Abstract

Aim

The aim of the study was to identify, summarize and critically appraise studies that have investigated the effects of exercise and psychosocial interventions on body image of breast cancer survivors.

Design

A critical review.

Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted to identify relevant articles published in MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and British Nursing Index between 2011 and 2021. Included studies' methodological quality was assessed using the critical appraisal checklists of the Center for Evidence‐Based Management.

Results

A total of eight studies were included. Breast cancer survivors who received exercise or psychosocial interventions had an improved body image compared with baseline, which enhanced their quality of life. Compared with psychosocial interventions, exercise demonstrated more positive effects as they enhanced both mental and physical well‐being. Breast cancer survivors expressed that they preferred to have a knowledgeable mentor to guide and empower them throughout the exercise intervention. Psychosocial interventions showed varying effectiveness, with self‐compassion‐focused writing activity being most effective.

Keywords: body image, breast cancer, critical review, exercise, psychosocial intervention

1. INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide and breast cancer survivors are known to have a poor body image. Exercise interventions including resistance training, aerobic exercise as well as relaxation and stretching exercises are commonly adopted (Duijts et al., 2011; Fong et al., 2012; Hall‐Alston, 2015; Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018, Paulo et al., 2019, Stan et al., 2012). As for psychosocial interventions, a wide variety was observed with examples such as cognitive behavioural therapies, support group therapies, self‐writing exercises and psychoeducation available to help the survivors improve their body image (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018; Matthews et al., 2017; Sherman et al., 2018). According to previous studies, exercise and psychosocial interventions do bring a positive impact on the body image of breast cancer survivors, but the evidence on this is inconsistent. The best mode of delivery of the two interventions were not identified as well. As a result, this critical review aims to summarize and critically appraise studies that have investigated the effects of exercise and psychosocial interventions on body image of breast cancer survivors. It also highlights the needs and provides insight on the standardization of care towards breast cancer survivors.

2. BACKGROUND

Breast cancer is a malignant condition wherein breast cells grow uncontrollably and metastasise to distant parts of the body (American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Team, 2017; American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Content Team, 2017). Although most breast cancer patients are female, men can also to develop this cancer (American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Team, 2017; American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Content Team, 2017). Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women and the second most common cancer in both sexes worldwide, with more than 2.3 million newly diagnosed cases worldwide in 2018 (World Health Organization, 2021). Similarly, in Hong Kong, this top cancer in women accounted for 27.2% or 4,618 of the new cancer cases reported in 2018. It is also the third leading cause of cancer‐related deaths in Hong Kong women, with 852 deaths reported in 2019 (Centre for Health Protection, 2018). A common treatment procedure for breast cancer is mastectomy, which involves the removal of breast tissue, followed by adjunctive chemotherapy (American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Content Team, 2017). As a result of the high 10‐year survival rate of 84% for non‐metastatic invasive breast cancer, there is a large population of breast cancer survivors (Cancer.Net Editorial Board, 2018).

Body image is how a person pictures oneself in the mind and is known to deeply affect mental wellness and self‐esteem (National Eating Disorder Association, 2018). Unfortunately, body image disturbance is often observed after breast cancer treatments, such as mastectomy, which inevitably change the patients' physical appearance (Breast Cancer Care, 2018). Alopecia caused by chemotherapy also contributes to the disturbed body image (Choi et al., 2014). In a society in which a person's appearance somehow defines their worth, such a change that does not fit into the “standard of beauty” almost always results in a disturbed self‐image and reduced self‐worth (Hawkins, 1999). A disturbed body image in turn leads to other psychological problems such as emotional distress, low self‐esteem, anxiety and depression. These problems often have detrimental effects on the individual's daily life by promoting social withdrawal and isolation, drug abuse and self‐harm behaviour (Perspectives Counselling Centers, 2016).

Quality of life is defined as a person's perception of life in terms of their goals, standards, concerns and expectations, and it is affected by multiple aspects, such as physical health and psychosocial well‐being, as well as values and beliefs (WHO, 2022). Given that a disturbed body image has a major influence on a person's psychosocial functioning, it also affects a person's quality of life. Breast cancer survivors encounter challenges in coping with their bodily changes, such as loss of hair or part/all of their breasts. Even if they undergo reconstructive surgery, they may still have to deal with the loss of sensation in the affected breast and the altered appearance (American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Content Team, 2017). Such bodily changes may lead to relationship issues due to the survivors losing sexual interest or confidence. The survivors may thus experience concerns regarding their sexuality, which further deteriorate their quality of life (American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Content Team, 2017). As the disturbances in body image are usually permanent, breast cancer survivors may have to deal with the negative outcomes for the rest of their lives (American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Content Team, 2017). Furthermore, the psychosocial stress may affect the survivors' physical health, leading to symptoms such as insomnia and headache (Revere Health, 2018), which hamper their daily routines and consequently affect their quality of life. These reports indicate that body image is closely linked to quality of life in different aspects and that a negative body image leads to a poor quality of life (Nayir et al., 2016). Thus, breast cancer survivors living with a negative body image might be experiencing a poor quality of life, causing them to be dissatisfied and generally “unhappy” in their life.

