months of age, 26 rats (7 in Aged, 11 in HFD, and 8 in DHA) were excluded on the basis of the aforementioned criteria or death. Animals from each group were randomly assigned to receive either an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) (n = 10) or insulin tolerance test (ITT) (n = 10). After 1 week, we performed the Morris water-maze (MWM) and step-through passive avoidance tests at weekly intervals. Seven days later, the animals in each group were randomized and divided into three subgroups. Five rats underwent a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp (HEC) experiments; another 10 were anesthetized with isoflurane for Golgi-cox staining (n = 5) and pathological examination (n = 5); and the remaining rats were fasted for 12 h and anesthetized using isoflurane prior to blood collection by cardiac puncture and hippocampal dissection. A schematic diagram of the study design is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the study design.

Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and insulin tolerance test (ITT)

For the OGTT, animals were administered 40% D-glucose (2.0 g/kg BW; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) via oral gavage after 12-h fasting. For the ITT, rats were intraperitoneally injected with insulin (0.75 IU/kg BW; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) after 12-h fasting. Blood samples were obtained from tail veins at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after the OGTT or ITT, and glucose concentrations in the blood were determined with Accu-Chek blood glucose monitor (Roche, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany).

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp (HEC) experiments

HEC experiments were performed following the reported procedure [31]. Briefly, animals were fasted overnight for 12 h and infused with insulin (4 mU/kg/min; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) via the jugular cannula for 120 min. By adjusting the glucose infusion, plasma glucose concentrations were maintained at basal fasting levels. The glucose infusion rates (GIRs) were calculated as the mean of steady-state glucose infusion rates during the final 30 min. The hippocampi were quickly isolated from the animals 10 min after euthanasia. The rats used in the HEC experiments were deemed to undergo additional insulin stimulation.

Morris water-maze (MWM) test

The MWM test was performed as previously described [32]; all testing was performed using a water-maze pool (diameter: 150 cm, height: 50 cm) filled with water (22 ± 1 °C). Briefly, rats were allowed to pre-train for 2 days to acclimatize to the novel environment. During training trials, the hidden platform was placed 1 cm beneath the water and animals were given 60 s to search for the hidden platform. Each animal was subjected to different starting quadrants to perform three trial sessions daily. The platform was placed at the same location throughout the five consecutive training days. Twenty-four hours later, the platform was removed for a probe trial. The time that the animals spent to swim in the target quadrant (where the platform used to be) within 60 s was measured. The swimming behavior of the rats was automatically recorded by ANY-maze software (version 4.82). Taking into account the significant swimming-speed disparity among groups in the MWM, the swimming distance and cumulative search error during training trials and the amount of time spent swimming in the target quadrant during the probe trial were applied to assess the spatial cognitive abilities.

Passive avoidance test

Passive avoidance test was conducted in the Shuttle-box system (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA), as described previously [33]. The apparatus was equipped with a grid floor and consisted of two chambers (light and dark) separated by an automated gate. For the training trial, an animal was placed in the light chamber and allowed to explore freely. After 30 s, the animals were allowed access to the dark chamber through the gate. When the rat fully entered the dark chamber, the gate closed and the animal received a shock (0.6 mA, 3 s). The rat was then returned to the home cage. Twenty-four hours later, a test trial was performed by returning the rat to the light chamber. The time taken for the rat to enter the dark chamber was recorded as the step-through latency. A maximum latency of 300 s was given to the rat.

Capillary-based immunoassay

Hippocampi were lysed with RIPA buffer (Beyotime, China) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Roche, Germany). After centrifugation, 4 parts of lysate and 1 part of 5 × Fluorescent Master Mix were mixed and denatured. The sample was loaded into the assay plates, and the protein electrophoresis and immunodetection were realized on an automated capillary electrophoresis Western platform (WES, ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA), for which Wes Separation Capillary Cartridges of 12–230 kDa and 2–40 kDa were used. The proteins were visualized, quantified and analyzed with Compass software (version 3.1.8, ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA). All antibodies used in this study are listed in Table S3.

Golgi-cox staining

Golgi-cox staining was completed with the FD rapid Golgi staining kit (FD NeuroTechnologies, MD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, animals were anesthetized and perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. The brains were then dissected and stained following the manufacturer’s instructions. The slices were cut into a thickness of 200 μm with a Vibratome (Leica). Images of the hippocampi, neurons, and dendritic spines were acquired at × 20, × 400, and × 700 magnifications.

Immunofluorescence assays

Animals were anesthetized and perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. The brains were then dissected and cut into serial coronal sections. Fixed brain sections were stained overnight with specific primary antibodies at 4 °C, washed in TBST, and then incubated with fluorescent dyes at room temperature. Samples were incubated in DAPI solution to detect nuclei and then coverslipped. Immunofluorescence images were taken with a 3D Histech Panoramic 250 Flash II scanner (3DHISTECH, Budapest, Hungary). Image analysis was performed using NIH ImageJ software. The antibodies used are listed in Table S3.

Biochemical assays

The 10% homogenate hippocampus tissues were prepared with PBS and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected for biochemical assays. Protein concentration was assayed with a BCA protein concentration kit (Thermo Scientific, USA).

SOD activity was determined using the water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST-1). Briefly, 20 μl of the supernatant was incubated with Tris–HCl (pH 8), diethylene-triamine-penta-acetic acid (100 μM), hypoxanthine (100 μM), WST-1 (180 μM), and xanthine oxidase (240 mU /ml) at 37 °C for 20 min. Then, absorbance was recorded at 450 nm.

Catalase (CAT) activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 240 nm monitoring the decomposition of H2O2. Briefly, 15 μl of the supernatant was added to the assay mixture containing potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0) and hydrogen peroxide (10 mM). Changes in absorbance were monitored at 240 nm.

For glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity assessment, 20 μl of the supernatant was mixed with the reaction mixture which contained Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM, pH 8.5), a 4.8 mM solution of reduced glutathione GSH (4.8 mM), tert-butyl hydroperoxide (20 mM), trichloroacetic acid (20%), and Elman reagent (100 mM). The intensity of the color of control and samples was recorded at 412 nm against the blank.

For GSH concentration determination, 50 μl of the supernatant was mixed with 200 μl of trichloroacetic acid buffer and then centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min. The resulting supernatant was collected. Total GSH was measured by examining the change in absorbance at 412 nm in a reaction mixture containing final concentrations of 0.2 mM NADPH, 0.6 mM DTNB, 10 mg/ml GSH reductase, and the resulting supernatant supernatant.

