Abstract

Aim

Nurse practitioners' added value is often mentioned in publications, but there is no consensus on what value is being added, what value is being added to, and in comparison with what can be considered to be an added value. A concept analysis was conducted to clarify the attributes, antecedents and meaning and better understand the Nurse practitioners' added value.

Design

Rodgers' evolutionary concept analysis.

Methods

We selected 16 studies from CINAHL, PubMed, Embase and Medline to conduct a thematic analysis, considering the date, location and discipline of publications.

Results

Nurse practitioners' added value include: skills and competencies, activities performed, positive outcomes, and positive role perceptions, and antecedents and consequences were also identified. Nurse practitioners' added value is context‐dependent and is often understood by comparing it to a context prior to implementation or other professional roles.

Keywords: added value, advanced practice, competencies, concept analysis, nurse practitioners, nursing, outcomes, skills

1. INTRODUCTION

More and more researchers are interested in the role of nurse practitioners (NPs), and the literature on the subject is growing, often highlighting its added value (Boeijen et al., 2020). Although frequently used, this concept of the NPs' added value is often ambiguous, poorly defined and difficult to understand. Therefore, in the context where NPs' role is expanding significantly globally (Maier et al., 2016), it is crucial to understand its added value to justify and support its implementation and sustainability.

2. BACKGROUND

The added value of NPs is often mentioned in the literature, but the concept remains undefined and lacks clarity. Authors often fail to describe what value is being added to (e.g. value‐added to increase access to care, improve the work of the healthcare team or achieve cost‐effectiveness). Few indicate how NPs add value and against which standard or comparator (Boeijen et al., 2020; Fanta et al., 2006; Hyde et al., 2020; Lovink et al., 2019; Stahlke Wall & Rawson, 2016). Some authors approach it operationally by measuring quantifiable indicators such as productivity (Rhoads et al., 2006), while others do so by investigating the perception of the NPs' added value, but without defining the concept (Kaasalainen et al., 2010; Leidel et al., 2018; Wand et al., 2011a). Numerous studies have been conducted on indicators such as positive health outcomes (David et al., 2015; Stanik‐Hutt et al., 2013), high patient satisfaction (Delamaire & Lafortune, 2010; Laurant et al., 2018) or cost savings when patients are being followed by NPs (Delamaire & Lafortune, 2010; Hyde et al., 2020). However, these indicators have not been linked to the concept of the NPs' added value. It is concerning because the NPs' added value often serves as a justification, a driving force, or an argument to enable the implementation and sustainability of the role of NPs (Boeijen et al., 2020; Stephens, 2012).

The added value comprises two terms: ‘added’ and ‘value’. ‘Added’ comes from the verb ‘to add’ and is defined as ‘that is or has been added or added to; additional, increased, extra’ (Oxford English Dictionary, 2022‐a). The term ‘value’ was borrowed from French and is defined as ‘worth or quality as measured by a standard of equivalence’, and also ‘a thing regarded as worth having’ (Oxford English Dictionary, 2022‐b). The ‘added value’ and its derivation, ‘value‐added’, have been defined in the dictionary in relation to their economic meaning: ‘Of or relating to the amount by which the value of an article is increased at each stage of its production, exclusive of the cost of materials and bought‐in parts and services’, or in a more general way: ‘the benefits imparted to an undertaking by the work of a particular person or group; (more generally) additional gain or advantage’ (Oxford English Dictionary, 2022‐c).

In the context where the NP's role is expanding globally (Maier et al., 2016), it is crucial to understand its added value to justify and support its implementation and sustainability in healthcare systems. NPs emerged in the United States in the 1960s to address unmet primary healthcare needs (International Council of Nurses, 2020). Since then, their role has evolved and adapted to the different primary healthcare needs and healthcare specialties (International Council of Nurses, 2020). NPs worldwide grow due to physician shortages, increasingly complex healthcare needs, and rising healthcare costs (Delamaire & Lafortune, 2010).

Nurse practitioners are nurses who have pursued higher education, minimally at the master's level, to acquire advanced knowledge and skills in their specialty. In addition to nursing activities, they can perform additional ones, such as diagnosing illnesses, prescribing tests and medications, or performing invasive procedures (International Council of Nurses, 2020). The requirements for entry into the profession and the scope of practice are highly dependent on the legislation, specialization and practice context (International Council of Nurses, 2020). Moreover, their professional title can vary depending on the different legislations worldwide. They may be referred to as NPs, and sometimes as ‘advanced practice nurses’ (APN), an umbrella term that includes NPs and other nursing roles (e.g. clinical nurse specialist) (International Council of Nurses, 2020). Therefore, the APN title can lead to confusion about the nature of the role and its scope of practice. For this paper, those who fit the following definition will be considered NPs:

[…] Advanced practice nurse who integrates clinical skills associated with nursing and medicine in order to assess, diagnose and manage patients in primary healthcare settings and acute care populations as well as ongoing care for populations with chronic illness. (International Council of Nurses, 2020, p. 6).