Given the detrimental effects of breast cancer and its treatment on the body image of patients as well as the resultant impact on their quality of life, psychosocial or exercise interventions are expected to help the survivors to improve their body image and related outcomes. Exercise interventions involve a planned and repetitive set of physical activity with the aim to improve or maintain physical fitness (Caspersen et al., 1985), while psychosocial interventions focus on improving psychological, behavioural and social aspects of health and well‐being rather than biological aspects (WHO, 2015). Some researchers have provided evidence that exercise and psychosocial interventions are effective at improving body image, but such evidence is inconsistent. As a result, questions were raised as to what impact does exercise and psychosocial interventions have on the body image of breast cancer survivors? Also, what are the most effective exercise and psychosocial interventions for raising their body image?

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Design

A critical review was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (Moher et al., 2009).

3.2. Method

A comprehensive search was carried out in four databases – MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and British Nursing Index – to identify relevant articles. The following keywords and combinations were used: “breast cancer,” “body image,” “exercise” and “psychosocial intervention.” Studies that have evaluated the effects of exercise or psychosocial interventions on the body image of breast cancer survivors as the outcome were included in this review. Both interventional studies and review studies were considered for inclusion. However, only those studies that were available in English, were published in the past 10 years (2011–2021) and had their full text available were considered eligible for inclusion. No criterion was applied regarding participants' age in the studies so as to include as much relevant and important information as possible to produce a comprehensive and critical review.

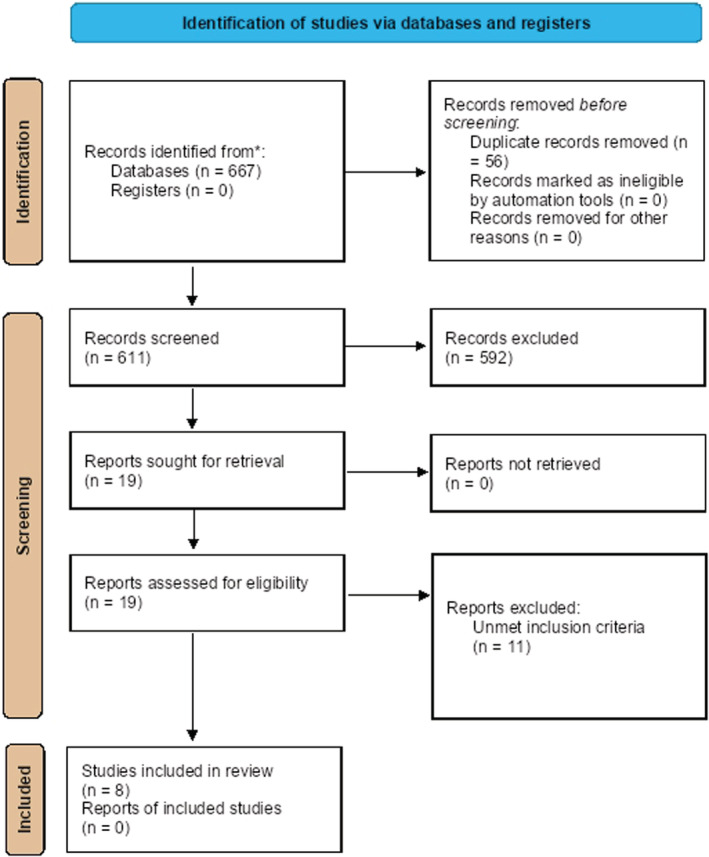

A total of 667 potentially relevant articles were identified through database searching. After examining their titles and abstracts, 611 articles that were irrelevant or duplicated were removed. Full texts of the remaining 19 articles were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Eleven articles were excluded due to unmet inclusion criteria, and the remaining eight studies were included in this review. The study retrieval and selection process are presented in a PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of studies retrieval and selection

3.3. Analysis

3.3.1. Quality appraisal

The quality appraisal of the eight included studies in this review was critically appraised by one reviewer using the critical appraisal checklists of the Center for Evidence‐based Management (2020) to determine the strengths and weaknesses and thus the quality and reliability of the studies, and then checked by the second reviewer. All of the included studies clearly addressed the focus question. In the RCTs (Paulo et al., 2019; Sherman et al., 2018), participant recruitment and randomisation were robust, and the experimental and control groups contained comparable populations, with their inclusion and exclusion criteria being clearly described. All RCTs used objective and validated measurement tools to collect the data and achieved a practical effect size. However, one RCT did not provide a confidence interval nor did it account for potential confounders (Paulo et al., 2019)

The sole case study included in this review (Stan et al., 2012) had an appropriate study design and provided a clear description of the context. However, the data collection process was not clearly presented, and it was unclear whether all of the collected data were inspected by all persons in the research team. The data analysis process was robust, and the results well supported the conclusions drawn.

