Abstract

Background

Preceptorship in nursing has been a valued concept in nursing. Speciality area such as mental health nursing has a massive gap in research study. To develop sturdy mental health nursing workforce, it is necessary to conduct more studies.

Aim

This literature review aims to explore preceptor's experience in precepting undergraduate nursing students in mental health.

Design

Systematic review of literature.

Methods

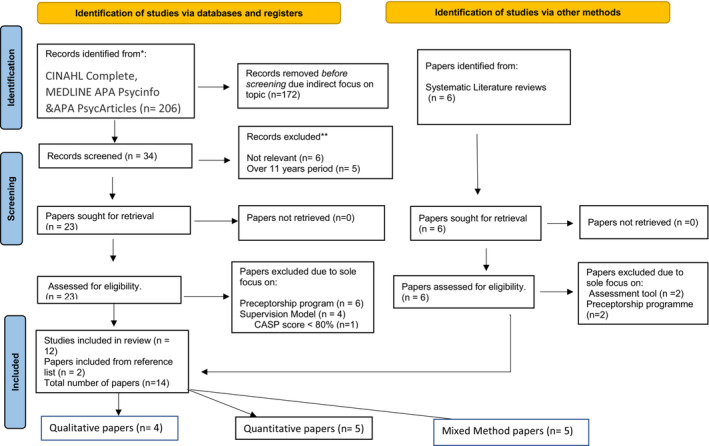

The systematic review was conducted from January 2021 to August 2021. Population of the studies included Registered Nurses supervising nursing students in the clinical area. Only studies conducted in English were included. A systematic search using EBSCO Host databases, CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE APA Psycinfo & APA PsycArticles, has been used in this review paper. Papers were also selected from the citation reference of included papers. The new version of the PRISMA 2020 guidelines used to represent the process of selection of papers has been incorporated as part of this review. The final set of data included 14 original papers meeting the eligibility criteria which involved quantitative (n = 5), qualitative (n = 4) and mixed‐method studies (n = 5).

Result

Results were presented under three major themes: time‐consuming, lack of recognition and need extra support. Further research is required in the mental health clinical setting to effectively explore the impact of relationships between preceptors and the preceptees.

Conclusion

Preceptors reported supervising students in the clinical area has many benefits. However, some challenges they raised were increase in workload, requiring some guidance and acknowledgement from the organization.

Keywords: clinical placement, nursing students and mental health, precepting, preceptor, supervising

1. INTRODUCTION

Preceptorship in nursing has been practiced globally for decades. It is an important concept in nursing used to develop inter‐professional relationships between clinicians and students as they enhance their practical application of knowledge and clinical skills. Broadbent et al. (2014) explain preceptorship is connection and sharing between experienced and novice nurses, which in turn produces a valuable nursing profession. Preceptorship is essential to guide the new nurses to think critically whilst caring for a patient in a practical setting. Preceptors need to be supported in this process, especially when it comes to making decisions on a pass or fail for a student's placement (Natan et al., 2014). In addition, preceptors require adequate knowledge, skill, interest and confidence in precepting and assessing students. Managing students in the clinical area can be challenging, there are very few studies conducted on the student preceptoring experience in the last 10 years in the literature.

The objective of the literature review was to identify the existing research papers regarding the experience of preceptors in supervising undergraduate nursing students in mental health in the last 10 years. However, due to the lack of mental health‐specific studies authors decided to review papers available in general nursing area which will be useful to lean some lessons for mental health. The purpose of the review was to find, analyse and critique the existing original research papers regarding preceptor's experience in supervising undergraduate nursing students which might benefit future research in this area and contribute to effective preceptorship in mental health clinical placement. For the purpose of this paper a preceptor is defined as a Registered Nurse (RN) responsible for taking care of students whilst on clinical placement. Preceptors also refers to buddy nurses and mentors. Precepting refers to the process of looking after and guiding a student during their clinical placement. Seniors refers to the experienced preceptors.

2. BACKGROUND

The authors searched for recent studies conducted in mental health in the area of preceptor's experience during clinical placement and identified very few studies in mental health. Out of the 14 papers included, only two studies (Boardman et al., 2018; Lienert‐Brown et al., 2018) were conducted purely in mental health settings. Two studies combined mental health settings with the general ward areas (Burke et al., 2016; Cassidy et al., 2012) and the remaining 10 papers were from general and community settings. This revealed a massive gap in studies conducted regarding preceptor's experience in clinical placement in nursing. The question came up here is, by Preceptoring undergraduate nursing students what lessons can be learnt and applied to Mental Health clinical setting? This prompted researchers to undertake further research in mental health clinical placement.