ELISA measurements

We used ELISA kits to detect plasma insulin levels and hippocampal concentrations of Aβ40, Aβ42, TNF-α, and 8-isoprostane according to the manufacturers’ instructions. All ELISA kits used in this study are listed in Tables S4.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Groups were compared with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey post hoc tests (equal variances) or Dunnett’s T3 post-test (unequal variances). Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc tests was used for statistical analysis of training trials in the MWM, OGTT, ITT, and tests to examine the phosphorylation levels of Akt and GSK3β. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 13.0). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

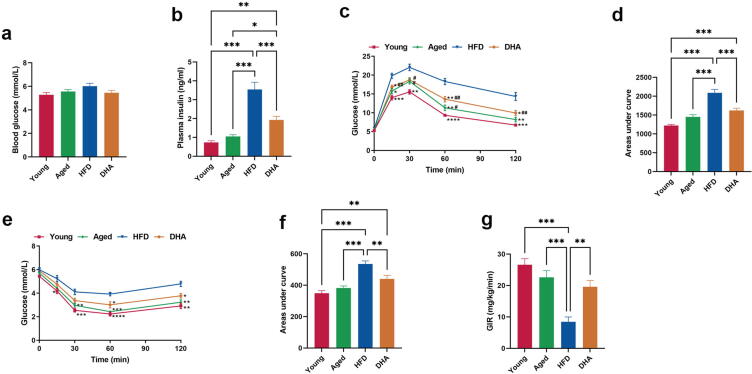

Improved systemic glucose homeostasis in DHA-treated rats

Blood glucose concentrations in fasting HFD-fed aged rats did not markedly differ from those in the Young and Aged animals (Fig. 2a), although this requires more than 4-fold higher plasma insulin levels (Fig. 2b), suggesting the presence of insulin resistance. However, DHA-treated aged rats showed reduced plasma insulin levels when compared with HFD-fed aged animals (Fig. 2b). To further assess the effect of DHA on systemic glucose homeostasis, we conducted two tests, the OGTT and the ITT. Compared to the Young and Aged animals, the HFD-fed aged rats had delayed glucose clearance (Fig. 2c–d) and reduced response to insulin (Fig. 2e–f). With DHA supplementation, these rats exhibited a marked improvement in glucose tolerance and insulin tolerance (Fig. 2c–f). Furthermore, during euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp studies, the GIR required to maintain euglycemia was remarkably lower in the HFD-fed aged animals than in the Young and Aged rats, and DHA treatment restored the GIR to levels comparable to that of standard-fed aged animals (Fig. 2g). Taken together, these results revealed that chronic DHA supplementation protected aged rats against HFD-induced systemic insulin resistance.

Fig. 2.

DHA improves HFD-induced systemic glucose metabolism disorders in aged rats. (a) Blood glucose levels in rats after fasting for 12 h (n = 10/group). (b) Plasma insulin levels in rats after fasting for 12 h (n = 10/group). Nonparametric Dunnett’s T3 test for multiple comparisons. (c) Results of the OGTT (n = 10/group). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 compared to young animals; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared to HFD-fed animals. (d) The area under the curve of the OGTT. (e) Results of the ITT (n = 10/group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared to HFD-fed animals. (f) The area under the curve of the ITT. (g) The average overall GIR during the final 30 min of the HEC experiment (n = 5/group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m.

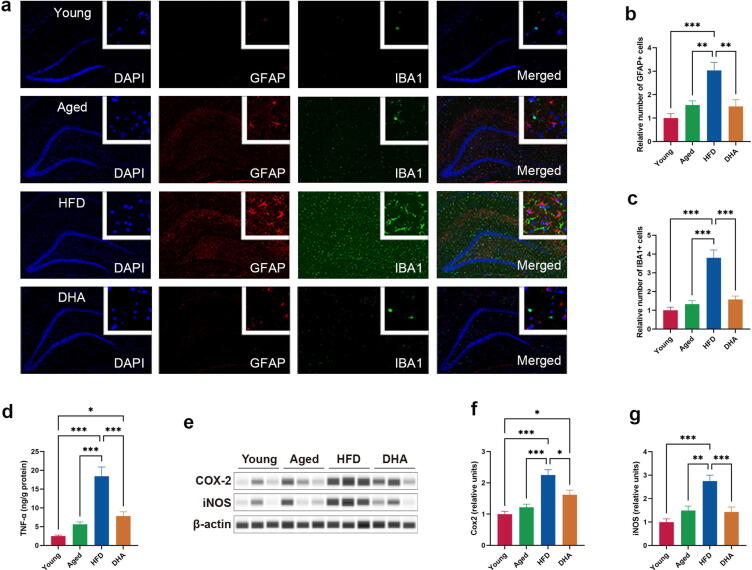

DHA prevents hippocampal neuroinflammation

To evaluate hippocampal immune responses, we performed double label immunostaining analysis for GFAP, a marker for reactive astrocytes, and IBA1, a marker for macrophage and microglial activation. Indeed, we found significantly increased numbers of GFAP- and IBA1-positive cells in the hippocampus of HFD-fed aged rats compared to Young and Aged animals (Fig. 3a–c). DHA treatment clearly decreased the number of GFAP- and IBA1-positive cells (Fig. 3a–c), suggesting a suppressing efficacy of hippocampal immune cell activation. Activated microglia secrete potent proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α; consistently, we found that the hippocampal concentration of TNF-α had the same alteration pattern as the hippocampal activation state of immune cells (Fig. 3d). In addition, DHA treatment also significantly reduced the chronic HFD-induced increase in iNOS (Fig. 3f) and COX-2 (Fig. 3g), two key proinflammatory mediators of aging hippocampi.

Fig. 3.

DHA improves HFD-induced neuroinflammation in hippocampus of aged rats. (a) Micrographs depict immunofluorescent labeling for GFAP and IBA1 (red: GFAP, green: IBA1). The nucleus was identified by DAPI staining (blue). (b) The relative number of GFAP-positive astrocytes. (c) The relative number of IBA1-positive microglia. (d) Hippocampal TNF-α levels of rats (n = 8/group). Nonparametric Dunnett’s T3 test for multiple comparisons. (e–g) Capillary-based immunoassays for COX-2 and iNOS proteins in the hippocampus of rats; β-actin served as the loading control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