Of the five review studies included in this review (Duijts et al., 2011; Fong et al., 2012; Hall‐Alston, 2015; Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018; Matthews et al., 2017), all had a robust search process and most of them prevented publication bias as much as possible. All reviews clearly stated the inclusion and exclusion criteria and included studies with consistent results. However, three of the five review studies did not assess the methodological quality of the included studies using pre‐determined quality criteria (Duijts et al., 2011; Hall‐Alston, 2015; Matthews et al., 2017), and only one review study successfully conducted a meta‐analysis and clearly listed the key features of the included studies (Hall‐Alston, 2015). Furthermore, only one study provided the effect sizes and confidence intervals (Duijts et al., 2011). Thus, the effect sizes of the other studies were either not clear or not practical (Fong et al., 2012; Hall‐Alston, 2015; Matthews et al., 2017). Overall, the included review studies had an average methodological quality, and the evidence they provided was of acceptable strength, except for one study that was found to have a poor methodological quality (Hall‐Alston, 2015). Tables 1, 2, and 3 summarize the methodological quality of the included interventional, case and review studies.

TABLE 1.

Critical appraisal of controlled studies

| Appraisal questions | Paulo et al., 2019 | Sherman et al., 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Did the study address a clearly focused question/issue? | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Is the research method (study design) appropriate for answering the research question? | Yes | Yes |

| 3. Were there enough subjects (employees, teams, divisions, organizations) in the study to establish that the findings did not occur by chance? | Yes | Yes |

| 4. Were subjects randomly allocated to the experimental and control group? If not, could this have introduced bias? | Yes | Yes |

| 5. Are objective inclusion/exclusion criteria used? | Yes | Yes |

| 6. Were both groups comparable at the start of the study? | Yes | Yes |

| 7. Were objective and unbiased outcome criteria used? | Yes | Yes |

| 8. Are objective and validated measurement methods used to measure the outcome? If not, was the outcome assessed by someone who was unaware of the group assignment (i.e. was the assessor blinded)? | Yes | Yes |

| 9. Is the size effect practically relevant? | Yes | Yes |

| 10. How precise is the estimate of the effect? Were confidence intervals given? | No CI provided | CI = 95% |

| 11. Could there be confounding factors that have not been accounted for? | No | No |

| 12. Can the results be applied to your organization? | Yes | Yes |

TABLE 2.

Critical appraisal of a case study

| Appraisal questions | Stan et al., 2012 |

|---|---|

| 1. Did the study address a clearly focused question/issue? | Yes |

| 2. Is the research method (study design) appropriate for answering the research question? | Yes |

| 3. Was the context clearly described? | Yes |

| 4. How was the fieldwork undertaken? Was it described in detail? Are the methods for collecting data clearly described? | No |

| 5. Could the evidence (fieldwork notes, interview transcripts, recordings, documentary analysis, etc.) be inspected independently by others? | Not Clear |

| 6. Are the procedures for data analysis reliable and theoretically justified? Are quality control measures used? | Yes |

| 7. Was the analysis repeated by more than one researcher to ensure reliability? | Yes |

| 8. Are the results credible, and if so, are they relevant for practice? | Yes |

| 9. Are the conclusions drawn justified by the results? | Yes |

| 10. Are the findings of the study transferable to other settings? | Yes |

TABLE 3.

Critical appraisal of reviewed articles

| Appraisal questions | Duijts et al., 2011 | Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018 | Hall‐Alston, 2015 | Fong et al., 2012 | Matthews et al., 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Did the study address a clearly focused question? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Was a comprehensive literature search conducted using relevant research databases (i.e. ABI/INFORM, Business Source Premier, PsycINFO and Web of Science). | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3. Is the search systematic and reproducible (e.g. were searched information sources listed, were search terms provided)? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4. Has publication bias been prevented as far as possible (e.g. were attempts made at collecting unpublished data)? | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| 5. Are the inclusion and exclusion criteria clearly defined (e.g. population, outcomes of interest, study design) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6. Was the methodological quality of each study assessed using predetermined quality criteria? | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| 7. Are the key features (population, sample size, study design, outcome measures, effect sizes, limitations) of the included studies described? | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 8. Has the meta‐analysis been conducted correctly? | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 9. Were the results similar from study to study? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10. Is the effect size practical relevant? | Yes | Yes | No | Not Clear | No |

| 11. How precise is the estimate of the effect? Were confidence intervals given? | ES and CI were provided | CI not provided | No ES and CI were provided | CI were provided | CI not provided |

| 12. Can the results be applied to your organization? | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

3.3.2. Data abstraction

Data were extracted from the chosen studies and reported using two data extraction tables, one for interventional studies and one for review studies. The extracted data table for interventional studies included the following components: (1) authors and year; (2) country; (3) study design; (4) sample size; (5) interventions; (6) outcome measures and (7) major findings. The extracted data table for review studies included the following components: (1) authors and year; (2) study design; (3) studies included; (4) major findings and (5) recommended intervention design.