3. METHOD

3.1. Search strategy

The systematic review of the literature was conducted and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for systematic reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021). To identify research papers, initial search was conducted using a Boolean search strategy and database included were CINAHL complete, MEDLINE and APA Psycinfo, APA PsycArticles and retrieved 706 papers. The search terms entered were *Preceptor, *precepting, clinical placement, *supervising, nursing students and mental health. The search was further narrowed by using an inclusion criterion that included English language, peer‐reviewed papers, full‐text original papers, studies done in human only and original papers published within the last 11 years (2010 to April 2021). The exclusion criteria were studies solely about student nurses experience. Through this search strategy the authors retrieved 206 Papers. The time frame was purposefully selected by the authors to find current research papers for relevancy to clinical practice.

3.2. Screening

In the screening process, duplicates of papers were removed based on their title and abstract leaving 34 papers. Papers were further screened using title and abstract which reduced the total of included papers to 23. Following application of specified inclusion and exclusion criteria eliminated papers exclusively focused on preceptorship programme (n = 6) and supervision model (n = 4), resulted in retaining 13 papers.

3.3. Analysis and quality appraisal

From each study, following information were extracted by the authors; the authors, year, country, aim of the study, methodology, population, data collection method and analysis, limitations and key findings of the study (Table 1). The authors examined the papers and eliminated papers not directly focused on preceptor's experience. All the relevant papers were combined, data similarities noted, critiqued and produced the report in three headings. After applying the Clinical Appraisal Skill Program (CASP) Munn et al. (2014) tool, further one paper was eliminated due to receiving a score of less than 80%. An additional six papers were identified from reference lists of literature review papers and underwent further screening. The CASP qualitative checklist and CASP cohort study check list was used to confirm the quality (CASP UK, 2020). CASP scoring less than 80% were excluded from the review. This process ensured the inclusion of 14 research papers (Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of literature findings

| Author, year & origin | Research aims | Methodology | Population | Data collection method and analysis | Limitations | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Anderson et al. (2020) Australia |

Registered Nurse's perspectives of supporting nursing students on placements | Qualitative | 15 participants with 5‐year experience and previously worked with nursing students. Included Clinical Registered Nurses (RN), nursing managers and clinical educators (13 females and 2 males) |

Individual semi structured interview Constant comparative analysis |

Participants were from only one state. Researchers had preconceived idea regarding RN's having lack of support. Small sample size |

Nurses perceived supervising a student is an extra task along with other responsibilities. Due to lack of time to teach the students on clinical placement, students often missed out on opportunities. RNs believed that their patient load must be reduced to adequately support the students. Even after providing support to students utilizing their own time their effort was not recognized by the system. Preceptors would like to be acknowledged for the extra effort by providing certificate. |

|

Boardman et al. (2018) Australia |

To understand preceptor's experience and satisfaction with a mental health integrated clinical learning model (ICLM) |

Qualitative |

Purposive sample of 13 preceptors from one mental health service |

Focus group Interviews Thematic analysis |

Findings are context bound. Small sample size from one unit. No demographic information was sourced |

Along with evaluating the ICLM model preceptors reported that students were not adequately prepared for mental health placement. To improve their confidence students should visit the facility before the commencement of placement to familiarize themselves. Preceptors mentioned, students must be prepared of the role of the preceptor by the educators. In addition, often students started placement without any specific objectives which made preceptors role difficult. Students must be prepared to take initiative on placement and additional support must be provided by clinical support nurse. |

|

Broadbent et al. (2014) Australia |

Preceptor's experience in managing undergraduate students in clinicals |

Mixed |

Selected 120 clinical preceptors of undergraduate nursing students through purposive sampling and 34 participants returned their survey. |

Survey with four‐point Likert scale was used for qualitative part. Data managed by using NVivo 8 Analysed by using constant comparative method. Used questionnaire for quantitative and analysed by using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) |

Not specified |

Preceptors had lack of qualification and experience to precept. Preceptorship experience added on to the existing knowledge and helped to identify future professional development needs. Regarding the preparation to supervise students had mixed information. Some felt they were given adequate information however, others reported they needed to be prepared well. Also informed, undertaking preceptorship training improved the skills to supervise and teach students. When assessment criteria were changed by the university the preceptors were not communicated clearly which caused confusion and difficulty in assessing the student performance. Participants highlighted the benefits students carried to the site. Students brought positive knowledge to the area by seeking clarifications for current issues. Working with students also contributed to preceptor's own learning and professional growth and development. Preceptors expected more information regarding paperwork from university before commencement of placement, availability of university staff and preceptorship training. |

|

Burke et al. (2016) Ireland |

To explore preceptors experience in using competence assessment tool in clinical competence. |

Mixed method |

17 nurse preceptors from general and psychiatry for Qualitative study 843 nurse preceptors from general and psychiatry in a local catchment area for Quantitative study. |

Focus groups for qualitative. Descriptive survey for quantitative Descriptive analysis |

Limited participants in focus group Generalization of findings is limited due to inclusion of only one geographical area. |