This paper aimed at defining and clarifying the concept of the added value of nurse practitioners by exploring how the concept is used in the literature, understanding its meaning in different contexts and thus developing knowledge on the added value of the role. As concepts are dynamic, context‐dependent and evolve according to their situation and over time (Rodgers, 2000), the findings are not an end goal but rather a starting point in developing knowledge about the added value of NPs. Although concepts occupy a critical role in theory development, they also have significant theoretical power in their own right as they provide the opportunity to categorize, organize, label, discuss and study phenomena of interest in the discipline (Rodgers et al., 2018). To our knowledge, no analysis has been published on this concept or the added value of other healthcare professionals' roles. Therefore, this concept analysis will serve as a heuristic in providing the clarity necessary to create a foundation for future and ongoing development of the concept of the NPs' added value and better understand and support this role from implementation to practice.

3. DESIGN

Rodgers' (2000) evolutionary approach to concept analysis was selected to analyse the added value of NPs because it recognizes the dynamic and evolving nature of the concept and acknowledges its evolution in different contexts and over time. This approach aimed at identifying all the relevant aspects of the concept across places, time and contexts. It is particularly relevant given the inconsistent role implementation in different jurisdictions and clinical settings and its rapid development.

4. METHOD

Rodgers’ (2000) approach consists of six activities: (1) identification of the concept of interest and associated terms; (2) identification and selection of the appropriate realm for data collection; (3) data collection to identify attributes, antecedents, and consequences of the concept; (4) analysis of results; (5) identification of an exemplar of the concept, if appropriate; and (6) identification of the implications and hypotheses for further development of the concept. Although using an exemplar (activity 5) helps to illustrate the ideas, no relevant ones were found or used due to the small amount of data related to this concept. The absence of an exemplar informs and confirms the early stage of development of the concept (Rodgers, 2000).

4.1. Data sources

The first activity of the evolutionary concept analysis approach consists of identifying the concept of interest and the surrogate and related terms (Rodgers, 2000). A screening of the seminal literature on the topic, looking for keywords ‘added value’, ‘nurse practitioner’, and ‘role’, allowed the exploration of how the concept of the added value of NPs has been used in publications and also allowed to identify the terms associated to the concept. As a result, three groups of words and MeSH descriptors emerged (Table 1) and combined Boolean operators in the search strategy. The strategy was validated by an academic librarian and was adapted specifically for each selected database: CINAHL, PubMed, Embase and Medline.

TABLE 1.

Group of words and MeSH descriptors in the search strategy

| Added value | Nurse practitioner | Role |

|---|---|---|

|

Value‐add Value‐added Additional value Added benefit Additional benefit Added advantage Additional advantage |

Advanced practice nurses Advanced nursing practice |

Professional role |

The second activity described by Rodgers (2000) for concept analysis concerns the choice of the realm of data. Since no conceptual analysis of the value‐added of nurse practitioners was found in the literature, it is advisable to consider a wide range of documentary data without restrictions of date, place of publication or disciplinary perspective. To be included, publications had to meet these criteria: (1) scientific or professional articles; (2) published in English or French; (3) available in full text; (4) mentioning the added value of NPs; and (5) specific to the NP's role. Articles that did not meet these inclusion criteria were excluded.

Both scientific and professional articles were included to access diverse perspectives from the scientific and clinical communities. The research was limited to the languages spoken by the authors for feasibility reasons, and access to the full‐text articles was necessary for their analysis. Even when it was not the main focus of the article, the authors had to mention the NP's added value. When the role was labelled as APN, it had to implicitly or explicitly meet the International Council of Nurses (2020) definition of NP provided in the background section. Articles were excluded if the role was not specified or differentiated from another role. No limitations in terms of the type of study, first author's discipline or date of publication were added, as the diversity of articles allows for comparisons and trends identification across contexts, disciplines, and over time.

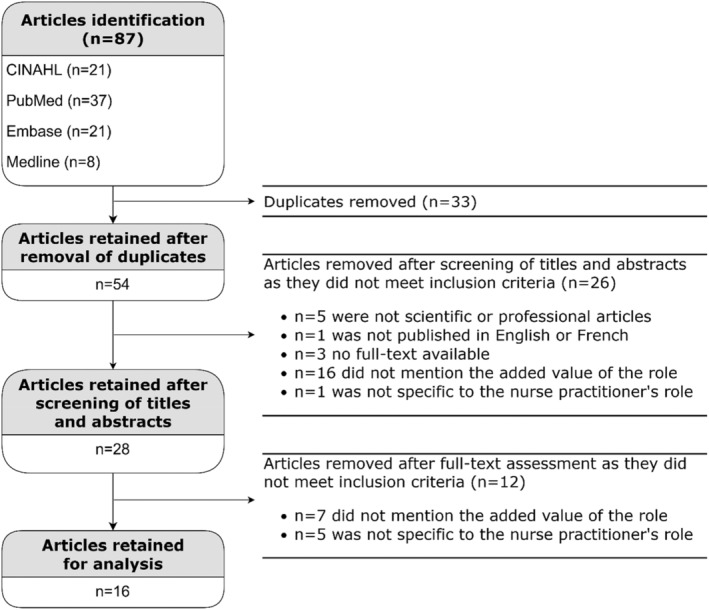

The literature search conducted on 8 July 2021 generated 87 papers. After removing the duplicates (n = 33), 54 articles remained. An evaluation of titles and abstracts performed by the lead author resulted in the rejection of 26 more articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. For the 28 documents remaining, a full‐text screening was carried out, and 12 more did not meet the inclusion criteria. Therefore, a total of 16 papers were included in the analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the selection of articles

4.2. Analysis

The third activity of concept analysis described by Rodgers (2000) concerns the collection and management of relevant data to identify the attributes, antecedents and consequences of the concept, and the fourth step is data analysis. Each included article was read at least twice by the lead author, first to capture the use, essence, attributes, surrogate terms and concepts associated with the NPs' added value, and then to analyse the antecedents, consequences and context, and to ensure an iterative analysis process (Rodgers, 2000). Data were extracted, identifying the name and discipline of the first author, year and country of publication and title of the role discussed (NP or APN). Then, data were extracted in terms of attributes, antecedents, consequences, clinical context, comparator or standard against which the added value of the role was contextualized, surrogate terms and related concepts. These data were then analysed by date and county of publication, and by different contexts to highlight similarities, differences, and trends.