One reviewer conducted the data extraction process, which was checked by the second reviewer for accuracy.

3.3.3. Data synthesis

A convergent segregated approach was used where qualitative and quantitative data was first independently synthesized and followed by an integration of both findings (Stern et al., 2020). Separate narrative summaries for exercise intervention and psychosocial intervention were made. One reviewer conducted the initial analysis and synthesis of the data, which was then checked by the second reviewer. Consensus were made through discussion between the two reviewers.

3.4. Ethics

Ethical approval for this study was not required.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Description of the included studies

Eight studies were included in the review. The study retrieval and selection process are presented in a PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1. Six of these studies measured the effects of exercise interventions on breast cancer survivors, of which one was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Paulo et al., 2019), one was an open‐label study (Stan et al., 2012), and four were review articles on the effects of exercise on the body image of breast cancer survivors (Duijts et al., 2011; Fong et al., 2012; Hall‐Alston, 2015; Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018). One each of the two interventional studies was conducted in Brazil (Paulo et al., 2019) and the United States (Stan et al., 2012).

Three of the included studies evaluated the effects of psychosocial interventions on breast cancer survivors. Of these, one adopted an RCT design and was conducted in Australia (Sherman et al., 2018), while the remaining two were review articles (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018; Matthews et al., 2017).

The interventional studies adopted different instruments to measure the outcome variables. Paulo et al. (2019) used the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Breast Cancer Module (EORTC QLQ‐BR23), Stan et al. (2012) used the Multidimensional Body‐Self Relations Questionnaire (MBRSQ) and Sherman et al. (2018) used the Body Image Scale to measure the changes in body image among breast cancer survivors. Tables 4 and 5 summarize the details of the included studies.

TABLE 4.

Description of the included interventional studies on exercise and psychological interventions for breast cancer survivors

| Study | Country | Study design | Sample size | Interventions | Outcome measures | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paulo et al., 2019 | Brazil | RCT | 36 |

Intervention group:

Control group:

|

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Breast Cancer Module (EORTC QLQ‐BR23) |

|

| Stan et al., 2012 | USA | Open‐label one‐arm study | 15 |

Intervention group:

The intervention included both class‐ and home‐based Pilates sessions. |

Multidimensional Body‐Self Relations Questionnaire (MBRSQ) |

|

| Sherman et al., 2018 | Australia | RCT | 304 |

Intervention group:

Control group:

|

The 10‐Item Body Image Scale |

|

TABLE 5.

Description of the included interventional studies on exercise and psychological interventions for breast cancer survivors

| Study | Study design | Studies included | Major findings | Recommended intervention design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duijts et al., 2011 | Systematic review and meta‐analysis | 56 RCTs |

|

|

| Fong et al., 2012 | Systematic review and meta‐analysis | 34 RCTs |

|

|

| Hall‐Alston, 2015 | Literature review | 34 |

|

|

| Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018 | Systematic review | 21 |

|

|

| Matthews et al., 2017 | Systematic review and meta‐analysis | 32 |

|

|

4.2. Effects of exercise interventions on the body image of breast cancer survivors

All of the six studies on exercise interventions reported that exercise effected positive changes in the body image of breast cancer survivors. In the RCT by Paulo et al. (2019), the participants were randomly allocated to an intervention group that received exercise sessions three times per week for 9 months or to a control group that received stretching and relaxation exercises two times per week for 9 months. The combined training involving both resistance and aerobic exercises that was given to the intervention group led to statistically significant improvements in body image at 3‐ and 9‐month post‐intervention compared with the control group (p < .001). Similarly, in the study by Stan et al. (2012), Pilates improved the participants' body image, particularly in the subscales of health evaluation and body area satisfaction, after a 12‐week open‐label programme that involved two sessions per week for the first 4 weeks, three sessions per week for the next 4 weeks, and four sessions per week for the last 4 weeks, with each session lasting 45 min.

The review by Duijts et al. (2011) also identified statistically significant results for the effects of physical exercise interventions, such as aerobic exercises and motor activities, on body image (p = .007). Specifically, the weight‐loss effect of exercise was found to be a major factor contributing to the improved body image, and nurse practitioners were reported to be the key players in building a conducive environment to encourage survivors' participation in exercise (Fong et al., 2012; Hall‐Alston, 2015).