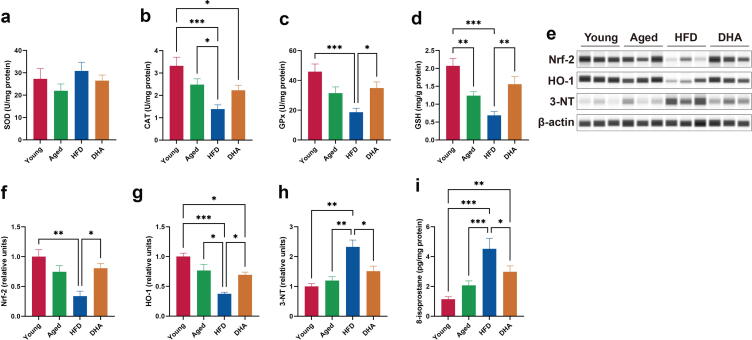

DHA attenuates hippocampal oxidative stress

To ascertain the antioxidant status of the hippocampus, we first investigated whether the antioxidant capacity was altered. Although no difference in hippocampal SOD activity among the groups existed (Fig. 4a), we found that the activity of the antioxidant enzymes CAT and GPx, as well as the content of GSH in the hippocampus, tended to decrease with age (Fig. 4b–d). The decreased antioxidant capacity was further worsened following HFD exposure, whereas DHA treatment restored the activity of GPx and led to higher concentrations of hippocampal GSH (Fig. 4b–d). To investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the hippocampal antioxidant effects on rats with DHA treatment, we next examined the expression of Nrf-2. When compared with young rats, Nrf-2 protein was decreased in the HFD-fed aged rats (Fig. 4e and f). DHA treatment significantly recovered Nrf-2 expression similar to the level in Aged rats (Fig. 4e and f). In addition, the changing pattern of HO-1 protein levels, an antioxidant Nrf-2 target gene product, was similar to that of Nrf-2 in all the groups (Fig. 4e and g). In addition, hippocampi from HFD-fed aged animals showed significantly elevated levels of oxidative stress markers, 3-NT and 8-isoprostan, which were reversed by chronic DHA supplementation (Fig. 4e and h–i). These results demonstrated that DHA offers efficient protection against oxidative damage to the hippocampus.

Fig. 4.

DHA improves HFD-induced oxidative stress in hippocampus of aged rats. (a–c) SOD (a), CAT (b), and GPx (c) activities (n = 8/group). (d) GSH levels (n = 8/group). (e–h) Capillary-based immunoassays for Nrf-2, HO-1, and 3-NT in the hippocampus of rats; β-actin served as the loading control. (i) 8-isoprostane levels in the hippocampus of rats (n = 8/group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m.

DHA inhibits hippocampal amyloid formation and tau phosphorylation

We found that the hippocampal APP level increased in HFD-fed aged rats, irrespective of whether the rats were fed HFD or HFD with DHA supplement (Fig. 5a–b). Notably, we observed higher protein expression of hippocampal BACE in the HFD-fed aged rats than in the Young and Aged animals (Fig. 5a and c), and, consistently, hippocampal Aβ contents of HFD-fed aged rats were also markedly elevated than those of Young and Aged animals (Fig. 5d–e). In addition, DHA treatment coordinately reversed the HFD-induced increase in BACE expression and plaque loads of hippocampus (Fig. 5a and c–e). Moreover, HFD feeding markedly increased the levels of hippocampal tau phosphorylation, which was largely attenuated by DHA treatment (Fig. 5f–g). Cumulatively, these results suggested that DHA protects against the neurotoxic effects of Aβ and phosphorylated tau in the hippocampi of aged animals.

Fig. 5.

DHA improves HFD-induced amyloid formation and tau phosphorylation in hippocampus of aged rats. (a–c) Capillary-based immunoassays for APP and BACE1 proteins in the hippocampus of rats; β-actin served as the loading control. (d–e) Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels (n = 8/group). Nonparametric Dunnett’s T3 test for multiple comparisons. (f–g) Capillary-based immunoassays for p-tau (Ser396) and total tau proteins in the hippocampus of rats. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m.

Ameliorated hippocampal insulin sensitivity in DHA-treated rats

IRS-1 inactivation has emerged as a key event in insulin resistance. We first examined whether DHA is effective at regulating IRS-1 activation. HFD-fed aged rats showed significantly increased hippocampal IRS-1 phosphorylation at Ser612, Ser636/639, and Ser1101 compared to the Young and Aged rats (Fig. 6a–d), indicating the inactivation of IRS-1 under HFD conditions, and this defective IRS-1 activity was reversed by DHA supplementation (Fig. 6a–d). Indeed, many kinases can cause serine-phosphorylation of IRS-1 [15]. Thus, we investigated whether the IRS-1 inactivation was a result of kinase activation. We found that HFD-fed aged animals had substantially increased phosphorylation in hippocampal JNK and IKK (Fig. 6e–g). Strikingly, DHA treatment potently blocked the aberrant phosphorylation of JNK and IKK and thus suppressed their activities (Fig. 6e–g). To further determine the hippocampal insulin sensitivity, we tested the changes in the phosphorylation states of Akt and its downstream effector GSK3β following insulin stimulation. We found that HFD-fed aged animals had significantly elevated basal phosphorylation levels of hippocampal Akt and GSK3β (Fig. 6h–j). Unlike the Young and Aged animals, the HFD-fed aged rats lost additional phosphorylation of Akt and GSK3β in response to insulin (Fig. 6h–j), suggesting a block of insulin signaling. Conversely, DHA-treated animals had substantially increased phosphorylation levels of Akt and GSK3β following insulin stimulation (Fig. 6h–j). Altogether, our data demonstrate the ability of DHA to improve insulin resistance in the hippocampus of HFD-fed aged rats.

Fig. 6.

DHA improves HFD-induced insulin resistance in hippocampus of aged rats. (a–d) Capillary-based immunoassays for p-IRS-1 (Ser612), p-IRS-1 (Ser1101), p-IRS-1 (Ser636/639), and total IRS-1 proteins in the hippocampus of rats. (e–g) Capillary-based immunoassays for p-IKKα/β(Ser176/180), IKKα, IKKβ, p-JNK(Thr183/Tyr185), and total JNK proteins in the hippocampus of rats. (h–j) Capillary-based immunoassays for p-AKT (Ser473), total AKT, p-GSK-3β (Ser9), and total GSK-3β proteins without or with insulin treatment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m.