4.3. Ethics

Ethics approval was not required for this concept analysis because all data were derived from publicly available documents.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Search results

The included articles' dates, countries of publication and clinical settings are shown in Table 2. All articles originated from the nursing discipline, with the primary author being a Registered Nurse (n = 9) or NP (n = 6). For one article (Meunier, 2008), the affiliation or title of the author was not available; however, the publication was in a professional nursing journal. Therefore, it was impossible to analyse the articles' content from different disciplinary perspectives.

TABLE 2.

Countries of publication and clinical settings of articles included

| Reference | Country | Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Boeijen et al. (2020) | NL | Outpatient care |

| Fanta et al. (2006) | USA | Paediatric trauma centre |

| Hyde et al. (2020) | UK | Paediatric services |

| Kaasalainen et al. (2010) | CA | Long‐term care |

| Kilpatrick (2013) | CA | Acute care |

| Leidel et al. (2018) | AU | Private sector |

| Lovink et al. (2018) | NL | Primary healthcare |

| Lovink et al. (2019) | NL | Long‐term care |

| Meunier (2008) | CA | Outpatient care |

| Rhoads et al. (2006) | USA | Not specified |

| Sangster‐Gormley et al. (2013) | CA | Long‐term care |

| Stahlke et al. (2017) | CA | Oncology |

| Stahlke Wall and Rawson (2016) | CA | Oncology |

| Stephens (2012) | USA | Primary healthcare |

| Wand et al. (2011a) | AU | Mental health outpatient clinic |

| Wand et al. (2011b) | AU | Mental health outpatient clinic |

Abbreviations: AU, Australia; CA, Canada; NL, the Netherland; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America.

5.2. Common definitions and uses

The concept of the NPs' added value does not seem to have been analysed or clearly defined in the literature. None of the 16 articles analysed provided an explicit definition of this concept. The authors implicitly used the concept of NPs' added value as if it were self‐evident and supported their statements with examples or descriptions of what they considered an added value.

5.3. Surrogate terms and related concepts

Although most of the articles analysed used the expression ‘added value’ to discuss the concept, surrogate terms were also identified. While these terms may have some nuances, they share the same characteristics as the added value. The surrogate terms identified are: ‘value‐added’ (n = 4), ‘value‐adding’ (n = 1), ‘adding value’ (n = 1), ‘additional value’ (n = 1), ‘value add’ (n = 3), ‘add value’ (n = 1), ‘benefits’ (n = 5), ‘additional benefit’ (n = 2), ‘worth’ (n = 1), ‘additional skills’ (n = 1), and ‘distinct contribution’ (n = 1). The references for these terms are found in the (Table S1). Some authors did not use surrogate terms and only used ‘added value’ (Kaasalainen et al., 2010; Lovink et al., 2019; Meunier, 2008).

According to Rodgers (2000), identifying related concepts is based on the philosophical assumption that each concept exists as part of a network of related concepts. Therefore, related concepts provide context and help to give meaning to the concept under study. The concepts related to, but differentiated from, the NPs' added value are: “role substitution’ (n = 5), ‘alternative role’ (n = 2), ‘complementary role’ (n = 3), ‘effectiveness’ (n = 7), ‘efficiency’ (n = 2), ‘quality of care’ (n = 9), ‘skill mix change’ (n = 2), ‘employability’ (n = 1), ‘productivity’ (n = 1), ‘physician extenders’ (n = 2), ‘mid‐level provider’ (n = 1), and ‘super‐nurse’ (n = 1). The references for each related concept can be found in Table S1.

These related concepts can reveal particular contexts and perspectives. Indeed, the concepts of substitution, alternative or complementary roles can indicate how the NP's role has taken root in the context. For example, when the NP is perceived as a substitute for the physician or is referred to as a physician‐extender, it may indicate a context with service gaps or unmet medical needs as it is often an opportunity to implement an NP role (International Council of Nurses, 2020). Using expressions such as alternative or complementary roles or skill mix change implies that there are not necessarily unmet medical needs but rather complex care where multiple experts are required, which is another favourable context for implementing the role (International Council of Nurses, 2020). There does not appear to be any marked dissonance in related concepts in reference to the articles’ date or country of publication.

