Abstract

Patient or Public Contribution

Patients, relatives and nurses were involved in this study.

Aim

The aim was to explore patients', relatives' and nurses' experiences of palliative care on an advanced care ward in a nursing home setting after implementation of the Coordination Reform in Norway.

Design

Secondary analysis of qualitative interviews.

Methods

Data from interviews with 19 participants in a nursing home setting: severely ill older patients in palliative care, relatives and nurses. Data triangulation influenced by Miles and Huberman was used.

Results

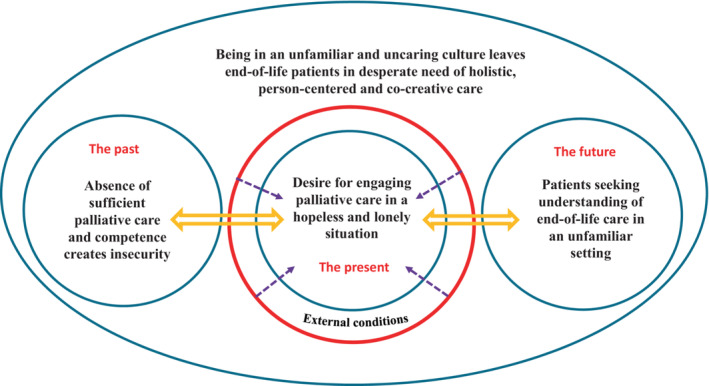

The overall theme was “Being in an unfamiliar and uncaring culture leaves end‐of‐life patients in desperate need of holistic, person‐centred and co‐creative care”. The main themes were: “Desire for engaging palliative care in a hopeless and lonely situation”, “Patients seeking understanding of end‐of‐life care in an unfamiliar setting” and “Absence of sufficient palliative care and competence creates insecurity”. The patients and relatives included in this study experienced an uncaring culture, limited resources and a lack of palliative care competence, which is in direct contrast to that which is delineated in directives, guidelines and recommendations. Our findings reveal the need for policymakers to be more aware of the challenges that may arise when healthcare reforms are implemented. Future research on palliative care should include patients', relatives' and nurses' perspectives.

Keywords: advanced care ward, nurses' experiences, nursing home, palliative care, patients' experiences, relatives' experiences

1. INTRODUCTION

By 2050, the world's population of people aged 60 years and older will double (2.1 billion), and older people often have multimorbidity and complex healthcare needs (World Health Organisation, 2022). In many countries, healthcare service delivery models have shifted toward minimally institutional or non‐institution‐based care services (Ashley et al., 2017). Institution‐based care has been reduced (Mota‐Romero, Tallón‐Martín, et al., 2021) in favour of, for example, home‐based care (Spasova et al., 2018; Vabø, 2012), even throughout the Nordic countries (Bruvik et al., 2017).

Coordinated, patient‐centred healthcare services require organizational competence (Hellesø et al., 2016), and nursing home residents need care that is advanced (Mota‐Romero, Tallón‐Martín, et al., 2021). Patient‐centred care should form the basis for all care decisions and quality measurements (NEJM Catalyst, 2017). In patient‐centred care, the specific healthcare needs and desired healthcare outcomes for each individual person constitute the focus of the care being provided, and healthcare professionals seek to provide patients emotional, mental, spiritual, social, financial and clinical support through active collaboration and shared decision‐making (NEJM Catalyst, 2017). Patient‐centred care can be defined as consisting of six dimensions: (1) Exploration of both the disease and experience of illness; (2) Understanding of the whole person; (3) Finding of common ground relevant to treatment; (4) Integration of prevention and health promotion in care; (5) Strengthening the healthcare professional‐patient relationship; and (6) Being realistic (for example, about the need for interdisciplinary teamwork and/or resource management; Stewart et al., 2006).

In 1972, home healthcare services were first introduced in Norway, and in 1974 treatment at the “lowest level of effective care” (Laveste effektive omsorgsnivå or LEON principle) was implemented in a White Paper (Johansen & Fagerström, 2010). A major reform of the Norwegian healthcare system was undertaken in 2012, known as the Coordination Reform (St. meld. nr. 47, 2008–2009). As part of the reform and with the goal of offering patients the lowest level of effective care, four Regional Health Authorities were established to manage secondary, specialized and hospital care while local municipal authorities now manage primary‐care and community‐care services (rehabilitation, home care nursing, public health, nursing homes and so on). The government is tasked with ensuring through legislation and financial frameworks equal conditions for the provision of healthcare throughout the country, while municipalities in turn are tasked with the organization and provision of high‐quality healthcare and social services to everyone in need of such services, regardless of age or diagnosis (Meld. St. 26, 2014–2015). Accordingly, in Norway the government (through the aforementioned Regional Health Authorities) shoulders responsibility for the care provided in hospital settings while municipalities are responsible for care provided in the community. This is in comparison to a number of countries throughout the world, where the responsibility for care is shared on the governmental and municipal levels (Grimsmo & Magnussen, 2015).

In Norway, primary‐care level community‐care services are provided in both urban and rural areas, and encompass, among other things, home care services (where care is provided in the individual's home) and assisted living facilities such as nursing homes, which can be either public or private. As delineated in the Coordination Reform (St. meld. nr. 47, 2008–2009), care should be provided on the lowest, effective level, thus many now receive care and treatment on the primary, community‐care service level.

High‐quality, hospital‐to‐primary healthcare care pathways, realized through good collaboration, can help safeguard care quality in nursing home settings (Grimsmo et al., 2016; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016; Spasova et al., 2018; St. meld. nr. 47, 2008–2009). Coordination between nursing home settings and other specialized services (Spasova et al., 2018) should be improved. Throughout the world, nursing homes are becoming increasingly important as end‐of‐life care facilities (Hoben et al., 2016). It is vital that those in need of end‐of‐life care (WHO, 2011), especially those with serious illness, be given high‐quality care. Mortality rates increase when generalist palliative care is provided (Lang et al., 2022), thus palliative care education for professionals in long‐term care facilities should be improved (Lida et al., 2021). Advanced palliative care resources such as palliative care support teams or palliative care consultants may reduce emergency ward visits or hospital admissions among older people (Miller et al., 2016; Spasova et al., 2018). Other various interventions, programs and models have been developed to improve the palliative care provided in nursing homes, for example, the NUrsing Homes End of Life care Program (NUHELP; Mota‐Romero, Esteban‐Burgos, et al., 2021). Developed in Spain, the aim of the NUHELP program was to improve the quality of end‐of‐life care (basic palliative care) provided in nursing homes through the modification of clinical and organizational practice and to improve care pathways between such facilities and the public healthcare system in Spain.

A stated goal in Norway is that individuals should live at home for as long as possible, thus (when appropriate) home healthcare services are offered prior to admission to a nursing home setting (Johansen & Fagerström, 2010). The concept of “aging in place”, a model whereby each older patient should be given the right treatment at the right time and in the right place, was also included as part of the Coordination Reform (Meld. St. 15, 2017–2018). Consequently, community‐care services now even encompass advanced medical treatment and palliative care, with such care often being provided in nursing home or home settings (Fjørtoft et al., 2020; NOU, 2017:16; St. meld. nr. 47, 2008–2009). The number of patients discharged from hospital settings to community care in Norway has increased statistically significantly since the reform was implemented (Fjørtoft et al., 2020; Gautun & Syse, 2017; Helsedirektoratet, 2018).