Majority of the participants felt the assessment tool was alright to work with, however, some felt the language in the tool was complex and they were just ticking the boxes by using their own judgement. The tool was also lengthy and time consuming and was unable to manage with their workload, The content of the assessment tool was difficult to understand, there was repetitive language, and also was time‐consuming. Assessment was difficult to get through due to the time constraints with other responsibility on clinicals. Preceptors believe consistent preceptorship is important for accurate assessment and recommended to review the assessment tool. |

|

Cassidy et al. (2012) Ireland |

Preceptor's views and experiences of assessing undergraduate nursing degree students using competency‐based approach. |

Mixed |

16 participants from general, mental health and intellectual disability nursing through Poster advertisement |

Semi‐structured interview & thematic analysis for qualitative. Survey descriptive analysis for quantitative |

Competing demand in the clinical environment impact on preceptors' experiences of competency assessment process. |

Only qualitative result is published in this paper. Overall, preceptors valued the supervision of students. They mentioned building rapport with students and continuous communication is important during preceptorship to encourage leaning. Some preceptors identified, supervising students was an added extra to their workload in the clinical setting and was demanding preceptor's time considerably. Managing students when there is staff shortage was another addition to their workload. Language used in assessment tool was challenging to follow, however, it became better over time with experience. |

|

Cusack et al. (2020) Australia (Adelaide) |

To understand nurse's perception of the level of recognition, preparedness and support provided when supervising undergraduate nursing students in clinicals. | Mixed | 59 nurses, six focus groups from 12 different wards of two hospitals |

Survey and focus group. And feedback sessions Descriptive statistics for quantitative Ritchie and Spenser analyses for applied policy research – qualitative |

Small sample size Tool was not validated psychometrically. Findings may not be generalisable because study involved only one state of Australia. |

Even though RNs were experienced, they had no previous exposure of teaching and supporting students. The common assumption is that nurses have teaching skills. However, nurses lack knowledge in teaching students, hence need more support in this area. RNs are expected to complete student assessment along with their regular patient allocation. Therefore, they have less time to complete the student task and they forced themselves to use their own time after work. The extra work of supervising students is not recognized by the system. Hence nurses perceived it as an extra burden, and they had to choose between quality nursing care and providing good learning experience to students. |

|

Haitana & Bland (2011) New Zealand |

To understand experiences of being a preceptor and factors affecting the role. |

Qualitative |

Purposive sample of 5 Participants from medical surgical wards through posters. |

Interview A modified framework based on Burnard (1991) and informed by Glaser and Strauss (1967) was used to guide data analysis |

Difficult to generalize due to small sample size and involvement of limited area. |

Building rapport with the student was challenging due to inconsistent preceptorship which caused difficulty to develop rapport. Failure to fully trust the student led to dissatisfaction of supervisor role and hesitancy to offer more opportunities for students. When preceptor spent less time with the students, they always had an internal conflict regarding safety of the patient whilst providing autonomy for the student to perform a task. |

|

Hallin and Danielson (2010) Sweden |

Describe RN's perceptions of nursing student's preparation and study approaches in clinical workplace | Quantitative | Convenience sample of 196 RNs with preceptorship experience from 16 units of one hospital |

Questionnaire SPSS |

Difficult to generalize because of inclusion of only one hospital |

Preceptoring affects daily work, some reported that they were not prepared for the role. When students demonstrate inadequate knowledge and not enthusiastic to learn, prompted RNs to assign only tasks which is familiar to students and not preparing students. Preceptor's experience did not make any difference in preceptorship. |

|

Kalischuk et al. (2013) Canada |

To examine preceptor's perception of benefits, rewards, supports challenges and commitment of preceptor's role | Quantitative | Purposive sample of 331 preceptors |

Survey (n = 129 include 8 from Mental health) SPSS |

In general preceptors felt rewarded when students demonstrated interest in practice. Some preceptors supervised students for getting promotion and others to increase their knowledge. Overall preceptors had positive experience of being a preceptor. However, they felt challenged due to lack of time to manage students with patient workload. The other challenges were unmotivated students, unclear instructions to preceptors regarding the expectation and providing constructive feedback especially to students experiencing difficulties. Some recommendations from preceptors were reduce workload when supervising student, provide professional development hours, a certificate of recognition, more support, more preceptorship training and more clear evaluation tool. |

|

|

Lienert‐Brown et al. (2018) New Zealand |

To explore mental health nurse's views and experiences of working with undergraduate nursing students and determine what factors influence the experience |

Quantitative |

Convenience sample of 89 nurses from a specialist mental health service for inpatient/facility work and/or for work in the community within one district health board. |

questionnaire Descriptive analysis |

Finding cannot be generalized due to low response for the survey. |

Overall participants felt confident, well supported and had a positive perception of the role however, their workload was not reduced during preceptorship period. RN's years of experience had no influence on preceptorship role whereas the clear instruction preceptors received regarding the expectation of their role made all the difference. Engaging with some form of education as part of preceptorship boosted own knowledge and confidence which helped to plan clinical education and received appreciation. Support received from seniors and colleagues also increased confidence in providing preceptorship. |

|

McCarthy and Murphy (2010) Ireland |

To explore preceptor's views and experiences of preceptoring undergraduate nursing students. |