5.4. Attributes of the NPs' added value

The identification of attributes is the cornerstone of concept analysis. Attributes enable the identification of situations that fall within the concept and those that can be appropriately characterized using the concept under study. Therefore, they form the definition of the concept according to the data analysed, but they can be modified, improved or validated in an iterative way (Rodgers, 2000). For this analysis, attributes of the added value of NPs were categorized in relation to the NPs' skills and competencies, the activities they perform, their positive outcomes and the positive perceptions of the role (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Attributes, antecedents and consequences of the nurse practitioners' added value

| Boeijen et al. (2020) | Fanta et al. (2006) | Hyde et al. (2020) | Kaasalainen et al. (2010) | Kilpatrick (2013) | Leidel et al. (2018) | Lovink et al. (2018) | Lovink et al. (2019) | Meunier (2008) | Rhoads et al. (2006) | Sangster‐Gormley et al. (2013) | Stahlke et al. (2017) | Stahlke Wall and Rawson (2016) | Stephens (2012) | Wand et al. (2011a) | Wand et al. (2011b) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTRIBUTES | Skills and competencies | Holistic patient‐centred care | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||

| Combined nursing and medical skills | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||

| Problem‐solving and critical thinking skills | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Complex decision‐making skills | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Expert evidence‐based clinical knowledge and skills | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||

| Leadership and advocacy | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||

| Strong communication skills | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||

| Collaborative skills | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Coaching, mentoring, teaching, and education skills | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||

| Activities performed | Direct patient care | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||

| Task sharing (substitution or complementarity) | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Activities previously reserved for physicians | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Care coordination | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Proactive health promotion and prevention | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Positive outcomes | High‐quality care | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||

| High patient and family satisfaction | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||

| More time spent with patients and families | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Timely healthcare delivery | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Continuity of care | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Positive role perception | More autonomous work | ● | |||||||||||||||||

| Fulfilling role | ● | ||||||||||||||||||

| ANTECEDENTS | NPs' intrinsic characteristics | Leadership | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| Clinical expertise / Expert knowledge | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Scientific competencies | ● | ||||||||||||||||||

| Complex decision‐making skills | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||

| Collaboration skills | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||

| NPs' extrinsic characteristics | Registered Nurse with graduate‐level education | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||

| Authorization to practice as a nurse practitioner in a jurisdiction | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||

| Role clarity and promotion | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Favourable context (e.g. service gap) | ● | ||||||||||||||||||

| Scope of practice | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||

| CONSEQUENCES | On patient care | Provision of quality and safe, direct care | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| Reduction in length of stay in hospitals | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||||

| High patients, caregiver, and family satisfaction | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||

| Patient education | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Timely healthcare provision and follow‐ups | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| Reduction of hospital (re)admissions and emergency department visits | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||||

| On healthcare teams | Improved team collaboration and communication | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||

| Team education, mentoring, and coaching | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||

| Reallocation of physician time to patients with complex needs | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||

| On healthcare systems | Improved access to care | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||

| Reduce healthcare costs | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||||||||||

| Innovation in services provided | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||||||

5.4.1. NPs' skills and competencies

Several authors have described the added value of NPs based on their skills and competencies. These include holistic patient‐centred care (n = 8), combined and integrated nursing and medical skills (n = 7), problem‐solving and critical thinking skills (n = 4), complex decision‐making (n = 3), expert clinical knowledge and skills (n = 5), leadership and advocacy (n = 5), strong communication skills (n = 5), collaborative skills (n = 3), and coaching, mentoring, teaching and educational skills (n = 8). The analysis failed to identify trends or inconsistencies according to the country and year of publication or the clinical context.

5.4.2. Activities performed by NPs

The NPs' added value was also described in terms of the activities they perform. It was the case for direct patient care (n = 8), task sharing or acting as physicians substitutes or as a complement to physician and other healthcare providers (n = 4), providing activities previously reserved for physicians (n = 3), coordinating care (n = 3), and offering proactive health promotion and illness prevention care (n = 3).

While no trend over time or clinical settings was revealed, some associations relative to the country of publication could be made. Articles from the Netherlands identified NPs as substitutes for other healthcare professionals, most often physicians (Boeijen et al., 2020; Lovink et al., 2018, 2019), and this element did not emerge in the articles from other countries. These authors were also the only ones to highlight the NPs' added value in performing additional activities previously reserved for physicians. Also, two of the three articles discussing the NPs' role as a complement of other healthcare professionals were from the Netherlands (Lovink et al., 2018, 2019), while the third publication was from Australia (Leidel et al., 2018).

5.4.3. NPs' positive outcomes

NPs' positive outcomes have also been described as an added value. These include high‐quality care (n = 6), high patient and family satisfaction (n = 5), more time spent with patients and families (n = 3), timely healthcare delivery (n = 4) and enhanced continuity of care (n = 3).

These positive outcomes are also often highlighted as consequences of the added value of NPs. It explains why some of these outcomes appear both as attributes and consequences, depending on how the authors discussed them in relation to the NPs' role. The analysis revealed no trends or inconsistencies over time, place or across clinical settings in using positive outcomes to discuss the NPs' added value.

5.4.4. Positive role perception

The NPs' added value was also discussed in terms of how the role was perceived by NPs, teams, managers, patients or caregivers. Some authors reported it as perceptions of more autonomous work (n = 1), fulfilling role (n = 1), and perception of NPs' positive attitude (n = 2). Relatively few articles focussed on perceptions of the added value of the role in this sample. No trends, consistencies, or inconsistencies in time or place of publication or across clinical settings could be identified.

5.5. Antecedents

Antecedents are situations or themes preceding an instance of the concept (Rodgers, 2000). The literature analysed revealed that the antecedents of the NPs' added value can be categorized into the NPs' intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics (Table 3). Intrinsic characteristics are part of the individual characteristics of NPs, while extrinsic characteristics are external to NPs and do not depend on their nature.