To ensure patient‐centred treatment and care that serve individual needs, as delineated in the Coordination Reform (St. meld. nr. 47, 2008–2009), consensus on what constitutes individualized, holistic care and good (inter)professional cooperation and communication (Alshammari et al., 2022; Grimsmo & Magnussen, 2015; Helsedirektoratet, 2019a, 2019b; Lang et al., 2022; NOU, 2017:16, p. 39) is needed. To facilitate good palliative care, guidelines for healthcare professionals in Norway have been presented in a government report on palliative care (Fjørtoft et al., 2020; NOU, 2017:16; St. meld. nr. 47, 2008–2009).

2. BACKGROUND

The care provided in nursing home and home settings has become increasingly broad and more complex (Alshammari et al., 2022; Halcomb et al., 2016; Lida et al., 2021). Knowledge of how to care for and treat patients with complex diseases outside of hospital settings appears to be limited (Fjørtoft et al., 2020; Lida et al., 2021; Mæhre, 2017). Researchers internationally (Alshammari et al., 2022; Cagle et al., 2016; Gómez‐Batiste et al., 2016; Lida et al., 2021; Spasova et al., 2018) and in Norway (Dale et al., 2016; Gautun & Syse, 2017; Helsedirektoratet, 2012; Slåtten et al., 2010; Torvik et al., 2008) have found that healthcare professionals in nursing home settings possess minimal palliative care competence. Globally, patients in need of end‐of‐life care receive generalist palliative care rather than professional care prior to death (Lang et al., 2022). In Norway, the provision of palliative care outside hospital settings can be considered difficult because most nurses have neither palliative qualifications nor post‐Bachelor education (Bing‐Jonsson et al., 2016; Lida et al., 2021) and healthcare professionals' resources may be limited (Bing‐Jonsson et al., 2016; Fjørtoft et al., 2020).

Good palliative care should be holistic (WHO, 2020). The concept of a “dignified death” is associated with physical and relational factors, frailty, not being a burden and patients' desire for involvement in their own lives and care (Alshammari et al., 2022; Bergdahl et al., 2011; Franklin et al., 2006; Hemberg & Bergdahl, 2019; Lang et al., 2022; Mæhre, 2017). To ensure high‐quality palliative care and treatment, healthcare professionals should possess not only professional competence but even ethical sensitivity, which includes perception and situational interpretation (Hemberg & Bergdahl, 2019). As part of an official report (NOU, 2017:16), researchers in Norway have recommended that in order to adequately care for patients in need of end‐of‐life care, healthcare professionals' competence in relation to five patient‐centred care stages should be increased: curative, life‐prolonging, symptom‐relieving, end‐of‐life and survivors' grief (NOU, 2017:16, p. 64).

All human beings can be considered vulnerable (Martinsen, 2012), and severely ill patients, who need care and strength to cope with everyday life, can be considered especially vulnerable. Healthcare professionals should be cognizant of the fact that patients' vulnerability can be either met or violated in care (Martinsen, 2012). More people in Norway today still die in hospital or nursing home settings than in their own homes (Bruvik et al., 2017), yet since the Coordination Reform the number of older people who have died after being discharged from a hospital setting has increased (Gautun & Syse, 2017). Following the reform, severely ill patients can be discharged from the hospital into community care (St. meld. nr. 47, 2008–2009) and can receive care at home or in nursing home settings (Bruvik et al., 2017). To meet such changes, nursing home settings now include advanced care wards where, for example, palliative care is provided (St. meld. nr. 47, 2008–2009).

In Norway, the ideal of coordinated healthcare as delineated in the Coordination Reform, seen as continuity and satisfactory patient care pathways, has not been achieved (Riksrevisjonen, 2016). Despite increased responsibilities, those providing care in nursing home and home settings in Norway often have limited resources (Dale et al., 2016; Lida et al., 2021) and lack knowledge (Gautun & Syse, 2017; Riksrevisjonen, 2016). Prior to the Coordination Reform, patients in need of end‐of‐life care were cared for on intensive care and palliative care wards by specially trained nurses in hospital settings. Following the Coordination Reform, many of these patient groups are cared for by healthcare professionals in community care. The care being provided on the community‐care level in nursing home settings is somewhat limited (Riksrevisjonen, 2016), which has consequences for all parties involved (patients, relatives, nurses and ward managers).

Reforms such as the Coordination Reform have been introduced as a solution to budget deficits and to make healthcare services more efficient. While potentially positive on the macro‐level, experiences on micro‐level, where work is carried out, may be somewhat less positive. To increase understanding on the effects of the Coordination Reform, we sought to explore how patients, relatives and nurses experience palliative care following the reorganization of healthcare services in Norway.

2.1. Theoretical perspective

The theoretical perspective is based on the theory of caritative caring (Eriksson, 2006, 2018). Love, mercy and compassion form the foundation of caritative caring and are essential for alleviating suffering and enhancing health and life (Bergbom et al., 2021; Eriksson, 2018; Lindström et al., 2018). The caritas motive comprises the fundamental core of caring and entails a genuine willingness to take responsibility and sacrifice something for the other in love, and the dignity of the human being is central (Eriksson, 2018; Lindström et al., 2018). Each human being simultaneously desires to be unique and belong to a communion, and the suffering human being's longing for love can be fulfilled through the caring communion. Consequently, the caring communion comprises a source of strength and meaning.

In the patient encounter, nurses can create a caring communion by being involved and being a co‐actor in the drama of suffering, thereby providing support (Thorkildsen et al., 2012). This entails true engagement, showing interest in the patient and treating the patient as being important and deserving of attention and respect (Bergbom et al., 2021). This genuine effort to be with the other can alleviate the patient's suffering (Eriksson, 2006). In the caring act, the patient is invited to take part in deep communion with the nurse (Lindström et al., 2018). When love comes forth in a genuine caring communion, the suffering human being can begin to heal (Thorkildsen et al., 2012). Caritative caring can, therefore, enable patients' becoming in health and help them experience harmony and meaning in life (Lindström et al., 2018).

2.2. Aim

The aim was to explore patients', relatives' and nurses' experiences of palliative care on an advanced care ward in a nursing home setting after implementation of the Coordination Reform in Norway.

2.3. Research questions

The research questions were: (1) How do patients in need of end‐of‐life care experience their everyday life in a nursing home setting?, (2) What are relatives' and nurses' experiences of the palliative care provided for patients in need of end‐of‐life care in a nursing home setting?

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Design and method

A secondary analysis of qualitative interviews (Long‐Sutehall et al., 2010) in a nursing home setting in Norway was undertaken. The interviews had not previously been analysed in relation to each other; therefore, a case study design with a cross‐case approach was employed (Yin, 2008). The first author conducted interviews with 19 participants. Two patients become in a terminal end‐ of life care and could not been interviewed, and not their relatives ever. All patients were severely ill patients in end‐of‐life palliative care, three women and two men aged 61–76. Six participants were relatives (sisters, daughters, sons), four women and two men. Eight participants were nurses, all women: two were department leaders. Each interview was audio‐recorded, transcribed verbatim, anonymized (patient [P], 1–5; relatives, [R] 1–6; nurses [N], 1–8) and translated into English. The interviews were unstructured, with only one introductory question being asked: How do you experience your everyday life in the nursing home? Follow‐up questions were formulated based on participant responses. To protect participant identity, the decision was made to not include disclosures considered to be sensitive in the quotations used to represent the data material.

3.2. Context and data collection

The study was conducted in a nursing home setting in Norway comprised of four wards. In the setting, advanced care was provided to patients in need of advanced medical treatment and care, whether somatic illness, dementia, etc. Those receiving advanced care had predominantly been transferred from a specialist healthcare setting, often a specialized intensive care or palliative ward.