DHA improves cognitive function

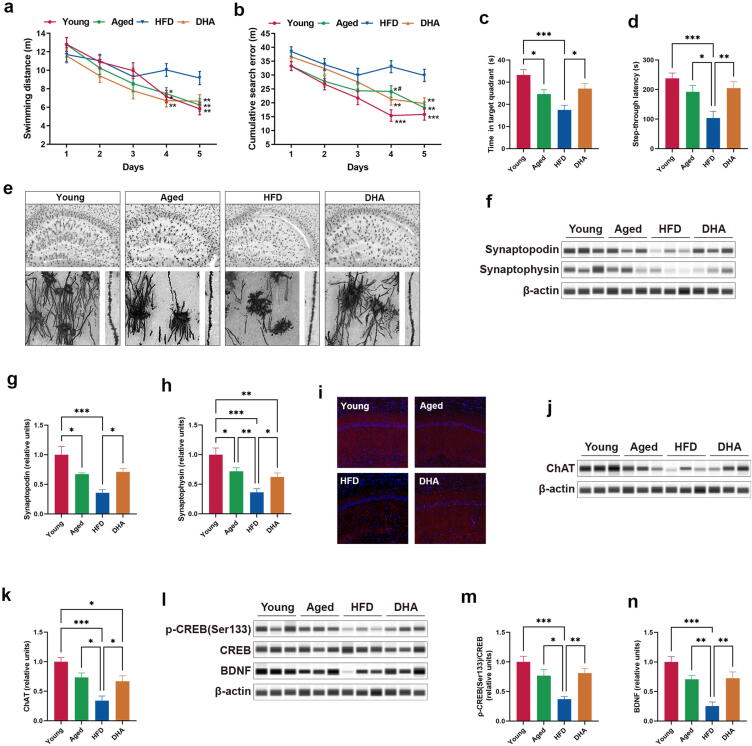

To determine the effects of DHA on cognitive function, we subjected animals to the MWM and passive avoidance tests to evaluate hippocampus-dependent spatial and contextual memory. For the MWM, although there were no meaningful differences in swimming distance between the Young and Aged rats (Fig. 7a), the aged rats demonstrated a significantly increased cumulative search error on day 4 in training trials, as well as a substantially reduced time in the target quadrant in the probe trial (Fig. 7b–c), suggesting modest deficits in spatial learning and memory. Furthermore, the HFD-fed aged rats showed considerable cognitive impairment, as evidenced by the fact that the HFD-fed aged rats remarkably differed from the Young or Aged animals on both measures of place learning and memory on days 4 and 5 in the training trials, including swimming distance and cumulative search error, and on the time in the target quadrant in the probe trial (Fig. 7a–c). DHA-treated animals had significantly improved spatial cognitive function on all three measures of MWM performance compared to the HFD-fed aged rats (Fig. 7a–c). For the passive avoidance test, aged rats had a tendency, albeit not significant, toward reduced latency to enter the dark chamber where they had received a shock, whereas the HFD-fed aged rats showed a remarkable shorter latency than rats from the Young and Aged groups (Fig. 7d). This exaggerated contextual memory was restored to the levels of normal aging in the DHA-treated aged rats, demonstrating that DHA corrected the loss of contextual memory. These findings suggest that DHA improves hippocampal-dependent cognitive deficits in aged rats on a chronic HFD.

Fig. 7.

DHA improves HFD-induced cognitive impairment in aged rats. (a–b) Swimming distance and cumulative search error during MWM training trials (n = 16–18). Statistics according to two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs. (c) Time spent in the target quadrant in the MWM probe test (n = 16–18). (d) Entry latency in the passive avoidance test (n = 20). (e) Upper panel: representative micrographs of Golgi-Cox-stained coronal sections of the hippocampus. Lower left panel: representative higher resolution micrographs of Golgi-Cox-stained neurons. Lower right panel: representative micrographs of Golgi-Cox-stained dendrites from CA1 pyramidal neurons. (f–h) Capillary-based immunoassays for synaptopodin and synaptophysin proteins in the hippocampus of rats; β-actin served as the loading control. (i) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining for ChAT (red) and DAPI (blue). (j–k) Capillary-based immunoassays for ChAT protein in the hippocampus of rats; β-actin served as the loading control. (l–n) Capillary-based immunoassays for p-CREB (Ser133), total CREB, and BDNF proteins in the hippocampus of rats; β-actin served as the loading control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. All data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We then performed Golgi staining to visualize the neuronal morphology. We found less neurons and a relatively poor neuronal morphology in the hippocampus under aging conditions, and HFD further promoted these alterations, including reduced neuronal number, less dendritic branching, decreased branch length, decreased complexity of neuronal dendritic trees, and decreased dendritic spine density (Fig. 7e). Of note, DHA treatment resulted in a substantial improvement in neuronal morphology (Fig. 7e). Accordingly, DHA restored the level of hippocampal synaptopodin, a marker of spines, which was decreased in HFD-fed aged rats (Fig. 7f–g). Given that the dendritic spine is a primary cellular site for the formation of synaptic junctions [34], we then examined the change of synapse density. We found that the immunoreactivity of hippocampal synaptophysin, a key synaptic protein, was decreased in HFD-fed aged animals, and DHA treatment produced a significant elevation in synaptophysin level (Fig. 7f and h).

We next characterized the effects of aging and diet on cholinergic neurons. Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-positive neurons, detected by immunofluorescence, were markedly sparser in the hippocampal CA1 region of HFD-fed aged animals than those in Young or Aged animals, and DHA treatment induced a large density increase in those neurons (Fig. 7i). The results of capillary-based immunoassay also followed a similar pattern (Fig. 7j–k).

Finally, HFD-fed aged animals exhibited a significant decrease in hippocampal CREB activation by preventing its phosphorylation (Fig. 7l–m). As BDNF expression is a direct readout of CREB activity [35], it is reasonable to observe the substantive loss of the hippocampal BDNF protein expression in HFD-fed aged rats (Fig. 7l and n). In addition, DHA treatment remarkably activated CREB, with increasing protein expression of BDNF (Fig. 7l and n).

Discussion

The brain is a key insulin-sensitive organ in which insulin mediates numerous neuronal functions. Numerous studies have indicated memory-improving effects of insulin [36], [37], and insulin action in the brain is progressively impaired during AD-type neurodegeneration [17], [20]. Compromised brain insulin signaling exacerbates Aβ accumulation and tau hyperphosphorylation, two critical signatures in AD-type neurodegeneration pathology [20], [38]. Therefore, brain insulin resistance participates in the core mechanism of AD-type neurodegeneration.

Accumulating evidence has demonstrated a strong association between AD, which is characterized by progressive cognitive dysfunction, and T2DM. Brain insulin resistance can certainly be considered at the crossroads of these two diseases [11], and chronic peripheral insulin elevation is accompanied by reduced brain insulin activity [39]. Furthermore, brain insulin sensitivity progressively decreases from cognitively normal to MCI and AD, making brain insulin resistance a common feature of AD-type neurodegeneration [15], [40]. In this study, we found that chronic HFD feeding specifically impinged on systemic glucose metabolism and induced pronounced peripheral insulin resistance, corroborated by the results of the OGTT, ITT, and euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp test. As a result, subsequent metabolic and vascular disturbances may directly affect the brain [20], [41]. Expectedly, HFD feeding also led to blockade of the insulin-dependent IRS1-PI3k-Akt-GSK3β signaling pathway in the hippocampus. Suppressed IRS-1 activation via several serine sites of phosphorylation was found, and phosphorylation of these sites resulted from a feed-forward inhibition exerted by JNK and IKK. In addition, AKT and GSK3β, which are key kinases in the insulin signaling pathway, remained in marginal hyperphosphorylation and lost their responsiveness to insulin upon HFD feeding. In particular, GSK3β is a hub of cell signaling, and dysfunctional GSK3β fosters numerous pathological processes in the neurodegenerative brain, including cholinergic neuronal and synaptic loss, Aβ accumulation, tau hyperphosphorylation, and neuroinflammation [38], [42]. In conclusion, our data delineate the IRS1-AKT-GSK3β pathway as a key signaling axis in the pathogenesis of hippocampal insulin resistance.