5.5.1. NPs' intrinsic characteristics

Antecedents in terms of NPs' intrinsic characteristics include leadership (n = 1), clinical expertise and expert knowledge (n = 4), scientific competencies (n = 1), complex decision‐making skills (n = 2) and collaboration skills (n = 2). No trends or inconsistencies were found over time, across clinical settings or publication countries.

5.5.2. NPs' extrinsic characteristics

Antecedents of NPs' added value in terms of extrinsic characteristics include being Registered Nurses with graduate‐level education (n = 9), being licensed as NPs in their jurisdiction (n = 2), clarity and promotion of the role (n = 4), supportive environment and favourable context (e.g. service gap; n = 1) and a regulated scope of practice with reserved activities and procedures (n = 2).

Leidel et al. (2018) mention that professional title is not always protected by law depending on the location. The importance of role clarity and promotion is often discussed in the literature and is supported by guidelines on advanced practice nursing (International Council of Nurses, 2020). There appears to be a consensus among authors, primarily in Canada and the Netherlands, that without clarification and recognition of the NPs' role, they cannot use their role to its full potential (Boeijen et al., 2020; Kaasalainen et al., 2010; Lovink et al., 2019; Stahlke Wall & Rawson, 2016). Too few articles supported the same characteristics as antecedents of the concept to discerning trends regarding publication countries, clinical settings or publication dates.

5.6. Consequences

Consequences are the events or states that result from the concept (Rodgers, 2000). The consequences resulting from the NPs' added value can impact patient care, healthcare teams, and healthcare systems (Table 3).

5.6.1. Consequences on patient care

The consequences of the NPs' added value on patient care are discussed abundantly in the literature. In this analysis, there is an agreement regarding several consequences, including the provision of safe, high‐quality care (n = 9), high patient, caregiver, and family satisfaction (n = 6), quality patient education (n = 4) and timely healthcare and follow‐ups delivery (n = 4). Although many authors have discussed reduced hospital admissions and readmissions as a consequence of the NPs' added value (n = 4), a systematic review included identified two articles that looked at these indicators, one showing no effect and the other a slight increase in hospital admissions or readmissions (Hyde et al., 2020). These discordant results may be due to contextual differences (e.g. practice setting), study limitations or differences in the scope of practice of NPs, such as the activities they are allowed to perform in their specialties and jurisdictions. Finally, the reduction in length of stay in hospitals was identified as a consequence of the NPs' added value on patient care (n = 2). For NPs to reduce patient length of stay in the hospital, they must work in a hospital setting and be authorized to discharge patients within their scope of practice, limiting the findings as few articles fit this context. No trends or inconsistencies in the dates, settings or publication countries for consequences on patient care were identified.

5.6.2. Consequences on healthcare teams

Consequences on healthcare teams were identified in the articles as the improvement of collaboration and communication within the teams (n = 5) and team education, mentoring and coaching (n = 7). Another consequence is the reallocation of physician time to patients with complex needs (n = 3). Thus, patients with stable, chronic conditions requiring routine or minor care could be followed by NPs, freeing physicians to care for more complex cases.

Collaboration and communication as a consequence of the NPs' added value in healthcare teams were identified in articles from Canada (n = 3), but also from the United States (n = 1) and the Netherlands (n = 1). Of the seven articles that mentioned education, mentoring and coaching in healthcare teams, four focussed on the role of NPs in long‐term care facilities (Kaasalainen et al., 2010; Lovink et al., 2018, 2019; Sangster‐Gormley et al., 2013), and two in chronic disease or oncology management (Stahlke et al., 2017; Stephens, 2012). Therefore, a chronic care setting may be particularly conducive to the NPs' added value in terms of education, mentoring and coaching for healthcare teams, but more data are needed to support this assumption. Finally, reallocation of physician time to patients with complex needs was reported in Canada in oncology settings (Stahlke et al., 2017; Stahlke Wall & Rawson, 2016) and the United Kingdom in paediatric services (Fanta et al., 2006).

5.6.3. Consequences on healthcare systems

Some articles addressed the NPs' added value in terms of health systems' consequences. Improved access to care was frequently mentioned (n = 7), but Hyde et al. (2020) highlighted no consensus on this indicator. There does not appear to be a pattern to this inconsistency related to country or publication date or in relation to the clinical setting. Another consequence of the NPs' added value is healthcare cost reduction (n = 6). Despite this, in their systematic review, Hyde et al. (2020) highlighted cost variability related to the NPs' role. Finally, the consequences of the NPs' added value have also been discussed in terms of innovation in services provided (n = 3). These data do not appear to vary by time, context or country.

5.7. Comparator

According to common definitions and uses of the added value of something, it is usually used in relation to a comparator. This analysis assessed the attributes, antecedents and consequences of the NPs' added value by examining what the authors compared them to. Several authors have discussed aspects of the added value of NPs without offering a specific comparison. It was the case for articles from Canada (Kilpatrick, 2013; Meunier, 2008; Sangster‐Gormley et al., 2013), the United States (Rhoads et al., 2006; Stephens, 2012), Australia (Wand et al., 2011b) and the Netherlands (Lovink et al., 2018). No trends across time could be identified.

Other articles have compared aspects of the NPs' added value to medical roles, such as medical residents (Hyde et al., 2020), physicians (Fanta et al., 2006; Wand et al., 2011a) or oncologists (Stahlke et al., 2017; Stahlke Wall & Rawson, 2016). No trend in location, settings or time could be identified.