The first author gave potential nurse participants information about the study during a staff meeting at the included setting, and those nurses interested in participating in the study were given a prepaid postage envelope and asked to contact the first author. An information letter was distributed to potential patient participants, specifically severely ill patients without dementia receiving advanced care, and patients were asked to share the information letter with relatives. Patients and relatives interested in participating in the study were asked to contact the first author. Upon request, more information about the study was given to the potential patient participants.

Those patients interested in participating in the study were informed that they could refuse to participate at any time without consequences for their treatment and care. Severely ill patients may be given medication such as painkillers that may affect alertness, which was undesirable. The responsible nurse and doctor for each patient were contacted prior to the start of each interview, and nurses were asked to ensure that patients were not in a lethargic state when the interviews took place. All relatives were informed about patient participation.

Prior to the start of interviews, the condition of three patients who had indicated a willingness to participate in the study deteriorated abruptly, consequently neither they nor their relatives were included in the study. All of the patients included in the study had previous experience of care on a palliative ward in a hospital setting and had been receiving care in the included setting for some time and could thus reflect on the differences in practice seen between the two settings. All participants signed an informed consent form and were given the opportunity to participate in a desensitization process following their interviews.

The data were collected from January to October 2015 in connection with the first author's research. The first author conducted the interviews individually with each participant in rooms located in the included setting. Two patients were interviewed twice because they requested this themselves.

3.3. Analysis

Patient, relative and nurse interview data were initially analysed separately in a previous study. In this study, patterns within and across each interview were sought. As in the previous study, the data were grouped in accordance with participant category, with each group initially separately analysed: patients, then relatives, then nurses. Thereafter, the preliminary thematic codes that emerged for each group were compared. Early on, a pattern emerged indicating that all groups had experiences that related to the same phenomenon, although from different perspectives. The qualitative data analysis was influenced by Miles and Huberman (1994), encompassing “three concurrent flows of activity: data reduction, data display and conclusion drawing/verification” (1994, p.10). Accordingly, to enhance understanding of the data, data triangulation (Miles et al., 2013) of the data (patients', relatives' and nurses' experiences), specifically the themes that were identified, was used. For an overview of the data analysis process, see Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Overview of the data analysis process.

| Data analysis stages |

|---|

|

3.4. Ethics

The ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013) were followed throughout the course of the study. Approval for the study was granted by the Regional Ethics Committee (project no. 2012/1720) and the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (reference no. 30812).

4. RESULTS

The three main themes generated from the analysis were: “Desire for engaging palliative care in a hopeless and lonely situation”, “Patients seeking understanding of end‐of‐life care in an unfamiliar setting” and “Absence of sufficient palliative care and competence creates insecurity”. The overall theme generated from the analysis was: “Being in an unfamiliar and uncaring culture leaves end‐of‐life patients in desperate need of holistic, person‐centered and co‐creative care”. Participant quotations are included below to illustrate the data in relation to the study results.

4.1. Desire for engaging palliative care in a hopeless and lonely situation

The patients, relatives and nurses alike all described a situation where nurses were uncertain whether they could cope. Due to the nurses' heavy workload and lack of time, it was vital that patients had relatives who were involved and able to assist in the care process. All of the patients needed care and support because of chronic disease and wanted to live according to own wishes for good care. None of the participants were satisfied with the shortage of healthcare professionals:

There are few [healthcare professionals] at work. I wish they had more time to stay with me. On the palliative ward they had time… I hope I get another stay there… Family means everything to me. (P1)

Experiencing a lack of healthcare resources, the patients were grateful to have relatives on site who could provide daily support. The nurses were also grateful that relatives could provide support and sought to create relationships based on mutual trust and respect. According to several relatives, patients did not want to be a burden and instead sought to cope with minimal help:

I know that when [my] mom calls for help – then it's urgent…I both see and hear that the nurses are in a hurry… We have arranged it so that one of us visits her every day. But we cannot manage this over a long [period of] time. (R1)

Some relatives noted that patients in need of mechanical respiratory ventilation were at times required to manage their ventilation alone, with relatives experiencing a sense of insecurity and that more healthcare professional were needed on site. Although demanding, many relatives stated that they organized themselves in “shifts” to help. In accordance with the principles of beneficence and non‐maleficence, the nurses revealed that they valued safety, sought to avoid risk and harm, and sought to help patients cope, regardless of illness or functional impairment. The nurses even experienced that when their workload was unmanageable that relatives could provide useful support:

Now …patients are admitted to the ward before we have time to gain the necessary competence. … We become unsafe because maybe we cannot help the patients… I miss more cooperation. We've written complaints, but so far nothing has changed. (N1)

The nurses stated that predictability in their work was lacking, which was linked to problems with collaboration, organization and planning, and a lack of medical knowledge and care. Nonetheless, we discerned that the nurses themselves did not sufficiently communicate that more competence and collaboration were needed.

4.2. Patients seeking understanding of end‐of‐life care in an unfamiliar setting

To realize good care, it is essential that full understanding of the complexity of care that nurses should perform and patients should receive be understood, alongside any other potential challenges to the provision of good care. To participate in decision‐making, patients must be given clear and straightforward information. However, severely ill patients need especial attention because they can be too ill to “challenge” the decisions being made. Respecting patient autonomy and thus dignity requires consideration of patient wishes and seeking consensus while allowing patients to choose among possible solutions without “pressure”. Being discharged to an unfamiliar setting with new healthcare professionals and a different culture can be distressing for patients in need of end‐of‐life care. As one patient revealed:

I felt weak and my legs barely supported me. But I was told to pack my things at full speed. … I, but also my relatives, had asked if I could spend a few more days in the hospital. But when the medical treatment had ended there was no room for me at the hospital. What I think about that does not seem to matter. (P2)

Several patients expressed displeasure over that costs and benefits seemed to be more important than individual care and treatment. Some relatives stated that it was difficult when agreed‐upon decisions were reversed or changed and perceived that economic factors were given greater consideration than patient needs and desires.

The relatives experienced that it was upsetting when their and/or patients' views appeared to not be taken seriously. For example, they expressed concern when their loved ones were moved to a new setting without sufficient time to adjust to the decision:

Now it's always about economics about reducing the number of days [in the hospital]. That … patients be shuttled back and forth from the hospital to the nursing home because there were complications that the nurses in the nursing home could not manage was not taken into consideration. It is not dignified… care. (R3)

Doubts and disagreement can give rise to ethical challenges. Although patient autonomy and efficient care are promoted in public documents in Norway, we found indications that cost‐effectiveness was more important than the provision of good and dignified care.

The nurses experienced working on a ward with multimorbid end‐of‐life patients in need of advanced care to be challenging and described that they needed to provide end‐of‐life care despite lacking sufficient resources and competence:

We're getting new patient groups admitted now. Several are admitted from the hospital, and many after a longer stay in an intensive care ward. Many have medical equipment that should be operated, and that we have little knowledge of… It does not help that we speak up about that the patient cannot be admitted to us. When there are available rooms, we must just take the patients… It is a big responsibility. (N2)

The nurses revealed that they experienced a sense of insecurity related to their competency in providing palliative care. They furthermore noted that while opportunities to improve their professional competence were organized, such were typically held at a different setting and were considered inconvenient. The nurses even noted that poor information flow from hospitals could lead to inadequate coordination and uncertainty about care pathways. The absence of sufficient palliative care and competence created a sense of insecurity for all involved, patients, relatives and nurses alike.