Previous work has established the importance of DHA in the modulation of peripheral insulin sensitivity, showing that DHA leads to diminished peripheral insulin resistance [30], [43]. The same conclusion was reached in this study, which accounts for the restoration of peripheral glucose and insulin levels in animals with DHA supplementation. The improved peripheral insulin sensitivity was associated with a reduction in vascular inflammation and Aβ accumulation, as well as activation of insulin-degrading enzyme in the brain [20], [44]. These salutary effects may underlie the efficacy of DHA to attenuate HFD-induced memory impairments. Largely owing to the recovery of IKK and JNK from abnormal kinase activation, which reduces the serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, the hippocampal insulin signaling pathway restored sensitivity to insulin with DHA supplementation. This normalization of the IRS1-PI3k-Akt-GSK3β cascade led to the recovery of many downstream effects, including cognitive ability [13], [15].

Oxidative stress is a common driving force in age-related neurodegenerative disease and T2DM pathogenesis [45]. Indeed, oxidative stress is both a cause and a consequence of brain aging [46]. In this study, we found that the combined effects of aging and HFD in the hippocampus resulted in the highest level of oxidative stress due to impairment of antioxidant systems, which modify various cell components, including lipids, proteins, and DNA, and consequently inhibit their functions. There are multiple mechanisms whereby oxidative stress induces insulin resistance and AD. In conditions of oxidative stress, activated IKK and JNK induce IRS1 serine phosphorylation and degradation and further impair cellular redistribution of insulin-signaling components [47], [48]. Oxidative stress is also capable of triggering inflammatory response [49] and potentiating BACE gene expression and Aβ generation [50]. Theoretically, DHA itself enhances oxidative stress because of the increased likelihood of lipid peroxidation, particularly under hyperglycemic conditions. However, researchers have reported reduced levels of oxidative stress in the hippocampus with DHA supplementation [51]. Here, we showed that DHA activated Nrf-2 as well as its downstream antioxidant proteins, including HO-1, CAT, and GPX, to inhibit hippocampal oxidative damage. Corroborating these findings is a recent study, which demonstrated that DHA provides endogenous antioxidative defense coordinated by Nrf-2 against oxidative stress [52].

Chronic neuroinflammation is a major contributor to neurodegeneration and is also another shared mechanism between T2DM and AD. In the CNS, neuroinflammatory responses are often propagated by the activation of microglia and astrocytes [53], [54]. Admittedly, during aging, glial cells are more sensitive to immune stimulus and have reduced ability to restore homeostasis [55], [56], [57]. In addition, a striking adverse property of HFD is its ability to trigger neuroinflammation [58], [59]. Here, we demonstrated that aging glial cells undergo remarkable inflammatory changes as a result of HFD feeding, as described earlier [60], [61]. Activated glial cells result in further proinflammatory responses, including the expression of iNOS and COX-2, and release of a wide range of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and TNF-α. These cytokines can establish a feedback loop to activate more glial cells, resulting in further exacerbation of neuroinflammation [62]. Increased neuroinflammation blocks hippocampal insulin signaling by increasing IRS-1 serine phosphorylation [17]. In addition, persistent glia-mediated neuroinflammation contributes to oxidative stress by multiple mechanisms [63], which together create a neurotoxic environment that favors Aβ formation and tau hyperphosphorylation. Additionally, neuroinflammation accelerates the spread of pathological tau in anatomically connected regions of the hippocampus [64]. In this study, DHA treatment induced striking reactive downregulation of glial cells and also reduced the levels of TNF-α, iNOS, and COX-2, which protected the hippocampus from inflammatory insult in HFD-fed aged rats. This effect is consistent with the observed positive relationship between DHA supplementation and neuroinflammation [65]. Mechanistically, recent studies have suggested that DHA facilitates the polarization of glial cells into an anti-inflammatory phenotype [66]. Further, DHA can be metabolized by metabolic enzymes (such as lipoxygenases and cyclooxygenase) with resultant diverse pathway-specific bioactive metabolites [67], [68]. Many DHA derivatives (such as resolvins, protectins, and maresins) play significant anti-neuroinflammatory roles [65], [67], [68], which explains the resolution of neuroinflammation observed in the present study.

Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) of hyperphosphorylated tau protein are hallmark features of AD pathology and are also considered the major pathogenic culprits for neurodegeneration. Abnormal aggregation of Aβ in AD instigates different facets of AD neuropathology, such as synapse loss, tau hyperphosphorylation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and nerve cell-specific death [69]. In particular, NFTs link to block neuronal signaling and neurotoxicity of Aβ [70], [71]. Indeed, cerebral β-amyloidosis occurs during normal aging, although without cognitive deficit [72], [73]. The increased cerebral Aβ may directly trigger tau hyperphosphorylation [74] and create a unique environment that will finally promote the recruitment of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins into NFTs [75]. Thus, early elevation in the phosphorylation of tau occurs before the onset of significant neurodegeneration [76]. In concordance with our previous studies [77], we observed that aging and HFD acted in concert to drive AD-like pathogenetic processes by the presence of Aβ accumulation and tau phosphorylation in abundance. However, the strong decrease in Aβ burden and tau hyperphosphorylation suggests that DHA may arrest AD-like pathologies’ progression. This is in line with previous findings, which demonstrated that dietary DHA ameliorates Aβ load and tau phosphorylation by various mechanisms [78], [79], [80], including reducing presenilin 1 levels and stimulating the activity of insulin-degrading enzyme, a major Aβ-degrading enzyme. Given that BACE is a rate-limiting enzyme for Aβ generation, the resulting decrease in BACE expression positions DHA as an effective inhibitor of Aβ production. Excessive GSK3 activity contributes to tau hyperphosphorylation and the generation of toxic Aβ [38], [42]. However, in our study, chronic HFD-fed aged mice demonstrated inactivated hippocampal GSK3β by hyperphosphorylation at serine residue 9 (Ser9) but increased Aβ burden and tau phosphorylation. Conversely, DHA abrogated the basal hyperphosphorylation of GSK3β, which was concomitant with reduced Aβ production and tau phosphorylation. Moreover, DHA restored the impaired insulin sensitivity in hippocampus of HFD-fed aged rats. Together, these findings confirmed that sensitization of insulin signaling pathway partners, including GSK3β, by DHA serves to inhibit AD-type pathology, including Aβ burden and tau phosphorylation.