A comparison of the added value of NPs was also noted in relation to nursing roles in the Netherlands, namely Registered Nurses (Lovink et al., 2019) and nurse specialists (Boeijen et al., 2020). These articles were published in 2019 and 2020, but it is difficult to confirm a trend in place and time given the few articles.

Finally, the NPs' added value has also been discussed by comparing the NPs' role to that of physician assistants (Lovink et al., 2019) or simply to the functioning of a setting before the NPs' role implementation (Kaasalainen et al., 2010; Leidel et al., 2018). The small number of articles does not allow analysis across time or place.

5.8. Conceptual definition

Based on this analysis, the NPs' added value can be defined as: ‘A set of skills, competencies, activities, positive outcomes, and perceptions related to the role of NPs that positively impact patient care, teams, and healthcare systems through the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of the NP. This added value can be highlighted against different comparators, either a clinical context prior to the implementation of the NP's role or other nursing, medical, or health professionals’ roles’. In keeping with the analytical approach used, this definition is considered a starting point and not an endpoint and is therefore provisional and constantly evolving (Rodgers, 2000).

6. DISCUSSION

This section will discuss the key findings in relation to current knowledge by highlighting the implications and assumptions that arise from them, which is Activity 6 of Rodgers' (2000) conceptual analysis. The purpose of this paper was to present the results of a concept analysis of the NPs' added value. It has been achieved by identifying the attributes, that is the situations that belong to the concept itself. The attributes identified were very similar to the competencies of NPs recognized globally by different bodies, including the International Council of Nurses (2020) (Box 1). These competencies are widely accepted by researchers, educators and clinicians in advanced practice nursing.

BOX 1. Competencies for Nurse Practitioners (International Council of Nurses, 2020).

| 1. Demonstrates safe and accountable Nurse Practitioner practice incorporating strategies to maintain currency and competence. |

| 2. Conducts comprehensive assessments and applies diagnostics reasoning to identify health needs/problems and diagnoses. |

| 3. Develops, plans, implements and evaluates therapeutic interventions when managing episodes of care. |

| 4. Consistently involves the health consumer to enable their full partnership in decision making and active participation in care. |

| 5. Works collaboratively to optimise health outcomes for health consumers/population groups. |

| 6. Initiates and participates in activities that support safe care, community partnership and population improvements. |

Similarly, the skills and competencies highlighted in this analysis are also similar to the advanced nursing practice core competencies proposed by Tracy and O'Grady (2019). These include direct clinical practice, guidance and coaching, consultation, evidence‐based practice, leadership and ethical decision‐making. Moreover, the NP competencies identified in the Pan‐Canadian Advanced Practice Nursing Framework (Canadian Nurses Association, 2019) are also consistent, as they are described as: comprehensive direct care, health systems optimization, education, research, leadership, consultation and collaboration, unique competencies, continuing competencies and protection of professional liability. Some differences between the competencies identified by the International Council of Nurses (2020), Tracy and O'Grady (2019), and the Canadian Nurses Association (2019) framework, and those identified in this concept analysis as attributes of the NPs' added value may be due to different interpretations of the literature consulted, the method of analysis used, and the small sample size used in this analysis. In addition, because the NP's role is highly dependent on the context in which it is implemented (International Council of Nurses, 2020), these variations may also be related to differences in licensing laws, scopes of practice, the status of role development and different clinical settings. Indeed, the International Council of Nurses (2020) takes a broad perspective to represent the global context, while Tracy and O'Grady (2019) developed their work in the United States context, the Canadian Nurses Association (2019) in the Canadian context, and this concept analysis brought together studies published in five different countries that are located on three continents.

Since few studies have explicitly looked at the added value of NPs, it was not surprising to find that the other attributes and antecedents identified in this concept analysis have not been discussed explicitly in the scientific literature. Nonetheless, although not directly associated with the NPs' added value, these elements, such as professional activities performed or positive outcomes, have been well‐described in studies about NPs' practice and thus, appear to be relevant indicators in this context.

The clarification and definition of the concept of the added value of NPs allow for a better understanding that may have implications for nursing, health systems, healthcare teams and patient care in terms of clinical practice, management, teaching and research. For example, Ho et al. (2019) identified that master‐prepared nurses, such as nurse practitioners, are able to push the boundaries of nursing and develop leadership. Thus, it is crucial to reflect on the nurse practitioners' added value to care, even more so where the role is emerging, so that they are change agents contributing to the advancement of the nursing profession to provide quality care. On a theoretical level, these findings may help further refine current conceptual frameworks by identifying specific factors that underpin the added value of NPs. Indeed, the use of the concept of the added value of NPs can help to support initiatives to implement and support the role at these different levels. This analysis also contributes to the nursing knowledge base to better understand this concept in the context of this emerging role that is rapidly developing on a large scale.

6.1. Rigour

A stepwise approach was followed with recognized criteria of rigour in qualitative research (Johnson et al., 2020). First, the identification of the concept, the objectives of the analysis and the development of the literature search strategy were done before starting the analysis, and the search strategy was validated by an academic librarian in nursing. Then, a recognized approach was used, namely the evolutionary approach of concept analysis (Rodgers, 2000). Data extraction and inductive coding were performed by the primary author and validated by the co‐authors (member checking). As Johnson et al. (2020) recommended, the discussion included interpretation of the results and implications (for nursing, health systems, care teams, and patient care). Finally, the analysis report contains all elements of the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (O'Brien et al., 2014) applicable to the evolutionary approach to concept analysis.