4.3. Absence of sufficient palliative care and competence creates insecurity

The patients who were transferred to the included setting were more severely ill than previously admitted patients and of the patient participants in this study, four out of five were end‐of‐life patients with cancer. All were vulnerable and in need of good caritative caring:

I've tried to maintain my spirits, but it has not been as easy all the time. The nurses are in a hurry. … I do not think that the care they have for patients like me in this nursing home is good enough. Knowing that help can fail … scares me. (P3)

The patients described how not knowing whether they would receive help or if help would arrive in time could lead to a sense of insecurity. Patients readmitted to the hospital, of whom there were several, stated that their confidence in the nursing home healthcare professionals' abilities had been weakened. The patients wanted to show that they could cope with their situation. Both patients and relatives said that they were worried about the shortage of healthcare professionals and lack of palliative care competence. The relatives were of the opinion that better care should be given:

I remember well one night when my sister had difficulties breathing, and the night nurse did not understand and just gave her more pain medication. In the morning she was so poorly that she had to be readmitted to the hospital. We understand that the nurses are in a hurry and that unforeseen problems can arise that require prioritization. But what if it happens again? (R3)

The relatives described how they wanted to support their loved ones but could not “move in to” the nursing home. The nurses noted that they could register complaints about the shortage of healthcare professionals and lack of palliative care competence but that changes were never introduced:

Many [staff] have left. We get sicker patients admitted, and many of them die a short while after they are admitted to the ward. To meet so many people with serious illness, and not know whether you have sufficient competence is challenging. As it is now there can be two of us who have received training in a new procedure at the hospital. (N3)

The nurses stated that they while wished to do the right thing the reality is that they are unsure whether they have the necessary knowledge and competency to care for patients in need of advanced care. They, therefore, experienced that their actions could lead to moral and professional dilemmas.

4.4. The overall theme: Being in an unfamiliar and uncaring culture leaves end‐of‐life patients in desperate need of holistic, person‐centred and co‐creative care

As seen in the overall theme, the included patients, relatives and nurses all expressed concern about the poor palliative care being received and/or given. This indicates the existence of a care culture where patients needed more help than they could receive. Before admission to the included setting, the patients had experienced good palliative care and anticipated that they would experience the same level of care in the nursing home setting. However, this did not occur and the patients instead primarily experienced anxiety, sadness, fear, loneliness and a longing for the past. They needed more help than they could receive and generally had to cope alone or with relatives' support. Both the patients and relatives longed for a more dignified care but, because of the shortage of healthcare professionals and lack of palliative care competence, experienced a sense of insecurity related to whether help would be received or arrive in time. The patients and relatives stated that the advanced care provided needed to be improved, at the very least for future patients and relatives. Many patients felt a sense of insecurity during the late palliative phase. All of the participants (patients, relatives and nurses alike) experienced existential anxiety and fears and worries about the future. For an overview of the study results, see Figure 1 below.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the study results.

5. DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to explore patients', relatives' and nurses' experiences of palliative care on an advanced care ward in a nursing home setting after implementation of the Coordination Reform in Norway (St. meld. nr. 47, 2008–2009). From the results, we saw that patients, relatives and nurses can experience a lack of good palliative care from different perspectives. All sought, longed for and hoped for a holistic, person‐centred and co‐creative palliative care. The severely ill and vulnerable patients included in this study longed for understanding and shelter in the unfamiliar and uncaring culture that existed in the nursing home setting they were transferred to. Their experiences do not align with the principles delineated in the theory of caritative caring (Eriksson, 2018; Lindström et al., 2018), in which it is highlighted that love and compassion are needed to alleviate the human being's suffering and enhance health. The patients articulated that although the situation gave rise to feelings of hopelessness and loneliness, their hope and longing for good and engaging palliative care continued. They sought security and a trusting care relationship. We interpreted this as the patients longing for a caring communion with healthcare professionals, where they are met with compassion and love (cf. Thorkildsen et al., 2012). One could argue that the patients, relatives and nurses were all suffering and in need of protection. Central to experiencing a becoming in health is healthcare professionals' showing of genuine compassion and the protection of the human being's vulnerability through the preservation of dignity and alleviation of suffering (Eriksson, 2018; Lindström et al., 2018). However, as seen at the time of data collection, the resources and external conditions at the nursing home included in this study were not conducive to the provision of good palliative care.

In this study, all participants were found to experience existential anxiety and fears and worries about the future. It is important in a palliative care context that existential issues be addressed (Hemberg & Bergdahl, 2020a; Miller et al., 2016). Moreover, healthcare professionals should be taught during training to strive to provide all patients with compassionate and dignified care (caritative caring, cf. Bergbom et al., 2021) and even provide a “safe haven” for patients, especially when older patients and/or those in need of end‐of‐life care are admitted to a new and unfamiliar setting.

The experiences of the patients, relatives and nurses in this study indicated that a gap exists between health policy strategies and the actual framework whereby healthcare professionals in nursing home settings provide palliative care in Norway. Caring for older patients in need of end‐of‐life care is complex and should be performed by professionals with palliative competence or, at a minimum, other healthcare professional should be supported by such professionals in a consultancy and/or mentor capacity. There are many different external and internal factors and elements that might hinder the performance of good palliative care. Caring requires a link between “knowing that” and “knowing what”, knowledge of how to care and adequate task distribution. Caring also encompasses those responsible for care on the macro‐ and meso‐levels and those performing care work on the micro‐level.

Several patients in the nursing home setting included in this study had multimorbidity and needed close monitoring by nurses with specialized knowledge of severely ill patients and palliative care. From our results, we discerned that such care was difficult to realize. We furthermore note that high‐quality care cannot be provided without more healthcare professionals and palliative care competence, which is in line with other previous study findings (Bergerød et al., 2018; Berntsen et al., 2019; Fjørtoft et al., 2020; Fosse et al., 2014; Karlsson et al., 2010; Lida et al., 2021; Martinsen, 2021; Meld. St. 26, 2014–2015; Meld. St. 9, 2019–2020; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016; Pivodic et al., 2018; Schiøtz et al., 2016). “Incompetent care is not only a technical problem, but a moral one” (Tronto, 1998, p. 17).

Care judgement quality is linked to different external and internal elements that are in turn linked to care practice. Based on our results, we find that there is poor understanding of what is needed to provide adequate care in the palliative phase in a nursing home setting in Norway. For example, resources such as an on‐site pharmacy and the regular presence of a doctor or chaplain are recommended (Danielsen et al., 2017; Meld. St. 9, 2019–2020) but were not available at the setting included in this study.

Most of the included patients had experience of in‐hospital palliative care wards and many hoped to return. Martinsen (2021) argues that there are two forms of hope, hoping for something and being hopeful. The patients in this study demonstrated both kinds of hope. Their hope of (re)admission to an in‐hospital palliative care ward was about gaining “strength to bear the pain, the suffering, but also possibilities […] to be able to share sorrow and longing, hope and hopelessness, as well as joy and gratitude” (Martinsen, 2021, p. 176; authors' own translation).

As seen in both official Norwegian guidelines and international findings, the mixing in wards of advanced palliative care patients and patients with cognitive impairment is not recommended (Danielsen et al., 2017; Meld. St. 9, 2019–2020; Roach et al., 2022). The organization of advanced care at the setting included in the study, where patients with cognitive impairment could mix with those needing palliative care, made the included patients and relatives anxious and insecure. Some included patients described feeling anxious when “cries” from other patients could be heard and several were afraid that patients with cognitive impairment would bother them, due to low staffing levels. Both sufficient palliative care knowledge and patient privacy are important (Lida et al., 2021; Midtbust et al., 2018).