4.3. Effects of psychosocial interventions on the body image of breast cancer survivors

All of the three studies on psychosocial interventions reported overall positive effects on the body image of breast cancer survivors (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018; Matthews et al., 2017; Sherman et al., 2018). In the RCT by Sherman et al. (2018), the participants were randomly allocated to an intervention group involving an online writing activity with five self‐compassionate prompts as guidance or to a control group involving the writing activity without the self‐compassionate prompts. Participants in the intervention group reported having significant reduction in body image‐related distress (p = .035), improvement in body appreciation (p = .004) and increased self‐compassion (p < .001) relative to the control group (Sherman et al., 2018).

Significant treatment effects on body image were also observed after cognitive behavioural therapy and support group intervention (Matthews et al., 2017). Psychotherapy and psychoeducation were found to significantly improve body image at post‐test (ds = 0.15–0.43), but the effects were not sustained at follow‐ups (from 3 weeks to 9 months) (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018).

5. DISCUSSION

A disturbed body image is a common problem among breast cancer survivors due to bodily changes such as breast removal and alopecia as a result of cancer treatments (Breast Cancer Care, 2018; Choi et al., 2014). Researchers have attempted to develop interventions and solutions to help these survivors improve their body image and, consequently, their quality of life.

This critical review identified that exercise interventions have positive effects on the body image of breast cancer survivors by reducing their body weight and improving both their physical and mental well‐being.

5.1. Effective design of exercise and psychosocial interventions

The effective design of exercise and psychosocial interventions that maximize the benefits to the body image of breast cancer survivors is being identified after reviewing the eight included articles. The content, components, format, duration and provider of the interventions delivered in the included studies are identified and compared below.

5.1.1. Content and components

Various types of exercises were included in the interventions adopted in the studies. Six studies suggested aerobic exercise with resistance training to improve body image (Duijts et al., 2011; Fong et al., 2012; Hall‐Alston, 2015; Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018; Paulo et al., 2019; Stan et al., 2012). Two of these studies also suggested Pilates (Hall‐Alston, 2015; Stan et al., 2012), while one also suggested relaxation and physiotherapeutic exercises (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018).

Among the reviewed psychosocial interventions, a web‐based self‐compassion‐focused writing activity using the model of therapeutic expressive writing (EW) designed for oncology patients was found to be the most effective in improving breast cancer survivors' body image, with the effects found to be sustained even at 1 week, 1 month and 3 months post‐intervention (Sherman et al., 2018). Another study reported the efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy and support groups in improving body image (Matthews et al., 2017). The review by Lewis‐Smith et al. (2018) provides several recommendations for future studies. For example, evaluative studies on psychosocial interventions to improve breast cancer survivors' body image are recommended to use empirically supported theories, approaches that only address body image, psychosocial interventions with a narrow disease‐focused approach, follow‐up evaluations and robust methodology. Components such as logical treatment, adaptive techniques to cope with bodily changes, relaxation training and problem‐solving skills with homework done in‐between sessions are also suggested (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018). Another effective component would be meditation and yoga classes, accompanied with body scans, that teach mindfulness of one's own reactions, emotions and bodily sensations (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018). Lastly, educational lectures would be another effective component to provide breast cancer survivors with support or suggestions on how to manage the disease consequences (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018).

5.1.2. Format

All formats of exercise interventions, including home‐based, class‐based and instructor‐led formats, were found to be effective at improving the body image of participants. Among these, the highest patient adherence was reported for home‐based exercise (Hall‐Alston, 2015). As for Pilates, both home‐based and instructor‐led approaches were effective (Stan et al., 2012).

Among the psychosocial interventions, psychological writing exercise was found to be an effective and appropriate online‐based approach, wherein the participants completed the writing alone while receiving guidance from both the EW and five self‐compassionate prompts (Sherman et al., 2018). Psychosocial interventions delivered individually in face‐to‐face format, as well as those encompassing multiple sessions, were reported to be effective at improving the body image of breast cancer survivors (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018).

5.1.3. Duration

Among exercise interventions, a 40‐minute aerobic and resistance exercise delivered three times a week for 9 months was found to be effective in bringing about positive changes to the survivor's body image (Paulo et al., 2019), and so was a 12‐week Pilates programme with 45‐minute Pilates sessions delivered twice per week for the first 4 weeks, three times per week for the next 4 weeks and four times per week for the last 4 weeks, for a total of 36 sessions (Stan et al., 2012).

Among psychosocial interventions, a single 30‐minute session of web‐based self‐compassion‐focused writing activity was found to be effective, but the optimal number of writing sessions that could bring maximum effects was not determined in the study (Sherman et al., 2018). Another six‐ to eight‐session psychosocial intervention programme including psychotherapy and psychoeducation was also found to be effective (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018). As for educational interventions, 1 week is recommended as an appropriate duration to effect noticeable changes in the body image of participants (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018).