Mixed method |

970 preceptors from 124 healthcare units including hospital and community care sites through advertisement on ward or units. |

Self‐administered questionnaire Descriptive statistical analysis for quantitative Content analysis for qualitative |

Not highlighted |

Majority of the participants enjoyed the role as a preceptor and wanted to continue as a preceptor. Some preceptors reported that they never had a feedback of their role, few did not feel supported and acknowledged. Preceptors reported that they faced issues with lack of time to support the students due to heavy workload, staff shortage and busy shift. Preceptors felt guilty when unable to spent adequate time with students. Due to inconsistent preceptorship, it was hard to complete student assessment. When there were underperforming students, supervisors found it hard to fail them because there was no adequate managerial support. Preceptors suggested to assign a co‐preceptor for each student from the commencement of placement. Preceptors mentioned lack of feedback of their role and would like to be evaluated by students and managers. Some preceptors expected financial remuneration for their extra work of preceptorship. |

|

Natan et al. (2014) Israel |

Explore connection between characteristics of preceptorship, supports, benefits, rewards and commitment to the preceptor role in Israel |

Quantitative |

Convenience sample of 200 RN from hospitals and community settings |

Questionnaire survey SPSS |

Unable to generalize. |

Subjects had moderate dedication to the role. Many preceptors valued the responsibility and wanted to continue as preceptor. Preceptorship course better equipped preceptors for the role, however, some felt the course did not prepare them adequately for the role. Preceptors acknowledged the support received from head nurse, coordinators, and university teachers. |

|

O'Brien et al. (2013) Australia |

Evaluate perceptions of RN, RM and EN about their experience of preceptoring an undergraduate student |

Quantitative |

337 preceptors Invited to complete Survey from nine acute care facilities |

Clinical preceptor experience evaluation tool (CPEET) IBM SPSS Statistics 20 |

Not specified |

Majority of preceptors were satisfied however, felt challenging when supervised unmotivated students. Those preceptors who completed preceptor course had higher satisfaction of the role. Managerial support also made considerable difference in preceptorship experience. |

|

Wu et al. (2016) Singapore |

To explore preceptor's perspectives about clinical assessment for undergraduate nursing students in transition to practice |

qualitative |

Purposive sample of 17 preceptors from two tertiary hospitals in Singapore |

Focus groups. Thematic analysis |

Transferability was limited due to sample size and organizational culture in Singapore. Future studies to include administrators and academics as they also support students. |

Preceptors with less experience faced difficulty in assessing the student using the assessment tool. Preceptors took time to develop their own style of teaching and supervising students. The preceptors felt well supported by managers and the university. Many preceptors mentioned that the preceptor training lacked focus on clinical assessment tool. Preceptors recognized that sharing preceptor experience with other preceptors would improve the experience |

FIGURE 1.

Systematic review of Preceptor's experience in supervising undergraduate nursing students: Lessons learned for mental health nursing

3.4. Ethics

Ethical approval/patient consent was not required.

4. RESULTS

The final data set of 14 papers for this literature review included a mixture of qualitative studies (n = 4), quantitative studies (n = 5) and mixed‐method studies (n = 5). Most of the studies are from Australia (n = 5) followed by Ireland (n = 3), New Zealand (n = 2) and one each from Canada, Israel, Singapore, Sweden (Figure 1).

Even though there were some similarities with the populations the sample sizes varied considerably in each research. Qualitative study samples varied from five to 34, including the qualitative portion of mixed‐method study. Quantitative participant numbers varied from 89 to 970 which included the quantitative phase of the mixed method studies. Sampling method in the studies were either purposive or convenience sampling. The authors, identified, examined, evaluated and analysed 14 relevant literature and located some recurring central themes and interpreted the result under three key themes as follows.

4.1. Theme 1: Time‐consuming

The key finding in the majority of the studies were preceptorship is time‐consuming. Out of 14 papers included in this review, nine studies reported preceptorship as a time‐consuming activity (Anderson et al., 2020; Broadbent et al., 2014; Burke et al., 2016; Cassidy et al., 2012; Cusack et al., 2020; Haitana & Bland, 2011; Kalischuk et al., 2013; McCarthy & Murphy, 2010; Wu et al., 2016). Preceptors are supervising students along with their regular responsibility on the ward (Kalischuk et al., 2013). Anderson et al. (2020) reports that supervising a student requires extra time and energy.