From the results we saw that there was often little time to prepare for transfer to the nursing home setting. There was no opportunity for person‐centred or co‐creative considerations (cf. Hemberg & Bergdahl, 2019) because patients were generally told of the transfer the same day their treatment ended. Many of the included patients expressed the desire to spend a few more days in the hospital. Of these, some were ignored until their relatives intervened (“and what about patients without family,” as one relative stated) while others quietly accepted the decision (“That's the way healthcare is, and I just have to accept it”). We perceived that these patients were “shuttled” to a new unfamiliar setting at the end of their life; a place without the same palliative care competence previously provided in specialized care. Several patients and relatives described broken promises; although desired, patients were not quickly readmitted to the hospital for further palliative care, which could make it difficult to maintain hope. These findings are in line with other studies; sufficient time is needed to adjust to decisions (Ahlström et al., 2022; Heggestad et al., 2020; Hemberg & Bergdahl, 2020a) and relatives' involvement in patient care is necessary (Hemberg & Bergdahl, 2020a, 2020b; Schiøtz et al., 2016).

In Norway, an official recommendation has been made to increase the involvement of relatives in patient care in order to improve care (St. meld. nr. 47, 2008–2009). Thus while there is currently no legal obligation for relatives to play an active role in patient care, it is desired. Researchers in other studies have found that relatives of end‐of‐life patients can often be perceived (and treated) as an “extension” of professional care (Ahlström et al., 2022; Vik, 2018). We saw that the relatives in this study were also highly involved in the care realized in the included nursing home setting. For example, the relatives revealed that they elected to perform certain care tasks themselves and could even organize themselves in “shifts”. The relatives moreover described a sense of insecurity, linked to, among other things, the shortage of healthcare professionals and lack of palliative care competence. This is in line with other studies, where the realization of holistic patient care is contingent on the involvement of relatives in care (Ahlström et al., 2022; Fjørtoft et al., 2020; Heggestad et al., 2020; Hemberg & Bergdahl, 2020a; Midtbust et al., 2018).

From the results, we discerned ethical challenges related to the care provided in the included setting. The patients, relatives and nurses alike experienced that the care provided in the included setting was inadequate. Per Norwegian legislation, multimorbid patients in Norway must receive care from a specialist healthcare outpatient team when discharged to community care (cf. Chapter 6.5, St. meld. nr. 47, 2008–2009). Also per legislation is that healthcare professionals in Norway may only perform work that is considered equivalent to their qualifications and are required to obtain assistance from or refer patients to sufficiently qualified professionals as needed (Helsedirektoratet, 2019a, 2019b; Meld. St. 9, 2019–2020). Patients discharged from an in‐hospital palliative care ward or who need mechanical ventilation should be closely monitored. However, at the setting included in this study, this did not occur. Instead, both the patients and relatives noted that patients in need of mechanical ventilation were not continuously monitored and needed to call for help if there were problems, which resulted in a sense of insecurity.

The nurses included in this study perceived their work situation to be not only physically but even mentally demanding and revealed a sense of insecurity about their ability to provide quality palliative care. They nevertheless experienced a lack of organizational understanding when requests for more resources were made. For example, opportunities to further professional competence were organized off‐site despite low staffing levels making attendance difficult. Those who were able to participate in training were even tasked with demonstrating what they had learned to others at the included setting. As one nurse participant revealed, many staff had decided to leave. Nurses may be reluctant to go to work if they have insufficient professional competence (Heggestad et al., 2020; Lida et al., 2021) or may be uneasy when unable to gain new knowledge and thus become better nurses (Bergdahl et al., 2011; Carpenter & Ersek, 2022). Additionally, the patients, relatives and nurses alike described concerns about hospital readmissions. Norway has the highest hospital readmission rate of the Nordic countries (Gautun & Syse, 2017; Grimsmo & Magnussen, 2015, p. 46). There is strong evidence that good in‐hospital preparation before discharge (Grimsmo et al., 2016) and the structured reception of patients in primary healthcare settings reduce readmissions (Garåsen et al., 2008; Mota‐Romero, Tallón‐Martín, et al., 2021).

Despite the goals of the Coordination Reform, Norwegian healthcare is still fragmented and complex (Berntsen et al., 2019). Strategies and action plans to improve competence and management in healthcare (Helsedirektoratet, 2012; Meld. St. 9, 2019–2020) have been implemented but, for example, patient pathways for older and/or chronic patients remain challenging (Danielsen et al., 2017). “What is most important for cooperation is not the various ideals of treatment and care in the health professions, but how care pathways are organized” (Vik, 2018, p. 127). In line with the results seen in this study, greater focus on inter‐setting transfers and the considered inclusion of those community‐care settings involved in the transfer process are needed (Meld. St. 26, 2014–2015). Enhancing inter‐setting transfers and more resources has been shown to reduce mortality and readmissions and lead to shorter hospital stays (Helsedirektoratet, 2018; Lang et al., 2022; Tortajada et al., 2017). Patient transfers must be enhanced to allow severely ill patients to experience being at the centre of healthcare and receiving the right treatment, at the right time and in the right place until their final heartbeat (cf. Martinsen, 2021). Furthermore, as recommended in national guidelines, dedicated wards in, for example, nursing home settings should be established for patients with palliative cancer (Helsedirektoratet, 2019a, 2019b). The courage and strength to oppose a rigid system should not be expected of severely ill patients in palliative care and their relatives.

5.1. Limitations

We performed a qualitative secondary analysis of data to explore aspects of healthcare (Long‐Sutehall et al., 2010; Polit & Beck, 2021). A case study design including a cross‐case approach to analysis, involving an iterative process between the authors, was used to enable new understanding and thereby qualitative rigour.

The data were collected before the COVID‐19 pandemic. Also, a National Health and Hospital Plan 2020–2023 (Meld. St. 7, 2019–2020) has been developed since data collection, in which a new direction and framework for the interaction between specialist health and community‐care services has been introduced, with the aim to, among other things, increase user participation and thereby patient‐centred care. Therefore, a different result might be seen if new data were collected from a different setting and/or the same setting, post‐pandemic. Nevertheless, we maintain that the data were rich and provided a trustworthy depiction of the phenomenon being explored.

One limitation may be the size of the participant sample. However, the data were considered to answer the research questions and three different participant perspectives (patients', relatives' and nurses') were incorporated, which is somewhat unique in research (Alvsvåg, 2010). Another limitation may be that the findings are based on a secondary analysis of qualitative interviews. Secondary data analysis allows the exploration of a sensitive research topic, as seen in this study.

Trustworthiness was ensured and seen as rich data taken from three different groups' perspectives, from which a nuanced depiction of the topic was yielded. Quality was ensured because the first researcher took part in the original study, which increases secondary data analysis dataset quality (Elliot, 2015). Rigour was even ensured through the inclusion of a research team member from the original study (Ruggiano & Perry, 2019). The re‐analysation of own data can be beneficial; emotional distance can make researchers more objective and less emotionally invested in the data (Ruggiano & Perry, 2019). The needs of the secondary data analysis were in line with the original study and sample. Interviews with severely ill and older patients in need of end‐of‐life care, their relatives and nurses from the same nursing home setting can be seen as both a strength and a limitation. The use of data triangulation, that is the analysis of three perspectives to obtain a result, is a strength.

Many of the included patients and relatives considered the nursing home to be a final resting place before death. They hoped for high‐quality and dignified care but instead experienced a shortage of healthcare professionals and lack of palliative care competence. We saw that there are potential challenges involved in palliative care when decisions are made on the macro‐ and meso‐levels, especially when those on the micro‐level are neither consulted nor have the necessary competence.

In the face of common, tacit, system‐based understanding, the included patients and relatives were not consulted and were left alone, afraid, sad and anxious in an unfamiliar and uncaring culture. None of the study participants were listened to when they sought improved care or better treatment. A shortage of healthcare professionals, high staff turnover and limited resources were further problems.