6.2. Limitations

Little data were available on this concept, which limited the interpretation of some results and the possibility of finding trends, similarities, or inconsistencies. In addition, because the articles included were from the nursing discipline, the analysis could not consider other professional perspectives. It is also possible that some publications included interdisciplinary perspectives, but we could not identify them. Identifying temporal trends was limited because the studies were published within a 14‐years interval, and only 16 were included. Therefore, it will be relevant to analyse this concept again in a few years to assess how it will have evolved with the new research that will have been published. Finally, another limitation relates to location. All included studies were from North America, Europe, and Oceania. Therefore, understanding of the concept of nurse practitioners' added value might be different if we had data from other locations and cultures (e.g. Latin America, Africa and Asia).

This concept analysis focussed on the NPs' added value, regardless of specialty or scope of practice. NPs are heterogeneous, as their professional experience, clinical setting, the scope of practice and professional activities may differ. Therefore, at this stage, it is difficult to know whether the concept of the NPs' added value might differ from one specialty to another or from one clinical setting to another. In addition, depending on the timing of role implementation and legislation in a jurisdiction, the NPs' roles may vary considerably. Roles developed decades ago in the United States are not at the same development and implementation stages as in the countries where it has been developed in recent years, which may also contribute to a limited interpretation of the results.

Since concept development is an iterative process (Rodgers, 2000) and the concept of the added value of nurse practitioners is still in its early stages of development, it would be desirable to repeat the analysis of this concept. Indeed, further studies using other data sources (e.g. interviews), at a different time period, or in a different context may contribute to a better understanding and definition of the concept.

7. CONCLUSION

In the global context of medical shortages and increasingly complex health needs, the emergence of NPs' roles has become evident in recent decades. These recognized healthcare professionals provide advanced nursing care and perform additional activities to meet these healthcare needs. A concept analysis was carried out using Rodgers (2000)'s evolutionary approach to understand their added value. It allowed highlighting the attributes of this concept related to skills and competencies, the professional activities performed, positive outcomes, and perceptions of the added value of the role. The antecedents of the concept were revealed in terms of intrinsic and extrinsic NPs' characteristics needed to enact it. Finally, the consequences of this added value of the role were highlighted at the levels of patient care, healthcare teams, and healthcare systems. These findings will provide a better understanding of the added value of NPs and serve as a basis for developing this essential concept of nursing knowledge.

This analysis has shed some light on this critical concept given the emergence and rapid development of the role around the world and has helped clarify, define and understand it. Knowledge gained from this concept analysis will enable NPs, healthcare teams, managers, students and researchers to understand better the NPs' added value, which is essential to support the implementation of this emerging role, its development, practice, education and research. More studies are needed to further develop this concept.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

IS, GAH and KK made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; given final approval of the version to be published. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria [recommended by the ICMJE (http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/)]:

substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data;

drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors. IS holds Doctoral scholarships from the Quebec Ministry of Education and from RRISIQ. GAH holds a Doctoral scholarship from RRISIQ. KK's work is funded by a FRQS Senior Researcher salary award and the Newton Foundation/Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, and she holds the Susan E. French Chair in Nursing Research and Innovative Practice. The funding bodies played no role in study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, nor the development of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With sincere acknowledgments to Professor Marjorie Montreuil, RN, PhD, (McGill University), who provided helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Savard, I. , Al Hakim, G. , & Kilpatrick, K. (2023). The added value of the nurse practitioner: An evolutionary concept analysis. Nursing Open, 10, 2540–2551. 10.1002/nop2.1512

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- Boeijen, E. R. K. , Peters, J. W. B. , & van Vught, A. J. A. H. (2020). Nurse practitioners leading the way: An exploratory qualitative study on the added value of nurse practitioners in outpatient care in the Netherlands. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 32(12), 800–808. 10.1097/jxx.0000000000000307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Nurses Association . (2019). Advanced practice nursing, a pan‐Canadian framework. Canadian Nurses Association; https://hl‐prod‐ca‐oc‐download.s3‐ca‐central‐1.amazonaws.com/CNA/2f975e7e‐4a40‐45ca‐863c‐5ebf0a138d5e/UploadedImages/documents/Advanced_Practice_Nursing_framework_EN.pdf [Google Scholar]

- David, D. , Britting, L. , & Dalton, J. (2015). Cardiac acute care nurse practitioner and 30‐day readmission. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 30(3), 248–255. 10.1097/jcn.0000000000000147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamaire, M.‐L. , & Lafortune, G. (2010). Nurses in Advanced Roles: A description and evaluation of experiences in 12 developed countries (Issue 54). https://www.oecd‐ilibrary.org/content/paper/5kmbrcfms5g7‐en

- Fanta, K. , Cook, B. , Falcone, R. A., Jr. , Rickets, C. , Schweer, L. , Brown, R. L. , & Garcia, V. F. (2006). Pediatric trauma nurse practitioners provide excellent care with superior patient satisfaction for injured children. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 41(1), 277–281. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.10.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, K. H. M. , Chow, S. K. Y. , Chiang, V. C. L. , Wong, J. S. W. , & Chow, M. C. M. (2019). The technology implications of master's level education in the professionalization of nursing: A narrative inquiry. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75, 1966–1975. 10.1111/jan.14044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, R. , MacVicar, S. , & Humphrey, T. (2020). Advanced practice for children and young people: A systematic review with narrative summary. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(1), 135–146. 10.1111/jan.14243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Nurses . (2020). Guidelines on advanced practice nursing 2020. https://www.icn.ch/system/files/documents/2020‐04/ICN_APN%20Report_EN_WEB.pdf