The reasons identified for utilizing extra time was staff's workload and students requiring more time to complete a simple task whilst on placement, so missing out on opportunities (Anderson et al., 2020). This finding echoed Kalischuk et al. (2013)'s finding of preceptor's recognition of insufficient time to look after patients whilst supervising students. Preceptors identified feelings of obligation to spend extra time‐supervising students on top of their already assigned workload. In line with the other responsibilities on the ward, preceptors often fail to spend quality time with the student, especially when it comes to completing their clinical review assessments (Cusack et al., 2020). Therefore, preceptors ended up contributing their own time to complete student assessments. Cusack et al. (2020) added, the key recommendation from preceptors was to reduce their allocated patient numbers to compensate for a student supervision workload. Burke et al. (2016)'s findings corresponded with the previous study by mentioning Universities often had difficult and lengthy assessment tools that took longer time to understand and were time‐consuming to complete. Similarly, Cusack et al. (2020) mentioned in the qualitative phase of the mixed method study that RNs are expected to complete student assessments along with their assigned patient workload tasks which provided no time for completing the clinical assessment tool for each student, often staying behind to finish the assessment. Preceptors remarked that some assessment tools were complicated and used complex language making them additionally complicated to evaluate (Burke et al., 2016; Cassidy et al., 2012). However, once preceptors became familiar with the assessment tool language and format, they became more comfortable completing student clinical assessments (Cassidy et al., 2012). Sometimes when the assessment tool is updated by the education provider, they fail to communicate this information to the preceptors which can also contribute to the time required to complete the assessment tool by preceptors (Broadbent et al., 2014).

The quantitative findings of McCarthy and Murphy (2010) reported that even though student supervision is time‐consuming, 88.6% of participant's enjoyed supporting students and wanted to provide ongoing support. 76.9% of preceptors had never failed a student in clinical practice and some participants (47.2%) mentioned it was hard to fail the underperforming students on clinical placement. In addition, preceptors highlighted that when they are supervising an unmotivated/failing student, preceptors lacked clinical support from Seniors. When preceptors spent inadequate time with the students, they lacked confidence in assigning tasks to the students due to patient safety concerns resulting in internal conflict and guilt in preceptors (Haitana & Bland, 2011; McCarthy & Murphy, 2010). Kalischuk et al. (2013) recognized, additional challenges experienced by supervisors along with lack of time, added confusion to their role, especially whilst providing constructive feedback to students who presented with less motivation. This information was consistent with O'Brien et al. (2013)'s findings that preceptors had less gratification with unmotivated students which resulted in increased preceptor burnout. Hallin and Danielson (2010) added, there is connection between RN's perception and interest of supervising and teaching students. However, years of experience in preceptorship made no difference for providing ongoing effective preceptorship. Even though constructive feedback is a good support for students, especially to underperforming, preceptors were not able to provide adequate time for constructive feedback due to the excessive workload and lack of time (Kalischuk et al., 2013). Additionally, Haitana and Bland (2011) highlights preceptors hesitate to provide autonomy to students because the ultimate responsibility in patient care remains with RNs.

Wu et al. (2016) highlighted that prior to student's clinical placement, preceptors self‐prepared by updating their knowledge to effectively teach and guide students in the clinical setting. Due to time constraints at work, preceptors had to carry some of their work home. The preceptors were happy to utilize their own time in teaching because potentially it was seen to be contributing to their professional development and contributing into the nursing profession. Eventually, supervisors developed their own style of teaching and managing students as part of effective preceptoring which in turn helped with better time management. Researchers further reported that preceptors had experienced lots of stress whilst managing students on the ward. Developing a one‐to‐one relationship was deemed to be a crucial part of the student–preceptor relationship, but also seen take time to develop. Boardman et al. (2018) mentioned, to improve student–preceptor relationships, students must contact the placement area and preceptor in person or by telephone before the commencement of their placement, which will go a long way in helping both the student and preceptor, feeling confident and comfortable about the future clinical placement period. The most common recommendation was RNs need to be provided with extra time whilst supervising students; for example reducing their patient workload because teaching, supporting and evaluating nursing students is time‐consuming.

4.2. Theme 2: Lack of recognition

RNs indicated that they wanted recognition for their extra work. Preceptors are contributing extra time and effort on top of their daily workload; however, their hard work was not recognized by the organization (Anderson et al., 2020). Cusack et al. (2020) pointing out, the dual responsibility of preceptors was recognized by the colleagues, however, were not acknowledged by managers or educators. When the efforts were not recognized preceptors may become unmotivated to continue supporting students over time (Anderson et al., 2020). According to Kalischuk et al. (2013), preceptors had a feeling of recognition when the students showed interest in placement, however, some RNs accepted preceptorship roles as a way of increasing their chances for promotion and for others the motivation was for professional development. Kalischuk et al. (2013) further explains, when asked what the preferred mode of recognition was for preceptors, 85.2% expressed that non‐material awards over material awards were preferred. The highest percentage of subjects (54.8%) requested for In‐service education followed by 37.4% of preceptors wanted reduced patient workload when preceptoring students and 31.3% wanted a certificate of recognition for their supervision time. Even though students supervision is RN's professional responsibility (Nursing and Midwifery Board APHRA, 2020), a significant recommendation in the study was to include student supervision hours in the mandatory professional development. The preceptors recognized among themselves that sharing preceptorship experience in their peer group also improves experience of precepting students (Wu et al., 2016). As part of the need for recognition and support, some preceptors requested feedback about their preceptor performance from managers and that to be included in their performance appraisal. Others suggested financial rewards (McCarthy & Murphy, 2010). Providing recognition to preceptors may help to increase the interest in being a preceptor which will hopefully lead to quality clinical placement experiences for nursing students (Kalischuk et al., 2013).