6. CONCLUSION

The patients and relatives included in this study experienced an uncaring culture, limited resources and a lack of palliative care competence, which is in direct contrast to that which is delineated in directives, guidelines and recommendations. Our findings reveal the need for policymakers to be more aware of the challenges that may arise when healthcare reforms are implemented, for example divergent institutional logics that can constitute a hinder for the provision of quality care (Olsen & Solstad, 2020). Following the Coordination Reform, patients who are discharged from hospital to nursing homes settings are more ill, therefore, staffing resources for nursing home settings should be increased (Bruvik et al., 2017). Furthermore, healthcare professionals in all non‐hospital settings should have the competency and knowledge to care for and treat patients with complex diseases (Lang et al., 2022; Lida et al., 2021). The enabling of continuous and common care pathways, improved teamwork, co‐creative care (Hemberg & Bergdahl, 2019, 2020a, 2020b) and increased professional palliative competence can improve patients' quality of life, relatives' well‐being and nurses' work‐related ethical stress in nursing home settings. Advanced palliative care resources in nursing home settings, for example palliative care support teams, may reduce hospital (re)admissions (Miller et al., 2016). Interventions such as the NUHELP program, thorough which healthcare professionals can improve their palliative care competence, can improve the quality of the end‐of‐life care provided in nursing home settings (Mota‐Romero, Esteban‐Burgos, et al., 2021). The provision of high‐quality end‐of‐life care to severely ill patients must become a priority in Norway. An evaluation of healthcare professionals' palliative competence in non‐hospital settings and whether specialized, in‐hospital palliative wards should be established is recommended. As mentioned previously, the data for this study were collected prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Therefore, given the gravity of the situation even prior to the pandemic, it is essential that further research on the palliative care provided in nursing home settings in Norway be undertaken, so as to yield increased insight into the current situation.

Increased focus on how safe and dignified palliative care can be realized regardless of setting should be included in future research. Also, the role that care assistants play in the provision of care and patients', relatives' and nurses' perspectives on palliative care in end‐of‐life care settings or home environments should be included in future research. Lastly, it is even recommended that a review of the impact that the newly introduced National Health and Hospital Plan 2020–2023 (Meld. St. 7, 2019–2020) has had on the healthcare system in Norway be undertaken.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kjersti Sunde Mæhre contributed to the study conception and design, data analysis, discussion and drafted the manuscript at all stages. Elisabeth Bergdahl contributed to the study design, data analysis and discussion. Jessica Hemberg contributed to the theoretical perspective, data analysis, discussion and provided critical reflections.

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria [recommended by the ICMJE (http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/)]:

Substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data;

Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank the study participants for their contributions.

Mæhre, K. S. , Bergdahl, E. , & Hemberg, J. (2023). Patients', relatives' and nurses' experiences of palliative care on an advanced care ward in a nursing home setting in Norway. Nursing Open, 10, 2464–2476. 10.1002/nop2.1503

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- Ahlström, G. , Rosén, H. , & Persson, E. I. (2022). Quality of life among next of kin of frail older people in nursing homes: An interview study after an educational intervention concerning palliative care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2648. 10.3390/ijerph19052648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshammari, F. , Sim, J. , Lapkin, S. , & Stephens, M. (2022). Registered nurses' knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about end‐of‐life care in non‐specialist palliative care settings: A mixed studies review. Nurse Education in Practice, 59, e103294. 10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvsvåg, H. (2010). På sporet av et dannet helsevesen. Om nære pårørende og pasienters møte med helsevesenet [On the trail of a civilized healthcare system. About close relatives' and patients' meetings with the healthcare system]. Akribe. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, C. , Halcomb, E. , Peters, K. , & Brown, A. (2017). Exploring why nurses transition from acute care to primary health care employment. Applied Nursing Research, 38, 83–87. 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergbom, I. , Nåden, D. , & Nyström, L. (2021). Katie Eriksson's caring theories. Part 1. The caritative caring theory, the multidimensional health theory and the theory of human suffering. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 36(3), 782–790. 10.1111/scs.13036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergerød, I. J. , Gilje, B. , Braut, G. S. , & Wiig, S. (2018). Next‐of‐kin involvement in improving hospital cancer care quality and safety – a qualitative cross‐case study as basis for theory development. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 324. 10.1186/s12913-018-3141-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergdahl, E. , Benzein, E. , Ternestedt, B. M. , & Andershed, B. (2011). Development of nurses' abilities to reflect on how to create good caring relationships with patients in palliative care: An action research approach. Nursing Inquiry, 18(2), 111–122. 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen, G. K. R. , Dalbakk, M. , Hurley, J. S. , Bergmo, T. , Solbakken, B. , Spansvoll, L. , Bellika, J. G. , Skrøvseth, S. O. , Brattland, T. , & Rumpsfeld, M. (2019). Person‐centred, integrated and pro‐active care for multimorbid elderly with advanced care needs: A propensity score‐matched controlled trial. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 682. 10.1186/s12913-019-4397-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing‐Jonsson, P. C. , Hofoss, D. , Kirkevold, M. , Bjørk, I. T. , & Foss, C. (2016). Sufficient competence in community elderly care? Results from a competence measurement of nursing staff. BMC Nursing, 15, 5. 10.1186/s12912-016-0124-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruvik, F. , Drageset, J. , & Abrahamsen, J. F. (2017). Fra sykehus til sykehjem, hva samhandlingsreformen har ført til [from hospitals to nursing homes – The consequences of the care coordination reform]. Sykepleien Forskning, e60613. 10.4220/sykepleienf.2017.60613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cagle, J. G. , Unroe, K. T. , Bunting, M. , Bernard, B. L. , & Miller, S. (2016). Caring for dying patients in the nursing home: Voices from frontline nursing home staff. Journal of Pain Symptom Management, 53(2), 198–207. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, J. G. , & Ersek, M. (2022). Developing and implementing a novel program to prepare nursing home‐based geriatric nurse practitioners in primary palliative care. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 34(1), 142–152. 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale, B. , Folkestad, B. , Førland, O. , & Hellesø, R. (2016). Er tjenestene fortsatt “på strekk”?: om utviklingstrekk i helse‐ og omsorgstjenestene i kommunene fra 2003 til 2015 . [Are services still “being stretched”? On developments in municipal health and care services from 2003 to 2015]. 10.13140/RG.2.1.5067.4960 [DOI]

- Danielsen, K. K. , Nilsen, E. R. , & Fredwall, T. E. (2017). Pasientforløp for eldre med kronisk sykdom: En oppsummering av kunnskap [Patient pathways for elderly people with chronic illnesses: A summary of knowledge]. Centre for Care Research. https://omsorgsforskning.brage.ward.no/omsorgsforskning‐xmlui/handle/11250/24444230 [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, D. (2015). Secondary data analysis. In Stage F. K. & Manning K. (Eds.), Research in the college context: Approaches and methods (2nd ed., pp. 175–184). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, K. (2006). The suffering human being. Nordic Studies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, K. (2018). Vårdvetenskap. Vetenskapen om vårdandet. Om det tidlösa i tiden [Caring science. The science about caring. About the timeless in time]. Liber. [Google Scholar]