Brain insulin resistance and AD-type pathology drive one another in a vicious cycle, which eventually results in neurodegeneration [20]. This allowed us to account for cognitive deficits in HFD-fed aged rats. Accordingly, we also found decreased hippocampal structural and synaptic plasticity in these animals. DHA treatment of HFD-fed rats led to substantial improvement in hippocampus-dependent memory and morphology of neurons, which provides substantial evidence for cognitive improvement. It is agreed that cholinergic function, which is essential for cognitive function, declined in aged and AD brains. Available evidence suggests that insulin signaling is required for the cholinergic system in the hippocampus, where it is colocalized with ChAT in cholinergic neurons [81]. Unsurprisingly, a previous study has confirmed that insulin signaling enhances ChAT expression in the brain [82]. Here, we show that further hippocampal cholinergic neuron loss in HFD-fed aged rats was reversed by DHA supplementation. This fact, combined with the observed contemporaneous reduction in hippocampal insulin resistance, leads us to conclude that insulin signaling, which was minimal in HFD-fed aged rats, is involved in the favorable effect of DHA on hippocampal cholinergic system. CREB and BDNF are key mediators of synaptic plasticity and memory formation [83], and reduced CREB activity and BDNF levels in hippocampus of HFD-fed aged animals have been demonstrated by our previous studies [32], [60], [84] as well as by our present findings. However, DHA treatment led to a robust increase in CREB activity and BDNF level in hippocampus. Both changes are probably particularly dependent on insulin signaling, given that CREB is found at a prime GSK3β target [38], [85] and is an upstream regulator of BDNF [83].

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that DHA improves the cognitive function of aged rats on an HFD by facilitating hippocampal insulin signaling. The effects of DHA on hippocampal insulin signaling are associated with a reduction in systemic glucose homeostasis dysregulation, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress. Furthermore, DHA also breaks the reciprocal cycle consisting of hippocampal insulin resistance, Aβ burden, and tau hyperphosphorylation. Our observations provide a possible understanding of maintaining cognitive function of DHA supplementation, and future studies are warranted to better understand the mechanisms in models that more closely match clinical application.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jiqu Xu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Ben Ni: Investigation. Congcong Ma: Methodology. Shuang Rong: Conceptualization. Hui Gao: Methodology. Li Zhang: Conceptualization. Xia Xiang: Methodology. Qingde Huang: Formal analysis. Qianchun Deng: Visualization, Validation. Fenghong Huang: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC-U21A20274), 3551 Optics Valley Talent Schema, Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-2016-OCRI), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA, and Tongji Hospital (HUST) Foundation for Excellent Young Scientist (2020YQ19).