4.3. Theme 3: Need extra support

Preceptors perceived that when precepting students they should know everything because they have to provide answers to all questions asked by students (Wu et al., 2016). There is a common misconception that nurses are experienced teachers; however, the majority of nurses have little to no exposure to teaching students or providing support to junior staff or students (Cusack et al., 2020). Experienced preceptors developed their own teaching styles over with experience; however, less experienced nurses required more support to provide guidance to junior staff or students. A peer support platform and regular meetings to discuss preceptorship experience was cited as being beneficial for preceptors (Wu et al., 2016). Moreover, regular catch‐up meetings to discuss preceptorship experiences was considered as a support to develop confidence and encouragement, especially in junior preceptors.

Broadbent et al. (2014) discussed preceptor's perspectives in supporting nursing students within the clinical environment, in which preceptors had lack of qualifications to supervise students. They expressed mixed opinions in the study, with some participants stating that they felt they were well equipped for the preceptorship role, whereas others felt they needed more support. Participants mentioned that students also brought new positive experiences to clinical placement by asking current and relevant questions. Preceptors requested for preceptorship workshops as a part of the preceptor support and acknowledged that the preceptorship programme expanded their knowledge (Kalischuk et al., 2013; Lienert‐Brown et al., 2018; O'Brien et al., 2013). A total of 64% of the respondents from Natan et al. (2014)'s study in comparison noted that the preceptorship programme did not adequately prepare RNs to support students. In addition, McCarthy and Murphy (2010) mentioned the content of the preceptorship education was hard to follow and was often not long enough to cover the required content in only two‐day programme and half‐day workshop. Participants further stated, whilst selecting nurses for precepting students it was important to ensure that.

RNs receive adequate education and complete a formal training and assessment course. Extra support received from colleagues and managers in the clinical environment were seen to considerably increase the confidence levels of preceptors (Lienert‐Brown et al., 2018). This finding is consistent with Natan et al. (2014) and O'Brien et al. (2013) who reported, manager's and colleague's support throughout the preceptorship boosted preceptor's level of confidence. Many preceptors reported that they did not receive adequate support (38%) to precept and often felt that they were not appreciated (42.7%) by the management.

In completing the student assessment using the assessment tool, Burke et al. (2016) identified that preceptors needed extra support due to the complex and lengthy nature of the assessment tool. The key areas requiring support that were identified was the language used in the assessment tool and timely communication from education providers to the clinical environment when the tool is updated. Burke et al. (2016) further stated Inconsistent preceptorship was identified as a barrier in completing the assessment effectively. When preceptors are not spending adequate time with the students it was difficult to track student progress. To improve this issue preceptors suggested to assign a co‐preceptor for every student (McCarthy & Murphy, 2010).

5. DISCUSSION

This systematic review aimed to explore the existing literature on preceptor's experience of supervising nursing students in clinical environment such as mental health. Although the authors were interested in preceptors experience in the mental health clinical setting, only 14% of the papers were exclusively from mental health (n = 2) and 14% included mental health area along with general setting (n = 2). The lack of specific papers from mental health setting indicates requirement of further research in this area.

Teaching and supporting students and junior staff are seen to be an important part of general practice and is required as part of maintaining nursing registration (Nursing and Midwifery Board APHRA, 2020). Preceptoring is seen to be a time‐consuming role and often complicated when students are slow to complete given activities (Anderson et al., 2020). Students lack confidence on the ward may be due to anxiety and the unfamiliar circumstances of being on clinical placement in a new hospital or clinical environment (Haitana & Bland, 2011). Another time‐consuming task that is expected of preceptors are the student evaluation which preceptors are expected to complete during the placement period (Cusack et al., 2020). Sometimes, the language used in the competency assessment tool is hard to understand and complex (Burke et al., 2016; Cassidy et al., 2012).

In some instances, the preceptors had to use their intuition to complete the assessment. Other times supervisors had to stay back after the shift utilizing their own time to complete the assessment because they were not able to get it completed during working hours (Cusack et al., 2020). Students were also often not clear about their clinical learning objectives for the placement (Boardman et al., 2018) and expected preceptors to tell them everything rather than doing some placement preparation. Self‐motivation of students is deemed to be an essential factor for a placement to be successful. At times students were unaware of the preceptor's responsibility and hard work behind the scenes. Students visiting or calling the placement area before the commencement of the placement to develop a rapport with the preceptor was a highly recommended strategy to improve the placement experience (Boardman et al., 2018). The expectation is, when the students have some familiarity with the surroundings where they are going to practice there will be an easing of anxiety whilst helping to develop trust between the student and preceptor saving time and effort later on (Boardman et al., 2018). Studies suggested that by reducing regular patient workload of preceptors will enable them to spend more time with the students to provide a better learning and teaching experience (Anderson et al., 2020; Kalischuk et al., 2013).