5.1.4. Provider

To deliver exercise interventions, a multidisciplinary team should be established to maximize the effects of the interventions, with a nurse practitioner serving as the liaison person to help build rapport between the healthcare professionals and the survivors, their family and their caregivers (Hall‐Alston, 2015). For Pilates‐based interventions, the exercises should be delivered by a Pilates Method Alliance‐certified instructor (Stan et al., 2012).

No provider or in‐person support is required for the web‐based self‐compassion‐focused writing activity, as the breast cancer survivors who participated in the trial demonstrated a high‐retention rate and high compliance with the private and independent nature of the programme, where minimal face‐to‐face contact is required. Such an intervention is especially useful for breast cancer survivors who prefer to address their body image issues privately to minimize embarrassment or psychological discomfort (Sherman et al., 2018). Other psychosocial interventions should be delivered by psychiatrists, clinical psychologists or personnel with a nursing background for maximum efficacy (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018).

In sum, both home‐based and class‐based instructor‐led formats for exercise intervention are effective, with the former showing significantly more efficacy than the latter (Hall‐Alston, 2015). Various types of exercises and their modes of delivery have been proposed. Among the types, aerobic and resistance exercises were adopted in almost all of the included studies (Duijts et al., 2011; Fong et al., 2012; Hall‐Alston, 2015; Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018; Paulo et al., 2019; Stan et al., 2012). A 40‐minute aerobic and resistance exercise session delivered three times per week showed the highest effectiveness in improving the participants' body image. Besides aerobic and resistance exercises, Pilates was suggested as a useful type of exercise for this purpose. A 12‐week Pilates programme comprising 36 class‐based sessions of 45‐minute Pilates exercise was recommended. However, the modes of delivery of exercise interventions were inconsistent across the included studies. Overall, all of the four review studies agreed on the use of aerobic or resistance training for improving breast cancer survivors' body image (Duijts et al., 2011; Fong et al., 2012; Hall‐Alston, 2015; Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018). The two RCTs (Paulo et al., 2019; Stan et al., 2012) also demonstrated the importance of aerobic and resistance training, in addition to the efficacy of Pilates that includes both aerobic and resistance training components (Stan et al., 2012). The findings of our critical review are consistent with the findings of two previous review studies and provide additional insights.

Among the reported psychosocial interventions, a web‐based self‐compassion‐focused writing activity was the most effective at improving the body image of breast cancer survivors. Self‐compassion refers to kindness towards and understanding of oneself when going through suffering or failure or feeling inadequate (Neff, 2021). It is associated with increased quality of life, decreased psychological distress and enhanced coping with negative experiences (Sherman et al., 2018). Self‐compassion‐focused writing aims to identify the elements that cause oneself to feel ashamed or insecure and eventually guide the person to understand and accept what they dislike about themselves by reminding them to be self‐compassionate (Greater Good in Action UC Berkeley, 2021). The self‐compassion‐focused writing activity helped breast cancer survivors to develop appreciation for their body and thereby reduce their body image‐related distress (Sherman et al., 2018).

The evidence on the efficacy of other psychosocial interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapies, adaptive techniques and support groups was limited and inconsistent. Moreover, the efficacy of psychosocial interventions in improving the body image of breast cancer survivors was not consistent between the related RCTs and two review studies. This difference may be explained by different environments in which interventions were delivered across these studies. Specifically, the RCTs adopted a private environment and delivered the intervention in an online, one‐to‐one format, whereas the two reviews included studies in which interventions were delivered in the face‐to‐face format. Some participants of the self‐compassion‐focused writing activity expressed that they preferred their issues to be addressed privately so as to avoid embarrassment and psychological discomfort, which can otherwise occur when discussing their body image insecurity face‐to‐face or in a group format (Sherman et al., 2018); this indicates that psychosocial interventions delivered in a non‐face‐to‐face environment, for example over the Internet/telecommunication devices, may be more effective than those delivered in a face‐to‐face or group format. Body image affects how a person perceives themselves, and a disturbed body image often negatively affects one's self‐worth. Therefore, individuals with a poor body image commonly exhibit low self‐confidence in public. Thus, providing a private environment that allows them to practice psychosocial interventions safely without fearing judgements or criticisms from others is crucial, as indicated by the results of an RCT (Sherman et al., 2018).

The two review articles concluded that psychosocial interventions have a small effect on body image (Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018; Matthews et al., 2017). In contrast, our critical review found that self‐compassion‐focused writing is effective in improving body image, with sustained effects observed at follow‐up (Sherman et al., 2018). This discrepancy between the findings of our critical review and the two previous review studies suggests that psychosocial interventions have varying efficacy in improving the body image of breast cancer survivors, based on their types and modes of delivery.