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

All experiments involving animals were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Wuhan University of Science and Technology, China (Approval no. WUST-19026).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2022.04.015.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Small S.A., Schobel S.A., Buxton R.B., Witter M.P., Barnes C.A. A pathophysiological framework of hippocampal dysfunction in ageing and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(10):585–601. doi: 10.1038/nrn3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swerdlow R.H. Is aging part of Alzheimer's disease, or is Alzheimer's disease part of aging? Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28(10):1465–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajagopal R., Bligard G.W., Zhang S., Yin L., Lukasiewicz P., Semenkovich C.F. Functional Deficits Precede Structural Lesions in Mice With High-Fat Diet-Induced Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes. 2016;65:1072–1084. doi: 10.2337/db15-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao A., Kosters A., Mells J.E., Zhang W., Setchell K.D.R., Amanso A.M., et al. Inhibition of ileal bile acid uptake protects against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in high-fat diet–fed mice. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(357) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf4823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim S.H., Després J.-P., Koh K.K. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: friend or foe? Eur Heart J. 2016;37(48):3560–3568. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apovian C.M., Gokce N. Obesity and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2012;125(9):1178–1182. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.022541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolin K.Y., Carson K., Colditz G.A. Obesity and cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15:556–565. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raider K., Ma D., Harris J.L., Fuentes I., Rogers R.S., Wheatley J.L., et al. A high fat diet alters metabolic and bioenergetic function in the brain: A magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Neurochem Int. 2016;97:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langley M.R., Yoon H., Kim H.N., Choi C.-I., Simon W., Kleppe L., et al. High fat diet consumption results in mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and oligodendrocyte loss in the central nervous system. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(3):165630. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.165630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uranga R.M., Bruce-Keller A.J., Morrison C.D., Fernandez-Kim S.O., Ebenezer P.J., Zhang L.e., et al. Intersection between metabolic dysfunction, high fat diet consumption, and brain aging. J Neurochem. 2010;114(2):344–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kullmann S., Heni M., Hallschmid M., Fritsche A., Preissl H., Häring H.-U. Brain Insulin Resistance at the Crossroads of Metabolic and Cognitive Disorders in Humans. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(4):1169–1209. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kullmann S., Kleinridders A., Small D.M., Fritsche A., Häring H.-U., Preissl H., et al. Central nervous pathways of insulin action in the control of metabolism and food intake. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(6):524–534. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnold S.E., Arvanitakis Z., Macauley-Rambach S.L., Koenig A.M., Wang H.-Y., Ahima R.S., et al. Brain insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease: concepts and conundrums. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(3):168–181. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spinelli M., Fusco S., Mainardi M., Scala F., Natale F., Lapenta R., et al. Brain insulin resistance impairs hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory by increasing GluA1 palmitoylation through FoxO3a. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02221-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talbot K., Wang H.-Y., Kazi H., Han L.-Y., Bakshi K.P., Stucky A., et al. Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer's disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(4):1316–1338. doi: 10.1172/JCI59903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neves F.S., Marques P.T., Barros‑Aragão F., Nunes J.B., Venancio A.M., Cozachenco D., et al. Brain-Defective Insulin Signaling Is Associated to Late Cognitive Impairment in Post-Septic Mice. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(1):435–444. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bomfim T.R., Forny-Germano L., Sathler L.B., Brito-Moreira J., Houzel J.C., Decker H., et al. An anti-diabetes agent protects the mouse brain from defective insulin signaling caused by Alzheimer's disease- associated Abeta oligomers. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1339–1353. doi: 10.1172/JCI57256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freiherr J., Hallschmid M., Frey W.H., Brünner Y.F., Chapman C.D., Hölscher C., et al. Intranasal insulin as a treatment for Alzheimer's disease: a review of basic research and clinical evidence. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(7):505–514. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0076-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scherer T., Sakamoto K., Buettner C. Brain insulin signalling in metabolic homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(8):468–483. doi: 10.1038/s41574-021-00498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yarchoan M., Arnold S.E. Repurposing diabetes drugs for brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes. 2014;63:2253–2261. doi: 10.2337/db14-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramakrishnan U., Imhoff-Kunsch B., DiGirolamo A.M. Role of docosahexaenoic acid in maternal and child mental health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:958S–962S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26692F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.K.M. Appleton, P.D. Voyias, H.M. Sallis, S. Dawson, A.R. Ness, R. Churchill, et al., Omega-3 fatty acids for depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11(2021)CD004692.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004692.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Cutuli D. Functional and Structural Benefits Induced by Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids During Aging. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(4):534–542. doi: 10.2174/1570159X14666160614091311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bazan N.G., Molina M.F., Gordon W.C. Docosahexaenoic acid signalolipidomics in nutrition: significance in aging, neuroinflammation, macular degeneration, Alzheimer's, and other neurodegenerative diseases. Annu Rev Nutr. 2011;31(1):321–351. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.012809.104635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bazinet R.P., Layé S. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(12):771–785. doi: 10.1038/nrn3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quinn J.F., Raman R., Thomas R.G., Yurko-Mauro K., Nelson E.B., Van Dyck C., et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1903. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yurko-Mauro K. Cognitive and cardiovascular benefits of docosahexaenoic acid in aging and cognitive decline. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:190–196. doi: 10.2174/156720510791050911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo X., Jia R.u., Yao Q., Xu Y., Luo Z., Luo X., et al. Docosahexaenoic acid attenuates adipose tissue angiogenesis and insulin resistance in high fat diet-fed middle-aged mice via a sirt1-dependent mechanism. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016;60(4):871–885. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanza I.R., Blachnio-Zabielska A., Johnson M.L., Schimke J.M., Jakaitis D.R., Lebrasseur N.K., et al. Influence of fish oil on skeletal muscle mitochondrial energetics and lipid metabolites during high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304(12):E1391–E1403. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00584.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Storlien L.H., Kraegen E.W., Chisholm D.J., Ford G.L., Bruce D.G., Pascoe W.S. Fish oil prevents insulin resistance induced by high-fat feeding in rats. Science. 1987;237(4817):885–888. doi: 10.1126/science.3303333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughey C.C., Hittel D.S., Johnsen V.L., Shearer J. Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp in the conscious rat. J Vis Exp. 2011 doi: 10.3791/2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao H., Yan P., Zhang S., Huang H., Huang F., Sun T., et al. Long-Term Dietary Alpha-Linolenic Acid Supplement Alleviates Cognitive Impairment Correlate with Activating Hippocampal CREB Signaling in Natural Aging Rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(7):4772–4786. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9393-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorgich E.A.C., Parsaie H., Yarmand S., Baharvand F., Sarbishegi M. Long-term administration of metformin ameliorates age-dependent oxidative stress and cognitive function in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2021;410:113343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2021.113343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez V.A., Sabatini B.L. Anatomical and physiological plasticity of dendritic spines. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30(1):79–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karpova A., Mikhaylova M., Bera S., Bär J., Reddy P., Behnisch T., et al. Encoding and transducing the synaptic or extrasynaptic origin of NMDA receptor signals to the nucleus. Cell. 2013;152(5):1119–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benedict C., Kern W., Schultes B., Born J., Hallschmid M. Differential sensitivity of men and women to anorexigenic and memory-improving effects of intranasal insulin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(4):1339–1344. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benedict C., Hallschmid M., Schmitz K., Schultes B., Ratter F., Fehm H.L., et al. Intranasal insulin improves memory in humans: superiority of insulin aspart. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(1):239–243. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duda P., Wiśniewski J., Wójtowicz T., Wójcicka O., Jaśkiewicz M., Drulis-Fajdasz D., et al. Targeting GSK3 signaling as a potential therapy of neurodegenerative diseases and aging. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2018;22(10):833–848. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2018.1526925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto N., Matsubara T., Sobue K., Tanida M., Kasahara R., Naruse K., et al. Brain insulin resistance accelerates Abeta fibrillogenesis by inducing GM1 ganglioside clustering in the presynaptic membranes. J Neurochem. 2012;121:619–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanley M., Macauley S.L., Holtzman D.M. Changes in insulin and insulin signaling in Alzheimer's disease: cause or consequence? J Exp Med. 2016;213:1375–1385. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biessels G.J., Reagan L.P. Hippocampal insulin resistance and cognitive dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(11):660–671. doi: 10.1038/nrn4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Llorens-Martin M., Jurado J., Hernandez F., Avila J. GSK-3beta, a pivotal kinase in Alzheimer disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2014;7:46. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neschen S., Morino K., Dong J., Wang-Fischer Y., Cline G.W., Romanelli A.J., et al. n-3 Fatty acids preserve insulin sensitivity in vivo in a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha-dependent manner. Diabetes. 2007;56:1034–1041. doi: 10.2337/db06-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeda S., Sato N., Uchio-Yamada K., Sawada K., Kunieda T., Takeuchi D., et al. Diabetes-accelerated memory dysfunction via cerebrovascular inflammation and Abeta deposition in an Alzheimer mouse model with diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7036–7041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000645107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosales-Corral S., Tan D.-X., Manchester L., Reiter R.J. Diabetes and Alzheimer disease, two overlapping pathologies with the same background: oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2015/985845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perluigi M., Swomley A.M., Butterfield D.A. Redox proteomics and the dynamic molecular landscape of the aging brain. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;13:75–89. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manolopoulos K.N., Klotz L.-O., Korsten P., Bornstein S.R., Barthel A. Linking Alzheimer's disease to insulin resistance: the FoxO response to oxidative stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(11):1046–1052. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bloch-Damti A., Bashan N. Proposed mechanisms for the induction of insulin resistance by oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7(11-12):1553–1567. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rains J.L., Jain S.K. Oxidative stress, insulin signaling, and diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50(5):567–575. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tong Y., Zhou W., Fung V., Christensen M.A., Qing H., Sun X., et al. Oxidative stress potentiates BACE1 gene expression and Abeta generation. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2005;112:455–469. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao J., Wu H., Cao Y., Liang S., Sun C., Wang P., et al. Maternal DHA supplementation protects rat offspring against impairment of learning and memory following prenatal exposure to valproic acid. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;35:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johansson I., Monsen V.T., Pettersen K., Mildenberger J., Misund K., Kaarniranta K., et al. The marine n-3 PUFA DHA evokes cytoprotection against oxidative stress and protein misfolding by inducing autophagy and NFE2L2 in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Autophagy. 2015;11(9):1636–1651. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1061170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mayo L., Trauger S.A., Blain M., Nadeau M., Patel B., Alvarez J.I., et al. Regulation of astrocyte activation by glycolipids drives chronic CNS inflammation. Nat Med. 2014;20(10):1147–1156. doi: 10.1038/nm.3681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heppner F.L., Greter M., Marino D., Falsig J., Raivich G., Hövelmeyer N., et al. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis repressed by microglial paralysis. Nat Med. 2005;11(2):146–152. doi: 10.1038/nm1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Domínguez-González M., Puigpinós M., Jové M., Naudi A., Portero-Otín M., Pamplona R., et al. Regional vulnerability to lipoxidative damage and inflammation in normal human brain aging. Exp Gerontol. 2018;111:218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matt S.M., Johnson R.W. Neuro-immune dysfunction during brain aging: new insights in microglial cell regulation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2016;26:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Esiri M.M. Ageing and the brain. J Pathol. 2007;211(2):181–187. doi: 10.1002/path.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim J.D., Yoon N.A., Jin S., Diano S. Microglial UCP2 Mediates Inflammation and Obesity Induced by High-Fat Feeding. Cell Metab. 2019;30(5):952–962.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Denver P., Gault V.A., McClean P.L. Sustained high-fat diet modulates inflammation, insulin signalling and cognition in mice and a modified xenin peptide ameliorates neuropathology in a chronic high-fat model. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(5):1166–1175. doi: 10.1111/dom.13210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu J., Gao H., Zhang L.i., Rong S., Yang W., Ma C., et al. Melatonin alleviates cognition impairment by antagonizing brain insulin resistance in aged rats fed a high-fat diet. J Pineal Res. 2019;67(2) doi: 10.1111/jpi.12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thaler J.P., Yi C.-X., Schur E.A., Guyenet S.J., Hwang B.H., Dietrich M.O., et al. Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(1):153–162. doi: 10.1172/JCI59660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu L., Chan C. The role of inflammasome in Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;15:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.T. Schmidt-Glenewinkel and M. Figueiredo-Pereira, Inflammation as a Mediator of Oxidative Stress and UPS Dysfunction, in The Proteasome in Neurodegeneration, L. Stefanis and J.N. Keller, Editors. 2006, Springer US: Boston, MA. p. 105-131.