Along with the RNs patient load, supervising students was an added responsibility and additional work for preceptors (Cassidy et al., 2012). Due to the workload preceptors were not able to explain everything and not able to provide students with variety of experiences whilst on placement. Sometimes preceptors had to think whether they should spend more time in teaching students or taking care of patients which has the possibility of partial fulfilment of both the activities (Cusack et al., 2020). Motivated students demonstrated initiative to work with the preceptor which helps to reduce the stress of preceptors (Boardman et al., 2018; Kalischuk et al., 2013). Recommendations to manage the workload included reducing the patient loads for preceptors for the period of placement. Anderson et al. (2020) and Kalischuk et al. (2013), provide clear objectives and easy‐to‐use assessment tool to preceptors well in advance (Kalischuk et al., 2013). In addition, preceptors require extra time to be with their students and a suitable place to provide constructive feedback.

The literature relating to the need for extra support for preceptors refers to the need for additional support from educators, and preceptorship workshops help to understand complex assessment tools (Broadbent et al., 2014; Natan et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2016). In general, it is assumed that nurses can teach however some nurses may have never had exposure to teaching opportunities or learned teaching skills and techniques (Cusack et al., 2020). Wu et al. (2016) discussed, regular meeting with experienced preceptors is a good way for novice preceptors to improve the skills and learn ways in which to effectively engage with students. Those who received help from colleagues and managers during their preceptorship role had better satisfaction about preceptorship and they offered their ongoing availability for supervising and guiding students on clinical placement (O'Brien et al., 2013).

Studies also indicated there was a need for recognition of preceptor's hard work (Anderson et al., 2020; Cusack et al., 2020). When supervisors are spending their own time to support students on top of their patient allocation it was important to acknowledge their individual efforts. When preceptors are not acknowledged at the managerial level of an organization it can result in the preceptors becoming demotivated from continuing in a preceptorship capacity. Whilst some preceptors requested for material recognition others wanted non‐material recognition (Kalischuk et al., 2013). A certificate of recognition was the common request followed by in‐service education on preceptorship and for organizations to provide professional development hours. All papers in this review indicated there was a necessity for more studies in the area of preceptorship in nursing. Since very few studies were available regarding preceptorship in a mental health clinical environment, it is essential that further research is conducted to explore this unique clinical setting.

6. LIMITATIONS

Limitations of this systematic literature review entails exclusion of papers due to indirect focus on the topic such as inclusion of pharmacy, medical, social work and occupational therapist students. This review also excluded papers over 11 years period which might have included papers on preceptor's experience in mental health settings. The review further eliminated papers with a sole focus on the supervision model, and preceptorship programmes which might have missed some crucial points regarding preceptor's experience in mental health.

7. RECOMMENDATIONS

Since only limited studies exploring the experiences of preceptors in a mental health setting were available at the time of this review future research is recommended to specifically explore this unique and specialized clinical environment. In the current literature review, preceptors struggled to provide constructive feedback to students. More studies recommended in mental health involving timely feedback, especially with underperforming students whilst on mental health placement. Also, the request for extra support for preceptors working in mental health due to workload and time‐consuming during preceptorship should be taken into consideration in future research with the inclusion of more samples.

8. CONCLUSION

This literature review aimed to search, analyse and critique the available literature on preceptor's experience in supervising undergraduate nursing students in mental health. Preceptorship in mental health nursing is pivotal in developing new nurses and enhancing their experiences whilst attending clinical placements as part of a nursing undergraduate degree. Experienced mental health nurses have an opportunity to help mould new nurses by providing consistent support, evaluation and constructive feedback. During this process, preceptors also develop additional knowledge on teaching and learning strategy. It is also mandatory to support preceptors with adequate education and guidance because precepting can be time‐consuming and is often an additional workload for mental health nurses. In addition, it is a professional responsibility of Registered Nurses to teach students. For effective preceptorship staff are required to spend an adequate amount of time with students in order to provide quality nursing clinical experiences which is especially important in the mental health clinical environment.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The lead author searched and screened the literature, then coded, analysed and drafted the manuscript. This work was performed as part of the lead author's Master of Health (Research Practice) course. The second and third author supervised, guided throughout, and assisted with designing the project, screening, analysis and edits of the manuscript. All authors contributed to drafting of the final manuscript.