Although none of the studies on exercise interventions included in this review adopted a private environment and few involved experts for intervention delivery, it is possible that a private environment and intervention delivery by experts would further increase the effects of the exercise interventions on the body image of breast cancer survivors (Duijts et al., 2011; Fong et al., 2012; Hall‐Alston, 2015; Lewis‐Smith et al., 2018; Paulo et al., 2019; Stan et al., 2012). This is supported by the fact that these two factors significantly enhanced the effects of psychosocial interventions (Sherman et al., 2018), and home‐based instructor‐led exercise programmes were significantly more effective than class‐based instructor‐led programmes (Hall‐Alston, 2015). Thus, our findings show that breast cancer survivors prefer and respond better in a private environment involving few healthcare experts for both exercise and psychosocial interventions.

To conclude, this critical review highlights the need for standardizing exercise interventions to include aerobic and resistance training and Pilates to maximize the positive effects on the body image of breast cancer survivors. It also emphasizes the efficacy and importance of providing a private environment, for both exercise and psychosocial interventions, to maximize the intervention effects on survivors' body image.

5.2. Implication for future research and nursing practice

Aerobic exercise, resistance exercise and Pilates are effective exercise interventions for improving breast cancer survivors' body image. It is recommended that physical exercise be incorporated into a standardized routine practice for breast cancer survivors, but further investigation is required to suggest the best mode of delivery for exercise interventions. Nurses have also been found to play an important role in facilitating the intervention effects on body image (Hall‐Alston, 2015). Thus, nurses should be included in physical exercise programmes to establish a conducive environment for survivor participation and to help build rapport between the survivors and the multidisciplinary team. Further research is warranted to elucidate the factors influencing the motivation and compliance of breast cancer survivors to exercise interventions; such research can inform ways to reduce the dropout and failure rates of the interventions. Furthermore, future studies should investigate the feasibility and effectiveness of delivering exercise programmes in a private environment involving none or few healthcare experts.

As for psychosocial interventions, research is required to determine the number of sessions required to maximize the effects of the web‐based self‐compassion‐focused writing activity on survivors' body image. Private environments with no face‐to‐face interactions should be considered in the development of future psychosocial interventions aiming at improving body image.

Most of the studies included in our critical review were review studies, besides two interventional studies on exercise interventions and only one interventional study on a psychosocial intervention. Therefore, more RCTs should be carried out to further investigate the efficacy of and best practices for delivering these interventions for breast cancer survivors.

6. LIMITATIONS

Limited evidence is currently available on the success of psychosocial interventions other than self‐compassion‐focused writing in improving survivors' body image. Compared with the larger number of in‐depth studies that have provided consistent evidence supporting the usefulness of exercise interventions, few studies have evaluated the efficacy of psychosocial interventions and the evidence of those few studies is also inconsistent. Furthermore, both review studies on psychosocial intervention included in this critical review only investigated body image as a minor component in their literature. Thus, there is a lack of in‐depth investigations focusing on the varying efficacy of psychosocial interventions in improving body image. In fact, only one study has reported the efficacy of the self‐compassion‐focused writing activity in improving the body image of breast cancer survivors (Sherman et al., 2018). Thus, further in‐depth investigations of the effects of the writing activity intervention and other psychosocial interventions on breast cancer survivors' body image are warranted.

7. CONCLUSION

This review demonstrates the significant effectiveness of physical exercise programmes (Duijts et al., 2011; Fong et al., 2012; Hall‐Alston, 2015; Paulo et al., 2019; Stan et al., 2012) and varying significance of psychosocial interventions in improving the body image of breast cancer survivors (Sherman et al., 2018).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria [recommended by the ICMJE (http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/)]:

substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data.

drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Chan, N. C. , & Chow, K. M. (2023). A critical review: Effects of exercise and psychosocial interventions on the body image of breast cancer survivors. Nursing Open, 10, 1954–1965. 10.1002/nop2.1507

REFERENCES

- American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Content Team . (2017). What is breast cancer? Retrieved from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast cancer/about/what‐is‐ breast‐cancer.html

- American Cancer Society Medical and Editorial Team . (2017). Body image and Sexuality after breast cancer . Retrieved from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/ breast‐cancer/living‐as‐a‐breast‐cancer‐survivor/body‐image‐and‐sexuality‐after‐ breast‐cancer.html

- Breast Cancer Care . (2018). Body image and breast cancer . Retrieved from: https://www.breastcancercare.org.uk/get‐involved/campaign‐us/body‐image‐ breast‐cancer

- Cancer.Net Editorial Board . (2018). Breast cancer: Statistics . Retrieved from: https://www.cancer.net/cancer‐types/breast‐cancer/statistics/2015