- Johnson, J. L. , Adkins, D. , & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(1), 7120. 10.5688/ajpe7120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaasalainen, S. , Martin‐Misener, R. , Carter, N. , DiCenso, A. , Donald, F. , & Baxter, P. (2010). The nurse practitioner role in pain management in long‐term care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(3), 542–551. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, K. (2013). How do nurse practitioners in acute care affect perceptions of team effectiveness? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(17–18), 2636–2647. 10.1111/jocn.12198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurant, M. , van der Biezen, M. , Wijers, N. , Watananirun, K. , Kontopantelis, E. , & van Vught, A. J. (2018). Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7, CD001271. 10.1002/14651858.cd001271.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidel, S. , Hauck, Y. , & McGough, S. (2018). “It's about fitting in with the organisation”: A qualitative study of employers of nurse practitioners. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(7–8), e1529–e1536. 10.1111/jocn.14282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovink, M. H. , van Vught, A. , Persoon, A. , Koopmans, R. , Laurant, M. G. H. , & Schoonhoven, L. (2019). Skill mix change between physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurses in nursing homes: A qualitative study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 21(3), 282–290. 10.1111/nhs.12601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovink, M. H. , van Vught, A. , Persoon, A. , Schoonhoven, L. , Koopmans, R. , & Laurant, M. G. H. (2018). Skill mix change between general practitioners, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and nurses in primary healthcare for older people: A qualitative study. BMC Family Practice, 19(1), 51. 10.1186/s12875-018-0746-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier, C. B. , Barnes, H. , Aiken, L. H. , & Busse, R. (2016). Descriptive, cross‐country analysis of the nurse practitioner workforce in six countries: Size, growth, physician substitution potential. BMJ Open, 6(9), e011901. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier, C. (2008). La valeur ajoutée: Témoignage d'une des premières IPS au Québec. Perspective Infirmière, 5(4), 16–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, B. C. , Harris, I. B. , Beckman, T. J. , Reed, D. A. , & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford English Dictionary . (2022‐a). Added: The Oxford English dictionary. Oxford University Press. WorldCat.org. www.oed.com/view/Entry/2161 [Google Scholar]

- Oxford English Dictionary . (2022‐b). Value: The Oxford English dictionary. Oxford University Press. WorldCat.org. www.oed.com/view/Entry/221253 [Google Scholar]

- Oxford English Dictionary . (2022‐c). Value‐added: The Oxford English dictionary. Oxford University Press. WorldCat.org. www.oed.com/view/Entry/247836 [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads, J. , Ferguson, L. A. , & Langford, C. A. (2006). Measuring nurse practitioner productivity. Dermatology Nursing, 18(1), 32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, B. L. (2000). Concept analysis: An evolutionary view. In Rodgers B. L. & Knafl K. A. (Eds.), Concept development in nursing: Foundations, techniques, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 77–102). W‐B Saunders Company. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, B. L. , Jacelon, C. S. , & Knafl, K. A. (2018). Concept analysis and the advance of nursing knowledge: State of the science. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 50(4), 451–459. 10.1111/jnu.12386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangster‐Gormley, E. , Carter, N. , Donald, F. , Misener, R. M. , Ploeg, J. , Kaasalainen, S. , McAiney, C. , Martin, L. S. , Taniguchi, A. , Akhtar‐Danesh, N. , & Wickson‐Griffiths, A. (2013). A value‐added benefit of nurse practitioners in long‐term care settings: Increased nursing staff's ability to care for residents. Nursing Leadership, 26(3), 24–37. 10.12927/cjnl.2013.23552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahlke, S. , Rawson, K. , & Pituskin, E. (2017). Patient perspectives on nurse practitioner Care in Oncology in Canada. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 49(5), 487–494. 10.1111/jnu.12313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahlke Wall, S. , & Rawson, K. (2016). The nurse practitioner role in oncology: Advancing patient care. Oncology Nursing Forum, 43(4), 489–496. 10.1188/16.onf.489-496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanik‐Hutt, J. , Newhouse, R. P. , White, K. M. , Johantgen, M. , Bass, E. B. , Zangaro, G. , Wilson, R. , Fountain, L. , Steinwachs, D. M. , & Heindel, L. (2013). The quality and effectiveness of care provided by nurse practitioners. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 9(8), 492–500. e13. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2013.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, L. (2012). Family nurse practitioners: “Value add” in outpatient chronic disease management. Primary Care, 39(4), 595–603. 10.1016/j.pop.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, M. F. , & O'Grady, E. T. (2019). Hamric and Hanson's advanced practice nursing: An integrative approach (6th ed.). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Wand, T. , White, K. , Patching, J. , Dixon, J. , & Green, T. (2011a). An emergency department‐based mental health nurse practitioner outpatient service: Part 1, participant evaluation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 20(6), 392–400. 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00744.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand, T. , White, K. , Patching, J. , Dixon, J. , & Green, T. (2011b). An emergency department‐based mental health nurse practitioner outpatient service: Part 2, staff evaluation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 20(6), 401–408. 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00743.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.