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria [recommended by the ICMJE (http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/)]:

substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data;

drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors confirm that there are no financial grants or other financial supports involved in this literature review.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest with this literature review.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

Ethics approval has been obtained from Latrobe Regional Hospital (2021‐10‐HREA) and Federation University.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The lead author would like to acknowledge the second and third author's expert guidance throughout the literature review and drafting the manuscript. All authors acknowledge Federation University for the opportunity provided to conduct the literature review as part of Master of Health (Research Practice) the project.

Benny, J. , Porter, J. E. , & Joseph, B. (2023). A systematic review of preceptor's experience in supervising undergraduate nursing students: Lessons learned for mental health nursing. Nursing Open, 10, 2003–2014. 10.1002/nop2.1470

[Correction added on 02 December 2022 after first online publication: The spelling of co‐author Bindu Joseph's name was corrected in this version.]

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated for this literature review.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, C. , Moxham, L. , & Broadbent, M. (2020). Recognition for registered nurses supporting students on clinical placement: A grounded theory study. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37(3), 13–19. 10.37464/2020.373.98 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, G. , Lawrence, K. , & Polacsek, M. (2018). Preceptors' perspectives of an integrated clinical learning model in a mental health environment. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(5), 1420–1429. 10.1111/inm.12441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent, M. , Moxham, L. , Sander, T. , Walker, S. , & Dwyer, T. (2014). Supporting bachelor of nursing students within the clinical environment: Perspectives of preceptors. Nurse Education in Practice, 14(4), 403–409. 10.1016/j.nepr.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, E. , Kelly, M. , Byrne, E. , Ui Chiardha, T. , Mc Nicholas, M. , & Montgomery, A. (2016). Preceptors' experiences of using a competence assessment tool to assess undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education in Practice, 17, 8–14. 10.1016/j.nepr.2016.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASP UK . (2020). CASP check list . https://casp‐uk.net/casp‐tools‐checklists/

- Cassidy, I. , Butler, M. P. , Quillinan, B. , Egan, G. , Mc Namara, M. C. , Tuohy, D. , Bradshaw, C. , Fahy, A. , Connor, M. O. , & Tierney, C. (2012). Preceptors' views of assessing nursing students using a competency based approach. Nurse Education in Practice, 12(6), 346–351. 10.1016/j.nepr.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack, L. , Thornton, K. , Drioli‐Phillips, P. G. , Cockburn, T. , Jones, L. , Whitehead, M. , Prior, E. , & Alderman, J. (2020). Are nurses recognised, prepared and supported to teach nursing students: Mixed methods study. Nurse Education Today, 90, 104434. 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haitana, J. , & Bland, M. (2011). Building relationships: The key to preceptoring nursing students. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand, 27(1), 4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallin, K. , & Danielson, E. (2010). Preceptoring nursing students: Registered Nurses' perceptions of nursing students' preparation and study approaches in clinical education. Nurse Education Today, 30(4), 296–302. 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalischuk, R. G. , Vandenberg, H. , & Awosoga, O. (2013). Nursing preceptors speak out: An empirical study. Journal of Professional Nursing, 29(1), 30–38. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lienert‐Brown, M. , Taylor, P. , Withington, J. , & Lefebvre, E. (2018). Mental health nurses' views and experiences of working with undergraduate nursing students: A descriptive exploratory study. Nurse Education Today, 64, 161–165. 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, B. , & Murphy, S. (2010). Preceptors' experiences of clinically educating and assessing undergraduate nursing students: An Irish context. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(2), 234–244. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01050.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z. , Moola, S. , Riitano, D. , & Lisy, K. (2014). The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. International journal of health policy management, 3(3), 123–128. 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natan, M. B. , Qeadan, H. , & Egbaria, W. (2014). The commitment of Israeli nursing preceptors to the role of preceptor. Nurse Education Today, 34(12), 1425–1429. 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nursing and Midwifery Board APHRA . (2020, 1/02/2017). Registered nurse standards for practice . https://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Codes‐Guidelines‐Statements/Professional‐standards/registered‐nurse‐standards‐for‐practice.aspx

- O'Brien, A. , Giles, M. , Dempsey, S. , Lynne, S. , Kable, A. , McGregor, M. E. , Parmenter, G. , & Parker, V. (2013). Evaluating the preceptor role for pre‐registration nursing and midwifery student clinical education. Nurse Education Today, 34, 19–24. 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie, J. E. , Bossuyt, P. M. , Boutron, I. , Hoffmann, T. C. , Mulrow, C. D. , Shamseer, L. , Tetzlaff, J. M. , Akl, E. A. , Brennan, S. E. , Chou, R. , Glanville, J. , Grimshaw, J. M. , Hróbjartsson, A. , Lalu, M. M. , Li, T. , Loder, E. W. , Mayo‐Wilson, E. , McDonald, S. , … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. V. , Enskär, K. , Heng, D. , Pua, L. , & Wang, W. (2016). The perspectives of preceptors regarding clinical assessment for undergraduate nursing students. International Nursing Review, 63(3), 473–481. 10.1111/inr.12272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated for this literature review.