- Caspersen, C. J. , Powell, K. E. , & Christenson, G. M. (1985). Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health‐related research. Public Health Reports, 100(2), 126–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Evidence‐based Management . (2020). Critical Appraisal . Retrieved from: https://cebma.org/resources‐and‐tools/what‐is‐critical‐appraisal/

- Centre for Health Protection . (2018). Breast cancer . Retrieved from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/healthtopics/content/25/53.html

- Choi, E. K. , Kim, I. R. , Chang, O. , Kang, D. , Nam, S. J. , Lee, J. E. , Lee, S. K. , Im, Y. H. , Park, Y. H. , Yang, J. H. , & Cho, J. (2014). Impact of chemotherapy‐induced alopecia distress on body image, psychosocial well‐being, and depression in breast cancer patients. Psycho‐Oncology, 23(10), 1103–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duijts, S. F. , Faber, M. M. , Oldenburg, H. S. , Van Beurden, M. , & Aaronson, N. K. (2011). Effectiveness of behavioural techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health‐related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors—A meta. Psycho‐Oncology, 20(2), 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong, D. Y. , Ho, J. W. , Hui, B. P. , Lee, A. M. , Macfarlane, D. J. , Leung, S. S. , Cerin, E. , Chan, W. Y. , Leung, I. P. , Lam, S. H. , Cheng, K. K. , & Taylor, A. J. (2012). Physical activity for cancer survivors: Meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ, 344, e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greater Good in Action UC Berkeley . (2021). Self‐Compassionate Letter. Retrieved from: https://self‐compassion.org/the‐three‐elements‐of‐self‐compassion‐2/#definition

- Hall‐Alston, J. M. (2015). Exercise and the breast cancer survivor: The role of the practitioner. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 19(5), E98–E102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, N. (1999). The impact of the ideal thin body image on women. Utah State University. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis‐Smith, H. , Diedrichs, P. C. , Rumsey, N. , & Harcourt, D. (2018). Efficacy of psychosocial physical activity‐based interventions to improve body image among women treated for breast cancer: A review. Psycho‐Oncology, 27(12), 2687–2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, H. , Grunfeld, E. A. , & Turner, A. (2017). The efficacy of interventions to improve psychosocial outcomes following surgical treatment for breast cancer: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Psycho‐Oncology, 26(5), 593–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , Altman, D. G. , & Group, T. P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, e1000097. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Eating Disorder Association . (2018). Body image . Retrieved from: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/body‐image‐0

- Nayir, T. , Uskun, E. , Volkan, M. , Yurekli, Devran, H. , Celik, A. , & Okyay, R. A. (2016). Does body image affect quality of life?: A population based study. PLoS One, 11, e0163290. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff, K. (2021). Self‐Compassion. Retrieved from: https://self‐compassion.org/the‐three‐elements‐of‐self‐compassion‐2/#definition

- Paulo, T. R. , Rossi, F. E. , Viezel, J. , Tosello, G. T. , Seidinger, S. C. , Simões, R. R. , De Freitas, R., Jr. , & Freitas, I. F., Jr. (2019). The impact of an exercise program on quality of life in older breast cancer survivors undergoing aromatase inhibitor therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 17(1), 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perspectives Counselling Centers . (2016). Negative body image & you, Part 1. Retrieved from: https://www.perspectivesoftroy.com/2020/10/07/negative‐body‐image‐you‐part‐1/.

- Revere Health . (2018). Recognising and treating depression in teens. Retrieved from: https://reverehealth.com/live‐better/recognizing‐and‐treating‐depression‐in‐teens/.

- Sherman, K. A. , Przezdziecki, A. , Alcorso, J. , Kilby, C. J. , Elder, E. , Boyages, J. , Koelmeyer, L. , & Mackie, H. (2018). Reducing body image–related distress in women with breast cancer using a structured online writing exercise: Results from the my changed body randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 36(19), 1930–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stan, D. L. , Kathleen Sundt, R. N. , Cheville, A. L. , Youdas, J. W. , Krause, D. A. , Boughey, J. C. , & Pruthi, S. (2012). Pilates for breast cancer survivors: Impact on physical parameters and quality of life mastectomy. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16(2), 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, C. , Lizarondo, L. , Carrier, J. , Godfrey, C. , Rieger, K. , Salmond, S. , Apóstolo, J. , Kirkpatrick, P. , & Loveday, H. (2020). Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2108–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . (2021). Breast Cancer . Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/breast‐cancer

- World Health Organisation . (2022). WHOQOL‐Measuring quality of life. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol.

- World Health Organization . (2015). Thinking healthy: A manual for psychosocial management of perinatal depression, WHO generic field‐trial version 1.0, 2015 (No. WHO/MSD/MER/15.1). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]