- 64.Maphis N., Xu G., Kokiko-Cochran O.N., Jiang S., Cardona A., Ransohoff R.M., et al. Reactive microglia drive tau pathology and contribute to the spreading of pathological tau in the brain. Brain. 2015;138(6):1738–1755. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Devassy J.G., Leng S., Gabbs M., Monirujjaman M., Aukema H.M. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Oxylipins in Neuroinflammation and Management of Alzheimer Disease. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:905–916. doi: 10.3945/an.116.012187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.L.D. Harvey, Y. Yin, I.Y. Attarwala, G. Begum, J. Deng, H.Q. Yan, et al., Administration of DHA Reduces Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Associated Inflammation and Alters Microglial or Macrophage Activation in Traumatic Brain Injury. ASN Neuro. 7(2015).doi:10.1177/1759091415618969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Kuda O. Bioactive metabolites of docosahexaenoic acid. Biochimie. 2017;136:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Joffre C., Rey C., Laye S. N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and the Resolution of Neuroinflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1022. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Viola K.L., Klein W.L. Amyloid beta oligomers in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis, treatment, and diagnosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:183–206. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gravitz L. Drugs: a tangled web of targets. Nature. 2011;475(7355):S9–S11. doi: 10.1038/475S9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morris M., Maeda S., Vossel K., Mucke L. The many faces of tau. Neuron. 2011;70(3):410–426. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jansen W.J., Ossenkoppele R., Knol D.L., Tijms B.M., Scheltens P., Verhey F.R.J., et al. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1924. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mandal P.K., Ahuja M. Comprehensive nuclear magnetic resonance studies on interactions of amyloid-beta with different molecular sized anesthetics. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(Suppl 3):27–34. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jin M., Shepardson N., Yang T., Chen G., Walsh D., Selkoe D.J. Soluble amyloid beta-protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce Tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5819–5824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017033108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.He Z., Guo J.L., McBride J.D., Narasimhan S., Kim H., Changolkar L., et al. Amyloid-beta plaques enhance Alzheimer's brain tau-seeded pathologies by facilitating neuritic plaque tau aggregation. Nat Med. 2018;24:29–38. doi: 10.1038/nm.4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barthélemy N.R., Li Y., Joseph-Mathurin N., Gordon B.A., Hassenstab J., Benzinger T.L.S., et al. A soluble phosphorylated tau signature links tau, amyloid and the evolution of stages of dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 2020;26(3):398–407. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0781-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gao H., Yan P., Zhang S., Nie S., Huang F., Han H., et al. Chronic alpha-linolenic acid treatment alleviates age-associated neuropathology: Roles of PERK/eIF2alpha signaling pathway. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;57:314–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Green K.N., Martinez-Coria H., Khashwji H., Hall E.B., Yurko-Mauro K.A., Ellis L., et al. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid and docosapentaenoic acid ameliorate amyloid-beta and tau pathology via a mechanism involving presenilin 1 levels. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4385–4395. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0055-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lim G.P., Calon F., Morihara T., Yang F., Teter B., Ubeda O., et al. A diet enriched with the omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid reduces amyloid burden in an aged Alzheimer mouse model. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3032–3040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4225-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grimm M.O., Mett J., Stahlmann C.P., Haupenthal V.J., Blumel T., Stotzel H., et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid increase the degradation of amyloid-beta by affecting insulin-degrading enzyme. Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;94:534–542. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2015-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang H., Wang R., Zhao Z., Ji Z., Xu S., Holscher C., et al. Coexistences of insulin signaling-related proteins and choline acetyltransferase in neurons. Brain Res. 2009;1249:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rivera E.J., Goldin A., Fulmer N., Tavares R., Wands J.R., de la Monte S.M. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and function deteriorate with progression of Alzheimer's disease: link to brain reductions in acetylcholine. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8(3):247–268. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marini A.M., Jiang H., Pan H., Wu X., Lipsky R.H. Hormesis: a promising strategy to sustain endogenous neuronal survival pathways against neurodegenerative disorders. Ageing Res Rev. 2008;7(1):21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xu J., Rong S., Xie B., Sun Z., Deng Q., Wu H., et al. Memory Impairment in Cognitively Impaired Aged Rats Associated With Decreased Hippocampal CREB Phosphorylation: Reversal by Procyanidins Extracted From the Lotus Seedpod. J. Gerontology Series a-Biological Sci. Medical Sci. 2010;65A(9):933–940. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Grimes C.A., Jope R.S. CREB DNA binding activity is inhibited by glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta and facilitated by lithium. J Neurochem. 2001;78:1219–1232. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.