- Fjørtoft, A.‐K. , Oksholm, T. , Delmar, C. , Førland, O. , & Alvsvåg, H. (2020). Home‐care nurses' distinctive work: A discourse analysis of what takes precedence in changing healthcare services. Nursing Inquiry, 28(1), e12375. 10.1111/nin.12375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosse, A. , Schaufel, M. A. , Ruths, S. , & Malterud, K. (2014). End‐of‐life expectations and experiences among nursing home patients and their relatives – A synthesis of qualitative studies. Patient Education and Counseling, 97(1), 3–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, L. L. , Ternestedt, B. M. , & Nordenfelt, L. (2006). Views on dignity of elderly nursing home residents. Nursing Ethics, 13(2), 130–146. 10.1191/0969733006ne851oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garåsen, H. , Windspoll, R. , & Johnsen, R. (2008). Long‐term patients' outcomes after intermediate care at a community hospital for elderly patients: 12‐month follow‐up of a randomized controlled trial. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 36(2), 197–204. 10.1177/14034948080889685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautun, H. , & Syse, A. (2017). Earlier hospital discharge: A challenge for Norwegian municipalities. Nordic Journal of Social Research, 8, 1–17. 10.7577/njsr.2204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez‐Batiste, X. , Murray, S. A. , Thomas, K. , Engels, Y. , Dees, M. , & Costantini, M. (2016). Comprehensive and integrated palliative care for people with advanced chronic conditions: An update from several European initiatives and recommendation for policy. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 53(3), 509–517. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsmo, A. , Løhre, A. , Røssad, T. , Gjerde, I. , Heiberg, I. , & Steinsbakk, A. (2016). Helhetlige pasientforløp ‐ gjennomføring i primærhelsetjenesten [integrated clinical pathways: Implementation in primary healthcare services]. Tidsskrift for Omsorgsforskning, 2(2), 78–87. 10.18261/issn.2387-5984-2016-02-02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsmo, A. , & Magnussen, J. (2015). Norsk samhandlingsreform i et internasjonalt perspektiv [Norwegian coordination reform from an international perspective]. Commissioned by EVASAM, Research Council of Norway. Department of Public Health and Nursing, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Halcomb, E. , Stephens, M. , Bryce, J. , Foley, E. , & Ashley, C. (2016). Nursing competency standards in primary health care: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(9–10), 1193–1205. 10.1111/jocn.13224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heggestad, A. K. T. , Magelsen, M. , Pedersen, R. , & Gjerberg, E. (2020). Ethical challenges in home‐based care: A systematic literature review. Nursing Ethics, 28(5), 628–644. 10.1177/0969733020968859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellesø, R. , Larsen, L. S. , Obstfelder, A. , & Osvold, N. (2016). Hva er sykepleie? [What is nursing?]. Sykepleien Forskning, (8), 64. 10.4220/Sykepleiens.2016.5849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helsedirektoratet [Directorate of Health] . (2012). Behovet for spesialisert kompetanse i helsetjenesten. En status‐, trend‐ og behovsanalyse fram mot 2030 [the need for specialized expertise in the health services. A status, trends and needs analysis toward 2030]. Helsedirektoratet [Directorate of Health]. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/nasjonalt‐personellbilde‐personell‐og‐kompetansesituasjonen‐i‐helse‐og‐omsorgstjenestene/Nasjonalt%20personellbi [Google Scholar]

- Helsedirektoratet [Directorate of Health] . (2018). Liggedager og reinnleggelser for utskrivningsklare pasienter 2012–2017 [Bed days and readmissions for ready‐to‐discharge patients 2012–2017]. Analysenotat 5/2018. Samdata kommune. Helsedirektoratet [Directorate of Health]. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/liggedager‐og‐reinnleggelser‐for‐utskrivningsklare‐pasienter‐2012‐17/2018‐5%20Liggedager%20og%20reinnleggelse [Google Scholar]

- Helsedirektoratet [Directorate of Health] . (2019a). Nasjonalt handlingsprogram med retningslinjer for palliasjon i kreftomsorgen [national action program with guidelines for palliation in cancer care]. Helsedirektoratet [Directorate of Health]. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/palliasjon‐i‐kreftomsorgen‐handlingsprogram [Google Scholar]

- Helsedirektoratet [Directorate of Health] . (2019b). Nasjonalt handlingsprogram for palliasjon i kreftomsorgen [national action program for palliation in cancer care]. Helsedirektoratet [Directorate of Health]. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/palliasjon‐i‐kreftomsorgen‐handlingsprogram/Palliasjon%20i%20kreftomsorgen%20%E2%80%93%20Nasjonalt%20handlingsprogram [Google Scholar]

- Hemberg, J. , & Bergdahl, E. (2019). Cocreation as a caring phenomenon. Holistic Nursing Practice, 33(5), 273–284. 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemberg, J. , & Bergdahl, E. (2020a). Dealing with ethical and existential issues at end of life through co‐creation. Nursing Ethics, 27(4), 1012–1031. 10.1177/0969733019874496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemberg, J. , & Bergdahl, E. (2020b). Ethical sensitivity and perceptiveness in palliative home care through co‐creation. Nursing Ethics, 27(2), 446–460. 10.1177/0969733019849464.r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoben, M. , Chamberlain, S. A. , Knopp‐Sihota, J. A. , Poss, J. W. , Thompson, G. N. , & Estabrooks, C. A. (2016). Impact of symptoms and care practices on nursing home residents at the end of life: A rating by front‐line care providers. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17(2), 155–161. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, E. , & Fagerström, L. (2010). An investigation of the role nurses play in Norwegian home care. British Journal of Community Nursing, 15(10), 497–502. 10.12968/bjcn.2010.15.10.78742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, M. , Roxberg, A. , da Silva, A. B. , & Berggren, I. (2010). Community nurses' experiences of ethical dilemmas in palliative care: A Swedish study. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 16(5), 224–231. 10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.5.48143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, A. , Frankus, E. , & Heimerl, K. (2022). The perspective of professional caregivers working in generalist palliative care on ‘good dying’: An integrative review. Social Science & Medicine, 293, e114647. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lida, K. , Ryan, A. , Hasson, F. , Payne, S. , & McIlfatrick, S. (2021). Palliative and end‐of‐life educational interventions for staff working in long‐term care facilities: An integrative review of the literature. Intern Journal of Older People Nursing, 16(1), e12347. 10.1111/opn.12347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindström, U. Å. , Nyström, L. L. , Zetterlund, J. E. , & Eriksson, K. (2018). Theory of caritative caring. In Alligood M. R. (Ed.), Nursing theorists and their work (9th ed., pp. 448–461). Elsevier – Health Sciences Division. [Google Scholar]

- Long‐Sutehall, T. , Sque, M. , & Addington‐Hall, J. (2010). Secondary analysis of qualitative data: A valuable method for exploring sensitive issues with an elusive population? Journal of Research in Nursing, 16(4), 335–344. 10.1177/1744987110381553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mæhre, K. S. (2017). «Vi må ha hjelp!» pasienter, pårørende og sykepleiere sine erfaringer fra en forsterket sykehjemsavdeling etter Samhandlingsreformen [“We need help!” Patients, relatives and nurses' experiences from an enhanced nursing home ward following the Coordination Reform]. PhD dissertation. Nord University. [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen, K. (2012). Filosofi og fortellinger om sårbarhet [Philosophy and narratives of vulnerability]. Klinisk Sygepleije, 26(2). 10.18261/ISSN1903-2285-2012-02-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen, K. (2021). Langsomme pulsslag [Slow heartbeats]. Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Meld. St. 15 . (2017. –2018). Leve hele livet – En kvalitetsreform for eldre [White Paper No. 15 (2017–2018). A full life – all your life: A Quality Reform for Older Persons]. Helse‐ og omsorgsdepartementet [Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care services] Oslo. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.‐st.‐15‐20172018/id2599850/

- Meld. St. 26 . (2014. –2015). Fremtidens primærhelsetjeneste – nærhet og helhet [White Paper No. 26 (2014–2015). The primary health and care services of tomorrow – localized and integrated]. Helse‐ og omsorgsdepartementet [Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care services] Oslo. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.‐st.‐26‐2014‐2015/id2409890/

- Meld. St. 7 . (2019. –2020). Nasjonal helse‐ og sykehusplan 2020–2023 [White Paper No. 7 (2019–2020). National health and hospital plan 2020–2023]. Helse‐ og omsorgsdepartementet [Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care services] Oslo. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.‐st.‐7‐20192020/id2678667/

- Meld. St. 9 . (2019. –2020). Kvalitet og pasientsikkerhet 2018 [White Paper No. 9 (2019–2020). Quality and patient safety 2018]. Helse‐ og omsorgsdepartementet [Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care services] Oslo. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.‐st.‐9‐20192020/id2681185/

- Midtbust, M. H. , Alnes, R. E. , Gjengedal, E. , & Lykkeslet, E. (2018). Perceived barriers and facilitators in providing palliative care for people with severe dementia: The healthcare professionals' experiences. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 709. 10.1186/s12913-018-3515-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B. , & Huberman, A. M. (1994). An expanded sourcebook. Qualitative data analysis (Section ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B. , Huberman, A. M. , & Saldana, J. (2013). Qualitative data analysis. A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S. C. , Lima, J. C. , Intrator, O. , Martin, E. , Bull, J. , & Hanson, L. C. (2016). Palliative care consultations in nursing homes and reductions in acute care use and potentially burdensome end‐of‐life transitions. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 64(11), 2280–2287. 10.1111/jgs.14469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota‐Romero, E. , Esteban‐Burgos, A. A. , Puente‐Fernández, D. , García‐Caro, M. P. , Hueso‐Montoro, C. , Herrero‐Hahn, R. M. , & Montoya‐Juárez, R. (2021). Nursing homes end of life care program (NUHELP): Developing a complex intervention. BMC Palliative Care, 20(1), 1–98. 10.1186/s12904-021-00788-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota‐Romero, E. , Tallón‐Martín, B. , García‐Ruiz, M. P. , Puente‐Fernandez, D. , García‐Caro, M. P. , & Montoya‐Juarez, R. (2021). Frailty, complexity, and priorities in the use of advanced palliative care resources in nursing homes. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 57(1), 70. 10.3390/medicina57010070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . (2016). Multimorbidity: Clinical assessment and management. NICE Guideline NG56. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guideance/NG/chapter/Recommendations#taking‐account‐of‐multimorbidity‐in‐tailoring‐the‐approach‐to‐care [Google Scholar]

- NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery . (2017). What is patient‐centered care? https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559

- NOU Norges offentlige utredninger . (2017:16). På liv og død. Palliasjon til alvorlig syke og døende . [Norwegian official report NOU 2017:16. On Life and Death. Palliative care of the severely ill and dying]. Departementenes sikkerhets‐ og serviceorganisasjon. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/995cf4e2d4594094b48551eb381c533e/nou‐2017‐16‐pa‐liv‐og‐dod.pdf

- Olsen, T. , & Solstad, E. (2020). Changes in the power balance of institutional logics: Middle managers' responses. Journal of Management & Organization, 26(4), 571–584. 10.1017/jmo.2017.72 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pivodic, L. , Smets, T. , Van den Noortgate, N. , Onwuteaka‐Philipsen, B. D. , Engels, Y. , Szczerbińska, K. , Finne‐Soveri, H. , Froggatt, K. , Gambassi, G. , Deliens, L. , & Van den Block, L. (2018). Quality of dying and quality of end‐of‐life care of nursing home residents in six countries: An epidemiological study. Palliative Medicine, 32(10), 1584–1595. 10.1177/0269216318800610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. F. , & Beck, C. T. (2021). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (11th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health. [Google Scholar]

- Riksrevisjonen [Auditor General of Norway] . (2016). Riksrevisjonens undersøkelse av ressursutnyttelse og kvalitet i helsetjenesten etter innføring av samhandlingsreformen Dokument 3:5 (2015–2016) [the Office of the Auditor General's audit of resource utilization and quality in health care services after implementation of the coordination reform. Document 3:5 (2015–2016)]. Riksrevisjonen. https://www.riksrevisjonen.no/globalassets/rapporter/no‐2015‐2016/samhandlingsreformen.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Roach, A. , Rogers, A. H. , Hendricksen, M. , McCarthy, E. P. , Mitchell, S. L. , & Lopez, R. P. (2022). Guilt as an influencer in end‐of‐life care decisions for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 48(1), 22–27. 10.3928/00989134-20211206-03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiano, N. , & Perry, T. E. (2019). Conducting secondary analysis of qualitative data: Should we, can we, and how? Qualitative Social Work, 18(1), 81–97. 10.1177/1473325017700701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiøtz, M. L. , Høst, D. , & Frølich, A. (2016). Involving patients with multimorbidity in service planning: Perspectives on continuity and care coordination. Journal of Comorbidity, 6(2), 95–102. 10.15256/joc.2016.6.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slåtten, K. , Fagerström, L. , & Hatlevik, O. E. (2010). Clinical competence in palliative nursing in Norway: The importance of good care routines. International Journal of Palliativ Nursing, 16(2), 81–86. 10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.2.46753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasova, S. , Baeten, R. , Coster, S. S. , Ghailani, D. , Peńa‐Casas, R. , & Vanhercke, B. (2018). Challenges in Long‐term Care in Europe; a study of national polices, European social policy network (ESPN). European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- St. meld. nr. 47 . (2008. –2009). Samhandlingsreformen. Rett behandling‐ på rett sted‐ til rett tid . [white paper No. 47 (2008–2009). The coordination reform – Proper treatment – At the right place and right time]. Helse‐ og omsorgsdepartementet [Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care services] Oslo. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld‐nr‐47‐2008‐2009‐/id567201/

- Stewart, M. , Brown, J. B. , Weston, W. W. , McWhinney, I. R. , McWilliam, C. L. , & Freeman, T. R. (2006). Patient‐centred medicine. Transforming the clinical method. Radcliffe Medical Press Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Thorkildsen, K. M. , Eriksson, K. , & Råholm, M.‐B. (2012). The substance of love when encountering suffering: An interpretative research synthesis with an abductive approach. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 27(2), 449–459. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01038.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortajada, S. , Soledad, Giménez‐Campos, M. , Villar‐López, J. , Faubel‐Cava, R. , Donat‐Castelló, L. , Valdivieso‐Martínez, B. , Soriano‐Melchor, E. , Bahamontes‐Mulió, A. , & García‐Gómez, J. M. (2017). Case management for patients with complex multimorbidity: Development and validation of a coordinated intervention between primary and hospital care. International Journal of Integrated Care, 17(2), 4. 10.5334/ijic.2493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torvik, K. , Kaasa, S. , & Kirkevold, Ø. (2008). Pain in patients living in Norwegian nursing homes. Palliative Medicine, 23(1), 8–16. 10.1177/0269216308098800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronto, J. C. (1998). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vabø, M. (2012). Norwegian home care in transition – Heading for accountability, off‐loading responsibilities. Health & Social Care in the Community, 20(3), 283–291. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vik, E. (2018). Helseprofesjoners samhandling – En litteraturstudie [coordination between health care professions: A scoping review]. Tidsskrift for Velferdsforskning, 21(2), 119–147. 10.18261/issn.2464-3076-2018-02-03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2011). Palliative care for older people: Better practices. Regional Office for Europe. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/143153/e95052.pdf [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020). Palliative care . https://www.who.int/health‐topics/palliative‐care

- World Health Organisation . (2022). Ageing and health. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/ageing‐and‐health

- World Medical Association . (2013). WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects . https://www.wma.net/policies‐post/wma‐declaration‐of‐helsinki‐ethical‐principles‐for‐medical‐research‐involving‐human‐subjects/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yin, R. K. (2008). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.